Abstract

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease that leads to motor, cognitive, and sensory impairments, significantly affecting walking and quality of life. This study aimed to analyze the relationship between quality of life and kinematic walking parameters in individuals with multiple sclerosis, as well as to evaluate the influence of fatigue, balance, and cognitive performance on different aspects of quality of life. A cross-sectional observational study was conducted with 32 patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis with Expanded Disability Status Scale scores of ≤5.5. Quality of life was assessed using the MusiQoL questionnaire, and clinical variables included fatigue (Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions, Borg scale), balance (Berg Balance Scale), and cognitive performance (Trail Making Test). Walking kinematics were analyzed using the Vicon motion capture system to obtain walking speed, step frequency, and joint asymmetry indices. Spearman correlations and linear regression models were applied. Results showed significant correlations between quality of life and walking speed (rho = 0.506), step frequency (rho = 0.508), and knee asymmetry (rho = −0.525), as well as strong associations with cognitive fatigue (rho = −0.796) and balance (rho = 0.635). Regression models explained up to 58.4% of the variance in the Activities of Daily Living dimension. These findings indicate that quality of life in multiple sclerosis is influenced by both clinical and biomechanical factors, highlighting the importance of comprehensive assessments to guide physiotherapeutic interventions.

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory, and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by demyelination and axonal injury mediated by abnormal immune activation of T and B lymphocytes across a disrupted blood–brain barrier [1,2,3,4,5,6]. This condition primarily affects young adults between 20 and 40 years of age, with a higher incidence in women (approximately 3:1), and a rising global prevalence currently exceeding 2.5 million individuals [1,2,3,6,7,8,9]. Its etiology is multifactorial, involving genetic factors such as the HLADRB1*15:01 allele [10] and environmental contributors, including vitamin D deficiency, obesity, smoking, and Epstein–Barr virus infection [11,12,13,14]. This growing prevalence highlights the importance of developing objective and integrative assessment tools capable of linking neurological impairment with functional outcomes such as gait performance and quality of life.

The clinical presentation of MS is heterogeneous and is mainly classified into four phenotypes: relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS), primary progressive MS (PPMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), and progressive–relapsing MS (PRMS) [6,7,8]. RRMS accounts for more than 80% of initial cases and is characterized by reversible neurological relapses that progressively leave permanent sequelae. Approximately 50% of patients with RRMS convert to SPMS after 10–15 years [15]. Clinical manifestations include motor weakness, sensory disturbances, visual impairment, coordination deficits, fatigue, and cognitive dysfunction [16,17]. Progressive disability is commonly assessed using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [18,19].

One of the most critical aspects for functional independence is gait, a complex motor process requiring the coordinated integration of pyramidal, extrapyramidal, cerebellar, and vestibular systems along with proprioceptive inputs [20]. In individuals with MS, gait is impaired by muscle weakness, spasticity, cerebellar dysfunction, and sensory loss, resulting in asymmetrical patterns, reduced speed, and increased irregular cadence [20,21,22]. Previous studies indicate that up to 50% of patients experience walking difficulties in early stages [23], and nearly 50% require assistance for ambulation within the first 15 years [24]. Moreover, instability and balance disturbances contribute to an increased risk of falls, negatively impacting quality of life (QoL) [24,25,26,27].

Multiple investigations have demonstrated that factors such as fatigue—present in 75–95% of patients [28]—and reduced processing speed and executive function [29] directly affect functional independence, motor performance, and social participation. These factors compromise not only gait but also the subjective perception of physical, psychological, and social well-being, as reflected in questionnaires such as the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL31) [30,31]. In addition, biomechanical alterations in gait can be objectively quantified using three-dimensional motion capture systems such as Vicon®, which allow the measurement of kinematic parameters (e.g., speed, cadence, asymmetry indices) [32], and their correlation with clinical variables to identify functional predictors and guide physiotherapeutic interventions [33,34,35,36]. In this context, Tsiakiri et al. [37] emphasize the integration of advanced technological approaches to optimize personalized rehabilitation strategies, enhance early diagnostic accuracy, and enable continuous long-term monitoring of disease progression in clinical practice.

Previous studies have reported that reduced gait velocity and cadence are associated with greater functional limitation and poorer QoL in individuals with MS [38]. These findings suggest that gait performance is a relevant indicator of daily functioning and well-being. However, most research has analyzed these parameters in isolation, without integrating three-dimensional kinematic variables with multidimensional measures of QoL and related clinical factors such as fatigue, balance, or cognition [39].

