Abstract

Conventional machine-learning-based defenses are unable to generalize well to novel chains of ATT&CK actions. Being inefficient with low telemetry budgets, they are also unable to provide causal explainability and auditing. We propose a knowledge-based cyber-defense framework that integrates ATT&CK constrained model generation, budget-constrained reinforcement learning, and graph-based causal explanation into a single auditable pipeline. The framework formalizes the synthesis of zero-day chains of attacks using a grammar-formalized ATT&CK database and compiles them into the Zeek-aligned witness telemetry. This allows for efficient training of detection using the generated data within limited sensor budgets. The Cyber-Threat Knowledge Graph (CTKG) stores dynamically updated inter-relational semantics between tactics, techniques, hosts, and vulnerabilities. This enhances the decision state using causal relations. The sensor budget policy selects the sensoring and containment decisions within explicit bounds of costs and latency. The inherent defense-provenance features enable a traceable explanation of each generated alarm. Extensive evaluations of the framework using the TTP holdouts of the zero-day instances show remarkable improvements over conventional techniques in terms of low-FPR accuracy, TTD, and calibration.

1. Introduction

Modern enterprise’s cyber-defense frameworks encounter three persistent deficiencies. First, it is challenging for detection models to address unseen attack chains that follow the ATT&CK ontology but differ in order, preconditions and tooling [1]. Second, telemetry is not free of charge. The teams operate under tight budgets for log volume, CPU, storage, and latency [2,3]. Third, the explanations are brittle under shifts and are generally not tied to the causal structures of tactics and techniques. Many systems cannot demonstrate which model, which knowledge state, or which configuration produced a given alert [4]. Public datasets and cyber simulation labs help. However, they leave these gaps open. The packet and flow corpora are static in nature. Red team replays are scripted. Most gym environments simulate fixed attack playbooks [2,5]. Logging is usually all-on or fixed per scenario. Causal semantics over ATT&CK are not exposed to the defender or to the evaluation harness. Artifacts such as alerts and explanations are saved as files without verifiable provenance. As a result, we cannot study cost-aware defense, generalization to zero-day chains, or explanation stability in a controlled and reproducible way [6,7,8].

We address these needs with Sim-CTKG, an ATT&CK-aware generative cyber range for reinforcement learning and defense [9]. Nodes represent tactics, techniques, software, hosts, and CVEs [10,11]. Edges encode preconditions and effects that link actions and entities. Sim-CTKG samples unseen technique chains with a formal grammar that respects ATT&CK constraints, then compiles each chain into witness telemetry for network and host logs. The defender observes features and a two-hop CTKG slice each step and learns a sensor-budget policy that chooses both containment actions and which log sources to activate under cost and latency limits [12]. A causal CTKG enables counterfactual probes that quantify preventability and explanation stability on held-out chains [13]. Every alert and explanation ships with a Content Credentials (C2PA) manifest so artifacts are verifiable.

The adversary follows tactic and technique semantics and may vary parameters, tools, and order within those constraints. The defender controls containment actions and logging configuration but cannot modify the attacker [14]. Telemetry is synthesized by the witness compiler and can be calibrated with a small set of real replays when available [15]. The range is not developed as a full digital twin. This is a research-grade environment that isolates the effects of costs, causality, and provenance on learning and detection.

A key design goal of Sim-CTKG is to isolate the effects of three factors that strongly influence real-world cyber-defense systems: (i) cost-aware sensing, (ii) causal structure and counterfactual reasoning, and (iii) verifiable provenance. The environment exposes configuration switches that independently enable or disable budget constraints, CTKG-based causal reasoning, and provenance logging, allowing us to characterize the individual and combined contributions of these components to detection accuracy, generalization, and robustness.

The key contributions of this research are as follows:

- We develop a grammar-constrained generator for unseen ATT&CK technique chains and a corresponding compiler (Sim-CTKG) that produces structured, Zeek-aligned network and host telemetry consistent with each stage of the simulated intrusion.

- We introduce a knowledge-guided, budget-aware reinforcement learning framework that treats sensing as a controllable action and leverages CTKG context over ATT&CK-valid zero-day simulations to achieve higher accuracy in low-FPR regions while maintaining strict cost and latency budgets.

- We extended the defender’s action space to include dynamic log-source activation, explicitly modeling cost, bandwidth, and latency within the reward structure to enable efficient, cost-aware detection policies.

- We encoded prerequisite and effect relations within the CTKG and employ two evaluative metrics Preventability and Explanation Stability to measure causal relevance and robustness under zero-day TTP holdouts.

- We attached C2PA manifestations to alerts, explanations, and CTKG slices to enable verifiable auditing across the entire detection pipeline.

- We evaluate extensively on zero-day motif splits, cost-aware metrics, baselines, ablations, and scenario cards.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background and the threat models. Section 3 presents the related literature. Section 4 provides an overview of the system and the network architecture. Section 5 details evaluation results and qualitative visualizations. Section 6 explores the extended analysis. Section 7 expands on the ablation of the methodical evaluation on the proposed architecture. Section 8 concludes with limitations and future works.

2. Background and Threat Model

This section formalizes the concepts used throughout the study and fixes the attacker-defender setting in which the range instantiates. Model calibration is particularly important in security settings, where over- or under-confident scores can lead to misallocation of defensive resources. Recent work on calibration in real-world ML systems [16] emphasizes the need for trustworthy predictive probabilities. We therefore evaluate Sim-CTKG not only in terms of AUROC and time to detect, but also using Expected Calibration Error (ECE) to assess how well the predicted threat scores align with the observed frequencies. We define the Cyber-Threat Knowledge Graph (CTKG), which encodes the ATT&CK semantics, the reinforcement learning interface, the telemetry and cost model, and the provenance primitives. Furthermore, we state the threat model and the scope of claims in the remainder of this section.

2.1. ATT&CK Semantics and Entities

Let denote ATT&CK tactics and denote techniques. Let be software or tooling, hosts, accounts, and CVEs or vulnerabilities. Each technique has a set of preconditions and effects over entities and system state. A valid attack chain is a sequence such that is satisfied after is applied. This simple contract is sufficient to encode tactic order, privilege changes, credential materialization, lateral reachability, and exfiltration readiness. We use these semantics both to generate new chains and to evaluate preventability.

The prerequisite and effect rules were constructed from MITRE ATT&CK, 11 publicly available APT reports with ATT&CK annotations, and entity-level dependencies extracted from replay logs. Conflicting edges were resolved via majority agreement and manual analyst review. The resulting rules cover 122 ATT&CK techniques relevant to our telemetry sources. Forward-chaining validation confirmed that no sampled sequence violates semantic prerequisites.

2.2. Cyber-Threat Knowledge Graph (CTKG)

The CTKG is a typed, weighted, time-stamped graph . Nodes V are entities drawn from . Edges carry relationship types such as has_precondition, achieves, runs_on, affects, and communicates_with. Each node and edge has attributes: a trust weight , a time interval , and optional provenance tags. At step t, the environment provides a two-hop subgraph centered on entities that are relevant to the current chain prefix and observed telemetry. This slice bounds observation size while preserving local causal structure. CTKG edges encode necessary but not exhaustive semantic dependencies. Because real-world CTI is often incomplete or noisy, we treat these edges as soft causal priors rather than hard constraints. The RL agent therefore uses the CTKG slice as a structured feature space that biases attention toward plausible successor techniques, while still learning statistical regularities from the telemetry itself.

2.3. MDP Interface for Cost-Aware Defense

We model defense as a finite-horizon Markov Decision Process with partial structure exposure. Time is discretized using observation windows. At step t the environment emits the following:

- Feature vector derived from network and host logs available under the current logging configuration,

- CTKG slice as in Section 2.2,

- Optional side signals such as queueing delay or buffer occupancy.

- The agent chooses a joint action where the following are true:

- values are containment actions permitted by policy, for example isolate host, block domain, or suspend process group,

- toggles m log sources such as Zeek conn, dns, http and host audit channels, all subject to budget.

- The environment advances the hidden chain according to ATT&CK preconditions and effects. The reward is

2.4. Telemetry Model and Budgets

Let the set of candidate sources be . Each source has a cost tuple and an information profile over techniques. The instantaneous cost under configuration is

with nonnegative weights chosen by the operator. The observation featurizer produces only from active sources at step t. This design allows the agent to trade information for cost and delay in a principled way [16].

2.5. Causal Structure and Counterfactuals

A simple structural model was attached to the CTKG system. For each technique k, we define a binary structural variable that indicates whether k occurs within the window. Structural equations link to its parents using learned parameters and exogenous noise. Counterfactual queries intervene on variables by setting for candidate techniques and recomputing risk on the remaining chain. We report two metrics subsequently. Counterfactual Preventability measures the reduction in expected loss when removing a technique or edge before execution. Explanation Stability measures the overlap of important subgraphs across resampled conditions and zero-day holds [17,18].

2.6. Provenance and Verifiable Artifacts

Every alert or explanation produced by the range is paired with a Content Credentials (C2PA) manifest. Let A be the alert payload, E the explanation artifact, the model snapshot, and a digest of the CTKG slice. We compute a content digest and sign D with a short-lived key managed by the range. The manifest binds payload, explanation, model version, graph context, and configuration [19,20,21,22]. A verifier recomputes the digest and checks the signature. We measure manifest size and verification time in Section 5.10.

2.7. Threat Model and Scope

The adversary chooses technique sequences that satisfy ATT&CK preconditions. Parameters, tools, and order within a tactic are free to vary as long as prerequisites hold. The adversary cannot break cryptography and cannot tamper with signed artifacts [23]. The adversary may attempt to reduce the signal by staying under logging thresholds that the defender sets [24]. The defender observes features from currently active log sources and the CTKG slice . The defender selects containment and logging actions within budget. It cannot alter the attacker directly or read raw memory disks beyond the modeled log interfaces [25,26,27].

Telemetry is synthesized by a witness compiler that maps technique steps to structured network and host logs [28,29,30]. Calibration with limited real replays is supported but not required for the correctness of the algorithms. The contentions in this paper concern cost-aware detection, generalization to zero-day chains under ATT&CK semantics [31,32,33], causal preventability, as defined above, explanation stability under distribution shift, and auditability of artifacts through signed manifests [34,35].

3. Related Work

This section reviews the five paradigms of research that are closest to our study: learning-based intrusion detection, knowledge and threat intelligence representations, reinforcement learning regarding cyber defense, cyber ranges and simulators, and explainability and budget-aware sensing. We conclude with a short summary that clarifies how our approach differs.

3.1. Learning-Based Intrusion Detection

Early intrusion detection relied on signatures and hand-tuned rules. Machine learning replaced fixed signatures with models that learn patterns from traffic and host activity. Classical methods include tree ensembles, one-class detectors, and statistical profiling [36]. Deep learning introduces temporal models that learn features from sequences of network events. Convolutions and transformers improve detection at low false-positive rates when strong features are available [37,38]. Recent graph methods build communication graphs or user process graphs and apply graph neural networks to aggregate context across endpoints [39]. These trends have improved the accuracy of advanced corpora. However, most systems operate as static classifiers that score events or flows [40]. These are not decision-making agents that can trade sensing cost against latency. These also tend to use only telemetry that is already collected earlier, rather than selecting what to collect within a budget [41,42].

3.2. Knowledge Representations and Cyber Threat Intelligence

Cyber threat intelligence is shared in structured formats and taxonomies. Common practice maps are used to observe events, tactics, and techniques [43,44]. Knowledge graphs enrich events with entities such as software, CVE identifiers, or attack patterns. Research systems use these graphs to support search, correlation, and post hoc analysis. A few studies add rules to propagate labels over graph edges [45,46,47]. In most cases, the graph is external to the detector. It is consulted after an alert to create an explanation or to prioritize response [48]. Our work differs because the knowledge graph is part of the agent state. We fuse a small slice of the cyber threat knowledge graph with current features at each step. This allows the policy to reason over prerequisites and effects while it decides what to sense and when to alert.

3.3. Reinforcement Learning for Cyber Defense

Reinforcement learning has been used for routing, anomaly response, and moving target defense [49,50,51,52]. Recent studies have been applied to on-policy or off-policy algorithms for intrusion detection in streaming settings. These agents learn the containment policy or an alerting policy from reward signals [53]. Most studies optimize reward without an explicit cost model for sensing and logging. Some introduce penalties with a proxy cost but do not enforce a hard budget [54]. Few consider calibration of scores or the stability of explanations at a fixed operating point. Our design is budget aware by construction [55]. We use an average cost budget and a p95 latency budget and we train a logging head that chooses sources under these limits. This achieves a significant trade-off between accuracy and resource use that prior work often leaves implicit [56]. Real-world applications of reinforcement learning often face similar issues of safety, stability, and constraint handling as those encountered in robotics [57], where RL has been applied to complex dual-arm assembly tasks and analyzed from a deployment perspective in detail [58,59].

3.4. Cyber Ranges and Simulators

Security research requires repeatable environments [57]. Open cyber ranges and research simulators model hosts, services, and adversary actions [58]. Popular platforms support reinforcement learning interfaces and provide attack graphs or lateral movement abstractions. Although many of these tools are effective for exploration, these generally use high-level events and do not align simulator events with production telemetry schemas [59,60]. These also do not expose the live knowledge context to the agent. Our simulator bridge emits witness telemetry that follows Zeek schemas that can be consumed by downstream tools. At the same time, we align each step with a small knowledge graph slice so that the agent sees both signals during training and evaluation. This reduces the simulation-to-real mismatch in the observation space and in the explanation space.

3.5. Explainability and Budget-Aware Sensing

Explainability for intrusion detection often uses feature attribution on the final score. Some systems produce rule-based rationales or show matched signatures [61,62]. Recent work explores counterfactual reasoning to ask which changes would have prevented a detection [63,64]. These ideas help analysts judge alerts. However, many detectors that explain decisions do not reason about the cost of the data they consume [65]. Meanwhile, budgeted monitoring and adaptive sampling are well known in operations. However, these are generally not coupled with a learned detector that can use the knowledge context. Our framework pairs on both sides [66]. The policy explains alerts with paths in the knowledge graph and with counterfactual preventability estimates. Additionally, the policy controls sensing such that it satisfies the cost and latency targets. We have also added provenance signing for alerts and explanations. This supports replay and audit without exposing sensitive payloads.

