Abstract

Background and objectives: Health care organizations continue to respond to the COVID-19 global pandemic and an ongoing array of related mental health concerns. These pandemic-related challenges continue to be experienced by both the U.S. population and those abroad. Materials and methods: This systematic review queried three research databases to identify applicable studies related to protective and non-protective factors of mental health distress experienced during the pandemic within the United States. Results: Three primary factors were identified as protective factors, potentially helping to moderate the incidence of mental distress during the pandemic: demographics, personal support/self-care resources, and income/financial concerns. Researchers also identified these same three constructs of non-protective factors of mental health distress, as well as two additional variables: health/social status and general knowledge/government mistrust. Conclusions: This systematic review has identified protective and non-protective factors of mental health distress experienced in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic (to date) that can further assist medical providers in the U.S. and beyond as the pandemic and related mental health concerns continue at a global level.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic is not only a global entity, but is also an equal opportunity pathogen. The physiologic and physical symptoms incurred by virus victims have a wide spectral berth, from asymptomatic to fatal. The rapid onset and dissemination of “the virus” to global proportions took the world’s population by surprise in early 2020. While the global medical community raced for treatment and prevention, the virus was also claiming a sinister impact on mental health, especially in the United States. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in June of 2020 (just a few months after the pandemic onset) “40% of US adults reported struggling with mental health or substance abuse”; a three-fold increase compared to 2019 data. Symptoms of mental health concerns included depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, stress-related disorder, and substance abuse [1]. Although, an increase in mental health issues occurred, the literature reveals that different population characteristics may have proven to be protective or non-protective. Thus, this review focuses on identifying those key factors categorically.

1.2. Objectives

The research team’s overall intent was to investigate underlying themes (constructs) surrounding influences upon the U.S. population’s mental health distress as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic to date. Both protective and non-protective (facilitator and barrier) constructs were investigated to identify factors contributing to and assisting with guarding against mental health distress and related mental illnesses. The research team’s focus was to evaluate such observations in the literature, code/classify both protective and non-protective factors having an influence on the mental health distress independent variable, and to disseminate research findings to further assist with mental health care and resources provided in an ongoing manner during the pandemic.

The research team hypothesized potential protective factors as experienced themselves throughout the pandemic while living in the U.S., as well as non-protective factors in this regard. These experiences and initial queries into the literature became the impetus for the study, while no pre-identification of any specific protective and/or non-protective mental health/distress constructs were delineated to preserve the integrity of the review. The team also recognized that the duration of the pandemic with additional COVID-19 variants could potentially influence construct identification during limited time periods within the past 1.5 years. Public health policies at local, state, and national levels, as well as economic changes throughout the review period could also affect protective and non-protective factors of mental health distress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

To be included in the review, studies had to be focused on mental health distress and/or illness and be specifically related and/or occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, articles had to be published between 1 March 2020 through 25 May 2021; however, a 2022 search end date was available and utilized by the Elton B. Stephens company (EBSCO) search engine to ensure that all most-recent publications were included in the search at the time of database query. Articles had to be published in quality peer-reviewed and/or academic journals, written in English, and identified with U.S. geographic indicator by EBSCO. While some articles identified included an evaluation of patient outcomes with regard to mental health distress treatment and follow-up care provisions, this was not a required criterion to be included in the review.

2.2. Information Sources

The review queried three academic research databases: Academic Search Complete, Complementary Index, and MEDLINE Complete. These three databases were chosen for the review because they yielded the highest frequency of results upon controlling for potential duplicates, as identified by the EBSCO search engine. The search was conducted from May 10, 2021 through May 25, 2021.

2.3. Search

Databases selected for the review focused on those that yielded the highest initial search results. The research team developed an aggressive search string with Boolean operators that identified the highest initial database results for the study topic. The National Library of Medicine’s controlled vocabulary thesaurus—Medical Subject Headings (or MeSH)—was used to identify key terms for each of the search variables. After multiple iterations of search queries with various Boolean operators, a final review sample was identified. The final search string identified by the researchers was: (“mental health service*” OR “mental hygiene service*” OR “mental health” OR mental hygiene”) AND (“COVID-19” OR “coronavirus” OR “2019-ncov”) AND (“telemedicine” OR “telehealth” OR “telecare” OR “telecommunication” OR “online” OR “virtual”) AND (“assessment tools” OR “assessment method” OR “assessing”).

