Abstract

Background: Although undergoing an abortion is stressful for most women, little attention has been given to their psychological wellbeing. This protocol aims to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and primary effects of a complex intervention to promote positive coping behaviors and alleviate depression symptoms among Chinese women who have undergone an abortion. Methods: A two-arm randomized controlled trial design will be used. Participants will be recruited at their first appointment with the abortion clinic and randomly allocated to receive either the Stress-And-Coping suppoRT (START) intervention (in addition to standard abortion care) or standard care only. All participants will be followed-up at two- and six-weeks post-abortion. Approval has been granted by local and university ethics committees. This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Discussion: The results will assist refinement and further evaluations of the START intervention, contribute to improved abortion care practices in China, and enrich the evidence on improving women’s psychological well-being following abortion in China. Trial registration: Registered at the Chinese Clinical Trials.gov: ChiCTR2100046101. Date of registration: 4 May 2021.

1. Introduction

Induced abortion is common around the world. In 2015–2019, a third of all pregnancies ended in abortion (approximately 77.3 million abortions each year) [1]. Accessing good-quality abortion care is a fundamental human right, an important component of sexual and reproductive health services, and an essential way to achieve global health commitments [2] such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [3]. Generally, abortion is physically safe when conducted using WHO-recommended methods by appropriately trained professionals [4]. For most women, the main challenge when choosing a first-trimester abortion is their emotional and psychological wellbeing [5]. Some women cope well with abortion and do not experience negative psychological consequences [6,7]. Some might even find positive meaning and embrace healthy behaviours after an abortion [8,9], whereas some report ongoing distress and mental health issues [5,10].

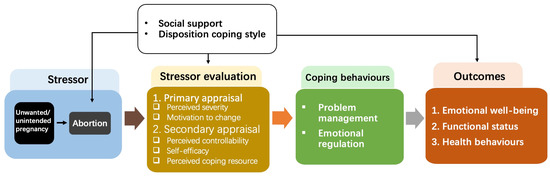

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping helps to explain the psychological variability of abortion [10,11]. According to this model, abortion is a dynamic stressful life event that happens in response to an unwanted/unintended pregnancy. In this circumstance, a woman first appraises the significance/severity of the pregnancy and then evaluates her options and coping resources at her disposal [10,12]. A woman’s appraisal mediates her coping behaviours and the psychological consequences of an abortion (see Figure 1) [12]. The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping suggests that by offering women the support they need, they can adjust their coping processes and achieving positive health outcomes.

Figure 1.

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping.

Despite the critical role of support to women accessing abortion, little attention has been paid to the psychosocial aspects of care [13]. A recently published systematic review found that in the past ten years, only ten experimental studies had been conducted to address the psychological needs of women undergoing abortion [14]. All interventions used a single-component design (e.g., music therapy, information support, or implementation of mandated waiting or counselling policies), and none were informed by a theoretical framework. Conflicting outcomes and methodological limitations hindered conclusions about which intervention could reasonably be adopted to improve women’s psychological well-being [14].

Abortion occurs in a socio-cultural context, and local policies regarding abortion accessibility play an important role in women’s psychological response toward an abortion. As the most populous country in the world, about 10 million abortions were conducted in China in 2019 [15]. China has one of the most liberal abortion policies amongst Asian countries, which allows first-trimester abortion without restriction, except for the prohibition of sex-selective abortions. Abortion is also socially acceptable in China, and most abortions that occur in China are due to unwanted pregnancies consistent with a societal desire for small families and timed birth. A recent study revealed that around a quarter of women seeking an abortion in China experienced high stress and moderate-to-severe depression [16]. Chinese women’s unmet support needs when seeking abortion were predictive of adverse psychological outcomes.

In the absence of available evidence, our research team developed the STress-And-coping suppoRT intervention (START). Underpinned by the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, the START intervention will provide women with information, coping skills, and support to achieve positive short- and long-term health. The intervention is innovative and based on (1) current available evidence, (2) a sound understanding of the target population, (3) informed by Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for complex interventions [17], (4) the Intervention Mapping (IM) framework [18], and (5) a five-step iterative pathway to gradually shape the intervention design [19].

