Abstract

The optimal search strategy for foraging animals can vary based on environmental parameters, which can include information about the spatial distribution of prey. We tested the hypothesis that natural populations of foraging desert grassland whiptails (Aspidoscelis uniparens) structure their search strategies according to resource distribution. We experimentally provisioned prey in uniform, aggregated, and random distributions to characterize search effort (moves per minute and percent time moving) and search path (turn angles, movement duration, path straightness, step length, and two-step sequences). The search effort did not vary with treatment but animals adjusted their search path based on the presence and distribution of supplemental prey. With uniformly distributed prey, foragers took longer step lengths and more frequently engaged in two-step sequences that included long step lengths. When prey were randomly distributed, foragers made more moves of long duration and fewer straight moves, often pairing short step lengths with large turns. With an aggregated prey distribution, foragers had more moves of very short duration. Examining detailed search path characteristics can identify responses to environmental changes. Under experimental conditions, the search strategies of A. uniparens indicated behavioral responses to food distribution that could improve search efficiency.

1. Introduction

Movement is an integral aspect of the way an animal functions in the environment, with the search for food, alongside predation avoidance and thermoregulation, being among the most important aspects of daily activities. Search strategy, which describes the movement of a forager looking for food, can have a dramatic effect on the success of search efforts [1,2]—locating food can be time-consuming, energetically costly, risky, and involve trade-offs with other functions such as reproduction [3,4,5]. Optimal foraging theory postulates that animals adjust their search paths based on experience and animals are expected to adapt movement patterns for search strategies that efficiently locate resources [6,7,8]. The optimal search strategy for a forager varies with the characteristics of prey and the environment [6,9,10,11,12]. Although environmental cues and memory can be used to efficiently locate food, sensory and location-specific information are not always available [1,6,13]. Animals can improve the efficiency of search efforts by structuring their search strategy based on the spatial distribution of resources [6,14,15,16] with different resource distributions leading to different optimal search strategies [17,18]. Animals can vary their search strategy (i.e., movement pattern) based on resource distribution [8,10], even when such information is not location specific [1]. When the sought-after resource is food, animals can use information on the pattern of food distribution to both locate and exploit food patches [19,20,21], with a variety of animals exhibiting effective search paths for particular prey distributions [6,22]. For example, models predict that random search strategies can vary in their effectiveness in locating food patches based on food distributions and densities [13,23]. Animals can improve the efficiency of their search for food by learning to modify their search paths based on the degree of prey clumping [24,25,26], with search paths characterized by frequent short and medium length moves interspersed with long moves (i.e., Lévy search patterns) being effective for sparse prey and those with random (i.e., Brownian) movement proving most efficient for abundant prey [6,22]. Saltatory search behavior, in which individuals alternately move and pause along search paths while foraging, is characteristic of a wide variety of animals [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Saltatory foragers are known to alter pause and move characteristics in response to changes in prey detectability, density, and type [33,34,35,36], as well as habitat [37,38,39].

Once food patches are located, patterns of food distribution can help inform foragers on how to efficiently exploit patches [10,24,40,41]. Some foraging animals use prior estimates of prey distribution to determine how to search in a patch [42,43]. Area-restricted searching (ARS), which is intensive searching for food in a concentrated area, can be triggered by (1) sensory cues stimulated when searching for clustered food, (2) expectations for food to be concentrated based on experience, or (3) uncertainty concerning where food might be encountered [44,45]. ARS also increases search efficiency when food occurs in loose clusters [46] and can be undertaken when encountering a prey item that is typically aggregated, but not for one that is typically dispersed (e.g., termite vs. fly, Pedioplanis namaquensis) [47]. ARS has been documented in diverse taxa ranging from nematodes [48] to humans [49].

The variability of search paths can reflect either a composite search strategy that involves finding food using different search behaviors at different times [50], or a blended search strategy that involves searching for multiple prey types [13]. Animals adjust their search strategy based on search costs and availability of each prey type [51]. Changes to search behavior in response to changes in resource attributes can indicate behavioral flexibility and offer an ecologically relevant perspective on an animal’s ability to respond to other novel changes [52].

