Abstract

The human voice is an important medium of communication and expression of feelings or thoughts. Disruption in the regulatory systems of the human voice can be analyzed and used as a diagnostic tool, labeling voice as a potential “biomarker”. Conversational artificial intelligence is at the core of voice-powered technologies, enabling intelligent interactions between machines. Due to its richness and availability, voice can be leveraged for predictive analytics and enhanced healthcare insights. Utilizing this idea, we reviewed artificial intelligence (AI) models that have executed vocal analysis and their outcomes. Recordings undergo extraction of useful vocal features to be analyzed by neural networks and machine learning models. Studies reveal machine learning models to be superior to spectral analysis in dynamically combining the huge amount of data of vocal features. Clinical applications of a vocal biomarker exist in neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, psychological disorders, DM, CHF, CAD, aspiration, GERD, and pulmonary diseases, including COVID-19. The primary ethical challenge when incorporating voice as a diagnostic tool is that of privacy and security. To eliminate this, encryption methods exist to convert patient-identifiable vocal data into a more secure, private nature. Advancements in AI have expanded the capabilities and future potential of voice as a digital health solution.

1. Introduction

The human voice is a multifaceted and vital tool for interpersonal communication, facilitating natural and efficient interactions between individuals. It serves as a primary means of exchanging information and allows us to engage in authentic and meaningful social interactions. With a complex array of sounds produced by the vocal cords, the voice carries a wealth of information that enables us to convey emotions or fear, share feelings, and communicate excitement [1]. In the realm of voice analysis, several key parameters are commonly assessed to evaluate voice quality and characteristics. Voice assessment can be assessed subjectively or objectively. Subjective assessment can be performed by grading voice on overall quality (G), roughness (R), breathiness (B), asthenia (A), and strain (S) (the GRBAS scale) [2]. Objective assessment involves the evaluation of multiple acoustic parameters, essentially of four types: glottal features, including information on how the sound is articulated at the vocal cords; tempo-spectral features, comprising acoustic features used in musical information retrieval; formants, including information about the resonance of the vocal tract; and lastly, physical attributes, such as pitch, magnitude, and mean [1,2]. Through voice examination, we gain insights into an individual’s vocal cord characteristics. Voice analysis has found applications in diverse fields, such as speech pathology, forensic investigation, and emotion recognition systems, highlighting its significance in numerous domains [3].

The advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution has brought forth numerous impactful technologies and artificial intelligence, which have seamlessly integrated into our daily lives and found themselves an especially important place in the medical domain, transforming the scope of medical diagnosis [1]. The introduction of virtual/vocal assistants in smartphones and smart home devices has significantly increased the use of voice-controlled search. In 2019, approximately 31% of smartphone users worldwide utilized voice technology at least once a week, and voice searches accounted for 20% of queries on Google’s mobile app and Android devices [1]. Conversational artificial intelligence (CAI) is at the core of these voice-powered technologies, enabling intelligent interactions between machines such as computers and voice-enabled devices and users through voice and voice user interfaces (VUIs). This convergence of voice technology and artificial intelligence (AI) has made it possible for machines to interact with users in a sophisticated manner. It is now possible to use such technology conjoined with neural networks in analyzing and assessing key vocal parameters, simply at the touch of a smartphone recorder [4]. Adding on, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the use of video or phone consultations over office visits, benefiting patients who cannot travel or have limited access to medical professionals [3,4].

Speech has been studied extensively in relation to diseases; however, using speech as a diagnostic tool is accompanied by limitations such as the requirement of some degree of language proficiency, accent, language, pathological and physiological influences, and exclusion of those with limited vocal capability. Focusing on voice overcomes these limitations, creating a wider, more inclusive patient population [4,5]. Voice analysis has been employed as a diagnostic tool and a noninvasive biomarker for a range of neuropsychiatric conditions, including Parkinsonism, major depressive disorder (MDD), and diseases like chronic cough associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), dyspnea, and even COVID-19 [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. However, these studies were limited by small sample size, uncertainties associated with sensor measurements, the potential for conscious vocalizing of patients, and unsupervised voice recordings [6,7,8,9,10]. A study conducted using smartphone recording data showed promising outcomes in accurately identifying Parkinson’s disease. This approach has the potential to revolutionize the screening and monitoring of Parkinson’s disease by providing a noninvasive and easily accessible method that utilizes commonly available smartphone technology [12]. Novel applications use phonetic characteristics of voice through machine learning (ML) algorithms to detect cardiac arrest outside of the hospital and to predict pulmonary function in asthma [13,14]. Other studies have explored the association between characteristics of voice signals and coronary artery disease (CAD), adverse outcomes in congestive heart failure (CHF), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and the progression of disease in COVID-19 patients [15,16,17,18,19]. Furthermore, analysis of voice has shown promise as a predictor of cognitive decline in vasculature-originated disorders such as diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and heart disease. These studies highlight the potential of voice analysis as a noninvasive and accessible method for detecting and monitoring cardiac and respiratory conditions [18].

There is a need for standardizing corpus collection and establishing a large-scale library of clinically available voice samples. Algorithm optimization, updates, and integration into user-friendly devices such as smartphone applications and connected medical devices are also crucial steps for the future development of vocal biomarkers [14,16,18]. The evolution of neural networks has unlocked numerous potential applications in healthcare. These include the analysis of voice for diagnosis, classification, patient remote monitoring, and improving clinical practices [1]. Expanding the clinical application of voice analysis through artificial intelligence to enable the diagnosis of broader pathologies is looming. It is important to note that no vocal biomarkers have been approved by regulatory agencies like the US Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency [20]. We review broader medical settings where vocal analysis can prove to be beneficial.

2. The Mechanics of Voice

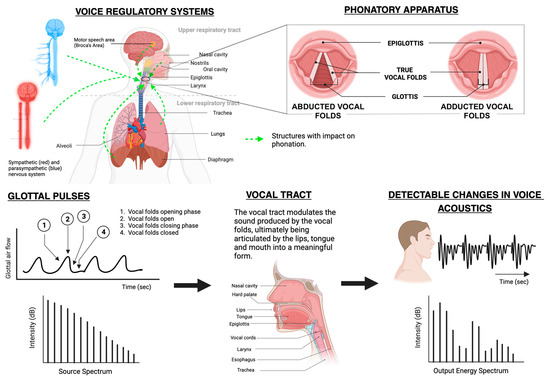

Human voice production is a complex mechanism resulting from fluid structure and acoustic interactions between the anatomy and vibration of vocal cords, activation of laryngeal muscles, and geometric properties of the lungs [21].

2.1. Anatomy and Physiology of Voice

The vocal system comprises the vocal folds, vocal tract, lower airways, and the lungs. The lower respiratory tract and lungs supply airflow and pressure modulated by the vibrations of vocal folds, and a voice source is produced. This voice source is then modified by the vocal tract to generate distinct output sounds [21]. The subsequent activation of the five intrinsic laryngeal muscles—namely, the interarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid, posterior cricoarytenoid, cricothyroid, and thyroarytenoid—facilitate the adduction/abduction and geometry of the vocal cords to produce sounds [21]. Additionally, the contraction and relaxation of laryngeal muscles regulate the length and tension of vocal cords, leading to alterations in vocal cord tension, which is imperative for voice modulations [21].

A subglottal pressure builds up due to the initiation of airflow caused by lung contractions. When this pressure crosses the required threshold pressure, the vocal cords are pushed apart, allowing the air to escape [22]. As a result of this action, a negative pressure is created in the glottal region. The elastic recoil property of the vocal cords along with the glottal negative pressure leads to the closure of the glottis. The repetition of this cycle causes the vocal cords to vibrate incessantly. Due to these vibrations, the glottal airflow is modulated into a pulsatile flow, which further evolves into a turbulent flow [22]. The vocal sounds thus produced are articulated with the help of the tongue, teeth, lips, and palate to produce consonants and vowels as signaled by the speech areas of the brain cortex: the Broca’s and the Wernicke’s area. These regions facilitate the formation of words and sentences and ensure fluency and coherency of speech [23].

