Abstract

Background: Mental health disorders are the number one cause of maternal mortality and a significant maternal morbidity. This scoping review sought to understand the associations between social context and experiences during pregnancy and birth, biological indicators of stress and weathering, and perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs). Methods: A scoping review was performed using PRISMA-ScR guidance and JBI scoping review methodology. The search was conducted in OVID Medline and Embase. Results: This review identified 74 eligible English-language peer-reviewed original research articles. A majority of studies reported significant associations between social context, negative and stressful experiences in the prenatal period, and a higher incidence of diagnosis and symptoms of PMADs. Included studies reported significant associations between postpartum depression and prenatal stressors (n = 17), socioeconomic disadvantage (n = 14), negative birth experiences (n = 9), obstetric violence (n = 3), and mistreatment by maternity care providers (n = 3). Birth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was positively associated with negative birth experiences (n = 11), obstetric violence (n = 1), mistreatment by the maternity care team (n = 1), socioeconomic disadvantage (n = 2), and prenatal stress (n = 1); and inverse association with supportiveness of the maternity care team (n = 5) and presence of a birth companion or doula (n = 4). Postpartum anxiety was significantly associated with negative birth experiences (n = 2) and prenatal stress (n = 3). Findings related to associations between biomarkers of stress and weathering, perinatal exposures, and PMADs (n = 14) had mixed significance. Conclusions: Postpartum mental health outcomes are linked with the prenatal social context and interactions with the maternity care team during pregnancy and birth. Respectful maternity care has the potential to reduce adverse postpartum mental health outcomes, especially for persons affected by systemic oppression.

1. Introduction

Mental health conditions are the leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States (U.S.) [1]. Each year in the U.S., hundreds of thousands of women and childbearing people and their families are affected by life-altering perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs). PMADs include postpartum depression (PPD), postpartum anxiety, and birth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [2]. The financial impact is also significant; untreated PMADs are estimated to cost USD 14 billion per year [3,4]. Postpartum depression (PPD) alone is estimated to impact 1 in every 5 childbearing women worldwide [5]. PPD creates an environment that is not conducive to parental-role development or optimal child development [6], and severe PPD substantially raises the risk for adverse child developmental outcomes [7]. Despite the high incidence and large impact of PMADs [5], little has been documented about social and systemic factors influencing maternal mental health [8].

Perinatal mental health complications have been linked to various life-experiences in the perinatal period. For example, postpartum psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms from negative birth experiences adversely impact the lives of childbearing women and their infants by disrupting breastfeeding and mother–infant bonding [9]. These disruptions can lead to long-term health complications for both mother and child [10,11,12,13,14]. Similarly, prenatal stress is associated with negative pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth and fetal growth restriction [15,16] and PPD [17]. Perinatal experiences of discrimination are associated with high levels of maternal stress and adverse birth outcomes for both mother and child [6,7,18,19]. In addition to being a risk factor for mistreatment and a significant stressor, socioeconomic disadvantage is also linked with negative birth outcomes and infant mortality [20,21].

Childbearing women and people from communities that have been historically marginalized in the U.S. (i.e., Black and Indigenous persons, and individuals with low socioeconomic status) have inequitably high rates of PPD [22,23]. Women and birthing people who are marginalized due to ethnicity or income are also less likely to seek care for perinatal mental health symptoms [15]. Marginalized individuals report higher rates of care that is discriminatory [24], infringes on their autonomy, and is disrespectful [25,26,27,28,29]. Additionally, individuals from marginalized communities report higher rates of mistreatment by maternity care providers and personnel [25,30,31]. A recent U.S. study found that one in five (20% of 2402 respondents) postpartum mothers reported mistreatment during their maternity care [32]. Rates of mistreatment were higher for Black, Hispanic, and multiracial mothers (30%), and for those with Medicaid (U.S. publicly funded health insurance for individuals with low household income; 30%) [32]. Negative experiences of perinatal care can have long-term consequences on maternal/child health. In contrast, positive care experiences such as respectful, person-centered maternity care has been shown to improve birth outcomes [33], increased patient satisfaction, fewer maternal and newborn complications, and lower incidence of PPD [19].

Researchers have proposed that experiences of stress, discrimination, mistreatment, and adverse social determinants of health create a “weathering” effect on Black women and other marginalized individuals [34]. Weathering is defined as increased wear and tear on the body due to exposure to a lifetime of chronic stress, mistreatment, and discrimination [34,35]. The weathering effect places marginalized women/childbearing people and their infants at an increased intergenerational vulnerability for adverse birth outcomes [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Weathering has been implicated as a key contributor to health disparities [46]. Biomarkers of weathering, such as advanced epigenetic age [47], telomere length [48,49], and allostatic load [35,50,51,52], are indicators of how chronic stress and discrimination get “under the skin” [52] and affect childbearing people at a cellular or biological level [34,46,47,48,49,50,51].

The purpose of this scoping review is to synthesize the current body of research regarding associations between PMADs and (1) perinatal experiences and exposures (specifically, prenatal social context and experiences of care during pregnancy and birth); and (2) biomarkers of weathering. To meet this aim, we searched for studies reporting investigations across three distinct areas of interest: (a) exposures related to social context/experiences during pregnancy and birth, (b) perinatal biomarkers of stress and weathering, and (c) PMADs outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study methods were guided by the JBI (formerly known as the Joanna Briggs Institute) updated methodological guidance for scoping reviews [53] and the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [54]. We registered our scoping review protocol with OSF in October 2023 (link in the Supplementary Materials).

2.1. Search Strategy and Procedure

A literature search was conducted to identify studies that investigated PMADs and their associations with (1) social context and life experiences during pregnancy and birth, and/or (2) physiologic markers of stress and weathering. The search strategy was designed with the guidance of two expert medical librarians (JB and TM). Databases searched included OVID Medline ALL (1946 to 11 October 2023) and OVID EMBASE (1974 to 13 October 2023). The search terms included using both controlled vocabulary and synonymous free text to capture the concepts related to the outcomes. For PMADs, search terms included postpartum depression or postpartum anxiety or posttraumatic stress disorder. Relevant exposures/experiences used the search terms trauma, obstetric violence, discrimination, socioeconomic deprivation, socioeconomic disadvantage, and marginalization. Biomarker search terms were hair cortisol, inflammation, weathering, epigenetic age, and telomere length. Search strategies were adjusted for syntax appropriate for each database. Electronic searches were limited to humans and the English language. Searches were completed on 16 October 2023. Supplementary efforts to identify studies included checking reference lists. The full search strategy for each electronic database is included in the Supplementary Materials. Results were uploaded into EndNote citation management software (Thompson Reuters, version 20) and deduplicated with the final set uploaded into Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Information, www.covidence.org accessed on 4 April 2024).

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

In order to compare among relatively similar settings, we included English-language publications reporting peer-reviewed original research conducted in the 20 countries with the highest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [55]. To ensure a comprehensive scoping review, we made two exceptions to geographic setting that expanded beyond the OECD 20 highest-GDP countries. First, while the specific term “obstetric violence” has been in existence for some time [56,57], it has only more recently been adopted in the research vernacular in the highest income, English-speaking countries, and is still not widely used [58]. Because the specific term was so pertinent to this review, we did not exclude studies based on setting that specifically explored obstetric violence and mistreatment if they were set in other high-development countries where the term has been in use for a longer period of time (i.e., Russia, Croatia, Spain, and Brazil). Second, because biomarkers of stress and weathering in the perinatal period are relatively new topics in the literature, all studies that explored associations between a biologic marker of stress and weathering and an exposure or PMAD were included, regardless of geographic location. Studies were excluded if data were collected prior to 2000 (regardless of publication date), or if no measure for socioeconomic disadvantage was provided beyond stratification by household income. Only original peer-reviewed research was included; all other publication types (i.e., conference proceedings, abstracts, reviews, and commentaries) were excluded.

