Abstract

Habitat restoration followed by species reintroduction is a key strategy for biodiversity recovery. For species with parasitic life stages, such as the freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera), host suitability is crucial. Before a planned reintroduction of mussels into a newly constructed nature-like fishway, we tested the compatibility of four brown trout (Salmo trutta) strains from local and foreign drainages as hosts for mussels from a nearby river. The strains included (a) a local sympatric wild strain, (b) a local allopatric wild strain from near the fishway, (c) a local allopatric hatchery strain used for stocking, and (d) a foreign allopatric hatchery strain. After forty days, infestation rates of the parasitic mussel glochidia did not differ significantly among strains, indicating that all could serve as hosts. Glochidia that developed on the local allopatric hatchery strain had the highest growth rate, suggesting the highest suitability for production under laboratory conditions. While stocking hatchery strains can have negative ecological impacts, local wild fish provide a sustainable option without continued introductions of hatchery strains. If wild fish are scarce, carefully chosen hatchery strains may support juvenile mussel production and reintroduction under controlled conditions. Our findings highlight the importance of evaluating host compatibility before mussel reintroduction and fish stocking.

1. Introduction

Habitat restoration is a common action taken to preserve threatened aquatic organisms. If a certain strain has gone extinct before such restoration efforts are put into practice, reintroduction of individuals of a different strain can be the only viable option to repopulate a habitat [1]. Identifying the most suitable source strain for a reintroduction program is typically based on ecological and genetic aspects of the candidate strains. If no such information is available for the candidates, the source strain geographically closest to the extinct strain is often chosen [2]. For threatened species with a parasitic life stage, conservationists not only have to consider which strain of the species in question to reintroduce, but also to take into account the compatibility of the available host strains to ensure a functional parasite-host interaction [3,4,5].

Freshwater mussels of the order Unionida constitute one of the most threatened taxa on earth [6], often because of their dependence on a host fish during their larval parasitic stage [7]. After falling off the host fish, unionid mussels become benthic filter feeders, and in dense mussel populations, their filter feeding can have a fundamental impact on ecosystem functions [8,9]. Re-establishment of threatened mussels can therefore both contribute to mussel conservation and to restore ecosystem functions in freshwater [10].

The freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera, Linnaeus 1758; FPM) is a host specialist on brown trout (Salmo trutta, Linnaeus 1758) or Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar, Linnaeus 1758) [11,12]. The FPM is decreasing in abundance and viability throughout its distribution [13], and this decline has mainly been attributed to anthropogenic factors [3,14]. A lack of viable host fish populations caused by human activities has, however, also been proposed as a threat to FPM recruitment [4,15,16,17]. In fact, salmonid densities are decreasing in several European countries [18,19,20,21,22,23] and have been attributed to the presence of migration barriers [7,21], overfishing [17], pollution [21], and infection by salmon lice [23].

The release of hatchery-reared salmonids is a common measure to compensate for the loss of natural fish reproduction and to support recreational and commercial fisheries [24]. This measure is problematic because introduced hatchery-reared fish may outcompete or genetically contaminate locally adapted wild fish populations [25,26,27]. Release of hatchery fish also has the potential to affect FPM populations if the suitability for glochidia infestation differs between host fish strains [28,29]. For example, local adaptation between sympatric mussel and host fish populations can be affected if hatchery fish strains are introduced in FPM streams, and lead to changes in the survival of encysted glochidia and juvenile mussel production [5,29].

In the River Dalälven catchment in south-central Sweden, FPM habitat was lost due to hydropower development. A nature-like fishway was built to facilitate fish passage and compensate for the lost habitat, and to introduce the FPM to the fishway, mussels from a healthy population in a stream in the same catchment were used. The natural colonization of brown trout in the fishway was slow, and so actions were taken to identify a suitable host fish strain to be introduced with the mussel to create a self-sustaining FPM population in the artificial habitat.

This study aimed to evaluate the host suitability of four different brown trout strains for supporting the reproduction of the FPM population selected for introduction to the nature-like fishway. Using wild trout for introduction programs could potentially have negative effects on the wild source populations, whereas using hatchery strains could, just as for foreign wild trout, result in a parasite-host mismatch. We thus compared the host suitability of wild and hatchery-reared trout strains from local and foreign catchments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mussel and Fish Origin

