Abstract

Excessive swing of the cantilevered conveyor trough is a key issue restricting the working efficiency and operational stability of combine harvesters. To suppress its swing, this study established a dynamic model of the conveyor trough to reveal the influence mechanisms of the initial angle, overall length, and cylinder pivot length on its swing characteristics. Orthogonal experimental design and multi-factor analysis of variance were employed to systematically analyze the significance of these three factors on swing amplitude, identifying cylinder pivot length as the most dominant factor. Optimization results determined the optimal parameter combination as an initial angle of 48.33°, an overall length of 1.45 m, and a cylinder pivot length of 1.1 m. Field tests verified that this optimized scheme reduces the swing amplitude by 11.62%, with a minimal error of 0.57% between theoretical and measured values, providing a reliable theoretical and experimental basis for the low-vibration design of combine harvester conveying mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Rice combine harvesters represent pivotal machinery in modern agricultural production, where operational stability and efficiency directly determine grain harvest quality and yield [1,2,3,4]. As the critical transfer component linking the header and threshing unit, the cantilevered conveyor trough plays a decisive role in overall machine stability [5,6,7]. However, complex and variable field operating conditions subject the header to impact loads that propagate trough the cantilevered conveyor trough, inducing severe sway [8,9,10,11]. This phenomenon not only accelerates structural fatigue and compromises operator comfort but also risks material blockage and increases grain entrainment loss [12,13]. Consequently, in-depth investigation of the dynamic characteristics of the cantilevered conveyor trough, coupled with structural parameter optimization to suppress detrimental vibrations, holds significant theoretical and engineering value for enhancing combine harvester performance [14,15,16,17].

Scholars worldwide have explored vibration issues in conveying systems from multiple perspectives [18,19,20,21]. Regarding mechanism analysis and testing, Cieplok’s [22] spatial modeling of vibratory conveyors demonstrated that misalignment between the resultant excitation force vector and the machine’s center of mass causes deviations from ideal trough trajectories, providing theoretical insights into vibration complexity. Hrabovský et al. [23] empirically identified the highest effective vibration velocity in the vertical direction trough sensor measurements, offering critical guidance for sensor placement and data interpretation. Jing et al.’s [24] research directly addressed noise generation in combine harvester conveyor troughs, proposing damping optimization strategies that validated dynamic behavior modification as an effective solution pathway. Nevertheless, these studies predominantly focused on theoretical models or specific phenomena, failing to elucidate the intrinsic correlations and action mechanisms between structural parameters of the cantilevered conveyor trough and its holistic sway characteristics [25,26,27,28].

In structural optimization, multi-parameter collaborative design has emerged as a core methodology for complex engineering problems [29,30,31]. In agricultural machinery, Yu et al. [32] optimized cutting components of garlic harvesters, while Huang et al. [33] enhanced Boehmeria nivea harvester cutting–conveying mechanisms trough multi-factor regression models, with both demonstrating substantial performance gains. For structurally analogous components like crane telescopic booms [34,35,36] and excavator booms [37,38], researchers have successfully applied multi-body dynamics and reliability-based optimization to achieve weight reduction and dynamic stability improvements [39]. These methodologies find parallel applications in other sectors involving heavy machinery. Likewise, equipment such as high-capacity belt conveyors, bucket-wheel excavators, and scraper conveyors encounter comparable challenges of dynamic instability and structural vibration [40,41,42]. Therefore, the methodological advances made in these fields offer a valuable foundation for present research.

Despite this progress, critical gaps persist in optimizing the cantilevered conveyor trough of combine harvesters [43,44,45]. Existing research predominantly targets static strength, fatigue life, or noise control, such as Wei et al.’s [46] static force analysis of swing arms, while neglecting dynamics-focused optimization explicitly targeting sway suppression. Although multi-parameter optimization precedents exist for analogous components, the systematic application of statistical methods to identify and optimize key parameters of the cantilevered conveyor trough remains unexplored [47,48,49,50]. This methodological gap impedes precise quantification of each parameter’s contribution ratio to sway amplitude, thereby hindering targeted collaborative optimization [51,52,53].

To address these limitations, this study conducts a systematic investigation of vibration suppression in the cantilevered conveyor trough of rice combine harvesters, spanning theoretical modeling, parameter identification, and experimental validation. A dynamic model is established to dissect the physical origins of sway. Orthogonal experimental design is employed with initial angle, overall length, and cylinder pivot length as critical optimization parameters, which reduces experimental iterations while ensuring statistical rigor. Multi-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) quantifies each parameter’s contribution ratio to sway amplitude to identify dominant factors. Field validation tests verify the efficacy of the optimized parameter combination, providing theoretical foundations and engineering solutions for low-vibration design and multi-parameter collaborative optimization of cantilevered conveyor troughs in combine harvesters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Output Response Test of the Cantilevered Conveyor Trough