The degree of approximation of vocal folds, in association with the closure of the glottis and the rate of glottal airflow, determines the quality of voice: breathy, strained, or neutral [24]. Incomplete adduction leads to enhanced turbulent flow through the vocal folds in the presence of high airflow rates, generating a breathy voice. On the contrary, when the vocal cords are in complete approximation, the low airflow rates with peaked subglottal pressure lead to the generation of a strained or pressed voice. The neutral or normal speaking voice is produced due to reduced subglottal pressure in association with reduced airflow rates [24,25]. Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the mechanics of voice.

Figure 1.

Mechanics of voice production [26].

2.2. Properties of the Human Voice

Table 1.

Commonly used vocal parameters.

3. Vocal Analysis Methods

The human voice is a rich source of easily collectable and analyzable high-dimensional data. It has become possible to extract vocal features such as energy, spectrum, and waveform as well as perturbation features [31].

The initial step in creating a digital health solution involves data collection. Voice recordings can include reading a uniform text, counting, spontaneous vocal tasks, and nonverbal phonation such as coughing, breathing, or vowel vocalization [32]. Sustained vowel vocalization has been found superior due to its uniformity; language-independent nature; and the elimination of bias risk from articulatory influences of accent, speaking rates, stress, modulations, and any variable between languages [17,33]. Added benefits of no training prerequisite and stability of analysis are seen [34]. A study of the better vowel for articulation revealed that the vowel /z/ requires precise control over the air gap between the tongue and hard palate with proper positioning and shaping of the lips. The commonly used vowel /a/ demands less precise control, with the jaw open and the tongue at its lowest [17]. The vowel /e/, however, can be achieved even by those with facial palsy or tongue deviations due to the unrounded lips and mid-tongue position [35].

The ideal audio file format is WAV; however, most studies recorded audio files in MP3 format and later used Praat to enhance the file and boost the data quality [26]. Maryn et al. showed the Multi-Dimensional Voice Program (MDVP) to yield higher results than Praat [36]. Raw audio files are preprocessed using methods like standardization, multicollinearity, and dimensional reduction to improve quality before being fed to deep learning (DL) or machine learning (ML) models such as support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), or Naïve Bayes (NB) [32,37,38]. Vocal features can be extracted using Munich Open-Source Media Interpretation by Large Feature-Space Extraction (OpenSMILE), widely studied to extract numerous features such as frame energy, MFCC, loudness, jitter, and shimmer for processing and ML applications [33]. In ML applications, the most crucial features are selected through Least Absolute Shrinkage Selection Operator (LASSO), minimum redundancy maximum relevance, Relief and Local Learning-Base Feature Selection (LLBFS) [38]. Although transfer learning is efficient for small datasets, traditional ML algorithms are powerful for voice analysis for small datasets [3,32,37]. SVM has certain limitations such as limited computation time with large datasets and mathematical complexity [33]. DL models such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are alternatives to ML for larger datasets due to their success in categorized feature selection and in identifying patterns [37,38].

Vocal biomarkers must undergo authentication of audio quality as well as analytical and clinical validation in order to be defined as a vocal biomarker. After validation, biomarkers can be embedded into digital health solutions such as smartphone apps, chatbots, or voice assistants [32]. Home recordings in natural conditions revealed lower accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of ML models in detecting vocal abnormalities [37,39]. Carefully constructed datasets in controlled recording environments with efficient preprocessing and fine-tuning of algorithms are fundamental for effective analysis [37].

DL and ML models utilized over the past 10 years in voice analytics for various applications are presented in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 [3,6,7,8,9,10,11,13,15,16,17,19,20,26,33,34,35,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

Table 2.

Voice analytical methods using artificial intelligence in neurological disorders.

Table 3.

Voice analytical methods using artificial intelligence in mood disorders.

Table 4.

Voice analytical methods using artificial intelligence in pulmonary disorders.

Table 5.

Voice analytical methods using artificial intelligence in cardiac disorders.

Table 6.

Voice analytical methods using artificial intelligence to be mentioned.

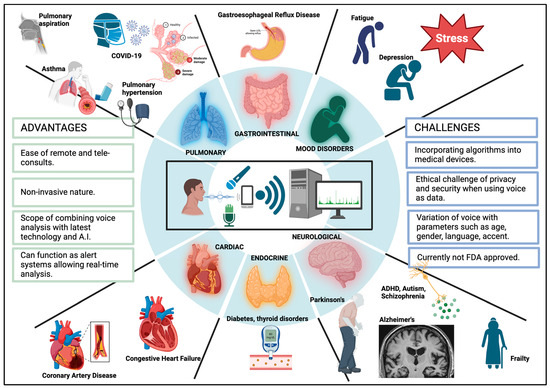

4. Clinical Implications of Voice

Recent research studies have shown the analysis of variations in voice across various medical conditions to diagnose diseases. AI can explore these multidimensional data [57]. Owing to the development of neural networks, we are now able to analyze voice in ways we could not before. Currently, there are no FDA-approved digital voice analytical technologies for clinical purposes, as it is an emerging field and needs more data [58]. Voice biomarkers could help detect certain diseases at early stages for treatment. Various research has been performed using voice analytics to detect neuropsychiatric, cardiac, pulmonary, gastroenterology and endocrine diseases.

4.1. Neuropsychiatric Diseases

4.1.1. Parkinson’s Disease

PD is a neurological condition leading to disability, with increasing prevalence compared with other neurological disorders [59]. PD most commonly affects the elderly, with symptoms beginning gradually and worsening over time. With disease progression, patients have memory difficulty, ambulatory issues, speaking and sleep disturbances, and behavioral changes. The standard diagnosis of PD is based on history and clinical symptoms [60]. The literature suggests voice impairment is the earliest sign of motor dysfunction in PD and can manifest in the earliest stages of the disease, worsening with disease severity [9,61]. The correlation between anatomy and physiology in voice impairment in PD has been investigated with various methods such as laryngoscopy, photoglottography, and laryngeal electromyography [61]. Spectral analysis of the voice of PD patients revealed abnormalities such as decreased f0, HNR, and increased jitter and shimmer [9]. Rhonda J et al. examined the voice characteristics of patients with PD according to the disease severity. The study was conducted on 30 early-stage PD and 30 late-stage PD patients. The voices of both groups demonstrated lower mean intensity levels and reduced maximum phonation frequency ranges compared with normal. Patients with late-stage PD had tremors as the main voice feature [62]. Similarly, Harel et al. conducted a case–control study on variability in the frequency of speech of a single individual over 11 years in prodromal PD. The results suggested that changes in variability in speech and acoustic measures can be detected as early as 5 years prior to diagnosis with other methods [63].

The challenges in early diagnosis of PD have inspired the development of ML models using voice data of these patients to detect the disease and its prognosis. Timothy J et al. applied different ML models to classify PD using the mPower Voice dataset and compared it with controls [64]. Using 65,000 10 s voice samples from 6000 people saying /ahh/, it was seen that RF and SVM classifier models were able to differentiate between people with PD 85% of the time with 74% accuracy [64].

Benba et al. tried to differentiate between 20 HCs and 20 patients with PD. Sustained vowels /a/, /o/, and /u/ were collected from subjects, and linear and nonlinear feature extraction were used to obtain the most effective acoustic features for classification. SVM was used for classification, with 87.50% accuracy in differentiating between the two groups [65]. B.E. Sakar et al. compiled voice samples, sound types, sustained vowels, words, and sentences to have a dataset to develop a predicting telemonitoring model for PD. Using time frequency-based feature extraction, the voice samples were grouped into various parameters like frequency, pulse, amplitude, voicing, pitch, and harmonicity. These were fed into SVM and KNN classifiers, which concluded that sustained vowels carried more discriminative information than words and short sentences in PD [66].