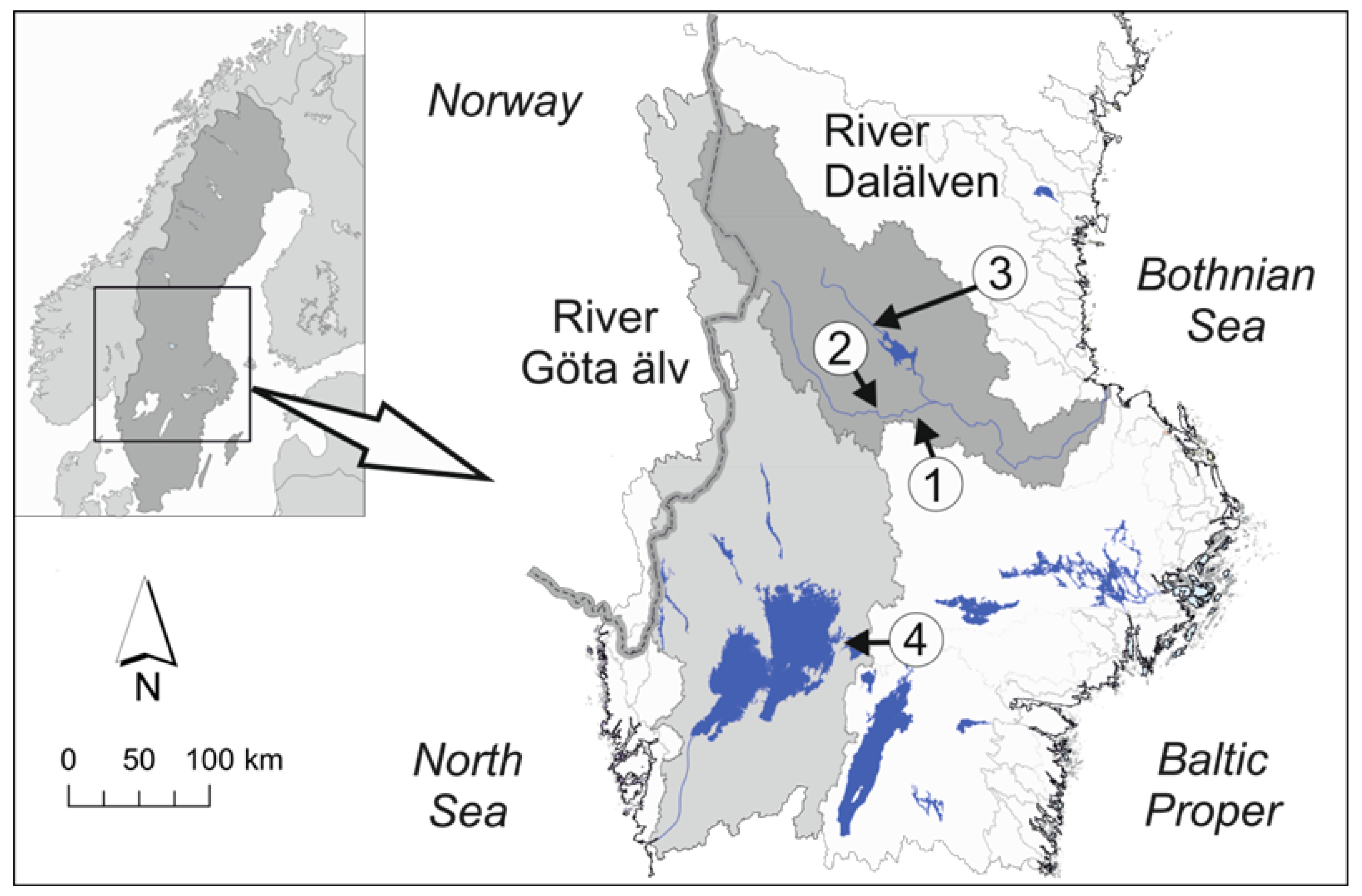

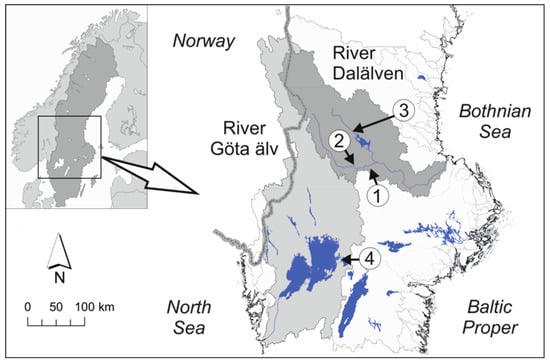

In this study, we conducted an infestation experiment using FPM from the River Tansån, situated in the River Dalälven catchment, and three brown trout strains from the same catchment (hereafter termed “local catchment”) and one trout strain from a different catchment, the River Göta älv catchment (hereafter termed “foreign catchment”) (Figure 1). The trout strains that we used were: (1) a local sympatric wild strain (River Tansån), (2) a local allopatric wild strain (River Trettonjällbäcken from the River Dalälven catchment, situated near the fishway), (3) a local allopatric hatchery strain (Lake Siljan, used for compensatory stocking within the River Dalälven catchment), and (4) a foreign allopatric hatchery strain from a different catchment (River Gullspångsälven in the River Göta älv catchment).

Figure 1.

Map of the fish origins in: (1) River Tansån, (2) River Trettonjällbäcken, and (3) Lake Siljan in the River Dalälven catchment (dark grey), and in River Gullspångsälven in the River Göta älv catchment (light grey) (4).

Adult FPMs were monitored for gravidity in River Tansån during July and August 2014. The mussels were carefully opened approximately 1 cm using specially manufactured tongs, and their marsupia were visually inspected for glochidia [30]. When the mussels were classified as gravid, ten mussels were transported to the aquaria facility at Karlstad University, where they were placed in 10-L aerated containers. Once the glochidia had been released, the adult mussels were returned to their native stream.

Wild young-of-the-year (YOY) brown trout from River Tansån (53.9 ± 0.96 (SD) mm; 1.30 ± 0.12 (SD) gram) and River Trettonjällbäcken (48.8 ± 2.92 (SD) mm; 1.07 ± 0.22 (SD) gram) were caught by electrofishing (LUGAB, L1000, Tumba, Sweden) in mid-August 2014. The Sävenfors hatchery provided the two hatchery strains (YOY) from Lake Siljan (68.0 ± 3.37 (SD) mm; 3.59 ± 0.48 (SD) gram) and River Gullspångsälven (56.5 ± 4.19 (SD) mm; 1.71 ± 0.41 (SD) gram). Every individual trout was considered to be in a healthy condition after ocular inspection (alert and no obvious diseases). All trout were brought to the aquarium facility at Karlstad University, where they were put in holding tanks with external filters (EHEIM 2215 filter, Deizisau, Germany). After the experiments were completed, the fish were euthanized according to the requirements of the ethical permits.

2.2. Study Design and Data Analyses

On 5 September, glochidia larvae from four mussels were collected. Larval viability, indicated by valve closure, was tested by adding a grain of salt to glochidia subsamples. A well-mixed suspension of glochidia from the four FPM individuals was used during the trout infestation on 5–6 September 2014. The glochidia were put in 10 L containers at a concentration of 25,000 larvae L−1, whereupon fish were carefully put in the containers and were exposed to the suspension for 45 min. After infestation, each trout strain was kept at the same densities (25 individuals per aquarium) in separate aquaria (local sympatric wild strain and local allopatric wild strain—100 trout individuals equally divided in four 100 L aquaria; local allopatric hatchery strain and foreign allopatric hatchery strain—200 trout individuals equally divided in eight 100 L aquaria). The water was constantly filtered (EHEIM 2215 filter, Deizisau, Germany), and approximately half of the water in the aquaria was replaced with fresh water twice a week. Fish were fed with commercial fish food pellets twice a week (2% of body weight) and with red chironomids once a week (10% of body weight). Water temperature was measured four times a week (except for one week when temperature was measured twice) and was 17.2 ± 0.85 °C for the entire study period. The sum of degree-days did not differ between the fish strains (X2(3) = 2.51, p = 0.47). Dead fish were recorded and removed from the tanks. Pump failure, causing oxygen depletion in two aquaria, was responsible for 35% (local allopatric wild strain, n = 6) and 17% (foreign allopatric hatchery strain, n = 9) of the mortalities in the hatchery strains, whereas a low survival rate of the local sympatric wild strain could not be explained by any observed technical problems.

Fish were removed from the tanks and exposed to an overdose of Benzocaine 1, 3, and 40 days post-infestation (dpi). Each fish strain was removed from four to seven aquaria per strain after 1 dpi and 3 dpi (foreign allopatric hatchery strain (n = 21 from seven aquaria), local allopatric hatchery strain (n = 20 from five aquaria), local allopatric wild strain (n = 21 from four aquaria), and local sympatric wild strain (n = 18 from four aquaria)), and from three to six aquaria after 40 dpi (foreign allopatric hatchery strain (n = 28 from six aquaria), local allopatric hatchery strain (n = 28 from five aquaria), local allopatric wild strain (n = 28 from four aquaria) and local sympatric wild strain (n = 4 from three aquaria)). The sum of degree-days was 654 ± 16 °C at 40 dpi, which places the larvae at a developmental stage between the early sloughing of glochidia by unsuitable hosts [28] and the excystment of juvenile mussels at 1300–3440 degree-days [29]. All fish were weighed (±0.01 g) and measured (±1 mm) and immediately stored in 70% ethanol before examination of the gills. The condition factor of the fish was calculated as C = w*100/l^3, where w = weight in grams and l = length in cm.

Fish from the local allopatric hatchery strain weighed significantly more (X2(3) = 41.65, p < 0.0001; Dunn test, p < 0.0001) than fish from the local sympatric wild strain, local allopatric wild strain (Dunn test, p < 0.0001), and foreign allopatric hatchery strain (Dunn test, p = 0.007). The foreign allopatric hatchery strain also weighed more than fish from the local allopatric wild strain (Dunn test, p = 0.034). Fish from the local allopatric hatchery strain had a significantly higher condition factor (ANOVA F3,79 = 37.69, p < 0.0001; Tukey, p < 0.0001) than fish from the other strains. Fish from the foreign allopatric hatchery strain had a significantly higher condition factor than fish from the local sympatric wild strain (Tukey, p = 0.033).

All four gill arches on the right side of each fish were removed using tweezers and scissors, and the number of glochidia was counted under a stereo microscope (Nikon, SMZ 745T, Tokyo, Japan). As an earlier study has shown that the number of glochidia does not differ significantly between gill arches on the left and right side [29], this number was multiplied by two to estimate the total number of glochidia per individual fish. However, if the number of glochidia on the right side of the fish was zero, the gill arches on the left side of the fish were also examined. The prevalence of glochidia infestation on each brown trout strain was calculated by dividing the number of infested fish by the total number of fish.

Data for the sampling occasions at 1 dpi and 3 dpi were pooled together and are hereafter referred to as “early sampling occasion”, whereas the sampling at 40 dpi is hereafter referred to as “late sampling occasion”. A chi-square (χ2) test was used to test if there was a difference in prevalence between the fish strains at the late sampling occasion. Due to differences in individual fish size, the weight-normalized glochidia abundance, i.e., the number of glochidia larvae per gram of fish, was calculated. The residuals were not normally distributed for glochidia per fish or for weight-normalized glochidia abundance (Kolmogorov–-Smirnov tests, p < 0.002 and p < 0.003, respectively), and there was also a difference in the number of replicates within and between the early and the late sampling occasions. The differences in the number of glochidia per fish and the weight-normalized glochidia abundance between brown trout strains were thus analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis tests at the early and the late sampling occasions, respectively, with “brown trout strain” as a factor. Correlations between glochidia abundance and fish weight and condition factors were tested using Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient.

