Abstract

Physical activity and diet are major modifiable risk factors for chronic disease and have been shown to be associated with neighborhood built environment. Systematic review evidence from longitudinal studies on the impact of changing the built environment on physical activity and diet is currently lacking. A systematic review of natural experiments of neighborhood built environment was conducted. The aims of this systematic review were to summarize study characteristics, study quality, and impact of changes in neighborhood built environment on physical activity and diet outcomes among residents. Natural experiments of neighborhood built environment change, exploring longitudinal impacts on physical activity and/or diet in residents, were included. From five electronic databases, 2084 references were identified. A narrative synthesis was conducted, considering results in relation to study quality. Nineteen papers, reporting on 15 different exposures met inclusion criteria. Four studies included a comparison group and 11 were pre-post/longitudinal studies without a comparison group. Studies reported on the impact of redeveloping or introducing cycle and/or walking trails (n = 5), rail stops/lines (n = 4), supermarkets and farmers’ markets (n = 4) and park and green space (n = 2). Eight/15 studies reported at least one beneficial change in physical activity, diet or another associated health outcome. Due to limitations in study design and reporting, as well as the wide array of outcome measures reported, drawing conclusions to inform policy was challenging. Future research should consider a consistent approach to measure the same outcomes (e.g., using measurement methods that collect comparable physical activity and diet outcome data), to allow for pooled analyses. Additionally, including comparison groups wherever possible and ensuring high quality reporting is essential.

Keywords:

natural experiment; built environment; neighborhood; physical activity; diet; longitudinal 1. Introduction

The potential for city planning to promote more equitable health outcomes is of major international research and policy interest [1]. Physical activity and diet (determinants of energy balance and modifiable risk factors for chronic disease) are associated with neighborhood built environment. For example, relationships have been identified between: the presence of green space and higher levels of walking and total physical activity [2]; greater availability of supermarkets and fresh produce markets with more fruit and vegetable intake (beneficial impact), but also greater sugar-sweetened beverage intake (detrimental impact) [3]; greater use of public transport and higher physical activity [4]; and greater presence of speed limits less than 30 km/h, bicycle lanes, trees, litter, and fewer traffic calming technologies, with higher levels of cycling [5]. Whilst these studies and others have reported cross-sectional associations between built environment and physical activity or diet [6,7,8,9], evidence from longitudinal studies synthesized in systematic reviews are required to guide evidence-based policies [10].

Endogeneity is the mutual impact of individual characteristics and associated neighborhood characteristics on each other. For example, research suggests that neighborhood green space promotes physical activity [2] and correlations have been shown between the amount of green space and property prices [11]. Additionally, participation in physical activity is more frequent among more affluent population groups [12]. People with lower incomes tend to live in neighborhoods with less green space [2], as green space costs are capitalized into property prices. Therefore, raising house prices to make increased green space available may make these neighborhoods only accessible to healthier and wealthier people who are already more likely to be physically active.

Natural experiments are promoted as a potential answer to overcoming some challenges of endogeneity [13]. These are studies where the ‘intervention’ is occurring beyond the control and instigation of researchers. The intervention is not strictly randomly allocated, but circumstances in which it occurs are suggested to potentially help minimize the issue of endogeneity. Examples have included the ban on smoking in public places across a country on number of hospitalizations [14], reductions in neighborhood crime rates on the experience of psychological distress [15], and the provision of new local cycling infrastructure on active travel [16]. In these scenarios, circumstances change rapidly around people who tend to remain living in the same neighborhoods (although some change may happen post-intervention). Whilst acknowledging there will be some selectivity in terms of which people lived in particular areas initially, changes occurring in their neighborhood are unlikely to have been of their choice. To minimize ‘neighborhood effects’, tracking the impacts of interventions within residentially stable populations is suggested [17].

Previous systematic reviews have tended to place less emphasis on endogeneity, including studies of varying design [6,18,19,20]. In the current study, the aim is to review studies focusing specifically on natural experiments of the built environment in neighborhoods (referred to hereafter as the ‘exposure’), occurring around residentially stable populations, which have measured changes in physical activity or diet. Study characteristics, study quality, and impact of exposures on physical activity and diet are summarized. The review aims to answer the following questions in relation to natural experiments of neighborhood built environment:

- What were the characteristics of studies, including exposure type (e.g., food retail, green space), study design, follow-up duration, recruitment strategies, retention level, study aims and outcome measures?

- What was the quality level of included studies based on assessment of risk of bias?

- What was the impact of exposures on physical activity and diet of residents?

2. Materials and Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed throughout this review [21].

2.1. Search Strategy

The following databases were searched: Embase (OVID); MEDLINE (OVID); PubMed; Web of Science; and CINAHL. All authors reviewed the search strategy and the lead author carried out the search. Keywords relating to study design, the built environment, health and health-related behaviors were used (apart from in the CINAHL search, which excluded a study design keyword—the number of returned titles was low with inclusion of study design terms). Details of the full search strategy for the Web of Knowledge database are provided in Table S1. Similar keywords relevant to search other databases and MeSH headings were used where available. Searches were conducted in May 2014. An updated search was run in May 2017. Secondary searches of reference lists of included articles and relevant reviews were also conducted to identify eligible studies.

2.2. Study Eligibility

Eligibility criteria for this review aligned with the “Population”, “Intervention”, “Comparisons”, “Outcomes”, “Study designs” (PICOS) strategy [22] as follows:

- Population: Studies included any age, gender, and characteristics of the population/target site. Participants needed to be reported in papers to reside and be residentially stable in the neighborhood where the exposure/s occurred (i.e., participants resided in the same neighborhood for the duration of the study—samples included the same participants at baseline and follow-up).