Suppa et al. performed an extensive study comparing 30 vocal features between HCs and PD patients, PD patients of early vs. mid-stage disease, PD patients with ON and OFF therapy, and the effect of L-Dopa on voice. They developed an ML model using an SVM classifier and ANN and were successful enough to accurately differentiate the said cohorts. Of the early-stage PD patients, 32% did not display overt voice impairments, which were, however, reported through the ML model, strengthening the prospect of subclinical voice dysfunction recognition. A positive relation between likelihood ratio values computed from the ML model between disease and voice impairment was established, making it a reliable score to dictate voice dysfunction. L-Dopa was seen to have improving outcomes on voice, with an inferior degree of improvement of motor symptoms [9]. These studies suggest that voice can be used as a biomarker to diagnose PD with the help of AI. Further studies with a larger dataset and validation are required to bring this into clinical practice.

4.1.2. Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia worldwide [67]. The National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA–AA) have suggested criteria for the diagnosis of AD according to symptoms and functional impairment. However, definitive diagnosis is based on histopathological examination, which is rarely performed in clinical practice, not to mention being invasive [68]. Early diagnosis of AD is crucial, as it helps patients and caregivers plan for appropriate lifestyle changes to improve quality of life. Various studies have identified the relation between speech changes and AD; however, there is very little information on changes in voice.

With recent advancements in ML, it is possible to explore the acoustic changes in voice for early detection of AD. Cognitive impairment, being an important presentation of AD, can be studied through voice. Mahon et al. studied 10-year cognitive changes from participants of the MIDUS who had completed cognitive testing. The subjects’ age ranged from 42 to 92 years, with an average education of 14.57 years out of 20. The study found increased jitter with higher declines of episodic memory, verbal fluency, and attention switching. Deterioration of episodic memory was also related to lower pulse (p = 0.038) and fewer voice breaks (p < 0.001). Hence, studying changes in voice could be a predictor of early cognitive impairment, aiding in the diagnosis of AD [27]. Another study conducted an acoustic analysis to identify acoustic parameters in AD and their relation to the anomic impairment. The recorded voice samples were analyzed by the Praat 5.1.4231 program for variables like amplitude disturbance, resonance, and noise disturbance. The study results showed a direct relationship between these acoustic parameters and verbal fluency in AD [69]. ML-based diagnostic models to diagnose AD have been developed, but these models were developed using MRI scan databases [70]. Improved ML models can augment diagnosis at an early stage.

4.1.3. Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD)

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition manifesting in children and characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity [71]. There is evidence that there are neuroanatomical and functional changes that cause these symptoms. Currently, the diagnosis of ADHD is primarily by clinical evaluation based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria [72]. Recent studies have mentioned the alterations in voice and speech of patients with ADHD. Studies suggest differences in vocal parameters in children with ADHD vs. normal children [73].

Several review studies summarized ML- and DL-based diagnostic methods for ADHD. Most of these studies have ML models developed using MRI, EEG, physiological signals, motion data, and genetic data, but lack studies using voice analytics with ML models, though research in this domain is steadily increasing [74]. Von Polier et al. used an ML-based approach to determine the difference in prosodic voice features between healthy and ADHD patients. Paralinguistic features based on F0 and loudness were analyzed and filtered prior to classification. RF classifications using Tree-Bagger algorithms were able to differentiate ADHD patients from HCs. Increased loudness, hoarseness, and breathiness were seen in ADHD patients compared with HCs. Particularly, those with combined ADHD were louder, had lower F0, more strained voices, and more hoarseness as well as breathiness. This study suggested that voice analysis is promising in diagnosing ADHD [75]. Further research with additional voice features in a larger cohort can improve the classification performance.

4.1.4. Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopment disorder associated with behavioral issues, with almost one-third of children intellectually and verbally disabled. Diagnosis is clinically based on communication issues and restrictive and repetitive patterns [76]. Children with ASD mostly develop speech disturbances, but half of these children have distinctive acoustic patterns. They exhibit abnormal voice quality and prosody. A study on pitch variability in the voices of autistic children found that these children had a shallower and less harmonic structure. Abnormal auditory feedback or instability in the mechanisms that control pitch can cause this variability [77]. These atypical vocal characteristics can be used as biomarkers for the early diagnosis of ASD. A systematic review of acoustic patterns in ASD showed that the ML domain can provide promising results for the diagnosis of ASD [77,78].

Asgari et al. developed an ML model that translates prosodic abnormalities into automated, measurable quantities. They developed a harmonic model (HM) using a voice signal and computed a set of quantities related to the harmonic content. They used pitch-related features and employed feature selection to isolate informative prosodic measures. There was a significant association between pitch and loudness with the severity of autism, facilitating the differentiation of autism from HCs [79]. These studies show that ML models using voice patterns can help diagnose autism in younger children with minimal or no language.

4.1.5. Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a severe neuropsychiatric disorder that occurs in early adulthood, causing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral disturbances with reduced life expectancy [80]. Currently, the diagnosis of SZ is subjective and primarily clinical, with significant symptoms identified by expert physicians. New technologies to reduce the misdiagnosis caused by behavior-based presentations have been attempted [26,81]. Various studies have shown the usage of AI techniques in diagnosing SZ using EEG and MRI findings [80,82]. An overview of AI techniques based on MRI findings has mentioned challenges such as the overlap of MRI findings with those of other neurological disorders and the time-consuming and complicated nature [80].

Atypical voice patterns are seen in SZ, such as increased pauses, distinctive tone, and pitch with varied intensities. These features can be used to develop ML models to diagnose SZ at early stages. A meta-analysis on studies with ML models using acoustic features of SZ found that voice analytics can be promising yet challenging for diagnosis. Most studies used discriminant analysis and SVM to classify patients with SZ. More robust multivariant studies including linguistic aspects such as lexical choices and syntactic and semantic features can help develop better ML models in the future [83]. Compton et al. found that patients with aprosody exhibited reduced variability in pitch, jaw movements, tongue movements, and loudness in voice. The computer program VoiceSauce was used to extract the phonetic linguistic parameter of pitch, and WaveSurfer 1.8.8 was used to extract intensity readings. Praat was used to delineate the vowels from the voice recordings. On comparing these features, results suggested that computational methods can be used to quantify specific negative symptoms in SZ [84]. Voice and prosodic evaluations can help identify the severity of SZ and help diagnose SZ in the early stages.

4.1.6. Mood Disorders

Mood alterations can manifest in facial expressions and through voice; hence, analysis of voice could be of use [85]. Emotional state is primarily controlled by the limbic system; hence, speech mechanisms can be manipulated unknowingly by emotional arousal through the activation of the somatic, sympathetic, and parasympathetic nervous systems [86]. A study group developed a “vitality” index calculating the degree of mental health from voice. This is available as a smartphone/web application (Mind Monitoring System: MIMOSYS, PST Inc., Tokyo, Japan) to monitor mental health and identify mental disorders. The app recognizes changes in F0 to determine the extent of calmness, anger, joy, excitement, and sorrow. Due to diurnal variations, vitality in the morning was found to be more reliable for evaluating mood [85]. Anxiety can be identified as an increase in pitch variability due to trembling of the voice [46].

A study showed glottal acoustic features aided the discrimination accuracy of depressed compared with healthy adolescents [87]. An explanation for this stems from the fact that emotional stress is linked to supraglottal vortices/turbulences as well as psychomotor retardation, leading to increased vocal tract muscle tone and rigidity, evident as monotonous speech and poor articulation [86,87,88]. Differentiation of minor depression from MDD is evident by the lower tone and increased pitch variation in the latter [46].

In an attempt to predict suicidal risk in depression patients, formants and power trends were found to be the favoring vocal features of those at high risk. A pattern of increased formant frequencies and first formant bandwidth, decreased higher formant bandwidths, and glottal spectral slope flattening were associated with depression and suicidality [86,88]. Conversely, most other studies recognized higher energy at upper-frequency bands shifting to lower frequencies post-treatment [86]. Vocal jitter was high and F0 low in those with MDD and imminent suicide risk. The relation of jitter to suicidal risk is due to variations in heart rate and blood pressure, in turn affecting blood flow in the vocal cords, causing erratic vibrations as well as reduced motor unit activation leading to incoordination of the laryngeal muscles. F0 variation was more stressed in patients at the nearest risk of suicide [86].

