Abstract

Nowadays, wearables are a must-have tool for athletes and coaches. Wearables can provide real-time feedback to athletes on their athletic performance and other training details as training load, for example. The aim of this study was to systematically review studies that assessed the accuracy of wearables providing real-time feedback in swimming. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were selected to identify relevant studies. After screening, 283 articles were analyzed and 18 related to the assessment of the accuracy of wearables providing real-time feedback in swimming were retained for qualitative synthesis. The quality index was 12.44 ± 2.71 in a range from 0 (lowest quality) to 16 (highest quality). Most articles assessed in-house built (n = 15; 83.3%) wearables in front-crawl stroke (n = 8; 44.4%), eleven articles (61.1%) analyzed the accuracy of measuring swimming kinematics, eight (44.4%) were placed on the lower back, and seven were placed on the head (38.9%). A limited number of studies analyzed wearables that are commercially available (n = 3, 16.7%). Eleven articles (61.1%) reported on the accuracy, measurement error, or consistency. From those eleven, nine (81.8%) noted that wearables are accurate.

1. Introduction

In competitive sports, athletes spend a considerable amount of time refining the technique. This enhancement in the technique will likely increase the odds of improving athletic performance at major competitions. Coaches, researchers, and performance analysts usually focus on the athletes’ sports technique because it is highly correlated to performance [1,2]. Hence, detailed and accurate information on the athletic performance and technique in training and competition settings is paramount [3,4]. Additional training details, such as training loads, are other topics of interest. In swimming sports, video analysis is the mainstream procedure to assess the technique [5,6]. However, this assessment procedure is challenging, has a steep learning curve, is very time-consuming, and is potentially disruptive of training sessions and competition [7].

During the last two decades, alternatives to video-based assessment techniques have been developed and have gained traction. These include wearables such as accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers, which are all integrated into one single unit known as “inertial measurement units” (IMUs) [8,9,10]. These sensors can provide a comprehensive set of kinematic variables, such as acceleration (by accelerometers); angular velocity (by gyroscopes); and, rotation, orientation, or heading (by magnetometers) [11]. Several other kinematic and kinetic variables can be derived or extracted from the above-mentioned data. As technology improves, wearables are becoming more affordable, user-friendly, and readily available to end-users (i.e., swimmers, coaches, performance analysts, and applied researchers). Technology developments have led to the compactness of sensors, which can be a great advantage in terms of drag and body placement [10]. The wearable can be placed on a body landmark that: (1) does not increase significantly drag resistance; (2) does not constrain the limbs’ actions; and (3) does not affect the swimmers’ displacement [10]. Incidentally, it is possible to set up several wearables concurrently on the body and increase the number of variables of interest to measure [12]. Swimming wearables can provide real-time details on lap count and stroke count per lap [13,14], swim speed and stroke frequency [15,16], and upper limbs’ asymmetries [17]. They can also detect the stroke being performed [18], as well as estimate the energetics [19] and the thrust produced by the upper limbs [20]. Even though there is considerable interest in technology gathered among end-users, it is unclear how accurate these wearables are.

The aim of this study was to systematically review the current body of knowledge on the accuracy of wearables providing real-time feedback in the sport of swimming.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search and Article Selection

As of 10 February 2022, the Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Scopus databases were searched to identify studies that included any type of wearables in a swimming setting. As an initial search strategy, the title, abstract, and keywords in the text were first identified and read carefully for a first scan and selection of the articles. If one of these fields (title, abstract, or keywords) was not clear on the topic under analysis, the complete article was read and fully reviewed to determine its inclusion or exclusion. The PI(E)CO search strategy used (P—patient, problem or population; I—intervention; E—exposure; C—comparison, control, or comparator; O—outcomes) is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

PI(E)CO (P—patient, problem or population; I—intervention; E—exposure; C—comparison, control, or comparator; O—outcomes) search strategy.