2.1.1. Experimental Device and Instruments

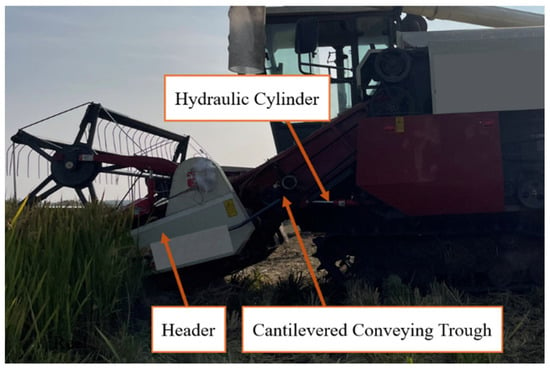

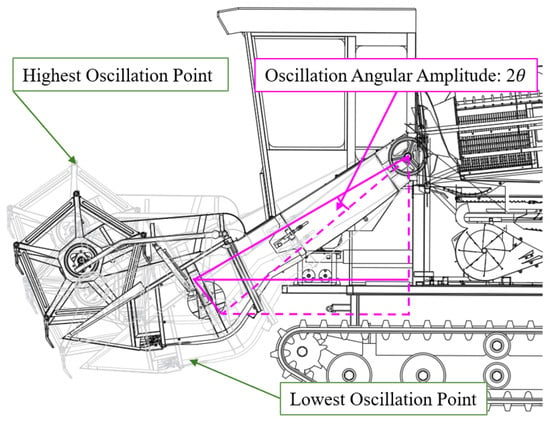

This study focuses on the cantilevered conveyor trough, a critical component of combine harvesters responsible for conveying rice stalks from the header to the threshing drum. Its structural assembly comprises the trough body, hydraulic cylinder support system, and chassis connection elements. Physical configuration is illustrated in Figure 1, while Figure 2 presents a mathematically simplified model derived from dynamic equations for analyzing the influence of parameters such as overall length and initial angle on sway behavior.

Figure 1.

Cantilevered conveyor trough entity.

Figure 2.

Mathematical simplified model of cantilevered conveyor trough.

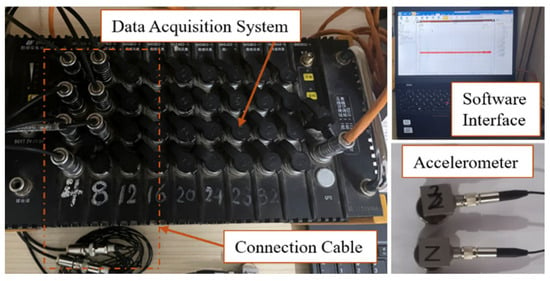

Vibration data acquisition employed a system developed by Donghua Testing Technology Co., Ltd. (Jingjiang, China), featuring a DH5902 dynamic signal analyzer, dedicated software, and triaxial accelerometers, as shown in Figure 3. The complete setup included one computer, one analyzer unit, and connecting cables. The analyzer supports 38 signal channels (36 vibration channels and 2 rotational speed channels) with IEPE input mode. A sample frequency of 1 kHz was configured to ensure comprehensive capture of high-frequency vibration data. Triaxial accelerometers (Model 1A312E) with a measurement range of 500 m/s2, resolution of 0.001 g, and sensitivity of 1 mV/m/s2 were utilized. Equipment parameter adjustments included channel configuration, filter settings, and sensitivity calibration.

Figure 3.

Dynamic signal acquisition analyzer.

2.1.2. Layout of Sensor Test Points

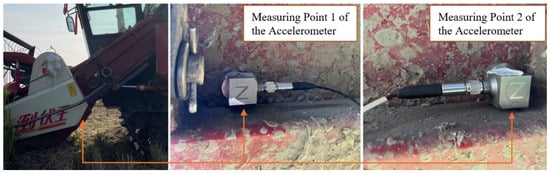

This experiment prioritized analyzing dynamic responses of the cantilevered conveyor trough under varying structural parameters. Field tests were conducted in agricultural fields of Dantu District, Zhenjiang City, Jiangsu Province. The combine harvester was operated at constant speed with full cutter bar width engagement. Two symmetric test points were positioned at the junction between the trough and chassis to minimize random errors, as this symmetric layout helps average out asymmetries in vibration transmission caused by uneven loads or structural tolerances, ensuring that the acquired acceleration signals accurately represent the overall sway characteristics of the cantilevered conveyor trough, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Verification test instrument layout.

2.2. Theoretical Foundation and Model Construction for Structural Optimization Theoretical Foundation and Model Construction for Structural Optimization

2.2.1. Theoretical Model Development

Dynamic analysis of Equation (1) reveals that the overall length and initial angle of the conveyor trough are pivotal factors inducing sway [54]. To reduce sway amplitude during operation and prevent crop blockage, structural redesign of the trough is essential. The initial angle directly governs the inclination angle at the junction between the trough and header, thereby influencing rice stalk conveyance efficiency. An excessively small initial angle increases blockage risk due to excessive junction inclination, while an overly large angle extends the trough length, compromising machine maneuverability. Consequently, theoretical modeling must optimize the overall length, cylinder pivot length, and structural inclination angle in accordance with the physical constraints of the header–conveyor interface.

where T is the total kinetic energy of the system, m is the conveyor chute mass, l is the overall length, and θ1 is the initial angle.

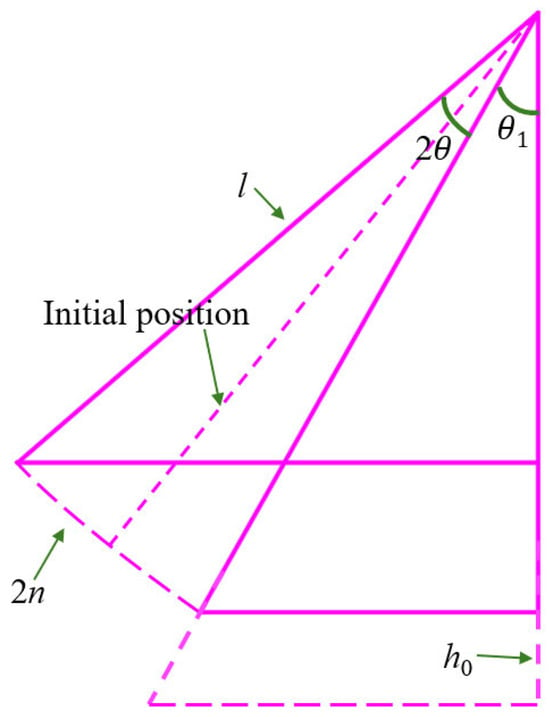

To address sway imbalance caused by length and initial angle variations, the parameter set for the simplified dynamics model of the header–conveyor system is completed as illustrated in Figure 5. This model assumes that during combine harvester operation, the header ground clearance (h0) is adjusted via hydraulic cylinders to achieve an initial angle (θ1). Under this configuration, the trough swing angle range is 2θ, with a corresponding arc length of 2n. This sway amplitude range serves as a constraint condition for post-optimization trough design.

