Abstract

In recent years, physical activity assessment has increasingly relied on wearable monitors to provide measures for surveillance, intervention, and epidemiological research. This present systematic review aimed to examine the current research about the utilization of wearable technology in the evaluation in physical activities of preschool- and school-age children. A database search (Web of Science, PubMed and Scopus) for original research articles was performed. A total of twenty-one articles met the inclusion criteria, and the Cochrane risk of bias tool was used. Wearable technology can actually be a very important instrument/tool to detect the movements and monitor the physical activity of children and adolescents. The results revealed that there are a few studies on the influence of these technologies on physical activity in schools, and most of them are descriptive. In line with previous research, the wearable devices can be used as a motivational tool to improve PA behaviors and in the evaluation of PA interventions. However, the different reliability levels of the different devices used in the studies can compromise the analysis and understanding of the results.

1. Introduction

In youth populations, effective health interventions contribute significantly to preventing obesity and metabolic diseases throughout life, as well as to the creation of an intention to practice such activities for life [1,2,3,4]. According to Sallis and Owen [5], it seems that children and adolescents are adopting the sedentary habits of adults, as well as their way of looking at physical exercise, namely, the usual reasons for not doing it. As adults adopt less active lifestyles and serve as role models for young people, it is natural for this to happen [6]. This situation calls attention to the need to first change the habits of adults, so that it is easier to intervene with younger people [6,7]. One of the factors that contributes to the sedentary lifestyle of young people is the reduction of physical efforts while they are commuting to school and in hobbies, namely watching television, playing electronic and computer games, socializing while sitting, etc. During their daily lives, they do not perform physical activity in sufficient amounts and intensities to promote beneficial effects on their health, namely in the prevention of risk factors [5]. Regardless of age, physical activity (PA) can be considered one of the most useful and successful strategies to promote health. PA is usually oriented towards daily habits that promote a healthy lifestyle or even to achieve optimal performance. For this reason, physical exercise improves the functioning of all of the systems of the human body, mainly the cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine and digestive systems, strengthening the musculoskeletal system and increasing certain levels of flexibility [8].

To achieve such goals, PA assessment has been considered as a key factor to promote, monitor and also encourage practice among youths. PA assessment is increasingly dependent on wearable devices, as they are the excellent means to provide measures for evaluate surveillance, intervention and epidemiological research [9]. In recent years, there has been a sharp increase in the number and type of equipment available on the market to assess PA [9,10,11].

Wearable technologies are devices with sensors, screen, processor, memory and software with algorithms to filter, interpret, organize and store the raw data that is collected, which can connect to the internet and present the data to the user in real time or as a retrospective report [12]. In other studies, wearable technologies are defined as devices that can monitor the physical activities (steps, calories, etc.) [13,14], physiological data (heart rate, body temperature, etc.) [15,16,17], data [18,19,20], gesture detection [21,22] and emotion recognition [23] of the user 24/7 and collect and store and transmit these data, while helping the users to perform many other useful micro-tasks, such as checking incoming text messages and displaying urgent information [24,25,26].

Wearables serve as knowledge and risk management tools, becoming valuable business and sports management information technology tools. If the data they collect are properly read and strategic actions are drawn from them, their impact on sports performance could grow and become remarkable [27]. According to Çiçek [28], there are three main categories of wearable technology. These categories are health-related wearable technologies, textile-based wearable technologies, and consumer electronics wearable technologies. The benefits of wearable technologies are attested by the fact that they have been used for a long time in various disciplines and for different purposes, such as medical sciences, fashion, and sports [29]. In fact, wearables are very popular these days and have great potential due to the fact that they can improve people’s daily lives, and it is accepted that the application of sensors and other electronic devices on the body can revolutionize the human experience in several areas [29].

In addition, these devices have some advantages, one of which is that they can be easily used in any field environment (increasing ecological validity) so that coaches/teachers can obtain feedback (positive or negative) on the variables measured in real time and report the performance level of players/athletes/students, whether during training, a game or a class [30]. The data obtained through these devices/sensors can be used for a variety of purposes based on the objectives outlined at the beginning of each study, such as: (i) measuring, controlling and increasing the physical performance of players/athletes/students; (ii) preventing possible injuries caused by excessive overload (in training or game); (iii) preventing injured players/athletes returning prematurely to training/a game; (iv) monitoring and predicting the performance evolution of younger players/athletes. In addition, these devices/sensors are programmed/manufactured to operate in any sports environment (outdoor or indoor venues) as they are small, light, wireless and easy to transport [30]. Finally, some devices/sensors have additional features, such as being waterproof or having the ability to store data at low temperatures [31,32,33].