The search criteria included an aggressive article publication date range in order to specifically identify mental health assessments conducted using telehealth resources during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Additional search criteria included English-only, peer-reviewed and/or academic journals only, and U.S. geographic location only. These exclusion criteria were executed by using the EBSCO research database filtering criteria options and were then later verified during the full-article review process. While the research team acknowledges the importance of a global perspective on the implementation of telehealth during the pandemic, this review initiative was intended to specifically investigate inherent, U.S.-specific characteristics of mental health assessments conducted via telehealth during the global pandemic.

2.4. Initial Study Selection

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guided this review initiative, and the review was registered on PROSPERO. All researchers participated in the initial database search, which included any/all articles identified by the initial search criteria. The research team are all from various research/academic institutions, and, therefore, the use of full-text as a search criteria was not utilized in the initial database search. Therefore, a maximum number of initial articles was identified by the research team. Capitalizing on each research team members’ home institution (university) research database access privileges, the full text of all identified articles was able to be accessed using a collective process.

A MS Excel spreadsheet was used to document the review team’s efforts in reviewing the literature, division of work, identifying and recording identified themes in the sample, and related sub-theme affinity commentary between team members. Multiple methods were utilized in this initial review, including abstract screening, full text article review, and also review of the initial sample articles’ literature cited/reference sections. The team conducted multiple webinar sessions to collaborate on the literature review matrix findings, and no content and/or underlying theme disagreements were experienced at this stage of the review.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection/Exclusion

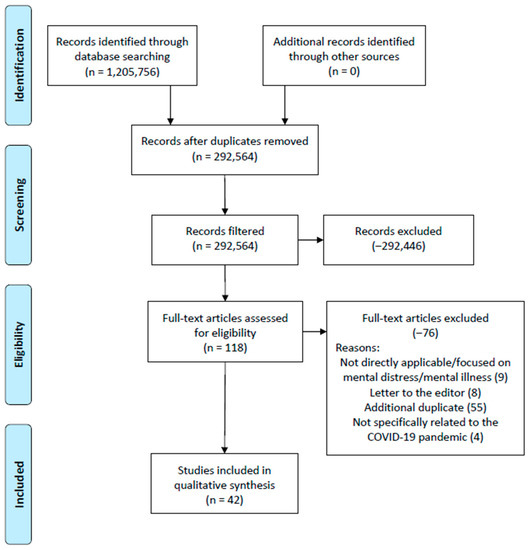

The study selection and subsequent article exclusion process is shown in Figure 1. While over 1.2 million articles were initially identified in the initial database search using the search string developed using MeSH key terms, the exclusion process removed a significant amount of duplicates identified between the three research databases. The initial identification of records identified in the three research databases are as follows:

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) figure that demonstrates the PRISMA-guided study selection process.

- Academic Search Complete: 468,278;

- Complementary Index: 429,021;

- MEDLINE Complete: 308,457.

A full-text review of the 118 articles identified upon completion of database screening by the research team resulted in an additional 76 articles being excluded from the review. These articles were removed from the review for the following reasons:

- Primary focus of mental distress and/or mental health was not observed;

- Letters to the editor;

- Additional duplicates;

- The article was not directly related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research team conducted article reviews using the article assignment shown in Table 1. Each article was analyzed by at least two of the research team members (or more) and consensus meetings were held via online webinar. A MS Excel spreadsheet was kept to gather all observations by the research team and ultimately develop underlying constructors (facilitators and barriers) regarding the research topic. The team experienced no differences of opinion or any other dissent toward both any article and the underlying concept(s) identified in the final review articles.

Table 1.

Reviewer assignment of the initial database search findings (full article review).

3.2. Study Characteristics

A systematic approach was employed in reviewing articles to determine the protective and non-protective factors of mental health distress in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice (JHNEBP) study design analysis, both protective and non-protective factors of mental distress during the pandemic are summarized in Table 2. Articles are listed in alphabetical order by the first author’s last name.

Table 2.