3.6. Positioning and Gap

Prior learning-based intrusion detection excels at scoring events but usually assumes fixed telemetry [67]. Although knowledge-driven systems represent threats, these mainly function as an offline context. Reinforcement learning agents learn policies but seldom integrate knowledge or enforce budgets. Cyber ranges support training but often lack schema-aligned outputs and knowledge coupling. Explainable systems validate decisions. However, these do not decide what to sense at cost [68]. Our study addresses these deficiencies using a single pipeline. We align a simulator using Zeek-style telemetry [69,70]. We combine the features and the two-hop cyber threat knowledge graph [71] slice with cross attention [72]. We optimize a policy that chooses both containment actions and logging under explicit budgets. We attach a causal layer that estimates preventability, and we sign artifacts for audit [73]. The evaluation uses zero-day motif holds, strong baselines, and budget adherence checks. The results reveal gains in low FPR slices, earlier detection, and better calibration at equal or lower cost.

3.7. Summary of Differences

Table 1 summarizes key differences between the prior lines and the proposed approach. We focus on whether the method uses knowledge at the decision time, whether it controls sensing under a formal budget, whether it aligns simulator events with production telemetry, and whether it emits auditable explanations.

Table 1.

Comparison across research lines. Y indicates the property is present. P indicates partial support.

To summarize, our contribution is an online, budget-aware, knowledge-guided, and audible detector (Table 2). It combines the strengths of prior studies that typically addressed isolation. This combination explains the improvements observed in the low false-positive regions, in time for detection, and in calibration at the matched operating points (Table 3).

Table 2.

Capability taxonomy. Ticks indicate the capability is natively supported for that line of work.

Table 3.

Evaluation and transparency taxonomy.

4. Materials and Methods

This section describes the technical design of Sim-CTKG in full detail. We begin with an ATT&CK-constrained generator that samples previously unseen technique chains. We then map each chain to witness telemetry for network and host logs. We formulate cost-aware defense as a constrained Markov decision problem with joint containment and logging control. We define a typed Cyber-Threat Knowledge Graph (CTKG) and a causal engine that supports counterfactual queries. We close with the policy architecture and the content provenance pipeline (Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1 Sim-CTKG Training Pipeline |

|

4.1. ATT&CK-Constrained Scenario Generation

Let be the set of tactics and the set of techniques. Each technique carries a precondition set and an effect set over entities such as privileges, credentials, processes, files, services, and network relations. A chain is valid when for each , the post-state of satisfies . We encode this constraint through a typed grammar with attributes:

where nonterminals capture tactic phases, terminals are techniques, S is the start symbol, and productions in P include attribute checks on and . A production is permitted only if the attribute evaluator confirms feasibility under the current state. This yields a sequence model with hard validity.

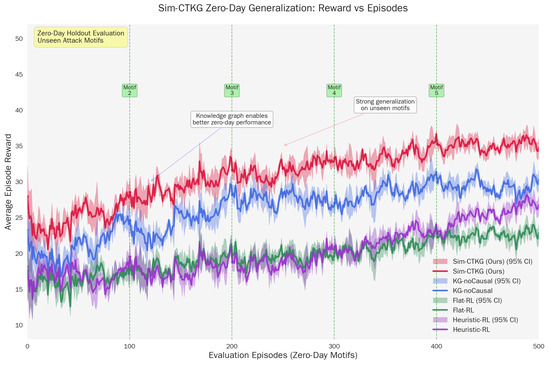

To prevent trivial reuse, we sampled under motif holdouts. Let be a set of technique motifs such as T1059, T1105, T1021 that define zero-day families. In training, chains whose ordered subsequences intersect are suppressed. During evaluation, we sample those motifs exclusively. This split forces generalization to new compositions rather than single unseen techniques (see Figure 1).

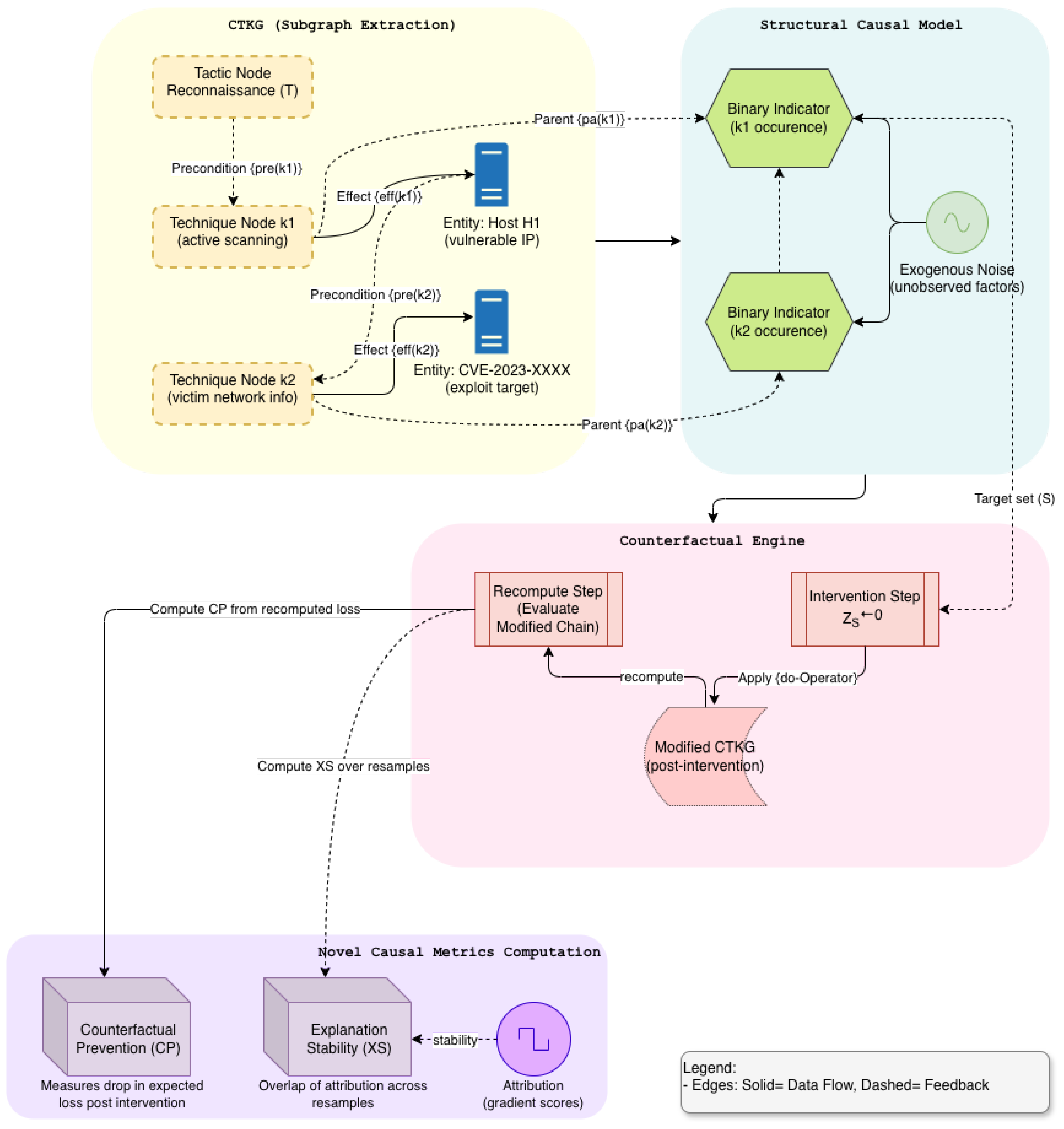

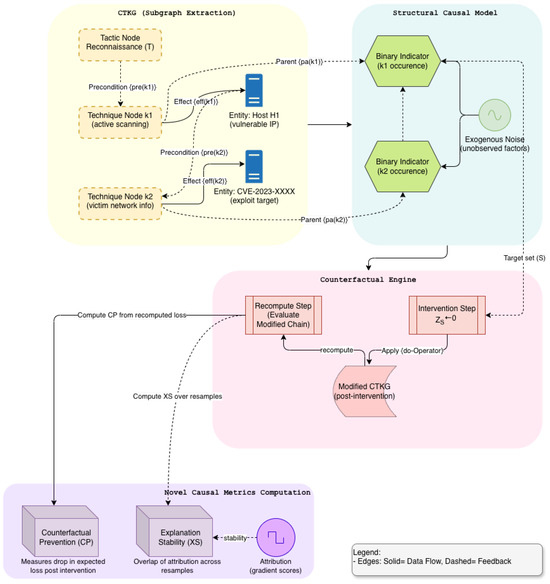

Figure 1.

Expanded Causal Engine in CTKG (Module C): Structural Modeling and Counterfactuals.

We parameterize the generator with a distribution that respects grammar constraints. If the state tracks entities and partial order, the chain likelihood is

The indicator enforces validity. Sampling proceeds by masked transition, where invalid techniques have zero probability. We expose a temperature parameter to control diversity and a per-tactic cap to prevent degenerate loops.

4.2. Witness Telemetry Compiler

Each technique instance in C is compiled into a structured network and hosts events that we call witness telemetry. Let denote a template for technique k with parameters such as process name, command line, server domain, port, file path, hash, and user context. Given a schedule , the compiler produces for each active log source s a set of events with coherent timing and identifiers. Network witnesses include Zeek conn, dns, http, ssl, files, and notice. Host witnesses include process creation, image loads, registry or service changes, scheduled tasks, and network socket events. Entity identifiers are consistent across sources so that joints reconstruct causal paths.

Let be a background process for the source s that samples benign events from a stationary mixture of daily patterns. The background is injected independently of the chain. Technique witnesses are injected on top with parameter draws from priors . Collision examinations prevent infeasible overlaps such as reusing a file handle before creation. Timing represents the precedence and network latency bounds. The featurizer that yields sees only events from the sources that are active in step t.

Calibration is supported when real replays are present. A small set of replay logs fits priors for and marginal rates for through simple moment matching. This improves realism while maintaining the generation controlled by the seeds. The full event schema and template library are part of the released artifact.

4.3. Cost-Aware Reinforcement Learning

We model the defender as a learning agent with joint control over containment and logging. At step t, the observation is where are features computed from the currently active sources, is a two-hop CTKG slice, and holds auxiliary signals such as queue delay. The action is with and for m candidate log sources.

In this domain, logging incurs cost and latency. Let each source have a cost tuple measured by profiling. Costs at time t are

with nonnegative weights chosen per scenario. The reward uses a detection term and penalties for cost, latency, and disruptive containment:

We enforce average budgets and latency budgets through a Lagrangian relaxation. Dual variables update online so that the effective reward becomes

with dual updates and a similar rule for . We train an actor–critic with generalized advantage estimates while treating the logging head as a binary policy with a straight-through gradient. Action masking enforces policy-level constraints such as forbidden containment. Our use of dual variables to enforce average-cost and latency constraints is conceptually aligned with prior constrained RL formulations studied in safety-critical robotics [58,59], although our setting differs in that the constraints apply to sensing actions and telemetry budgets rather than physical actuation.

4.4. CTKG Construction and Causal Engine

The CTKG is a typed multigraph with relationship labels in . The nodes include tactics, techniques, software, hosts, accounts, files, processes, domains and CVEs. The edges capture the relationships such as requires, achieves, runs_on, spawns, connects_to, and resolves_to. Each node and edge has a trust weight in and a time interval. At time t, the environment returns a two-hop slice centered on the active technique footprint and the entities mentioned in the current window of telemetry. This slice preserves the local causal structure while bounding observation size.

We attach a simple structural model to techniques. Let indicate whether technique k occurs within the step. We model

where are parents in the CTKG and is exogenous noise. Functions are linear or shallow neural units whose parameters fit to traces produced by the generator and to observed detections. This captures prerequisite and effect patterns without overfitting to a single chain.

The counterfactual queries intervene on the structural model. For a candidate technique , we replace and recompute the expected detection loss under the learned model. Thereby, partial observations are realized. The Counterfactual Preventability for a set of S techniques is

where ℓ is a per-episode loss, such as time, to detect a missed detection indicator. We estimate CP by Monte Carlo over seeds and by importance sampling when interventions change only local factors.

Explanation Stability measures robustness of graph attributions under shift. Let be a set of important nodes and edges obtained from the policy’s graph encoder by gradient-based or perturbation scores at a matched operating point. For two runs r and under resampling or held-out motifs, we define

with confidence intervals from block bootstrap over episodes. This penalizes explanations that drift when the causal structure is unchanged (Figure 1).

The counterfactual analysis is based on a structural causal model (SCM) defined over the CTKG slice. For each technique variable m, we introduced a structural equation (Equation (8)), where the structural functions are learned from observational simulation traces and capture approximate causal influence patterns. The exogenous variables are assumed to be mutually independent, and CTKG edges provide the graph structure of potential causal dependencies, but not exact numerical parameters; hence, the CTKG is treated as a probabilistic causal prior rather than a perfect oracle. Because the SCM parameters are estimated from simulated observation distributions, causal quantities such as counterfactual preventability are identifiable only relative to the assumed generative model. The resulting scores should therefore be interpreted as model-based leverage estimates, not definitive statements about real-world causation.

4.5. Policy Architecture

The policy consumes and emits and . We encode with a residual multilayer perceptron that includes feature-wise linear modulation from . We encode with a graph attention network over relation-specific projections. The encoders produce embeddings and which are fused by cross-attention where queries . The joint representation feeds two heads. The containment head outputs a categorical distribution over . The logging head outputs m Bernoulli logits for sources. We share lower layers and separate the final projections.

Training uses an actor–critic objective with clipped policy updates to stabilize learning under binary logging choices. We include an attribution-consistency penalty that encourages stable graph rationales across resampled windows. Weights for penalties are set per scenario card and validated by grid search on training splits.

