Abstract

This systematic review documents the protocol characteristics of studies that used neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocols (NMES) on the plantar flexors [through triceps surae (TS) or tibial nerve (TN) stimulation] to stimulate afferent pathways. The review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement, was registered to PROSPERO (ID: CRD42022345194) and was funded by the Greek General Secretariat for Research and Technology (ERA-NET NEURON JTC 2020). Included were original research articles on healthy adults, with NMES interventions applied on TN or TS or both. Four databases (Cochrane Library, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) were systematically searched, in addition to a manual search using the citations of included studies. Quality assessment was conducted on 32 eligible studies by estimating the risk of bias with the checklist of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool. Eighty-seven protocols were analyzed, with descriptive statistics. Compared to TS, TN stimulation has been reported in a wider range of frequencies (5–100, vs. 20–200 Hz) and normalization methods for the contraction intensity. The pulse duration ranged from 0.2 to 1 ms for both TS and TN protocols. It is concluded that with increasing popularity of NMES protocols in intervention and rehabilitation, future studies may use a wider range of stimulation attributes, to stimulate motor neurons via afferent pathways, but, on the other hand, additional studies may explore new protocols, targeting for more optimal effectiveness. Furthermore, future studies should consider methodological issues, such as stimulation efficacy (e.g., positioning over the motor point) and reporting of level of discomfort during the application of NMES protocols to reduce the inherent variability of the results.

1. Introduction

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is a technique that involves involuntary muscle activation via flow of electrical current, and is commonly used to enhance and/or restore neuromuscular function [1]. More often, the electrical stimulation is delivered over the muscle, recruiting mainly the motor units underneath the surface of the electrodes [2] in a non-physiological order, i.e., synchronously and spatially fixed. In an effort to mimic the motor unit recruitment order observed during a voluntary contraction [3], further NMES protocols have been developed to activate synaptically motoneurons by stimulating afferents fibers from muscle spindles [4], and thereby recruiting from small to large motoneurons [5]. These protocols have special stimulation attributes, which have been explored with various study designs in order to document the effectiveness on stimulating afferent pathways with NMES.

Conventional NMES consists of short duration trains of pulses (50–400 μs) over the muscle belly and targets mainly the efferent pathway, by stimulating the motor axons beneath the stimulation electrodes [2]. On the other hand, NMES delivered over the muscle belly or nerve trunk with a wide-pulse duration (≥0.5 ms) [6,7], high frequency (≥80 Hz) and low stimulation intensity is referred as Wide Pulse High Frequency NMES (WPHF), and has the potential to preferentially activate motor neurons via spinal pathways [8,9,10]. This is because WPHF depolarize more effectively sensory than motor axons, as sensory axons have greater diameter, longer strength-duration time constant (chronaxie) and lower rheobase than motor axons [9,11].

Muscle and nerve stimulation that involve sensory pathways may potentiate spinal excitability and reinforce activity-dependent plasticity in neural circuits, especially when WPHF is combined with voluntary contractions [5,12]. Besides neural adaptations at spinal level, WPHF NMES may also lead to some supraspinal adaptations [13], which could be important for basic functional tasks, such as gait and balance, and further raise the interest in the investigation of NMES protocols on the lower limbs [14]. For instance, WPHF NMES-induced afferent volleys may activate motor and sensory cortical areas of the brain, as proved with functional magnetic resonance scans [15]. On the other hand, there are studies that failed to observe neuromuscular adaptations after intervention with WPHF, and dictate the necessity to standardize and optimize the stimulation properties, such as frequency, pulse duration and intensity [16].

The extensive use of NMES has consequently resulted in a wide range of protocols. By the strict definition of WPHF there is no distinction in the stimulation characteristics when stimulating over the muscle belly or the nerve trunk. Nevertheless, there are NMES protocols with shorter pulse width and lower stimulation frequencies that demonstrated similar effectiveness stimulating the afferent pathway, as typical WPHF protocols do (e.g., 11,15), but this issue is not well documented. This could be important for NMES protocols applied over nerves since the discomfort level increases with higher stimulation frequency and pulse duration. Examining the afferent pathway with nerve and muscle NMES may improve our picture about neuromuscular functions, because the stimulation site may involve neural or muscular mechanisms to a different extent [7,17,18,19,20]. For instance, nerve WPHF protocols generate fatigue patterns similar to voluntary contractions for the same force output [21]. However, later studies suggest that WPHF over the muscle or nerve trunk can generate similar adaptations, at least regarding the force development [7].

