Abstract

This paper presents a state-based method to address the verification of -diagnosability and fault diagnosis of a finite-state vector discrete-event system (Vector DES) with partially observable state outputs due to limited sensors. Vector DES models consist of an arithmetic additive structure in both the state space and state transition function. This work offers a necessary and sufficient condition for verifying the -diagnosability of a finite-state Vector DES based on state sensor outputs, employing integer linear programming and the mathematical representation of a Vector DES. Predicates are employed to diagnose faults in a Vector DES online. Specifically, we use three different kinds of predicates to divide system state outputs into different subsets, and the fault occurrence in a system is detected by checking a subset of outputs. Online diagnosis is achieved via solving integer linear programming problems. The conclusions obtained in this work are explained by means of several examples.

1. Introduction

As discrete-event systems (DESs) grow increasingly complex, fault diagnosis becomes a challenging endeavor that cannot solely resort to trial-and-error or experience. Adopting a systematic approach is vital for efficiently addressing diagnostic challenges. Diagnosability in DESs, as studied in prior works [1,2], refers to the probability to detect a fault within a limited delay once it occurs. Fault detection acts as a monitoring mechanism, revealing potential faults by observing the behavior of a DES.

The formal definition of diagnosability for DESs is initially introduced in [3], where a fault detection method based on events is introduced for regular languages that are represented by finite-state machine (FSM) models [4]. Wonham and Lin [5,6] touch upon the supervisory control problem of partially observed FSMs. A diagnoser is constructed to detect a set of possibly occurring faults [3] or a collection of fault states that a system can reach [7] after an observed event. A diagnoser is used to extend the diagnosability concept to stochastic automata in [8] and to the decentralized case in [9,10]. A coordinated decentralized architecture consisting of local sites communicating with a coordinator that is responsible for diagnosing the failures occurring in a DES is proposed in [9]. The study in [10] presents a model-based technique for the diagnosis of large-scale active systems that are treated as distributed DESs with events being received asynchronously. In the literature, the diagnosability concept is extended to the centralized cases [11,12,13,14], to the decentralized cases [9,10,15], and to the distributed cases [16,17].

The problem of the verification of diagnosability has also been solved within the framework of Petri nets (PNs) [18,19] with two representations: graphical and mathematical. In [20], assuming that not every place of a PN is observable, every transition is unobservable, and a fault is represented by a transition, a diagnoser is constructed to verify the diagnosability of the system. One may determine whether a model is a member of a specified net subclass by the graphical representation of a PN. High-efficiency algorithms are developed for verifying the diagnosability of a specified PN subclass by investigating its peculiarity. Assuming that all places are not observable, the diagnosability of a PN is verified by constructing its diagnoser in [21]. The mathematical representation of a PN makes it possible to verify its diagnosability using common mathematical techniques like integer linear programming (ILP). The K-diagnosability of a PN is verified via ILP in [22]. An approach [23] using ILP achieves online diagnosis by recording observed transition sequences.

In general, only partial observation of events and states can be obtained since real systems have a limited number of sensors. Modeling faults as unobservable state transitions [20,24,25] or unobservable events [3,26] is one of the fault models that has been studied extensively. Fault diagnosers of DESs or PNs are constructed to verify the fault diagnosability or diagnose faults in some research based on states (i.e., state-based) [27,28], or markings in observed places [29,30]. In [27], a state-based methodology for fault diagnosis in a fully observable DES is introduced. This approach assumes a categorization of the system state set, distinguishing between failure and normal states. The objective of the diagnosis problem is to ascertain whether the current state is faulty or normal upon receiving the most recent observation.

Compared with traditional automata and PNs, a vector discrete-event system (Vector DES) offers greater flexibility. This structured model is particularly effective for representing systems with inherent additive structures, such as smart manufacturing systems. Vector DESs provide a modeling approach, particularly to systems that contain groups of entities with the same characteristics. When the internal system shares similar structural characteristics, it is logical to improve the model of an abstract automaton by leveraging its regularity in algebra. Compared to Petri nets (PNs), Vector DESs offer the advantage of more compact modeling. Within the framework of Vector DESs, PNs are simply used as a graphical tool for illustration, and the mathematical theory of PNs is not utilized [31,32,33,34,35]. This is because the primary aim of developing Vector DESs is to apply Ramadge–Wonham (R-W) methods to structured systems with vector addition. Moreover, since a state vector of a Vector DES is composed of integers, the definition of states becomes more flexible, and it is also crucial for the state feedback control [35]. An event-based approach to verifying the diagnosability property of Vector DES is presented in [31]. Particularly, predicates are proposed to partition system states into different subsets, based on which the fault diagnosability is verified.

