Abstract

The inherent complexities of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) architecture make its security and privacy issues becoming critically challenging. Numerous surveys have been published to review IoT security issues and challenges. The studies gave a general overview of IIoT security threats or a detailed analysis that explicitly focuses on specific technologies. However, recent studies fail to analyze the gap between security requirements of these technologies and their deployed countermeasure in the industry recently. Whether recent industry countermeasure is still adequate to address the security challenges of IIoT environment are questionable. This article presents a comprehensive survey of IIoT security and provides insight into today’s industry countermeasure, current research proposals and ongoing challenges. We classify IIoT technologies into the four-layer security architecture, examine the deployed countermeasure based on CIA+ security requirements, report the deficiencies of today’s countermeasure, and highlight the remaining open issues and challenges. As no single solution can fix the entire IIoT ecosystem, IIoT security architecture with a higher abstraction level using the bottom-up approach is needed. Moving towards a data-centric approach that assures data protection whenever and wherever it goes could potentially solve the challenges of industry deployment.

1. Introduction

The emergence of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) acts as a new network paradigm that has transformed traditional capturing, collecting, exchanging, processing, and storing data in the industry. IIoT goes beyond the typical consumer devices, people-to-people (P2P) and people-to-machine (P2M) communication networks associated with the IIoT. IIoT consists of billions of “things” intelligently connected via distributed communication networks, such as machine-to-machine (M2M) communication. These “things” ranging from ultra-efficient sensors and actuators, automation devices, embedded systems, heavy machines to high-performance gateways, with real-time data analytics always present.

In most cases, these “things” are uniquely identified by a variety of addressing schemes, includes electronic product code (EPC), ubiquitous code (ucode) and media access control (MAC) and Internet protocol (IP) address. IIoT promises a transformative future for businesses and governments, including intelligent automation, smart factories, intelligent healthcare, smart homes, smart cities, and intelligent transportation. IIoT’s inherent complexities introduce several security challenges and privacy risks. Several surveys and reviews on analyzing IoT and IIoT security threats and privacy challenges have been published over the last decade. These existing reviews and surveys are chronologically summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chronological summary of previous surveys in the IoT and IIoT security.

In 2010, Atzori et al. [1] and Weber [2] initiated the studies of IoT security issues. Atzori et al. [1] briefly discuss IoT’s security challenges and privacy issues, particularly in RFID and WSNs. Weber [2] focuses on the security requirements, privacy legislation and personal data protection of the IoT and RFID. Miorandi et al. [3] provided an overview of IoT’s data confidentiality, privacy, and trust issues. Subsequently, Ziegeldorf et al. [4] gave a detailed discussion on privacy threats and challenges of IoT. Zhao and Ge [5] discussed security issues from the IoT architecture perspective and divided IoT into perception, transport, and application layers. Then, Jing et al. [6] further conducted a comprehensive analysis of each layer’s features, security issues, and corresponding solutions. After that, the discussion of IoT security is nailed down on the specific technologies and scope. The study of Fremantle and Scott [7] focuses the analysis on the middleware of IoT security. Granjal et al. [8] centralized on the security of IoT communication protocols, includes physical and medium access control (MAC) layers, IPv6 over low power wireless personal area network (6LoWPAN), routing protocol for low power and lossy networks (RPL). Nguyen et al. [9] focus on the security of IoT and WSN communication protocols and their attack-resistant solutions. Subsequently, Airehrour et al. [10] gave a detailed security analysis of IoT routing protocols, particularly in low-power and lossy networks (LLN). Then, Qin et al. [11] briefly discussed IoT security from a data-centric perspective. Loi et al. [12] directed to analyze consumer IoT devices. Fernández-Caramés et al. [13] and Lao et al. [18] review the adaptability of blockchain in securing IoT applications and architecture. Hassija et al. [14] focus on discussing the security of IoT applications. Berkay et al. [15] and Tabrizi and Pattabiraman [16] directed to review the IoT security from a programming platform and code-level perspective. Amanullah et al. [17] discuss the relationship between deep learning, IoT security and big data technologies. Joao et al. [19] gave a general review of threat models and attack paths of IoT.

Recent IIoT surveys have primarily focused on the general IoT domain rather than the IIoT domain. They either provided a general overview of IoT security [1,2,3,4,5,10,11,19], or a detailed security analysis limited to specific IoT technologies or a particular layer of IoT architecture [6,7,8,9,12,15,16]. In addition, multiple surveys focused on exploring the relationship between IoT security and blockchain technologies [13,14,17,18]. Survey directions have lately been directed to be hammered down in the IIoT domain [20,21,22,23,24]. Deep learning in IIoT threat detection [20,22] and decentralised blockchain technologies [22,23] are the focus of these IIoT security surveys. However, none of them performs comprehensive security analysis on IIoT architecture and its recent industry solutions. Whether these deployed security solutions in the industry are still adequate to be adapted to secure IIoT architecture are questionable. The contributions of this article are:

- The difference between conventional systems and IIoT security concerns are summarized. Decentralized security approaches with high scalability, high interoperability, lightweight, and secure data processing have urged to address the high heterogeneity of “things,” high volume, and variety of collected sensor data, as opposed to conventional security systems focused on a centralized approach.

- Unlike recent IIoT architectures [24,25,26,27] that (i) focused on specific industries: aviation industry [25] and smart manufacturing [27], and (ii) targeted on particular technologies: M2M communication [24], green-aware multi-task scheduling [26] and 5G technology [27], we generalized the IIoT architecture into a four-layer architecture to cope with a wide of industry technologies and standards.

- Subsequently, we classify the recent IIoT technologies and standards into the proposed four-layer IIoT architecture

- The IIoT security requirements are further defined with the CIA+ model, includes confidentially(C), integrity(I), authentication(A), authorization and access control (A) and availability (A).

- A comprehensive end-to-end security analysis was conducted based on the defined IIoT CIA+ model. Subsequently, a fine-grained review on recent industry technologies and standards in each layer of the proposed IIoT architecture. The identified security risks and threats of these industry technologies, their deployed security countermeasures and future research works are summarized

- Lastly, we enumerate the open security challenges of IIoT and future research opportunities.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 investigate the characteristic of IIoT, highlights and report the difference between conventional systems and IIoT security concerns. Section 3 review the recent works of IIoT architecture and propose an IIoT security architecture based on the ITU-T Y.2060 IoT reference model [20], consisting of four layers: device layer, transport and network layer, processing layer and application layer. Then, we classify the recent industry technologies and standards into the proposed IIoT security architecture. Subsequently, Section 4 presents a comprehensive end-to-end security analysis on each layer of IIoT architecture by using the CIA+ model. The security risks and threats of each industry technology and their deployed security countermeasure, the gaps of today’s deficiency, and ongoing challenges are reported. Section 5 discusses the open security challenges, privacy issues and future research opportunities of IIoT. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2. IIoT Security Challenges and Concerns

The discussion of IIoT can be traced back to the connection between the physical world and ubiquitous “things” via the Internet during the early 1990s [28]. While IIoT was still in its infancy growth stage, these definitions’ scope is framed by different business interests and industry application scenarios [29,30,31,32,33]. For example, IETF and IEEE definitions are bounded by sensing technologies such as RFID and sensors [29,30], whilst the W3C expound the IoT with the Word Wide Web ecosystems [31]. IoT’s vision is to enable the connection of any “things” anytime. In most industry cases, we concluded that these “things” are associated with three fundamental characteristics: heterogeneity, unique identities and connectivity.

Along with the growth of IIoT for supporting industries, IIoT security and privacy issues have become more challenging. These security challenges inherit the conventional systems issues such as the advanced persistent threat (APT) and are further exacerbated by the complexity of the newer IIoT associated characteristics such as high heterogeneity, large scale of “things”, and cyber-physical systems. Table 2 further summarises the difference between conventional systems and IIoT security concerns.

Table 2.

The difference between conventional systems and IIoT security concerns.

