Abstract

The cyst of the canal of Nuck is an extremely rare female hydrocele, usually occurring in children, but also in adult women. It is caused by pathology of the canal of Nuck, which is the female equivalent to the male processus vaginalis. Due to its rarity and the lack of awareness among physicians, the cyst of the canal of Nuck is a seldom-encountered entity in clinical practice and is commonly misdiagnosed. We report on a case of cyst of the canal of Nuck in a 42-year-old woman, who presented with a painful swelling at her right groin. In addition, we conducted a review of the current available literature. This review gives an overview of the anatomy, pathology, diagnostics, and treatment of the cyst of the canal of Nuck. The aim of this review is not only to give a survey, but also to raise awareness of the cyst of the canal of Nuck and serve as a reference for medical professionals.

1. Introduction

A female hydrocele, namely cyst of the canal of Nuck, is an extremely rare entity that is not commonly encountered, especially in adults [1,2]. The origin of this disease is a pathology during embryogenesis [3,4]. Clinically, a female hydrocele typically manifests as a swelling in the groin or genital region [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], which allows for a variety of differential diagnoses. Due to its rarity, most health professionals are not aware of its existence and the cyst of the canal of Nuck is often misdiagnosed [7,8,9,12,23]. Precise diagnosis, including a thorough clinical examination and adequate radiological imaging, is required to accurately determine its presence. We report a case of a 42-year-old woman with a cyst of the canal of Nuck who presented to our department. This case provides insight into the various diagnostic procedures used, describes the surgical approach, and gives information about the histology. In addition, we conduct a review of the available literature to summarize the experiences of various physicians worldwide. This review provides basic knowledge about the anatomy and pathogenesis. Secondly, we provide an overview of the prevalence of the cyst of the canal of Nuck. We present commonly used classifications and describe the symptoms and key aspects of the diagnostics, which enable the distinction of possible differential diagnosis of inguinal or genital swelling in females. Furthermore, we examine the therapy and discuss different surgical approaches. This review should serve as compendium to facilitate the identification of female hydroceles and their treatment.

2. Methodology

Due to the extremely rare occurrence of the condition, we conducted a literature review to understand the anatomical background, the diagnostics and treatment methods in order to highlight best practice in medical care of this phenomenon. The following databases were used to search for and identify the included literature: PubMed, Google Scholar, and MEDLINE. No date restriction was imposed on the search. The result of our review is presented in narrative form in addition to our case report.

3. Case Report

A 42-year-old female patient was referred to the surgical outpatient department by her general practitioner due to a small swelling on the right groin, with a suspected inguinal hernia. The patient had observed this swelling two months before, and was suffering dragging pain in the affected area. With the exception of a hysterectomy and a bilateral salpingectomy by reason of multiple myoma uteri two years ago, there was neither a history of abdominal or pelvic surgery nor trauma, and the patient was otherwise in good health, without the appearance of nausea or vomiting. On physical examination, a non-reducible deep-seated round tumor was detected and located in the right inguinal region with a size of approximately 15 × 10 mm, with no pressure pain. The remaining abdominal examination was inconspicuous, with soft abdominal wall conditions and regular peristaltic sounds. There was no complaint of lower extremity weakness.

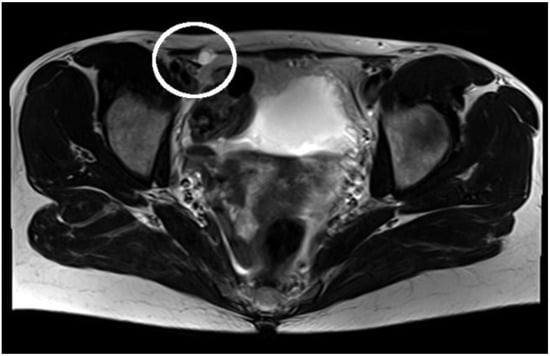

An ultrasound examination showed a hypoechoic cystic formation originated from the round ligament of the uterus in the right inguinal region without vascular flow or peristalsis. No changes in size or shape due to Valsalva maneuver could be determined. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained to further define the extent and nature of the cyst. The MRI revealed a 15 × 9 × 16 mm (transversal × sagittal × craniocaudal) well-defined, cystic formation with a peripheral contrast-enhancement within the medial border of her right inguinal ligament with no visible communication to the peritoneal cavity, compatible with a hydrocele of the Nuck canal. An axial T2-weighted MRI image of this hydrocele is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Axial T2-weighted MRI: cystic structure localized in the right inguinal canal, with no communication to the peritoneal cavity.