Summary of findings (n = 42).

3.3. Risk of Bias

The research team utilized the JHNEBP quality indicator frequencies to assess the strength of evidence of all articles included in the review. These frequencies are shown in Table 3. As with any review, a higher frequency in levels I and/or II categories is preferred, although, often, this is not always a possibility based upon the review topic and other related variables included in the search. Based upon this review’s initiative to investigate those studies surrounding protective and non-protective factors of mental health distress within a specific timeframe (COVID-19 pandemic), and also based within the unique U.S. healthcare system, articles with JHNEBP quality indictor levels I through IV were identified by the review team. Level V articles were not permitted in the study primarily due to the opinion and/or letter to the editor status (addressed in Figure 1).

Table 3.

Summary of quality assessments.

This review served as a convenience sample in an attempt to assess mental health protective and non-protective factors of mental health distress within the unique U.S. healthcare system. As a result, the study does not review identified constructs beyond the U.S., and results beyond this one country are limited with regard to external validity (to some extent).

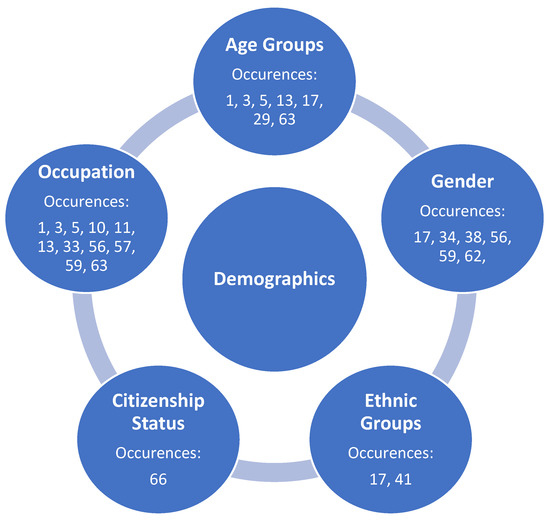

3.4. Additional Analysis

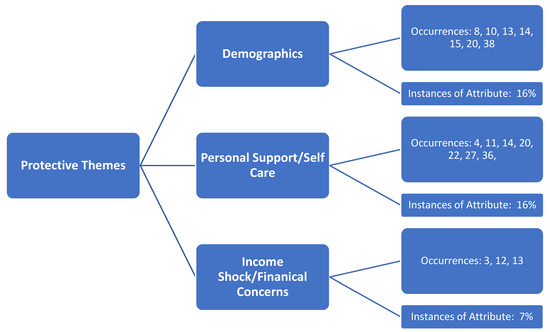

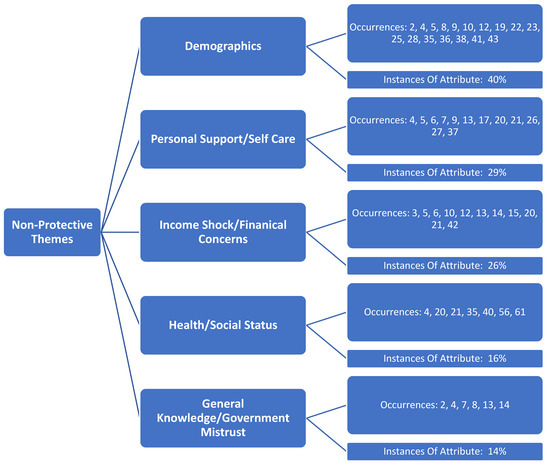

Identified underlying themes (constructs) by the review team are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Three protective factors were identified (Figure 2), and these same three constructs were also considered as non-protective factors, along with two additional non-protective constructs (Figure 3). The review team concluded that the three matching constructs among both protective and non-protective mental health distress observed in the literature were not easily related and/or had a dichotomous relationship and, therefore, were to be presented separately as protective and non-protective factors. Further, findings in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 are not mutually exclusive to either theme, and, as a result, several articles demonstrate more than one construct upon review.

Figure 2.

Identified themes (constructs) identified as protective factors of mental health distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

Figure 3.

