Abstract

Research findings concerning burnout prevalence rate among nurses from the medical area are contradictory. The aim of this study was to analyse associated factors, to determine nurse burnout levels and to meta-analyse the prevalence rate of each burnout dimension. A systematic review, with meta-analysis, was conducted in February 2018, consulting the next scientific databases: PubMed, CUIDEN, CINAHL, Scopus, LILACS, PsycINFO and ProQuest Health & Medical Complete. In total, 38 articles were extracted, using a double-blinded procedure. The studies were classified by the level of evidence and degrees of recommendation. The 63.15% (n = 24) of the studies used the MBI. High emotional exhaustion was found in the 31% of the nurses, 24% of high depersonalisation and low personal accomplishment was found in the 38%. Factors related to burnout included professional experience, psychological factors and marital status. High emotional exhaustion prevalence rates, high depersonalisation and inadequate personal accomplishment are present among medical area nurses. The risk profile could be a single nurse, with multiple employments, who suffers work overload and with relatively little experience in this field. The problem addressed in this study influence the quality of care provided, on patients’ well-being and on the occupational health of nurses.

1. Introduction

Stress forms part of daily life and might be considered one of the great pandemics of the 21st century [1]. In the workplace, it can affect health, personal well-being and job satisfaction, and in severe cases may provoke the appearance of burnout syndrome [2].

Burnout is composed of the following elements—emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalisation (D) and low personal accomplishment (PA)—and appears as a result of chronic work stress [3]. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [4] is the most commonly used questionnaire to assess the syndrome. Burnout affects workers in a growing number of professions [5] and nurses and physicians are among the most often affected [6,7]. Certain personal factors (such as gender, age, marital status, having children and personality) or external factors (such as medical records, training, work stress) may correlate with burnout development in nurses and physicians [7,8,9]. Nurses usually work in a specific medical area within a hospital, divided into units or services, according to the systems or pathologies treated. Each service has different characteristics, and these, too, can influence burnout levels [7,10,11].

The medical area (MA) incorporates the general units of a hospital complex, including services of similar characteristics and working conditions in terms of structure, organisation, work shifts, salaries, workload and type of care [12]. The only differentiating aspect within the MA would be the type of patient and the pathology treated, which determines the service providing the treatment [13].

There are conflicting research findings as to whether the appearance of burnout syndrome among MA nurses should be attributed to the type of patient [14] or to the continuous demands made on nurses by this type of hospitalisation [15], which do not usually occur in the emergency room or in primary care. The levels of burnout among MA personnel have a certain variability; although this makes the question more complex, it might be clarified by means of a meta-analysis [16,17].

Taking into account the above considerations, the present study has the following aims: to determine levels of burnout among MA nurses; to meta-analytically estimate the prevalence of EE, D and PA meta-analysis; and to determine the risk factors associated with each of these dimensions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Inclusion Criteria

A systematic review, with meta-analysis, was carried out in February 2018, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; the following are available as Supplementary Materials) [18]. The PubMed, CUIDEN, CINAHL, Scopus, LILACS, PsycINFO and ProQuest Health & Medical Complete databases were consulted.

The following inclusion criteria were applied in selecting appropriate studies for analysis: (a) there was no time restriction; (b) the studies should be written in English, Spanish or Portuguese; (c) they should be primary and quantitative; (d) they should provide data on risk factors of burnout syndrome or its prevalence; (e) they should be based on a sample of MA nurses or on a mixed sample in which the results for MA nurses are provided separately; (f) they should be conducted in the MA; (g) for the meta-analysis, they should provide independent data for prevalence for at least one of the three MBI dimensions of burnout (EE, D and PA). If the study did not use the MBI, it was included for the systematic review but not included for the meta-analysis because the domains and punctuations are not the same. No study was excluded depending on its response rate.

2.2. Search Strategy

The key terms used to identify the primary studies were “burnout” combined with “nurs*” and with the type of hospital service (“internal medicine”, “cardiology”, “pneumology”, “neurology”, “nephrology”, “dialysis”, “oncology”, “haematology”, “rheumatology”, “endocrinology”). To address the entire MA, the following search formula was also used: “burnout AND nurs* AND medical wards”. The search equations were applied without any restriction, taking into account both the title and the abstract.