Considering the functional importance of the plantar flexor muscles during gait and balance, and the contribution of afferent pathways to sensory-motor integration during these tasks [22,23,24], documentation of the diversity of NMES protocols that stimulate the afferent pathway could be the first step to define the relevance of stimulation properties relative to the objective of NMES applications. Therefore, this review aims to document and describe the attributes of NMES protocols that give evidence of stimulating the motor neurons synaptically, via afferent pathways and have been applied on the triceps surae muscle (TS) or the tibial nerve (TN), in healthy adults. Knowing which are the NMES characteristics that are currently used to investigate underlying mechanisms of neuromuscular functions, can give insights into how NMES could be applied in the future.

2. Methods

The structure of this review was designed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [25].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The selected studies in this review were cohort, cohort analytic or randomized controlled trial studies that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) original research articles, (2) including interventions with NMES applied on TN or TS or both (3) of healthy adults. Studies with at least one WPHF protocol were included. WPHF protocols were protocols with stimulation frequency greater or equal to 80 Hz, rectangular pulse, and pulse duration greater or equal than 0.5 ms [8,26]. Any other protocol that had the same effect on the main outcome variable as the WPHF protocol was included for analysis as well. No other criterion was set, to allow a more comprehensive overview of this nascent field.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The development of our search strategy was based on guidance from previous relevant papers [27,28]. A systematic search was conducted in The Cochrane Library, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception to 26 July 2022. Additionally, the citations from the included studies were searched for additional studies. The complete search strategy is presented in Appendix S1 (Supplementary Material).

2.3. Study Collection and Selection Process

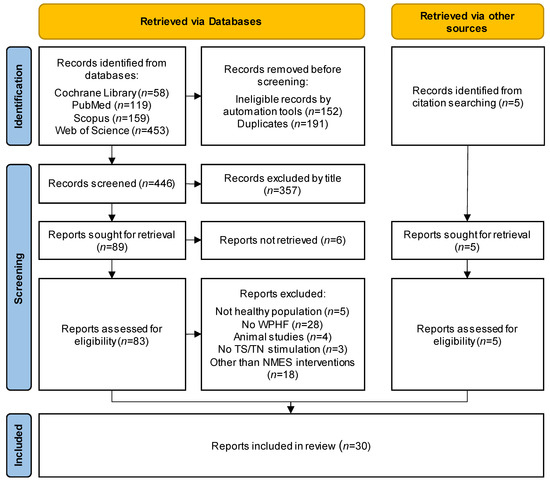

The collection and selection process of this review is presented in detail in Figure 1. A total number of 796 records were identified from four databases. After filtering online each database for language (English), type of publication (article, final report), and studies on humans, 151 studies were excluded and the remaining 645 were saved in a spreadsheet. All records, with title and abstract, were screened and 191 duplicate entries were removed. The titles of the remaining studies (n = 448) were identified as “not relevant” or “potentially relevant” by two reviewers (AP, TT), using a semi-automated process, with specific keywords search, to exclude animal studies (e.g., mice, cats), studies with not healthy population (e.g., multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy) while keeping in consideration all inclusion and exclusion criteria. The potentially relevant studies (n = 91) sought for retrieval and 85 abstracts were retrieved. All abstracts were screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers (AP, AX) and the reasoning for exclusion was recorded. After this process, the reviewers compared their results and decided which articles should finally be included in the review. Five additional records were identified through citation sources from the retrieved records. All discrepancies in decisions between the reviewers were resolved through consensus. A third author (DM) acted as an arbiter when needed. After the final inclusion (n = 32), two authors (AP, AX) processed independently the full-text articles to extract all data items.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process via databases and other sources, according to PRISMA 2020 for new systematic reviews.

