Abstract

The worldwide occurrence of potentially traumatic events (PTEs) in the life of children is highly frequent. We aimed to identify studies on early mental health interventions implemented within three months of the child/adolescent’s exposure to a PTE, with the aim of reducing acute post-traumatic symptoms, decreasing long term PTSD, and improving the child’s adjustment after a PTE exposure. The search was performed in PubMed and EMBASE databases resulting in twenty-seven articles meeting our inclusion criteria. Most non-pharmacological interventions evaluated had in common two complementary components: psychoeducation content for both children and parents normalizing early post-traumatic responses while identifying post-traumatic symptoms; and coping strategies to deal with post-traumatic symptoms. Most of these interventions studied yielded positive results on outcomes with a decrease in post-traumatic, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. However, negative results were noted when traumatic events were still ongoing (war, political violence) as well as when there was no or little parental involvement. This study informs areas for future PTSD prevention research and raises awareness of the importance of psychoeducation and coping skills building in both youth and their parents in the aftermath of a traumatic event, to strengthen family support and prevent the occurrence of enduring post-traumatic symptoms.

1. Introduction

The worldwide occurrence of potentially traumatic events (PTEs) in the life of children and adolescents is highly frequent, including maltreatment, neglect, abuse, bullying, as well as war, displacement, and armed conflict [1,2,3,4,5]. In a survey involving 24 countries across the globe, the World Mental Health (WMH) reported that 70% of the populations were exposed at least once in their life to a PTE, with higher rates of exposure among children, adolescents, and young adults [6]. Moreover, Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is shown to develop more frequently when the traumatic events occur during childhood and adolescence [7,8,9].

Most studies estimate that spontaneous recovery for both adults and youth after exposure to PTEs is the norm and that most trauma-exposed individuals manifest various levels of acute post-traumatic stress reactions and then regain their baseline functioning over several weeks [10,11]. However, complex individual and contextual factors as well as the type of the PTE itself might lead to a failure of recovery, since a substantial 6–20% of individuals go on to develop PTSD [12,13,14]. Given the number of youths who encounter PTEs each year worldwide, the risk of developing PTSD is still high [15,16], leading to interpersonal and educational challenges as well as a significant impact on the child and family functioning [17,18,19]. Moreover, exposure to adverse and traumatic childhood experiences increases the risk of both physical and mental illnesses as well as substance use disorders in adult life, leading to reduced social and economic opportunity and impaired role functioning [20,21,22,23,24].

Emerging evidence on the dysfunctional brain circuits underlying PTSD focuses on the role of altered brain activity and connectivity in the fear extinction process that is commonly found in PTSD [25,26,27,28,29,30]. More specifically, a smaller volume and altered activity patterns in the ventromedial region of the prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) have been observed in patients with PTSD, suggesting the implication of frontal lobe circuitry in altered fear extinction features [25,26]. In a recent study conducted on patients with lesions in the ventromedial portion of the prefrontal cortex, the authors reveal that the vmPFC is involved in the acquisition of emotional conditioning, and assess how bilateral lesions of the vmPFC compromise the generation of a conditioned psychophysiological response during the acquisition of threat conditioning (i.e., emotional learning) which may lead to the perpetuation of PTSD and anxiety symptoms [25]. Another recent theoretical review discussed the distinct yet fundamental role of anterior/posterior subregions of the vmPFC in the processing of safety-threat information and in the evaluation and representation of stimulus-outcome’s value needed to produce sustained physiological responses [26]. These functional and structural alterations of the neural networks that seem to underlie fear conditioning and learning, particularly in PFC, might contribute to the complex etiology of anxiety and traumatic stress syndromes and have important treatment implications [31].

The high rates of traumatic exposure and associated clinical and neurobiological manifestations, along with an elevated public health burden, indicate the importance of early efficient interventions at a secondary prevention level, that address acute posttraumatic stress reactions in the aftermath of a traumatic event and aim at decreasing the risk of developing long-term PTSD while increasing recovery and adjustment after exposure to a traumatic event [10,32,33,34].

Current international guidelines for early and acute post-traumatic interventions shift recommendations away from psychological debriefing and toward Psychological First Aid (PFA) [35,36]. However, evidence is lacking regarding the efficiency of PFA in preventing long term PTSD, despite being often recommended as a first line intervention in various trauma guidelines, especially in humanitarian settings and complex emergencies [37,38]. Psychological First Aid was developed by the World Health Organization with the aim of providing affordable first-line psychosocial support by any lay person participating in relief efforts for populations affected by complex emergencies within hours or days of the onset of traumatic events [39]. It is, therefore, a psychosocial intervention rather than a clinical one, and its aim is to provide safety and protection from further harm, assist in accessing basic needs, offer non-intrusive support, and link to available services and social support systems [37,39]. Although it seems relevant to implement it as immediate psychosocial assistance in acute settings, instead of psychological debriefing, it does not seem to be enough on its own as an early intervention to prevent the later occurrence of PTSD.

Controlled clinical trials among adults recently exposed to a PTE find that the risk of PTSD can be decreased by cognitive behavioral treatments targeting symptom reduction and the enhancement of adaptive coping strategies [40,41]. In youth, however, data on secondary prevention of trauma-related disorders are scarce. Epidemiological studies on risk and protective factors for PTSD in children and adolescents show that in the early periods following exposure to a traumatic event, family and social support are crucial in contributing to children’s adjustment and coping with posttraumatic stress and in decreasing the risk of developing PTSD [42,43,44]. Family support consists of being actively present and available to the child following the onset of the traumatic event, modeling to the child efficient coping, successfully maintaining routines and stability, and offering protection and reassurance as needed [45].

Other protective factors established are the quality of family relationships, particularly caregiver-child relationships, as well as child and caregiver emotional regulation skills [45,46]. Parents who can support effective coping through modeling and coaching, while being attentive to their children’s needs and concerns, facilitate children’s adjustment following a PTE exposure [45,47,48]. All these protective factors could be the targets of an early intervention to prevent PTSD in youth and highlight the need for clinical treatments complementary to PFA, that increase parental coping strategies and shift the focus from pure symptom reduction to skill development in secondary prevention objectives during the peri-traumatic period. In this review, we aimed to identify studies on early mental health interventions (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) implemented within three months of the child/adolescent’s exposure to a PTE, with the goal of decreasing acute post-traumatic symptoms and the risk of long-term PTSD.

