Abstract

Managing medicine shortages consumes ample time of pharmacists worldwide. This study aimed to explore the strategies and resources being utilized by community pharmacists to tackle a typical shortage problem. Qualitative face-to-face interviews were conducted. A total of 31 community pharmacists from three cities (Lahore, Multan, and Dera Ghazi Khan) in Pakistan were sampled, using a purposive approach. All interviews were audio taped, transcribed verbatim, and subjected to thematic analysis. The analysis yielded five broad themes and eighteen subthemes. The themes highlighted (1) the current scenarios of medicine shortages in a community setting, (2) barriers encountered during the shortage management, (3) impacts, (4) corrective actions performed for handling shortages and (4) future interventions. Participants reported that medicine shortages were frequent. Unethical activities such as black marketing, stockpiling, bias distribution and bulk purchasing were the main barriers. With respect to managing shortages, maintaining inventories was the most common proactive approach, while the recommendation of alternative drugs to patients was the most common counteractive approach. Based on the findings, management strategies for current shortages in community pharmacies are insufficient. Shortages would continue unless potential barriers are addressed through proper monitoring of the sale and consumption of drugs, fair distribution, early communication, and collaboration.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the presence of medicine shortages in both developed and developing countries []. In 2017, the WHO reported that almost two billion people have no access to basic medicine, leading to less patient care and costly financial consequences []. As shortages become more ubiquitous, pharmacists and other healthcare professionals are also spending more time managing them []. This means that shortages are likely to impact the workload and clinical decision-making process of healthcare professionals.

There is a paucity of literature, exploring strategies for shortages management at a community pharmacy. Previous research was more concerned on determining the frequency of medicine shortages at community pharmacies [,,]. According to a Finnish study, 80% of community pharmacies encountered shortages almost daily over the 27-day study period []. Similarly, in 2015, an Irish survey identified the number, and duration of shortages in a community setting. This study explored that 65/1232 (5.3%) of dispensed drugs were unavailable and had a shortage duration of 13 days on average []. The Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union survey (PGEU) examined medicine shortages at EU level as reducing patient confidence (92%), employee satisfaction (79%) and increasing financial losses (82%) [].

According to the WHO report, the availability of essential medicines in LMICs is only 35 percent in public institutions and 66 percent in the private sector, and this is also true for Pakistan’s healthcare system []. Due to the unavailability of essential medicines in Pakistani public hospitals, doctors force the patient, nearly 67%, to visit community pharmacies. Patients therefore obtain medicines from the private sector instead of from public hospitals []. Moreover, patients prefer to buy medicines for minor ailments at community pharmacies to avoid long queues and waiting times in hospitals []. Almost 80% of the medicines are provided through these channels [].

The black marketing of medicine is also one of the reasons why Pakistan is facing medicine shortages [,]. When drugs become in short supply, they are hoarded and sold to patients at higher prices due to a weak enforcement of the law []. Whenever the seasonal demand for certain drugs increases, suppliers stock this product or relocate it to other districts, which eventually exacerbates the shortage situation [].

Addressing medicine shortages is a difficult task, one that requires advanced professional skills such as extensive pharmaceutical expertise, strong communication and collaboration skills [,]. At hospitals, the health care team (physicians, pharmacists and nurses) is involved in managing shortages, while in community pharmacies the pharmacist is the sole decision-maker to manage them. Hence, our study aims to uncover the role of community pharmacists in a typical shortage situation, exploring the strategies and resources used to minimize disruption and continuity of patient care, and identifying opportunities for additional support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A qualitative study was performed based on face-to-face interviews using a semi-structured interview guide. We opted for a qualitative design due to the following reasons. Firstly, the design is flexible and can explore respondents’ attitudes, experiences and intentions []. Secondly, it generates a wide range of ideas and opinions that individuals carry out about the issues, as well as disclosing different viewpoints among groups [].