2.3. Study Selection

Independently, two members of the research team, selected the studies following the recommendations of Cooper, Hedges and Valentine [19]. For each study selected, a forward and backward search was done. In cases of disagreement between these two team members regarding the final sample of studies to be analysed, a third researcher was consulted [20]. The studies were classified by the level of evidence and degrees of recommendation from the Oxford Center for Evidence-based Medicine (OCEBM) [21].

2.4. Data Coding

The data were formatted using a data coding manual, extracting the next variables: (a) authors; (b) year of publication; (c) language; (d) country where the study was done; (e) type of study; (f) sample size (nurses); (g) MA service in question (internal medicine, cardiology, pneumology, neurology, nephrology, oncology and/or haematology); (h) use of MBI (yes/no); (i) main results obtained, regarding burnout levels; (j) high presence of EE recorded; (k) high presence of D recorded; (l) low presence of PA recorded. The inter-investigator reliability of the data coding process was verified by the intra-class correlation coefficient (0.94) and Cohen’s kappa coefficient for the categorical variables (0.92).

2.5. Data Analysis

The study data were analysed using the StatsDirect software (StatsDirect Ltd, Cambridge, UK). First, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. Publication bias was determined by Egger’s linear regression. The prevalence of burnout and the corresponding confidence intervals were calculated by random-effects meta-analyses. Cochran Q test and the I2 index were used to calculate the heterogeneity of the sample.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

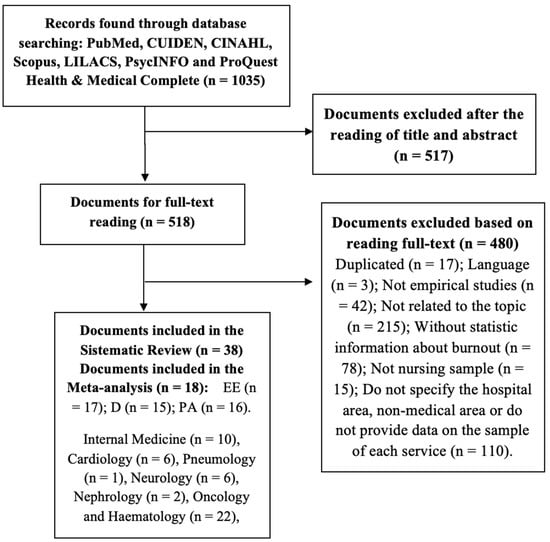

The search obtained ninitial = 1035 articles. After application of the exclusion and inclusion criteria, n = 38 remained for the systematic review and (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the study selection process.

All the studies included in our analysis were cross-sectional and descriptive, with the exception of three longitudinal cohorts. The 63.16% (n = 24) of the studies used the MBI. The others studies (n = 14) were divided as follows: the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) 7.90% (n = 3), the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory 5.26% (n = 2), the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory 2.63% (n = 1) of the studies and the rest 21.05% (n = 8) used questionnaires based on stress (Occupational Stressors Inventory, Moral Distress Scale-Revised, Nurse Stress Thermometer, etc.) and coping styles (Brief COPE, The Ways of Coping Questionnaire, Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire, etc.). Information on the level of evidence, the degree of recommendation and the main study results is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included.

3.2. Main Risk Factors and Dimensions of Burnout

The majority of studies in our analysis conclude that EE is the most common dimension of burnout [22,23,26,36,39,42,44,46,48,49,50,53]. Others report a higher score for the D dimension than EE or PA among MA nurses [28,29,40,41]. Finally, a significantly greater presence of low PA has been observed in most MA services [27,34,37,38,54,57].

The main risk factors identified are sociodemographic. Some authors believe that younger nurses are at greater risk of burnout [26,41,43], while others hold that nurses aged over 38–40 years are more vulnerable [33,34,50]. Similarly uneven results have been reported with respect to the influence of marital status [29,34,53]. Most studies highlight the protective influence of social and family support [23,31,35,45]. The gender influence is also not clear as some studies indicate that male nurses have higher burnout levels while others say that women have higher levels or that the differences are not statistically significant [22,26,38,52].

