Abstract

(1) Background: While in many countries, the psychiatric and mental health sectors had been in crisis for years, the onset of a novel coronavirus pandemic impacted their structures, organizations, and professionals worldwide. (2) Methods: To document the early impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis on psychiatry and mental health sectors, a systematic review of the international literature published in 2020 was conducted in PubMed (MEDLINE), Cairn.info, and SantéPsy (Ascodocpsy) databases. (3) Results: After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 72 articles from scientific journals were selected, including papers documenting the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the organization of psychiatric care delivery, work processes in psychiatry and mental health units, and personal experiences of mental health professionals. This review identified the contributions aimed at preventing the onset of mental disorders in the early stages of the health crisis. It lists the organizational changes that have been implemented in the first place to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. It questions the evolution of the rights and duties of mental health professionals in the first months of the pandemic. (4) Discussion and conclusions: Although this literature review exclusively documented the early impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis, it is of significant interest, as it pictures the unprecedent situation in which psychiatry and mental health care professionals found themselves in the first stages of the pandemic. This work is a preliminary step of a study to be conducted with mental health professionals on an international scale—the Psy-GIPO2C project—based on more than 15 group interviews, 30 individual interviews, and 2000 questionnaires. The final aim of this study is to formulate concrete recommendations for decision-makers to improve work in psychiatry and mental health.

1. Introduction

Since late 2019, the world has been impacted by the outset and spread of a new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, responsible for the COVID-19 coronavirus disease. The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020, and a pandemic on 11 March 2020.

The health crisis accompanying this pandemic has been placing an unprecedented burden on psychiatry and mental health care systems, many of which had already been straining for years [1,2]. A large number of countries—including Australia, France, Ireland, and Scotland—are struggling to provide those sectors with the resources they need to deliver care under the right conditions and to recruit staff [3,4].

The COVID-19 health crisis has led health facilities, institutions, and professionals to adapt their organization as well as their practices. A series of measures have been deployed in the early stages of the health crisis to ensure continuity of care and meet the new needs generated by the crisis [5,6] while reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. In response to this situation, the use of digital technologies, and in particular those of telemedicine tools have grown up to an unprecedented scale. In this context, psychiatric and mental health professionals have had to face several issues: They have had to secure continuity of care for both in- and outpatients while following everyday preventive actions, as well as to deal with the population’s demand for care in this unprecedented and anxiety-inducing situation.

Experience from previous outbreaks (SARS, MERS, Ebola, etc.) has shown that epidemic crisis often leads to serious and lasting consequences for the mental health of populations [7,8,9]. In addition to people whose mental disorders potentially worsen, outbreaks tend to cause psychological reactions in the general population ranging from moderate to excessive anxiety and panic [7]. People who have lost a loved one, those who have narrowly escaped death, and their relatives. In this context of the COVID-19 health crisis, frontline health professional, and health professionals in general, are particularly at risk of developing symptoms of burnout, chronic mental illness as depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder [8,10,11,12]. Psychiatry therefore has a crucial role to play in limiting the onset and aggravation of mental disorders, including in regard with health professionals [13,14].

In such an emergency context, first adjustments were made—some of which were more or less anticipated, even improvised—to cope with the situation and ensure continuity of care. Remote consultations have been set up in psychiatry as well as in mixed psychiatric/COVID units and areas have been created in psychiatric structures, for example. These early adaptations nonetheless raise many questions in the specific field of mental health care.

Through this literature review, we proposed:

- -

- First, to examine the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the organization of psychiatric care and on the management of people suffering from severe or moderate psychological disorders in mental health care systems.

- -

- Second, to assess the first impact of the current crisis on both the working conditions and the mental health of psychiatric professionals.

- -

- Third, to analyze reorganizations and innovative practices implemented in psychiatric care settings or by mental health professionals at the beginning of the health crisis.

2. Materials and Methods

The present international systematic review of the literature was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines [15].

After an exploratory search on Google Scholar, the literature search was carried out in three databases: PubMed (MEDLINE), Cairn.info, and SantéPsy (Ascodocpsy). PubMed (MEDLINE) is a database that is traditionally used for literature reviews and allows the collection of English-language publications. To also collect publications in French—as the study is conducted by a French research team—the generalist database cairn.info was also chosen, as well as the SantéPsy database (Ascodocpsy), which is dedicated to resources related to psychiatry and mental health.

The search terms (Table 1) were defined by articulating keywords—previously selected from dictionaries of synonyms and thesauri—and using the Boolean operators “AND”/“OR”. They were constructed with the aim of collecting material that provides specific answers to the issues raised in the study.

Table 1.

Search method of the literature review.