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

We searched for articles that met the below inclusion criteria:

Population of interest. Children and adolescents (ages 1 to 20 years old) were assigned to mental health interventions aiming at the secondary prevention of PTSD and provided within 3 months of the child or adolescent’s exposure to a traumatic event. Interventions targeting adults aged 20 and above were excluded from the study. Interventions occurring more than 3 months after the exposure to a PTE were excluded from the study. Articles reporting on interventions targeting ongoing trauma (war/conflict/violence) were included in the review.

Event of interest. Potentially traumatic events included burn injuries, falls and sporting injuries, motor vehicle accidents, sexual or physical abuse, medical events, procedures, or treatments, natural disasters, war/conflict/violence, and various accidental and unintentional injuries.

Types of intervention. There were no restrictions on the type of mental health interventions provided, which ranged from pharmacological interventions to psychosocial and structured cognitive-behavioral interventions, among others.

Study design. There were no restrictions made on the design of the study.

We only included articles that were published in the English or French languages.

2.2. Information Sources

The electronic databases searched were PubMed and Embase. No restrictions were made on the dates of article publication. The research strategy was developed with a professional university librarian who assisted us in the exportation of retrieved records. We used both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text words. We searched PubMed by using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and included the terms Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic, prevention and control with the filters: “Child: birth-18 years”, “Adolescent: 11–20 years”. We searched Embase by using keywords and included ‘post-traumatic stress disorder”, with filters excluding Medline, and restricted to adolescents, children, infants, and newborns. No other restrictions were applied while conducting the search. The search yielded 1268 articles, with 27 articles meeting the inclusion criteria.

2.3. Study Selection

The research team developed screening guides for the specific purpose of this review, that were used by two team members to screen independently and in duplication, both the titles and abstracts of the identified citations, as well as the full text. Full texts were retrieved based on the title and abstract screening whenever it was evaluated as eligible by at least one of the two reviewers. A third reviewer from the team member was consulted anytime there was a disagreement regarding the full-text screening by the two main reviewers.

2.4. Data Abstraction

The research team initially developed standardized data abstraction forms that were tested and then used by the reviewers to abstract data from selected articles. Research characteristics abstracted included type of intervention, study design, intervention components, the timeframe between the exposure to the PTE and the intervention, type of traumatic event, target population characteristics, age of target population, targeted outcomes, and findings. We specifically looked at the rates of post traumatic symptoms and measures of coping/adaptive strategies following the interventions tested.

3. Results

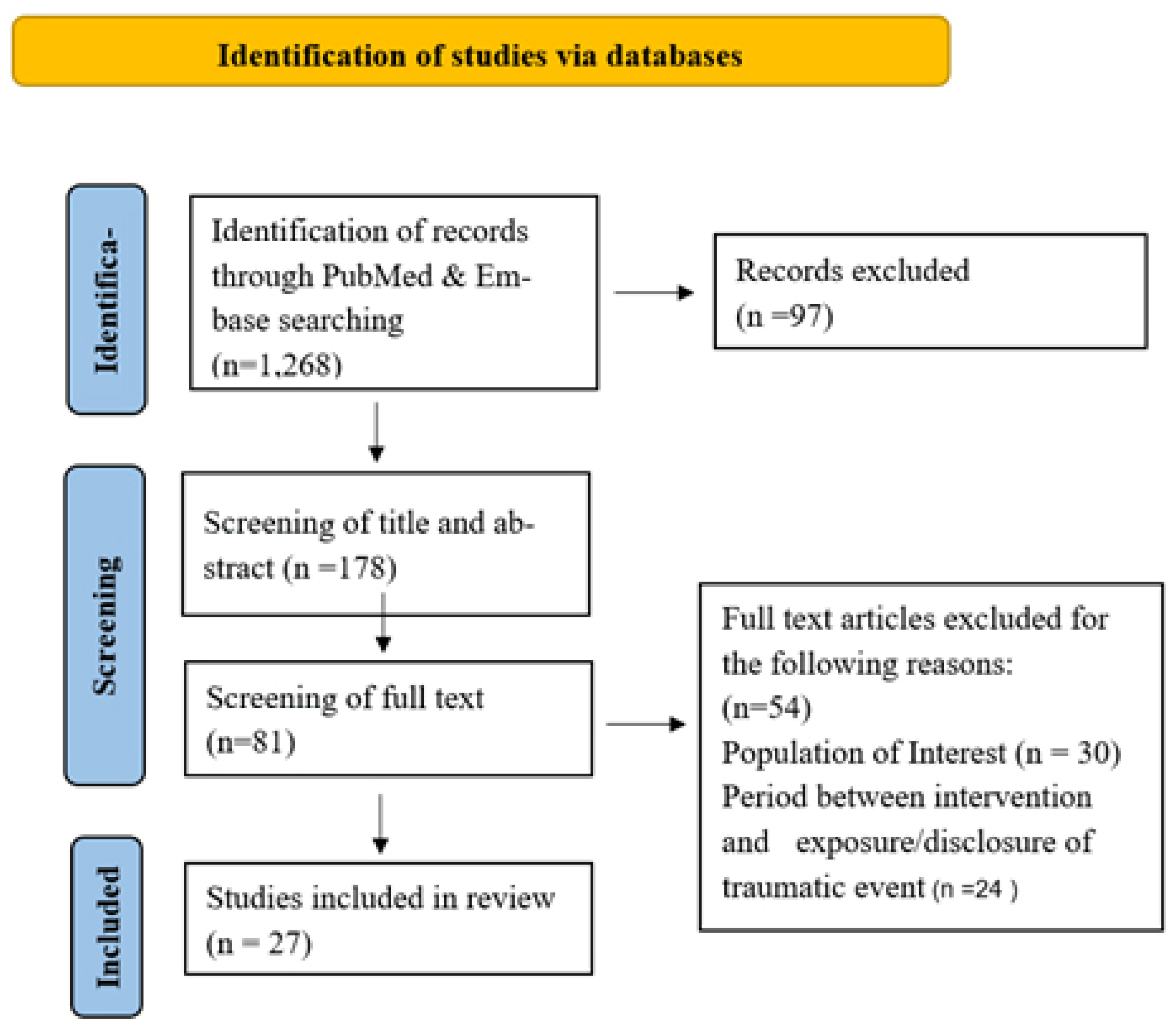

The findings of our search are presented according to the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols’ (PRISMA) flowchart (Figure 1). The search on PubMed and Embase yielded 1268 records, and we retained 178 for the title and abstract screening. Out of those, 97 records did not meet our eligibility criteria, leaving 81 records for full-text screening, out of which 54 records were excluded for not satisfying the eligibility criteria (different population of interest, interventions occurring after more than 3 months of the trauma incident). Thus, only 27 papers were retained for analysis and review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart.