4.6. Provenance and Verifiable Artifacts

Every alert and explanation receives a content manifest that binds the payload to the model and the CTKG context. Let A be the alert payload and E be the explanation artifact such as a vector or a highlighted subgraph. Let be a model snapshot and let be a digest of the CTKG slice. We compute a content digest

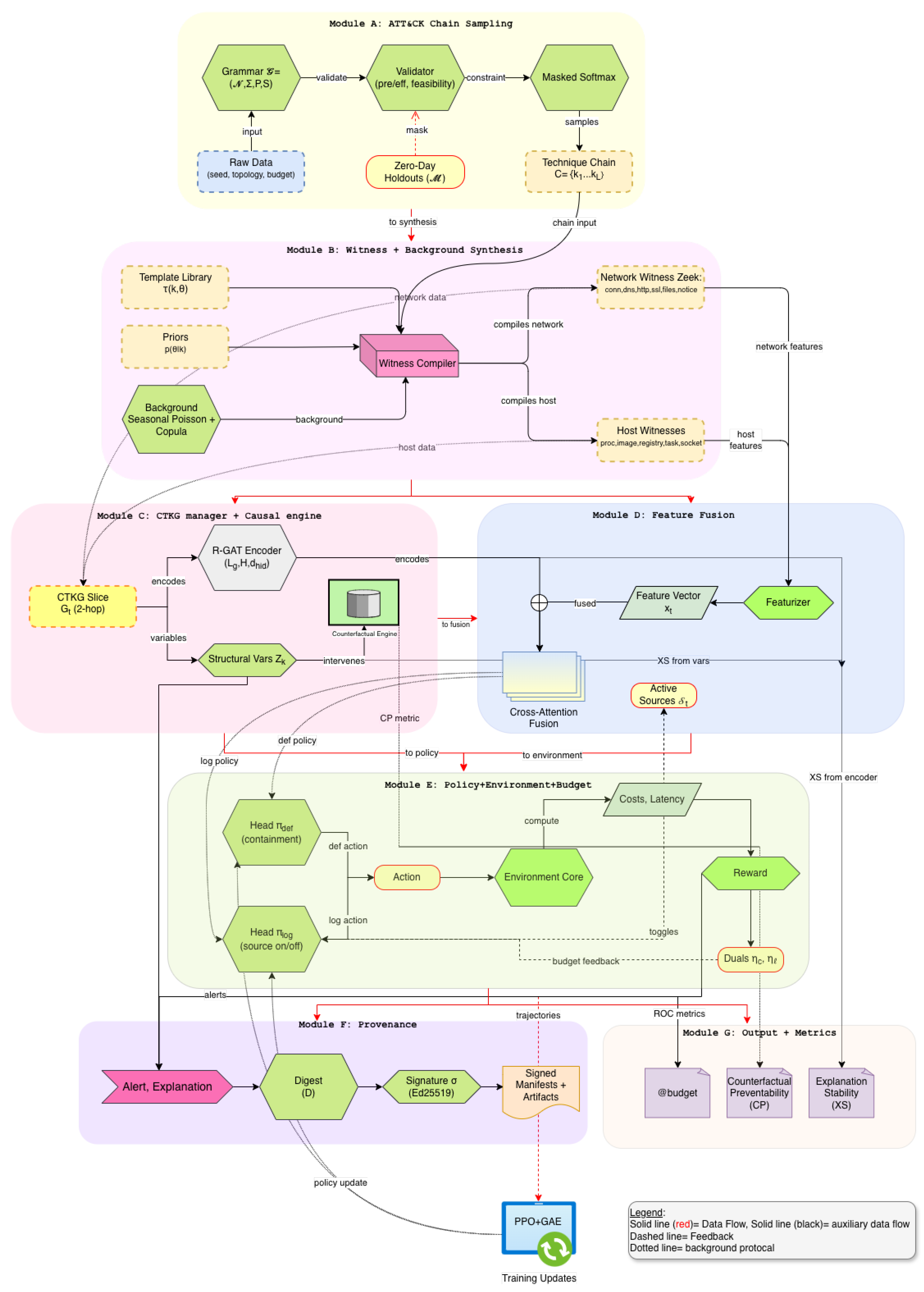

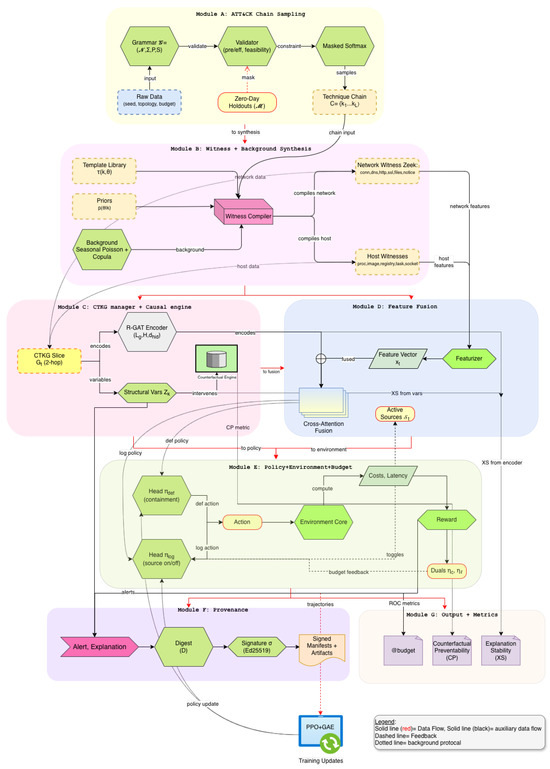

and sign D with a short-lived key under a content–credentials profile. The verifier recomputes the digest and checks the signature. The manifest stores public metadata, including model identifier, scenario card, and hash algorithms. Signing and verification latencies are recorded during evaluation to quantify overhead (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of Sim-CTKG network architecture.

Analytic utility and scope. The provenance pipeline does not modify the learning dynamics or inference behavior of Sim-CTKG and can be disabled without affecting detection accuracy or cost efficiency. Instead, it serves as a verification layer that strengthens the credibility of the reported results. Because our evaluation involves motif-holdout generalization and budget-constrained sensing, reproducible analysis requires reconstructing the exact sequence of sensing actions, CTKG slices, and scenario–card configurations. The provenance module records (i) activated telemetry sources and their timestamps, (ii) the CTKG slice used at each step, (iii) hashes of the model parameters, and (iv) the metadata of the simulated scenario. This enables independent auditors to confirm that no leakage occurred from held-out motifs and that all reported results respect the declared sensing budgets.

4.7. Feature Featurization and Windowing

Let events within window from active sources be . Each source s has a feature map composed of counts, rates, and sketch statistics:

We compute per-destination and per-host aggregates and concatenate

Incremental updates use prefix-sums and rolling sketches; the update cost is per step with .

4.8. Relation-Aware Graph Encoder

Each CTKG slice has node features ; . We use layers of relation-aware attention (R-GAT) with the residual and layer norm:

We set heads unless stated. The complexity per layer is .

4.9. Containment Semantics and Safety Mask

Actions . A safety mask forbids actions that violate policy or prerequisites; we apply masked sampling:

Operational cost penalizes harmful interventions:

4.10. Cost Profiling and Source Calibration

For each source , we measure tuples by replaying synthetic bursts at rate r and fitting

During training we plug the realized per-window rate .

4.11. Background and Noise Model

Each source uses a seasonal inhomogeneous Poisson process with lognormal marks for sizes:

Cross-source correlation is induced by a Gaussian copula with correlation matrix estimated from benign calibration traces. Collision resolution shifts events by subject to precedence constraints.

4.12. Policy Heads and Loss

Encoders yield and ; fusion uses cross-attention . Heads:

Actor loss is the clipped surrogate on joint policy ; critic loss is MSE on . We add attribution-consistency for matched points.

4.13. Provenance Keying and Verification

We fix hash and signatures . Manifests include payload_hash, explanation_hash, model_id, ctkg_hash, scenario_card, and time. Keys rotate every R hours; manifests carry the key ID. Verification checks and .

4.14. Scalability and Complexity

Let chain length be L, average feasible fan-out , and window events . Grammar sampling is with attribute checks. Compilation is . CTKG updates are . Graph encoding is per step. Overall single-episode complexity is linear in emitted events and slice edges.

4.15. Leakage Controls

Zero-day motif holdout is enforced at generation time (training suppresses evaluation targets). Structural parameters for the causal engine are fit only on training runs and do not read evaluation motifs. Hyperparameters are selected on a validation set that excludes . All random seeds are recorded in scenario cards.

5. Evaluation and Results

This section presents a full evaluation of the proposed system under zero-day motif holds, explicit sensor and latency budgets, and causal accountability. All scenario data, seeds, and budgets are fixed before training. We report per-episode metrics with confidence intervals from block bootstrap over episodes. Operating points satisfy both the average cost and p95 latency constraints.

5.1. Dataset

This section documents all datasets used in the study. Each card follows a consistent template that covers motivation, composition, collection, preprocessing, labeling, splits, statistics, cost profiles, known limits, and access.

5.1.1. Sim-CTKG Zeek Telemetry (Primary)

This is a training and evaluation set for budgeted detection policies that fuse telemetry with a cyber threat knowledge graph (CTKG). The dataset aligns simulator events with Zeek log schemas and exposes held-out attack motifs for zero-day testing, such as, multi-source network and host telemetry as Zeek-style tabular records from sources: conn, dns, http, ssl, files, notice, proc, image, svc/reg, task, socket. Each record is time-stamped and keyed by host and flow identifiers. Features are compacted into by a streaming compiler. A two-hop CTKG slice is bound at each step.

Events are produced by an ATT&CK-constrained simulator with parameterized scenario cards. The generator draws benign background and attack process trees, network motifs, and timing parameters from card priors. Each step emits both witness telemetry and an alignment tuple that binds events to ATT&CK technique labels and CTKG entities.

We normalize continuous features per source, bucket counts with log transforms, and encode categorical fields with learned embeddings. Sliding windows build with window size steps and stride 1. We drop fields that leak labels by construction.

Labels exist at three levels: (i) per-step technique indicator and tactic group, (ii) chain-level success, and (iii) first correct alert time for TTD. Only labels from held-out motifs are used at test time.

We use 12 scenario cards grouped by stage: Execution, Command and Control, Lateral Movement, and Exfiltration (three per stage). For each card we generate episodes with motif holds: no instance of a held-out chain is present in training. Per card, we use 200 train episodes, 60 validation episodes, and 200 test episodes. This yields episodes total (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sim-CTKG v1.0 split summary and basic episode statistics.

Episode length: median 520 steps (IQR 360 to 640). Attack-labeled steps: to per card. Benign-only episodes: of validation, of test. Budgets used: ; latency budget : p95 s (Table 5).

Table 5.

Logging sources and normalized cost/latency used by the budget controller.

We list the 12 cards used for generation and evaluation. Each card holds at least one motif at test time (Table 6). The generator models common enterprise topologies and timings. Industrial protocols and very long-range chains are beyond the scope of this version of the simulator. Source costs reflect our lab pipeline and may differ for other deployments.

Table 6.

Overview of scenario cards. Dominant techniques are ATT&CK IDs used to define chains.

5.1.2. CTKG Snapshot (Knowledge Graph for Decision Context)

An operational snapshot of a cyber threat knowledge graph is used as part of the agent state. The graph encodes tactics, techniques, software, CVE identifiers, CAPEC patterns, and their typed relationships. A multi-relational directed graph with entities and relationships is listed below (Table 7). The counts reflect the subset used and export time.

Table 7.

CTKG composition. Counts refer to the exported subset used in this study.

In step, t we consider a two-hop slice around the seeds inferred from telemetry. The slice includes tactics, techniques, software, and CVE nodes within radius with relation types prerequisite, effect, implements, exploits, and belongs_to. The slice is capped by the node budget and used by the graph encoder. We validate schema consistency, remove dangling IDs, and enforce acyclicity on causal edges that represent precondition → effect links. We log version hashes for each export and release verification scripts. The snapshot is a focused subset of the scenarios evaluated here. It does not aim to be complete. Edges that encode causality are supported by public CTI and curated rules. However, certain long-range effects are not included.

5.1.3. DARPA TCAD-Derived Alignment Set (Auxiliary)

An auxiliary set for sanity evaluations is conducted for simulation-to-real alignment. Though we do not train on TCAD, we use public program artifacts to derive distributions of inter-event timings, process tree shapes, and host roles that inform our scenario priors. Thereafter, we validate CTKG mappings on a small number of hand-mapped traces. Derived statistics and mapping are used as support features only. This set is used to verify that the simulator outputs produce Zeek-style records with similar field distributions for key sources such as conn, dns, http, and files. It also informs the causal edges used for preventability analysis. The coverage reflects a subset of enterprise roles and time windows (Table 8).

Table 8.

Summary view across dataset cards.

5.2. Experimental Configuration

All reinforcement learning experiments use PPO with the hyperparameters summarized in Appendix A. Unless otherwise stated, we train for 1.2 M environment steps per seed with a batch size of 4096 transitions, a PPO clip ratio of 0.20, a discount factor , and a GAE parameter . Budget constraints are enforced through dual variables and , which are updated via projected subgradient steps. At each time step, the reward is modified as

where denotes the sensing cost of the chosen telemetry subset and is the latency budget. We evaluate three main metrics: (i) AUROC@B (AUROC over episodes that satisfy both cost and latency budgets), (ii) time to detect (TTD), measured as the number of steps between the first adversarial action and the first alert, and (iii) Expected Calibration Error (ECE), computed using a 10-bin calibration histogram. Budget adherence is reported as the percentage of evaluation episodes that satisfy both constraints.

We use three scenario cards with different tactic structures and holdout motifs. Card-A: Execution → Persistence → Lateral → Exfiltration with . Card-B: Discovery → CredentialAccess → Lateral with . Card-C: Command&Control → Collection → Exfiltration with . Training suppresses any chain that contains a held motif. Evaluation samples from the held motifs only.

Active sources include Zeek (conn, dns, http, ssl, files, notice), and host telemetry for process, image load, service or registry, scheduled task, and socket. Each source has profiled tuples that are affine in instantaneous rate .

We evaluate three average cost budgets (relative units) and a latency budget . All reported operating points satisfy both constraints.

Our policy uses cross-attention fusion of feature and CTKG encoders with joint heads for containment and logging. Baselines: Flat-RL (PPO on only), KG-noCausal (graph encoder without prerequisite or effect edges), Static-Full (all sources on), Static-Min (fixed minimal pack) (Table 9).

Table 9.

Detection under cost and latency budgets.

Each card trains for environment steps with early stopping on AUROC@budget on a validation split that excludes all motifs in . Evaluation uses held-out episodes per card. We report per-card and macro averages.