The inclusion criteria allowed to select references published from 1 January to 31 December 2020, in English or French, dealing with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the organization of care delivery and work processes in psychiatry and mental health care, as well as references documenting personal experiences of mental health professionals. Articles of any type were included, except editorials.

The exclusion criteria eliminated references dealing with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the general population or on the mental health of health professionals in general, as well as references related to the neurological and psychiatric effects of SARS-CoV-2, and the psychological effects and neuropsychiatric sequelae of the health measures that have been adopted and implemented. References focusing exclusively on the use of telepsychiatry were not included, and neither were those dealing only with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the training of future mental health professionals, since it seemed more relevant to address these topics in more depth in separate literature reviews.

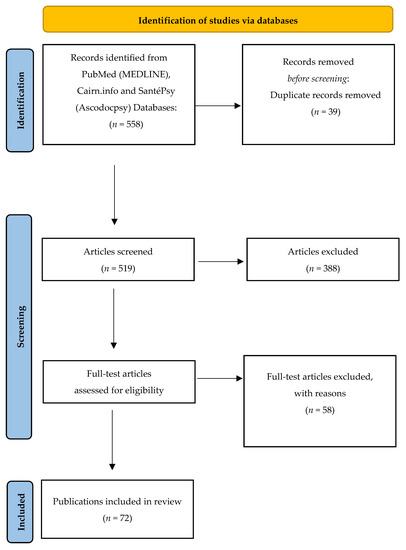

The research yielded 558 documents, including 39 duplicates that were deleted. By applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, first on titles and abstracts, and then on full texts, the first two authors (Gourret Baumgart J and Kane H, respectively a study engineer and research engineer in the Psy-GIPO2C project), performed the search and agreed to select 72 references (Figure 1). Each of these documents was carefully read (Table 2) and analyzed (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Table 2.

Overview of the articles included.

Table 3.

Information about the selected articles.

3. Results

The first observation is that many articles were published in a relatively short period of time. Over the three-month period of this literature review, the number of publications increased rapidly, from 448 articles on 1 November 2020 to 501 on 1 December 2020, and then to 558 articles on 1 January 2021.

Geographically speaking, most of the selected articles are about, or their authors are affiliated with, European countries [30]. Next, many articles follows related to America [17], and then some to Asia (8). Finally, a few articles concern Oceania (3) and Africa (1). Some publications are referred to as “international” in that they deal with, or their authors are affiliated to, several countries (13).

As for the type of articles, most are feedback from personal or field experience written by psychiatric and mental health professionals (38), followed by studies (17), and then literature reviews (13), either narrative or systematic. Finally, a few selected articles are reflections focused on the issue we are addressing (4).

Three major themes emerged:

- Many contributions have been aimed at preventing the onset of mental health disorders in the context of a COVID-19 health crisis;

- Reorganizations were implemented in psychiatric care facilities and units to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission;

- The rights and duties of mental health professionals regarding involuntary treatment have evolved in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1. Preventing the Onset of Mental Health Disorders in the Context of a Health Crisis

3.1.1. An Increasing Role of Care towards the General Population

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health professionals have played a key role in the general population [16,17,18,19,20,60,61]. To mitigate the impact of the health crisis, a large number of programs, aimed at the general population, and focused on the prevention of mental disorders and the promotion of wellbeing, have been implemented, throughout the world. Most of these programs included the use of the phone or the computer [16,17,18,19,20,60]. Mental health professionals have also been involved in providing specific responses to people who found themselves in vulnerable situations—particularly those in relation to containment measures—that could lead to psychological distress or even mental disorders, among which those associated with substance use [20]. In that respect, direct interventions have been carried out towards people living in poverty, homeless people, or victims of domestic abuse and violence [20].

3.1.2. An Expanding Role of Support towards Other Health Professionals

In this context, mental health professionals also provide support to other health professionals, especially to the so-called “front-line health professionals”, who are involved in the care of COVID-19 patients and exposed to stressful situations [44,45,46,47,71]. This is the case of workers in consultation-liaison psychiatry teams, who were already providing support to other healthcare staff members through stress and burnout prevention programs [45]. Programs and plans have been developed specifically to provide psychological or even therapeutic support to health professionals [44,46,47,71]. One of these programs, developed in Turkey, offers support services to the children of health care workers, with the concomitant aim of helping the latter [71]. Whether in existing programs implemented in the context of the COVID-19 health crisis [45] or in those created specifically to address it [44,46,47,71], common logic is at work: The purpose of these interventions is to improve the wellbeing of health care workers and build their resilience so that they can continue to work in the conditions that their duties require and thus contribute to maintaining the overall functioning of healthcare systems [47].

