Abstract

Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging (RUSI) is used by physical therapists as a feedback tool for measuring changes in muscle morphology during therapeutic interventions such as motor control exercises (MCE). However, a structured overview of its efficacy is lacking. We aimed to systematically review the efficacy of RUSI for improving MCE programs compared with no feedback and other feedback methods. MEDLINE, PubMed, SCOPUS and Web of Science databases were searched for studies evaluating efficacy data of RUSI to improve muscular morphology, quality, and/or function of skeletal muscles and MCE success. Eleven studies analyzing RUSI feedback during MCE were included. Most studies showed acceptable methodological quality. Seven studies assessed abdominal wall muscles, one assessed pelvic floor muscles, one serratus anterior muscle, and two lumbar multifidi. Eight studies involved healthy subjects and three studies clinical populations. Eight studies assessed muscle thickness and pressure differences during MCE, two assessed the number of trials needed to successfully perform MCE, three assessed the retain success, seven assessed the muscle activity with electromyography and one assessed clinical severity outcomes. Visual RUSI feedback seems to be more effective than tactile and/or verbal biofeedback for improving MCE performance and retention success, but no differences with pressure unit biofeedback were found.

1. Introduction

Motor control exercise (MCE) consists of an exercise-based intervention focused on the activation of deep muscles to improve the control and coordination of these muscles [1]. MCE is widely used since evidence suggests improvements in pain, function, self-perceived recovery and quality of life up to 12 weeks [1]. Several mechanisms, including the lack of stability of the spine, impaired motor control and/or muscle activity patterns, or disturbed proprioception and restricted range of motion, have been proposed for explaining non-specific spine pain [2]. Motor control exercises aim to restore muscular coordination, control and capacity by training isolated contractions of deep trunk muscles while maintaining a normal breathing and progressing to pre-activate and maintain the contraction during dynamic and functional tasks [3]. Given the difficulty that some patients can perceive during MCE, these exercises are usually performed in supervised sessions providing biofeedback on the activation of trunk muscles for facilitating the awareness and control of these deep muscles’ isolated contractions [4].

According to the definition provided by Blumenstein et al. [5], biofeedback refers to external psychological, physical, or augmented proprioceptive feedback that is used to increase an individual’s cognition of what is occurring physiologically in the body. Although several modalities are described in the literature (e.g., electroencephalography, skin resistance, electrocardiography, sphygmomanometry, strain-gauge devices, thermal feedback), the most used biofeedback modalities include ultrasound imaging, pressure biofeedback units and electromyography.

Ultrasound imaging (US) is a fast, easy, safe, noninvasive and low-cost real-time method frequently used for assessing muscle morphology (e.g., thickness, cross-sectional area and volume) [6], quality (e.g., echo-intensity and fatty infiltration) [7] and function [8]. This method allows both patients and clinicians to see in real time muscle morphology changes, since this is sensitive to positive and negative changes and therefore is valid for measuring trunk muscle activation during isometric submaximal contractions [9].

Surface electromyography, which consists of placing surface electrodes to detect changes in skeletal muscle activity for providing to the patient a visual or auditory signal for either increasing or reducing muscle activity, is also used as a biofeedback method in rehabilitation [10,11]. However, surface EMG cannot be used for assessing deep muscles and needle electrodes are needed [12].

Finally, pressure biofeedback units are also commonly used since they are economic and easy to apply in a clinical setting. This instrument consists of an inflatable cushion which is connected to a pressure gage, which displays feedback on muscle activity [13].

Since the last systematic review assessing the efficacy of Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging (RUSI) for enhancing the performance and contraction endurance of skeletal muscles during MCE was published more than 10 years ago and new evidence is available [14], an updated systematic review is needed. Thus, although a previous review by Giggins et al. [15] reviewed the biofeedback therapies used in rehabilitation, RUSI was not compared with others biofeedback methods nor without feedback. Therefore, the current systematic review evaluates the efficacy of RUSI to improve muscle function during CME compared with no feedback and other feedback methods in both healthy subjects and patients with musculoskeletal pain conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [16]. The international OPS Registry registration link is https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/CNGW4 (accessed on 15 February 2021).