Research on the use of wearable devices in the school context of physical education has shown that this type of application brings advantages in terms of motivation, knowledge of the results, evaluation and improvement of the student’s autonomy [34,35,36,37,38]. Schwartz and Baca [39] point out that most of these AP applications are based on behavioral theory and use gamification elements to achieve success with personal goals and specific feedback. Therefore, Lee and Gao [40] recommend the use of apps to particularly facilitate students’ group activities, as well as understanding the impact of such practices on the results.

However, little is still known about the use of these wearable technologies in schools. Therefore, our purpose was to examine the current research about the use of wearable technology in the evaluation in physical activities of preschool- and school-age children and to provide teachers/researchers with perspectives for future lines of research.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines [41].

2.1. Search Strategy

The search was performed across the entire literature between 2000 and August 2022 in three electronic databases: Web of Science, PubMed and Scopus. The Boolean search method was used, which limited the search results with operators including AND/OR only to studies that contained key terms relevant to the scope of this review. The search terms were identified: “children” OR “adolescents” AND “wearable” OR “portable sensors” OR “sensors” OR “accelerometers” AND “physical activity” OR “physical exercise” OR “endurance” OR “aerobic” OR “strength training” OR “resistance training” AND “monitoring” AND “school” OR “physical education”. Supplementary Materials Table S1 reports the search strategies used in the three databases.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The included studies focused on wearable technologies in the preschool and school context in youth with physical activity-related outcomes. Studies published in English in a peer-reviewed journal were included, evaluating physical activity in all school settings (playtime, physical education classes and school sports) in healthy, young people. Review articles (i.e., qualitative reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses), theses, dissertations, congress abstracts and proceedings were not considered. All of the information collected from the studies included in the systematic review were based on the research design, objective, subjects, procedures and findings.

2.3. Study Selection

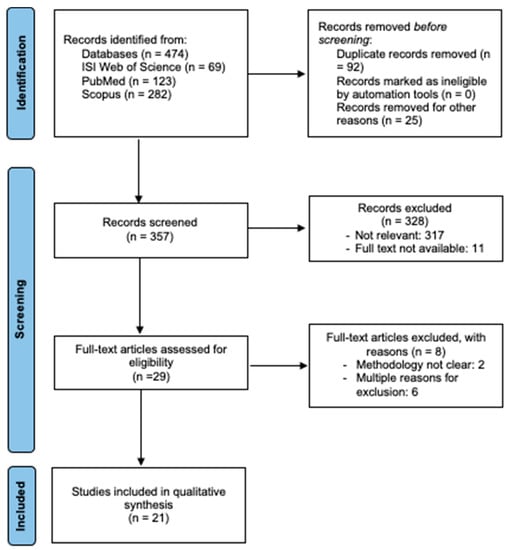

The systematic search identified 474 records. After an initial screening, 29 studies were considered to be eligible for evaluation, and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded (e.g., inconclusive information about study procedures, the intervention method, etc.). In the end, a total of 21 studies were included in the final qualitative analysis. The earliest of these studies was published in 2001 [42], and the most recently published study was from 2020 [43]. Figure 1 shows the article selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The included articles obtained information on sample size, age, wearable strategies, measurements, main results and conclusions. The data extraction process was performed by two authors (A.C.S. and B.T.), and inconsistent data were resolved by the third author (S.N.F.).

2.5. Data Analysis

Assessment Risk of Bias

To assess the risk of bias, the Cochrane Reviews method was used [44]. Two authors (A.C.S. and S.N.F.) assessed the risk of bias of each study against key criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, blinding participants and personnel, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias, and when there was no consensus between the two authors on which classification to assign to a given criterion, a third author evaluated the study (B.T.). In classifying the studies, the following terms were used: low risk, high risk or unclear risk. The Review Manager software (RevMan, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) version 5.4 was used to build the risk of bias graphs.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies Reviewed

Table 1 presents all of the information about the studies included in the review. The studies included sample sizes from 19 to 1908 subjects (boys and girls) aged from 3 to 19 years old. The sample came from thirteen different countries: five studies in the USA [45,46,47,48,49], four studies in the Czech Republic [43,50,51,52], two studies each in Australia [53,54], Poland [50,55] and England [56,57], and one study each in Estonia [58], Mexico [49], Portugal [59], Norway [60], New Zealand [61], France [42], Sweden [62] and the Netherlands [63].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the review.

Of the 21 studies reviewed on physical activity in the preschool and school context, 71.5% (n = 15) developed an intervention for distance performance, 9.5% (n = 2) applied an intervention for the number of steps and 19% (n = 4) focused on both of the interventions mentioned above. Regarding the wearable technology used in the studies, 80.1% (n = 17) of the studies focused on accelerometers, while 24% (n = 6) were based on pedometers. In most of the studies, the participants wore the device on their hip or near their center of gravity (80%) (n = 19), and only in 10% (n = 2) of the participants wore the device on their arm/wrist.

