Abstract

Informal caregivers include family, friends, and significant others who provide important support for people who have attempted suicide or experienced suicidal ideation. Despite the prevalence of suicidal behaviour worldwide, they remain an understudied population. This review aimed to synthesise the literature on the experiences and support needs of informal caregivers of people who have attempted suicide or experienced suicidal ideation. We conducted a systematic review according to PRISMA guidelines. Searches of peer-reviewed literature in Medline, Emcare, Embase, EBM Reviews, and PsycINFO identified 21 studies (4 quantitative and 17 qualitative), published between 1986 and 2021. Informal carers commonly reported symptoms of depression and anxiety, for which they receive little assistance. They also expressed a desire for more involvement and education in the professional care of suicidality. Together, the studies indicated a need to improve the way informal caregiving is managed in professional healthcare settings. This review identified potential avenues for future research, as well as broad areas which require attention in seeking to improve the care of suicidal people and their caregivers.

1. Introduction

More than 700,000 people die by suicide worldwide each year [1]. In Australia, suicide is the leading cause of death in people aged 15–44, though affects a higher proportion of the older population [2]. In 2020 the age-standardised suicide rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was 27.9 per 100,000 vs. 12.1 per 100,000 people for the total Australian population [2]. However, the phenomenon of suicidality comprises a wider range of behaviours including suicidal ideation and non-lethal attempts. In 2019–2020 there were over 28,600 hospitalisations for self-harm in Australia, which provides an estimate of the extent of the phenomenon [3]. Given the magnitude of suicidal behaviour in the population, there is a clear need for prevention and care of suicidality across diverse ages and backgrounds.

Informal caregivers in the context of suicidality are a diverse range of people including “family, friends and significant others who support a loved one after a suicide attempt” [4], p. 4 who play a key role in the care of individuals/people who have suicidal thoughts or engage in suicidal behaviour [4,5]. In their 2021 review, Simes and colleagues found that most suicidal youth, including in Australia, do not receive professional mental healthcare, and that family-centred therapy is an important and underutilised form of care [6]. Indeed, much of the care of suicidal people occurs in an informal setting [7]. Informal caregivers, including family members, are therefore of key importance in suicide intervention [8].

Despite this, studies tend to overlook informal caregivers as a population, not just in the context of suicide research and prevention, but across many other health contexts [9,10]. The literature on this topic has gradually been increasing, leading to consideration of the value of family-centred care in the context of suicidality and self-harm [5,6]. However, despite the development of the field, there has been no systematic review of literature focussed on informal caregivers’ experiences and support needs while caring for a person at risk of suicide. It has been noted in other contexts that the vast amount of daily care provided by informal caregivers without support can lead to significant mental health burden [11]. Therefore, the lack of widespread understanding of informal caregiving in the context of suicidality may hide a significant public health issue.

Caregiver stress has been acknowledged as a significant source of psychological and physical morbidity in caregivers of diverse groups such as cancer patients [12,13] and dementia patients [14]. The effects of caregiver stress have been characterised as “widespread and unnecessary suffering, isolation, fear, error, and at times bankruptcy” [15], p. 1021. This highlights the effect of caregiver stress on both the caregivers themselves, and those being cared for.

This systematic review aims to synthesise the quantitative and qualitative research literature on the experiences and support needs of informal caregivers in the context of suicidality, and identify their common experience, support needs, and support received. This will be explored with the goal of formulating implications for practice and research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines [16] and was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021274108). The review involved systematic searches of the literature in Medline, Emcare, Embase, EBM Reviews and PsycINFO (all accessed via OVID in August 2021). The search in Medline used MeSH and text words: (attempted suicide.mp. OR Suicide, Attempted/OR suicide attempt.mp. OR non-fatal suicidal behaviour.mp. OR Suicidal Ideation/OR Suicidal behaviour.mp. OR self-harm.mp. OR self-injury.mp. or Self-Injurious Behavior/) AND (Family/or family.mp. OR informal carer.mp. OR carer.mp. OR caregiver*.mp. or Caregivers/OR spouse*.mp. OR Spouses/OR parent.mp. OR Parents/OR sibling*.mp. or Siblings/OR Grandparents/or grandparent*.mp. OR partner.mp. OR lived experience.mp) AND (support needs.mp. OR needs.mp.). A similar search string including headings and keywords was used in the other databases. The searches were limited to peer-reviewed publications in English but not by date of publication.

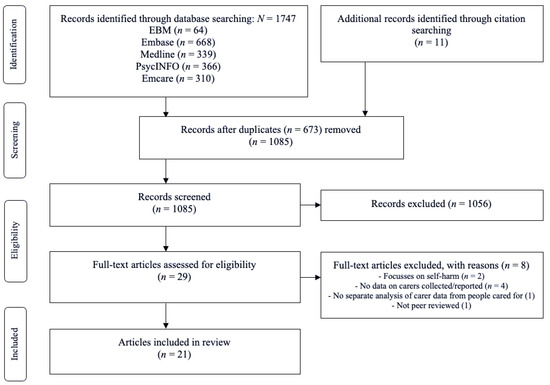

One researcher (G.L.) conducted the searches, and screened titles and abstracts of the leads regarding their potential eligibility. Researchers G.L. and K.K. assessed full texts of the selected abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with the third researcher (K.A.). Researcher G.L. hand searched the references of the included studies and review papers. Figure 1 details the search and selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if: (i) the study population consisted of informal caregivers of people who have attempted suicide and/or experienced suicidal ideation, (ii) the study used quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods, (iii) the study provided empirical data on the support needs of the study population, (iv) the study was published in English, (v) the study was peer-reviewed.

