Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Field applications of low-cost sensors in China are heavily skewed towards air and noise pollution, leaving critical areas like soil and biological contamination largely unexplored.

- The current research is predominantly limited by small-scale studies, short durations, and insufficient validation of sensor reliability.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The identified gaps underscore an urgent need to extend the application of low-cost sensors to under-investigated environmental domains, which is essential for comprehensive multi-pollutant exposure assessment.

- This review provides a critical framework for future research, highlighting that overcoming challenges in sensor accuracy, portability, and data integrity is fundamental to achieving large-scale, reliable monitoring.

Abstract

Accurate environmental monitoring in outdoor and indoor settings is critical for exposure assessment in environmental and public health research. Conventional methods, predominantly relying on high-end instruments or laboratory analyses, face limitations in real-world applications due to their high cost and inflexibility. Recent advances in low-cost sensor technologies have enabled more adaptable monitoring. This study systematically reviews research utilizing low-cost sensors for environmental monitoring in real-world settings across China. A literature search was performed using the Web of Science database, resulting in the inclusion of 43 eligible studies out of 31,003 initially identified records. These studies primarily investigated air pollution (17 studies), noise (14), light (7), and water pollution (5). Results reveal that air and noise pollution were the most extensively examined factors. Nevertheless, the reviewed studies exhibited notable shortcomings, including limited geographical/thematic coverage, inadequate reliability validation, small sample sizes (typically under 100 participants), and short durations (often under one month). This review discusses these challenges and suggests future research directions. By synthesizing current practices and identifying gaps, this work offers valuable insights to guide the design of future sensor-based environmental monitoring projects and inform the selection of suitable sensors.

1. Introduction

Despite general improvements in environmental quality over the past few years, excessive environmental exposure remains a considerable risk factor for the burden of disease in present-day China [1]. For instance, in 2013, only 3 out of 74 cities with ground-level air quality monitoring stations met China’s Ambient Air Quality Standard (GB 3095-2012). In contrast, this number increased to 222 out of 339 cities meeting the standard by 2024. Regarding water quality, the proportion of major river water sections categorized as “good” (Class I-III) and “poor” (inferior to Class V) was 71.7% and 9.0%, respectively, in 2013. By 2024, the proportion of “good” waters had risen to 92.4%, while that of “poor” waters had fallen to 0.3% [1]. Nevertheless, according to data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), environmental and occupational risks were responsible for approximately 3.4 million deaths and 76.4 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in China in 2021, accounting for approximately 28.7% of all deaths and 19.0% of all DALYs attributable to all risk factors [2].

Environmental monitoring across diverse outdoor and indoor settings is fundamental for accurate exposure assessment in environmental and public health research. Conventional approaches typically rely on fixed-site monitoring stations or samplers deployed at static locations [3,4,5,6,7,8]. These conventional methods often depend on high-end, stationary instruments or offline laboratory-based chemical analysis. For example, one study investigating the impact of different filters in home and office ventilation systems on adult cardiorespiratory function measured ambient PM2.5 and ozone levels at a nearby government monitoring station, while indoor levels were assessed using laboratory-grade instruments (e.g., TSI AM 510 SidePak for PM2.5 and 2B Tech Model 205 for ozone). Additionally, indoor volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and carbonyls were quantified through active sampling followed by mass spectrometric analysis [3]. However, the complexity and high cost of these conventional methods limit their mobility and scalability. Moreover, these approaches are often impractical for measuring accurate and continuous personal environmental exposures.

The rapid advancement of sensor technology in recent years has facilitated the development of numerous low-cost monitors and devices for environmental monitoring. Several well-known manufacturers, such as Plantower, Shinyei, Dylos, PurpleAir, MetOne, and Alphasense, produce such low-cost sensors and monitors [9]. The application of these devices has expanded globally to capture critical environmental events and complement regulatory networks. For instance, in Mexico, EMGA stations were deployed to record rapid increases in PM2.5 during fireworks celebrations [10]. In densely populated regions like Delhi, India, researchers have validated low-cost sensors for real-time PM10 monitoring, demonstrating their utility in resource-constrained environments [11]. Similarly, calibrated PurpleAir sensors were used to estimate wildfire smoke levels in California [12]. Beyond these ambient monitoring efforts, many recent studies have employed these portable monitors for personal exposure assessment. Chatzidiakou et al. used personal air quality monitors integrating multiple miniaturized sensors (e.g., for particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and ozone) to improve the estimation of individual exposure doses [13]. Ma et al. used portable noise sensors to continuously measure the noise exposure levels of subjects [14]. Liu et al. used wearable ultraviolet radiation (UVR) sensors to assess the UVR exposure level of college students and pupils [15]. Compared to conventional devices, these mobile monitors are typically low-cost, compact, lightweight, and energy-efficient, enabling the collection of data with high spatiotemporal resolution. It is important to note that the definition of “low-cost” is relative and varies depending on the user and specific application. In this review, we adopt the definition outlined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and clarified by Morawska et al. [16], which refers to monitors or devices costing less than USD 2500.

Several previous reviews have examined the development and applications of portable low-cost sensors in environmental monitoring [16,17,18,19,20]. For example, Xu et al. reviewed the design of wireless sensor networks and their application in marine environmental monitoring [19]. Similarly, Morawska et al. focused on the validation, deployment, and data accessibility of low-cost sensors, alongside their applications [16]. Additionally, Salamone et al. systematically reviewed wearable devices for environmental monitoring in the built environment, with a focus on sensor development and limitations [17]. In summary, while previous reviews have provided valuable insights, they predominantly concentrate on the sensors themselves (e.g., design, validation) and often overlook the diversity of their real-world applications. Although a 2017 review explored the applications of miniaturized monitors for air pollution monitoring [20], it does not encompass the numerous relevant studies published since then. Moreover, its scope was limited to air pollutants, excluding other critical environmental factors such as water and soil pollution, microbes, noise, and light.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of studies that employ portable low-cost sensors in real-world environmental monitoring campaigns. It encompasses a wide range of environmental factors (e.g., air, water, and soil pollution; microbes; noise; and light) across diverse settings (both outdoor and indoor). Therefore, this review aims to present a holistic picture of current research employing low-cost sensors for environmental monitoring and to offer guidance for the design of future studies and the selection of appropriate sensors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Search Strategy

Following a systematic approach adapted from a previous study [21], we conducted a literature search in the Web of Science for articles published between 1 January 1990 and 31 July 2025, focusing exclusively on studies conducted in China. The detailed search queries are provided in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials). In brief, the search strategy combined terms related to general “environmental factors” and specific factors of interest (i.e., air, water, and soil pollution; microbes; noise; and light) with keywords pertaining to “wearable”, “portable”, or “low-cost” sensors. All keywords and their relevant synonyms were searched within the topic field, which encompasses titles, abstracts, and author keywords. Ideally, the search strategy could be refined by incorporating terms like “field test” to better target real-world monitoring studies. However, no consistent terminology exists for “field testing” in the literature, as such studies may be conducted across diverse settings. Therefore, we initially retrieved a broader set of articles and manually screened them for eligibility based on the predefined criteria. Additionally, we performed a manual review of the reference lists within the included articles to identify and incorporate any additional studies that satisfied the eligibility criteria.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria were defined as follows: (1) peer-reviewed original research articles with full text available; (2) articles published in the English language.; (3) studies conducting field tests or real-world monitoring campaigns; (4) studies carried out in China. Given the review’s focus on practical applications, studies primarily concerned with sensor development or laboratory-based performance evaluation were excluded. Furthermore, only studies using portable and low-cost sensors, as defined above, were selected. For studies employing Do-it-Yourself (DIY) sensor assemblies, the total cost of the core sensor components was required to be under USD 2500 to align with the low-cost definition.

The literature screening process involved multiple stages. First, one reviewer screened the titles and abstracts of all identified records against the eligibility criteria. Subsequently, a second reviewer independently assessed the full texts of the remaining articles. Finally, all reviewers collectively examined the final shortlisted literature to ensure consistency and quality. Any disagreements arising during the screening process were resolved through consensus discussion.