This research investigates the problem of state-based -diagnosability analysis and state-based fault diagnosis in a finite-state Vector DES, particularly in scenarios where sensors are embedded within specific state components. The idea of this paper is generated to characterize all the state output sequences corresponding to an event sequence , where v sustains the system evolution after the fault occurs, while u enables a fault from the initial state. The following is a summary of this work’s primary contributions.

- 1.

- We first investigate and formulate the definition of the state-based -diagnosability in a Vector DES. For the verification of state-based -diagnosability, a necessary and sufficient condition is introduced.

- 2.

- A standard mathematical tool is utilized to verify state-based -diagnosability and diagnose, preventing a full state enumeration. The presented method does not depend on the construction of a diagnoser, because it solves ILP problems to verify the state-based -diagnosability and achieve online diagnosis.

The rest of this paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 provides the preliminaries on system models. Section 3 describes the problem statement, together with the definitions of the state-based diagnosability and state-based -diagnosability. For the verification of state-based -diagnosability, a necessary and sufficient condition is introduced in Section 4. Section 5 develops an algorithm to achieve online diagnosis. An example of a production line repairing damaged parts is presented to illustrate the proposed methods in Section 6. In the end, conclusions are provided in Section 7.

2. Preliminaries

A DES plant is a generator , where D stands for the state set, for the alphabet, : for the (partial) transition function, for the initial state, and for the marker state set. and are used to represent the set of all finite sequences of symbols defined over and the Kleene closure of , respectively, i.e., , where , and is the empty sequence [35]. An element is called a string, with representing the length of w. Given , we follow the notations in [35], and use to represent that the transition is defined. The closed behavior of G is

and the marked behavior is

Given a DES G, a state is reachable if there exists a string such that and . For any state ,

Define

The space of n-vectors (i.e., ordered n-tuples) with components in (resp., ) is represented by (resp., ), where and stand for the sets of integers and natural numbers, respectively. The “direct sum” operation ⨁ is used to form structures similar to or . A Vector DES [33,34,35] is defined as , but with a vector structure. Generally speaking, , while : satisfies the following form:

where and . Let and write for . Define

as the displacement matrix for G. Let represent the size of state set.

Let represent the column of E corresponding to event . Define

where is the number of occurrences of in w. A more general definition of a Vector DES would add the following enabling conditions. Assume . Given and , let , , where . Define

and

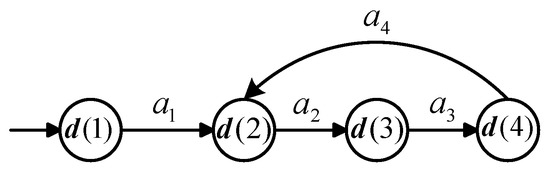

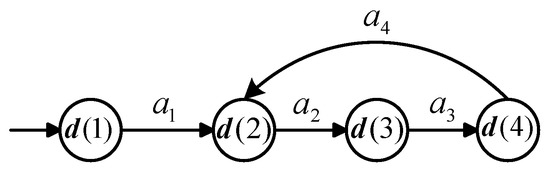

Example 1.

Consider a Vector DES in Figure 1, where the state vector is , alphabet is , and the initial state is .

Figure 1.

Vector DES model in Example 1.

Table 1.

All states of Vector DES G in Example 1.

Consider a Vector DES . A predicate P, as defined in [33,34], operates on and is represented as a function . In essence, P can be viewed as denoting the corresponding state subset associated with it, i.e.,

is often written as (“ satisfies P”). For the Vector DES G presented in Example 1, a predicate P can be defined as

or equivalently,

3. Problem Formulation

States and events may be partially observable in a real system that can be modeled by a Vector DES. This paper considers the scenario in which all events of a Vector DES are unobservable and the states are partially observable. Alternatively, this setup implies that sensors are solely equipped in specific components of a state, which has been studied in the framework of state-based partially observed automata [27,36]. Consider a Vector DES designated for diagnosis, modeled as a reachable deterministic finite-state Moore automaton . Here, , , and represent the finite state, event, and output sets, respectively. The notation denotes the initial state, stands for the transition function, and : is defined as the output map [27] (this output map can be formulated by taking into account the requirements of a specific physical system). Formally, suppose that a state ’s component elements are separated into two sets: observable components set and unobservable components set , and .

