Abstract

(1) Background: Teenagers (in particular, females) suffering from eating disorders report being not satisfied with their physical aspect and they often perceive their body image in a wrong way; they report an excessive use of websites, defined as PRO-ANA and PRO-MIA, that promote an ideal of thinness, providing advice and suggestions about how to obtain super slim bodies. (2) Aim: The aim of this review is to explore the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites on female teenagers. (3) Methods: We have carried out a systematic review of the literature on PubMed. The search terms that have been used are: “Pro” AND “Ana” OR “Blogging” AND “Mia”. Initially, 161 publications were identified, but in total, in compliance with inclusion and exclusion criteria, 12 studies have been analyzed. (4) Results: The recent scientific literature has identified a growing number of Pro Ana and Pro Mia blogs which play an important role in the etiology of anorexia and bulimia, above all in female teenagers. The feelings of discomfort and dissatisfaction with their physical aspect, therefore, reduce their self-esteem. (5) Conclusion: These websites encourage anorexic and bulimic behaviors, in particular in female teenagers. Attention to healthy eating guidelines and policies during adolescence, focused on correcting eating behavioral aspects, is very important to prevent severe forms of psychopathology with more vulnerability in the perception of body image, social desirability, and negative emotional feedback.

1. Introduction

Eating disorders are multifactorial disorders, affecting about 0.3% of female teenagers; they have a prevalence included between 1.2% and 4.2%. In particular, anorexia nervosa arises during adolescence, and it can be devastating, potentially included suicidal risk [1,2,3]. A common trait among young women with eating disorders is low self-esteem, with a tendency towards depressed moods. Many factors seem to influence the development and preservation of these disorders among female teenagers. The scientific panorama shows how teenagers with eating disorders have a distorted body image, an wrong perception of their image, and therefore, are more dissatisfied with their physical aspect, in comparison to celebrities. Body image can generate feelings of satisfaction or dissatisfaction and this can cause the individual to make radical choices when treating his/her body [4,5]. In this context, there are a variety of pro-eating disorder communities (websites), and teenagers use social media to talk about their physical aspect, their activities, and to exchange advice about weight loss; this condition supports anorexia nervosa, as the problem of weight loss becomes relevant for their lives and the solution to their health problems. In fact, according to the scientific literature, all members of these communities have reported high levels of eating disorders [6].

Pro-ana and pro-mia websites are virtual spaces, in which teenagers can exchange ideas about their body image and physical aspect. An uncontrolled use of these websites is common practice among teenagers, in particular among young women, and is a factor related to eating disorders. In this regard, some years ago, several authors started to include addiction to the Internet and eating disorders among problematic behaviors in adolescents. Frequent use of social networks and the possibility to follow celebrities (e.g., influencers, models, actors, and actresses) influence perception of the self and of one’s own physical and psychological way of being. This happens when there is a social meeting that can influence the user’s (teenager) mood. This desire to look like celebrities on social networks can promote the insurgence and/or preservation of eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia. The influence of social media is growing among female teenagers with advice and tips to lose weight and showing images of thin bodies.

In line with different studies, looking at images of underweight celebrities is associated to an ideal body image and aspiration to lose weight and these conditions can promote eating disorders [7,8].

Pro-ana and pro-mia websites offer feedback on people’s physical aspect: teenagers receive comments on their aspect and advice on how to lose weight [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. These forums are private and the topic being dealt with is the philosophy of absolute thinness [18,19,20]. In recent years, a study by Almenara and colleagues [21] demonstrated that looking for sensations and disinhibition online were both associated with a higher risk of exposure to ana–mia websites for teenage women and young adults. According to Borzekowski et al. (2010), most websites (58%) contain images of celebrities with ultra slim bodies and promote an anorexic lifestyle, and teenagers visiting pro-ana websites seem to have higher levels of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders [10].

