Abstract

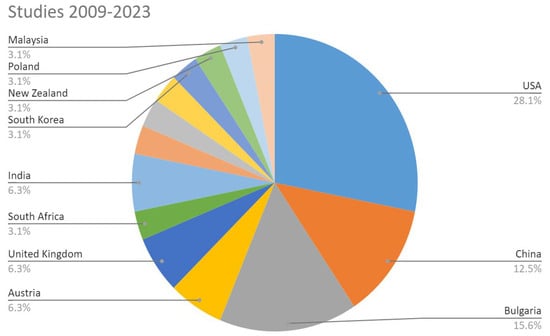

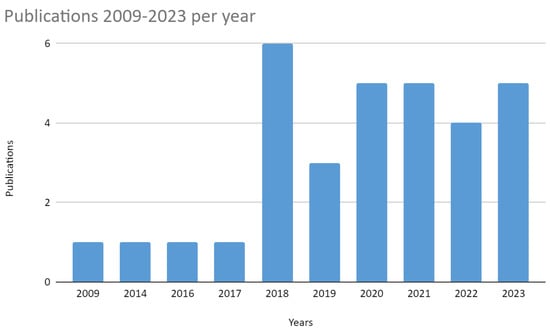

Most recent university campuses follow the North American model, built on city limits or countryside, with large separate buildings in open green spaces. Studies suggest that the prevalence and severity of mental health issues among university students has been increasing over the past decade in most countries. University services were created to face this growing problem, however individual-based interventions have limited effects on mental health and well-being of a large population. Our aim was to verify if and how the natural environment in campuses is focused on programs to cope with the issue of mental health and well-being among students. A systematic review of literature was undertaken with search in Scopus and LILACS with the keywords “green areas” AND “well-being” AND “Campus”, following PRISMA guidelines. As a result, 32 articles were selected. Research on the topic is recent, mostly in the USA, Bulgaria, and China. Most studies used objective information on campuses’ greenness and/or university students’ perception. Mental health was usually measured by validated scores. Findings of all the studies indicated positive association between campus greenery and well-being of students. We conclude that there is a large potential for use of university campuses in programs and as sites for students’ restoration and stress relief.

1. Introduction

Most of the more recent university campuses follow the North American model. They are built on the limits of the city or the countryside, with large separate buildings, implanted in open green spaces, along avenues and streets [1].

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, in the field of pedagogy, the New School movement has spread throughout the world. This movement demanded a profound renewal in the school environment, associated with a change in the way the teachers exercised authority. The proposed changes included transforming school buildings into more horizontal ones, so that they would become more open to nature [2]. In kindergarten and primary education, the principles of free movement of children and access to the outdoors and nature have been adopted in many countries. In Brazil, Anísio Teixeira defended the park-school with two periods, in which one of the periods, in a large, wooded space, children performed physical, social, and artistic activities [3]. Teixeira was a mentor to educators, such as Darci Ribeiro, who became Minister of Education.

At the university level, these principles were not so evident, but the heritage of the architectural design, with horizontal buildings and large green areas between them, was maintained.

University campuses, the majority characterized by having extensive lawns and green spaces, cause large expenditures for their maintenance, but are scarcely used as recreation or leisure areas for the well-being and mental health of students or the surrounding community. There is a large potential for their use as a natural environment for the well-being of students, teaching, office staff, and the general community.

On a university campus, greenness can include trees, vegetation, lawns, bushes, etc. that flank pathways and roads, and exist in spaces between buildings [4], as well as water bodies comprising blue spaces [5].

Student quality of life is a complex composite of physical health, psychological state, and relationships with the surrounding cultural, social, and environmental context [6], and it is an important precursor for learning and success in college [4].

University students face a series of academic, interpersonal, financial, and cultural challenges that may cause psychological and other health problems. Students’ stress may result also from difficult daily targets, long study hours, bad relationships with classmates, emotional distress, loss of self-identity, and low self-esteem [7]. Many of the young adults who attend universities face their first prolonged period away from home [8]. This change in environment, combined with academic, social, and financial pressures, can be stressful, with impacts on the physical status and wellness of students [8,9]. Ibes et al. reaffirm that the mental health crisis is particularly pronounced on college campuses, where students encounter life stressors, such as academic and extracurricular demands, relationships, financial concerns, family expectations, identity development, and racial and cultural differences [9]. Digital overload exacerbates chronic stress and anxiety, as college students tend to spend many hours a day on smartphones, tablets, computers, and television [9]. Among young adults, intense technology use may exacerbate symptoms of stress, fatigue, sleep disorders, and depression [9]. Students that do not live on campus also tend to spend the majority of their time on college campuses, more waking hours than they spend at home, due to academic tasks [4,7].

Studies suggest that the prevalence and severity of mental health issues among university students has been increasing over the past decade in North America [10]. According to the Spring 2022 data report from the National College Health Assessment of the US, 75% of college students experienced moderate to serious psychological distress, and 48% felt lonely [11]. In China [7], India [12], Canada [13], and Korea in 2019, 45% of the students suffered from depression [14], and in many other countries around the world [4], it is becoming a widespread problem that was aggravated during the COVID-19 pandemic [15,16]. This trend is apparently similar in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). For example, in Brazil, young adults (18 to 29 years old) represent the group with the lowest percentage of depression (5.9% in 2019) but presented the largest increase in diagnoses of depression from 2013 to 2019, 51%. Suicide rates among the age group 20 to 39 increased from 6.73 to 8.19 per 100,000 inhabitants in the same period [17].