Figure 5.

Simple model of cantilevered conveyor trough.

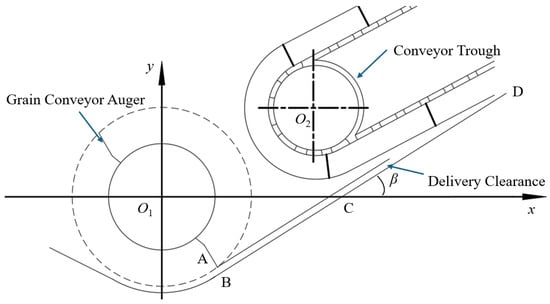

Ensuring seamless material transfer from header to trough requires optimizing the geometric relationship at their junction to minimize collisions between rice stalks and scraper plates. As shown in Figure 6, a parametric model aligns the grain auger base plate plane (BC) with the conveyor trough base plate (CD) on a common plane, guaranteeing continuous stalk transfer. In this model, Equation (2) for line BCD is defined as follows:

where β denotes the structural inclination angle between the trough base plate and the x-axis, and e represents the y-axis intercept.

Figure 6.

Relative position of the auger and the conveyor trough.

2.2.2. Limit Inclination Angle Calculation and Parameter Validation

Determining the optimal structural inclination angle requires satisfying distance constraints from the auger center (O1) and trough driven shaft center (O2) to line BCD. The geometric relationship is governed by Equation (3):

where O1 coordinates are (0, 0), O2 coordinates are (30, 20) (unit: mm), lAB is the minimum distance from auger paddle tip to base plate (20 mm), and lgx is the conveyance clearance (15 mm). Solving yields a practical β value of 41.67° and θ1 of 48.33°, in close agreement with the actual initial angle (46.40°) of the combine harvester. This configuration maintains adequate trough rotational speed for stalk conveyance and ensures smooth transition between header and trough, where e is −26.8, yielding Equation (4):

This line defines the limiting installation position for the trough base plate. To mitigate experimental variability, three initial angle levels (46.40°, 48.33°, 50°) are selected for multi-parameter optimization validation.

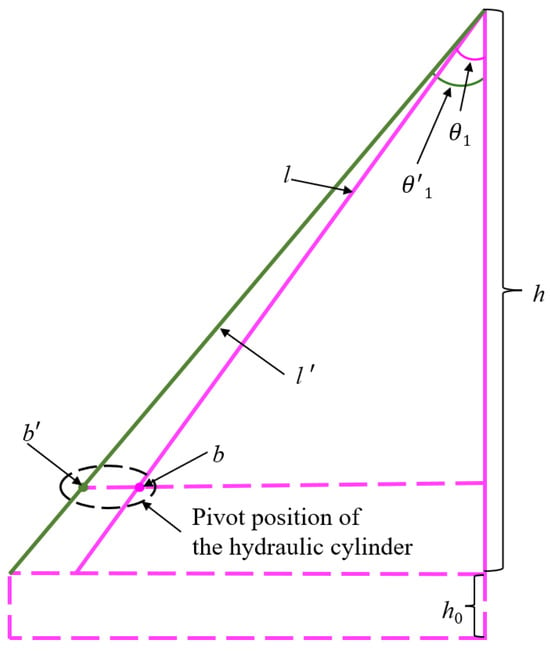

Fulfilling the smooth transition requirement further determines the overall length and cylinder pivot length. Optimized and pre-optimization models of the cantilevered conveyor trough are constructed as depicted in Figure 7. Applying a geometric constraint gives Equation (5):

where l′ is the optimized overall length, b is the cylinder pivot length, b′ is the optimized cylinder pivot length, and θ′ is the optimized initial angle. With h set to 1 m, the calculations yield l′ at 1.50 m and b′ at 1.04 m.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the cantilevered conveyor trough model before and after optimization.

2.3. Orthogonal Experimental Design and Multi-Factor ANOVA Methodology

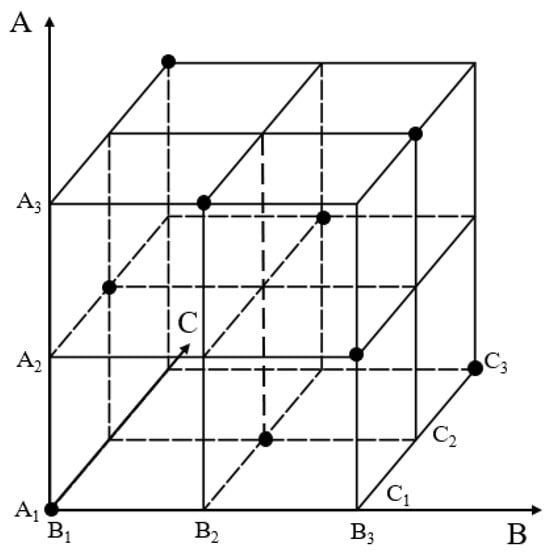

To systematically analyze the influence of cantilevered conveyor trough structural parameters on sway amplitude, this study employs a multi-factor experimental design. Based on preceding analysis, initial angle (Factor A), overall length (Factor B), and cylinder pivot length (Factor C) were identified as critical factors. Each factor was assigned three levels as shown in Table 1, balancing structural feasibility and experimental practicality: initial angle at 46.40°, 48.33°, and 50°; overall length at 1.45 m, 1.504 m, and 1.55 m; cylinder pivot length at 1.00 m, 1.04 m, and 1.10 m. This range encompasses operational parameter variations observed in field conditions.