Studies were excluded if the study used other methods such as case studies or literature review.

2.3. Data Extraction

Researchers G.L. and K.K. independently extracted the following data by listing and comparing the data and main findings with each re-reading of the corpus: author, year and location of study, sample size, participants’ sex, age, caregivers’ relationships, study design, main results, and study limitations. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with the third researcher (K.A.).

2.4. Quality Assessment

Two researchers (G.L., K.K.) independently conducted the quality assessment and resolved disagreements through discussion with the third researcher (K.A.). No eligible study was excluded based on its quality. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form for Cohort Studies [17] was used to assess quantitative studies. The scale comprises eight items across three domains: (1) selection (four items), (2) comparability (one item), and (3) outcome (three items). Scores in each domain were summed to determine study quality as good, fair, or poor. The interrater reliability was substantial (κ = 0.77).

The qualitative studies were assessed using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [18]. The instrument consists of thirty-two items across three domains: (1) research team and reflexivity (eight items), (2) study design (fifteen items), and (3) analysis and findings (nine items). For each study, we calculated the number and percentage of items satisfied within each domain and across all domains. The interrater agreement was high (κ = 0.85).

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

This review identified 21 studies that investigated the experiences and support needs of informal caregivers of people experiencing suicidality. Four studies included quantitative data [19,20,21,22]. The other 17 studies were qualitative [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. In general, qualitative studies involved interviews or surveys with thematic analysis (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

The studies found were largely conducted in Western nations, including five studies in the USA [19,24,25,26,27], four in Australia [23,28,29,30], four in Sweden [20,21,22,31], one in the UK [32], two in Northern Ireland [33,34], two in Denmark [35,36] and one each in Canada [37], South Africa [38] and Taiwan [39].

A wide variety of people act as informal caregivers for suicidal people, though caregivers were predominantly female in all studies except the study by Sun and colleagues, in which nine participants were men and six were women (39). Two studies recruited only female caregivers [37,38] while the rest included mostly female caregivers, often approaching nearly 100%. For example, in Wayland et al.’s Australian survey with over 700 respondents, 86.9% were female [30].

Most studies chose to investigate parental caregivers of suicidal youths or adult children. Among two of the studies which reported recruiting a variety of caregiver relationships, caregivers were most often parents (44% [22] and 37.6% [19] of participants), while spouses predominated in the others [21,31,39]. Studies also included wider family members and friends [20,21,22,25,26,27,31,33,39]. Wayland’s study was unique in that the interviewees were mostly children providing care for parents experiencing suicidality [30].

3.2. Quality Assessment

Appendix A (Table A1) presents the methodological quality of the four quantitative studies. One study received a rating of ‘good’ quality [19], and the others rated as ‘poor’ [20,21,22]. Studies tended to score well in the ‘selection’ domain, but tended to score poorly in the ‘comparability’ and the ‘outcome’ domain by relying on self-reported outcomes. Appendix B (Table A2) outlines the quality assessment of the 17 qualitative studies. The studies reported between 44% [27] and 94% of the COREQ criteria [28]. Most studies reported only few items across the ‘research team and reflexivity’ domain (on average 38% of items were reported). However, studies reported more items in the ‘study design’ (60%) and ‘analysis and findings’ (75%) domains.

3.3. Study Findings Quantitative Studies

3.3.1. Emotional Burden

Psychological and practical supports were a noted requirement of caregivers [21]. Magne-Ingvar and colleagues found that 55% of caregivers had provided psychological support and one in three had helped with practical matters [21]. Of these people, 57% described it as a burden. Accordingly, themes of stress, and anxiety were noted as central elements of the informal caregiver experience, and these psychological stresses were significant enough to manifest at times in physical ill health [21,22].

Regarding the source of this stress, disruption to family life was reported among the quantitative studies [21]. In addition to stress and anxiety, themes of depression and low mood were noted caregiver emotional responses in two studies [19,21]. Notably, Chessick and colleagues identified that these responses are modulated by factors specific to the suicidal person: caregivers tended to experience higher levels of depression when caring for people with worse daily function due to their mental status, or less educational attainment [19].

An additional reported source of stress is that of reduced work and leisure time for caregivers: 28% of caregiver relatives in Kjellin and Östman’s study had reduced leisure time, with a smaller amount reporting reduced time at work and one third being unable to spend time alone [20].

3.3.2. Desired Supports

Caregivers requested a need for personal care and support, with Kjellin and Östman noting that their results “corroborate the need for psychiatric services to involve and support relatives of psychiatric patients with suicidal behaviour.” [20], p.11. In one study by Magne-Ingvar and colleagues, 53% of caregivers desired counselling together with the suicidal person, with a smaller proportion expressing a desire for more private counselling [21]. This study again noted caregivers’ wishes to be more involved in the professional care of their suicidal loved ones [21].