2.2. Data Sources

Since a minimum of three databases are needed for adequate systematic reviews [17], we conducted a search in the following electronic literature: MEDLINE, PubMed, SCOPUS and Web of Science databases from their inception to 18 February 2021. Search strategies were conducted with the assistance of an experienced health science librarian and following the guidelines described by Greenhalgh [18]. Search strategies were based on a combination of MeSH terms and key words following the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) question:

Population: Adults (older than 18 years old) with or without musculoskeletal pain disease.

Intervention: Use of real-time ultrasound imaging as visual biofeedback during MCE to facilitate the MCE performance or retention success.

Comparator: No biofeedback or other biofeedback method.

Outcomes: Improvements in muscular function as assessed with imaging methods (US, magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography) or EMG.

An example of the search strategy (PubMed database) was as follows:

| Filters: [Title/Abstract] |

| #1 Ultrasonography [Mesh]: #2 Ultrasound; #3 Echography; #4 Sonography |

| #5 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 |

| #6 Exercise Therapy [Mesh]: #7 Motor control; #8 Stabilization exercise; #9 Rehabilitation Exercise |

| #10 #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 |

| #11 Feedback, Sensory [Mesh]: #12 Biofeedback; #13 Visual Feedback; # 14 Audio Feedback; #15 Proprioceptive Feedback; #16 Sensorimotor Feedback |

| #17 #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 |

| # 18 Muscle, Skeletal [Mesh] |

| #19 #5 AND #10 AND #17 AND #18 |

2.3. Study Eligibility Criteria

Experimental studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) evaluated the efficacy of RUSI as visual feedback compared with any other feedback method; (2) used of RUSI for improving muscle function (either as performance or retaining success) of skeletal muscles; (3) included healthy subjects or symptomatic populations, and, (4) were published in English language. Animal studies, observational studies, descriptive studies, review studies, cadaveric studies, published proceedings, and abstracts were excluded.

2.4. Study Appraisal and Synthesis Methods

The Mendeley Desktop v.1.19.4 for Mac OS (Glyph & Cog, LLC 2008) program was used to insert the search hits from the databases. First, those duplicated studies were removed. Second, title and abstracts of the articles were screened for potential eligibility by two reviewers. Third, the full text was analyzed to identify potentially eligible studies. Both reviewers were required to achieve a consensus. If the consensus was not reached, a third reviewer participated in the process to reach the agreement for including or not including the study. A standardized data extraction form containing questions on sample population, methodology (intervention, comparator, tasks and muscle assessed), outcomes and results was used, according to the STARLITE guideline [19].

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the PEDro scale [20]. This scale is used to assess the methodological quality of trials and consists of 11 items. The first item (not included in the total score) relates to external validity and the following 10 are used to calculate the final score evaluating the following features: random allocation, concealed allocation, similarity at baseline, subject blinding, therapist blinding, assessor blinding, lost follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, between-group statistical comparison, and point and variability measures for at least one key outcome. Total PEDro scores between 0 and 3 are considered “poor”, 4 and 5 as “fair”, 6 and 8 as “good”, and 9 and 10 as “excellent” [20].