The high heterogeneity of “things” on a large scale implicates the interoperability issues of cross-network communications, cyber-physical systems and IIoT enabled-technologies integration. The intricate maze of interoperability issues arises when: (i) heterogeneous devices and sensor nodes are identified with different naming and addressing schemes; (ii) exploit different data structures and formats; and (iii) communicate through different security protocols with varying requirements of the network (e.g., reliability, communication cost, latency and bandwidth) and integrated to provide a plethora of service applications. The question of whether these conventional security mechanisms and defence systems can be further integrated and standardized universally in resolving IIoT security complexities remains unanswered.

When there is a large scale of “things” (e.g., sensors in the aviation industry that consistently capture engine and aircraft health information during a flight) or diverse “things” in smart factories and manufacturing (e.g., sensors, edge devices, and smart grid) that collaborate to generate and exchange data continuously, these generated data from cyber-physical systems always come in big data flavour [17]. The data come in high volume and wide variety (e.g., structured, unstructured, quasi-structured, and semi-structured data), which need to be processed at a high velocity or analyzed nearly real-time, resulting in conventional data processing mechanisms being complicated or too expensive to scale and handle them efficiently.

As conventional data processing systems mainly were built-in houses, centralized management, and typically worked within the organization boundaries with a finite number of connected devices and users; therefore, security and privacy issues were not a concern. However, security protection and defences mechanisms are significantly different in the era of IIoT. Collected sensors data are locally processed and analyzed by IIoT gateway or automation system before sending to a centralized cloud platform for remote monitoring and post-analysis. The scalability of the existing security mechanisms to authenticate, fine-grained access control on massive IIoT resources has drawn the industry and researcher’s attention to move forward into a decentralized approach. Subsequently, more lightweight and highly efficient encryption schemes have been proposed recently to protect the tiniest “things” of IIoT, such as edge devices, sensor nodes and WSNs.

3. IIoT Architecture

3.1. Overview of IoT and IIoT Architecture

The origins of IIoT architecture can be traced back to the early designs of IoT architecture. In 2011, Ning and Wang [34] proposed a future IoT architecture called a U2IoT model. The U2IoT architecture works similar to a human nervous system that consists of unit IoT and ubiquitous IoT. The unit IoT serves as a local unit based on the man-like nervous model and is responsible for handling and managing diverse local IoTs. The ubiquitous IIoT follows the blueprint of social organization framework architecture and is responsible for integrating, managing, and controlling the collaboration among multiple IoT units across the industry, nationwide and worldwide. On the other hand, Guinard [35] worked on the concepts of web of things (WoT) by proposing an architecture that integrates the connection of “things” to the existing web services via existing web technologies. The proposed WoT architecture consists of five layers, includes accessibility, findability, sharing, composition and application layers. Subsequently, Gomez and Lopez [36] extended the WoT concepts into a hybrid distributed IoT architecture that consists of two distinct resource-oriented approaches: WoT and Tripe Space. WoT underlying a hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP) to interconnect the IoTs in the world wide web. Tripe Space applies semantic web protocol to exchange machine-processable data among the heterogeneous devices in the distributed local shared space. Vernet et al. [37] further customized the WoT architecture into the Smart Grid domain. Meanwhile, Olivier et al. [38] and Qin et al. [39] proposed another IoT architecture based on software defined networks (SDN) that consists of three layers: infrastructure layer with interconnecting network devices; control layer that comprises of SDN controllers; and an application layer that includes the applications for configuring the SDN. On the other hand, several research projects such as IoT-A [40], iCore [41], Sensei [42], and COMPOSE [43] have proposed a reference architecture of IoT at a high abstraction level.

A step closer to real-world industry implementation, several researchers [44,45,46,47,48] and vendors (i.e., Finnode, ThingWorx and Xively) use cloud technologies to tackle the IIoT heterogeneity issues and scalability services. These cloud-centric IIoT architectures use a centralized or decentralized cloud platform to process and manage the aggregated data from heterogeneous networks such as RFID, WSN, and body area network (BAN). These cloud-based IIoT platforms also provide API interfaces for industries to develop their IIoT applications. Researchers [49,50,51] recently attempted to integrate blockchain technologies in solving the decentralized issues of cloud-based IIoT architecture. Whether these blockchain-based architectures are practicable to support a large scale of things with their constrained resources in real-world industry implementation needs to be further investigated.

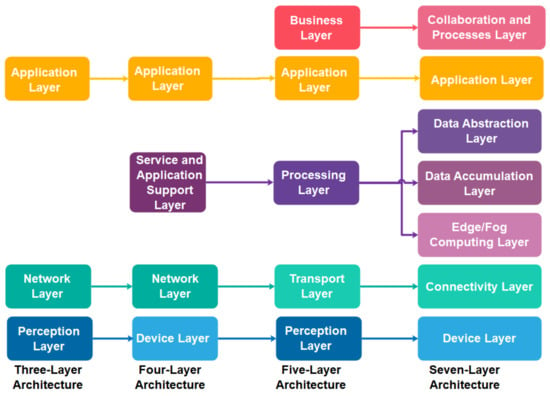

Generally, the initial widely accepted IIoT architecture is constructed based on the three-layer architecture [6,52], namely the perception, network, and application layers. The perception layer consists of the “things” identification and sensing technologies to collect and exchange the data. The network layer enables the communication and data transmission between the perception layer and the application layer. In most cases, it also involves data aggregation and curation process. Lastly, the application layer confluxes the data aggregated and virtualises the analysed result based on society, business and government demands. Different business interests reflect various IIoT applications for this layer, such as smart cities, intelligent health and smart transport. As three-layer architecture confronted the interoperability and scalability problem to well-suit into existing Internet and telecommunication networks, Wu et al. [53] extended the three-layer architecture into five-layer architecture by proposing a new business layer that resides on the top of the application layer and further dividing the previous network layer into processing layer and transport layer. The transport layer is responsible for transmitting the data generated from the perception layer into the processing layer. The processing layer focuses on processing, storing, and performing analytical works based on the application layer’s demand. While the application layer consists of diverse IIoT applications customized to each industry requirement, the business layer monitors these applications’ release and charging, conducts research on business and profit models, and controls privacy issues. Subsequently, ITU [52] proposed an IIoT reference architecture that consists of four layers: device layer, network layer, service and application support layer and application layer. The device layer is responsible for capturing and uploading data directly or indirectly via communication networks or gateway protocol, such as controller area network (CAN) bus, ZigBee and Bluetooth. The network layer is capable of handling network and transport connectivity. The service and application support layer aimed to provide a support function for various IIoT applications includes data curation, processing or storage. The application layer consists of IIoT applications. Thereafter, Cisco [54] proposed a seven-layer IIoT reference architecture comprising physical devices and controllers, connectivity, edge or fog computing, data accumulation, data abstraction, application, collaboration and processes layers. The physical devices and controllers layer includes various endpoints that can generate data, be queried and managed. The connectivity layer refers to the communication and connectivity either between devices, local networks or across the networks globally. Transforming network data flows into an appropriate data format for high-level data processing and storage occurred in the edge or fog computing layer. The data accumulation layer is responsible for data storage, whereas the abstraction layer involves aggregating and rendering data and storage to serve the client application. The application layer refers to the IIoT application such as business intelligence and big data analytic applications, sensors control applications and mobile applications. The relationship between the three-layer, four-layer, five-layer and seven-layer IIoT architectures is correlated, and their correlation is further mapped and illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The relationship and mapping of three-layer, four-layer, five-layer and seven-layer IIoT architectures.