The aim of this trail is to assess the START intervention among Chinese women undergoing an abortion. Its specific objectives are to:

- Determine the feasibility of the START intervention according to eligibility, recruitment, intervention delivery, and retention data;

- Evaluate the acceptability of the START intervention among participants based on the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) of Health Care Interventions;

- Test the preliminary efficacy of the START intervention on women’s depression symptoms, coping behaviors, self-efficacy, perceived support levels, intimate relationship satisfaction, post-abortion personal growth, and abortion relevant outcomes compared with women receiving standard abortion care.

2. Materials and Methods

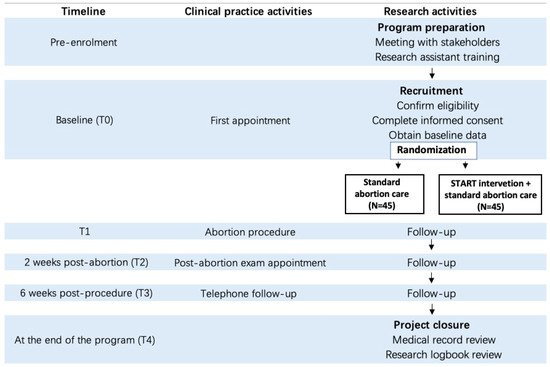

The study adopts a two-arm randomized controlled trial design with quantitative and qualitative information collected. Participants will be randomly allocated to receive either the START intervention in addition to standard abortion care or standard abortion care only with a 1:1 allocation rate. The study design is directed by the CONSORT statement and its extensions [20,21] and the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 guideline for protocols of randomized trials [22]. The research activities inconsistent with the real-world clinical practice are outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SPIRIT standard flow diagram.

2.1. Setting

This study will be conducted in the Family Planning and Reproductive Health Centre (FPRHC) of a tertiary hospital in Beijing, China. Participants will be recruited from the outpatient unit of the FPRHC, where abortion-related services are normally provided.

2.2. Participants

Women will be invited to participate in the study if they meet the following criteria: (1) Chinese citizens or living in China; (2) can speak, read, and write in Chinese; (3) are 18 years or older; (4) seeking termination of an intrauterine pregnancy for non-medical reasons; (5) less than 14 gestational weeks; (6) certain about their abortion decision and indicate the decision is of their free will; and (7) own a smartphone. Women will be excluded if they: (1) are presenting to FPRHC for post-abortion follow-up examination or secondary treatment of an incomplete abortion); (2) require an abortion for medical reasons; (3) are currently receiving mental or psychological treatment; or (4) unable to give informed consent (e.g., severe intellectual disability).

2.3. Interventions

A psychologist as well as clinic staff who provide direct care will be responsible for maintaining the quality of care and women’s safety. See Table 1 for a detailed description of the START intervention and standard abortion care according to the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) [23]. Generally, the START intervention involves three interacting components: (1) a 30-minute face-to-face consultation immediately after a woman’s enrolment; (2) information support including a printed booklet and an online information platform available to them from the consultation until closure of the project; and (3) timely communication channels with health providers (a hotline staffed between the hours of 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. and a WeChat-based public profile page) valid until 6 weeks post-abortion. Table 2 presents the specific content of the information booklet and platform.

Table 1.

Intervention description according to TIDieR checklist.

Table 2.

Content of the information booklet and platform.

2.4. Outcomes

2.4.1. Feasibility Outcomes

Feasibility outcomes include eligibility and intervention delivery data, which will be collect by a research logbook and participants’ completion of questionnaires. The specific outcomes are:

- Proportion of women who meet the eligibility criteria

- Proportion of eligible women who are recruited

- Proportion of recruited women who receive the allocated intervention to which they are randomized

- Withdrawal or loss to follow-up rate

- Missing data rate

2.4.2. Acceptability Outcomes

Acceptability refers to retrospective acceptability assessed after participating in the intervention. Phone calls will be made to all participants in the intervention group at the last follow-up. A questionnaire based on the TFA framework of Health Care Intervention [24] will guide the recorded phone interview. The questionnaire will include both closed- and open-ended questions representing all seven constructs of intervention acceptability: affective attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, and self-efficacy. Responses on closed-ended questions are on a Likert Scale from 1 to 5, and response labels vary depending on the item. For example, ‘to what extent was the intervention useful to you?’ has response options of 1 ‘not at all useful’ to 5 ‘extremely useful’. Responses to opened-ended questions will be noted and recorded. Examples of open-ended questions are ‘how do you feel about the intervention’, ‘which component of the intervention was most/least useful and why?’, and ‘did you encounter any barriers when participating in the intervention?’.