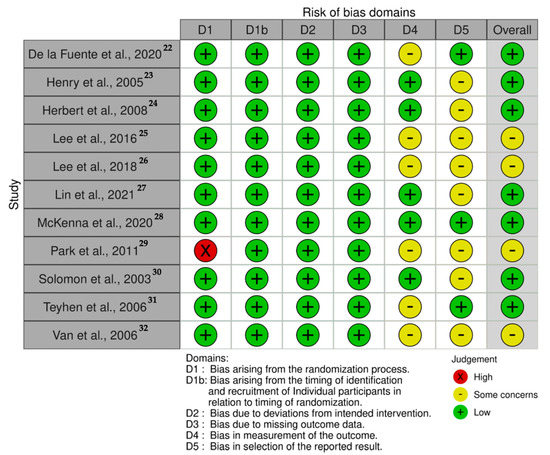

Finally, a risk of bias analysis for each study was conducted as recommended for systematic reviews [16]. The RoB 2 tool was used to identify the risk of bias in 5 domains: (1) bias due to randomization; (2) bias due to deviations from intended intervention; (3) bias due to missing data; (4) bias due to outcome measurement; and (5) bias due to selection of the reported result [21].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The results of the search and selection process (identification, screening, eligibility and analyzed) from the 1084 studies identified in the search to the 11 studies included in the review [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] are described in the flow diagram shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart.

3.2. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

The methodological quality scores ranged from 4 to 9 (mean: 6.4, SD: 1.4) out of a maximum of 10 points (Table 1). The most consistent flaws were lack of participants (all studies) and therapist blinding (ten studies), concealed allocation (just five studies considered a concealed allocation) and providing point measures and measures of variability (eight studies).

Table 1.

Methodological quality assessment of the included studies.

The risk of bias analysis is described in Figure 2. Seven studies showed an overall low risk of bias [22,23,24,27,28,30,31]. However, four studies presented some concerns regarding the measurement of the outcomes and the reported results which should be considered on data interpretation [25,26,29,32].

Figure 2.

Risk of bias traffic-light plot.

3.3. Data Analysis

Table 2 summarizes the studies included in this systematic review investigating the efficacy of RUSI as biofeedback tool during MCE. The included studies compared RUSI visual feedback against verbal (n = 8) [22,23,25,26,27,29,31,32], tactile (n = 5) [23,25,28,30,31] and pressure unit (n = 2) [25,30] feedback. Further, one study evaluated different modalities of RUSI visual feedback (constant versus variable) [24].

Table 2.

Data of the studies investigating RUSI as the biofeedback method for MCE.

Most studies assessed the deep abdominal wall musculature (including Transversus Abdominis -TrA- [22,23,25,26,27,29,31], Internal Oblique -IO- [23,25,26,29,31] and External Oblique -EO- [23,25,26,29,31]). Although procedures were not consistent (e.g., postures, measurement timing, resting between series, number of series, etc.), all studies assessing the abdominal wall muscles used the Abdominal Hollowing Exercise -AHE- [22,23,25,26,27,28,31]. In addition, pelvic floor muscles [30], serratus anterior [28] and lumbar multifidus -LM- [24,27,31] were also analyzed.

The included studies reported different outcomes since seven assessed changes in muscle thickness and/or pressure between MCE and rest [22,25,26,27,29,30,31,32], number of repetitions needed to correctly perform the MCE [22,23], ability to retain the correct MCE performance [23,24,31], muscle electromyographic activity [22,25,26,27,29,30,32], and clinical outcomes [30].

Regarding the populations included in the studies, most of them included healthy subjects [22,23,24,25,26,27,29,32] and just three studies included clinical populations, one study included patients with mild-to-moderate fecal incontinence [30], one study included patients with unilateral subacromial pain [28], and one study included patients with chronic low back pain [31]. In general, RUSI visual feedback was a more effective feedback tool than verbal feedback or single manual facilitation for most of the outcomes assessed (e.g., number of repetitions needed to perform correctly the MCE, muscle thickness, or electromyographic activity) considering that procedures were not consistent between studies. However, it seems equally effective as pressure biofeedback units.