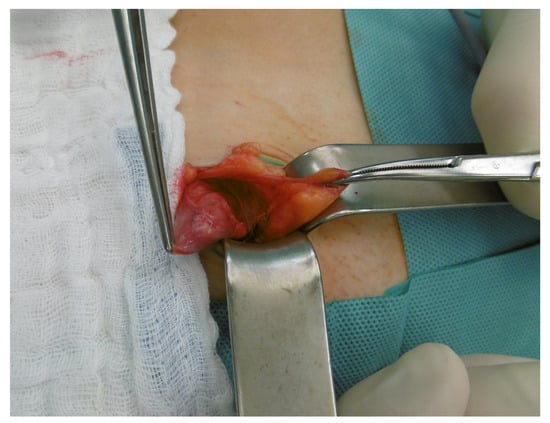

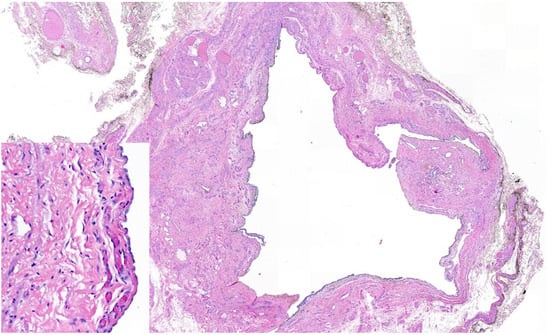

The patient was admitted to the ward for preparation for open surgery. Due to the anatomical conditions, an open surgical procedure was determined. Pre-surgically, the cyst was detected by ultrasonography, followed by a para-inguinal incision over the verified cyst formation. Intrasurgically, a small cyst appeared, between the external abdominal oblique and the right inguinal ligament. The cyst was dissected from the round ligament (Figure 2), followed by a ligation and completely excision. The internal inguinal ring defect was repaired without the use of a mesh, by suturing the tendon of the external abdominal oblique to the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament. Post-surgery, the cyst was opened with a scalpel, whereby a mucous, light-colored fluid was discharged. The histological intervention confirmed the diagnosis of cyst of the canal of Nuck. The image of the hematoxylin and eosin staining as well as a brief explanation is shown in Figure 3. In our follow-up 6 months after surgery, the patient was asymptomatic and satisfied with the treatment.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative picture of the cyst of the canal of Nuck after dissection from the round ligament.

Figure 3.

Histology hematoxylin and eosin staining: cystic structure localized within fibromuscular and adipose tissue demonstrating a flat to cuboidal mesothelial lining (left corner), consistent with a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck.

4. Review of Literature

4.1. Anatomical and Pathological Background

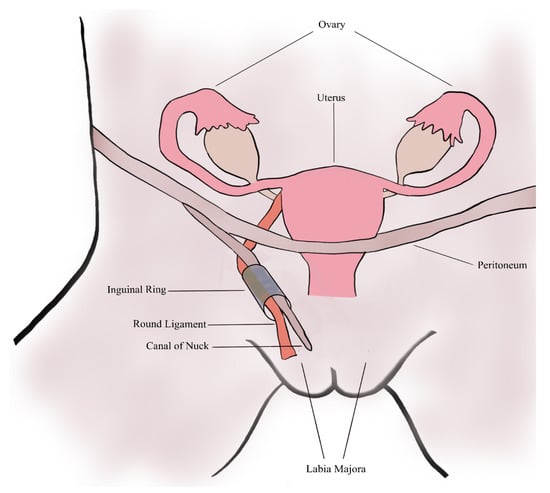

In 1691, Anton Nuck, a Dutch anatomist, was the first to describe the canal of Nuck [24]. The canal of Nuck is the female equivalent to the processus vaginalis in males, which usually disappears within the first year of life. It consists of an evagination of peritoneum, which is attached to the uterus by the round ligament, and proceeds through the inguinal ring alongside the round ligament into the labia majora [3,11]. Usually, the superior part of this outpouch obturates during or just before birth and disappears within the first year of life. In rare cases, this obturation fails, resulting in a persistence of the canal of Nuck [3,4,24] (Figure 4), which can cause the formation of a female hydrocele, namely the cyst of the canal of Nuck [1,13]. This phenomenon in women was first reported by Coley in 1892 [25]. Similar to the male hydrocele, a female hydrocele probably arises due to an imbalance of secretion from and absorption of fluid by the secretory membranes of the canal of Nuck [3,26]. Although this imbalance is most frequently idiopathic, disturbed lymphatic drainage caused by trauma, infection or inflammation are other possible reasons [11,16].