2.4.3. Effectiveness Outcomes

Effectiveness outcomes include women’s depression symptoms (primary), coping behaviours, self-efficacy, perceived support levels, intimate relationship satisfaction, post-abortion personal growth, and abortion-relevant outcomes. Specific measures include:

Depression

Changes in women’s depression symptoms will be measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [25]. The nine-item scale will be administered at the initial patient interview and monitor progress. Participants will be asked to rate the severity of their depressive symptoms on a four-point scale (0 = not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; and 3 = nearly every day). The nine items cover symptoms associated with experiencing pleasure, feeling down, and self-esteem. The total score can range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depression. The tool has been translated and validated with the Chinese population, showing strong psychometric properties (α = 0.86) [26].

Coping Behaviours

The Carver Brief COPE Inventory [27] will be used to measure changes in women’s coping behaviours. This 28-item inventory measures the use of 14 coping behaviours (2 items per strategy). Women are asked to rate how often they adopted each behaviour within the previous 2 weeks on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (I have not been doing this at all) to 3 (I have been doing this a lot). Coping behaviours are categorised into three dimensions: (1) problem-focused coping (four sub-scales: active coping, use of informational support, positive reframing, and planning); (2) emotion-focused coping (six sub-scales: emotional support, venting, humor, acceptance, religion, self-blame); and (3) dysfunctional-focused coping (four sub-scales: self-distraction, denial, substance use, and behavior disengagement). Brief COPE has been widely utilized in different populations, including women who experienced pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality [28]. The Chinese version of Brief COPE has shown adequate psychometric properties with a Cronbach’s alpha of <0.60 [29,30].

Self-Efficacy

The General Self-Efficacy scale (GSE-10) [31] has 10 items measuring optimistic self-beliefs to cope with difficulties in life. Items of GSE were scored on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (completely true). Scores range from 10–40 with higher total scores indicating that an individual feels more competent in dealing with stressful encounters. It is valid, reliable and has been translated into more than 30 languages, including Chinese [32]. The internal inconsistency of the Chinese version was 0.91 [32].

Perceived Social Support

The abbreviated version of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale (MOSSS-5) [33] and seven study-specific questions will be used to measure perceptions of support. The MOSSS-5 is a five-item reliable measure of perceived social support. Each item is scored on a five-point Likert scale and the items are summed for a total score ranging from 5−25. Its Chinese version has adequate test–retest reliability (0.89), and internal consistency items ask participants to rate their satisfaction, degree of happiness, feelings of reward, and comfort with their partners. Each question has different response formats. Total scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. The Cronbach’s α reliability of the translated version in Chinese women is 0.88 [34].

Post-Abortion Growth

The Post-traumatic Growth Inventory Short Form (PTGI-SF) evaluates personal growth following traumatic, challenging and stressful life circumstances [35]. PTGI-SF comprises 10 items rated on a six-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 5), with a total score ranging from 0 to 50. Higher scores indicated higher PTG. The 5 subscales include relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. The Chinese version has acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach α of 0.86 [36].

Abortion Related Outcomes

Abortion related outcomes will be measured according to women’s gestational weeks at abortion, type of abortion, complications, and follow-up-exam attendance.

2.5. Sample Size

A formal sample-size calculation is not necessary for research objectives 1 and 2 [20]. For objective 3, G*Power software was used to determine reasonable sample size for the estimation of differences between intervention and control groups. The effect size on depression reported by similar interventions ranged from 0.39 to 1.06 [37,38,39]. G*power indicated a total of 72 participants will be required to detect a 0.39 effect size for depression, two tailed, with alpha at 0.05 and power at 90%. Anticipating a 20% attrition rate, recruitment was set at 90 (45 women per group).