3.2. The Proposed IIoT Security Architecture

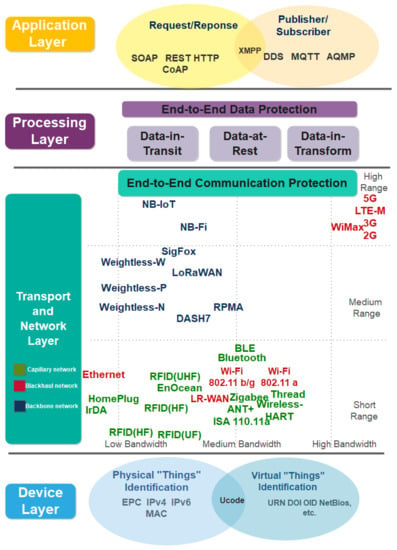

This subsection presents the proposed four-layer IIoT security architecture, as illustrated in Figure 2. We propose a four-layer IIoT security architecture to solve the shortcomings in current IIoT architectures [15,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], which are generic and difficult to address in industrial settings. For example, three-layer IoT architecture fails to satisfy the need for data curation, processing, and storage in IIoT. Subsequently, we classify recent industry IoT technologies and standards into the proposed IoT security architecture for conducting end-to-end security analysis, and the results are further discussed in Section 4. The security analysis on the device layer focuses on the physical and virtual “things” identification schemes used to connect to IIoT networks. These schemes include EPC, ucode, MAC and IP addresses. On the other hand, security analysis on transport and network layers focuses on IIoT communication technologies and standards, including capillary, backhaul, and backbone networks. The processing layer addresses the end-to-end data protection issues of IIoT data processing platform. Lastly, the application layer addresses the application threats, host-to-host, and client-server application protocol challenges, such as simple object access protocol (SOAP), representational state transfer hypertext transfer protocol (REST HTTP) and data distribution service for real-time systems (DDS).

Figure 2.

The proposed IIoT security architecture.

4. End to End Security Analysis on the Proposed IIoT Security Architecture

Security always serves as a linchpin of the public adoption of the new technologies. Any deficiencies of the security protection and defences system of IIoT has a latent risk to decelerate its adoption. This section conducts a comprehensive end-to-end security analysis based on the proposed IIoT security architecture. The security analysis is conducted based on the CIA+ model [7,55,56] described in Table 3.

Table 3.

CIA+ model of IIoT security.

4.1. Device Layer

The device layer consists of a large scale of “things” distributed across the IIoT infrastructure landscape. These heterogeneous “things” need to be identified uniquely before being interconnected and collaborate to capture, transfer, exchange and process data. Generally, these identification schemes and technologies must be unique, consistent, persistent and able to support the identity management and scalability issues of “things” [57,58]. Recently, several naming and address schemes have been used to define the unique identifier for both the physical “things” and virtual “things”, either within a local or global scope. These schemes are electronic product code (EPC), ubiquitous code (ucode), media access control (MAC) and Internet protocol (IP) addresses, and other higher layer identifiers and naming schemes such as uniform resource name (URN), object identifier (OID), digital object identifier (DOI), network basic input/output system (NetBIOS), etc.

4.1.1. Electronic Product Code (EPC)

Auto-ID Labs, MIT developed electronic product code (EPC), and it is widely used today to issue a unique 64-bit or 96-bit globally unique identifier (GUID) for physical “things” [59,60]. In most cases, EPC uses RFID tags to identify “things”, although it can also be used with optical data carriers, including linear bar codes, 2D barcodes, and data matrix symbols. Header, EPC manager number, object class, and serial number are the four components of an EPC identifier. The header identifies the length, structure, type, version and generation of the EPC. The EPC manager number is an entity responsible for maintaining the subsequent partitions. In most case refers to the manufacturer or company that produces the product and responsible for attaching the EPC. The object class identities a class of objects. The object is a product type, and it most likely refers to the stock keeping unit (SKU) [59,60].

Meanwhile, the object name service (ONS) is responsible for handling EPC information lookup services. However, ONS is established under the domain name system and lacks an authorization and authentication mechanism for handling ONS queries. The detailed security analysis of the EPC and its ONS lookup service are summarised in Table 4. Overall, the enforcement of more robust security properties (e.g., MD5 and SHA-1 hashing algorithms) on EPC is currently limited by its very constrained storage and computation power, i.e., less than 1000 bits in EPC Gen2 tags [60]. Subsequently, the scalability and extendibility of ONS and EPC networks issues need to be addressed to support the IIoT applications.

Table 4.

Security analysis on electronic product code (EPC) and its object naming service (ONS) architecture.

4.1.2. Ubiquitous Code (Ucode)

Ubiquitous code (ucode) was developed by Japan to uniquely identify objects, places, and concepts in the real world with a length of 128-bit. In the future, it can be further extended to the multiple of 128-bit, includes 256-bit, 384-bit, and 512-bit [70,71,72]. The ucode consists of five components: version, top-level domain code, class code, second-level domain code, and identification code. The ubiquitous ID center is responsible for establishing the ucode standard and its ubiquitous ID architecture consisting of ucode, ucode tag, communicator, resolution server, and information server. The recent ubiquitous ID architecture is secured with eTRON security framework, and its detailed analysis is presented in Table 5. Overall, security enforcement and privacy protection mechanisms exist on the ucode and its Ubiquitous ID architecture. Recently, the Ubiquitous ID Center is moving forward the ucode and its architecture to support IIoT’s scalability and interoperability issues, such as designing the hierarchical and distributed resolution server and information server.

Table 5.

Security analysis on ubiquitous code (ucode) and its architecture.

4.1.3. Media Access Control (MAC) and Internet Protocol (IP) Address

Media access control address (MAC), also known as physical address, hardware address, ethernet hardware address (EHA) and adapter address, is a unique identifier of the physical or virtual network node. These include network interface cards, firmware devices, hardware and software devices. The MAC address naming scheme is managed by IEEE. Recently, it follows three naming spaces standards, includes MAC-48 (e.g., Ethernet, Bluetooth, IEEE 802.11 wireless network, IEEE 802.5 token ring and ATM), EUI-48 (intended to replace MAC-48 and used for IEEE 802-based network applications) and EUI-64 (e.g., IPv6, Zigbee, 6LoWPAN and IEEE 802.15.4) [75]. Generally, MAC address consists of a 24-bit organization unique identifier (OUI) assigned by the IEEE registration authority and a 24-bit to 40-bit extension identifier assigned by the OUIs’ manufacturer.

Meanwhile, the Internet protocol (IP) address is a unique identifier that relies on Internet Protocol for network access and communication. Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) is a 32-bit identifier that is widely deployed today. However, with the emergence of IIoT and the dramatic growth of network-enabled devices, the IPv6 address is used to solve the root problem of IPv4 address exhaustion instead of using trivial solutions such as network address translation (NAT), virtual or private network addresses. IPv6 is a 128-bit identifier that consists of six parts: 3-bit format prefix (00,1 FP), 13-bit top-level aggregation identifier (TLA ID), 8-bit future use reservation (RES), 24-bit next-level aggregation identifier (NLA ID), 16-bit site-level aggregation identifier (SLA ID), and 64-bit interface identifier. The IP address focuses on network layer communication located at Layer 3 of the open system interconnection (OSI) model. The MAC address aims to transmit the data link layer or Layer 2 of the OSI model. Both IP address and MAC address can work together with address resolution protocol (ARP).

MAC and IP addresses still suffer from numerous security threats and privacy issues, as summarised in Table 6. Whether the convention security mechanisms (e.g., cryptographic algorithm, firewall, intrusion detection and prevention system) and recent IPsec security mechanism (e.g., authentication header (AH) protocol, encapsulation security payload (ESP), etc.) are sufficient to protect their confidentiality, authentication, and integrity is still questionable with the recent widespread of advanced persistent threat (APT) attacks. Moreover, IPsec only serves as a security standard, and there exists an interoperability issue of implementing secure communication protocol across diverse manufacturers. For instance, HP does not support the Diffie-Hellman Group 1 key on Internet key exchange (IKE).

Table 6.

Security analysis on media access control (MAC) and Internet protocol (IP) addresses.

4.2. Transport Layer

Transport Layer mainly provides ubiquitous connectivity for “things” and transmitting generated data from the device layer to the processing layer via a heterogeneous collection of communication networks, as illustrated in Figure 2. This section analyses the security of the transport layer based on its range of coverage and functional architecture, mainly capillary network, backhaul network and backbone network.

