Abstract

There is evidence that sex- and gender-related factors are involved in cannabis patterns of use, health effects and biological mechanisms. Women and men report different cannabis use disorder (CUD) symptoms, with women reporting worse withdrawal symptoms than men. The objective of this systematic review was to examine the effectiveness of cannabis pharmacological interventions for women and men and the uptake of sex- and gender-based analysis in the included studies. Two reviewers performed the full-paper screening, and data was extracted by one researcher. The search yielded 6098 unique records—of which, 68 were full-paper screened. Four articles met the eligibility criteria for inclusion. From the randomized clinical studies of pharmacological interventions, few studies report sex-disaggregated outcomes for women and men. Despite emergent evidence showing the influence of sex and gender factors in cannabis research, sex-disaggregated outcomes in pharmacological interventions is lacking. Sex- and gender-based analysis is incipient in the included articles. Future research should explore more comprehensive inclusion of sex- and gender-related aspects in pharmacological treatments for CUD.

1. Introduction

Growing evidence related to the importance of sex- and gender-based factors within health research has led to increased interest among researchers, funding agencies, scientific journals and database creators to find innovative ways of examining these factors in previously unexplored areas [1,2,3]. The integration of sex- and gender-related factors into research, policy, or health programs revisits or identifies the influence of components such as anatomy, physiology, genetics and other bodily characteristics biological (sex-based) and the social and cultural milieu affecting humans socio-cultural (gender-based) is known as sex- and gender-based analysis (SGBA) [4]. Sex and gender are not independent of other social characteristics and they might interact with each other and other characteristics to influence health outcomes [5].

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) provide the strongest research evidence and are often used to test the efficacy of new pharmacological interventions. However, sex- and gender-based analysis in RCTs is very scarce. For example, in a study that analyzed 100 Canadian-led or funded RCTs, Welch et al. found that 98% of studies included sex in the description of sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, while only 6% conducted a subgroup analysis across sex, and only 4% reported sex-disaggregated data. None of the examined articles included a definition of “sex” or “gender” nor a comprehensive sex- and gender-based analysis [6]. Failing to include a sex- and gender-based analysis of the outcomes might have important and serious clinical consequences for individuals or subgroups of patients.

There are differences between women and men in referrals and pathways to substance use treatment in general. For example, women are less likely to be referred to residential treatment than men [7]; women are more likely to be referred to outpatient treatment vs. residential treatment [7,8]. Women tend to access substance use services via primary health care or mental health services vs. specialty substance use treatment services [8,9], while men are more likely to enter treatment via the criminal justice system [10]. Lack of awareness of options, stigma, confrontational treatment models, and lack of childcare are some of the common barriers encountered by women when accessing treatments for substance use [9]. Women tend to enter treatment with a more severe clinical profile and more problems related to mental health, family, interpersonal relationships, and physical health [9,10,11,12]; while men have more legal, criminal, and financial problems [13].

There are also differences in response to treatment for other substance use. For example, evidence derived using a sex- and gender-based analysis reveals that women have additional difficulties in tobacco smoking cessation. Women have poorer smoking cessation outcomes with some pharmacological supports, including nicotine replacement therapy, regardless of whether combined with counselling [14]; and buproprion [15]. In contrast, treatment with varenicline has shown similar, or better, outcomes for women compared to men [16,17,18]. Women tend to require more smoking quit attempts before achieving cessation. While women report lower quit rates, the use of any medication increases women’s likelihood of cessation [19].

Women and men receiving treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD) report similar rates in reductions and/or abstinence from alcohol, including medical management and behavioral counselling for AUD [20]; treatment with the medication acamprosate (based on a meta-analysis) [21]; and residential treatment [22]. Studies on the effectiveness of naltrexone treatment for AUD treatment are mixed, with some studies reporting similar outcomes for women and men [22,23], and others reporting a greater reduction in craving scores for women [24], or greater reductions in alcohol use (and other substance use) in men [25]. The limited evidence examining sex differences in treatment outcomes for opioid use disorder (OUD) have reported similar improvements in opioid use outcomes for women and men following a medical management intervention (tapering with buprenorphine–naloxone) either alone or combined with counselling [26].

2. Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis in Cannabis Research

There is growing evidence that sex- and gender-related factors are involved in cannabis patterns of use, health effects and biological mechanisms. Men and boys are more likely to initiate cannabis use earlier, and use more frequently and in greater quantities, compared to women and girls. However, the gender gap has been narrowing over time [27,28]. For example, an analysis of US trends in adolescent cannabis use from 1999 to 2009 revealed that in 1999, 51% of boys and 43.4% of girls reported lifetime cannabis use, while in 2013, this decreased to 42.1% for boys and 39.2% for girls [27]. Furthermore, sex and gender factors also intersect with factors such as education and cultural context. Evidence suggests that the diffusion of cannabis experimentation among men appears similar to that observed with tobacco, with use beginning among men and the most educated groups first, in countries such as USA and Germany. In France, cannabis experimentation continues to be more prevalent among women with higher education [28].