To study differences in glochidia size among the fish strains, the diameter of encapsulated larvae was measured (±1 µm) at the late sampling occasion. Glochidia were examined at 50× magnification with a stereo microscope (Nikon, SMZ 745T, Tokyo, Japan) connected to a computer using the software INFINITY ANALYZE (Lumenera Corporation, Ottawa, ON, Canada). Gills from four to ten fish individuals from each strain were examined, and the number of glochidia (n = 288) was measured at the late sampling occasion. The residuals for the mean glochidia size per individual fish were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–-Smirnov tests, p < 0.001). Differences in glochidia size between the four brown trout strains were thus analyzed using a Kruskal–-Wallis test. Lastly, relationships between glochidia size as a proxy for glochidia growth, and fish weight and glochidia abundance at the late sampling occasion, respectively, were tested using Spearman rank correlations. Statistical testing of fish from the local sympatric wild strain was omitted in these two correlations due to a few surviving fish having encapsulated glochidia at the late sampling occasion. IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0.0.1 was used for conducting statistical tests.

3. Results

3.1. Glochidia Abundance

All inspected brown trout individuals were infested with glochidia during the early sampling occasion. The prevalence of glochidia infestation was 79% for the foreign allopatric hatchery strain, 54% for the local allopatric hatchery strain, 64% for the local allopatric wild strain, and 67% for the local sympatric wild strain at the late sampling occasion. There was no effect of fish origin on prevalence of glochidia at the late sampling occasion (X2) = 3.90, df = 3, p = 0.27).