4.2.1. Capillary Network and Communication Technologies

The capillary network is defined as a local network that is intelligently connecting “things” (e.g., sensors, actuators, embedded devices) via short-range radio access, power link communication or infrared technologies [79,80]. These communication technologies include IrDA, Bluetooth, radio frequency identification (RFID), near field communication (NFC), INSTEON, Bluetooth, Bluetooth low energy (BLE), EnOcean, ultra-wideband (UWB), ANT+, HomePlug, ZigBee, WirelessHART, ISA110.11a and Thread [79,80,81,82,83,84], as illustrated in Figure 2. The detailed security analysis of these technologies is further summarised in Table 7.

Table 7.

Security analysis on capillary network communication technologies.

Generally, most capillary communication technologies are radio waves-based and wireless, except for IrDA and HomePlug, which use infrared light and power link communication. These wireless and radio waves-based communication technologies are generally vulnerable to wireless network threats, man-in-the-middle attacks, unauthorized message resource misappropriation. Meanwhile, the Bluetooth, BLE, WirelessHART and Thread technologies, exposure a higher security risk operating on popular radio frequency—2.4 GHz ISM band. Although most of them follow the IEEE 802.11 security standard, however, still subjected to a broad-spectrum jamming attack, 802.11 frame injection, 802.11 data replay, 802.11 Beacon, and authenticate flooding attack. Compared to others, UWB enjoys more robust security features as it operates on very low radiated power and narrow pulses, which increases wireless attack difficulties.

At the edge of IIoT networks, the ongoing security challenges such as interoperability issues of different security mechanisms (e.g., incompatibility of AES encryption in multichannel mode), scalability of key management and distribution, stronger and lightweight cryptography algorithm in the constrained resource of “things (low power, energy, storage size) and end-to-end communication and data protection across the heterogeneous interface are urgently called for a realization of a complete IIoT vision.

4.2.2. Backhaul Network and Communication Technologies

The backhaul network, which sits between the capillary and backbone networks, controls circulating data packets. Backhaul network also serves as a bridge in the heterogeneous capillary communication technologies. This section focuses on the analysis of the backhaul networks, which includes ethernet, wireless local area network (WLAN, or Wi-Fi), low rate-wireless personal area network (LR-WPAN), WiMax and universal mobile telecommunications system third generation (UMTS 3G) [96,97,98,99,100,101], as presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Security analysis on backhaul network and communication technologies.

Overall, these communication technologies satisfy the network security requirements, includes the physical and MAC layers security protection, message confidentiality and integrity check, authentication and authorization. However, with limited availability in protection, the strength of their defences countermeasure is varied and strictly dependent on their supported cryptographic algorithms and physical environments, includes the network range and coverage, i.e., WLAN enjoys lower network attack risk compared to WiMax.

As most backhaul communication technologies can be applied to support capillary communication (e.g., LR-WPAN) and backbone network (e.g., UMTS 3G and WiMax) in the domain, their role here is more focused on building a bridge or gateway for the data across heterogeneous capillary and backbone networks. Several security challenges need to be further addressed. These include: (i) end-to-end security protection over the bridge between capillary network and backbone networks; (ii) scalability of network size and bandwidth to support the rapid growth of IIoT data packets; (iii) interoperability with existing capillary communication technologies; (iv) stronger but lightweight security mechanisms on a constrained network resource; (v) more sophisticated access control scheme, such as identity-based or attributed-based access control; and (vi) efficient network key management and distribution.

Several low power and energy consumption networks have been developed recently to address the resource-constrained issues of IIoT. These works include low power wireless personal area network (6LoWPAN) and Wi-Fi Halow. Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has established a new protocol called IPv6 over low power wireless personal area network (6LoWPAN) to facilitate the communication between 802.15.4 enabled devices and the Internet. With header compression and address translation technique, IPv6 data packets are encapsulated into 802.15.4 data packets, thus enabling the integration of the 802.15.4 based network with the IPv6 network. Meanwhile, Wi-Fi alliance announced a new extension of Wi-Fi standard–802.11 ah, also known as WiFi-Halow. WiFi-Halow provides lower energy connectivity and a more extended range than traditional Wi-Fi, thus supporting a large scale of sensor stations or nodes.

4.2.3. Backbone Networks

The backbone network is a core network capable of interconnecting various backhaul networks and providing various services or gateways to facilitate communication and information exchange. In some cases, the backbone network may directly connect to a capillary network without a backhaul network. Backbone communication technologies consist of a wired network (IEEE 80.3 Ethernet), wireless network (IEEE 802.11, IEEE 802.16) and cellular network (2G, 3G, LTE, 4G and 5G). This section analysis the backbone communication technologies in the scope of IIoT long-range wide area network (LR-WAN) that includes NarrowBand-IoT (NB-IoT), long range WAN(LoRaWAN), narrowband fidelity (NB-Fi), weightless, SigFox and Ingenu random phase multiple access (RPMA) [101,102,103,104,105,106,107]. The detailed security analysis of each technology is summarised in Table 9.

Table 9.

Security analysis on backbone network and communication technologies.

Most of these technologies use cloud technologies to support their network architecture, including LoRaWAN, NB-Fi, SigFox and DASH7. The gateway or base station is responsible for forwarding the received “things” data packet to a cloud-based network via backhaul networks. The majority of these LR-WAN technologies are found to have general security properties such as using the AES-128 bit for data confidentiality, password-based authentication and access control and unique device identity [80].

4.3. Data Processing Layer

Data processing layer is responsible for transforming network data flows into valuable information (e.g., data pre-processing and curation), subsequently storing in a data warehouse and using high-level data processing such as aggregating, analyzing and interpreting data to serve client applications. In most cases, IIoT data comes with the Big Data characteristic when there is a large scale of “things” generate and exchange data continuously, such as in smart cities, aviation industry, logistic and shipment industry. IIoT technologies offer automated mechanisms such as cloud, edge and fog computing, machine-to-machine (M2M) communication technologies and underlying architecture to capture, collect and transmit data into the warehouse. On the other hand, big data technologies provide a data processing platform to support real-time analytics, such as Hadoop in a data warehouse to curate, process and analyze these machine data and turn it into valuable information. Because of the technological challenges of implementing in-house big data processing, these data are frequently stored and processed by third-party service providers such as Hortonworks, AmazonEMR, Cloudera, IBM, Zettaset, HDInsight, etc. As a result, the issues of data are exacerbated [108]. This section discusses end-to-end data protection for the data processing layer.

- Data-in-TransitData-in-transit refers to data being transmitted from the network layer to the data processing layer and application layer, either forwardly or backwardly. Most of big data technologies relies on Kerberos authentication scheme, public key infrastructure (PKI) and network encryption algorithm such as Hadoop remote procedure call (RPC), secure socket layer (SSL), HDFS data transfer protocol, simple authentication and security layer (SASL) mechanism, to ensure data confidentiality and authentication. However, these security mechanisms provide limited access control and authorization capabilities. A more sophisticated access control scheme such as role-based, identity-based and attribute-based can be plug-in with additional security packages such as Cloudera Sentry, DataGuise, IBM Infosphere Optima Data Masking, Datastax Enterprise, Zettaset Secure and others [108,109]. While data-in-transit protection in IIoT is mainly constructed based on the conventional security mechanism such as PKI, it is recommended to employ the bottom-up approach for heterogeneous and distributed networks infrastructure. The more challenging issue here is the key management and distribution problem, includes distribute key across distributed network and communication technologies, maintaining a large scale of the certificate, key revocation, recovery, and updating process. The key management proposal should be able to solve the scalability and interoperability issues to solve these problems.

- Data-at-RestData-at-rest refers to the data being stored in persistent storage such as a disk file. Conventional data-at-rest protection approaches include installing tamper-resistant hardware in third-party service providers, full-disk encryption, database-level encryption, table level encryption, and application-level encryption. Data are encrypted in the application layer before being inserted into the database. For instance, TrustDB and CipherBase provide data-at-rest protection based on the co-design of hardware and software [110].

