Abstract

(1) Background: Training load monitoring has become a relevant research-practice gap to control training and match demands in team sports. However, there are no systematic reviews about accumulated training and match load in football. (2) Methods: Following the preferred reporting item for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA), a systematic search of relevant English-language articles was performed from earliest record to March 2020. The search included descriptors relevant to football, training load, and periodization. (3) Results: The literature search returned 7972 articles (WoS = 1204; Pub-Med = 869, SCOPUS = 5083, and SportDiscus = 816). After screening, 36 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed. Eleven of the included articles analyzed weekly training load distribution; fourteen, the weekly training load and match load distribution; and eleven were about internal and external load relationships during training. The reviewed articles were based on short-telemetry systems (n = 12), global positioning tracking systems (n = 25), local position measurement systems (n = 3), and multiple-camera systems (n = 3). External load measures were quantified with distance and covered distance in different speed zones (n = 27), acceleration and deceleration (n = 13) thresholds, accelerometer metrics (n = 11), metabolic power output (n = 4), and ratios/scores (n = 6). Additionally, the internal load measures were reported with perceived exertion (n = 16); heart-rate-based measures were reported in twelve studies (n = 12). (4) Conclusions: The weekly microcycle presented a high loading variation and a limited variation across a competitive season. The magnitude of loading variation seems to be influenced by the type of week, player’s starting status, playing positions, age group, training mode and contextual variables. The literature has focused mainly on professional men; future research should be on the youth and female accumulated training/match load monitoring.

1. Introduction

Football is a team sport characterized by intermittent efforts, combining high-speeds and intensity with low-intensity periods [1,2]. Knowing about the match physical and physiological demands allows to carry out the training mode [3]. The training process requires a systematic and periodized application to ensure optimal adaptations to physiological responses and biochemical stresses [4,5]. Researchers and practitioners aim to promote favorable performance outcomes and an adequate recovery for match demands [5]. Football training programs may improve aerobic and anaerobic fitness; these adaptations should be monitored and controlled periodically [6]. The training load has been defined as an input variable for training outcomes, allowing to control training session demands in real time and after each training sessions [7]. The training load can be split up into external (physical) and internal (physiological) load, providing insights about dose-response [6,7]. The external load is defined as the performed work during training sessions or competition, regardless of the internal characteristics. The external load can be monitored by global positioning systems (GPS) tracking systems [8], micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) [9], local position measurement (LPM), and computerized-video systems [10]. Commonly, external load measures are power output, distances, speeds, accelerations/decelerations, time-motion analysis, and neuromuscular function [5,11]. The internal load refers to physiological and psychological stress and is possible to assess by objective and subjective instruments [5,7]. The most commonly used objective measures are the physiological, such as heart rate, lactate, or oxygen consumption; and training impulse (TRIMP). Moreover, subjective measures usually include ratings of perceived exertion, wellness questionnaires, and psychological inventories [5,12].

The training effects depend on physiological stimulus by intensity, duration, frequency, and recovery periods [6,13]. The external load provides training quality, quantity, and organization; quantifying their components allows an overview of training prescription [4,14]. The physiological adaptations have been well documented [1,2]. However, there is no unique physiological marker that can be used to assess the fitness-fatigue binomial to predict performance [12]. Combining internal and external load data can be used as an approach to overcome the conceptual barrier concerning the fitness-fatigue binomial [15]. However, there is no consensus of an effectiveness monitoring system in professional football [16]. The training load quantification in team sports is often mentioned as a great challenge. This may be due to the difficulty of accurately assessing the skilled performance and cognitive load that influences decision-making [17]. Furthermore, the diversity of monitoring tools appears to have created confusion in dose-response considerations. Indeed, turning these data into relevant information has become a significant challenge to coaches and sport scientists [18].

Currently, a growing number of articles have been published on training load. Recent reviews and meta-analysis focused on team sports aimed to evaluate the association between loading and performance [19,20], intensity [21], training outcomes [22], acute/residual fatigue [23,24], and injury, illness, and soreness [24]. The use of micro-technology to collect and interpret training load has been largely revised in team sports [25,26] and particularly in professional football [27]. Youth football has also been revised with the objective of match running performance [28] and injury incidence [29]. The match running performance has been widely described considering playing position, formation, and opposition standard [30,31,32,33]. However, there have been no previously published systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses about monitoring accumulated training and match load [24]. The match-play represents the greatest physiological stimulus and represents the primary performance outcome [32]. Nonetheless, nearly 80% of the weekly training load results from the training sessions whereas about 20% is from the match-play [1,34]. Understanding the cumulative effect of training is essential to guide the individual athlete’s performance [3,5].

Cumulative effect is a primary factor for the long-term training process and athletic preparation [35]. Training load monitoring plays an important role in training periodization and evaluating cumulative effects variation is essential to an effective training planning according to the individualization principle [36]. Previous research has focused on match load [37] or quantifying training load in specific training moments and highly controlled situations using constrained tasks [38,39]. Monitoring gross and temporal demands during training sessions may help to improve ecological validity. Even more, it may allow to supply an accurate understanding about the inclusion of training load measures in training practices and match management [15,35]. However, there is a lack of consensus on the most effective strategies and training load metrics to measure accumulative training and match demands [16]. Additionally, the different methodologies could lead to outcome differences and bias in the loading analysis [40]. Understanding the seasonal training/match load variations and the relationships between measures would appear important to define the most appropriate monitoring strategy. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was three-fold; (1) to analyze intra and inter-individual accumulative training load distribution within a week (microcycle), weeks (mesocycle), and/or season phases; (2) to analyze the intra and inter-individual accumulative training and match load distribution within a week (microcycle), weeks (mesocycle), and/or season phases; and (3) to analyze relationships between internal and external load measures in the accumulative training load quantification.

2. Materials and Methods

The present systematic review protocol was registered at the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols with the number 202080095 and doi:10.37766/inplasy2020.8.0095.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the population-intervention-comparators-outcomes (PICOS) design were followed to conduct this systematic review [41,42]. The literature search was based on four databases: PubMed/Medline, Web of Science (WoS, including all Web of Science Core Collection: Citation Indexes), SCOPUS, and SportsDiscus. The eligibility criteria were assured by a PICOS approach and the following search strategy was defined: (1) population: adult and youth football players (participants aged < 13 years); (2) intervention: quantify and compare external (physical) and internal (physiological) load during at least a 1-week period (microcycle); (3) comparison: periodization structure (microcycle, mesocycle, and/or season phase); (4) outcomes: intra- and inter-individual accumulative load distribution; and (5) study design: experimental and quasi-experimental trials (e.g., randomized controlled trial, cohort studies, or cross-sectional studies).

According to the search strategy, studies from January 1980 to March 2020 were included for relevant publications using keywords presented in Table 1. In addition, the keywords were searched with a Boolean phrase (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search terms and following keywords for screening procedures.

The literature search was accessed during February and March 2020. The search strategy was independently conducted by one review author and checked by a second author. Discrepancies between the authors in the study selection were solved with support of a third reviewer. The authors did not prioritize authors or journals.