2.3. Study Inclusion

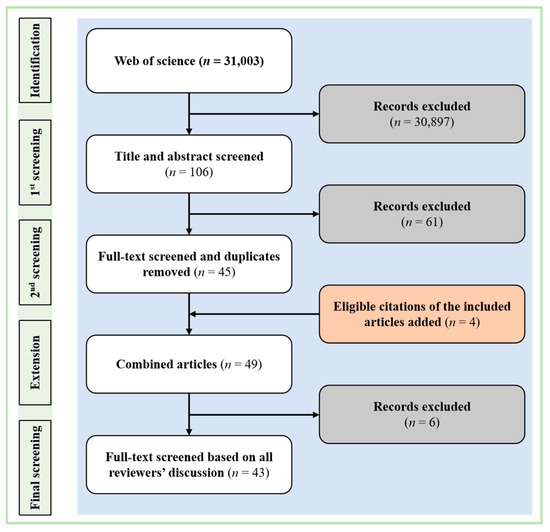

The study selection process is summarized in Figure 1. The initial database search yielded 31,003 records. Following the initial screening of titles and abstracts, 106 records were retained for full-text review. After a full-text assessment by a second independent reviewer, which led to the exclusion of non-qualifying and duplicate records, 45 articles remained. Additionally, a manual search of the reference lists from these 45 articles identified 4 further eligible publications, resulting in a total of 49 articles. A final collective review by all authors led to the exclusion of 6 additional articles. Consequently, a final total of 43 studies were included.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study inclusion: The diagram details the sequential phases of identification, screening, and eligibility assessment. Initial records were retrieved from the Web of Science database (n = 31,003). The screening process applied specific inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed original research conducted in China utilizing portable low-cost sensors for field monitoring. Key exclusion criteria were applied to remove studies focused solely on sensor development, laboratory-based performance evaluation without field ap-plication, or those not written in English, resulting in a final set of 43 eligible studies.

2.4. Analysis Strategy

We summarized the 43 included studies based on the environmental factor category of each study. Specifically, the studies were categorized into four groups, i.e., air pollution, noise, light and water pollution. For each subgroup, eligible studies were summarized in a table containing information on specific environmental factors, scenario, location, period of field tests, subjects, and sensor models. Furthermore, we discussed the challenges and opportunities in each subgroup. The review focused more on summarizing the methods of the reviewed studies, especially in the aspect of sensor application, rather than the results or conclusions. Consequently, the analysis aims to help guide future sensor-based studies on how to select low-cost environmental sensors and design field-based projects.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

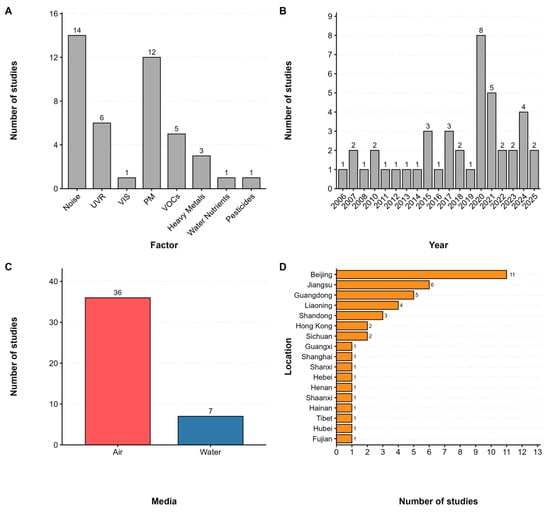

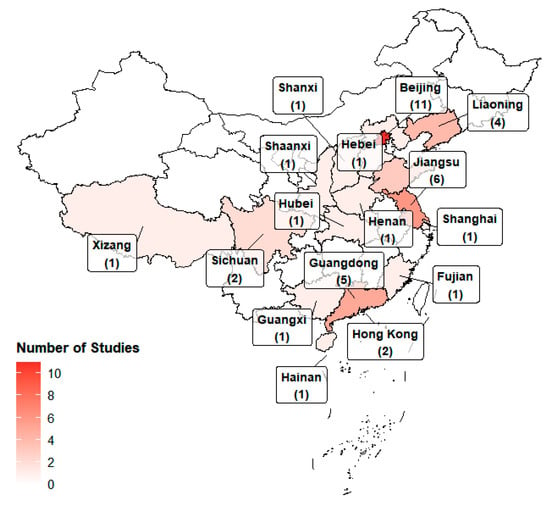

As summarized in Figure 2 and Table S3 (Supplementary Materials), the 43 studies include 17 on air pollution, 14 on noise, 7 on light, and 5 on water pollution. No eligible studies on soil pollution or microbes were found. Among the 17 studies on air pollution, twelve examined particulate matter (PM), and five examined total volatile organic compounds (TVOCs). No eligible studies were found for ozone, ammonia, radon, sulfur oxides, or a specific VOC. Regarding light, six studies measured UVR and one investigated visible light (VIS). No studies addressed electromagnetic or infrared radiation. In terms of environmental media, most studies (36 out of 43) focused on the atmospheric environment, with only seven addressing the aquatic environment. Thirty-three studies were published in the past ten years, while 22 were published in the past five years, indicating growing research interest in this field. Geographically, the studies were primarily conducted in Beijing (eleven papers) and Jiangsu (six papers), with the others in Liaoning, Shanghai, Guangdong, etc. The geographic distribution is visualized in Figure 3. As shown in the map, research efforts are heavily skewed towards economically developed regions in Eastern China (e.g., Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, Yangtze River Delta and Guangdong province), while vast areas in Western and Central China remain largely under-investigated.

Figure 2.

Overview of the literature characteristics: (A) The distribution of studies focused on different environmental factors; (B) The distribution of studies across different publication years; (C) The distribution of studies across different environmental media; (D) Geographical distribution of the studies.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of the 43 reviewed studies across China.

3.2. Air Pollution

In this section, we found 12 eligible studies on PM, and 5 on VOC, as summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

One of the most significant threats in this generation is air pollution, impacting not only climate change but also public and individual health. Among them, PM, particles of variable but minimal diameter, penetrate the respiratory system via inhalation, causing respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and so on [22,23,24]. Furthermore, nitrogen oxide, sulfur dioxide, VOCs, dioxins, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are all considered air pollutants harmful to humans [25]. As mentioned above, diseases from the above substances cause respiratory problems such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma and lung cancer, and cardiovascular events [26].

Therefore, our primary goal is to find accurate and reliable detection tools. Traditional testing methods, while ensuring accuracy, often have the disadvantage of being expensive or inconvenient to carry. Low-cost, portable detection equipment is gradually maturing for application. The following paper will discuss the previous application of low-cost sensors from the perspective of several contaminants.

3.2.1. Particulate Matter

PM2.5 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm) is a representative pollutant in China, with prolonged atmospheric residence times that significantly impact air quality and visibility. China’s annual average PM2.5 concentrations historically exceed those of many developed nations [27]. Epidemiological evidence firmly links PM2.5 exposure to increased risks of respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [28,29,30,31,32,33]. PM2.5 monitoring is commonly categorized into indoor and outdoor environments, which exhibit distinct spatiotemporal patterns and health implications [26]. This section summarizes 12 studies on the application of portable low-cost sensors in China, which are shown in Table 1. To further illustrate the temporal characteristics of these studies, Figure S1 visualizes their timeline and duration stratified by monitoring scenarios.

Before detailing specific applications, it is essential to characterize the technology underpinning these studies. The majority of the reviewed campaigns employed commercial sensors (e.g., Plantower PMS series, Shinyei PPD, Nova SDS) that rely on the light scattering principle (specifically Mie scattering). While cost-effective, these sensors rely on assumed particle density profiles to convert optical signals into mass concentrations, which creates inherent challenges in selectivity. Quantitatively, the lower detection limit is typically around 1–5 µg/m3, with a dynamic range usually extending up to 500 or 1000 µg/m3, making them generally suitable for China’s ambient levels but less precise for clean environments [34,35]. A critical operational limitation is hygroscopic growth: at moderate humidity (50–80%), particles absorb water and scatter more light, potentially causing concentration to vary by as much as 20–50% if not algorithmically corrected [36]. Furthermore, regarding particle size discrimination, these optical sensors typically struggle to detect ultrafine particles (<0.1 μm)—which contribute little to mass but significantly to number concentration—thereby limiting their utility for assessing exposure to combustion-derived nanoparticles [37].