Based on this evidence, the present study aimed to analyze the relationship between QoL and kinematic gait parameters in individuals with MS, and to explore the influence of fatigue, balance, and cognitive performance on different dimensions of QoL, in order to identify clinically and biomechanically relevant predictors for physiotherapy practice.

2. Materials and Methods

An observational cross-sectional study involving patients diagnosed with MS was performed in the Human Performance Research Laboratory of Universidad Europea de Madrid (Villaviciosa de Odón, Madrid, Spain). The study protocol (ECL.24/753-E_Tesis) was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [40], and Spanish legislation regarding personal data protection and guarantee of digital rights [41]. All participants received written and verbal information about the study and provided informed consent prior to participation. Participants who requested it received an individual gait report; overall study results will be shared after publication.

An a priori power estimation for the main correlation analyses (two-tailed, Fisher’s z approximation; equivalent to G*Power’s (version 3.1.9.2) Correlation: Bivariate normal model) assuming an anticipated effect size of ρ = 0.50, α = 0.05, and 1–β = 0.80 indicated a minimum of 30 participants. The final sample (n = 32), therefore, provided adequate power (achieved power ≈ 0.84 for ρ = 0.50).

Recruitment was conducted via social media advertisements and by distributing study information to MS associations and foundations in the Autonomous Community of Madrid. All participants had a confirmed diagnosis of MS according to the revised McDonald criteria [42,43,44], were between 18 and 65 years of age, and had an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of ≤5.5, which ensured functional ambulation, with or without the use of assistive devices, and without the need for rest over approximately 100 m [45]. Additional inclusion criteria included the ability to comprehend and follow study instructions and to provide written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included the inability to access the research center, a relapse of MS within the month prior to enrollment, and a history of previous trauma, disorders, or comorbidities that could affect movement, gait, or balance. Patients with severe or unstable pulmonary or cardiac disease, conditions inherently associated with fatigue such as hypothyroidism, severe depression, or cardiorespiratory disorders, or severe visual impairment were also excluded [46,47].

2.1. Study Variables

For the analysis, the MusiQoL-31 questionnaire was considered overall (all 31 items) and subdivided into its nine distinct dimensions [30]: Activities of daily living (ADL; items 1 to 8), Psychological well-being (PWP; items 9 to 12), Symptoms (SPT; items 13 to 16), Relationships with friends (RFr; items 17 to 19), Relationships with family (RFa; items 20 to 22), Sentimental and sexual life (SSL; items 23 and 24), Coping (COP; items 25 and 26), Rejection (REJ; items 27 and 28), and Relationship with the healthcare system (RHCS; items 29 to 31).

Gait analysis was performed using a Vicon® Motion Capture System (Vicon Motion Systems Ltd., Oxford, UK), one of the most widely validated technologies for three-dimensional biomechanical assessment. The system consisted of eight infrared Vantage V5 cameras arranged peripherally around the laboratory to ensure complete visibility of the capture volume. Each camera emits and detects infrared light reflected by passive spherical markers (14 mm diameter) attached to anatomical landmarks according to the Plug-in Gait lower body model (Helen Hayes protocol). The cameras recorded at 120 Hz, synchronously capturing the three-dimensional trajectories of each marker with sub-millimetric precision (<1 mm error). Trajectories were reconstructed using Vicon Nexus software (version 2.16), which applies triangulation algorithms to compute spatial coordinates from multiple camera perspectives. Before each session, static and dynamic calibrations were performed using a reference wand and frame to align the camera coordinate system. During gait trials, participants walked inside the calibrated capture volume while the system automatically tracked the motion of each marker. Trajectories with data gaps shorter than 40 frames were interpolated using pattern or spline algorithms following the recommendations of Davis et al. [35]. The following parameters were extracted: gait velocity (m/s), cadence (steps/min), and range-of-motion (ROM) asymmetry indices for pelvis, hip, knee, and ankle joints.

The asymmetry index (AI) between the right and left limbs was calculated according to Robinson et al. [48], using the following expression:

where L represents the range of motion (ROM) of the left limb and R that of the right limb, and a value of 0% indicates perfect symmetry between both sides. The Vicon® Motion Capture System has been validated as a reliable and accurate tool for three-dimensional gait analysis in both healthy individuals and patients with neurological disorders, including MS [49]. Its high spatial and angular resolution supports the precision of the kinematic measurements obtained in the present study.