Identified themes (constructs) identified non-protective factors of mental health distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

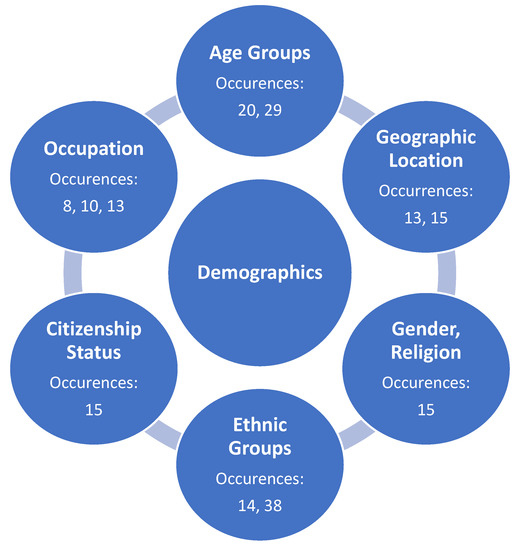

Figure 4.

Identified sub-themes (underlying sub-constructs) identified protective demographic factors of mental health distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

Figure 5.

Identified sub-themes (underlying sub-constructs) identified non-protective demographic factors of mental health distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

The research team initially identified various stakeholder characteristics related to demographics that demonstrated protection against mental health distress as the COVID-19 pandemic continues. This protective theme (construct) was created as a result of the collapsing of multiple sub-variable categories originally established by the review team on the affinity matrix, included within Figure 4.

The research team also identified various stakeholder characteristics related to demographics that demonstrated non-protective factors against mental health distress as the COVID-19 pandemic continues. This non-protective theme (construct) was created as a result of the collapsing of multiple sub-variable categories originally established by the review team on the affinity matrix, included within Figure 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

The pandemic has resulted in an increased prevalence of mental health distress among the population of the United States. This review surveyed the literature and identified both protective and non-protective variables associated with mental health distress in the United States during the COVID-19 era. As a result, several underlying constructs for both protective and non-protective factors were identified by the research team.

Three main underlying themes were identified in the literature by the research team that supported protective factors towards mental health distress in the U.S. (Figure 2). Demographics occurred in the literature at a rate of 16% of the total articles in the review. Personal support/self-care (16% occurrence) and income shock/financial concerns (7% occurrence) were also able to be identified, and articles were classified under each of these constructs, as identified by the team.

The research team identified three primary themes (constructs) associated with both non-protective factors associated with mental health distress during the pandemic. Non-protective variables identified were demographics (40% occurrence), personal support/self-care (29% occurrence), income shock/financial concerns (26% occurrence), health/social status (16% occurrence), and general knowledge/government mistrust (14% occurrence). Within-construct sub-variables regarding protective and non-protective factors associated with mental health distress during the pandemic were also able to be identified by the research team, and are discussed in their respective section(s) below.

4.2. Protective Theme: Demographics

For instance, Caucasians were identified in the literature as having less depression than other races [14,38]. Age was also an influencing factor on less mental distress, with both older (above 65 years old) and traditional college-age students identified in this category [20]. While citizenship [15], gender [15], religion [15], and occupation were also identified by the review team in this vein, results also indicate that individuals living in states with a lower prevalence of COVID-19, as well as rural areas, demonstrate less mental distress from the pandemic [13,15]. Additional research is required to further identify both these and other potential demographic indicators of mental health distress as being related to COVID-19 in order to further strengthen this review construct.

4.3. Protective Theme: Personal Support and Care

During the systematic literature review, several factors have been grouped into a larger category, which is coined “personal support and care”. Although demographic factors are addressed separately in this review, demographic classification, such as age, is an important distinction with the factors in this category. Having robust social networks and connections proved to be protective for all ages for mental health distress during the pandemic [4,20,26,35]. Paradoxically, a subset of young adults with underlying social anxiety disorder perceived less stress with the recommended social distancing practices. Nursing students who had effective family functioning and spiritual support experienced less mental distress during the pandemic [22]. The quality of the family relationship was found to be particularly protective in Hispanic youth and adolescents [38]. The removal from in-house school activities is postulated to increase the quality of family relationships and increase self-care behaviors, such as sleep, yet relieve youth from peer stressors prevalent in adolescence [30]. Nurses caring for COVID-19 patients reported self-care practices, such as meditation, psychological support, exercise, and sleep hygiene, to be especially important is staving off mental health distress [17].