We shall concentrate on the diagnosability and diagnosis of a single fault instead of the diagnosability and diagnosis of a type of fault without sacrificing generality. Set can be classified into a normal state subset and faulty state subset including the states that are reachable from via a fault event represented by .

Definition 1

(Output projection). Given a Vector DES , , and , the output projection is defined as

The output projection just “erases” the unobservable state components of a state.

Example 2.

Continuing to Example 1, we briefly explain the output projection as follows. Assume . For instance, given , it comes .

Definition 2.

Given a Vector DES , a vector is called an E-invariant if .

Similar to the definition of the support of a T-invariant in net theory [22], we define the support of an E-invariant as the set of events that corresponds to entries of that are not zero. If no suitable nonempty subset of a support can be a support, then the support is considered as being minimal. stands for the set of minimal support E-invariants of .

In this work, the output map is defined as the output projection and : . From now on, let us write a reachable nondeterministic finite-state Moore automaton in place of . We adopt the following assumptions in the remainder of the paper.

Assumption 1.

The state set of a Vector DES can be classified according to the condition (normal or failure) of the system.

Assumption 2.

The system is deadlock-free, i.e., !

Assumption 3.

The fault modes are permanent, i.e., the system stays in the faulty condition indefinitely after a fault occurs.

Assumption 4.

The initial state is unique.

The notion of diagnosability guarantees that, upon the occurrence of a fault in a system, it must be detected within a limited delay. The formal descriptions of state-based diagnosability and state-based -diagnosability are presented in what follows.

Definition 3.

Given a Vector DES and a fault , is state-based diagnosable if

where represents the set of all state estimations provided after v events occurring from .

Let be any faulty state. Condition (12) indicates that there exists such that, once , the set of all state estimations provided after v events occurring from is the subset of the faulty state subset .

Definition 4.

Given a Vector DES , a fault , and , is state-based -diagnosable if

where represents the set of all state estimations provided after v events occurring from .

The notion of -diagnosability provides a means to specify an upper limit on the number of events required to detect a fault. If a system is considered to be state-based -diagnosable, it implies that the system is also state-based diagnosable. However, the converse is not necessarily true. According to Definitions 3 and 4, if a system is state-based diagnosable, then there exists another integer value for which the system is also state-based -diagnosable.

The fault detection problem discussed in this work employs a sequence of state output ) to determine the condition of a Vector DES. It should be noted that it is assumed that just alterations in the output are observable. It indicates that, if the system goes from one state to another state with an identical state output, such transition will be unnoticed, i.e., the transition is not observable. In an output sequence, for . Given an output , an upper limit for the number of states corresponding to the output is given by , which can be computed by Netlab [37]. For instance, in Example 2, we can obtain that , implying that one state output corresponds to up to two system states.

Given a finite-state Vector DES and a fault , our goal is to realize the online diagnosis of a Vector DES by checking the subsets of states. When a new state output is generated, whether the faults occurred can be derived, the system can be in only one of the following states: normal, faulty, and uncertain. Enhancing the fault detection algorithm’s efficiency can be achieved at the expense of a slight rise in memory usage. Therefore, we just record the current state output. Of course, if we record the complete state output sequence, there will be a more accurate diagnosis decision. We need to find a specific predicate for a Vector DES such that, if a current state output satisfies this specific predicate, we can detect the fault. The primary issues to be investigated in this work are presented as follows.

Problem 1.

Given a finite-state Vector DES , , , , and a fault , verify the state-based -diagnosability of G via solving an ILP problem.

Problem 2.

Given a finite-state Vector DES , , , and a fault , find a predicate P for G such that, if the current state output of the system satisfies P, one can determine the occurrence of .

4. Verification of State-Based -Diagnosability

4.1. Necessary and Sufficient Condition for State-Based -Diagnosability of Finite-State Vector DESs

The primary outcome discussed in this section is to provide a necessary and sufficient condition for state-based -diagnosability of a fault in a Vector DES. This condition is established as the solution to an ILP problem. Prior to introducing Lemma 1, a brief review of fundamental Petri net concepts and additional notations is provided.

A Petri net (PN) is a four-tuple , where is a finite set of places, T is a finite set of transitions, Pre, and Post. A marking of a PN is a vector : . For further information on the fundamental concepts of PNs, the reader is directed to [22].

Lemma 1

([38]). Given a PN with a marking and a sequence , there exists a set of ρ non-negative integer vectors with such that the linear constraints listed below are satisfied

if and only if σ is enabled at the marking .

