Abstract

(1) Background: Halitosis is a frequent condition that affects a large part of the population. It is considered a “social stigma”, as it can determine a number of psychological and relationship consequences that affect people’s lives. The purpose of this review is to examine the role of psychological factors in the condition of self-perceived halitosis in adolescent subjects and adulthood. (2) Type of studies reviewed: We conducted, by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, systematic research of the literature on PubMed and Scholar. The key terms used were halitosis, halitosis self-perception, psychological factors, breath odor and two terms related to socio-relational consequences (“Halitosis and Social Relationship” OR “Social Issue of Halitosis”). Initial research identified 3008 articles. As a result of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the number of publications was reduced to 38. (3) Results: According to the literature examined, halitosis is a condition that is rarely self-perceived. In general, women have a greater ability to recognize it than men. Several factors can affect the perception of the dental condition, such as socioeconomic status, emotional state and body image. (4) Conclusion and practical implication: Self-perceived halitosis could have a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life. Among the most frequent consequences are found anxiety, reduced levels of self-esteem, misinterpretation of other people’s attitudes and embarrassment and relational discomfort that often result in social isolation.

1. Introduction

Halitosis, commonly called bad breath, is a problem that can affect both the external, relational, social communication and internal, psychological sphere, with implications on perceived quality of life [1]. People are usually unaware of their breath, and when they become aware of it, they incorrectly attribute the cause of their condition. Halitosis is a frequent condition, present in 50–65% of the world population [2]. Although it is a significant source of discomfort, a precise estimation of prevalence is not possible because epidemiological studies are limited. This limitation could be determined by several factors, such as the absence of a standardized method for assessment of the disease, the difficulty in recognizing its presence and the likelihood that it is in some cases transient, which is why it is underreported in epidemiological data [3]. The problem of people with halitosis is that this condition can often remain unnoticed because people are generally unaware of the quality of their oral odor. Research conducted on Korean adolescent subjects [4] has made it possible to identify a considerable number of adolescents between 12 and 18 years of age with halitosis, highlighting the contributing factors at this age such as substance abuse and smoking, diet and economic social status. Regarding gender, there appears to be no correlation whatsoever [5,6]. The term physiological or transient halitosis refers to dental bad smell, which occurs only at certain times of the day, for example during the early morning hours. Occurring in the absence of a specific dental pathology, it can be associated with factors such as diet and tobacco use [3]; psychiatric illnesses, anxiety, depression and stress are also among the causes of halitosis [4,5,6,7]. Halitophobia or pseudohalitosis refers to the fear of suffering from bad breath. In such subjects, treatments aimed at resolving the bad smell would be useless, and evaluation and intervention of a psychologist [8] are considered appropriate. Pathological halitosis is divided by some authors into intraoral (90%) and extraoral (10%) halitosis [1]. The back of the tongue is a potential reservoir of bacteria and source of foul-smelling gases; therefore, daily washing should be performed to reduce the number of bacteria and the processes leading to the manifestation of foul smells [9,10,11,12]. Extraoral factors not related to the oral cavity include intake of maltogenic foods (such as garlic, onions, fatty foods, sugars and sweets, which can promote the development of caries and the production of substances with an unpleasant smell), smoking and alcohol, coffee abuse, metabolic disorders (such as liver failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, cirrhosis, renal failure, hiatal hernia), upper respiratory tract disorders (chronic sinusitis, nasal obstruction, nasopharyngeal abscess) and lower respiratory tract disorders (i.e., bronchitis, pulmonary abscess, lung cancer) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Studies in the literature allow us to identify how halitosis has a significant impact on the life of the individual. Among the first consequences, it can cause embarrassment and depression [14,15]. In adolescence, it is a significant condition that compromises social development [16]. Considered by Kolo [5] as a “social stigma”, it could become an obsession that dominates a person’s life, determining the onset of factors such as anxiety and psychosocial stress. The hypochondria of some individuals can, in certain cases, determine the onset of what is called “delusional halitosis”, caused by an incorrect assessment of their olfactory perceptions. The first factor to be compressed in subjects with halitosis is the communicative act with consequent impairment of professional interactions [17]. This could negatively affect self-esteem and confidence, reducing quality of life to the point of complete isolation [18]. Awareness of halitosis leads the individual to experience the condition negatively so that it leads to halitophobia, a term used to indicate a condition characterized by excessive concern with the belief of having halitosis [19]. One theme of studies on self-perceived halitosis shows that the problem is often not self-perceived [20,21]. Self-reported halitosis tends to be underestimated mainly because individuals may have difficulty in detecting their own smell or feel embarrassed to expose themselves, in line with the intimate dimension of the relationship with their mouth [22]. Subjects with a good body image pay more attention to their mouth and oral malodor [23]. Moreover, emotional state can also have a negative impact in neglect of investment in one’s own body, also in terms of care and hygiene, and the subject could become more sensitive to bad smell, highlighting a multifactorial psychophysiological problem [24]. In this regard, individuals with psychiatric illnesses, including those with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder, may have impaired oral health [25]. For example, the presence of depressive disorder may adversely affect the patient’s hygiene activities and personal care. Depression is a frequent and debilitating disorder characterized by loss of energy, anhedonia, reduced libido and feelings of sadness and despair that interfere with the daily activities of individuals. Such problems will lead to a reduction in the patient’s self-esteem, leading to negative effects on the treatment of mental illness [26]. Moreover, each patient has a specific and different image of “breath smell”: some subjects experience halitosis but the bad smell is neither offensive nor evident, and many authors, to highlight this condition, speak of “halitosis paradox”; i.e., while many develop wrong perceptions about their bad breath, others are not aware [23]. People who have a bad oral odor problem tend not to be aware of their bad breath, while those who do not have a bad breath problem worry excessively about having a bad odor problem. Young and middle-aged people tend to be more alert and anxious about their health, obtaining significantly higher scores in the OLT (organoleptic test, the gold standard to detect bad oral smell) and showing significant symptoms of anxiety and depression, with the anxiety itself increasing oral levels of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. A gender difference in the perception of halitosis was highlighted in one study [23]: 21.7% were male and 35.3% were female. Ashwath et al. [23] stated that self-perceived halitosis was more present in dental students. In addition, other significant relationships are found between self-perceived halitosis and other variables, including paternal and maternal education (illiteracy scores high compared to fathers and mothers with a diploma or university degree), dental brushing (the highest scores were related to an absence of brushing, compared to those who practiced oral hygiene three times a day) and the use of dental floss and mouthwash. Recent studies have suggested that socioeconomic inequality may affect halitosis awareness [28] and that halitosis reporters tend to have difficulty contacting the dentist [29]. A further factor to consider is the relationship between smoking and halitosis awareness: 2% of females and 14% of males report smoking, and this has been found to be significantly associated with self-perception. Gender differences in tobacco use have been attributed to cultural issues [30]. Recent studies confirm that self-perception of halitosis may be related to a psychogenic or psychosomatic disorder and has a strong psychological impact [31,32].