Occupational variables associated with burnout include working night shifts [22,43,55], multiple employment [33,38], a perceived lack of work-performance recognition [25,36] and length of experience/seniority [28].

Finally, several papers observe that personality variables, together with anxiety and depression, may have a negative impact on MA services [26,28,33,36,44,46,59], although others deny that this type of variable influences the development of burnout [34] or believe its influence is slight [49].

3.3. Meta-Analysis of Burnout Prevalence

In total, kfinal = 6092 nurses were included in our meta-analysis (internal medicine k = 1102, cardiology k = 244, pneumology k = 7, neurology k = 528, nephrology k = 264, oncology and/or haematology k = 3947). The meta-analysis was based on 21 samples for EE, 18 for D and 20 for low PA (see Table 1).

In our sensitivity analysis, the prevalence value obtained did not change significantly when each of the studies was eliminated from the analysis and no publication bias were detected with Egger’s test. The following values were obtained: EE = −7.13, p = 0.07; D = −0.69, p = 0.88; PA = 5.36, p = 0.11.

For heterogeneity, the following values were obtained by Cochran’s Q test: EE = 789.31, p < 0.001; D = 1162.44, p < 0.001; PA = 908.68, p < 0.001. The I2 index was 97.5% for EE, 98.5% for D and 97.9% for PA.

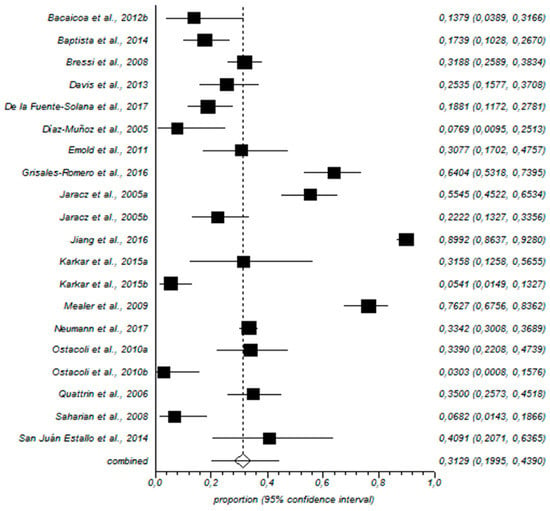

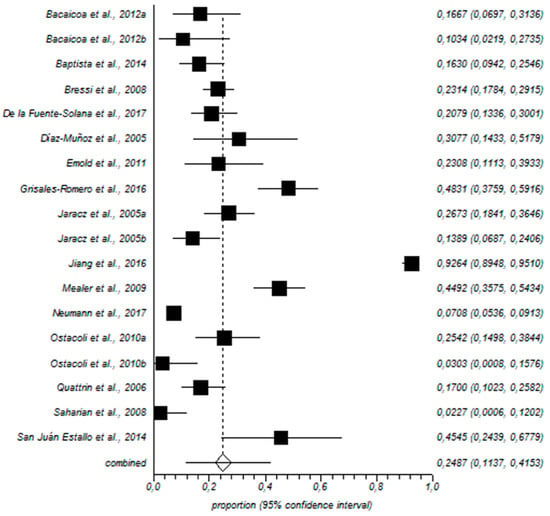

For prevalence, high EE was recorded among 31% of the nurses (95% CI = 19–43%), as shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows that high levels of D were recorded among 24% of the nurses (95% CI = 10–41%).

Figure 2.

Forestplot of high EE.

Figure 3.

Forestplot for high D.