2.6. Recruitment and Consent

When women present at the FPRHC seeking an abortion, they receive a consultation to ensure informed choice and a medical appointment to assess their physical health. If the woman confirms her decision to terminate the pregnancy, she speaks with a nurse to make an appointment for the abortion. As reception nurses have an ongoing relationship with patients and are available during clinic hours, they will screen women based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If eligible, the reception nurse will provide a brief explanation about the study and ask women if they are interested in participating. If yes, women will be referred to the primary researcher, who will discuss the study in more depth, answer any questions, and provide the Participant Information and Consent Forms. The potential participant will be given adequate time to read the forms, talk with her support person, and ask questions before deciding to participate or decline. Participants will be assured they can withdraw from the study at any time, and it will not influence their treatment in any way.

2.7. Assignment and Blinding

Considering the small sample size, block randomization will be used to reduce bias and ensure an equal balance between the intervention and control groups [40]. A block size of four with six possible balanced combinations of assignment within the block is considered appropriate for this study. The nurse coordinator will generate a random number sequence using Microsoft Excel and place the assignments into sealed envelopes. After informed consent, the primary researcher will open a sequential envelope to determine the group allocation of each participant. Given the nature of the intervention, it is not feasible to blind the participants, intervention providers, and researchers who collect data. To prevent contamination, women in the intervention group will be asked not to share information or materials of the study with other abortion patients before completion of the study.

2.8. Data Collection

Data collection will occur at five timeframes: T-0, during recruitment before randomization; T-1, on abortion day before discharge (normally 2 h post-abortion procedure); T-2, during women’s post-abortion exam visit, normally 2 weeks post-abortion; T-3, 6 weeks post-abortion; and T-4, post completion of all follow-ups of all participants. See Table 3 for detailed information on data collection, including What, Who, When, Where, How, and by What data.

Table 3.

Data collection schedule and analysis method.

2.9. Data Analysis

Participant characteristics, feasibility outcomes, and quantitative acceptability outcome data will be summarized with descriptive statistics, including frequency counts and percentages (categorical variables) and mean with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or standard deviation (continuous variables). Intervention feasibility and acceptability will be assessed against the following criteria: eligibility: ≥60% of patients screened will be eligible; recruitment: ≥80% of eligible participants will agree to participate; protocol fidelity: ≥90% of patients randomized to each group will receive the allocated intervention; retention: <20% of patients will be lost at 6 weeks after abortion; and missing data: <20% of data will be missing. Between-group differences of participant characteristics, baseline data, and effectiveness outcomes will be detected using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS)® version 23 [41]. Specifically, Chi square tests will be used for categorical/dichotomous variables, and t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables (depending on normality). To capture changes in the effect outcomes over time, a general linear regression analysis will be performed. See Table 3 for the specific analysis approaches.

For qualitative data, audiotapes of telephone interviews will be transcribed and de-identified by the primary researcher. Transcripts and notes will be analyzed using the deductive approach of content analysis [42]. First, a structured analysis matrix will be developed based on the aims of the study and the TFA of Health Care Intervention. Then the primary researcher and nurse coordinator will independently review all de-identified data, and content fit the matrix. They will work together to group similar content within the matrix boundaries as categories, and then main categories. After abstraction of each category, the primary researcher and nurse coordinator will make a joint decision on how to model and report the results. Any discrepancies along the process will be discussed with a third reviewer until an agreement is reached. To preserve the original meaning of women’s statements, the data analysis process will be conducted using Chinese. Development of the analysis matrix and reporting process will use Chinese and English to reduce potential bias and build a shared vision among the research team.

2.10. Protocol Modifications

During the conduction of the trial, if we observe a higher-than-expected drop-out rate at the two-weeks post-abortion follow-up, we will increase the sample size from 90 (calculated on a 20% attrition rate) to 110 (calculated on a 35% attrition rate) to achieve precision for the estimation of the effect size. Paper-based questionnaires will be left for women to fill out on their own. However, if participants express being overwhelmed by the amount of information required, we will conduct an interview during which participants could ask clarifying questions. This approach will minimize missing data and enhance the retention rate.

3. Discussion

We propose a two-armed randomized trial among Chinese women undergoing abortion, to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and potential effects of the START intervention. To our knowledge, this study will be the first trial to address Chinese abortion patients’ psychological wellbeing by providing a comprehensive supportive intervention based on the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping [19]. This innovative intervention contains different active components that will be delivered using different methods. Findings from this trial will allow us to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, which will inform intervention refinement [17]. The findings will also help to identify potential barriers and facilitators for implementing the intervention in the Chinese context [43]. As the preliminary effectiveness and effect of the intervention will also be described, the study could have important implications for relevant policymakers, practitioners, researchers, or other stakeholders [44].