- Data-in-TransformData-in-transform indicates that data is subjected to various means and manipulation methods, including performing query, sorting, mathematical operations, statistical analysis, and other functions on data to produce meaningful output. Protection of data-in-transform in IIoT is critically vital as their necessities in supporting real-time data analytics. Most of the recent big data processing service providers are still inadequate to support confidentiality during data transformation.

While conventional security mechanisms are limited to protect data-at-rest and data-in-transmit, the recent advancement of homomorphic encryption algorithms can be used to ensure the security of data-in-transform. Homomorphic encryption is a data encryption algorithm that works similar to a conventional data encryption algorithm, however, with the added capability to perform computation over encrypted data. Therefore, homomorphic encryption can serve as a comprehensive data protection solution to protect real-time analytics in IIoT. Recently, homomorphic encryption has been commercialized and released. Exiting products include CryptDB, MrCrypt, Crypsis and computing on masked data (CMD). CryptDB focuses on protecting MySQL query, MrCrypt supports MapReduce operation, Crypsis aimed for high-level data flow language such as Pig Latin, and CMD protecting NoSQL environment [109]. However, all of them are constructed based on a partial homomorphic encryption scheme, which can support simple arithmetic operation either additive or multiplicative homomorphism, still inadequate to enable artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities and machine learning algorithms. Most of these solutions lead to an increased data storage size (approximately 3.76 times in CryptDB), communication cost and bandwidth. A more efficient homomorphic encryption algorithm is needed to provide end-to-end protection for real-time data analytics in the IIoT data processing layer.

4.4. Application Layer

The application layer is a high abstraction level that leverages transport layer protocol, such as transmission control protocol (TCP) and user datagram protocol (UDP), to support data transfer and exchange between host-to-host client-server or peer-to-to-peer model. This section focuses on IIoT related session layer protocols includes Simple object access protocol (SOAP), representational state transfer hypertext transfer protocol (REST HTTP), data distribution service for real-time systems (DDS), message queue telemetry transport (MQTT), extensible messaging and presence protocol (XMPP), advanced message queuing protocol (AMQP), and constrained application protocol (CoAP) [111,112,113,114]. The details of their security analysis are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Security analysis on application layer.

Message exchange pattern (MEP) of these protocols can be categorized into two groups, request/response pattern (SOAP, REST HTTP, XMPP, CoAP) and subscribe/publish pattern (DDS, MQTT, XMPP, AQMP). Request/response pattern is the most commonly used synchronous pattern, in which the client requests information from the service by sending a request message and expects a response message from the service within a defined timeout. Subscribe/publish pattern is an asynchronous pattern that broadcasts data regularly to subscribers interested in their data, providing better network scalability and greater dynamic network topology.

Security mechanisms of these protocols are primarily dependent on transport layer security/secure socket layer (TLS/SSL) mechanism. Communication and data protection of MQTT, XMPP and AMQP are directly secured by using TLS/SSL. The communication of REST over an HTTP is encrypted with a TLS/SSL connection. The datagram transport layer security (DTLS) in CoAP is a stream-oriented TLS/SSL and inherits most of the features from TLS/SSL without any optimization for a constrained resource environment. SOAP enjoys a stronger security feature with its web service security (WS-Security). However, it spends much bandwidth in communicating metadata.

As TLS/SSL mechanism only provides limited security assurance for confidentiality, integrity and authentication, these protocols are still vulnerable to application layer threats (e.g., SQL injection, invalidated object indirect reference, DoS Attack and cross-site request forgery), SSL stripping, and password-based attacks (e.g., brute force attack, dictionary attack and rainbow table attack). Conventional cryptographic techniques such as MD5, DES, SHA-1, and RSA are being used to bolster their security defences, despite the fact that these algorithms have been broken and demonstrated to be insecure. In the future, several issues such as lightweight cryptography, reliability of message communication, interoperability issues with heterogeneous nodes, and the scalability of public key infrastructure to handle a large scale of key management need to be addressed for further spurring IIoT development.

5. Open Security Issues and Privacy of IIoT

IIoT is not a single technology; in turn, it leverages on various existing technologies such as sensing technologies, communication networks, high-performance processing platforms (e.g., cloud computing, M2M and edge computing), and also the new emerging technologies (e.g., LoRaWAN, NB-Fi and NB-IoT) to form its entire ecosystem. Consequently, IIoT security and privacy concerns are not merely focused on the issues of single piece technology. It encompasses a whole range of IIoT ecosystems, ranging from the physical security of connected nodes or devices, communication security of networks, data security during the transmission, transformation and storage of data to IIoT application security. This integrated heterogeneous environment becomes critically challenging with the employment of diverse security protocols, defence mechanisms, and standards across the IIoT architecture. Most of them employ conventional security approaches to build up their defences and protection systems for securing data and communication. Whether these deployed conventional mechanisms are still adequate to protect recent IIoT technologies is questionable, this section discusses IIoT’s open security and privacy issues.

- Security architecture and framework for IIoT.As the IIoT is still in its early stages of development, distinctive security models and designs were proposed as of late to address its security challenges and privacy concern issues. The point of these works are focused to make sure about a particular: (i) IIoT architecture, includes cyber-physical social based security model [109] focused on the U2IoT architecture [34] and Grid of security approach [38] targeted for securing SDN-based IIoT architecture; (ii) “things”, i.e., OSCAR [115] directed to protect constrained application protocol (CoAP) communication networks, Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs) based authentication protocol [116] for ensuring RFID framework; (iii) systems, includes a lightweight security system focused for IPsec, DTLS, and IEEE 802.15.4 connection layer. As no single security architecture and framework can fix the entire IIoT ecosystem, a design of IIoT security architecture with a higher abstraction level by using the bottom-up approach is needed. The proposal’s emphasis should be on interoperability issues to integrate different security mechanisms supported by IIoT technologies and cross-layer security solutions. Below are some of the highlighted issues in this domain. How can encrypted data be passed through different network layers from the physical layer, transport layer to application layer securely supported by different communication technologies? How can the things identified with a different addressing scheme secured under different security mechanisms communicate universally? How to exchange data securely with a different set of data formats (e.g., XML, JSON, etc.)? How to implement a secure communication protocol across a diverse manufacturer? Besides that, scalability issues should be further addressed to support rapid growth in IIoT, such as the scalability of PKI to manage a large scale of X.509 certificates.

- Limitation of conventional point-to-point defenses system and security mechanisms.The connection and communication across IIoT networks are recently protected via conventional network security protocols such as TLS/SSL, IPSec, RADIUS, IKE, etc. Most of these security protocols work based on point-to-point defences. For instance, TLS/SSL offers protection over the transport layer, IPSec focuses on IPv6 and IPv4 MAC, data link, transport and network layer. As IIoT communication technologies diversify, these conventional security mechanisms that focus on point-to-point defences are less efficient against the new cyber advanced persistent threats (APT) attacks and malicious insider attacks. The malicious attacks can target any vulnerabilities or weak points of IIoT networks or application systems. For instance, multi-hop wireless broadcast communication is vulnerable to eavesdropping. These situations become worst with the bring your own device (BYOD) or bring your own technology (BYOT) environments. The hijacked or backdoor installed devices can penetrate IIoT networks easily.

- Lightweight and stronger cryptographic algorithmMost IIoT communication protocols and technologies still rely on conventional cryptographic algorithms such as RSA, MD5, RC4, and DES-56 to ensure data confidentiality and secure communication. However, some of these algorithms have been proven insecure and subjected to quantum attacks. Therefore, a more robust cryptographic algorithm needed to be adapted into these communication protocols, such as quantum-resistant NTRU and BLISS algorithms. Besides that, a lightweight but secure algorithm is highly sought after to protect the IIoT constrained resources (e.g., low energy, low storage and low bandwidth communication). For instance, RC5, SkipJack, high security and lightweight (HIGHT), corrected block TEA (XXTEA), SAFER++ have been proposed recently to secure wireless sensor networks [117,118].