4. Discussion

This systematic review found that RUSI applied as a visual biofeedback tool during MCE seems to be more effective for increasing muscle thickness, muscle activity and target exercise success when compared with verbal or tactile biofeedback. However, the results analyzed from the included studies suggest no additional benefit using RUSI when compared with pressure unit biofeedback. The studies included showed consistent flaws regarding their methodological quality, e.g., participant and therapist blinding, concealed allocation, point measures and measures of variability, which should be addressed in future studies.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, the last systematic review assessing the efficacy of RUSI for enhancing the performance and contraction endurance of skeletal muscles during MCE was published in 2007 and, therefore, findings from more recent evidence have not been previously updated [14]. Although our initial aim was to assess how RUSI could improve muscle function, muscular morphology, quality and/or function of skeletal muscles, most of the studies included healthy populations with neither decreased muscle quality nor decreased function. Therefore, although two studies included clinical pain populations, we cannot make definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of RUSI for improving the mentioned outcomes.

Different comparative biofeedback methods were considered in studies included in this systematic review. Most of the studies included a common clinical biofeedback group (verbal biofeedback and/or tactile feedback) [22,23,25,26,27,29,31,32] and results seem to be consistent between trials. Comparative analyses showed larger changes in thickness [22,25,26,27,29,31,32], greater success for exercise performance (greater success ratio and lower number of trials to reach the first successful MCE performance) [23] and greater electromyographic activity [28] for the RUSI biofeedback groups, but no differences for MCE retention at short-term [23]. In the study conducted by Herbert et al. [24], constant (receiving real-time RUSI of successful or unsuccessful muscle activation on the monitor, but without verbal feedback) and variable (receiving delayed feedback after performing the exercise) RUSI feedback were compared. Although both methods sustained the MCE performance success at short-term, the constant feedback group showed superior motor learning at long-term.

Visual RUSI feedback was compared with pressure unit feedback in two studies [25,30]. The results seem to be consistent since Lee et al. [25] found that pressure unit feedback showed no differences for increasing muscle thickness compared with visual RUSI feedback and Solomon et al. [30] found similar improvements in MCE compliance, strength and clinical outcomes. Surprisingly, none of the studies included in this review compared RUSI feedback with other feedback methods (e.g., electromyography or sensitive stimulus). Although this study conducted by Vera et al. [4] was excluded since full-text is not available, their results showed no differences in muscular thickness change with or without sensitive electrical stimulation in addition to the visual RUSI biofeedback.

Although current evidence strongly supports the presence of motor control adaptations in patients with low back pain (LBP), including altered activation timings, lumbopelvic coordination, balance control and kinematics [32], and since MCE is a common form of exercise for LBP management, surprisingly we only identified two studies investigating the efficacy of RUSI in clinical populations (unilateral subacromial pain [28] and fecal incontinence [30]), but none included patients with LBP. Healthy population studies are not enough to conclude that visual RUSI biofeedback would obtain similar improvements in LBP populations for facilitating or improving muscular activity since these populations show brain plastic changes of the trunk musculature representation area [33], indicating less fine control [34]. It should be considered that, although MCE is an effective treatment for non-specific LBP, specially indicated for sub-clinical intermediate pain and middle-aged patients [35], low-to-moderate quality evidence showed no additional benefit over spinal manipulative therapy, other forms of exercise or medical treatment in decreasing pain and disability [36,37,38]. Therefore, future clinical trials should include clinical populations for assessing the efficacy of visual RUSI biofeedback for facilitating MCE comprehension, performance and retainment compared with other biofeedback methods.