A finite-length transition sequence that is enabled at a marking in a PN must meet the necessary and sufficient condition given by Lemma 1. Based on Lemma 1, Lemma 2 is presented.

Lemma 2.

Given a finite-state Vector DES and , an output sequence is generated at the initial state , if and only if there exist vectors that satisfy the set of constraints listed below, represented by ,

Proof of Lemma 2.

(if) Since one state output corresponds to up to system states, there are at most events between states. By Lemma 1, if there exist vectors satisfying constraints (15) (a), then at least one event sequence is generated from the initial state with the output . Constraints (15) (b) have the same meaning as constraints (15) (a). Therefore, if there exist vectors satisfying constraints , an output sequence is generated at the initial state .

(only if) Let us suppose that an output sequence is generated at the initial state . According to Lemma 1, there exist vectors corresponding to an event sequence yielding the output sequence starting from the initial state , such that constraints (15) (a), (b), and (c) are satisfied. □

Theorem 1.

Consider a finite-state Vector DES , , and a fault . Let be a positive integer such that (Implicitly, the value of establishes the longest event sequence that can provide a generic state that enables . In [22], the minimum is presented to fully describe all states reachable from that enable , and these states are reached via a sequence not including . The system is supposed to be finite-state, which implies that the integer exists. An overestimation of [22] is given by . Given an integer that is positive, is state-based -diagnosable if and only if there exist vectors , , such that

where the set of constraints is given in (16):

Proof of Theorem 1.

(if) By , the constraints (16) (a) describe all states reachable from that enable fault event . It follows that, if there exist vectors , , fulfilling constraints (16) and

then every faulty event sequence with of an output sequence includes the fault event , such that there are at least events in the postfix following the fault . Therefore, is state-based -diagnosable according to Definition 4.

(only if) Let us suppose that is state-based -diagnosable. According to Definition 4, for each state estimation , which is provided after sufficient steps of state transition from , if , then the fault can be accurately identified in a limited delay.

Now, let us assume ad absurdum that

Then, there should exist at least one output sequence and the corresponding event sequences that are with and not containing , such that . This implies that is not state-based -diagnosable, which contradicts that is state-based -diagnosable. □

The constraint (16) (b) will return the occurrence vectors of an event sequence generating the same output sequence with .

For a huge value of , being state-based -diagnosable could imply being practically undiagnosable. In practice, being state-based -diagnosable for is essential when the number of states is high. Utilizing Theorem 1, the minimal required for a diagnosable fault to be state-based -diagnosable can be calculated by conducting a binary search on , beginning at .

4.2. Illustrative Example

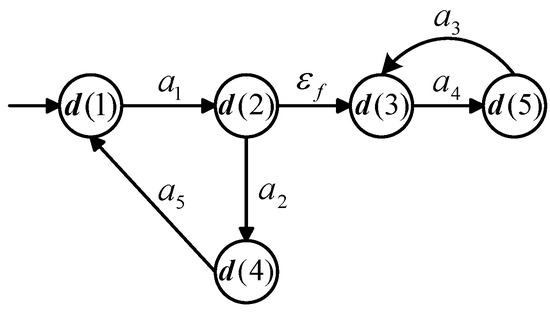

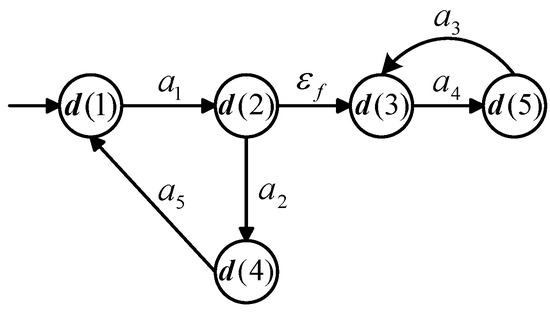

Example 3.

Consider a Vector DES G visualized in Figure 2 with alphabet , where represents the fault. The state vector is defined as . , and . The initial state is . Displacement matrix and are given as follows:

Figure 2.

Vector DES model in Example 3.

All states of G are listed in Table 2. In this system, and . We solve an ILP problem and a full state enumeration is avoided. The is calculated using Netlab software 1.75 and it equals 5. We set and . If we select , then

where the set of constraints is given in (17):

If we select , then

Therefore, is state-based 1-diagnosable. We have validated this result by employing the YALMIP software tool R20180612 [39] to solve the ILP problem.

Table 2.

All states of Vector DES G in Example 3.