Table 1.

Horizontal code of orthogonal experimental factors.

A full factorial design would require 27 combinations. To balance experimental efficiency with comprehensiveness, an orthogonal experimental design was adopted to reduce test iterations. This approach samples representative points across the parameter space design model in Figure 8, selecting nine critical experiments from the full set. This ensures uniform distribution of factor levels, enabling efficient evaluation of main effects and potential interactions, as shown in the experimental scheme in Table 2.

Figure 8.

Orthogonal experimental model.

Table 2.

Orthogonal experimental scheme.

Experimental data were obtained through numerical simulation. Each parameter combination was substituted into the cantilevered conveyor trough dynamic differential Equation (6), which was solved in MATLAB2022b to determine steady state swing angle variations. The sway amplitude at the trough end was calculated by multiplying the swing angle variation by the overall length. Given the overall length substantially exceeds swing angle variations, the amplitude was approximated as the sway amplitude at the trough end using the geometric relationship in Equation (7):

where S denotes sway amplitude (unit: m), θ represents swing angle variation (unit: rad), and l is the overall length (unit: m). Swing angle response curves were generated via simulation for each parameter combination, with sway amplitude results aggregated for subsequent analysis. To minimize random errors, each experiment was repeated three times, and the mean sway amplitude served as the final observed value. Data acquisition focused exclusively on displacement responses at the trough end, with high-frequency noise interference excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis implemented multi-factor ANOVA using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 software. Sway amplitude served as the dependent variable, with initial angle, overall length, and cylinder pivot length as fixed factors. A main effects model was configured to initially evaluate independent factor influences, excluding interaction terms. The significance threshold α was set at 0.05. Prior to analysis, homogeneity of variance was verified using Levene’s test to satisfy ANOVA assumptions. Duncan’s multiple range test compared subset differences across factor levels and validated orthogonality principles. Model goodness-of-fit was assessed via the adjusted coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.990), while residual analysis confirmed model reliability. This quantified each parameter’s contribution ratio to sway amplitude, providing statistical foundations for optimization design.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Multi-Factor ANOVA Results and Optimization Validation for the Cantilevered Conveyor Trough Structure

3.1.1. Influence Degree Analysis Under Multi-Parameter Combinations

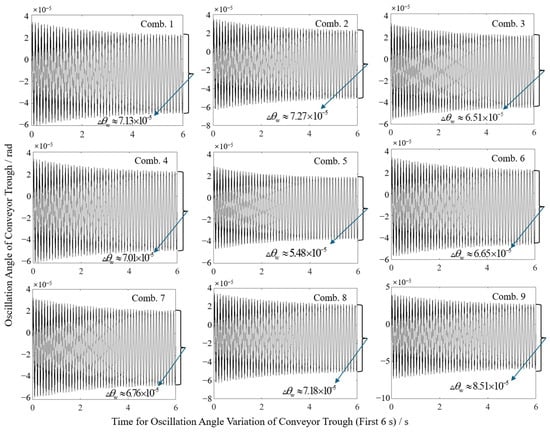

Orthogonal experimental results reveal the significant impacts of structural parameters on sway characteristics, as shown in Figure 9. Compiled swing angle variations and end sway amplitudes for all test groups are presented in Table 3. Simulation results demonstrate sway amplitudes ranging from 0.079 mm to 0.132 mm. The minimum amplitude occurred at combination A2B2C3 (initial angle 46.40°, overall length 1.45 m, cylinder pivot length 1.10 m), while the maximum occurred at A3B3C2 (initial angle 50°, overall length 1.55 m, cylinder pivot length 1.00 m). This disparity preliminarily confirms the critical role of parameter optimization in sway suppression.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of change in lower swing angle in different horizontal combinations.

Table 3.

Swing results of each combination under orthogonal experiments.

Parameter combinations and corresponding sway amplitudes were imported into SPSS. Between-subject factors are detailed in Table 4. For initial angle, each level comprises three cases, yielding a total of nine experiments. Identical case distributions were applied to overall length and cylinder pivot length, validating the orthogonality and comprehensiveness of the experimental design. Between-subject effect testing, as shown in Table 5, was used to evaluate whether mean values across subgroups exhibited statistically significant differences under varying control variable levels, with sway amplitude as the dependent variable.

Table 4.

Parameters of inter-subject factors.

Table 5.

Inter-subject effect test.

ANOVA-quantified factors influence magnitudes. Significance levels for initial angle, overall length, and cylinder pivot length were 0.032, 0.036, and 0.023 (all < 0.05), confirming statistically significant effects on sway amplitude. Comparing Type III sums of squares and F-values, cylinder pivot length exerted the strongest influence (F = 42.250), followed by initial angle (F = 30.484) and overall length (F = 27.062). This aligns with dynamic model predictions: hydraulic cylinder pivot position directly alters torque distribution, dominating sway behavior. To ensure smooth transition between trough and header and prevent rice stalk blockage, the initial angle was fixed at 48.33°.

3.1.2. Interaction Analysis Under Multi-Parameter Combinations

Duncan’s post hoc test results for the three factors are presented in Table 6. Each parameter level was assigned to distinct subsets with no overlap between subsets, confirming significant inter-level differences. Notably, an initial angle of 48.33° (sway amplitude 0.104 mm) satisfies smooth transition design requirements, minimizing blockage risk without substantially increasing sway amplitude and demonstrating multi-objective optimization feasibility.

Table 6.

Post-inspection of influencing factors.