Bates (2015) examined the metaphors used in a pro-ana website to talk about oneself. The author has applied the Metaphor Identification Procedure to 757 text profiles and has identified four key metaphorical constructions in self-description by pro-ana members: self as space, self as weight, and improving the self and social self. Bert and colleagues (2016) found 341 pro-ana accounts on Twitter; for each account, the authors analyzed the number of followers, users’ biographical information, and have studied the most used hashtags. These accounts were very popular, having 23.609 followers; users were mainly young women (97.9 percent) and teenagers. This study demonstrated that the most used hashtags were: “thinspiration”, “proana”, “thin15”, “’ana tips”. These accounts contain dangerous information about body image, eating habits, and physical aspect. Bragazzi et el. (2019) studied 402 websites and demonstrated that the media tend to spread images of models who are abnormally thin.

In a previous study, Çelik and colleagues (2015) found a positive correlation between problematic use of the Internet and approach to food, and the problematic use of the Internet predicted these approaches [22]. The dimension of the effect in relation to the negative impact of pro-ED websites is related to eating pathology. Several authors have counted a large number of websites promoting dysfunctional eating behaviors such as anorexia and bulimia [23,24,25,26].

In light of the collected data in the scientific literature, the aim of this report is to explore the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites on female teenagers.

2. Materials and Methods

Data for this systematic review have been collected in compliance with the reporting elements used for systematic reviews and meta-analysis [27]. PRISMA consists of a checklist aimed at making preparation and reporting of review/meta-analysis studies easier, by identifying, selecting, and critically assessing analyzed research and analyzing data from the studies included in the review.

2.1. Criteria for Eligibility

The articles have been included in the review according to the following inclusion criteria: English language, publication in peer reviewed journals, quantitative information on language processing in movement disorders, and year of publication from 2015—2020. Articles have been excluded according to title, abstract, or complete text for the processes linked to the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites on adolescents and to irrelevance to the topic being dealt with. Further exclusion criteria were review articles, editorial comments, and case reports/series. Moreover, it was arbitrarily decided to start our research in 2015 to provide a more recent outlook on the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites among teenagers.

2.2. Research Strategy

This systematic review has been carried out according to systematic review guidelines [27]. The PubMed database has been searched from 1 January 2015 to 1 January 2020, using 4 key terms related to this topic (“Pro” AND “Ana” OR “Blogging” AND “Mia”). The electronic research strategy used for PubMed is described in Table 1. The articles have been selected according to title and abstract; the entire article has been read if the title/abstract was related to the specific issue of the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites on female teenagers and if the article potentially met inclusion criteria. Moreover, references to the selected articles have been examined in order to identify further studies which could meet the inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

List of search terms entered into PubMed.

2.3. Search Strategy and Study Selection

Overall, bibliographical research has been carried out in the PubMed database, with final research updated to January 2020. Initial research used key terms “Pro” AND “Ana” OR “Blogging” AND “Mia”. The key terms used are related to processes connected to the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites or blogs.

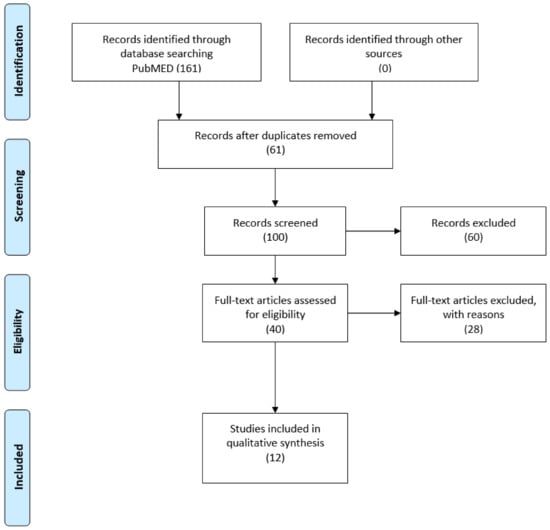

Figure 1 sums up the flow chart of the articles selected for review. Research in the PubMed database provided a total of 161 quotations; no additional studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified when checking the reference list of the selected documents.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (2009) flow diagram.

After checking duplicate copies, 61 records have been examined. Among these, 28 studies have been excluded, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. After the screening, a total of 12 studies, having checked the processes connected to the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites on female teenagers, have met the inclusion criteria and have been included in the systematic review (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the review.

The selected studies have demonstrated the relationship between pro-anorexia and pro-bulimia websites/forums and eating behaviors; a variety of studies have dealt with this topic, in particular research on the relation between pro-ana and pro-mia websites and the desire to lose weight.