3.1. Research Characteristics

The research characteristics and main findings for each article are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. The design of the studies included 20 randomized control trials, three experimental studies, one prospective longitudinal study, one meta-analysis, one case report, and one retrospective review of medical records. Interventions implemented in the studies included pharmacotherapy, Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention (CFTSI), music therapy, structured cognitive-behavioral intervention, information provisioning, stepped preventive care, web-based early intervention and psycho-educational intervention, provision of coping skills and coaching strategies, psychoeducation, structured debriefing process, psychosocial interventions consisting of cognitive-behavioral techniques and various other techniques, hypnosis, in addition to massage and humor therapy. The time of intervention after the traumatic event ranged between 6 h and 60 days. Four studies had interventions carried out during an ongoing traumatic event, which was either war or violent conflict. Traumatic events included burns, falls, motor vehicle accidents, sexual and physical abuse, sports injuries, physical assaults, animal bites, surgery, acute medical events, natural disasters, violence, and war. The target population’s age ranged from 12 months to 20 years old.

Table 1.

An overview of studies’ research characteristics.

Table 2.

An overview of the studies’ findings and statistical significance.

3.2. Pharmacological Interventions

Seven studies explored the efficiency of early pharmacotherapy in reducing the psychological impact of traumatic events [49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. The traumatic events that required intervention were burn injuries [51,52,53,54,55], and physical [50] or unintentional injuries [49]. Intervention components included opioid administration [49], propranolol treatment [50,51,52], morphine administration [52,55], and sertraline administration [54]. Outcomes targeted were PTSD [49,50,51,52,53,54,55], in addition to anxiety and depression [51]. Three studies were double blind randomized control trials [50,51,54] in which the control group received a placebo in place of the treatment under study [50,54] or a different type of intervention (non-propranolol treatment) [51]. Opioid medication overall, and morphine specifically, was evaluated in three studies based on previous research showing that increased endorsed pain is positively associated with current and future PTSS [49]. Opioid administration did not prove to mediate the association between the pain endured and post-traumatic stress (PTS) [49], while one study proved the effectiveness of morphine in decreasing PTSS, especially arousal symptoms [55]. The other study proved a positive association between the dose of morphine and reduction in PTSD symptoms [52]. Sertraline was another drug shown to be moderately effective in preventing PTSD symptoms in comparison to placebo. However, the change was only significant in symptoms reported by parents and not in symptoms perceived by the children themselves [54].

3.3. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

3.3.1. Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention (CFTSI)

Two studies examined the efficiency of the CFTSI in reducing the psychological impact of traumatic events [10,56]. The traumatic events that required the intervention were different in nature and included among others, physical assaults [10,56], injuries [10], witnessing violence [10], animal bites [10], motor vehicle accidents [10], sexual abuse [10,56], and threats of violence [10]. Intervention components included sessions differently administered to the caregiver alone, the child alone, and the caregiver and child together. CFTSI sessions included various components, such as psychoeducation, case management, providing support and strengthening coping skills, improving child-caregiver communication, and normalizing symptoms and feelings [10]. Outcomes targeted were PTSD [10,56], and anxiety [10]. Both studies (one RCT and one multi-site meta-analysis) revealed that CFTSI had a positive impact on reducing PTSD following exposure to a PTE. The RCT showed that the intervention group presented fewer PTSD diagnoses in comparison with the control group and had significantly lower anxiety scores 3 months following the intervention [10]. In the other study, the authors used a multi-site meta-analytic approach to evaluate pooled and site-specific therapeutic effect sizes of the CFTSI for both caregivers and children, based on data from 10 community treatment sites trained in CFTSI. Findings reveal that CFTSI was significantly correlated with reductions in PTS in children, but also with significant improvements in post-traumatic stress scores in 62% of caregivers participating in the study [56].

3.3.2. Music Therapy

One RCT investigated the effect of music therapy on reducing the psychological impact of traumatic events compared to a control group receiving standard care [57]. The traumatic event that required the intervention was hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT). The intervention follows a patient-centered approach where children choose the musical instrument and are solicited to interact by singing and listening with the therapist. The sessions may remain wordless, or the child may choose to express any emotions or sensations that emerge. The targeted outcome was physiological parameters (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation) used as a measure of stress level and post-traumatic arousal symptoms. The study revealed that the intervention lowered the heart rate of participating children, suggesting a decreased stress level, and potentially lower risk of PTSD development according to the authors 4 to 8 h after the intervention [57].

3.3.3. Structured Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention

One experimental uncontrolled study explored the effect of cognitive-behavioral intervention in reducing psychological harm following exposure to a tsunami in Thailand [58]. Intervention components included teaching children how to manage post-traumatic stress symptoms using cognitive behavioral techniques. The targeted outcome was the measure of post-traumatic symptoms using the Children’s Impact of Events Scale (CRIES-13). Findings revealed that the CRIES score significantly decreased when the children were already prone to PTSD [58], and significantly increased in other children 2 weeks after the intervention.

3.3.4. Psychosocial Interventions

Three cluster RCTs [59,61,62] and one RCT [60] examined the effect of school-based, group format psychosocial interventions [59,61,62] and a family focused psychosocial intervention [60] on reducing psychological harm from war/conflict [59,61,62] and political violence [62]. Intervention components included cognitive-behavioral techniques [59,61], creative-expressive, experiential therapy, and cooperative play [59,61], leadership skills program, cinema clips, relaxation technique scripts [60], trauma-processing activities, and creative-expressive elements [62]. Outcomes targeted included PTSD [59,60,61,62], depressive symptoms [59,60,61,62], anxiety symptoms [59,60,61,62], psychological difficulties [59,61,62], function impairment [59,62], conduct problems [60], trauma idiom [62], aggression [62], coping [62], social support [62], and family connectedness [62]. A psychosocial intervention based in the schools in the context of Nepal’s conflict indicated moderate beneficial effects in the short-term among the intervention group characterized by reduced aggression among boys and increased prosocial behaviors among girls, along with an increased sense of hope reported by older children. However, there was no reduction in posttraumatic symptoms [59]. An intervention with youth at risk of attack and exposed to war in the north-eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, and focusing on families, demonstrated decreased post-traumatic symptoms among participants in comparison to controls, in addition to significant improvements in depressive and anxiety symptoms, a moderate increase in pro-social scores, and moderate-large decrease in conduct problems 3 months after the intervention [60]. A study examining the effects of a preventive mental health school-based intervention for children living in war-affected Sri Lanka did not report any effects on primary outcomes of intervention after 1 week and 3 months besides conduct problems which were stronger for younger children and specific subgroups. Additionally, when children experienced fewer ongoing war-related stressors, the effects of the intervention were stronger on anxiety, PTSD, and functional impairment [61].