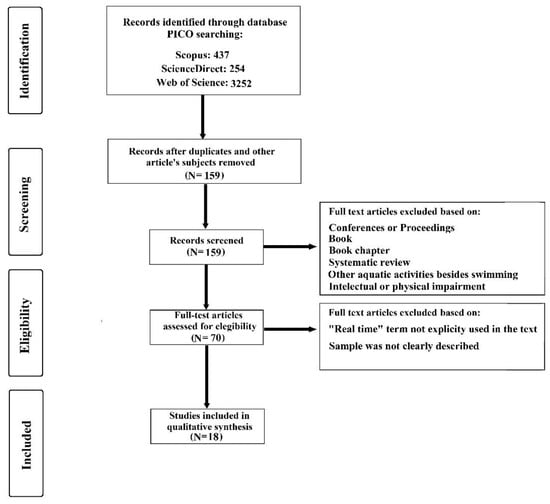

The inclusion criteria were: (1) studies written in English; (2) experimental research designs; (3) studies published in a peer-reviewed journal; (4) studies which assess swimming wearables; (5) studies which recruit healthy and able-bodied swimmers; and (6) studies which report on the use of swimming wearables streaming data to provide real-time feedback. Exclusion criteria included: (1) studies not written in English; (2) review papers, conference papers, and books; (3) studies published in non-peer reviewed journals; (4) studies not related to swimming wearables; (5) studies which recruited disabled swimmers or participants with any pathology; and (6) studies not related to the topic in question (e.g., not clearly stated “real-time” or streaming or the sample was not clearly described). Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flow diagram for identifying, screening, and checking eligibility, which then helps to determine inclusion of the articles. A total of 18 articles [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] were included in the qualitative synthesis.

Figure 1.

Summary of PRISMA flow for search strategy.

2.2. Quality of the Articles

The articles selected were screened for quality assessment by an instrument proposed and developed for this scientific field [39,40]. Two independent reviewers read all articles retained for qualitative synthesis and scored the 8 items. Each item was scored 2 points if the answer was “yes”, 1 point if the answer was “partial”, and no points if the answer was “no” [39,40]. Hence, the quality ranges between 0 (lowest quality) and 16 (highest quality). Afterwards, the Cohen’s kappa (K) was computed to assess the agreement between reviewers. It was interpreted as: (1) no agreement if K ≤ 0; (2) none to slight agreement if 0.01 < K ≤ 0.20; (3) fair if 0.21 < K ≤ 0.40; (4) moderate if 0.41 < K ≤ 0.60; (5) substantial if 0.61 < K ≤ 0.80; and (6) almost perfect if 0.81 < K ≤ 1.00.

3. Results

The quality index was 12.44 ± 2.71 points. The Cohen’s kappa yielded an almost perfect agreement between reviewers (K = 0.851, p < 0.001). Table 2 summarizes the aims of the studies, the participants´ demographics, and the swim strokes. From the 18 articles included for qualitative synthesis, eight (44.4%) [21,23,24,25,30,31,34,38] assessed wearables exclusively in front crawl, six (33.3%) [26,27,29,32,33,35] assessed wearables exclusively in all four swim strokes, two assessed wearables for the tumble turn in front crawl (11.1%) [36,37], one just assessed wearables in breaststroke (5.5%) [22], and another one assessed wearables in butterfly stroke (5.5%) [28]. Overall, 177 swimmers were recruited in all studies (103 males, 62 females, and 12 that the authors failed to note the sex of the participants). Four articles recruited elite-level swimmers (22.2%) [29,32,34,37], two articles recruited international-level participants (11.1%) [33,35], four articles recruited national-level/semi-professional participants (22.2%) [22,28,35,38], one article recruited local-level participants (5.5%) [31], and three articles recruited local/non-expert swimmers (16.7%) [22,25,36]. Conversely, six articles (33.3%) [21,23,24,26,27,30] did not report the swimmers’ competitive level.

Table 2.

List of the articles selected for qualitative synthesis, including the article aim, the participants’ demographics, and the swim stroke analyzed.