2.4. Data Extraction Process

The data items that were extracted from the manuscripts were the characteristics of the participants (number of participants and dropouts, gender, age), stimulation type (muscle or nerve) and NMES attributes (pulse width, frequency, duration, intensity). The number of dropouts due to pain was recorded, if reported. Discomfort rate was expressed as the percentage of dropout cases due to discomfort from the initial number of participants of each study. The extracted data of the two reviewers were compared to confirm their accuracy and full agreement was achieved.

2.5. Quality Assessment

Two reviewers assessed independently the risk of bias of the included studies (AP, AX) using the checklist of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP). Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third author acting as an arbiter (TT), when necessary.

2.6. Data Synthesis

For the data synthesis, protocol attributes were extracted from the studies and were summarized for each of the stimulation types (TS and TN). The scope of each study was presented narratively, and each study was classified into 4 major categories depending on the field of interest when using WPHF. Mechanisms: when studies aimed at elucidating neuromuscular mechanisms associated with WPHF. Extra forces: when WPHF was applied to generate additional force through central pathways. Fatigue: when WPHF was used as a tool to investigate muscle fatigue. Training: when WPHF was used as an intervention method. The outcome variables from the studies such as number of participants, gender, age, dropouts, pulse width, frequency patterns, duration, and intensity were extracted and categorized in custom ranges. Outcome measures were expressed as a percentage of the total number of protocols on each type of NMES.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

Thirty-two studies met the rigid inclusion criteria of this review and were included in the final analysis. Nineteen studies involved NMES on the TS, 10 on the TN and 3 on both. Regarding the study design, 6 were randomized controlled trials [16,29,30,31,32,33], two were cohort analysis studies [34,35] and 24 were cohort studies [5,7,8,11,12,13,15,17,18,20,21,26,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Concerning the research field of application of the WPHF protocols, 12 studies involved “extra force” [5,7,13,18,20,31,33,34,37,41,45,47], 9 “mechanisms” [8,11,12,15,17,35,36,38,40], 7 “fatigue” [21,26,39,42,43,44,46], and 4 “training” [16,29,30,32]. All studies were published between 2002 and 2021 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics, scope, and main conclusions of all included studies with WPHF NMES on the triceps surae (TS), tibial nerve (TN), or both.

3.2. Risk of Bias within Studies

According to the EPHPP checklist of risk bias, the results of the quality assessment (Supplementary Material, Appendix S2) showed 93.8% agreement between the reviewers. The score was moderate for 2 studies [5,41] and strong for the rest of the 32 studies, resulting in a low-bias risk quality of the studies included in the current review.

3.3. Participants

In total, 462 adults with 122 females (26.4%) were included in 32 studies. The mean age of the participants, adjusted for the number of participants in each study was 31.8 years. 309 participants received NMES on the TS (mean n = 16.3/study), and 115 on the TN (mean n = 11.5/study) and 39 on both TS and TN (mean n = 13.0/study). In 9 studies 22 dropouts out of 109 participants in total were reported (18.3% dropout rate). The dropout cases were 4 for studies including TS protocols, 13 for TN protocols and 5 for both. The most common reported reason for dropout was pain, with 12 cases (54.5%). 10 of these cases involved protocols with TN and 2 protocols with TS and TN.

3.4. Protocols

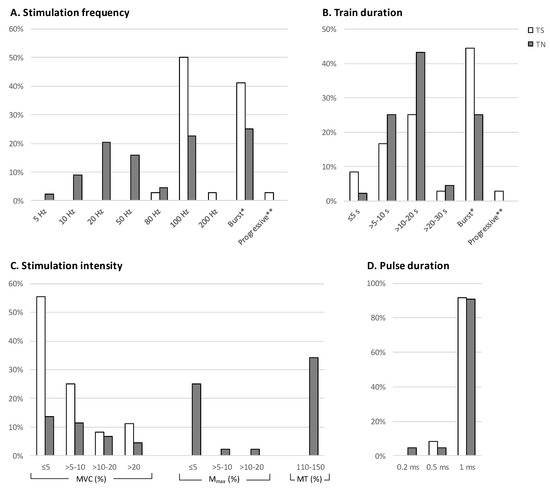

Most of the studies incorporated multiple protocols, resulting in total 87 NMES protocols, among which 43 were applied on the TS and 44 on the TN. All analyzed NMES parameters of these protocols are shown in Table 2. Figure 2 shows the distribution of each of the stimulus parameter expressed as a percentage of total TS or TN protocols.