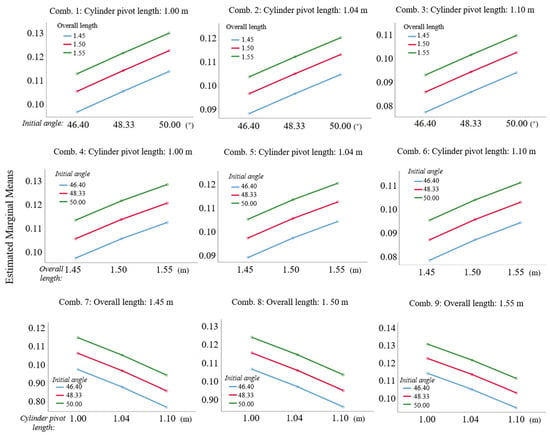

For interaction analysis, we employed estimated marginal means, as shown in Figure 10. Non-intersecting and non-converging lines for all factors indicate no significant interactions between initial angle, overall length, and cylinder pivot length. Sway amplitude trends remained consistent across overall length levels with negligible slope variations. This supports the main effects of model independence, enabling single-factor optimization and streamlining of parameter design.

Figure 10.

Relationship between different main factors and estimated marginal average.

3.1.3. Optimization Validation Under Fixed Initial Angle

Mean sway amplitudes were 0.096 mm, 0.105 mm, and 0.112 mm for overall length levels of 1.45 m, 1.50 m, and 1.55 m, respectively, preliminarily identifying 1.45 m as optimal. For cylinder pivot length levels of 1.00 m, 1.04 m, and 1.10 m, mean amplitudes were 0.114 mm, 0.105 mm, and 0.094 mm, preliminarily identifying 1.10 m as optimal. To verify robustness against transient motion effects, full factorial experiments were conducted with the initial angle fixed at 48.33°, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

A comprehensive experiment under an initial angle of 48.33°.

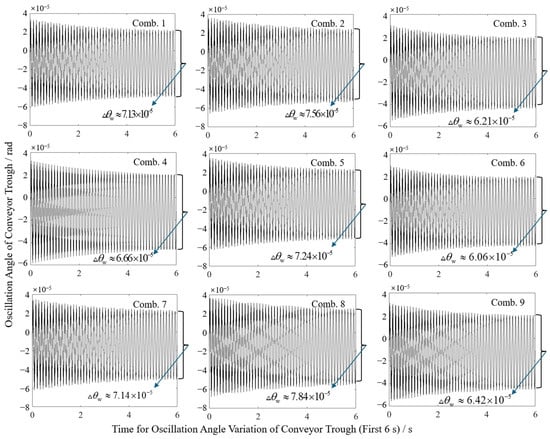

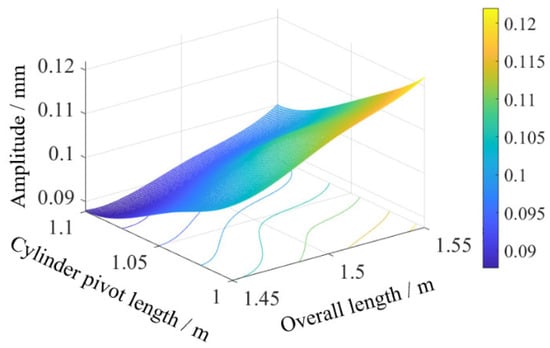

Swing angle results from Figure 11 and statistical summaries from Table 8 show that combination 6 (overall length 1.45 m, cylinder pivot length 1.10 m) achieved a minimum sway amplitude of 0.088 mm, while combination 8 (overall length 1.55 m, cylinder pivot length 1.00 m) yielded a maximum of 0.122 mm. Contour plot visualization in Figure 12 reveals sway amplitude gradients: amplitude decreases with reduced overall length or increased cylinder pivot length, with the latter exhibiting higher sensitivity. This higher sensitivity mechanically stems from the extended moment arm of the hydraulic force when the cylinder pivot length is increased, which optimizes torque distribution and damping in the dynamic system, as described in Equation (6). Compared to the theoretical sway amplitude of 0.0979 mm for the original configuration (initial angle 46.40°, overall length 1.45 m, cylinder pivot length 1.00 m), the optimized combination (initial angle 48.33°, overall length 1.45 m, cylinder pivot length 1.10 m) reduced the amplitude to 0.088 mm, representing a 10.11% decrease.

Figure 11.

Variation in swing angle in different horizontal combinations.

Table 8.

Swing results of each combination under full factorial experiments.

Figure 12.

Contour map of combined swing.

This validates optimization efficacy and underscores cylinder pivot length’s pivotal role in sway control. The reduction mechanism likely involves modified hydraulic cylinder force arm ratios that optimize torque equilibrium, thereby suppressing vibration amplitude. The initial angle of 48.33° achieves equilibrium between smooth material transition and sway control, exemplifying engineering compromise under multi-constraint optimization.

