Abstract

Understanding the genetic diversity and structure of regional cacao and its close relatives is essential for strengthening conservation strategies and enhancing the resilience of Amazonian agroforestry systems. This study evaluated the genetic diversity, population structure, and varietal relationships of 48 sexually derived regional accessions of Theobroma cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor with desirable morpho-agronomic traits, together with eight universal T. cacao reference clones, all cultivated in farmer-managed agroforests of the northwestern Colombian Amazon, using a panel of 15 SSR markers. The loci exhibited substantial allelic richness (mean Na = 8.53) and consistently high expected heterozygosity (Hexp = 0.74), with numerous private alleles indicating species- and lineage-specific divergence. Bayesian clustering, ΔK inference, and minimum spanning networks identified four genetically coherent subpopulations corresponding to the three species and a distinct lineage within T. cacao, strongly aligned with the discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC) results. Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) revealed that most genetic variation occurred among subpopulations (56.68%), while pairwise FST (Wright’s fixation index) values confirmed strong interspecific differentiation and significant divergence within T. cacao. No isolation-by-distance pattern was detected. These findings demonstrate that regional Theobroma germplasm maintained in smallholder agroforests constitutes a valuable reservoir of genetic diversity that complements universal reference clones. By documenting species-level divergence and lineage-specific variation, this study supports the integration of farmer-managed genetic resources into conservation planning and highlights their importance for the long-term resilience of Amazonian cacao-based agroforestry landscapes.

1. Introduction

The Amazon Basin is widely recognized as the center of origin and diversification of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) [1], one of the world’s most important tropical perennial crops due to its ecological and cultural relevance and its extensive use in the food (chocolate), cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries [2,3]. During the 2023–2024 period, global cacao production ranged between 4.4 and 4.8 million tons of beans, while in Colombia, production exceeded 50,000 tons, with a planted area of 190,800 hectares in 2023 [4].

Although regions such as the Colombian Amazon are not among the country’s main cacao-producing areas, their cultivated area increased by more than 40% between 2015 and 2019, driven by the growing global demand for fine-flavor, organic, and deforestation-free cacao [5].

The genus Theobroma comprises around twenty-two species, nine of which are native to the Amazon region. Among them, T. cacao, T. grandiflorum (Willd. ex Spreng.) K. Schum., and T. bicolor Humb. & Bonpl. are of particular interest due to their ecological and economic potential [6,7]. While T. cacao is cultivated mainly for chocolate production, T. grandiflorum (copoazu) and T. bicolor (bacao) are traditionally managed by Amazonian communities for their edible pulp, seeds, and multiple local uses [7,8]. These species share close ecological and genetic relationships, making them valuable for developing tools and criteria to guide the selection and improvement of materials with potential for enriching and strengthening the resilience of Amazonian agroforestry systems [6,7]. Such resilience is reinforced through the preservation of genetic and functional diversity, which enhances adaptive capacity to environmental stress, pests, and diseases, while maintaining productivity and ecosystem stability [9,10].

In Colombia, the extensive cultivation of a limited number of high-yielding clones has reduced cacao’s genetic diversity and sensory quality, increasing its vulnerability to pests and diseases [11,12]. This homogenization threatens both the resilience and cultural richness of cacao agroecosystems. González-Orozco et al. [13] emphasize that Amazonian T. cacao germplasm should be given priority in breeding initiatives, as it contains remnant genetic diversity that is essential for broadening the genetic base of new cultivated cacao. Particularly in the Northwestern Amazon, many regional cacao materials have been propagated by seed for decades and integrated into smallholder agroforestry systems [5]. These sexually derived populations display high phenotypic variability and may represent reservoirs of locally adapted genotypes. However, their varietal identity and genetic diversity remain poorly understood. Within this region, previous studies have described the phenotypic characterization of regional materials exhibiting desirable morpho-agronomic traits—such as fruit shape, seed characteristics, productivity [14], and resistance to frosty pod rot caused by Moniliophthora roreri (Cif.) H.C. Evans, Stalpers, Samson & Benny [15]—but their genetic diversity and structure have not yet been characterized. This gap limits the ability to identify unique regional materials, trace their ancestry, and incorporate them effectively into breeding and conservation programs.

Various studies have mainly aimed to elucidate the varietal identity and genetic diversity of Theobroma germplasm collections representing different geographic origins. Molecular markers such as RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA) and AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism) [6,16], RAMS (Randomly Amplified Microsatellites) [17], SSR (Simple Sequence Repeats) [16,18,19], SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) [12,20,21], and KASP–SNPs (Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR—Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) [22] have been widely used for this purpose. These molecular approaches have been employed to explore genetic diversity, minimize redundancy within germplasm collections, and support the selection of genotypes with desirable agronomic traits [9,12,23].

SSR markers have proven to be powerful tools for assessing diversity and varietal structure in Theobroma species. Their high polymorphism, reproducibility, and codominant inheritance make them ideal for detecting intra- and inter-varietal variation [19,24]. SSR-based analyses have been successfully used to trace the origin of fine-flavor cacao, evaluate germplasm banks, and differentiate cultivars and wild populations across the Neotropics [16,19,25,26]. However, such information remains scarce for regional landrace populations cultivated in the Colombian Amazon, where local selection and sexual hybridization may have generated unique diversity patterns.

To address this gap, this study characterized patterns of genetic diversity and structure in regional Theobroma accessions sampled from farmer-managed agroforestry systems, together with a set of universal T. cacao reference clones included as a comparative framework. This approach provides insights into how farmer-mediated propagation and local selection contribute to maintaining valuable Theobroma diversity within Amazonian agroforestry landscapes.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the genetic diversity, population structure, and varietal relationships of 48 sexually derived regional accessions of T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor with desirable morpho-agronomic traits, along with eight universal T. cacao clones, all cultivated in agroforestry systems of the northwestern Colombian Amazon, using SSR markers.

We hypothesized that these regional accessions harbor high and distinctive levels of genetic diversity and exhibit a detectable population structure—both differentiable from universal T. cacao reference clones—and that such patterns reflect species differentiation, local adaptation, and farmer-mediated selection processes that enhance the resilience of Amazonian agroecosystems.