Not everyone who uses cannabis transitions to cannabis use disorder (CUD). It is estimated that approximately 9% of those who initiate cannabis use will meet the criteria for cannabis use dependence. Those who initiate during adolescence have an increased likelihood (16.6%) of developing CUD [29,30]. Multiple factors have been associated with cannabis use disorder in women and men. Specifically, both frequency of use and form of cannabis used have been associated with CUD. Among females, cannabis use with strangers was more strongly related to being diagnosed with CUD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) compared to males [31]. Compared to women, men have a younger age of onset for CUD [32]. Polysubstance use, trauma and violence may also be risk factors for CUD. In a US study, sexual abuse and history of alcohol use disorder were more strongly associated with 12 month CUD among females, compared to males [33]. Men with lifetime CUD were more likely than women to be diagnosed with any psychiatric disorder, any substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder, whereas women with CUD had more mood and anxiety disorders [34].

Similar to other substance use, there is some evidence that females transition more quickly to cannabis use dependence compared to males. Studies found that women demonstrate a “telescoping effect”, meaning a shorter duration from onset of cannabis use to onset of CUD [34,35,36]. In a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population, there were no gender differences in the age at first or heavy cannabis use, age at onset of CUD, total number of episodes of cannabis abuse or dependence, or in the number of criteria met for cannabis dependence. However, the time from age at first use of cannabis to the age at onset of the CUD was shorter among women [34].

The results of studies on the subjective effects of cannabis are mixed, and seem to depend on the dose, route of administration (oral vs. smoked) and population (e.g., user vs. non user) [37]. After inhaling tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), women rated themselves as “higher” than men [38]; and reported higher ratings of cannabis as “good” and desire to “take again” compared to men [39]. Another study demonstrated women were more likely to describe cannabis as “good” at low doses, while men more likely to report the same at high doses [40]. In animal studies, female rats exhibit greater drug seeking behavior. In one study that primed rats for drug use and cues before a period of absence, females exhibited higher baseline cannabis intake during training, and reinstate responding for the cannabinoid at higher levels than males [41].

Finally, women and men report different CUD symptoms. For example, several studies report that women have worse withdrawal symptoms compared to men mostly related to gastrointestinal and mood symptoms [42,43,44,45]. Men are more likely than women to report experiencing insomnia and vivid dreams as withdrawal symptoms [45]. These findings have important implications since withdrawal symptoms correlate with relapse [46]. Moreover, in a sample of treatment-seeking adults with cannabis use disorder, women reported more co-occurring mental health issues (including lifetime panic disorder and current agoraphobia), and more days of poor physical health [45]. Although CUD is associated with poorer mental health and quality of life in both women and men, this pattern is more pronounced in women with CUD [47]. Animal studies also illustrate the impact of sex-related factors on withdrawal symptoms. Several studies show that females have slightly greater withdrawal symptoms than males [48]. After a week of daily THC treatment in Sprague–Dawley rats, Harte-Hargrove et al. observed the presence of locomotor depression in females but not males during the abstinence period [49].

3. Objective of the Present Study

This systematic review draws on a much broader scoping review on sex- and gender-related factors in substance use (initiation/uptake, patterns of use), effects, and prevention, treatment or harm reduction outcomes for four substances (opioids, alcohol, tobacco/nicotine and cannabis use). It also examined harm reduction, health promotion/prevention and treatment interventions and programs that include sex, gender and gender transformative elements to address each of the four substances. The methodology of the scoping review is described in full elsewhere [50].

Despite the evidence regarding sex and gender differences in, and impacts of cannabis use, little is known about sex- and gender-related factors in pharmacological interventions for cannabis dependence. Pharmacological interventions for cannabis dependence have been recently reviewed [51,52], but sex and gender factors have not been closely examined. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the effects of sex and gender factors in cannabis pharmacological interventions.

Our initial research question was:

What cannabis pharmacological interventions are available that include sex, gender and gender transformative elements and how effective are these in addressing cannabis use?

After examining the results of the original scoping review and realizing that there is a lack of examination of sex and gender factors in substance use interventions, and more specifically in cannabis pharmacological interventions, we decided to analyze the studies on cannabis pharmacological interventions that included women and men and sex-disaggregated the outcomes of the interventions for both sexes. In addition, we assessed the role of sex- and gender-based analysis in the included studies.

The research question was then updated to:

What cannabis pharmacological interventions are available that include both sexes and how effective are these in addressing cannabis use for women and men?

4. Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [53].

4.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was undertaken to identify relevant studies published in English between 2007 and 2019 (up to fourth week of October). The following databases were used: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Embase. The search strategy was developed based on keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. We based our search strategy on the search strategy developed for the scoping review [50] and, in addition, we also included more keywords relevant to pharmacological interventions such as “drug therapy”, “pharmacotherapy”, “pharmacology”, “cessation”, “addiction treatment” that were not included in the previous scoping review. An additional search was also completed from a recent systematic review on cannabis pharmacological interventions. Thirty-eight articles were included for the screening in this systematic review.

4.2. Literature Screening

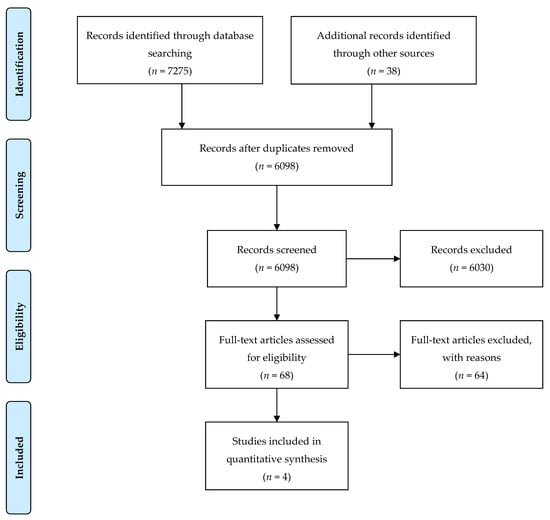

Searches in four databases resulted in n = 6098 unique returns. Firstly, titles and abstracts were screened by a single reviewer for relevance. Then, the full-text of the articles were obtained and reviewed by two reviewers according to the inclusion criteria. These inclusion criteria were: (a) English language articles from a selection of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries such as Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States; (b) the population of interest included: women, girls, men, boys of all ages and sociodemographic characteristics; (c) studies including pharmacotherapies that targeted cannabis use (in addition to other comorbid conditions) and presented sex-disaggregated data; (d) studies that analyzed outcomes such as cannabis abstinence or cannabis reduction; (e) randomized clinical trials. Articles were excluded if: (a) although both women and men were included in the study, outcomes of the interventions were not sex-disaggregated; (b) the study did not examine a pharmacological intervention aiming to modify cannabis use; (c) studies were conducted in a non-OECD country; (d) studies analyzed baseline characteristics of the population but the analyses are not done in relationship to the pharmacological treatment. Figure 1 provides an overview of the literature search returns, the number of articles included and excluded at each level of screening, and the final number of included articles.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram of study selection.

4.3. Study Selection

The abstract screening was conducted by a single reviewer. Full papers of the included studies at this stage (n = 68) were then retrieved and assessed by two independent reviewers. Inter-rater reliability was calculated, and the overall kappa was 0.78. Differences between the reviewers in the inclusion of articles were resolved through discussion and consensus was reached.

4.4. Data Extraction

Data regarding the following information was extracted by one reviewer from the four papers included in this systematic review: (1) study details (authors and year of publication); (2) aim of the study; (3) study design; (4) country of study; (5) setting of the study; (6) details on recruitment; (7) inclusion and exclusion criteria; (8) method of allocation to intervention/control; (9) details regarding the intervention; (10) sample size and demographics; (11) baseline comparisons; (12) outcomes; (13) details on the sex, gender or diversity analysis; (14) follow up periods; (15) methods of analysis; (16) results; (17) results regarding the sex, gender or diversity based factors in findings; (18) attrition details; (19) study limitations; (20) evidence gaps and/or recommendations for future research.

4.5. Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis in the Included Studies

Research can incorporate sex- and gender-based analysis in several ways. Hammarström presented a tool that researchers might use when developing gender research [54]. Although Hammarström [54] does not employ the term “sex- and gender-based analysis”, in this paper we used the concept sex- and gender-based analysis as in the scoping review conducted by McCarthy et al. [55]. The authors reviewed 458 articles on pharmacy practice research and found that only six studies mention any information related to sex and gender considerations and only three were classified as SGBA according to Hammarström’s model [55]. Table 1 presents the classification based on Hammarström’s typology [54]. For the sex- and gender-based analysis of the included articles, we examined the following characteristics:

Table 1.

Sex- and gender-based analysis in health research.

- Use of sex and gender in the aim and research questions: were sex and gender included in the aim of the study or explicitly mentioned in the research question and the study design?

- Study design and reporting results: how were the outcomes analyzed and reported in relation to sex and gender?

- Interpretation of sex/gender findings: how were findings related to sex and gender included in the interpretation of the data?