3.2. Field Validation and Dynamic Characteristic Analysis

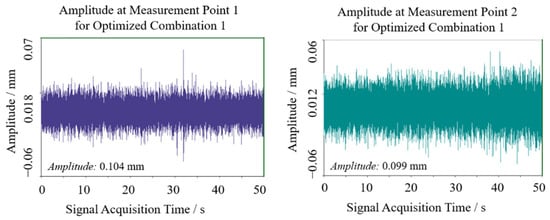

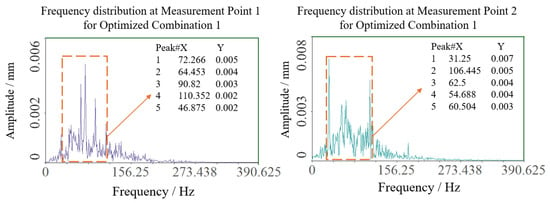

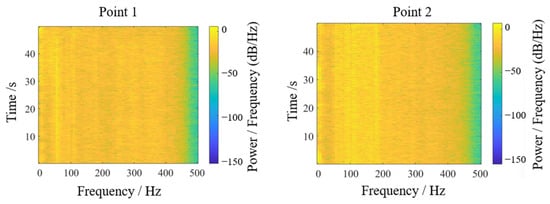

Field experiments were conducted to verify the practical efficacy of theoretically optimized parameters. The cantilevered conveyor trough initial angle was adjusted to 48.33° (optimization combination 1) while maintaining other parameters constant. Two symmetric sensor test points were positioned at the junction between trough and chassis to ensure data reliability. Signals were acquired during stable operational conditions, with transient segments at signal onset and termination excluded. Stable working interval data underwent double integration and FFT transformation to obtain sway amplitude and vibration frequency distribution, as shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14. Test point 1 exhibited an amplitude of approximately 0.104 mm, while test point 2 showed 0.099 mm, yielding a mean amplitude of 0.1015 mm. Vibration frequencies were concentrated in the 50–110 Hz range, falling within the low-frequency regime relative to the structural characteristics of harvesters, with dominant frequencies of 72.226 Hz at test point 1 and 31.25 Hz at test point 2. The differences in vibration spectra between the test points may be attributed to field test variability, such as asymmetric loading from uneven crop distribution, minor structural tolerances, or environmental factors like ground irregularities. However, consistency in mean amplitude values across points supports the robustness of the optimization outcomes, as the low-frequency sway characteristics remain dominant and aligned with the theoretical model.

Figure 13.

Swing results of optimization 1 test point.

Figure 14.

Spectrum results of optimization 1 test point.

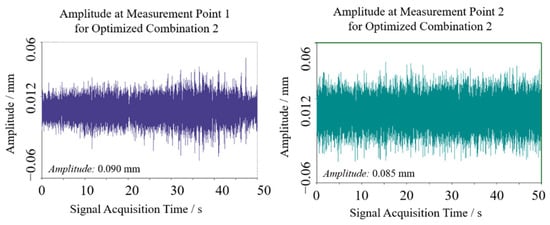

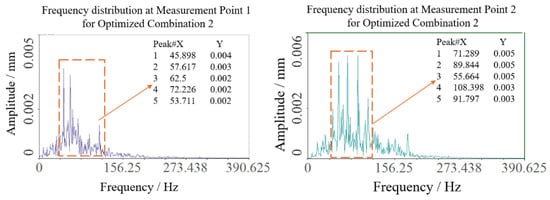

Similarly, optimization combination 2 yielded sway amplitudes of 0.090 mm and 0.085 mm at the two test points, with a mean of 0.0875 mm, as shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16. Vibration frequencies remained predominantly low-frequency, ranging from 50 to 110 Hz, with dominant frequencies of 45.898 Hz at test point 1 and 71.289 Hz at test point 2.

Figure 15.

Swing results of optimization 2 test point.

Figure 16.

Spectrum results of optimization 2 test point.

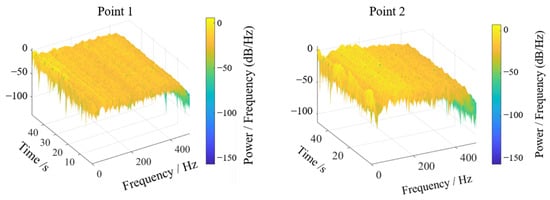

Energy-based vibration analysis was performed via Fourier transformation of acceleration signals, generating an energy response spectrum in the sway direction, as shown in Figure 17 and Figure 18. For test point 1, displacement signal energy concentrated at low frequencies near 50 Hz perpendicular to the trough sway direction. The three-dimensional spectrogram provided intuitive energy distribution visualization: despite minor environmental and experimental interference, persistent dominant frequency peaks were evident over time. Test point 2 similarly showed concentrated low-frequency energy near 70–100 Hz, consistent with prior analysis.

Figure 17.

Displacement signal energy diagram.

Figure 18.

Three-dimensional waterfall diagram of displacement signal energy.

To evaluate the accuracy and error between the original sway amplitude of 0.099 mm, the theoretical design amplitude, and the optimized design amplitude, and to assess the validity of theoretical optimization and the reliability of experiments, the parameter combinations and sway amplitudes under all three conditions were statistically compared using data from Table 9. Under the dual optimization objectives of seamless material conveyance and sway reduction, optimization combination 2 achieved a theoretical sway amplitude of 0.088 mm and an actual amplitude of 0.0875 mm, yielding a 0.57% error. This represents an 11.62% reduction compared to the original parameter combination, which had an amplitude of 0.099 mm. These results validate the effectiveness of multi-parameter collaborative optimization, demonstrating that the strategic configuration of cylinder pivot length and overall length significantly enhances the dynamic performance of the conveyor trough. Minor errors may stem from factors such as sensor measurement noise, slight environmental variations during field tests, or simplifications in the dynamic model; however, the low error rates consistently support the robustness of the approach.

Table 9.

Validation test optimization parameter results.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the influence of structural parameters on the sway characteristics of the cantilevered conveyor trough through integrated theoretical modeling, orthogonal experimental design, multi-factor ANOVA, and field validation. The following conclusions were drawn:

- Cylinder pivot length exerted the most significant influence on sway amplitude (F = 42.250, p = 0.023), surpassing the contributions of initial angle (F = 30.484) and overall length (F = 27.062). This confirms that repositioning the hydraulic cylinder pivot directly optimizes torque distribution, effectively suppressing vibration. Duncan’s post hoc test further validated statistically significant differences between factor levels, providing robust statistical foundations for engineering optimization.

- The optimal parameter combination identified via orthogonal design (initial angle 48.33°, overall length 1.45 m, cylinder pivot length 1.10 m) reduced the theoretical sway amplitude to 0.088 mm, representing a significant 11.62% decrease compared to the original configuration, which had an amplitude of 0.099 mm. Field validation confirmed an actual sway amplitude of 0.0875 mm under this combination, yielding a negligible 0.57% deviation from theoretical predictions. This demonstrates the exceptional robustness and reliability of the optimization framework.