By revealing the diversity maintained by smallholder farmers and its differentiation from universal cacao clones, this study strengthens the basis for in situ conservation strategies, the use of regional genetic resources, and the long-term resilience of Amazonian agroforestry systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

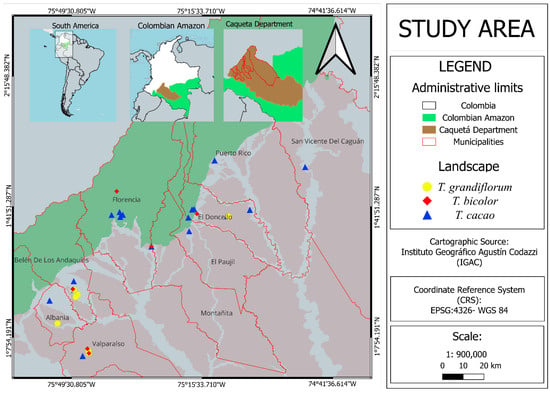

Leaf samples were collected from a total of 56 Theobroma individuals: 48 regional accessions—including 29 of T. cacao, 12 of T. grandiflorum, and 7 of T. bicolor—and 8 widely used commercial T. cacao clones included as reference cultivars (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The regional accessions were sampled from sexually derived trees cultivated in agroforestry systems on farmers’ fields across the municipalities of Belén de los Andaquíes, Albania, Valparaíso, San Vicente del Caguán, Puerto Rico, El Doncello, La Montañita, El Paujil, and Florencia in the department of Caquetá, northwestern Colombian Amazon (Figure 1). These materials were evaluated in previous studies for desirable morpho-agronomic phenotypic traits. The number of pods per tree per year ranged from 17 to 160, the number of seeds per pod ranged from 37 to 51, the seed index ranged from 1.3 to 4.0 g, and the pod index ranged from 5.6 to 19.2. In addition, the incidence of moniliasis caused by M. roreri ranged from 0 to 4.25% [14,15]. All samples were transported to the Biotechnology Laboratory of the Amazonian Institute of Scientific Research (SINCHI) in Bogotá for molecular processing.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of regional accessions of T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor sampled across the department of Caquetá, northwestern Colombian Amazon.

2.2. DNA Extraction

For DNA extraction, we followed the protocol proposed by Martínez [25] based on the FastDNA® Kit (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA), with several modifications to improve DNA quality. Specifically, 100 mg of polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) was added to each Matrix A tube of the kit [27]. Subsequently, 50 mg of dried leaf tissue and an additional ¼-inch ceramic bead were incorporated, and samples were homogenized in a FastPrep®-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals) at 5.0 m/s for 10 s. The remaining steps of the extraction followed the standard kit protocol. After transferring the filtrate to a new capture tube, samples were air-dried for 3 h to prevent alcohol contamination, and the resulting DNA was resuspended in 100 μL of DES buffer. Extracted DNA was evaluated and quantified on 0.8% agarose gels using the Safe-View® stain (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. SSR Markers

A total of 15 microsatellite (SSR) primer pairs were tested for all regional accessions and reference clones (Table 1). These primers were originally developed by Lanaud et al. [28] and have been widely applied in molecular characterizations of T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor [25,29,30,31,32], which guided their selection for this study.

Table 1.

SSR loci, primer sequences, allele size ranges, and fluorochrome labels used for genotyping the 56 Theobroma accessions.

2.4. PCR Amplification and Fragment Analysis

PCR amplification was performed using fluorescently labeled primers, in which the 5′ end of each forward primer was tagged with one of four fluorochromes (6-FAM, NED, VIC, or PET) (Table 1). Capillary electrophoresis was conducted using automated equipment from the Sequencing and Molecular Analysis Service (SSiGMol) of the National University of Colombia to visualize the amplified fragments.

PCR reactions were prepared following the protocol of Alves et al. [32], in a final volume of 13 μL containing 15 ng genomic DNA, 1× PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.1 μM of each primer, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase per 20 μL reaction.

Amplifications were carried out in a C1000™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) under the following cycling conditions: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min, followed by 10 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 1 min (with a touchdown decrease of 1 °C per cycle), and 72 °C for 1 min. This was followed by 20 additional cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 46 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

Amplified fragments were separated on an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at SSiGMol. Allele calling and fragment sizing were performed in Geneious R7 (v7.2.1, trial version) using the GeneScan™ 600 LIZ® Size Standard (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as the internal molecular weight marker.

2.5. Data Analysis

Genetic diversity parameters for each SSR marker were analyzed using the poppr v.2.9.6 [33] and adegenet v. 2.1.10 [34] packages in R v. 4.3.3 [35]. For every locus, we calculated the number of alleles (Na), expected heterozygosity (Hexp) based on Nei’s unbiased gene diversity estimator, observed heterozygosity (Ho) as the proportion of heterozygous individuals, allelic evenness (E) describing the uniformity of allele-frequency distribution, and the polymorphic information content (PIC).

Population structure was inferred using a Bayesian clustering approach implemented in STRUCTURE v.2.3.4 [36,37]. The analysis was performed using the mixture model with correlated allele frequencies, with the number of subpopulations (K) ranging from 1 to 10. For each K, 20 independent runs were executed with a burn-in period of 100,000 iterations followed by 1,000,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCM) repetitions. The most likely number of genetic clusters was identified using the Evanno ΔK method [36], which evaluates the rate of change in the log probability of the data across successive K values. STRUCTURE output files were processed and visualized using STRUCTURE HARVESTER [38]. To further explore multilocus genetic relationships, a minimum spanning network (MSN) was constructed using Bruvo’s distance [39], a metric specifically designed for microsatellite data and capable of handling differences in allele copy number across loci. The MSN was generated using the poppr v.2.9.6 R package, with edges representing genetic distances and node colors reflecting the cluster assignments inferred by STRUCTURE. Genetic differentiation among the inferred subpopulations was quantified using pairwise FST (Wright’s fixation index) estimates following Weir and Cockerham’s estimator [40], implemented in the hierfstat v.0.5-11 package in R [41]. Statistical significance of FST values was assessed using 999 bootstrap permutations. Genetic diversity within each inferred subpopulation was characterized using multiple multilocus metrics computed in poppr v.2.9.6 R package. These included Na, Hexp, Ho, number of private alleles (Npa), Shannon’s index (H), Stoddart and Taylor’s G, Simpson’s λ, and evenness index (E5). The inbreeding coefficient (Fis) was estimated for each group, and significance was evaluated using 999 permutations. Multilocus linkage disequilibrium was examined through the standardized index of association (d) [42], with significance assessed via 999 random permutations.

Discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC) was performed using the adegenet v2.1.10 R package. The resulting linear discriminants (LDs) were used to visualize the genetic structure among subpopulations and to quantify the proportion of discriminant variance explained by each axis. Partitioning of molecular variance was assessed using a hierarchical Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) implemented in the poppr v.2.9.6 package in R, based on the four subpopulations inferred from the STRUCTURE analysis. Fixation indices (Φ statistics) were calculated for each hierarchical level, and statistical significance was evaluated using 999 permutation tests. Finally, to assess isolation by distance and examine the correlation between genetic and geographic distances among Theobroma accessions, a Mantel test was performed in GENALEX 6.5 [43]. The analysis was conducted using linear genetic distances and a randomization procedure with 10,000 permutations to obtain the p-value.

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity and Allelic Patterns

Genetic diversity parameters estimated for the 15 SSR loci across T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor are summarized in Table 2. The 15 SSR loci displayed substantial polymorphism, with Na ranging from 6 to 13 (mean = 8.53). The most variable markers were mTcCIR11 and mTcCIR61 (Na = 13), whereas loci such as mTcCIR13, mTcCIR21, mTcCIR22, and mTcCIR3 showed lower allelic counts (Na = 6). Hexp was consistently high (mean = 0.74), ranging from 0.53 (mTcCIR22) to 0.90 (mTcCIR61). In contrast, Ho exhibited broader variation (mean = 0.31), with values from 0.16 (mTcCIR3) to 0.55 (mTcCIR21). Loci combining high Hexp and low Ho, such as mTcCIR19 (Hexp = 0.89; Ho = 0.20) and mTcCIR61 (Hexp = 0.90; Ho = 0.25). E values ranged from 0.57 (mTcCIR22) to 0.89 (mTcCIR21), with a mean of 0.70, indicating generally balanced allele-frequency distributions across loci. PIC values were also high, ranging from 0.42 (mTcCIR22) to 0.88 (mTcCIR61). Notably, 12 of the 15 loci exhibited PIC values > 0.50, confirming that the SSR panel is highly informative for characterizing diversity patterns and population structure. The markers mTcCIR19 (PIC = 0.86) and mTcCIR61 (PIC = 0.87) were the most discriminatory.