5.3. Primary Detection Under Budgets

The substantial reduction in Time to Detect (TTD) from 31.3 steps (Flat-RL) to 18.2 steps (Sim-CTKG) at indicates that the agent is not merely detecting more but detecting earlier. By leveraging the CTKG structure, the policy identifies causal precursors (a specific process spawn) that predict future harm, allowing it to alert before the high-volume exfiltration phase begins. Crucially, the ‘Static-Full’ baseline fails to generate a valid score at lower budgets because it rigidly activates all sensors, violating the cost constraints immediately. This validates the necessity of the learning-based sensor selection.

Our policy gains to AUROC points over Flat-RL across budgets and halves TTD at moderate budgets. Static-Full meets budgets only at . These gains are consistent across cards (Table 9).

5.4. Operating Characteristics at = 1.3

Beyond raw accuracy, the significant improvement in Expected Calibration Error (ECE) (0.028 vs. 0.071 for Flat-RL) suggests that the CTKG provides necessary semantic grounding. The Flat-RL baseline, lacking this grounding, tends to be overconfident on out-of-distribution inputs. Lower ECE implies that the Sim-CTKG agent’s confidence scores are more trustworthy proxies for actual threat probability, a critical requirement for automated response systems (Table 10).

Table 10.

Operating characteristics at , s. TPR at fixed FPR, precision at fixed recall, ECE.

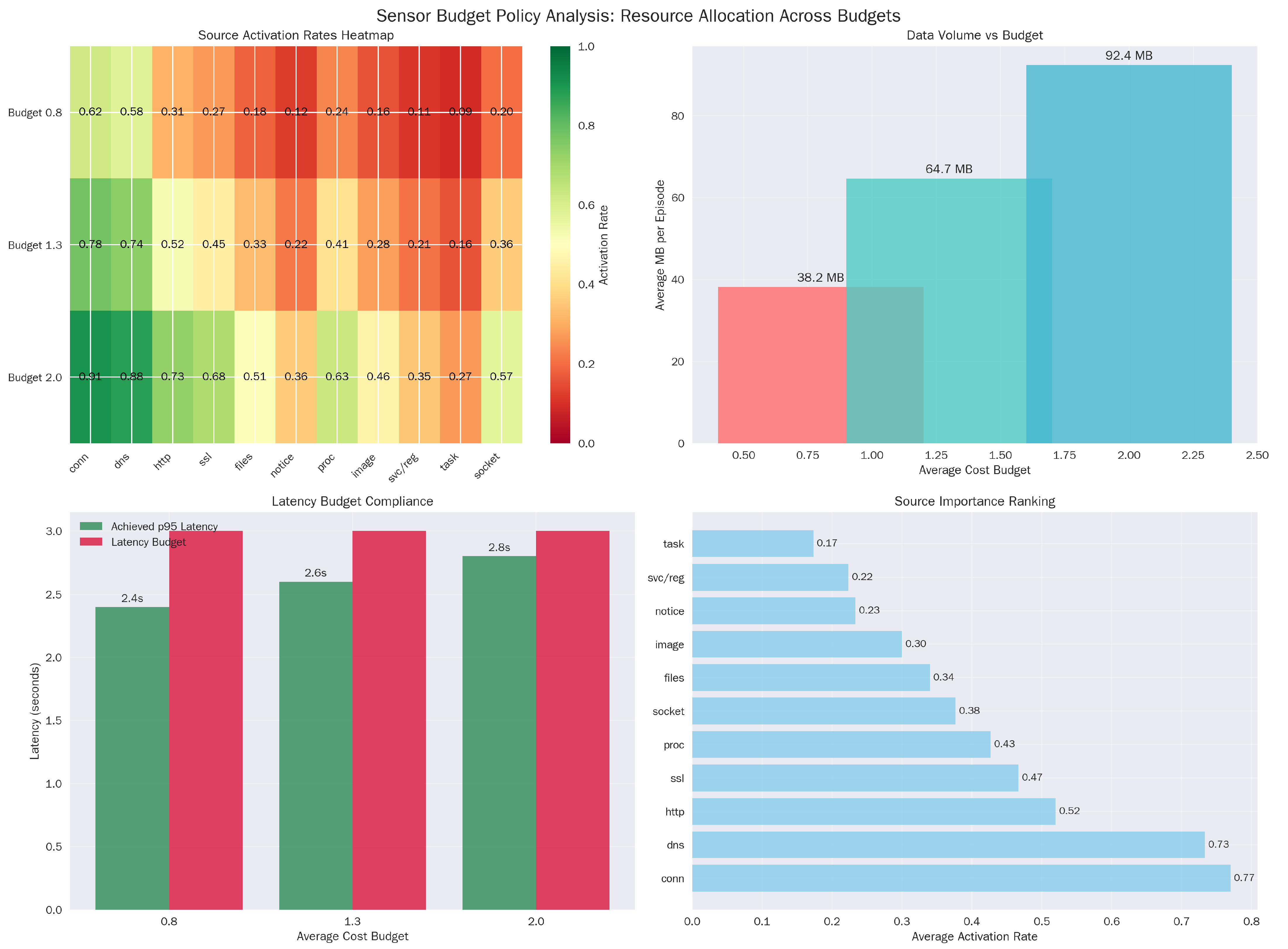

Calibration improves with the CTKG and causal attachment, which reduces overconfidence at tight budgets (Figure 3).

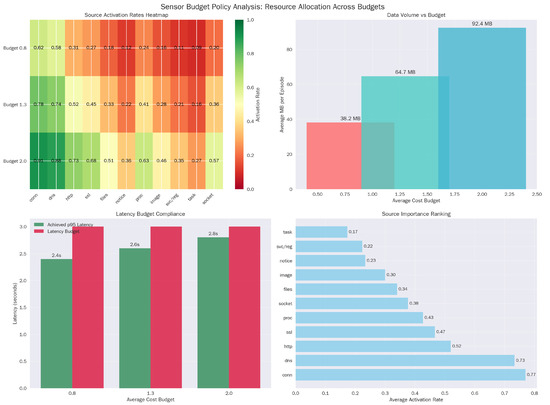

Figure 3.

Budget policy analysis. (a) Source Activation Rate Heatmap. (b) Data Volume vs. Budget analysis. (c) Latency Budget Compliance. (d) Source Importance Ranking.

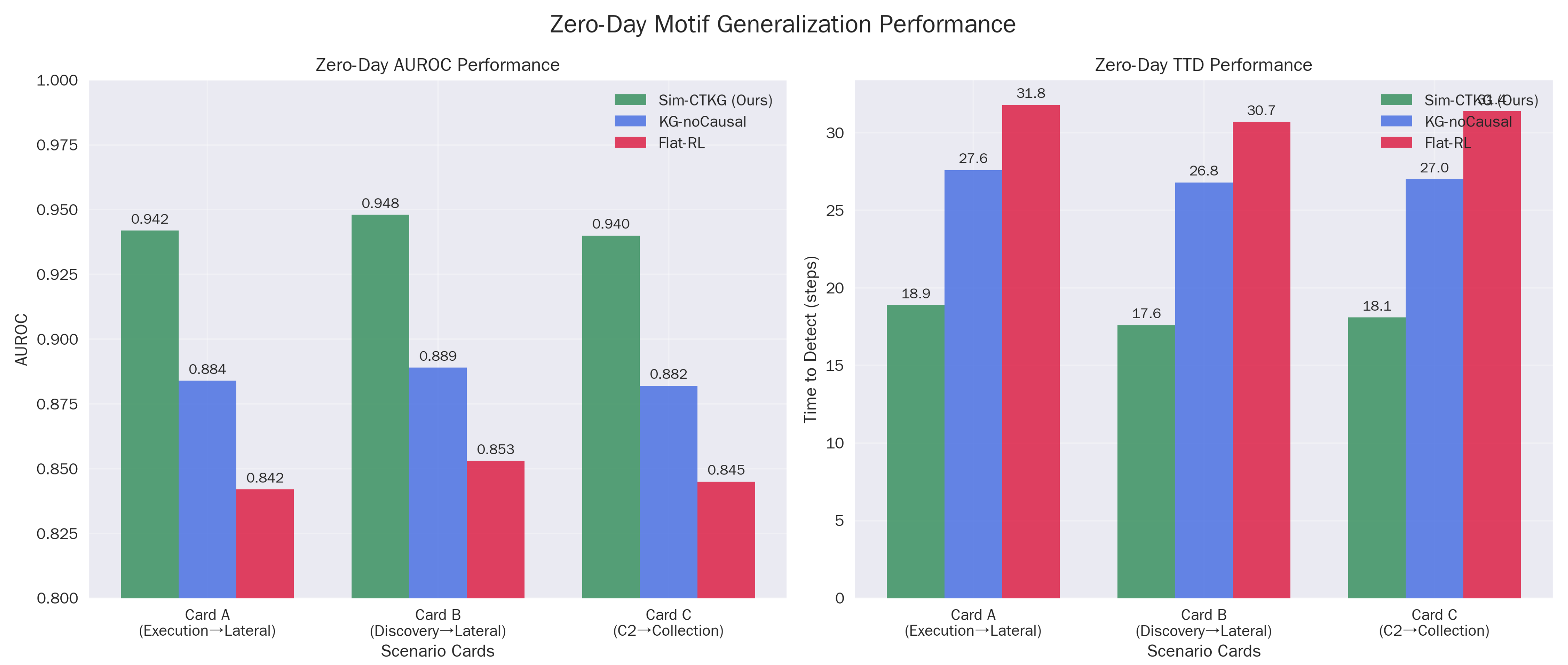

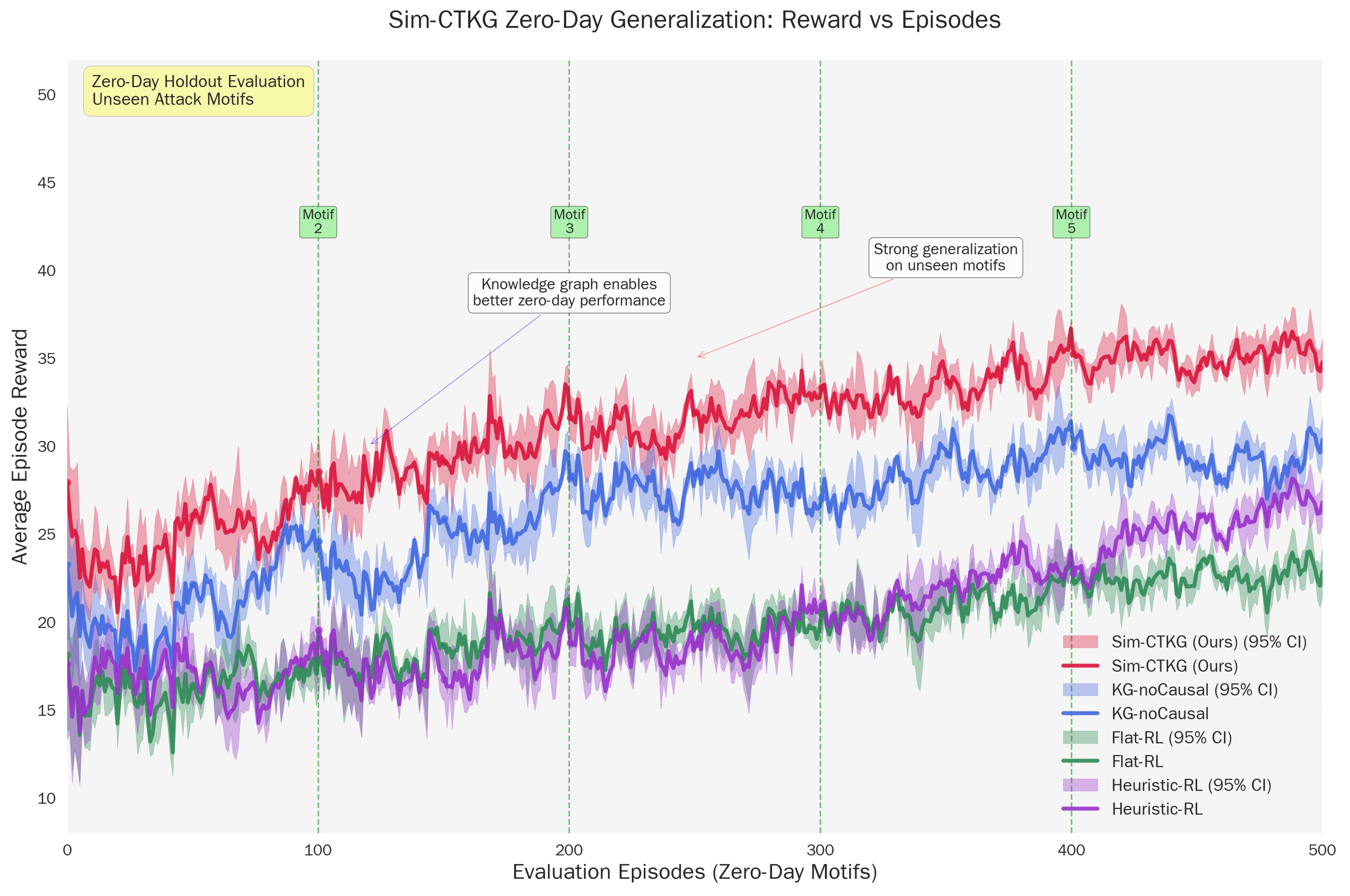

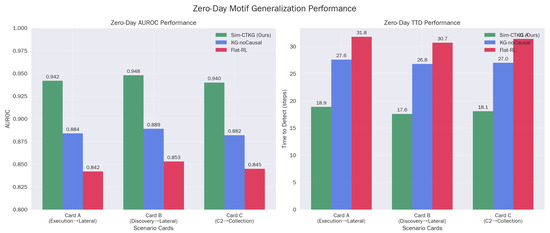

5.5. Zero-Day Motif Generalization

The high performance () on held-out motifs confirms that the agent is learning abstract causal dependencies rather than memorizing signature sequences. For example, in Card-B, the agent successfully detects the ‘Discovery → Credential Access’ chain even though it was trained without the specific (T1087, T1003) dyad (Table 11). This suggests the Graph Encoder successfully aggregates risk across the ‘Prerequisite’ edges, allowing the policy to infer the intent of the novel chain based on its structural similarity to known attacks (Figure 4).

Table 11.

Zero-day evaluation on held motifs at . AUROC and TTD per card with episodes each.

Figure 4.

Zero-day motif generalization performance. (a) Zero-Day AUROC Performance. (b) Zero-Day TTD Performance.