To account for nuances in search strategies with varying conditions, characterizing searches requires examining behavior from several perspectives. For example, lizard search behavior often has been described using broad measures: percent time moving (PTM) and moves per minute (MPM) [29,53]. Also of importance is the duration of individual movement bouts, which is strongly correlated with PTM, making variability in movement duration a more effective measure of search behavior [54]. Although such metrics have proven effective for understanding environmental and evolutionary factors influencing lizard foraging [55,56,57], they are too general to capture many aspects of search behavior associated with foraging success [54,58,59]. Recent work in movement ecology places a greater emphasis on the spatiotemporal profile of search behavior, where the specific distances, directions, and sequences of distances and directions traveled are examined [1,60,61,62]. Optimizing search success can depend on not only the frequency of the movement components of animal searches, but also the relationship between them [1]. Understanding the spatiotemporal characteristics of movement can provide insights into the adaptive and flexible nature of search behavior [63,64].

Our study focuses on how animals use prey distribution to inform their search strategy, concentrating on the foraging behavior of the desert grassland whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis uniparens, a small, diurnal, all-female, parthenogenic lizard species occupying Chihuahuan desert grassland in Arizona and New Mexico. Active individuals engage in minimal conspecific interaction and have extensive overlap in their home ranges [65,66]. In the absence of elaborate social or reproductive behaviors, active A. uniparens primarily are involved in foraging, wherein they travel through the environment in a series of moves and pauses. Based on direct observations of foraging A. uniparens, fossorial prey (i.e., termites, reproductive ants, and insect larvae) are an abundant component of their diet [66]. However, they also commonly pursue and ingest above-ground prey [65,67]. While they might use scent to find some food, they also can use visual cues to find prey [67]. Individuals occupy relatively small home ranges (median 770 m2), with most activity concentrated in a small portion of their home range [65]. During field manipulations of above-ground prey availability, A. uniparens responded to increased food availability by shifting the location of their home range towards regions of increased food availability, in addition to changing their pattern of space use within their home range [65]. In captivity, A. uniparens can assess patch quality for fossorial prey and adjust foraging effort [68]. We hypothesized that free-ranging A. uniparens would alter their search strategy based on the distribution of a novel, above-ground food source to fit the probabilistic distribution of the novel prey. We characterize search strategy with traditional measures of search effort (PTM, MPM) coupled with spatiotemporal variables used by movement ecologists to characterize the search path (turn angle, movement duration, path straightness, step length, and two-step sequences). Specifically, we assess model-based predictions [19,69] that animals will choose an efficient search strategy that varies with prey distribution, wherein a search path with directional persistence will occur most commonly in animals exposed to uniform prey distributions, while more circuitous search paths will occur among animals exposed to aggregated food distributions, and search paths with an intermediate level of straightness will occur among animals exposed to random prey distributions.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted field experiments during July 2000 in the desert grasslands of southeastern Arizona, approximately 5 km east of Portal, Arizona, USA. The dominant plants in the study area were Gutierrezia spp., Ephedra spp., and Prosopis glandulosa. First, we established 12-50 m × 50 m study plots that were similar in vegetation and separated from each other by at least 150 m. By marking out a grid with flags at 5 m intervals, we created 100-5 m × 5 m interior cells on each plot. Next, we captured whiptails on each plot using portable corrals. We measured and individually marked the lizards using unique color combinations of small plastic beads attached to a monofilament line inserted through the dorsal base of the tail [70]. We released all marked lizards at their original capture location later on the same day. Once we had a marked population of individuals with a natural range that included the study plots, we began the experimental phase (8–21 July).