In a study among school aged children living in communities affected by violence in Indonesia, the intervention evaluated led to reductions in posttraumatic stress symptoms and helped instill self-reported hope after 1 week and 6 months. However, it did not lead to a decrease in traumatic-stress associated symptoms, functional impairment, or internalizing symptoms [62].

3.3.5. Hypnosis

One study of four case reports explored the effect of hypnotic therapy on reducing psychological impacts following exposure to a traumatic physical injury [63]. Intervention components included different hypnotic techniques. The targeted outcome was PTSD. The study revealed that patients clinically improved after several sessions of hypnosis [63]. It was not clearly presented how PTSD was measured or how symptoms were assessed as improvements were either self-reported by the patients or reported by the physicians. Throughout the cases, it is mentioned how patients reported better sleep without assisting medications, fewer nightmares and flashbacks.

3.3.6. Psychological Intervention

One RCT examined the efficiency of a single-session psychological intervention in decreasing psychological harm in children aged 7–16 recently exposed to road traffic accidents at 2 or 6 months post-intervention [64]. The intervention was a four step process that included reconstructing the accident, creating a narrative of the trauma, identifying appraisals related to the accident, and psychoeducation. A psychologist then presented helpful strategies and advice on dealing with acute stress reactions. The outcomes targeted included PTSD symptoms, depression, and behavior. The findings revealed no significant differences in post-traumatic symptoms, however, the intervention demonstrated effectiveness in decreasing depressive symptoms as well as externalized behaviors in preadolescent children [64].

3.3.7. Complementary Intervention

One RCT investigated the efficiency of a complementary intervention in decreasing psychological harm following stem cell transplantation (SCT) as opposed to standard care at week + 24 [65]. A total number of 171 children and their parents were recruited from four different sites and assigned randomly to either a child-focused intervention; a family intervention; or standard clinical care. The child focused intervention consisted of massage and humor therapy; the family intervention included relaxation/imagery. Depression, posttraumatic stress, HRQL, and benefit finding, were the targeted outcomes measured. The study revealed significant improvements in all outcomes for all three groups and there were no significant differences between the three intervention groups [65].

3.3.8. Debriefing

One RCT examined the effect of debriefing on reducing psychological harm following exposure to road traffic accidents [66]. The intervention was manualized and researchers guided the child through a structured debriefing where the trauma was reconstructed. The child was encouraged to express thoughts and emotional reactions and was given information on how to cope. The targeted outcomes were self-reported measures of psychological distress and diagnostic criteria for PTSD The study revealed no significant gains in the debriefing group in comparison to the control group at 8 months follow-up [66].

3.3.9. Information Provisioning Intervention

Two RCTs examined the effect of information provisioning on reducing psychological harm following motor vehicle accidents [67], falls [67], sporting injuries [67], and accidental injuries [68]. Intervention components included booklets provided to parents [67,68], and children [68], aiming at normalizing traumatic stress response [67,68], and reliving trauma reactions through different strategies [68]. Outcomes targeted were anxiety and PTS symptoms in children and parents [67], and long-term PTS reactions [68]. One of the studies assessing outcomes after 1 and 6 months revealed a decrease in overall PTSS, parental posttraumatic intrusion symptoms, and anxiety symptoms among children in the intervention group [67]. The other study revealed that children in the control group had significantly higher post-traumatic symptoms at 6-month follow-up compared to children in the intervention group only when initial emotional distress was elevated [68].

3.3.10. Psychoeducation and Coping Interventions

Three RCTs examined the effect of psychoeducation [69,70,71], while three RCTs [72,73,74]–of which one multi-site RCT [72] and one cluster RCT [74] examined the effect of coping interventions, on reducing psychological harm following unintentional injuries [69,70,72,74], medical events [73,74], pediatric injuries [71], and other causes [74]. Psychoeducation components used included a booklet for parents and a web page for children aimed at normalizing and relieving trauma responses [69]; two sessions that incorporated psychoeducation and semi-structured interviews [70]; and practical information integrated into psychoeducation and methods for parents to assist children during post-injury [71]. Outcomes targeted were PTSD [69,70,71], anxiety [69,70], and depression [40,41]. One of the studies revealed that children in the intervention group manifested an improvement at 4–6 weeks and 6 months follow-up in anxiety symptoms, as well as a reduction in trauma symptoms in children with higher baseline trauma scores, while children in the control group had worsening symptoms [69]. However, the other two studies revealed that there was no reduction in depression [70], anxiety, PTSD [70,71], or an increase in health-related quality of life [70], or parent knowledge [42] in the intervention arm as opposed to control groups at follow-up at 6 months [70] and 6 weeks follow-up [71].

The other studies incorporated different components of coping, such as narrative [72], developmentally appropriate resources, and games [72,73], psychoeducation [72,74], and coping strategies [72]. Targeted outcomes were PTSD symptoms [72,73], and severity [72], PTSD diagnosis [72], functional impairment [72], behavioral difficulties at different points in time [72], maternal anxiety and beliefs [74], depression [74], parental stress [74], parent involvement in children’s care [74], child adjustment [74]. One of the studies revealed a significant impact of the intervention on post-traumatic stress severity over time, PTSD diagnosis, functional impairment, and behavioral problems at 3- and 6-months follow-up [72]. The second study, which was online self-directed in nature also revealed that the intervention could have a preventive persistent effect on posttraumatic stress after 6 or 12 weeks [73]. The third study assessing outcomes at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and which was intended for mothers and children revealed positive functional and emotional coping outcomes among mothers resulting in decreased adjustment problems in children [74].