Table 3 consolidates the details on the assessed sensor, the anatomical landmark where it was placed, variables analyzed, and the main findings of the studies. Fourteen studied accelerometers (77.8%) [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,32,33,35,36,37,38], seven studied microcontroller units (MCUs) (38.9%) [22,25,26,27,28,29,37], six studied IMUs (33.3%) [21,22,23,24,28,31], three studied visual feedback (16.7%) [25,26,27], and just one studied a gyroscope (5.5%) [34].

Table 3.

Summary of the sensors selected, its specifications (size and weight), the body’s placement, variables analyzed, and the main findings.

About the anatomical landmark, eight studies placed the wearable on the lower back (44.4%) [21,22,23,29,34,36,37,38], seven on the head (38.9%) [24,25,26,27,28,33,35], and five on the wrist (27.8%) [21,25,26,27,30] (Table 3). Overall, the articles identified and/or measured variables related to kinematics and kinetics (e.g., duration of the stroke, stroke count, stroke rate, speed) during the arm stroke. Nonetheless, there were three articles that analyzed variables related to the swimmer’s body roll while performing the arm stroke (16.7%) [23,28,34], and two during the tumble turn (11.1%) [36,37]. One article estimated the energy expenditure (5.5%) [30]. Eleven articles (61.1%) [21,22,24,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,35] reported outputs related to accuracy, measurement error, or consistency. Seven papers (38.9%) [23,25,28,34,36,37,38] did not report any information about the reliability and only describe the sensors’ features and specifications. Three articles (16.7%) [30,33,35] selected commercially available wearables and remaining are non-commercial apparatus (i.e., in-house built) (Table 3). From the 11 articles that described accuracy or measurement errors: (1) 9 [21,22,24,26,27,29,31,32,33] (81.8%) reported that the wearable under study could accurately monitor the swim; (2) 1 article [30] (9.1%) conveyed mixed findings depending on the variables measured, and; (3) 1 article [35] (9.1%) noted that the wearable used was not accurate. Detailed information on the accuracy of the outputs can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the accuracy of the outputs.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to systematically review the current body of knowledge on the accuracy of wearables providing real-time feedback in the sport of swimming. The quality of the research was 12.44 ± 2.71. Most articles assessed in-house built wearables in front crawl, and measured swimming kinematics, placed on the lower back or the head, as well as the accuracy, measurement error, and consistency. The majority of the articles reported the wearables as accurate.

The quality was assessed on a scale from 0 to 16 points and the articles included had an overall score of 12.44 ± 2.71. Thus, the articles in the synthesis are deemed as being of “good” quality, or at least being closer from the upper limit of the scale. Nonetheless, the item where the articles were lacking better scores were related to negative findings. Overall, the articles did not report or elaborate on potential concerns or issues whenever using the analyzed wearables. For sports in general, it was shown that discrepancies can be found in the amount of details given in the studies that used wearable sensors [41]. On the other hand, it was pointed out that wearables can provide accurate information about biomechanical parameters [41]. Besides that, authors reported mostly in-house built wearables. It is possible that they only published their findings after the final solution was fully developed and implemented, thus solving any accuracy issues. Moreover, future research could focus on the independent assessment of wearables developed by third parties.

The articles included in this systematic review recruited swimmers with different demographics, i.e., from the recreational to elite level. From the 12 articles that described the swimmers´ demographic, 8 recruited elite, or international, or national swimmers, or semi-professional-level swimmers. The remaining ones recruited local or non-expert swimmers. Thus, researchers are prone to recruit swimmers with high expertise. This might happen because expert swimmers will be able to deliver the requested task with a good level of proficiency. That said, recruiting participants with different backgrounds is a competitive advantage when assessing the accuracy of sensors catering to a wide range of swimmers.