Table 2.

NMES protocols and stimulation parameters (pulse width, frequency, duration, and intensity).

Figure 2.

Incidence of stimulation frequency (A), train duration (B), stimulation intensity (C) and pulse duration (D) expressed as percentage of total number of WPHF protocols applied on the triceps surae (TS) and tibial nerve (TN). * Burst represents protocols with variable frequency comprised of one WPHF burst (80–100 Hz) between stimulation trains of lower frequency (20–30 Hz). ** Progressive represents one protocol with variable stimulation frequency ramping up from 4 to 100 Hz and ramping down to 4 Hz. Stimulation intensity (C) has been adjusted based on the produced force [expressed as a percentage of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC)] or the M-wave [expressed as percentage of maximum M-wave (Mmax)], or a percentage of the motor threshold (MT).

3.5. Stimulation Frequency

Regarding the stimulation frequency (Figure 2A), 3 patterns of stimulation frequencies were identified: (a) the constant frequency pattern, with a continuous stimulation frequency, (b) the burst pattern, with a variable stimulation frequency following a low/high/low frequency scheme, and (c) the progressive pattern with a gradually increasing and decreasing frequency (ramp) profile. For the constant frequency, 26 protocols with frequencies ranging from 20 to 200 Hz were found for TS, and 33 protocols with frequencies ranging from 5 to 100 Hz were counted for TN. The burst pattern protocols were 16 for the TS, with 4 different modes (20/80/20, 20/100/20, 25/100/25 and 100/30) and 11 for the TN, with one mode (20/100/20). One progressive protocol was reported for TS, with a linearly increasing frequency from 4 to 100 Hz and decreasing from 100 to 4 Hz within 6 s. No progressing stimulation protocol was reported for TN.

3.6. Train Duration

For the constant frequency protocols, the start and end of stimulation expressed the duration of the (single) train. In both TS and TN, the most common duration was >10–20 s (14 for TS and 19 for TN), followed by the >5–10 s (6 for TS and 11 for TN, Figure 2B). For the burst protocols the duration of the burst ranged from 0.25 to 16 s, whereas the duration of the stimulation before and after the burst ranged from 2 to 3 s.

3.7. Stimulation Intensity

The current intensity of the stimulus was reported in 19 of the 32 studies in terms of mA (8 as range and 11 as mean ± standard deviation). For all protocols intensity was reported as the percentage of produced force relative to the maximal voluntary contraction (41 for TS and 16 for TN, with values ranging from 2 to 40% of MVC) or the recorded M-wave expressed as percentage of the maximum M-wave (Mmax; none for TS and 13 for TN, with values ranging from 0.3 to 20%) or as a percentage of the motor threshold (MT; none for TS and 15 for TN, with values ranging from below MT to 1.5 times MT). In one study the intensity of the TS protocol was adjusted to each subject’s tolerance level [32], and in one study with TN protocol, the intensity was variable, and progressively adjusted to maintain 20% of MVC [21].

3.8. Pulse Width

The majority of TS and TN protocols had 1 ms pulse width (38 and 40, respectively; Figure 2D). Three TS and 2 TN protocols had 0.5 ms pulse width. Furthermore, 2 TS [15,32] and 2 TN protocols [11] had shorter than 0.5 ms pulse duration.

4. Discussion

Eighty-seven protocols targeting the afferent pathway were identified and retrieved from 32 studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria of this review. The number of studies was greater for the TS than TN, but a greater number of protocols with greater diversity in their characteristics was observed in TN. It was found that TN had a wider range of stimulation frequencies and methods to define the intensity of the stimulation. Furthermore, pain could be a limiting factor for the application of TN stimulation, with similar characteristics as in TS.