4.2. Pulmonary Disease

There is a close connection between voice and the respiratory cycle, the analysis of which could potentially offer a solution in detecting and diagnosing pulmonary disease. Several studies have shown that vocal biomarkers can be incorporated to diagnose conditions like COPD, asthma, and COVID-19 [89].

4.2.1. Asthma

Asthma is an inflammatory disease of the airways, affecting all ages, that causes constriction of airways and unusual sounds when breathing [90,91]. Peak Flow Meters are used by patients with asthma for daily monitoring in order to record the severity of their condition. Such gadgets are very modest and easy to utilize, yet they need severe cleanliness, which harms the stream sensors simultaneously. It was recognized that pathological voices had higher degrees of jitter and lower levels of HNR [89]. In a study by Dogan et al. that evaluated voice quality in patients with mild-to-moderate asthma using both subjective and objective methods, MPT values were significantly shorter, and average shimmer values higher, for both sexes compared with controls. Female patients with asthma had higher average jitter values compared with sex-matched controls. There was also a significant difference in the VHI and GRB scales between the two groups. The study concluded that in asthmatic patients, MPT, frequency, and amplitude perturbation parameters were impaired, but the vital capacity and duration of illness did not correlate with these findings [92]. The vowel /i/ was a superior choice for speech-based asthma categorization, with a classification accuracy of 80.79% by Yadav et al., whereas wheeze was better for non-speech sounds [90].

4.2.2. COVID-19

Ever since the onset of the pandemic, remote or telemonitoring of COVID-19 patients has been investigated in multiple aspects. The development of remote physiological monitoring of symptoms or recovery of COVID-19 patients would be considered a breakthrough. AI can identify COVID-19 voice changes, which can be uplifted to create smartphone apps or remote monitoring devices as a digital health solution to safely as well as effectively monitor COVID-19 patients [89]. F0 was shown to be beneficial in assessing the normal functioning of the larynx, but shimmer, jitter, and noise in speech signals were symptomatic of pathological instabilities in vocal fold oscillations and inappropriate closure of vocal folds. RF was the most accurate approach for classifying healthy and pathological voices, with an accuracy of roughly 82% in the analysis of three vowels, /a/, /e/, and /o/, for each participant. When only the sound of the vowel /e/ was analyzed, the accuracy increased to 85%. It was also discovered that the vowel /e/ was the most accurate in identifying COVID-19 impacts on voice quality [6]. On the contrary, a study revealed that sustained phoneme features corresponding to vocal tract modulation (MFCC, formants, and VTL) and lung pressure stability (Intensity-SD) were sensitive to COVID-19 infection, and thus, could potentially be used as a COVID-19 biomarker when compared with vocal fold vibration features (jitter, shimmer, pitch, HNR, and NHR). The findings indicate that COVID-19 symptoms that influence laryngeal activity as well as the oral and nasal cavities cause the biggest change in the voice quality of prolonged phonemes. The characteristics retrieved from the vowel /i/ during the first three days following hospital admission were the most successful, with an SVM classification accuracy of 93.5% [17].

Vocal biomarkers are valuable for fatigue monitoring in COVID-19 patients. Voice qualities such as pitch, word duration, and timing of articulated sounds are affected by increased weariness. Consonant sounds that demand a high average airflow require more vocal adjustments due to exhaustion. The authors believe that using voice biomarkers in telemedicine technologies might enhance fatigue monitoring in persons with COVID-19 or long COVID-19 [3].

Researchers found that voice analysis has the potential to increase the accuracy of self-reported symptom-based screening methods for SARS-CoV-2 patients [49]. Some researchers, however, have questioned the relevance of vocal biomarkers for COVID-19 detection, and limitations include patients’ acceptability and readiness for this new technology, as well as health status, which influences adherence to the digital solution [31].

4.2.3. Aspiration

Park et al. used voice-recorded ML algorithms to categorize people with dysphagia who are at risk of tube feeding and post-stroke aspiration pneumonia. This study found that acoustic data acquired using a mobile device can assist in identifying post-stroke individuals who are at high risk of respiratory issues. The XGBoost multimodal model, which incorporated acoustic characteristics, age, weight, and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, had an AUC of 0.85 and a sensitivity level of 88.7% in the categorization of patients with tube feeding and a high risk of aspiration. APQ11, shimmer, and RAP were the most significant contributing variables among these metrics [34].

4.2.4. Pulmonary Hypertension

In a study by Sara et al., they evaluated vocal biomarkers and invasively measured indices for pulmonary hypertension. Using voice-processing techniques, a vocal biomarker was developed that retrieved 223 acoustic parameters from 20 s of speech, including MFCC, pitch and formant measures, jitter, shimmer, and loudness. Individuals with greater mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP > 35 mmHg) showed substantially higher mean voice biomarker readings than those with lower mean PAP. A one-unit increase in the mean voice biomarker was associated with a high PAP in multivariate logistic regression, implying a relationship between a noninvasive vocal biomarker and an invasively derived hemodynamic index related to PH. These findings might have significant clinical implications for telemedicine and remote monitoring of patients with pulmonary hypertension [19].

4.3. Gastrointestinal Diseases

When we consider gastrointestinal diseases, AI networks have shown impressive results in differentiating between benign and malignant lesions, analyzing GI images, and assessing histological diagnosis [93]. We extend the discussion of potential AI applications to voice analytics in gastrointestinal diseases.

In a study by Roldan-Vasco et al., they investigated the application of ML to extract voice attributes from sustained Spanish vowels to explore how swallowing difficulties impact phonation. F0, jitter, shimmer, APQ, PPQ, and energy were among the characteristics recovered. For each feature vector, statistical functions such as mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis were calculated. These characteristics gave information about the short-term and long-term variability of the voice signal. They were useful in recognizing changes caused by food or liquid residuals in the laryngeal vestibule [31].

In a study by Ayazi et al., voice parameters in normal subjects and GERD patients, as well as the effect of anti-reflux surgery on those parameters, were evaluated. The researchers used electroglottography to measure impedance across the voice cords as participants read a standardized text. Normal participants and GERD patients had their voice frequency, amplitude, and closed-phase ratio computed and compared. When compared with normal persons, patients with GERD exhibited much greater irregularity in both voice frequency and amplitude. After surgery, there was a considerable improvement in both voice frequency and amplitude in GERD patients. In conclusion, GERD impairs voice quality, and anti-reflux surgery reduces voice irregularity in reflux patients [94]. AI implementation would be effective as a noninvasive tool for GERD diagnosis, but it would need a larger store of voice data among GERD patients.

4.4. Diabetes Mellitus

DM is a metabolic disorder causing fluctuations in blood glucose levels. These physiological alterations may have implications on an individual’s voice quality. Hamdan et al.’s study, which surveyed 105 patients with T2DM, was one of the first attempts to identify vocal differences between HCs and those with T2DM [95,96].

Individuals with DM demonstrated diminished values in voice parameters including jitter, RAP, shimmer, APQ, smoothed APQ, and NHR when compared with HCs. These conclusions imply that diabetes has a negative impact on voice parameters, and it may assist in the potential identification and differentiation of healthy and pathological voices [97]. Pinyopodjanard et al. showed a significant difference in F0, lower in female diabetic patients compared with controls, through MDVP. This difference remained significant in female diabetic subgroups. However, LR analysis revealed that F0 was not able to predict the presence of diabetes effectively. F0 was found to be a poor predictor of diabetes [56].

Evaluation of vocal variables during episodes of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in type 1 diabetes-afflicted individuals was studied. In women, energy (E), amplitude of F0 (AF0), phonation probability (Voiced), formant frequency (F1, F4), residual-to-harmonic ratio (R2H), and harmonic-to-all-energy ratio (Fx3, Fx4) were significantly altered during hypoglycemia, whereas RAP and formant frequency F2 were significantly altered during hyperglycemia when compared with normoglycemia. In men, PERiods (PER), duration of fundamental PERiods (PERTime), Voiced, simple voice quality (SimpleQ), shimmer, APQ, F2, unharmonic-to-harmonics ratio (U2H), subharmonic-to-harmonic ratio (S2H), Fx2, and NHR evidenced differences during hypoglycemia, whereas PERTime, F1, harmonics perturbation quotients (HPQ), U2H, and Fx2 demonstrated significant variation during hyperglycemia (all p < 0.05) [98].