Near half of the articles retained for analysis (n = 8, 44.4%) [21,23,24,25,30,31,34,38] assessed the wearables exclusively in the front-crawl stroke. Indeed, front crawl is the fastest swim stroke [42] and has the largest number of competitive events [43,44,45,46]. Thus, it receives the largest interest among researchers in comparison to the other three competitive strokes (backstroke, breaststroke, and butterfly stroke). The studies aimed to develop or use wearables to monitor the stroke kinematics, including lap count, stroke count, stroke phase detection and its duration (even during breathing), swimming velocity, stroke rate, stroke length, and stroke index. Lap and stroke count are variables that are important for coaches to monitor the training volume, a training load parameter [47,48]. Conversely, literature reports that stroke kinematics (e.g., stroke rate, stroke length, stroke phase durations, etc.) play a major role in swimming performance [1,2,4]. Thus, the devices under study can be used on a daily basis by end-users to monitor the training load (e.g., volume) and swim technique (e.g., stroke rate, stroke length, stroke phase durations, etc.) with the ultimate goal of enhancing performance. Articles that assessed the four swim strokes concurrently [26,27,29,32,33] revealed that breaststroke [22] or butterfly stroke [28] had similar outputs. As for the articles that assessed the tumble turn during the front-crawl stroke, the main focus was to analyze the acceleration in each phase of the turn [36] and to establish the features of the tumble turn performance that could be identified by tri-axis acceleration time-series [37]. In swimming, the turns account for a meaningful contribution to the final race time [46,49]. These days, the turn is a key-phase of the swimming race. Most coaches and swimmers are aware how important is this phase to final race time. Therefore, providing end-users immediate feedback on the turn performance, can be an added value of these wearables.

Incidentally, none of the articles provided data on swimming propulsion. Propulsion is a main determinant of swimming velocity [50]. Moreover, propulsion data can also provide insights on the swimmers’ symmetrical/asymmetrical limb actions [51]. However, research on propulsion-selected equipment suggest that the set-up, collection, extraction, and handling of data are time-consuming and require a high level of expertise. As far as our understanding goes, literature does not provide information on the development or application of wearables that are friendly for end-users. Thus, there is an opportunity to develop wearables than can provide data on the swimmers’ propulsion in a straightforward fashion.

Most articles studied accelerometers. The selection of this type of sensors may be related to the type of task to be performed and assessed, as well as the technology available at a given point in time. For instance, studies on the tumble turn [36,37] used accelerometers and gyroscopes, and the article on the body roll [34] only used a gyroscope. Interestingly, most recent articles developed IMUs, combining the accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer. Integrating these three types of sensors enables a more comprehensive analysis, such as speed, direction, acceleration, specific force, angular rate, and magnetic fields surrounding the device [52]. Moreover, these units provide great self-independence, can work in all environments, and provide good real-time estimation [10,31]. For a seamless experience by the user, the design and development of swim wearable technology faces extra challenges in comparison to available on-land solutions. The fact that the hardware (i.e., the sensor collecting bio-signal) end-users are under water leads to an added constrain. The frequency of limbs´ actions and the ready access to data by streaming it to a third-party device, during or upon collection, should also be considered. Hence, in future pieces of research, authors are encouraged to share details on signal frame rate, feedback delay, wireless communication, among other specifications.

Regarding the anatomical landmarks, where the sensors were set up, the place of choice depends on the variables of interest. To measure swim velocity, wearables were placed on the lower back [22] (i.e., waist level, which can be a good proxy of the swimmer’s center of mass [53]), or the head (which is the landmark used to measures the swimmer’s velocity in race settings [49]). Studies where the wearable was placed on the upper-limb (forearm, wrist, or palm of the hand) aimed to measure the stroke count, stroke rate, and duration, and also helped to identify the stroke phases [21,24,25,26,27,30,31,32]. When the aim was to count the kicking (legs’ downbeat), the wearables were placed on the shanks [24]. Notwithstanding, a major concern around the use IMUs is where they should be placed. Mistakes concerning the placement of IMUs are more challenging than manufacturing variations, environmental conditions, synchronization, or integration drift [54]. Therefore, users must be mindful and careful about the body landmark where the wearable should be placed to yield the expected output.