Table 2.

Genetic diversity metrics and characteristics of the SSR markers used for the molecular characterization of T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor.

3.2. Population Structure and Cluster Assignment

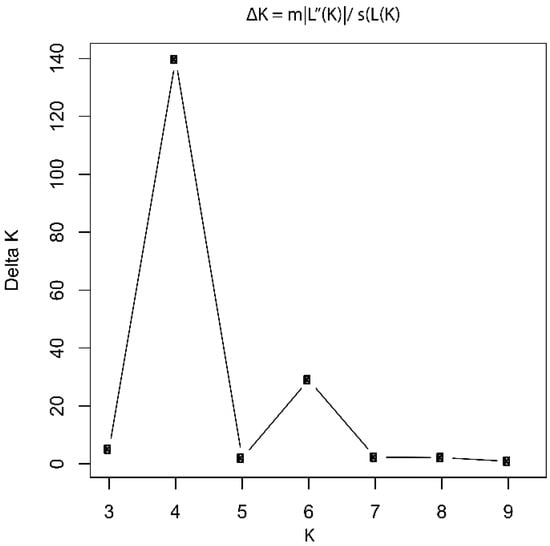

The Evanno method revealed a pronounced peak in ΔK at K = 4, identifying four as the most robust and biologically meaningful number of genetic clusters in the dataset. This result provided strong statistical support for the presence of four genetically distinct subpopulations among the 56 Theobroma individuals analyzed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Delta K values estimated using the Evanno method. The plot shows the rate of change in the log probability of the data [ΔK = mean(|L″(K)|)/S(L(K))] across different K values. A pronounced peak at K = 4 identifies four as the most likely number of genetic clusters in the dataset.

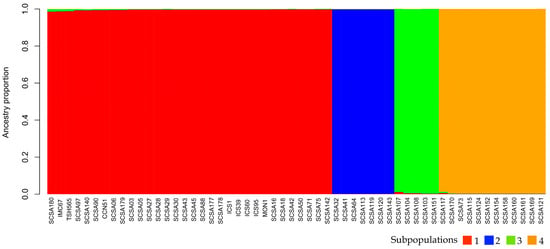

The STRUCTURE barplot aligned fully with the ΔK inference, showing a clear assignment of individuals into four discrete ancestry clusters with limited admixture (Figure 3). Subpopulation 1 comprised T. cacao accessions and universal reference clones; Subpopulation 2 included all T. bicolor genotypes; Subpopulation 3 represented a genetically differentiated subset of T. cacao; and Subpopulation 4 encompassed all T. grandiflorum individuals.

Figure 3.

Bayesian clustering analysis of the 56 Theobroma individuals using STRUCTURE. Each vertical bar represents an individual, partitioned into colored segments corresponding to the estimated membership coefficients (Q) for K = 4 genetic clusters. Colors denote assignment to the four inferred subpopulations, and the height of each segment indicates the proportion of ancestry contributed by each cluster.

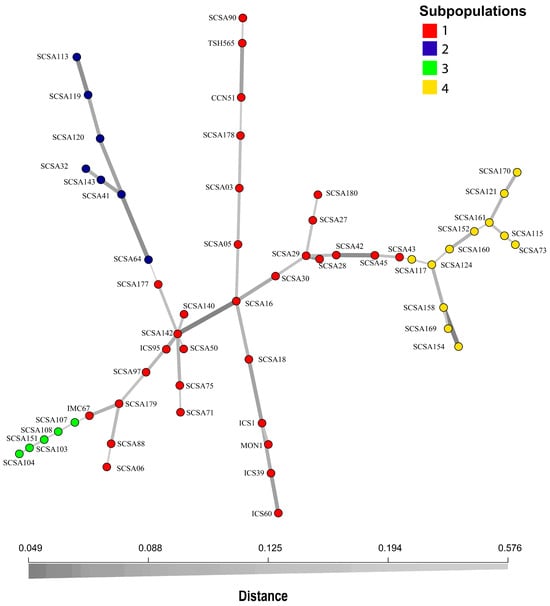

The MSN further corroborated these findings and revealed three well-separated species-level clusters—T. cacao, T. bicolor, and T. grandiflorum—with Subpopulation 3 forming a distinct subgroup within the T. cacao cluster. Network connectivity was high within T. cacao, whereas T. bicolor and T. grandiflorum appeared as isolated groups with longer branch lengths (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Minimum spanning network (MSN) constructed using Bruvo’s distance. Each node represents an individual sample. Colors denote membership in the four genetic subpopulations inferred from STRUCTURE. Edge lengths and thickness reflect genetic relatedness among samples, with shorter and darker edges indicating closer relationships among T. cacao, T. bicolor, and T. grandiflorum.

Collectively, the STRUCTURE and MSN analyses provided concordant evidence for four genetically coherent subpopulations, each representing a distinct component of the genetic architecture of the evaluated Theobroma germplasm.

Pairwise comparisons among the four subpopulations showed significant genetic differentiation in all cases (Table 3). FST values were highest between T. bicolor (Subpopulation 2) and T. grandiflorum (Subpopulation 4), followed by strong differentiation between these species and both T. cacao groups. The lowest differentiation occurred between Subpopulations 1 and 3 (both T. cacao), although it was still statistically significant.

Table 3.

Pairwise comparisons between subpopulations (FST values).

Table 4 summarizes the genetic diversity parameters for each subpopulation identified in the STRUCTURE analysis. Subpopulation 1 (n = 32), composed of regional T. cacao accessions and universal reference clones, exhibited the highest genetic diversity in the dataset. It contained the largest number of alleles (Na = 53) and private alleles (Npa = 33) (Supplementary Table S1), and all individuals represented unique multilocus genotypes (MLG = 32). Diversity indices—Shannon’s H (3.47), Stoddart and Taylor’s G (32), and Simpson’s λ (0.97)—indicated extensive genotypic richness and complete evenness (E5 = 1). Although expected heterozygosity was high (Hexp = 0.45), the reduced observed heterozygosity (Ho = 0.36) resulted in a positive inbreeding coefficient (Fis = 0.18). The standardized index of association (d = 0.00; p = 0.08) showed no evidence of multilocus linkage disequilibrium.

Table 4.

Indices of association and genetic diversity of subpopulations (Pop).