4. Discussion

All articles selected for review were published after the year 2000, confirming that the subject of early intervention in the peritraumatic phase to prevent the occurrence of PTSD among children and adolescents is a relatively new and understudied phenomenon, in contrast with the abundant publications on the treatment of chronic PTSD. Our review included mental health interventions implemented within three months of a PTE, with the aim of preventing PTSD and improving the child’s adjustment and functioning after a PTE exposure. We found 27 articles that met our eligibility criteria, of which seven studies evaluated pharmacological interventions and twenty studies assessed non-pharmacological interventions.

4.1. Pharmacological Interventions

Regarding pharmacological interventions, Sertraline was shown to be moderately effective in preventing PTSD symptoms in comparison to placebo on parent-reported symptoms [54], while morphine administration in the acute phase was shown to be associated with decreased PTSS arousal symptoms [55]. However, the results regarding morphine should be carefully interpreted, since it was administered in the context of burn injuries, and should not be generalized to all types of PTE. More specifically, morphine might play a preventive role by reducing endorsed pain caused by the burn injury, which was shown to be associated with a decrease in current and future PTSS [49]. Propranolol, however, was not shown to be efficient in reducing PSS or preventing PTSD in two RCTs and one retrospective review of medical records [50,51,53]. A deeper understanding of fear learning neural networks involved in traumatic exposure and PTSD may contribute to the advancement and implementation of alternative treatments for traumatic stress symptoms [31]. For example, a recent review described the potential and effectiveness of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) to interfere and modulate the abnormal activity of neural circuits (i.e., amygdala-mPFC-hippocampus) involved in the acquisition and consolidation of fear memories, which are altered in PTSD, depression and anxiety disorders [75]. Similarly, another recent study illustrated the therapeutic potential of NIBS as a valid alternative in the treatment of abnormally persistent fear memories that characterize patients with anxiety disorders that are resistant to psychotherapy and/or drug treatments [76]. Although this therapeutic technique might be more relevant in the context of enduring PTSD symptoms rather than as an early intervention in the peritraumatic phase, it is important to gain a better understanding of the alterations in neurobiological as well as endocrinological activity that can be a target for more precise and individualized innovative treatments [77]. In this regard, alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary (HPA) axis and the involvement of inflammation seem to be implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD [77,78] and might be a target for biological treatment. In a recent meta-analysis of hydrocortisone as a potential preventive or curative treatment for PTSD, hydrocortisone appears to be a promising and efficient low-cost medication for the prevention of PTSD among adults but there are no available studies among children and adolescents

4.2. Non Pharmacological Interventions

In line with research on protective factors supporting recovery following a traumatic event, which asserts the role of family support [45,46,47,48], most non-pharmacological interventions evaluated involved parents as well as children [10,56,60,64,65,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. Those interventions had in common the emphasis on two distinct but complementary components: psychoeducation content for both children and parents on trauma reactions, normalizing early post-traumatic responses while identifying post-traumatic symptoms and coping strategies to deal with post-traumatic symptoms through cognitive behavioral techniques and relaxation techniques. Most of these interventions studied yielded positive results on outcomes with a decrease in post-traumatic symptoms as well as anxiety and depression. However, Kassam-Adams et al., in an RCT examining the prevention of PTSD based on psychoeducation around incorporated into pediatric care [70], found no reduction in PTSD or depression severity, which reveals that psychoeducation alone may not be sufficient to prevent PTSD, especially since it was two-session interventions only. The other RCTs that had negative results evaluated psychosocial interventions in the context of ongoing traumatic events (war and armed conflicts) [59,61,62] and did not include parents as active participants in the intervention. These negative results may be due to the context of ongoing traumatic stressors and war, where international recommendations on mental health in complex crisis settings emphasize community-based approaches that help face everyday stressors rather than clinical, individual-based approaches focused on post-traumatic symptoms [36,79,80]. With this particular type of PTE (war and armed conflicts), mental health interventions that seem to be needed to buffer the effects of traumatic events are interventions that strengthen community and family support and networks, social engagement and help regain a sense of purpose amidst ongoing adversity.

One intervention that looks promising is the CFTSI, a brief early intervention elaborated at the Yale Child Study Center for children seven years old and older who have recently experienced a potentially traumatic event (PTE). CFTSI is a five to eight-session family-focused model that aims to strengthen parents’ support of the child by facilitating the identification of common child reactions to potentially traumatic events, improving communication between the child and caregiver, and teaching the caregiver and child coping strategies and behavioral interventions to decrease acute posttraumatic reactions.

The model has been implemented with children who have been exposed to various PTEs, including sexual abuse, domestic and community violence, motor accidents, animal bites, and other injuries [10,56] but not in the context of war and political violence. CFTSI can be implemented shortly after the exposure to a PTE or in the context of later disclosure of sexual abuse, which can trigger the emergence of post-traumatic reactions. Berkowitz et al., in an RCT comparing CFTSI with a five-session psychoeducational and supportive counseling model, found that children in the CFTSI group presented fewer full and partial PTSD diagnoses in comparison with the control group 3 months following the intervention [10].

Even more importantly, a multi-site meta-analysis studying the efficiency of CFTSI in various centers indicated significant improvement of post-traumatic symptoms in adult caregivers who participated in CFTSI with their children [56]. This is one of the few studies that specifically evaluated the effect of early intervention after a child’s exposure to a PTE on parental symptoms and parental mental health, along with the COPE Intervention study [74], a mental health intervention provided to youth who are critically ill and their mothers, based on psychoeducation and coping. In this study, mothers in the intervention group reported increased maternal functional and emotional coping resulting in better adjustment in the child [74]. These findings are in line with research establishing correlations between the psychopathology of parents and that of children since family environment and parental functioning systematically influence the association between exposure and outcome for children. Moreover, the implication of events that affect their children, can traumatically affect parents themselves which may influence their capacity to efficiently provide their parental role to a child rendered vulnerable after a PTE exposure [56,81]. Parents going through high distress are less capable of displaying a sense of stability and safety to the child, and of supporting the child in progressing [82,83]. When parents are coping well themselves, however, this can facilitate the child’s adjustment after a PTE exposure, through modeling efficient coping skills, maintaining balance through routine and regulation, and instilling self-efficacy and relatedness [45,84]. This emphasizes the importance of interventions to reinforce parental capacities in the aftermath of the child’s exposure to a traumatic event and offer additional support to parents who are highly affected by the exposure of their child to a traumatic event, especially since parents’ abilities to support their children are related to their own distress level [85]. Other members of the family, such as siblings, seem to influence the children’s coping [85] although we did not find interventions in the early post-traumatic period involving siblings.