- Intentional and accurate use of language: were the terms sex and gender used intentionally and appropriately by the authors of the study?

5. Results

5.1. Included Studies

Four randomized controlled trials involving 623 participants met the inclusion criteria for this review [56,57,58,59]. Characteristics of the studies are described in Table 2. In total, 316 participants received the intervention while 307 participants received placebo. The number of women included in the studies oscillated between 16 [58] and 86 [57]. Disaggregating by sex, 170 women and 453 men were included in the randomized controlled trials and 82 women and 234 men received the pharmacological intervention. In the placebo group there were 88 women and 219 men. In addition to the pharmacological intervention and placebo, some form of psychological intervention was offered in all included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics and findings of included studies.

Several medications with different mechanisms of action were applied in the studies included in this review. Cornelius et al. [57] examined the role of fluoxetine while McRae-Clark et al. [58] used vilazodone. Both medications are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The effect of buspirone, a serotonin 5-HT1A partial agonist, was explored by McRae-Clark et al. [59]. Lastly, Gray et al. [57] examined the effect of N-acetylcysteine, a supplement promoting glutamate release and modulating N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA).

All studies were undertaken in outpatient settings. In one study, the scheduled duration for the clinical trial was 8 weeks [58] while in the three other studies, it was 12 weeks [56,57,59]. The four selected studies were all conducted in the USA. The mean age of participants was between 16.64 [56] and 29.8 years [57]. Three studies included young adults [57,58,59] and one study targeted adolescents [56]. In one study, participants had comorbid major depression and cannabis use disorders [56]. The other three studies excluded people with psychiatric conditions.

5.2. Sex-Disaggregated Outcomes

In one of the included articles, sex was not a significant predictor of cannabis abstinence, and there was no sex-by-treatment interaction [57]. Females showed a greater improvement with time on depressive symptoms (F = 5.01, p = 0.028) and DSM cannabis abuse criteria count than males (F = 4.22, p = 0.044) [56]. In a study using buspirone McRae-Clark et al. (2015) [59] found that UCTs were negative in 8.7% of buspirone and 4.5% of placebo of male participants. In females, 2.4% of buspirone participant UCTs were negative and 12.9% of placebo; although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.007). Regarding the creatinine adjusted cannabinoid levels, there was a sex by treatment interaction indicating that for males, those randomized to buspirone treatment had significantly lower creatinine adjusted cannabinoid levels as compared to those randomized to placebo. For females, those randomized to placebo had lower creatinine adjusted cannabinoid levels compared to those randomized to buspirone [59]. Examining the effect of vilazodone, McRae-Clark (2016) found that males had significantly lower creatinine-adjusted cannabinoid levels and a trend for increased negative urine cannabinoid tests compared to females [58].

5.3. Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis of the Included Studies

The assessments of the role of sex- and gender-based analysis in the included studies is presented in Table 3. While Cornelius et al. and Gray et al.´s studies were classified in the sex/gender differences category, McRae-Clark et al. (2015) [59] and McRae-Clark et al. (2016) [58] were categorized as SGBA (see Table 3). Based on the categories that were analyzed, the results are as follows:

Table 3.

SGBA applied to cannabis pharmacological interventions.

1. Aim and research questions: The four studies included sex/gender in the study design or the reporting. However, none of the studies included sex or gender in their major research question.

2. Reporting sex/gender in the results: In Cornelius et al.´s study [56] on the effects of fluoxetine in adolescents and young adults with comorbid depression and cannabis use dependence, sex by time was analyzed for the outcomes of the study (number of days participants used cannabis in past month; DSM cannabis dependence count; DSM CUD total count - DSM dependence + abuse symptoms). The authors also examined whether abstinence rates differed across sex [56]. Although Gray et al. did not find statistically significant results, they examined whether sex was a predictor of cannabis abstinence, and whether there was a sex-by-treatment interaction [57]. McRae-Clark (2016) used sex as one of the randomization variables in addition to the presence or absence of anxiety or depressive disorders [58]. Sex and sex by treatment group interactions were added to examine the effect of gender on the primary and secondary efficacy outcomes in a randomized clinical trial that tested the efficacy of vilazodone, a selective serotonin receptor inhibitor and partial 5-HT1A agonist, for treatment of cannabis dependence [58]. McRae-Clark et al. also conducted a sex- and gender-based analysis since they used sex as a stratified randomization variable [59]. Sex was analyzed in relationship to the negative UCTs and cannabinoid levels in this study that examined the efficacy of buspirone for participants with cannabis use dependence [59].