College age students and young adults’ coping mechanisms to the pandemic, such as spiritual practices, developing a daily routine, practicing positive reframing, the use of social media and streaming services, journaling, music, reading, drawing, time with pets, and increasing physical activity, all proved to be protective [22,36]. Older adults’ protective coping mechanisms included self-reflection, reliance on memories, and reflections of life experiences [27]. Spending more time outside in daylight was protective for all ages [20]. One study examined three factors of religious variables in the American Orthodox Jewish population: intrinsic religiosity, religious coping, and trust in God, and found all three variables to be protective factors to mental health distress during the pandemic [31]. A separate study showed practice of religiosity in young American adults (age 18–29), as well as a conservative political affiliation, to also be protective [15]. Lastly, based on research about these practices in the absence of a global pandemic, adults practicing yoga, mindfulness, and healthy living habits experience less mental distress; therefore, it is suggested that this benefit would carry over as being protective during the pandemic [4].

4.4. Protective Factor: Income Shock and Financial Concerns

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a massive economic impact in the U.S., leading to the largest one-quarter economic contraction since record keeping began in 1945 [3]. During times of economic volatility, the provision of unemployment insurance can serve as an important safety net, and the research team confirmed protective variables associated with this benefit on mental health during the pandemic. Unemployment insurance was shown to mitigate the risk of mental health distress by helping people continue to meet health-related social needs, such as food and housing, and reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms [3]. This literature review validated the health benefits of unemployment insurance through the identification of protective factors associated with states that offered greater maximum unemployment insurance and/or states with more weeks of unemployment insurance. These states, in comparison to others with less generous unemployment benefits for those undergoing income shock and financial distress, showed less deleterious effects on mental health during the pandemic [3,12,13].

In addition to variation in state-level policies related to unemployment benefits during the pandemic, the researchers found that other protective policies to support citizens experiencing income shock lessened psychological distress. For example, states that implemented a moratorium on evictions or utility shutoffs and had previously expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act showed different experiences of mental health related to income shocks during the pandemic [12]. This systematic review strongly confirms that households experiencing an income shock during the pandemic were less distressed if they happen to live in states with social policies that reduce economic insecurity and ensure access to health care.

4.5. Non-Protective Theme: Demographics

Compared to the frequency of occurrences identified in the review as protective factors related to demographics (nine identified articles), non-protective factors falling within this same construct were much higher (19 identified articles). This difference suggests that demographics play a more influential role in contributing to mental health distress during the pandemic, as opposed to protecting against related distress. Additional research is required to further identify specific demographic characteristics and within-category relationship interactions of this review construct.

The following sub-variables were identified by the review team and collapsed into the non-protective demographic variable (Figure 5):

Occupation was identified by the review team as a significant non-protective demographic factor of mental distress during the pandemic, most often related to close-contact healthcare-related jobs, such as nursing and dental hygiene [2,8,22,35]. Further, those positions with ongoing COVID-19 exposure, specifically prone to airborne diseases, were identified [8,22].

4.6. Non-Protective Theme: Lack of Personal Support and Care

In the personal support and care protective factor section, social support, including family, friends, and social networks, and the quality of such relationships, were key protective factors. As such, the absence of this support network causing social isolation or a history of family traumas are significant causes of mental distress in all age groups [3,5,6,13,15,17,20,21,36]. College students and older adults alike had increased depressive and suicidal thoughts due to the feelings of loneliness, insecurity, and hopelessness brought on by social isolation [28,36]. College students related the following barriers to mitigating the psychological distress with counseling services to include a lack of insight into the severity of their symptoms, not being comfortable talking to strangers or on the phone about their concerns, and a lack of trust and discomfort in accessing school mental health services [36]. A different type of isolation negatively impacted nurses whose extensive isolation caused by their professional requirements further isolated them from family, friends, community, and political groups, causing increase mental health distress [17].