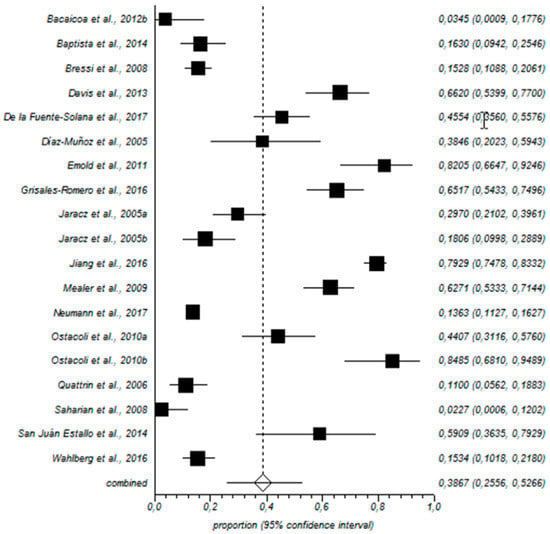

Low PA prevalence rate was 38% (95% CI = 25–52%) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forestplot for low PA.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, no previous meta-analysis studies have been done about burnout syndrome among MA nurses. We obtained a prevalence of EE of 31% among MA nurses, which is similar to other studies with emergency nurses [17] and higher to those working in primary care units [11]. Some authors have reported that EE is lower in the MA than in more specialised services [60]. However, nursing from hospital wards feel that units’ tasks (such as computers work and documentation) reduce the time that they can spend with patients what make nurses feel powerlessness and favour EE [61]. Nurses in hospital units also feel that they have too much workload, which can lead work stress, and increase EE [62].

The prevalence of D in the sample was 24%, lower than emergency nurses [17] but higher than primary care nurses [11]. In some countries, nurses from MA is responsible for a higher number of beds and patients than in other services [63], a situation that contributes to overload and consequent burnout [64]. Furthermore, visiting times for MA services are flexible, allowing the constant entry and exit of family members, which may make nurse-patient relations colder and more distant [65]. In addition, the organisational and structural distribution of the hospital service may hamper relations of trust between nurses and patients [66]. In addition, computer and documentation tasks, can make nurses feel that they cannot look after their patients [61].

The presence of low PA among MA nurses was 38%, showing that MA nurses are less accomplished that emergency or primary care nurses [11,17] and being the most affected burnout dimension. Previous studies have highlighted feelings of dissatisfaction and abandonment among MA nurses when their work is distributed impersonally, by tasks [67]. Job satisfaction is much greater when nurses feel they are providing personalised care [67]. Indeed, research has shown that establishing ties with patients and spending more time with them enhances nurses’ PA [61].

Among the occupational variables relevant to burnout among MA nurses, one that is prominent but has so far received very little research attention is that of multiple employment. Due to a lack of job security, reduced working hours and limited work availability in the public sector [68], many young MA nurses are forced to find work in both private and public institutions, a situation that is prejudicial to their health status [69] and contributes to the emergence of burnout [70].

Regarding the relation between personality variables and the different dimensions of burnout, our study obtained results comparable with those published previously [71], although the impact of responsibility can be a problem in these medical services, due to the work overload often presented, which can generate a high level of stress and hence burnout [72].

In relation to results’ applicability, nurse managers should consider that MA units where nurses have a high workload, mainly the documentary and computer work with low nurse-patient contact, tends to favor burnout [61]. Consequently, they should take measures that favor a better work environment for nurses, with fewer documentary tasks, which will allow nurses to spend more time taking care of their patients. This may increase their personal fulfillment. Also, regarding the levels of burnout, nurse manager should promote and implement different interventions to reduce burnout like orientation programs or professionals support groups [16]. Reducing and preventing burnout its negative effects on staff and patient health will be avoided [3], improving health quality and nursing care results.

Nursing professionals should also be aware that daily tasks in a medical unit do not only include patient care [12,13]. Nurses say that they learned how to take care of patients and that documentation and computer tasks subtract their time for patients, favoring low personal accomplishment [61]. To create more realistic expectations about nursing daily tasks, the content of the nursing degree should also include more information and education about documentation and computer tasks. Another task related to nursing care is the prescription of medicines, a new competence for nursing in Europe. Medicines prescription has been already identified as a stress source in doctors due to possible errors, and it may happen the same in nurses [73]. However, it can also be a motivation source for nurses because it is a way of professional development.