4.3. Complexity Analysis

The primary computational burden of the proposed method lies in solving Equation (16), which can be reformulated as an ILP model. It is widely acknowledged that ILP problems are generally NP-hard. Notably, the computational complexity of solving an ILP problem is heavily influenced by the number of constraints and variables involved. Assuming that is provided, it is easy to deduce that (16) (a) contains variables, while (16) (a) contains constraints. The number of variables in (16) (b) is , while that of constraints in (16) (b) is . The total number of variables in (16) is , while the total number of constraints is . Furthermore, if and are given, regardless of the initial state, the numbers of constraints and variables rise linearly with the size of a Vector DES.

5. State-Based Fault Online Diagnosis

5.1. State-Based Fault Online Diagnosis of Finite-State Vector DESs

For online diagnosis, the current condition of a system is determined by the recorded state output. We do not rely on a diagnoser-based approach to achieve online diagnosis. The following predicates are presented to divide the outputs of current states based on the condition of a system.

Definition 5

(Faulty predicate ). Given a Vector DES , , and a fault , the faulty predicate with regard to G identifies a state subset by defining

or equivalently,

The following provides an illustration of the definition of faulty predicate . Given a state output satisfying , all states in the set of estimation are reachable via the sequences containing a fault, and the current condition of is faulty.

Definition 6

(Normal predicate ). Given a Vector DES , , and a fault , the normal predicate with regard to G identifies a state subset by defining

or equivalently,

The following provides an illustration of the definition of normal predicate . Given a state output satisfying , all states in the set of estimation are reachable via the sequences not containing a fault, and the current condition of is normal.

Definition 7

(Uncertain predicate ). Given a Vector DES , , and a fault , the uncertain predicate with regard to G identifies a state subset by defining

or equivalently,

For any state output , there exist at least two states with the identical observation, such that is reachable via a sequence containing a fault, and is reachable via a sequence not containing a fault. The current condition of is uncertain.

Example 4.

For Example 3, if is observed, the corresponding state estimation set is . Each state in this set is reachable via the sequences containing a fault and satisfies , implying that a fault occurs.

Proposition 1.

Given a finite-state Vector DES , , a fault , and the current state output , if and only if there exist ρ vectors , such that

where the set of constraints is given in (18):

Proof of Proposition 1.

(if) By Lemma 1, if there exist vectors satisfying constraints (18) (a), then at least one event sequence is generated from the initial state . Suppose that there exist vectors , such that , which implies that any state in the state estimation set of according to the constraint (18) (b) is reachable via fault . By Definition 5, and the fault occurs.

(only if) Assume . It follows that, by Definition 5, all states in the set of estimation of are reachable via sequences containing a fault.

Now, let us assume ad absurdum that

Then, there should exist at least one state in the state estimation set of that is reachable not via fault . This implies that does not satisfy , which contradicts that . □

Proposition 2.

Given a finite-state Vector DES , , a fault , and the current state output , if and only if there exist ρ vectors , such that

where the set of constraints is presented in (19):

Proof of Proposition 2.

(if) By Lemma 1, if there exist vectors satisfying constraints (19) (a), then at least one event sequence is generated from the initial state . Suppose that there exist vectors , such that , which implies that any state in the state estimation set of according to the constraint (19) (b) is reachable not via fault . By Definition 6, and the fault does not occur.

(only if) Assume . It follows that, by Definition 6, all states in the set of estimation of are reachable via sequences not containing a fault.

Now, let us assume ad absurdum that

Then, there should exist at least one state in the state estimation set of that is reachable via fault . This implies that does not satisfy , which contradicts that . □

Proposition 3.

Given a finite-state Vector DES , , a fault , and the current state output , if and only if there exist vectors , such that

where the set of constraints is given in (20):

Proof of Proposition 3.

(if) By Lemma 1, if there exist vectors , satisfying constraints (20) (a) and (b), then at least one event sequence is generated from the initial state . Suppose that there exist vectors , such that . Then, there exist two states with the same state output according to constraints (20) (d), for which one state is not generated via a fault but another is generated via at least one fault according to the constraint (20) (c). By Definition 7, and the system condition is uncertain.

(only if) Assume . It follows that, by Definition 7, for any state in the state estimation set of , there exists another state such that these two states have the same output . However, is reachable via a sequence containing a fault, and is reachable via a sequence not containing a fault.

Now, let us assume ad absurdum that

Then, each state in the state estimation set of is reachable via fault . This implies that does not satisfy , which contradicts that . □

Proposition 4.