AI (%) = (|L − R|/(0.5 × (L + R))) × 100

The following biomechanical variables were then considered: Gait velocity (in meters per second), Cadence (steps per minute), Asymmetry index of single-leg support (%SI), Asymmetry index of total ROM (IART) for all joints (pelvis, hip, knee, and ankle), Asymmetry index of ROM during the stance phase (IARA) for all joints (pelvis, hip, knee, and ankle), and Asymmetry index of ROM during the swing phase (IARO) for all joints (pelvis, hip, knee, and ankle).

2.2. Study Procedures

The assessment sessions were held individually and lasted approximately 30 min. At the beginning of the sessions, the following data were collected: gender, age, type of MS, time of diagnosis, EDSS score (established by the evaluator based on previously described criteria [18], and pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. Then, the following clinical variables were assessed: MusiQoL [30,31], Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FMSC) [50], Trail Making Test (TMT) A and B [51], and the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) [52]. Afterwards, reflective markers were placed on anatomical landmarks according to the Vicon® Clinical Model (VCM) protocol [35,36], as shown in Figure 1, and the cameras were calibrated. Before starting the recording, perceived fatigue was monitored using the modified Borg Scale [53]. During data acquisition, each participant walked back and forth along a 10-m walkway within the calibrated capture volume of the Vicon® system at a self-selected fast pace. Several consecutive strides were recorded during this continuous trial, and three complete gait cycles per limb were selected from the central portion of the recording, once a steady walking pattern had been reached, to minimize acceleration and deceleration effects. This approach follows previous methodological recommendations for marker-based gait analysis in people with MS [28,34]. These cycles were used to compute the mean kinematic parameters for subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

Marker placement according to the modified Plug-in Gait lower body model (Vicon®, Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK) [35]. The figure shows anterior, posterior, and lateral views with pelvic and lower limb markers (LASI, RASI, LPSI, RPSI, LTHI, RTHI, LTIB, RTIB, LHEE, RHEE, LTOE, RTOE).

Assessments were performed by three physiotherapists specialized in neurorehabilitation and gait analysis. Data processing was conducted by an engineer experienced with the Vicon® system, and data analysis by another physiotherapist. Although no formal blinding was applicable, the assessors were unaware of participants’ clinical and questionnaire results during testing, thereby minimizing potential measurement bias.

Each participant attended a single 30-min session, including informed consent, clinical assessment, reflective marker placement, gait recording, and data processing, following the sequence previously described.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis was performed by determining the mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the normality of quantitative variables. Due to the non-normal nature of the data, correlations were performed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Following the criterion of Hopkins et al. [54], correlation coefficients were classified as negligible (ρ < 0.1), small (ρ ≥ 0.1 and <0.3), moderate (ρ ≥ 0.3 and <0.5), high (ρ ≥ 0.5 and <0.7), very high (ρ ≥ 0.7 and <0.9) and almost perfect (ρ ≥ 0.9).

No correction for multiple comparisons was applied due to the exploratory nature of the study and the small sample size; p-values should therefore be interpreted as indicative. The analysis was designed to explore potential associations within the total sample rather than to perform subgroup comparisons by MS subtype, given that the study was powered based on the overall cohort.

Different linear regression models were applied based on a combined statistical analysis strategy, considering variables that demonstrated a high level of correlation and clinical relevance, with the aim of including the most relevant factors for QoL in patients with MS. The stepwise regression method [55] was used with entry (p ≤ 0.05) and removal (p ≥ 0.10) criteria, allowing the exclusion of variables that did not contribute significantly to the model or introduced statistical redundancy (assessed via tolerance and variance inflation factor, VIF). Additionally, the coefficient of determination (R2) was used to evaluate the explanatory power of the model, and the Durbin-Watson statistic was applied to ensure that model assumptions were met.

Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 32 patients were included in the study, of whom 22 (68.75%) were women. The RRMS was the most prevalent type of MS, representing 78.1% of cases (n = 25), followed by the PPMS form (18.8%; n = 6), and the SPMS (3.1%; n = 1). The mean age of participants was 45 ± 10.14 years, and the mean EDSS score was 3.81 ± 1.56 points. Table 1 shows the descriptive analysis of study variables. The mean MusiQoL-31 score was 65.68 ± 15.20 points.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables (Mean ± SD) (minimum, maximum).