According to the WHO, the most common mental health disorders, because of their high prevalence, are depression and anxiety. The first is characterized by symptoms such as sadness, low interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-esteem, changes in sleep or appetite pattern, sensation of tiredness, and low concentration. The second presents symptoms as anxiety, fear, panic, phobias, obsessive-compulsive behavior, and post-traumatic stress [18]. On top of these two common disorders, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts have become a serious problem among university students. The transition between childhood and adulthood is characterized by rapid physical, psychological, and cognitive developments and lays the foundation for future mental health and resilience. An estimated 70% of mental health problems first appear during this development period [19].

Many university services have been created to face this growing problem; however, interventions based in individuals have limited effects on the mental health and well-being of a large population. Besides, although many universities offer mental health treatment and counseling programs, a vast majority of students are reluctant to use them due to personal and public stigma [20]. Ibes et al. [9] reinforce that universities may address this crisis in traditional ways, such as counseling staff and mental health programming. Yet, an accessible, simple, and affordable tool for relieving stress, such as greenspace, is overlooked. Considering that mental health issues are complex and need a holistic approach, Windhorst and Williams [10] argue that strategies should include campus environments, such as social inclusivity, students’ safety, support services, but also the natural environment as an important dimension of mental health. In their view, this absence is striking in studies and in real health policies in Latin America [10].

Our first aim was to focus our study on Latin America’s campuses, as we teach and study in a Latin American context where young adults from low- and middle-income families are increasingly going to university, and where mental health care is underfunded. Therefore, alternative preventive strategies should be explored. However, our first literature search in Scopus and Web of Science showed no studies on the relationship between university students’ well-being or mental health and green spaces.

Wolf et al. [20], in their scoping review of literature on Urban Trees and Human Health, pointed out that of 201 studies analyzed, only one was based in Mexico, and 1% were undertaken in South America [20]. This indicates that studies on the effects of the natural environment on health are still scarce in Latin America.

According to Liu et al. [7], there are two main theoretical perspectives related to the restorative effects of natural environments: (a) The psycho-evolutionary theory holds that viewing the natural environment can improve the mood of people and mitigate stress by blocking out pessimistic thoughts and ruminations. (b) The Attention Restoration Theory (ART) holds that intensive or prolonged focus leads to exhaustion of mental capacity and that directed attention capabilities can be restored by contact with nature [7]. According to ART, the natural environment should exhibit four types of characteristics to assist in this process: a sense of escape or being away from daily’s routine, extent to invoke imagination [as in a forest trail], fascination, and be compatible with the desires of the individual. Maximum benefit is obtained when all four are present [21]. Malekinezhad et al. [22] highlight that based on the Stress Restoration Theory (SRT) and ART, restorative outcomes of natural environments have been operationalized into dimensions of “direct attention restoration”, “clearing random thoughts”, and “relaxation and calmness”. Bardhan et al. [11] consider that university students may benefit particularly strongly from nature exposure because of their high academic and social demands in preparing for professional careers. Some authors emphasize that, according to the biophilia hypothesis, humans have developed and maintained an affinity for nature throughout their evolution, which makes positive outcomes from exposure to green spaces on the human body and mind stand to reason [11,23]. Other authors emphasize mediators of this process as reduced exposure to air pollution, heat island, and noise, as well as encouraging health-enhancing behaviors such as physical activity and social interactions [5]. Other authors reinforce the salutogenesis concept, focusing on factors to promote and support human health and well-being and recognizing contact with nature as a stress-reducing health promotion tool [24].

Having a hypothesis that campus green spaces represent a valuable resource for promoting mental health among university students, we aimed to verify if and how the natural environment is approached in scientific literature on well-being in university campuses, and how it is being focused on programs and policies to cope with the growing issue of mental health among university students. Even though, in recent years, this topic has been the focus of many dispersed studies, a broad review of literature on the theme is non-existent, thus it is innovative and can point to the main findings and gaps. To address this objective, a systematic literature review was undertaken to assess the extent, range, and nature of research in this topic area.

2. Materials and Methods

The method adopted was a systematic review of literature following Prisma guidelines. The search was undertaken with no date range, in the basis Web of Science, Scopus, LILACS, and SciELO, because the focus of the last two is in Latin America, with the keywords: “green areas” AND “well-being” AND “Campus”, and variations with the words “green areas” for “greenness”, as well as translation to the words to Portuguese: “áreas verdes” AND “bem-estar” AND “campus universitário”, and Spanish: “espacios verdes” AND “bien-vivir” AND “campus universitário”. First results indicated 7 documents in Scopus, none regarding university students or young adults, and 49 in Web of Science, of which 16 focused on the relationship of mental health and greenspace in a Latin American context, but none focused on college students or young adults.