Only three articles [30,33,35] selected commercially available wearables and the remaining used non-commercial equipment (i.e., in-house built). Hence, wearables are still in early stages of the innovation cycle, are at the development stage, and are not available to end-users. Another key topic concerns the accuracy or measurement error of wearables [41]. Indeed, it was claimed that commercial wearables may not be suitable for professional use due to the low level of accuracy [55]. Thus, the three articles aimed to learn about the accuracy of commercial wearables [30,33,35]. Overall, the study by Lee et al. [30] noted that the error rate of lap count and stroke count at various swimming speeds were within 10% for Apple and about 20% for Garmin. On the other hand, the error rate of estimating energy expenditure was higher for Apple than Garmin. Thus, the authors suggested that Apple and Garmin wearables can accurately measure lap counts and stroke counts, but the energy expenditure estimation is poor at slow or medium speeds. Two studies aimed to assess the validity of the same wearable [33,35]. However, they presented different outputs. Pla et al. [33] reported that the accuracy of the spatial–temporal variables (stroke count, swim speed, stroke rate, stroke length, and stroke index) was high in international open-water swimmers. Conversely, Shell et al. [35] noted that the total swim distance was underestimated by the wearable in comparison to video analysis. Moreover, the authors pointed out that the absolute error in a set of spatial–temporal variables was consistently higher, in comparison to video analysis [35]. Altogether, it seems that commercial wearables should undergo deeper and comprehensive benchmark analyses, in comparison to the gold-standard methods, in order to gain a better insight on its accuracy. The remaining articles [21,22,24,26,27,29,31,32] that used non-commercial wearables and measured accuracy or measurement errors noted that the wearables under study were accurate. Overall, the measured parameters were related to spatial–temporal variables, following identification and determination of the stroke phases. Therefore, based on the data gathered by this systematic review, one can suggest that non-commercial wearables (i.e., in-house-built) seem to report better accuracy than commercial solutions. However, it must be pointed out that seven articles (38.9%) [23,25,28,34,36,37,38] studying non-commercial wearables did not report any information on the reliability. As aforementioned, the main advantage of using such wearables is to spend less time collecting and handling data, thus providing the user with immediate feedback [10,41]. However, based on the findings from this systematic review, it seems that the accuracy of commercially available wearables has room for improvement. Conversely, in-house built systems should move on to other stages of the innovation cycle, thus making them more user-friendly and independently tested.

Overall, it was pointed out that there is potential for wearable technology to be used for long-term monitoring in sports [41], and specifically in swimming. Notwithstanding, wearables can become a tool with pivotal importance in other settings before the user can reach competitive and high-performance levels. This technology can eventually become a mainstream tool in teaching swimming and drowning prevention [56]. Such solutions can be used for tracking and locating the user in water, as well as for drowning detection, and can even deployed as anti-drowning systems. They can also play an important role in health settings; for injury prevention, wearables can provide coaches and athletes with the ability to observe and analyze biomechanical risk factors over a defined exposure time, for example [31,41]. This information can be even more important when delivered in real time. It must be pointed out that one of the “outcomes” of the PI(E)CO strategy was “real-time”. We chose to add this outcome because literature reports the immediate feedback (i.e., in real-time) as one of the main advantages in using wearables [33,41]. However, when performing this systematic review, several articles, e.g., [57,58,59], were not retained because they did not mention this. The main goal of these studies is to understand the validity and accuracy of wearables that provide readily available feedback to coaches and athletes with valuable information that can help them improve their performance. Thus, the competitive advantages of swimming wearables are: (1) they are user-friendly, by decreasing the level of expertise needed to set up the device, as well as collect and handle data; (2) they are less time-consuming, thus providing immediately feed-back; and (3) they can provide data with higher accuracy. Thus, future studies about wearables in swimming or any other sport should clearly mention if the wearable is user-friendly, and if it can provide real-time or immediate feedback as well as improved accuracy.