3.1.3. Interventions in Other Work Contexts to Support Fellow Health Professionals

Mental health professionals also intervened—including using digital technologies—in psychiatric and mental health environments where they are not used to work, or in units dedicated to COVID-19 positive patients who are hospitalized under anxiety-provoking conditions of isolation [48,49,62]. In the United States, for example, psychiatrists and psychiatry students assisted palliative care teams deployed to COVID-19 patients in critical situations [48,49]. The mental health professionals whose tasks were thereby reassigned have had to adapt to this new environment and working conditions [21].

3.2. Reorganizing Psychiatric Facilities to Reduce the Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission

3.2.1. Addressing Psychiatric Patients’ Higher Risk of Infection

Due to frequent comorbidities and a weakened immune system, people with mental disorders are at increased risk of infections and severe diseases—especially infectious and pulmonary ones [13,41,54,66]. Even some symptoms of mental illness also often make it harder for them to practice everyday preventive actions [39,41]. Actually, there is frequently a dichotomy between physical and mental health care, which partly explains the importance of somatic comorbidities in these populations [9,21,66]. Psychiatric hospitals rarely have somatic care units, and within this context, psychiatric care professionals have had to adapt to impose preventive measures and organize care for both patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic forms of the virus [13].

3.2.2. Organizing to Prevent Clusters

Since they gather many people in a limited space, psychiatric hospitals are particularly at risk of becoming transmission clusters [7,8,41,59,66], especially since community life and shared activities such as eating together, therapy groups, physical activities, and sports are important parts of therapeutic plans [13,21,41,54,66].

3.2.3. Implementing Multiple Adaptations in Psychiatric Facilities

A significant number of adjustments have been made in psychiatric hospitals to mitigate the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission within while ensuring continuity of psychiatric care [9,13,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,29,30,31,35,36,38,39,42,43,49,52,54,55,58,59,63,64,66,67,68,77,79,80].

They have included preventive measures such as maintaining physical distance and wearing appropriate masks and other adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), as well as cleaning and disinfecting protocols for equipment and premises. Spaces have also been restructured: Many facilities set up areas or units dedicated to patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, or areas for screening procedures such as assessing body temperature and testing [9,21,22,26,29,36,54,63,64,66]. In addition, procedures, markings, and signage were set up to guide traffic and provide advice on preventive actions [9,21,26,54,64]. Many facilities also banned in-person visits to patients [21,26,36,59].

Some hospitals have organized regular team meetings to brief mental health staff members [26], while others have set up training for psychiatric staff in the care of patients with COVID-19 or in the management of the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission [9,29,64,65]. This should allow both a better quality of care and a better quality of work life, since a Chinese study showed that those who have received relevant training would be less afraid of being infected and of infecting their relatives [65].

In addition to these measures, a strategy common to most psychiatric facilities consisted of scaling down their levels of activity, by reducing or even cease outpatient and day-hospital activities, or by cutting down full inpatient admissions as well as the number of available and occupied beds [20,28,59]. As activity declined, more or less formal and formalized approaches led to prioritizing care and identifying the most vulnerable patients [25,26,29]. Such a decrease, reflecting a reduction of inpatients numbers in those facilities, was generally associated with a reduction in the number of staff [21,56].

Another strategy common to most psychiatric hospitals was for professionals to use digital tools in order to ensure continuity of care while reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission [20,22,25,26,28,30,35,39,42,43,48,54,59,63,69,76]. Whereas the use of telepsychiatry was marginal before the health crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic [24,52], the use of videoconferencing tools—including Skype, WhatsApp, and Zoom—has grown considerably worldwide—in America, Europe [43], the Middle East [76], Asia [63], etc. Actually, this unprecedented extension of telepsychiatry was facilitated by a general alleviation of constraints on its use and reimbursement [58]. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, videoconferencing technologies have mainly been used to monitor patients who were usually followed on an outpatient basis and to maintain group therapies, but also to conduct general staff meetings and meetings between professionals [59]. In some cases, the shift from face-to-face to remote communication—through the use of videoconferencing technologies—has been implemented in conjunction with teleworking [52,68]. The mental health professionals who transitioned to telework have had to adapt to these new home-working settings [52,68].

3.2.4. Setting Up Extra-Psychiatric Care Structures

The adaptations implemented in private practices to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission show that the measures and strategies adopted were relatively the same as those of psychiatric care facilities, implying a reduced activity as well as the use of telepsychiatry and of home-based work [24,58,69]. Community mental health facilities have also been forced to adapt their practices to the context [6,27,56,75], replacing as much as possible home visits with phone or videoconferencing consultations, and working from home to avoid sharing an office with other staff [6,56].

In addition to the challenges inherent in maintaining continuity of care within psychiatric wards, mental health professionals have been impacted by the restrictions imposed in the physical care units they work with [35,59,74]. They have also faced challenges in the prescription and delivery of psychiatric medication because of remote follow-up and possible interactions with COVID-19 drugs [53,56,73,75].