As no manuscript was found regarding studies in Latin America, our investigation focused on any region of the world. A Boolean search was performed on Scopus, LILACS, and SciELO to find publications with no initial cut-off date until February 2023. We did not use an initial cut-off date because we wanted to verify when studies on the theme started to appear in scientific literature. Data were collected from Scopus, which includes Medline and Embase databases, and demonstrated adequate results. LILACS and SciELO brought poor results. The descriptors and Boolean operators were three search strings, which were later systematized: “greenness” OR “green areas” AND “university campus” called Search 1; the second: “greenness” OR “green areas” AND “mental health” called Search 2; and the third: “university campus” AND “mental health”, called Search 3.

The inclusion criteria used were the simultaneous presence of the terms of each search in the title, or in the abstract, or in the keywords. As exclusion criteria, the following were stipulated: absence of simultaneity of the terms of each search in the title or abstract or in the keywords, articles with a study population outside the young adult age group, articles that dealt with botanical or faunal issues, sanitation, or other aspects of the university campus without association with students’ mental health or well-being. Articles that associated greenness with health issues unrelated to well-being or mental health were also discarded.

The three searches were necessary because the use of the three words concomitantly did not return any results, even without the limitation of a geographical area. The searches were separated and the relationships between their results were made manually. The analysis technique was reading and documentary analysis by the three authors, the instrument used was an Excel sheet organized in a table, and the relevant information extracted manually was authors, region of study, year of publication, objective of study, method used, sample, and results obtained.

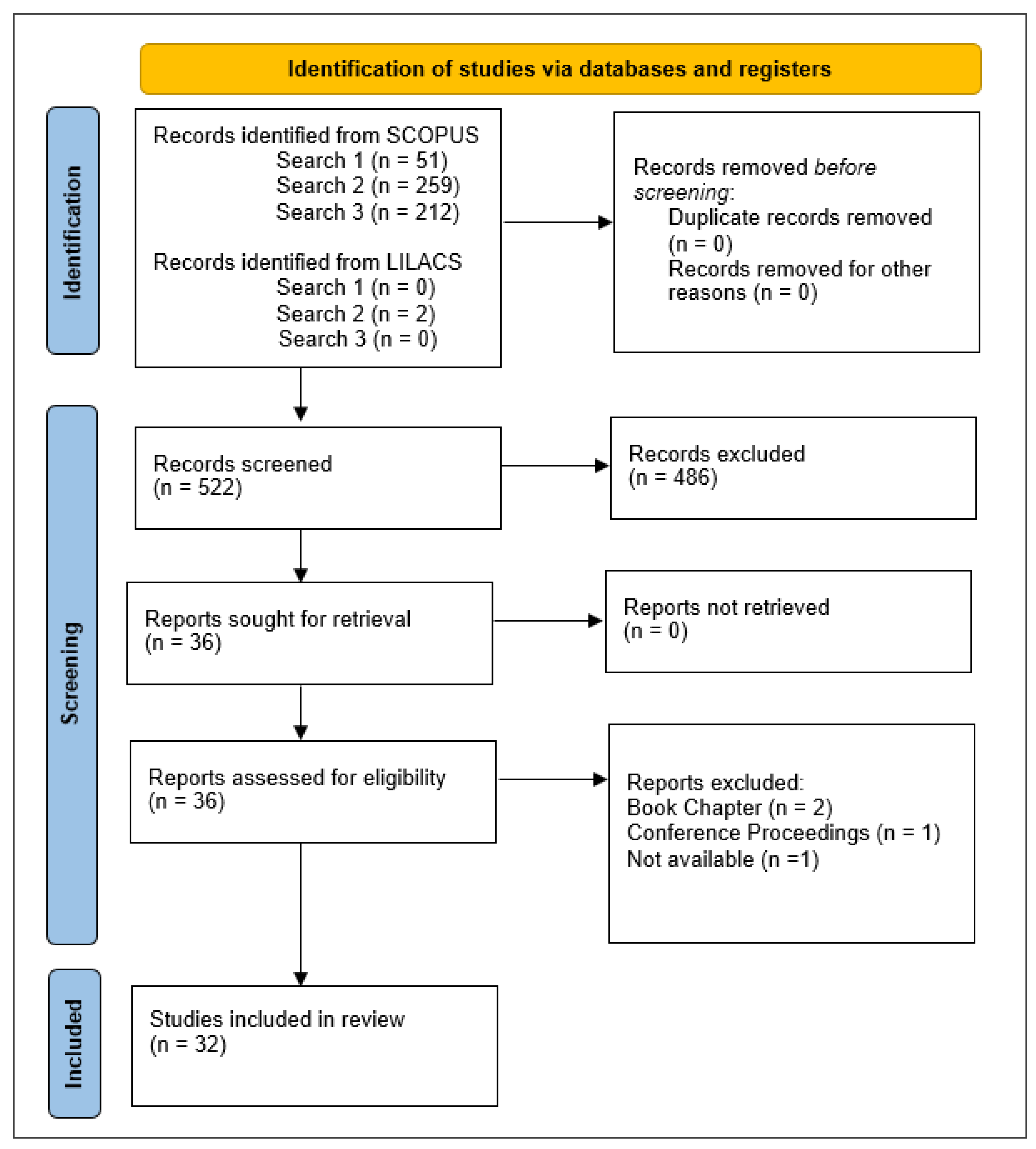

After reading the abstracts obtained in the three searches by the three authors, 36 articles were selected by consensus, of which 4 were discarded, 2 of them because they were book chapters, 1 because it was an abstract in meeting proceedings, and 1 article whose text was not available, leaving 32 studies for analysis.