Correlations among variables

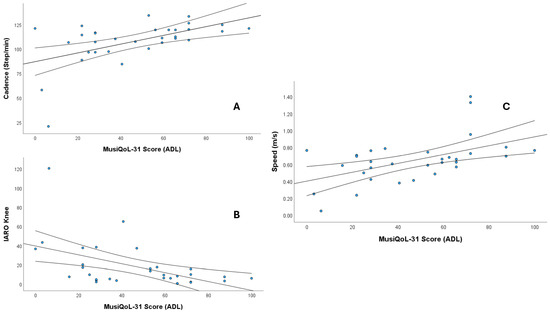

The ADL dimension showed strong correlations with cadence (ρ = 0.508), speed (ρ = 0.506), and knee IARO (ρ = −0.525) (p < 0.01). Additional significant moderate correlations were observed between cadence and REJ (ρ = 0.422) and the global score (ρ = 0.383); and RHCS (ρ = 0.453); hip IART with REJ (ρ = −0.411); knee IART with RFa (ρ = 0.411); hip IARA with REJ (ρ = −0.362); knee IARA with PWB (ρ = −0.397); and knee IARO with RFr (ρ = 0.411) and RHCS (ρ = 0.458) (all p < 0.05). Figure 2 shows scatter plots showing the significant correlations (ρ > 0.5).

Figure 2.

Scatter plots showing the significant correlations (Spearman’s ρ > 0.5) between MusiQoL-31 Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scores and gait parameters. (A) Cadence (steps/min), (B) IARO knee, and (C) Speed (m/s). The central line represents the regression line, and the outer lines represent the confidence intervals.

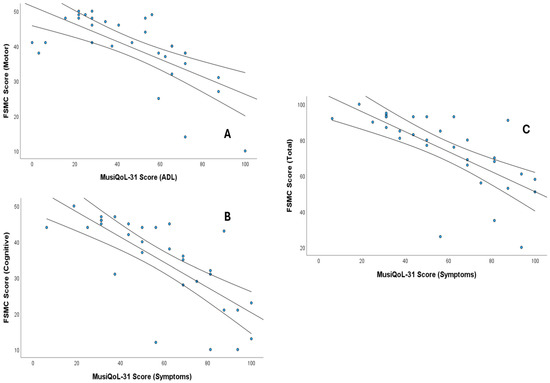

Fatigue was strongly associated with quality of life: very high correlations were found between SPT and cognitive FSMC (ρ = −0.796) and total FSMC (ρ = −0.775), as well as between ADL and motor FSMC (ρ = −0.708) (p < 0.05). High correlations (p < 0.01) were also observed between cognitive FSMC and the global score (ρ = −0.628); motor FSMC and SPT (ρ = −0.656); total FSMC with ADL (ρ = −0.550) and the global score (ρ = −0.551); and the Borg scale with ADL (ρ = −0.547).

Regarding clinical variables related to attention and executive functions, a high-intensity correlation (p < 0.01) was observed between TMT-B and ADL (ρ = −0.517). Additionally, TMT-A showed moderate-intensity correlations with ADL (ρ = −0.448) and SPT (ρ = −0.421) dimensions, as well as with the global score (ρ = −0.359); these correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Finally, balance (BBS) and EDSS correlated at a high-intensity level with ADL (ρ = 0.635 and ρ = −0.628, respectively) (p < 0.01). Likewise, ADL showed a moderate correlation with age (ρ = −0.365) (p < 0.05). Figure 3 shows scatter plots showing the significant correlations (ρ > 0.7). In the Supplemental Material, Tables S1 and S2 show the values and significance of all correlations performed.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots showing the significant correlations (Spearman’s ρ > 0.7) between MusiQoL-31 scores and fatigue measures (FSMC). (A) Correlation between MusiQoL-31 Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and FSMC Motor Score, (B) Correlation between MusiQoL-31 Symptoms and FSMC Cognitive Score, and (C) Correlation between MusiQoL-31 Symptoms and FSMC Total Score. The central line represents the regression line, and the outer lines represent the confidence intervals.

Linear Regression models

The regression analysis indicated that the combination of TMT-A (β = −0.398, 95% CI −0.746, −0.051) and cognitive FSMC (β = −0.456, 95% CI −0.869, −0.042) significantly predicted the global score of the MusiQoL-31 questionnaire, explaining 35% of the total variance (R2 = 0.392, adjusted R2 = 0.350, F(2,29) = 9.357, p < 0.001). Higher TMT-A times (slower processing and attention) and greater cognitive fatigue were associated with lower overall quality-of-life scores.

The model developed for the ADL dimension, which included motor FSMC (β = −1.488, 95% CI −2.167, −0.810) and BBS (β = 1.201, 95% CI 0.404, 1.998), explained 55.5% of the variance (R2 = 0.584; adjusted R2 = 0.555; F(2,29) = 20.323, p < 0.001). Motor FSMC was negatively associated with ADL scores, whereas higher balance (BBS) scores were associated with higher ADL scores.