We are employing a rigorous study design to ensure the internal and external validity of findings. This trial responds to the call for well-designed, rigorously conducted scientific research in abortion care in developing countries [1]. Randomization and statistical analysis adjusted for any difference in baseline characteristics between groups will protect against selection bias, and ultimately warrant internal validity [45]. The study will be performed under real-world clinical practice conditions, which will enhance the external validity and generalizability of results. All instruments used in this study have been validated in the Chinese population, which will also enhance the reliability of findings.

A further strength is that we have adopted a series of appropriate guidelines to ensure the normalization, transparency, and replication of the study. The TIDieR checklist has been used to describe the intervention [23]. Application of the CONSORT statements [20,21] and the SPIRIT 2013 Checklist [22] have been followed.

Limitations, however, need to be considered. The emotional period between a woman’s initial appointment with the clinic and 6 weeks post-abortion [46], as well as the sensitive nature of the topic, could challenge women’s adherence and completion of the study. Strategies such as keeping information simple, offering the intervention in confidential formats, and repeated reminders that are known to be effective in improving intervention adherence will be employed [47]. Another challenge lies in the uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic. We will follow and document all local, national, and international measures that may impact our study progress. The actual delivery of the intervention and identified barriers and facilitators of implementing the intervention will be well-recorded to inform future studies.

4. Conclusions

This paper proposes a protocol of a clinical trial to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and potential effects of a comprehensive supportive intervention that was developed to address the psychological health of Chinese women undergoing an abortion. Results will be used to assist intervention refinement and direct a future full-powered trial. Practical experience will be gained throughout the clinical trial, which would also provide evidence for further implementation of the intervention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, N.W., J.G., J.A. and D.K.C.; validation, resources, and investigation, N.W. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, N.W.; writing—review and editing, N.W., J.G., J.A., E.E. and D.K.C.; visualization, N.W. and X.Z.; supervision, X.Z., J.G., J.A., E.E. and D.K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author is supported by a Griffith University International Postgraduate Research Scholarship. The sponsor has no involvement in making decisions on the design, conduction, or reporting of the trial.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Boards of Peking University People’s Hospital (2021PHB003-001), and the Human Research Ethics Committee of Griffith University (2021/410) respectively.

Informed Consent Statement

Written consent will be obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data involved in this study will be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the clinical workers involved in the study for their invaluable contribution to data collection and expert support. We also would like to thank all the participants in advance for being willing to participate in the research and sharing their experiences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

References

- Bearak, J.; Popinchalk, A.; Ganatra, B.; Moller, A.-B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Beavin, C.; Kwok, L.; Alkema, L. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: Estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1152–e1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO and UNICEF. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescent’s Health 2016–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 4–103. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Practice Handbook for Safe Abortion; WHO Library Cataloguing: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Induced Abortion and Mental Health: A Systematic Review of the Mental Health Outcomes of Induced Abortion, Including Their Prevalence and Associated Factors; Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, M.A.; Upadhyay, U.D.; McCulloch, C.E.; Foster, D.G. Women’s mental health and well-being 5 years after receiving or being denied an abortion: A prospective, longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocca, C.H.; Samari, G.; Foster, D.G.; Gould, H.; Kimport, K. Emotions and decision rightness over five years following an abortion: An examination of decision difficulty and abortion stigma. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 248, 112704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, R.; Stephenson, J.; Mann, S. What influences contraceptive behaviour in women who experience unintended pregnancy? A systematic review of qualitative research. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 34, 693–699. [Google Scholar]