The PRISMA guidelines [25] were used to organize and systematize the search and results, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search and results according to PRISMA guidelines.

3. Results

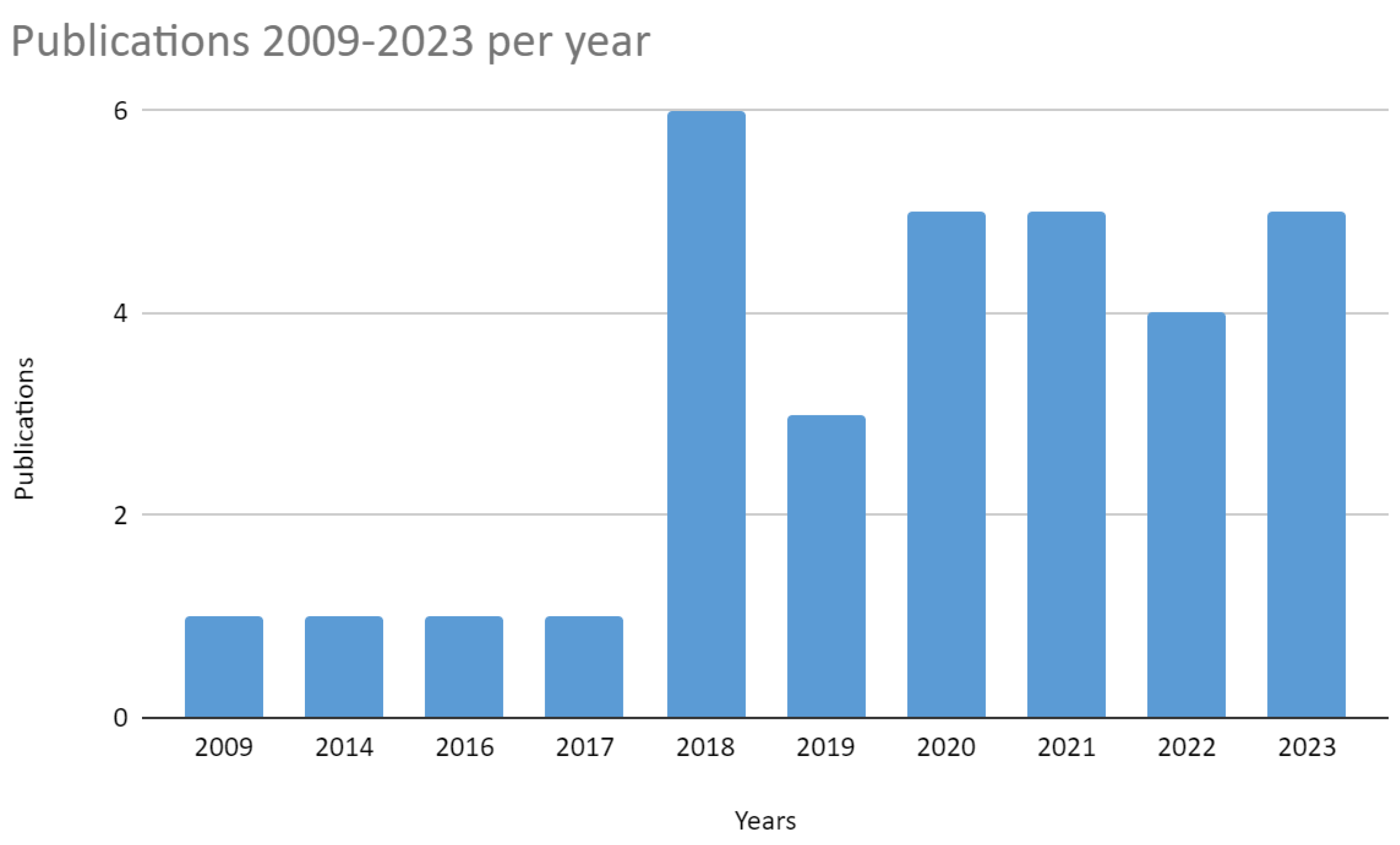

As described in the methods, in total, 32 articles were found. Of these, only two studies were published before the year 2015, in China (2009) and the United States (2014), showing that it is a recent topic in the scientific literature.