Table 2 shows the main characteristics of the devices used in the studies that were included in this review. Thirteen different devices were registered for the development of 21 studies with different methods of registration and data analysis (for detailed information, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the devices included in the review.

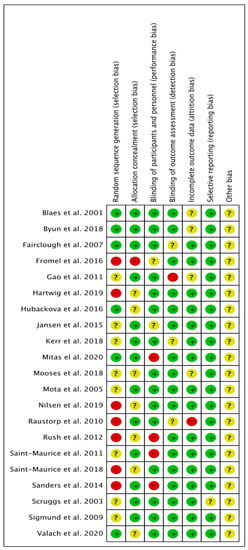

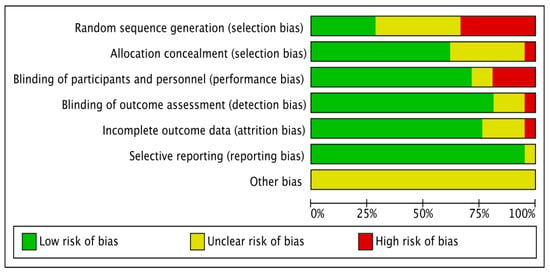

3.2. Risk of Bias in the Included Articles

About 30.0% of the studies were randomized, and 70.0% used cross-sectional designs. The generated allocation sequence item identified the least often applied item, but it does not provide sufficient detail to assess whether it could produce comparable groups. Most investigations implemented a blinded design; however, a few studies performed a cross-group comparison. About 60.0% of the studies revealed their concealed allocation, which had a systematic bias of therapeutic effectiveness, and 90.0% of the studies reported a low risk of bias in the incomplete outcome data (attrition bias domain), which revealed transparency in the methodology used. Well-reported losses and exclusions were reported in the studies [44] (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study [42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Figure 3.

Risk of bias items are presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.3. Physical Activity in Children’s Using Pedometers

In the articles included in this review, the only ones that used pedometers exclusively were the studies by Mitas et al. [51] and Scruggs et al. [47] (Table 3). The study by Mitas et al. [51] found that boys spent more time performing vigorous physical activity (VPA) and moderate physical activity (MPA) than girls did. However, in the study by Scruggs et al. [47], it was observed that first grade girls (6 to 10 years) spent more time performing moderate–vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and VPA than boys did. In the second year, it was found that girls spent more time performing MVPA than boys did, while the latter group spent more time performing VPA, concerning the validation sample group. In the cross-validation group, the first grade boys (6 to 10 years) spent more time performing MVPA and VPA, while second grade boys (10 to 14 years) spent the same amount of time doing this as first grade boys and girls did (6 to 10 years).

Table 3.

Analysis of the main results of the studies included in the review.

Therefore, in line with the results, boys generally are more predisposed to practicing more PA, whether it is moderate or vigorous, than girls are during their daily routines at school.

3.4. Physical Activity in Children’s Using Accelerometers

In general, the studies that included accelerometer devices revealed that most of the children in the analyses spent most of their time performing MVPA [45,46,53,55,56,58,59,63]. However, in opposition, there were two studies [50,60] that revealed that children tend to spent most of the time performing light physical activity (LPA) (Table 3).

However, five studies were included in the review with reports of the significant effects on the PA performed [42,43,48,49,57]. For example, in the study by Blaes et al. [42], significant differences were observed between the PS vs. JHS groups for LPA (p < 0.05), for MPA, VPA and very high physical activity (VHPA) levels in the PS vs. Ps and PS vs. JHS groups (p < 0.05) and for the PS vs. JHS group in the moderate–very high physical activity (MVHPA) (p < 0.05).

The comparison between normal and obese children in the study by Gao et al. [49] revealed, as expected, that normal children spent more time performing physical activity (percentage of MVPA) than obese children do (p = 0.029, η2 = 0.03) However, it was found that obese children spent more time being sedentary than normal children do (p = 0.002, η2 = 0.06).

The comparison between boys and girls revealed that, in general, boys are more predisposed to and practice more PA at a high intensity than girls do [43,48,57]. Results of Kerr et al. [57] reported that girls spend more time performing LPA than boys do (p < 0.01, d = 1.21). In contrast, boys spend more time performing VPA (p < 0.01, d = −1.04) and VHPA (p < 0.01, d = −0.82), respectively, than girls do. In the study by Saint-Maurice et al. [48], boys were significantly more active than girls were in different schools (p < 0.001). Finally, in the study by Valach et al. [43], boys revealed significantly high BP levels during recess while performing LPA (p < 0.01, η2 = 0.032) and VPA (p < 0.01, η2 = 0.061) and VPA at school (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.050) than girls did.