It has become clear to clinicians and researchers alike that alongside the specific nature of the traumatic events themselves, it is the subjective experience at the time of the traumatic event that determines the range of immediate posttraumatic reactions, as well as the degrees of recovery.

Each child’s exposure and reactions to a PTE are unique and there is no definite answer or explanation when understanding children’s adaptive capacity and resilience [86]. Moreover, qualitative studies exploring children’s own subjective experiences from their own perceptions are scarce [45], even though previous research suggested that youth can be effective and informed partners in the research process [87,88]. The wide range of children’s reactions to PTEs as well as the lack of understanding of children’s own perceptions and experiences in the aftermath of the trauma exposure points to the importance of developing a more thorough assessment of their experiences of coping and adaptation and how they are affected by their social milieu and relationships. Children’s coping abilities depend on the internal (feelings of self-efficiency) and external (e.g., family and social support networks) resources available in their ecological contexts [85,89] and their interaction with their proximal environment: family, school, and neighborhood [85]. Trauma research needs to shift the focus from children’s symptomology to exploring processes allowing children to respond in an adaptive manner within their environmental settings [90].

4.3. Limitations

Only two databases were used to search for articles, due to limited logistic resources. However, for scoping reviews the two databases that should be at least applied are MEDLINE and Embase. We searched PubMed using Mesh terms, which is equivalent to searching MEDLINE and searched Embase while excluding results of MEDLINE to avoid any duplication. A larger review including databases, such as APA Psyinfo is warranted to expand the results, and the small number of included studies emphasize the need for further rigorous studies in the field.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Early psychological interventions combining psychoeducation content for both children and parents on trauma reactions, as well as coping strategies to deal with peritraumatic distress, seem to be efficient in specific settings in preventing the development of enduring posttraumatic stress. Exploring children’s perspectives in this process is crucial, to have a better understanding of their adaptation processes and how they are affected by their social context and family relationships. Children’s abilities to adaptively process a traumatic event are influenced by their developmental stage and the environment in which their development takes place. When we are better able to consider and appreciate the combination of these factors, we are better positioned to offer an effective clinical intervention that can help reduce traumatic stress reactions, prevent PTSD and associated conditions, and decrease suffering and interference with subsequent development.