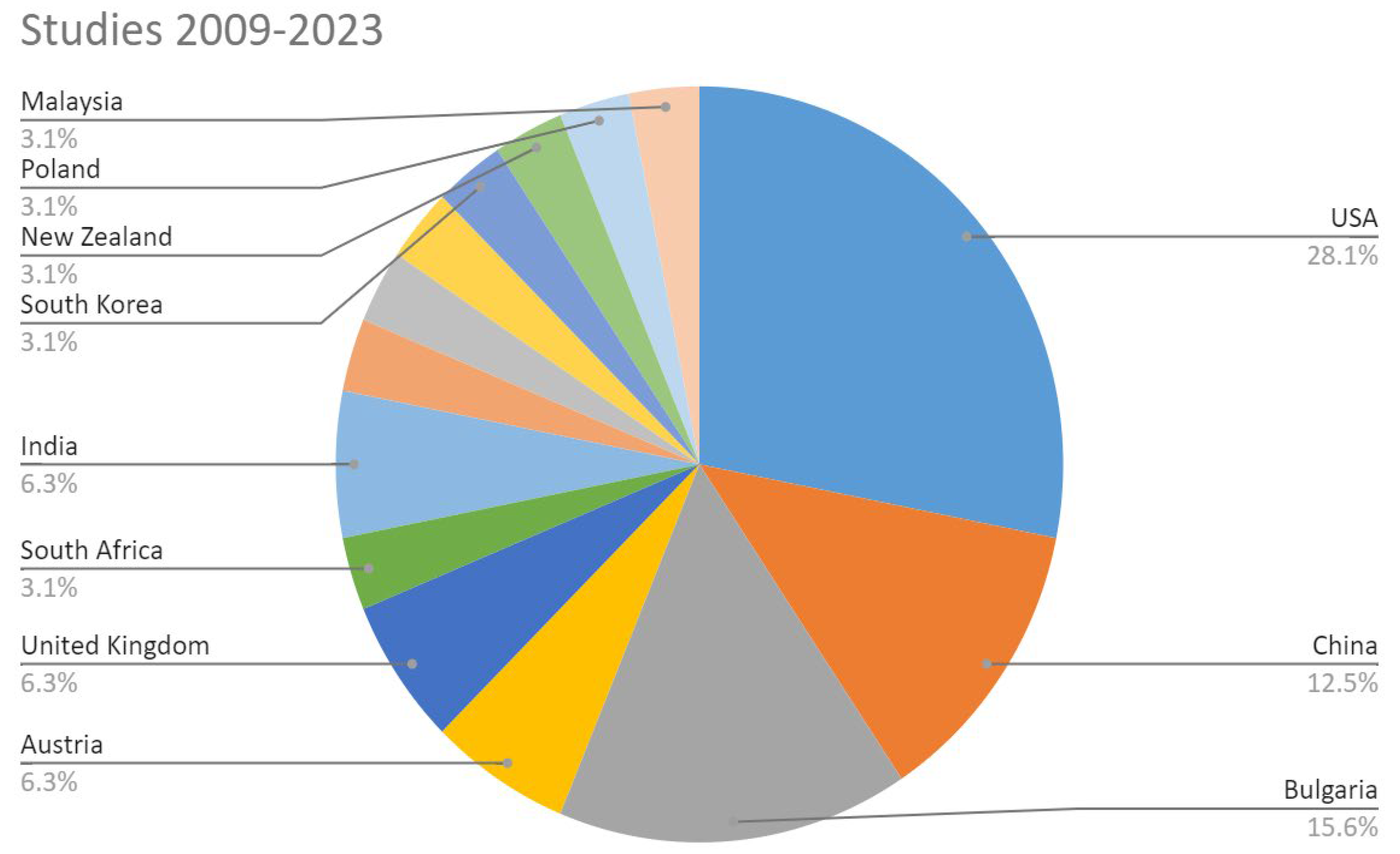

In 2016 and 2017, one paper was published in the U.S. and one in South Africa. From 2018, six studies were found, four in Bulgaria, one in the USA, and one in China. From 2019, three studies in Bulgaria, Turkey, and Canada. From 2020, there were five studies, with expansion to other countries. The theme, of recent interest, is also limited to a few countries in the world, as can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The United States, Bulgaria, and China stand out in terms of number of studies, with the exception that in Bulgaria, the studies are concentrated in one research group.

Figure 2.

Studies by country 2009–2023.

Figure 3.

Publications by year.

Results were also analyzed following PRISMA guidelines and are presented in Table 1 indicating the following aspects: year of study, authors and reference number, study location, objective, method, sample, and results.

Table 1.

Publications that related greenness, university campus, wellness or mental health.

4. Discussion

Research on the topic is recent, mostly in the northern hemisphere, and in higher-income countries. Nine studies (28%) were undertaken in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), where university degree expansion is taking place. No studies were undertaken in Latin America, showing that the focus on campus environment for the growing issue of mental health among university students is unexplored. The pressure on college students is as hard as, or even harder, than in higher income countries, due to economic hardships, and the need to work from an early age, in most cases concomitantly with academic life. Another finding is that studies are often concentrated in a research group. Among the 32 articles, nine were from repeated authors.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of open space for university students and seemed to motivate studies on the topic in more countries and areas, as most manuscripts date from 2020 on.

Regarding methods for identifying and calculating the surrounding natural environment, most studies used objective information on campuses’ greenness, based on satellite images with Normalized Difference Vegetation Index-NDVI (ten studies), vegetation index, tree cover density, and land cover database. Some research employed objective and subjective measures such as university students’ perception on the presence and quality of greenspace in campus, and a few around their residential area. Some used only perceptive values on greenness. One study used a NatureDose app with GPS and a phone sensor in the student cell phone [11], and one study was a pre-post-test randomized experiment with a 360-degree video platform via an online survey [16]. The research by Reese et al. [38] used a photovoice technique with a photvoicekit to foster students to take images on class outings, then later host a photo exhibit on campus and use their vision for discussing a variety of ways that underdeveloped greenspaces on campus might be utilized to promote student physical and mental health [38]. Three of the articles described results of interventions on campus such as the creation of a sensory garden [40], therapeutic sensory garden [38], short greenspace interventions [9,37], and forest activities [14].