Regarding the pulse width, the most frequently used duration was 1 ms, whereas the pulse width of 0.5 ms or lower was used in fewer protocols for both stimulation types. The stimulation site (TS or TN) seems to have no influence on the force levels when 1 ms pulse width is used at 100 Hz [7]. Furthermore, although wider pulses of stimulation (i.e., 1 ms) seem to be less metabolically demanding than short-pulse NMES [47], and are used to stimulate more preferably the afferent pathway [8,9,10], there is evidence for TS that NMES with briefer pulse width (0.26 or 0.5 ms) may induce similar functional benefits (performance in mobility tests) after NMES training [32] or similar torque decline (volitional and electrically-induced) after an NMES fatigue protocol [44]. There are also indications that short (0.2 ms) or wide (1 ms) pulse width induce a similar afferent output over the contralateral upper limb when stimulating the biceps brachii at 10% of MVC [48]. Furthermore, twitch torque potentiation was the same between short or wide pulse stimulation [45]. Therefore, short and wide pulse durations might have similar functional effects during muscle stimulation. It has to be noted though that at higher stimulation intensities, even with wide-pulse NMES, the antidromic efferent volley may cancel out the reflexively-induced muscle activation [8].

For the TS protocols, the most prominent frequency was the constant-frequency of 100 Hz with fewer counts at other frequencies. For TN, 100 Hz was again the most prominent frequency but more protocols than TS had frequencies between 5 and 80 Hz. There is evidence that corticospinal excitability is affected after NMES training using low (20 Hz) or high (100 Hz) stimulation frequencies, whereas spinal excitability was only changed after high-frequency NMES [30]. This is in line with experiments examining extra force using NMES protocols with different stimulation frequencies, showing that reflex excitability decreased after NMES at 20 Hz, did not change at 50 Hz and increased at 100 Hz [13]. Therefore, it seems that the stimulation frequency, at least for the TN, influences the nature of spinal adaptations. However, further work using similar stimulation protocol is needed to provide a clear conclusion on this aspect.

In the cases of high frequency stimulation bursts, the most common condition was 20/100/20 Hz for both TS and TN. Minor variations of using 25 Hz instead of 20 Hz before and after the burst have assumably negligible effects, although no studies have examined explicitly such comparisons. In contrast to constant frequency, burst stimulation occurs when the motor axons are already active, and this activation is enhanced after the burst (extra force), due to both muscular [43] and neural contributors [18]. It is worth noting however, that a 2-s burst at 100 Hz can augment the central contribution at similar level, independent of the stimulation site [17]. Therefore, repetitive short bursts which can be better tolerated than continuous nerve stimulation, could be a useful alternative to examine and restore spinal and supraspinal functions.

Regarding the intensity of stimulation all TS protocols used a force level using MVC as a reference point, whereas TN protocols used in addition to this, the amplitude of Mmax and motor threshold as well. The vast majority of protocols, both for TS and TN, induced stimulation currents that produced up to 10% of MVC. TN protocols with intensities set up to 5% of Mmax or 1.1–1.5 times above the motor threshold correspond within this MVC range (i.e., ~10%; 38). However, since electromyogram, required for measuring Mmax, is not necessarily measured in studies with TS, it could be suggested to report in future studies with TN the produced force expressed as percentage of MVC, in order to have a common ground regarding the intensities used in protocols with TS. Additionally, studies that reported intensities above 10% of MVC aimed to investigate more functionally relevant contractions, imitating produced torques at ranges required during walking or standing [17]. Besides, low level of initial force might minimize antidromic collision on motor axons and facilitate the potential input from the spinal cord to the muscles [35,37]. This is also in line with the fact that contractions at low levels of MVC may enable the development of extra force, which is a useful tool to investigate central and peripheral contributions [8].