2.2. Study Setting

This study was carried out in three major cities (Lahore, Multan, and Dera Ghazi khan) in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populated province. These cities belong to different socio-economic levels, with Lahore having the highest gross domestic product (GDP) and Dera Ghazi Khan having the lowest. Lahore city is regarded as the main centre of health, education, business and culture [].

2.3. Interview Guide Development

The interview-guide was adapted from a similar Canadian-based study, whose research objective is consistent with our thinking []. This guide included two sections. The first section focused on the demographic questions related to the community setup, whereas the second section assessed the experience of community pharmacists with the shortages including management strategies, perceived barriers, its impact on the pharmacy staff and future interventions (Supplementary Materials). The reliability of the research was assured by preserving records of interviews. The guide was piloted on two community pharmacists before commencing data collection in the form of interviews.

2.4. Participant Enrollment

Participants were recruited using a purposive method until the saturation of themes. Purposive sampling was based on preconceived ideas about the required characteristics of the sample. Thus, target participants were registered community pharmacists who were fluent in the English language, working a minimum of 8 h daily at the community pharmacy, which is the standard working time for community pharmacists in Pakistan []. For the selection of community pharmacies, all major locations within the three cities were covered to make the sample as representative as possible.

Community pharmacists were invited to take part in this study at their workplace. Additional information concerning this study was e-mailed to participants at a reasonable request. Those who agreed to participate were interviewed face-to-face by trained investigators (SO and SA). Data were collected from February to May 2021. The selection process of participants is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ selection for interviews.

All interviews were conducted in English, because it is a comprehensive and exact language. It allows participants to say what they want to say without having to argue about the meaning []. Moreover, pharmacists can easily communicate in English as it is mainly used as a teaching medium in institutions and universities of Pakistan. Each interview took approximately 20 minutes to complete. Participants were provided with an opportunity to freely express additional opinions and comments. All interviews were audio recorded. The researcher wrote field notes during the interviews and shared the written transcripts with the study participants for comments and corrections.

2.5. Qualitative Analysis

All interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and then analysed under the standard content analysis framework. In the first step, one researcher (SO) listened to the audio recordings several times and transcribed verbatim. SO also used field notes to confirm the understanding of the transcripts. Relevant words, sentences and phrases indicating the objectives of the study were tagged. Initial inductive codes were generated to divide the data, resulting in the formation of a coding table. When several community pharmacists gave the same answer to a particular question, this was seen as a significant finding. Two researchers (SO and SA) then aggregated the final inductive codes into the significant categories. Themes and sub-themes were developed by grouping together several categories to conceptualize the data. Qualitative data managing software (NVivo version 12 Plus, Australia) was used for analysis. All authors had regular discussions to check their common understanding of emerging themes, where ambiguity existed; the final decision was made by the lead author, YC.

Exemplar quotations from the interviewees are presented in the results to demonstrate the findings. Where appropriate, the expressions or words removed from the exemplary quotations have been replaced with three dots.

2.6. Reporting

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was taken into account in reporting methods and results [].

2.7. Ethical Permission

Ethical approval was obtained from Xi’an Jiaotong University, Health Science Center Biomedical Ethics Committee (reference number: 2021–1192) at date 2 February 2021 to develop this research in Pakistan. Participants’ consent was gained after explaining the goals and objectives of the study. Pharmacists working in community pharmacies were contacted and the researcher explained the intent of this research. Each participant’s identity has been kept confidential by issuing an identification code. Participants were allowed to ask any questions regarding the study and all concerns were addressed candidly. We ensured that all the necessary details were clearly communicated. Finally, participating pharmacists were asked to give their consent prior to the start of the interview. A pressure-free and secure environment was maintained during interviews. Study participants were free to raise concerns, skip a question or even withdraw from the interview without giving reasons, although none chose to leave the interview.