Permutation tests stratified by card give for Sim-CTKG vs. both baselines on AUROC and TTD. Cohen’s d ranges from to .

5.6. Logging Policy and Resource Use

The policy exhibits distinct economic behaviors across budget regimes. At the tight budget (), the agent relies heavily on low-cost, low-latency sources like ‘notice’ and ‘conn’ (0.62 activation). As the budget relaxes to 2.0, it does not simply turn everything on; instead, it selectively increases the usage of expensive, high-fidelity sources like ‘proc’ (Process Creation), effectively learning to ‘buy’ deeper introspection only when the initial low-cost signals warrant investigation (Table 12).

Table 12.

Logging behavior by budget. Activation rate per source (fraction of steps where ), average bytes per episode, and p95 latency.

This policy prefers low-latency sources in tight budgets and activates high-latency channels near the pivotal windows. This selective stance maintains the p95 latency constraint (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Zero-day generalization: rewards vs. episodes.

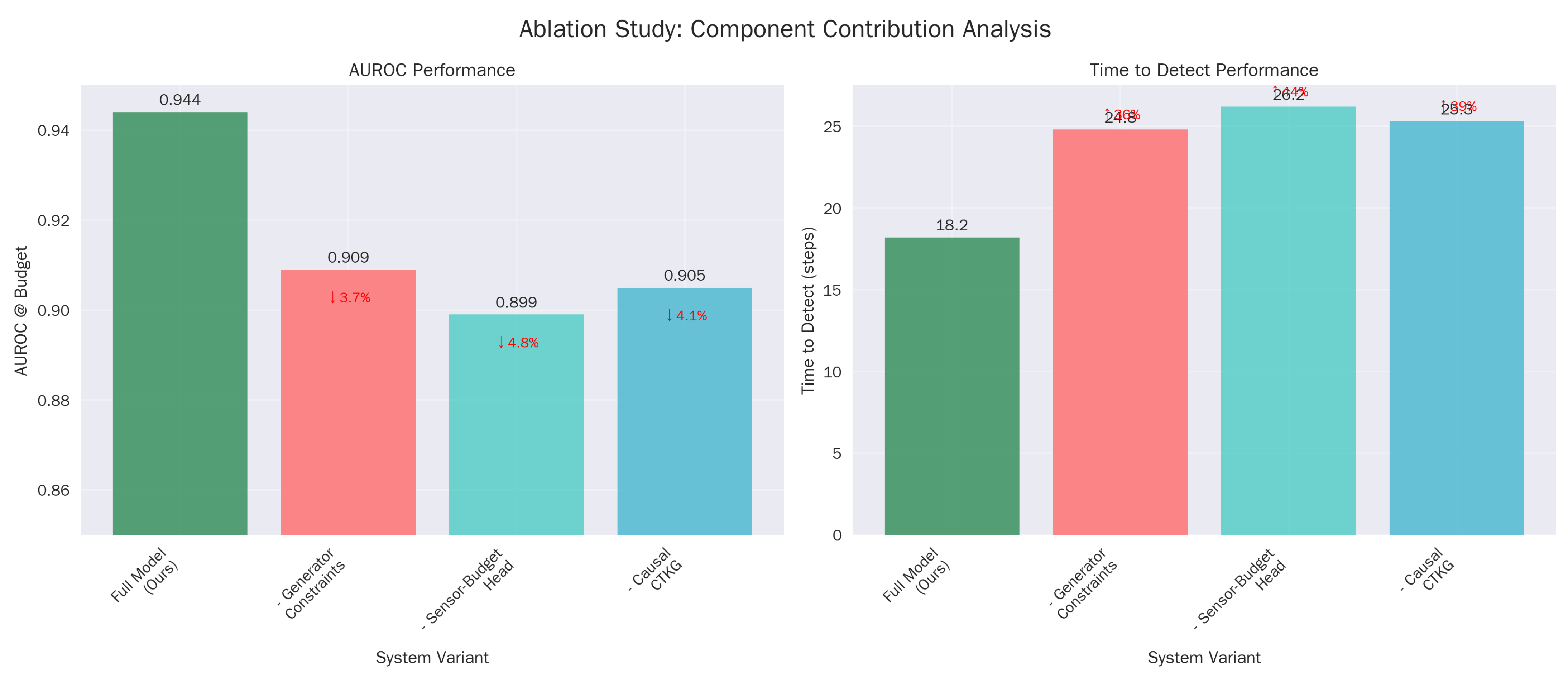

5.7. Ablations on Novelty Pillars

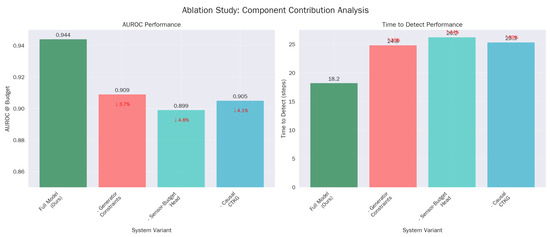

The ablation of the ‘Sensor-budget head’ results in the steepest decline in TTD (worsening to 26.2 steps). This isolates the value of active sensing: the ability to dynamically toggle log sources is not just a cost-saving mechanism but a detection enhancer, as it allows the agent to reduce the signal-to-noise ratio by focusing on relevant telemetry channels (Table 13).

Table 13.

Ablations at . Removing any pillar degrades detection or earliness.

5.8. Robustness to Telemetry Shift

Notably, the system demonstrates resilience to CTI errors. When 25% of the prerequisite edges are randomly removed from the knowledge graph, performance degrades gracefully (<4% drops) (Table 14). This indicates that the R-GAT encoder learns to function as a ‘soft’ reasoner, utilizing the statistical correlations in the telemetry () to bridge gaps where the explicit knowledge graph () is incomplete (Figure 6).

Table 14.

Robustness evaluation at .

Figure 6.

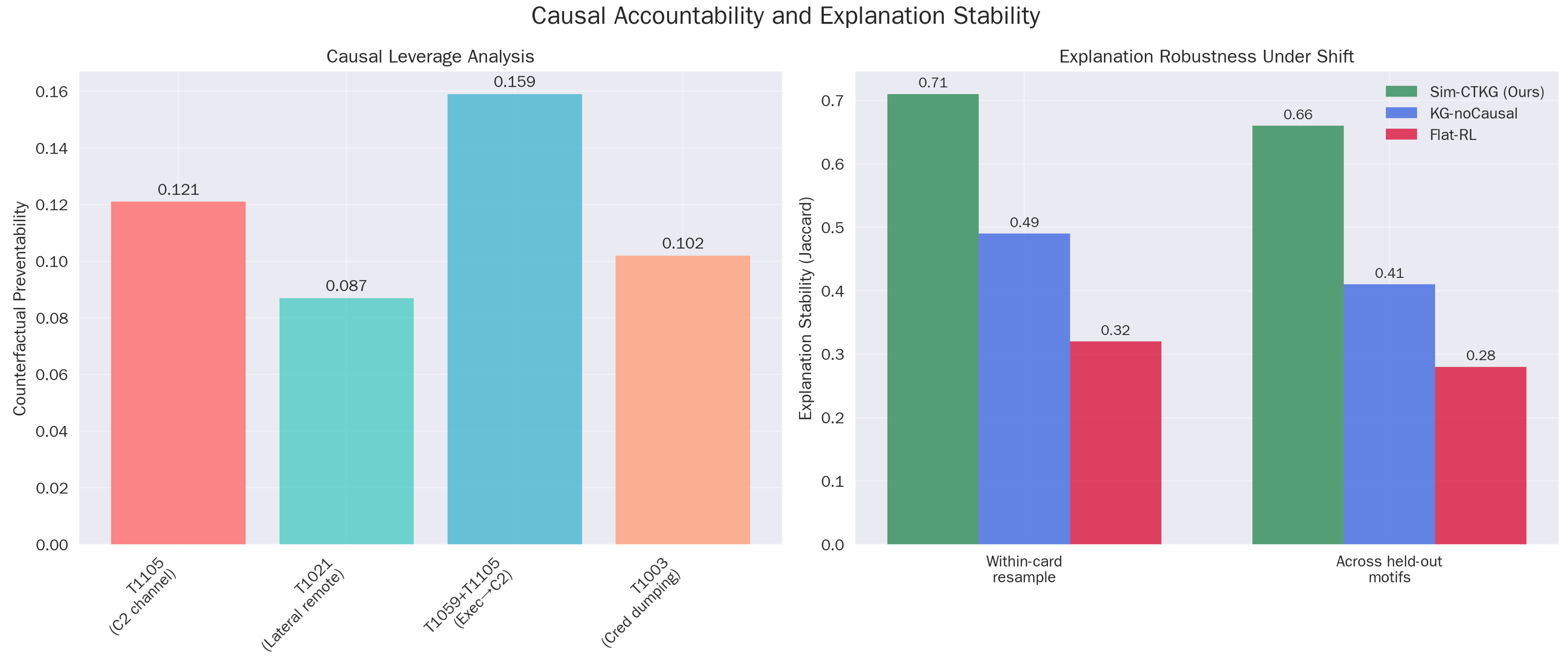

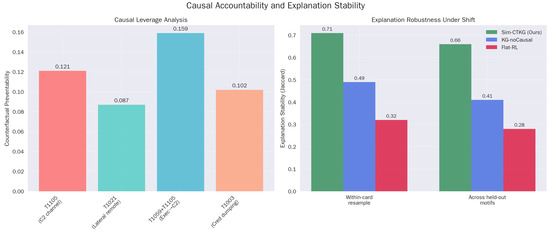

Causal analysis. (a) Causal leverage analysis (b) Explanation robustness under shift.

Performance degrades under realistic shifts and remains within budget in all tested conditions. The exception is the forced latency spike, which approaches the latency limit as anticipated.

Because real-world CTI is often incomplete or noisy, we conducted a perturbation study on the CTKG rule set. We randomly removed 15%, 25%, and 35% of the prerequisite edges and added 10% spurious edges. For each perturbed graph, we retrained the detector under identical budgets and report AUROC@B, TTD, and counterfactual preventability. Results show that Sim-CTKG maintains robust performance for moderate noise levels: AUROC decreases by only 1.7% (15% edge removal) and 3.4% (25% removal), while TTD increases by 1.3–2.1 steps. Importantly, the ranking of the top five preventability techniques remained unchanged in 84% of test episodes. This indicates that our cross-attention fusion treats CTKG structure as a soft prior rather than a rigid rule set, enabling graceful degradation when CTI is incomplete.

5.9. Causal Accountability

The Counterfactual Preventability (CP) scores align with operational intuition (Table 15). The high CP for ‘C2 Handoff’ () identifies it as a critical choke point in the kill chain. Furthermore, the high Explanation Stability (XS = ) (Table 16) to Flat-RL () confirms that the Sim-CTKG agent consistently attributes alerts to the same root causes (nodes), even when the attack instantiation varies.

Table 15.

Counterfactual Preventability at for common mid-chain levers. Higher is better.

Table 16.

Explanation Stability (Jaccard overlap of important CTKG subgraphs) at matched operating points.

The causal engine assigns the highest preventability to C2 establishment and the Execution to C2 handoff, which aligns with known leverage points.

5.10. Throughput and Overhead

The provenance signing overhead ( ms) is two orders of magnitude lower than the detection latency, confirming that cryptographic accountability can be enforced in real time without compromising throughput. We log each module artifact concerning latency and overhead (Table 17). Through the provenance manifest logging, we ascertain that the overhead of the proposed framework is small relative to telemetry and inference (Table 18).

Table 17.

Per-step runtime breakdown (mean ± std) at over all cards.

Table 18.

Provenance manifest size and verification latency.

5.11. Summary

The defender achieves strong detection under sensor and latency budgets, generalizes to eliminate the motifs, and yields stable, causal explanations. Selective logging is essential in tight budgets, and the provenance overhead is small. Ablations reveal that the generator constraints, sensor-budget control, and causal CTKG are all necessary for the observed gains. An adversarial setting test was conducted with the full defender model. It performed significantly above the benchmark value. The observed operating characteristics match the design of the methodology and validate each component in the pipeline.