A potential relationship between voice characteristics and blood glucose levels has been suggested, but more research with larger datasets is required to confirm these findings and explore the potential application of voice analysis as a noninvasive tool for blood glucose assessment [98,99].

4.5. Cardiac Diseases

The influence of the cardiac system on phonation is attributed to the numerous blood arteries existing in the vocal folds. The cardiac cycle causes a physiological variation in F0. During systole, ejection of blood causes swelling of the muscular body of the vocal folds, narrowing the glottis, reducing the glottal closure time, and elevating F0. This physiological process causes cyclical F0 variation during normal phonation. Any condition affecting the heart rate and systolic rate will cause erratic F0 alterations [86].

Although well-established CAD risk markers such as Framingham-based models, ASCVD score, and the Systemic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) model exist, they fall short by not including a certain subset of patients with preclinical atherosclerosis, sedentary patients, and those with inflammatory disorders. They also consider only traditional risk factors such as hypertension and smoking status, which contribute to less than 70% of CAD cases. Utilizing voice as a supplement to existing markers will allow remote identification of those at risk as well as aid in the management of CAD, reducing the burden on healthcare systems [100]. LR analysis of MFCCs exhibited an association with CAD and voice [101].

Congestive heart failure (CHF) causes vocal fold and pulmonary edema owing to the fluid-retentive nature of the disease, leading to phonation alterations. CHF-related edema can be monitored by body weight; however, this occurs only toward the later stages. The extent of CHF edema required to alter the voice is relatively small compared with the extent required to increase body weight. Hence, collecting glottal, time, and frequency-domain glottal parameters and vocal tract, MFCCs, and acoustic features would provide crucial data. The study revealed that MFCCs had more diagnostic accuracy than glottal features [101]. Reddy et al. documented a more rounded glottal pulse and lower second pressure level (SPL) in CHF patients than in HCs, suggesting imperfect glottal closure leading to inappropriate leakage of air through the glottis, again strengthening the diagnostic value of glottal features [102]. A first-of-its-kind study documented an association between voice and adverse outcomes in CHF, including future hospitalizations and mortality. Acoustic features such as pitch, formant, jitter, shimmer, and loudness were used in creating a linear ML model [15]. The cepstral peak prominence (CPP) vocal parameter was linked to improvement in CHF symptoms post decompensation treatment [101]. There is a need for novel methods of detection of even the minutest decompensation of CHF, and voice analytics might just fill the gap.

4.6. Miscellaneous

There is a potential link between endocrinopathies and changes in voice function. The discovery of laryngeal receptors for sex hormones and thyroid hormones shows that alterations in voice may occur as a result of endocrine diseases [2].

A summary of various clinical settings in which vocal analysis can be employed is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Clinical implications of vocal analytics [26].

5. Challenges and Limitations

Using voice as a mode of diagnosis poses certain challenges. To ensure a smooth transition from research of voice technology to clinical practice, certain factors should be considered. Voice being a physiological parameter, it is influenced by language, accent, age, and culture-specific features, which could raise biases [1]. The ideal vocal biomarker integrated to form a digital health solution would be language- and accent-independent. Having said that, narrowing data collection to only vowels or sounds instead of sentences, words, or numbers would eliminate such influences. There is a need to improve natural language processing to understand and analyze vocal recordings [1]. An inevitable concern of recording voice is its identifiable nature, creating issues of privacy and security.

5.1. Technical Challenges

Identified challenges with vocal analysis include creating and sharing large databanks with high-quality audio recordings with clinical information and identifying vocal biomarker candidates. Proof-of-concept studies would prove effective. Ensuring audio data synchronization and standardization across studies, in addition to creating more universal accent-, age-, and culture-independent vocal biomarkers, is essential. This can be achieved through replication studies, which can also help to improve algorithm accuracy [1]. This would enable compatibility and transferability, allowing cross-comparisons. Incorporating algorithms into medical devices can be challenging, and qualitative studies with co-design sessions with end users and pilot studies could be beneficial. The embedment of algorithms into already existing IT or telehealth systems is yet to be determined, but it can be aided by randomized controlled trials and real-world evaluation studies [1].

5.2. Security, Privacy, and Ethical Challenges

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was introduced in 1996 to safeguard patient data under different subgroups that are considered Protected Health Information (PHI) [103]. Voiceprints are information that falls under the umbrella of PHI. Given that they can be used to determine an individual’s identity, demographics, ethnicity, and health status in the context of vocal biomarkers, voice data are regarded as sensitive information [1]. Article 4.1 of the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union (GDPR EU) states voice as non-anonymous data. It is important to include variable profiles and maintain transparency to minimize systemic biases. Data encryption and random splitting of data for independent processing can be used to address ethical concerns [1].

Methods of De-Identification

Audio de-identification or voice de-identification is the process of removing or altering personal information from audio recordings to protect the privacy of users. For the context of our research, audio de-identification aims to preserve the anonymity of patients while still allowing the analysis of their voice data for diagnostic purposes. This process involves several techniques to ensure privacy, enumerated in Table 7 [104,105,106,107,108].

Table 7.

Methods of deidentification of voice.

5.3. Other Challenges

- Lack of standardized methods of collecting acoustic data: It is recommended to use an omnidirectional head-mounted microphone distanced 4–10 cm from the lips and at an angle of 45–90° away from the mouth. This allows improved SNRs as well as consistent mouth–microphone distance [109]. As studied by Svec and Granqvist, the microphone should meet the following features, such as having a flat frequency response with a variation of less than 2 dB [110]. The noise level should range from 10 dB lower than the quietest sound to recording the loudest acoustics without clipping [110]. A microphone preamplifier should then augment the captured sound without altering the original signal. This analog signal can be converted to a digital signal through an internal high-quality computer sound card or with an external device, preferably the latter. Characteristics of these converters include a sampling rate of ≥44.1 kHz, minimum resolution of 16 bits, noise level of 10 dB or lower than the quietest sounds, and an adjustable gain to capture the loudest sound with minimal clipping [109,111]. The recommended audio file format is WAV, as it has no compression. The recording environment should be at least 10 dB weaker than the level of the quietest sound. A baseline recording of the background environment should be performed while the subject is quiet for 5 s. Soundproof rooms are preferred [109].

- Variability and noise: Human voices can exhibit significant variability due to factors like age, gender, speaking styles, accents, or variations in their vocal characteristics. These variations can make it difficult for the model to distinguish between disease-related characteristics and other naturally occurring factors [108].

- Training set size and quality: The model’s performance relies heavily on the quality and size of the training dataset. Insufficient or unbalanced data can result in biases or reduced accuracy. Obtaining a diverse and adequately sized dataset can be a challenge [108].

- The dataset should have a good mix of sounds from people with diseases as well as from people who are healthy and do not have any diseases to ensure the model is balanced and not biased toward any one side [1].

- Optimal design/user experience: There should exist smooth and painless integration of voice analyzing devices in the daily life routine of patients, particularly the elderly, who are not so familiar with technology [4].

- Reliability and trust: There is the necessity of proving voice as a biomarker in future studies of the accuracy or prognosis assessment capability of these algorithms in diagnosing disease. A need to prove further value above existing technology exists [4].

- Lack of generalizability and reliability: ML models can often learn unwanted features from datasets, questioning generalizability and reliability. To reduce variability, it is best to use multi-study ML techniques [112].

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Medical care has evolved since the pandemic, with video or teleconsultations replacing many hospital visits. Digitization has become the greater focus. Medical devices have long been used to monitor physiological parameters such as blood pressure, oxygen saturation, blood glucose, and cardiac rhythms [31,113]. The human voice is another readily available and collectable physiological parameter containing rich diagnostic clues that could be used for predictive analytics. The notion of using voice as a mode of supplemental diagnosis or as a prognostic indicator is yet to be fully functional. Its noninvasive nature and reduced patient burden, along with the fast and high volume of data collection reducing the health system burden, supports the need to explore more of this domain [1,2,31].