It is important to mention that in the current review discomfort was reported as a cause of dropout only in studies with TN or with both TN and TS protocols. In the study of Neyroud et al. [7], the current intensity required to induce force at 5% of MVC, as well as the discomfort level, was lower in TS compared with TN. Hence, it could be argued that higher MVC levels could result in more discomfort during TN stimulation and could explain the reduced number of protocols above 10% of MVC. It is characteristic that in the study of Martin et al. [26] intensity was set to result in a force at 20% of MVC and discomfort rate was the greatest among all included studies. Consequently, the rising question is whether TS NMES has similar effects compared to TN NMES. From the three studies that compared the two approaches, Neyroud et al. [7] reported that extra forces have similar magnitude independent of the stimulation site, whereas Baldwin et al. [18] demonstrated greater extra forces when the muscle was stimulated. On the other hand, it seems that muscle and nerve stimulation involve different pathways [18] and that TN NMES may have the potential to involve more sensory pathways than TS [17]. It is also worth noting that according to findings of the analyzed articles, the involvement of the sensory pathway might be facilitated in the presence of voluntary contraction [35], depressed by transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [31], and depressed by antagonist muscle contraction [37]. These latter results raise the opportunity to develop strategies that may amplify or depress the central contribution to force production during NMES, depending on the objective of the treatment.

Finally, among the included studies there might be several methodological sources of variability that could influence the outcome variables or even the final conclusions. None of the studies reported whether their participants were restricted from strenuous activity or alcohol/coffee consumption prior to testing. Furthermore, different size of stimulating electrodes between studies and variations in electrode positioning might be another source of variability in the effectiveness of NMES. It is worth noting that electrodes of variable length (presumably adapted to the participants’ size) have been used in only one study [5]. Regarding the position of the electrodes, all studies used fixed measures from anatomical reference points. However, electrode placement over the motor point may increase the efficiency of NMES, with minimal injected current and less discomfort [49]. Since this might vary between subjects [50], motor point detection for each individual is recommended prior electrode placement. All these should be considered in future studies for more reproducible and robust results that can elucidate the physiological mechanisms underlying NMES.