There is also a possibility that caregiver strain would be relieved by provision of professional care to those experiencing suicidality. In addition to their personal needs, Magne-Ingvar and colleagues sought for suggestions by caregivers of future supports that would benefit significant others experiencing suicidality [21]. Notably, most participants in this study had significant others already receiving such treatment.

3.4. Study Findings Qualitative Studies

3.4.1. Emotional Burden

The studies noted several caregiver responsibilities which had the potential to contribute to caregiver emotional burden. These included managing the risk of suicide in care recipients as well as psychological and practical supports [30]. Wayland and colleagues [30] enumerated specific domains which caregivers had to take on in caring for family members; these included financial assistance/decisions, transport, phone calls and life advice.

Accordingly, stress, fear, anxiety, and hypervigilance were central elements of the informal caregiver experience in most studies [24,26,28,29,30,33,34,36,38,39]. Chronic stress, at times manifesting in post-traumatic stress disorder, was ubiquitous in one study [29]. In addition, Sun and colleagues attributed a certain amount of stress to the open family environment particular to the prevailing culture in Taiwan, where that study was carried out [39]. This family environment was viewed as conflicting with parents’ desires to remain on guard for their suicidal family members [39]. Meanwhile, Fogarty and colleagues described tensions as arising mainly from the difficulty in managing suicide risk while maintaining a working relationship with the care recipient [23].

The stress experienced by caregivers can be further characterised as a “double trauma”, with the added damage that caregiving inflicts on the family and relationships [36]. Daly’s study of maternal caregivers defined themes of “failure as a good mother” and “rejection” by their children [37]. A disrupted family life was corroborated by various studies [28,29,32,34,38]. Importantly, relationship disruption was not necessarily a ubiquitous experience. Roach identified that youth peer caregivers often felt “honoured” to provide support and that the experience was overall positive for their relationships [26].

3.4.2. Desired Supports

Caregivers commonly requested a need for emotional support, including from dedicated psychiatric services [24]. McLaughlin and colleagues described simple measures to reduce burden such as follow-up calls from healthcare staff to more isolated caregivers, as well as more complex supports such as respite services [33].

There are more basic measures that improve caregiver perceptions of the healthcare system. Inscoe and colleagues identified that caregivers positively regarded clinician empathy, validation and nonjudgment [24], while others reported that simply being asked if they were coping at home would have been worthwhile [30,33]. McLaughlin and colleagues seem to have found a lack of support to be a ubiquitous and damaging experience among participants, with one participant stating “THERE WAS NOBODY TO TURN TO” [participants’ emphasis] ([33], p. 214).

Many studies identified caregivers’ wishes to be more involved in the professional care of their suicidal loved ones [24,28,33]. In one study, 37.6% of family members of suicidal individuals felt emergency department staff did not wish to communicate with them about their loved one [27]. McLaughlin and colleagues noted this type of involvement in care is possible for suicidal children, but that automatic involvement of caregivers may abruptly stop when children reach adulthood [33]. They also found that more than one in five participants did not feel they had been well treated by staff [33]. Other studies noted further departures from expected care. Giffin and colleagues reported that hospital admissions often did not meet the needs of the family, being only brief or in response to crisis [29], while Dempsey and colleagues found that clinicians needed to better explain the reasons for continued admission vs. discharge [28].

Discharge from hospital services following a suicide attempt may be a significant trigger for caregiver distress, in part since assessment of suicide risk in a hospital environment did not necessarily equate to that of the home environment [30]. Many studies identified that discharge often occurred without informal caregivers receiving effective education about managing suicide risk out of hospital [28,29,32,33,38]. Others highlighted the importance of education about suicidality “warning signs” [24,26]. In the study by Roach and colleagues, youth peer caregivers were cognisant of a need to involve adults when suicidality became active [26].

Caregivers often experienced professional care for suicidal patients as fragmented and un-cooperative, at times leading to contradictory health advice [28,29,33]. Caregivers have reported difficulties in navigating a complicated mental health system [23,24], and feeling that clinicians do not know what constitutes safe practice for informal caregivers [28]. This dependence on community services which may fail to provide sufficient care for suicidal people was noted as a key issue by Fogarty and colleagues [23]. Study participants therefore expressed a desire for skills training for informal caregivers to reduce reliance on services and improve collaboration with the services [23,30].

4. Discussion

This review identified 21 studies published within the last four decades, across nine highly developed nations. The caregivers studied differed in age, nationality, relationship, and so on. However, the preponderance of female informal caregivers was similar across studies. Some studies noted the relative lack of male caregivers as a limitation [24,28] and Inscoe and colleagues noted that “more research is needed to understand the role of male caregivers in accessing and participating in treatment” ([24], p. 6.) However, there is a similar preponderance of female caregivers in the context of other medical conditions or disabilities, such as elderly people suffering from dementia or other physical conditions, and this possibly reflects traditional societal gender roles [40].