2. Materials and Methods

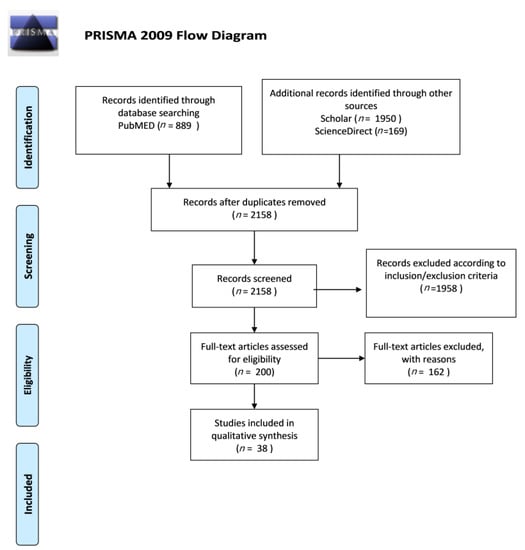

A review strategy has been conducted to summarize the available results of experimental studies. This review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [33] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow Diagram.

2.1. Criteria for Eligibility and Research Strategy

To identify the studies, we performed a systematic literature search on the PubMed, Scholar and ScienceDirect databases. The search was limited to studies written in English. We identified the literature from January 2010 to January 2020 using four key terms related to self-perceived halitosis, namely halitosis, self-perception halitosis, psychological factors and breath odor, and two terms related to sociorelational consequences (“Halitosis and Social Relationship” OR “ Social Issue of Halitosis”). The articles of 1994 and 2001 were only cited to introduce the body image theory and to link it to the perception that each individual has of his or her own smell. The electronic research strategy used is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of search terms entered into the PubMed, Scholar and ScienceDirect search.

Articles were selected online in relation to the title and abstracts; articles were read in full when titles and abstracts were consistent with the objective of our study. Following this procedure, we found 889 articles on the PubMed database, 1950 articles on Scholar and 169 articles on ScienceDirect; after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the total number of relevant publications was reduced to 38.