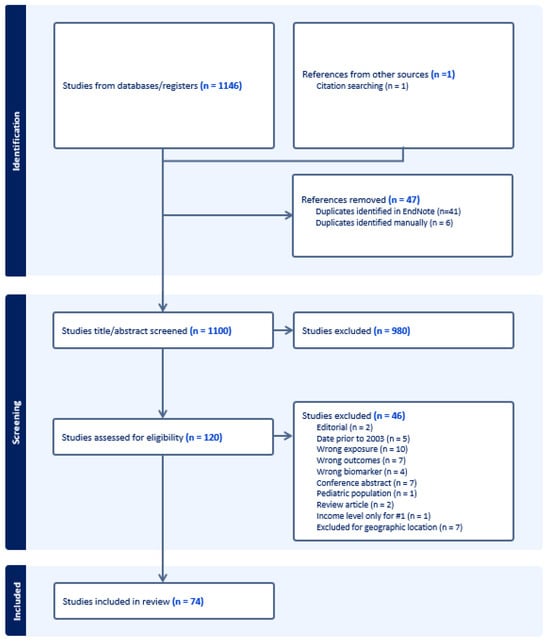

2.3. Study Selection

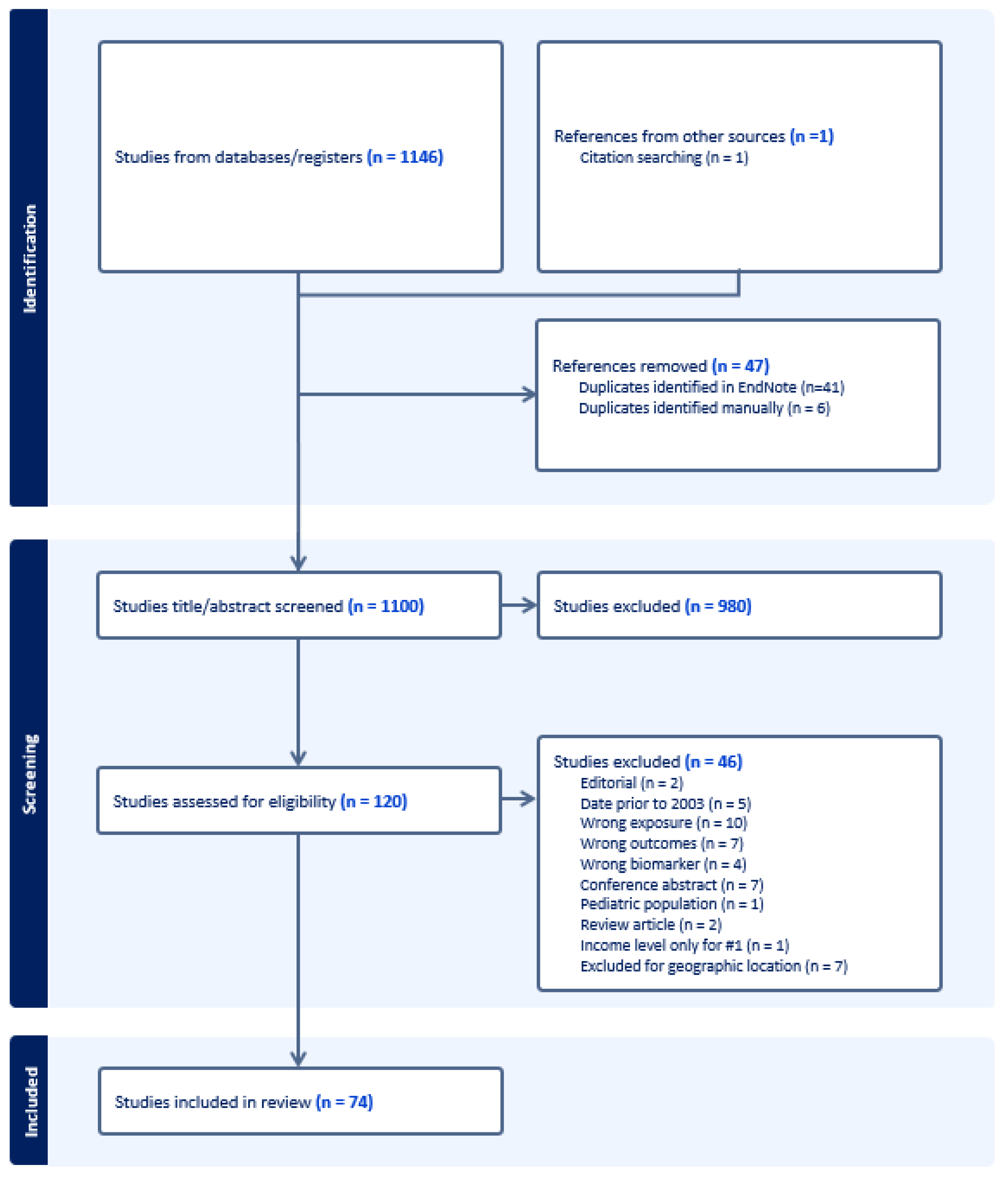

The initial search resulted in 1146 records. After removing duplicates, 1099 remained. Through hand-searching of citations and recent citation alerts, one additional study was identified for screening, resulting in a total of 1100 records. Two independent, interdisciplinary reviewers (BB and RS) conducted the review of records. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers to reach consensus. After title and abstract screening, 120 publications met criteria for full text review. During full text review, 46 publications were excluded, resulting in 74 studies included in this scoping review (Figure 1). Quality appraisal was not completed, as this is not in line with the study methodology [53].

Figure 1.

PRISMA.

2.4. Data Extraction

The lead author (BB) extracted data from each included study using a data extraction matrix created specifically for this review. Data extracted included: first author, year of publication, setting, sample size, study design, exposures and measurement tool for each exposure, biomarkers studied and their tissue source, PMAD outcome and measurement tool, and results. A second reviewer (AS) validated the data extraction.

3. Results

Seventy-four studies published between 2004 and 2023 were included in this scoping review (Table 1 and Table 2). Studies took place across a variety of regions (see Supplementary Table S1) with the majority set in the Americas (n = 34), followed by Europe (n = 28), Asia (n = 7) and Oceania (n = 5). Study designs included prospective longitudinal (n = 38), retrospective (n = 16), cohort (n = 6), and cross-sectional (n = 14) studies. The most commonly evaluated PMAD was postpartum depression (PPD; n = 62), followed by birth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; n = 18). Five studies evaluated postpartum anxiety, and one study evaluated a researcher-defined outcome of maternal mental health status [59]. Several studies (n = 21) reported findings related to multiple exposures and/or PMAD outcomes.

Table 1.

Description of included studies.

Table 2.

Description of included studies with biological measures.

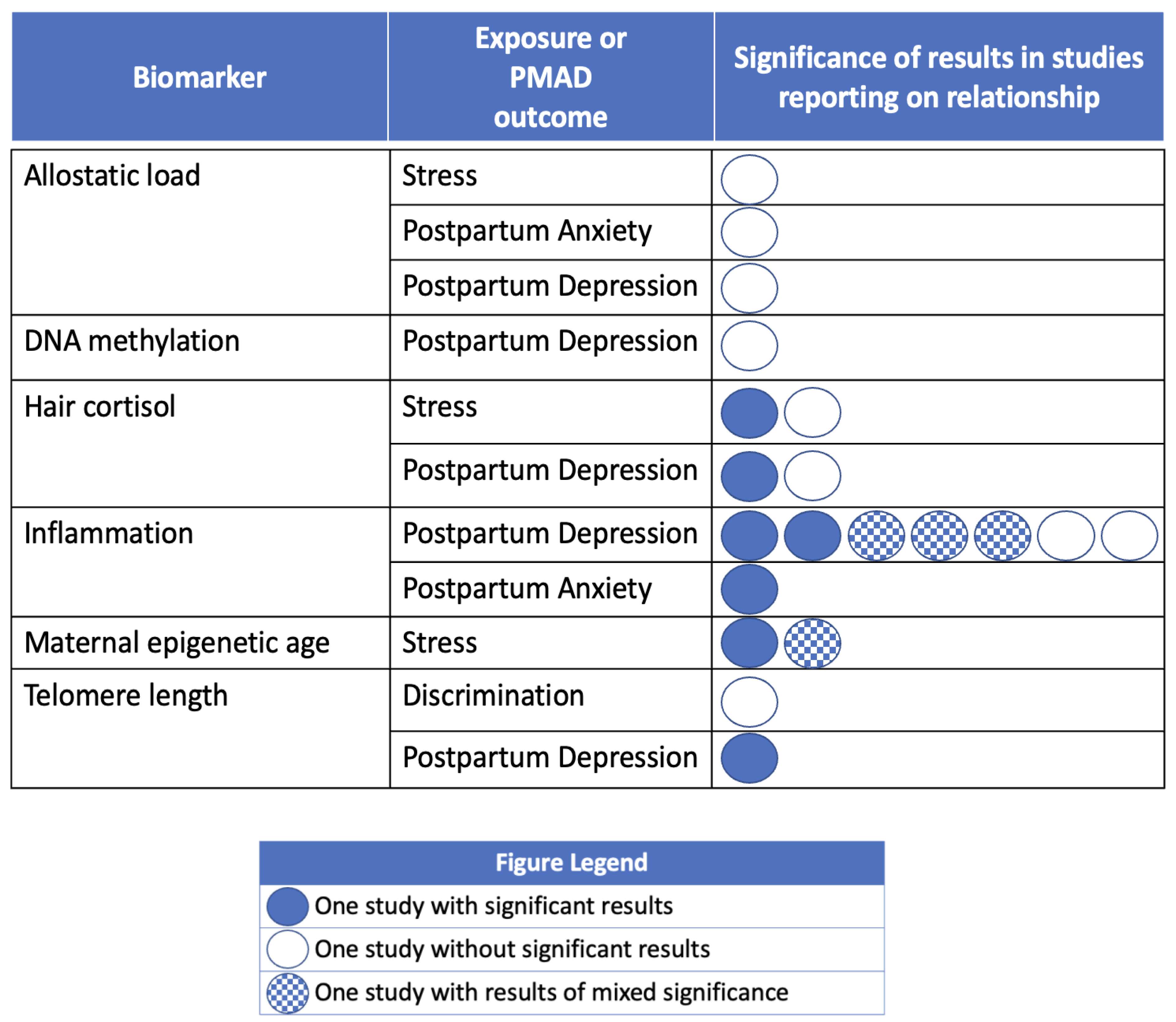

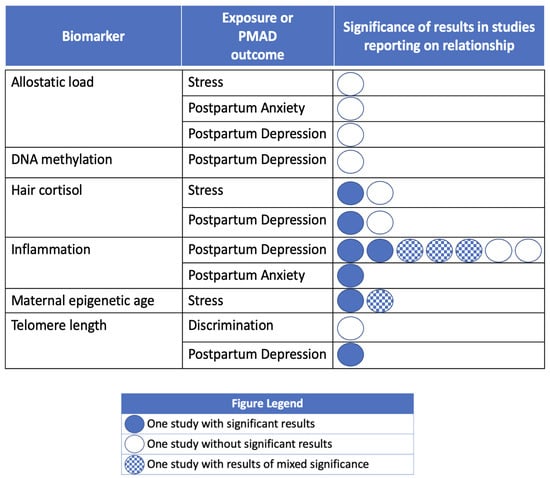

Fourteen studies included perinatal measurement of biological markers of stress or weathering and our exposures or outcomes of interest (Table 2). Most studies evaluating the associations between PMADs and biomarkers of stress and weathering investigated associations with PPD (n = 12). PPD was operationalized using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score in all 12 studies. The most common biomarker explored was inflammatory cytokines (n = 7) [119,120,121,123,128,129,130], followed by hair cortisol (n = 2) [122,131], maternal epigenetic age (n = 2) [125,126], maternal DNA methylation (n = 1) [127], allostatic load (n = 1) [118], and telomere length (n = 1) [124]. Four studies reported associations across all three areas of interest in this scoping review: exposure/experience, biological measure, and PMAD outcome [118,122,124,131].