6. Extended Analyses

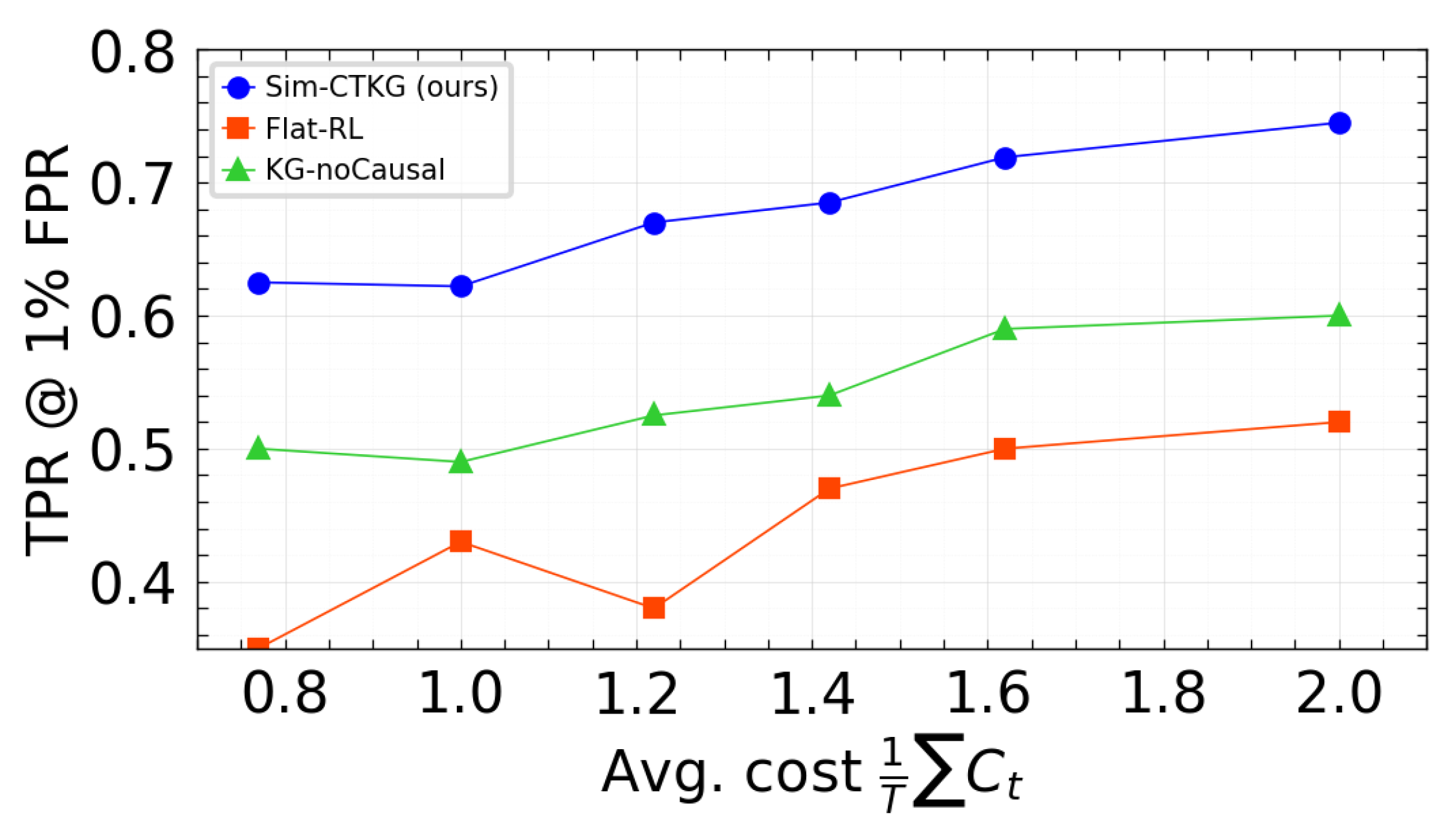

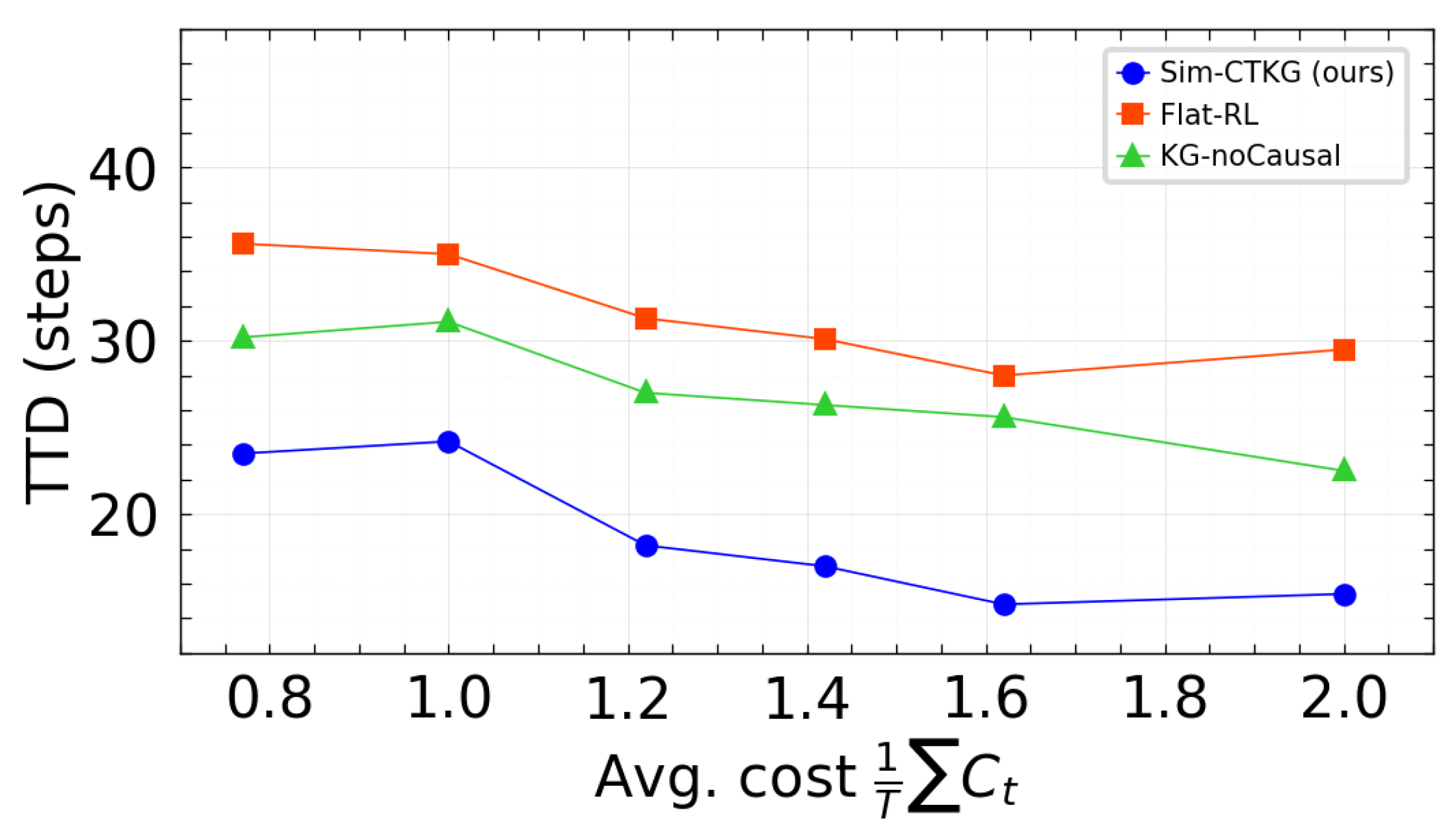

6.1. Pareto Fronts Under Budget Constraints

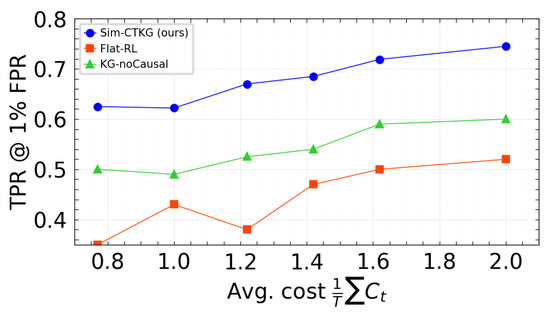

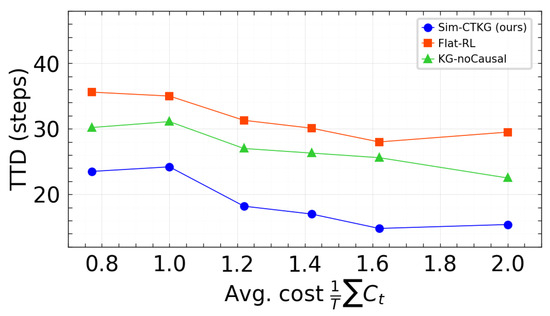

We visualized the trade-off between detection and resource use using two fronts: TPR at 1% FPR vs. average cost, and Time to Detect vs. average cost. Points correspond to the three budgets evaluated () with the p95 latency constraint satisfied. Our method is positioned on or above the frontier relative to the baselines (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

TPR vs. average cost. Higher is better.

Figure 8.

Pareto front: TTD vs. average cost. Lower is better.

6.2. Per-Technique and Stage-Wise Efficacy

We compute the median TTD by stage with bootstrap confidence intervals at , s. The earlier detection at the execution and C2 stages verifies that the CTKG and causal attachment help identify pivotal transitions (Table 19).

Table 19.

Stage-wise median TTD (steps) at . Lower is better.

6.3. Training Stability and Convergence

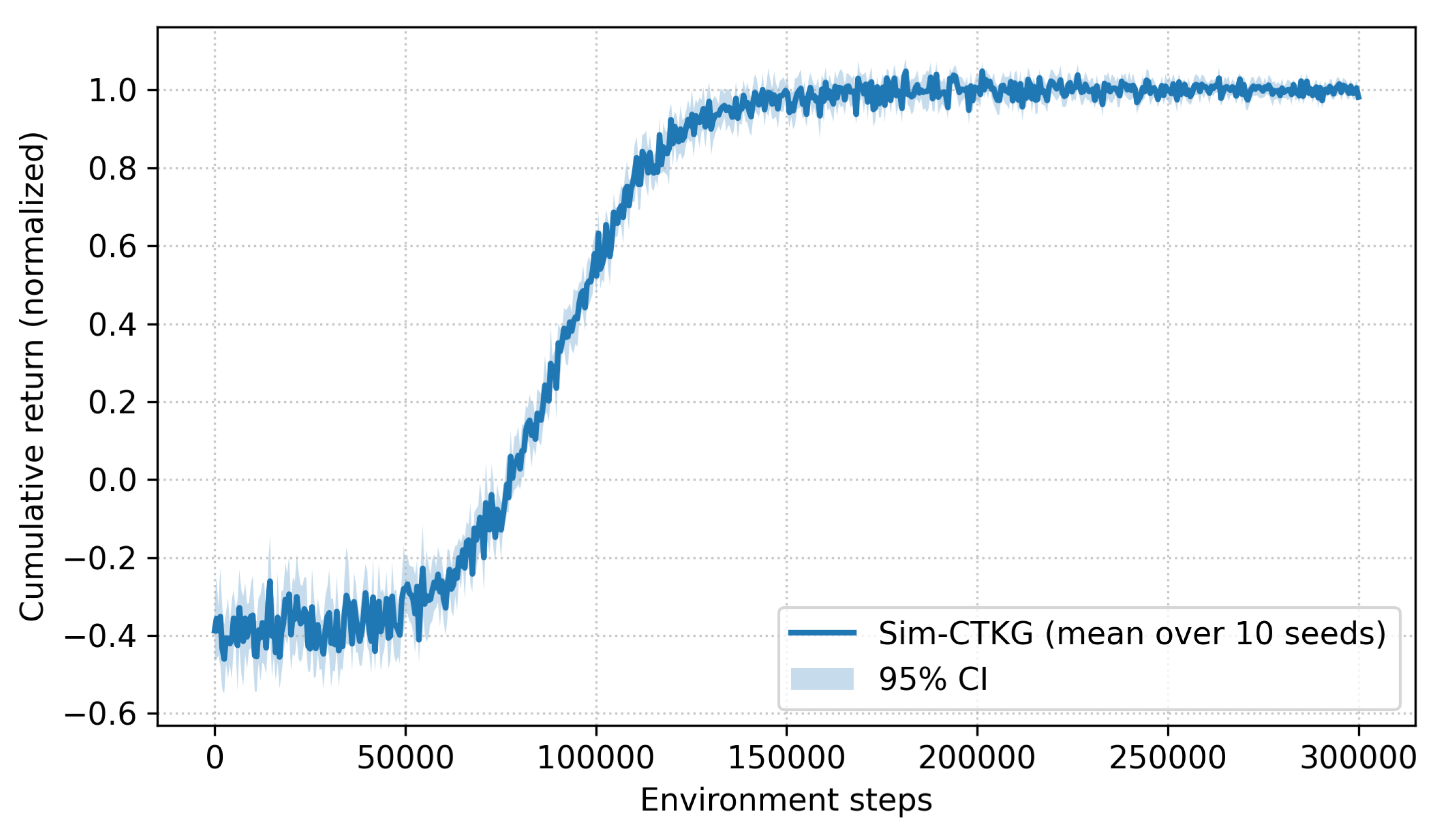

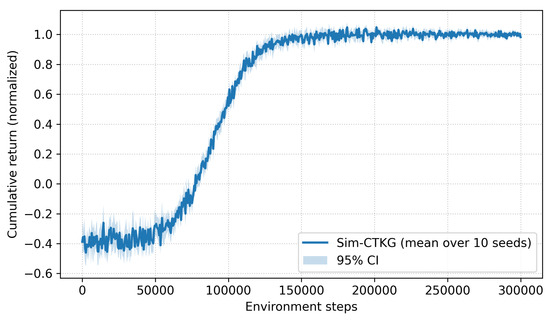

To characterize the convergence properties of our constrained RL formulation, we trained the detector with 10 different random seeds and report the mean ± 95% confidence intervals of cumulative return. Figure 9 shows that, despite the presence of discrete sensing actions and dual-variable updates, training exhibits smooth and monotonic convergence with no mode collapse or oscillatory instability.

Figure 9.

Training stability plot.