5. Conclusions

The articles retained in this systematic review on the use of wearables in swimming mainly assessed in-house built solutions in the front-crawl stroke; measured swimming kinematics, placed on the lower back or the head; and evaluated the accuracy, measurement error, or consistency. The majority of the articles reported the wearables as accurate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.B. and J.E.M.; methodology, T.M.B. and J.E.M.; data curation, J.P.O. and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.B., J.P.O., T.S. and J.E.M.; writing—review and editing, T.M.B. and J.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT—Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (grant number: UIDB/DTP/04045/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Morais, J.E.; Silva, A.J.; Garrido, N.D.; Marinho, D.A.; Barbosa, T.M. The transfer of strength and power into the stroke biomechanics of young swimmers over a 34-week period. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 18, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacca, R.; Azevedo, R.; Chainok, P.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Castro, F.A.D.S.; Pyne, D.B.; Fernandes, R.J. Monitoring age-group swimmers over a training macrocycle: Energetics, technique, and anthropometrics. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, A.J.; Cobb, J.E.; Jones, I. A comparison of video and accelerometer based approaches applied to performance monitoring in swimming. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2009, 4, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, D.; Gonjo, T.; Kawai, E.; Tsunokawa, T.; Sakai, S.; Sengoku, Y.; Homma, M.; Takagi, H. Effects of exceeding stroke frequency of maximal effort on hand kinematics and hand propulsive force in front crawl. Sports Biomech. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thow, J.L.; Naemi, R.; Sanders, R.H. Comparison of modes of feedback on glide performance in swimming. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, L.; Conceição, A.; Gonjo, T.; Stastny, J.; Olstad, B.H. Arm–Leg coordination profiling during the dolphin kick and the arm pull-out in elite breaststrokers. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 2665–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, R.; Corley, G.; Godfrey, A.; Osborough, C.; Quinlan, L.; ÓLaighin, G. Application of video-based methods for competitive swimming analysis: A systematic review. Sports Exerc. Med. 2015, 1, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgi, Y.; Ichikawa, H.; Miyaji, C. Microcomputer-based acceleration sensor device for swimming stroke monitoring. JSME Int. J. Ser. C. 2002, 45, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fulton, S.K.; Pyne, D.B.; Burkett, B. Validity and reliability of kick count and rate in freestyle using inertial sensor technology. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, F.A.D.; Vannozzi, G.; Gatta, G.; Fantozzi, S. Wearable inertial sensors in swimming motion analysis: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; James, C.; Edwards, S.; Skinner, G.; Young, J.L.; Snodgrass, S.J. Evidence for the effectiveness of feedback from wearable inertial sensors during work-related activities: A scoping review. Sensors 2021, 21, 6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroganam, G.; Manivannan, N.; Harrison, D. Review on wearable technology sensors used in consumer sport applications. Sensors 2019, 19, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bächlin, M.; Tröster, G. Swimming performance and technique evaluation with wearable acceleration sensors. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2012, 8, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Sage, T.; Bindel, A.; Conway, P.; Justham, L.; Slawson, S.; West, A. Development of a real time system for monitoring of swimming performance. Procedia Eng. 2010, 2, 2707–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Mai, J.; He, Z.; Wang, Q. IMU-based underwater sensing system for swimming stroke classification and motion analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Cyborg and Bionic Systems (CBS), Beijing, China, 17–19 October 2017; pp. 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Simbaña-Escobar, D.; Hellard, P.; Seifert, L. Influence of stroke rate on coordination and sprint performance in elite male and female swimmers. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 2078–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansiot, J.; Lo, B.; Yang, G.Z. Swimming stroke kinematic analysis with BSN. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Body Sensor Networks, Singapore, 7–9 June 2010; pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cortesi, M.; Giovanardi, A.; Gatta, G.; Mangia, A.L.; Bartolomei, S.; Fantozzi, S. Inertial sensors in swimming: Detection of stroke phases through 3D wrist trajectory. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2019, 18, 438. [Google Scholar]