- Setting the initial angle to 48.33° achieved dual objectives: sway amplitude reduction and seamless geometric transition between header and trough. This configuration minimized rice stalk blockage risks by ensuring continuous alignment between the grain auger base plate and cantilevered conveyor trough base plate. The optimized design exemplifies feasible engineering trade-offs under multi-constraint conditions, validating the practicality of integrated structural optimization for agricultural machinery.

- The study emphasizes the application of sensor data for structural optimization. The dynamic model incorporated simplifications under ideal assumptions, such as neglecting elastic deformation and nonlinear effects; however, the conclusions verify its effectiveness within the engineering scope. The applicable parameter ranges are initial angle 46.4–50°, overall length 1.45–1.55 m, and cylinder pivot length 1.00–1.10 m, which are suitable for combine harvesters operating at constant speed on relatively flat terrain. Deviations beyond these ranges may require revalidation. Future work will address actual device characteristics and complex field conditions to enhance model generality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization Z.T., Q.H. and Z.S.; methodology, Z.T., Z.Z. and Q.H.; validation, T.L., J.S. and Z.S.; formal analysis, Q.H., Z.Z. and T.L.; data curation, Q.H., J.S. and T.L.; investigation, T.L., Z.S. and P.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.H. and T.L.; writing—review and editing, P.Q. and Z.S.; supervision, P.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was supported by the Jinhua science and technology research project (Grant No. 2023-2-024), the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Plan Project (2025YFDZ0033), the Nantong Social Livelihood Science and Technology Project (MS2023016), the Innovation and Practice Fund Project of the School of Artificial Intelligence and Intelligent Manufacturing of Jiangsu University (RZCX2024053), and the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX25_2455).