3.1. Measurement of Exposures/Experiences during Pregnancy and Birth

Most of the measurements for the social context exposures/experiences independent variables were obtained through participant self-reports. Validated measurement tools used to measure the independent exposure/experiences in the included studies are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Instruments to measure exposures in included studies.

3.2. Associations between PMADs and Social Exposures

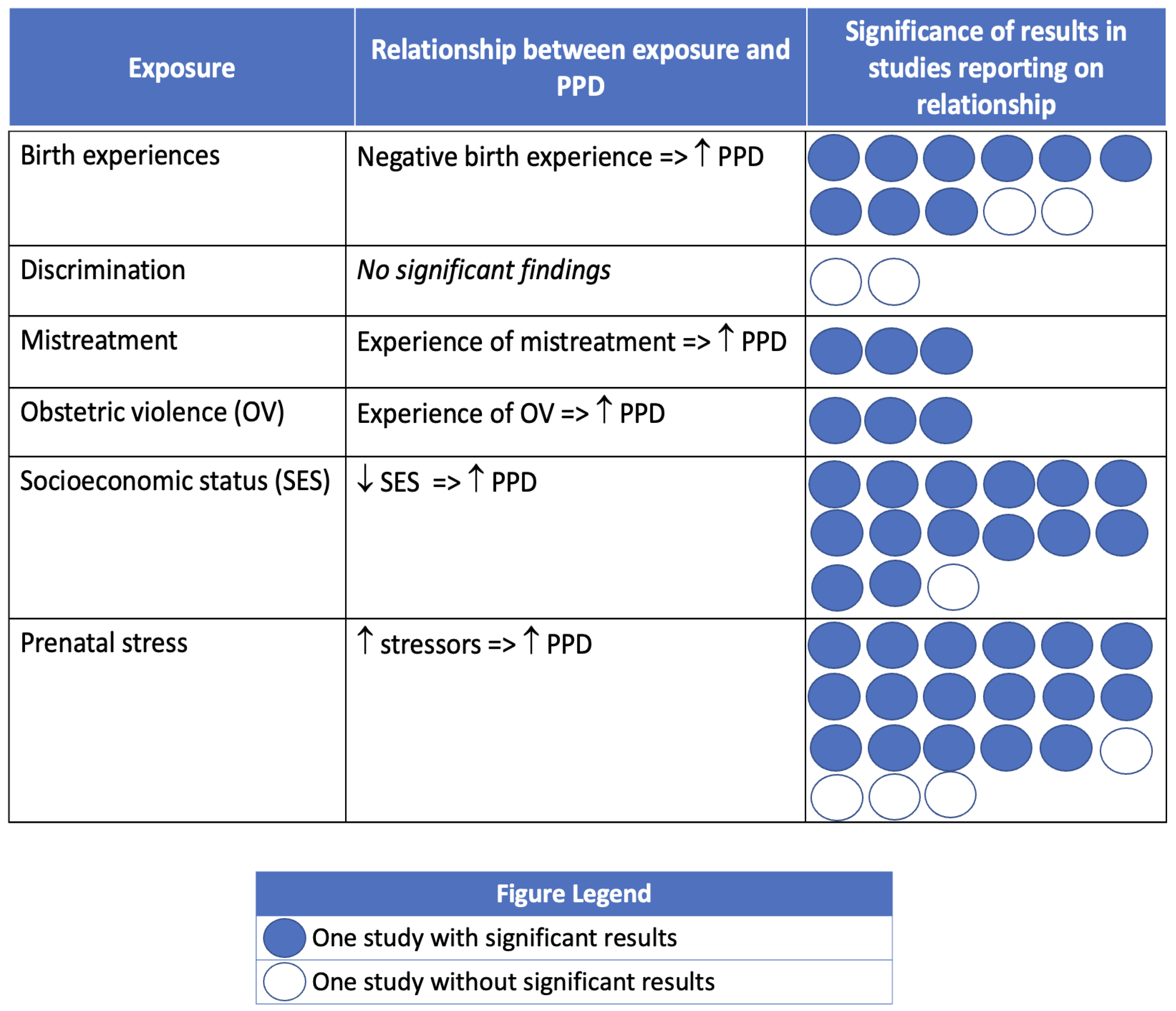

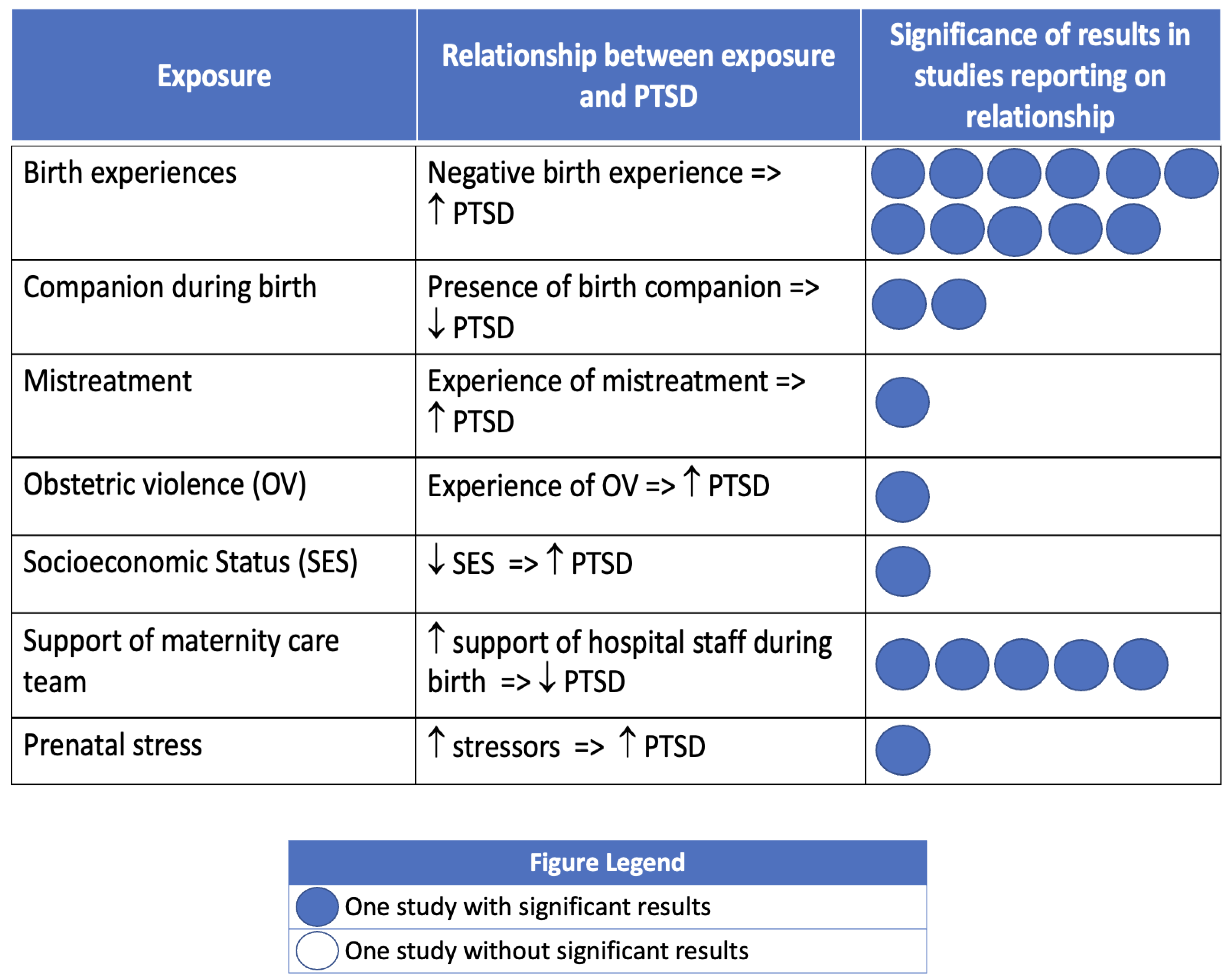

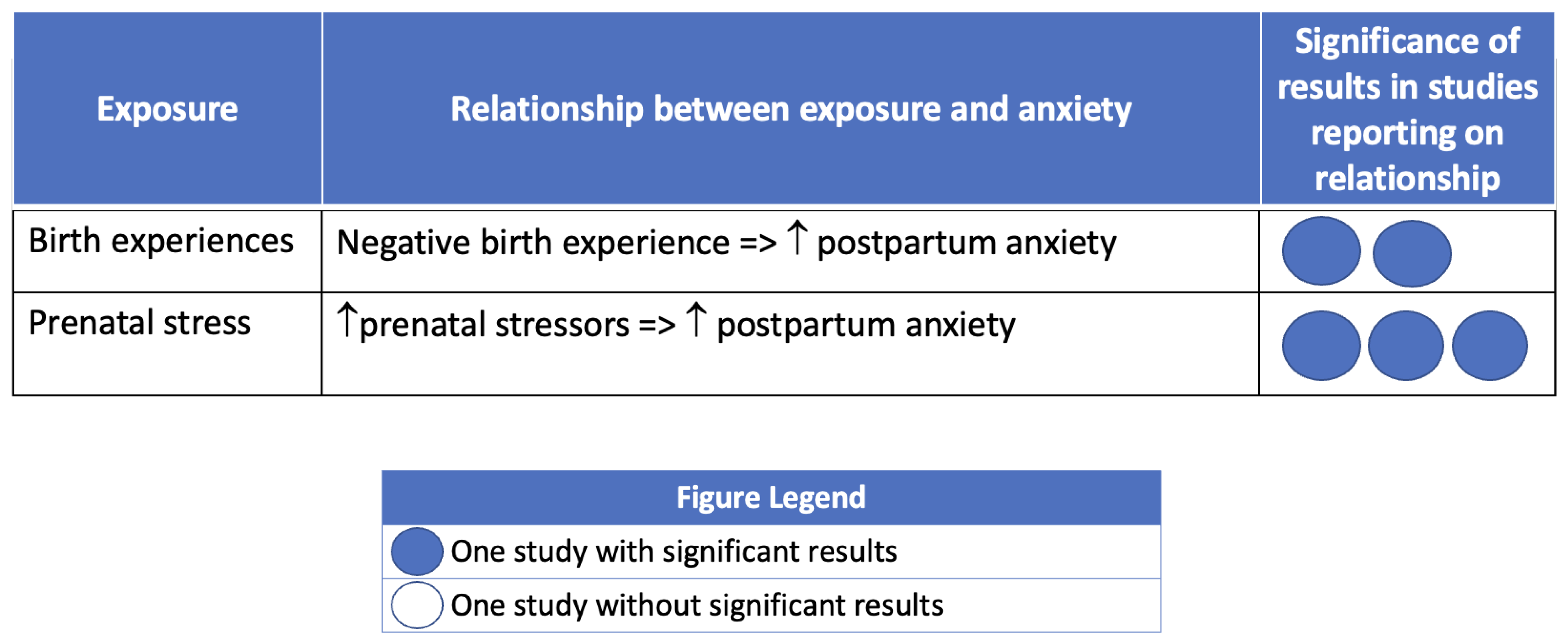

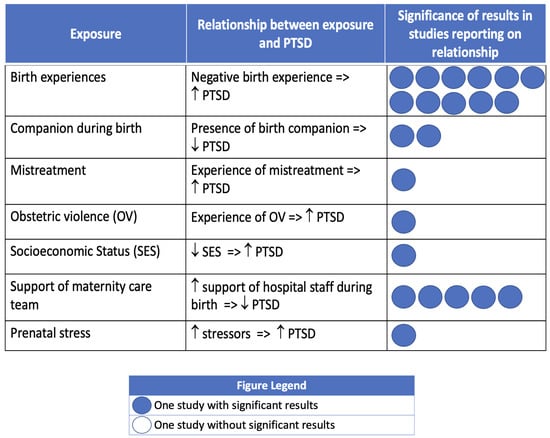

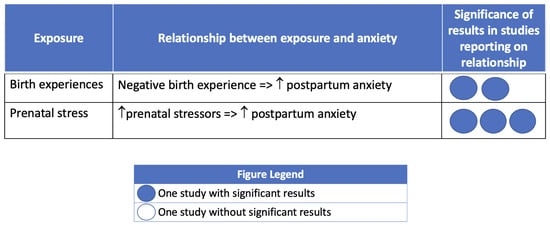

Most studies that investigated associations between social context and PMADs reported significant associations between at least one exposure and PPD, postpartum anxiety, or birth-related PTSD. Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 summarize the findings, organized by PMAD outcome.

Figure 2.

Postpartum Depression (PPD) and social context of pregnancy and birth. Note: Circles are used to represent an included study reporting on the association of the PMAD outcome with the exposure of interest. Dark circles indicate that the study found a significant association between the exposure and PMAD. Empty circles indicate that the study did not have significant findings regarding the exposure and PMAD.

Figure 3.

Birth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and social context of pregnancy. Note: Circles are used to represent an included study reporting on the association of the PMAD outcome with the exposure of interest. Dark circles indicate that the study found a significant association between the exposure and PMAD. Empty circles indicate that the study did not have significant findings regarding the exposure and PMAD.

Figure 4.

Postpartum anxiety and social context of pregnancy. Note: Circles are used to represent an included study reporting on the association of the PMAD outcome with the exposure of interest. Dark circles indicate that the study found a significant association between the exposure and PMAD. Empty circles indicate that the study did not have significant findings regarding the exposure and PMAD.

3.3. Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression (PPD) was the most frequently investigated PMAD (n= 62). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [132] was the most commonly used measure of postpartum depression (n = 48). Severity of PPD symptoms was assessed by raw score, with a cutoff score (most often ≥10) to indicate a diagnosis of PPD.

In 9 of the 11 studies exploring associations with birth experiences, having a negative birth experience significantly increased the likelihood of PPD symptoms (n = 4) and diagnosis (n = 5). Experiencing mistreatment by maternity care personnel was significantly associated with increased PPD symptoms (n = 1) [101] and diagnosis (n = 2) [89,108]. Similarly, experiencing obstetric violence was associated with a greater likelihood of PPD diagnosis (n = 3) [93,110,113]. Fourteen out of fifteen studies found that PPD symptoms (n = 9) and diagnosis (n = 5) significantly increased with increasing levels of socioeconomic disadvantage. Two studies evaluated discrimination and PPD, but neither reported significant associations [92,124]. Stress in the form of daily stressors and/or stressful life events was the most commonly investigated exposure in relationship to PPD (n = 21). Seventeen studies found that as prenatal stress increased, symptoms (n = 7) and diagnosis (n = 10) of PPD significantly increased.

3.4. Birth-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Eighteen studies evaluated relationships between exposures of interest and birth-related PTSD. Birth-related PTSD was most commonly measured by the City Birth Trauma Scale (CBTS; n = 5) [133] and the Impact of Event Scale (IES; n = 5) [134,135]. The CBTS was published in 2018, thus, only the more recent studies have used this measure.

The two most investigated exposures related to birth-related PTSD were birth experiences (n = 11) and support from the maternity care team during labor and birth (n = 5). A negative birth experience was significantly associated with increased PTSD symptoms (n = 5) and diagnosis (n = 6). Participants who felt more supported during labor and birth by their maternity care team reported significantly decreased PTSD symptoms (n = 5). Similarly, the presence of a companion or doula during labor and birth was associated with significantly fewer symptoms of PTSD (n = 4) [75,111,113,117]. The influence of mistreatment and obstetric violence on PTSD were investigated in one study each [89,117]. Experiencing mistreatment from the healthcare team was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of PTSD diagnosis [89], while experiencing obstetric violence was associated with a significant increase in PTSD symptoms [117]. One study reported that as socioeconomic status decreased, PTSD diagnosis significantly increased [67]. One additional study reported on the association between prenatal stress and PTSD, and found that as stress increased, PTSD symptoms significantly increased [68].