Finally, the model for the REJ dimension revealed that hip IARA (β = −0.703, 95% CI −1.130, −0.277) was a significant predictor of this subscale, explaining 25% of the variance (R2 = 0.274, adjusted R2 = 0.250, F(1,30) = 11.336, p = 0.002).

All models showed independence of residuals (Durbin-Watson values between 1.7 and 2.2) and did not present multicollinearity issues (VIF < 1.1).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that health-related QoL, assessed with the MusiQoL-31, is significantly associated with biomechanical gait parameters and with clinical factors such as fatigue, postural balance, and cognitive performance in individuals with MS.

The observation that gait speed and cadence correlate positively with the ADL dimension is consistent with previous research identifying these parameters as key predictors of functional status and fall risk in this population [56,57,58,59]. For instance, Pau et al. reported that reduced gait speed and the presence of kinematic asymmetries were associated with greater functional deterioration [28]. Our data reinforce this evidence by showing that joint asymmetry—specifically the knee asymmetry measured by the Gait Relative Asymmetry Index—is also related to specific aspects of QoL, including both the ability to perform ADL and the perception of social rejection.

Fatigue, in both its motor and cognitive components, exhibited the strongest correlations with the various dimensions assessed by the MusiQoL questionnaire. This finding aligns with existing evidence describing fatigue as one of the most frequent and disabling symptoms of MS, profoundly impacting functional independence as well as physical and mental performance [60]. As noted by Weiland et al. [20], the presence of fatigue is associated with poorer performance in daily activities and an increased risk of falls, both of which directly affect perceived well-being. In line with these findings, our results revealed a marked negative relationship between motor fatigue scores and the ability to carry out daily tasks independently, underscoring the need to address this symptom comprehensively in clinical practice.

Regarding balance, our results show that scores on the BBS are positively correlated with the ability to manage daily tasks. This observation is consistent with the findings of Fritz et al. [22], who demonstrated that dynamic balance has a significant impact on gait speed and overall functional capacity. Clinically, this can be explained by the fact that better postural control enables safer transitions during ambulation—such as turning, changing direction, or adapting to uneven surfaces—thereby enhancing autonomy and reducing the risk of falls in everyday environments.

Furthermore, the time required to complete the TMT was associated with lower QoL scores. This result aligns with prior studies highlighting the role of cognitive slowing in the planning and execution of functional activities [17,29]. From a clinical perspective, reduced processing speed and diminished cognitive flexibility make it more difficult to organize motor sequences and make rapid decisions, increasing the mental effort required for routine tasks. This, in turn, can lead to frustration, greater dependency, and ultimately a reduced perception of well-being.

Interestingly, knee joint asymmetry was also associated with the social rejection dimension. While previous studies have focused mainly on the functional implications of gait asymmetry, particularly its association with disability and fall risk [19,28], its potential psychosocial impact has received little attention. In this regard, the present study contributes by linking an objective kinematic parameter to a subjective domain of QoL, suggesting that visible gait alterations may influence self-perception and social interactions, thereby contributing to feelings of stigma or social withdrawal [38,39].

The identification of specific kinematic parameters linked to different aspects of QoL suggests that rehabilitation approaches for individuals with MS should not only consider gait speed and cadence but also gait symmetry and the cognitive and emotional factors influencing motor performance. From a clinical perspective, a deeper understanding of how these gait characteristics interact with fatigue, balance, and cognitive function can help refine therapeutic strategies and make them more individualized. The use of three-dimensional motion capture systems such as Vicon® contributes to this goal by providing precise, objective data that improve our understanding of gait alterations and their impact on functional independence and well-being.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to establish causal relationships between the variables analyzed. In addition, the sample included individuals with different clinical forms of MS, and there was no control group for comparison with healthy subjects or other populations. Assessments were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to real-world settings, and external variables such as ongoing pharmacological treatments were not considered. Moreover, the relatively small sample size (n = 32), predominantly composed of women, and the inclusion of heterogeneous clinical phenotypes (RRMS, PPMS, SPMS) may have introduced variability and limited the possibility of performing subgroup analyses by sex or MS type without compromising statistical power. However, the use of a validated and reliable optical motion capture system (Vicon®) contributes to the methodological consistency of the kinematic data.