Figure 4.

A schematic of the female anatomy and the patent canal of Nuck.

4.2. Prevalence

According to the existing literature, only a few papers have reported the prevalence of the cyst of the canal of Nuck in children. Paparella et al. described a prevalence of 0.74% in 353 1–14-year-old female patients with inguinal swellings [27]. A similar finding was shown by Akkoyun et al., who reported a prevalence of 0.76% in a cohort of 0–16-year-old girls [23]. Huang et al. found a prevalence of the cyst of the canal of Nuck in 1% of girls aged from 1 month up to 14 years [28]. No data about the prevalence in adults are available. Therefore, no valid statement about the prevalence in adult females can be made as of yet.

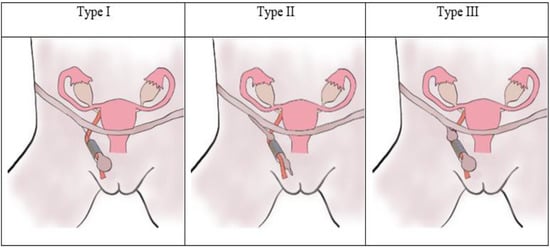

4.3. Classification

The commonly used classification was developed by Counseller and Black, who classified cysts of the canal of Nuck into three different types [29]. The most prevalent type forms a hydrocele along the round ligament without any communication with the peritoneal cavity. The second type communicates with the peritoneal cavity, and the third, the “hour-glass” type, is constricted by the inguinal ring, whereby one part communicates with the peritoneal cavity, while the other part does not. The three different types of cyst of the canal of Nuck are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic overview of the different types of cysts of the canal of Nuck as classified by Counseller and Black.

A recent classification was published by Wang et al. in 2021 [30], who subdivided the cyst of the canal of Nuck into four groups according to its anatomical position. Type A is located subcutaneously over the inguinal canal, Type B resides inside the inguinal canal, Type C is confined to the internal inguinal ring, and Type D extends from the internal inguinal ring to the inguinal canal or subcutaneously.

4.4. Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Methods

The clinical presentation of a cyst of the canal of Nuck shows an inguinal or genital, painless or painful swelling, with no attending nausea or vomiting [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Some existing reports identify that the mass can be reduced manually [8,17,19], and shows no increase in volume when performing the Valsalva maneuver [14,19]. Several authors report an increase in the volume of the swelling when the patient is standing [13,17], while others do not [6]. In general, a differentiation from other entities that cause inguinal or genital swelling based on symptoms and physiological examination is not possible. The most important differential diagnosis of the cyst of the canal of Nuck is the inguinal hernia, with which it is often initially mistaken [9,12,23]. The co-existence of an inguinal hernia is reported in up to 40% of patients with a cyst of the canal of Nuck, making diagnosis even more difficult [16,17,18]. Hydroceles that extend to the vulva may initially be mistaken for Bartholin cysts. [6,7]. Other differential diagnoses for the cyst of the canal of Nuck are lymphadenopathy, cold abscesses, endometriosis of the round ligaments, ganglion cysts, varicosity of the round ligament and other vascular diseases, or neoplasms such as lipomata or leiomyomata [3,10,17,20,21]. An overview of important differential diagnoses of the cyst of the canal of Nuck is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the Cyst of the canal of Nuck and possible differential diagnosis.