Mental health was mostly measured by surveys or questionnaires (21 studies, 65%) with validated scores. Ning et al. [35] used physiological indicators to measure restorative effects of exposure to natural campus areas (green and blue spaces): systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate recovery amounts [35]. Asim et al. [12] measured brainwaves with EEG to assess the benefits, and Souter-Brow et al. [24] measured salivary cortisol of students.

The main findings of all but one [19] of the studies pointed to a positive association between campus greenery and well-being of students, indicating the restorative role of greenness and water bodies on campus and/or around students’ residential areas. One of the 32 studies, undertaken in a natural desert environment, found a protective role of brownness (35% decrease in the incidence of depression), which may be explained by scarce green areas and familiarity with the desert environment and color [29]. In 12 of the studies, authors focused on green spaces’ settings and type of nature in association to mental well-being. High natural attributes [7], high biodiversity [19], botanical garden [22], vegetation novelty/uncertainty [2], expansive vistas [2], natural sound and acoustic ambiance [2,19], and blue space [32] indicated higher levels of restoration and lower negative moods. Closeness to buildings [4], window views overlooking greenery and sky, and also plants indoors [12] were associated with lower risk of depression and of severe anxiety. Quality of green space showed greater importance to mental health than use and quantity [35], while grayness of buildings was associated with an increase in depression [28].

Nine of the articles described results of interventions with students aiming to verify if natural environments could improve their mental health and well-being. Three of them used living experience in healing [40] and sensory gardens for quality of life [38], stress reduction, well-being and productivity [24]. Forest activities [14], trail and digital detox [9], and nature exposure were associated with positive moods [11] and to decreased test anxiety [26]. Brief nature exposure [35] indicated better heart indicators in water-front space, dense forest, and sparse forest.

Some mediating effect variables that explain how a greenspace affects beneficial outcomes were observed in a few studies: reduced road traffic noise, heat island, perceived air pollution, and isolation, as well as increased physical activity and social cohesion [5,31,33]. One of the studies highlighted those preventive strategies, dedicated mental health services, stable employment, and green infrastructure [27].

Most studies had cross-sectional design or were investigations on limited experiences. Evaluation of large-scale interventions to improve mental health, based on use and or improvements on green/blue spaces, with longitudinal methods, are still very limited to healing gardens and short periods of time.

Nevertheless, many students participated in these investigations. Adding students from all the samples came to a total of 27,955 individuals of both sexes and different academic backgrounds, in diverse areas around the world, from public and private universities or colleges. These high numbers make the findings quite robust.

We conclude that there is a large potential for use of university campuses in programs and as sites for students’ restoration and stress relief. Examples are therapeutic sensory gardens [24,37], forest activities [14], indoor plants and window views for plants and trees [12], green micro-breaks [9], walking and bicycling trails along the campus green areas, and benches in silent and shady gardens. Botanical gardens were also reported as missing to attract students’ experience for a restorative environment. Gulwadi [4] concluded that the space immediately next to buildings in which instruction takes place gains more significance when students spend longer hours in class, as that offers the closest access to greenspaces and enables social support [4]. Cultural aspects and geographical locations are of great importance according to the biophilia theory. Students’ perception of the wellness provided by greenness depends also on their experience, background, and taste. An important requirement is the sense of security of being outdoors and for this, care and maintenance of the campus green spaces are crucial. The costs of these items can be high, but are lower than those of expanding mental health services [41].

We highlight the relevance of students’ participation and engagement in activities for promoting student wellness and mental health, but also on planning land and nature use [38], on promoting campus sustainability [40], and natural area stewardship. Students’ perspective is particularly important in the face of this serious mental health crisis [41], as it may foster student trust, social cohesion [37], engagement, and learning that can be leveraged beyond a particular crisis to support longer-term sustainability goals.

University campuses might provide a salutogenic influence, as natural environments provide restoration to university students and are also a contributing factor to student retention because those who suffer mental health disorders are more likely to drop out, underperform academically, and are less likely to secure higher level employment [36].

Causes of psychological stress among university students are (a) academic: high academic demands, difficult daily targets, long study hours, different teaching methods with more responsibility to students, test anxiety, and extracurricular activities; (b) interpersonal: new relationships and friends, identity development, bad relationships with classmates, emotional distress, loss of self-identity, low self-esteem, prolonged period away from home, thus lower family support; (c) financial: pressures for paying tuition, living expenses such as food and academic material such as books, financial and professional concerns for the future, and family expectations; (d) cultural: racial and cultural differences, digital overload, long hours on campus for academic tasks and/or living on campus.

Nature contact can be a stress-reducing health promotion tool and a protective factor for mental health, based on the Stress Restoration Theory (SRT), by clearing random thoughts and lowering rumination; relaxation and calmness, and by restoring attention according to Attention Restoration Theory (ART). Pathways found in the studies include students’ perception; systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate; normalized average alpha brain waves measured with EEG; sensation of relief from stress; salivary cortisol; reduced scores on the anxiety and depression scales; increased mood, stress response and subjective well-being; and enhanced social life and social cohesion.