In addition, as the study included participants who were able to walk independently or with the aid of assistive devices, the findings may not be generalizable to individuals with more advanced disability or those unable to perform gait assessments. As this was an exploratory study involving multiple correlations, the results should be interpreted cautiously, as they require confirmation in larger samples. Nevertheless, the results are largely consistent with previous studies and provide a solid foundation for future longitudinal research with greater statistical power to further explore the relationships between biomechanical parameters, clinical factors, and QoL in this population.

5. Conclusions

QoL in individuals with MS is strongly influenced by both biomechanical gait parameters and clinical factors such as fatigue, postural balance, and cognitive performance. Specifically, gait speed, cadence, and knee joint symmetry were associated with the ability to perform ADL, while motor and cognitive fatigue emerged as the most relevant predictors of reduced overall well-being. Moreover, executive function and postural stability played a decisive role in functional autonomy. Importantly, regression models explained up to 58.4% of the variance in the ADL dimension, underscoring that these combined factors account for a substantial proportion of QoL outcomes. These findings highlight the importance of comprehensive assessments to better inform physiotherapeutic interventions aimed at improving daily functioning and overall QoL in this population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/s25226909/s1, Table S1: Correlations between MusiQoL-31 and its dimensions and the biomechanical variables. Table S2: Correlations between MusiQoL dimensions and independent variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M., C.E.-B., M.G.-A., M.G.-G. and A.-M.U.-O.; methodology, M.-J.G., R.L.-G. and Á.G.-d.-l.-F.; software, R.L.-G. and Á.G.-d.-l.-F.; validation, O.M., M.G.-A., A.-M.U.-O. and M.G.-G.; formal analysis, M.-J.G., C.E.-B., Á.G.-d.-l.-F. and R.L.-G.; investigation, O.M., C.E.-B., M.G.-A., M.G.-G., A.-M.U.-O. and R.L.-G.; data curation, O.M., C.E.-B., M.G.-A., M.G.-G., A.-M.U.-O. and R.L.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M., C.E.-B., M.G.-A., M.G.-G., A.-M.U.-O. and M.-J.G.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, M.-J.G., Á.G.-d.-l.-F., M.G.-A. and C.E.-B.; resources, R.L.-G.; supervision, O.M., C.E.-B. and M.G.-A.; project administration, C.E.-B. and M.G.-A.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos (Project identification code ECL.24/753-E_Tesis) on 27 November 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets supporting reported results are available upon request to the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mohammed, E.M.A. Understanding Multiple Sclerosis Pathophysiology and Current Disease-Modifying Therapies: A Review of Unaddressed Aspects. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, E.M.A. Multiple sclerosis is prominent in the Gulf states: Review. Pathogenesis 2016, 3, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, R.; Giovannoni, G. Multiple sclerosis—A review. Euro. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, E.; Wei, L.; Dai, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhou, S.; Huang, Y. NINJ1: A new player in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis and potential therapeutic target. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 141, 113021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassmann, H. Multiple Sclerosis Pathology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a028936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charabati, M.; Wheeler, M.A.; Weiner, H.L.; Quintana, F.J. Multiple sclerosis: Neuroimmune crosstalk and therapeutic targeting. Cell 2023, 186, 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haki, M.; Al-Biati, H.A.; Al-Tameemi, Z.S.; Ali, I.S.; Al-Hussaniy, H.A. Review of multiple sclerosis: Epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Medicine 2024, 103, e37297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milo, R.; Kahana, E. Multiple sclerosis: Geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010, 9, A387–A394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, F.; Jhaveri, S.; Avanthika, C.; Singh, A.; Jain, N.; Gulraiz, A.; Shah, P.; Nasir, F. Impact of Vitamin D Supplementation on Multiple Sclerosis. Cureus 2021, 13, e18487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynedal, B.; Duvefelt, K.; Jonasdottir, G.; Roos, I.M.; Åkesson, E.; Palmgren, J.; Hillert, J. HLA-A Confers an HLA-DRB1 Independent Influence on the Risk of Multiple Sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Clarelli, F.; Pignolet, B.; Mascia, E.; Sorosina, M.; Misra, K.; Ferrè, L.; Bucciarelli, F.; Manouchehrinia, A.; Moiola, L.; et al. Vitamin D affects the risk of disease activity in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2025, 96, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiner, T.G.; Genes, T.M. Obesity and Multiple Sclerosis—A Multifaceted Association. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arneth, B. Multiple Sclerosis and Smoking. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakimovski, D.