3.5. Physical Activity in Children’s Pedometers vs. Accelerometers

Only four studies [52,54,61,62] used pedometers and accelerometers simultaneously in their analyses (Table 3). In the study by Hartwig et al. [54], it was observed that the physical activity assessment was more effective for pedometers in the three experimental groups than it was for accelerometers. Additionally, in line with previous results, boys tend to present higher values of PA than girls did.

In the study by Sigmund et al. [52], there were significant effects caused by accelerometers (p < 0.001, d = 1.5646) and pedometers (p < 0.001, d = 1.3231) on general physical activity. Furthermore, both devices found significant effects (p < 0.001) when the authors were comparing the differences between the boys and girls. In the study by Rush et al. [61], boys and girls have higher values for physical inactivity than they do for physical activity throughout a school day. Finally, in the study by Raustorp et al. [62], it was observed that boys spent more time performing MVPA than girls did during a physical education class.

4. Discussion

This review aimed to examine the current research about the use of wearable technology in the evaluation in physical activities of preschool- and school-age children and to provide teachers/researchers with perspectives for future research. Studies on this topic are relatively new, with a higher incidence in recent years. However, only twenty-one studies have been observed to assess and understand PA in schools using wearable technology in last 22 years. In general, the studies were descriptive and compared the practice of boys and girls or even measured the reliability of the devices. Most of the studies used accelerometers, and only four of them used pedometers. However, thirteen different devices were registered for the development of the studies with different methods of registration and data analysis, creating difficulties to further understand the tendencies of results and define recommendations for the future. In general, and in line with previous research, wearable technology can be used as a motivational tool to improve PA behaviors and in the evaluation of PA interventions [40,41].

Many studies have evaluated the accuracy of various pedometers. Pedometers are usually simple and inexpensive devices, giving real-time feedback in terms of measuring the number of steps taken on a daily basis [42,43,44,45]. The pedometers revealed low accuracy at slower speeds, particularly the ones that used a spring-suspended horizontal lever arm mechanism [43,45]. In addition, pedometers may have low accuracy when they are attached to other parts of the body [46] or when they are attached to certain clothing items (e.g., when wearing a dress) [47]. These issues are fundamental for gaining an understanding about the obtained results and their application to the practice and for the development of more adjusted programs of intervention. However, despite its importance to improving the user acceptance of pedometers, to date, a small amount of research had been developed to explore the reliability of the pedometers and to validate their use in different contexts and types of activities [64].

In addition to pedometers, the use of accelerometers has also increased in recent years when one has been assessing PA [48]. Triaxial accelerometers are motion devices that measure acceleration in three planes during body motions [49]. Therefore, they were developed to measure PA levels and provide information that motivates individuals to exercise. Compared to pedometers, accelerometers are the devices that are most often used by researchers and in clinical settings because they have more variables that can be analyzed. For example, while pedometers only assess the distance covered by the number of steps, accelerometers allow us to assess the frequency, duration and intensity of PA [49]. Both of the devices showed good validity in terms of activity count (number of steps) and energy expenditure in different populations (healthy and chronically ill populations) [50,51].

The use of wearable technology in a preschool and school contexts has been studied since the beginning of the 1980s. However, researchers have only recently focused on realizing PA’s preponderance in children, whether they are in the classroom or the playground. All of the studies implemented interventions based on wearable technologies (using accelerometers and pedometers) with a period between two days and ten months in terms of PA performed in PE classes or during recess, and the authors found positive effects of the intervention on the different intensities used by children during PA. The included studies revealed that boys spend more time performing PA than girls do. Another essential result to highlight is that, in general, they (boys and girls) spend more time performing MVPA compared to LPA and VPA.

PA is a very important and essential tool for the adoption of healthy habits in children, but also for their future life, as several studies have shown a positive association between PA and gender [52,53], whether in the form of leisure [54,55] or in the form of physical activity in education/recreation classes [56,57]. On the other hand, there are some studies that have not reported a positive relationship between PA and gender [58,59,60,61].