- Intervention/exposure: A change in the local environment was defined as a development in existing (regeneration) or introduction of new public built infrastructure to the area in close locality to where individuals reside (e.g., their neighborhood that could potentially impact on physical activity or diet, such as the introduction/regeneration of supermarkets or local food markets, rail lines, green space and cycle routes).

- Comparisons: Studies were included if the impact of an exposure was assessed based on changes in outcomes over time (i.e., pre-post exposure) in the same sample of participants, or changes in these outcomes over time in a comparator group that did not receive the exposure.

- Outcomes: Studies were included if they measured physical activity or diet (no restriction on the measurement method). Studies including a direct proxy of behavior were included (e.g., usage of a facility for cycling or walking).

- Study designs: Studies were included if they were reported to be, or appeared from reading, natural experiments (built environment change not instigated by researchers).

Peer-reviewed articles published in English were included. No limitation on year of publication or length of follow-up was set.

2.3. Exclusions

Studies were excluded if: (i) they were reported as comprising multi-component exposures (e.g., exposures which explicitly reported social interventions, including promotional marketing to encourage use of built environment features in addition to infrastructure change), as it would not be possible to attribute changes in physical activity and diet specifically to the built environment change; (ii) changes were internal housing improvement (e.g., heating/electrical improvements in housing); (iii) no clearly defined or measured exposure was studied (e.g., studies which compared groups exposed to different, or pre-existing built environments but with no specific change to the built environments within groups); (iv) changes were stated explicitly to occur outside of residential neighborhoods (e.g., workplace or public transport developments); (v) they explored the impact of a detrimental change in built environment (e.g., natural disaster or demolition); (vi) no physical activity or diet outcomes were reported (e.g., focus upon self-sufficiency or criminal behavior); and (vii) participants were not residentially stable (e.g., participants were reported as residents recruited from the same area/neighborhood at baseline and follow-up/s but the sample was not reported to consist of the exact same cohort at baseline and follow-ups).

2.4. Data Extraction and Appraisal

Review instructions were developed by the lead author (Freya MacMillan) and followed by all authors to ensure consistency in article screening, data extraction and risk of bias ratings. Standard data extraction datasheets were utilized. Eight researchers (Amelia Cook, Andrew Bennie, Bonnie Pang, Fran Moran (see Acknowledgements), Genevieve Dwyer, Dafna Merom, Taren Sanders, Brendon Hyndman (see Acknowledgements)) reviewed a selection of titles and abstracts. Two researchers (Emma S. George, Freya MacMillan) who were not involved in the initial screening independently screened ten percent of identified references deemed ineligible based on titles and/or abstract. A further two researchers not involved in initial screening (Thomas Astell-Burt, Xiaoqi Feng), screened all references deemed eligible based on title and abstract review. Three researchers (Freya MacMillan, Emma S. George, Justin M. Guagliano) reviewed full-text articles and undertook initial data extraction. Seven independent researchers (Thomas Astell-Burt, Andrew Bennie, Amelia Cook, Bonnie Pang, Gregory S. Kolt, Taren Sanders, Xiaoqi Feng) reviewed a sub-set of full-texts and extracted mean data.

A tool for assessing methodological risk of bias in natural experiments exploring the impact of built environment change on physical activity exists [23]. As the rigidity of this tool has been questioned for this type of research [24], a more pragmatic set of items were used in this review. Included studies were assessed using a 9-item tool including two items from the Cochrane Collaboration for assessing risk of bias tool on attrition (incomplete outcome data) and reporting bias (selective outcome reporting) [25]. Seven items considering bias due to study design, sampling approach, confounding and adjustment, outcome measurement objectivity, power and attrition rate effect on power, levels of exposure, and exposure use/adoption were developed based on important considerations for natural experiments discussed in the UK. Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines [26,27] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk of bias item descriptions.

2.5. Synthesis of Results

Table 2 summarizes included study details. Analytic items used to organize the extracted data were: authors, year of publication and study location; study aims; target population descriptive characteristics, recruitment methods and study duration; study design, including development description; outcome measures (studies had to have a measure of physical activity or diet to be included but all other lifestyle and health outcome data were extracted—the results section lists all measures identified) and methods; and results for full sample and any sub-group analyses.

Table 2.

Summary of included study characteristics and longitudinal findings.

Four researchers (Emma S. George, Freya MacMillan, Genevieve Dwyer and Fran Moran (see Acknowledgements)) rated studies (present or not present/unclear) based on what was reported in each article for the potential sources of bias (detailed above). Studies were scored out of 9 (one mark for each item). When five independent reviewers (Gregory S. Kolt, Dafna Merom, Xiaoqi Feng, Thomas Astell-Burt and Andrew Page (see Acknowledgements)) conducted risk of bias ratings, the agreement rate was 95.8%. Reviewers discussed discrepancies throughout the review process until consensus was achieved. The analytical approach taken was a narrative description (meta-analysis was considered but rejected due to large heterogeneity in reported outcomes (see Results section)).