Given a finite-state Vector DES , , and a fault , the upper bounds of ρ and λ satisfy

Proof of Proposition 4.

Denote by the longest sequence. In a finite-state Vector DES , the length of can be arbitrarily long. Here, we just need to compare the projections of states. The states of are finite, whose number is . The farthest state can be reached from via by the occurrence of the maximum number of events without reaching two times the same intermediate state. covers all minimal support E-invariants. Therefore, the length of is less than , i.e., and are less than . □

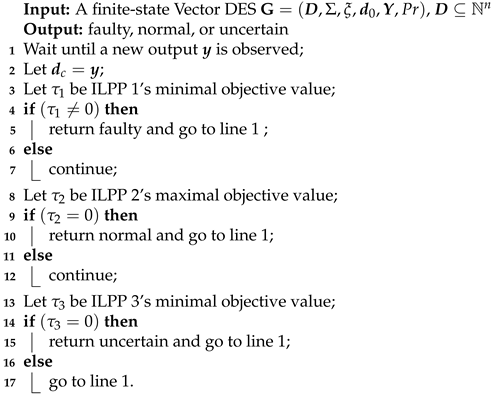

Now, an online procedure for Problem 2 is ready to be developed. The basic procedures for performing state-based diagnosis in a finite-state Vector DES using the ILP approach only are outlined in Algorithm 1, where is guaranteed to be correct by Propositions 1–4.

| Algorithm 1: State-based online fault diagnosis of a finite-state Vector DES |

|

5.2. Illustrative Example

Example 5.

Consider the Vector DES G presented in Example 3. The variable is calculated with Netlab software 1.75 and it equals 5. Then, the minimal support E-invariants are calculated with Netlab: , .

Proposition 4 gives the upper bounds of ρ and λ, i.e.,

Before applying Algorithm 1 to the Vector DES G, the corresponding ILPPs 1, 2, and 3 are obtained as follows.

where the set of constraints is given in (22):

where the set of constraints is presented in (23):

where the set of constraints is given in (24):

When is observed, the output of Algorithm 1 is “normal”. When is observed, the output of Algorithm 1 is “faulty”.

5.3. Complexity Analysis

The solutions to ILPPs 1, 2, and 3 are the primary source of Algorithm 1’s computational expense. An ILP problem is believed to be NP-hard in general. Let us assume that and are given; it is easy to deduce that ILPP 1 contains variables, while ILPP 1 contains constraints. ILPP 2 contains variables, while ILPP 2 contains constraints. ILPP 3 contains variables, while ILPP 3 contains constraints.

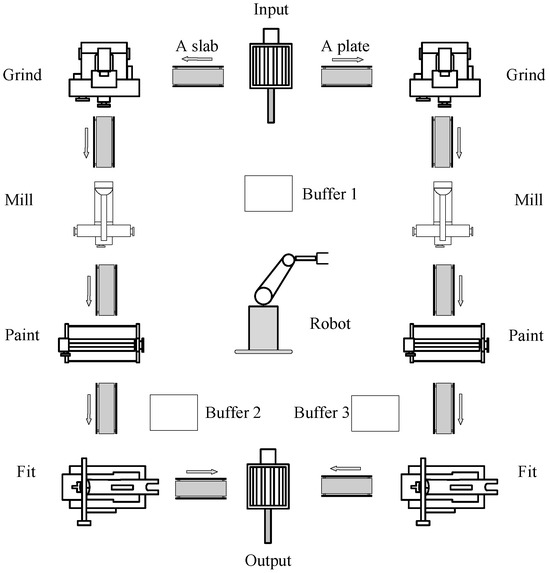

6. Example: A Production Line Repairing Damaged Parts

Consider a production line repairing damaged parts as shown in Figure 3, namely metallic slabs where a plate and a slab have been placed in decentralized positions. The production line consists of two lines, and each line consists of four parts, i.e., a numerically controlled grinding machine, a numerically controlled milling machine, a painting machine, and a numerically controlled fitter. Slabs and plates are separated when a damaged metallic slab is ready for repair, with the slab going in the left line and the plate in the right. Parts are fixed in the two lines consisting of ground, milled, painting, and fitted. Ultimately, the robot correctly positions a single metallic plate in the slab. The whole process is repeated. A new damaged metallic slab enters the production line as input. Slabs and plates are separated when a new damaged metallic slab is ready for repair, with the slab going in the left line and the plate in the right.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the production line repairing damaged parts.