- Demarie, S.; Chirico, E.; Gianfelici, A.; Vannozzi, G. Anaerobic capacity assessment in elite swimmers through inertial sensors. Physiol. Meas. 2019, 40, 064003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanotte, N.; Annino, G.; Bifaretti, S.; Gatta, G.; Romagnoli, C.; Salvucci, A.; Bonaiuto, V. A new device for propulsion analysis in swimming. Multidiscip. Digit. Publ. Inst. Proc. 2018, 2, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Dadashi, F.; Crettenand, F.; Millet, G.P.; Seifert, L.; Komar, J.; Aminian, K. Automatic front-crawl temporal phase detection using adaptive filtering of inertial signals. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, F.; Millet, G.P.; Aminian, K. A Bayesian approach for pervasive estimation of breaststroke velocity using a wearable IMU. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2015, 19, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.; Schaffert, N.; Ploigt, R.; Mattes, K. Intra-cyclic analysis of the front crawl swimming technique with an inertial measurement unit. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, S.; Coloretti, V.; Piacentini, M.F.; Quagliarotti, C.; Bartolomei, S.; Gatta, G.; Cortesi, M. Integrated timing of stroking, breathing, and kicking in front-crawl swimming: A novel stroke-by-stroke approach using wearable inertial sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagem, R.M.; O’Keefe, S.G.; Fickenscher, T.; Thiel, D.V. Self contained adaptable optical wireless communications system for stroke rate during swimming. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 3144–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagem, R.M.; Thiel, D.V.; O’Keefe, S.; Fickenscher, T. Real-time swimmers’ feedback based on smart infrared (SSIR) optical wireless sensor. Electron. Lett. 2013, 49, 340–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagem, R.M.; Haelsig, T.; O’Keefe, S.G.; Stamm, A.; Fickenscher, T.; Thiel, D.V. Second generation swimming feedback device using a wearable data processing system based on underwater visible light communication. Procedia Eng. 2013, 60, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeng, C.C. Hierarchical linear model approach to explore interaction effects of swimmers’ characteristics and breathing patterns on swimming performance in butterfly stroke with self-developed inertial measurement unit. J. Comput. 2021, 32, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Le Sage, T.; Bindel, A.; Conway, P.P.; Justham, L.M.; Slawson, S.E.; West, A.A. Embedded programming and real-time signal processing of swimming strokes. Sports Eng. 2011, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, H.; Park, S. Accuracy of swimming wearable watches for estimating energy expenditure. Int. J. Appl. Sports Sci. 2018, 30, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangia, A.L.; Cortesi, M.; Fantozzi, S.; Giovanardi, A.; Borra, D.; Gatta, G. The use of IMMUs in a water environment: Instrument validation and application of 3D multi-body kinematic analysis in medicine and sport. Sensors 2017, 17, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, M.S.; Huang, K.C.; Lu, T.H.; Lin, Z.Y. Using accelerometer for counting and identifying swimming strokes. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2016, 31, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, R.; Ledanois, T.; Simbana, E.D.; Aubry, A.; Tranchard, B.; Toussaint, J.F.; Sedeaud, A.; Seifert, L. Spatial-temporal variables for swimming coaches: A comparison study between video and TritonWear sensor. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach 2021, 16, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, D.D.; James, D.A.; Lee, J.B. Visualization of wearable sensor data during swimming for performance analysis. Sports Technol. 2013, 6, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shell, S.J.; Clark, B.; Broatch, J.R.; Slattery, K.; Halson, S.L.; Coutts, A.J. Is a head-worn inertial sensor a valid tool to monitor swimming? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2021, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slawson, S.; Conway, P.; Justham, L.; Le Sage, T.; West, A. Dynamic signature for tumble turn performance in swimming. Procedia Eng. 2010, 2, 3391–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slawson, S.E.; Justham, L.M.; Conway, P.P.; Le-Sage, T.; West, A.A. Characterizing the swimming tumble turn using acceleration data. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part P J Sports Eng. Technol. 