3. Results

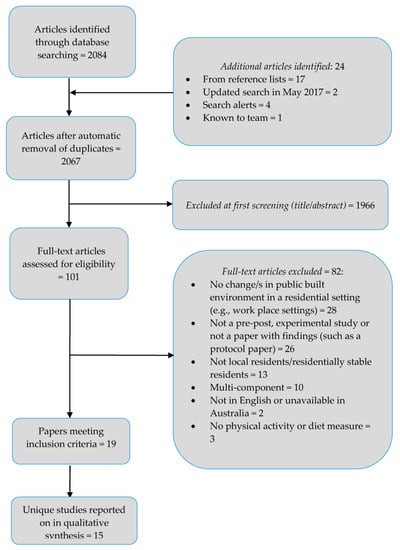

A total of 2084 references were identified from initial database searching, plus 24 references from other sources (e.g., identified from reference lists and search alerts, Figure 1). Following removal of duplicates and exclusion of 1966 references based on an initial title and abstract screening phase, 101 references were included for further review. Reasons for excluding studies at the final screening stage are detailed in Figure 1 (further detail is provided in Table S2), with the most common reasons being that the studies did not meet inclusion criteria relating to built environmental change (n = 28) or due to study design (e.g., no results published, such as in a protocol paper, n = 26). The remainder of this results section focuses on the 19 eligible papers identified for this review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

3.1. Study Characteristics

Nineteen papers, reporting on 15 different exposures employing longitudinal natural experimental designs were identified and included in this review. Throughout the results/discussion section, the 15 unique experiments are considered (the number of papers that are associated with the specific experiment are referenced). Five studies focused on cycle and/or walking trails [29,35,36,37,38,40], four on rail stops/lines [33,34,39,41,42], two on park and green space [28,43], and four on food retail (including supermarkets [30,31,32,45,46]) and farmers’ markets [44]). Two papers reported on the same supermarket developments (one in Glasgow, Scotland [30,31], and one in Leeds, England [45,46]), two reported on the same cycle/walk trail exposure [37,38] and two reported on the same rail stop introduction [41,42]; each paper addressed different health outcomes or extending analyses. The publication date ranged from 2002 [45] to 2016 (n = 2 studies) [34,40]. Ten studies were conducted in the U.S. [29,32,33,34,35,36,39,41,42,43,44], three in the UK [30,31,37,38,45,46], one was conducted in South America [40] and one was conducted in New Zealand [28].

3.2. Study Design and Follow-Up Duration

Eleven/15 studies (73%) were of a single group pre-post/longitudinal design [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], while the remaining four studies included a comparison group [28,29,30,31,32]. Two studies had more than one follow-up data collection time point at one and five [35] months and at 12 and 24 months [37,38].

Follow-up duration ranged from two months [36,44] to 36 months [40] after exposure (duration of ≤6 months, n = 6 studies [28,32,34,35,36,44]; 6.1–12 months, n = 6 studies [30,31,33,39,41,42,43,45,46] and >12 months, n = 2 studies [37,38,40]). One study collected follow-up data between 2 and 12 months following exposure [29].

3.3. Recruitment Procedures and Retention

Of studies that reported on data collection and recruitment methods, a variety of approaches were utilized including: door-to-door visits in two studies [41,42,45,46], door-to-door visits at baseline followed by telephone or mail at follow-up in one study [44], mail notification of the study followed by a door-to-door visit in one study [33], solely via mail in four studies [30,31,34,37,38,43], flyer drop-off to doors in one study [29], mail notification followed by telephone data collection in one study [36], solely via telephone in three studies [32,39,40] and via schools using information letters for students and parents in one study [28]. Representativeness of the sample, based on descriptive census or other local and national data, was reported in four studies [36,37,38,44,45,46]. In studies reporting on the number of individuals invited to participate, the study invitation acceptance rate ranged from ~1% to 15% in three studies [30,31,34,37,38], 31–47% in six studies [32,33,35,36,43,45,46] and above 90% in two studies [40,44], with studies using only mail or flyer drop-off recruitment showing the lowest acceptance rates. Incentives, to support recruitment and retention, were reported in four studies [28,30,31,34,45,46].

Total sample size at baseline (regardless of the number of groups) ranged from 92 [44] in a study exploring the introduction of farm stands, to 3516 [37] in a study on the impact of a cycle/walk route. At final follow-up, total sample size ranged from 47 [33] in a rail stop study to 1510 [37] in a cycle/walk route study. Including all studies, the median sample size at baseline was 603, with eight studies reporting a sample size ≤the median [28,29,30,31,33,34,35,43,44].

Participant retention from baseline to final follow-up ranged from 45% [32,43] to 84% [28]. Two studies provided a sample size calculation [28,40] and a further two studies reported a target sample size [44,45,46]—the remaining studies did not report either. Only one study targeted children [28]. Three studies reported specifically targeting recruitment from socially deprived/low-income areas [30,31,44,45,46].

3.4. Aims and Outcome Measures

The reported primary aim of studies varied considerably, as did the methods of assessment. Most studies (11/15) included physical activity as a primary outcome [28,29,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Five studies included objective measures of physical activity—two used accelerometers only [28,33], and three utilized accelerometers combined with GPS [29,34,41,42]. One study used a physical activity diary [35] and five included self-report surveys [36,37,38,39,40,43]. The remaining four studies focused primarily on diet [30,31,32,44,45,46]. Of those studies assessing dietary intake, one study measured food consumption with diaries [45,46], and three reported fruit and vegetable consumption using questionnaires of usual consumption: per day [30,31] over the past week [44], or consumption of specific fruits and vegetables over the previous month [32]. Additional outcome measures reported in studies were BMI, obesity and health (including psychological or mental health outcomes, collectively termed hereafter as well-being). BMI was measured by a health professional or researcher in two studies [28,41,42] and relied on self-reported weight and height in three studies [32,36,39]. Of these studies, one also included self-reported obesity [39]. Self-reported health and well-being was measured in two studies using the General Health questionnaire [30,31,36].