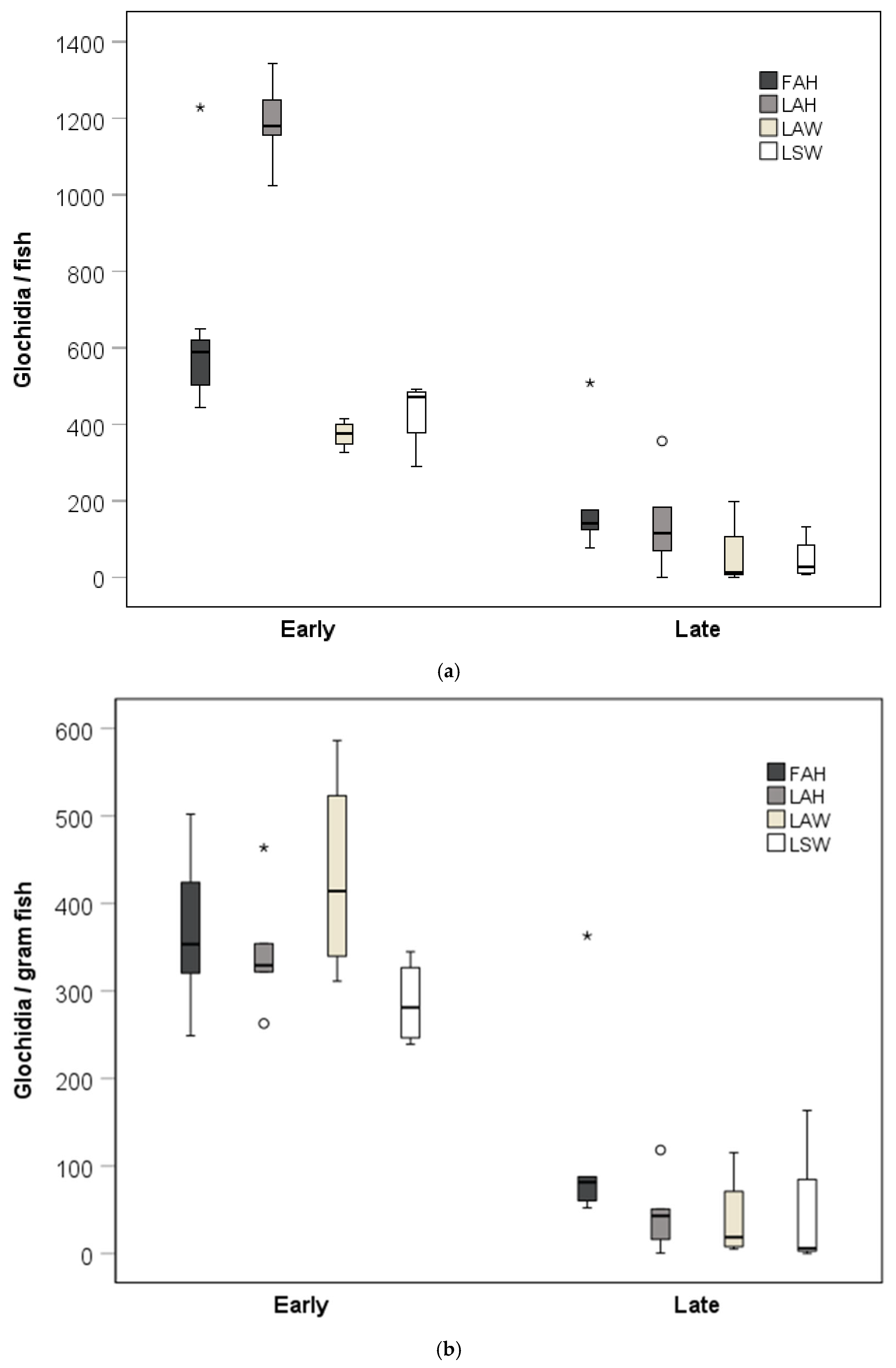

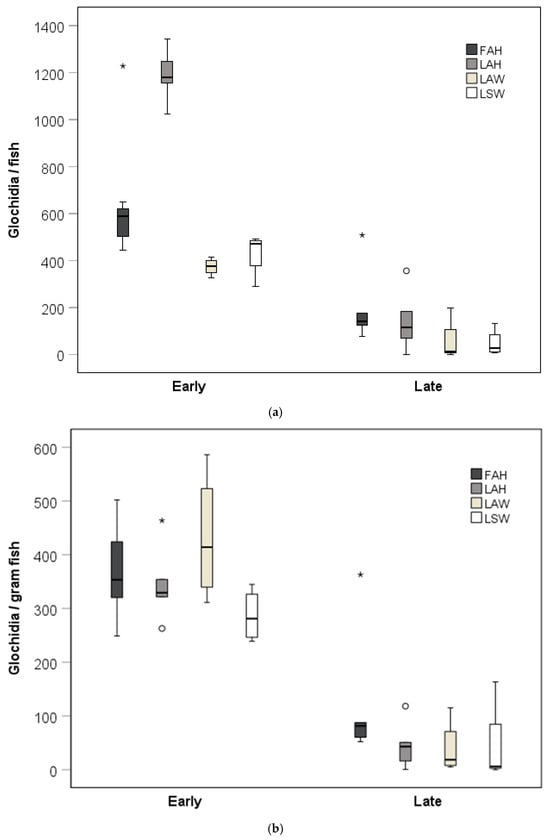

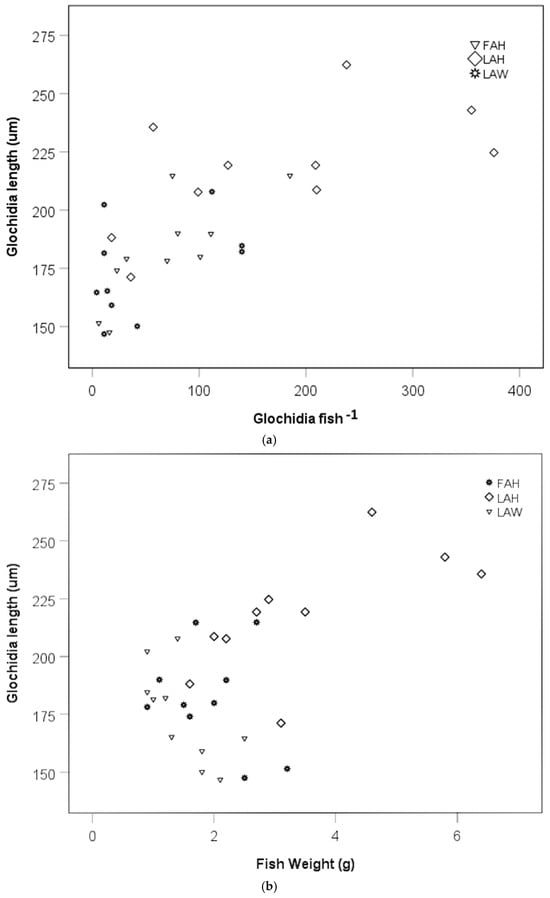

Glochidia abundance per fish was generally higher at the early sampling than in the late sampling. The glochidia abundance per fish was higher for the local allopatric hatchery strain than for the local sympatric wild strain at the early sampling occasion (Kruskal–Wallis test, pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections, p = 0.003; Figure 2a). There was no difference in glochidia abundance per fish between the local allopatric hatchery strain and the foreign allopatric strain at the early sampling occasion (Kruskal–Wallis test, pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections, p = 0.56; Figure 2a), while there appeared to be a difference in glochidia abundance per fish between the local allopatric hatchery strain and the local sympatric hatchery strain (Kruskal–Wallis test, pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections, p = 0.053; Figure 2a). There were no differences in glochidia abundance per fish between the brown trout strains at the late sampling occasions (Kruskal–Wallis test, p > 0.05; Figure 2a). Weight-normalized glochidia abundance was generally higher at the early sampling than in the late sampling. There was, however, no significant effect of fish strain on the weight-normalized glochidia abundance at the early or at the late sampling occasion (Kruskal–Wallis tests, p > 0.05; Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Glochidia abundance per fish and (b) weight-normalized glochidia abundance at the early and the late sampling occasions. Boxes depict the 75th and 25th percentiles, and the vertical lines within each box represent the medians. Circles depict outliers 1.5–3.0 times the interquartile range (IQR), and the asterisks depict outliers > 3.0 IQR. Abbreviations: FAH = foreign allopatric hatchery, LAH = local allopatric hatchery, LAW = local allopatric wild, and LSW = local sympatric wild.