3.3. Evolving Regulations on Mental Health Professionals’ Rights and Duties in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.3.1. Questionable Evolution in the Legal Framework for the Practice of Mental Health Professionals

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, national regulations concerning psychiatric care—and more specifically remote psychiatric care and involuntary psychiatric treatment—have been reshaped in several countries [32,52,58,78,81].

In particular, in many countries—including Canada and the USA—the use of telepsychiatry has been facilitated by a general alleviation of constraints on both its use and reimbursement [52,58].

Regulatory changes have also been implemented in the area of involuntary psychiatric treatment. For example, in Germany, the law hitherto in force provided that any individual with mental disorders who is subject to involuntary admission or restraints should be heard personally by a judge, who then had to render a decision authorizing to apply those measures. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been allowed to avoid legal hearings in such cases, on the grounds of “protecting health care and judicial personnel as well as patients” [78]. Similarly, in Ireland, the law providing a framework for the state of emergency changed the procedures for involuntary admissions to psychiatric hospitals [32]. Until then, the legislation provided a specific procedure whereby a psychiatric assessment report had to be issued by an independent psychiatrist, who had to be recognized as such; this report was intended to be a working basis for a court composed of a consultant psychiatrist, a lawyer, and a lay representative to render a decision regarding the patient’s treatment. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been allowed that the psychiatric report would be drawn up by a consultant psychiatrist who did not have to be recognized as an independent expert—with the psychiatric assessment being completed in person or using digital technologies; and that the court could be composed only of a lawyer—with hearings being held by telephone or videoconferencing.

3.3.2. A Lack of Guidance on Professional Practices for Mental Health Workers

While regulations concerning the use of telepsychiatry and involuntary admissions and treatment have been reshaped to fit with the new context, no provisions were adopted—at least initially—to address situations in which a patient refuses to be tested for SARS-CoV-2, thus leaving a legal vacuum. Moreover, mental health care facilities have tried to guide their staff, but psychiatric professionals had little or no recommendations to guide them in dealing with new problematic situations such as involuntary testing [55,81]. Paradoxically, this lack of guidance on some professional practices has been accompanied by the fact that mental health professionals found themselves confused before the “tsunami of information on COVID-19”, which usually took the form of e-mails that were too detailed, unequivocal, or even contradictory [26]. Their personal and professional ethics have been challenged in the face of contradictory orders and incessant changes in policies designed to manage the health crisis [16]

4. Discussion

The present literature review highlights that, during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, all those adaptations implemented to fit the unprecedented context—including new assignments, reorganizations, innovations in psychiatric care, and regulatory changes for professionals—have had a considerable impact on mental health professionals globally, not only on their working conditions and well-being at work, but also on their personal and professional ethics [16,21,29,34,77]. The challenge was to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission; professionals had to get used to new working environments, procedures, and technologies while managing their own stress induced by the health crisis [34]. In this context, making it difficult or even impossible to take time off work, the risk of burnout has become more important for professionals who have kept their activity [13,21]. The fear of being infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the workplace has generally been lower among professionals working in the field of psychiatry than among those working in ambulances, eldercare, and childcare [37]; however, mental health professionals working in geriatric psychiatry mentioned, for instance, their concern about the risk of unintentionally infecting their patients, particularly because of the existence of asymptomatic forms of the disease [34].

This work also highlights that the unprecedented organizational adaptations implemented in psychiatric care facilities in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic are relatively comparable from one working environment to the other, whether in general psychiatric units such as psychiatric emergency departments, or in specialized psychiatric units such as child psychiatry [29,35,43,79], geriatric psychiatry [36,42], addiction units [30,49], and even in prison psychiatry and forensic psychiatry units [31,33,53,57]. While early adaptations are globally the same from one work context and one country to another, organizational responses came faster in some countries than in others. In Taiwan, for instance, systems that had already been set up in the context of the SARS epidemic were deployed again [9].

Articles from this literature reviews point out that the use of mental health services decreased during previous epidemics (Ebola, MERS, SARS, etc.), but that the need for psychiatric and mental health care increased afterwards [28,51,72]. They highlight the need to prepare for this “post-pandemic mental health tsunami” [5,7,8,51].