The overall differences between PE days and non-PE days indicate that an additional 19 min of high-intensity physical activity (vigorous physical activity and above) during the PE day is critical, as vigorous physical activity (or greater) is a stronger predictor of cardiorespiratory fitness [65,66,67,68], body fat [69,70,71] and vascular function [72] in children compared with that of moderate–intensity physical activity. Thus, the daily use of pedometers, but particularly accelerometers, is highly recommended in schools to help PE teachers to classify the level of the students’ activity and the adequate application of training loads to different groups. For example, while the practice of team sports should be encouraged as an efficient way to promote higher levels of PA in some students, others could be encouraged to practice different activities with a low PA impact, but to develop coordination or other kind of capacities. The use of these devices to promote the gamification of the practice of PA should be encouraged and promoted using dedicated apps for mobile phones or tablets. A lot of systematic reviews have been published in recent years related to the subject of this review, where the authors [73] found that the PA level is also influenced by the students’ friends’ PA level, demonstrating that team sports and community life can increase the PA level, promoting the reduction of the obesity-related problems. Another study also verified that using Fitbit devices may benefit increasing the level of PA during recreational activities [74]. The mobile applications for this subject are more related to the measurements of weight, height, age, gender, goals, and calories needed for calculations, diet diaries and food databases including calories, calories burned and calorie intake [75].

This systematic review presents some limitations that must be recognized: (i) most of the articles included were based solely and exclusively on pedometers and accelerometers for the analysis of the children’s PA in preschool and school contexts; (ii) only two articles included in this review focused on energy expenditure (kcal) during PA performed at school and (iii) the risk of bias of the included studies reported that a third of the studies did not describe how the distribution of the groups was carried out.

Future research on PA time trends in schools could use a similar strategy using a subjective assessment of PA with the subsequent objective monitoring of PA. It also seems appropriate to use the newly verified Youth Activity Profile [76] and to monitor, at least weekly, PA using simple wearable devices (wristbands) that are suitable for longitudinal use. Finally, strategies that promote participant adherence to the monitoring protocol should be emphasized [77]. Therefore, future investigations should not focus only on general data, but they should also seek to discriminate the contexts or activities associated with the practice of physical activity in order to better understand what distinguishes boys and girls.