Thus, campus natural environments might restore psychological capabilities, improve attention, improve mood, and reduce stress and anxiety, with clinical evidence. In addition, programs and interventions on campus natural environments might build capabilities such as active life, adequate weight, social life, improved cognitive abilities, and personal growth.

Cox et al. [42] explain the four progressive levels of restoration: cleaning thoughts, recharging the capacity of directing attention, reducing internal noise, reflecting on life, its priorities, possibilities, actions, and objectives. Optimal levels of nature are not a silver bullet for the prevention and treatment of all mental health problems, nor can they act on the main causes of students’ stress, but they are an approach that can and should be applied for young adults in initial stages of depression and anxiety, and in conjunction with medical and social services, and increasing community-oriented actions.

Windhorst and William [10] claim for three actions: first to raise awareness of nature benefits among university students and staff; second, to make interventions on the campus to improve its attractiveness for community use and for students’ well-being; third, to develop nature-based therapies. This review article showed their importance and provided tools for these actions.

Gaps in the literature that need academic attention to deepen our understanding of the impact of green spaces on students’ well-being include: longitudinal studies, long-term interventions, psychology outcomes, and depression symptoms such as sadness, low interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-esteem, changes in sleep or appetite pattern, sensation of tiredness, and low concentration; anxiety symptoms as anxiety, fear, panic, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive behavior; suicide ideation and suicide attempts among students and how they could benefit from nature and nature activities.

Greenness in university campuses is even more important in LMIC countries, as a large proportion of the urban young adults live in neighborhoods crowded with small houses where vegetation is almost non-existent. We urge Latin American universities to turn eyes to this topic of investigation and practice.

We also call for the need of an interdisciplinary approach to the mental health issue among university students, with the integration of mental health services, landscape architecture, geography, campus administration, cultural activities, and physical activity practices.