3. Results

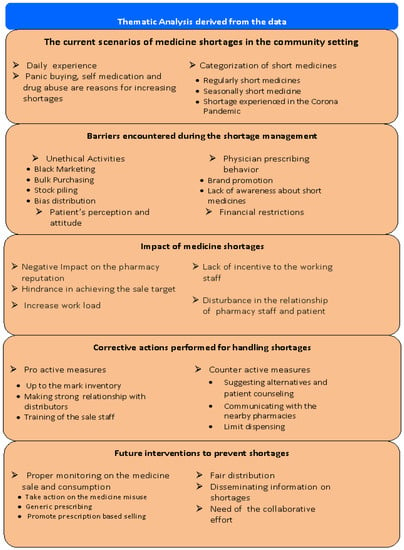

A total of 31 pharmacists were interviewed. Most were aged between 31 to 40 years. Of those interviewed, the majority were male (25, 80.6%) and employed in the independent community setup (17, 54.8%). The respondents’ characteristics are outlined in the Table 2. The analysis of data yielded five themes, including the current scenarios of medicine shortages in the community setting, barriers encountered during the shortage management, impact of medicine shortages, corrective actions performed for handling shortages and future interventions to prevent shortages. These themes are presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Participant demographic Profile.

Figure 1.

Themes derived from the data.

3.1. Theme 1: The Current Scenarios of Medicine Shortages in the Community Setting

Irrespective of either chain or independent pharmacies, almost all participants claimed to experience medicine shortages in the past year. Essential medicines, such as cardiovascular medicines, anti-diabetic medicines, antibiotics and psychotropic agents were most likely to be in short supply. Participants declared that shortages have surged in recent years, particularly in the COVID-19 pandemic due to panic buying, self-medication and drug abuse. Misinformation and rumours about COVID-19 treatment resulted in panic buying and irrational drug use. Participants reported that there was an increase in demand for multivitamins and calcium in the COVID-19 pandemic. Some medicines were short only in a particular season, for example, the antibiotics used to treat upper respiratory tract infections became short in the winter season, whereas others were continuously in short supply throughout the year, such as psychotropic agents. As an overview, the theme related to the current scenario of medicine shortages in the community setting, along with categories and exemplar quotations, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The Current Scenarios of Medicine Shortages in the Community Setting, subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations.

3.2. Theme 2: Barriers Encountered during the Shortage Management

Community pharmacists reported multiple challenges in managing shortages at various levels. Medicines were often bought from the black market, though it was against the Drug Act of Pakistan. Similarly, stockpiling and bulk purchasing were also noticed in the shortage situation. Beside this, independent pharmacies have confronted discrimination from distributors. Comparing with independent pharmacies, distributors preferred chain-pharmacies for stock delivery, which was unfair to these independent pharmacies.

Patient perception and attitude have hampered the success of shortage management. Even if an alternative of the short-supplied medicine was available, patients refused to buy the alternative as they believe only the medicine written on the prescription was effective. In addition, they could hardly accept the fact that the medicine was short from the supplier end and just blamed the pharmacy staff.

Several participants raised concerns about the physician’s prescribing behaviour. Physicians prescribed medicines with the commodity name, not the generic name, due to the promotion of manufactures. Physicians were unaware about the short-supplied products and prescribed them as well. Financial constraints were also an issue for independent pharmacies. When the short-supplied product became available in the market, it usually came with a high price, which was overwhelming for independent pharmacies. As an overview, the theme related to barriers encountered during the shortage management, along with subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations, is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Barriers encountered during the shortage management strategies, subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations.

3.3. Theme 3: Impact of Medicine Shortages

Participants reported multiple impacts of shortages on pharmacy business and pharmacy staff. Sales targets were not achieved, and a negative impact on the pharmacy’s reputation was seen. Patients usually lost trust in pharmacies when certain medication was unavailable and refused to buy all if one of the prescribed medicines was out of stock. In this way, shortages have badly affected the reputation and sales of the pharmacy concomitantly.