Radiological imaging is of utmost importance in distinguishing from the differential diagnoses presented above. For initial imaging of suspect inguinal or genital swellings, sonography is the preferred investigative method. On ultrasound, the cyst of the canal of Nuck appears as a thin-walled anechoic or hypoechoic formation with no changes on Valsalva maneuver and lack of vascular flow on color Doppler [10,15,16,21]. In addition to high-resolution sonography, cross-sectional imaging should be performed to obtain detailed information about the cyst formation. The method of choice should be MRI, which enables a more precise view of anatomical conditions with no radiation compared with the computed tomography (CT). On MRI, the cyst of the canal of Nuck represents as a thin-walled mass, which appears hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted ones [1,16,21,22]. After contrast administration, no enhancing of the cystic mass, which is considered a sign of benignity, can be observed within MRI [17,31,32]. Due to its radiation, CT is only the second-line method, when accessing inguinal or genital swellings, in particular when imaging children. On CT, the cyst of the canal of Nuck appears as a homogeneous fluid-filled unilocular sac extending along the course of the round ligament [13,15,19]. As with MRI, no enhancement of the interior cyst can be identified within CT-imaging after contrast administration [15,33].

4.5. Treatment

Due to the extreme rarity of cysts of Nuck’s canal, no standard therapeutic procedure as yet exists. Although conservative therapy options such as aspiration or sclerotherapy of female hydroceles are reported in the literature, hydrocelectomy is recommended, with or without ligation of the cyst, as treatment of choice [6,7,10,15,19,21,22,56]. Due to anatomical conditions or pathologies such as necrosis of the round ligament, a radical excision of it may be necessary, in addition to hydrocelectomy [9,17,22]. Several authors suggest repairing intraoperative defects by using a polyurethane mesh [5,22,32]. In addition to hydrocelectomy, an aesthetic correction of the vulva may be required as part of the surgery, if the hydrocele has extended to the labia majora [6,7].

Recent therapeutic approaches consider laparoscopic intervention for the treatment of female hydroceles [8,30,57,58]. In particular, the transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and the totally extra-peritoneal (TEP) techniques are considered as popular laparoscopic methods, which can also be used in the treatment of cyst of the canal of Nuck [8,12,30,58]. Laparoscopy can not only be used as a treatment option, but also as an additional diagnostic method to determine the hydrocele and anatomical conditions. Compared with TEP, TAPP has a better diagnostic potential, due to the improved imaging of the abdominal cavity, its anatomical variations and the hydrocele itself [8,12,30,58]. However, sometimes difficult anatomical conditions may prevent a laparoscopic repair, requiring conversion to traditional open anterior surgery [59]. Furthermore, laparoscopic intervention requires a mesh prosthesis to repair the defect within the abdominal wall [8,30,58]. Therefore, the surgical intervention of a cyst of the Nuck’s canal must be well considered and adapted in advance of to the anatomical conditions, as well as the skill of the surgeon.

5. Discussion

A hydrocele in young females is a very uncommon disease, and it occurs even more rarely in adult women. Due to its infrequency, many health professionals are not even aware of its existence. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to raise awareness of clinicians, including surgeons and radiologists on the presence of the canal of Nuck as well as the possibility of a female hydrocele.

The primary symptom of the cyst of the canal of Nuck is a painless or painful swelling in the groin or the labia majora [1,2,7,8,10,11,22]. Initially, in many of the reported cases in the literature, they were wrongly suspected of being an inguinal hernia [9,12,23], which is the most common differential diagnosis of the cyst of the canal of Nuck. Through well-targeted physical examination, followed by high-resolution sonography, a differentiation of a cyst of the canal of Nuck from other entities can easily be performed. With MRI, the anatomical condition can be clarified and the diagnosis of cyst of the canal of Nuck determined. Therefore, in our opinion, an MRI investigation for suspect inguinal or genital swelling should be mandatory.

The treatment of choice is surgical excision of the cyst. Based on our literature research, only a few reports about surgical approaches are available. However, due to the rarity of a Nuck’s canal cyst, there is no defined standard method of intervention to date. In our opinion, the surgical approach should be adapted, based on the type of cyst of the canal of Nuck, the anatomical conditions, and the experience of the responsible surgeon. Although laparoscopic approaches have advantages such as reduced blood loss, less wound drainage, and a better aesthetic outcome, they are associated with higher risk for peri- and postoperative complications such as enterotomy, bowel injury, postoperative bleeding and ileus [60]. Thus, it is of utmost importance to consider the risk-benefit ratio before surgery. Due to the variation of the hydrocele with no connection to the peritoneal cavity, it was decided to perform an open ligation and hydrocelectomy in the present case, followed by repair of the inguinal defect without the use of mesh.