Data Availability Statement

The data in this article can be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, T.; Xu, L.; Ahn, H.S.; Lu, E.; Liu, Y.; Xu, R. Evaluation of headland turning types of adjacent parallel paths for combine harvesters. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 233, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ji, J.; Ji, K.; Chen, Y. Deep learning-driven predictive control method for optimizing combine harvester operation speed. Eng. Agrícola 2025, 45, e20240150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Z. Sensor for monitoring rice grain sieve losses in combine harvesters. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 147, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yu, Y.; Ma, T.; Liu, P.; Xu, L. Design of attitude-adjustable chassis and dynamic stress analysis of key components for crawler combine harvester. J. Agric. Eng. 2024, 56, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fan, S.; Zhang, B.; Wang, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Q. Research Status and Development Trends of Deep Reinforcement Learning in the Intelligent Transformation of Agricultural Machinery. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.; Yang, W.; Hu, X.; Cai, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, X. Multi-Source Feature Fusion Network for LAI Estimation from UAV Multispectral Imagery. Agronomy 2025, 15, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Liu, J.; Jin, Y.; Yang, K.; Zhao, S.; Peng, Y. Vibration–Collision Coupling Modeling in Grape Clusters for Non-Damage Harvesting Operations. Agriculture 2025, 15, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.; Ouyang, K. Modeling and Simulation of Reel Motion in a Foxtail Millet Combine Harvester. Agriculture 2025, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Jianjun, H.; Yong, C.; Ali, A.; Song, H.; Zheng, D.; Farid, M.U.; Ghafoor, A.; Ahmed, M. CFD study of self-cleaning system of multi-stage tangential roller threshing unit for precise buckwheat breeding. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Zhang, B.; Ji, A.; Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Shen, C. Design and experiment of the bionic disc cutter for kenaf harvesters. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2023, 16, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Du, X.; Liu, Y. Threshing cylinder unbalance detection using a signal extraction method based on parameter-adaptive variational mode decomposition. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 244, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Quan, L. Cooperative Control Strategy of Multi-Component Speed of Distributed Electric Drive Combine Harvester. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2025, 41, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ji, K.; Yu, Z.; Ma, Z.; Xu, L.; Niu, C. Development of a hydraulic variable-diameter threshing drum control system for combine harvester part II: Controller design and field performance. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 254, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, K.; Zhu, R. A Fault Diagnosis Method for a Differential Inverse Gearbox of a Crawler Combine Harvester Based on Order Analysis. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Min, H.; Yaoming, L.; Shuncheng, Y.; Farman Ali, C. Comparing kernel damage of different threshing components using high-speed cameras. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunegatto, E.H.T.; Zinani, F.S.F.; Rigo, S.J. Multi-objective optimisation of micromixer design using genetic algorithms and multi-criteria decision-making algorithms. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2024, 7, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xiao, H.; Dai, Z.; Wang, C.; Sun, C.; Watson, N.; Povey, M.; Zou, X. Identification of apple variety using machine vision and deep learning with multi-head attention mechanism and GLCM. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025, 19, 6540–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, P. Vibration measure and analysis of crawler-type rice and wheat combine harvester in field harvesting condition. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. (Trans. CSAE) 2017, 33, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, F.; Radu, S.; Kotwica, K.; Andras, A.; Brînaș, I.; Dinescu, S. Vibration analysis of a bucket wheel excavator boom using rayleigh’s damping model. New Trends Prod. Eng. 2019, 2, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Qian, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Páez, L.M.R.; Qian, P. Intelligent selection of parameters for air-floating piston based on improved multi-objective grey wolf optimisation algorithm. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2025, 8, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nariman, N.A. Crack propagation control for a pre-stressed concrete beam utilising coupled sensitivity indices-Pareto optimisation method. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2024, 7, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieplok, G. Influence of vibratory conveyor design parameters on the trough motion and the self-synchronization of inertial vibrators. OPEN Eng. 2024, 14, 20220434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabovský, L.; Pravda, Š.; Fries, M. Sensor Monitoring of Conveyor Working Operation with Oscillating Trough Movement. Sensors 2025, 25, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Sun, H.; Liang, R.; Chen, S.; Tang, Z.; He, X.; Chen, Y. Noise Testing of the Conveyor Trough Sprocket and Surface Noise Reduction Performance Evaluation of the Cavity Structure in a Combine Harvester. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Gao, Z.; Lu, E.; Li, Y. Effect of Vibration on Rapeseed Header Loss and Optimization of Header Frame. Trans. ASABE 2021, 64, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, C.; Cao, G.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J. Dynamic monitoring of harvester working progress based on traveling trajectory and header status. Eng. Agrícola 2023, 43, e20220196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Du, X.; Ji, K. Unbalanced variation after assembly and double-speed influence coefficient method in the threshing drum. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2023, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyanthi, S.; Venkatakrishnaiah, R.; Raju, K.V.B. Multilayer geocell-reinforced soils using mayfly optimisation predicts circular foundation load settlement. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2024, 7, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, H.; Ren, M.; Wang, J.; Qian, P. Intelligent optimization of air-floating piston core parameters for homemade frictionless pneumatic actuators based on a new multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm with Gaussian mutation and fuzzy logic. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 154, 111053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qi, J.; Gao, J.; Chen, W.; Fei, J.; Meng, H.; Ma, Z. Research on the Control System for the Conveying and Separation Experimental Platform of Tiger Nut Harvester Based on Sensing Technology and Control Algorithms. Agriculture 2025, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Du, C.; Chen, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X. Development and test of a spring-finger roller-type hot pepper picking header. J. Agric. Eng. 2024, 55, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yang, K.; Hu, Z.; Peng, B.; Gu, F.; Yang, L.; Yang, M. Parameter optimization and simulation analysis of floating root cutting mechanism for garlic harvester. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tian, K.; Shen, C.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Ji, A. Design and parameters optimization for cutting-conveying mechanism of ramie combine harvester. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glad Stephen, J.D.; Banerjee, A.; Lahiri, A.; Mehta, I. Optimization of cross section of mobile crane boom using lagrange multiplier’s method. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 402, 012134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Meng, L. The dynamic stability analysis of telescopic booms of the crane based on the energy method. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 399, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramani, M.A.; Venkatakrishnaiah, R.; Raju, K.V.B. A mayfly optimisation method to predict load settlement of reinforced railway tracks on soft subgrade with multi-layer geogrid. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2023, 6, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Bao, Y.; Li, Q. Finite element analysis of excavator mechanical behavior and boom structure optimization. Measurement 2021, 173, 108637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, L.; Gao, W.; Shi, N.; Wang, N.; Ye, M.; Gu, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, J. Reliability-based design optimization for the lattice boom of crawler crane. Structures 2021, 29, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andryukhov, N.M.; Pavlov, S.A.; Mikhailov, K.D. Changing the spatial structure of the rocker arm of the tipping mechanism in a garbage truck. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1159, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnowski, P.; Król, R.; Ozdoba, M. Modelling of transverse vibration of conveyor belt in aspect of the trough angle. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, F.D.; Radu, S.M.; Kotwica, K.; Andraș, A.; Kertesz, I. Simulation of the Time Response of the ERc 1400-30/7 Bucket Wheel Excavator’s Boom during the Excavation Process. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Liu, Z.; Bi, W.; Wei, X. Study on the mechanical effect and wear behaviour of middle trough of a scraper conveyor based on DEM–MBD. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2021, 236, 135065012110592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Lv, L.; Shi, Y.; Yu, X. Study on Modeling Method of a Multi-Parameter Control System for Threshing and Cleaning Devices in the Grain Combine Harvester. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, E.; Mao, H.; Zuo, Z.; Peng, H.; Zhao, M.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z. Design and Testing of an Electric Side-Mounted Cabbage Harvester. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Hu, J.; Liu, W.; Shi, J.; Jin, Y.; Lv, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, C. Precise Servo-Control System of a Dual-Axis Positioning Tray Conveying Device for Automatic Transplanting Machine. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Jin, P. Finite element analysis of the vertical roller mill based on ANSYS Workbench. Int. J. Eng. Syst. Model. Simul. 2019, 11, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liang, C.; Mu, X.; Huang, L. Multi-objective optimization design of rocker arm on crown-mounted compensator. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 64, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, P.; Luo, H.; Liu, L.; Lv, P.; Pu, C.; Meng, D.; Páez, L.M.R. A hybrid Gaussian mutation PSO with search space reduction and its application to intelligent selection of piston seal grooves for homemade pneumatic cylinders. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Gu, X.; Zhang, B. Understanding the Lubrication and Wear Behavior of Agricultural Components Under Rice Interaction: A Multi-Scale Modeling Study. Lubricants 2025, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Gao, J.; Jin, Z. Research on Acoustic Signal Identification Mechanism and Denoising Methods of Combine Harvesting Loss. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuping, Z.; Zengjie, Y.; Lei, X. Research on the Topology Optimization of the rocker arm of compression garbage truck based on Rigid-Flexible coupling. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 423, 012107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Liu, L.; Qian, P.; Iqbal, N.; Emzir, M.F. A fuzzy adaptive particle swarm optimization algorithm with Gaussian mutation for constrained engineering problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 185, 113908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, P.; Pu, C.; Liu, L.; Luo, H.; Wu, J.; Jia, Y.; Liu, B.; Ruiz Páez, L.M. Ultra-high-precision pneumatic force servo system based on a novel improved particle swarm optimization algorithm integrating Gaussian mutation and fuzzy theory. ISA Trans. 2024, 152, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Tian, L.; Qian, P.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, T. Vibration Characteristics Analysis of the Header Assembly of Combine Harvester Under Multi-Source Coupled Excitation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).