2012, 226, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, A.; Thiel, D.V. Investigating forward velocity and symmetry in freestyle swimming using inertial sensors. Procedia Eng. 2015, 112, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jorayeva, M.; Akbulut, A.; Catal, C.; Mishra, A. Machine learning-based software defect prediction for mobile applications: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical Report; EBSE: Goyang-si, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adesida, Y.; Papi, E.; McGregor, A.H. Exploring the role of wearable technology in sport kinematics and kinetics: A systematic review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, P.; Brown, P.; Chengalur, S.N.; Nelson, R.C. Analysis of male and female Olympic swimmers in the 100-meter events. J. Appl. Biomech. 1990, 6, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, R.; Brown, P.; Cappaert, J.; Nelson, R.C. Analysis of 50-, 100-, and 200-m Freestyle Swimmers at the 1992 Olympic Games. J. Appl. Biomech. 1994, 10, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barroso, R.; Crivoi, E.; Foster, C.; Barbosa, A.C. How do swimmers pace the 400 m freestyle and what affects the pacing pattern? Res. Sports Med. 2021, 29, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipińska, P.; Allen, S.V.; Hopkins, W.G. Modeling parameters that characterize pacing of elite female 800-m freestyle swimmers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, J.E.; Barbosa, T.M.; Forte, P.; Bragada, J.A.; Castro, F.A.D.S.; Marinho, D.A. Stability analysis and prediction of pacing in elite 1500 m freestyle male swimmers. Sports Biomech. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganzevles, S.; Vullings, R.; Beek, P.J.; Daanen, H.; Truijens, M. Using tri-axial accelerometry in daily elite swim training practice. Sensors 2017, 17, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyne, D.B.; Lee, H.; Swanwick, K.M. Monitoring the lactate threshold in world-ranked swimmers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, J.E.; Marinho, D.A.; Arellano, R.; Barbosa, T.M. Start and turn performances of elite sprinters at the 2016 European Championships in swimming. Sports Biomech. 2019, 18, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.C.; Marinho, D.A.; Neiva, H.P.; Costa, M.J. Propulsive forces in human competitive swimming: A systematic review on direct assessment methods: Propulsive forces in competitive swimming. Sports Biomech. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.E.; Barbosa, T.M.; Lopes, V.P.; Marques, M.C.; Marinho, D.A. Propulsive force of upper limbs and its relationship to swim velocity in the butterfly stroke. Int. J. Sports Med. 2021, 42, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ghazilla, R.A.R.; Khairi, N.M.; Kasi, V. Reviews on various inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensor applications. Int. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2013, 1, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, R.J.; Ribeiro, J.; Figueiredo, P.; Seifert, L.; Vilas-Boas, J.P. Kinematics of the hip and body center of mass in front crawl. J. Hum. Kinet. 2012, 33, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Brantley, J.S.; Kim, T.; Ridenour, S.A.; Lach, J. Characterising and minimising sources of error in inertial body sensor networks. Int. J. Auton. Adapt. Commun. Syst. 2013, 6, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, L.; Komar, J.; Leprêtre, P.M.; Lemaitre, F.; Chavallard, F.; Alberty, M.; Houel, N.; Hausswirth, C.; Chollet, D.; Hellard, P. Swim specialty affects energy cost and motor organization. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Srinivasan, K. A novel drowning detection method for safety of swimmers. In Proceedings of the 2018 20th National Power Systems Conference (NPSC), Tiruchirappalli, India, 14–16 December 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, R.; Quinlan, L.R.; Corley, G.; Godfrey, A.; Osborough, C.; ÓLaighin, G. Evaluation of the Finis Swimsense® and the Garmin Swim™ activity monitors for swimming performance and stroke kinematics analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthusamy, S.; Subramaniam, A.; Balasubramanian, K.; Purushothaman, V.K.; Vasanthi, R.K. Assessment of vo2 max reliability with Garmin smart watch among swimmers. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma Res. 2021, 11, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Olstad, B.H.; Zinner, C. Validation of the Polar OH1 and M600 optical heart rate sensors during front crawl swim training. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).