2.2. Selection Criteria

The included studies in the present review followed these inclusion criteria: (1) training load monitoring studies with adult and youth football players of both sexes; (2) studies with screening procedures based on internal and/or external load measures; (3) only studies that included the training load quantification of gross and temporal demands in complete/full training sessions (with or without match-play load); (4) observational prospective cohort, case-control, and/or cross sectorial design study including at least one week of monitoring; (5) studies of human physical and physiological performance in Sport Science and as scope; (6) original article published in a peer-review journal; (7) full text available in English; and (8) article reported sample and screening procedures (e.g., data collection, study design, instruments, and the outcomes).

The exclusion criteria were: (1) training load-based studies from team sport or football code population (e.g., Australian Football, Gaelic Football, Union, and/or Seven Rugby); (2) studies that monitored only match-play load; (3) participants aged < 13 years and a match format other than 11-a-side football; (4) studies with screening procedures focused on biochemical loading, well-being, and/or injury intervention protocols; (5) studies that included the training load quantification based on field based test and laboratory test; (6) studies that included less than a week of monitoring and experimental trials or study cohort intervention with control group (pre- and post-) to evaluate the effect of a specific training method/program (e.g., small sided games, high intensity interval training, simulated games, or individualized approach); (7) others research areas and non-human participants; (8) articles with bad quality in the description of study sample and screening procedures (e.g., data collection, study design, instruments, and the measures) according to the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement; and (9) reviews, abstract/papers conference, surveys, opinion pieces, commentaries, books, periodicals, editorials, case studies, non-peer-reviewed text, or Master’s and/or doctoral thesis.

The search was limited to original articles published online until December 2020. Duplicated articles were identified and eliminated prior to application of the selection criteria (inclusion and exclusion). Titles and abstracts were initially selected and excluded according to selection criteria. The selection of full texts was based on a selection to determine the final status: inclusion or exclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between two authors, or via a third researcher if required. Secondary-sourced articles considered relevant and with the same screening procedures were added.

2.3. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality was assessed using STROBE statement by two authors [43,44]. This checklist was used in previous reviews due their accuracy in the reporting of observational studies’ cohorts, case-control, and cross-sectional studies [45,46]. The studies were classified as high-quality when missing fewer than three criteria of the STROBE checklist, while low-quality studies were defined as studies missing three or more criteria [45]. It included 22 items: title of the article and abstract interlinked (item 1), introduction (items 2 and 3), methods (items 4 to 12), results (items 13 to 17), discussion (items 18 to 21), and any other information (item 22). Four items were specific to the study design: participants (item 6), variables (item 12), descriptive data (item 14), and outcome data (item 15). The quality assessment was based on the attribution of one point for each checklist item if the criteria were evaluated as being complete (1 point), partial (0.5 points), or incomplete (0 points). The sum of the total points counted was divided by the maximum possible (22 items). Each author performed the classification independently with subsequent inter-observer reliability analysis:Kappa index (0.93; 90%) and confidence interval (CI): 0.92–0.95).

2.4. Study Coding and Data Extraction

The data extractions from the included articles were performed according to: (1) summary measures describing construct, measure, measurement, thresholds, and/or metric formula with included article reference and further reading (Table 2); (2) subject and study characteristics according publication date, study design, completive level and standard, sample (N), and sex and anthropometric characteristics (stature and body mass) (Table 3); (3) methodological approaches: observations sample (monitoring period, training sessions recorded, trainings/week, training mode, and number of match-play), training load measures/metrics (internal and external load), and device specification (manufacturer model) (Table 4); (4) main findings: study purpose, periodization design, independent variables, findings, practical applications, and future directions. Data reporting were extracted according study purpose, periodization structure, independent variable, findings, and practical applications.

Table 2.

Summary of measure and measurements in the included articles.

The outcome measures and the statistical procedures used in the included references were inconsistent between studies, making it impossible to group data and perform the meta-analysis. Characterization of participants is reported as mean ± standard deviation, CI, and effect size (ES) wherever possible. In order to clarify the variety of internal and external load measures used in the included studies, Table 2 consolidates the thresholds used by the authors to calculate metric formulas. In addition, the references correspond to the article reviewed and their construct, measure, and methods. The further reading includes the original references used by the reviewed studies to ensure the methodological procedures.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

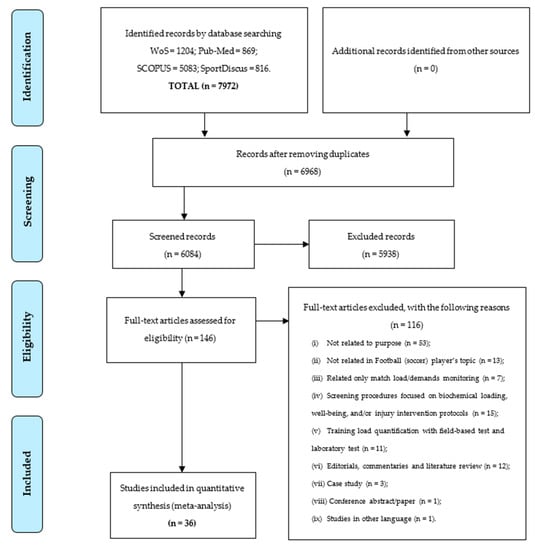

A total of 7972 titles were collected through four database searches (WoS = 1204; Pub-Med = 869; SCOPUS = 5083; and SportDiscus = 816). No articles were identified from additional sources as a potentially relevant and unidentified research strategy. A total of 188 duplicate records were removed, and 884 articles were removed based on the title and abstract according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 146 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 116 were removed. The reasons for exclusion were: (1) studies not related systematic review purpose (n = 53); (2) studies not related to football player’s topic (n = 13); (3) studies related only to match load/demands (n = 7); (4) studies with screening procedures based on biochemical loading, well-being, and/or injury intervention protocols (n = 15); (5) studies that included field-based test and laboratory test for training load quantification (n = 11); (6) editorials, commentaries, and literature reviews (n = 12); (7) case studies (n = 3); (8) conference abstract/papers (n = 1); and (9) other language (n = 1). After screening procedures, 36 articles were included in the present systematic review. A detailed representation of the screening procedures is depicted with a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting item for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

3.2. Participant Characteristics

The reviewed articles were published between 2004–2020. All included articles presented a quasi-experimental approach based on observational and prospective cohort design. The included studies were performed in elite/professional (n = 32), pre-elite (n = 3), and amateur (n = 1) football. One article did not specify the participants’ competitive level. Twenty-seven articles focused on adult player population and nine on youths. The geographic location of the populations studied in reviewed studies were Australia (n = 1), Brazil (n = 1), France (n = 3), Italy (n = 1), Korea (n = 1), Norway (n = 2), Portugal (n = 6), Spain (n = 5), Swiss (n = 1), The Netherlands (n = 3), and the United Kingdom (n = 11). Four studies did not specify the geographic location and one study was sampled in an European population.

The study samples ranged between 13–160 participants. All articles were performed on male football players, except one on female players. A total of 1317 (1302 men and 15 women) adult and youth football players were analyzed for this systematic review. The mean and standard deviation for age and anthropometric data (weight and height) in the included studies was 22.71 ± 4.37 years, 74.13 ± 6.77 kg, and 1.71 ± 0.05 m, respectively. Table 3 provides a summary of the participants demographics.

Table 3.

Summary characteristics of the participants’ demographics recruited in the studies included in the systematic review and its quality score.