In times of shortage, due to limited sales and profits, no incentives were provided to workers, and they felt dissatisfied. Additional workloads had been experienced. Interviewees stated that shortages exerted considerable pressure on pharmacists and work staff, taking up time that could have been invested in other important pharmacy activities. It was also reported that the relationship between the pharmacist and patients had been seriously impacted. When some medicine was unavailable, patients blamed pharmacy staff for it. Most of time, patients did not visit again to purchase any medicine. As an overview, the theme related to impact of medicine shortages, along with subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Impact of medicine shortages, subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations.

3.4. Theme 4: Corrective Actions Performed for Handling Shortages

Both pharmacies, chain and independent, had relatively similar attitudes towards managing shortages. They used both proactive and counteractive approaches to address the shortages. The most common proactive approach was to maintain inventory up to the mark. For this, purchase orders were placed by keenly observing the prescription trend and previous sales data. A wide range of medicines had been procured. Medicines with high customer demand were purchased in large quantities. In addition, the community pharmacist recorded the missing supplies in a logbook, and sufficient inventory could be purchased when available. Maintaining good relations with distributors and training of the pharmacy were also widely applied proactive approaches.

Suggesting alternative medicine and patient counselling was the most popular counteractive approach. In this context, patients were able to continue treatment without any disruption. Depending on the specific situation, the pharmacist may require a new prescription or suggest a change and get the consent of prescriber. When patients refused the alternative medicine then pharmacists searched the availability of the short medicine at surrounding pharmacies, if they could arrange. Pharmacists have also modified their dispensing practices to deal effectively with the shortages. As an overview, the theme related to corrective actions performed for handling shortages, along with subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Corrective actions performed for handling shortages, subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations.

It seems that chain pharmacies have an edge over independent pharmacies for handling shortages. Firstly, chain pharmacies have sufficient budgets, and investments to easily prioritize the supply of those medicines that would expect to be in short supply. Secondly, they have a central warehouse to keep the medicine stock. In contrast, independent pharmacies totally rely on distributors to obtain medicine stock, and when they contact distributors to acquire the medicines, they usually cannot obtain the adequate supplies.

3.5. Theme 5: Future Interventions to Prevent Shortages

Participants suggested that the sale and use of drugs should be followed up appropriately and regulatory authorities should play a vigilant role and take appropriate measures against drug abuse. Implementing generic prescribing may be one solution to prevent shortages. Prescription-based selling of medicines must be ensured to control the shortages originating from the illegitimate sale of medicines, over consumption, drug misuse and abuse. Participants further elaborated that medicine should be distributed evenly among pharmacies, and biased distribution of medicine to wholesalers and chain pharmacies should be discouraged.

Participants emphasized the importance of communication regarding shortages. Prior notice to health care professionals about shortages would facilitate the implementation of necessary remedial actions earlier. Physicians would not prescribe out of stock medicines, and pharmacists would also have sufficient time to manage inventories.

Addressing shortages through collaboration was also considered as a key recommendation for the health care system. As an overview, the theme related to future interventions to prevent the shortages, along with subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Future interventions to prevent shortages, subthemes, categories, and exemplar quotations.

4. Discussion

Medicine shortage is an increasing global phenomenon that poses a significant burden to patients and healthcare systems []. Although a variety of evidence has characterized the prevalence of drug shortages, little research documented its management practices []. This is the first qualitative study performed to examine strategies used to address the shortage within the Pakistani community setting. In this study, five themes and eighteen subthemes were analysed. The themes highlighted the current scenarios of medicine shortages in the community setting, barriers encountered during the shortage management, impacts, corrective action performed for handling shortages and future interventions.

There was a shortage of essential medicines, including cardiovascular medicines, anti-diabetics, antibiotics and psychotropic agents at Pakistani community pharmacies. This result is similar with studies from various other countries such as cardiovascular drugs in Finnish community pharmacies, anti-diabetics in polish pharmacies, and psychotropic agents in a Saudi community setting [,,]. Participants reported a surge in shortages during the pandemic as a result of panic buying, self-medication and substance use. It is also identified that Hydroxycloroquine, multivitamins and the influenza vaccine disappeared from the market during the pandemic.