College students and adults using avoidant coping mechanisms, such as denial or disengagement, experienced increased mental health distress during the pandemic [27,36]. The use of alcohol as a coping mechanism was non-protective, and one study showed that alcohol use in the U.S. increased during the first wave of the pandemic in states with, interestingly, a lower burden of COVID-19 cases [20,26]. Unhealthy eating habits and the “pandemic baking syndrome” increased as coping mechanisms or as a product of “stay at home” and “social distancing” requirements, and led to an increase in eating disorders [6,36]. Having more liberal political beliefs and experiencing spiritual struggles were nonprotective factors experienced in US adults [15,31]. Although social connection appears to be a protective factor, having interpersonal or social media communication with COVID-19 specific content increases psychological distress in those who had had direct exposure with COVID-19 (personally infected, hospitalized, or experienced death of a loved one from COVID-19) [14].

4.7. Non-Protective Theme: Income Shock/Financial Concerns

The tremendous job loss and wage cuts during the COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns about the mental health of the population, considering the well-established findings that financial stressors are leading contributors to suicide, substance abuse, and other mental health issues. As discussed in our section on protective factors, states with different policy contexts likely influence mental health. This systematic review verifiably determined that the lack of unemployment insurance—or a lessor benefit to insulate from the shock of lost household income—is a key non-protective variable [3]. However, a non-protective thematic review goes much deeper, in that there are a wider breadth of sub-variables identified. The associations of the increase in psychological distress with income shock may be reinforced by gender, age, ethnicity, or vulnerability.

There are a constellation of factors that contribute to the worsening of mental health during the pandemic (e.g., infection concerns, social isolation), but income shock as experienced by low income households was the most significant non-protective sub-variable identified in correlation [10,21,42]. Age was also a significant non-protective theme identified by our research group. Given that young adults were disproportionately more likely to work in sectors of the economy that were shut down during the pandemic (e.g., retail, restaurants, leisure facilities), the associated financial insecurity and job loss experienced by many young people contributed to a sustained rise in depression levels [10,12,15]. The research team found that households that experienced an income shock were more likely to experience heightened levels of depression and anxiety if they were non-white, had lower levels of educational attainment, and were divorced or never married [12].

Another noteworthy non-protective sub-variable associated with income shock and mental health distress was geographic setting, as unemployment insurance and other government aid during the pandemic was shown to mitigate psychological symptoms for those primarily in non-urban areas [13]. In summary, our research group found in the systematic review of the literature that a rise in unemployment during the pandemic is associated with significantly elevated mental health problems, and that several non-protective sub-variables exist in this relationship.

4.8. Non-Protective Theme: Baseline Health/Social Status

Individuals experienced high levels of distress for a countless number of reasons throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic; two of which include preexisting medical illnesses and an unstable income as a result of a low socioeconomic status [20,21,42]. Those with preexisting health conditions, particularly mental health conditions, experienced higher levels of fear than their respective counterparts [28]. However, a combination of the two underlying health and socioeconomic status reasons revealed the most significant effect on mental health [28,35,40].

4.9. Non-Protective Theme: Lack of Knowledge and/or Lack of Government Trust

Throughout the country, there has been uncertainty surrounding the pandemic and inconsistent or culturally incompetent messaging. This has added to an increase in fear and a general lack of knowledge about the COVID-19 pandemic [2,4,13,14]. The polarized politicized environment and increased focus on social justice has further contributed to an increased burden on mental health [7,8].