We blocked the 12 plots into three replicate groups of four, and then randomly assigned the plots in each block to one of our four treatments: control, random, uniform, or aggregated (Figure 1). To allow lizards some time to become familiar with the experimental conditions, 4 d prior to commencing observations we began providing supplemental prey on random, uniform, and aggregated plots. Daily, each supplemented plot received 100 live mealworms (beetle larva—Tenebrio molitor; average length 12 mm) that were placed individually in small plastic trays (4 cm × 4 cm × 0.75 cm), with the spatial distribution of supplemental food varying by treatment. Natural food sources were not excluded and were also accessible to lizards. Control plots received 100 empty trays placed at 5 m intervals throughout the plot. Uniform plots contained mealworms placed at 5 m intervals across the entire plot. On random plots, the placement of mealworms conformed to a Poisson distribution [71] with a mean addition of one mealworm per 5 m × 5 m cell. The number of mealworms placed in specific cells (range = 0–4) and their position within a cell was determined randomly. The placement of mealworms on aggregated plots followed a negative binomial distribution (k = 0.5) [71] with a mean addition of one mealworm per 5 m × 5 m cell (range = 0–8). Tray position within a cell was systematic for uniform and control plots but determined randomly on random and aggregated plots. Trays were placed in the field each morning before lizards became active (placement was finished by 06:45 h) and removed at the end of the morning activity period (≤11:00 h). We varied the pattern of mealworm placement for random and aggregated patterns each day and on each plot. On control and uniform plots, the position of trays within each cell was shifted each day. Thus, the opportunity existed for foragers to learn the probability distribution of trays, without being able to rely on spatial memory to locate trays. Further, we positioned the trays with supplemental food in the open but foragers could not rely solely on visual detection to locate nearby trays. We examined the ground contour as we placed the trays, sighting along the ground in different directions as close as possible to the eye level of lizards to ensure that visual cues could not be used to find nearby trays. On control and uniform plots, trays were 10 m apart and landscape features precluded a lizard visiting one tray from seeing additional trays. On random and aggregated plots trays were placed within the constraints of the treatment while ensuring that nearby trays could not be discovered solely based on visual cues.

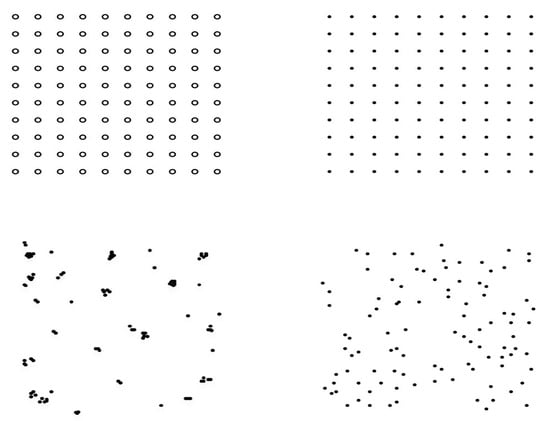

Figure 1.

Arrangement of supplemental prey on study plots with representative configurations of trays containing larvae for uniform plots (top right), random (bottom right), and aggregated plots (bottom left). The open circles on control plots (top left) represent positions of empty trays (no prey larva). Closed circles represent the position of trays, each containing one mealworm larva.

We evaluated search strategies by recording foraging behavior during 20 min focal observations. We balanced observations among treatments so that lizards were sought from each treatment each day. Most lizards were only observed once, on one day. Since lizards were able to leave the study plots, some had initial observations less than a full period. Some lizards were observed more than once and their data combined for analyses. We identified lizards to observe by searching study plots during their morning activity period for marked lizards that had not been previously observed. Upon identifying a suitable individual, two observers, remaining 5–10 m from the focal lizard, recorded the time, treatment, plot, and lizard identity. In the lab prior to beginning observations, we constructed a scale map of the plot grid system (4 cm = 5 m) that one observer used to anchor the starting position of the focal whiptail and then sketch its path throughout the observation. We waited 5 min after finding a lizard to allow her to acclimate to the observers. Lizards under observation often moved towards observers and seemed unaffected by our presence. Once observations began, one observer recorded the frequency of movements and the duration of each movement, using a hand-held calculator programmed as an event recorder (HP 50, Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA). At the same time, the second observer made a continuous tracing of the lizard’s movements and recorded the location of the lizard every 20 s on a scale map. Prior to data collection, we conducted practice focal observations of lizards off-site to ensure that observers doing the same task would produce the same results. We defined a movement as motion preceded and followed by a pause. We terminated observations prior to 20 min if the focal lizard left the experimental plot or if visual contact could not be maintained. From the maps, we determined (1) step length: the straight-line distance between the start and end locations of a 20 s interval (2) route length: the distance walked from the map tracing by a moving lizard during each 20 s interval, (3) turn angle: the angle between two consecutive step displacements, and (4) step straightness: the ratio of step length to corresponding route length. Straightness values can range from 0 (most convoluted) to 1 (straightest). From the event recorders, we were able to determine (5) move duration and calculate both (6) moves per minute (MPM) and (7) percentage of time moving (PTM). The suite of metrics we used allowed us to examine spatiotemporal aspects of foraging typically associated with path analysis in movement ecology (i.e., metrics 1–4) and those more commonly used to characterize saltatory searching (i.e., metrics 5–7), with route length, MPM and PTM providing a measure of foraging effort.