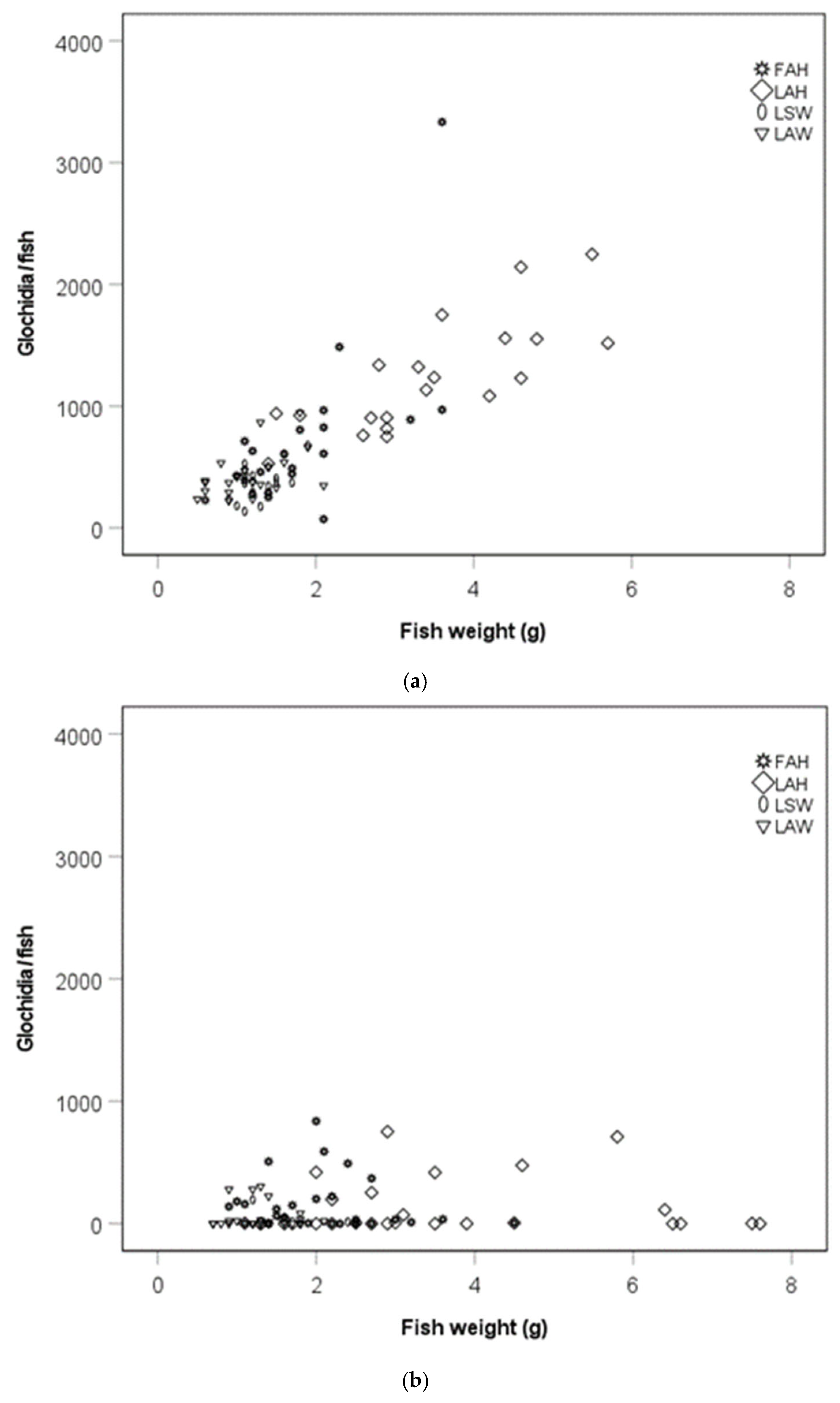

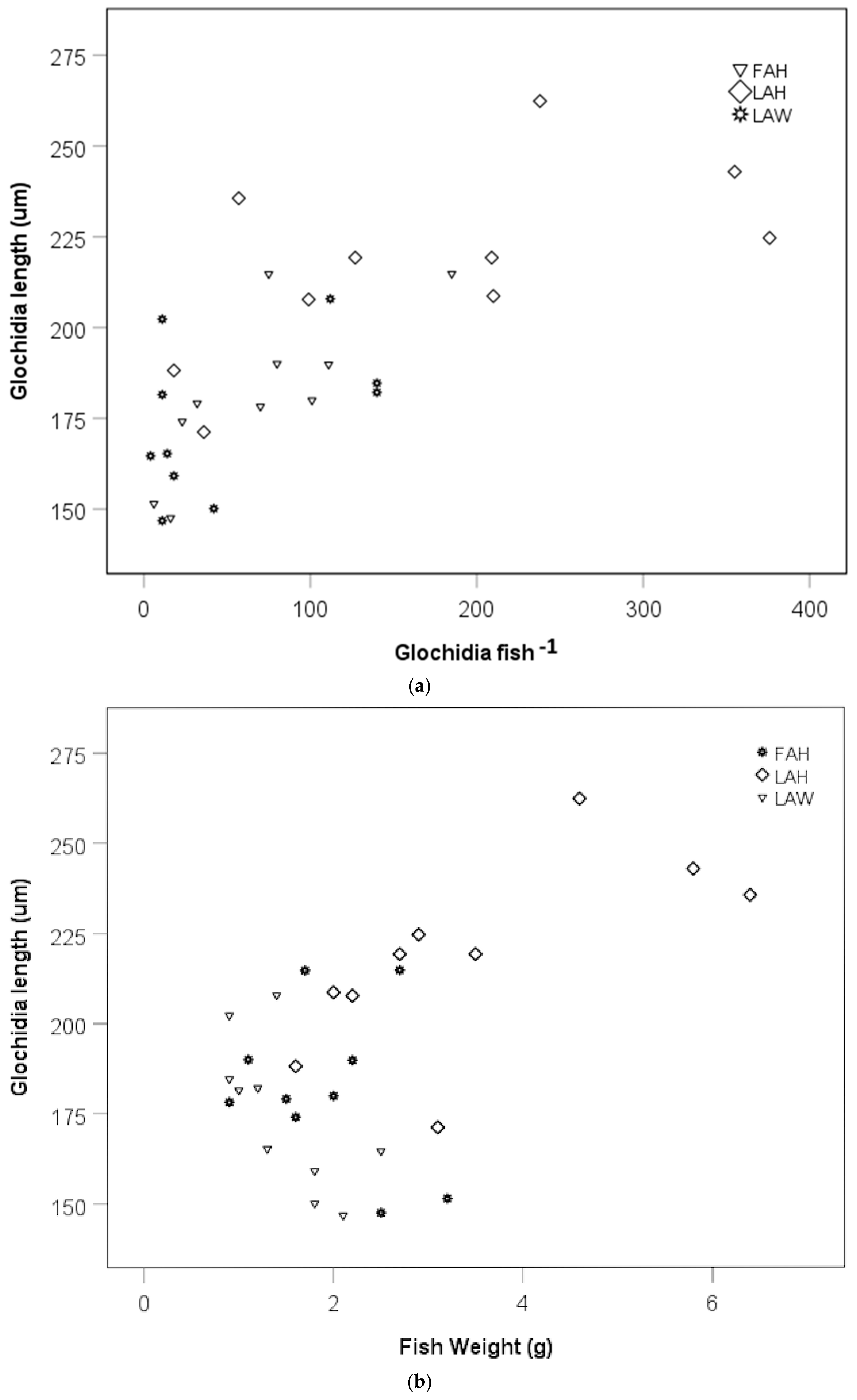

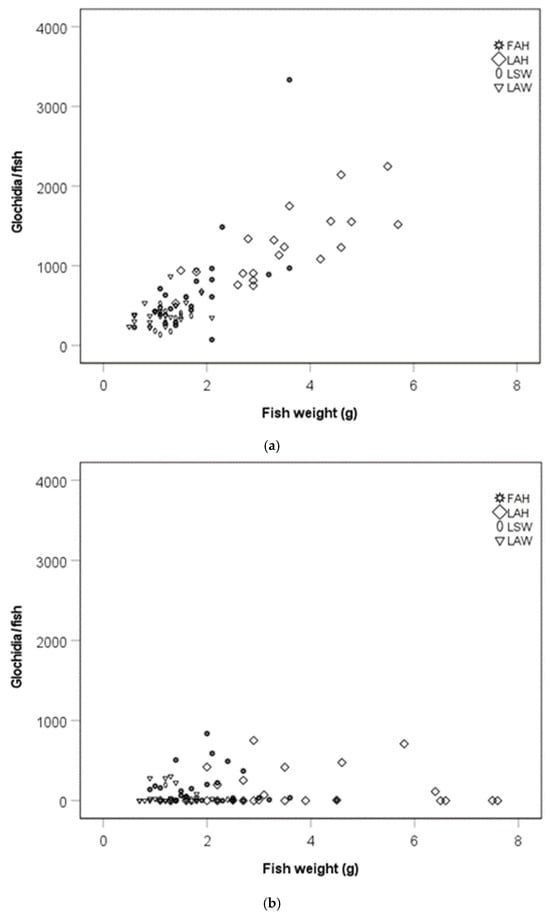

There was a positive association between the glochidia abundance per fish and fish weight (rs = 0.70, p < 0.0001, Figure 3a) and glochidia abundance per fish and condition factor at the early sampling occasion (rs = 0.52, p < 0.0001, Figure 3c). There was no association between glochidia abundance per fish and fish weight (rs = 0.22, p = 0.216, Figure 3b) or fish condition factor (rs = 0.12, p = 0.50; Figure 3d) at the late sampling occasion.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of the number of glochidia per fish and fish weight during (a) the early sampling occasion and (b) the late sampling occasion, and the number of glochidia per fish and fish condition factor during the (c) early sampling occasion and (d) the late sampling occasion. Abbreviations: FAH = foreign allopatric hatchery, LAH = local allopatric hatchery, LAW = local allopatric wild and LSW = local sympatric wild.