3.3. Quality Assessment

In the evaluation of methodological quality, the mean quality score and standard deviation of all the included studies was 0.79 ± 0.06 (Table 3). One study (3.33%) was classified with a quality score of 0.65. Twenty studies (56.67%) were classified between 0.7 and 0.8, whereas fifteen studies (40.00%) had a quality score between 0.8 and 0.9. None of the reviewed studies had the maximum score (1.0) or below 0.5 (min: 0.65; max: 0.89).

3.4. Data Organization

The results are presented in the following three sub topics: (1) analysis of the intra- and inter-individual accumulative training load distribution within one week (microcycle), weeks (mesocycle), and/or season phases; (2) analysis of the intra- and inter-individual accumulative training load and match load distribution within one week (microcycle), weeks (mesocycle), and/or season phases; and (3) analysis of the relationships between internal and external load measures in the accumulative training load quantification. Observation samples were collected from 17 to 2981 training sessions and varied between 3 and 6 trainings per week. Twenty studies analyzed training data and ten articles integrate training data with match load. The monitoring period in the included studies ranged from 3 to 43 weeks. The included match-play varied from 1 to 623 games. Four studies did not describe the number of observed weeks and six studies did not describe training sessions. Eleven articles evaluated training load with internal load measures; fourteen articles included only external load measures; and eleven studies analyzed internal and external measures.

The training load quantification in the included studies were based on internal and external load measures/metrics. Twelve articles analyzed only internal load measures, twelve articles evaluated the external load, and twelve studies assessed both measures. The studies that quantified only internal load were based on summated zones of maximum heart rate (HRmax) (n = 10), and training impulse (n = 11). Banister TRIMP was reported in four studies, Edwards TRIMP in five studies, and lactate threshold (LTzone) and modified Stagno training impulse (TRIMPMOD) were both required in one study. Still, external load measures were quantified with distance and covered distance in different speed zones (n = 27), acceleration and deceleration (ACC/DEC) (n = 13), accelerometer metrics (n = 11), metabolic power output (n = 4), and ratios/scores (n = 6).

The methodological approaches of the reviewed articles were based on short-telemetry systems (n = 12), GPS systems (n = 25), MEMS (n = 18), LPM systems (n = 3), and multiple-camera systems (i.e., Prozone®, Leeds, UK) (n = 3). Additionally, the internal load measures were reported with perceived exertion scales (i.e., Borg’s Category-Ratio scale, Hooper Index, and Fatigue Questionnaire) (n = 16). The internal load based on heart rate (HR) measures were reported in twelve of the included studies (n = 12); with 1 Hz telemetry system and five studies with 5 Hz. Two studies did not specify the telemetry range in the methodology description. Furthermore, internal load based on perceived exertion by Borg’s Category-Ratio scale was presented in fifteen studies. One study assessed perceived exertion with the Hooper Index and one other with the Fatigue Questionnaire. Regarding systems tracking, 5 Hz GPS, 10 Hz GPS, and 15 Hz GPS were used in one study, fifteen studies, and four studies, respectively. The 100 Hz MEMS integrated the GPS device and was reported in ten studies. The LPM system was reported only in one study.

The data organization respected the three main purposes of this systematic review. Table 4 presents the methodological approaches selected by the studies included in this review.

Table 4.

Methodological approaches of included articles.

3.5. Weekly Training Load Distribution Analysis

Eleven reviewed articles analyzed weekly training load distribution. Two articles included only internal load measures, two articles evaluate only external load, and six studies analyzed both training load measures. Regarding periodization structure, seven studies analyzed weekly microcycle (1-game week), four studies quantified training load over mesocycles (week-block), and three articles included the training load quantification across different seasonal phases. One article did not specify the periodization structure for its analysis. Observations samples were collected from 27 to 2591 training sessions and varied from 4 to 6 training sessions per week. The monitoring period in the included studies ranged between 7 and 42 weeks. The included match-play ranged from 1 to 612 games.

The independent variables in the weekly training distribution analysis were age (n = 3), training day (n = 7), mesocycle structure (n = 3), training mode/type or sub-components (n = 1), playing position (n = 5), and contextual variables (n = 2). Table 5 provides the studies predominantly with a focus on weekly training load distribution analysis.

Table 5.

Studies with predominantly focus on weekly training load distribution analysis.

3.6. Weekly Training Load and Match Load Distribution Analysis

Fourteen articles analyzed the weekly training load distribution. Six articles assessed external load, two articles analyzed internal load measures, and two studies assessed both training load measures. Regarding the periodization structure, five studies evaluated the weekly microcycle (1-game week), two studies analyzed three different weekly microcycles (1-, 2- and 3-game week), and three studies quantified training load by mesocycles (week-block). Any article included in this systematic review analyzed weekly training load and match load distribution across different seasonal phases. Observation samples were collected from 10 to 2981 training sessions and varied from 4 to 7 training sessions per week. The monitoring period in the included studies ranged from 3 and 55 weeks. The included match-play varied between 3 to 55 games.

The independent variables applied in weekly training load and match load distribution analysis were age of players (n = 1), training day (n = 2), weekly microcycle type (n = 3), mesocycle structure (n = 3), player’s starting status (starters or non-starters) (n = 3), training mode/type or sub-components (n = 1), and playing position (n = 2). Table 6 provides the studies predominantly focusing on weekly training/match load distribution analysis.

Table 6.

Studies with predominant focus on weekly training load and match load distribution analysis.

3.7. Relationships between Weekly Internal and External Load

Eleven articles evaluated internal and external load relationships during training load quantification. Of these, five articles evaluated internal load relationships, five articles compared external load measures, and one study assessed the relationship between internal and external load. Four studies analyzed a weekly microcycle (1-game week) structure, and six articles did not specify the periodization structure. Observation samples were collected from 24 to 1029 training sessions and varied between 2 and 5 training sessions per week. The monitoring period in the included studies went from 9 to 43 weeks. The included match-play varied from 1 and 623 games.

All the eleven included articles in this sub-topic focused on comparison of internal and external load measures during training session. No other has analyzed the internal and external load relationships during match load. The independent variables applied in weekly training load distribution analysis were training day (n = 2), mesocycle structure (n = 1), training mode/type or sub-components (n = 2), playing position (n = 2), and training load indicators (n = 3). Table 7 provides the studies predominantly focusing on relationships between internal and external load during weekly training load.

Table 7.

Studies with predominant focus on the relationships between internal and external load.

4. Discussion

The present systematic review focused on three purposes: (1) analyzing intra- and inter-individual accumulative training load distribution within week (microcycle), weeks (mesocycle) and/or season phases; (2) analyzing the intra- and inter-individual accumulative training load and match load distribution within one week (microcycle), weeks (mesocycle), and/or season phases; and (3) analyzing relationships between internal and external load measures in the accumulative training load quantification.

The findings from the reviewed studies were organized into weekly training load distribution analysis, weekly training and match load distribution analysis, and relationships between weekly internal and external distribution. Therefore, the present discussion was conducted following the independent variables of age group, match contextual factors, periodization structures (i.e., microcycles, mesocycles, and/or season phases), playing positions, training mode or sub-components, week schedule format (i.e., 1-, 2- and 3-game week), player’s starting status, playing positions, and training load indicators. This systematic review ensures a general overview about monitoring daily and accumulated load. The main results demonstrated that the weekly microcycle presented a high load variation and a limited variation along season phases. Both were influenced by the type of week, player’s starting status, playing positions, age group, training mode, and contextual factors.