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review has not been registered. Furthermore, as it includes articles published in 2020 alone, it only documents the early impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis, in the first stages of the pandemic. Plus, it should be noted that many articles included in this literature review were published as early as April and May 2020, and that they are mainly based on a rather weak scientific methodology. This reveals a readiness to publish as well as a lack of maturity on some issues, since carrying out studies with a strong scientific methodology usually requires more time and the allocation of specific resources. Moreover, as highlighted in a literature review conducted in April 2020 [40], such contributions—which are mostly feedback from experience or from the field—do not make it possible to assess the impact of the reported early adaptations, both in terms of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and of the effectiveness of psychiatric care in these new configurations [40]. In addition, the authors of feedback articles may have overestimated the potential of initiatives that have been implemented in their own work contexts, or to which they themselves have contributed. The articles included in the literature review are nonetheless of undeniable interest in that they provide the first keys to understanding the unprecedented situation in which the fields of psychiatry and mental health care have found themselves at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, these articles show the willingness of those involved in psychiatry and mental health care to share organizational innovations and new professional practices implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic health crisis and reflect an acceleration of this trend on an international scale.

5. Conclusions

To sum up, this literature review highlights the need for pandemic preparedness, including in psychiatry and mental health services. Furthermore, although it illustrates how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted psychiatric and mental health facilities and professionals globally in the early stages of the health crisis, it seems necessary to complete the analysis with individual and focus groups interviews and questionnaires to gather additional information. In this sense, it would be interesting to collect information from mental health professionals other than psychiatrists and psychologists—who are over-represented in this review—such as social workers, psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists, and professional peer helpers. It would also be interesting to ask them all about their personal experience of the changes reported in their working environments, processes, and conditions, in order to design methodologies and tools that could allow to improve professionals’ practices and quality of work life in psychiatric and mental health facilities. The final aims of the Psy-GIPO2C study—which is the framework of this literature review—is to formulate concrete recommendations for decision-makers to improve both working conditions and the quality of services provided in psychiatry and mental health services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D. and L.F.-H.; methodology, F.D. and L.F.-H.; software, H.K. and J.G.B.; validation, W.E.-H., J.D., C.M., M.-C.L., D.M. and J.T.; formal analysis, H.K. and J.G.B.; investigation, F.D. and L.F.-H.; resources, F.D. and L.F.-H.; data curation, H.K. and J.G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K. and J.G.B.; writing—review and editing, F.D., L.F.-H., H.K. and J.G.B.; visualization, Emmanuel Rusch; supervision, W.E.-H., J.D., C.M., M.-C.L., D.M. and J.T.; project administration, F.D.; funding acquisition, F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the French National Research Agency (Agence Nationale de la Recherche) and the Region Centre-Val de Loire, France. The funders had and will not have a role in study design, data collection analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tours on 4 February 2021 (and registered under number 2020 006).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are fully available and will be shared upon request to J.G.B.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to especially thank the staff from the University of Tours for administrative and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bourdeux, C. Psychiatry is in crisis. Soins Psychiatr. 2003, 224, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Petho, B. Recent crisis of psychiatry in the context of modern and postmodern science. Psychiatr. Hung. A Magy. Pszichiátriai Társaság Tudományos Folyóirata 2008, 23, 396–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn, B. Recruitment into psychiatry: An international challenge. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2011, 45, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudry, A.; Farooq, S. Systematic review into factors associated with the recruitment crisis in psychiatry in the UK: Students’, trainees’ and consultants’ views. BJPsych Bull. 2017, 41, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thome, J.; Deloyer, J.; Coogan, A.N.; Bailey-Rodriguez, D.; da Cruz, E.S.O.A.B.; Faltraco, F.; Grima, C.; Gudjonsson, S.O.; Hanon, C.; Hollý, M.; et al. The impact of the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental-health services in Europe. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, Z.; Haque, R.; Felzer-Kim, I.T.; Lewicki, T.; Haque, A.; Mormann, M. Implementing COVID-19 Mitigation in the Community Mental Health Setting: March 2020 and Lessons Learned. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.D. Plagues, pandemics and epidemics in Irish history prior to COVID-19 (coronavirus): What can we learn? Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esterwood, E.; Saeed, S.A. Past Epidemics, Natural Disasters, COVID19, and Mental Health: Learning from History as we Deal with the Present and Prepare for the Future. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, S.T.; Chou, L.S.; Chou, F.H.; Hsieh, K.Y.; Chen, C.L.; Lu, W.C.; Kao, W.T.; Li, D.J.; Huang, J.J.; Chen, W.J.; et al. Challenge and strategies of infection control in psychiatric hospitals during biological disasters-From SARS to COVID-19 in Taiwan. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 54, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Foghi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Cordone, A.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Bui, E.; Dell’Osso, L. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.C.; Chirico, F.; Garbarino, S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Santacroce, E.; Zaffina, S. SARS/MERS/SARS-CoV-2 Outbreaks and Burnout Syndrome among Healthcare Workers. An Umbrella Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N.S.; Soave, P.M.; Antonelli, M. Prolonged Stress Causes Depression in Frontline Workers Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Preprints 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevance, A.; Gourion, D.; Hoertel, N.; Llorca, P.M.; Thomas, P.; Bocher, R.; Moro, M.R.; Laprévote, V.; Benyamina, A.; Fossati, P.; et al. Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: A narrative review. Encephale 2020, 46, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Cerveri, G.; Bui, E.; Gesi, C.; Dell’Osso, L. Defining effective strategies to prevent post-traumatic stress in healthcare emergency workers facing the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. CNS Spectr. 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Joboory, S.; Monello, F.; Bouchard, J.P. PSYCOVID-19, psychological support device in the fields of mental health, somatic and medico-social. Ann. Med. Psychol. 2020, 178, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerle, A.; Graf, J.; Jansen, C.; Musche, V.; Schweda, A.; Hetkamp, M.; Weismüller, B.; Dörrie, N.; Junne, F.; Teufel, M.; et al. E-mental health mindfulness-based and skills-based ‘CoPE It’ intervention to reduce psychological distress in times of COVID-19: Study protocol for a bicentre longitudinal study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulfman, R.; Jourdain, P.; Ourahou, O. Pendant le trauma: Une approche de la pathologie psychiatrique des patients atteints par le Covid-19 à travers la plateforme Covidom. L’information Psychiatr. 2020, 96, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoquierre, A.; Diarra, H.; Abed, N.; Devouche, E.; Apter, G. Expérience d’une plateforme d’écoute psychologique multilingue nationale durant le confinement dû à la Covid-19. L’information Psychiatr. 2020, 96, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncero, C.; García-Ullán, L.; de la Iglesia-Larrad, J.I.; Martín, C.; Andrés, P.; Ojeda, A.; González-Parra, D.; Pérez, J.; Fombellida, C.; Álvarez-Navares, A.; et al. The response of the mental health network of the Salamanca area to the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of the telemedicine. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, P.M.; Baghai, T.C.; Rupprecht, R.; Wittmann, M.; Steffling, D.; Ziereis, M.; Zowe, M.; Hausner, H.; Langguth, B. SARS-CoV-2 Risk Management in Clinical Psychiatry: A Few Considerations on How to Deal With an Unrivaled Threat. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocher, R.; Jansen, C.; Gayet, P.; Gorwood, P.; Laprévote, V. Responsiveness and sustainability of psychiatric care in France during COVID-19 epidemic. Encephale 2020, 46, S81–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyer, C.; Ebert, A.; Szabo, K.; Platten, M.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Kranaster, L. Decreased utilization of mental health emergency service during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advenier, F.; Reca, M. Téléconsultations pendant le confinement en cabinet de ville. L’information Psychiatr. 2020, 96, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, H.; Doherty, A.M.; Clancy, M.; Moore, S.; MacHale, S. Lockdown logistics in consultation-liaison psychiatry. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 104, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, X.; Dratcu, L. COVID-19 and acute inpatient psychiatry: The shape of things to come. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpiniello, B.; Tusconi, M.; Zanalda, E.; Di Sciascio, G.; Di Giannantonio, M. Psychiatry during the Covid-19 pandemic: A survey on mental health departments in Italy. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jones, P.B.; Underwood, B.R.; Moore, A.; Bullmore, E.T.; Banerjee, S.; Osimo, E.F.; Deakin, J.B.; Hatfield, C.F.; Thompson, F.J.; et al. The early impact of COVID-19 on mental health and community physical health services and their patients’ mortality in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, UK. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 131, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D. Appreciating COVID-19 as a child and adolescent psychiatrist on the move. Encephale 2020, 46, S99–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columb, D.; Hussain, R.; O’Gara, C. Addiction psychiatry and COVID-19: Impact on patients and service provision. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fovet, T.; Lancelevée, C.; Eck, M.; Scouflaire, T.; Bécache, E.; Dandelot, D.; Giravalli, P.; Guillard, A.; Horrach, P.; Lacambre, M.; et al. Mental health care in French correctional facilities during the Covid-19 pandemic. Encephale 2020, 46, S60–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.D. Emergency mental health legislation in response to the Covid-19 (Coronavirus) pandemic in Ireland: Urgency, necessity and proportionality. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2020, 70, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H.G.; Mohan, D.; Davoren, M. Forensic psychiatry and Covid-19: Accelerating transformation in forensic psychiatry. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsnes, M.S.; Grødal, E.; Kjellén, E.; Kaspersen, T.M.C.; Gjellesvik, K.B.; Benth, J.; McPherson, B.A. COVID-19 Concerns Among Old Age Psychiatric In- and Out-Patients and the Employees Caring for Them, a Preliminary Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 576935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J. ADHD and Covid-19: Current roadblocks and future opportunities. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naarding, P.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Marijnissen, R.M. COVID-19: Clinical Challenges in Dutch Geriatric Psychiatry. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabe-Nielsen, K.; Nilsson, C.J.; Juul-Madsen, M.; Bredal, C.; Hansen, L.O.P.; Hansen, A.M. COVID-19 risk management at the workplace, fear of infection and fear of transmission of infection among frontline employees. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 78, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normand, M. Petite chronique de la psychiatrie au temps de la Covid-19. J. Psychol. 2020, 381, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M.; Thakrar, A.; Akinyemi, E.; Mahr, G. Current and Future Challenges in the Delivery of Mental Healthcare during COVID-19. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, M.A.; Karamsetty, L.; Simpson, S.A. Coronavirus and Its Implications for Psychiatry: A Rapid Review of the Early Literature. Psychosomatics 2020, 61, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovers, J.J.E.; van de Linde, L.S.; Kenters, N.; Bisseling, E.M.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.F.; Oude Munnink, B.B.; Voss, A.; Nabuurs-Franssen, M. Why psychiatry is different-challenges and difficulties in managing a nosocomial outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in hospital care. Antimicrob Resist. Infect. Control. 2020, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, M.; Fahy, S. Coping with the COVID-19 crisis: An overview of service adaptation and challenges encountered by a rural Psychiatry of Later Life (POLL) team. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fegert, J.M.; Schulze, U.M.E. COVID-19 and its impact on child and adolescent psychiatry-a German and personal perspective. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, R.; Myers, M.F.; Fanous, A.H. Support Groups and Individual Mental Health Care via Video Conferencing for Frontline Clinicians During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychosomatics 2020, 61, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeway, D. The Role of Psychiatry in Treating Burnout Among Nurses During the Covid-19 Pandemic. J. Radiol. Nurs. 2020, 39, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellins, C.A.; Mayer, L.E.S.; Glasofer, D.R.; Devlin, M.J.; Albano, A.M.; Nash, S.S.; Engle, E.; Cullen, C.; Ng, W.Y.K.; Allmann, A.E.; et al. Supporting the well-being of health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The CopeColumbia response. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B.; Preisman, M.; Hunter, J.; Maunder, R. Applying Psychotherapeutic Principles to Bolster Resilience Among Health Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Psychother. 2020, 73, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalev, D.; Nakagawa, S.; Stroeh, O.M.; Arbuckle, M.R.; Rendleman, R.; Blinderman, C.D.; Shapiro, P.A. The Creation of a Psychiatry-Palliative Care Liaison Team: Using Psychiatrists to Extend Palliative Care Delivery and Access During the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, e12–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.H.; Best, K. The Psychodynamic Psychiatrist and Psychiatric Care in the Era of COVID-19. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 2020, 48, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, R.C.; Baum, M.L.; Shah, S.B.; Levy-Carrick, N.C.; Biswas, J.; Schmelzer, N.A.; Silbersweig, D. Duties toward Patients with Psychiatric Illness. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2020, 50, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.H.; Schmidt, M.N.; Waits, W.M.; Bell, A.K.C.; Miller, T.L. Planning for Mental Health Needs During COVID-19. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Chung, W.J.; Young, S.K.; Tuttle, M.C.; Collins, M.B.; Darghouth, S.L.; Longley, R.; Levy, R.; Razafsha, M.; Kerner, J.C.; et al. COVID-19 and telepsychiatry: Early outpatient experiences and implications for the future. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser, T.; Hauser, L.; Kapoor, R. The Management of COVID-19 in Forensic Psychiatric Institutions. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelino, A.F.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Ahmed, M.S.; Potash, J.B.; Cullen, B.A. Design and Implementation of a Regional Inpatient Psychiatry Unit for Patients who are Positive for Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2. Psychosomatics 2020, 61, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahed, M.; Barron, G.C.; Steffens, D.C. Ethical and Logistical Considerations of Caring for Older Adults on Inpatient Psychiatry During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, I.; Kirwan, N.; Beder, M.; Levy, M.; Law, S. Adaptations and Innovations to Minimize Service Disruption for Patients with Severe Mental Illness during COVID-19: Perspectives and Reflections from an Assertive Community Psychiatry Program. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.S.; Ruchman, S.G.; Katz, C.L.; Singer, E.K. Piloting forensic tele-mental health evaluations of asylum seekers. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, D.; Oinonen, K. Ontario’s response to COVID-19 shows that mental health providers must be integrated into provincial public health insurance systems. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; LeQuesne, E.; Fichtel, K.; Ginsberg, D.; Frankle, W.G. In-patient psychiatry management of COVID-19: Rates of asymptomatic infection and on-unit transmission. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, N.P.T.; Shoesmith, W.D.; James, S.; Nor Hadi, N.M.; Yau, E.K.B.; Lin, L.J. Ultra Brief Psychological Interventions for COVID-19 Pandemic: Introduction of a Locally-Adapted Brief Intervention for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Service. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 27, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Singh, A.K.; Mishra, S.; Chinnadurai, A.; Mitra, A.; Bakshi, O. Mental health implications of COVID-19 pandemic and its response in India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, F.; Hua, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J. Development of a psychological first-aid model in inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Gen. Psychiatr. 2020, 33, e100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, R.; Yang, L.; Tang, Z.; Chen, T. Caring for patients in mental health services during COVID-19 outbreak in China. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Zhong, H.; Jiang, M.; Zeng, K.; Zhong, B.; Liu, L.; Liu, X. Emergency response strategy for containing COVID-19 within a psychiatric specialty hospital in the epicenter of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Hashimoto, K.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H. Knowledge and attitudes of medical staff in Chinese psychiatric hospitals regarding COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 4, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, X.H.; Zhao, N.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: Managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1741–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kavoor, A.R.; Chakravarthy, K.; John, T. Remote consultations in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary experience in a regional Australian public acute mental health care setting. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 51, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Murnane, T.; Kumar, S.; Rolfe, T.; Dimitrieski, S.; McKeown, M.; Ejareh Dar, M.; Gavson, L.; Gandhi, C. Making working from home work: Reflections on adapting to change. Australas. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, J.C.; Allison, S.; Bastiampillai, T.; Pring, W. Private practice metropolitan telepsychiatry in larger Australian states during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of the first 2 months of new MBS telehealth item psychiatrist services. Australas. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marehin, M.S.; Mboumba Hinnouo, A.; Obiang, P.A. Organisation of psychiatric care in Gabon during the COVID-19 epidemic. Ann. Med. Psychol. 2021, 179, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, O.B.; Turan, B.; Pakyürek, M.; Tekin, A. Integrating Telepsychiatric Services into the Conventional Systems for Psychiatric Support to Health Care Workers and Their Children During COVID-19 Pandemics: Results from A National Experience. Telemed. J. E Health 2021, 27, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, G.; Kelly, B.D. Domestic violence against women and the COVID-19 pandemic: What is the role of psychiatry? Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2020, 71, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anmella, G.; Arbelo, N.; Fico, G.; Murru, A.; Llach, C.D.; Madero, S.; Gomes-da-Costa, S.; Imaz, M.L.; López-Pelayo, H.; Vieta, E.; et al. COVID-19 inpatients with psychiatric disorders: Real-world clinical recommendations from an expert team in consultation-liaison psychiatry. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanella, S.; Arikan, K.; Babiloni, C.; Balconi, M.; Bertollo, M.; Betti, V.; Bianchi, L.; Brunovsky, M.; Buttinelli, C.; Comani, S.; et al. Special Report on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Clinical EEG and Research and Consensus Recommendations for the Safe Use of EEG. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2021, 52, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, J.; Crews, M. Rehabilitation During a Pandemic: Psychiatrists as First Responders? J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hayek, S.; Cheaito, M.A.; Nofal, M.; Abdelrahman, D.; Adra, A.; Al Shamli, S.; AlHarthi, M.; AlNuaimi, N.; Aroui, C.; Bensid, L.; et al. Geriatric Mental Health and COVID-19: An Eye-Opener to the Situation of the Arab Countries in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, J.; Roche, E.; Kamali, M.; Feeney, L. COVID-19 from the perspective of urban and rural general adult mental health services. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thome, J.; Coogan, A.N.; Simon, F.; Fischer, M.; Tucha, O.; Faltraco, F.; Marazziti, D.; Butzer, H. The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the medico-legal and human rights of psychiatric patients. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, E.; Crommelinck, B.; Decker, M.; Doeraene, S.; Kaisin, P.; Lallemand, B.; Noël, C.; Van Ypersele, D. Impacts de la crise du Covid-19 sur un hôpital psychiatrique pour enfants et adolescents. Cah. Crit. de Thérapie Fam. Et de Prat. de Réseaux 2020, 65, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignon, B.; Gourevitch, R.; Tebeka, S.; Dubertret, C.; Cardot, H.; Dauriac-Le Masson, V.; Trebalag, A.K.; Barruel, D.; Yon, L.; Hemery, F.; et al. Dramatic reduction of psychiatric emergency consultations during lockdown linked to COVID-19 in Paris and suburbs. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russ, M.J.; Sisti, D.; Wilner, P.J. When patients refuse COVID-19 testing, quarantine, and social distancing in inpatient psychiatry: Clinical and ethical challenges. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 46, 579–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).