Author Contributions

H.K. and D.P.-O. conceived the idea and wrote the review protocol. H.K. and O.B. performed the search, selected, and reviewed the papers and drafted the tables. H.K. and O.B. wrote the original draft of the paper. W.E.H., E.C. and D.P.-O. reviewed and edited the first draft and added substantial changes and revisions to the results and discussion. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Youth Violence: Facts at a Glance. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv-datasheet.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.; Amobi, A.; Kress, H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schäfer, I.; Hopchet, M.; Vandamme, N.; Ajdukovic, D.; El-Hage, W.; Egreteau, L.; Javakhishvili, J.D.; Makhashvili, N.; Lampe, A.; Ardino, V.; et al. Trauma and trauma care in Europe. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2018, 9, 1556553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leaning, J.; Guha-Sapir, D. Natural disasters, armed conflict, and public health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1836–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.S.; Shaw, J. Children as victims of war: Current knowledge and future research needs. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1993, 32, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjet, C.; Bromet, E.; Karam, E.G.; Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Ruscio, A.M.; Shahly, V.; Stein, D.J.; Petukhova, M.; Hill, E.; et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the world mental health survey consortium. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brewin, C.R. Risk factor effect sizes in PTSD: What this means for intervention. J. Trauma Dissociation 2005, 6, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenen, K.C.; Ratanatharathorn, A.; Ng, L.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Bromet, E.J.; Stein, D.J.; Karam, E.G.; Meron Ruscio, A.; Benjet, C.; Scott, K.; et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2260–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Koenen, K.C.; Hill, E.D.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 815–830.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkowitz, S.J.; Stover, C.S.; Marans, S.R. The child and family traumatic stress intervention: Secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; Meadows, E.A. Psychosocial treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 48, 449–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahana, S.Y.; Feeny, N.C.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Drotar, D. Posttraumatic stress in youth experiencing illnesses and injuries: An exploratory meta-analysis. Traumatology 2006, 12, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Olsson, C.A.; Skirbekk, V.; Saffery, R.; Wlodek, M.E.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Stonawski, M.; Rasmussen, B.; Spry, E.; Francis, K.; et al. Adolescence and the next generation. Nature 2018, 554, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alisic, E.; Zalta, A.K.; van Wesel, F.; Larsen, S.E.; Hafstad, G.S.; Hassanpour, K.; Smid, G.E. Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 204, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslau, N.; Wilcox, H.C.; Storr, C.L.; Lucia, V.C.; Anthony, J.C. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: A study of youths in urban america. J. Urban Health 2004, 81, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davydow, D.S.; Richardson, L.P.; Zatzick, D.F.; Katon, W.J. Psychiatric morbidity in pediatric critical illness survivors: A comprehensive review of the literature. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010, 164, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, D.W.; Anda, R.F.; Tiemeier, H.; Felitti, V.J.; Edwards, V.J.; Croft, J.B.; Giles, W.H. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappa, C.; Jijon, I. COVID-19 and violence against children: A review of early studies. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P. PTSD as a public mental health priority. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCart, M.R.; Zajac, K.; Kofler, M.J.; Smith, D.W.; Saunders, B.E.; Kilpatrick, D.G. Longitudinal examination of PTSD symptoms and problematic alcohol use as risk factors for adolescent victimization. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2012, 41, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vermeiren, R.; Schwab-Stone, M.; Deboutte, D.; Leckman, P.E.; Ruchkin, V. Violence exposure and substance use in adolescents: Findings from three countries. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruccelli, K.; Davis, J.; Berman, T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 97, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Chapman, D.P.; Williamson, D.F.; Giles, W.H. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA 2001, 286, 3089–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sonu, S.; Post, S.; Feinglass, J. Adverse childhood experiences and the onset of chronic disease in young adulthood. Prev. Med. 2019, 123, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, S.; Garofalo, S.; di Pellegrino, G.; Starita, F. Revaluing the role of vmPFC in the acquisition of pavlovian threat conditioning in humans. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 8491–8500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Harrison, B.J.; Fullana, M.A. Does the human ventromedial prefrontal cortex support fear learning, fear extinction or both? A commentary on subregional contributions. Mol. Psychiatry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdorf, T.B.; Haaker, J.; Kalisch, R. Long-term expression of human contextual fear and extinction memories involves amygdala, hippocampus and ventromedial prefrontal cortex: A reinstatement study in two independent samples. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 1973–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fullana, M.A.; Harrison, B.J.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Vervliet, B.; Cardoner, N.; Àvila-Parcet, A.; Radua, J. Neural signatures of human fear conditioning: An updated and extended meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quirk, G.J.; Milad, M.R. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature 2002, 420, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunsmoor, J.E.; Kroes, M.C.W.; Li, J.; Daw, N.D.; Simpson, H.B.; Phelps, E.A. Role of human ventromedial prefrontal cortex in learning and recall of enhanced extinction. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 3264–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battaglia, S. Neurobiological advances of learned fear in humans. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ Wroc. Med. Univ. 2022, 31, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Gevonden, M.; Shalev, A. Prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma: Current evidence and future directions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Horn, S.R.; Feder, A. Understanding resilience and preventing and treating PTSD. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, L.A.; Sijbrandij, M.; Sinnerton, R.; Lewis, C.; Roberts, N.P.; Bisson, J.I. Pharmacological prevention and early treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eifling, K.; Moy, P. Evidence-based EMS: Psychological first aid during disaster response. What’s the best we can do for those who are suffering mentally? EMS World 2015, 44, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/guidelines_iasc_mental_health_psychosocial_june_2007.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Dieltjens, T.; Moonens, I.; Van Praet, K.; De Buck, E.; Vandekerckhove, P. A systematic literature search on psychological first aid: Lack of evidence to develop guidelines. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, J.M.; Forbes, D. Psychological first aid: Rapid proliferation and the search for evidence. Disaster Health 2014, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruzek, J.I.; Brymer, M.J.; Jacobs, A.K.; Layne, C.M.; Vernberg, E.M.; Watson, P.J. Psychological first aid. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2007, 29, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kearns, M.C.; Ressler, K.J.; Zatzick, D.; Rothbaum, B.O. early interventions for ptsd: A review. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shalev, A.Y.; Ankri, Y.; Israeli-Shalev, Y.; Peleg, T.; Adessky, R.; Freedman, S. Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder by early treatment: Results from the jerusalem trauma outreach and prevention study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, C.M.; Kenardy, J.A.; Hendrikz, J.K. A meta-analysis of risk factors that predict psychopathology following accidental trauma. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2008, 13, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickey, D.; Siddaway, A.P.; Meiser-Stedman, R.; Serpell, L.; Field, A.P. A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vernberg, E.M.; la Greca, A.M.; Silverman, W.K.; Prinstein, M.J. Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after hurricane andrew. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1996, 105, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisner, B.; Paton, D.; Alisic, E.; Eastwood, O.; Shreve, C.; Fordham, M. Communication with children and families about disaster: Reviewing multi-disciplinary literature 2015–2017. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atiyeh, C.; Cunningham, J.N.; Diehl, R.; Duncan, L.; Kliewer, W.; Mejia, R.; Neace, B.; Parrish, K.A.; Taylor, K.; Walker, J.M. Violence exposure and adjustment in inner-city youth: Child and caregiver emotion regulation skill, caregiver-child relationship quality, and neighborhood cohesion as protective factors. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004, 33, 477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Sriskandarajah, V.; Neuner, F.; Catani, C. Parental care protects traumatized sri lankan children from internalizing behavior problems. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howell, K.H.; Barrett-Becker, E.P.; Burnside, A.N.; Wamser-Nanney, R.; Layne, C.M.; Kaplow, J.B. Children facing parental cancer versus parental death: The buffering effects of positive parenting and emotional expression. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildenbrand, A.K.; Kassam-Adams, N.; Barakat, L.P.; Kohser, K.L.; Ciesla, J.A.; Delahanty, D.L.; Fein, J.A.; Ragsdale, L.B.; Marsac, M.L. Posttraumatic stress in children after injury: The role of acute pain and opioid medication use. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2020, 36, e549–e557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, N.R.; Christopher, N.C.; Crow, J.P.; Browne, L.; Ostrowski, S.; Delahanty, D.L. The efficacy of early propranolol administration at reducing PTSD symptoms in pediatric injury patients: A pilot study. J. Trauma. Stress 2010, 23, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, L.; Rosenberg, M.; Sharp, S.; Thomas, C.R.; Humphries, H.F.; Holzer, C.E.; Herndon, D.N.; Meyer, W.J. Does acute propranolol treatment prevent posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in children with burns? J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, G.; Stoddard, F.; Courtney, D.; Cunningham, K.; Chawla, N.; Sheridan, R.; King, D.; King, L. Relationship between acute morphine and the course of PTSD in children with burns. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharp, S.; Thomas, C.; Rosenberg, L.; Rosenberg, M.; Meyer, W. Propranolol does not reduce risk for acute stress disorder in pediatric burn trauma. J. Trauma. 2010, 68, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard, F.J.; Luthra, R.; Sorrentino, E.A.; Saxe, G.N.; Drake, J.; Chang, Y.; Levine, J.B.; Chedekel, D.S.; Sheridan, R.L. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder in burned children. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard, F.J.; Sorrentino, E.A.; Sheridan, R.L.; Tompkins, R.G.; Ceranoglu, T.A.; Saxe, G.; Murphy, J.M.; Drake, J.E.; Ronfeldt, H.; White, G.W.; et al. Preliminary evidence for the effects of morphine on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in one-to four-year-olds with burns. J. Burn Care Res. 2009, 30, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, H.; Putnam, K.; Epstein, C.; Marans, S.; Putnam, F. Child and family traumatic stress intervention (CFTSI) reduces parental posttraumatic stress symptoms: A multi-site meta-analysis (MSMA). Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 92, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uggla, L.; Bonde, L.; Svahn, B.; Remberger, M.; Wrangsjö, B.; Gustafsson, B. Music therapy can lower the heart rates of severely sick children. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pityaratstian, N.; Liamwanich, K.; Ngamsamut, N.; Narkpongphun, A.; Chinajitphant, N.; Burapakajornpong, N.; Thongphitakwong, W.; Khunchit, W.; Weerapakorn, W.; Rojanapornthip, B.; et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for young tsunami victims. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2007, 90, 518. [Google Scholar]