Subpopulation 2 (n = 7), composed exclusively of T. bicolor, presented lower allelic richness (Na = 26) but a remarkably high proportion of private alleles (Npa = 23). All individuals displayed unique multilocus genotypes (MLG = 7), and diversity indices indicated moderate variation (H = 1.95; λ = 0.86). Observed and expected heterozygosity were equal (Ho = Hexp = 0.25), resulting in an inbreeding coefficient near zero (Fis = 0.03). Despite this, the standardized index of association was relatively high (d = 0.56) and significantly different from random expectations (p = 0.02).

Subpopulation 3 (n = 5), a small but genetically distinct cluster within T. cacao, exhibited intermediate allelic richness (Na = 38) and a substantial number of private alleles (Npa = 16). Diversity metrics (H = 1.61; λ = 0.80) and heterozygosity values (Hexp = 0.44; Ho = 0.41) demonstrated appreciable genetic variability despite the small sample size. The low inbreeding coefficient (Fis = 0.05) indicated near-random mating, and the low standardized index of association (d = 0.06; p = 0.08) showed no significant multilocus disequilibrium.

Subpopulation 4 (n = 12), consisting of T. grandiflorum, displayed moderate allelic richness (Na = 39) and the highest number of private alleles among the species-level groups (Npa = 35). Although diversity indices were intermediate (H = 2.48; λ = 0.92), observed heterozygosity was markedly lower than expected (Ho = 0.17 vs. Hexp = 0.36), resulting in the highest inbreeding coefficient across groups (Fis = 0.44). However, the standardized index of association was minimal (d = 0.00) and non-significant (p = 0.12).

3.3. Multivariate Group Discrimination

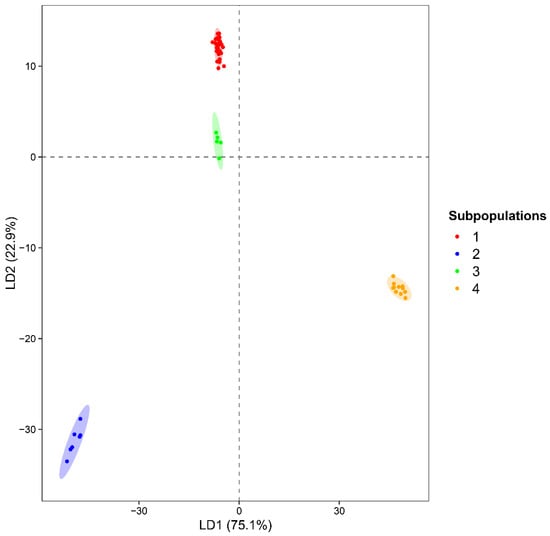

The DAPC revealed a clear and well-defined structure among the four subpopulations identified previously (Figure 5; Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 5.

Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC) of the 56 Theobroma accessions.

The first discriminant axis (LD1) accounted for 75.1% of the between-group discriminant variation, while the second axis (LD2) explained an additional 22.9%. The scatterplot of LD1 vs. LD2 showed four distinctly separated clusters, with Subpopulation 2 (T. bicolor) and Subpopulation 4 (T. grandiflorum) positioned at opposite extremes along LD1. Subpopulation 1, composed of regional T. cacao accessions together with universal reference clones, and Subpopulation 3, a smaller but clearly differentiated T. cacao cluster, appeared closer in discriminant space—consistent with their shared species identity but distinct lineage composition. In addition, within-group dispersion was low across all clusters. The DAPC loading profiles indicated that a limited subset of SSR loci accounted for most of the among-group discrimination (threshold = 0.05) (Supplementary Figure S1). Along LD1, the markers mTcCIR6, mTcCIR10, mTcCIR13, mTcCIR3, and mTcCIR12 showed the highest discriminatory power, while LD2 was primarily driven by the strong contributions of mTcCIR13 and mTcCIR17.

3.4. Partitioning of Molecular Variation

The AMOVA revealed a pronounced hierarchical genetic structure within the evaluated Theobroma germplasm (Table 5). The largest proportion of genetic variation was attributed to differences among subpopulations (56.68%), in agreement with the four-cluster partitioning inferred from STRUCTURE and the species-level separation observed in the MSN. Variation among individuals within subpopulations accounted for an additional 7.39%. The remaining 35.93% of total variation occurred within individuals.

Table 5.

Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) for the four subpopulations analyzed.

The overall fixation index (Φ = 0.57, p = 0.001) confirmed high and statistically significant population differentiation, fully supporting the division of the dataset into four genetically coherent subpopulations.

3.5. Genetic–Geographic Correlation

The Mantel test revealed an absence of significant isolation by distance, as genetic and geographic distances among the Theobroma accessions were not correlated (R2 = 0.009, p = 0.53).

4. Discussion

In this study, the high levels of polymorphism detected across the 15 SSR loci demonstrate that the evaluated Theobroma germplasm harbors substantial allelic richness, consistent with previous reports of high genetic diversity in T. cacao and its wild relatives throughout the Amazon Basin, especially in upper and western Amazonian populations [6,23,24,44,45]. The mean number of alleles per locus (8.53) aligns with values documented for both cultivated and wild cacao populations, confirming that SSRs remain highly informative markers for resolving fine-scale diversity patterns in Theobroma species [6,19,25].

The consistently high expected heterozygosity (Hexp = 0.74) indicates extensive underlying genetic variability, a pattern characteristic of Theobroma species due to their predominantly allogamous mating system and long evolutionary history in the Upper Amazon Basin [24,44,46,47]. However, the comparatively lower observed heterozygosity (Ho = 0.31) and the presence of loci showing marked heterozygote deficits (e.g., mTcCIR19 and mTcCIR61) suggest the influence of population subdivision and a resulting Wahlund effect, rather than true inbreeding, arising from isolated or partially isolated genetic subgroups [24,47,48]. Similar patterns have been reported in previous studies on Theobroma diversity, particularly when accessions represent mixtures of distinct genetic lineages or species-level divergences [24,46,47].

Evenness values (mean = 0.70) indicate moderate balance in allele-frequency distributions, which is expected in multispecies datasets where certain alleles are restricted to particular taxa. The high number of private alleles associated with several loci further supports the presence of species-specific or lineage-specific divergence, a phenomenon widely documented in comparative analyses involving Theobroma species [49]. The high PIC values (>0.50) confirm that the SSR panel used in this study is highly informative for population structure analyses. Such PIC levels are consistent with previous studies showing that SSR markers are among the most discriminating tools for identifying diversity gradients within and between cacao populations [19]. The high PIC values (>0.50) confirm that the SSR panel used in this study is highly informative for population structure analyses. Such PIC levels are consistent with previous studies showing that SSR markers are among the most discriminating tools for identifying diversity gradients within and between cacao populations [18,19,31].

Overall, the substantial allelic richness, high expected heterozygosity, and strong informativeness of the SSR loci demonstrate that the evaluated Theobroma germplasm maintains a broad genetic base. This level of diversity is particularly important for breeding and conservation programs, as it provides a reservoir of alleles linked to adaptive potential, climatic resilience, tolerance to biotic stressors, and long-term evolutionary stability [46,49].

The population structure analyses revealed the presence of four well-defined genetic clusters within the evaluated Theobroma germplasm, reflecting both species-level divergence and lineage differentiation within T. cacao. Recent studies have shown that different Theobroma species form deeply divergent evolutionary lineages within the genus, and such species-level structuring is typically recovered when multilocus markers or genome-wide SNPs are used [50,51]. Our findings align with this expectation: species identity emerged as the strongest determinant of genetic clustering.