3.5. Study Quality

Reporting varied considerably across studies, with 13/15 studies having a high-risk score in ≥4/9 of the risk of bias items (Table 3). As previously mentioned, only 4/15 studies included a comparison that did not receive the exposure under study [28,29,30,31,32]. Level of exposure was explored in 5/15 studies based on distance to the exposure [34,37,38,40,43,45,46], whilst 6/15 studies examined outcomes based on use/adoption of the exposure [30,31,32,36,39,41,42,45,46]. Sample representativeness, by comparison to census or other local population data, was included in 8/15 studies [30,31,33,35,36,37,38,40,44,45,46].

Table 3.

Risk of bias ratings for included studies.

Although studies reported on all outcomes stated in the aims/methods, descriptive (e.g., mean/median) or statistics (e.g., p-values) were missing at pre/post time-points in 7/15 studies [30,31,32,33,37,39,43,45,46]. Incomplete data was addressed by use of data replacement and/or sensitivity analyses in 6/15 studies [29,32,37,38,39,40,41].

Differences in participant characteristics (between baseline and follow-up or between exposure and comparison groups at baseline) were reported and/or adjusted for in 11/15 studies [28,29,30,31,32,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,45,46]. The majority of studies relied on participant self-report data, with only 5/15 studies including an objective measure of physical activity [28,29,33,34,41,42] and researchers/health professionals measuring BMI in 2/15 studies [28,41]. Power calculations or target sample sizes were mentioned for 6/15 studies [28,32,38,40,41,45,46], but details of calculations were only stated in two papers [28,40].

3.6. Impact on Outcomes

3.6.1. Findings from Controlled Studies

Of the four studies [28,29,30,31,32] that included a comparison group (Table 2), one study reported improvements in self-reported fruit and vegetable intake 12 months after a new supermarket was introduced, but improvements were found both in the environmental change and comparison groups [30,31] (high risk in 5/9 risk of bias items). In this same study, a slight beneficial impact on well-being was found in the experimental group [30,31]: at 12-month the prevalence of poor psychological health had significantly decreased by 31% compared to the comparison group (only a 3% decrease). No changes over time or between groups were reported on health/behavior outcomes in the full samples of two controlled studies, one of which also introduced a supermarket [32] but had lower total risk of bias score (high risk in 4/9 items) and another introducing green space [28] (high risk in 4/9 items). In another study [29], residing in areas where bicycle routes were introduced was negatively correlated with bike trips and minutes cycling (high risk in 4/9 items).

Significant changes in sub-groups of controlled studies are reported in Table 2. Two studies, [30,31,32] conducted sub-analyses based on use/adoption of supermarket exposures. One of these studies reported reduced odds of poor psychological and physical health (see table for odds ratios) in those adopting the new supermarket over those that did not [30,31]. The other study did not report any changes in sub-groups [32].

3.6.2. Pre-Post Study Findings

Findings from pre-post evaluation studies (Table 2) indicated significant improvements in at least one outcome for the total sample in 4/11 uncontrolled studies, for which high risk of bias ratings were given in 3/9 [40] and ≥7/9 items [35,43,44]. Of these studies, the one study rating lowest risk of bias overall found that a walking/cycling route increased leisure time walking by 14 min per week after 36 months in Brazil [40].

No changes were reported in total samples of 4/11 uncontrolled studies, which measured physical activity changes after introductions of rail stops [33,34], a cycle path [37,38] or diet after a supermarket introduction [45,46]. One study reported detrimental impacts on vigorous physical activity eight weeks after the introduction of a multi-use trail [36]. Two studies did not measure changes in their overall sample [39,41,42].

Nine out of 11 uncontrolled pre-post studies analyzed data based on exposure level, where level was defined based on the use and/or adoption of the exposure (n = 4) [36,39,41,42,45,46] and/or home distance to the exposure (n = 5) [34,37,38,40,43,45,46]. Five of these nine studies reported significant beneficial changes in sub-groups based on expected hypotheses, one of which had a high risk of bias in 8/9 items [43] and the remainder of studies in ≤4/9 items [37,38,40,41,42,45,46]. For example, a new walk/cycle route increased total physical activity on average by 12.5 min/week per km closer to the exposure [38]. Two studies reported unfavorable changes [34,36], with a 77% reduction in vigorous physical activity minutes/week following introduction of a multi-use trail in those that had ever used the trail [36] (high risk of bias in 5/9 items). In comparison to those not using the trail, those who ever used the trail were less likely from baseline to follow-up to have increased walking by 30 min/week and 45 min/week [36]. The remaining study reported no significant changes [39].

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Overall Findings of This Review

This paper systematically reviewed natural experiments of the built environment occurring around residentially stable populations to report on study characteristics, study quality, and impact of changing built environment on physical activity and diet. Limited evidence was found to support built environment as an important factor influencing these outcomes, with large variation in results (8/15 studies reported at least one beneficial impact on these behaviors/health). However, study design (lack of a comparison group), underpowered sample sizes, the use of a wide array of outcome measures and limited reporting in some included studies, have made it challenging to draw overall conclusions in this review.

One of the higher quality studies (5/9 risk of bias items rated high risk) with a comparison group reported a small beneficial impact on well-being following the opening of a supermarket [30,31]. In 6/10 studies including sub-group analyses based on exposure level and use/adoption, these studies found improvements related to well-being, physical activity, BMI, and fruit and vegetable intake in those using and adopting the exposure, although sample sizes were small. These findings suggest that there is potential to improve health and behaviors by improving the built environment. However, to accurately inform policy, there is a need for future studies in this area to closely follow guidelines on conducting and fully reporting on natural experiments [26,27]. A discussion of how our findings support and add to this previously published guidance follows, with each area of the review covered in detail as per the aims stated in the Introduction.