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Ramanathan, M.; Dwyer, M.G.; Zivadinov, R. Infections, Vaccines and Autoimmunity: A Multiple Sclerosis Perspective. Vaccines 2020, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; van Der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, B.M.; Noseworthy, J.H. Multiple Sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2002, 53, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskuhl, R.; Itoh, Y. The X factor in neurodegeneration. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219, e20211488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socie, M.J.; Sosnoff, J.J. Gait Variability and Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Int. 2013, 2013, 645197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, T.J.; Jelinek, G.A.; Marck, C.H.; Hadgkiss, E.J.; van der Meer, D.M.; Pereira, N.G.; Taylor, K.L. Clinically Significant Fatigue: Prevalence and Associated Factors in an International Sample of Adults with Multiple Sclerosis Recruited via the Internet. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.G.; Piperno, R.; Simoncini, L.; Bonato, P.; Tonini, A.; Giannini, S. Gait abnormalities in minimally impaired multiple sclerosis patients. Mult. Scler. 1999, 5, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, N.E.; Marasigan, R.E.R.; Calabresi, P.A.; Newsome, S.D.; Zackowski, K.M. The Impact of Dynamic Balance Measures on Walking Performance in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neamtu, M.C.; Neamtu, O.M.; Marin, M.I.; Rusu, L. Morphofunctional muscle changes influence on foot stability in multiple sclerosis during gait prediction: The rehabilitation potential. BMR 2018, 31, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.C.; Guerrieri, S.; Dalla Costa, G.; Pisa, M.; Leccabue, G.; Gregoris, L.; Comi, G.; Leocani, L. Intensive Neurorehabilitation and Gait Improvement in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical, Kinematic and Electromyographic Analysis. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzięcioł-Anikiej, Z.; Malinowska, P.; Daunoraviciene, K.; Pauk, J.; Kułakowska, A.; Dardzińska-Głębocka, A.; Sulewska, A. Quantitative parameters of gait imbalance in multiple sclerosis patients. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2022, 24, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inojosa, H.; Schriefer, D.; Klöditz, A.; Trentzsch, K.; Ziemssen, T. Balance Testing in Multiple Sclerosis—Improving Neurological Assessment with Static. Posturography? Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayvat, E.; Doğan, M.; Ayvat, F.; Kılınç, Ö.O.; Sütçü, G.; Kılınç, M.; Yıldırım, S.A. Usefulness of the Berg Balance Scale for prediction of fall risk in multiple sclerosis. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2801–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, M.; Coghe, G.; Corona, F.; Marrosu, M.G.; Cocco, E. Effect of spasticity on kinematics of gait and muscular activation in people with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 358, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, C.; Lommers, E.; Delrue, G.; Gester, E.; Maquet, P.; Collette, F. The Complex Interplay Between Trait Fatigue and Cognition in Multiple Sclerosis. Psychol. Belg. 2022, 62, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, O.; Fernández, V.; Baumstarck-Barrau, K.; Muñoz, L.; Gonzalez Alvarez, M.D.; Arrabal, J.C.; León, A.; Alonso, A.; López-Madrona, J.C.; Bustamante, R.; et al. Validation of the spanish version of the multiple sclerosis international quality of life (musiqol) questionnaire. BMC Neurol. 2011, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulde, P.; Hermsdörfer, J.; Rieckmann, P. Sensorimotor function does not predict quality of life in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 52, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, J.E.; Sandroff, B.; Bamman, M.; Motl, R.W. Motion sensors in multiple sclerosis: Narrative review and update of applications. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2017, 14, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drebinger, D.; Rasche, L.; Kroneberg, D.; Althoff, P.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Weygandt, M.; Paul, F.; Brandt, A.U.; Schmitz-Hübsch, T. Association Between Fatigue and Motor Exertion in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis—A Prospective Study. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, J.; Lencioni, T.; Gervasoni, E.; Crippa, A.; Anastasi, D.; Carpinella, I.; Rovaris, M.; Cattaneo, D.; Ferrarin, M. Improved Gait of Persons with Multiple Sclerosis After Rehabilitation: Effects on Lower Limb Muscle Synergies, Push-Off, and Toe-Clearance. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.B.; Õunpuu, S.; Tyburski, D.; Gage, J.R. A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1991, 10, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa Moreno, A.; Gutiérrez Gutiérrez, E.; Pérez Moreno, J.C. Consideraciones para el análisis de la marcha humana. Técnicas de videogrametría, electromiografía y dinamometría—Considerations for human gait analysis. Rev. Ing. Bioméd. 