Within T. cacao, two genetically distinct groups were identified. Subpopulation 1, which included regional accessions and universal reference clones, exhibited the highest allelic richness, the largest number of private alleles, and complete multilocus genotypic uniqueness. This agrees with recent evidence indicating that cultivated and wild cacao accessions often retain substantial allelic diversity due to historical introgression and complex domestication pathways in the upper and western Amazon [44,45].

The genetic distinctiveness of Subpopulation 3 likely reflects a combination of historical lineage differentiation and localized evolutionary processes, potentially driven by long-term farmer-mediated selection, restricted gene flow with commercial clones, and adaptation to the environmental conditions of the northwestern Amazon. Similar fine-scale genetic subdivisions within T. cacao have been documented in upper and western Amazonian populations, where ancient diversification, riverine barriers, and human-assisted dispersal have generated differentiated cacao lineages within the species [12,23,44,47,49]. From a conservation and breeding perspective, Subpopulation 3 constitutes a valuable genetic component of regional cacao diversity, preserving unique allelic combinations that may contribute to adaptive potential, resilience to environmental stress, and future genetic improvement efforts [44,48]. Its clear differentiation from widely used reference clones underscores the importance of conserving locally maintained cacao lineages as part of strategies aimed at enhancing the sustainability and resilience of Amazonian agroforestry systems [7,44].

By contrast, T. bicolor (Subpopulation 2) and T. grandiflorum (Subpopulation 4) appeared as clearly isolated groups with long branch lengths in the MSN, reflecting strong interspecific divergence. The high number of private alleles observed in both species further supports their deep evolutionary separation from T. cacao, consistent with recent comparative genomic analyses showing species-specific allelic repertoires and limited gene flow across Theobroma species [50,51,52].

Pairwise FST comparisons reinforced these patterns, with the highest differentiation observed between T. bicolor and T. grandiflorum, followed by strong differentiation between these species and both T. cacao groups. Although Subpopulations 1 and 3 (both T. cacao) showed the lowest differentiation, it remained statistically significant, indicating meaningful lineage divergence within the species. These findings align with contemporary views that cacao diversity is structured into multiple differentiated lineages shaped by long-term geographic isolation, riverine barriers, and historical demographic processes in the Amazon basin [7,44,50,53].

Multilocus genetic diversity indices further supported the observed structure. Subpopulation 1 exhibited high levels of genotypic richness, allelic diversity, and evenness, reflecting a broad genetic base maintained through predominantly sexual reproduction, as indicated by the lack of multilocus linkage disequilibrium (low d). In contrast, T. bicolor displayed moderate diversity but elevated d values, likely reflecting the effects of small effective population sizes and strong species-level divergence rather than clonal propagation. Subpopulation 4 (T. grandiflorum) showed the highest inbreeding coefficient, consistent with pronounced genetic subdivision and possible demographic constraints described for this species in recent studies [51,52]. Subpopulation 3 retained appreciable diversity despite its small size, with heterozygosity patterns suggesting near-random mating and ongoing recombination typical of seed-derived cacao populations with active sexual reproduction [49,53]. These results were highly concordant with the DAPC analysis, reinforcing the evidence for significant genetic differentiation among the four population groups. The fact that only a small subset of SSR loci contributed substantially to the discriminant functions suggests that genetic divergence among the four Theobroma subpopulations is strongly structured around specific genomic regions. Such concentration of discriminatory power in a few markers has also been reported in previous cacao diversity studies and is typical of systems in which species boundaries and intra-specific lineages or accessions are strongly differentiated [19,22,26].

The AMOVA results revealed a strong hierarchical genetic structure within the evaluated Theobroma germplasm, with more than half of the total genetic variation (56.68%) attributable to differences among subpopulations. This high among-group partitioning is fully consistent with the four genetic clusters inferred from STRUCTURE and the species-level separation observed in the MSN. Recent genomic studies have similarly reported that Theobroma species form deeply divergent evolutionary lineages, with substantial species-level differentiation that typically exceeds within-species genetic variability [44,50,51]. The moderate level of variation observed among individuals within subpopulations (7.39%) reflects residual genotypic differentiation that persists despite clear lineage boundaries. Such within-group diversity has been widely documented in Theobroma, particularly in T. cacao, where complex domestication managements, historical introgression, and localized evolutionary processes have shaped multiple divergent genetic backgrounds [44,49,54]. Furthermore, the substantial proportion of variation occurring within individuals (35.93%) is consistent with the predominantly outcrossing reproductive system of Theobroma species, which promotes heterozygosity and recombination-driven genetic structure [22,50]. The AMOVA results reinforce that the genetic architecture of the analyzed germplasm is shaped primarily by species identity and secondarily by lineage-level differentiation within T. cacao.

Consistent with these findings, the Mantel test revealed no significant correlation between genetic and geographic distances, indicating an absence of isolation by distance among the evaluated accessions. This lack of spatial structure is expected in multispecies germplasm collections where genotypes originate from different regions, ecological contexts, or historical introductions, effectively decoupling geographic proximity from genetic similarity. Similar outcomes have been reported for cacao collections with mixed ancestry, where species divergence and lineage-specific differentiation override any geographic signal in genetic data [49,54]. These results suggest that the genetic structure of 56 Theobroma accessions is driven predominantly by taxonomic boundaries and evolutionary history, rather than by spatially patterned gene flow [24,44,47,54].

The integrative assessment of genetic diversity, population structure, and molecular variance across three Theobroma species provides several key insights for conservation planning and the long-term resilience of agroforestry systems in the northwestern Amazon. The identification of four genetically coherent subpopulations highlights the substantial evolutionary differentiation that persists across the genus. This structure underscores the importance of conserving multiple Theobroma species, rather than focusing solely on cultivated cacao, as each lineage preserves unique allelic combinations and species-specific adaptations relevant for ecological stability and future breeding opportunities. This genetic reservoir is indispensable for buffering agroforestry systems against increasing drought and heat stress, seed cadmium (Cd) accumulation, emerging pests and diseases, low productivity and cacao bean quality, and loss of ecological connectivity in productive landscapes [54,55]. Recent studies have reinforced that access to genetically diverse Amazonian landraces enhances the adaptive potential of cacao-based production landscapes and supports the development of more resilient agroecological models [44,48,50,53,54].

Although this study provides robust and highly concordant evidence of genetic diversity and population structure among regional Theobroma accessions, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size of some subpopulations—particularly Subpopulation 3—was relatively small, which may limit the ability to fully capture the complete spectrum of genetic variation present within these lineages and may reduce statistical power for detecting very fine-scale diversity patterns. However, the consistency of Subpopulation 3 across multiple independent analytical approaches (STRUCTURE, DAPC, MSN, pairwise F_ST, and AMOVA), together with its distinct allelic composition, private alleles, and near-random mating patterns, supports its biological relevance and argues against a spurious clustering effect.