3.2. Glochidia Size

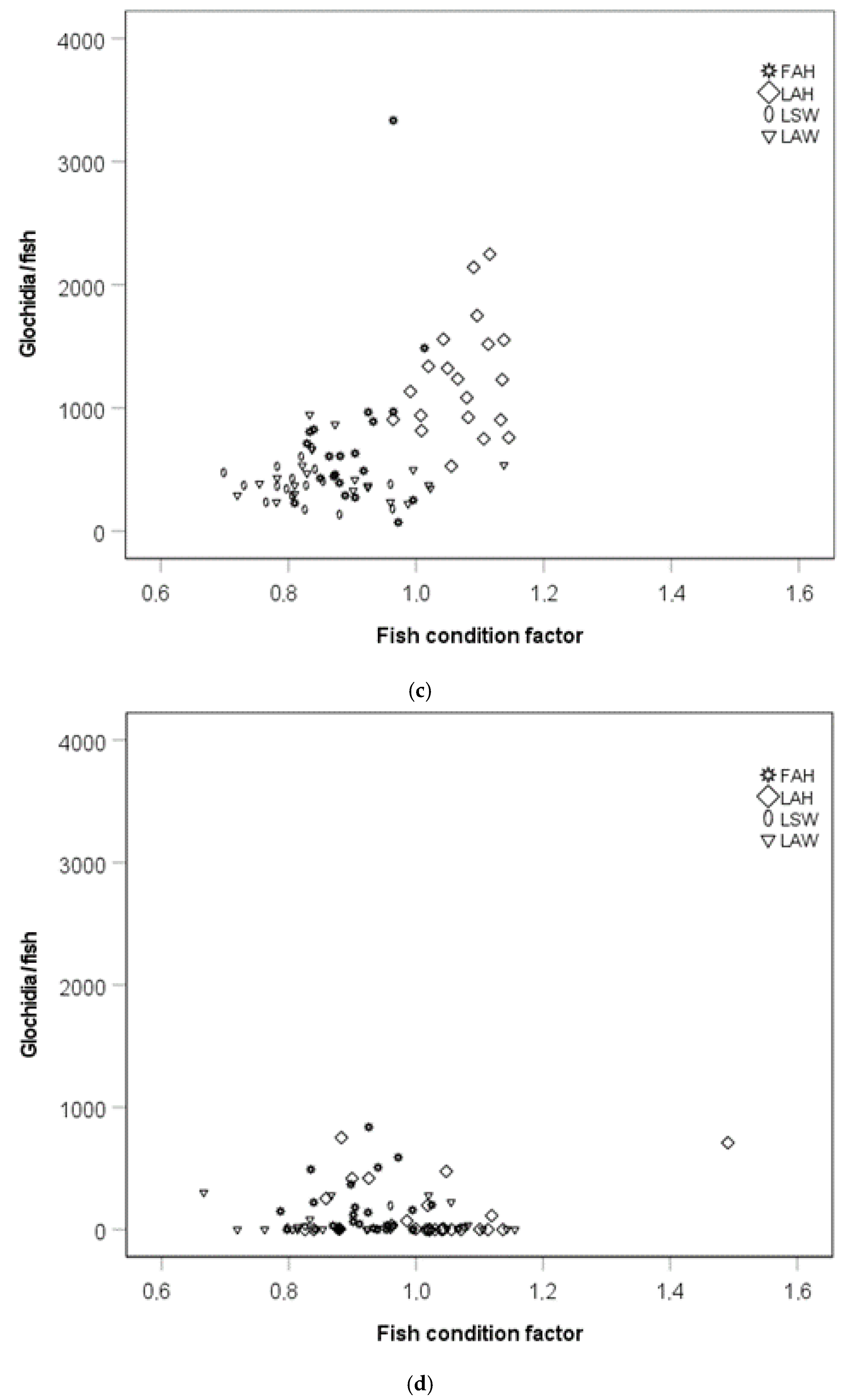

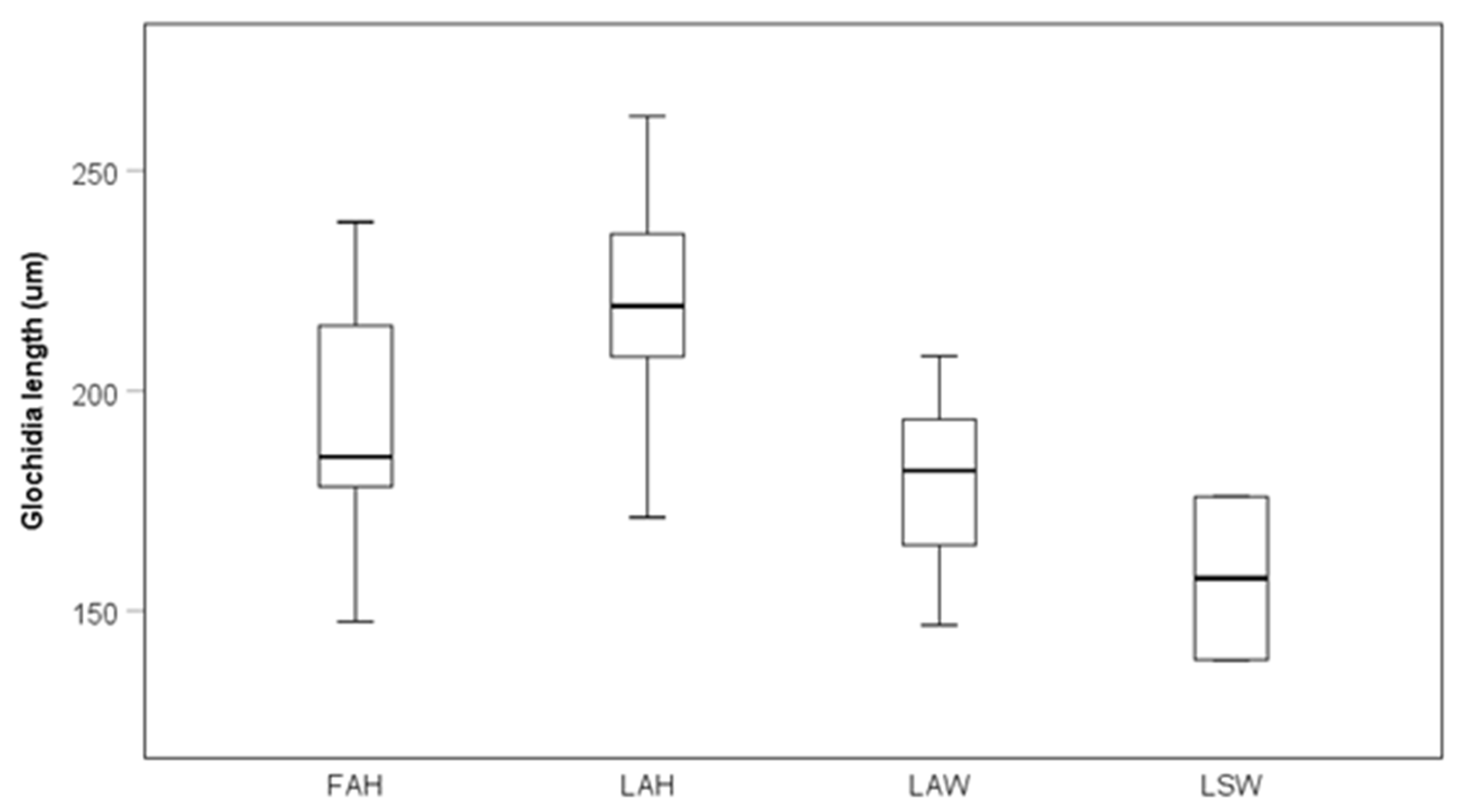

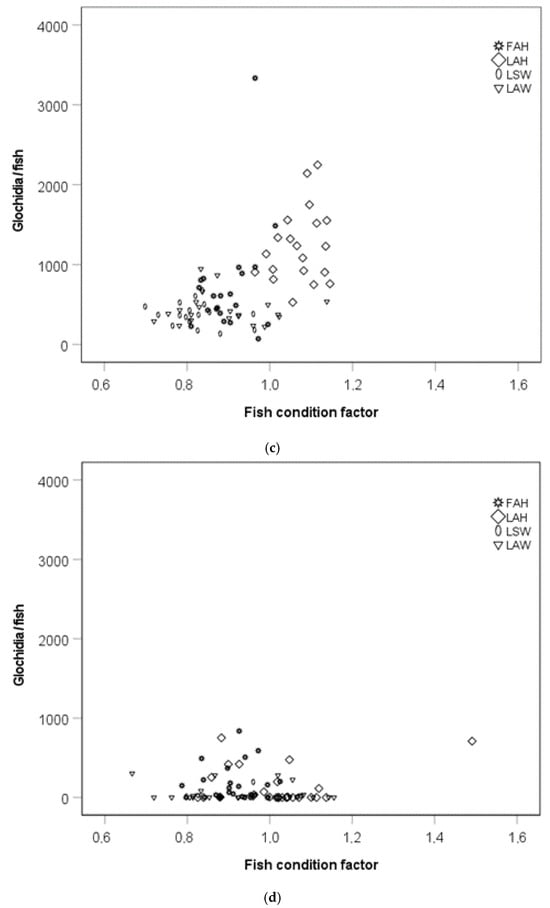

Glochidia on the local allopatric hatchery strain were significantly larger than glochidia on the local allopatric wild strain, while there were no other differences among other strains at the late sampling occasion (Kruskal–Wallis test, pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections, p = 0.047; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Glochidia size on different fish strains after 40 days post infestation. Boxes depict the 75th and 25th percentiles, and the vertical lines within each box represent the medians. Abbreviations: FAH = foreign allopatric hatchery, LAH = local allopatric hatchery, LAW = local allopatric wild and LSW = local sympatric wild. The estimate of glochidia size for LSW at the late sampling is based only on two fish and was therefore excluded from statistical testing.

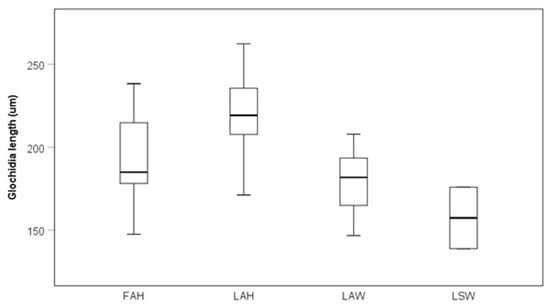

There was a positive relationship between mean glochidia size and glochidia abundance per fish in an analysis including the local allopatric wild strain, the local allopatric hatchery strain, and the foreign allopatric hatchery strain at the late sampling occasion (rs = 0.76, p < 0.0001, Figure 5a). When testing the fish strains separately, there was no relationship between glochidia size and glochidia abundance per fish for the local allopatric wild strain (rs = 0.36, p = 0.311, Figure 5a), but there was a positive relationship between glochidia size and glochidia abundance per fish for the local allopatric hatchery strain (rs = 0.69, p = 0.026, Figure 5a) and the foreign allopatric hatchery strain (rs = 0.87, p = 0.001, Figure 5a). No relationship between mean glochidia size and fish weight could be seen when these three fish strains were included in one analysis (rs = 0.77, p = 0.33, Figure 5b). Separating the fish strains, there was a negative relationship between mean glochidia size and fish weight for the local allopatric wild strain (rs = −0.73, p = 0.018, Figure 5b), a positive relationship between glochidia size and fish weight for the local allopatric hatchery strain (rs = 0.72, p = 0.020, Figure 5b), while there was no relationship between glochidia size and fish weight for the foreign allopatric hatchery strain (rs = −0.91, p = 0.80) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of glochidia size at the late sampling and (a) glochidia abundance per fish and (b) fish weight. Abbreviations: FAH = foreign allopatric hatchery, LAH = local allopatric hatchery, and LAW = local allopatric wild.