4.1. Weekly Training Load Distribution Analysis

The distribution of daily and accumulated load during a weekly microcycle (1-game week) was specified by seven included studies. Of these studies, six studies employed the format «match-day (MD) minus format» (i.e., MD- and/or MD+) and one study subdivided the week into post-match (session after the match), pre-match (session before the match), and mid-week (remaining training sessions). The accumulated training load showed a non-perfect load pattern within weekly microcycle. On that, the literature reported the greatest intensity and volume mid-week. However, there is no consensus among reviewed studies about the training day with highest values for high-intensity movements. On the other hand, a small seasonal load variation was reported with a non-significant higher accumulated weekly physiological load during pre-season. The influence of match-related contextual variables was clearly evidenced, which requires a more individualized approach. The training mode and age-related influence should also be considered for weekly training load distribution.

Clemente et al. [88] noted an intra-week load variance. Clemente et al. [89] reported that the highest load occurred over the MD+2, MD-5, MD-4, and MD-3. The lowest load was found on the MD+1, MD-2, and MD-1. The daily and accumulated load were significantly reduced on the MD-1, with no significant differences observed in other days [56]. Oliveira et al. [72] noted conflicting findings to daily internal and external load. The external loads were similar until MD-1 while the internal load did not present the same pattern. In the same line, MD+1 provided the highest average speed and high-speed running (HSR). Contrarily, MD+1 showed the lowest session rating of perceived exertion (sRPE) score. Malone et al. [56] showed the greatest intensity and covered distances performed on the MD-5 and MD-3. Oliveira et al. [72] presented a non-perfect load pattern by decreasing values until MD-1: MD-5 > MD-4 < MD-3 > MD-2 > MD-1. It was clear that MD-5 and MD-2 provided highest high-intensity [48]. In another study, the highest values were reported on MD-3 relative to the other days (MD-4, MD-2, MD-1) [99]. As well as that, a large weekly variation was found for the same type of day. That may exceed the recommendations to progressively load increase (between 5 and 15%) [91]. Regardless of the stage of development, Coutinho et al. [48] also observed an unloading on the MD-1. Conversely, the weekly training load distribution in the other age groups was different. The U19 showed high values of high-intensity activity in mid-week and pre-match. Moreover, U15 experienced residual weekly training load variations. The weekly external load distribution differs when comparing two teams from different countries [89]. According to Clemente et al. [89], the Portuguese team had a greater training volume on MD-2 and the Dutch team on MD-1. In the same study, significant differences were not found on MD-5 and MD-4 between teams. In the same study, the number of sprints covered during training sessions were different. The Portuguese team completed more sprints on MD-5, MD-3, and MD-2, whereas the Dutch team on MD-5.

The mesocycle or week block was explained in four studies. Brito et al. [69] divided the monitoring of the seasonal training load into four different phases (preparation I, competition I, preparation II, and competition II). Loading variation was reported across the season to sRPE and weekly training load, 5–72% and 4–48%, respectively. The highest sRPE values were observed during match-play, especially the last phase of the season (i.e., competition II). By contrast, fatigue scores did not detect differences along the competitive season. The variation of individual fatigue scores was only reported within the weekly microcycle. As well as that, Oliveira et al. [72] showed similar outcomes with Hooper Index scores across ten mesocycles and within their respective weekly microcycles. In addition, a small seasonal load variation was reported even if there were no significant differences between mesocycles. Clemente et al. [88] reported a small increase in load through descriptive statistics. Owen et al. [99] analyzed seasonal loading using a mesocycle structure (6 × 1-week blocks). No significant variations have been found along mesocycles differing from the weekly microcycle training load variation.

Two studies of this review examined the weekly training load distribution comparing pre-season versus in-season [55,56]. One study focused their analysis in the intra-week variations isolating pre-season and comparing two professional teams. The main findings and conclusions of these three studies were consistent with the studies that opted for the mesocycle structures [56,69,72]. Nonetheless, the study by Malone et al. [56] reported an additional in-season variation to covered distance and higher HRmax values during the beginning of the in-season than at the midpoint and endpoint. Jeong et al. [55] noted a higher accumulated weekly physiological load during pre-season when compared to in-season.

The inter-positional variation was examined in five reviewed studies with predominantly weekly training load distribution. Akenhead et al. [53] showed that only total covered distances and ACC/DEC were able to differentiate playing positions. Conversely, HSR and sprinting showed no positional differences. The central midfielders (CM) covered more distance at low and moderate acceleration thresholds than central defenders (CD). Indeed, when expressed in relation to distance covered, the wide defenders (WD) displayed a higher ACC/DEC density than CM. In Malone et al. [56], the CM and WD presented highest and CD the lowest values to total covered distance. Oliveira et al. [72] reported no significant changes for playing positions across the mesocycles analyzed. CM covered highest total distances than other playing positions. However, the authors did not find statistical significance. Moreover, the covered distance at high-intensity threshold proved that the interposition difference only took place in the first microcycle when comparing CD versus WD and WD versus wide midfielder (WM). This suggests that WD and WM have a higher high-intensity training profile. On the other hand, Owen et al. [99] documented significant differences within playing positions, especially before the match-play. CD showed lower covered distance values in comparison to CM and WM. It should be noted that the CM presents the highest covered distance at low intensity. The WD exhibited lower velocities and perceived exertion than CM and WM. The CD covered lower total distances and sprints while the opposite was pointed to WM. The analyses set out by authors revealed a limited positional variation across weekly training load. Oliveira et al. [72] provided a limited positional variation. Indeed, differences were found within-macrocycle whereas the load remained similar at the days of weekly microcycle, with the exception of MD-1.

Two included studies analyzed the time-motion and physiological profile by young football players using training data [47,48]. Coutinho et al. [48] described the age group pattern load over a typical week. Abade et al. [47] presented the overall loading without specifying any periodization structure. There were similar findings in both studies, reporting differences in the physical and physiological demands during training sessions. The under-15 (U15) training sessions had the most regular activity with less physiological demands [47,48]. The under-17 (U17) displayed the highest physical and physiological stimulus and under-19 (U19) had the highest high-intensity activity [48].

The influence of match-related contextual variables was mentioned in two studies [69,108]. Brito et al. [69] noted that the internal load of young football players was affected by contextual factors (i.e., result of previous match, the opponent’s level, and the location of the previous and following marches). According to the authors, the highest accumulated training load occurred during the training sessions after losing or drawing. By contrast, the lower loading was found before and after a match-play with a top-level opponent. After playing an away match-play, weekly training loads were higher than for a home match-play. Nonetheless, Owen et al. [108] did not report significant findings to confirm that contextual factors have an influence although the descriptive data point to a decrease in the training load after a win and away match-play. These findings are consistent with the need for a more individualized approach to initial preparation and subsequent match conditions [119,120]. Previous studies emphasize the importance of considering the independent and interactive effects of match-related contextual factor to the physical component of football performance [121,122].

The influence of the training mode, type, or sub-components were assessed in one study by weekly training load analysis. The training intensity presented associations with technical/tactical specifics and cool-down training sessions during the pre-season [55]. The contextual factors influenced the weekly training load distribution [61]. According to Rago et al. [61], the weekly TL seemed to be slightly affected by match-related contextual variables.