Finally, there are some limitations of the current systematic review. First, we have only included articles written in English; so, we may have missed some relevant studies published in other languages. Furthermore, we did not include those studies which were unpublished. Secondly, due to the variability of the MCE procedures and in the outcomes, a meta-analysis could not be conducted.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review found that visual RUSI biofeedback is more effective than common tactile and/or verbal biofeedback for improving MCE performance and retention success in healthy people. There were no clinically important differences between RUSI and pressure unit biofeedback. More high-quality studies with consistent procedures and clinical populations are needed to confirm these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.V.-C., J.L.A.-B. and R.O.-S.; methodology, J.A.V.-C., U.V. and G.M.G.-S.; formal analysis, J.A.V.-C. and C.F.-d.-l.-P.; investigation, J.A.V.-C., J.L.A.-B. and R.O.-S.; data curation, J.A.V.-C. and U.V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.V.-C.; writing—review and editing, C.F.-d.-l.-P. and U.V.; supervision, J.A.V.-C.; project administration, G.M.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (J.A.V.-C.), upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Saragiotto, B.T.; Maher, C.; Yamato, T.; Costa, L.; Costa, L.D.C.M.; Ostelo, R.; Macedo, L. Motor control exercise for chronic non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, C.; Hänsel, F. Chronic Non-specific Low Back Pain and Motor Control during Gait. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederer, D.; Mueller, J. Sustainability effects of motor control stabilisation exercises on pain and function in chronic nonspecific low back pain patients: A systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, D.M.; Calero, J.A.V.; Manzano, G.P.; Casas, P.M.; Martín, D.P.; Izquierdo, T.G. C0065 Different feedback methods to improve lumbar multifidus contraction. Br. J. Sprots Med. 2018, 52, A15–A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstein, B.; Bar-Eli, M.; Tenenbaum, G. Biofeedback Applications in Performance Enhancement: Brain and Body in Sport and Exercise; John Wiley & Sons: Sussex, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Valera-Calero, J.A.; Ojedo-Martín, C.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Cleland, J.A.; Arias-Buría, J.L.; Hervás-Pérez, J.P. Reliability and Validity of Panoramic Ultrasound Imaging for Evaluating Muscular Quality and Morphology: A Systematic Review. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valera-Calero, J.A.; Arias-Buría, J.L.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Cleland, J.A.; Gallego-Sendarrubias, G.M.; Cimadevilla-Fernández-Pola, E. Echo-intensity and fatty infiltration ultrasound imaging measurement of cervical multifidus and short rotators in healthy people: A reliability study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2021, 53, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J.L.; Ellis, R.; Hodges, P.W.; Osullivan, C.; Hides, J.; Carnero, S.F.; Arias-Buria, J.L.; Teyhen, D.S.; Stokes, M.J. Imaging with ultrasound in physical therapy: What is the PT’s scope of practice? A competency-based educational model and training recommendations. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenhaver, S.L.; Hebert, J.; Parent, E.C.; Fritz, J.M. Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging is a valid measure of trunk muscle size and activation during most isometric sub-maximal contractions: A systematic review. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Deckers, K.; Eldabe, S.; Kiesel, K.; Gilligan, C.; Vieceli, J.; Crosby, P. Muscle Control and Non-specific Chronic Low Back Pain. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2017, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblett, R. Surface Electromyographic (SEMG) Biofeedback for Chronic Low Back Pain. Healthcare 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, I.A.; Henry, S.M.; Single, R.M. Surface EMG electrodes do not accurately record from lumbar multifidus muscles. Clin. Biomech. 2003, 18, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasto, C.F.B.; Montes, A.M.; Carvalho, P.; Carral, J.M.C. Pressure biofeedback unit to assess and train lumbopelvic stability in supine individuals with chronic low back pain. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2019, 31, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, S.M.; Teyhen, D.S. Ultrasound Imaging as a Feedback Tool in the Rehabilitation of Trunk Muscle Dysfunction for People with Low Back Pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2007, 37, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giggins, O.M.; Persson, U.M.; Caulfield, B. Biofeedback in rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2013, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhammi, I.K.; Haq, R.U. How to write systematic review or meta-analysis. Indian J. Orthop. 