Future research should pay attention to interventions that can prevent burnout development in MA nurses and interventions that can reduce burnout suffering. For example, some interventions (such as mindfulness, meditation, resilience and coping programs) that have demonstrate to be effective for compassion fatigue and burnout among healthcare, emergency and community service workers should be taking into account for medical area nurses [74]. It would be also of great interest to analyze which personality factors are more suitable for working in MA units without developing burnout. Finally, another important thing about meta-analytic future researches is the importance of guarantee their replicability, which will be possible by including detailed information in primary research papers [75].

5. Conclusions

MA nurses are mostly affected by low levels of PA, followed by high EE and high D. There is a greater prevalence of burnout among single persons, those in multiple employment, those who suffer work overload and those who have relatively little experience in this field.

The problem addressed in this study has impact on the quality of care provided, on patients’ well-being and on nurses occupational health. Since the MA contains most of the hospital’s long-term services, more preventive measures are needed in this area. To achieve these goals, there must be organisational, healthcare and occupational changes, based on current scientific evidence.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/12/2800/s1, Table S1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-P., L.R.-B. and E.I.D.l.F.; Data curation, J.L.G.-U., G.R.C. and G.A.C.-D.l.F.; Formal analysis, L.R.-B., J.L.G.-U. and G.R.C.; Funding acquisition, G.R.C. and E.I.D.l.F.; Investigation, L.R.-B., J.L.G.-U., E.I.D.l.F. and G.A.C.-D.l.F.; Methodology, L.R.-B., J.L.G.-U., E.I.D.l.F. and G.A.C.-D.l.F.; Project administration, J.M.-P., J.L.G.-U., G.R.C., E.I.D.l.F. and G.A.C.-D.l.F.; Resources, L.R.-B., J.L.G.-U. and E.I.D.l.F.; Software, J.L.G.-U.; Supervision, G.R.C., E.I.D.l.F. and G.A.C.-D.l.F.; Validation, G.R.C., E.I.D.l.F. and G.A.C.-D.l.F.; Visualization, G.R.C., E.I.D.l.F. and G.A.C.-D.l.F.; Writing—original draft, J.M.-P. and L.R.-B.; Writing—review & editing, L.R.-B. and G.A.C.-D.l.F. All authors listed meet the authorship criteria and are in agreement with the submission of the manuscript. All of them have done substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, according to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and to the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). All authors have given the final approval of the version to be published; and all authors are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This research was funded by Junta de Andalusia-Spain, Excellence Research Project (P11HUM-7771).