3.5. Postpartum Anxiety

Five studies evaluated associations between exposures of interest and postpartum anxiety. Postpartum anxiety was most commonly measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; n = 3) [136]. Participants who reported a negative birth experience were more likely to have postpartum anxiety in two studies [60,106]. Three studies found a significant relationship between prenatal stress and postpartum anxiety [68,72,105].

3.6. Studies including Biomarkers of Stress and Weathering

Our search identified 14 studies that evaluated relationships between biological measures of stress and weathering and our exposures and/or outcomes of interest (Table 2). A portion of the included studies did not report any significant findings, and another set had conflicting results and/or minimal results of significance supporting the associations explored (Figure 5). Biomarkers investigated included: allostatic load, DNA methylation, hair cortisol, inflammatory markers/cytokines, telomere length, and maternal epigenetic age.

Figure 5.

Evidence for associations between biomarkers of stress and weathering and social context/maternal mental health outcomes. Note: Circles are used to represent an individual included study reporting on the association of the PMAD outcome with the exposure of interest. Dark circles indicate that the study found a significant association between the exposure and PMAD. Empty circles indicate that the study did not have significant findings regarding the exposure/PMAD and the biomarker of interest.

Allostatic load and DNA methylation did not have a significant association with PMADs or our exposures of interest. One study explored allostatic load in a US sample of 845 individuals, and did not find significant associations between allostatic load and stress, PPD, nor postpartum anxiety [118]. Similarly, there was no evidence of a significant relationship between DNA methylation and PPD in one study exploring this biomarker in 36 Japanese individuals [127].

This review identified conflicting evidence in research exploring an associations with hair cortisol. In a prospective longitudinal study of 44 women in Southern Spain, Caparros-Gonzalez and colleagues found that first and third trimester hair cortisol levels were significantly associated with PPD symptoms [122]. In contrast, among 196 individuals in Germany, Stickel and colleagues did not find a significant relationship between hair cortisol and prenatal stress, nor between hair cortisol and PPD [131].

Biological indicators of inflammation were explored in seven studies, with mixed results. Two research teams found an inverse association between levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-4, IL-6, IL-10) and PPD symptoms [128,130]. Two studies found an inverse association between PPD symptoms and TNFα (a proinflammatory marker), but no significant associations among the other inflammatory markers investigated [121,123]. In a Thai study with 71 participants, Roomruangwong and colleagues found increased C-reactive protein (CRP) was associated with a researcher-created composite score for PPD symptoms; however, CRP levels did not significantly predict EPDS scores [129]. Studies by Brann and colleagues and Bianciardi and colleagues failed to find any significant associations between markers of inflammation and PPD [119,120].

Results on maternal epigenetic age and social context displayed an unanticipated direction of the findings in the one included study. In a U.S.-based study using repeated measures of DNA methylation from two separate longitudinal cohorts of pregnant individuals (total N = 229), an unexpected finding that decreased maternal epigenetic age was found to be significantly associated with prenatal stress (PSS score) in the Black/African American subset of one of the cohorts. No significant findings were found among the subset of European/White participants [126].

In a longitudinal cohort study of 150 Latina women in the U.S., Incollingo Rodriguez and colleagues found that telomere length was a significant negative predictor of EPDS score/PPD. In the same study, telomere length was not associated with participants’ experiences of discrimination [124].