Despite these limitations, the flexibility of low-cost sensors enables novel approaches to outdoor air pollution monitoring. Traffic is a major source of outdoor PM2.5. Liu et al. demonstrated the use of low-cost sensors to monitor ambient PM and estimate traffic-related emission factors [38]. Similarly, another study by Liu et al. deployed a bicycle-based mobile monitoring system to assess near-road air quality [39]. Complementing fixed stations, which are costly to maintain and deploy densely, low-cost sensors can enhance spatial resolution. For instance, Chao et al. showed that integrating low-cost sensor networks with fixed stations significantly improves the spatiotemporal resolution of PM data, enabling more detailed pollution mapping and source identification [40]. Other studies have further exploited this spatial refinement at various scales. Wang et al. deployed sensors across a university campus, identifying distinct spatiotemporal variations and lower PM2.5 levels compared to the urban background [41]. In a city-wide application, Liang et al. utilized a mobile network of sensors on taxis, coupled with big-data analytics, to map fine-scale pollution patterns and identify major emission sources [42]. Focusing directly on sources, Li et al. used a portable system to characterize ultrafine particle emissions from diesel trucks, quantifying significant reductions associated with improved emission standards and control technologies [43]. Gao et al. evaluated a low-cost PM sensor against reference instruments in a high-concentration urban setting in Xi’an [44]. Similarly, Bai et al. conducted a long-term field evaluation of a low-cost PM2.5 sensor in Nanjing [45]. Their findings, consistent with other studies, indicate that with proper calibration, low-cost sensors can achieve acceptable accuracy for ambient PM2.5 measurement.

In contrast to outdoor environments, indoor air pollution exhibits distinct spatiotemporal patterns and source profiles, which have been less quantified despite significant health implications. Shen et al. employed low-cost sensors in a Beijing apartment to quantify indoor PM2.5 levels and identify major sources [46]. Their findings identified outdoor infiltration and cooking as the primary PM2.5 sources, with cooking being a more dominant contributor. Indoor PM2.5 concentrations correlated with, but were generally lower than, ambient levels. In rural China, household air pollution from solid fuel combustion poses a severe health risk. Men et al. conducted a four-month monitoring campaign using low-cost sensors to track indoor PM2.5 from coal burning in rural households. They analyzed temporal dynamics, indoor–outdoor relationships, and quantified the contribution of indoor sources [47]. Together, these studies demonstrate that low-cost sensors are a valuable tool for characterizing indoor exposure with high spatiotemporal resolution, crucial for identifying key sources and exposure patterns.

Beyond ambient concentration, personal exposure is more directly relevant to health. Chatzidiakou et al. deployed multi-pollutant personal sensors to 251 participants in Beijing to measure individual exposure [13]. Similarly, Yang and Zhao used a wearable monitoring system to demonstrate substantial discrepancies between personal PM2.5 exposure and ambient station measurements among college students [48]. These studies underscore the potential of low-cost sensors for quantifying truly personal exposure, which often differs from ambient concentrations.

Table 1.

Studies focusing on PM.

Table 1.

Studies focusing on PM.

| Study | Location (China) | Scenario | Period | Subject | Exposure Measurement | Number of Records |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [38] | Beijing | Traffic | 2018 | 9 locations | PMS1003, BAM-1020, EC9830 | 1 week for each subject |

| [39] | Changzhou, Jiangsu | Traffic | 2015 | n. a | Shinyei PPD42NS TGS 2201 | Few days |

| [40] | Xinxiang, Henan | Outdoor | 2017 | 144 locations | XHAQSN-808 model | 1 year for each subject |

| [41] | Beijing | Outdoor | 2023 | 5 locations | CGDN1 | 35 days for each subject |

| [42] | Rizhao, Shandong | Traffic | 2019–2020 | 102 taxis | SDS019–25 | 12 months for each taxi |

| [43] | Guangzhou, Guangdong | Traffic | 2023 | 10 trucks | ELPI (Dekati, Finland) | 33 km for each truck |

| [44] | Xi’an, Shaanxi | Outdoor | 2013 | 8 locations | Shinyei PPD42NS | 7 days for each location |

| [45] | Nanjing, Jiangsu | Outdoor | 2015–2017 | 1 location | Shinyei PPD42NS BAM-1020 | 2 years for the location |

| [46] | Beijing | Indoor | 2020 | 15 indoor sites | PM-Model-II | 10 days for each subject |

| [47] | Hebei | Indoor | 2021 | 70 rural homes | Model 5030 Synchronized Hybrid Ambient Realtime Particulate Monitor | 4 months for each subject |

| [13] | Beijing | Outdoor | 2016 | 251 participants | PAM | 1 month for each participant |

| [48] | Beijing | Indoor | 2023 | 96 participants | PMS7003 | 2 days for each participant |

3.2.2. VOCs

VOCs are a broad group of carbon-based chemicals that evaporate easily at room temperature [49]. In the context of low-cost sensing, these are often reported as specific compounds (e.g., benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene, collectively known as BTEX) or as TVOC, which represents the aggregate concentration typically measured in parts per billion (ppb) or micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3). Typical TVOC baseline levels in non-industrial indoor environments generally range from 50 to several hundred ppb, whereas outdoor background levels are usually lower, though traffic emissions can cause significant local spikes [50]. Many VOCs are recognized as human carcinogens [51]. They are common indoor air pollutants with documented short- and long-term adverse health effects. Short-term exposure can cause irritation to the eyes, nose, and throat, while chronic exposure is linked to systemic toxic effects [52]. These significant health risks underscore the urgent need for accurate, portable, and intelligent monitoring methods. Two primary low-cost sensing principles are widely used: Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) and Photoionization Detectors (PID). MOS sensors are dominant in low-cost applications due to their affordability, yet they suffer from significant selectivity limitations; they react non-specifically to various reducing gases (e.g., alcohols, CO) and are prone to baseline drift caused by humidity and temperature [53]. Their detection limit typically ranges from 0.1 to 1 ppm, which is often insufficient for monitoring trace-level ambient VOCs in non-industrial settings. In contrast, PID sensors offer superior sensitivity (down to 1–10 ppb) and faster response time [54]. However, they remain limited by the ionization potential of the UV lamp (typically 10.6 eV), meaning they cannot distinguish between specific compounds in a complex mixture without upstream separation steps. Navigating these technological characteristics, this section reviews 5 studies that utilized portable low-cost sensors for VOC monitoring in China, which are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies focusing on VOCs.

Table 2.

Studies focusing on VOCs.

| Study | Location (China) | Scenario | Period | Subject | Exposure Measurement | Number of Records |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | Guangdong | Ambient air monitoring | 2019 | VOCs in air | Photoionization detector (PID) | Multiple ambient air samples |

| [56] | Guangdong | Food safety | 2022 | Vegetable samples | Screen-printed electrode (SPE) aerometric sensor | 53 records (one per vegetable sample) |

| [57] | Hubei | Vehicle emission monitoring | 2023 | Gasoline and diesel vehicles | Portable emission measurement system (PEMS) | Multiple vehicles |

| [58] | Beijing | Artwork preservation | 2017 | Formaldehyde in artworks | Colorimetric sensor (Spectrophon, Rehovot, Israel) | Multiple monitoring tests |

| [59] | Chengdu, Sichuan | Multiple detection | 2011 | Samples | Dual-channel optical sensor | 20 types of VOCs |

Traditional VOC analysis often requires offline sample collection and laboratory processing, which is time-consuming. Low-cost portable sensors offer a solution for real-time, on-site detection. Pang et al. integrated a commercial low-power photoionization detector (PID) into a portable, low-energy gas chromatography (GC) system for ambient hydrocarbon-like VOC analysis [55]. It was used for detecting hydrocarbon-like VOCs in ambient air. Zhang et al. employed a low-cost handheld detector to successfully identify formaldehyde contamination in 53 vegetable samples [56]. Similarly, Niu et al. used a portable system with low-cost VOC sensors for real-time vehicle exhaust monitoring, effectively capturing compositional variations under different driving conditions [57]. These field-based applications demonstrate the capability of low-cost VOC sensors for accurate real-time monitoring in diverse settings.