4.2. Weekly Training Load and Match Load Distribution Analysis

Two different periodization structures were explained in the studies with predominantly training and match load analysis. The weekly microcycle was reported in six studies and mesocycle (or week-blocks) were used by four authors. In this scope, the studies that included the match load also appear to show differences in the loading distribution, especially in the middle of week (i.e., MD-5, MD-4, and MD3). Limited load variation between the mesocycles were also reported. Furthermore, the type of weekly microcycle (i.e., one-, two-, and three-game week) appears to decidedly influence in the loading distribution. Additionally, the compensatory session was more intense than the recovery session. The match-related contextual factors, playing position, player’s starting status, age-related influence, and training mode should also be considered for weekly training load and match load distribution analysis.

Kelly et al. [70] showed a total distance and sRPE decreased in the MD-3. The high-intensity movements (HSR and sprinting) were higher in MD-3 and MD-2 than MD-1. Another study presented a progressive increase in perceived load until mid-week (i.e., MD-3) and subsequent decrease until MD-1 [68]. Martin-Garcia et al. [82] reported that the overall external load decreased progressively before match-play, especially in the MD-2 and MD-1. In agreement with the based-volume metrics, a reduced load raised in the MD-1 and MD-2 compared to MD-5, MD-3, and MD-4. Owen et al. [99] reported a significantly higher percentage for ACC/DEC values during MD-4, MD-2, and MD-1. Using a multi-modal approach, this study suggests that these metrics may provide higher levels (21% to 48%) when compared to explosive movements (2% to 11%). The compensatory session was more intense than the recovery session [79]. Similarly, Owen et al. [99] demonstrated that the MD-4 and MD-3 were the highest intensity and volume within the weekly microcycle, revealing a weekly highest load closer to MD. Anderson et al. [87] and Sanchez-Sanchez et al. [91] verified the greatest load in MD-3 and MD-2, respectively. The MD-1 was the lowest load in various studies whereas Owen et al. [99] presented a higher ACC/DEC in MD-1 than MD-2. At amateur level, the MD+1 and MD-1 were less loading [91]. The observed main findings seemed to have been converging in a strategy tapering based on a gradual reduction until the last day before MD.

During the competition period, the studies with training and match data seem to indicate a limited load variation between the mesocycles; similar with within playing positions. In contrast, the weekly microcycle presented the reported fluctuations in the external and internal load, which was further influenced by the playing position. Kelly et al. [70] described a slight increase in the beginning of the in-season and a small decrease along season. The total distance and sRPE was greater at the beginning of the in-season. The weekly accumulated load varied during MD-3 and MD-4 (40%), depending on the selected training load measure and playing positions. HSR and sprinting were the metrics that presented the greatest variability within the weekly microcycle (0.80%) [82]. The mid-season also showed a reduction in training volume [70]. On the other hand, the training time and typical weekly training load did not differ within microcycles in amateur football [91]. Wrigley et al. [60] also established that stage of development could influence variations within the weekly microcycle. These findings were similar to those verified in studies without match load [47,48].

The different type of weekly microcycle was analyzed in two reviewed studies [87,95]. Anderson et al. [87] quantified the training and match load during a one-, two-, and three-game week schedule. Clemente et al. [95] describe weekly training load variation in week with five, four, and three training sessions. A daily and accumulated load differed with the type of week schedule [87]. Clemente et al. [95] verified that the typical training intensity in the one- and two-game week schedules were compatible. However, the same did not occur in the three-game week. Therefore, the total accumulative load was lower in the one-game week schedule in comparison with the two- and three-game week schedules. Clemente et al. [95] verified that the accumulated total distances and number of ACC/DEC were three to four times higher than average match demands. The HSR and sprinting were one to two times greater than match demands. This kind of relationship between training and match load (scores/ratios) were studied in two studies included in this systematic review [95,108]. The training/match ratios varied ~2 to 4 arbitrary units (AU) considering external load. These proportions were dependent on the numbers of training sessions per week and that may infer an independence between weekly training load and match demands. The specific multi-modal approach suggested a significant variation in the volume and intensity scores across microcycles [99]. The variability match-to-match was ~16–31% (i.e., HSR and sprinting). Subsequently, it is possible to ensure that these external metrics revealed a greater sensitivity regarding contextual factors and type of week. The microcycle format may improve insights on how to appropriately implement periodization during fixture congestion [18,123]. Indeed, the studies with training and match data also demonstrated a limitation of the accumulated load between playing positions during the season [70,71]. Assessing the load patterns during the weekly microcycle may provide a most accurate positional load comparison [70].

The effect of player’s starting status was explored in five studies of this review. Anderson et al. [106] verified a significant effect of player’s starting playing in the total distance and high-intensity activity. Generally, starters covered more running, HSR, and sprinting distances than fringes and non-starters. Similarly, large to very large differences occurred in the perceived exertion within starters and non-starters [71,97]. The competition time was the main source to these variances [71,106]. The pre-season and winter-break seemed to have the highest variability across playing position [71,105]. Given the consistent these findings, it is reasonable to argue that the starting status could affect physical and physiological profiles [106]. The implementation of complementary training can be a strategy to reduce variance on the non-starting status. Stevens et al. [83] described that training to non-starters was generally higher than regular training sessions. Martin-Garcia et al. [82] verified that the compensatory session may produce the greatest ACC/DEC value within the weekly microcycle. Another interest finding in this study was the marked difference in training load at MD+1 between players completing the majority of the match-load (>60 min) versus players with partial or no playing time (<60 min).

One study aimed to quantify typical weekly training load and their content match load by under-14 (U14), under-16 (16), and under-18 (U18) football players [60]. The results proved that the training intensity and volume increased with age. Additionally, there were significant differences in the weekly loading periodization according the development stage. The weekly field-based load was higher in the U18 than U14 and U16. Moreover, the perceived exertion did not differ within age group. The U14 and U16 training process prioritized technical and physical development, while U18 focused on competition. These conclusions were similar with two other reviewed studies that included only the training data [47,48]. Importantly, the oldest age group in Wrigley et al. [60] adopted an exponential decrease (tapering). Nonetheless, Coutinho et al. [48] visualized this trend only in U17 age group knowing that this study only applies training data. According to these conclusions, it is possible that different stages of development required different load patterns.

The training mode or sub-components were analyzed for only one study, predominantly in training and match load distribution. Their findings showed that weekly field load was higher than total gym-based load [60]. These data may provide valuable information to the strength and conditioning coach about the high intensity active profiles that could be used to develop soccer-specific training drills [40].

4.3. Relationships between Weekly Internal and External Load

In this systematic review, the relationships between internal and external load were explained in ten studies. Of these studies, five studies reported the relationship within internal load methods, four studies analyzed internal and external load relationships, and one study compared only external load metrics. The literature evidenced positive within and between-individual correlations for perceived exertion, heart rate-derived measures, and external load indicators for elite female [52], semi-professional [115], elite/professional [50,65], and young amateurs [53,98]. The magnitude of correlations tended to increase when it was considered a within-individual correlation. The sRPE was a consistent method to quantify internal load along an entire season. The internal training load may be useful to assess accumulated training load and the relations with external training load by playing position, training mode, and/or age-groups. The reviewed studies showed a relationship between external and internal training load indicators. However, analyzing high intensity demands must take into account some considerations about speed thresholds, metabolic power output, accelerations, and accelerometers measures.