3. Interpretation of Sex/Gender findings: Cornelius et al. did not report their findings related to sex and/or gender in the discussion section [56]. Gray et al. did not discuss any aspects of sex or gender, likely because their results were not statistically significant [57]. The differences reported in the results section are interpreted and explained in McRae-Clark et al. (2015) [59] and McRae-Clark et al. (2016) [58]. McRae-Clark et al.’s study, which featured sex or gender in their research question, provided a comprehensive discussion of their interpretation of the impact of sex and gender in their findings [59]. In this study, the authors acknowledged that this is the first study to demonstrate a sex difference in response to a pharmacological treatment for cannabis dependence. The authors highlighted the importance of including gender in the development and evaluation of new treatments for addictive disorders [59]. However, they did not specify what sex or gender-related factors could be considered for the development and evaluation of new treatments for addictive disorders. McRae-Clark et al.’s (2016) study suggests that women with CUD might have more problems in achieving cannabis cessation compared to men with CUD [58]. Their findings are related to sex and gender in the discussion. They also note that their analyses of sex differences might have been underpowered, and they mention that women are underrepresented in pharmacological trials calling for higher representativity of women in future studies.

4. Intentional and accurate use of terminology: None of the included studies define sex and gender. Cornelius et al. use only the term sex and they do not mention gender [56], while Gray et al. used sex and gender interchangeably [57]. For example, in the sociodemographic table the authors use “gender” and throughout the paper they mentioned “sex”. McRae-Clark et al. and McRae-Clark et al. used “gender” throughout the article though the study is in fact measuring sex although they also employ the terms females and males and women and men at the same time [58,59]. All four articles included in this systematic review lacked accuracy in the application of the concepts of sex and gender. Not even the articles that were categorized as applying a sex- and gender-based analysis in their studies used intentional and accurate terminology throughout the articles.

6. Discussion

In this systematic review on sex- and gender-related factors in cannabis pharmacological interventions, there was a paucity of studies that sex-disaggregated outcomes for women and men or analyzed the sex- or gender-related factors in the interventions. Although overall the findings showed that the pharmacological interventions analyzed in the studies (fluoxetine, vilazodone, buspirone, N-acetylcysteine) are not effective for treating CUD, three of the four included studies found different results for women and men. Of the three studies, one showed that females demonstrated a greater improvement with time on the depressive symptoms and DSM cannabis abuse criteria count than males [56]. The other two studies suggest that women have worse results than men in cannabis pharmacological interventions [58,59].

The lack of reported sex-disaggregated results does not mean that there are no differences or similarities between women and men. However, it is not possible to accurately interpret these results. Given the emergent evidence of sex- and gender-related factors in cannabis research [42,43], sex- and gender-related factors may intervene in the efficacy of cannabis pharmacological interventions. As in the case of smoking cessation treatment, demonstrating that women have more difficulty maintaining long-term abstinence than men [60], two of the four included studies showed that women have worse outcomes when examining the efficacy of buspirone [59] and vilazodone [58].

Even though the included studies did not find a greater efficacy of the pharmacological intervention, two of the four studies found that women had better results in the placebo group while men had better results in the pharmacological intervention group [58,59]. The different mechanisms generating the placebo effect between women and men are not well understood. However, preliminary findings suggest that sex- and gender-related factors might also be intervening in the placebo effect [61].

Although two of the included studies described the integration of aspects of sex into research questions, analysis, reporting of findings and discussion, there is an overall lack of comprehensive integration and analysis of sex and gender in these randomized controlled trials. These findings are consistent with those found by Welch et al. (2017) examining the use of sex and gender considerations in 100 Canadian-led or funded RCTs [6]. This study showed that 98% of studies included sex in the description of sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and only 6% conducted a subgroup analysis across sex and 4% reported sex-disaggregated data. Even in those RCTs that included females, most of the studies did not sex-disaggregate the outcomes [6].

Studying the effect of sex- and gender-related factors in cannabis pharmacological interventions is challenging and there is still an overall lack of research on sex, gender and cannabis. To determine sex- and gender-related factors in pharmacological interventions for cannabis use, researchers urgently need to fill this void. The preliminary findings show that women might not benefit from certain pharmacological interventions. Including and reporting sex- and gender-related factors might contribute to better determine the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for both women and men and tailor treatment for all individuals.

In the included studies, the terms “sex” and “gender” were used in an inconsistent way and there were no definitions provided for these terms. Three of the included studies used “sex” and “gender” interchangeably. Throughout the studies, authors used “male/female” and “women/men” and the use of “gender” was inaccurate. These findings are consistent with results from a study on Campbell and Cochrane systematic reviews [62]. Petkovic et al. (2018) found that reporting in systematic reviews is inadequate [62]. None of the studies in our systematic review included gender diverse populations or other gender considerations. Findings from a scoping review on how gender norms, roles and relations impact cannabis use patterns showed that there is a complex relationship between substance use and gender norms. While certain feminine and masculine norms might be protective, there are others that might be linked with greater risk of developing cannabis use dependence [50].