5. Conclusions

Wearable technology can be an essential instrument/tool to detect movements and monitor the physical activity of children and adolescents. There are known benefits of using these instruments to measure the levels of physical activity and the daily energetic cost (accelerometers: ActiTrainer, ActiGraph GT3X and Fitbit Zip and Fitbit Flex; pedometers: Yamax Digiwalker SW200 a Yamax Digiwalker SW700). In terms of the reliability and validity of pedometers and accelerometers and based on currently available evidence, we conclude that the ActiGraph accelerometers (in particular, the GT3X versions), Actical and ActiTrainer, have the best measurement properties to assess common movement-related outcomes (e.g., example, MVPA and TPA) for school-based activities for preschool- and school-aged children, and they should be the tools of choice where resources permit it is and where it is logistically possible. On the other hand, Fitbit Zip and Fitbit Flex also showed very promising results; however, these were based on a very limited sample of studies. On the other hand, we found that the Yamax Digi-Walker (SW-200) and Yamax Digi-Walker (SW-700 and 701) pedometers have the best measurement characteristics related to movement (e.g., example, MVPA and VPA). However, there are only a few studies on the influence of these technologies on physical activity in schools. Therefore, there was a large number of different devices and methods considered in the studies, which did not allow us to further understand the best practices or to define some recommendations for the future. In line with that, more studies with larger samples of the population involved and with more methods and procedures are required to really understand the effect of such programs on physical activity (e.g., the number of calories burned and the number of steps performed), as well as health. To improve upon the descriptive studies that only registered and compared the physical activity in school, future research should be focused on the use of such devices in specific intervention programs that evaluate different groups using the same devices and variables, which later, could be used to intervene by improving young people’s health and instilling healthy lifestyles.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/10/5344/s1, Table S1: Search strategies used for each database.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design, A.C.S. and B.T.; acquisition of data, A.C.S.; analysis or interpretation of data, A.C.S. and B.T.; software, A.C.S.; validation, A.C.S., S.N.F. and B.T.; formal analysis, B.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.S.; writing—review and editing, S.N.F. and B.T.; supervision, A.C.S.; final approval: A.C.S., S.N.F. and B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by national funding through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under project UID/DTP/04045/2019. This work is also funded by FCT/MEC through national funds and co-funded by FEDER—PT2020 partnership agreement under the project UIDB/50008/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldfield, G.S.; Harvey, A.; Grattan, K.; Adamo, K.B. Physical Activity Promotion in the Preschool Years: A Critical Period to Intervene. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 1326–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichert, F.F.; Baptista Menezes, A.M.; Wells, J.C.K.; Carvalho Dumith, S.; Hallal, P.C. Physical Activity as a Predictor of Adolescent Body Fatness. Sport. Med. 2009, 39, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Suarez, C.; Worley, A.; Grimmer-Somers, K.; Dones, V. School-Based Interventions on Childhood Obesity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, N.; Rohde, J.; Heitmann, B. The Healthy Start Project: A Randomized, Controlled Intervention to Prevent Overweight among Normal Weight, Preschool Children at High Risk of Future Overweight. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.; Owen, N. Physical Activity and Behavioral Medicine, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 9781452233765. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, N.; Welsman, J. Young People and Physical Activity; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, A. Actividade Física e Saúde. A Perspectiva Pedagógica. In O Papel da Educação Física na Promoção de Estilos de Vida Saudáveis; Rocha, L., Ed.; Faculty of Sport of the University of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 1998; pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa; Urrea, A. Influencia Del Deporte y La Actividad Física En El Estado de Salud Físico y Mental: Una Revisión Bibliográfica. Rev. Katharsis 2018, 25, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, S.A.; Adamo, K.B.; Hamel, M.; Hardt, J.; Connor Gorber, S.; Tremblay, M. A Comparison of Direct versus Self-Report Measures for Assessing Physical Activity in Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Bassett, D.R. The Technology of Accelerometry-Based Activity Monitors: Current and Future. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2005, 37, S490–S500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Hsu, Y.-L. A Review of Accelerometry-Based Wearable Motion Detectors for Physical Activity Monitoring. Sensors 2010, 10, 7772–7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade Shantz, J.A.; Veillette, C.J.H. The Application of Wearable Technology in Surgery: Ensuring the Positive Impact of the Wearable Revolution on Surgical Patients. Front. Surg. 2014, 1, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, C.; Rooksby, J.; Gray, C.M. Evaluating the Impact of Physical Activity Apps and Wearables: Interdisciplinary Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickwood, K.-J.; Watson, G.; O’Brien, J.; Williams, A.D. Consumer-Based Wearable Activity Trackers Increase Physical Activity Participation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, D.R.; Rowbottom, J.R.; Drummond, C.; Voos, J.E.; Craker, J. A Review of Wearable Technology: Moving beyond the Hype: From Need through Sensor Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2016 8th Cairo International Biomedical Engineering Conference (CIBEC), Cairo, Egypt, 15–17 December 2016; pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, J.; Jenkins, J.; Meservy, T.; Steffen, J.; Payne, K. Using Wearable Devices for Non-Invasive, Inexpensive Physiological Data Collection. 2017. Available online: https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/6c041d0a-0cb8-41cf-a60a-0bdffd526ba9/content (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Leu, F.; Ko, C.; You, I.; Choo, K.-K.R.; Ho, C.-L. A Smartphone-Based Wearable Sensors for Monitoring Real-Time Physiological Data. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 65, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.C.; Ataíde, V.N.; Silva Chagas, C.L.; Angnes, L.; Tomazelli Coltro, W.K.; Longo Cesar Paixão, T.R.; Reis de Araujo, W. Wearable Electrochemical Sensors for Forensic and Clinical Applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 119, 115622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymourian, H.; Parrilla, M.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Montiel, N.F.; Barfidokht, A.; Van Echelpoel, R.; De Wael, K.; Wang, J. Wearable Electrochemical Sensors for the Monitoring and Screening of Drugs. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2679–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, K.; Wang, J. Electrochemical Sensors: From the Bench to the Skin. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 344, 130178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aurizio, N.; Baldi, T.L.; Paolocci, G.; Prattichizzo, D. Preventing Undesired Face-Touches With Wearable Devices and Haptic Feedback. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 139033–139043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marullo, S.; Baldi, T.L.; Paolocci, G.; D’Aurizio, N.; Prattichizzo, D. No Face-Touch: Exploiting Wearable Devices and Machine Learning for Gesture Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 4187–4193. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Suryadevara, N. Development and Progress in Sensors and Technologies for Human Emotion Recognition. Sensors 2021, 21, 5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosenia, A.; Sur-Kolay, S.; Raghunathan, A.; Jha, N.K. Wearable Medical Sensor-Based System Design: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Multi-Scale Comput. Syst. 2017, 3, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M.A.; Michaelis, J.R.; McConnell, D.S.; Smither, J.A. The Role of Individual Differences on Perceptions of Wearable Fitness Device Trust, Usability, and Motivational Impact. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 70, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.V.; Hettinger, L.J.; Huang, Y.-H.; Jeffries, S.; Lesch, M.F.; Simmons, L.A.; Verma, S.K.; Willetts, J.L. Employee Acceptance of Wearable Technology in the Workplace. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 78, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teló, F.G.; de Oliveira, B.B.; Vita, J.B.; Ferreira, R.M.Z. Análise de Custo-Benefício, Tecnologias Vestíveis e Monitoramento Biométrico nos Esportes Norte-Americanos: Aspectos Jurídicos e Econômicos. Econ. Anal. Law Rev. 2021, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiçek, M. Wearable Technologies and Its Future Applications. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Data Commun. 2015, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, K.; Fuks, H. Beauty Technology; Human–Computer Interaction Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-15761-0. [Google Scholar]