2.2. Study Selection

The articles were included in the review according to the following inclusion criteria: English language, publication in peer-reviewed scientific journals and quantitative information about self-perceived halitosis and oral hygiene. Articles were excluded based on title and abstract screen; review articles, editorial comments and case reports were also excluded. The quality of included studies was appraised by separate methods for qualitative and quantitative studies; features of study design, methodology and analysis were assessed. Qualitative studies were appraised using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool (CASP), while the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) tool was used for quantitative studies. The search in the PubMed, Scholar and ScienceDirect databases provided a total of 3008 articles; no further studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified. After eliminating duplicates, further studies were excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After screening, 38 studies were selected as appropriate for the present review.

2.3. Bias Risk among Studies

In all studies included in this review, a potential bias of the database should be considered. Only articles in English have been used, which could have compromised access to articles published in other languages.

3. Results

According to the literature examined, halitosis is a condition that is rarely self-perceived. In particular, 10 articles focus on the self-perception of halitosis, 10 deal with halitosis by defining it and analyzing the epidemiology, 1 study focuses on body image related to the perception of one’s smell, 7 studies analyze the different psychological factors related to halitosis and 10 studies address the sociorelational problems caused by halitosis. Quality assessment of the selected works was performed using CASP and EPHPP tools; the results of quality assessment are reported in Table 2 and Table 3. Most of the qualitative studies were found to have good quality, while some of the quantitative works showed relevant methodological weaknesses such as selection bias, unsatisfactory design and presence of confounders. Despite these limitations, studies made it possible to understand the importance of this condition and the influence it exerts on the psychorelational status of affected subjects. A summary of the selected studies is reported in Table 4. Additionally, references to the selected articles were examined in order to identify further studies that could meet inclusion criteria (Table 5). Studies found that the prevalence of self-perceived halitosis was 22.8% among the participants. The majority of subjects with self-perceived halitosis experienced bad breath on awakening (83.5%). Self-perceived halitosis was more prevalent among males than females, whereas no statistically significant differences were found between age groups. A statistically significant relationship was found between self-perceived halitosis and mouth cleaning time, and a statistically significant relationship was found between self-perceived halitosis and mouth cleaning time, shisha use or cigarette smoking [16]. In this study, it was found that the more people perceived their oral odor, the more likely they were to maintain a distance. A subgroup of individuals was identified who reported maintaining a certain distance when meeting other people, despite a self-perceived “fresh” oral odor. Self-perceived halitosis leads people to keep their distance in social interactions. The ability to recognize and perceive one’s oral condition can be influenced by socioeconomic variables such as age, gender and level of education [31]. There are frequent cases of oral and dental problems in patients with depression, anxiety or schizophrenia [26]. It has been possible to understand how people have difficulty recognizing the presence of halitosis and have limited knowledge about this condition [11]. It is clear that halitosis is an unpleasant symptom and can create relational difficulties with consequences for the individual’s quality of life [3]. The participants in the study were healthy subjects. Participants in some studies underwent organoleptic tests to measure breathing odor and specific questionnaires were given. Some patients with halitosis were compared with healthy subjects.

Table 2.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP).

Table 3.

Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP).

Table 4.

Characteristics of the studies.

Table 5.

Prisma Checklist.

This study has identified the importance of the consequences that the perception of bad breath has on the psychorelational side and, in general, on patients’ quality of life.

4. Discussion

The studies analyzed focus on the importance of self-perception of halitosis and the consequences it has on the life of the individual. It is an oral health problem that could be prevented through appropriate oral hygiene practices and to which attention should be paid, given the influence it has on patients’ quality of life. The subject’s awareness of his or her condition leads to such anxiety that he or she obsessively uses appropriate instruments to eclipse the bad smell, such as sprays, chewing gum, pills or mouthwashes [38]. Although it is a significant condition for the individual, it is not easy to recognize or “self-perceive” it. A study conducted in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom [34] showed that 51.9% of the Saudi population and 54.9% of the UK population were aware of their halitosis. In contrast, a study conducted on the population of the Netherlands shows that only 4.2% were able to recognize their bad smell [35]. In individuals with halitosis, certain consequences have a significant impact on the individual. The reduction in self-confidence and self-esteem levels and the onset of depression and stress are the main consequences that can be observed in patients with this condition. The onset of social anxiety is also important, as it could lead the individual to estrangement and avoidance of social interactions. In a study [37], it has been shown that people with halitosis had relationship failures, in particular with individuals of the opposite gender; showed difficulties in achieving their goals; and exhibited compromised performance even in the workplace, considering this condition a “social handicap”. The research obtained also allows us to affirm that, although halitosis causes considerable problems in the subject, it is often not treated but ignored or denied. Patients are not very optimistic about treatment. In the literature, it emerges that the self-perception of halitosis could determine the onset of symptoms such as anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorders and paranoid ideation, and very often subjects misinterpret the attitude of people who relate to them. There is a need to introduce, together with the professional doctor, the intervention of specialists such as psychologists and psychiatrists to prevent consequences [17,36]. We believe that it is useful to work in a multidisciplinary mode in which one can intervene on both the oral condition and the psychological conditions of the patient to alter inadequate attitudes and wrong beliefs and to encourage the adoption of behaviors that can reduce the bad smell and improve patients’ quality of life.