2008, 2, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiakiri, A.; Plakias, S.; Giarmatzis, G.; Tsakni, G.; Christidi, F.; Papadopoulou, M.; Bakalidou, D.; Vadikolias, K.; Aggelousis, N.; Vlotinou, P. Gait Analysis in Multiple Sclerosis: A Scoping Review of Advanced Technologies for Adaptive Rehabilitation and Health Promotion. Biomechanics 2025, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, C.G.; Baker, W.L.; Sidovar, M.F.; Coleman, C.I. Walking speed and health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Patient 2014, 7, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larocca, N.G. Impact of walking impairment in multiple sclerosis: Perspectives of patients and care partners. Patient 2011, 4, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de Protección de Datos Personales y Garantía de los Derechos Digitales; Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2018-16673 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, N.E.; Newsome, S.D.; Eloyan, A.; Marasigan, R.E.R.; Calabresi, P.A.; Zackowski, K.M. Longitudinal relationships among posturography and gait measures in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2015, 84, 2048–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalron, A.; Nitzani, D.; Achiron, A. Static posturography across the EDSS scale in people with multiple sclerosis: A cross sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2016, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysogorskaia, E.; Ivanov, T.; Mendalieva, A.; Ulmasbaeva, E.; Youshko, M.; Brylev, L. Yoga vs Physical Therapy in Multiple Sclerosis: Results of Randomized Controlled Trial and the Training Protocol. Ann. Neurosci. 2023, 30, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perucca, L.; Scarano, S.; Russo, G.; Robecchi Majnardi, A.; Caronni, A. Fatigue may improve equally after balance and endurance training in multiple sclerosis: A randomised, crossover clinical trial. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1274809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggieri, S.; Bharti, K.; Prosperini, L.; Giannì, C.; Petsas, N.; Tommasin, S.; Giglio, L.D.; Pozzilli, C.; Pantano, P. A Comprehensive Approach to Disentangle the Effect of Cerebellar Damage on Physical Disability in Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.O.; Herzog, W.; Nigg, B.M. Use of force platform variables to quantify the effects of chiropractic manipulation on gait symmetry. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 1987, 10, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Scataglini, S.; Abts, E.; Van Bocxlaer, C.; Van den Bussche, M.; Meletani, S.; Truijen, S. Accuracy, Validity, and Reliability of Markerless Camera-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems versus Marker-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems in Gait Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Penner, I.; Raselli, C.; Stöcklin, M.; Opwis, K.; Kappos, L.; Calabrese, P. The Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FSMC): Validation of a new instrument to assess multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. Mult. Scler. 2009, 15, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Casanova, J.; Quiñones-Úbeda, S.; Quintana-Aparicio, M.; Aguilar, M.; Badenes, D.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Torner, L.; Robles, A.; Barquero, M.S.; Villanueva, C.; et al. Spanish Multicenter Normative Studies (NEURONORMA Project): Norms for Verbal Span, Visuospatial Span, Letter and Number Sequencing, Trail Making Test, and Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2009, 24, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, T.; Young, H.J.; Lai, B.; Wang, F.; Kim, Y.; Thirumalai, M.; Tracy, T.; Motl, R.W.; Rimmer, J.H. Comparing the Convergent and Concurrent Validity of the Dynamic Gait Index with the Berg Balance Scale in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Healthcare 2019, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, B.T.; Ingraham, B.A.; Pitluck, M.C.; Woo, D.; Ng, A.V. Reliability and Validity of Ratings of Perceived Exertion in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Kupper, L.L.; Nizam, A.; Rosenberg, E.S. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Caronni, A.; Gervasoni, E.; Ferrarin, M.; Anastasi, D.; Brichetto, G.; Confalonieri, P.; Di Giovanni, R.; Prosperini, L.; Tacchino, A.; Solaro, C.; et al. Local Dynamic Stability of Gait in People with Early Multiple Sclerosis and No-to-Mild Neurological Impairment. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, M.D.; Marrie, R.A.; Cohen, J.A. Evaluation of the six-minute walk in multiple sclerosis subjects and healthy controls. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Xi, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, X.; Lv, Y.; Hou, X.; Yu, L. Effects of exercise in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1387658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Pérez, I.; Sánchez-Alcalá, M.; Nieto-Escámez, F.A.; Castellote-Caballero, Y.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Osuna-Pérez, M.C. Virtual Reality-Based Therapy Improves Fatigue, Impact, and Quality of Life in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2021, 21, 7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, I.K.; Bechtel, N.; Raselli, C.; Stöcklin, M.; Opwis, K.; Kappos, L.; Calabrese, P. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Relation to depression, physical impairment, personality and action control. Mult. Scler. 2007, 13, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).