The reviewed studies indicated that the psychological impact of suicidality on informal caregivers should not be underestimated. Suicidality affects a wide range of people surrounding the suicidal person, including people with pre-existing mental health issues [31]. Caregiving stress was reported to disrupt family dynamics as well, supporting previous studies that stigma around suicide may impact families as frequently as the suicidal person [41]. This disruptive stress is an impediment to the care of suicidal people, and potentially a real danger for caregivers; several studies discuss the possibility of burnout and resentment, or indeed the possibility of passive “death wishes” developing in unsupported caregivers [25,31,39].

Regarding depression and low mood, Chessick and colleagues identified that these emotional responses are modulated by factors specific to the suicidal person [19]. Caregivers tended to experience higher levels of depression when caring for people with worse daily function due to their mental status, or less educational attainment [19]. However, these mood states do not necessarily arise de novo when people take on a caregiving role. Wolk-Wasserman observed that a majority of family/spousal caregivers experienced their own psychiatric issues such as substance use problems, psychosis, and previous suicide attempts [31].

In addition to social context [39] and suicide risk [23], this review identifies gender inequity as a potential contributor to caregiver stress. Chessick and colleagues suggested that male spousal caregivers might “assume that traditionally female role functions are relatively easily performed” possibly leading to greater disappointment and caregiver burden when that expectation is not met by the female partner ([19], p. 489). Buus and colleagues noted that between parental caregivers, the stereotype of women needing to talk about issues more than men created relationship conflict, which then contributed to caregiver stress [36]. The gender-related element of suicidality is further reinforced by the fact that women tend to be rated as more frequently suicidal by certain measures than men [42]. Less reliance on traditional gender roles might reduce caregiver burden by spreading care and stress more equitably within families.

The significant psychological burden that suicidality has on informal caregivers suggests a need for professional interventions for caregivers. McLaughlin and colleagues indicated that perceived stigma often prevented family caregivers from seeking help from healthcare services, and that clinician warmth and empathy are important in encouraging help seeking [34]. It is therefore recommended that clinicians enquire about caregiver coping to create a permissive help-seeking environment.

The need for professional interventions is supported by Wolk-Wasserman’s finding that most caregivers for suicidal people themselves had psychiatric issues [31]. Indeed, it is possible that targeting psychosocial interventions to family caregivers may be a worthwhile public health intervention given the indications of a partial heredity of suicidality [43], and the likelihood of shared socio-economic status between caregivers and care recipients in the studies examined. As such, healthcare workers should be prepared to identify caregivers suffering unmanageable stress and to direct them to relevant services [44]. Screening procedures for caregiver mental health are valuable and clinicians may benefit from education on assessment and intervention strategies as has been described in other caregiving contexts [44].

Informal caregivers who choose to seek help should have access to formal support services. These could take the form of respite care [34] or psychological counselling [21,45]. However, in certain locations, the prohibitive cost of psychological support is a further barrier to formal care [24]. As a result, the provision of informal caregiver support services must be facilitated by systemic support such as financially equitable healthcare or financial aid, as has been identified in palliative caregiving contexts [46].

The array of mental health services is confusing to many informal caregivers [23,24] and efforts should be made to reduce the impact of this issue. Clear, accessible information, for example on a dedicated government website, about what options are available and appropriate at each step of a suicidal person’s healthcare could alleviate the caregivers’ stress and improve care delivery. However, some studies have reported caregivers’ perception that care services are disparate and fragmented, creating a barrier to access [28,29,33]. This is a systemic health issue which has also been found in other caregiving contexts such as chronic disease [47,48], suggesting the need for systemic healthcare changes and streamlining.

Informal caregivers often express a wish to be included in the formal care [21,24,28,33]. However, involvement of informal caregivers in formal settings is not the default when the suicidal person is an adult without legal guardians [33]. Indeed, in some contexts even caregivers of children experience this lack of involvement [49]. This issue can in part be addressed if healthcare professionals offer warmth and empathy to informal caregivers, thereby creating an environment where informal caregivers feel as though their unique perspective is heard, and their distress is acknowledged [49].

This review found that informal caregivers often feel ill-prepared for the post-discharge period [26,27,30,33], particularly around identifying active suicidality [24,26]. Indeed, it has been noted that the efficacy of suicide risk assessment in the clinical setting is limited [50]. This highlights a clear area for reducing informal caregiver burden; healthcare providers should offer basic education about assessing risk and thereby improve the safety of their clients after discharge from acute care. Clear guidelines for formal caregivers are required to ensure safety and accuracy of this education, and the need for such guidelines is further highlighted by the finding that formal caregivers may differ widely in their advice for informal caregivers [28].

Limitations

This review was limited to English language literature. Future reviews could involve additional databases or studies in other languages. Most studies were qualitative, or cross-sectional, and involved mostly female participants from western countries. The interview methodologies of the quantitative studies are variable and lack comparability and are therefore not conclusive. Individual studies possessed their own inherent limitations, including sample size or method, which are outlined in Appendix A and Appendix B. Quality assessment of all studies was performed in lieu of risk of bias analysis. In the Australian context, studies were predominantly of Caucasian subjects and therefore do not capture the range of cultural diversity present in the wider Australian population. Overall, no study focussed on First Nations populations despite the known high prevalence of suicide in this group.