5. Study Limitations

As with any systematic literature review, limitations do exist. While the review identified 42 manuscripts, only 9 articles (22%) were categorized by the research team as JHNEBP Level I (experimental study/randomized control trial). Additionally, 29 articles (70%) were classified as Level II (quasi-experimental studies), and the remaining 8% of the review articles fell within Level III (non-experimental, qualitative) and Level IV (opinion of nationally recognized experts based on research evidence/consensus panels). As a result, the research team had to utilize broader-level themes to categorize underlying constructs. Finally, this review focused on mental health and related mental distress protective and non-protective factors that were specifically identified within the U.S. This exclusion criteria was applied to the database to help narrow results to a more manageable level for the research team, while also helping to describe a single country’s protective and non-protective factors for mental health distress during the pandemic. While exclusive to only the U.S., findings may be appliable to other countries with similar environmental, economic, and governmental conditions, and this remains a strong area for future study.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review identified protective and non-protective themes regarding the effects on mental health in the nation during COVID-19. The findings suggest that factors such as occupation, financial uncertainty, and a lack of social support result in an increase in mental health distress among individuals. Healthcare students and workers experience high levels of distress relative to their counterparts. Individuals with previously diagnosed health problems experienced higher levels of mental distress. While these protective and non-protective themes vary by specific factors, the study suggests self-care, a steady income, and a strong support system positively affected mental health during the pandemic. Identified facilitators and barriers identified are directly influenced by the United States health care system, and this study suggests challenges and best practices offered by U.S. outpatient organizations that may also be beneficial for other countries.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this review in accordance with ICMJE standards. C.L., M.B. and E.W. initiated the beginning stages of the study and recruited J.P. and K.H. early in the development and review of the search criterion. All authors contributed to investigation into the research topic, participation in the method, article screening/affinity diagram creation, and discussion/analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Czeisler, M.; Lane, R.I.; Petrosky, E.; Wiley, J.F.; Christensen, A.; Njai, R.; Weaver, M.D.; Robbins, R.; Facer-Childs, E.R.; Barger, L.K.; et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, 24–30 June 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Goetz, C.M.; Sudan, S.; Arble, E.; Janisse, J.; Arnetz, B.B. Personal Protective Equipment and Mental Health Symptoms Among Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Basu, S. Unmet Social Needs and Worse Mental Health After Expiration Of COVID-19 Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation. Heal. Aff. 2021, 40, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Acharya, T. The COVID-19 Pandemic and its Effect on Mental Health in USA—A Review with Some CopingStrategies. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslau, J.; Finucane, M.L.; Locker, A.R.; Baird, M.D.; Roth, E.A.; Collins, R.L. A longitudinal study of psychological distress in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2021, 143, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, M.J.; Ly, N.K.K.; Anisman, H.; Matheson, K. Piece of Cake: Coping with COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.R.; Pilling, E.B.; Eyring, J.B.; Dickerson, G.; Sloan, C.D.; Magnusson, B.M. Political and personal reactions to COVID-19 during initial weeks of social distancing in the United States. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, P.F.; Boston-Leary, K.; Mcmillan, K.; Peterson, C. The US COVID-19 crises: Facts, science and solidarity. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2020, 67, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, A.B.; Krezanoski, P.J.; Rao, L.; El Ayadi, A.; Tsai, A.C.; Goodman, S.; Harper, C.C. Mental health among outpatient reproductive health care providers during the US COVID-19 epidemic. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Sutin, A.R.; Robinson, E. Depression reported by US adults in 2017–2018 and March and April 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 278, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, P. Factors influencing mental health among American youth in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 175, 110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.; Farina, M.P. How do state policies shape experiences of household income shocks and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic? Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 269, 113557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Nie, X. Impacts of Layoffs and Government Assistance on Mental Health during COVID-19: An Evidence-Based Study of the United States. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, J.M.; Shin, H.; Ranjit, Y.S.; Houston, J.B. COVID-19 Stress and Depression: Examining Social Media, Traditional Media, and Interpersonal Communication. J. Loss Trauma 2021, 26, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.D.; Balluerka, N.; Gorostiaga, A.; Espada, J.P.; Santed, M.