Alexiou and Coutts [52] reported positive correlation for sRPE with Banister’s TRIMP, LTzone, and Edwards’s TRIMP (r = 0.84, r = 0.83, and r = 0.85, all p < 0.01, respectively). Campos-Vazquez et al. [50] also reported correlations between sRPE with TRIMPMOD and Edwards TRIMP (r = 0.92 to 0.98). Casamichana et al. [115] reported associations for Edwards TRIMP with sRPE (r = 0.57 p < 0.01, respectively). The correlations presented by Impellizzeri et al. [54] were statistically significant for sRPE and Edwards, Banister, and Lucia TRIMP’s (from r = 0.50 to 0.85, p < 0.01). Kelly et al. [65] indicated correlation between changes in sRPE and Edwards TRIMP (r = 0.75, p < 0.05). Particularly, these main findings prove that there were correlation changes between perceived exertion and HR measures for elite female [52], semi-professional [115], elite/professional [50,65], and young amateurs [53,98].

Casamichana et al. [115] reported associations for PL with Edwards TRIMP and sRPE methods (r = 0.70 and r = 0.74, all p < 0.05, respectively). Total distance covered associated with PL, sRPE, and Edwards TRIMP methods (r = 0.70 and r = 0.74, all p < 0.05, respectively). Gaudino et al. [108] reported for RPE with HSR, impacts and accelerations (r = 0.14, r = 0.09 and r = 0.25, all p < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, the adjusted correlation for RPE were r = 0.11, r = 0.45, and r = 0.37, respectively. In the study by Rago et al. [107], RPE was moderately correlated to MSR and HSR using the arbitrary method (p < 0.05; r = 0.53 to 0.59). However, the magnitude of correlations tended to increase for the individualized method (p < 0.05; r = 0.58 to 0.67). When the external load was expressed as percentage of total distance covered, no significant correlations were observed (p > 0.05). Scott et al. [57] reported significant correlations for total distance, low-speed running, and PL with the HR-based methods and sRPE (r = 0.71 to 0.84; p < 0.01). The internal measures had correlation with volume of HSR and sprinting (r = 0.40 to 0.67; p < 0.01). Marynowicz et al. [98] reported a large and positive within-individual correlations for total distance, PL, number of ACC, and sRPE (r = 0.70, 0.64, and 0.62, respectively, p < 0.001). Small to moderate within-individual correlations were noted between RPE and measures of intensity (r = 0.16 to 0.39). A moderate within-individual correlation was observed between HSR per minute and RPE (r = 0.39, p < 0.001).

Gaudino et al. [90] compared high-intensity activity using total distance covered at speeds > 14.4 km × h−1 and the equivalent metabolic power threshold (>20 W × kg−1). Measuring high-intensity movements with speed categories may underestimate the energy cost by training sessions and playing positions. Moreover, the difference between methods also decreased as the proportion of high intensity distance within a training session increased (R2 = 0.43; p < 0.001). Therefore, metabolic power estimations may have higher precision to evaluate physical demands during training sessions.

Vahia et al. [58] was the only study that reported monthly correlations (r = 0.60 to 0.73, (p < 0.05) and overall correlation (r = 0.64, p < 0.001). The correlations between sRPE and HR-load were found for all months, consequently sRPE is a consistent method to quantify internal load along an entire season.

Alexiou and Coutts [52] described correlations for sRPR and three HR-based methods by training mode (all p < 0.05): technical (r = 0.68 to 0.82), conditioning (r = 0.60 to 0.79), and speed sessions (r = 0.61 to 0.79). Campos-Vazquez et al. [50] also found a large and very large relations between internal methods: HR > 80% HRmax and HR > 90% HRmax–sRPE during ball-possession games, technical and tactical training (r = 0.61 to 0.68); Edward’s TRIMP–sRPE and between TRIMPMOD–sRPE in sessions with ball-possession games, technical and tactical training (r = 0.73 to 0.87). The reported correlations between the different HR-based methods were always documented (r = 0.92 to 0.98). These results provide clear evidence about the applicability of HR-based methods and sRPE to measure internal load during various training modes. However, the interchangeable application of these methods to measure load and intensity should consider the low validity to quantify neuromuscular load. Kelly et al. [70] verified correlations within playing positions (WD, r = 0.81; CD, r = 0.74; WM, r = 0.70; CM, r = 0.70; attacker, r = 0.84; p < 0.001). The high magnitude of the correlations (large and large to very large) may reflect the lack of specific training for the playing position.

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Directions

There are some limitations that should be addressed in the practical application of this review: (i) the different methodological approaches in the reviewed studies; (ii) the related training load measures, metrics, and thresholds that have varied according to the authors; and (iii) methodological constraints about screening procedures. First, several authors point out that the most contentious limitations were the external validity of data collection. Second, future investigations should consider a meta-analytic procedure to quantify training and match load, with which data extrapolation may underestimate the daily and accumulated load. Thirty, we have considered only full-text articles available in English; this was a language limitation in the literature search strategy.

The wide range of sample sizes (9 ≤ n ≤160) can influence the data comparability such as the characteristics of observations: monitoring periods (3–43 weeks), total training sessions (17–2981) and training sessions per week (3–6). Moreover, future training load analysis should be focused on different coaches, tapering strategies, and continuous seasons. This longitudinal design might include different teams and competitive levels. In the present review, only two studies compared the accumulated training load performed by two teams [88,89]. Most studies conducted the analysis in only one team and/or club wherefore the data may not be representative to other teams and countries. The included studies adhered to different competitive levels, geographic locations, and populations. More studies are needed in order to obtain greater precision in quantifying training load in different locations and competitive levels. Comparing main differences according to the competitive level can provide important information about the level and experience of the players. The studies recruited adult (n = 23) and young (n = 7) players as participants. There is a research gap on female players, given that only one study was conducted in this population [52]. Furthermore, there is no evidence-based study in the daily and accumulated load in goalkeepers, except an exploratory case study that provide a physical load report during a competitive season [123,124].

Several studies included GPS systems in their procedures with different specifications and sampling frequencies (i.e., 5, 10, and 15 Hz). The validity and reliability were well documented in the literature [25,26]. There were some limitations when applying a sampling frequency between 1 Hz and 5 Hz during distances covered at high intensity, speed-based measures, and short linear distances with changes of direction [112]. GPS devices at 10 Hz seem to be the most valid and reliable systems whereas the increase in sampling frequency to 15 Hz does not seem to provide any additional benefit assessing team sport movements [125,126]. The concurrent use of a tracking system (i.e., GPS or LPM) and semi-automatic multiple-camera system (i.e., Prozone®) to quantify training and match demand has obvious implications for the data comparability. The integration of different tracking systems is a methodological strategy applied in three reviewed articles [70,87,106] but there is a moderate typical error in this kind of estimation [10].

The use of GPS technology to estimate energy expenditure during the training session may be underestimated [106]. Metabolic power variables seem to be more suitable to determine high-intensity movements than estimations based on speed [90]. The importance of including acceleration and accelerometer variables to quantify external load was well documented in the present systematic review. The accelerometer parameters including body impact, body load, player load or dynamic-stress load, and the acceleration and deceleration were supported in several reviewed studies. There was no consensus on the use of acceleration thresholds [53]. In addition, the comparison between acceleration variables measured with different tracking systems would be challenging [10]. Future research should focus on comparing demands for acceleration between training sessions and official matches-play measured with the same tracking system. Moreover, specific playing position should be taken into consideration.