The connectivity of low-cost sensors (e.g., via Bluetooth or Wi-Fi) enables the creation of large-scale networks and intelligent data platforms. Formaldehyde, a common and concerning VOC, has garnered increasing attention. Real-time data collection and intelligent platforms for formaldehyde detection could significantly benefit industries such as interior decoration and construction. Some researchers have developed smartphone-connected, low-cost sensors for formaldehyde detection. For instance, Zilberstein et al. developed an intelligent platform using a low-cost formaldehyde sensor, which transmitted real-time data to a smartphone via Bluetooth [58]. This system was deployed to monitor formaldehyde levels near artworks in Beijing’s Summer Palace. The sensor data showed strong agreement with commercial devices, validating their reliability. This approach presents a promising strategy for future large-scale data collection and sharing.

Beyond single-analyte devices, multi-analyte sensors capable of simultaneous detection have also been developed. Such multi-analyte sensors can significantly improve monitoring efficiency. Hu et al. developed a novel dual-channel sensor based on surface photovoltage (SPV) and photoluminescence (PL), which could identify 20 different volatile compounds under UV induction [59]. The sensor also successfully distinguished between complex mixtures like wine, liquor, and vinegar. This work points to a promising direction for future research in multi-analyte sensing.

3.3. Noise Pollution

Noise, defined as “unwanted sound”, is a significant environmental pollutant with substantial adverse effects on human health. The hazards can be broadly classified into two categories: auditory and non-auditory effects. Auditory effects primarily involve noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) [60]. According to the 2010 Global Burden of Disease [61], 13 billion people are affected by hearing loss, and investigators rated hearing loss as the 13th most significant contributor to the global number of years lived with disability (YLD) (19.9 million years, 2.6% of the total). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 10% of the global population is exposed to sound pressure levels capable of causing NIHL. Hearing loss in about half of these individuals is attributable to exposure to intense noise [62]. Non-auditory effects encompass a wider range of health issues, including annoyance, sleep disturbance, impaired cognitive performance, and cardiovascular, endocrine, and psychiatric disorders [60,63]. According to WHO [64], DALYs due to environmental noise in EU member states and other Western European countries are 903,000 for sleep disturbance, 587,000 for annoyance, 61,000 for ischemic heart disease, 45,000 for cognitive impairment in children, and 22,000 for tinnitus. This substantial public health burden underscores the necessity for effective monitoring and exposure assessment. To meet this demand, portable sound level meters and personal dosimeters have been widely adopted.

Technologically, the devices reviewed in this section (e.g., SLM-25, AWA5610) typically rely on electret condenser microphones. Unlike studio-grade equipment, these portable sensors are designed for field portability, generally operating within a dynamic range of 30–130 dB. While professional models (e.g., Aihua) offer higher precision, the lower-cost consumer-grade units often employed in citizen science face limitations such as a relatively high noise floor (>30 dBA) and potential sensitivity drift over time. With these operational characteristics in mind, this section reviews 14 studies employing such devices for noise monitoring in China, which are shown in Table 3. The studies involved occupational (4 studies), daily life (5), industrial plant (2), traffic (1), restaurant (1), and built environment (1) scenarios. Based on deployment mode, the studies are categorized as either “carry-on” (personal) or “fixed location”. Carry-on devices enable more accurate assessment of personal noise exposure. For instance, a series of studies used portable sensors (e.g., SLM-25) co-located with GPS smartphones to collect real-time, individual-level noise exposure and spatiotemporal trajectory data, analyzing noise levels across different activities [14,65,66,67,68]. Fixed location deployments, conversely, are used to characterize site-specific noise levels. For example, Wang et al. monitored noise levels across 23 operating rooms in a tertiary hospital [69]. Other monitored sites included textile factories, restaurants, and areas surrounding high-speed trains [70,71,72,73,74]. Among the studies, the subjects ranged from 43–659, and the monitoring periods ranged from hours to two days.

Table 3.

Studies focusing on noise pollution.

3.4. Light Pollution

3.4.1. Ultraviolet Radiation

Human exposure to UVR is a well-established cause of adverse health effects, including skin cancer, cataracts, pterygium, and immunosuppression [15,78]. Skin cancers are among the most common malignancies globally, with over one million new cases diagnosed annually [79]. In the United States alone, they account for nearly 15,000 deaths and over $3 billion in annual medical costs [80]. UVR is estimated to be a causative factor in approximately 65% of melanoma cases and 90% of non-melanoma skin cancers [80]. While skin cancer risk varies by skin phenotype, UVR-induced eye diseases, such as cataracts, represent a universal health concern. Cataracts are a leading cause of blindness worldwide, responsible for over 16 million cases. Ocular exposure to UVR is a significant risk factor for developing both cataracts and pterygium [78].

From a sensing standpoint, the UV monitors deployed in these studies (e.g., PD204 series) generally employ photodiodes paired with optical filters to isolate specific UVA or UVB bands. Unlike broad-band radiometers, these low-cost sensors often face challenges in spectral mismatch, where the sensor’s sensitivity curve does not perfectly align with the erythemal action spectrum (human skin sensitivity) [81]. Furthermore, accurate measurement requires proper cosine correction to account for light arriving from different angles, a feature sometimes compromised in miniaturized wearable designs.

With these technological characteristics in context, this subsection reviews applications of UVR sensors in China, which are shown in Table 4. The six eligible studies were divided into two categories: five measured personal UVR exposure doses, and one monitored ambient UVR levels. One study assessed the seasonal variation in UVR exposure doses among 62 students in Shenyang [15]. The remaining four studies, from the same research group, employed manikins to quantify ocular UVR exposure doses [78,82,83,84]. The single study in the second category examined diurnal and seasonal variations in ambient UVR at the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau [85]. Although portable sensors were used in all studies, the deployment strategy varied. Most studies involved fixed-point monitoring (e.g., sensors mounted on manikin eyes) rather than wearable deployment on participants. Only one study employed a wearable approach, positioning sensors on participants’ upper arms [15]. The studies utilized sensors with different spectral sensitivities: SUB-T type sensors measured broad-spectrum UVA and UVB, while PD204A and PD204B sensors were specific to UVA and UVB, respectively. Monitoring durations across these studies ranged from several days to years.

Table 4.

Studies focusing on light pollution.

3.4.2. Visible Light

Inappropriate illumination levels—both excessive and insufficient—have been documented to negatively affect human physiology and comfort [86,87]. Only one eligible study investigating visible light was identified, the details of which are included in Table 4.

Tu et al. used portable sensors to investigate human responses to different illumination levels and CO2 concentrations within an underground shelter environment [86]. Their study involved 24 male participants, each undergoing two 3.5-h exposure sessions in a basement setting. Illumination levels were continuously monitored, while questionnaires were administered to assess subjective thermal responses and acute health symptoms.

3.5. Water Pollution

Water is an essential resource, yet many regions in China face significant threats from water pollution [88]. Pollutants such as heavy metals and pesticides pose direct and indirect risks to human health and ecosystem integrity. Low-cost sensors enable the development of portable platforms for real-time, multi-analyte water quality monitoring. This section reviews 5 studies on the application of portable low-cost sensors for water quality monitoring in China, which are shown in Table 5.

Regarding detection principles, the reviewed studies utilize diverse approaches tailored to specific analytes, primarily falling into two categories: optical methods and electrochemical sensing. While optical methods offer high sensitivity, they are susceptible to turbidity interference in complex water matrices [89]. Electrochemical sensors provide rapid responses but often struggle with electrode fouling during continuous immersion [90]. Building upon these principles, researchers have developed innovative platforms for automation. For instance, building upon colorimetric analysis, researchers have developed low-cost platforms for the automated, on-site detection of phosphate and nitrite. While phosphate is an essential agricultural nutrient, elevated concentrations (e.g., >0.2 mg/L) can cause eutrophication, severely impacting aquatic ecosystems [91]. Nitrite is highly toxic to aquatic biota and is a potential human carcinogen. To address these needs, Lin et al. developed a low-cost sensor for the automated, on-site monitoring of phosphate and nitrite in agricultural waters [92]. The device utilizes multiple reagents for sequential colorimetric assays, enabling high-throughput, automated screening of multiple water samples in the field. Low-cost optical sensors are also being advanced for the rapid field monitoring of heavy metals. For instance, Chang et al. developed a portable system integrating a novel CMC-MOF membrane with a handheld fluorescence spectrometer, achieving sensitive on-site detection of trace Cr (VI) in groundwater (detection limit: 3.72 ppb) [93].