This review has examined the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites on female teenagers. Articles have been selected according to title and abstract; the entire article has been read if the title/abstract was related to the specific issue of the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites on female teenagers in relation to eating disorders; and if the article potentially met the inclusion criteria. Details are reported in Table 1 and Table 2. Additionally, references to the selected articles have been examined in order to identify further studies which could meet inclusion criteria (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prisma checklist.

2.4. Bias Risk among Studies

In all studies included in this review, a potential bias of the database should be considered. Only articles in English have been used, which could have compromised access to articles published in other languages.

3. Results

Most analyzed research has focused on the negative influence of websites in female teenagers with eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia. These websites have seemed to offer a sense of support to teenagers vulnerable to eating disorders. These studies have explored teenagers’ exposure to these websites, personal profiles related to popular access to social network, as well as pro-ana accounts on Twitter [18,21,26,28]. Other more social aspects, linked to communication and language, have been explored in a recent study on language and information used on this website [29,30,31]. The relationship between a problematic use and abuse of the Internet and eating behaviors in adolescents has been investigated, as well as negative online support in the case of pro-anorexia websites [11,14,22]. Psychological aspects are generally explored as a potential risk of eating disorders to exacerbate symptoms of users’ websites eating disorders in a sample population [17,32]. Another study has explored the physical and mental state of people participating in pro-anorexia web communities [33]. In particular, Almenara and colleagues (2016) have demonstrated that looking for sensations and disinhibition online were both associated with a higher risk of exposure to ana–mia websites, in male and female teenagers, although some gender differences were evident. In girls, but not among boys, the older the teenager was and the higher her socioeconomic status was, the higher the chances were of being exposed to “ana-mia” websites. Bates (2015) has identified four key metaphorical constructions in self-description by pro-ana members: self as space, self as weight, and improving the self and social self. These four main metaphors represented speech strategies, both in order to create a collective pro-ana identity and to enact an individual identity as pro-ana. Bert et al. (2016) have highlighted a high number and popularity pro-anorexia groups on Twitter. These accounts contain dangerous information, especially considering the users’ young ages. The investigation by Bragazzi et al. (2019) aimed at carrying out a systematic analysis of the reliability and content of websites related to anorexia nervosa in the Italian language. Çelik et al. (2015) have shown a significant positive correlation between a problematic use of the Internet and eating disorders. A problematic use of the Internet is a predictor of eating disorders. Chang and Bazarova (2016) demonstrated that publications containing emotional words linked to stigma, the specific content of anorexia, and very correlational content generally trigger negative feedback from other members of the pro-anorexia community. Gale et al. (2015) have demonstrated that pro-eating disorder websites lead to preserving the behavior of the eating disorder. These websites seemed to offer a sense of support to teenagers with eating disorders. Hernández-Morante et al. (2015) have stated that pro-eating disorder websites influence eating behaviors, including obesity. Hilton (2018) has shed light on the role of pro-anorexia websites in eating disorders. Tan et al. (2016) have examined models of Internet and smartphone apps, for individuals showing eating disorders. Overall, any use of applications for smartphones was associated with a younger age and a higher psychopathology of eating disorders and psychosocial deficit. Yom-Tov et al. (2016) have explored the characteristics of people participating in different pro-anorexia web communities and the differences among them, and have shown that the women members of the main pro-ana website investigated seem to be depressed.

4. Discussion

According to the scientific literature, eating disorders are a serious psychiatric disease, with a mortality rate going from 5 to 6 percent, higher than all other mental disorders. In particular, anorexia is difficult to treat and, in the cyberspace, there is a phenomenon of pro-eating disorder websites, in particular pro-anorexia, that means there are many websites supporting anorexia—pro-ana and pro-mia. The aim of these websites is to promote an anorexic lifestyle. These websites can encourage unhealthy habits and in particular, can promote eating disorders [28,29]. Most analyzed research is focused on the social effects of pro-ana and pro-mia websites, and different authors have demonstrated that they most frequently are visited by the young female population [34,35,36]. However, some recent research suggests that pro-ana and pro-mia websites can encourage negative eating behaviors, such as promoting a pro-anorexic approach, through suggestions and tips to lose weight. The literature mainly examines the social influence of the media and has shown that these websites and blogs show ideal images of absolute thinness [37,38,39].