Second, this study employed a moderate panel of 15 SSR markers. While SSRs are highly polymorphic and have been widely validated as powerful tools for assessing genetic diversity, population structure, and lineage differentiation in Theobroma species, they provide lower genomic resolution than high-density SNP or whole-genome approaches. Consequently, localized signals of selection or fine-scale introgression at specific genomic regions may remain undetected. Nevertheless, the high levels of allelic richness, expected heterozygosity, PIC values, and the strong agreement among all multilocus analyses demonstrate that the SSR panel was sufficiently informative to resolve both species-level divergence and intra-specific lineage differentiation within T. cacao. Future studies incorporating expanded sampling and genome-wide marker systems will be valuable for refining lineage boundaries, characterizing adaptive variation, and further elucidating the evolutionary dynamics of Amazonian Theobroma germplasm [48,49,54].

The findings of this study have both direct and indirect implications for cacao farmers in the northwestern Amazon. Directly, the identification of genetically diverse and locally adapted Theobroma lineages provides a scientific basis for informed seed selection and on-farm conservation strategies, reducing reliance on genetically uniform planting material that may be more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate variability. Indirectly, maintaining genetically diverse regional cacao and its close relatives’ populations enhances the long-term resilience of agroforestry systems by stabilizing yields, supporting ecosystem services, and reducing economic risks associated with disease outbreaks or climatic extremes [54,55,56].

Additionally, genetic diversity and biodiversity monitoring are particularly critical in the context of emerging fungal, viral, and phytoplasma-associated disease outbreaks in cacao-growing regions [56,57,58]. Low genetic diversity and genetic uniformity in cacao plantations have been repeatedly associated with heightened vulnerability to epidemic outbreaks [56]. In contrast, genetically heterogeneous and taxonomically diverse agroforestry systems can reduce pathogen transmission efficiency and enhance disease buffering capacity at the landscape scale. The genetic structuring documented in this study highlights the importance of conserving multiple Theobroma lineages and species as a proactive strategy for mitigating disease risks and ensuring long-term agroecosystem stability in Amazonian cacao landscapes.

Finally, the strong genetic connectivity observed within T. cacao subpopulations, paired with the deep divergence found among species, suggests that integrating compatible Theobroma taxa into diversified agroforestry systems could enhance key ecosystem services, including pollinator support, biotic stress buffering, carbon storage and sequestration, and microclimatic regulation [7,54,59,60,61]. In this context, species like T. bicolor and T. grandiflorum, which exhibit strong lineage-specific divergence and high levels of private alleles, may represent valuable complementary components in mixed-species agroforestry arrangements. These findings reinforce the strategic importance of conserving and mobilizing Amazonian Theobroma diversity to enhance the ecological, genetic, and agronomic resilience of cacao agroforestry landscapes.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of genetic diversity, population structure, and varietal relationships among regional Theobroma accessions cultivated in agroforestry systems of the northwestern Colombian Amazon. We confirmed our hypothesis that these farmer-selected, sexually derived materials harbor substantial and distinctive genetic diversity. The high levels of polymorphism, abundant private alleles, and heterogeneous heterozygosity patterns observed across loci demonstrate that Amazonian Theobroma regional accessions retain extensive allelic richness that is not fully represented in universal T. cacao reference clones.

Population structure analyses consistently revealed four genetically coherent subpopulations corresponding to T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, T. bicolor, and a differentiated lineage within T. cacao. This evidence supports the expectation that regional accessions exhibit a detectable and biologically meaningful structure driven by species identity and lineage-level divergence. The strong interspecific differentiation detected highlights the deep evolutionary separation among the three Theobroma species. Within T. cacao, the marked diversity and genotypic richness of regional accessions indicate that farmer-mediated propagation, seed-based management, and local selection have played a critical role in maintaining and reshaping genetic variation in Amazonian agroforestry systems.

Collectively, our findings demonstrate that the Theobroma germplasm cultivated by smallholder farmers in the Colombian Amazon constitutes a significant reservoir of genetic diversity with clear implications for conservation and agroforestry resilience. Our results suggest that conservation strategies should prioritize maintaining taxonomic breadth and lineage representation at the same time; the genetic complementarities detected among species and lineages support the potential of diversified agroforestry systems to enhance ecological stability, adaptive capacity, and long-term sustainability of Amazonian cacao production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d18010020/s1. Figure S1: Main morpho-agronomic phenotypic traits of 48 outstanding regional accessions belonging to three Theobroma species. Figure S2: Principal component retention and marker contributions to the discriminant functions in the DAPC. Table S1: List of 48 regional Theobroma accessions (T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor) from the department of Caquetá, northwestern Colombian Amazon. Table S2: List of eight commercial T. cacao clones included as reference materials. Table S3: Summary of private alleles detected per subpopulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and G.P.V.-A.; methodology, F.H.P.-M., G.P.V.-A., A.S. and S.V.-C.; software, G.P.V.-A. and A.S.; validation, A.S.; formal analysis, G.P.V.-A. and A.S.; investigation, F.H.P.-M., G.P.V.-A., A.S., D.F.C.-R., J.C.S.-S., S.V.-C. and S.d.R.C.; resources, A.S. and C.H.R.-L.; data curation, F.H.P.-M., S.V.-C.; A.S. and G.P.V.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., G.P.V.-A. and S.V.-C.; writing—review and editing, A.S., G.P.V.-A., D.F.C.-R., S.d.R.C., J.C.S.-S. and C.H.R.-L.; visualization, A.S. and G.P.V.-A.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, C.H.R.-L.; funding acquisition, C.H.R.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was part of the following projects: (i) “Bioagrodiversidad del cacao para la conservación ambiental y la resiliencia climática—investigación de buenas prácticas entre Colombia, Portugal y Santo Tomé y Príncipe”, funded under a service contract between Associação Marquês de Valle Flôr (AMVF) and the Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas SINCHI. The partner institutions include the Instituto Marquês de Valle Flôr (IMVF), the Red Nacional de Agencias de Desarrollo Local de Colombia (RedAdelco), the Universidade de Évora (UÉ), SINCHI, the Centro de Investigação Agronômica e Tecnológica de São Tomé e Príncipe (CIAT), the Secretaria-Geral Ibero-americana (SEGIB), and Camões—Instituto da Cooperação e da Língua, I.P.; and (ii) “Selección y evaluación in situ de árboles élites del género Theobroma, como estrategia de rescate y aprovechamiento del germoplasma local con potencial para la Amazonia colombiana”—Contract RC No. 628-2011, Fiduciara Bogotá—Colciencias—SINCHI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the cacao farmers in the study area for their valuable help and support during the fieldwork. We also thank Herminton Muñoz-Ramírez for his support in preparing the cartographic resources used in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zhang, D.; Motilal, L. Origin, Dispersal, and Current Global Distribution of Cacao Genetic Diversity. In Cacao Diseases: A History of Old Enemies and New Encounters; Bailey, B.A., Meinhardt, L.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–31. ISBN 978-3-319-24789-2. [Google Scholar]