- Jordans, M.J.D.; Komproe, I.H.; Tol, W.A.; Kohrt, B.A.; Luitel, N.P.; Macy, R.D.; De Jong, J.T.V.M. Evaluation of a classroom-based psychosocial intervention in conflict-affected nepal: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, P.; Branham, L.; Shannon, C.; Betancourt, T.S.; Dempster, M.; McMullen, J. A pilot study of a family focused, psychosocial intervention with war-exposed youth at risk of attack and abduction in north-eastern democratic republic of congo. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tol, W.A.; Komproe, I.H.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Vallipuram, A.; Sipsma, H.; Sivayokan, S.; Macy, R.D.; Jong, J.T. Outcomes and moderators of a preventive school-based mental health intervention for children affected by war in sri lanka: A cluster randomized trial. World J. Psychiatry 2012, 11, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tol, W.A.; Komproe, I.H.; Susanty, D.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Macy, R.D.; De Jong Joop, T.V.M. School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in indonesia: A cluster randomized trial. JAMA 2008, 300, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Bioy, A. Early hypnotic intervention after traumatic events in children. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2020, 62, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehnder, D.; Meuli, M.; Landolt, M.A. Effectiveness of a single-session early psychological intervention for children after road traffic accidents: A randomised controlled trial. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2010, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phipps, S.; Peasant, C.; Barrera, M.; Alderfer, M.A.; Huang, Q.; Vannatta, K. Resilience in children undergoing stem cell transplantation: Results of a complementary intervention trial. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e762–e770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stallard, P.; Velleman, R.; Salter, E.; Howse, I.; Yule, W.; Taylor, G. A randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of an early psychological intervention with children involved in road traffic accidents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenardy, J.; Thompson, K.; Le Brocque, R.; Olsson, K. Information–provision intervention for children and their parents following pediatric accidental injury. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenardy, J.A.; Cox, C.M.; Brown, F.L. A web-based early intervention can prevent long-term PTS reactions in children with high initial distress following accidental injury. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, C.M.; Kenardy, J.A.; Hendrikz, J.K. A randomized controlled trial of a web-based early intervention for children and their parents following unintentional injury. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kassam-Adams, N.; Felipe García-España, J.; Marsac, M.L.; Kohser, K.L.; Baxt, C.; Nance, M.; Winston, F. A pilot randomized controlled trial assessing secondary prevention of traumatic stress integrated into pediatric trauma care. J. Trauma. Stress 2011, 24, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsac, M.L.; Hildenbrand, A.K.; Kohser, K.L.; Winston, F.K.; Li, Y.; Kassam-Adams, N. Preventing posttraumatic stress following pediatric injury: A randomized controlled trial of a web-based psycho-educational intervention for parents. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haag, A.; Landolt, M.A.; Kenardy, J.A.; Schiestl, C.M.; Kimble, R.M.; De Young, A.C. Preventive intervention for trauma reactions in young injured children: Results of a multi-site randomised controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 6, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam-Adams, N.; Marsac, M.L.; Kohser, K.L.; Kenardy, J.; March, S.; Winston, F.K. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a novel web-based intervention to prevent posttraumatic stress in children following medical events. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Alpert-Gillis, L.; Feinstein, N.F.; Crean, H.F.; Johnson, J.; Fairbanks, E.; Small, L.; Rubenstein, J.; Slota, M.; Corbo-Richert, B. Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: Program effects on the mental Health/Coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics 2004, 113, e597–e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Battaglia, S.; Sciamanna, G.; Tortora, F.; Laricchiuta, D. Memories are not written in stone: Re-writing fear memories by means of non-invasive brain stimulation and optogenetic manipulations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Battaglia, S.; Avenanti, A.; di Pellegrino, G. Don’t hurt me no more: State-dependent transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of specific phobia. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 286, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothgassner, O.D.; Pellegrini, M.; Goreis, A.; Giordano, V.; Edobor, J.; Fischer, S.; Plener, P.L.; Huscsava, M.M. Hydrocortisone administration for reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 126, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, T.; Stein, D.J.; Ipser, J.C.; Amos, T. Pharmacological interventions for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Libr. 2014, 2014, CD006239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silove, D. The ADAPT model: A conceptual framework for mental health and psychosocial programming in post conflict settings. Intervention 2013, 11, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ommeren, M.; Saxena, S.; Saraceno, B. Mental and social health during and after acute emergencies: Emerging consensus? Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, T.; Fabre, A. Maternal response to the disclosure of child sexual abuse: Systematic review and critical analysis of the literature. Issues Child Abus. Accusations 2014, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, D.M.; Weems, C.F. Family and peer social support and their links to psychological distress among hurricane-exposed minority youth. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, C.E.; Elkins, R.M.; Carpenter, A.L.; Chou, T.; Green, J.G.; Comer, J.S. Caregiver distress, shared traumatic exposure, and child adjustment among area youth following the 2013 boston marathon bombing. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 167, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacPhee, D.; Lunkenheimer, E.; Riggs, N. Resilience as regulation of developmental and family processes. Fam. Relat. 2015, 64, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mooney, M. Getting through: Children’s effective coping and adaptation in the context of the canterbury, New Zealand, earthquakes of 2010–2012. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma. Stud. 2017, 21, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca, A.M.; Lai, B.S.; Joormann, J.; Auslander, B.B.; Short, M.A. Children’s risk and resilience following a natural disaster: Genetic vulnerability, posttraumatic stress, and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, L.; MacDougall, C.; Mutch, C.; O’Connor, P. Child citizenship in disaster risk and affected en-vironments. In Disaster Resilience: An Integrated Approach, 2nd ed.; Paton, D., Johnston, D., Eds.; Charles Thomas Publishers: Springfield, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.S.; Osofsky, J.D.; Osofsky, H.J.; Weems, C.F.; Hansel, T.C.; Fassnacht, G.M. Perceptions of trauma and loss among children and adolescents exposed to disasters a mixed-methods study. Curr. Psychol. 2015, 34, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamwey, M.; Allen, L.; Hay, M.; Varpio, L. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of human development: Applications for health professions education. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Noffsinger, M.A.; Wind, L.H.; Allen, J.R. Children’s coping in the context of disasters and terrorism. J. Loss Trauma 2014, 19, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).