4. Discussion

This review demonstrates that postpartum mental health outcomes are directly related to the role and behaviors of perinatal health care providers and staff. Specifically, researchers found that experiencing mistreatment and obstetric violence are associated with adverse mental health outcomes, whereas having a supportive maternity care team and birth companion (such as a doula) were associated with more positive mental health outcomes.

Recognizing the important influence of quality of care on maternal and infant birth outcomes, including maternal mental health, the World Health Organization has stated that service users’ experiences of maternity care are an equal contributor to quality-of-care metrics as is the clinical care provided [137,138]. Respectful maternity care is an integral part of high quality care [139] that improves experiences of care and addresses health inequities [140]. Research has demonstrated that marginalized individuals experience care that is less respectful and, relatedly, have higher rates of PMADs [27,28,29,141,142,143,144]. Similarly, a recent systematic review specifically looking at obstetric violence and maternal mental health found a significant association between experiences of obstetric violence and PPD and birth-related PTSD [145]. Conversely, more respectful, person-centered maternity care has been shown to improve birth outcomes [33].

Many of the exposures we evaluated had a significant association with PMADs, and are directly related to the role and behaviors of the personnel on the maternity care team (i.e., mistreatment, obstetric violence, birth experience, support of maternity care team, presence of a birth companion). We postulate that the very process of receiving care for pregnancy and birth may be iatrogenically contributing [146,147] to inequities in maternal mental health, especially for marginalized women and birthing people who report more negative care experiences and mistreatment and higher rates of PMADs.

This review did not identify studies reporting significant associations between discrimination and PMADs. It is possible that individuals who experienced discrimination from clinicians during perinatal care would be less likely to continue engagement with the healthcare system or research in the postpartum period [148,149] due to a decreased trust of their healthcare team [150]. Decreased engagement would lead to lower rates of postpartum screening and diagnosis of PMADs, as well as other significant postpartum morbidities, for individuals exposed to discrimination.

There is increasing evidence that biological changes related to social context, stress, and discrimination may contribute to negative birth outcomes [151,152,153,154,155,156]. In this review, we identified only a small number of studies that specifically explored the relationship between biological markers of weathering and PMADs. Studies varied widely in sample size, study design, biological markers measured and had inconsistent findings. Further research should explore associations between biological indicators of weathering and a holistic set of biopsychosocial birth outcomes, including perinatal mental health. This research is most needed among marginalized women and childbearing people who have higher rates of mistreatment, discrimination, and mental health complications, and are at greater risk for adverse postpartum and neonatal outcomes. Given the potential for negative experiences to affect multiple generations through fetal intrauterine programming in the prenatal period [157], this research is critical for mitigating health inequities across multiple generations.

Limitations. Although the search strategy for this review was comprehensive and systematic, it is possible that it excluded some studies that may have strengthened or disconfirmed the study findings. It is possible that publication bias reduced the number of null findings in existent literature, given that many of the studies that included biomarkers reported null or weakly significant findings. An additional limitation of this review is that studies did not generally include individuals with preexisting mental health diagnoses, which are a known risk factor for PMADs. Therefore, results from this review cannot be generalized to this high-risk group. Finally, we recognize that there are many forms of marginalization based on gender, sexual orientation, language/immigration status, rural residence, and intersections thereof that may also affect postpartum mental health that were not explored in this review.

Implications for practice, policy, and research. Our findings have highlighted areas of the social context of perinatal care that can be improved to potentially decrease the incidence of PMADs and associated morbidity and mortality. This research can be used to inform social policy and develop clinical interventions to decrease iatrogenic influences on PMADs. It may also guide patient-centered research to improve perinatal care experiences, as well as the development of interventions and social policies to alleviate stress and improve socioeconomic standing for those at highest risk of PMADs. Further research into mutable social influences on perinatal mental health and their biologic underpinnings can help to design and tailor targeted effective treatments and prevention measures, especially for those most at risk for negative outcomes.

Clinical practice changes that improve the experience of the clinician-service user interaction may directly influence the iatrogenic influences on PMADS. By further emphasizing techniques that are well-evidenced in the literature, such as providing respectful, person-centered care to all patients, improving provider-patient communication, increasing their use of shared decision making practices, and supporting patients’ use of doulas or birth companions, providers may alleviate stress associated with interactions with the maternity healthcare team or service users’ perceptions of mistreatment [141,158,159,160]. Providing additional supports for persons experiencing socioeconomic stressors by increasing tailored referrals to supportive services (i.e., food and housing supports, diaper banks, social services providing infant-care supplies, social work services, and low- or no-cost doula services) may reduce socioeconomic stressors in the perinatal period that have been found to be associated with increased rates of PMADs in this review.

Combining clinical practice improvements with social policy changes is especially important to consider, given that marginalized women and birthing people who are most likely to experience mistreatment from their healthcare team are also facing an increased incidence of the non-medical social contributors to PMADs identified in this review, such as multiple prenatal stressors and socioeconomic disadvantage. These non-medical social contributors are largely a result of systemic marginalization, structural racism, and oppression [161,162,163,164,165], and warrant large-scale social policy intervention to mitigate their effects on perinatal mental health and other birth-related outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, social context and the experience of perinatal care are associated with postpartum mental health outcomes. Individuals who experienced socioeconomic disadvantage and related stressors, and those who experienced mistreatment or obstetric violence, were most likely to experience PMADs. Therefore, increasing delivery of respectful maternity care and broad systemic and structural improvement of socioeconomic circumstances is necessary to reduce postpartum mental health inequities, especially for those made marginal by systemic oppression.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph21040480/s1, Table S1: Locations of included studies; Full search strategy. Link to review protocol registration at OSF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.-I., R.S. and J.C.; methodology, B.B.-I., T.L.M. and J.B.; software, J.B.; validation, A.S.; formal analysis, B.B.-I. and R.S.; investigation, B.B.-I. and R.S.; data curation, B.B.-I., R.S. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.-I., R.S. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, B.B.-I., J.C., T.L.M., A.S., J.B. and R.S.; visualization, B.B.-I.; supervision and project administration, B.B.-I.; funding acquisition, B.B.-I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Bridget Basile-Ibrahim received funding support from CTSA Grant Number KL2 TR001862 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Trost, S.; Beauregard, J.; Chandra, G.; Njie, F.; Berry, J.; Harvey, A.; Goodman, D.A. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019. Education 2022, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Declercq, E.; Zephyrin, L. Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States: A Primer. Commonw. Fund 2021, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Luca, D.L.; Margiotta, C.; Staatz, C.; Garlow, E.; Christensen, A.; Zivin, K. Financial Toll of Untreated Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders among 2017 Births in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, L.M.; Chen, J.; Cox, S.; Luo, F.; Robbins, C.L.; Tevendale, H.D.; Li, R.; Ko, J.Y. Healthcare Utilization and Costs Associated with Perinatal Depression among Medicaid Enrollees. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 62, e333–e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shuai, H.; Cai, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, W.; Krabbendam, E.; Liu, S.; et al. Mapping Global Prevalence of Depression among Postpartum Women. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of Maternal Postpartum Depression: A Systematic review of Maternal and Infant Outcomes. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netsi, E.; Pearson, R.M.; Murray, L.; Cooper, P.; Craske, M.G.; Stein, A. Association of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression with Child Outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, J.L.; Jones, E.J.; Bohn, D.; Mccage, S.; Parker, J.G.; Parker, M.; Pierce, S.L.; Campbell, J. Maternal Mortality among American Indian/Alaska Native Women: A Scoping Review. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramdas, D.L.; Sbrilli, M.D.; Laurent, H.K. Impact of Maternal Trauma-Related Psychopathology and Life Stress on HPA Axis Stress Response. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 25, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmir, R.; Schmied, V.; Wilkes, L.; Jackson, D. Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of a Traumatic Birth: A Meta-Ethnography. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2142–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.T.; Casavant, S. Synthesis of Mixed Research on Posttraumatic Stress Related to Traumatic Birth. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2019, 48, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soet, J.E.; Brack, G.A.; DiIorio, C. Prevalence and Predictors of Women’s Experience of Psychological Trauma during Childbirth. Birth 2003, 30, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creedy, D.K.; Shochet, I.M.; Horsfall, J. Childbirth and the Development of Acute Trauma Symptoms: Incidence and Contributing Factors. Birth 2000, 27, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, G.; Thomson, G. Tormented by Ghosts from Their Past’: A Meta-Synthesis to Explore the Psychosocial Implications of a Traumatic Birth on Maternal Well-Being. Midwifery 2014, 30, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reno, R.; Burch, J.; Stookey, J.; Jackson, R.; Joudeh, L.; Guendelman, S. Preterm Birth and Social Support Services for Prenatal Depression and Social Determinants. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, P.D.; Entringer, S.; Buss, C.; Lu, M.C. The Contribution of Maternal Stress to Preterm Birth: Issues and Considerations. In Clinics in Perinatology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 351–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Coxe, S.; Fennie, K.; Madhivanan, P.; Trepka, M.J. Stressful Life Event Experiences of Pregnant Women in the United States: A Latent Class Analysis. Women’s Health Issues 2017, 27, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonderlund, A.L.; Schoenthaler, A.; Thilsing, T. The Association between Maternal Experiences of Interpersonal Discrimination and Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Landrian, A.; Golub, G.; Cotter, S.Y.; Afulani, P. Person-Centered Maternity Care and Postnatal Health: Associations with Maternal and Newborn Health Outcomes. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2021, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy-Moulton, K.; Miller, S.; Persson, P.; Rossin-Slater, M.; Wherry, L.; Aldana, G. Nber Working Paper Series Maternal and Infant Health Inequality: New Evidence from Linked Administrative Data; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022.