Visual detection methods offer the distinct advantage of user-friendliness, enabling application by non-specialists. This approach facilitates cost-effective, principle-based optical detection of diverse contaminants, such as the herbicide trifluralin. Excessive trifluralin exposure is associated with adverse health effects including hepatorenal toxicity, allergic reactions, and immunotoxicity [94]. To address this, Farshchi et al. developed a wearable electrochemical glove sensor using conductive silver nano-inks for in-situ monitoring of trifluralin residues on various surfaces [95]. Similarly, Chen et al. designed a glove-based sensor incorporating fluorescent carbon dots from cyanobacteria for the visual detection of Pb2+ in water via fluorescence quenching [96]. Visual detection strategies have also been applied to mercury. Li et al. developed a low-cost test strip based on filter paper for the visual, immediate, and quantitative detection of Hg2+ in water [97]. This sensor demonstrated high analytical performance for detecting Hg2+ in diverse matrices, including water, seafood, and human urine. Collectively, these studies highlight the potential of low-cost sensors as powerful tools for rapid, real-time, and portable detection of water pollution.

Table 5.

Studies focusing on water pollution.

Table 5.

Studies focusing on water pollution.

| Study | Location (China) | Scenario | Period | Subject | Exposure Measurement | Number of Records |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [92] | Xiamen, Fujian | Agriculture water monitoring | 2018 | Agricultural water samples | Low-cost automatic colorimetric sensor | Multiple field samples |

| [93] | Guangxi | Water pollution | 2024 | Groundwater samples from contaminated sites | Portable laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) system with CMC–MOF membrane probe | 3 types of groundwater samples |

| [95] | Nanjing, Jiangsu | Environmental pollution monitoring | 2021 | Trifluralin residues on various substrates | Wearable glove electrochemical sensor | Multiple samples |

| [96] | Jiangsu | Water pollution | 2023 | Different water samples | Wearable glove sensor | 3 types of water samples |

| [97] | Shandong | Environmental pollution monitoring | 2020 | Different samples | Low-cost fluorescent probe (2TS) | Multiple samples from each matrix |

4. Discussion

This review has identified several overarching limitations in the current body of research, indicating that the application of portable low-cost sensors in large-scale environmental monitoring still faces substantial hurdles. This section critically discusses these challenges, focusing on the scope of environmental factors monitored, sensor shortcomings, and the study scale. Subsequently, we propose promising future research directions to address these gaps.

4.1. Scope of Environmental Factors Monitored

The reviewed studies demonstrate a pronounced imbalance in the environmental factors monitored. Research is heavily concentrated on air and noise pollution, with significantly less attention paid to water and light pollution, and a near-total absence of studies on soil and biological contaminants.

Within the domain of air pollution, it is notable that no eligible studies were found for ozone. It is important to clarify that this reflects the specific scope of our review rather than a total absence of technology. For instance, low-cost ozone sondes are routinely deployed in China (e.g., for satellite data verification in Kunming [98]) for meteorological vertical profiling. However, these applications focus on upper-atmosphere physics and were excluded from our analysis, which strictly prioritizes portable monitoring for human exposure assessment.

What’s more, the scarcity of field studies on soil and biological contaminants involves specific technological bottlenecks regarding stability and matrix interference, rather than a total lack of sensing options. For soil monitoring, Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) have been proposed as low-cost solutions. However, quantitative reviews [99,100] highlight that unlike air sensors, ISEs in abrasive soil slurries suffer from rapid membrane fouling and leaching. Technically, this results in significant potential drift (often exceeding 1–2 mV/h) and limits the operational lifespan of unmodified sensors to often less than a week without recalibration. Furthermore, selectivity coefficients present a major hurdle; for example, high concentrations of chloride ions in soil can inherently interfere with nitrate detection, causing measurement errors that require complex compensation algorithms unsuitable for simple low-cost nodes. Similarly, for biological agents, while aptamer-based biosensors demonstrate femtomolar-level sensitivity in buffered laboratory solutions [101,102], they lack the robustness for field use. The primary barrier is environmental instability: bioreceptors are prone to irreversible denaturation at ambient temperatures (e.g., >30 °C), and effective detection typically requires labor-intensive sample pretreatment (filtration and pH adjustment) to prevent non-specific binding from complex environmental matrices. This contradicts the “portable” requirement of sensors reviewed here. Consequently, analysis of these contaminants still largely relies on traditional laboratory-based methods, as true in-situ detections such as directly inserting a sensor into soil or water for immediate, quantitative readouts of specific pollutants is not yet widely feasible.

4.2. Sensor Shortcomings

The reviewed literature points to several critical areas requiring improvement in current sensor technology: (1) The performance and accuracy of these sensors have not been thoroughly evaluated. Although most studies have calibrated the sensors with specialized equipment before using them, it is still doubtful whether they can operate reliably for long periods or maintain accuracy under certain environments (e.g., high temperature, high humidity). Only a few studies comparing the sensors with professional equipment have been reported in the literature. For example, Cui et al. [85] compared sensor measurements with satellite data. Therefore, it is not yet possible to blindly trust the data measured by these sensors. (2) Some of the sensors are large and not portable enough. For example, Lin et al. explored the automated detection of phosphate and phosphite in agricultural water environments. Although using low-cost sensors to build on-site automatic detection machines dramatically reduces costs and time compared to traditional laboratory-based detection methods such as liquid chromatography, the size of the devices is still not portable enough (280 mm in length), and there is room for further optimization. A genuinely portable sensor should be as watch-like as the sensors applied by Liu and Zilberstein et al. [15,58]. (3) Some of the sensors are disposable and cannot be reused. For example, a paper sensor was designed by Zhang et al. to directly visualize and measure mercury content in water [103]. Although it has the advantages of being low-cost, lightweight, high sensitivity, and arbitrarily tailored, it can only be used once and still causes many inconveniences. (4) The data transmission method is not convenient enough. Currently, most of the sensor data is stored on the device itself, and some early studies even required the subject to record the sensor readings in person [15]. This results in the need for periodic retrieval of the sensors, which results in inconvenient experimental procedures and geographical limitations. Therefore, the ideal data transfer method would be for the sensor to upload the collected data regularly or in real time to smartphone software, which would be uploaded to the cloud through the smartphone, where relevant personnel could download and analyze it. The bracelet-type formaldehyde sensor developed by Zilberstein et al. enables the transfer of the collected data to a smartphone through a Bluetooth channel [58].

4.3. Study Scale and Spatial Coverage

A recurring limitation across the reviewed literature is the predominance of short-term, small-scale studies. As shown in the results, monitoring durations are typically brief (e.g., [44] lasted only one week), and sample sizes are generally small (e.g., only 24 participants in [86]). Such limited cohorts undermine the statistical power and the ability to capture long-term environmental trends, which is particularly critical for investigating health outcomes.

Overcoming these scale limitations is epidemiologically vital because it directly addresses the “exposure measurement error” inherent in centralized monitoring. While regulatory stations (e.g., the US EPA instruments) provide gold-standard data for regional compliance, they inherently fail to capture personal exposure heterogeneity [104]. Crucially, individuals are mobile and typically spend over 80% of their time in indoor micro-environments (e.g., homes, offices) [105], which centralized outdoor stations cannot monitor. Consequently, relying solely on sparse, outdoor central stations fails to reflect the actual dynamic dosage received by individuals. The primary justification for low-cost sensors is their ability—when properly calibrated to maintain performance within acceptable limits—to travel with the subject or be deployed in these specific micro-environments. They provide the spatiotemporal granularity needed to link specific peaks (e.g., cooking fumes, traffic intersections) to health outcomes. Furthermore, long-term sensor deployment is strictly necessary to assess cumulative exposure for chronic disease epidemiology, moving beyond static ambient averages to capture the complex, longitudinal exposure profiles of individuals.