Limitations

This study suffers from several limitations: indeed, due to the relatively low number of studies on the topic and their great methodological heterogeneity, a proper formal quality assessment of each work was precluded. Therefore, selection bias was not properly addressed, which can impact the general interpretability of results. In general, care is required when interpreting the results of the cited studies, and further investigations are needed to clarify the relationship between self-perceived and objective halitosis.

5. Conclusions

This study has identified the importance of the consequences that the perception of bad breath has on the psychorelational side and, in general, on patients’ quality of life. Literature studies have shown that women have, as a percentage, a greater awareness of their dental condition than men. Socioeconomic status is one of the factors that can influence self-perceived halitosis. Research has also led to an understanding of how body image and emotional state may be a variable that can influence perception. Oral hygiene measures can significantly reduce the bad smell. Oral health education must also be provided in many places, including private dental and medical clinics, and it is important that healthcare professionals, including general practitioners and health professionals, understand the etiology and critical factors in order to diagnose and treat patients appropriately. This review has reviewed the studies in the literature. The limitation of our study concerns the exclusive treatment of psychological factors implicated in halitosis at the expense of possible treatments.

Author Contributions

C.M., A.B., M.R.A.M. and R.A.Z. contributed to conception; design; and data acquisition, analysis and interpretation and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. C.L. contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation and drafted the manuscript. M.M. contributed to data acquisition and drafted the manuscript. M.B.-C., P.J.A.-P. and C.S.F. contributed to conception and critically revised the manuscript. N.I.W. contributed to interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no financial support and declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Kuzhalvaimozhi, P.; Krishnan, M. Self-Perception, Knowledge and Attitude of Halitosis among patients attending a Dental Hospital in South India-A Questionnaire Based Study. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2019, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemel-Suárez, M.; Chimenos-Küstner, E.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Jané-Salas, E.; López-López, J. Halitosis Assessment and Changes in Volatile Sulfur Compounds after Chewing Gum: A Study Performed on Dentistry Students. J. Évid. Based Dent. Pr. 2017, 17, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoppay, J.; Filippi, A.; Ciarrocca, K.; Greenman, J.; De Rossi, S. Halitosis. In Contemporary Oral Medicine; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Sim, S.; Kim, S.-G.; Park, B.; Choi, H.G. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Subjective Halitosis in Korean Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idemudia, A.; Ahmed, A.; Alufohai, O.; Kolo, E. Psychosocial problems in adults with halitosis. J. Med. Trop. 2015, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settineri, S.; Rizzo, A.; Ottanà, A.; Liotta, M.; Mento, C. Dental aesthetics perception and eating behavior in adolescence. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2015, 27, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mento, C.; Gitto, L.; Liotta, M.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Bruno, A.; Settineri, S. Dental anxiety in relation to aggressive characteristics of patients. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2014, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhushankari, G.; Yamunadevi, A.; Selvamani, M.; Kumar, K.M.; Basandi, P.S. Halitosis–An overview: Part-I–Classification, etiology, and pathophysiology of halito-sis. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2015, 7 (Suppl. 2), S339. [Google Scholar]