- Pearl, M.; Ahern, J.; Hubbard, A.; Laraia, B.; Shrimali, B.P.; Poon, V.; Kharrazi, M. Life-Course Neighbourhood Opportunity and Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Risk of Preterm Birth. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2018, 32, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K.A.; MacDonald, I.; Chambers, T.; Ospina, M.B. Postpartum Mental Health Disorders in Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2019, 41, 1470–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estriplet, T.; Morgan, I.; Davis, K.; Crear Perry, J.; Matthews, K. Black Perinatal Mental Health: Prioritizing Maternal Mental Health to Optimize Infant Health and Wellness. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 807235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadson, A.; Akpovi, E.; Mehta, P.K. Exploring the Social Determinants of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Prenatal Care Utilization and Maternal Outcome. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Khemet Taiwo, T.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; Mclemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E.; et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers Study: Inequity and Mistreatment during Pregnancy and Childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile Ibrahim, B.; Knobf, M.T.; Shorten, A.; Vedam, S.; Cheyney, M.; Illuzzi, J.; Kennedy, H.P. “I Had to Fight for My VBAC”: A Mixed Methods Exploration of Women’s Experiences of Pregnancy and Vaginal Birth after Cesarean in the United States. Birth 2020, 48, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile Ibrahim, B.B.; Kozhimannil, K.B. Racial Disparities in Respectful Maternity Care during Pregnancy and Birth after Cesarean in Rural United States. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs. 2023, 52, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile Ibrahim, B.; Kennedy, H.P.; Combellick, J. Experiences of Quality Perinatal Care during the US COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2021, 66, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile Ibrahim, B.; Vedam, S.; Illuzzi, J.; Cheyney, M.; Kennedy, H.P. Inequities in Quality Perinatal Care in the United States during Pregnancy and Birth after Cesarean. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, R.G.; McLemore, M.R.; Julian, Z.; Stoll, K.; Malhotra, N.; Vedam, S. Coercion and Non-Consent during Birth and Newborn Care in the United States. Birth 2022, 49, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.J.; Truong, S.; DeAndrade, S.; Jacober, J.; Medina, M.; Diouf, K.; Meadows, A.; Nour, N.; Schantz-Dunn, J. Respectful Maternity Care in the United States—Characterizing Inequities Experienced by Birthing People. Matern. Child Health J. 2024, 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamoud, Y.A.; Cassidy, E.; Fuchs, E.; Womack, L.S.; Romero, L.; Kipling, L.; Oza-Frank, R.; Baca, K.; Galang, R.R.; Stewart, A.; et al. Vital Signs: Maternity Care Experiences—United States, April 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2023, 72, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, L.B.; Ranchoff, B.L.; Paterno, M.T.; Kjerulff, K.H. Person-Centered Maternity Care and Health Outcomes at 1 and 6 Months Postpartum. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T. The Weathering Hypothesis and the Health of African-American Women and Infants: Evidence and Speculations. Ethn. Dis. 1992, 2, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Hicken, M.; Keene, D.; Bound, J. “Weathering” and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Pearson, J.A.; Linnenbringer, E.; Schulz, A.J.; Reyes, A.G.; Epel, E.S.; Lin, J.; Blackburn, E.H. Race-Ethnicity, Poverty, Urban Stressors, and Telomere Length in a Detroit Community-Based Sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2015, 56, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.F.; Edwards, E.M.; Horbar, J.D.; Howell, E.A.; Mccormick, M.C.; Pursley, D.M. The Color of Health: How Racism, Segregation, and Inequality Affect the Health and Well-Being of Preterm Infants and Their Families. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 87, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prather, C.; Fuller, T.R.; Jeffries, W.L.; Marshall, K.J.; Howell, A.V.; Belyue-Umole, A.; King, W. Racism, African American Women, and Their Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Review of Historical and Contemporary Evidence and Implications for Health Equity. In Health Equity; Mary Ann Liebert Inc.: New Rochelle, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildsmith, E. Testing the Weathering Hypothesis among Mexican-Origin Women. Ethn. Dis. 2002, 12, 470–479. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, J.F.; Portillo, C.J. Understanding Native Women’s Health: Historical Legacies. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2009, 20, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Bécares, L.; Erbetta, K.; Bettegowda, V.R.; Ahluwalia, I.B. Racial/Ethnic Inequities in Low Birth Weight and Preterm Birth: The Role of Multiple Forms of Stress. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.A. Birth Weight and Maternal Age among American Indian/Alaska Native Mothers: A Test of the Weathering Hypothesis. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Engelman, M.; Mikulas, A.; Malecki, K. How Are Social Determinants of Health Integrated into Epigenetic Research? A Systematic Review. In Social Science and Medicine; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; p. 113738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggan, K.A.; Gilbert, A.; Allyse, M.A. Acknowledging and Addressing Allostatic Load in Pregnancy Care. In Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, A.T.; Crookes, D.M.; Suglia, S.F.; Demmer, R.T. The Weathering Hypothesis as an Explanation for Racial Disparities in Health: A Systematic Review. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 33, 1–18.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.L.; Ghastine, L.; Lodge, E.K.; Dhingra, R.; Ward-Caviness, C.K. Understanding Health Inequalities Through the Lens of Social Epigenetics. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, K.A.; Jorm, A.F.; Parslow, R.A.; Christensen, H. Is Telomere Length a Biomarker of Aging? A Review. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2011, 66, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, E.E.; Alsaggaf, R.; Katta, S.; Dagnall, C.; Aubert, G.; Hicks, B.D.; Spellman, S.R.; Savage, S.A.; Horvath, S.; Gadalla, S.M. Telomere Length and Epigenetic Clocks as Markers of Cellular Aging: A Comparative Study. GeroScience 2022, 44, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, C.A. Connecting the Biology of Stress, Allostatic Load and Epigenetics to Social Structures and Processes. Neurobiol. Stress 2022, 17, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Seeman, T. Protective and Damaging Effects of Mediators of Stress. Elaborating and Testing the Concepts of Allostasis and Allostatic Load. In Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; New York Academy of Sciences: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 896, pp. 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juster, R.P.; McEwen, B.S.; Lupien, S.J. Allostatic Load Biomarkers of Chronic Stress and Impact on Health and Cognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 35, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GDP per Capita (Current US$)—OECD Members|Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=OE&most_recent_value_desc=true (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Williams, C.R.; Jerez, C.; Klein, K.; Correa, M.; Belizán, J.M.; Cormick, G. Obstetric Violence: A Latin American Legal Response to Mistreatment during Childbirth. BJOG 2018, 125, 1208–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, M.; Santos, M.J.; Ruiz-Berdún, D.; Rojas, G.L.; Skoko, E.; Gillen, P.; Clausen, J.A. Moving beyond Disrespect and Abuse: Addressing the Structural Dimensions of Obstetric Violence. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.M. A Concept Analysis of Obstetric Violence in the United States of America. Nurs. Forum. 2020, 55, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallicoat, B.; Uphoff, E.P.; Pickett, K.E. Estimating Social Gradients in Health for UK Mothers and Infants of Pakistani Origin: Do Latent Class Measures of Socioeconomic Position Help? J. Immigr. Minor Health 2020, 22, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcorn, K.L.; O’Donovan, A.; Patrick, J.C.; Creedy, D.; Devilly, G.J. A Prospective Longitudinal Study of the Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Resulting from Childbirth Events. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhasanat, D.; Fry-Mccomish, J.; Yarandi, H.N. Risk For Postpartum Depression among Immigrant Arabic Women in the United States: A Feasibility Study. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2017, 62, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catala, P.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Marin, D.; Peñacoba, C. Predicting Postpartum Post-Traumatic Stress and Depressive Symptoms in Low-Risk Women from Distal and Proximal Factors: A Biopsychosocial Prospective Study Using Structural Equation Modeling. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cena, L.; Mirabella, F.; Palumbo, G.; Gigantesco, A.; Trainini, A.; Stefana, A. Prevalence of Maternal Antenatal and Postnatal Depression and Their Association with Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Factors: A Multicentre Study in Italy. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clout, D.; Brown, R. Sociodemographic, Pregnancy, Obstetric, and Postnatal Predictors of Postpartum Stress, Anxiety and Depression in New Mothers. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 188, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, S.S.; Gonzales, N.A.; Luecken, L.J.; Crnic, K.A. Multiple Domains of Stress Predict Postpartum Depressive Symptoms in Low-Income Mexican American Women: The Moderating Effect of Social Support. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruise, S.M.; Layte, R.; Stevenson, M.; O’Reilly, D. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Depression and Depression-Related Healthcare Access in Mothers of 9-Month-Old Infants in the Republic of Ireland. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, S.; Vercauteren, T.; Tersago, J.; Jacquemyn, Y.; Raes, F.; Franck, E. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after Childbirth and the Influence of Maternity Team Care during Labour and Birth: A Cohort Study. Midwifery 2016, 32, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, S.L.; Pritchard, A.; Lowder, E.M.; Janssen, P.A. Intimate Partner Abuse before and during Pregnancy as Risk Factors for Postpartum Mental Health Problems. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, D. Ethnicity, Psychosocial Risk, and Perinatal Depression-a Comparative Study among Inner-City Women in the United Kingdom. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, B.; Galletly, C.; Semmler-Booth, T.; Dekker, G. Does Antenatal Screening for Psychosocial Risk Factors Predict Postnatal Depression? A Follow-up Study of 154 Women in Adelaide, South Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2008, 42, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertan, D.; Hingray, C.; Burlacu, E.; Sterlé, A.; El-Hage, W. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Childbirth. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, S.L.; Dietz, P.M.; O’Hara, M.W.; Burley, K.; Ko, J.Y. Postpartum Anxiety and Comorbid Depression in a Population-Based Sample of Women. J. Women’s Health 2014, 23, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.; Ayers, S. Support during Birth Interacts with Prior Trauma and Birth Intervention to Predict Postnatal Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1553–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garthus-Niegel, S.; Von Soest, T.; Vollrath, M.E.; Eberhard-Gran, M. The Impact of Subjective Birth Experiences on Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms: A Longitudinal Study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2013, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelzalts, J.E.; Levy, S.; Ayers, S.; Krissi, H.; Peled, Y. Two Are Better than One? The Impact of Lay Birth Companions on Childbirth Experiences and PTSD. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2022, 25, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelzalts, J.E.; Levy, S.; Krissi, H.; Peled, Y. Epidural Analgesia Associations with Depression, PTSD, and Bonding at 2 Months Postpartum. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 43, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.E.; Ayers, S.; Quigley, M.A.; Stein, A.; Alderdice, F. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Postpartum Posttraumatic Stress in a Population-Based Maternity Survey in England. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, A.; Rauh, C.; Engel, A.; Häberle, L.; Dammer, U.; Voigt, F.; Fasching, P.A.; Faschingbauer, F.; Burger, P.; Beckmann, M.W.; et al. Socioeconomic Status and Depression during and after Pregnancy in the Franconian Maternal Health Evaluation Studies (FRAMES). Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Molina-Alarcón, M.; Infante-Torres, N.; Rubio-Álvarez, A.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M. Perinatal Factors Related to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms 1–5 Years Following Birth. Women Birth 2020, 33, e129–e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L.; Sellwood, W.; Slade, P. Birth Experiences, Trauma Responses and Self-Concept in Postpartum Psychotic-like Experiences. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 197, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P.A.; Heaman, M.I.; Urquia, M.L.; O’Campo, P.J.; Thiessen, K.R. Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression among Abused and Nonabused Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 207, 489.e1–489.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.E.; Tang, M.; Folger, A.; Ammerman, R.T.; Hossain, M.M.; Short, J.; Van Ginkel, J.B. Neighborhood Effects on PND Symptom Severity for Women Enrolled in a Home Visiting Program. Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katon, W.; Russo, J.; Gavin, A. Predictors of Postpartum Depression. J. Women’s Health 2014, 23, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Geppert, J.; Quan, T.; Bracha, Y.; Lupo, V.; Cutts, D.B. Screening for Postpartum Depression among Low-Income Mothers Using an Interactive Voice Response System. Matern. Child Health J. 2012, 16, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjerulff, K.H.; Attanasio, L.B.; Sznajder, K.K.; Brubaker, L.H. A Prospective Cohort Study of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Maternal-Infant Bonding after First Childbirth HHS Public Access. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 144, 110424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, C.L.; Liepman, M.R.; Shama Tareen, R.; Florian, P.; Charoth, R.M.; Haas, S.S.; McKean, J.W.; Moe, A.; Wiley, J.; Curtis, A. Intimate Partner Violence Associated with Postpartum Depression, Regardless of Socioeconomic Status. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, V.; Von Soest, T.; Kopp, M.; Wimberger, P.; Garthus-Niegel, S. Differential Predictors of Birth-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Mothers and Fathers-A Longitudinal Cohort Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCoursiere, D.Y.; Hirst, K.P.; Barrett-Connor, E. Depression and Pregnancy Stressors Affect the Association between Abuse and Postpartum Depression. Matern. Child Health J. 2012, 16, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, E.; Cortet, M.; Huissoud, C.; Desplanches, T.; Sormani, J.; Viaux-Savelon, S.; Dupont, C.; Pichon, S.; Gaucher, L. Disrespect during Childbirth and Postpartum Mental Health: A French Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.H.; Phan, J.; Yasui, M.; Doan, S. Prenatal Life Events, Maternal Employment, and Postpartum Depression across a Diverse Population in New York City. Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luecken, L.J.; Crnic, K.A.; Gonzales, N.A.; Winstone, L.K.; Somers, J.A. Mother-Infant Dyadic Dysregulation and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms in Low-Income Mexican-Origin Women. Biol. Psychol. 2019, 147, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, B.E.L.; Urbina, E.; D’Anna-Hernandez, K.L. Sociocultural Stressors Across the Perinatal Period and Risk for Postpartum Depressive Symptoms in Women of Mexican Descent. Cultur. Divers. Ethn. Minor Psychol. 2020, 26, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Vázquez, S.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M. Relationship between Perceived Obstetric Violence and the Risk of Postpartum Depression: An Observational Study. Midwifery 2022, 108, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Coxe, S.; Fennie, K.; Madhivanan, P.; Trepka, M.J. Antenatal Stressful Life Events and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms in the United States: The Role of Women’s Socioeconomic Status Indices at the State Level. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Fennie, K.; Coxe, S.; Madhivanan, P.; Trepka, M.J. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Relationship between Antenatal Stressful Life Events and Postpartum Depression among Women in the United States: Does Provider Communication on Perinatal Depression Minimize the Risk? Ethn. Health 2018, 23, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, A.; El-Khoury Lesueur, F.; Sutter-Dallay, A.L.; Franck, J.; Thierry, X.; Melchior, M.; van der Waerden, J. The Role of Prenatal Social Support in Social Inequalities with Regard to Maternal Postpartum Depression According to Migrant Status. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 272, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakić Radoš, S.; Martinić, L.; Matijaš, M.; Brekalo, M.; Martin, C.R. The Relationship between Birth Satisfaction, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Postnatal Depression Symptoms in Croatian Women. Stress Health 2022, 38, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.P.; Phipps, M.G. Postpartum Depression in Adolescent and Adult Mothers: Comparing Prenatal Risk Factors and Predictive Models. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, A.; Alcorn, K.L.; Patrick, J.C.; Creedy, D.K.; Dawe, S.; Devilly, G.J. Predicting Posttraumatic Stress Disorder after Childbirth. Midwifery 2014, 30, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Kingsley Ezeh, O.; Dhami, M.V.; Naz, S.; Khanlari, S.; Mckenzie, A.; Agho, K.; Page, A.; Ussher, J.; Perz, J.; et al. Perinatal Distress and Depression in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Australian Women: The Role of Psychosocial and Obstetric Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiz, J.C.; de Jezus Castro, S.M.; Giugliani, E.R.J.; dos Santos Ahne, S.M.; Aqua, C.B.D.; Giugliani, C. Association between Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth and Symptoms Suggestive of Postpartum Depression. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares Pinheiro, R.; Monteiro Da Cunha Coelho, F.; Azevedo Da Silva, R.; Amaral Tavares Pinheiro, K.; Pierre Oses, J.; De Ávila Quevedo, L.; Dias De Mattos Souza, L.; Jansen, K.; Maria Zimmermann Peruzatto, J.; Gus Manfro, G.; et al. Association of a Serotonin Transporter Gene Polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and Stressful Life Events with Postpartum Depressive Symptoms: A Population-Based Study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 34, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, S.K.; Proctor, E.K. A Rural Perspective on Perinatal Depression: Prevalence, Correlates, and Implications for Help-Seeking among Low-Income Women. J. Rural. Health 2009, 25, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qobadi, M.; Collier, C.; Zhang, L. The Effect of Stressful Life Events on Postpartum Depression: Findings from the 2009–2011 Mississippi Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razurel, C.; Kaiser, B.; Antonietti, J.P.; Epiney, M.; Sellenet, C. Relationship between Perceived Perinatal Stress and Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Parental Self-Efficacy in Primiparous Mothers and the Role of Social Support. Women Health 2017, 57, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L.; Henry, A.; Harvey, S.B.; Homer, C.S.E.; Davis, G.K. Depression, Anxiety and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Six Months Following Preeclampsia and Normotensive Pregnancy: A P4 Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salm Ward, T.; Kanu, F.A.; Robb, S.W. Prevalence of Stressful Life Events during Pregnancy and Its Association with Postpartum Depressive Symptoms. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.F.; Mesenburg, M.A.; Bertoldi, A.D.; De Mola, C.L.; Bassani, D.G.; Domingues, M.R.; Stein, A.; Coll, C.V.N. The Association between Disrespect and Abuse of Women during Childbirth and Postpartum Depression: Findings from the 2015 Pelotas Birth Cohort Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerlad, S.; Schermelleh-Engel, K.; La Rosa, V.L.; Louwen, F.; Oddo-Sommerfeld, S. Trait Anxiety and Unplanned Delivery Mode Enhance the Risk for Childbirth-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Women with and without Risk of Preterm Birth: A Multi Sample Path Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, K.J.; Rattner, D.; Gubert, M.B. Institutional Violence and Quality of Service in Obstetrics Are Associated with Postpartum Depression. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steetskamp, J.; Treiber, L.; Roedel, A.; Thimmel, V.; Hasenburg, A.; Skala, C. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Childbirth: Prevalence and Associated Factors—A Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, S.L.; Diop, H.; Declercq, E.; Cabral, H.J.; Fox, M.P.; Wise, L.A. Stressful Events during Pregnancy and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms. J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, A.; Yakupova, V. Past Traumatic Life Events, Postpartum PTSD, and the Role of Labor Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebeka, S.; Le Strat, Y.; Mandelbrot, L.; Benachi, A.; Dommergues, M.; Kayem, G.; Lepercq, J.; Luton, D.; Ville, Y.; Ramoz, N.; et al. Early- and Late-Onset Postpartum Depression Exhibit Distinct Associated Factors: The IGEDEPP Prospective Cohort Study. BJOG 2021, 128, 1683–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Kornfield, S.L.; White, L.K.; Chaiyachati, B.H.; Barzilay, R.; Njoroge, W.; Parish-Morris, J.; Duncan, A.; Himes, M.M.; Rodriguez, Y.; et al. Clinician-Reported Childbirth Outcomes, Patient-Reported Childbirth Trauma, and Risk for Postpartum Depression. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2022, 25, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikman, A.; Axfors, C.; Iliadis, S.I.; Cox, J.; Fransson, E.; Skalkidou, A. Characteristics of Women with Different Perinatal Depression Trajectories. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 1268–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakupova, V.; Suarez, A. Postpartum PTSD and Birth Experience in Russian-Speaking Women. Midwifery 2022, 112, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adynski, H.; Zimmer, C.; Thorp, J.; Santos, H.P. Predictors of Psychological Distress in Low-Income Mothers over the First Postpartum Year. Res. Nurs. Health 2019, 42, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianciardi, E.; Barone, Y.; Lo Serro, V.; de Stefano, A.; Giacchetti, N.; Aceti, F.; Niolu, C. Inflammatory Markers of Perinatal Depression in Women with and without History of Trauma. Riv. Psichiatr. 2021, 56, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bränn, E.; Papadopoulos, F.; Fransson, E.; White, R.; Edvinsson, Å.; Hellgren, C.; Kamali-Moghaddam, M.; Boström, A.; Schiöth, H.B.; Sundström-Poromaa, I.; et al. Inflammatory Markers in Late Pregnancy in Association with Postpartum Depression-A Nested Case-Control Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 79, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buglione-Corbett, R.; Deligiannidis, K.; Leung, K.; Zhang, N.; Lee, M.; Rosal, M.; Moore Simas, T. Expression of Inflammatory Markers in Women with Perinatal Depressive Symptoms. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Romero-Gonzalez, B.; Strivens-Vilchez, H.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.; Martinez-Augustin, O.; Peralta-Ramirez, M.I. Hair Cortisol Levels, Psychological Stress and Psychopathological Symptoms as Predictors of Postpartum Depression. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corwin, E.J.; Pajer, K.; Paul, S.; Lowe, N.; Weber, M.; McCarthy, D.O. Bidirectional Psychoneuroimmune Interactions in the Early Postpartum Period Influence Risk of Postpartum Depression. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 49, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incollingo Rodriguez, A.C.; Polcari, J.J.; Nephew, B.C.; Harris, R.; Zhang, C.; Murgatroyd, C.; Santos, H.P. Acculturative Stress, Telomere Length, and Postpartum Depression in Latinx Mothers. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 147, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katrinli, S.; Smith, A.K.; Drury, S.S.; Covault, J.; Ford, J.D.; Singh, V.; Reese, B.; Johnson, A.; Scranton, V.; Fall, P.; et al. Cumulative Stress, PTSD, and Emotion Dysregulation during Pregnancy and Epigenetic Age Acceleration in Hispanic Mothers and Their Newborn Infants. Epigenetics 2023, 18, 2231722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, E.E.; Lapato, D.M.; Jackson-Cook, C.; Strauss, J.F.; Roberson-Nay, R.; York, T.P. Maternal Biological Age Assessed in Early Pregnancy Is Associated with Gestational Age at Birth. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Nakatochi, M.; Kunimoto, S.; Okada, T.; Aleksic, B.; Toyama, M.; Shiino, T.; Morikawa, M.; Yamauchi, A.; Yoshimi, A.; et al. Methylation Analysis for Postpartum Depression: A Case Control Study. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, C.T.; Yu, Z.; Obara, T.; Ishikuro, M.; Murakami, K.; Kikuya, M.; Kikuchi, S.; Kobayashi, N.; Kudo, H.; Ogishima, S.; et al. Association between Low Levels of Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines during Pregnancy and Postpartum Depression. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 77, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomruangwong, C.; Kanchanatawan, B.; Sirivichayakul, S.; Mahieu, B.; Nowak, G.; Maes, M. Lower Serum Zinc and Higher CRP Strongly Predict Prenatal Depression and Physio-Somatic Symptoms, Which All Together Predict Postnatal Depressive Symptoms. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, W.; Steiner, M.; Coote, M.; Frey, B.N. Relationship between Inflammatory Biomarkers and Depressive Symptoms during Late Pregnancy and the Early Postpartum Period: A Longitudinal Study. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2016, 38, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickel, S.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Habel, U.; Stickeler, E.; Goecke, T.W.; Lang, J.; Chechko, N. Endocrine Stress Response in Pregnancy and 12 Weeks Postpartum—Exploring Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 125, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of Postnatal Depression. Development of the 10-Item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, S.; Wright, D.B.; Thornton, A. Development of a Measure of Postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, M.; Wilner, N.; Alvarez, W. Impact of Event Scale: A Measure of Subjective Stress. Psychosom. Med. 1979, 41, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Keane, K., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Sydeman, S.J. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory. In The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment; Maruish, M.E., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 292–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Miller, S. Transforming Intrapartum Care: Respectful Maternity Care. In Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology; Bailliere Tindall Ltd.: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçalp, O.; Were, W.M.; Maclennan, C.; Oladapo, O.T.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Bahl, R.; Daelmans, B.; Mathai, M.; Say, L.; Kristensen, F.; et al. Quality of Care for Pregnant Women and Newborns—The WHO Vision. BJOG 2015, 122, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Lalonde, A. The Global Epidemic of Abuse and Disrespect during Childbirth: History, Evidence, Interventions, and FIGO’s Mother-Baby Friendly Birthing Facilities Initiative. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 131, S49–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Basile Ibrahim, B.; Cheyney, M.; Vedam, S.; Kennedy, H.P. “I Was Able to Take It Back”: Seeking VBAC after Experiencing Dehumanizing Maternity Care in a Primary Cesarean. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2023, 4, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.R.; McLemore, M.R.; Oseguera, T.; Lyndon, A.; Franck, L.S. Listening to Women: Recommendations from Women of Color to Improve Experiences in Pregnancy and Birth Care. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2020, 65, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLemore, M.R.; Altman, M.R.; Cooper, N.; Williams, S.; Rand, L.; Franck, L. Health Care Experiences of Pregnant, Birthing and Postnatal Women of Color at Risk for Preterm Birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 201, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, M.R.; Oseguera, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Franck, L.S.; Lyndon, A. Information and Power: Women of Color’s Experiences Interacting with Health Care Providers in Pregnancy and Birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Fernandez, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Factors Associated with Obstetric Violence Implicated in the Development of Postpartum Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1553–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liese, K.L.; Davis-Floyd, R.; Stewart, K.; Cheyney, M. Obstetric Iatrogenesis in the United States: The Spectrum of Unintentional Harm, Disrespect, Violence, and Abuse. Anthropol. Med. 2021, 28, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illich, I. Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health; Calder & Boyars: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio, L.; Kozhimannil, K.B. Health Care Engagement and Follow-up after Perceived Discrimination in Maternity Care. Med. Care 2017, 55, 830–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attanasio, L.B.; Ranchoff, B.L.; Geissler, K.H. Perceived Discrimination during the Childbirth Hospitalization and Postpartum Visit Attendance and Content: Evidence from the Listening to Mothers in California Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, K.; Putt, M.; Halbert, C.H.; Grande, D.; Schwartz, J.S.; Liao, K.; Marcus, N.; Demeter, M.B.; Shea, J.A. Prior Experiences of Racial Discrimination and Racial Differences in Health Care System Distrust. Med. Care 2013, 51, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prairie, E.; Côté, F.; Tsakpinoglou, M.; Mina, M.; Quiniou, C.; Leimert, K.; Olson, D.; Chemtob, S. The Determinant Role of IL-6 in the Establishment of Inflammation Leading to Spontaneous Preterm Birth. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021, 59, 1359–6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, S.L.; Christian, L.M.; Mackos, A.R.; Nolan, T.S.; Gondwe, K.W.; Anderson, C.M.; Hall, M.W.; Williams, K.P.; Slavich, G.M. Lifetime Stressor Exposure, Systemic Inflammation during Pregnancy, and Preterm Birth among Black American Women. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giurgescu, C.; Engeland, C.G.; Zenk, S.N.; Kavanaugh, K. Stress, Inflammation and Preterm Birth in African American Women. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2013, 13, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.L.; Anderson, C.M.; MacKos, A.R.; Neiman, E.; Gillespie, S.L. Stress during Pregnancy and Epigenetic Modifications to Offspring DNA: A Systematic Review of Associations and Implications for Preterm Birth. J. Perinat. Neonatal. Nurs. 2020, 34, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hux, V.J.; Catov, J.M.; Roberts, J.M. Allostatic Load in Women with a History of Low Birth Weight Infants: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Women’s Health 2014, 23, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillippe, M. Telomeres, Oxidative Stress, and Timing for Spontaneous Term and Preterm Labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco-Miotto, T.; Craig, J.M.; Gasser, Y.P.; Van Dijk, S.J.; Ozanne, S.E. Epigenetics and DOHaD: From Basics to Birth and Beyond. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2017, 8, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile Ibrahim, B. Operationalising the Quality Maternal and Newborn Care Framework to Improve Maternity Care Quality and Health Outcomes for Marginalised Women and Childbearing People. Int. J. Birth Parent. Educ. 2023, 10, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Chinkam, S.; Ibrahim, B.B.; Diaz, B.; Steer-Massaro, C.; Kennedy, H.P.; Shorten, A. Learning from Women: Improving Experiences of Respectful Maternity Care during Unplanned Caesarean Birth for Women with Diverse Ethnicity and Racial Backgrounds. Women Birth 2023, 36, e125–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combellick, J.L.; Basile Ibrahim, B.; Julien, T.; Scharer, K.; Jackson, K.; Powell Kennedy, H. Birth during the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Childbearing People in the United States Needed to Achieve a Positive Birth Experience. Birth 2022, 49, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop-Royse, J.; Lange-Maia, B.; Murray, L.; Shah, R.C.; DeMaio, F. Structural Racism, Socio-Economic Marginalization, and Infant Mortality. Public Health 2021, 190, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Crear-Perry, J.; Richardson, L.; Tarver, M.; Theall, K. Separate and Unequal: Structural Racism and Infant Mortality in the US. Health Place 2017, 45, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, G.C.; Hicken, M.T. Structural Racism: The Rules and Relations of Inequity. Ethn. Dis. 2021, 31, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.A.; Arkin, E.; Proctor, D.; Kauh, T.; Holm, N. Systemic and Structural Racism: Definitions, Examples, Health Damages, and Approaches to Dismantling. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).