4.2. Study Characteristics

4.2.1. Design

Natural experiments, by definition, are not designed by researchers and rarely, if ever, are designed with a specific aim of improving physical activity and diet—the impact of the natural experiment on such behaviors is most often a by-product of the exposure. Challenges for researchers in such experiments are therefore: defining causal pathways (e.g., the impact of the exposure on a range of outcomes); selecting appropriate outcomes to assess potential impacts on health; and identifying robust methods to measure changes in outcomes. The U.K. Medical Research Council (MRC) recommendations on conducting natural experiments [26,27] provide comprehensive best-practice guidance on identifying when natural experiments are appropriate, the methodological and analytical considerations in regards to reducing bias, and effective reporting. Two/six studies in the current review, published after the introduction of the MRC guidelines, cited their work, implying that this resource is not reaching or being implemented in practice. Implementation issues could be due to the inherent nature and challenges associated with this type of research, often outside the researcher’s control (e.g., timeline and budget); however other issues could and should always be addressed (e.g., consideration of confounders in analyses). Few included studies referred to their study as a natural experiment, and as such, lack of recognition for the relevance of the guidelines may also have influenced and limited their use in previous studies.

4.2.2. Outcomes, Recruitment and Retention

The range of health outcomes explored across studies was limited. As a result, important changes in outcomes may have been missed due to the lack of measurement or the use of inappropriate tools. Small, yet beneficial, changes in behaviors that shift people from not meeting to achieving or exceeding public health recommendations can have important health impacts [47]. Although physical activity and diet were measured in all studies, no studies reported on these behaviors in relation to meeting public health recommendations (e.g., % population achieving guidelines). Proxy measures of health and behaviors are useful (e.g., awareness and use of a fresh food store as an indicator for diet) to identify if and to what extent the infrastructure is known and used. However, used alone as a single measure, these may not provide enough evidence to draw conclusions on true impact (e.g., a park environmental change could increase both physical activity (beneficial impact), or sedentary behavior (detrimental impact)). None of the included studies incorporated a health economic analysis—a recommendation for natural experimental research [26,27]. This is likely due to the fact that natural experiments are not undertaken for the primary purpose of improving health and so data to inform cost-effectiveness may not have been considered from commencement of built environment changes.

Recruitment and retention is challenging in natural experiments. To reach target sample sizes, recruitment needs to be well planned and, although based on the findings of this review, incorporating face-to-face contact appears important, this is likely not feasible in large population studies. The use of incentives may result in the recruitment of biased samples; however, offering incentives may assist in overcoming the difficulties associated with recruiting disadvantaged populations (e.g., individuals from low socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds) [48] and should thus be considered. Considering use of incentives in future is particularly important as a recent review suggests that the most socioeconomically advantaged groups may benefit the most from physical activity and active transport built environment improvements [20], which may be because they are more likely to participate in this type of research than the most socioeconomically disadvantaged. In addition to recruitment, retention is an issue, particularly in areas where residential in- and out-migration is high. Systematic reviews of the use of incentives for retention in cohort [49] and RCT [50] studies support their use. Incentives did not appear to reduce attrition in the current review, however only four studies reported using them. Routinely collected data (as is recommended for evaluation of natural experiments [26,27]) was not used in any of the included studies and should be explored as a way of collecting data whilst avoiding recruitment/retention issues in future studies.

4.2.3. Geographic Location of Studies and Study Duration

Similar to previous reviews on the association of built environment and health [7,51], short follow-up duration, limited number of follow-up data points, and the clustering of studies in primarily high-income countries (mostly the U.S. and UK) was evident, with a small number of studies specifically recruiting from low SES areas. Timing and duration of data collection is important. Due to timeline changes, baseline data collection in one study included in this review [32] occurred three years before the exposure. The impact of such delays in timeline, although out of the control of the researcher, need to be considered and flexibility in data collection is needed to adjust for changes in the timing of the development of planned infrastructure. Another study in this review [29] had a variation of 2–12 months in follow up timing, resulting in some participants having more time than others to adopt change. Changes in intermediary health or behavior outcomes may be evident first before long-term outcomes. Depending on the outcome, impacts may be expected to occur close to or long after the exposure and can be short, or longer-lived. Logic modeling [52] is recommended to help identify what and when particular outcomes should be incorporated into evaluation, to assist with amendments required to data collection plans, and to consider sources of bias and ways of minimizing impact on findings [26,27]. Adequate level of exposure for meaningful differences in outcomes to occur should be considered as well as analyzing changes in built environment and resultant effects across several areas (SES and geographically diverse). The impact of built environment change may differ in middle and low-income countries in economic transition and increased urbanization, and this needs to be taken considered. Previous research shows that built environment modification did not achieve intended outcomes on the total target group exposed, but when stratified by SES [53], or migrant status [54], developments were found to minimize gaps in health inequality. The social distribution of impacts of environmental change should be considered in future research.