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the corresponding author’s doctoral dissertation that is in development for the degree of Doctorate in Psychology. We thank to PhD Luis Albendín-García and Angel Martínez for their help in the codification process of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Detzel, T.; Carlotto, M.S. Síndrome de burnout em trabalhadores da enfermagem de um hospital geral [Burnout syndrome in nursing staff in a general hospital]. Rev. SBPH 2008, 11 (Suppl. 1), 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, H.S.; Cunningham, C.J. Linking nurse leadership and work characteristics to nurse burnout and engagement. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65 (Suppl. 1), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14 (Suppl. 3), 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Occup. Behav. 1981, 2 (Suppl. 2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; San Luis, C.; Lozano, L.M.; Vargas, C.; García, I.; De la Fuente, E.I. Evidence for factorial validity of Maslach Burnout Inventory and burnout levels among health workers. Rev. Lat. Am. Psicol. 2014, 46 (Suppl. 1), 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Vargas, C.; San Luis, C.; García, I.; Cañadas, G.R.; De La Fuente, E.I. Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52 (Suppl. 1), 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.S.; Bachu, R.; Adikey, A.; Malik, M.; Shah, M. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: A review. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 2018, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Vargas, C.; De la Fuente, E.I.; Fernández-Castillo, R. Age as a Risk Factor for Burnout Syndrome in Nursing Professionals: A Meta-Analytic Study. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40 (Suppl. 2), 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Ortega, E.; Ramírez-Baena, L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Vargas, C.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Gender, marital status and children as risk factors for burnout in nurses: A meta-analytic study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albendín, L.; Gómez, J.L.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Cañadas, G.R.; San Luis, C.; Aguayo, R. Bayesian prevalence and burnout levels in emergency nurses. A systematic review. Rev. Latinoam. Am. Psicol. 2016, 48 (Suppl. 2), 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Reyes, C.S.; San Luis-Costas, C.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Albendín-García, L.; Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naz, S.; Hashmi, A.M.; Asif, A. Burnout and quality of life in nurses of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2016, 66, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drach-Zahavy, A. How does service workers’ behavior affect their health? Service climate as moderator in the service behavior-health relationships. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 2), 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandoy-Crego, M.; Clemente, M.; Mayán-Santos, J.M.; Espinosa, P. Personal determinants of burnout in nursing staff at geriatric centers. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 48 (Suppl. 2), 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S.P. Nurse retention and satisfaction in Ecuador: Implications for nursing administration. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22 (Suppl. 1), 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Ortega-Campos, E.M.; Cañadas, G.R.; Albendín-García, L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in oncology nursing: A meta-analytic study. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27 (Suppl. 5), 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Albendín-García, L.; Vargas-Pecino, C.; Ortega-Campos, E.M.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in emergency nurses: A meta-analysis. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37 (Suppl. 1), e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6 (Suppl. 7), e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.V.; Valentine, J.C. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 2nd ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey, M.W.; Wilson, D. Practical Meta-Analysis: Applied Social RESEARCH Methods, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B.; Ball, C.; Badenoch, D.; Straus, S.; Haynes, B.; Dawes, M. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (CEBM). Levels of evidence. BJU Int. 2011, 107 (Suppl. 5), 870. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Verdugo, L.P.; Bocanegra, P.; Migdolia, B. Prevalencia de desgaste profesional en personal de enfermería de un hospital de tercer nivel de Boyacá, Colombia. Enferm. Glob. 2013, 12 (Suppl. 29), 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bacaicoa, P.; Díaz, V.; Gea, M.; Linares, J.; Araya, E.; Alba, J.F.; Marrero, M. Comparativa y análisis del síndrome burnout entre el personal de enfermería en cardiología de dos hospitales de tercer nivel. Rev. Enferm. Cardiol. 2012, 19 (Suppls. 55–56), 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, P.; Tito, R.; Felli, V.; Silva, F.; Silva, S. The shift work and the Burnout syndrome. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 71 (Suppl. 1), A108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Yap, C.; Mason, S. Examining the sources of occupational stress in an emergency department. Occup. Med. (Lond) 2016, 66 (Suppl. 9), 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bressi, C.; Manenti, S.; Porcellana, M.; Cevales, D.; Farina, L.; Pescador, L. Haemato-oncology and burnout: An Italian survey. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98 (Suppl. 6), 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.; Lind, B.; Sorensen, C. A comparison of burnout among oncology nurses working in adult and pediatric inpatient and outpatient settings. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2013, 40 (Suppl. 4), E303–E311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Cañadas, G.R.; Albendín-García, L.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Burnout and its relationship with personality factors in oncology nurses. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 30, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Muñoz, M.J. Síndrome del quemado en profesionales de Enfermería que trabajan en un hospital monográfico para pacientes cardíacos. Nure Inv. 2005, 18 (Suppl. 1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. The role of psychological factors in oncology nurses’ burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 28, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, E.J. Perceived sources of stress among pediatric oncology nurses. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 1993, 10 (Suppl. 3), 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emold, C.; Schneider, N.; Meller, I.; Yagil, Y. Communication skills, working environment and burnout among oncology nurses. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15 (Suppl. 4), 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, D.; Maia, E. Nursing professionals’ anxiety and feelings in terminal situations in oncology. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15 (Suppl. 6), 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, F.; Wellisch, D.; Pasnau, R.; Leibowitz, B. Preventing nursing burnout: A challenge for liaison psychiatry. Gen. Hosp. Psychiat. 1983, 5 (Suppl. 2), 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, G.; Barbosa, F.; Vieira, M. Personal determinants of nurses’ burnout in end of life care. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 18 (Suppl. 5), 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, S.D.F.S.; Santos, M.M.M.C.C.; Carolino, E.T.D.M.A. Psycho-social risks at work: Stress and coping strategies in oncology nurses. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2013, 21 (Suppl. 6), 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Sánchez, M.; Álamo-Santos, M.; Amador-Bohórquez, M.; Ceacero-Molina, F.; Mayor-Pascual, A.; Muñoz-González, A.; Izquierdo-Atienza, M. Estudio de seguimiento del desgaste profesional en relación con factores organizativos en el personal de enfermería de medicina interna. Rev. SEMST 2009, 55, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisales-Romero, H.; Muñoz, Y.; Osorio, D.; Robles, E. Síndrome de Burnout en el personal de enfermería de un hospital de referencia Ibagué, Colombia, 2014. Enferm. Glob. 2016, 41 (Suppl. 1), 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaracz, K.; Gorna, K.; Konieczna, J. Burnout, stress and styles of coping among hospital nurses. Ann. Acad. Med. Bialostoc. 2005, 50 (Suppl. 1), 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Li, C.; Gu, Y.; Lu, H. Nurse satisfaction and burnout in Shanghai neurology wards. Rehabil. Nurs. 2016, 41 (Suppl. 2), 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoc, A.; Yilmaz, M.; Alcalar, N.; Esen, B.; Kayabasi, H.; Sit, D. Burnout syndrome among hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis nurses. Iran J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 10 (Suppl. 6), 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Karkar, A.; Dammang, M.L.; Bouhaha, B.M. Stress and burnout among hemodialysis nurses: A single-center, prospective survey study. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2015, 26 (Suppl. 1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousloglou, S.A.; Mouzas, O.D.; Bonotis, K.; Roupa, Z.; Vasilopoulos, A.; Angelopoulos, N.V. Insomnia and burnout in Greek nurses. Hippokratia 2014, 18 (Suppl. 2), 150–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Książek, I.; Stefaniak, T.J.; Stadnyk, M.; Książek, J. Burnout syndrome in surgical oncology and general surgery nurses: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15 (Suppl. 4), 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutluturkan, S.; Sozeri, E.; Uysal, N.; Bay, F. Resilience and burnout status among nurses working in oncology. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2016, 15 (Suppl. 1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealer, M.; Burnham, E.L.; Goode, C.J.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26 (Suppl. 12), 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowska, I.; Rasinska, R.; Glowacka, M.D. The influence of factors of work environment and burnout syndrome on self-efficacy of medical staff. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2016, 23 (Suppl. 2), 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, J.L.; Mau, L.W.; Virani, S.; Denzen, E.M.; Boyle, D.A.; Majhail, N.S. Burnout, moral distress, work-life balance, and career satisfaction among hematopoietic cell transplantation professionals. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017, 24 (Suppl. 4), 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostacoli, L.; Cavallo, M.; Zuffranieri, M.; Negro, M.; Sguazzotti, E.; Furlan, P.M. Comparison of experienced burnout symptoms in specialist oncology nurses working in hospital oncology units or in hospices. Palliat. Support. Care 2010, 8 (Suppl. 4), 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrin, R.; Zanini, A.; Nascig, E.; Annunziata, M.A.; Calligaris, L.; Brusaferro, S. Level of burnout among nurses working in oncology in an Italian region. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2006, 33 (Suppl. 4), 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.B.; Chaves, E.C. Stressing factors and coping strategies used by oncology nurses. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2008, 16 (Suppl. 1), 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadati, A.K.; Hemmati, S.; Rahnavard, F.; Lankarani, K.B.; Heydari, S.T. The impact of demographic features and environmental conditions on rates of nursing burnout. SEMJ 2016, 17 (Suppl. 