The human voice is an index reflecting characteristics of the vocal cords produced from synchronous interactions of the anatomical, physiological, neurological, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems [2,20,46,114]. Therefore, any alterations in these systems alter certain parameters of the voice, which can be appreciated and analyzed. Artificial intelligence plays a key role in uplifting this approach, creating a new dawn in digital health [1,4,49]. The Fourth Industrial Revolution has presented innovative technologies including voice-powered technologies such as Google Assistant, Alexa, and Siri on smartphones as well as at home, allowing extensive use of voice-controlled search, called CAI. The advent of voice technology, artificial intelligence, and neural networks has opened a way to use voice as a biomarker, creating a potential digital health solution [1,4].

Algorithms already exist for voiceprint recognition to distinguish voiceprint features, although they are limited to legal use and by the FBI [20]. Expanding on this, voice as a biomarker has been studied in various domains, with more focus on neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, psychiatric conditions, mood disorders, and imminent suicide detection, expanding to pulmonary diseases with increased application in COVID-19 [4,115]. Novel applications have been studied in the identification and prognosis of diabetes, CHF, CAD, GERD, and endocrine disorders. Using phenomes such as vowels makes the vocal biomarker more sensitive due to its language-, accent-, age-, and culture-independent nature. Vocal parameters commonly assessed include the standard amplitude, pitch, pulse, and NSR as well as perturbation features: F0, shimmer, jitter, HNR, and others such as MPT and the S/Z ratio [16,26,27,116]. Glottal, temporal-spectral, and formant features can supplement acoustic findings [46].

Multiple ML and DL models have been studied across various aspects. In relation to PD, KNN showed the highest accuracy for PD male patients, and for female patients, SVM [7]. SVM was also found to have 88% prediction accuracy of fatigue for single vowels and 94% for multi-vowels [20]. OpenSMILE was utilized mainly in MDD studies, but these studies were performed on a small sample size [8,10]. A study performed to evaluate various ML models such as SVM, RF, XGBoost, GBM, adaBoost, Linear, Ridge, elasti net, and LASSO regression to monitor cognitive performance in trauma victims showed XGBoost outperformed the others [45]. A similar study to differentiate between minor and major depression revealed MLP exhibited the best performance (AUC 0.79 for mDE and 0.58 for MDD at 7:3 training set; at 8:2 training set, AUC 0.69 for mDE and 0.67 for MDD) [46]. Various ML models were studied in detecting voice changes in COVID-19 patients from HCs, and the results showed RF (accuracy 82%, sensitivity 94%, specificity 70.59%), Adaboost (accuracy 74%, sensitivity 71%, specificity 76.4%), SVM (accuracy 74%, sensitivity 94%, specificity 52.94%) [6]. XGBoost had higher sensitivity AUC in detecting post-stroke patients at high risk for aspiration [35]. Overall, SVM was found to be best among majority disease spectra for smaller datasets, but for larger datasets, DL models such as ANN and CNN were found to be superior [33,37]. It is to be noted that the ML and DL models have been studied for individual disease analysis. A future exploration would be to analyze a massive dataset of various diseases affecting various systems in the same recording environment using the same model and statistical analysis.

A major challenge with vocal biomarkers is the identifiable nature of voice, potentially violating HIPAA [1]. Encryption methods such as redaction, transformation, cloaking, and noise addition could overcome this [104,105,106,107,108]. The US FDA has not approved vocal biomarkers yet, mainly since this area is so new, and more data are needed. There is also a lack of standardized voice recording or processing methods [1,20]. Novel technological applications are relatively less readily accepted or trusted by people, and hence, they would require convincing evidence of superiority over existing health technologies [4]. There is a lack of generalizability and cross-platform transferability in existing studied models, creating a need for studies with larger cohorts and variable phenotypes [1,109]. Recording from smartphones reduced data accuracy compared with recording with a standardized microphone in a soundproof room with the microphone at a fixed distance [116,117]. Ultimately, a unified corpus collection standard and a large-scale library of clinically available voice samples would be needed. This, followed by algorithm optimization and updates and the incorporation of algorithms into user-friendly devices, should be developed.

Future Perspectives

Vocal biomarkers can be coupled with smartphone apps, chatbots, smart mirrors, cars, and vocal assistants to monitor symptom resolution, provide information on mental health and quality of life decline, and curate a personalized follow-up post-diagnosis [31,114]. In triage areas of the hospital, vocal screening could be employed [31]. In clinical settings, vocal analysis could be employed for supplementing diagnosis, stratification, and telemedicine/telemonitoring [1]. Vocal biomarkers could be incorporated with alert systems, improving patient safety. Integration with health calls or emergency centers would give real-time analysis of important health-related aspects, supplementing consultations [1,31]. This approach would help describe significant events occurring between two follow-up visits, bridging the existing gap [31].

The development of voice analytic devices as wearable technologies is an area to explore. Constantly improving technology, data-transfer capabilities, 5G networks, and increased usage of smartphones with voice assistants or at-home voice assistants will enable easy collection and processing of vocal data in high definition. It is imperative to adapt natural language processing in voice technologies to understand emotion and empathy in the voice if we are to consider long-term implementation [1]. With future studies incorporating reliable technology with artificial intelligence and larger cohorts of broader phenotypes, voice analysis is a promising digital health solution.