4.3. Study Quality

Comparison groups are important to provide less biased, or more precise estimates, of the impact of changes in built environment on changes in outcomes. Only four studies included a non-exposure comparison [28,29,30,31,32] and ten studies compared sub-groups with different levels of exposure based on distance [37,38,40,43,45,46] or use/adoption of the exposure [30,31,32,36,39,41,42,45,46]. Sub-analyses based on use/adoption provide a more accurate reflection of true impact of exposure—in studies only reporting on total sample results, the effects of exposure on behavior and health are blurred (from mixing data of those that use the exposure with those that do not use the exposure). Researchers should consider innovative ways of reliably capturing use/adoption, such as utilizing smart phones for real-time spatial tracking [55] or automated attendance recording [56]. To clearly identify the impact that built environment can have on physical activity and diet outcomes, pooled data from studies that have split their analyses based on use/adoption of the exposure with large enough samples to detect effects are required. Although distance from exposure might be an indicator of awareness and use, this is a proxy measure and direct measures may be more accurate and meaningful. A framework for considering exposure in natural experiments has been published [24]. Understanding adoption and long-term use is vital in order to maximize use of built environments. Longitudinal qualitative research is recommended for this purpose, such as that planned in the protocol paper [57] for a study included in this review [37,38].

It is often impossible to find comparison groups in natural experiments that have a change in exposure acting in the opposite direction (e.g., a community that receives a new supermarket versus another community that is similar in almost all aspects but has a supermarket removed), in a similar community (e.g., same SES background). Detailed descriptions of built environment changes are essential in this type of research and studies need to consider the potential impact of other significant changes in built infrastructure, other than the exposure under investigation, on outcomes. Ideally, these other changes should be measured using an objective measure, for example using time-varying analyses as a measure of confounding [58].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

The MRC guidelines recognize the complexity of systematically reviewing natural experimental literature [26,27]. A rigorous and systematic approach was taken in this review; however, the findings of this review should be considered in light of potential limitations. Risk of bias items used in this review included validated items and newly developed non-validated items appropriate for natural experiments, which reflected key biases highlighted in natural experiment guidelines [26,27]. Using this tool allowed discussion of results in the context of study reporting quality and similar to a recently published systematic review of built environment exposures on physical activity and active transport [20], identified limitations in study quality across included studies that should be considered when designing future evaluations. Also, similar to this recently published review [20], we excluded studies that reported enhancing environmental changes with other components, including local awareness campaigns, to examine the impact of built neighborhood environment changes alone. It is possible that some studies including such components in addition to built environment changes were included due to omitting such components from their reporting. It is acknowledged that multi-component interventions result in the most impactful health behavior change programs [53,59,60]. The aim of this review was to restrict inclusion to those studies only assessing the impact of changes to public neighborhood built environment features. Had multi-component studies been included, it would not be possible to determine changes attributed to the built environment elements on lifestyle behaviors. Studies were included if it was stated that participants were neighborhood residents regardless of if a definition was reported or not. Only peer-reviewed articles were included in this review to ensure a level of quality—important findings may have been missed by omission of grey literature. Individual authors were not contacted for additional study information and thus it was not clear for several risk of bias items if measures were not in place to minimize bias, or were not reported on. Some studies may have been rated as having a high risk of bias due to limited reporting in associated articles rather than actual study design and conduction. The challenges of summarizing findings across natural experiments were particularly noted in this review, as was the case in a similar review specifically of physical activity and active transport built environment interventions [20], due to the vast and varying ways of reporting on the same outcome (e.g., for physical activity—percentage residents using a park, total time spent walking, bouts of activity) and quality of reporting. Although estimation of effect size across studies was not possible for this reason, the findings of this review can be used to inform research priorities in future and provides a qualitative interpretation summarizing current evidence on the impact of built environment on physical activity and diet from natural experiments.

5. Conclusions

Identifying the impact of built environment change alone on physical activity and diet outcomes is important for establishing the level of focus and investment that should be made on built environment in socio-ecological interventions. The quality of evidence published to date, including natural experiments, is scarce and limited. It would be surprising if the built environment were not an important standalone driver of physical activity and diet, but available evidence in the research literature thus far is not strong enough to lead to a definitive conclusion. Further research is needed to develop a consistent approach to measure the same outcomes (e.g., consensus for how to measure and report physical activity in these types of studies), so that pooled meta-analyses can be conducted.

Taking into consideration the differences in design and reporting, the findings of this review cannot definitively support nor rule out the existing belief among urban planners and policy makers, that changes to the built environment are powerful interventions not only for preventive health and well-being, but also for improving physical activity and diet outcomes at the community-level. The interventions in this review were largely ineffective and therefore such approaches require further testing. It may be that the impact of changing built environment on health outcomes and physical activity and diet is small, however, if the change affects large population numbers, even small changes in behaviors will have the potential to reduce disease risk and prevalence at a population level [61]. The findings of this review are useful for researchers and policy makers to assist in effectively planning longitudinal evaluations of natural experiments involving built environment changes.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/2/217/s1, Table S1: Web of Knowledge search strategy and reasons for exclusion of articles, Table S2: Reasons for exclusion of articles at the final screening phase of the initial search in 2014.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Page, Brendon Hyndman, Mel Dunshea and Fran Moran for providing assistance with the initial screening of a sub-set of titles and abstracts and/or rating of risk of bias in a sub-set of included studies. Thomas Astell-Burt is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Boosting Dementia Research Leadership Fellowship (#1140317). Xiaoqi Feng is supported by a National Heart Foundation of Australia Fellowship (#100948). Thomas Astell-Burt and Xiaoqi Feng are also jointly supported by an NHMRC Project Grant (#1101065) and Hort Innovation Limited with co-investment from the University of Wollongong (UOW) Faculty of Social Sciences, the UOW Global Challenges initiative and the Australian Government (project number #GC15005).