5. Conclusions

The extent of psychosocial stress endured by informal caregivers of people experiencing suicidality is significant. Despite this, they remain a poorly studied population. More research is needed, including studies of caregiver experiences and intervention studies aimed at determining how best to meet their needs.

The identified needs and wishes of informal caregivers suggest some actions that can be taken by healthcare professionals involved in the care of suicidal people. Healthcare professionals should be prepared to screen these caregivers for issues including depression and anxiety, with offers of formal assistance where necessary. Informal caregivers routinely express a desire for involvement in formal care, so efforts should be made where possible to seek insight and assistance from willing informal caregivers. Healthcare professionals should be able to provide education about managing suicide risks and active suicidality when asked.

Finally, the widespread lack of understanding of these informal caregivers suggests a potentially untapped wealth of experience. Informal caregivers in the setting of suicidality have described significant benefits of peer support e.g., [32], and this represents a potential avenue for improving quality of life for this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K., K.A. and G.L.; methodology, G.L., K.K. and K.A.; software, G.L.; validation, K.K. and K.A.; formal analysis, G.L. and K.K.; investigation, G.L.; data curation, G.L., K.K. and K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.; writing—review and editing, G.L., K.K. and K.A.; supervision, K.K. and K.A.; project administration, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

K.K. was supported by an Innovation Research Grant of the Suicide Prevention Research Fund. K.A. was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (GNT1157796). The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Quality assessment 1 of quantitative studies.

Table A1.

Quality assessment 1 of quantitative studies.

| Topic | Chessick et al., 2007 [19] | Kjellin & Ostman, 2005 [20] | Magne-Ingvar & Ojehagen, 1999 [21] | Magne-Ingvar & Ojehagen, 1999 [22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | ||||

| 1. Representativeness of the exposed cohort | ||||

| a. Truly representative (one star) | ||||

| b. Somewhat representative (one star) | X | X | X | X |

| c. Selected group | ||||

| d. No description | ||||

| 2. Selection of the non-exposed cohort | ||||

| a. Drawn from the same community as the exposed cohort (one star) | X | X | ||

| b. Drawn from a different source | ||||

| c. No description | n/a | n/a | ||

| 3. Ascertainment of exposure | ||||

| a. Secure record (e.g., surgical record) (one star) | X | X | ||

| b. Structured interview (one star) | X | X | ||

| c. Written self-report | ||||

| d. No description | ||||

| e. Other | ||||

| 4. Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | ||||

| a. Yes (one star) | ||||

| b. No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Comparability | ||||

| 1. Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis controlled for confounders | ||||

| a. The study controls for age, sex and marital status (one star) | X | |||

| b. Study controls for other factors (list) (one star) | X | |||

| c. Controls are not comparable | X | n/a | n/a | |

| Outcome | ||||

| 1. Assessment of outcome | ||||

| a. Independent blind assessment (one star) | ||||

| b. Record linkage (one star) | ||||

| c. Self-report | X | X | X | |

| d. No description | ||||

| e. Other | X | |||

| 2. Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | ||||

| a. Yes (one star) | X | X | X | X |

| b. No | ||||

| Indicate the mean duration of follow-up and a brief rationale for the assessment above | Life-time prevalence | <1 month; >1 month | Within days | One year |

| 3. Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | ||||

| a. Complete follow-up, all subjects accounted for (one star) | X | X | ||

| b. Subjects lost to follow-up unlikely to introduce bias, number lost less than or equal to 20% or description of those lost suggested no different from those followed (one star) | X | X | ||

| c. Follow-up rate less than 80% and no description of those lost | ||||

| d. No statement | ||||

| Stars | ||||

| Selection | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Comparability | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Outcome | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Rating | Good | Poor | Poor | Poor |

1 Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form for Cohort Studies [17]. Note: A study can be given a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the Selection and Outcome categories. A maximum of two stars can be given for Comparability. Thresholds for converting the Newcastle-Ottawa scales to AHRQ standards (good, fair, and poor): Good quality: 3 or 4 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Fair quality: 2 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Poor quality: 0 or 1 star in selection domain OR 0 stars in comparability domain OR 0 or 1 stars in outcome/exposure domain.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Quality assessment 1 of qualitative studies.

Table A2.

Quality assessment 1 of qualitative studies.

| Topic | Buus et al., 2014 [36] | Byrne et al., 2008 [32] | Cerel et al., 2006 [27] | Daly, 2005 [37] | Dempsey et al., 2019 [28] | Fogarty et al., 2018 [23] | Giffin, 2008 [29] | Inscoe et al., 2021 [24] | McLaughlin et al., 2014 [34] | McLaughlin et al., 2016 [33] | Ngwane et al., 2019 [38] | Nosek, 2008 [25] | Nygaard et al., 2019 [35] | Roach et al., 2020 [26] | Sun et al., 2008 [39] | Wayland et al., 2020 [30] | Wolk-Wasserman, 1986 [31] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Personal characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Interviewer/facilitator | p.2 825 | p. 496 | p. 28 | S.1 | p. 263 | p. 134 | p. 2 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 135 | p. 1947 | p. 663 | p. 484 | ||||