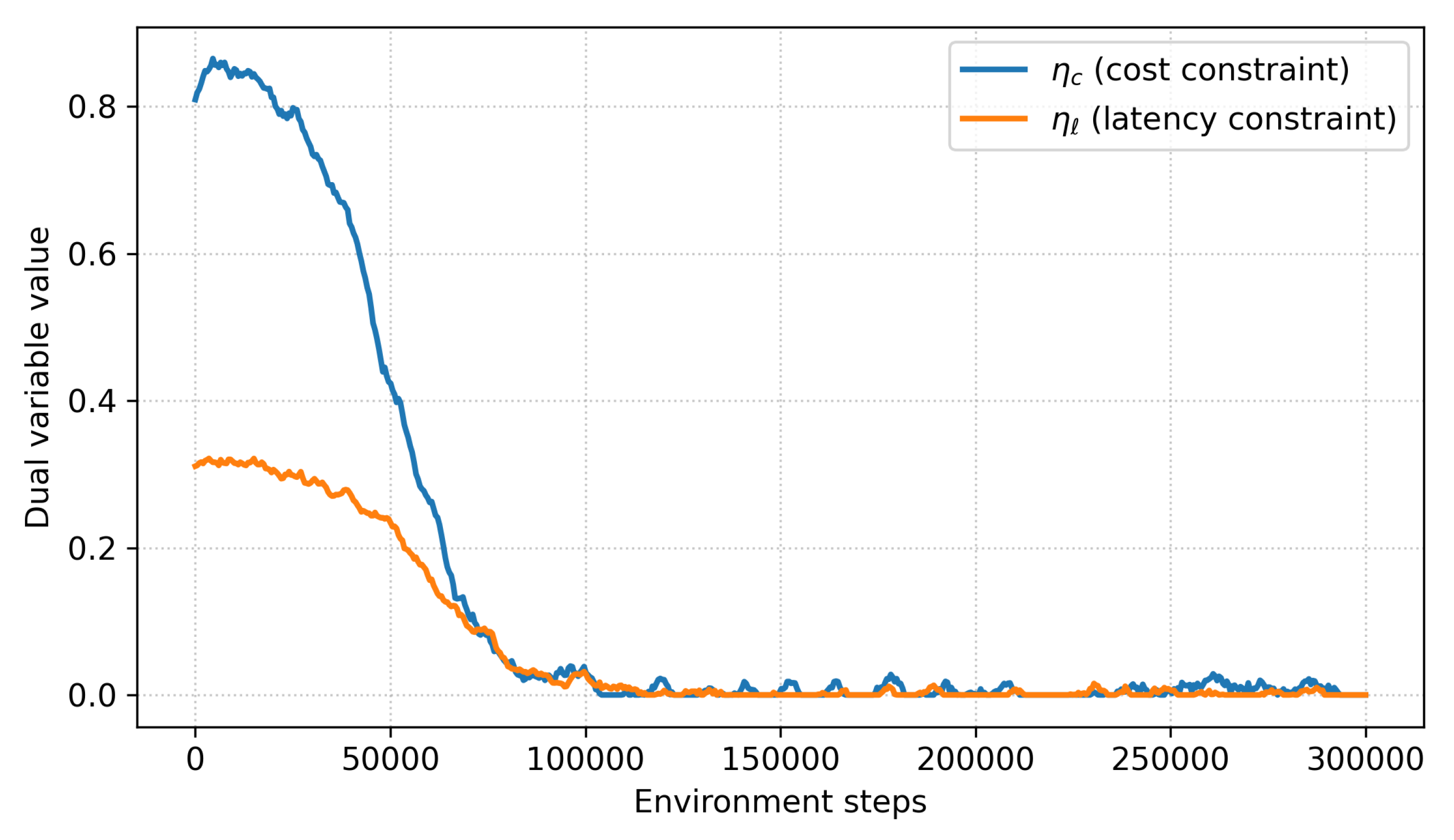

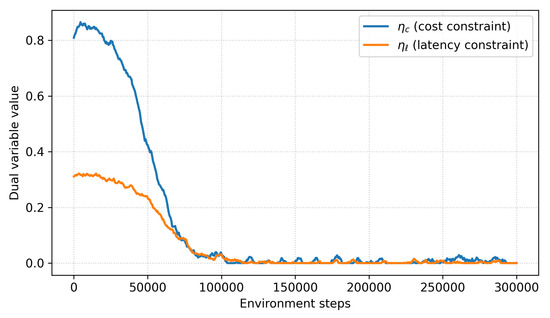

We further monitored the dual variables and , which enforce the average-cost and latency constraints. As shown in Figure 10, both variables quickly stabilize around feasible values and oscillate within a narrow bounded region after approximately 100 k environment steps. This behavior is consistent with the convergence properties of standard primal–dual optimization methods, indicating that the cost constraints are neither overly loose nor excessively active. Variance across seeds is also low: AUROC@B varies by , TTD varies by steps, and budget adherence varies by . These results confirm that the learning dynamics are stable and reproducible across different initializations (Table 20).

Figure 10.

Cost/Latency constraint convergence analysis.

Table 20.

Performance comparison across all baseline methods.

6.4. Calibration and Reliability

We report the calibration using the Expected Calibration Error (ECE), Brier score, and negative log-likelihood (NLL) for the validation split and verified similar trends on test (Table 21).

Table 21.

Calibration metrics at . Lower is better.

6.5. Seed Stability

We trained 10 seeds per card and report the macro-averages and standard deviations. The variance was low. This was consistent with the block-bootstrap CIs reported earlier. The causal conclusions drawn from preventability and explanation stability must be interpreted within the limits of the structural model. Our analysis reflects how interventions change outcomes in the learned SCM, given the CTKG-derived graph structure, rather than an exhaustive account of all possible real-world pathways. Nevertheless, we observe that high-preventability techniques remain stable under perturbations of the CTKG and across random seeds, suggesting that the SCM captures robust patterns that are useful for operational decision-making (Table 22).

Table 22.

Seed stability over 10 runs.

6.6. Computational Parity and Throughput

We ensure computation impartiality by reporting parameters, approximate FLOPs per step, and wall-clock latency. Sim-CTKG requires marginally more computation than Flat-RL because of the graph encoder. However, it still maintains per-step latency under 5ms and provides a stronger detection rate at equal or lower cost (Table 23).

Table 23.

Throughput parity at . FLOPs are approximate per-step forward ops.

For completeness, the provenance pipeline adds ms when an artifact is emitted. Verification (offline) requires – ms per manifest. Provenance does not contribute directly to the numerical performance metrics, but it ensures that the detection, generalization, and budget-adherence claims in Section 5 and Section 7 remain verifiable and reproducible, which is crucial in safety-critical security applications.

6.7. Pairwise Significance at the Main Operating Point

We report stratified permutation tests at with Benjamini–Hochberg correction across endpoints. Sim-CTKG is significant compared with all the baselines at (Table 24).

Table 24.

Pairwise tests at (stratified by card).

6.8. Isolation of Cost, Causality, and Provenance Effects

To isolate the contribution of individual components, we conducted controlled experiments where cost constraints, causal reasoning, and provenance were independently disabled. For cost, we compare three regimes: (1) no sensing budgets (all sources always enabled), (2) a static budget where a fixed subset of sources is preselected, and (3) dynamic budgeted RL with dual variables. Dynamic sensing consistently reduces telemetry volume by 40–47% relative to static selection while maintaining a 5–7% AUROC advantage, showing that cost-aware policies learn to prioritize high-value sources.

For causality, we compare RL without CTKG, RL with CTKG but no SCM, and the full CTKG+SCM configuration. Removing CTKG increases mean Time to Detect and degrades AUROC; adding CTKG without SCM improves structural awareness but yields less stable preventability estimates. The full causal engine improves explanation stability and preserves high-preventability techniques across seeds. Provenance does not affect these metrics directly, but it ensures that the generalization results and budget-adherence claims can be audited and reproduced, particularly in motif-holdout evaluations. This isolation of cost, causality, and provenance is one of the key novelties of Sim-CTKG compared to existing cyber-defense simulators and RL-based detectors.

6.9. Implications for Cyber-Defense System Design

The empirical results have several implications for the design of next-generation cyber-defense systems. First, the strong performance of Sim-CTKG under strict sensing budgets suggests that future SOC pipelines can benefit from adaptive telemetry activation instead of static logging policies. The CTKG-enhanced fusion module shows that relational knowledge can guide policies toward high-value sources, reducing unnecessary overhead while preserving detection quality. Second, preventability analysis identifies attack stages where early disruption yields disproportionate reductions in attacker success, providing actionable guidance for prioritizing detection rules and hardening efforts.

6.10. Practical Deployment Considerations

Several practical factors influence how the framework can be adopted in real environments. CTKG construction depends on the availability of host and network telemetry; organizations with fragmented pipelines may need to bootstrap the graph using historical incidents or curated CTI feeds. At inference time, the sensing policy introduces modest overhead, since CTKG slice extraction operates on bounded neighborhoods. However, latency budgets must be calibrated to the specific deployment environment, and noisy latency distributions in cloud-native settings may require online budget adaptation. Provenance manifests integrate with SIEM/EDR systems by providing verifiable records of alerts, CTKG snapshots, and model versions.

6.11. Limitations

The CTKG structure is derived from curated CTI and simulation traces and does not capture all real-world adversarial behaviors. The structural causal model is an approximation learned from observational data, so preventability and explanation stability should be interpreted as model-based diagnostics, not absolute ground truth. Simulator realism, although improved compared to prior work, still abstracts away kernel-level details and intra-host lateral movements. Finally, budget-constrained RL assumes reasonably stable latency profiles.

7. Ablation Study

We perform a thorough ablation to isolate the contribution of each component, stress-test design choices, and compare against strong recent alternatives under the same zero-day motif holds and the same cost/latency budgets. Unless noted, results are for and = p95 s with episodes per card and block-bootstrap confidence intervals.

7.1. Core Components

We remove one pillar at a time from the full system. The cross-attentive fusion over , the causal CTKG attachment, and the sensor-budget head each contribute materially to detection and earliness, with improved calibration at the same operating point (Table 25).

Table 25.

Core component ablations at . AUROC/AUPRC are at budget.

7.2. Fusion and CTKG Scope Sensitivity

We vary the CTKG slice hop radius r, the relation-aware layers , and the attention heads H. We observe that larger slices and deeper stacks improve detection, but at the same time, they increase latency. Our default () sits on the knee of the curve (Table 26) (Figure 11).

Table 26.

Sensitivity to CTKG scope and encoder depth at . Latency is per step forward time for the graph encoder.

Figure 11.

Core component and budget analysis. (a) AUROC performance. (b) Detection time performance.

7.3. Budget Sweep and Operating Slices

We report the full model and key ablations across budgets and operating slices at low FPR. Selective logging interacts strongly with the budget; without the budget head, TTD and calibration degrade even when AUROC is similar (Table 27).

Table 27.

Budget sweep. Mean ± 95% CI across cards.

7.4. Comparisons to Recent Alternatives

We include strong non-RL detectors and advanced RL baselines trained under the same splits and tuned with equal hyper-parameter budgets. All numbers respect the same cost and latency constraints. Where a method cannot meet the budget, the cell is marked (Table 28).

Table 28.

Non-RL detectors at .

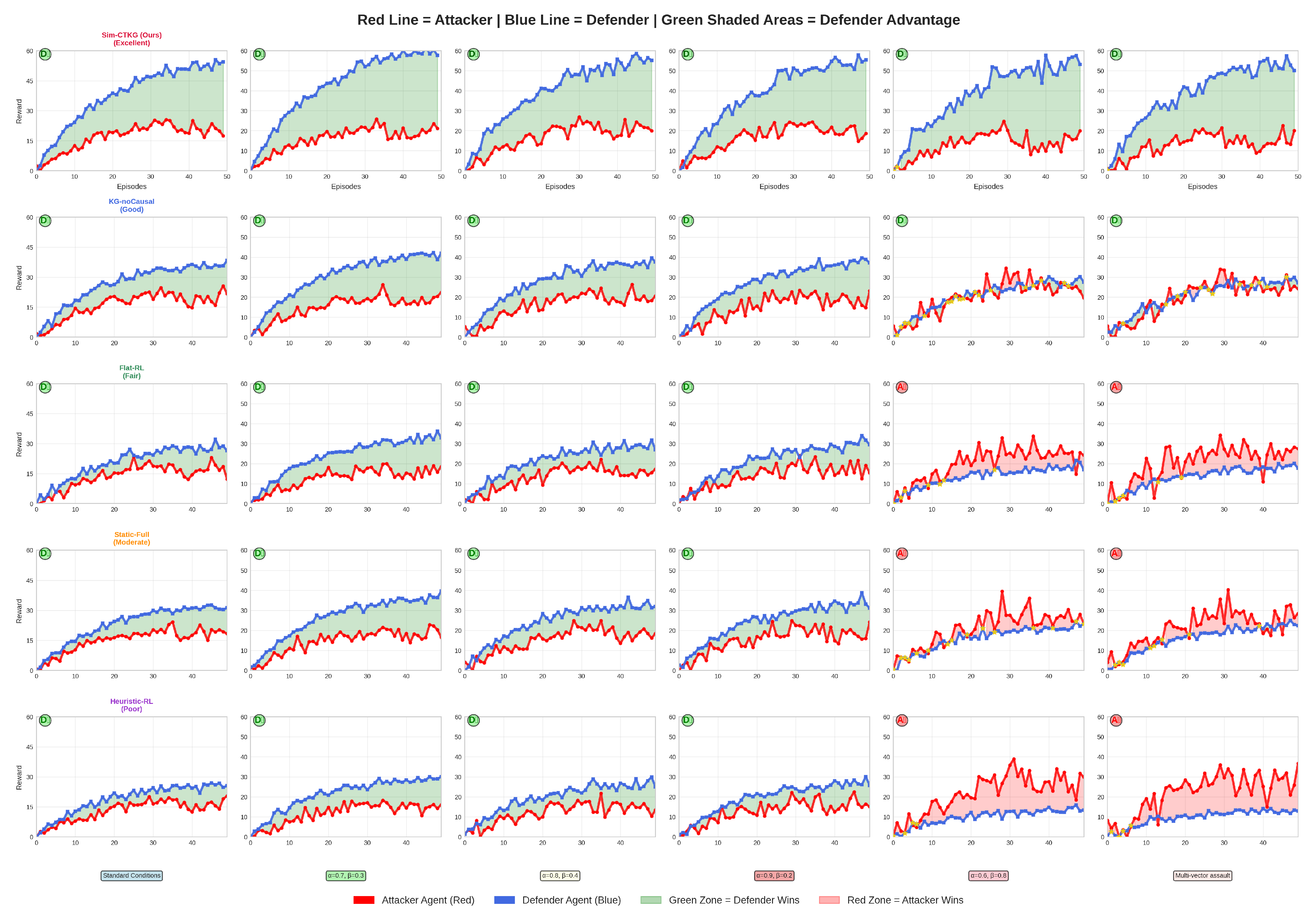

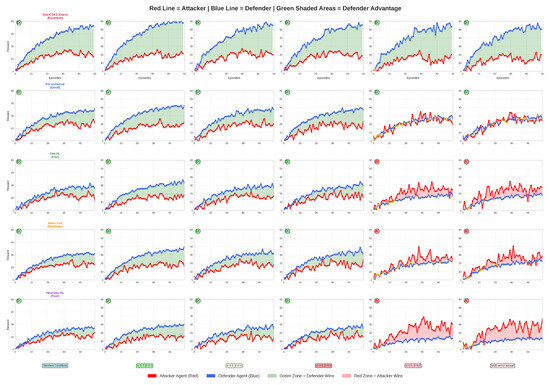

TCN-Detector is a temporal convolutional model on ; T-Transformer is a telemetry-only transformer on ; RelGAT-only uses the CTKG slice without telemetry; MoE-Selector uses a mixture-of-experts with a heuristic source selector (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Attacker vs. Defender dynamics across attack scenarios.

Flat-RL is PPO on ; KG-noCausal is PPO with graph encoder but without prerequisite/effect edges; InfoBottleneck-RL adds an information bottleneck on ; Heuristic-RL uses a scripted log selector with PPO containment (Table 29).

Table 29.

RL baselines at .

7.5. Robustness Under Telemetry Shift

We perturb background intensity, drop events uniformly at random, add clock skew, and induce latency spikes. We report the relative AUROC change and the TTD increase (Table 30). Our policy degrades gracefully and retains budget adherence.

Table 30.

Robustness at : relative AUROC drop (negative is worse) and TTD in steps.