- Limitation of IPSec and TLS/SSL mechanismMost IIoT technologies rely on IPSec and TLS/SSL mechanisms to secure their communication and data transmission. Both provide confidentiality, integrity and authentication of the message, with limited authorization and access control. However, without the assurance of availability and non-repudiation, they are still vulnerable to application-layer threats. Besides that, the scalability and interoperability issues of both IPSec and TLS/SSL need to be addressed further. These include scalability of key management and distribution to handle a large of “things” network keys, the implementation issues in a lightweight and constrained resource protocol such as CoAP.

- Password-based authentication schemeMost IIoT authentication schemes are still constructed based on single-factor authentication (SFA)—user’s ID and password. Some network keys are further derived from the user’s password. However, these short, weak, easily predictable and repeated passwords further paring security defences mechanism and subjected to a brute-force attack, dictionary attack, rainbow attack, etc. Recently, the two-step verification mechanism can be activated optionally, in which four- or six-digit verification code will be sent to a user via SMS or voice call, or alternative can be retrieved from the time-based one time password apps.

- Towards a data-centric approach for end-to-end data protectionAs no single security mechanism and framework can fix the entire IIoT ecosystem due to its inherent, the data-centric approach can serve as another alternative towards end-to-end security for IIoT. Instead of targeting to protect different networks, communication technologies and protocols, the data-centric approach aims to protect the data itself—whenever and wherever it goes. These data-centric approaches include homomorphic encryption, attribute-based encryption scheme, private information retrieve scheme, searchable encryption scheme and multi-party computation scheme [119,120,121,122]. Most of these schemes can assure data-in-transit, data-in-transform and data-at-rest security, thus significantly resolving the interoperability and scalability issues of integrating different security mechanisms across IIoT networks and technologies. These schemes also significantly reduce the risk of privacy (e.g., collection and abuse use of personal data, habits and geolocation). Homomorphic encryption, for example, permits a third-party data processing centre to undertake real-time analytical work without having to decrypt data collected from any industry.