4. Discussion

Our study provides information on the host suitability of four brown trout strains for FPM larvae, with implications for mussel conservation. Both wild and hatchery trout strains were successfully infested with glochidia, and no difference in prevalence of glochidia infestation could be seen at the early sampling occasion. The natural host of the studied mussel strain, i.e., the local sympatric wild trout strain, had lower glochidia infestation at the early sampling occasion and suffered from mortalities shortly after. No difference in glochidia abundance could be seen between the fish strains at the late sampling occasion, suggesting that local wild trout strains with a historical overlap with FPM populations can support mussel introductions. Moreover, our results suggest that local and foreign hatchery strains may be used to supplement FPM streams where local wild trout populations have disappeared. The largest glochidia were found on the local allopatric hatchery strain, indicating that this strain is a suitable host for the River Tansån mussels. In addition, these large hatchery fishes had high loads of large-sized glochidia, which leads us to believe that fish size is a factor to select for to increase juvenile mussel production and survival. Our results have implications for management strategies, such as when planning to introduce mussels or trout into streams and when culturing juvenile mussels for reintroduction.

4.1. Glochidia Abundance

We found no differences in weight-normalized glochidia abundance among the trout strains at the early or at the late sampling occasion, indicating that suitability did not differ among the strains. The local allopatric hatchery strain had more glochidia per fish than the local sympatric wild strain at the early sampling occasion. Fish from the local allopatric hatchery strain were significantly larger than fish from the other strains, and a positive relationship between fish size and early glochidia abundance has also been found in previous studies [29,31,32]. This has previously been explained by the fact that large fish have a larger gill surface area and a higher ventilation rate, which results in higher glochidia attachments [11]. Larval infestation decreased over time on all trout strains, as reported for suitable fish hosts in previous field [31] and laboratory studies [28]. The positive relationship between host body size and glochidia abundance per fish was transitory, as no significant effect of body size could be found at the late sampling, possibly caused by a stronger immune response by larger fish or by a reduced growth caused by the glochidia infestations [31,32,33].

4.2. Glochidia Size

Glochidia were larger on the local allopatric hatchery strain than on the local allopatric wild strain. This indicates that the number of juvenile recruits will be highest from the local allopatric hatchery strain, at least under laboratory conditions, as shell length has been suggested to be a good indicator of overwinter survival for juvenile mussels [34,35]. The higher growth rate may be a result of the higher condition factor of the local allopatric hatchery strain, where the glochidia larvae may benefit from a host with a high nutritional supply [28]. There was also a positive relationship between fish weight and glochidia size for this strain, indicating that large fish from this hatchery strain represent functional hosts. In contrast, wild fish in mussel distribution areas, just like the local allopatric wild strain in our study, have a history of mussel infestations and may have a well-developed immune defense against glochidia of this species, which may be one reason for the negative relationship between fish size and glochidia size of the wild fish.

4.3. Management Implications

Our results show that FPM infestation was successful for the four brown trout strains tested, including one hatchery strain originating from a foreign catchment, indicating that foreign hatchery strains could be used as a supplement in FPM streams where local brown trout populations have been depleted. This pattern of suitability for glochidia infestation could also be strain-specific and should hence be interpreted with caution, especially since we tested only one foreign strain on one mussel strain. Glochidia abundance was also generally independent of fish size for late glochidia infestation. The utility of screening for large fish for artificial mussel infestation and propagation to attain a high number of juvenile mussels thus seems uncertain. Glochidia did, however, grow faster on large fish, especially on fish from the local allopatric hatchery strain, potentially with higher chances of over-winter survival. The opposite trend was found for infested fish from the local allopatric wild strain. It is therefore recommended that infestation tests using different fish strains are performed in an effort to find a suitable host before production-scale mussel propagation begins.

The low survival of the local wild sympatric brown trout strain is puzzling in terms of adaptation to host–parasite interactions, such that this strain should survive sympatric mussel infestations [28,36,37]. It is more likely that this brown trout strain suffered from the laboratory environment (i.e., water quality or food quality), even if this does not explain the higher survival of the local wild allopatric brown trout strain. The low survival of the local wild sympatric brown trout strain may also be caused by diseases, even if we did not notice any differences in health conditions compared to the other strains.

Fish from the hatchery strains with high glochidia abundance at the late sampling occasion were more likely to have larger glochidia, indicating that the most suitable host fish in our study not only carried more mussels, but the mussels also grew faster on these fish. Using individuals from hatchery strains with many fast-growing glochidia may thus be a cost-effective alternative for mussel propagation. Previous studies have shown, however, that high glochidia abundance might have deleterious effects on the host’s respiratory performance [32] and drift feeding efficiency [36,37]. Attaining a high number of glochidia per fish might therefore not always result in the highest juvenile mussel production. Finding an intermediate glochidia load suitable for both parasite and host may instead be the goal. Previous studies have reached different conclusions regarding patterns of local adaptation between the FPM and their sympatric host fish strain [5,28,38,39]. Fish from the local sympatric wild strain in this study did not cope well in the laboratory environment. As a result, artificial infestation of fish from this specific strain cannot be recommended based on this single experiment. High numbers of brown trout from wild strains tolerant to artificial infestations and adapted to FPM and to being held in a hatchery system seem, however, to be needed to produce juvenile mussels through infested fish or juveniles reared under laboratory conditions. It may thus not be sustainable to use fish from FPM streams with weak stocks of trout, especially as only about 5–10% of the infested glochidia will metamorphose [40,41], and the survival of juvenile mussels is low [14,40].

The hatchery trout and one wild trout strain had a relatively high survival in the aquaria environment in this study. Hatchery-raised strains are often easy to attain in high numbers, while wild strains are often found in relatively low numbers. If hatchery trout are used for compensatory stocking, one option is to infest them with FPM larvae before they are released into streams. Currently, fish from the local allopatric hatchery strain are used for compensatory stocking near the fishway, and as larvae grow fast on the fish from this strain, they may de facto constitute a functioning host for FPM from Tansån. This speculation should be treated with care, especially since this allopatric strain does not have a history of local adaptation with the FPM from Tansån. Another potential problem that needs to be addressed in future studies is the survival of these hatchery-raised fish in the field, since the survival of hatchery fish released into the wild is generally low [42]. Thus, since juvenile mussels are released from the host fish after ten to twelve months, low winter survival of the fish may result in low mussel recruitment. In addition, stocking of hatchery fish is problematic, and several studies have shown negative effects on wild populations caused by displacement, competition, increased predation, and genetic contamination [43,44]. The local wild allopatric trout strain in our study was also found to be suitable for the FPM. Infesting this strain or letting them be naturally infested by introduced adult mussels presents options that do not involve continued introductions of hatchery fish. On the other hand, hatchery fish could potentially be used for large-scale juvenile mussel breeding, given their potential to be attained in high numbers. Cultured juvenile mussels can then be released into streams to strengthen threatened mussel populations and present an option where hatchery fish are not reintroduced, while the mussel populations could still be strengthened. Testing all three methods, i.e., releasing mussel-infested fish, juvenile mussels, or adult gravid mussels, may be worthwhile within an adaptive management approach of assessing which method(s) work best in general or in specific streams [45].