5. Conclusions

This review describes the properties of protocols that applied TS and TN stimulation, targeting to the involvement of the central nervous system through afferent pathways. After analyzing 32 studies and 87 protocols the most common practice to assess the afferent pathway with NMES on TS or TN is with 100 Hz frequency, 1 ms pulse duration, and stimulation intensity at 10% of MVC. However, lower frequencies and pulse widths may also be effective and should be considered, especially in cases that discomfort due to the stimulation is an issue. This variety of NMES protocols that can induce activation a muscle via spinal pathways, dictates the need for further research to pinout the potential differences between different protocols and to create tailored protocols depending on the application and the goal of the research question, with the ultimate goal to optimize their effectiveness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/s23042347/s1. References [7,5,8,11,12,13,15,16,17,18,20,21,26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conception of the work: A.P. and D.A.P.; screening process and data analysis: A.P., A.X., D.M. and T.T.; drafted manuscript: A.P. and A.X.; made important intellectual contribution during revision with critical suggestions and comments: S.B., I.G.A. and T.L.; supervision and coordination: D.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Greek General Secretariat for Research and Technology (ERA-NET NEURON JTC 2020, T12EPA5-00018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vanderthommen, M.; Duchateau, J. Electrical stimulation as a modality to improve performance of the neuromuscular system. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2007, 35, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffiuletti, N.A. Physiological and methodological considerations for the use of neuromuscular electrical stimulation. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henneman, E.; Somjen, G.; Carpenter, D.O. Excitability and inhibitability of motoneurons of different sizes. J. Neurophysiol. 1965, 28, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, C.M.; Bickel, C.S. Recruitment patterns in human skeletal muscle during electrical stimulation. Phys. Ther. 2005, 85, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.F.; Burke, D.; Gandevia, S.C. Sustained contractions produced by plateau-like behaviour in human motoneurones. J. Physiol. 2002, 538, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, E.; Sjöholm, H.; Jäderholm-Ek, I.; Krynicki, J. Evaluation of methods for electrical stimulation of human skeletal muscle in situ. Pflüg. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1983, 398, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyroud, D.; Grosprêtre, S.; Gondin, J.; Kayser, B.; Place, N. Test-retest reliability of wide-pulse high-frequency neuromuscular electrical stimulation evoked force. Muscle Nerve 2018, 57, E70–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.C.; Yates, L.M.; Collins, D.F. Turning on the central contribution to contractions evoked by neuromuscular electrical stimulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 103, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.F. Central Contributions to Contractions Evoked by Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 9, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, M.C.; Lin, C.S.Y.; Burke, D. Differences in activity-dependent hyperpolarization in human sensory and motor axons. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerquist, O.; Collins, D.F. Influence of stimulus pulse width on M-waves, H-reflexes, and torque during tetanic low-intensity neuromuscular stimulation. Muscle Nerve 2010, 42, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerquist, O.; Mang, C.S.; Collins, D.F. Changes in spinal but not cortical excitability following combined electrical stimulation of the tibial nerve and voluntary plantar-flexion. Exp. Brain Res. 2012, 222, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitry, F.; Martin, A.; Deley, G.; Papaiordanidou, M. Effect of reflexive activation of motor units on torque development during electrically-evoked contractions of the triceps surae muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeard, A.; Bigot, L.; Chastan, N.; Gauthier, A. Does neuromuscular electrical stimulation training of the lower limb have functional effects on the elderly?: A systematic review. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 91, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyk, J.; Ranjeva, J.P.; Fouré, A.; Kavounoudias, A.; Vilmen, C.; Mattei, J.P.; Guye, M.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Place, N.; Bendahan, D.; et al. Specific brain activation patterns associated with two neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocols. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyroud, D.; Gonzalez, M.; Mueller, S.; Agostino, D.; Grosprêtre, S.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Kayser, B.; Place, N. Neuromuscular adaptations to wide-pulse high-frequency neuromuscular electrical stimulation training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, A.J.; Clair, J.M.; Collins, D.F. Motor unit recruitment when neuromuscular electrical stimulation is applied over a nerve trunk compared with a muscle belly: Triceps surae. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 110, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, E.R.L.; Klakowicz, P.M.; Collins, D.F. Wide-pulse-width, high-frequency neuromuscular stimulation: Implications for functional electrical stimulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Lloyd, R.S.; Myer, G.D. Youth resistance training: Past practices, new perspectives, and future directions. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2013, 25, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klakowicz, P.M.; Baldwin, E.R.L.; Collins, D.F. Contribution of M-waves and H-reflexes to contractions evoked by tetanic nerve stimulation in humans. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 96, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doix, A.C.M.; Matkowski, B.; Martin, A.; Roeleveld, K.; Colson, S.S. Effect of neuromuscular electrical stimulation intensity over the tibial nerve trunk on triceps surae muscle fatigue. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.S.; Zhou, S. Soleus H-reflex and its relation to static postural control. Gait Posture 2011, 33, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanenko, Y.P.; Gurfinkel, V.S. Human postural control. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterka, R.J. Sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 88, 1097–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.; Grosprêtre, S.; Vilmen, C.; Guye, M.; Mattei, J.P.; Le Fur, Y.; Bendahan, D.; Gondin, J. The etiology of muscle fatigue differs between two electrical stimulation protocols. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Riitano, D. Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargon, E.; Williamson, P.R.; Clarke, M. Collating the knowledge base for core outcome set development: Developing and appraising the search strategy for a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguetoch, A.; Martin, A.; Grosprêtre, S. Insights into the combination of neuromuscular electrical stimulation and motor imagery in a training-based approach. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 121, 941–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitry, F.; Martin, A.; Papaiordanidou, M. Torque gains and neural adaptations following low-intensity motor nerve electrical stimulation training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 127, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, C.; Stegmüller, J.; Blazevich, A.J.; Crettaz von Roten, F.; Kayser, B.; Neyroud, D.; Place, N. Modulation of torque evoked by wide-pulse, high-frequency neuromuscular electrical stimulation and the potential implications for rehabilitation and training. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, D.; Almuklass, A.M.; Amiridis, I.G.; Enoka, R.M. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation can improve mobility in older adults but the time course varies across tasks: Double-blind, randomized trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 108, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeit, L.; Rozand, V.; Millet, G.Y.; Gondin, J.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Lapole, T. Influence of wide-pulse neuromuscular electrical stimulation frequency and superimposed tendon vibration on occurrence and magnitude of extra torque. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 131, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegrzyk, J.; Fouré, A.; Vilmen, C.; Ghattas, B.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Mattei, J.P.; Place, N.; Bendahan, D.; Gondin, J. Extra Forces induced by wide-pulse, high-frequency electrical stimulation: Occurrence, magnitude, variability and underlying mechanisms. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 1400–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, J.M.; Anderson-Reid, J.M.; Graham, C.M.; Collins, D.F. Postactivation depression and recovery of reflex transmission during repetitive electrical stimulation of the human tibial nerve. J. Neurophysiol. 2011, 106, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.J.; Neyroud, D.; Kayser, B.; Westerblad, H.; Place, N. Intramuscular contributions to low-frequency force potentiation induced by a high-frequency conditioning stimulation. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.C.; Yates, L.M.; Collins, D.F. Turning off the central contribution to contractions evoked by neuromuscular electrical stimulation. Muscle Nerve 2008, 38, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.C.; Clair-Auger, J.M.; Lagerquist, O.; Collins, D.F. Asynchronous recruitment of low-threshold motor units during repetitive, low-current stimulation of the human tibial nerve. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosprêtre, S.; Gueugneau, N.; Martin, A.; Lepers, R. Central Contribution to Electrically Induced Fatigue depends on Stimulation Frequency. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosprêtre, S.; Gueugneau, N.; Martin, A.; Lepers, R. Presynaptic inhibition mechanisms may subserve the spinal excitability modulation induced by neuromuscular electrical stimulation. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2018, 40, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerquist, O.; Walsh, L.D.; Blouin, J.S.; Collins, D.F.; Gandevia, S.C. Effect of a peripheral nerve block on torque produced by repetitive electrical stimulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyroud, D.; Dodd, D.; Gondin, J.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Kayser, B.; Place, N. Wide-pulse-high-frequency neuromuscular stimulation of triceps surae induces greater muscle fatigue compared with conventional stimulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 116, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaiordanidou, M.; Billot, M.; Varray, A.; Martin, A. Neuromuscular fatigue is not different between constant and variable frequency stimulation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaiordanidou, M.; Stevenot, J.D.; Mustacchi, V.; Vanoncini, M.; Martin, A. Electrically induced torque decrease reflects more than muscle fatigue. Muscle Nerve 2014, 50, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina Dias Da Silva, S.; Neyroud, D.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Gondin, J.; Place, N. Twitch potentiation induced by two different modalities of neuromuscular electrical stimulation: Implications for motor unit recruitment: NMES Parameters & Potentiation. Muscle Nerve 2015, 51, 412–418. [Google Scholar]

- Vitry, F.; Martin, A.; Papaiordanidou, M. Impact of stimulation frequency on neuromuscular fatigue. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 2609–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyk, J.; Fouré, A.; Le Fur, Y.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Vilmen, C.; Guye, M.; Mattei, J.P.; Place, N.; Bendahan, D.; Gondin, J. Responders to Wide-Pulse, High-Frequency Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Show Reduced Metabolic Demand: A 31P-MRS Study in Humans. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiridis, I.G.; Mani, D.; Almuklass, A.; Matkowski, B.; Gould, J.R.; Enoka, R.M. Modulation of motor unit activity in biceps brachii by neuromuscular electrical stimulation applied to the contralateral arm. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 118, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbo, M.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Orizio, C.; Minetto, M.A. Muscle motor point identification is essential for optimizing neuromuscular electrical stimulation use. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botter, A.; Oprandi, G.; Lanfranco, F.; Allasia, S.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Minetto, M.A. Atlas of the muscle motor points for the lower limb: Implications for electrical stimulation procedures and electrode positioning. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 2461–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).