| 2 | Credentials | p. 823 | p. 494 | p. 341 | p. 28 | S.1 | p. 261 | p. 2 | p. 44 | p. 133 | p. 1939 | p. 661 | ||||||

| 3 | Occupation | p. 823 | p. 494 | p. 341 | p. 28 | S.1 | p. 133 | p. 1 | p. 236 | p. 44 | p. 133 | p. 1939 | p. 661 | p. 484 | ||||

| 4 | Gender | S.1 | p. 263 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Experience and training | p. 825 | p. 494 | S.1 | p. 2 | p. 236 | pp. 483–484 | |||||||||||

| Relationship with participants | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Relationship established | S.1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Participant knowledge of the interviewer | p. 825 | S.1 | p. 34 | ||||||||||||||

| 8 | Interviewer characteristics | p. 494 | S.1 | p. 133 | ||||||||||||||

| Domain 2: Study design | ||||||||||||||||||

| Theoretical framework | ||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Methodological orientation and theory | p. 826 | p. 497 | p. 342 | p. 24 | p. 105 | p. 263 | p. 134 | p. 2 | p. 237 | pp. 213 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 134 | p. 33 | p. 1941 | p. 663 | |

| Participant selection | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Sampling | p. 825 | p. 496 | p. 342 | pp. 24–25 | p. 105 | p. 262 | p. 134 | p. 2 | p. 236 | pp. 212–213 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 134 | p. 33 | p. 1941 | p. 663 | p. 484 |

| 11 | Method of approach | p. 825 | p. 496 | p. 342 | pp. 24–25 | p. 105 | p. 262 | p. 2 | p. 236 | p. 213 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 134 | p. 33 | p. 1941 | |||

| 12 | Sample size | p. 825 | p. 496 | p. 342 | p. 24 | p. 104 | p. 263 | p. 134 | p. 2 | p. 236 | p. 213 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 134 | p. 34 | p. 1941 | p. 663 | p. 483 |

| 13 | Non-participation | p. 825 | p. 104 | p. 134 | ||||||||||||||

| Setting | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Setting of data collection | p. 825 | p. 496 | p. 342 | p. 25 | p. 105 | p. 2 | p. 237 | p. 213 | p. 376 | p. 135 | p. 33 | p. 1942 | p. 663 | p. 485 | |||

| 15 | Presence of non-participants | p. 496 | ||||||||||||||||

| 16 | Description of sample | p. 827 | p. 496 | p. 343 | p. 24 | pp. 104–105 | p. 263 | p. 134 | pp. 2–3 | p. 237 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 134 | p. 34 | p. 1941 | p. 665 | p. 483 | |

| Data collection | ||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Interview guide | p. 825–826 | p. 496 | p. 25 | S.1 | p. 134 | p. 3 | p. 237 | p. 213 | pp. 135–136 | p. 33 | p. 1942 | pp. 673–675 | p. 485 | ||||

| 18 | Repeat interviews | S.1 | p. 484 | |||||||||||||||

| 19 | Audio/visual recording | p. 826 | p. 497 | p. 25 | p. 105 | p. 263 | p. 3 | p. 237 | p. 213 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 135 | p. 33 | p. 1939 | p. 663 | p. 485 | ||

| 20 | Field notes | p. 825 | p. 497 | S.1 | p. 263 | p. 376 | p. 34 | p. 485 | ||||||||||

| 21 | Duration | p. 826 | p. 496 | p. 25 | p. 105 | p. 263 | p. 2 | p. 237 | p. 135 | p. 34 | p. 1941 | |||||||

| 22 | Data saturation | p. 109 | p. 263 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 33 | p. 1941 | |||||||||||

| 23 | Transcripts returned | S.1 | p. 134 | |||||||||||||||

| Domain 3: Analysis and findings | ||||||||||||||||||

| Data analysis | ||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | Number of data coders | p. 497 | p. 342 | p. 25 | S.1 | p. 263 | p. 3 | p. 237 | p. 213 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 1947 | p. 664 | |||||

| 25 | Description of the coding tree | p. 826 | p. 501 | pp. 344–345 | p. 25–27 | p. 107 | pp. 263–264 | pp. 237–238 | p. 213 | p. 377 | p. 40 | p. 135–136 | p. 35 | p. 1943 | pp. 664–665 | |||

| 26 | Derivation of themes | p. 826 | p. 497 | p. 342 | p. 25 | p. 106 | p. 263 | p. 134 | p. 3 | p. 237 | p. 213 | p. 376 | p. 38 | p. 135 | p. 34 | p. 1942 | p. 663 | p. 485 |

| 27 | Software | p. 263 | p. 3 | p. 135 | p. 1942 | p. 663 | ||||||||||||

| 28 | Participant checking | p. 25 | S.1 | p. 134 | p. 237 | p. 213 | p. 38 | |||||||||||

| Reporting | ||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | Quotations presented | p. 827–829 | pp. 497–500 | pp. 344–346 | p. 26–27 | p. 107 | pp. 264–266 | pp. 134–137 | pp. 3–5 | pp. 238–239 | pp. 213–215 | pp. 377–379 | pp. 38–41 | pp. 136–137 | pp. 34–37 | pp. 1944–46 | pp. 665–669 | pp. 492–494 |