Several authors have identified many bloggers focused on pro-anorexic lifestyles and diets, giving advice and tips on how to lose weight (such as laxatives, purging in the shower, excessive exercise, calorie restriction, slimming pills, limitations in eating habits), extreme thinness, negative messages about food, and information about body image. Researchers have studied other aspects that can promote eating habits such as competition among members of these blogs to lose weight and be thin. Members of these communities would like to use their body image as inspiration models, for example, in the website’s gallery. This is in line with anti-recovery, because these blogs, communities, and/or websites reject recovery and medical treatment for eating disorders. Another form of resistance involved in these websites is disagreement with psychiatric and psychological treatment [30,31,32,33,34,35].

Most users of these websites are teenagers and have a complex psychological relationship with food—maybe they use it as a reward, a punishment, or they even feel guilty for eating some specific hypercaloric foods. According to the epidemiology of eating disorders, many accounts on pro-ana and pro-mia websites are managed by girls and in 58% of cases, websites contain images intended to encourage weight loss. Young women are particularly vulnerable to this kind of website, are attracted to them, and in fact, the most common people visiting pro-eating disorder websites are 13-, 15-, and 17-year-olds [10].

An important cognitive aspect found is connected to recursive thought. Sharing emotions is maladaptive when users, instead of reconsidering a negative event, continue to brood over it. Thinking continuously makes a negative event more enjoyable and prevents individuals from distraction, therefore intensifying stress, anxiety, shame, and other negative emotions associated with that event [40]. Brooding over a negative event and its meaning, without cognitively reconsidering that event, has proven to intensify negative emotions, making users even more depressed, anxious, and angry in comparison to the initial self-revelation. In these websites, users through pro-ana and pro-mia forums always brood over the same topic. Results have shown that mainly young women feel uncomfortable and often dissatisfied with their body image, and have consequently reduced their self-esteem and have difficulty in relational and social activities [41,42].

However, there is a limited number of empirical studies in the literature on the topic that have investigated the risks associated with the development of eating psychopathology in adolescents. The existing literature on pro-eating disorder websites has not focused on clinical and psychopathological behaviors that can lead also to a serious risk of suicide in young populations. It is very important to focus on the risk of using websites and forums encouraging maladaptive eating habits, especially in vulnerable teenagers with problems linked to food. Higher behavioral risks in the use of eating disorder websites show a higher tendency to isolation, negative emotions, and maladaptive eating habits, which can be predictors of eating disorders or can exacerbate subclinical pictures in vulnerable subjects.

The paper highlights the importance of a study focused on the psychological impact of pro-ana and pro-mia websites in female teenagers with vulnerabilities in eating habits. The psychological impact of images, texts, words, and of a maladaptive eating approach for an ultra-slim body is an extremely complex process, and is dangerous for teenagers’ body image. There are many psychological and identity development factors, as well as socio-cognitive skills and aspects of social desirability that are involved.

Our results suggest the importance of paying attention to psychoeducation among teenagers about eating disorders, food nutritional principles, and provide correct information on factors preparing, precipitating, or preserving the insurgence of eating disorders. This plays an important role in order to improve quality in their life and to reduce the risk of eating disorders.

5. Limitations

A limitation of the present study is the scarce literature on this topic. There are few empirical studies that explain the psychological motivation that attracts adolescents to eating websites.

6. Conclusions

As highlighted in the scientific literature, pro-ana and pro-mia websites promote a negative approach to food in a vulnerable population, such as in adolescents, and these conditions can encourage the insurgence of eating disorders.

Explaining this phenomenon connected to the use of forums and websites among female teenagers is fundamental because anorexia and bulimia are very serious and dangerous diseases, with higher incidence in the period of teenage development. However, it is very important to identify online contents and raise awareness on the level of danger of these websites and on maladaptive eating approaches among young people. Different studies have found out that a negative self-image can limit quality of life and pro-anorexia and pro-bulimia websites do not cause eating disorders but can encourage them. As far as the research topic is concerned, it is necessary to implement actions of promotion of guidelines and policies for healthy eating habits in the target population. Some aspects are relevant to improve the impact of research on prevention in the teenage population because at the moment, there are not many empirical studies in the literature explaining it.