The daily and accumulated load were usually lower than other team sports (e.g., Australian Football) and endurance sports [70]. The reviewed studies reported an intra-week variation and gradual reduction to MD-1 or MD-2, which means coaches’ staff reduced volume and intensity during training sessions as competition approached. However, the majority of studies failed to provide any specific context associated with each training day, which may limit the application of such data. None of the reviewed studies focused on training and match load analysis in the seasonal variations during specific training interventions. Therefore, it would be interesting to discover what training modes, sub-components, and exercise typologies contribute to increases or decreases (fluctuations) in certain load measures [127,128]. In team sports (in this case, football), there are some methodological challenges in training load quantification. However, it is not possible to argue that there was a direct causal relationship between physical performance and/or team performance. The dynamic and unpredictable nature of match-play may make it impossible to adjust training and matches [95]. This fact limited the understanding of the relationship between training periodization and individual and team performance [129].

The loading discrepancies within playing positions may significantly affect individual performance and increase injury risk [33]. Therefore, quantifying training load can adjust training periodization models and individualized training sessions. Additionally, Owen et al. [99] allowed the possibility of describing the daily and positional variations through the multi-modal mechanical approach. The content and magnitude of the complementary training sessions were not reported in the literature; wherefore, future investigations about training mode or sub-components effect are recommended. Martin-Garcia et al. [82] noted that future studies should implement mixed small-sided games and running exercise strategies to infer the greatest training stimulus for players with limited playing time (i.e., non-starters and/or fringe player).

The training load quantification in youth football suggested that as players grow older, the training process focus moves to competition whereas in younger players, the training goals were physical and technical development [47,48,60]. Therefore, the weekly microcycle should be adjusted for age. The influence of different weekly microcycle schedules has not yet been established for the competitive performance and long-term development of youth football players. The youth training responses differed markedly from adult and professional players’ due to the development stage of sport specified-skills and physical attributes [130].

The relationships between internal and external load should be interpreted with regard to some limitations. According to Impellizzeri et al. [54], only 50% of HR loading variation were supported by sRPE. However, there is a limitation inherent in the use of HR-based measures to quantify training intensity during anaerobic efforts. This fact may influence the magnitude of the correlation between perceived exertion and HR loading. The perceived exertion appears to be better linked with external load when the speed zones were individually determined than when the arbitrary speed zones [107]. Notwithstanding, there were some limitations in the achievement of real individual maximal values (e.g., maximal aerobic speed) and the speed zone transition. The speed zone transition is very important due to the significant physiological effort associated [131].