| 30 | Data and findings consistent | p. 829–830 | pp. 500–503 | p. 346 | p. 27–28 | pp. 109–110 | pp. 266–268 | pp. 137 | pp. 5–6 | pp. 239–p240 | pp. 213–216 | pp. 380–381 | pp. 41–43 | pp. 138–139 | pp. 37–39 | pp. 1946–47 | pp. 669–671 | pp. 494–498 |

| 31 | Clarity of major themes | p. 826–829 | pp. 497–500 | p. 344–346 | pp. 25–27 | pp. 105–109 | pp. 263–266 | pp. 134–137 | pp. 3–5 | p. 238–239 | pp. 213 | pp. 377–380 | pp. 38–41 | pp. 136–137 | pp. 34–37 | pp. 1942–46 | pp. 664–669 | pp. 487–494 |

| 32 | Clarity of minor themes | p. 500 | pp. 105–109 | pp. 263–266 | pp. 3–5 | p. 213 | pp. 377–380 | pp. 136–137 | pp. 1942–46 | pp. 664–669 | ||||||||

| Scoring | ||||||||||||||||||

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | 5/8 (63%) | 5/8 (63%) | 2/8 (25%) | 3/8 (38%) | 8/8 (100%) | 3/8 (38%) | 3/8 (38%) | 4/8 (50%) | 2/8 (25%) | 0/8 (0%) | 1/8 (13%) | 3/8 (38%) | 3/8 (38%) | 1/8 (13%) | 3/8 (38%) | 3/8 (38%) | 3/8 (38%) | |

| Domain 2: Study design | 11/15 (73%) | 11/15 (73%) | 6/15 (40%) | 9/15 (60%) | 14/15 (93%) | 9/15 (60%) | 6/15 (40%) | 9/15 (60%) | 9/15 (60%) | 7/15 (47%) | 9/15 (60%) | 7/15 (47%) | 10/15 (67%) | 11/15 (73%) | 10/15 (67%) | 7/15 (47%) | 8/15 (53%) | |

| Domain 3: Analysis and findings | 5/9 (56%) | 7/9 (78%) | 6/9 (67%) | 7/9 (78%) | 8/9 (89%) | 8/9 (89%) | 5/9 (56%) | 7/9 (78%) | 7/9 (78%) | 8/9 (89%) | 7/9 (78%) | 7/9 (78%) | 7/9 (78%) | 5/9 (56%) | 8/9 (89%) | 8/9 (89%) | 4/9 (44%) | |

| Total | 21/32 (66%) | 23/32 (72%) | 14/32 (44%) | 19/32 (59%) | 30/32 (94%) | 20/32 (63%) | 14/32 (44%) | 20/32 (63%) | 18/32 (56%) | 15/32 (47%) | 17/32 (53%) | 17/32 (53%) | 20/32 (63%) | 17/32 (53%) | 21/32 (66%) | 18/32 (56%) | 15/32 (47%) | |

1 Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [18]. 2 In this table, “p.” refers to page numbers.