In the available literature, only a few reports of cysts of the canal of Nuck have been published since its discovery [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. However, in recent years, the number of published cases regarding this topic has increased significantly. One possible reason is the improvement in imaging methods, which enables a better overview of this anomaly and its anatomical features.

In conclusion, the cyst of the canal of Nuck in adult women is an extremely rare disease. If one is aware of its existence, it can be easily diagnosed using modern diagnostic methods and treated by adequate surgical approaches. A cyst of the canal of Nuck should always be considered as a possible cause in suspect inguinal and genital swellings in females.

6. Conclusions

Due to the rare clinical occurrence and the lack of literature, a diagnosis of a cyst of the canal of Nuck is often difficult to make, not only for inexperienced surgeons, but also for medical experts. Thus, interdisciplinary collaboration in healthcare between various different fields, such as radiology and surgery, is necessary to prevent misdiagnosis as well as resultant errors in treatment. A focused physical examination followed by high-resolution sonography enables the diagnosis of a cyst of the canal of Nuck. To plan an adequate surgical intervention, cross-sectional imaging, preferably MRI, allowing clarification of the anatomical conditions is of utmost importance. Our review provides insight into the anatomical background, diagnostics, and surgical intervention of a cyst of the canal of Nuck. This article may serve as the foundation for raising awareness about the possibility of female hydroceles and provide guidelines for diagnostic and surgical methods.

Author Contributions

Project administration, conceptualization and methodology, M.K.; Diagnosis and surgical care, J.V.P. and M.K.; Analysis and provision of MRI images, T.M.; Histological evaluation and provision of histological imaging, C.V.; Literature research, M.K.; Visualization of the schematic images, M.K., Writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; Writing—review and editing, J.V.P., C.V., T.M. and R.F.; Supervision, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient who is reported about in this case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