We characterized search strategies through an examination of search paths (i.e., move components and sequences). For analyses, movement duration, turn angle, step length, route length, and step straightness for all animals observed under the same treatment were pooled, and each individual lizard provided a single MPM and PTM value. We compared the distributions of metrics 1–5 using the pooled values from individuals and employing Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. We explored differences in movement metrics 1–5 using GLMM with treatment as a fixed effect and individual lizard as a random effect. ANOVA was used to compare MPM and PTM. Movement metrics were examined for normality and heteroskedasticity; move duration was log-transformed for analysis. Initial analyses included body size (SVL) as a covariate, but it was not a significant factor (p > 0.25) for any of the movement metrics and omitted from the final analyses. Tukey tests, with p < 0.05, were used for post hoc comparisons. We used Pearson correlations to examine the relationships between variables (step length and turn angle) and 1-unit lags within variables (movement duration, turn angle, and step length). We present summary data as mean ± SE and assigned statistical significance to results when p ≤ 0.05. We used Minitab 21 (3081 Enterprise Drive, State College, PA, USA) for statistical tests.

3. Results

We captured, measured, and marked 129 A. uniparens in our study area (SVL mean = 62.8 mm, SE = 0.365). We conducted focal observations on 60 of them, with each individual observed only on one plot (i.e., one treatment condition per individual). Body size (SVL) did not vary significantly with treatment or plot (ANOVA: F3,125 = 1.26, p = 0.29 and F11,128 = 0.95, p = 0.497, respectively). Search effort (i.e., PTM and MPM) did not vary among treatments (Table 1). However, lizards in different treatments did vary in search strategy (i.e., how they foraged).

Table 1.

Movement parameters (mean ± SE) for A. uniparens, with ANOVA and GLMM test statistics (F (p)). Only straightness had significantly different treatment means. Means that do not share a subscript are significantly different. The number of whiptails observed in each treatment (n) is given under the respective treatment heading. Move duration was log-transformed for analysis, with original values presented here.