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide in the World: Global Health Estimates; Contract No.: WHO/MSD/MER/19.3; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death, Australia. ABS Website. 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/2020 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Australian Insitute of Health and Welfare. Suicide & Self-Harm Monitoring AIHW Website. 2021. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/intentional-self-harm-hospitalisations/intentional-self-harm-hospitalisations-by-states (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Coker, S.; Wayland, S.; Maple, M.; Blanchard, M. Better Support: Understanding the needs of family and friends when a loved one attempts suicide. Techn. Rep. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysinska, K.; Andriessen, K.; Ozols, I.; Reifels, L.; Robinson, J.; Pirkis, J. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for family members and other informal support persons of individuals who have made a suicide attempt: A systematic review. Crisis, 2021; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simes, D.; Shochet, I.; Murray, K.; Sands, I.G. A systematic review of qualitative research of the experiences of young people and their caregivers affected by suicidality and self-harm: Implications for family-based treatment. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.M.; Kropf, N.P. Formal and informal support for older adults with severe mental illness. Aging Ment. Health 2009, 13, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, H.C.; Chang, S.T.; Tong, H.Q.; Meneses, M.A.; Yuzbasioglu, R.F.; Hien, D. Intersection of suicidality and substance abuse among young Asian-American women: Implications for developing interventions in young adulthood. Adv. Dual Diagn. 2014, 7, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okonta, C. The Needs of Family Caregivers of a Family Member with Schizophrenia: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maayan, N.; SoaresWeiser, K.; Lee, H. Respite care for people with dementia and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 16, CD004396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, R.D.; Tmanova, L.L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, K.M.; Kim, Y.; Carver, C.S.; Cannady, R.S. Effects of caregiving status and changes in depressive symptoms on development of physical morbidity among long-term cancer caregivers. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areia, N.P.; Fonseca, G.; Major, S.; Relvas, A.P. Psychological morbidity in family caregivers of people living with terminal cancer: Prevalence and predictors. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, S.; Moyle, W.; Taylor, T.; Creese, J.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M. Homicidal ideation in family carers of people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, J. Strategies to ease the burden of family caregivers. JAMA 2014, 311, 1021–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale Cohort Studies; University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99082/bin/appb-fm4.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chessick, C.A.; Perlick, D.A.; Miklowitz, D.J.; Kaczynski, R.; Allen, M.H.; Morris, C.D.; Marangell, L.B.; STED-BD Family Experience Collaborative Study Group. Current suicide ideation and prior suicide attempts of bipolar patients as influences on caregiver burden. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2007, 37, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellin, L.; Ostman, M. Relatives of psychiatric inpatients–Do physical violence and suicide attempts of patients influence family burden and participation in care? Nord. J. Psychiatry 2005, 59, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne-Ingvar, U.; Oejehagen, A. Significant others of suicide attempters: Their views at the time of the acute psychiatric consultation. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1999, 34, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne-Ingvar, U.; Ojehagen, A. One-year follow-up of significant others of suicide attempters. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1999, 34, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, A.S.; Spurrier, M.; Player, M.J.; Wilhelm, K.; Whittle, E.L.; Shand, F.; Christensen, H.; Proudfoot, J. Tensions in perspectives on suicide prevention between men who have attempted suicide and their support networks: Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inscoe, A.B.; Donisch, K.; Cheek, S.; Stokes, C.; Goldston, D.B.; Asarnow, J.R. Trauma-informed care for youth suicide prevention: A qualitative analysis of caregivers’ perspectives. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy, 2021; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek, C.L. Managing a depressed and suicidal loved one at home: Impact on the family. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2008, 46, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, A.; Thomas, S.P.; Abdoli, S.; Wright, M.; Yates, A.L. Kids helping kids: The lived experience of adolescents who support friends with mental health needs. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 34, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerel, J.; Currier, G.W.; Conwell, Y. Consumer and Family Experiences in the Emergency Department Following a Suicide Attempt. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006, 12, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, S.-J.A.; Halperin, S.; Smith, K.; Davey, C.G.; McKechnie, B.; Edwards, J.; Rice, S.M. “Some guidance and somewhere safe”: Caregiver and clinician perspectives on service provision for families of young people experiencing serious suicide ideation and attempt. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 23, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffin, J. Family experience of borderline personality disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2008, 29, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wayland, S.; Coker, S.; Maple, M. The human approach to supportive interventions: The lived experience of people who care for others who suicide attempt. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk-Wasserman, D. Suicidal communication of persons attempting suicide and responses of significant others. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1986, 73, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, S.; Morgan, S.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Boylan, C.; Crowley, S.; Gahan, H.; Howley, J.; Staunton, D.; Guerin, S. Deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents: A qualitative study exploring the needs of parents and carers. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C.; McGowan, I.; Kernohan, G.; O’Neill, S. The unmet support needs of family members caring for a suicidal person. J. Ment. Health 2016, 25, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C.; McGowan, I.; O’Neill, S.; Kernohan, G. The burden of living with and caring for a suicidal family member. J. Ment. Health 2014, 23, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, L.; Fleischer, E.; Buus, N. Sense of Solidarity among Parents of Sons or Daughters Who Have Attempted Suicide: An In-depth Interview Study. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 40, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buus, N.; Caspersen, J.; Hansen, R.; Stenager, E.; Fleischer, E. Experiences of parents whose sons or daughters have (had) attempted suicide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, P. Mothers living with suicidal adolescents: A phenomenological study of their experiences. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2005, 43, 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ngwane, V.E.; van der Wath, A.E. The psychosocial needs of parents of adolescents who attempt suicide. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.K.; Long, A. A theory to guide families and carers of people who are at risk of suicide. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family-caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, K.; Hackney, S.; Skehan, J. Information needs of people after a suicide attempt: A thematic analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.; Mergl, R.; Kohls, E.; Székely, A.; Gusmao, R.; Arensman, E.; Koburger, N.; Hegerl, U.; Rummel-Kluge, C. A cross-national study on gender differences in suicide intent. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baldessarini, R.J.; Hennen, J. Genetics of Suicide: An Overview. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2004, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, M.; Ashby, B.; Costello, L.; Ehmer, A.; Serrano, V.; von Schulz, J.; Wolcott, C.; Talmi, A. From planning to implementation: Creating and adapting universal screening protocols to address caregiver mental health and psychosocial complexity. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 9, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, K.; Rossetti, J.; Musker, K. Concerns most important to parents after their child’s suicide attempt: A pilot study and collaboration with a rural mental health facility. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 32, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.; Robinson, J.; Connolly, M.; Hulme, C.; Kang, K.; Rowland, C.; Larkin, P.; Meads, D.; Morgan, T.; Gott, M. Equity and the financial costs of informal caregiving in palliative care: A critical debate. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, B.A.; Northouse, L. Who cares for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, C.L.; Jawid, M.Y.; Alhusen, J.; Muheriwa, S.R.; Ramunas, M.M.; Hooshmand, M. Healthcare providers’ experiences with gaps, barriers, and facilitators faced by family caregivers of children with respiratory diseases. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 52, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andershed, B.; Ewertzon, M.; Johansson, A. An isolated involvement in mental health care-experiences of parents of young adults. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wand, T. Investigating the evidence for the effectiveness of risk assessment in mental health care. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).