For data requests, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Prodromidou, A.; Paspala, A.; Schizas, D.; Spartalis, E.; Nastos, C.; Machairas, N. Cyst of the canal of Nuck in adult females: A case report and systematic review. Biomed. Rep. 2020, 12, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fikatas, P.; Megas, I.F.; Mantouvalou, K.; Alkatout, I.; Chopra, S.S.; Biebl, M.; Pratschke, J.; Raakow, J. Hydroceles of the canal of nuck in adults—Diagnostic, treatment and results of a rare condition in females. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, H.; King, M.; Rosenberg, H.K.; Rosen, A.; Wilck, E.; Simpson, W.L. Anatomy and pathology of the canal of Nuck. Clin. Imaging 2018, 51, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holley, A. Pathologies of the canal of Nuck. Sonography 2018, 5, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoshi, K.; Mizumoto, M.; Kinoshita, K. Endometriosis-associated hydrocele of the canal of Nuck with immunohistochemical confirmation: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.F.; Marques, J.P.; Falcão, F. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck presenting as a sausage-shaped mass. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017, bcr-2017-221024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Jain, S.; Verma, A.; Jain, M.; Srivastava, A.; Shukla, R.C. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck-Rare differential for vulval swelling. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2014, 24, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Hara, T.; Hirashita, T.; Kubo, N.; Hiroshige, S.; Orita, H. Laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment of a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck extending in the retroperitoneal space: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014, 5, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, I.; İnan, C.; Varol, F.; Erzincan, S.; Sütcü, H.; Sayin, C. Hemorrhagic cyst of the canal of Nuck after vaginal delivery presenting as a painful inguinal mass in the early postpartum period. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 213, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, H.; Stickel, M.D.; Martin Manner, M. Female hydrocele of canal of nuck. J. Ultrasound Med. 2010, 107, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zawaideh, J.P.; Trambaiolo Antonelli, C.; Massarotti, C.; Remorgida, V.; Derchi, L.E. Cyst of Nuck: A Disregarded Pathology. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 376–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunting, D.; Szczebiot, L.; Cota, A. Laparoscopic hernia repair-When is a hernia not a hernia? J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2013, 17, 654–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.S.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, K.P.; Kwon, Y.J.; Hwang, J.H.; Lee, S.Y. Hydrocele of the canal of nuck in a female adult. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2016, 43, 476–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagley, J.E.; Davis, M.B. Cyst of canal of nuck. J. Diagn. Med. Sonogr. 2015, 31, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnam, V.; Narayanan, R.; Kudva, A. A cautionary approach to adult female groin swelling: Hydrocoele of the canal of Nuck with a review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2015212547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozel, A.; Kirdar, O.; Halefoglu, A.M.; Erturk, S.M.; Karpat, Z.; Lo Russo, G.; Maldur, V.; Cantisani, V. Cysts of the canal of Nuck: Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging findings. J. Ultrasound 2009, 12, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caviezel, A.; Montet, X.; Schwartz, J.; Egger, J.F.; Iselin, C.E. Female hydrocele: The cyst of nuck. Urol. Int. 2009, 82, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.D.; Joyce, M.R.; Pierce, C.; Brannigan, A.; O’Connell, P.R. Haematoma in a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck mimicking a Richter’s hernia. Hernia 2009, 13, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, V.; Patel, H. Hydrocele in the canal of nuck—CT appearance of a developmental groin anomaly. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2016, 10, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Bultitude, J.; Diab, J.; Bean, A. Cyst and endometriosis of the canal of Nuck: Rare differentials for a female groin mass. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 2022, rjab626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdale, R.; Agrawal, S.; Chhabra, S.; Jewan, S.Y. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck: Value of radiological diagnosis. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2012, 6, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, R.; Terasaki, H.; Murakami, N.; Tanaka, M.; Takeda, J.; Abe, T. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck: A case report with magnetic resonance hydrography findings. Surg. Case Rep. 2015, 1, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkoyun, I.; Kucukosmanoglu, I.; Yalinkilinc, E. Cyst of the canal of Nuck in pediatric patients. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuck, A. Adenographia curiosa et uteri foeminei anatome nova. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1975, 123, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, W.B., II. Hydrocele in the Female: With a Report of Fourteen Cases. Ann. Surg. 1892, 16, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagur, G.; Gandhi, J.; Suh, Y.; Weissbart, S.; Sheynkin, Y.R.; Smith, N.L.; Joshi, G.; Khan, S.A. Classifying Hydroceles of the Pelvis and Groin: An Overview of Etiology, Secondary Complications, Evaluation, and Management. Curr. Urol. 2017, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papparella, A.; Vaccaro, S.; Accardo, M.; DE Rosa, L.; Ronchi, A.; Noviello, C. Nuck cyst: A rare cause of inguinal swelling in infancy. Minerva Pediatr. 2021, 73, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.S.; Luo, C.C.; Chao, H.C.; Chu, S.M.; Yu, Y.J.; Yen, J.B. The presentation of asymptomatic palpable movable mass in female inguinal hernia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003, 162, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counseller, V.S.; Black, B.M. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck. Report of seventeen cases. Ann. Surg. 1941, 113, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Maejima, T.; Fukahori, S.; Shun, K.; Yoshikawa, D.; Kono, T. Laparoscopic surgical treatment for hydrocele of canal of Nuck: A case report and literature review. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manenti, G.; D’Amato, D.; Ranalli, T.; Marsico, S.; Castellani, F.; Salimei, F.; Floris, R. Cyst of canal of Nuck in a young woman affected by kniest syndrome: Ultrasound and MRI features. Radiol. Case Rep. 2019, 14, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topal, U.; Sarıtaş, A.G.; Ülkü, A.; Akçam, A.T.; Doran, F. Cyst of the canal of Nuck mimicking inguinal hernia. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 52, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.; Helmy, A.H. Rare encounter: Hydrocoele of canal of Nuck in a Scottish rural hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamadar, D.A.; Jacobson, J.A.; Morag, Y.; Girish, G.; Ebrahim, F.; Gest, T.; Franz, M. Sonography of inguinal region hernias. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006, 187, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakil, A.; Aparicio, K.; Barta, E.; Munez, K. Inguinal Hernias: Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, J. Inguinal Hernias: MRI and Ultrasound. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2002, 23, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.P.; Smietanski, M.; Bonjer, H.J.; Bittner, R.; Miserez, M.; Aufenacker, T.J.; Fitzgibbons, R.J.; Chowbey, P.K.; Tran, H.M.; Sani, R.; et al. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 2018, 22, 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, S.; Shojaiefard, A.; Khorgami, Z.; Alinejad, S.; Ghorbani, A.; Ghafouri, A. Peripheral lymphadenopathy: Approach and diagnostic tools. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 39, 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, M.; Aquino, S.L.; Harisinghani, M.G. Current Concepts in Lymph Node Imaging Continuing Education. J. Nucl. Med. 2004, 45, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Eppel, W.; Worda, C. Ultrasound Imaging of Bartholin’ s Cysts. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2000, 49, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Balogun, M.; Ganesan, R.; Olliff, J.F. MRI of vaginal conditions. Clin. Radiol. 2005, 60, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.Y.; Dalpiaz, A.; Schwamb, R.; Miao, Y.; Waltzer, W.; Khan, A. Clinical pathology of Bartholin’s glands: A review of the literature. Curr. Urol. 2014, 8, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licheri, S.; Pisano, G.; Erdas, E.; Ledda, S.; Casu, B.; Cherchi, M.V.; Pomata, M.; Daniele, G.M. Endometriosis of the round ligament: Description of a clinical case and review of the literature. Hernia 2005, 9, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, B.; Valentini, A.L.; Ninivaggi, V.; Marino, M.; Iacobucci, M.; Bonomo, L. Deep pelvic endometriosis: Don’t forget round ligaments. Review of anatomy, clinical characteristics, and MR imaging features. Abdom. Imaging 2014, 39, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukata, K.; Nakai, S.; Goto, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Shimaoka, Y.; Yamanaka, I.; Sairyo, K.; Hamawaki, J.I.J. Cystic lesion around the hip joint. World J. Orthop. 2015, 6, 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, A.; Zanotti, G.; Berizzi, A.; Staffa, G.; Piccinini, E.; Ruggieri, P. Synovial cysts of the hip. Acta Biomed. 2017, 88, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.N.; Ha, A.S.; Chen, E.; Davidson, D. Lipomatous soft-tissue tumors. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2018, 26, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasih, N.; Prasad Shanbhogue, A.K.; Macdonald, D.B.; Fraser-Hill, M.A.; Papadatos, D.; Kielar, A.Z.; Doherty, G.P.; Walsh, C.; McInnes, M.; Atri, M. Leiomyomas beyond the uterus: Unusual locations, rare manifestations. Radiographics 2008, 2, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zou, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Han, L.; Batchu, N.; Ulain, Q.; Du, J.; Lv, S.; Song, Q.; et al. Review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapy of vulvar leiomyoma, a rare gynecological tumor. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, A.; Wozniak, S. Ultrasonography of uterine leiomyomas. Menopause Rev. 2017, 16, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, Y.; Eguchi, S.; Enjouji, A.; Fukuda, M.; Yamaguchi, J.; Inoue, Y.; Fujita, F.; Tsukamoto, O.; Masuzaki, H. Round ligament varicosities diagnosed as inguinal hernia during pregnancy: A case report and series from two regional hospitals in Japan. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 36, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.S.; Balasubramanian, P. Round ligament varices mimicking inguinal hernia during pregnancy. Radiol. Case Rep. 2019, 14, 1036–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, K.H.; Yoon, J.H. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of round ligament varicosities mimicking inguinal hernia: Report of two cases with literature review. Ultrasonography 2014, 33, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokue, H.; Aoki, J.; Tsushima, Y.; Endo, K. Characteristic of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging finding of thrombosed varices of the round ligament of the uterus: A case report. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2008, 32, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.; Wong, G.T. Round ligament varicosity thrombosis presenting as an irreducible inguinal mass in a postpartum woman. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2019, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornacchia, C.; Dessalvi, S.; Boccardo, F. Surgical treatment of cyst of the canal of nuck and prevention of lymphatic complications: A single-center experience. Lymphology 2019, 52, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, N.J.; Lakshman, K. Laparoscopic excision of cyst of canal of Nuck. J. Minim. Access Surg. 2014, 10, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, F.; El Ansari, W.; Ben-Gashir, M.; Abdelaal, A. Laparoscopic hydrocelectomy of the canal of Nuck in adult female: Case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 66, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Maejima, T.; Fukahori, S.; Shun, K.; Yoshikawa, D.; Kono, T. Laparoscopic assisted hydrocelectomy of the canal of Nuck: A case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, H.H.; Hansson, B.M.E.; Buunen, M.; Janssen, I.M.C.; Pierik, R.E.G.J.M.; Hop, W.C.; Bonjer, H.J.; Jeekel, J.; Lange, J.F. Laparoscopic vs Open Incisional Hernia Repair. JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).