Author Contributions

F.M. and T.A.B. developed the study focus. F.M., A.C., A.B., B.P., G.D., D.M., T.S., E.S.G., G.S.K., T.A.B., J.M.G. and X.F. were all involved in article screening, data extraction and data extraction checking. F.M. led the drafting of the manuscript, helped by E.S.G., X.F. and D.M. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jackson, R.J.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Frumkin, H. Health and the Built Environment: 10 Years After. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1542–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Kolt, G.S. Green space is associated with walking and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in middle-to-older-aged adults: Findings from 203,883 Australians in the 45 and Up Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, A.C.; de Almeida, S.L.; Latorre Mdo, R.; Jaime, P.C. The role of the local retail food environment in fruit, vegetable and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelens, B.E.; Vernez Moudon, A.; Kang, B.; Hurvitz, P.M.; Zhou, C. Relation Between Higher Physical Activity and Public Transit Use. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, L.; Compernolle, S.; Deforche, B.; Mackenbach, J.D.; Lakerveld, J.; Brug, J.; Roda, C.; Feuillet, T.; Oppert, J.M.; Glonti, K.; et al. Built environmental correlates of cycling for transport across Europe. Health Place 2017, 44, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdinand, A.O.; Sen, B.; Rahurkar, S.; Engler, S.; Menachemi, N. The relationship between built environments and physical activity: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e7–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Rutter, H.; Compernolle, S.; Glonti, K.; Oppert, J.M.; Charreire, H.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Brug, J.; Nijpels, G.; Lakerveld, J. Obesogenic environments: A systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Palmer, S.; Gallacher, J.; Marsden, T.; Fone, D. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ. Int. 2016, 96, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcaya, M.C.; Tucker-Seeley, R.D.; Kim, R.; Schnake-Mahl, A.; So, M.; Subramanian, S.V. Research on neighborhood effects on health in the United States: A systematic review of study characteristics. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 168, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macintyre, S. Good intentions and received wisdom are not good enough: The need for controlled trials in public health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, D.; Li, C.Q.; Wolch, J.; Kahle, C.; Jerrett, M. A Spatial Autocorrelation Approach for Examining the Effects of Urban Greenspace on Residential Property Values. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2010, 41, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.F.; Martin, B.W.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Cummins, S.; Ferrell, C.; Findlay, A.; Higgins, C.; Hoy, C.; Kearns, A.; Sparks, L. Natural experiments: An underused tool for public health? Public Health 2005, 119, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pell, J.P.; Haw, S.; Cobbe, S.; Newby, D.E.; Pell, A.C.; Fischbacher, C.; McConnachie, A.; Pringle, S.; Murdoch, D.; Dunn, F.; et al. Smoke-free Legislation and Hospitalizations for Acute Coronary Syndrome. NEJM 2008, 359, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Kolt, G.S.; Jalaludin, B. Does rising crime lead to increasing distress? Longitudinal analysis of a natural experiment with dynamic objective neighbourhood measures. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 138, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Panter, J.; Sharp, S.J.; Ogilvie, D. Effectiveness and equity impacts of town-wide cycling initiatives in England: A longitudinal, controlled natural experimental study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galster, G.; Hedman, L. Measuring Neighbourhood Effects Non-experimentally: How Much Do Alternative Methods Matter? Hous. Stud. 2013, 28, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Glass, T.A.; Curriero, F.C.; Stewart, W.F.; Schwartz, B.S. The built environment and obesity: A systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place 2010, 16, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, J.; Thompson, S.M.; Jalaludin, B. Healthy Built Environments: A Review of the Literature; Healthy Built Environments Program; UNSW: Sydney, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Hosking, J.; Woodward, A.; Witten, K.; MacMillan, A.; Field, A.; Baas, P.; Mackie, H. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport—An update and new findings on health equity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, J.S.; Anderson, J.; Hunter, R.F.; French, D.P. The effect of changing the built environment on physical activity: A quantitative review of the risk of bias in natural experiments. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys, D.K.; Panter, J.; Sahlqvist, S.; Goodman, A.; Ogilvie, D. Changing the environment to improve population health: A framework for considering exposure in natural experimental studies. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0; The Cochrance Collaboration: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P.; Cooper, C.; Gunnell, D.; Haw, S.; Lawson, K.; Macintyre, S.; Ogilvie, D.; Petticrew, M.; Reeves, B.; Sutton, M.; et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: New Medical Research Council guidance. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, P.; Cooper, C.; Gunnell, D.; Haw, S.; Lawson, K.; Macintyre, S.; Ogilvie, D.; Petticrew, M.; Reeves, B.; Sutton, M.; et al. Using Natural Experiments to Evaluate Population Health Interventions: Guidance for Producers and Users of Evidence; M.R. Council: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Quigg, R.; Reeder, A.I.; Gray, A.; Holt, A.; Waters, D. The Effectiveness of a Community Playground Intervention. J. Urban Health-Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2012, 89, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dill, J.; McNeil, N.; Broach, J.; Ma, L. Bicycle boulevards and changes in physical activity and active transportation: Findings from a natural experiment. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, S74–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, S.; Findlay, A.; Petticrew, C.H.M.; Sparks, L.; Thomson, H. Reducing inequalities in health and diet: Findings from a study on the impact of a food retail development. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 402–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Petticrew, M.; Higgins, C.; Findlay, A.; Sparks, L. Large scale food retailing as an intervention for diet and health: Quasi-experimental evaluation of a natural experiment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, S.; Flint, E.; Matthews, S.A. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.B.; Werner, C.M. A new rail stop: Tracking moderate physical activity bouts and ridership. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, A.; Boarnet, M.G.; Houston, D. New light rail transit and active travel: A longitudinal study. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 92, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbidge, S.K.; Goulias, K.G. Evaluating the Impact of Neighborhood Trail Development on Active Travel Behavior and Overall Physical Activity of Suburban Residents. Trans. Res. Rec. 2009, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Herring, A.H.; Huston, S.L. Evaluating change in physical activity with the building of a multi-use trail. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Sahlqvist, S.; Ogilvie, D. Who uses new walking and cycling infrastructure and how? Longitudinal results from the UK iConnect study. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Sahlqvist, S.; Ogilvie, D.; iConnect Consortium. New walking and cycling routes and increased physical activity: One- and 2-year findings from the UK iConnect Study. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e38–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, J.M.; Stokes, R.J.; Cohen, D.A.; Kofner, A.; Ridgeway, G.K. The effect of light rail transit on body mass index and physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazin, J.; Garcia, L.M.; Florindo, A.A.; Peres, M.A.; Guimarães, A.C.; Borgatto, A.F.; Duarte Mde, F. Effects of a new walking and cycling route on leisure-time physical activity of Brazilian adults: A longitudinal quasi-experiment. Health Place 2016, 39, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, H.J.; Tribby, C.P.; Brown, B.B.; Smith, K.R.; Werner, C.M.; Wolf, J.; Wilson, L.; Oliveira, M.G. Public transit generates new physical activity: Evidence from individual GPS and accelerometer data before and after light rail construction in a neighborhood of Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. Health Place 2015, 36, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.B.; Werner, C.M.; Tribby, C.P.; Miller, H.J.; Smith, K.R. Transit Use, Physical Activity, and Body Mass Index Changes: Objective Measures Associated with Complete Street Light-Rail Construction. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, S.T.; Shores, K.A. The impacts of building a greenway on proximate residents' physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 1092–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, A.E.; Jennings, R.; Smiley, A.W.; Medina, J.L.; Sharma, S.V.; Rutledge, R.; Stigler, M.H.; Hoelscher, D.M. Introduction of farm stands in low-income communities increases fruit and vegetable among community residents. Health Place 2012, 18, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrigley, N.; Warm, D.; Margetts, B.; Whelan, A. Assessing the impact of improved retail access on diet in a food desert: A preliminary report. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2061–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Warm, D.; Margetts, B. Deprivation, diet, and food-retail access: Findings from the Leeds food deserts study. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 151–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health Behaviours and Their Role in the Prevention of Chronic Disease; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Bonevski, B.; Randell, M.; Paul, C.; Chapman, K.; Twyman, L.; Bryant, J.; Brozek, I.; Hughes, C. Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booker, C.L.; Harding, S.; Benzeval, M. A systematic review of the effect of retention methods in population-based cohort studies. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brueton, V.C.; Tierney, J.F.; Stenning, S.; Meredith, S.; Harding, S.; Nazareth, I.; Rait, G. Strategies to improve retention in randomised trials: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.F.; Christian, H.; Veitch, J.; Astell-Burt, T.; Hipp, J.A.; Schipperijn, J. The impact of interventions to promote physical activity in urban green space: A systematic review and recommendations for future research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 124, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.; Steinbach, R.; Jones, A.; Edwards, P.; Kelly, C.; Nellthorp, J.; Goodman, A.; Roberts, H.; Petticrew, M.; Wilkinson, P. On the Buses: A Mixed-Method Evaluation of the Impact of Free Bus Travel for Young People on the Public Health; NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson, R.C.; Baker, E.A.; Boyd, R.L.; Caito, N.M.; Duggan, K.; Housemann, R.A.; Kreuter, M.W.; Mitchell, T.; Motton, F.; Pulley, C.; et al. A community-based approach to promoting walking in rural areas. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merom, D.; Bauman, A.; Vita, P.; Close, G. An environmental intervention to promote walking and cycling—The impact of a newly constructed Rail Trail in Western Sydney. Prev. Med. 2003, 36, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiehe, S.E.; Carroll, A.E.; Liu, G.C.; Haberkorn, K.L.; Hoch, S.C.; Wilson, J.S.; Fortenberry, J.D. Using GPS-enabled cell phones to track the travel patterns of adolescents. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2008, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrukh, M.; Farooq, T.A.; Saeed, A.; Sultan, F.; Inam, A.; Afzal, M.; Nadeem, U.; Khan, S.A. Working Paper: Using Smart Phones to Monitor Attendance in Public Facilities; Lahore University of Management Sciences: Lahore, Pakistan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie, D.; Bull, F.; Cooper, A.; Rutter, H.; Adams, E.; Brand, C.; Ghali, K.; Jones, T.; Mutrie, N.; Powell, J.; et al. Evaluating the travel, physical activity and carbon impacts of a ‘natural experiment’ in the provision of new walking and cycling infrastructure: Methods for the core module of the iConnect study. BMJ Open 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Laraia, B.A.; Mujahid, M.S.; Blanchard, S.D.; Warton, E.M.; Moffet, H.H.; Karter, A.J. Is a reduction in distance to nearest supermarket associated with BMI change among type 2 diabetes patients? Health Place 2016, 40, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröer, S.; Haupt, J.; Pieper, C. Evidence-based lifestyle interventions in the workplace: An overview. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, S.F.L.; Penney, T.L.; McHugh, T.L.; Sharma, A.M. Effective weight management practice: A review of the lifestyle intervention evidence. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).