- Azodo, C. Social trait rating of halitosis sufferers: A Crosssectional study. J. Dent. Res. Rev. 2019, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settineri, S.; Mucciardi, M.; Leonardi, V.; Mallamace, D.; Mento, C. The emotion of disgust in Italian students: A measure of the synthetic disgust index. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2013, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Mubayrik, A.; Al-Hamdan, R.; Al Hadlaq, E.M.; AlBagieh, H.; AlAhmed, D.; Jaddoh, H.; Demyati, M.; Abu Shryei, R. Self-perception, knowledge, and awareness of halitosis among female university students. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2017, 9, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, U.; Sharma, G.; Juneja, M.; Nagpal, A. Halitosis: Current concepts on etiology, diagnosis and management. Eur. J. Dent. 2016, 10, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özen, M.E.; Aydin, M. Subjective Halitosis: Definition and Classification. J. N. J. Dent. Assoc. 2015, 86, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Azodo, C.; Umoh, A. Relational impact of halitosis: A study of young adult Nigerians. Savannah J. Med Res. Pr. 2018, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colussi, P.R.G.; Hugo, F.N.; Muniz, F.W.M.G.; Rösing, C.K. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Associated Factors in Brazilian Adolescents. Braz. Dent. J. 2017, 28, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsadhan, S.A. Self-perceived halitosis and related factors among adults residing in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A cross sectional study. Saudi Dent. J. 2016, 28, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heboyan, A.; Avetisyan, A.; Vardanyan, A. Halitosis as an issue of social and psychological significance. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2019, 7, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mrizak, J.; Ouali, U.; Arous, A.; Jouini, L.; Zaouche, R.; Rebaï, A.; Zalila, H. Successful Treatment of Halitophobia with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy: A Case Study. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2018, 49, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Conceicao, M.D.; Giudice, F.S.; de Francisco Carvalho, L. The Halitosis Consequences Inventory: Psychometric properties and relationship with social anxiety dis-order. BDJ Open 2018, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dico, G.L. Self-Perception Theory, Radical Behaviourism, and the Publicity/Privacy Issue. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2017, 9, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.D. What is body image? Behav. Res. Ther. 1994, 32, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eli, I.; Baht, R.; Koriat, H.; Rosenberg, M. Self-perception of breath odor. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2001, 132, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwath, B.; Vijayalakshmi, R.; Malini, S. Self-perceived halitosis and oral hygiene habits among undergraduate dental students. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settineri, S.; Rizzo, A.; Liotta, M.; Mento, C. Clinical Psychology of Oral Health: The Link Between Teeth and Emotions. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 2158244017728319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S. No Mental Health without Oral Health. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torales, J.; Barrios, I.; González, I.; Barrios, I. Gonz Oral and dental health issues in people with mental disorders. Medwave 2017, 17, e7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedapo, A.H.; Kolude, B.; Dada-Adegbola, H.O.; Lawoyin, J.O.; Adeola, H.A. Targeted polymerase chain reaction-based expression of putative halitogenic bacteria and volatile sulphur compound analysis among halitosis patients at a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Odontology 2019, 108, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, N.; Hosseinpour, S.; Nazari, H.; Rezaei, M.; Rezaei, K. Halitosis And Its Associated Factors Among Kermanshah High School Students (2015). Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2019, 11, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Chaudhary, G.; Kalsi, D.; Bansal, S.; Mahajan, D. Knowledge and attitude of indian population toward “self-perceived halitosis”. Indian J. Dent. Sci. 2017, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almas, K.; Smith, S.; Siddiqui, I.; Albaqawi, H.; Almutair, A.; Alzaghran, S.; Almuhanna, L.; Alhumaidan, A.; Alharbi, R. Self-perceived oral malodor, smoking and oral hygiene practices among dental students in the eastern province of saudi arabia. Pak. Oral Dent. J. 2018, 38, 486. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, S.F.S.; Costa, F.O.; Silveira, J.O.; Cyrino, R.M.; Cota, L.O.M. Self-reported halitosis in a sample of Brazilians: Prevalence, associated risk predictors and accu-racy estimates with clinical diagnosis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settineri, S.; Mento, C.; Gugliotta, S.C.; Saitta, A.; Terranova, A.; Trimarchi, G.; Mallamace, D. Self-reported halitosis and emotional state: Impact on oral conditions and treatments. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.Y.S.; Alayyash, A.A. Social stigma related to halitosis in Saudi and British population: A comparative study. J. Dent. Res. Rev. 2016, 3, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jongh, A.; van Wijk, A.J.; Horstman, M.; de Baat, C. Self-perceived halitosis influences social interactions. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deolia, S.; Ali, M.; Bhatia, S.; Sen, S. Psychosocial effects of halitosis among young adults. Ann. Indian Psychiatry 2018, 2, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Kulkarni, S.; Doshi, D.; Reddy, P.; Reddy, S.; Srilatha, A. Association Between Social Anxiety with Oral Hygiene Status and Tongue Coating among Patients with Subjective Halitosis. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 91, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Umeizudike, K.A.; Oyetola, O.E.; Ayanbadejo, P.O.; Alade, G.O.; Ameh, P.O. Prevalence of self-reported halitosis and associated factors among dental patients at-tending a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Sahel Med. J. 2016, 19, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).