2018, 52, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T. How to read a paper: The Medline database. BMJ 1997, 315, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booths, A. Brimful of STARLITE: Toward standards for reporting literature searches. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2006, 94, 421–430. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M.R.; Van der Wees, P.J.; Pinheiro, M.B. Using research to guide practice: The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, C.; Silvestre, R.; Baechler, P.; Gemigniani, A.; Grunewaldt, K.; Vassiliu, M.; Wodehouse, V.; Delgado, M.; Carpes, F.P. Intrasession Real-time Ultrasonography Feedback Improves the Quality of Transverse Abdominis Contraction. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2020, 43, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.M.; Westervelt, K.C. The Use of Real-Time Ultrasound Feedback in Teaching Abdominal Hollowing Exercises to Healthy Subjects. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2005, 35, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, W.J.; Heiss, D.G.; Basso, D.M. Influence of Feedback Schedule in Motor Performance and Learning of a Lumbar Multifidus Muscle Task Using Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Phys. Ther. 2008, 88, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Han, S.; Lee, D. Comparison of abdominal muscle thickness according to feedback method used during abdominal hollowing exercise. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 2519–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lee, D.H.; Hong, S.K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Hwang, J.-M.; Lee, Z.; Kim, J.M.; Park, D. Is abdominal hollowing exercise using real-time ultrasound imaging feedback helpful for selective strengthening of the transversus abdominis muscle? Medicine 2018, 97, e11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, G.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, C. Effect of real-time ultrasound imaging for biofeedback on trunk muscle contraction in healthy subjects: A preliminary study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, L.J.; Bonnett, L.; Panzich, K.; Lim, J.; Hansen, S.K.; Graves, A.; Jacques, A.; Williams, A.S. The Addition of Real-time Ultrasound Visual Feedback to Manual Facilitation Increases Serratus Anterior Activation in Adults with Painful Shoulders: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Phys. Ther. 2021, 17, pzaa208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Lee, H. The Use of Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging for Feedback from the Abdominal Muscles during Abdominal Hollowing in Different Positions. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2011, 23, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Solomon, M.; Pager, C.K.; Rex, J.; Roberts, R.; Manning, J. Randomized, Controlled Trial of Biofeedback with Anal Manometry, Transanal Ultrasound, or Pelvic Floor Retraining with Digital Guidance Alone in the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Fecal Incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2003, 46, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyhen, D.S.; Miltenberger, C.E.; Deiters, H.M.; Del Toro, Y.M.; Pulliam, J.N.; Childs, J.D.; Boyles, R.E.; Flynn, T.W. The Use of Ultrasound Imaging of the Abdominal Drawing-in Maneuver in Subjects with Low Back Pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2005, 35, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, K.; Hides, J.; Richardson, C.A. The Use of Real-Time Ultrasound Imaging for Biofeedback of Lumbar Multifidus Muscle Contraction in Healthy Subjects. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2006, 36, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.L.; Vrana, A.; Schweinhardt, P. Low Back Pain: The Potential Contribution of Supraspinal Motor Control and Proprioception. Neuroscientist 2019, 25, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, H.; Danneels, L.A.; Hodges, P.W. ISSLS prize winner: Smudging the motor brain in young adults with recurrent low back pain. Spine 2011, 36, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederer, D.; Engel, T.; Vogt, L.; Arampatzis, A.; Banzer, W.; Beck, H.; Catalá, M.M.; Brenner-Fliesser, M.; Güthoff, C.; Haag, T.; et al. Motor Control Stabilisation Exercise for Patients with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Prospective Meta-Analysis with Multilevel Meta-Regressions on Intervention Effects. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, P.J.; Miller, C.T.; Mundell, N.L.; Verswijveren, S.J.J.M.; Tagliaferri, S.D.; Brisby, H.; Bowe, S.J.; Belavy, D.L. Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragiotto, B.; Maher, C.; Yamato, T.; Costa, L.; Costa, L.D.C.M.; Ostelo, R.; Macedo, L. Motor Control Exercise for Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Spine 2016, 41, 1284–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, L.G.; Saragiotto, B.T.; Yamato, T.P.; Costa, L.O.; Menezes Costa, L.C.; Ostelo, R.W.; Maher, C.G. Motor control exercise for acute non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD012085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).