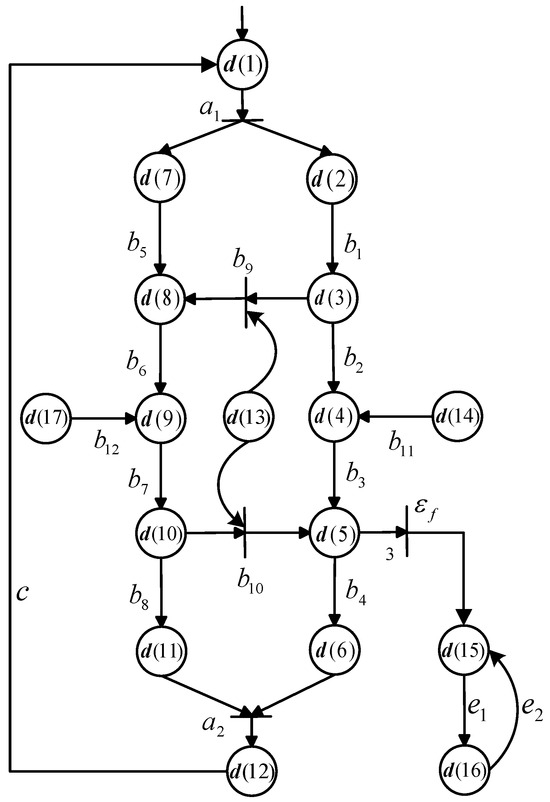

The Vector DES model of the production line is visualized in Figure 4, where the meanings of events and state components are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. We define the state vector as , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , and . , , , , , , , , , , , , , , c, , , , where represents the fault. The initial state is , 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, .

Figure 4.

A Vector DES model of the production line repairing damaged parts in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Event of Figure 4.

Table 4.

State component of Figure 4.

The Vector DES model of the production line is finite-state and has a total of 1149 states, which has been successfully verified by Netlab. We set and . If we select , then

where the set of constraints is given in (25):

Therefore, is state-based 1-diagnosable.

Then, the minimal support E-invariants are calculated with Netlab:

,

.

Proposition 4 gives the upper bounds of and , i.e.,

Before applying Algorithm 1 to the Vector DES model of the production line, the corresponding ILPPs 1, 2, and 3 are obtained as follows.

where the set of constraints is given in (26):

where the set of constraints is presented in (27):

where the set of constraints is given in (28):

When is observed, the output of Algorithm 1 is “normal”. We have validated these results by employing the YALMIP software tool to solve the ILP problems.

7. Conclusions

This paper addresses a state-based approach to solving the problems of the verification of -diagnosability and online diagnosis of a Vector DES by formulating and solving ILP problems. A necessary and sufficient condition for verifying -diagnosability of a finite-state Vector DES is presented. Several ILP problems are built according to a state output. The online diagnosis result is obtained by giving distinct objective functions to the ILP problem. The proposed approach requires neither any search of paths in graphs nor any estimation of the reachability set. By changing the structure of input of the Vector DES to the suggested ILP problems, it can therefore be applied to other Vector DESs. In future work, we will optimize parameters , , and of the ILP problems to make the procedure more efficient.

Author Contributions

Methodology, formal analysis, software, writing—original draft preparation, Q.C.; supervision, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L. and M.G.; funding acquisition and programming, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to King Saud University for funding this work through Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R1056), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DES | Discrete-event system |