Á.; Padilla, J.L.; Gómez-Benito, J. The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 and Lockdown in the Spanish Population: An Exploratory Sequential Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, S.; Hahm, H.C.; Zhang, E.; Wong, G.; Liu, C.H. Psychological correlates of poor sleep quality among U.S. young adults during COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2021, 78, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheduru-Anderson, K. Reflections on the lived experience of working with limited personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 crisis. Nurs. Inq. 2021, 28, e12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.J.; Grise-Owens, E. Foster caring in an era of COVID-19: The impact on personal self-care. Adopt. Foster. 2021, 45, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, K.; Li, J.J.; Hahm, H.C.; Liu, C.H. Psychiatric impacts of the COVID-19 global pandemic on U.S. sexual and gender minority young adults. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 299, 113855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Dailey, N.S. Mental Health During the First Weeks of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.-S.; Laurence, J. COVID-19 restrictions and mental distress among American adults: Evidence from Corona Impact Survey (W1 and W2). J. Public Health 2020, 42, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.C.; Sloan, C.; Montejano, A.; Quiban, C. Impacts of Coping Mechanisms on Nursing Students’ Mental Health during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinser, P.A.; Jallo, N.; Amstadter, A.B.; Thacker, L.R.; Jones, E.; Moyer, S.; Rider, A.; Karjane, N.; Salisbury, A.L. Depression, Anxiety, Resilience, and Coping: The Experience of Pregnant and New Mothers During the First Few Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.; Nguyen, M. The psychological consequences of COVID-19 lockdowns. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2021, 35, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindau, S.T.; Makelarski, J.A.; Boyd, K.; Doyle, K.E.; Haider, S.; Kumar, S.; Lee, N.K.; Pinkerton, E.; Tobin, M.; Vu, M.; et al. Change in Health-Related Socioeconomic Risk Factors and Mental Health During the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey of U.S. Women. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKetta, S.; Morrison, C.N.; Keyes, K.M. Trends in US Alcohol Consumption Frequency During the First Wave of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minahan, J.; Falzarano, F.; Yazdani, N.; Siedlecki, K.L. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Psychosocial Outcomes Across Age through the Stress and Coping Framework. Gerontology 2021, 61, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, C.; Macdonald, J.; Lytle, A.; Apriceno, M.; Levy, S.R. COVID-19 and ageism: How positive and negative responses impact older adults and society. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattison, K.L.; Hoke, A.M.; Schaefer, E.W.; Alter, J.; Sekhar, D.L. National Survey of School Employees: COVID -19, School Reopening, and Student Wellness. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, F.; Ortiz, J.H.; Sharp, C. Change in Youth Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Majority Hispanic/Latinx US Sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchioe, M.R.; Grossman, L.V.; Myers, A.C.; Pathak, J.; Creber, R.M. Correlates of Mental Health Symptoms among US Adults during COVID-19, March–April 2020. Public Health Rep. 2021, 136, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppas-Rindlisbacher, C.; Finlay, J.M.; Mahar, A.L.; Siddhpuria, S.; Hallet, J.; Rochon, P.A.; Kobayashi, L.C. Worries, attitudes, and mental health of older adults during the COVID -19 pandemic: Canadian and U.S. perspectives. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Daly, M. Explaining the rise and fall of psychological distress during the COVID-19 crisis in the United States: Longitudinal evidence from the Understanding America Study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, J.A. Some Relief for Nurses Is on the Way. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 47, 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, N.; Olezeski, C.L. Challenges in Providing Care for Parents of Transgender Youth during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Smith Coll. Stud. Soc. Work 2021, 91, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaier, L.; Teoh, D.; Jewett, P.; Beckwith, H.; Parsons, H.; Yuan, J.; Blaes, A.H.; Lou, E.; Hui, J.Y.C.; Vogel, R.I. Emotional health concerns of oncology physicians in the United States: Fallout during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, D.; Thij, M.T.; Bathina, K.; Rutter, L.A.; Bollen, J. Social Media Insights into US Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analysis of Twitter Data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidot, D.C.; Islam, J.Y.; Camacho-Rivera, M.; Harrell, M.B.; Rao, D.R.; Chavez, J.V.; Ochoa, L.G.; Hlaing, W.M.; Weiner, M.; Messiah, S.E. The COVID-19 cannabis health study: Results from an epidemiologic assessment of adults who use cannabis for medicinal reasons in the United States. J. Addict. Dis. 2021, 39, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Prime, H.; Johnson, D.; May, S.S.; Jenkins, J.M.; Browne, D.T. The disparate impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of female and male caregivers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 275, 113801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hegde, S.; Son, C.; Keller, B.; Smith, A.; Sasangohar, F. Investigating Mental Health of US College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Levkoff, S.E.; Jedwab, M. Material hardship and parenting stress among grandparent kinship providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of grandparents’ mental health. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarrington, J.S.; Lasser, J.; Garcia, D.; Vargas, J.H.; Couto, D.D.; Marafon, T.; Craske, M.G.; Niles, A.N. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health among 157,213 Americans. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 286, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).