Technologically, low-cost sensors offer a distinct advantage in deployment of geometry and network density. While regulatory stations typically operate at a macro-scale with sparse distribution (e.g., one station per tens of square kilometers) to represent regional background levels, low-cost sensors allow for hyper-local monitoring. The reviewed studies demonstrate diverse geometries that significantly enhance resolution. For instance, Chao et al. [40] utilized a stationary grid geometry with 144 sensors to achieve high-density coverage, whereas Liang et al. [42] adopted a mobile sensing approach using 102 taxis to dynamically map pollution at the street level. These high-density configurations shift the representativeness from “district-wide” averages to the identification of specific “hotspots” in traffic canyons or industrial fence-lines that centralized networks overlook.

However, this gain in spatial resolution entails a critical cost–benefit trade-off regarding data quality. Regulatory stations provide high stability and accuracy but at high capital costs, limiting their spatial granularity. Conversely, low-cost sensors facilitate broad spatial coverage at a fraction of the cost but are prone to lower accuracy, drift, and cross-sensitivity. Therefore, achieving reliable large-scale monitoring requires accepting higher data uncertainty or implementing robust calibration strategies (e.g., using sparse regulatory stations to calibrate dense sensor networks). The current scarcity of such large-scale studies highlights that balancing the trade-off between coverage quantity and data quality remains a substantial logistic and technical hurdle.

4.4. Future Research Directions

To translate potential into widespread practical impact, future research should move beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations. While air pollution monitoring is the most mature application, studies often remain siloed, focusing on data collection in limited areas without developing generalizable models or integration frameworks. A critical next step is the creation of integrated, scalable sensing systems. This entails advancing robust, wireless data transmission protocols and building centralized data platforms. Such infrastructure is essential for achieving real-time, large-scale and personal environmental monitoring, moving from isolated studies to a cohesive network that can inform public health and policy decisions.

5. Conclusions

This review examined the application of portable low-cost sensors for monitoring environmental pollution in China. By synthesizing existing studies—detailing the types of sensors used, their purposes, and deployment methodologies, this work aims to present researchers with the current status of the field, while also discussing the strengths and limitations of both the sensors and the studies themselves. The evidence shows that these sensors significantly enhance the spatiotemporal resolution of human exposure data and serve as a vital complement to regulatory equipment, offering great versatility across various experimental designs. However, challenges remain in areas such as accuracy, miniaturization, and data transmission. It is anticipated that ongoing technological advancements will address these issues, making the large-scale application of portable low-cost sensors a reality. Importantly, while this review focuses on China, the findings carry global relevance. The unique conditions of rapid urbanization, diverse pollution sources, and high population density in China provide a critical testbed for these technologies. The universal challenges identified here, including sensor stability in complex environments, the necessity for local calibration, and deployment trade-offs, mean that the lessons learned offer valuable insights for designing robust monitoring strategies worldwide, particularly in other rapidly developing regions with comparable resource constraints and pollution profiles.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/s26010085/s1, Figure S1: Timeline and duration of field monitoring campaigns in the included PM studies; Table S1: Literature search strategy; Table S2: Technical specifications of representative low-cost sensors identified in the reviewed studies; Table S3: Summary of the included studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X.; methodology, C.Y., R.W., Y.Z. and J.X.; software, C.Y., R.W., Y.Z. and J.X.; validation, Y.Z. and J.X.; formal analysis, C.Y., R.W., Y.Z. and J.X.; investigation, C.Y., R.W., Y.Z. and J.X.; resources, J.X.; data curation, C.Y., R.W., Y.Z. and J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.Y., R.W., Y.Z. and J.X.; visualization, C.Y., R.W., Y.Z. and J.X.; supervision, Y.Z. and J.X.; project administration, J.X.; funding acquisition, J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (RLZY20231001-04 and 42407573), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University (23hytd005), the Guangdong Special Support Program (0820250237), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2025A1515010472), the Shenzhen Science and Technology (JCYJ20250604175604006), and Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Pathogenic Microbes and Biosafety (ZDSYS20230626091203007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper is available on request.

Acknowledgments

All authors have reviewed and edited the generated output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. Supported by the High-performance Computing Public Platform (Shenzhen Campus) of SUN YAT-SEN UNIVERSITY.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| YLDs | Years Lived with Disability |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter (with a kinetic diameter of less than or equal to 2.5 µm) |

| TVOCs | Total Volatile Organic Compounds |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| VIS | Visible Light |