- Adesida, Y.; Papi, E.; McGregor, A.H. Exploring the Role of Wearable Technology in Sport Kinematics and Kinetics: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bächlin, M.; Tröster, G. Swimming Performance and Technique Evaluation with Wearable Acceleration Sensors. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2012, 8, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, A.; Edelmann-Nusser, J. Biomechanical Analysis in Freestyle Snowboarding: Application of a Full-Body Inertial Measurement System and a Bilateral Insole Measurement System. Sport. Technol. 2009, 2, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.M.; Kerr, G.; Sullivan, J.P. A Critical Review of Consumer Wearables, Mobile Applications, and Equipment for Providing Biofeedback, Monitoring Stress, and Sleep in Physically Active Populations. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, C.; Goodyear, V.A. The Motivational Impact of Wearable Healthy Lifestyle Technologies: A Self-Determination Perspective on Fitbits With Adolescents. Am. J. Health Educ. 2017, 48, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenk, S.; Reifegerste, D.; Renatus, R. Gender Differences in Gratifications from Fitness App Use and Implications for Health Interventions. Mob. Media Commun. 2017, 5, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Rodenbeck, M.; Clegg, B. Apps for Physical Education: Teacher Tested, Kid Approved! Strategies 2014, 27, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Ramírez, L.; Notario, R.O.; Ávalos-Ramos, M.A. The Relevance of Mobile Applications in the Learning of Physical Education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Pino, I.; López-Castedo, A.; Martínez-Patiño, M.J.; Valverde-Esteve, T.; Domínguez-Alonso, J. Gender Differences in Motivation and Barriers for The Practice of Physical Exercise in Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, B.; Baca, A. Wearables and Apps—Modern Diagnostic Frameworks for Health Promotion through Sport. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 2016, 2016, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Gao, Z. Effects of the IPad and Mobile Application-Integrated Physical Education on Children’s Physical Activity and Psychosocial Beliefs. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaes, A.; Baquet, G.; Van Praagh, E.; Berthoin, S. Physical Activity Patterns in French Youth-From Childhood to Adolescence-Monitored with High-Frequency Accelerometry. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valach, P.; Vašíčková, J.; Frömel, K.; Jakubec, L.; Chmelík, F.; Svozil, Z. Is Academic Achievement Reflected in the Level of Physical Activity among Adolescents? J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, W.; Lau, E.; Brusseau, T. Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Wearable Technology-Based Physical Activity Intervention in Preschoolers: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Maurice, P.; Bai, Y.; Vazou, S.; Welk, G. Youth Physical Activity Patterns During School and Out-of-School Time. Children 2018, 5, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, P.W.; Beveridge, S.K.; Eisenman, P.A.; Watson, D.L.; Shultz, B.B.; Ransdell, L.B. Quantifying Physical Activity via Pedometry in Elementary Physical Education. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2003, 35, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Welk, G.J.; Silva, P.; Siahpush, M.; Huberty, J. Assessing Children’s Physical Activity Behaviors at Recess: A Multi-Method Approach. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2011, 23, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Oh, H.; Sheng, H. Middle School Students’ Body Mass Index and Physical Activity Levels in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frömel, K.; Kudlacek, M.; Groffik, D.; Chmelik, F.; Jakubec, L. Differences in the Intensity of Physical Activity during School Days and Weekends in Polish and Czech Boys and Girls. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2016, 23, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitáš, J.; Frömel, K.; Valach, P.; Suchomel, A.; Vorlíček, M.; Groffik, D. Secular Trends in the Achievement of Physical Activity Guidelines: Indicator of Sustainability of Healthy Lifestyle in Czech Adolescents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmund, E.; Sigmundová, D.; Ansari, W. El Changes in Physical Activity in Pre-Schoolers and First-Grade Children: Longitudinal Study in the Czech Republic. Child. Care. Health Dev. 2009, 35, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, T.; Cliff, D.P.; Lonsdale, C. Measuring Adolescent Boys’ Physical Activity: Bout Length and the Influence of Accelerometer Epoch Length. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, T.B.; del Pozo-Cruz, B.; White, R.L.; Sanders, T.; Kirwan, M.; Parker, P.D.; Vasconcellos, D.; Lee, J.; Owen, K.B.; Antczak, D.; et al. A Monitoring System to Provide Feedback on Student Physical Activity during Physical Education Lessons. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubáčková, R.; Groffik, D.; Skrzypnik, L.; Frömel, K. Physical Activity and Inactivity in Primary and Secondary School Boys’ and Girls’ Daily Program. Acta Gymnica 2016, 46, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, S.J.; Butcher, Z.H.; Stratton, G. Whole-Day and Segmented-Day Physical Activity Variability of Northwest England School Children. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, C.; Smith, L.; Charman, S.; Harvey, S.; Savory, L.; Fairclough, S.; Govus, A. Physical Education Contributes to Total Physical Activity Levels and Predominantly in Higher Intensity Physical Activity Categories. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 24, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooses, K.; Oja, M.; Reisberg, S.; Vilo, J.; Kull, M. Validating Fitbit Zip for Monitoring Physical Activity of Children in School: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, J.; Silva, P.; Santos, M.P.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Oliveira, J.; Duarte, J.A. Physical Activity and School Recess Time: Differences between the Sexes and the Relationship between Children’s Playground Physical Activity and Habitual Physical Activity. J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, A.K.O.; Anderssen, S.A.; Resaland, G.K.; Johannessen, K.; Ylvisaaker, E.; Aadland, E. Boys, Older Children, and Highly Active Children Benefit Most from the Preschool Arena Regarding Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity: A Cross-Sectional Study of Norwegian Preschoolers. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 14, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, E.; Coppinger, T.; Obolonkin, V.; Hinckson, E.; McGrath, L.; McLennan, S.; Graham, D. Use of Pedometers to Identify Less Active Children and Time Spent in Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity in the School Setting. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raustorp, A.; Boldemann, C.; Johansson, M.; Mårtensson, F. Objectively Measured Physical Activty Level a during a Physical Education Class: A Pilot Study with Swedish Youth. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2010, 22, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Toussaint, H.M.; van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E.A.L.M. Effectiveness of the PLAYgrounds Programme on PA Levels during Recess in 6-Year-Old to 12-Year-Old Children. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, E.D.; Hartmann, A.; Uebelhart, D.; Murer, K.; Zijlstra, W. Wearable Systems for Monitoring Mobility-Related Activities in Older People: A Systematic Review. Clin. Rehabil. 2008, 22, 878–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, L.; Silva, P.; Silva, G.; Santos, M.P.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Mota, J. Intensity of Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and Body Mass Index in Youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencker, M.; Thorsson, O.; Karlsson, M.K.; Lindén, C.; Wollmer, P.; Andersen, L.B. Daily Physical Activity Related to Aerobic Fitness and Body Fat in an Urban Sample of Children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2008, 18, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, S.J.; Trenell, M.I.; Plötz, T.; Savory, L.A.; Bailey, D.P.; Kerr, C.J. Cardiorespiratory Fitness Is Associated with Hard and Light Intensity Physical Activity but Not Time Spent Sedentary in 10–14 Year Old Schoolchildren: The HAPPY Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutin, B.; Yin, Z.; Humphries, M.C.; Barbeau, P. Relations of Moderate and Vigorous Physical Activity to Fitness and Fatness in Adolescents. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.A.; Davies, P.S.W. Habitual Physical Activity and Physical Activity Intensity: Their Relation to Body Composition in 5.0–10.5-y-Old Children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, T.; Stratton, G. Influence of Intensity of Physical Activity on Adiposity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in 5–18 Year Olds. Sport. Med. 2011, 41, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J.R.; Rizzo, N.S.; Hurtig-Wennlöf, A.; Ortega, F.B.; Wàrnberg, J.; Sjöström, M. Relations of Total Physical Activity and Intensity to Fitness and Fatness in Children: The European Youth Heart Study1–3. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, N.D.; Stratton, G.; Tinken, T.M.; McWhannell, N.; Ridgers, N.D.; Graves, L.E.F.; George, K.; Cable, N.T.; Green, D.J. Relationships between Measures of Fitness, Physical Activity, Body Composition and Vascular Function in Children. Atherosclerosis 2009, 204, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, C.; Santos, F.; Martins, F.; Lopes, H.; Gouveia, B.; Gonçalves, F.; Campos, P.; Marques, A.; Ihle, A.; Gonçalves, T.; et al. Digital Health in Schools: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasparian, A.M.; Badawy, S.M. Utility of Fitbit Devices among Children and Adolescents with Chronic Health Conditions: A Scoping Review. mHealth 2022, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villasana, M.V.; Pires, I.M.; Sá, J.; Garcia, N.M.; Zdravevski, E.; Chorbev, I.; Lameski, P.; Flórez-Revuelta, F. Mobile Applications for the Promotion and Support of Healthy Nutrition and Physical Activity Habits: A Systematic Review, Extraction of Features and Taxonomy Proposal. Open Bioinform. J. 2019, 12, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Welk, G.J. Validity and Calibration of the Youth Activity Profile. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Mciver, K.L.; Pate, R.R. Conducting Accelerometer-Based Activity Assessments in Field-Based Research. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2005, 37, S531–S543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).