- Barraza Illanes, P.; Calvo-Frances, F. Predictors of personal growth in induced abortion. Psicothema 2018, 30, 370–375. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Report of the Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion; Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. J. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wethington, E.; Glanz, K.; Schwartz, M.D. Stress, Coping, and Health Behavior. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.L.; Pan, P.E.; Wu, M.W.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, S.W.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.P.; Yu, X.Y. The experiences of nurses and midwives who provide surgical abortion care: A qualitative systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 103, 3644–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Allen, J.; Gamble, J.; Creedy, D.K. Nonpharmacological interventions to improve the psychological well-being of women accessing abortion services and their satisfaction with care: A systematic review. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commitee of China. China Healthcare Statistic Yearbook; China Medical University Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, N.; Hu, Y.; Creedy, D.K. Prevalence of stress and depression and associated factors among women seeking a first-trimester induced abortion in China: A cross-sectional study. Reprod Health 2022, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, A.; Blewitt, C.; Nolan, A.; Skouteris, H. Using Intervention Mapping for child development and wellbeing programs in early childhood education and care settings. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 68, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Zhu, X.; Elder, E.; Allen, J.; Creedy, D.; Gamble, J. Developing a theory-informed intervention for Chinese women undergo abortion using an intervention mapping approach: The STress-And-coping suppoRT (START) intervention. Midwifery, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Begg, C.; Cho, M.; Eastwood, S.; Horton, R.; Moher, D.; Olkin, I.; Pitkin, R.; Rennie, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Simel, D. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996, 276, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.-W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Altman, D.G.; Laupacis, A.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Krleža-Jerić, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Mann, H.; Dickersin, K.; Berlin, J.A. SPIRIT 2013 statement: Defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Löwe, B.; Kroenke, K.; Herzog, W.; Gräfe, K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: Sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 81, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. DSM-5 Severity Measure for Depression for Adult—Chinese Version 2021. Available online: https://www.mhealthu.com/index.php/list_liangbiao/120/267?page=3 (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: Consider the brief cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarge, C.; Mitchell, K.; Fox, P. Posttraumatic growth following pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: The predictive role of coping strategies and perinatal grief. Anxiety Stress Coping 2017, 30, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, F.W. Relationships between menopausal symptoms, sense of coherence, coping strategies, and quality of life. Menopause 2019, 26, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Hu, D.; Liu, Y.; Lu, C.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lopez, V.; Mao, J. Coping styles and social support among depressed Chinese family caregivers of patients with esophageal cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherer, M.; Maddux, J.E.; Mercandante, B.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Jacobs, B.; Rogers, R.W. The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychol. Rep. 1982, 51, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Schwarzer, R. Measuring optimistic self-beliefs: A Chinese adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Psychol. Int. J. Psychol. Orient 1995, 38, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Nguyen, L.; Anderson, J.R.; Liu, W.; Vennum, A. Pathways to romantic relationship success among Chinese young adult couples: Contributions of family dysfunction, mental health problems, and negative couple interaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2015, 32, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Taku, K.; Vishnevsky, T.; Triplett, K.N.; Danhauer, S.C. A short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Qi, W.; Yu, L. Relationships between family resilience and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors and caregiver burden. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnasiri, H.; Behbodimoghddam, Z.; Ghasemzadeh, S.; Ranjkesh, F.; Geranmayeh, M. The study of the consultation effect on depression and anxiety after legal abortion. Iran. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2016, 4, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Khodakarami, B.; Mafakheri, B.; Shobeiri, F.; Soltanian, A.; Mohagheghi, H. The Effect of Fordyce Happiness Cognitive-Behavioral Counseling on the Anxiety and Depression of Women with Spontaneous Abortion. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2017, 9, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar]

- Moshki, M.; Baloochi Beydokhti, T.; Cheravi, K. The effect of educational intervention on prevention of postpartum depression: An application of health locus of control. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 2256–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efird, J. Blocked randomization with randomly selected block sizes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Hoddinott, P.; Lewin, S.; Thomas, K.; Young, B.; Adamson, J.; Jansen, Y.; Mills, N.; Moore, G.; Donovan, J. Maximising the impact of qualitative research in feasibility studies for randomised controlled trials: Guidance for researchers. Trials 2015, 16, O88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C.; et al. How We Design Feasibility Studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slack, M.K.; Draugalis, J.R., Jr. Establishing the internal and external validity of experimental studies. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2001, 58, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rocca, C.H.; Kimport, K.; Gould, H.; Foster, D.G. Women’s emotions one week after receiving or being denied an abortion in the United States. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2013, 45, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Action; Center for Effective. A review of behavioral economics in reproductive health. In CEGA White Papers; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 4–43. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).