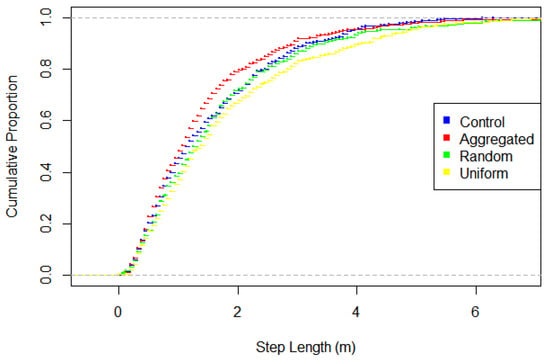

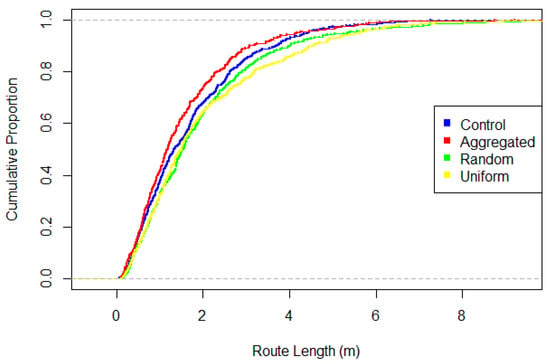

Although mean step length and route length did not differ among treatments, with foraging A. uniparens moving an average of 1–2 m/20 s (Table 1), the distributions of step lengths and route lengths differed significantly among treatments. For step lengths, aggregated foragers differed from all other treatments, and the uniform and control distributions differed from each other (Table 2, Figure 2). Aggregated foragers took more short step lengths than other treatments, while uniform foragers had fewer short step lengths than controls (Figure 2). For route length, every pair of treatments differed, except uniform vs. random (Table 2, Figure 3). Aggregated foragers had more short route lengths than other treatments, while uniform and random foragers had fewer short route lengths than the other treatments (Figure 3). Turn angle did not differ in magnitude or distribution among treatments (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical results (D (p)) from pair-wise Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for comparing cumulative distributions for movement metrics: step length, route length, move duration, straightness, and turn angles. Significant values are in bold.

Figure 2.

Cumulative distribution of step lengths for the four treatments (possible values 0–1, indicated by dashed grey lines). Aggregated differs significantly from all other treatments and control vs. uniform also differs.

Figure 3.

Cumulative distribution of route lengths for the four treatments (possible values 0–1, indicated by dashed grey lines). All pairs differ significantly, except random vs. uniform.

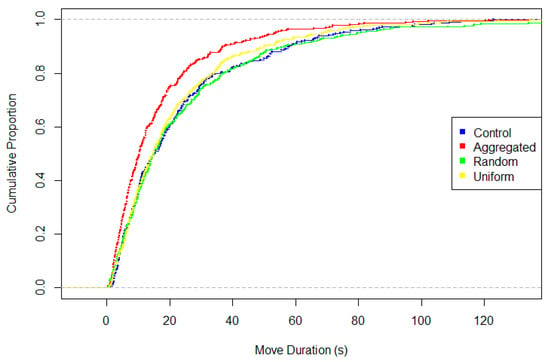

Move duration was independent of treatment, with foraging A. uniparens traveling an average of ca. 20 s/move (Table 1). However, move duration distributions varied among treatments—aggregated foragers differed from all other treatments, but no other pairwise comparisons were significant (Table 2, Figure 4). On aggregated plots, moves of shorter duration were more common compared to other treatment plots (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cumulative distribution of movement durations for the four treatments. Aggregated differs significantly from all other treatments.

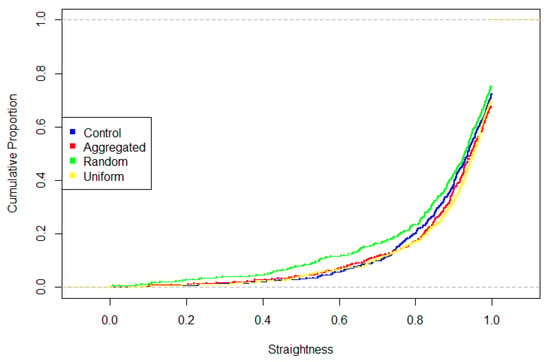

Finally, treatment groups varied in the straightness of their search paths, with random plot foragers having more convoluted paths than uniform plot foragers (Table 1, T = 2.91, p = 0.028). The distribution of straightness differed among treatments, with uniform foragers differing from control and random foragers by having a higher proportion of “straight” segments (Table 2, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cumulative distribution of step straightness (possible values 0–1, indicated by dashed grey lines). Values closer to 1 indicate straighter search paths and values closer to 0 indicate more convoluted search paths. Uniform differs significantly from both control and random.

Sequential analyses indicated that search paths were structured—step lengths were positively lag correlated for all treatments, as were turn angles (Table 3) and movement durations were positively lag correlated for aggregated, random, and uniform foragers (Table 3). Turn angles were related to both step length (GLMM: F = 15.66, p < 0.001) and the interaction between treatment and step length (F = 3.41, p = 0.017). Step length was negatively correlated with turn angle for control, aggregated, and random foragers, while lacking that relationship for uniform foragers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation results (r (p)) of 1-lags for step length, turn angle, and move duration, as well as the correlation between step length and turn angle. Significant correlations are bold.