5. Conclusions

The present systematic review provided the first report about monitoring accumulated training and match load in football players. Current research suggests that the training and match load variation seem to be influenced by the type of weekly schedule, player’s starting status, playing positions, age group, training mode, and contextual factors. Therefore, there was a related high variation in the weekly loading distribution and a limited load variation during a competitive season. Most of the evidence has implications for adult male professional football players concerning the large body of quantitative studies (QS: 0.65–0.89). In youth football, the studies appear to indicate a small fluctuation across weekly and seasonal accumulated load. However, further studies are recommended to improve knowledge on the female and youth accumulated training/match load monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.T. and P.F.; data curation, J.E.T., J.R. and P.F.; formal analysis, P.F., M.L. and R.F.; funding acquisition, J.E.T., P.F. and A.M.M.; investigation, J.E.T.; methodology, P.F., T.M.B. and A.M.M.; resources, P.F. and A.M.M.; software, J.E.T., J.R. and M.L.; supervision, A.J.S. and A.M.M.; validation, P.F., T.M.B. and A.M.M.; writing—original draft, J.E.T.; writing—review and editing, P.F., R.F., A.J.S., T.M.B. and A.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Douro Higher Institute of Educational Sciences and the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P. (project UIDB04045/2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experimental approach was approved and followed by the local Ethical Committee from University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (Doc2-CE-UTAD-2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available under request to the contact author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express acknowledgement of all coaches and playing staff for cooperation during all collection procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bangsbo, J.; Mohr, M.; Krustrup, P. Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stølen, T.; Chamari, K.; Castagna, C.; Wisløff, U. Physiology of soccer: An update. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 501–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, A.; Kempton, T.; Crowcroft, S.; Coutts, A.J.; Crowcroft, S.; Kempton, T. Developing athlete monitoring systems: Theoretical basis and practical applications. In Sport, Recovery and Performance: Interdisciplinary Insights; Kellmann, M., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Rampinini, E.; Marcora, S.M. Physiological assessment of aerobic training in soccer. J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; Cardinale, M.; Murray, A.; Gastin, P.; Kellmann, M.; Varley, M.C.; Gabbett, T.J.; Coutts, A.J.; Burgess, D.J.; Gregson, W.; et al. Monitoring athlete training loads: Consensus statement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, S2–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, T. The Science of Training Soccer: A Scientific Approach to Developing Strength, Speed and Endurance; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Marcora, S.M.; Coutts, A.J. Internal and external training load: 15 years on. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, C.; McLean, B.; Halaki, M.; Orr, R. Positional differences in external on-field load during specific drill classifications over a professional rugby league preseason. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carmona, C.D.; Pino-Ortega, J.; Sánchez-Ureña, B.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Rojas-Valverde, D. Accelerometry-based external load indicators in sport: Too many options, same practical outcome? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchheit, M.; Allen, A.; Poon, T.K.; Modonutti, M.; Gregson, W.; Di Salvo, V. Integrating different tracking systems in football: Multiple camera semi-automatic system, local position measurement and GPS technologies. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1844–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djaoui, L.; Haddad, M.; Chamari, K.; Dellal, A. Monitoring training load and fatigue in soccer players with physiological markers. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 181, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borresen, J.; Lambert, M.I. The quantification of training load, the training response and the effect on performance. Sports Med. 2009, 39, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branquinho, L.; Ferraz, R.; Travassos, B.; Marinho, D.A.; Marques, M.C. Effects of Different Recovery Times on Internal and External Load during Small-Sided Games in Soccer. Sports Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujika, I.; Halson, S.; Burke, L.M.; Balagué, G.; Farrow, D. An integrated, multifactorial approach to periodization for optimal performance in individual and team sports. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 538–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akubat, I.; Barrett, S.; Abt, G. Integrating the internal and external training loads in soccer. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenhead, R.; Nassis, G.P. Training load and player monitoring in high-level football: Current practice and perceptions. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2016, 11, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halson, S.L. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanrenterghem, J.; Nedergaard, N.J.; Robinson, M.A.; Drust, B. Training load monitoring in team sports: A novel framework separating physiological and biomechanical load-adaptation pathways. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2135–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.L.; Stanton, R.; Sargent, C.; Wintour, S.-A.; Scanlan, A.T. The association between training load and performance in team sports: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2743–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S.J.; Macpherson, T.W.; Coutts, A.J.; Hurst, C.; Spears, I.R.; Weston, M. The relationships between internal and external measures of training load and intensity in team sports: A meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, A.; Brink, M.S.; Probst, S.G.M.; Frencken, W.G.P.; Helsen, W.F. Relationships between training load indicators and training outcomes in professional soccer. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.R.; Rumpf, M.C.; Hertzog, M.; Castagna, C.; Farooq, A.; Girard, O.; Hader, K. Acute and residual soccer match-related fatigue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 539–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hader, K.; Rumpf, M.C.; Hertzog, M.; Kilduff, L.P.; Girard, O.; Silva, J.R. Monitoring the athlete match response: Can external load variables predict post-match acute and residual fatigue in soccer? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, M.K.; Finch, C.F. The relationship between training load and injury, illness and soreness: A systematic and literature review. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, S.; Till, K.; Weaving, D.; Jones, B. The use of microtechnology to quantify the peak match demands of the football codes: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2549–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellaserra, C.L.; Gao, Y.; Ransdell, L. Use of integrated technology in team sports: A review of opportunities, challenges, and future directions for athletes. J. Strength Cond Res. 2014, 28, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rago, V.; Brito, J.; Figueiredo, P.; Costa, J.; Barreira, D.; Krustrup, P.; Rebelo, A. Methods to collect and interpret external training load using microtechnology incorporating GPS in professional football: A systematic review. Res. Sports Med. 2020, 28, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palucci Vieira, L.H.; Carling, C.; Barbieri, F.A.; Aquino, R.; Santiago, P.R.P. Match running performance in young soccer players: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.M.; Griffiths, P.C.; Mellalieu, S.D. Training load and fatigue marker associations with injury and illness: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 943–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampinini, E.; Coutts, A.J.; Castagna, C.; Sassi, R.; Impellizzeri, F.M. Variation in top level soccer match performance. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, P.S.; Carling, C.; Gomez Diaz, A.; Hood, P.; Barnes, C.; Ade, J.; Boddy, M.; Krustrup, P.; Mohri, M. Match performance and physical capacity of players in the top three competitive standards of English professional soccer. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2013, 32, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, M.; Krustrup, P.; Bangsbo, J. Match performance of high-standard soccer players with special reference to development of fatigue. J. Sports Sci. 2003, 21, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Salvo, V.; Baron, R.; Tschan, H.; Calderon Montero, F.J.; Bachl, N.; Pigozzi, F. Performance characteristics according to playing position in elite soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebelo, A.; Brito, J.; Seabra, A.; Oliveira, J.; Drust, B.; Krustrup, P. A new tool to measure training load in soccer training and match play. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 33, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issurin, V.B. New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiely, J. Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: Evidence-led or tradition-driven? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2012, 7, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, C.; Varley, M.; Póvoas, S.C.A.; D’Ottavio, S. Evaluation of the match external load in soccer: Methods comparison. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Haas, S.V.; Dawson, B.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Coutts, A.J. Physiology of small-sided games training in football. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, F.A.; Ackermann, A.; Chtourou, H.; Sperlich, B. High-intensity interval training performed by young athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2018, 27, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, P.S.; Sheldon, W.; Wooster, B.; Olsen, P.; Boanas, P.; Krustrup, P. High-intensity running in English FA Premier League soccer matches. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkins, M.R.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Sherrington, C.; Maher, C. Rating the quality of trials in systematic reviews of physical therapy interventions. Cardiopulm. Phys. Ther. J. 2010, 21, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, R.S.; Davis, J.C.; Liu-Ambrose, T. What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.F.; Conte, D.; Clemente, F.M. Decision-Making in Youth Team-Sports Players: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Helath 2020, 17, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abade, E.A.; Gonçalves, B.V.; Leite, N.M.; Sampaio, J.E. Time-motion and physiological profile of football training sessions performed by under-15, under-17 and under-19 elite Portuguese players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, D.; Gonçalves, B.; Figueira, B.; Abade, E.; Marcelino, R.; Sampaio, J. Typical weekly workload of under 15, under 17, and under 19 elite Portuguese football players. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, C. Physiological Tests for Elite Athletes; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vazquez, M.A.; Toscano-Bendala, F.J.; Mora-Ferrera, J.C.; Suarez-Arrones, L.J. Relationship between internal load indicators and changes on intermittent performance after the preseason in professional soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagno, K.M.; Thatcher, R.; van Someren, K.A. A modified TRIMP to quantify the in-season training load of team sport players. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexiou, H.; Coutts, A.J. A comparison of methods used for quantifying internal training load in women soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2008, 3, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenhead, R.; Harley, J.A.; Tweddle, S.P. Examining the external training load of an English premier league football team with special reference to acceleration. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 2424–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Rampinini, E.; Coutts, A.J.; Sassi, A.; Marcora, S.M. Use of RPE-based training load in soccer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, T.-S.; Reilly, T.; Morton, J.; Bae, S.-W.; Drust, B. Quantification of the physiological loading of one week of ‘pre-season’ and one week of ‘in-season’ training in professional soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, J.J.; Di Michele, R.; Morgans, R.; Burgess, D.; Morton, J.P.; Drust, B. Seasonal training-load quantification in elite English Premier League soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.R.; Lockie, R.G.; Knight, T.J.; Clark, A.C.; Janse de Jonge, X.A. A comparison of methods to quantify the in-season training load of professional soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2013, 8, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahia, D.; Kelly, A.; Knapman, H.; Williams, C.A. Variation in the correlation between heart rate and session rating of perceived exertion-based estimations of internal training load in youth soccer players. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 31, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalen, T.; Lorås, H. Monitoring Training and Match Physical Load in Junior Soccer Players: Starters versus Substitutes. Sports 2019, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrigley, R.; Drust, B.; Stratton, G.; Scott, M.; Gregson, W. Quantification of the typical weekly in-season training load in elite junior soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rago, V.; Rebelo, A.; Krustrup, P.; Mohr, M. Contextual Variables and Training Load Throughout a Competitive Period in a Top-Level Male Soccer Team. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangsbo, J.; Iaia, F.M.; Krustrup, P. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: A useful tool for evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Med. 2008, 38, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banister, E. Modeling elite athletic performance. In Physiological Testing of Elite Athletes; Green, H.J., McDougal, J.D., Wegner, H.A., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1991; pp. 403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, C.; Florhaug, J.A.; Franklin, J.; Gottschall, L.; Hrovatin, L.A.; Parker, S.; Doleshal, P.; Dodge, C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2001, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.M.; Strudwick, A.J.; Atkinson, G.; Drust, B.; Gregson, W. The within-participant correlation between perception of effort and heart rate-based estimations of training load in elite soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S. High performance training and racing. In The Heart Rate Monitor Book; Edward, S., Ed.; Feet Fleet Press: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lucia, A.; Hoyos, J.; Santalla, A.; Earnest, C.; Chicharro, J.L. Tour de France versus Vuelta a España: Which is harder? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 872–878. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, J.; Wisløff, U.; Engen, L.C.; Kemi, O.J.; Helgerud, J. Soccer specific aerobic endurance training. Br. J. Sports Med. 2002, 36, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, J.; Hertzog, M.; Nassis, G.P. Do match-related contextual variables influence training load in highly trained soccer players? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.M.; Strudwick, A.J.; Atkinson, G.; Drust, B.; Gregson, W. Quantification of training and match-load distribution across a season in elite English Premier League soccer players. Sci. Med. Footb. 2019, 4, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los Arcos, A.; Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Martínez-Santos, R. In-season training periodization of professional soccer players. Biol. Sport. 2017, 34, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.; Brito, J.P.; Martins, A.; Mendes, B.; Marinho, D.A.; Ferraz, R.; Marques, M.C. In-season internal and external training load quantification of an elite European soccer team. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, G.; Hassmén, P.; Lagerström, M. Perceived exertion related to heart rate and blood lactate during arm and leg exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1987, 56, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]