- International Cocoa Organization—ICCO. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics (Vol. LI, No. 2). Revised Estimates of World Cocoa Production, Grindings and Stocks for the 2023/24 Cocoa Year; International Cocoa Organization: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, B.G. The Genetic Diversity of Cacao and Its Utilization; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780851996196. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, A. The Colombian Cacao Sector—2024 Update; USDA Foreign Agricultural Service: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Wightman, W.; López, J.A.; Castaño, E.; Jimenez, M.; Mayta, S.; Pivesso, M.; Correa, L.F.; Turriago, S. Estudio de Línea Base Cacao de Origen Amazónico Brasil, Colombia y Perú; TFA-Alisos: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Melgarejo, L.M.; Hernández, M.S.; Barrera, J.A.; Carrillo, M. Oferta y Potencialidades de Un Banco de Germoplasma del Género Theobroma en el Enriquecimiento de los Sistemas Productivos de la Región Amazónica; Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas–Sinchi: Bogotá, Colombia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lagneaux, E.; Andreotti, F.; Neher, C.M. Cacao, Copoazu and Macambo: Exploring Theobroma Diversity in Smallholder Agroforestry Systems of the Peruvian Amazon. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.S.; Barrera, J.A. Frutas Amazónicas Competitividad e Innovación; Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas–Sinchi: Bogotá, Colombia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio-Guarín, J.A.; Berdugo-Cely, J.A.; Coronado-Silva, R.A.; Baez, E.; Jaimes, Y.; Yockteng, R. Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Novel Candidate Genes Associated with Productivity and Disease Resistance to Moniliophthora Spp. in Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.). G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2020, 10, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulai, I.; Hoffmann, M.; Kahiluoto, H.; Dippold, M.A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Asare, R.; Asante, W.; Rötter, R.P. Functional Groups of Leaf Phenology Are Key to Build Climate-Resilience in Cocoa Agroforestry Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 379, 109363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boza, E.J.; Motamayor, J.C.; Amores, F.M.; Cedeño-Amador, S.; Tondo, C.L.; Livingstone, D.S.; Schnell, R.J.; Gutiérrez, O.A. Genetic Characterization of the Cacao Cultivar CCN 51: Its Impact and Significance on Global Cacao Improvement and Production. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2014, 139, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Duran, P.; Berdugo-Cely, J.A.; Mejía-Salazar, J.; Pérez-Zúñiga, J.I.; Yockteng, R. Exploring the Diversity and Ancestry of Fine-Aroma Cacao from Tumaco, Colombia. Diversity 2024, 16, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Orozco, C.E.; Osorio-Guarín, J.A.; Yockteng, R. Phylogenetic Diversity of Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Genotypes in Colombia. Plant Genet. Resour. 2022, 20, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, A.; Ferney, D.; Rodríguez, C.; Hernando, C.; León, R.; Nel, P.; Torres, R.; Marieth, Y.; Tobón, S.; Natali, M.; et al. Variabilidad Morfoagronómica de 50 Materiales Promisorios de Tres Especies de Theobroma (Malvaceae) En Condiciones de La Amazonia Colombiana. Rev. Colomb. Amaz. 2013, 6, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, A.; Daza-Hermida, M.A.; Rodrigue-León, C.H.; Salas-Tobón, Y.M.; Nieto-Guzmán, M.N.; Rodríguez-Caicedo, D.F. Reacción a Moniliophthora roreri en Theobroma spp. en Caquetá, Colombia. Summa Phytopathol. 2015, 41, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, I.; Zárate, L.A.; Gallego, G.; Tohme, J. Análisis de la Diversidad Genética de Accesiones de Theobroma cacao L. del Banco de Conservación a Cargo de Corpoica. Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecu. 2008, 8, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo, C.Y.; Morillo, C.A.C.; Muñoz, F.J.E.; Ballesteros, P.W.; González, A. Molecular Characterization of 93 Genotypes of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) with Random Amplified Microsatellites RAMs. Agron. Colomb. 2014, 32, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, H.; De Wever, J.; Tang, T.K.H.; Vu, T.L.A.; Maebe, K.; Rottiers, H.; Lefever, S.; Smagghe, G.; Dewettinck, K.; Messens, K. Genetic Classification of Vietnamese Cacao Cultivars Assessed by SNP and SSR Markers. Tree Genet. Genomes 2020, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyango, N.M.C.; Sounigo, O.; Fouet, O.; Tekeu, H.; Djocgoué, F.P.; Efombagn, M.I.B.; Lanaud, C. Genetic Diversity and Verification of Plant Material Compliance of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) in the Barombi-Kang Regional Variety Trial. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustamante, D.E.; Motilal, L.A.; Calderon, M.S.; Mahabir, A.; Oliva, M. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Fine Aroma Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) from North Peru Revealed by Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Markers. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 895056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Guarín, J.A.; Berdugo-Cely, J.; Coronado, R.A.; Zapata, Y.P.; Quintero, C.; Gallego-Sánchez, G.; Yockteng, R. Colombia a Source of Cacao Genetic Diversity as Revealed by the Population Structure Analysis of Germplasm Bank of Theobroma cacao L. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Luseni, M.M.; Ametefe, K.; Agre, P.A.; Kumar, P.L.; Grenville-Briggs, L.J. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Germplasm from Sierra Leone and Togo Based on KASP–SNP Genotyping. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Guarín, J.A.; Berdugo-Cely, J.A.; Garzón-Martínez, G.A.; Toloza-Moreno, D.L.; Delgadillo-Duran, P.; Báez-Daza, E.Y.; Meinhardt, L.W.; Park, S.; Zhang, D.; Yockteng, R. Assessing Genetic Redundancy and Diversity in Colombian Cacao Germplasm Banks Using SNP Fingerprinting. Front. Plant. Sci. 2025, 16, 1632888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamayor, J.C.; Lachenaud, P.; da Silva e Mota, J.W.; Loor, R.; Kuhn, D.N.; Brown, J.S.; Schnell, R.J. Geographic and Genetic Population Differentiation of the Amazonian Chocolate Tree (Theobroma cacao L). PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, W.J. La Variabilidad Genética Del Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Nacional Boliviano. Rev. Carrera Ing. Agronómica-UMSA 2016, 2, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.; Gori, M.; Bini, L.; Ordoñez, E.; Durán, E.; Gutierrez, O.; Masoni, A.; Giordani, E.; Biricolti, S.; Palchetti, E. Genetic Purity of Cacao Criollo from Honduras Is Revealed by SSR Molecular Markers. Agronomy 2021, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haymes, K.M.; Ibrahim; Mischke, S.; Scott, D.L.; Saunders, J.A. Rapid Isolation of DNA from Chocolate and Date Palm Tree Crops. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5456–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaud, C.; Risterucci, A.M.; Pieretti, I.; Falque, M.; Bouet, A.; Lagoda, P.J.L. Isolation and Characterization of Microsatellites in Theobroma cacao L. Mol. Ecol. 1999, 8, 2141–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Boccara, M.; Motilal, L.; Mischke, S.; Johnson, E.S.; Butler, D.R.; Bailey, B.; Meinhardt, L. Molecular Characterization of an Earliest Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Collection from Upper Amazon Using Microsatellite DNA Markers. Tree Genet. Genomes 2009, 5, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemes, M.R.; Martiniano, T.M.; Reis, V.M.; Faria, C.P.; Gribel, R. Cross-Amplification and Characterization of Microsatellite Loci for Three Species of Theobroma (Sterculiaceae) from the Brazilian Amazon. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2007, 54, 1653–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeeswari, V.; Padmadevi, K.; Vijayalatha, K.R.; Suresh, J. Assessment of Polyclonal Derivatives for Morphological Traits and Hybridity Analysis Using SSR Markers in Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.). Plant Sci. Today 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.M.; Sebbenn, A.M.; Artero, A.S.; Figueira, A. Microsatellite Loci Transferability from Theobroma cacao to Theobroma Grandiflorum. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 1219–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamvar, Z.N.; Tabima, J.F.; Grünwald, N.J. Poppr: An R Package for Genetic Analysis of Populations with Clonal, Partially Clonal, and/or Sexual Reproduction. PeerJ 2014, 2, e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T. Adegenet: A R Package for the Multivariate Analysis of Genetic Markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the Number of Clusters of Individuals Using the Software Structure: A Simulation Study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.; Wen, X.; Falush, D. Documentation for Structure Software: Version 2.3. Structure. 2010. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/group/pritchardlab/structure_software/release_versions/v2.3.4/html/structure.html (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Earl, D.A.; vonHoldt, B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A Website and Program for Visualizing STRUCTURE Output and Implementing the Evanno Method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruvo, R.; Michiels, N.K.; D’Souza, T.G.; Schulenburg, H. A Simple Method for the Calculation of Microsatellite Genotype Distances Irrespective of Ploidy Level. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 2101–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Cockerham, C.C. Estimating F-Statistics for the Analysis of Population Structure. Evolution 1984, 38, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudet, J.; Jombart, T. Hierfstat: Estimation and Tests of Hierarchical F-Statistics v.0.5-11. CRAN: Contributed Packages. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/hierfstat/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Agapow, P.-M.; Burt, A. Indices of Multilocus Linkage Disequilibrium. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2001, 1, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenALEx 6.5: Genetic Analysis in Excel. Population Genetic Software for Teaching and Research-an Update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colli-Silva, M.; Richardson, J.E.; Pirani, J.R.; Figueira, A. Wild or Introduced? Investigating the Genetic Landscape of Cacao Populations in South America. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieves-Orduña, H.E.; Müller, M.; Krutovsky, K.V.; Gailing, O. Geographic Patterns of Genetic Variation among Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Populations Based on Chloroplast Markers. Diversity 2021, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, M.L.; Albuquerque, P.S.B.; Vencovsky, R.; Figueira, A. Genetic Diversity and Natural Population Structure of Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) from the Brazilian Amazon Evaluated by Microsatellite Markers. Conserv. Genet. 2006, 7, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; van Zonneveld, M.; Loo, J.; Hodgkin, T.; Galluzzi, G.; van Etten, J. Present Spatial Diversity Patterns of Theobroma cacao L. in the Neotropics Reflect Genetic Differentiation in Pleistocene Refugia Followed by Human-Influenced Dispersal. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.T.; Arigoni, F.; Holzwarth, J.A.; Bellanger, L.; Descombes, P.; Beche, E.; Lass, T.; Guiltinan, M.J.; Maximova, S.N.; Leandro, M.; et al. Developing a Core Collection for the Conservation of Theobroma cacao’s Genetic Diversity. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, O.E.; Yee, M.-C.; Dominguez, V.; Andrews, M.; Sockell, A.; Strandberg, E.; Livingstone, D.; Stack, C.; Romero, A.; Umaharan, P.; et al. Population Genomic Analyses of the Chocolate Tree, Theobroma cacao L., Provide Insights into Its Domestication Process. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossa-Castro, A.M.; Colli-Silva, M.; Pirani, J.R.; Whitlock, B.A.; Morales Mancera, L.T.; Contreras-Ortiz, N.; Cepeda-Hernández, M.L.; Di Palma, F.; Vives, M.; Richardson, J.E. A Phylogenetic Framework to Study Desirable Traits in the Wild Relatives of Theobroma cacao (Malvaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2024, 62, 963–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.M.; de Abreu, V.A.C.; Oliveira, R.P.; Almeida, J.V.d.A.; de Oliveira, M.d.M.; Silva, S.R.; Paschoal, A.R.; de Almeida, S.S.; de Souza, P.A.F.; Ferro, J.A.; et al. Genomic Decoding of Theobroma Grandiflorum (Cupuassu) at Chromosomal Scale: Evolutionary Insights for Horticultural Innovation. Gigascience 2024, 13, giae027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Abreu, V.A.C.; Moysés Alves, R.; Silva, S.R.; Ferro, J.A.; Domingues, D.S.; Miranda, V.F.O.; Varani, A.M. Comparative Analyses of Theobroma cacao and T. grandiflorum Mitogenomes Reveal Conserved Gene Content Embedded within Complex and Plastic Structures. Gene 2023, 849, 146904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieves-Orduña, H.E.; Müller, M.; Krutovsky, K.V.; Gailing, O. Genotyping of Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Germplasm Resources with SNP Markers Linked to Agronomic Traits Reveals Signs of Selection. Tree Genet. Genomes 2024, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Orduña, H.E.; Krutovsky, K.V.; Gailing, O. Geographic Distribution, Conservation, and Genomic Resources of Cacao Theobroma cacao L. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 1750–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, G.J.; Martello, F.; Sabino, W.O.; Oliveira Andrade, T.; Costa, L.; Teixeira, J.S.G.; Giannini, T.C.; Carvalheiro, L.G. Tropical Forests and Cocoa Production: Synergies and Threats in the Chocolate Market. Environ. Conserv. 2025, 52, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Santos, T.L.; Araújo Tavares da Silva, F.L.; Araújo Dionízio da Silva, D.; Efraim, P. Exploring the Research Evolution of Cacao Diseases over the Past Two Decades: A Review. Plant Pathol. 2025, 74, 1470–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelli, J.-P.; Guest, D.I.; Bailey, B.A.; Evans, H.C.; Brown, J.K.; Junaid, M.; Barreto, R.W.; Lisboa, D.O.; Puig, A.S. Chocolate Under Threat from Old and New Cacao Diseases. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.P.; Bertaccinii, A.; Fiore, N.; Liefting, L.W. Phytoplasmas: Plant Bacteria—I—Characterisation and Epidemiology of Phytoplasma-Associated Diseases; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Moyano, D.K.; Rodríguez-Cruz, F.A.; Hormaza-Martínez, P.A.; Ramírez-Godoy, A. Characterization of Pollinators Associated with Cocoa Cultivation and Their Relationship with Natural Effective Pollination. Diversity 2025, 17, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, T.A.; Atta-Boateng, A.; Toledo-Hernández, M.; Wood, A.; Malhi, Y.; Solé, M.; Tscharntke, T.; Wanger, T.C. Global Chocolate Supply Is Limited by Low Pollination and High Temperatures. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, A.; Suárez-Córdoba, Y.D.; Orlandi, F.d.B.; Rodríguez-León, C.H. Soil–Atmosphere GHG Fluxes in Cacao Agroecosystems on São Tomé Island, Central Africa: Toward Climate-Smart Practices. Land 2025, 14, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.