6. Conclusions

This article provides a comprehensive study of IIoT security architecture and associated industry technologies and standards. Firstly, this article discussed the IIoT definitions, IIoT characteristics and highlighted IIoT security concerns that are different from the existing data security concerns. Subsequently, the paper reviewed current IIoT architectures and proposed a new four-layer IIoT security architecture. The proposed security architecture is constructed based on a bottom-up approach. A comprehensive end-to-end security analysis on each layer of the proposed IIoT architecture is conducted. This includes assessed security requirements based on CIA+ model, highlighted their recent industry counter measurement and deficiencies, discussed ongoing security challenges and future works. The security analysis on the device layer focuses on physical and virtual “things” identification schemes, including EPC, ucode, MAC, and IP addresses. The analysis on transport and network layer is further sub-divided into the capillary network (IrDA, RFID, NFC, INSTEON, Bluetooth, BLE, EnOcean, UWB, ANT+, HomePlug, ZigBee, ISA 110.11a, WirelessHART and Thread), Backhaul network (Ethernet, WLAN, LR-WAN, WiMax, 3G) and backbone network (NB-IoT, LoRaWAN, NB-Fi, NWAVE, SigFox, RPMA and DASH7), based on their range of coverage and functionalities. Security analysis on the processing layer focuses on end-to-end data protection, includes data-in-transit, data-at-rest, and data-in-transform. Finally, the application layer studies focused on SOAP, REST HTTP, DDS, MQTT, XMPP, AMQP and CoAP protocol. This article also highlighted IIoT’s open security and privacy issues, including constructing a standardized IIoT security architecture in a bottom-up approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.T. and A.S.; methodology, S.F.T. and A.S.; validation, S.F.T. and A.S.; formal analysis, S.F.T. and A.S.; investigation, S.F.T. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.T.; writing—review and editing, S.F.T. and A.S.; visualization, S.F.T.; supervision, A.S.; project administration S.F.T.; funding acquisition, S.F.T. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universiti Malaysia Sabah and Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the data may involve confidential information of our research group.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Malaysia Fundamental Research Grant Scheme-FRG0530-2020 and Universiti Malaysia Sabah Research Grant-SDK0165-2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Atzori, L.; Iera, A.; Morabito, G. The Internet of Things: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 2787–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.H. Internet of Things–New security and privacy challenges. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2010, 26, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miorandi, D.; Sicari, S.; De Pellegrini, F.; Chlamtac, I. Internet of things: Vision, applications and research challenges. Ad Hoc Netw. 2012, 10, 1497–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Ge, L. A Survey on the Internet of Things Security. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference Computational Intelligence Security-CIS, Emeishan, China, 14–15 December 2013; pp. 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegeldorf, J.H.; Morchon, O.G.; Wehrle, K. Privacy in the Internet of Things: Threats and challenges. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2014, 7, 2728–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Q.; Vasilakos, A.V.; Wan, J.; Lu, J.; Qiu, D. Security of the Internet of Things: Perspectives and Challenges. Wirel. Netw. 2014, 20, 2481–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremantle, P.; Scott, P. A Security Survey of Middleware for the Internet of Things. PeerJ PrePrints 2015, 3, e1521. Available online: https://peerj.com/preprints/1241.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Granjal, J.; Monteiro, E.J.; Silva, S. Security for the Internet of Things: A Survey of Existing Protocols and Open Research Issues. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 1294–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Laurent, M.; Oualha, N. Survey on Secure Communication Protocols for the Internet of Things. Ad Hoc Netw. 2015, 32, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airehrour, D.; Gutierrez, J.; Ray, S.K. Secure Routing for Internet of Things: A Survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 66, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Falkner, N.J.G.; Dustdar, S.; Wang, H.; Vasilakos, A.V. When Things Matter: A Survey on Data-Centric Internet of Things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 64, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, F.; Sivanathan, A.; Hassan, H.G.; Radford, A.; Sivaraman, V. Systematically Evaluating Security and Privacy for Consumer IoT Devices. In Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Internet of Things Security and Privacy, New York, NY, USA, 3 November 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Caramés, T.M.; Fraga-Lamas, P. A Review on the use of Blockchain for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 32979–33001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Saxena, V.; Jain, D.; Goyal, P.; Sikdar, B. A Survey on IoT Security: Application Areas, Security Threats, and Solution Architectures. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 82721–82743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkay, C.; Fernandes, E.; Pauley, E.; Tan, G.; McDaniel, P. Program Analysis of Commodity IoT Applications for Security and Privacy: Challenges and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, F.M.; Pattabiraman, K. Design-Level and Code-Level Security Analysis of IoT Devices. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2019, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanullah, M.A.; Habeeb, R.A.A.; Nasaruddin, F.H.; Gani, A.; Ahmed, E.; Nainar, A.S.M.; Akim, N.M.; Imran, M. Deep Learning and Big Data Technologies for IoT security. Comput. Commun. 2020, 141, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, L.; Li, Z.; Hou, S.; Xiao, B. A Survey of IoT Applications in Blockchain Systems: Architecture, Consensus, and Traffic Modeling. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, B.; Sequeiros, F.; Francisco, T.; Chimuco, M.; Samaila, G.; Freire, M.M.; Pedro Inácio, R.M. Attack and System Modeling Applied to IoT, Cloud, and Mobile Ecosystems: Embedding Security by Design. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polychronou, N.-P.; Thevenon, P.-H.; Puys, M.; Beroulle, V. A Comprehensive Survey of Attacks without Physical Access Targeting Hardware Vulnerabilities in IoT/IIoT Devices, and Their Detection Mechanisms. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Systems 2021, 27, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, P.D.; Fernandez, C.M.; Soares, V.N.G.J.; Caldeira, J.M.L.P.; Silva, H. Development of Technological Capabilities through the Internet of Things (IoT): Survey of Opportunities and Barriers for IoT Implementation in Portugal’s Agro-Industry. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Leung, V.C. Deep reinforcement learning for blockchain in industrial IoT: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2021, 191, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Idrees, Z.; e Huma, Z.; Ahmad, J. Blockchain technology for the Industrial Internet of Things: A comprehensive survey on security challenges, architectures, applications, and future research directions. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 191, e4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, A. IIoT Reference Architecture. In Industry 4.0; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Misra, S. SEGA: Secured Edge Gateway Microservices Architecture for IIoT-based Machine Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamis, R.D.; Mohamed, T.E.-W.; Mahmoud, M.F. Towards sustainable industry 4.0: A green real-time IIoT multitask scheduling architecture for distributed 3D printing services. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.R.V.; Kumarswamy, P.; Phridviraj, M.S.B.; Venkatramulu, S.; Subba, R.V. 5G Enabled Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) Architecture for Smart Manufacturing. Lect. Notes Data Eng. Commun. Technol. 2021, 63, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union. Overview of the Internet of Things. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/dologin_pub.asp?lang=e&id=T-REC-Y.2060-201206-I!!PDF-E&type=items (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Ashton, K. That ‘Internet of Things’ Thing. RFiD J. 2009, 22, 97–114. Available online: http://www.itrco.jp/libraries/RFIDjournal-That%20Internet%20of%20Things%20Thing.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Minerva, R.; Biru, A.; Rotondi, D. Towards a definition of the Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Internet Things 2015, 1–86. Available online: https://iot.ieee.org/images/files/pdf/IEEE_IoT_Towards_Definition_Internet_of_Things_Revision1_27MAY15.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- W3C. Web of Things at W3C. Available online: https://www.w3.org/WoT/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Noura, M.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Gaedke, M. Interoperability in Internet of Things: Taxonomies and Open Challenges. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2019, 24, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet Architecture Board (IAB). Architectural Considerations in Smart Object Networking, RFC 7452. Available online: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7452 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Ning, H.; Wang, Z. Future Internet of Things Architecture: Like Mankind Neural System or Social Organization Framework? IEEE Commun. Lett. 2011, 15, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinard, D. A Web of Things Application Architecture-Integrating the Real-World into the Web. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland, 2011. Available online: https://webofthings.org/dom/thesis.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Gómez-Goiri, A.; López-de-Ipiña, D. On the Complementarity of Triple Spaces and the Web of Things. In Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on Web of Things-WoT 11, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 June 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernet, D.; Zaballos, A.; Martin De Pozuelo, R.; Caballero, V. High Performance Web of Things Architecture for the Smart Grid Domain. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2015, 11, 347413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, F.; Carlos, G.; Florent, N. New Security Architecture for IoT Network. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 52, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Denker, G.; Giannelli, C.; Bellavista, P.; Venkatasubramanian, N. A Software Defined Networking Architecture for the Internet-of-Things. In Proceedings of the IEEE Network Operator Management Symposium (NOMS), Krakow, Poland, 5–9 May 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Boussard, M.; Bui, N.; Carrez, F. Project Deliverable D1.5–Final Architectural Reference Model for IoT, IoT-A. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/257521 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- iCore? D2.5 Final Architecture Reference Model, iCore. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/projects/cnect/8/287708/080/deliverables/001-20141031finalarchitectureAres20143821100.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- SENSEI. Available online: http://www.sensei-project.eu/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- D1.2.2 Final COMPOSE Architecture Document, FP7-317862-COMPOSE. 2018. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/317862 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A Vision, Architectural Elements, and Future Directions. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, I.; Militano, L.; Nitti, M.; Atzori, L.; Iera, A. MIFaaS: A Mobile-IoT-Federation-as-a-Service model for dynamic cooperation of IoT Cloud Providers. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2016, 70, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Kaliyar, P.; Lal, C. CENSOR: Cloud-enabled secure IoT architecture over SDN paradigm. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2018, 31, e4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, S. A Cloud-based Middleware for Self-Adaptive IoT-Collaboration Services. Sensors 2019, 19, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadas, T.J.; Subramanian, R.R. Paradigms for Intelligent IOT Architecture. In Principles of Internet of Things (IoT) Ecosystem: Insight Paradigm; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 174, pp. 67–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, R.A.; Li, J.P.; Nazeer, M.I.; Khan, A.N.; Ahmed, J. DualFog-IoT: Additional Fog Layer for Solving Blockchain Integration Problem in Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 169073–169093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdinejad, A.; Parizi, R.M.; Dehghantanha, A.; Zhang, Q.; Choo, K.-K.R. An Energy-efficient SDN Controller Architecture for IoT Networks with Blockchain-based Security. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2020, 13, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhane, D.V.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Muhammad, G.; Wang, J. Blockchain-enabled Distributed Security Framework for Next Generation IoT: An Edge-Cloud and Software Defined Network Integrated Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6143–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telecommunication Standardization Sector ITU-T Y.2002 Overview of Ubiquitous Networking and of Its Support in NGN. Int. Telecommun. Union 2009. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-Y.2002-200910-I/en (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Wu, M.; Lu, T.J.; Ling, F.Y.; Sun, J.; Du, H.Y. Research on the Architecture of Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference Advanced Computer Theory Engineering 2010, Chengdu, China, 20–22 August 2010; pp. 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candanedoa, I.-S.; Alonso, R.S.; Corchado, J.M.; González, S.R.; Vara, R.C. A review of edge computing reference architectures and a new global edge proposal. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 99, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU-T X.800. Security Architecture for Structure and Applications. Int. Telecommun. Union 1991. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/dologin_pub.asp?lang=e&id=T-REC-X.800-199103-I!!PDF-E&type=items (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- ITU-T X.805. Security Architecture for Systems Providing End-to-End Communications. Int. Telecommun. Union 2003. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/dologin_pub.asp?lang=e&id=T-REC-X.805-200310-I!!PDF-E&type=items (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Houyou, A.M.; Huth, H.-P.; Mechs, S.; Völksen, G.; Hof, H.-J.; Kloukinas, C.; Siveroni, I.; Trsek, H. IoT@Work WP 2 – COMMUNICATION NETWORKS D2.1 – IOT ADDRESSING SCHEMES APPLIED TO MANUFACTURING. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321587894_IoTWork_WP_2-COMMUNICATION_NETWORKS_D21-IOT_ADDRESSING_SCHEMES_APPLIED_TO_MANUFACTURING?enrichId=rgreq-49ee97e346acdaa334e3ab19db2fbe52-XXX&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzMyMTU4Nzg5NDtBUzo1Njg1OTkzNTU2OTUxMDRAMTUxMjU3NjA1ODQxNA%3D%3D&el=1_x_2&_esc=publicationCoverPdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Internet of Things: The New Government to Business Platform: A Review of Opportunities, Practices, and Challenges. In The World Bank Group 2017, 1–112. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/610081509689089303/pdf/120876-REVISED-WP-PUBLIC-Internet-of-Things-Report.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Armene, F.; Barthel, H.; Dietrich, P.; Duker, J.; Floerkemeier, C.; Garrett, J.; Harrison, M.; Hogan, B.; Mitsugi, J.; Preishuber-Pfluegl, J.; et al. The EPCglobal Architecture Framework. Available online: https://www.gs1.org/sites/default/files/docs/architecture/architecture_1_3-framework-20090319.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- EPC Tag Data Standard. Released 1.11, GS1 2017. Available online: https://www.gs1.org/sites/default/files/docs/epc/GS1_EPC_TDS_i1_11.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- NXP Semiconductors. MIFARE DESFire EV1. Available online: https://www.nxp.com/products/rfid-nfc/mifare-hf/mifare-desfire/mifare-desfire-ev1:MIFARE_DESFIRE_EV1_2K_8K (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- ORIDAO, Secured EPC Gen2 RFID ASIC. Available online: http://html.transferts-lr.org/ORIDAO.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Shugo, M.; Dai, W.; Yang, L.; Kazuo, S. Fully Integrated Passive UHF RFID Tag for Hash-Based Mutual Authentication Protocol. Sci. World J. 2015, 498610, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolando, T.R. Priacy in RFID and Mobile Objects. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain, 2012. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/86942/Thesis?sequence=1 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Li, L.; Lin, H.; Yong, Z. Implementation of a New RFID Authentication Protocol for EPC Gen2 Standard. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Mujahid, U.; Najam-ul-Islam, M. Ultralightweight resilient mutual authentication protocol for IoT based edge networks. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, N.; Waheed, A.; Zareei, M.; Alanazi, F. An Improved Identity-Based Generalized Signcryption Scheme for Secure Multi-Access Edge Computing Empowered Flying Ad Hoc Networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 120704–120714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xie, R.; Yu, F.R.; Huang, T.; Liu, Y. Potential Identity Resolution Systems for the Industrial Internet of Things: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.Y.; Zhu, S.Y.; Xie, B.; Tian, J. Advanced EPC network architecture based on hardware information service. ZTE Commun. 2020, 18, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamura, K. Ubiquitous ID Technologies 2011. uID Center. 2011. Available online: https://www.tron.org/ja/wp-content/themes/dp-magjam/pdf/en_US/UID910-W001-110324.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Ishikawa, C. A URN Namespace for ucode. RFC 6588. 2012. Available online: https://ietf.org/rfc/rfc6588.html (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Tian, Y.; Shen, J.; Tao, Y.; Liu, J. Development and Prospect of Identification Service Technology for Advanced Manufacturing. In China’s e-Science Blue Book 2018; Chinese Academy of Sciences, Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.F.; Sakamura, K. A Distributed Approach to Delegation of Access Rights for Electronic Health Records. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC), Barcelona, Spain, 19–22 January 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohachab, A.; Lohachab, A.; Jangra, A. A Comprehensive Survey of Prominent Cryptographic Aspects for Securing Communication in Post-Quantum IoT Networks. Internet Things 2020, 9, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.; El-Kader, S.M.A.; Youssef, M.I.; Tarrad, I.F. M2M in 5G Communication Networks: Characteristics, Applications, Taxonomy, Technologies, and Future Challenges. In Fundamental and Supportive Technologies for 5G Mobile Networks; IGI Global: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, S. IP Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP). RFC 4303. 2005. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc4303 (accessed on 4 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Thakor, V.A.; Razzaque, M.A.; Khandaker, M.R.A. Lightweight Cryptography Algorithms for Resource-Constrained IoT Devices: A Review, Comparison and Research Opportunities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 28177–28193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liew, S.C.; Wang, T. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Multiple Access for Heterogeneous Wireless Networks with Imperfect Channels. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capillary Networks–A Smart Way to Get Things Connected. Ericsson Review 2014, 8. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/4ae11c/assets/local/reports-papers/ericsson-technology-review/docs/2014/er-capillary-networks.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- GSM Association Official Document CLP.14-IoT Security Guidelines for Network Operators Version 2.2. 29 February 2020. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/iot/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CLP.14-v2.2-GSMA-IoT-Security-Guidelines-for-Network-Operators.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Rubio, J.E.; Roman, R.; Lopez, J. Integration of a Threat Traceability Solution in the Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 6575–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutras, D.; Stergiopoulos, G.; Dasaklis, T.; Kotzanikolaou, P.; Glynos, D.; Douligeris, C. Security in IoMT Communications: A Survey. Sensors 2020, 20, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghili, S.F.; Mala, H.; Kaliyar, P.; Conti, M. SecLAP: Secure and lightweight RFID authentication protocol for Medical IoT. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucouvalas, A.; Chatzimisios, P.; Ghassemlooy, Z.; Uysal, M.; Yiannopoulos, K. Standards for indoor Optical Wireless Communications. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2015, 53, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.; Bibon, S.D.; Hossain, M.S.; Atiquzzaman, M. Security threats in Bluetooth technology. Comput. Secur. 2018, 74, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeadally, S.; Siddiqui, F.; Baig, Z. 25 Years of Bluetooth Technology. Future Internet 2019, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa Lorenzo, S.; Añorga Benito, J.; García Cardarelli, P.; Alberdi Garaia, J.; Arrizabalaga Juaristi, S. A Comprehensive Review of RFID and Bluetooth Security: Practical Analysis. Technologies 2019, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, K.; Vogl, B.; Rademacher, M. Security Mechanisms of wireless Building Automation Systems; Technical Report; Hochschule Bonn-Rhein-Sieg: Sankt Augustin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharina, H.-S. A Formal Analysis of EnOcean’s Teach-in and Authentication. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series (ICPS), Vienna, Austria, 17–20 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestourie, B. UWB Secure Ranging and Localization. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France, 4 December 2020. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03136561/document (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Rensburg, R.V. System Control Applications of Low-Power Radio Frequency Devices. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 889. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/889/1/012016/ (accessed on 4 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.; Wressnegger, C. Security Analysis of Devolo HomePlug Devices. In Proceedings of the12th European Workshop on Systems Security, Dresden, Germany, 25 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, S. HomePlugAV PLC: Practical attacks and backdooring. Additional information after the presentation made at NoSuchCon. 2014. Available online: https://penthertz.com/resources/NSC2014-HomePlugAV_attacks-Sebastien_Dudek.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Nardo, M.D.; Yu, H. Intelligent Ventilation Systems in Mining Engineering: Is ZigBee WSN Technology the Best Choice? Appl. Syst. Innov. 2021, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boom, B.V.D. State machine inference of Thread networking protocol. Bachelor’s Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 29 June 2018. Available online: https://www.cs.ru.nl/bachelors-theses/2018/Bart_van_den_Boom___4382218___State_machine_inference_of_thread_networking_protocol.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Coldrey, M.; Engström, U.; Helmersson, K.W.; Hashemi, M. Wireless backhaul in future heterogeneous networks. Ericsson Review. 2014. Available online: https://www.hit.bme.hu/~jakab/edu/litr/Mobile_backhaul/er-wireless-backhaul-hn.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Liyanage, M.; Gurtov, A. Secured VPN Models for LTE Backhaul Networks. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Fall), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 3–6 September 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Chehri, A.; Fortier, P. Review of optical and wireless backhaul networks and emerging trends of next generation 5G and 6G technologies. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, H. A brief survey of radio access network backhaul evolution: Part II. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2013, 51, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, N.; German, R.; Dressler, F. Simulation study of IEEE 802.15.4 LR-WPAN for industrial applications. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2009, 10, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembe, M.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.; Masonta, M.; Ngqondi, T. A survey on low-power wide area networks for IoT applications. Telecommun. Syst. 2019, 71, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, S.S.; Wei, Y.; Hwang, S.-H. A survey on LPWA technology: LoRa and NB-IoT. ICT Express 2016, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, F.; Stephen, B. A Comparative Survey of LPWA Networking. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.04222. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.04222.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Pham, T.L.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, H.; Bui, V.; Nguyen, V.H.; Jang, Y.M. Low Power Wide Area Network Technologies for Smart Cities Applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju, South Korea, 16–18 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, H.S.; Huang, H.; Viswanathan, H. Wide-area Wireless Communication Challenges for the Internet of Things. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, B.; Adelantado, F.; Bartoli, A.; Vilajosana, X. Exploring the Performance Boundaries of NB-IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 5702–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayouni, H.; Hamdi, M. A novel energy-efficient encryption algorithm for secure data in WSNs. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 4754–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.F.; Samsudin, A. A Survey of Homomorphic Encryption for Outsourced Big Data Computation. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2016, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tan, S.F.; Samsudin, A.; Suraya, A. Securing Big Data Processing with Homomorphic Encryption. TEST Eng. Manag. 2020, 82, 11980–11991. Available online: https://www.testmagzine.biz/index.php/testmagzine/article/view/2770/2442 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Ning, H.; Liu, H. Cyber-Physical-Social Based Security Architecture for Future Internet of Things. Adv. Internet Things 2012, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazis, V.; Gortz, M.; Huber, M.; Leonardi, A.; Mathioudakis, K.; Wiesmaier, A.; Vasilomanolakis, E. A survey of technologies for the internet of things. In Proceedings of the International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 24–28 August 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]