The need to prematurely recognize maladaptive signs, words, beliefs, and approaches in adolescents for healthy eating guidelines and policies with specific programs of school education, even for teachers and parents. These healthy eating contexts can raise awareness on problematic eating behaviors and identify cases needing counselling and treatment or, in the most serious cases, hospitalization, therefore reducing the potential for a wide range of teenagers being trapped in the net. Further research to understand the correlation between personality profile and the impact of exposure to “Ana-mia” websites on the prevention of mental health issues in teenagers is recommended. The issue is relevant in young populations to prevent the risk of suicide and psychopathological and mental problems in adulthood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization C.M. and M.R.A.M.; methodology M.C.S. and A.B.; da-ta curation, C.M., M.C.S. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation C.M., M.R.A.M., R.A.Z.; writing—review and editing C.M., A.R., L.C., M.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Yom-Tov, E.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Weber, I.; Crain, S.P.; Lewis, S. Pro-Anorexia and Pro-Recovery Photo Sharing: A Tale of Two Warring Tribes. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arts, H.; Lemetyinen, H.; Edge, D. Readability and quality of online eating disorder information—Are they sufficient? A systematic review evaluating websites on anorexia nervosa using DISCERN and Flesch Readability. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delforterie, M.J.; Larsen, J.K.; Bardone-Cone, A.M.; Scholte, R.H.J. Effects of Viewing a Pro-Ana Website: An Experimental Study on Body Satisfaction, Affect, and Appearance Self-Efficacy. Eat. Disord. 2014, 22, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, M.M.; Quadflieg, N.; Nisslmüller, K.; Lindner, S.; Osen, B.; Huber, T.; Wünsch-Leiteritz, W. Does internet-based prevention reduce the risk of relapse for anorexia nervosa? Behav. Res. Ther. 2012, 50, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumz, A.; Uhlenbusch, N.; Weigel, A.; Wegscheider, K.; Romer, G.; Löwe, B. Decreasing the duration of untreated illness for individuals with anorexia nervosa: Study protocol of the evaluation of a systemic public health intervention at community level. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hötzel, K.; Von Brachel, R.; Schmidt, U.; Rieger, E.; Kosfelder, J.; Hechler, T.; Schulte, D.; Vocks, S. An internet-based program to enhance motivation to change in females with symptoms of an eating disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 1947–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegl, S.; Bürger, C.; Schmidt, L.; Herbst, N.; Voderholzer, U. The Potential of Technology-Based Psychological Interventions for Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Future Research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varns, J.A.; Fish, A.F.; Eagon, J.C. Conceptualization of body image in the bariatric surgery patient. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 41, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yom-Tov, E.; Boyd, D.M. On the link between media coverage of anorexia and pro-anorexic practices on the web. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzekowski, D.L.G.; Schenk, S.; Wilson, J.L.; Peebles, R. e-Ana and e-Mia: A Content Analysis of Pro–Eating Disorder Web Sites. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.F.; Bazarova, N.N. Managing Stigma: Disclosure-Response Communication Patterns in Pro-Anorexic Websites. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Waller, G. Media Influences on Body Size Estimation in Anorexia and Bulimia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1999, 162, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A.E.; Cheung, L.; Wolf, A.M.; Herzog, D.B.; Gortmaker, S.L.; Colditz, G.A. Exposure to the Mass Media and Weight Concerns Among Girls. Pediatrics 1999, 103, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, L.; Channon, S.; Larner, M.; James, D. Experiences of using pro-eating disorder websites: A qualitative study with service users in NHS eating disorder services. Eat. Weight. Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2016, 21, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, A.; García, D.; Räsänen, P. Proanorexia Communities on Social Media. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Skowron, S.; Chabrol, H. Disordered eating and group membership among members of a pro-anorexic online community. Eur. Eating Disorders Rev. 2012, 20, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouleau, C.R.; Von Ranson, K.M. Potential risks of pro-eating disorder websites. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C.F. “I am a waste of breath, of space, of time” metaphors of self in a pro-anorexia group. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boepple, L.; Thompson, J.K. A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapton, O. Pro-anorexia: Extensions of ingrained concepts. Discourse Soc. 2013, 24, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenara, C.A.; Machackova, H.; Smahel, D. Individual Differences Associated with Exposure to “Ana-Mia” Websites: An Examination of Adolescents from 25 European Countries. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Ç.B.; Odacı, H.; Bayraktar, N. Is problematic internet use an indicator of eating disorders among Turkish university students? Eat. Weight. Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2015, 20, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lowy, A.S.; Halperin, D.M.; Franko, D.L. A Meta-Analysis Examining the Influence of Pro-Eating Disorder Websites on Body Image and Eating Pathology. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016, 24, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daga, G.A.; Gramaglia, C.; Pierò, A.; Fassino, S. Eating disorders and the Internet: Cure and curse. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2006, 11, e68–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardone-Cone, A.M.; Cass, K.M. What does viewing a pro-anorexia website do? An experimental examination of website exposure and moderating effects. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007, 40, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yom-Tov, E.; Brunstein-Klomek, A.; Mandel, O.; Hadas, A.; Fennig, S.; Milton, A.; Chen, T.; Rodgers, R. Inducing Behavioral Change in Seekers of Pro-Anorexia Content Using Internet Advertisements: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). J. Chin. Integr. Med. 2009, 7, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Camussi, E.; Siliquini, R. Risks and Threats of Social Media Websites: Twitter and the Proana Movement. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Prasso Gre, T.S.; Zerbetto, R.; Del Puente, G.A. Reliability and content analysis of Italian language anorexia nervosa-related websites. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2019, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Morante, J.J.; Jiménez-Rodríguez, D.; Cañavate, R.; Conesa-Fuentes, M.D.C. Analysis of Information Content and General Quality of Obesity and Eating Disorders Websites. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 606–615. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, C.E. “It’s the Symptom of the Problem, Not the Problem itself”: A Qualitative Exploration of the Role of Pro-anorexia Websites in Users’ Disordered Eating. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Kuek, A.; Goh, S.E.; Lee, E.L.; Kwok, V. Internet and smartphone application usage in eating disorders: A descriptive study in Singapore. Asian J. Psychiatry 2016, 19, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yom-Tov, E.; Brunstein-Klomek, A.; Hadas, A.; Tamir, O.; Fennig, S. Differences in physical status, mental state and online behavior of people in pro-anorexia web communities. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T.M.; Yang, W.; Chen, C.-S.; Reynolds, K.D.; He, J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojo-Lucena, F.-J.; Aznar-Díaz, I.; Cáceres-Reche, M.-P.; Trujillo-Torres, J.-M.; Romero-Rodríguez, J.-M. Problematic Internet Use as a Predictor of Eating Disorders in Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jett, S.; Laporte, D.J.; Wanchisn, J. Impact of exposure to pro-eating disorder websites on eating behaviour in college women. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2010, 18, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boero, N.; Pascoe, C. Pro-anorexia Communities and Online Interaction: Bringing the Pro-ana Body Online. Body Soc. 2012, 18, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K.; Keys, T. Anorexia/bulimia as resistance and conformity in pro-Ana and pro-Mia virtual conversations. In Critical Feminist Approaches to Eating Disorders; Moulding, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lladó, G.; González-Soltero, R.; De Valderrama, M.J.B.F. Anorexia y bulimia nerviosas: Difusión virtual de la enfermedad como estilo de vida. Nutr. Hosp. 2017, 34, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimé, B.; Finkenauer, C.; Luminet, O.; Zech, E.; Philippot, P. Social Sharing of Emotion: New Evidence and New Questions. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 9, 145–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, D.; Peter, J.; De Graaf, H.; Nikken, P. Adolescents’ Social Network Site Use, Peer Appearance-Related Feedback, and Body Dissatisfaction: Testing a Mediation Model. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, C.; Marini, M.; De Antoni, E.; Scarpa, C.; Brambullo, T.; Bassetto, F.; Mazzotta, A.; Vindigni, V. Psychological and Psychiatric Traits in Post-bariatric Patients Asking for Body-Contouring Surgery. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2017, 41, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).