| FSM | Finite-state machine |

| PN | Petri net |

| ILP | Integer linear programming |

| ILPP | Integer linear programming problem |

References

- Cassandras, C.G.; Lafortune, S. Introduction to Discrete Event Systems, 2nd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zaytoon, J.; Lafortune, S. Overview of fault diagnosis methods for discrete event systems. Annu. Rev. Control 2013, 37, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, M.; Sengupta, R.; Lafortune, S.; Sinnamohideen, K.; Teneketzis, D. Diagnosability of discrete-event system. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1995, 40, 1555–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, M.; Sengupta, R.; Lafortune, S.; Sinnamohideen, K.; Teneketzis, D. Failure diagnosis using discrete event models. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 1996, 4, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Wonham, W.M. On observability of discrete-event systems. Inf. Sci. 1988, 44, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F. Diagnosability of discrete event systems and its applications. Discret. Event Dyn. Syst. 1994, 4, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zad, S.H.; Kwong, R.H.; Wonham, W.M. Diagnosis in discrete-event systems: Incorporating timing information. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Lunze, J.; Schroder, J. State observation and diagnosis of discrete-event systems described by stochastic automata. Discret. Event Dyn. Syst. 2001, 11, 319–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debouk, R.; Lafortune, S.; Teneketzis, D. Coordinated decentralized protocols for failure diagnosis of discrete-event systems. Discret. Event Dyn. Syst. 2000, 10, 33–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, P.; Lamperti, G.; Pogliano, P.; Zanella, M. Diagnosis of a class of distributed discrete-event systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2000, 30, 731–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.; Hou, Y.; Liu, D. Sensor network attack synthesis against fault diagnosis of discrete event systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoli, A.; Lafortune, S. Safe diagnosability for fault-tolerant supervision of discrete-event systems. Automatica 2005, 41, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, D.; Delherm, C. Diagnosis of DES with Petri net models. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2007, 4, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotoli, M.; Fanti, M.P.; Mangini, A.M.; Ukovich, W. On-line fault detection in discrete event systems by Petri nets and integer linear programming. Automatica 2009, 45, 2665–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Fanti, M.P.; Mangini, A.M.; Li, Z. Decentralized diagnosis by Petri nets and integer linear programming. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 48, 1689–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Wonham, W.M. Global and local consistencies in distributed fault diagnosis for discrete-event systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Wonham, W.M. Hierarchical fault diagnosis for discrete-event systems under global consistency. Discret. Event Dyn. Syst. 2006, 16, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, R.; Yuan, Z. Anomaly detection in discrete manufacturing systems by pattern relation table approaches. Sensors 2020, 20, 5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, H.; Ding, W.; Xu, L.; Ruan, C. Petri-Net-based charging scheduling optimization in rechargeable sensor networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushio, T.; Onishi, L.; Okuda, K. Fault detection based on Petri net models with faulty behaviors. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, San Diego, CA, USA, 11–14 October 1998; pp. 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cabasino, M.; Giua, A.; Lafortune, S.; Seatzu, C. Diagnosability analysis of unbounded Petri nets. In Proceedings of the 48th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Shanghai, China, 16–18 December 2009; pp. 1267–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, F.; Chiacchio, P.; Tommasi, G.D. On K-diagnosability of Petri nets via integer linear programming. Automatica 2012, 48, 2047–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, D. On-line fault diagnosis with partially observed Petri nets. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2014, 59, 1919–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.L. Diagnosing PN-based models with partial observable transitions. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2005, 18, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T.S.; Lafortune, S. Polynomial-time verification of diagnosability of partially observed discrete-event systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2002, 47, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Feng, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, N. An Efficient fault diagnosis approach based on integer linear programming for labeled Petri nets. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 66, 2393–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zad, S.H.; Kwong, R.H.; Wonham, W.M. Fault diagnosis in discrete-event systems: Framework and model reduction. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2003, 48, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. State-based fault diagnosis of discrete-event systems with partially observable outputs. Inf. Sci. 2020, 529, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Jeng, M. Diagnosability analysis based on T-invariants of Petri nets. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Networking, Sensing and Control, Tucson, AZ, USA, 19–22 March 2005; pp. 371–376. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Li, Z.; Wu, N. Model-based fault identification of discrete event systems using partially observed Petri nets. Automatica 2018, 96, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yin, L.; Wu, N.; El-Meligy, M.A.; Sharaf, M.A.F.; Li, Z. Diagnosability of vector discrete-event systems using predicates. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 147143–147155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Chang, R.; Nan, X. On the invariance property of reduced supervisors from the perspective of vector discrete-event systems. Int. J. Control 2021, 94, 2541–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wonham, W.M. Control of vector discrete-event systems I—The base model. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1993, 38, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wonham, W.M. Control of vector discrete-event systems II—Controller synthesis. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1994, 39, 512–531. [Google Scholar]

- Wonham, W.M.; Cai, K. Supervisory Control of Discrete-Event Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Qiu, D. State-based fault diagnosis of discrete-event systems. In Proceedings of the 28th Chinese Control and Decision Conference, Xuzhou, China, 26–28 May 2016; pp. 5470–5475. [Google Scholar]

- Petrinet-Tool Netlab. Available online: https://www.irt.rwth-aachen.de/cms/irt/studium/downloads/~osru/petrinetz-tool-netlab/?lidx=1 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Vallés, F.G. Contributions to the Structural and Symbolic Analysis of Place/Transition Nets with Applications to Flexible Manufacturing Systems and Asynchronous Circuits. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Löfberg, J. YALMIP: A toolbox for modeling and optimization in MATLAB. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26 April–1 May 2004; pp. 284–289. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).