3), e37882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraian, A.; Fazelzadeh, A.; Mehdizadeh, A.R.; Toobaee, S.H. Burnout in hospital nurses: A comparison of internal, surgery, psychiatry and burns wards. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2008, 55 (Suppl. 1), 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjuán-Estallo, L.; Arrazola-Alberdi, O.; García-Moyano, L.M. Prevalencia del síndrome del burnout en el personal de enfermería del servicio de cardiología, neumología y neurología del Hospital San Jorge de Huesca. Enferm. Glob. 2014, 13 (Suppl. 36), 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehlen, S.; Vordermark, D.; Schäfer, C.; Herschbach, P.; Bayerl, A.; Zehentmayr, F. Job stress and job satisfaction of physicians, radiographers, nurses and physicists working in radiotherapy: A multicenter analysis by the DEGRO Quality of Life Work Group. Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 4 (Suppl. 1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirilla, J. Moral distress in nurses providing direct care on inpatient oncology units. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18 (Suppl. 5), 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlberg, L.; Nirenberg, A.; Capezuti, E. Distress and coping self-efficacy in inpatient oncology nurses. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2016, 43 (Suppl. 6), 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Singh-Carlson, S.; Odell, A.; Reynolds, G.; Su, Y. Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among oncology nurses in the United States and Canada. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2016, 43 (Suppl. 4), E161–E169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jiang, A.; Shen, J. Prevalence and predictors of compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction among oncology nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 57, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.L.; Cannon, K.J.; Wellik, K.E.; Wu, Q.; Budavari, A.I. Burnout in inpatient-based versus outpatient-based physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Med. 2013, 8 (Suppl. 11), 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeter-Koponen, S.; Fredén, L. Long-term stress, burnout and patient-nurse relations: Qualitative interview study about nurses´ experience. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2005, 19, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partlak Günüsen, N.; Ustün, B.; Erdem, S. Work stress and emotional exhaustion in nurses: The mediatin role of internal locus of control. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2014, 28, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17 (Suppl. 1), 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentelsaz-Gallego, C.; Moreno-Casbas, T.; López-Zorraquino, D.; Gómez-García, T.; González-María, E. Percepción del entorno laboral de las enfermeras españolas en los hospitales del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Proyecto RN4CAST-España. Enferm. Clín. 2012, 22 (Suppl. 5), 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.C.; Fischer, F.M. A cohort study of psychosocial work stressors on work ability among Brazilian hospital workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2015, 58 (Suppl. 7), 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Kowalski, C.; Weeks, S.M.; Clarke, S.P. The relationship between nurse practice environment, nurse work characteristics, burnout and job outcome and quality of nursing care: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50 (Suppl. 12), 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.D.; Kutney-Lee, A.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Aiken, L.H. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff. (Milwood) 2011, 30 (Suppl. 2), 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazziano, E.S.; Ferraz Bianchi, E.R. Impacto del estrés ocupacional y burnout en enfermeros. Enferm. Global 2010, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.; Fronteira, I.; Jesus, T.S.; Buchan, J. Understanding nurses’ dual practice: A scoping review of what we know and what we still need to ask on nurses holding multiple jobs. Hum. Resour. Health 2018, 16 (Suppl. 1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeeley, M.F.; Perez, F.A.; Chew, F.S. The emotional wellness of radiology trainees: Prevalence and predictors of burnout. Acad. Radiol. 2013, 20 (Suppl. 5), 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Cant, R.; Payne, S.; O’Connor, M.; McDermott, F.; Shimoinaba, K. How death anxiety impacts nurses’ caring for patients at the end of life: A review of literature. Open Nurs. J. 2013, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Hajiesmaeili, M.; Kangasniemi, M.; Fornés-Vives, J.; Hunsucker, R.L.; Rahimibashar, F.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Farrokhvar, L.; Miller, A.C. MORZAK Collaborative. Effects of stress on critical care nurses: A national cross-sectional study. J. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 20 (Suppl. 10), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.; Thomas, B.; MacLure, K.; Pallivalapila, A.; El Kassem, W.; Awaisu, A.; McLay, J.S.; Wilbur, K.; Wilby, K.; Ryan, C.; et al. Perspectives of healthcare professionals in Qatar on causes of medication errors: A mixed methods study of safety culture. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocker, F.; Joss, N. Compassion fatigue among healthcare, emergency and community service workers: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016, 13, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grice, J.; Barrett, P.; Cota, L.; Felix, C.; Taylor, Z.; Garner, S.; Medellin, E.; Vest, A. Four Bad Habits of Modern Psychologists. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).