Author Contributions

P.M. and S.P.A. defined the review scope, context, and purpose of this study. P.M., B.B., H.S., K.G., D.S., P.C.P. and A.S. conducted the literature review and drafted the manuscript. S.P.A. and P.M. conceived and crafted the illustrative figures. D.M., S.S.H., V.N.I. and S.A.H. provided clinical perspectives and expertise for this study. All authors read and performed a critical review of the manuscript. P.M. and S.P.A. performed the cleaning and organization of the manuscript. S.P.A. provided conceptualization, supervision, and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This review was based on publicly available academic literature databases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by resources within the Digital Engineering and artificial Intelligence Laboratory (DEAL), Department of Critical Care Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Florida, Jacksonville, USA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fagherazzi, G.; Fischer, A.; Ismael, M.; Despotovic, V. Voice for Health: The Use of Vocal Biomarkers from Research to Clinical Practice. Digit. Biomark. 2021, 5, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stogowska, E.; Kamiński, K.A.; Ziółko, B.; Kowalska, I. Voice changes in reproductive disorders, thyroid disorders and diabetes: A review. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbéji, A.; Zhang, L.; Higa, E.; Fischer, A.; Despotovic, V.; Nazarov, P.V.; Aguayo, G.; Fagherazzi, G. Vocal biomarker predicts fatigue in people with COVID-19: Results from the prospective Predi-COVID cohort study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, J.K.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Utilizing Conversational Artificial Intelligence, Voice, and Phonocardiography Analytics in Heart Failure Care. Heart Fail. Clin. 2022, 18, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.M.; Özkanca, Y.; Atkins, D.C.; Hosseini Ghomi, R. Investigating voice as a biomarker: Deep phenotyping methods for early detection of Parkinson’s disease. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 104, 103362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, L.; De Pietro, G.; Sannino, G. Artificial Intelligence Techniques for the Non-invasive Detection of COVID-19 Through the Analysis of Voice Signals. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 11143–11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajal, M.S.R.; Ehsan, M.T.; Vaidyanathan, R.; Wang, S.; Aziz, T.; Mamun, K.A.A. Telemonitoring Parkinson’s disease using machine learning by combining tremor and voice analysis. Brain Inform. 2020, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Pan, W.; Hu, B.; Zhu, T. Acoustic differences between healthy and depressed people: A cross-situation study. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppa, A.; Costantini, G.; Asci, F.; Di Leo, P.; Al-Wardat, M.S.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Scalise, S.; Pisani, A.; Saggio, G. Voice in Parkinson’s Disease: A Machine Learning Study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 831428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, T.; Tachikawa, H.; Nemoto, K.; Suzuki, M.; Nagano, T.; Tachibana, R.; Nishimura, M.; Arai, T. Major depressive disorder discrimination using vocal acoustic features. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domeracka-Kołodziej, A.; Grabczak, E.M.; Dąbrowska, M.; Arcimowicz, M.; Lachowska, M.; Osuch-Wójcikiewicz, E.; Niemczyk, K. Comparison of voice quality in patients with GERD-related dysphonia or chronic cough. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2014, 68, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worasawate, D.; Asawaponwiput, W.; Yoshimura, N.; Intarapanich, A.; Surangsrirat, D. Classification of Parkinson’s disease from smartphone recording data using time-frequency analysis and convolutional neural network. Technol. Health Care 2023, 31, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafi, S.; Gangloff, C.; Paulhet, E.; Grimault, O.; Soulat, L.; Bouzillé, G.; Cuggia, M. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Detection by Machine Learning Based on the Phonetic Characteristics of the Caller’s Voice. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 294, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.Z.; Simonetti, A.; Brillantino, R.; Tayler, N.; Grainge, C.; Siribaddana, P.; Nouraei, S.A.R.; Batchelor, J.; Rahman, M.S.; Mancuzo, E.V.; et al. Predicting Pulmonary Function From the Analysis of Voice: A Machine Learning Approach. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 750226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, E.; Perry, D.; Mevorach, D.; Taiblum, N.; Luz, Y.; Mazin, I.; Lerman, A.; Koren, G.; Shalev, V. Vocal Biomarker Is Associated With Hospitalization and Mortality Among Heart Failure Patients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e013359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaslıkaya, S.; Geçkil, A.A.; Birişik, Z. Is There a Relationship between Voice Quality and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Severity and Cumulative Percentage of Time Spent at Saturations below Ninety Percent: Voice Analysis in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Medicina 2022, 58, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pah, N.D.; Indrawati, V.; Kumar, D.K. Voice Features of Sustained Phoneme as COVID-19 Biomarker. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2022, 10, 4901309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Nicolás, I.; Llorente, T.E.; Martínez-Sánchez, F.; Meilán, J.J.G. Speech biomarkers of risk factors for vascular dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1057578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, J.D.S.; Maor, E.; Borlaug, B.; Lewis, B.R.; Orbelo, D.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Non-invasive vocal biomarker is associated with pulmonary hypertension. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ma, K.; Yang, H.; Wang, K.; Fu, B.; Zhu, Y.; She, X.; Cui, B. A rapid, non-invasive method for fatigue detection based on voice information. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 994001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Mechanics of human voice production and control. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 140, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J. Myoelastic-aerodynamic theory of voice production. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1958, 1, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michon, M.; López, V.; Aboitiz, F. Origin and evolution of human speech: Emergence from a trimodal auditory, visual and vocal network. Prog. Brain Res. 2019, 250, 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J.; Tan, T.S. Results of experiments with human larynxes. Pract. Otorhinolaryngol. 1959, 21, 425–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proutskova, P.; Rhodes, C.; Crawford, T.; Wiggins, G. Breathy, Resonant, Pressed—Automatic Detection of Phonation Mode from Audio Recordings of Singing. J. New Music. Res. 2013, 42, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioRender.com. BioRender. Available online: https://biorender.com/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Mahon, E.; Lachman, M.E. Voice biomarkers as indicators of cognitive changes in middle and later adulthood. Neurobiol. Aging 2022, 119, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.P.; Oliveira, C.; Lopes, C. Vocal acoustic analysis—Jitter, shimmer and HNR parameters. Procedia Technol. 2013, 9, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, J.L.; Holbrook, A. Modal vocal fundamental frequency of young adults. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1970, 92, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P. Accurate short-term analysis of the fundamental frequency and the harmonic-to-noise ratio of a sample sound. IFA Proc. 1993, 17, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Asci, F.; Costantini, G.; Saggio, G.; Suppa, A. Fostering Voice Objective Analysis in Patients with Movement Disorders. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Elbeji, A.; Aguayo, G.; Fagherazzi, G. Recommendations for Successful Implementation of the Use of Vocal Biomarkers for Remote Monitoring of COVID-19 and Long COVID in Clinical Practice and Research. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2022, 11, e40655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higa, E.; Elbéji, A.; Zhang, L.; Fischer, A.; Aguayo, G.A.; Nazarov, P.V.; Fagherazzi, G. Discovery and Analytical Validation of a Vocal Biomarker to Monitor Anosmia and Ageusia in Patients With COVID-19: Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e35622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Yan, H.T.; Lin, C.H.; Chang, H.H. Predicting frailty in older adults using vocal biomarkers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.Y.; Park, D.; Kang, H.S.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Im, S. Post-stroke respiratory complications using machine learning with voice features from mobile devices. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 16682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryn, Y.; Corthals, P.; De Bodt, M.; Van Cauwenberge, P.; Deliyski, D. Perturbation Measures of Voice: A Comparative Study between Multi-Dimensional Voice Program and Praat. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2009, 61, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Dr, V.C.; Robotti, C.; Benazzo, M.; Pietrantonio, F.; Di Girolamo, S.; Pisani, A.; Canzi, P.; Mauramati, S.; Bertino, G.; et al. Deep learning and machine learning-based voice analysis for the detection of COVID-19: A proposal and comparison of architectures. Knowl. Based Syst. 2022, 253, 109539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Ren, K.; Luo, Z. A Deep Learning Based Method for Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Dynamic Features of Speech. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 10239–10252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Södersten, M.; Salomão, G.L.; McAllister, A.; Ternström, S. Natural Voice Use in Patients With Voice Disorders and Vocally Healthy Speakers Based on 2 Days Voice Accumulator Information From a Database. J Voice 2015, 29, 646.e1–646.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suppa, A.; Asci, F.; Saggio, G.; Marsili, L.; Casali, D.; Zarezadeh, Z.; Ruoppolo, G.; Berardelli, A.; Costantini, G. Voice analysis in adductor spasmodic dysphonia: Objective diagnosis and response to botulinum toxin. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 73, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppa, A.; Asci, F.; Saggio, G.; Di Leo, P.; Zarezadeh, Z.; Ferrazzano, G.; Ruoppolo, G.; Berardelli, A.; Costantini, G. Voice Analysis with Machine Learning: One Step Closer to an Objective Diagnosis of Essential Tremor. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, A.; Claria, F.; Solsona, F.; Meister, E.; Povedano, M. Detection of Bulbar Involvement in Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis by Machine Learning Voice Analysis: Diagnostic Decision Support Development Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e21331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrón, J.; Campos-Roca, Y.; Madruga, M.; Pérez, C.J. A mobile-assisted voice condition analysis system for Parkinson’s disease: Assessment of usability conditions. BioMed. Eng. Online 2021, 20, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hireš, M.; Gazda, M.; Drotár, P.; Pah, N.D.; Motin, M.A.; Kumar, D.K. Convolutional neural network ensemble for Parkinson’s disease detection from voice recordings. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 141, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultebraucks, K.; Yadav, V.; Galatzer-Levy, I.R. Utilization of Machine Learning-Based Computer Vision and Voice Analysis to Derive Digital Biomarkers of Cognitive Functioning in Trauma Survivors. Digit. Biomark. 