This systematic review has limitations. Since sex and gender are not often examined in pharmacological interventions for cannabis use, our results are limited. This is reflected in the small number of studies that met the inclusion criteria, and therefore, what we could draw from for interpretation. Our search strategy was designed taking into account that there is a growing body of literature that focuses on sex- and gender-related factors and we conducted searches using sex- and gender-related keywords [63]. However, since the use of sex and gender terms are not used in pharmacological interventions for cannabis use, we reviewed references from a recent systematic review [52] and screened those that were not captured by our search strategy. Sex and gender factors might have been tested in many other studies but not reported. We did not contact authors for further details on sex- and gender-based analysis, methods or results. Although we intended to apply the Feminist Quality Appraisal Tool [64] to analyze the ways in which gender is addressed in the included studies, the lack of deeper gender analysis did not support it. We did not perform a quality assessment of the studies since our aim was to examine the role of sex- and gender-related factors and the uptake of sex- and gender-based analysis. The included articles were assessed in two previous systematic reviews that examined the effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence [51,52].

7. Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to examine the treatment outcomes in cannabis pharmacological interventions for women and men. In addition, it analyzed the uptake of sex- and gender-based analysis in pharmacological interventions for cannabis use. Despite the increasing evidence showing that sex and gender factors intervene in patterns of cannabis use, health effects and biological mechanisms, we found only four articles that sex-disaggregated the outcomes for both sexes on CUD treatment. Taking into account the poor uptake of sex- and gender-based analysis, future research should consider more consistent and disciplined integration of sex and gender in cannabis pharmacological interventions in order to improve outcomes for all individuals experiencing CUD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.B. and L.G.; methodology, A.C.B., N.H. and J.S.; data curation, A.C.B. and N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.B.; writing—review and editing, A.C.B., L.G., N.H. and J.S.; funding acquisition, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Team Grant: Impact of Gender on Knowledge Translation Interventions (Evaluating the Effectiveness of Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis on Knowledge Translation Interventions).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Tannenbaum, C.; Greaves, L.; Graham, I.D. Why sex and gender matter in implementation research. Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Sharman, Z.; Vissandjée, B.; Stewart, E.D. Does a Change in Health Research Funding Policy Related to the Integration of Sex and Gender Have an Impact? PloS ONE 2014, 9, e99900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Gender and Health. Science is Better with Sex and Gender, Strategic Plan; Canadian Institutes of Health Research: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019.