Community pharmacists reported multiple difficulties in managing shortages at various levels, including black marketing. Drugs in short supply were unavailable on the open market, but at inflated prices on the black market due to weak enforcement of the law. Mansoor has found in (2016) that the blood pressure medicine, Amplodipine, was sold for 50 times higher than its original price on the black market in Pakistan []. Similarly, a Premier Healthcare Alliance survey revealed that grey markets were prevalent for backordered drugs. The average profit margin was 650% above the manufacturer’s sales price, with the highest margins concentrated on the drugs required to treat critical patients [].

Biased medicine distribution has also been a challenge. In Australia, pharmacists employed in independent community settings have also experienced inequitable distribution, and claimed that some chain pharmacies have given priority over independent pharmacies for stock distribution [].

Patient perception and physician prescribing behaviour were also a challenge to the successful management of shortages. Even though community pharmacists tried to help patients with available substitutes, patients refused to take them since they wanted the same brand that was mentioned in the prescription. Physicians were essentially responsible for developing this mindset in patients because they prescribed medications by commodity name and restricted patients to use any substitute. A recent study by Atif et al. (2019) also found that poor prescribing was one of the barriers to the successful management of shortages in Pakistan []. Another gap in prescribing habits was that physicians recommended short medications to patients due to lack of awareness of market status of short supplies.

The shortage situation adversely affected the reputation of pharmacies. Patients did not visit pharmacies with small drug inventories, which had a simultaneous impact on pharmacy sales and credibility. In addition, staff experienced stress with the increased workload to deal with a particular shortage, as it took time to find an appropriate therapeutic alternative and provide relevant information to patients. The Finnish community pharmacists have also reported similar results. Managing shortages at Finnish pharmacies caused increased time burden (52.9%), extra work (21.8%), hasty working environment experience (12.3%), and the median time spent by pharmacy personnel solving drug supply problems was 25 min per week [].

Although, it is often not possible to anticipate when shortages will happen, the process to address them can be predefined []. Therefore, participants took several proactive measures. First, they carefully managed the inventories to ensure that all patients could receive medications for their immediate needs. Second, they developed a strong relationship with distributors. Community pharmacists from Canada also reported that keeping in regular contact with suppliers was a useful strategy to get extra stock before the medicine went on backorder [].

In counteractive measures, the most widely reported approach was to suggest alternative medication to the patient, as it ensures continuous patient care without any disruption. However, pharmacists should be cautious when offering alternative medicine, because it can harm patients by adverse events and medication errors. In 2012, an Associated Press research reported 15 fatalities over a 15-month period due to the complexity of managing medicine shortages []. Community pharmacists further elaborated that their efforts to manage shortages are not enough, unless potential barriers are eliminated. Irrational use of medication due to self-medication and drug abuse has exacerbated the shortage problem. Appropriate control over the use of drugs and strict penalties on the illegitimate sale of a prescription-only drug could possibly decrease the level of medicine shortages uplifted by excessive demand. In Pakistan the laws are often developed, but not applied properly. For instance, The Pakistan Drug Law 1976 outlines the manufacturing, distribution and sale of the medicine, but due to its weak enforcement, medicine shortages cannot be managed properly.

Participants also recommended that multi-faceted collaboration between stakeholders is desirable for the successful shortage management from the manufacturer to the distributor and from the physician to the pharmacist, as multiple stakeholders are involved in the complex issue of shortages. However, it is quite difficult to achieve collaboration for shortages management in the Pakistani healthcare system, because physicians and nurses do not accept pharmacists involvement in direct patient care []. To avert this, the government need to officially recognize pharmacists as an imperative public health professional, which may reinforce their confidence to act in a global health context [].

This study had few limitations. Although the sample size was small, the sample size for qualitative research is not designed to represent a large population and focuses instead on the overview of the real situation. The study participants were recruited only from three cities of Pakistan. However, all of the cities were diverse in terms of their community pharmacy setting. Therefore, the findings are expected to be representative of the situation throughout the country.