5. Conclusions

Findings of all the studies indicated positive associations between campus greenery and the well-being of students. However, university campuses’ natural environments are largely under-utilized in programs and sites for students’ restoration and stress relief. As they usually have large green areas between buildings, some low-cost interventions and open-air programs could contribute to diminish the prevalence and severity of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, among university students, together with other initiatives. Investigations among university students are still limited but showed a large potential also for student engagement and building of social capital.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R., K.V.d.S.S. and S.L.O.; methodology, H.R., K.V.d.S.S. and S.L.O.; validation, H.R., K.V.d.S.S. and S.L.O.; formal analysis, H.R., K.V.d.S.S. and S.L.O.; investigation, H.R., K.V.d.S.S. and S.L.O.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R., K.V.d.S.S. and S.L.O.; writing—review and editing, H.R.; supervision, H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CNPq productivity grant 1A, to H.R.; post-doctoral scholarship from Fapesp to K.V.S.S. Post–doctoral scholarship from CAPES to S.L.O.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the program in Global Health and Sustainability for office support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pinto, G.; Buffa, E. Arquitetura e Educação: Campus Universitários Brasileiros; EdUFSCar: São Carlos, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.L.G. Educação, Saúde e Progresso: Discursos sobre os efeitos do ambiente no desenvolvimento da criança [1930–1980]. Estud. Av. 2023, 37, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A. Jan./Mar Ed: Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos; Centro Educacional Carneiro Ribeiro: Salvador, Brazil, 1959; pp. 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gulwadi, G.B.; Mishchenko, E.D.; Hallowell, G.; Alves, S.; Kennedy, M. The restorative potential of a university campus: Objective greenness and student perceptions in Turkey and the United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 187, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Markevych, I.; Hartig, T.; Tilov, B.; Arabadzhiev, Z.; Stoyanov, D.; Gatseva, P.; Dimitrova, D. Multiple pathways link urban green-and bluespace to mental health in young adults. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment: Field Trial Version, December 1996; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; You, D.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Bosch, C.; Lan, S. The relationship between self-rated naturalness of university green space and students’ restoration and health. Urban For. Urban Green 2018, 34, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J.A.; Gulwadi, G.B.; Alves, S.; Sequeira, S. The relationship between perceived greenness and perceived restorativeness of university campuses and student-reported quality of life. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibes, D.; Hirama, I.; Schuyler, C. Greenspace ecotherapy interventions: The stress-reduction potential of green micro-breaks integrating nature connection and mind-body skills. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windhorst, E.; Williams, A. Bleeding at the roots: Post-secondary student mental health and nature affiliation. Can. Geogr./Le Géogr. Can. 2016; 60, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, M.; Zhang, K.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Dong, J.; Liu, T.; Bailey, C.; McAnirlin, O.; Hanley, J.; Minson, C.T.; Mutel, R.L.; et al. Time in nature is associated with higher levels of positive mood: Evidence from the 2023 NatureDose™ student survey. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 90, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, F.; Chani, P.S.; Shree, V.; Rai, S. Restoring the mind: A neuropsychological investigation of university campus built environment aspects for student well-being. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srugo, S.A.; Groh, M.; Jiang, Y.; Morrison, H.I.; Hamilton, H.A.; Villeneuve, P.J. Assessing the impact of school-based greenness on mental health among adolescent students in Ontario, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.G.; Jeon, J.; Shin, W.S. The influence of forest activities in a university campus forest on student’s psychological effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernat, S.; Trykacz, K.; Skibiński, J. Landscape Perception and the Importance of Recreation Areas for Students during the Pandemic Time. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Mullenbach, L.E.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A.; Thomsen, J.; Metcalf, E.C.; Reigner, N.; Sharaievska, I.; McAnirlin, O.; D’Antonio, A.; et al. Greenspace and park use associated with less emotional distress among college students in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 112367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil—Ministério da Mulher, da Família e dos Direitos Humanos. Observatório Nacional da Família. Boletim fatos e números. In Saúde Mental; Ministério da Mulher, Família e dos Direitos Humanos: Brasília, Brazil, 2022; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, J.; Kim, H.J. The restorative effects of campus landscape biodiversity: Assessing visual and auditory perceptions among university students. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.L.; Lam, S.T.; McKeen, J.K.; Richardson, G.R.A.; Bosch, M.; Bardekjian, A.C. Urban trees and human health: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liprini, R.M.; Coetzee, N. The Relationship between Students’ Perceptions of the University of Pretoria On-Campus Green Spaces and Attention Restoration. 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2263/66125 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Malekinezhad, F.; Courtney, P.; Lamit, H.; Vigani, M. Investigating the mental health impacts of university campus green space through perceived sensory dimensions and the mediation effects of perceived restorativeness on restoration experience. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 578241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loder, A.K.F.; Schwerdtfeger, A.R.; Van Poppel, M.N.M. Perceived greenness at home and at university are independently associated with mental health. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souter-Brown, G.; Hinckson, E.; Duncan, S. Effects of a sensory garden on workplace wellbeing: A randomized control trial. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 207, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. A declaração PRISMA 2020: Diretriz atualizada para relatar revisões sistemáticas. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2023, 46, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Liu, C.; Xi, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P.; Liu, C.; Zhao, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, R.; Jia, X.; et al. Effects of greenness in university campuses on test anxiety among Chinese university students during COVID-19 lockdowns: A correlational and mediation analysis. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, T.K.; Rumbold, A.R.; Kedzior, S.G.E.; Kohler, M.; Moore, V.M. Mental health of young Australians during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the roles of employment precarity, screen time, and contact with nature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazif-Munoz, J.I.; Laurent, J.G.; Browning, M.; Spengler, J.; Álvarez, H.A. Green, brown, and gray: Associations between different measurements of land patterns and depression among nursing students in El Paso, Texas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loder, A.K.F.; Gspurning, J.; Paier, C.; Poppel, M.N.M. Objective and perceived neighborhood greenness of students differ in their agreement in home and study environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Hartig, T.; Tilov, B.; Atanasova, V.; Makakova, D.R.; Dimitrova, D.D. Residential greenspace is associated with mental health via intertwined capacity-building and capacity-restoring pathways. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Markevych, I.; Tilov, B.G.; Dimitrova, D.D. Residential greenspace might modify the effect of road traffic noise exposure on general mental health in students. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M. Residential green and blue space associated with better mental health: A pilot follow-up study in university students. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2018, 69, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.; Hartig, T.; Markevych, I.; Tilov, B.; Dimitrova, D. Urban residential greenspace and mental health in youth: Different approaches to testing multiple pathways yield different conclusions. Environ. Res. 2018, 160, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemyre, A.; Chrisinger, B.W.; Palmer-Cooper, E.; Messina, J.P. Neighborhood greenspaces and mental wellbeing among university students in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey under lockdown. Cities Health 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, W.; Yin, J.; Chen, Q.; Sun, X. Effects of brief exposure to campus environment on students’ physiological and psychological health. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1051864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, F. Between the Library and Lectures: How Can Nature Be Integrated Into University Infrastructure to Improve Students’ Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 865422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepansky, K.; Delbert, T.; Bucey, J.C. Active student engagement within a university’s therapeutic sensory garden green space: Pilot study of utilization and student perceived quality of life. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, R.F.; Seitz, C.M.; Gosling, M.; Craig, H. Using photovoice to foster a student vision for natural spaces on a college campus in the Pacific Northwest United States. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020, 30, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasny, M.E.; Delia, J. Campus sustainability and natural area stewardship: Student involvement in adaptive comanagement. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 27. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269610 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Lau, S.S.Y.; Yang, F. Introducing healing gardens into a compact university campus: Design natural space to create healthy and sustainable campuses. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matasov, V.; Grigoreva, V.; Makhinya, K.; Kozyreva, M.; Romzaikina, O.; Maximova, O.; Pakina, A.; Filyushkina, A.; Vasenev, V. Cost–Benefit Assessment for Maintenance of Urban Green Infrastructure at the University Campus in Moscow: Application of GreenSpaces and TreeTalker Technologies to Regulating Ecosystem Services. In Springer Geography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Part F1411; pp. 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Plummer, K.E.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of Neighborhood nature: The benefits for mental health of living with nature. BioScience 2017, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).