| UVR | Ultraviolet Radiation |

References

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. Ecological and Environmental Status Bulletin. Available online: https://www.Mee.Gov.Cn/hjzl/sthjzk/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Disease Burden (gbd) Compare. Available online: http://vizhub.Healthdata.Org/gbd-compare/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Day, D.B.; Xiang, J.; Mo, J.; Clyde, M.A.; Weschler, C.J.; Li, F.; Gong, J.; Chung, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Combined use of an electrostatic precipitator and a high-efficiency particulate air filter in building ventilation systems: Effects on cardiorespiratory health indicators in healthy adults. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.B.; xiang, J.B.; Mo, J.H.; Li, F.; Chung, M.K.; Gong, J.C.; Weschler, C.J.; Ohman-Strickland, P.A.; Sundell, J.; Weng, W.G.; et al. Association of ozone exposure with cardiorespiratory pathophysiologic mechanisms in healthy adults. Jama Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A.; Burnett, R.T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E.; Krewski, D.; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.D. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Jama-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 287, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.B.; Seto, E.; Mo, J.H.; Zhang, J.F.; Zhang, Y.P. Impacts of implementing healthy building guidelines for daily pm2.5 limit on premature deaths and economic losses in urban china: A population-based modeling study. Environ. Int. 2021, 147, 106342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.B.; Weschler, C.J.; Wang, Q.Q.; Zhang, L.; Mo, J.H.; Ma, R.; Zhang, J.F.; Zhang, Y.P. Reducing indoor levels of “outdoor pm2.5” in urban china: Impact on mortalities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 3119–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.B.; Weschler, C.J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Z.W.; Duan, X.L.; Zhang, Y.P. Ozone in urban china: Impact on mortalities and approaches for establishing indoor guideline concentrations. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Evaluation of Emerging Air Sensor Performance. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/air-sensor-toolbox/evaluation-emerging-air-sensor-performance (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Rodríguez-Trejo, A.; Böhnel, H.N.; Ibarra-Ortega, H.E.; Salcedo, D.; González-Guzmán, R.; Castañeda-Miranda, A.G.; Sánchez-Ramos, L.E.; Chaparro, M.A.E.; Chaparro, M.A.E. Air quality monitoring with low-cost sensors: A record of the increase of pm2.5 during christmas and new year’s eve celebrations in the city of Queretaro, Mexico. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.; Dixit, K.K.; Mishra, S.; Kumar, P.; Shukla, A.K.; Sutaria, R.; Tiwari, S.; Tripathi, S.N. Validation of low-cost sensors in measuring real-time pm10 concentrations at two sites in delhi national capital region. Sensors 2020, 20, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, B.N.; Bi, J.Z.; Wang, W.H.; Huff, A.; Kondragunta, S.; Liu, Y. Application of geostationary satellite and high-resolution meteorology data in estimating hourly pm2.5 levels during the camp fire episode in california. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271, 112890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzidiakou, L.; Krause, A.; Han, Y.; Chen, W.; Yan, L.; Popoola, O.A.M.; Kellaway, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, M.; et al. Using low-cost sensor technologies and advanced computational methods to improve dose estimations in health panel studies: Results of the airless project. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, C.J.; Kwan, M.P.; Kou, L.R.; Chai, Y.W. Assessing personal noise exposure and its relationship with mental health in beijing based on individuals’ space-time behavior. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ono, M.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J. Individual solar-uv doses of pupils and undergraduates in china. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L.; Thai, P.K.; Liu, X.; Asumadu-Sakyi, A.; Ayoko, G.; Bartonova, A.; Bedini, A.; Chai, F.; Christensen, B.; Dunbabin, M.; et al. Applications of low-cost sensing technologies for air quality monitoring and exposure assessment: How far have they gone? Environ. Int. 2018, 116, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamone, F.; Masullo, M.; Sibilio, S. Wearable devices for environmental monitoring in the built environment: A systematic review. Sensors 2021, 21, 4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullo, S.L.; Sinha, G.R. Advances in smart environment monitoring systems using iot and sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, g.B.; Shen, w.M.; Wang, x.B. Applications of wireless sensor networks in marine environment monitoring: A survey. Sensors 2014, 14, 16932–16954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, F.; Spinazze, A.; Rovelli, S.; Campagnolo, D.; Del Buono, L.; Cattaneo, A.; Cavallo, D.M. Miniaturized monitors for assessment of exposure to air pollutants: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Luo, J.; Liao, M.; Su, Y.; Lv, M.; Li, Q.; Xiao, S.; Xiang, J. Wearable sensor-based monitoring of environmental exposures and the associated health effects: A review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, V.C.; Kazemiparkouhi, F.; Manjourides, J.; Suh, H.H. Long-term pm2.5 exposure and respiratory, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality in older us adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 186, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basith, S.; Manavalan, B.; Shin, T.A.-O.; Park, C.B.; Lee, W.A.-O.; Kim, J.; Lee, G.A.-O. The impact of fine particulate matter 2.5 on the cardiovascular system: A review of the invisible killer. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Rui, G.; Liang, Y. Study on pm2.5 pollution and the mortality due to lung cancer in china based on geographic weighted regression model. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampa, M.; Castanas, E. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 151, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: A review. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M.; Freedman, G.; Frostad, J.; van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Dentener, F.; van Dingenen, R.; Estep, K.; Amini, H.; Apte, J.S.; et al. Ambient air pollution exposure estimation for the global burden of disease 2013. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, F.; Peng, R.D.; Bell, M.L.; Pham, L.; McDermott, A.; Zeger, S.L.; Samet, J.M. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Jama-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006, 295, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, K.L.; Larson, T.V.; Koenig, J.Q.; Mar, T.F.; Fields, C.; Stewart, J.; Lippmann, M. Associations between health effects and particulate matter and black carbon in subjects with respiratory disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A. Mortality effects of longer term exposures to fine particulate air pollution: Review of recent epidemiological evidence. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007, 19, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A.; Burnett, R.T.; Turner, M.C.; Cohen, A.; Krewski, D.; Jerrett, M.; Gapstur, S.M.; Thun, M.J. Lung cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality associated with ambient air pollution and cigarette smoke: Shape of the exposure-response relationships. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Atkinson, R.; Peacock, J. Meta-analysis of time-series studies for health impact assessment of ambient air pollution in europe. Epidemiology 2004, 15, S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laden, F.; Schwartz, J.; Speizer, F.E.; Dockery, D.W. Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality—extended follow-up of the harvard six cities study. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care 2006, 173, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Shen, S.; Yang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, H.; et al. Influence of particle properties and environmental factors on the performance of typical particle monitors and low-cost particle sensors in the market of China. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 268, 118825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Jing, H.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Biswas, P. Laboratory evaluation and calibration of three low-cost particle sensors for particulate matter measurement. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, D.H.; Kroll, J.H. Assessing the accuracy of low-cost optical particle sensors using a physics-based approach. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 6343–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimifard, P.; Rim, D.; Freihaut, J. Evaluation of low-cost optical particle counters for monitoring individual indoor aerosol sources. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.T.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, S.C.; Peng, W.J.; Yu, L. An experimental application of laser-scattering sensor to estimate the traffic-induced pm(2.5)in Beijing. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F.; Li, B.; Jiang, A.M.; Qi, S.X.; Xiang, C.S.; Xu, N. A bicycle-borne sensor for monitoring air pollution near roadways. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics—Taiwan (ICCE-TW 2015), Taipei, Taiwan, 6–8 June 2015; pp. 166–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, C.Y.; Zhang, H.; Hammer, M.; Zhan, Y.; Kenney, D.; Martin, R.V.; Biswas, P. Integrating fixed monitoring systems with low-cost sensors to create high-resolution air quality maps for the northern china plain region. Acs Earth Space Chem. 2021, 5, 3022–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Q.; Ao, R.X.; Chen, H.W.; Li, J.L.; Wei, L.F.; Wang, Z.F. Characteristics of pm2.5 and CO2 concentrations in typical functional areas of a university campus in beijing based on low-cost sensor monitoring. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.H.; Wang, X.H.; Dong, Z.Z.; Wang, X.F.; Wang, S.D.; Si, S.C.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.Y.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Wang, Q. Understanding the origins of urban particulate matter pollution based on high-density vehicle-based sensor monitoring and big data analysis. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, D.Y.; Gui, X.L.; Liao, S.D.; Zhu, M.N.; Yu, F.; Zheng, J.Y. Exploring ultrafine particle emission characteristics from in-use light-duty diesel trucks in china using a portable measurement system. Environ. Res 2024, 263, 120234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.L.; Cao, J.J.; Seto, E. A distributed network of low-cost continuous reading sensors to measure spatiotemporal variations of pm2.5 in Xi’an, China. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 199, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.L.; Ying, Q.; Zheng, J.; Shi, X.W.; Hu, J.L. Long-term field evaluation of low-cost particulate matter sensors in Nanjing. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.Z.; Hou, W.Y.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Zheng, S.X.; Ainiwaer, S.; Shen, G.F.; Chen, Y.L.; Cheng, H.F.; Hu, J.Y.; Wan, Y.; et al. Temporal and spatial variation of pm2.5 in indoor air monitored by low-cost sensors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.T.; Li, J.P.; Liu, X.L.; Li, Y.J.; Jiang, K.; Luo, Z.H.; Xiong, R.; Cheng, H.F.; Tao, S.; Shen, G.F. Contributions of internal emissions to peaks and incremental indoor pm(2.5) in rural coal use households. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.N.; Zhao, B. A real-time personal pm2.5 exposure monitoring system and its application for college students. Build. Simul.-China 2024, 17, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, T.; Pehnec, G.; Jakovljević, I. Volatile organic compounds in indoor air: Sampling, determination, sources, health risk, and regulatory insights. Toxics 2025, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Cao, K.; Valaulikar, R.; Fu, X.; Sorin, A.B. Variability of total volatile organic compounds (tvoc) in the indoor air of retail stores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.S.; Gupta, G.; Mishra, R.; Patel, N.; Gupta, S.; Alzarea, S.I.; Kazmi, I.; Kumbhar, P.; Disouza, J.; Dureja, H.; et al. Unlocking the secrets: Volatile organic compounds (vocs) and their devastating effects on lung cancer. Pathol. -Res. Pract. 