To solve the problem of medicine shortages, pharmacists, as medication experts, should play an active role. Firstly, the identification of real-time supply chain disruptions and hiring of specialized supply personnel to continuously review drug supply can be useful []. Secondly, Pharmacists need to keep close contact with the product manufacturer and distributors to gain insight into the disruption’s origin, projected duration and maintain inventories accordingly []. Finally, keeping pace with the growing need for medications and consulting with clinicians to find and offer reasonable alternatives can reduce the impact of drug shortages [].

5. Conclusions

This exploratory research identified current strategies used by community pharmacies to manage shortages. Community pharmacists face multiple barriers that have hampered the success of managing shortages. Current management strategies in community pharmacies are insufficient. Shortages would continue unless potential barriers are addressed through the adequate monitoring of the sale and consumption of drugs, fair distribution, early communication and collaboration.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph182010665/s1, Supplementary file S1: Interview Guide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. and S.O.; methodology, C.Y., S.O. and S.A.; validation, S.O., C.Y. and Y.F.; formal analysis, S.O., S.A. and C.Y.; resources, S.A. and S.S.; data curation, S.S., S.O. and A.H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.; writing—review and editing, S.A., C.Y. and S.O.; visualization, Y.F., S.O. and C.Y.; supervision, Y.F. and C.Y.; project administration, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Department of Science and Technology of Shaanxi Province (2020SF-279).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from Xi’an Jiaotong University, Health Science Center Biomedical Ethics Committee (reference number: 2021–1192) at date (2 February 2021), which complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We express our deep gratitude to all the community pharmacists who participated in the interviews for their time and informative responses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- De Oliveira, G.S., Jr.; Theilken, L.S.; McCarthy, R.J. Shortage of perioperative drugs: Implications for anesthesia practice and patient safety. Anesth. Analg. 2011, 113, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Access to Medicines: Making Market Forces Serve the Poor. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/10-year-review/chapter-medicines.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Association, C.P. Canadian Drug Shortages Survey: Final Report. 2010. Available online: http://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/DrugShortagesReport.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Heiskanen, K.; Ahonen, R.; Karttunen, P.; Kanerva, R.; Timonen, J. Medicine shortages–a study of community pharmacies in Finland. Health Policy 2015, 119, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costelloe, E.; Guinane, M.; Nugent, F.; Halley, O.; Parsons, C. An audit of drug shortages in a community pharmacy practice. Irish J. Med. Sci. 2015, 184, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AESGP; EAHP; EAEPC; EFPIA; EIPG; GIRP; Medicines for Europe; PGEU. Joint Supply Chain Actors Statement on Information and Medicinal Products Shortages. 2 February 2017. Available online: https://www.efpia.eu/media/25913/joint_supply_chain_actors_statement_on_information_and_medicinal_products_shortages.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Zaidi, S.; Nishtar, N. Access to Essential Medicines: In Pakistan Identifying Policy Research and Concerns. 2011. Available online: https://ecommons.aku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.co.uk/&httpsredir=1&article=1189&context=pakistan_fhs_mc_chs_chs (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Kiani, A.; Qadeer, A.; Mirza, Z.; Khanum, A.; Tisocki, K.; Mustafa, T. Prices, Availability and Affordability of Medicines in Pakistan. Geneva: Health Action International. 2006. Available online: http://www.haiweb.org/medicineprices/surveys/200407PK/survey_report.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Qidwai, W.; Krishanani, M.K.; Hashmi, S.; Abu Ali, R. Private drug sellers education in improving prescribing practices. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2006, 16, 743. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Malik, M.; Toklu, H.Z. A literature review: Pharmaceutical care an evolving role at community pharmacies in Pakistan. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atif, M.; Malik, I.; Mushtaq, I.; Asghar, S. Medicines shortages in Pakistan: A qualitative study to explore current situation, reasons and possible solutions to overcome the barriers. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawani, K.; Sayeed, A. Pakistan’s Pharmaceutical Sector: Issues of Pricing, Procurement and the Quality of Medicines; SOAS ACE Working Papers: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DAWN. Medcines Being Sold in Black Market. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1057502 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Pauwels, K.; Huys, I.; Casteels, M.; Simoens, S. Drug shortages in European countries: A trade-off between market attractiveness and cost containment? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Said, A.; Goebel, R.; Ganso, M.; Zagermann-Muncke, P.; Schulz, M. Drug shortages may compromise patient safety: Results of a survey of the reference pharmacies of the Drug Commission of German Pharmacists. Health Policy 2018, 122, 1302–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, B.L.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson Education, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- PAKISTAN: Provinces and Major Cities. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/pakistan/cities/ (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Panic, G.; Yao, X.; Gregory, P.; Austin, Z. How do community pharmacies in Ontario manage drug shortage problems? Results of an exploratory qualitative study. Can. Pharm. J./Rev. Pharm. Can. 2020, 153, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, F.K.; Hassali, M.A.; Khalid, A.; Saleem, F.; Aljadhey, H.; Bashaar, M. A qualitative study exploring perceptions and attitudes of community pharmacists about extended pharmacy services in Lahore, Pakistan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Pandey, P. Better English for better employment opportunities. Int. J. Multidiscip. Approach Stud. 2014, 1, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, J.; Chaar, B.B.; Vera, N.; Pillai, A.S.; Lim, J.S.; Bero, L.; Moles, R.J. Medicine shortages in Fiji: A qualitative exploration of stakeholders’ views. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, E.; Goold, S.; Harrison, S.; Ali, I.; Makki, I.; Kent, S.S.; Shuman, A.G. Drug shortage management: A qualitative assessment of a collaborative approach. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243870. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ruthia, Y.S.; Mansy, W.; Barasin, M.; Ghawaa, Y.M.; AlSultan, M.; Alsenaidy, M.A.; Alhawas, S.; AlGhadeer, S. Shortage of psychotropic medications in community pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: Causes and solutions. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makowska, M. Polish physicians’ cooperation with the pharmaceutical industry and its potential impact on public health. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansoor, H. The Politics of Medicine Pricing. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1289752 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Cherici, C.; McGinnis, P.; Russell, W. Buyer Beware: Drug Shortages and the Gray Market. Charlotte (NC) Premier Healthcare Alliance. 2011. Available online: https://nebula.wsimg.com/d3a344fdd23eb3bb66bb8aa740c5e417?AccessKeyId=62BC662C928C06F7384C&disposition=0&alloworigin=1 (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Tan, Y.X.; Moles, R.J.; Chaar, B.B. Medicine shortages in Australia: Causes, impact and management strategies in the community setting. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, E.; Simoens, S.; Casteels, M.; Huys, I. Time investment in drug supply problems by flemish community pharmacies. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, E.R.; Birt, A.; James, K.B.; Kokko, H.; Salverson, S.; Soflin, D.L. ASHP guidelines on managing drug product shortages in hospitals and health systems. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2009, 66, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L. Associated Press. Drug Shortage Stirs Fear. Available online: https://www.inquirer.com/philly/business/20110924_Drug_shortage_stirs_fears.html (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Azhar, S.; Hassali, M.; Ibrahim, M. Doctors’ perception and expectations of the role of the pharmacist in Punjab, Pakistan. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2010, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steeb, D.R.; Ramaswamy, R. Recognizing and engaging pharmacists in global public health in limited resource settings. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 010318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, M.A.; Tran, L.J.; McGill, B.; Ammar, A.A.; Huynh, P.; Amin, N.; Guerra, M.; Rouse, G.E.; Lemieux, D.; McManus, D. Pharmacists leadership in a medication shortage response: Illustrative examples from a health system response to the COVID-19 crisis. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 4, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuman, A.G.; Fox, E.R.; Unguru, Y. COVID-19 and drug shortages: A call to action. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2020, 26, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).