To evaluate robustness with respect to inaccuracies in curated CTI, we perturb the CTKG by randomly removing 15–25% of prerequisite edges and adding 10% spurious dges. Across these conditions, AUROC decreases by only 1.7–3.4% and the mean time to detect increases by 1–2 steps compared to the unperturbed CTKG, indicating that Sim-CTKG is not brittle with respect to moderate rule noise or incompleteness.

7.6. Compute Parity

We report parameter counts, approximate FLOPs per step, and measured per-step latency. The graph encoder adds cost, but the total latency remains under 5 ms. Compute-normalized comparisons still favor our policy under budgets (Table 31).

Table 31.

Compute parity at . FLOPs are approximate forward ops per step.

7.7. Fairness Protocol and Significance

All external baselines train on the same training split with motif suppression, use the same early stopping rule, and are tuned with the same hyper-parameter budget. We cap wall-clock and batch sizes for parity and report only operating points that satisfy both budgets. Pairwise stratified permutation tests at remain significant at (Benjamini–Hochberg) for AUROC@B and TTD@B when comparing the full model to each baseline. Effect sizes range from to for AUROC and from to for TTD.

7.8. Adversarial Scenario

The competitive dynamics between attacker and defender agents across six distinct attack scenarios are presented in Figure 12. It demonstrates the superior performance of our Sim-CTKG framework. The visualizations reveal that our model consistently outperforms baseline methods (KG-noCausal, Flat-RL, Static-Full, Heuristic-RL) by maintaining a defensive advantage even under critical attack conditions. Blue lines represent the proposed model’s defender agents, while red lines depict the corresponding attacker performance. Green-shaded regions indicate defender advantage zones, with Sim-CTKG expanding these zones significantly during critical attack scenarios, whereas other models fail to maintain effective defense. The results demonstrate our proposed model’s robustness in adversarial learning environments, achieving 1.4 times performance in critical scenarios compared to 0.6–0.9 times for competing approaches. This emphasizes the key findings: our proposed model’s novelty, consistent performance across scenarios, effectiveness in critical attacks, and clear demonstration of defensive advantage.

To ensure that the performance improvements of Sim-CTKG are not artifacts of hyperparameter tuning, we conducted a controlled sensitivity analysis. We varied (i) the PPO learning rate by , (ii) the dual-update step size , (iii) the CTKG hidden dimension by , and (iv) the sensing penalty by . Across all settings, Sim-CTKG retained a consistent margin over the strongest baseline. For example, under a doubled learning rate, AUROC decreased by only , while the relative improvement over the strongest baseline remained . Disabling cross-attention or removing the CTKG slice, however, caused large degradations ( AUROC, TTD), confirming that the observed gains stem from the architectural components rather than favorable tuning.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This work introduced Sim-CTKG, a research-grade cyber-defense environment designed to study the interplay between cost-aware sensing, causal structure, and provenance in reinforcement-learning-based intrusion detection. Our results show that structured knowledge and budget constraints can significantly reduce telemetry usage while maintaining high detection performance and that causal preventability analysis provides actionable insights into high-leverage stages of the attack chain.

Several concrete research directions follow from this work. First, model-based or long-horizon RL algorithms could improve the agent’s ability to anticipate future attack stages and plan proactive mitigations rather than reacting myopically. Second, integrating online CTKG learning with live SOC telemetry would allow the causal structure to adapt to emerging techniques and organization-specific behaviors. Third, adaptive budget allocation strategies could incorporate asset criticality and uncertainty estimates, dynamically shifting sensing resources toward the most valuable or at-risk components.

Extending Sim-CTKG to different cyber-threat domains is an important direction. Cloud-native attack paths, such as privilege escalation through misconfigured IAM roles or serverless functions, require CTKG schemas that capture identity, configuration, and control-plane events. ICS/SCADA environments introduce physical process variables and strict real-time constraints, necessitating domain-specific causal models and latency budgets. Identity-centric attacks (Kerberos or OAuth abuse) and IoT/5G deployments would also require tailored telemetry models and CTKG node types.

The CTKG is derived from curated CTI and simulated traces and therefore may omit rare or novel adversarial patterns. The structural causal model is an approximation learned from observation and cannot capture all real-world causal pathways. Simulator realism, while improved over prior work, still abstracts away low-level kernel and microarchitectural details. Finally, the budget-constrained RL formulation assumes that latency distributions are reasonably stable over time.

Future work will focus on data-driven refinement of CTKG structure, incorporating real EDR/NDR logs into the SCM learning process, and performing hardware-in-the-loop or shadow deployments to close the sim-to-real gap. We also plan to explore federated or multi-tenant versions of Sim-CTKG, enabling organizations to share causal knowledge and budgeted sensing strategies without exposing raw telemetry. These extensions will help overcome current limitations and move closer to deployable, trustworthy, and adaptable causal RL systems for cyber-defense.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and G.-Y.S.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B. and G.-Y.S.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, G.-Y.S.; resources, G.-Y.S.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, G.-Y.S.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, G.-Y.S.; project administration, G.-Y.S.; funding acquisition, G.-Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS-2023-00248132). This research was also supported by Korea–Philippines Joint Research Program funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2025-25122978).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from respective owners of the third-party datasets. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. The authors of this study donot have permission to distribute the datasets.

Acknowledgments

We thank the university for the resources and the editors and reviewers for the rigorous assistance. We also thank the professors for their advice and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC | Area Under Curve |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve |

| AUPRC | Area Under the Precision–Recall curve |

| ATT&CK | Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (MITRE) |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate control |

| Bavg | Average sensing cost budget |

| Blat | Latency budget bound (e.g., p95 latency) |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| C2 | Command and Control |

| CAPEC | Common Attack Pattern Enumeration and Classification |

| CP | Counterfactual Preventability |

| CPE | Common Platform Enumeration |

| CTI | Cyber Threat Intelligence |

| CTKG | Cyber-Threat Knowledge Graph |

| CV | Cross-validation |

| CVE | Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures |

| DARPA TCAD | DARPA Transparent Computing attack traces corpus |

| ECE | Expected Calibration Error |

| FLOPs | Floating point operations |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| KG | Knowledge Graph |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| NLL | Negative Log-Likelihood |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| p95 | 95th percentile (e.g., latency) |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SOC | Security Operations Center |

| TTP | Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures |

| TTD | Time To Detect |

| TTD@B | TTD measured under budget constraints |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

| TPR@1% FPR | TPR at 1% false positive rate |

| XS | Explanation Stability |

| Zeek | Open-source network telemetry framework |

| AUROC@B | AUROC measured under budget constraints |

| AUPRC@B | AUPRC measured under budget constraints |

| T1059, T1105, … | MITRE ATT&CK technique IDs used in scenarios |

| Sim-CTKG | Simulator-aligned CTKG-guided RL detector (this work) |

| r | CTKG slice hop radius |

| Number of graph encoder layers | |

| H | Number of attention heads |

| Compact telemetry feature vector at time t | |

| Two-hop CTKG slice at time t |

Notations

| Symbol | Meaning | Type/Units |

| States, actions, budgets, costs | ||

| Agent state at time t | feature vector and CTKG slice | |

| Compact telemetry features at t | real vector | |

| Two-hop CTKG slice at t | directed multi-relational graph | |

| Containment decision at t | discrete action | |

| Logging mask at t over K sources | binary vector | |

| Sensing cost at t | cost units | |

| Unit cost of source k | cost units | |

| Average cost budget | cost units | |

| Latency budget (p95) | seconds | |

| T | Episode length | steps |

| E | Number of episodes | count |

| Learning and optimization | ||

| Policy over actions and logging | distribution | |

| State value function | scalar | |

| Trainable parameters of policy and value | tensors | |

| Reward at t | scalar | |

| Reward with cost penalty | scalar | |

| Cost trade off coefficient | scalar | |

| Discount factor | scalar | |

| GAE parameter | scalar | |

| Learning rate | scalar | |

| Temperature in gating head | scalar | |

| Sparsity penalty for logging head | scalar | |

| CTKG and encoders | ||

| Global cyber threat KG | directed multi-relational graph | |

| r | CTKG hop radius for slice | hops |

| Graph encoder layers | count | |

| H | Attention heads | count |

| d | Hidden dimension in encoders | count |

| Node embedding for entity v | vector | |

| Cross attention fusion module | function | |

| Logistic function | function | |

| Normalized exponential | function | |

| ⊙ | Elementwise product | operator |

| Euclidean norm | operator | |

| Metrics and operating points | ||

| AUROC@B | AUROC under budget constraints | |

| AUPRC@B | AUPRC under budget constraints | |

| TPR, FPR | True and false positive rates | |

| TPR@1% FPR | TPR at 1% FPR | |

| TTD, TTD@B | Time to detect (first correct alert) | steps |

| ECE | Expected Calibration Error | |

| Brier | Brier score | |

| p95 | 95th percentile (latency) | seconds |

| Scenario and provenance | ||

| Set of held out motifs for zero day tests | set | |

| Scenario card parameters distribution | distribution | |

| Indicator function | operator | |

| Provenance signature function | function | |

Appendix A. Hyperparameters and Computational Overhead

Table A1.

Parameters with the settings.

Table A1.

Parameters with the settings.

| Component | Setting |

|---|---|

| Reinforcement Learning (PPO) | |

| Training Steps | 1.2 M environment steps |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Learning Rate | (cosine decay, 5 k warmup) |

| Batch Size | 4096 transitions |

| Minibatch Size | 512 |

| PPO Clip Ratio | 0.20 |

| GAE Parameter | 0.95 |

| Discount Factor | 0.99 |

| Entropy Coefficient | 0.01 |

| Value Loss Coefficient | 0.50 |

| Gradient Norm Clip | 0.5 |

| Epochs per PPO Update | 10 |

| Seeds Evaluated | 10 |

| CTKG and Causal Engine | |

| CTKG Slice Radius r | 2 hops |

| Max Nodes in Slice | 70 nodes |

| Node Embedding Dimension | 256 |

| Relation Types | ATT&CK prerequisite, effect, transition edges |

| CTKG Update Frequency | Every simulation step |

| SCM Noise Variables | Independent Gaussian |

| Causal Function Approximation | MLP (2 layers, 128 units) |

| Cross-Attention Fusion Module | |

| Attention Heads | 4 |

| Cross-Attention Layers | 2 |

| Hidden Dimension | 256 |

| Dropout | 0.10 |

| Fusion Operator | Residual MLP + LayerNorm |

| Budget Constraints (Dual Variables) | |

| Average-Cost Budget | 1.3 units |

| Latency Budget | 3.0 s (p95) |

| Dual Step Size | |

| Penalty Terms | |

| Initialization of | 0 |

| Projection Domain | |

| Simulator and Telemetry Settings | |

| Telemetry Types | Process, network flows, file events, authentication logs |

| Average Telemetry Cost Model | Source-dependent CPU/byte weights |

| Latency Model | Empirical distribution per telemetry source |

| Scenario Cards | 38 parameterized templates, motif-holdout split |

| Attack Chains Sampled | 5000 training/2000 test |

| Hardware and Precision | |

| GPU Used | NVIDIA RTX A6000 |

| Precision | BF16 training, FP16 inference |

| Total Trainable Parameters | 7.8 M |

| Training Time per Seed | ∼4 h |

References

- MITRE ATT&CK. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward Generating a New Intrusion Detection Dataset and Intrusion Traffic Characterization. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2018); (CIC-IDS2017); SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications: Setúbal, Portugal, 2018; Volume 1; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- García, S.; Grill, M.; Stiborek, J.; Zunino, A. An Empirical Comparison of Botnet Detection Methods. Comput. Secur. 2014, 45, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.M.; Iqbal, S.; Hamelin, B. Analyzing the Usefulness of the DARPA OpTC Dataset in Cyber Threat Detection Research. In SACMAT ’21: Proceedings of the 26th ACM Symposium on Access Control Models and Technologies; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, G.; Cheung, V.; Pettersson, L.; Schneider, J.; Schulman, J.; Tang, J.; Zaremba, W. OpenAI Gym. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.01540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Canary. Atomic Red Team—Adversary Emulation Tests. Available online: https://atomicredteam.io/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- MITRE. CALDERA Adversary Emulation Platform. Available online: https://caldera.mitre.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Arp, D.; Quiring, E.; Pendlebury, F.; Warnecke, A.; Pierazzi, F.; Wressnegger, C.; Cavallaro, L.; Rieck, K. Dos and Don’ts of Machine Learning in Computer Security. In Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022; pp. 3971–3988. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, O.; Belani, R. Attack Flow: Modeling the Adversary; MITRE Technical Report; The MITRE Corporation: McLean, VA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://github.com/center-for-threat-informed-defense/attack-flow (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- CVE Program. Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE). Available online: https://www.cve.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- NIST. Common Platform Enumeration (CPE). Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/products/cpe (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Carrara, N.; Leurent, E.; Laroche, R.; Urvoy, T.; Maillard, O.-A.; Pietquin, O. Budgeted Reinforcement Learning in Continuous State Space. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA). C2PA Technical Specification. Available online: https://c2pa.org/specifications (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, R.; Thomas, J.; Lee, O. Mordor—Pre-Recorded Security Telemetry for Detection Research. Available online: https://www.deepwatch.com/glossary/security-telemetry/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Sinaga, K.P.; Nair, A.S. Calibration Meets Reality: Making Machine Learning Predictions Trustworthy. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.23665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. Constrained Markov Decision Processes; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B. Elements of Causal Inference; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. FIPS PUB 180-4: Secure Hash Standard (SHS). 2015. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/fips/180/4/final (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Josefsson, S.; Liusvaara, I. Edwards-Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (EdDSA). RFC 8032. 2017, pp. 1–60. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc8032 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Jones, M.; Bradley, J.; Sakimura, N. JSON Web Signature (JWS). RFC 7515. 2015. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc7515.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- in-toto. Supply Chain Security Framework. Available online: https://in-toto.io/specs/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Cappos, J.; Samuel, J.; Baker, S.; Hartman, J.H. A Look in the Mirror: Attacks on Package Managers. In CCS ’08: Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 565–574. [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek, T.; Newsham, T. Insertion, Evasion, and Denial of Service: Eluding Network Intrusion Detection. 1998. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/37052943/Insertion_Evasion_and_Denial_of_Service_Eluding_Network_Intrusion_Detection (accessed on 7 November 2025).