2024, 255, 155157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersviller, S.; Lichtveld, K.; Sexton, K.G.; Zavala, J.; Lin, Y.H.; Jaspers, I.; Jeffries, H.E. Gaseous vocs rapidly modify particulate matter and its biological effects—Part 2: Complex urban vocs and model pm. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 12293–12312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereshkov, M.; Dontsova, T.; Saruhan, B.; Krüger, S. Metal oxide-based sensors for ecological monitoring: Progress and perspectives. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho Rezende, G.; Le Calvé, S.; Brandner, J.J.; Newport, D. Micro photoionization detectors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 287, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Nan, H.; Zhong, J.; Ye, D.; Shaw, M.D.; Lewis, A.C. Low-cost photoionization sensors as detectors in gc x gc systems designed for ambient voc measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Wu, Z.Y.; Zhi, Z.N.; Gao, W.S.; Sun, W.T.; Hua, Z.Q.; Wu, Y. Practical and efficient: A pocket-sized device enabling detection of formaldehyde adulteration in vegetables. Acs Omega 2022, 7, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.Z.; Kong, S.F.; Zheng, H.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, S.R.; Cheng, Y.; Yao, L.Q.; Liu, W.; Ding, F.; Liu, X.Y.; et al. Differences in compositions and effects of vocs from vehicle emission detected using various methods. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberstein, G.; Zilberstein, R.; Zilberstein, S.; Maor, U.; Baskin, E.; Zhang, S.M.; Righetti, P.G. A miniaturized sensor for detection of formaldehyde fumes. Electrophoresis 2017, 38, 2168–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jiang, X.M.; Wu, L.; Xu, K.L.; Hou, X.D.; Lv, Y. Uv-induced surface photovoltage and photoluminescence on n-si/tio2/tio2:Eu for dual-channel sensing of volatile organic compounds. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 6552–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basner, M.; Babisch, W.; Davis, A.; Brink, M.; Clark, C.; Janssen, S.; Stansfeld, S. Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. Lancet 2014, 383, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Naghavi, M.; Lozano, R.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M.; Shibuya, K.; Salomon, J.A.; Abdalla, S.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Years lived with disability (ylds) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2163–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, N.; Schacht, J. Emerging treatments for noise-induced hearing loss. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2011, 16, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansfeld, S.A.; Matheson, M.P. Noise pollution: Non-auditory effects on health. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritschi, L.; Brown, A.; Kim, R.; Schwela, D.; Kephalopoulos, S. (Eds.) Burden of Disease from Environmental Noise; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Rao, J.W.; Kwan, M.P.; Chai, Y.W. Examining the effects of mobility-based air and noise pollution on activity satisfaction. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2020, 89, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.H.; Kou, L.R.; Chai, Y.W.; Kwan, M.P. Associations of co-exposures to air pollution and noise with psychological stress in space and time: A case study in Beijing, China. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, S.H.; Kwan, M.P.; Su, L.L.; Lu, J.W. Geographic ecological momentary assessment (gema) of environmental noise annoyance: The influence of activity context and the daily acoustic environment. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2020, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Zhou, S.H.; Kwan, M.P.; Liao, Y.T.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X. Association between real-time noise exposure in broader activity contexts and job satisfaction: Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Cities 2025, 161, 105912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Zeng, L.; Li, G.; Xu, M.; Wei, B.; Li, Y.; Li, N.; Tao, L.Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.Y.; et al. A cross-sectional study in a tertiary care hospital in china: Noise or silence in the operating room. Bmj Open 2017, 7, e016316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, C.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, J.W.; Pan, J.J.; Liu, N.; Wang, J.; Liang, C.K.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Zhang, Y.J. Associations of blood pressure and arterial compliance with occupational noise exposure in female workers of textile mill. Chin. Med. J. 2007, 120, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Gao, M.; Lu, D.Y.; Guan, H.J. Experimental study on radiation noise frequency characteristics of a centrifugal pump with various rotational speeds. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; Deng, T.S.; Wang, D.; Xu, F.; Xiao, X.B.; Sheng, X.Z. An experimental investigation into the difference in the external noise behavior of a high-speed train between viaduct and embankment sections. Shock Vib. 2022, 2022, 8827491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, W.M.; Mak, C.M.; Chung, W.L. Are the noise levels acceptable in a built environment like Hong Kong? Noise Health 2015, 17, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, W.M.; Chung, A.W.L. Noise in restaurants: Levels and mathematical model. Noise Health 2014, 16, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, Y.B.; Gu, M.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Z. Evaluation of noise hazard during the holmium laser enucleation of prostate. Bmc Urol. 2017, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Chai, D.L.; Li, H.J.; Lei, Z.; Zhao, Y.M. Assessment of personal noise exposure of overhead-traveling crane drivers in steel-rolling mills. Chin. Med. J. 2007, 120, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Song, Z.Y.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Ning, X. Health impacts of construction noise on workers: A quantitative assessment model based on exposure measurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Gao, Q.; Gao, N.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Gong, H.; Liu, Y. Solar uv exposure at eye is different from environmental uv: Diurnal monitoring at different rotation angles using a manikin. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2013, 10, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.W.; Weinstock, M.A.; Harris, A.R.; Hinckley, M.R.; Feldman, S.R.; Fleischer, A.B.; Coldiron, B.M. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch. Dermatol. 2010, 146, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, J.; Jarrett, S.; Amaro-Ortiz, A.; Scott, T. Uv radiation and the skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 12222–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, P.D.; Dumont, E.L.P. The ultraviolet index is well estimated by the terrestrial irradiance at 310 nm. Sensors 2021, 21, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.-W.; Gao, Q.; Xu, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Gong, H.-Z.; Dong, G.-Q.; Li, J.-H.; Liu, Y. Diurnal variations in solar ultraviolet radiation at typical anatomical sites. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2010, 23, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.W.; Gong, H.Z.; Yu, D.J.; Gao, Q.; Gao, N.; Wang, M.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y. Diurnal variations in solar ultraviolet radiation on horizontal and vertical plane. Iran. J. Public Health 2010, 39, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Gao, Q.; Xu, W. Skin ultraviolet exposure dosimetry using rotating manikin. China Public Health 2012, 28, 1207–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Gu, S.; Zhao, X.; Wu, J.; Kato, T.; Tang, Y. Diurnal and seasonal variations of uv radiation on the northern edge of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2008, 148, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Geng, S.; Li, Y.; IOP. Study on human responses under different CO2 concentration and illuminance in underground refuge chamber. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Renewable Energy and Development (IWRED), Electr Network, Sanya, China, 24–26 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, C.; Hao, B.; Hu, H.; Tong, Y.; Min, J.; Li, S. Design of Vehicle-Mounted Illuminance Detection System Based on Ros; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3169–3174. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.; Sun, S.; Fu, G.; Hall, J.W.; Ni, Y.; He, L.; Yi, J.; Zhao, N.; Du, Y.; Pei, T.; et al. Pollution exacerbates china’s water scarcity and its regional inequality. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Khamis, K.; Stevens, R.; Hannah, D.M.; Bradley, C. In-situ optical water quality monitoring sensors—Applications, challenges, and future opportunities. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1380133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A.; Briciu-Burghina, C.; Regan, F. Antifouling strategies for sensors used in water monitoring: Review and future perspectives. Sensors 2021, 21, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.H. Eutrophication of freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems—A global problem. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2003, 10, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Xu, J.; Lin, K.; Li, M.; Lu, M. Low-cost automatic sensor for in situ colorimetric detection of phosphate and nitrite in agricultural water. Acs Sens. 2018, 3, 2541–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.Y.; Gao, N.S.; Meng, G.P.; Zhen, L.P.; Guo, W.T.; Zhang, P.; Dai, S.J.; Wang, B.D. Metal-organic framework membrane-based probe for on-site and sensitive detection of cr(vi) in groundwater using a portable system. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, Z.S.; Aydin, S.; Bucurgat, U.U.; Basaran, N. In vitro genotoxicity assessment of dinitroaniline herbicides pendimethalin and trifluralin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 113, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farshchi, F.; Saadati, A.; Kholafazad-Kordasht, H.; Seidi, F.; Hasanzadeh, M. Trifluralin recognition using touch-based fingertip: Application of wearable glove-based sensor toward environmental pollution and human health control. J. Mol. Recognit. 2021, 34, e2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.D.; Gu, S.G.; Wang, D.D. Wearable design for occupational safety of pb2+ water pollution monitoring based on fluorescent cds. Autex Res. J. 2023, 23, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Niu, Q.; Wang, J.; Wei, T.; Li, T.; Chen, J.; Qin, X.; Yang, Q. Bithiophene-based fluorescent sensor for highly sensitive and ultrarapid detection of Hg2+ in water, seafood, urine and live cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A-Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 233, 118208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chai, S.; Tang, X.; Zhou, B.; Bian, J.; Vömel, H.; Yu, K.; Wang, W. Verification of satellite ozone/temperature profile products and ozone effective height/temperature over Kunming, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 661, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Dong, L.; Dhau, J.; Khosla, A.; Kaushik, A. Perspective—Electrochemical sensors for soil quality assessment. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 037550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Lee, K.H. Electrochemical sensors for sustainable precision agriculture-a review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 848320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira-Antunes, B.; Ferreira, H.A. Nucleic acid aptamer-based biosensors: A review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.M.; Nguyen, J.; Li, Y. Aptamer-based biosensors for environmental monitoring. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W.; Le, X.; Li, P.; Huang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Serpe, M.J.; Chen, D.; et al. Fluorescent hydrogel-coated paper/textile as flexible chemosensor for visual and wearable mercury(ii) detection. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1800201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]