2020, 5, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.; Cho, W.I.; Park, C.H.K.; Rhee, S.J.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, H.; Kim, N.S.; Ahn, Y.M. Detection of Minor and Major Depression through Voice as a Biomarker Using Machine Learning. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Suh, S.W.; Kim, T.; Kim, K.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, J.R.; Han, G.; Hong, J.W.; Han, J.W.; Lee, K.; et al. Screening major depressive disorder using vocal acoustic features in the elderly by sex. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 291, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.; Nedeljkovic, M.; Meyer, D. Using Voice Biomarkers to Classify Suicide Risk in Adult Telehealth Callers: Retrospective Observational Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e39807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, E.; Tsur, N.; Barkai, G.; Meister, I.; Makmel, S.; Friedman, E.; Aronovich, D.; Mevorach, D.; Lerman, A.; Zimlichman, E.; et al. Noninvasive Vocal Biomarker is Associated With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2021, 5, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, M.L.; Cavallaro, G.; Di Nicola, V.; Quaranta, N. Voice Differences When Wearing and Not Wearing a Surgical Mask. J. Voice 2023, 37, e1–e467.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, E.; Sara, J.D.; Orbelo, D.M.; Lerman, L.O.; Levanon, Y.; Lerman, A. Voice Signal Characteristics Are Independently Associated With Coronary Artery Disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, D.A.M.; Jiménez, V.M.V.; López, X.H.; Ysunza, P.A. Acoustic Analysis of Voice and Electroglottography in Patients With Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. J. Voice 2018, 32, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruas, A.C.; Lucena, M.M.; da Costa, A.D.; Vieira, J.R.; de Araújo-Melo, M.H.; Terceiro, B.R.; de Sousa Torraca, T.S.; de Oliveira Schubach, A.; Valete-Rosalino, C.M. Voice disorders in mucosal leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, N.B.; Regmi, D.; Bista, M.; Sherpa, P. Acoustic Analysis of Voice in School Teachers. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2018, 56, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinyopodjanard, S.; Suppakitjanusant, P.; Lomprew, P.; Kasemkosin, N.; Chailurkit, L.; Ongphiphadhanakul, B. Instrumental Acoustic Voice Characteristics in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Voice 2021, 35, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gölaç, H.; Atalik, G.; Türkcan, A.K.; Yilmaz, M. Disease related changes in vocal parameters of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2022, 47, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.M.; Sharma, Y. Voice parameter analysis for the disease detection. IOSR J. Electron. Commun. Eng. 2014, 9, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talk About a Revolution: The Future of Voice Biomarkers in the Neurology Clinic. University of Washington. Available online: http://depts.washington.edu/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Nichols, E.; Abbasi, N.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Adsuar, J.C.; Ansha, M.G.; Brayne, C.; Choi, J.Y.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Lau, K.K.; Thyagarajan, D. Voice changes in Parkinson’s disease: What are they telling us? J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 72, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.J.; Oates, J.M.; Phyland, D.J.; Hughes, A.J. Voice characteristics in the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2000, 35, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, B.; Cannizzaro, M.; Snyder, P.J. Variability in fundamental frequency during speech in prodromal and incipient Parkinson’s disease: A longitudinal case study. Brain Cogn. 2004, 56, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroge, T.J.; Özkanca, Y.; Demiroglu, C.; Si, D.; Atkins, D.C.; Ghomi, R.H. Parkinson’s disease diagnosis using machine learning and voice. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Signal Processing in Medicine and Biology Symposium (SPMB), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Benba, A.; Jilbab, A.; Hammouch, A. Voice assessments for detecting patients with Parkinson’s diseases using PCA and NPCA. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2016, 19, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakar, B.E.; Isenkul, M.E.; Sakar, C.O.; Sertbas, A.; Gurgen, F.; Delil, S.; Apaydin, H.; Kursun, O. Collection and Analysis of a Parkinson Speech Dataset With Multiple Types of Sound Recordings. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2013, 17, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimers Disease Facts and Figures: 10 Million US Baby Boomers will Develop Alzheimer’s Disease; Alzheimer’s Association: San Jose, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Porsteinsson, A.P.; Isaacson, R.S.; Knox, S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Rubino, I. Diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical practice in 2021. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 8, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilan, J.J.G.; Martinez-Sanchez, F.; Carro, J.; Carcavilla, N.; Ivanova, O. Voice Markers of Lexical Access in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2018, 15, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavitha, C.; Mani, V.; Srividhya, S.R.; Khalaf, O.I.; Tavera Romero, C.A. Early-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning Models. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 853294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, K.; Chen, A.L.; Braverman, E.R.; Comings, D.E.; Chen, T.J.; Arcuri, V.; Blum, S.H.; Downs, B.W.; Waite, R.L.; Notaro, A.; et al. Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and reward deficiency syndrome. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 893–918. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman, J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A selective overview. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Real, T.; Diaz-Roman, T.M.; Garcia-Martinez, V.; Vieiro-Iglesias, P. Clinical and acoustic vocal profile in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Voice 2013, 27, 787.e11–787.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, H.W.; Ooi, C.P.; Barua, P.D.; Palmer, E.E.; Molinari, F.; Acharya, U. Automated detection of ADHD: Current trends and future perspective. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 16, 105525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Polier, G.G.; Ahlers, E.; Amunts, J.; Langner, J.; Patil, K.R.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Helmhold, F.; Langner, D. Predicting adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) using vocal acoustic features. medRxiv 2021, 24, 2021–2103. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchack, K.E. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Updated Guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 629–631. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneh, Y.S.; Levanon, Y.; Dean-Pardo, O.; Lossos, L.; Adini, Y. Abnormal speech spectrum and increased pitch variability in young autistic children. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 4, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusaroli, R.; Lambrechts, A.; Bang, D.; Bowler, D.M.; Gaigg, S.B. Is voice a marker for Autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari, M.; Chen, L.; Fombonne, E. Quantifying voice characteristics for detecting autism. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 665096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, D.; Shoeibi, A.; Ghassemi, N.; Moridian, P.; Khadem, A.; Alizadehsani, R.; Teshnehlab, M.; Gorriz, J.M.; Khozeimeh, F.; Zhang, Y.D.; et al. An overview of artificial intelligence techniques for diagnosis of Schizophrenia based on magnetic resonance imaging modalities: Methods, challenges, and future works. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Yang, J. Dynamic thresholding networks for schizophrenia diagnosis. Artif. Intell. Med. 2019, 96, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, M.; Hwang, H.J.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, S.H.; Im, C.H. Machine-learning-based diagnosis of schizophrenia using combined sensor-level and source-level EEG features. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 176, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parola, A.; Simonsen, A.; Bliksted, V.; Fusaroli, R. Voice patterns in schizophrenia: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 216, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, M.T.; Lunden, A.; Cleary, S.D.; Pauselli, L.; Alolayan, Y.; Halpern, B.; Broussard, B.; Crisafio, A.; Capulong, L.; Balducci, P.M.; et al. The aprosody of schizophrenia: Computationally derived acoustic phonetic underpinnings of monotone speech. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 197, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Ekuni, D.; Higuchi, M.; Takayama, E.; Tokuno, S.; Morita, M. Relationship between Psychological Stress Determined by Voice Analysis and Periodontal Status: A Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdas, A.; Shiavi, R.G.; Silverman, S.E.; Silverman, M.K.; Wilkes, D.M. Investigation of vocal jitter and glottal flow spectrum as possible cues for depression and near-term suicidal risk. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 51, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.-S.A.; Maddage, N.C.; Lech, M.; Sheeber, L.B.; Allen, N.B. Detection of Clinical Depression in Adolescents’ Speech During Family Interactions. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 58, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, D.J.; Shiavi, R.G.; Silverman, S.; Silverman, M.; Wilkes, M. Acoustical properties of speech as indicators of depression and suicidal risk. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 47, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadina, A.O.; Salah, A.M.; Jalal, K. (Eds.) Voice Analysis Framework for Asthma-COVID-19 Early Diagnosis and Prediction: AI-based Mobile Cloud Computing Application. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ElConRus), St. Petersburg, Russia; Moscow, Russia, 26–29 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.; Kausthubha, N.K.; Gope, D.; Krishnaswamy, U.M.; Ghosh, P.K. (Eds.) Comparison of cough, wheeze and sustained phonations for automatic classification between healthy subjects and asthmatic patients. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 July 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Song, P.; Adeloye, D.; Salim, H.; Dos Santos, J.P.; Campbell, H.; Sheikh, A.; Rudan, I. Global, regional, and national prevalence of asthma in 2019: A systematic analysis and modelling study. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 04052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sm, U.S.; Katiravan, J. Mobile application based speech and voice analysis for COVID-19 detection using computational audit techniques. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2022, 18, 508–517. [Google Scholar]

- Pecere, S.; Milluzzo, S.M.; Esposito, G.; Dilaghi, E.; Telese, A.; Eusebi, L.H. Applications of Artificial Intelligence for the Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Diseases. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayazi, S.; Pearson, J.; Hashemi, M. Gastroesophageal reflux and voice changes: Objective assessment of voice quality and impact of antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 46, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]