- Johnson, J.L.; Greaves, L.; Repta, R. Better Science with Sex and Gender: A Primer for Health Research; Women’s Health Research Network: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N. Genders, sexes, and health: What are the connections—And why does it matter? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 32, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, V.; Doull, M.; Yoganathan, M.; Jull, J.; Boscoe, M.; Coen, S.E.; Marshall, Z.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Pederson, A.; Petkovic, J.; et al. Reporting of sex and gender in randomized controlled trials in Canada: A cross-sectional methods study. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2017, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazargan-Hejazi, S.; Doull, M.; Yoganathan, M.; Jull, J.; Boscoe, M.; Coen, S.E.; Marshall, Z.; Pardo, P.J.; Pederson, A.; Petkovic, J.; et al. Gender comparison in referrals and treatment completion to residential and outpatient alcohol treatment. Subst. Abuse 2016, 10, S39943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, S.F. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007, 86, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grella, C.E.; Mitchell, P.K.; Alison, A.M. Gender and comorbidity among individuals with opioid use disorders in the NESARC study. Addict. Behav. 2009, 34, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, S.F.; Rosa, C.; Putnins, S.I.; Green, C.A.; Brooks, A.J.; Calsyn, D.A.; Cohen, L.R.; Erickson, S.; Gordon, S.M. Gender research in the National Institute on Drug Abuse National Treatment Clinical Trials Network: A summary of findings. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2011, 37, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.; Curran, G.M.; Booth, B. Barriers and facilitators for alcohol treatment for women: Are there more or less for rural women? J. Subst. Abuse 2010, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bold, K.W.; Epstein, E.E.; McCrady, B.S. Baseline health status and quality of life after alcohol treatment for women with alcohol dependence. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Storbjörk, J. Gender differences in substance use, problems, social situation and treatment experiences among clients entering addiction treatment in Stockholm. Nordisk. Alkohol. Nark. 2011, 28, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, K.A.; Scott, J. Sex differences in long-term smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008, 10, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.H.; Andrea, H.W.; Zhang, J.; Erin, E. Sex Differences in Smoking Cessation Pharmacotherapy Comparative Efficacy: A Network Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 19, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.H.; Zhang, J.; Weinberger, A.H.; Mazure, C.M.; McKee, S.A. Gender differences in the real-world effectiveness of smoking cessation medications: Findings from the 2010–2011 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 178, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatard, A.; Dobrinas, M.; Gholamrezaee, M.; Lubomirov, R.; Cornuz, J.; Csajka, C.; Eap, C.B. Association of nicotine metabolism and sex with relapse following varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 25, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, S.A.; Smith, P.H.; Kaufman, M.; Mazure, C.M.; Weinberger, A.H. Sex Differences in Varenicline Efficacy for Smoking Cessation: A Meta-Analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.H.; Karin, A.K.; Sherry, A.M. Gender differences in medication use and cigarette smoking cessation: Results from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, S.F.; Pettinati, H.M.; O’Malley, S.; Randall, P.K.; Randall, C.L. Gender differences in alcohol treatment: An analysis of outcome from the COMBINE study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 34, 1803–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B.J.; Lehert, P. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence: A sex-specific meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 36, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitschfeld, M.J.; Schneekloth, T.D.; Ebbert, J.O.; Hall-Flavin, D.K.; Karpyak, V.M.; Abulseoud, O.A.; Patten, C.A.; Geske, J.R.; Frye, M.A. Female smokers have the highest alcohol craving in a residential alcoholism treatment cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 150, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baros, A.M.; Latham, P.K.; Anton, R.F. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of alcohol dependence: Do sex differences exist? Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2008, 32, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbeck, D.M.; Schneekloth, T.D.; Ebbert, J.O.; Hall-Flavin, D.K.; Karpyak, V.M.; Abulseoud, O.A.; Patten, C.A.; Geske, J.R.; Frye, M.A. Gender differences in treatment and clinical characteristics among patients receiving extended release naltrexone. J. Addict. Dis. 2016, 35, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinati, H.M.; Kampman, K.M.; Lynch, K.G.; Suh, J.J.; Dackis, C.A.; Oslin, D.W.; O’Brien, C.P. Gender differences with high-dose naltrexone in patients with co-occurring cocaine and alcohol dependence. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2008, 34, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, R.K.; Devito, E.E.; Dodd, D.; Carroll, K.M.; Potter, J.S.; Greenfield, S.F.; Connery, H.S.; Weiss, R.D. Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2013, 45, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.M.; Fairman, B.; Gilreath, T.; Xuan, Z.; Rothman, E.F.; Parnham, T.; Furr-Holden, C.D. Past 15-year trends in adolescent marijuana use: Differences by race/ethnicity and sex. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 155, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legleye, S.; Daniela, P.; Fred, P.; Céline, G.; Myriam, K.; Ludwig, K. Is there a cannabis epidemic model? Evidence from France, Germany and USA. Int. J. Drug Policy 2014, 25, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.; Louisa, D. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet 2009, 374, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Quintero, C.; Pérez, C.J.; Hasin, D.S.; Okuda, M.; Wang, S.; Grant, B.F.; Blanco, C. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 115, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, R.; Hofler, M.; Lueken, U. Cannabis use patterns and their association with DSM-IV cannabis dependence and gender. Eur. Addict. Res. 2011, 17, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.T.; Li, N.; McClure, E.A.; Sonne, S.C.; Gray, K.M. Gender Differences in Internalizing Symptoms and Suicide Risk Among Men and Women Seeking Treatment for Cannabis Use Disorder from Late Adolescence to Middle Adulthood. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2016, 66, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, C.; Rafful, C.; Wall, M.M.; Ridenour, T.A.; Wang, S.; Kendler, K.S. Towards a comprehensive developmental model of cannabis use disorders. Addiction 2014, 109, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.S.; Secades-Villa, R.; Okuda, M.; Wang, S.; Pérez-Fuentes, G.; Kerridge, B.T.; Blanco, C. Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 130, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepis, T.S.; Desai, R.A.; Cavallo, D.A.; Smith, A.E.; McFetridge, A.; Liss, T.B.; Potenza, M.N.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. Gender differences in adolescent marijuana use and associated psychosocial characteristics. J. Addict. Med. 2011, 5, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerridge, B.T.; Desai, R.A.; Cavallo, D.A.; Smith, A.E.; McFetridge, A.; Liss, T.B.; Potenza, M.N.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. DSM-5 cannabis use disorder in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III: Gender-specific profiles. Addict. Behav. 2018, 76, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Z.D.; Craft, R.M. Sex-Dependent Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: A Translational Perspective. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 43, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.M.; Matthew, R.; Robert, I.B.; Godfrey, P. Sex, drugs, and cognition: Effects of marijuana. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2010, 42, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Z.D.; Haney, M. Investigation of sex-dependent effects of cannabis in daily cannabis smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 136, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, J.S.; Kelly, T.H.; Westgate, P.M.; Lile, J.A. Sex differences in the subjective effects of oral DELTA9-THC in cannabis users. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2017, 152, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattore, L.; Fratta, W. How important are sex differences in cannabinoid action? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copersino, M.L.; Boyd, S.J.; Tashkin, D.P.; Huestis, M.A.; Heishman, S.J.; Dermand, J.C.; Simmons, M.S.; Gorelick, D.A. Sociodemographic characteristics of cannabis smokers and the experience of cannabis withdrawal. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2010, 36, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, E.; Weerts, E.; Vandrey, R. Sex Differences in Cannabis Withdrawal Symptoms Among Treatment-Seeking Cannabis Users. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 156, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, B.J.; McRae-Clark, A.L.; Baker, N.L.; Sonne, S.C.; Killeen, T.K.; Cloud, K.; Gray, K.M. Gender differences among treatment-seeking adults with cannabis use disorder: Clinical profiles of women and men enrolled in the achieving cannabis cessation-evaluating N-acetylcysteine treatment (ACCENT) study. Am. J. Addict. 2017, 26, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttler, C.; Mischley, L.K.; Sexton, M. Sex Differences in Cannabis Use and Effects: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Cannabis Users. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.P.; Smith, D.C.; Morphew, J.W.; Lei, X.; Zhang, S. Cannabis Withdrawal, Posttreatment Abstinence, and Days to First Cannabis Use Among Emerging Adults in Substance Use Treatment: A Prospective Study. J. Drug Issues 2016, 46, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lev-Ran, S.; Imtiaz, S.; Taylor, B.J.; Shield, K.D.; Rehm, J.; Foll, B. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among cannabis users: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 123, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusich, J.A.; Lefever, T.W.; Antonazzo, K.R.; Craft, R.M.; Wiley, J.L. Evaluation of sex differences in cannabinoid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 137, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harte-Hargrove, L.C.; Dow-Edwards, D.L. Withdrawal from THC during adolescence: Sex differences in locomotor activity and anxiety. Behav. Brain Res. 2012, 231, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsing, N.; Greaves, L. Gender norms, roles and relations and cannabis use patterns: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. Forthcoming. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, K.; Gowing, L.; Ali, R.; Le Foll, B. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Gowing, L.; Sabioni, P.; Le Foll, B. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Iberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarström, A. A tool for developing gender research in medicine: Examples from the medical literature on work life. Gender Med. 2007, 4, S123–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, L.; Milne, E.; Waite, N.; Cooke, M.; Cook, K.; Chang, F.; Sproule, B.A. Sex and gender-based analysis in pharmacy practice research: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelius, J.R.; Bukstein, O.G.; Douaihy, A.B.; Clark, D.B.; Chung, T.A.; Daley, D.C.; Wood, D.S.; Brown, S.J. Double-blind fluoxetine trial in comorbid MDD-CUD youth and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 112, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.M.; Sonne, S.C.; McClure, E.A.; Ghitza, U.E.; Matthews, A.G.; McRae-Clark, A.L.; Carroll, K.M.; Potter, J.S.; Wiest, K.; Mooney, L.J.; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine for cannabis use disorder in adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 177, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae-Clark, A.L.; Sonne, S.C.; McClure, E.A.; Ghitza, U.E.; Matthews, A.G.; McRae-Clark, A.L.; Carroll, K.M.; Potter, J.S.; Wiest, K.; Mooney, L.J.; et al. Vilazodone for cannabis dependence: A randomized, controlled pilot trial. Am. J. Addict. 2016, 25, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae-Clark, A.L.; Baker, N.L.; Gray, K.M.; Killeen, T.K.; Wagner, A.M.; Brady, K.T.; DeVane, C.L.; Norton, J. Buspirone treatment of cannabis dependence: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 156, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.H.; Bessette, A.J.; Weinberger, A.H.; Sheffer, C.E.; McKee, S.A. Sex/gender differences in smoking cessation: A review. Prev. Med. 2016, 92, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franconi, F.; Campesi, I.; Occhioni, S.; Antonini, P.; Murphy, M.F. Sex and gender in adverse drug events, addiction, and placebo. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 214, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Petkovic, J.; Trawin, J.; Dewidar, O.; Yoganathan, M.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V. Sex/gender reporting and analysis in Campbell and Cochrane systematic reviews: A cross-sectional methods study. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.M.; Imonsen, C.K.; Wilson, J.D.; Jenkins, M.R. Development of a PubMed Based Search Tool for Identifying Sex and Gender Specific Health Literature. J. Womens Health 2016, 25, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, T.; Williams, L.A.; Gott, M. A Feminist Quality Appraisal Tool: Exposing gender bias and gender inequities in health research. Crit. Public Health 2017, 27, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).