Author Contributions

S.G., O.C. and M.Ö. conceived the initial study idea. S.G. primarily collected the data, supported by O.C. and M.Ö. S.G. led the writing of the manuscript, supported by O.C. and M.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Fortum Environmental Fund. Projects that receive funding are approved by the NGO Swedish Society for Nature Conservation (SSNC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The investigations were carried out with ethical permissions from the Animal Ethical Board of Sweden (Dnr 88–2013 and Dnr 85–2013).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sävenfors Hatchery, Särna Hatchery, the County Administrative Board of Dalarna, Jenny Freitt, Lars Dahlström, Tina Petersson, and Sven-Erik Fagrell for assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Griffith, B.; Scott, J.M.; Carpenter, J.W.; Reed, C. Translocation as a species conservation tool: Status and strategy. Science 1989, 245, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN/SSC. Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations (Version 1.0); IUCN Species Survival Commission: Gland, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Geist, J. Strategies for the conservation of endangered freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera L.): A synthesis of conservation genetics and ecology. Hydrobiologia 2010, 644, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, J.K.; Luhta, P.L.; Moilanen, E.; Oulasvirta, P.; Turunen, J.; Taskinen, J. Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) differ in their suitability as hosts for the endangered freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) in northern Fennoscandian rivers. Freshw. Biol. 2017, 62, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskinen, J.; Salonen, J.K. The endangered freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera shows adaptation to a local salmonid host in Finland. Freshw. Biol. 2022, 67, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.D.; Braun, D.P.; Mendelson, M.A.; Master, L.L. Threats to imperiled freshwater fauna. Conserv. Biol. 1997, 11, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österling, E.M.; Söderberg, H. Sea-trout habitat fragmentation affects threatened freshwater pearl mussel. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 186, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L. Freshwater Mussel Ecology: A Multifactor Approach to Distribution and Abundance; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, C.C. Biodiversity losses and ecosystem function in freshwaters: Emerging conclusions and research directions. BioScience 2010, 60, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieritz, A.; Sousa, R.; Aldridge, D.C.; Douda, K.; Esteves, E.; Ferreira-Rodríguez, N.; Mageroy, J.H.; Nizzoli, D.; Osterling, M.; Reis, J.; et al. A global synthesis of ecosystem services provided and disrupted by freshwater bivalve molluscs. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1967–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Williams, J. The reproductive biology of the freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera (Linn.) in Scotland. I: Field studies. Arch. für Hydrobiol. 1984, 99, 405–422. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen, J.K.; Marjomäki, T.T.; Taskinen, J. An alien fish threatens an endangered parasitic bivalve: The relationship between brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) and freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) in northern Europe. Aquat. Conserv. 2016, 26, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, P.J.; Cooksley, S.L.; Geist, J.; Killeen, I.J.; Moorkens, E.A.; Sime, I. Developing a standard approach for monitoring freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) populations in European rivers. Aquat. Conserv. 2019, 29, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, N.; Keys, A.; Preston, J.S.; Moorkens, E.; Roberts, D.; Wilson, C.D. Conservation status and reproduction of the critically endangered freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) in Northern Ireland. Aquat. Conserv. 2013, 23, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, B.L.; Karlsson, J.; Österling, M.E. Recruitment of the threatened mussel Margaritifera margaritifera in relation to mussel population size, mussel density and host density. Aquat. Conserv. 2012, 22, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, L.; Cosgrove, P. The decline of migratory salmonid stocks: A new threat to pearl mussels in Scotland. Freshw. Forum 2001, 15, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, I.Y. Overfishing in the Baltic Sea basin in Russia, its impact on the pearl mussel, and possibilities for the conservation of riverine ecosystems in conditions of high anthropogenic pressure. Biol. Bull. 2017, 44, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt-Holm, P.; Peter, A.; Segner, H. Decline of fish catch in Switzerland. Aquat. Sci. 2002, 64, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Walker, A. Characteristics of the sea trout Salmo trutta L. stock collapse in the River Ewe (Wester Ross, Scotland) in 1988–2001. In Sea Trout: Biology, Conservation and Management; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gargan, P.; Poole, W.; Forde, G. A review of the status of Irish sea trout stocks. In Sea Trout: Biology, Conservation and Management; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, D.L.; Behnke, R.J.; Gephard, S.R.; McCormick, S.D.; Reeves, G.H. Why aren’t there more Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1998, 55, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulet, N.; Beaulaton, L.; Dembski, S. Time trends in fish populations in metropolitan France: Insights from national monitoring data. J. Fish Biol. 2011, 79, 1436–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorstad, E.B.; Todd, C.D.; Uglem, I.; Bjørn, P.A.; Gargan, P.G.; Vollset, K.W.; Halttunen, E.; Kålås, S.; Berg, M.; Finstad, B. Effects of salmon lice Lepeophtheirus salmonis on wild sea trout Salmo trutta: A literature review. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2015, 7, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowx, I.G. An appraisal of stocking strategies in the light of developing country constraints. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 1999, 6, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, G.A.; Pearsons, T.N.; Leider, S.A. Behavioral interactions among hatchery-reared steelhead smolts and wild Oncorhynchus mykiss in natural streams. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 1999, 19, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, H.; Cooper, B.; Blouin, M.S. Genetic effects of captive breeding cause a rapid, cumulative fitness decline in the wild. Science 2007, 318, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.; Loeschcke, V. Effects of releasing hatchery-reared brown trout to wild trout populations. In Conservation Genetics; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 1994; Volume 68, pp. 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Österling, M.E.; Larsen, B.M. Impact of origin and condition of host fish (Salmo trutta) on parasitic larvae of Margaritifera margaritifera. Aquat. Conserv. 2013, 23, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeubert, J.E.; Denic, M.; Gum, B.; Lange, M.; Geist, J. Suitability of different salmonid strains as hosts for the endangered freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera L.). Aquat. Conserv. 2010, 20, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österling, E.M.; Greenberg, L.A.; Arvidsson, B.L. Relationship of biotic and abiotic factors to recruitment patterns in Margaritifera margaritifera. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, L.C.; Young, M.R. Freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) glochidiosis in wild and farmed salmonid stocks in Scotland. Hydrobiologia 2001, 445, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.R.; Taylor, J.; De Leaniz, C.G. Does the parasitic freshwater pearl mussel M. margaritifera harm its host? Hydrobiologia 2014, 735, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.M.R.; Marjomäki, T.M.; Taskinen, J. Effect of glochidia infection on growth of fish: Freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera and brown trout Salmo trutta. Hydrobiologia 2019, 848, 3179–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denic, M.; Taeubert, J.E.; Lange, M.; Thielen, F.; Scheder, C.; Gumpinger, C.; Geist, J. Influence of stock origin and environmental conditions on the survival and growth of juvenile freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera) in a cross-exposure experiment. Limnologica 2015, 50, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, J.; Jensen, K.H.; Jakobsen, P.J.; Geist, J. Duration of the parasitic phase determines subsequent performance in juvenile freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera). Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österling, E.M.; Ferm, J.; Piccolo, J.J. Parasitic freshwater pearl mussel larvae reduce the drift-feeding rate of juvenile brown trout. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2014, 97, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, S.L.; Watz, J.; Nilsson, P.A.; Österling, M. Effects of parasitic freshwater mussels on their host fishes: A review. Parasitology 2022, 149, 1958–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.; Vogel, C. The parasitic stage of the freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera L.): I. Host response to glochidiosis. Arch. für Hydrobiol. 1987, 76, 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Taeubert, J.E.; Gum, B.; Geist, J. Variable development and excystment of freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera L.) at constant temperature. Limnologica 2013, 43, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Williams, J. The reproductive biology of the freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera (Linn.) in Scotland. II: Laboratory studies. Arch. Für Hydrobiol. 1984, 100, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, L.C.; Young, M.R. Timing of spawning and glochidial release in Scottish freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) populations. Freshw. Biol. 2003, 48, 2107–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einum, S.; Fleming, I. Implications of stocking: Ecological interactions between wild and released salmonids. Nord. J. Freshw. Res. 2001, 75, 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kostow, K. Factors that contribute to the ecological risks of salmon and steelhead hatchery programs and some mitigating strategies. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2009, 19, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenbichler, R.; Rubin, S. Genetic changes from artificial propagation of Pacific salmon affect the productivity and viability of supplemented populations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1999, 56, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.S.; Jones, J.W.; Butler, R.S.; Hallerman, E.M. Restoring the endangered oyster mussel (Epioblasma capsaeformis) to the upper Clinch River, Virginia: An evaluation of population restoration techniques. Restor. Ecol. 2015, 23, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.