4. Discussion

Prey distribution influenced A. uniparens search strategy through search path but not search effort. When examining search strategy through general measures (=search effort: PTM and MPM), individuals from all treatments were similar. However, PTM and MPM did not capture the spatial variation in search behavior arising from the different experimental treatments. The response of whiptails we observed was consistent with models that describe ways to improve search efficiency given different prey distributions [13,46,63,72]. Our hypothesis that A. uniparens would alter their search strategy based on the distribution of a novel food source to fit the probabilistic distribution of the novel prey was supported. A detailed analysis of search paths revealed that these saltatory foragers used information about prey distributions to structure their search strategy through the paths with which they searched (i.e., by adjusting move components and sequences).

Foraging A. uniparens encounter a diverse array of natural prey—some underground, some associated with vegetation, and some in the open. As they move through the environment, they spend a considerable amount of time moving, with noticeable pauses that facilitate further inspection of the immediate surroundings. Their general foraging pattern (e.g., control plots) primarily involved forward-directed movement with some lateral turns. Search paths were relatively straight, while step lengths and move durations commonly were of an intermediate magnitude. Both step-length sequences and turn-angle sequences were structured (i.e., lag correlated; Table 3) indicating that A. uniparens does not strictly follow a random path when foraging.

On uniform plots supplemental food was evenly spaced. Once food is encountered, models predict that foragers should travel long distances before resuming searches [24,25]. In practice, animals can develop a strategy involving periods of directed, long relocation when prey is uniformly distributed [21,45], as did A. uniparens, which exhibited a higher frequency of long step lengths under the uniform prey distribution compared with the other prey distribution treatments. In opposition to search strategies on uniform plots, whiptails on aggregated plots had fewer than expected long step lengths, with individuals intensively searching some areas as evidenced by short step lengths and short move durations. Further, the moves of short duration exhibited by whiptails on aggregated plots led to more frequent pauses over the same search time. The combination of short move durations and short step lengths is consistent with area-restricted searching [21,45], which was characterized by making many moves in one area on aggregated plots.

When foraging on plots with a random distribution of prey, not enough information is available to foragers to improve search success. With randomly distributed prey, an optimal search strategy minimizes the extent that an area is revisited after an unsuccessful search (through long move durations and long step lengths) and maximizes the number of new areas that can be observed at each pause (by exhibiting convoluted search paths with low straightness). The combination provides a balance of local and global exploration [73,74]. Consistent with theoretical predictions, A. uniparens on plots with a random distribution of prey moved along more convoluted routes with relatively longer move durations than whiptails in the uniform treatments [19,73].

Many studies of search strategies either focus on animals searching for a single type of food or predict that foragers will specialize on a particular type of prey based on relative costs and benefits [13,19,69]. However, foraging animals often exhibit mixed behavioral modes such that the optimal strategy for a single behavior is not realized [75]. Our animals fit neither scenario, as they use a blended search strategy, wherein they pursue and consume multiple natural prey types. Consequently, whiptails on our experimental plots adjusted their search strategy to the distribution of a novel food type while still being influenced by naturally occurring food sources. Mealworms were a supplemental food but not a necessary addition to their diet. In fulfilling their need for nutritional balance while avoiding predators and maintaining appropriate thermoregulation, we recorded small quantitative differences between treatments, as opposed to qualitatively different search strategies that might be expected from lizards limited to the distributions of a single prey type. If whiptails adapted the optimal strategy associated with the specific mealworm distribution, more dramatic differences between the treatments might have occurred. Finally, differences in search paths can be related to other aspects of whiptail ecology. For example, differences in step length-turn angle combinations could lead to differences in predation risk [76,77]. Experimental manipulation of predation risk in A. uniparens resulted in shifts to activity periods [78], which in turn could affect access to prey, thus requiring a broader characterization of the components of an optimal search strategy.

5. Conclusions

The response of A. uniparens to a novel prey source demonstrates flexibility in how their search strategy is structured and an ability to behaviorally respond to a changing environment. The ability to vary search strategies to enhance search efficiency could be useful in adapting to extreme changes in habitat and food availability [79,80]. Behavioral flexibility in searching for food, and more generally behaviorally responding to change, are cognitive traits that are useful for survival in unpredictable environments [52]. Our study offers some ecologically relevant insight into the cognitive ability of free-ranging saltatory foragers and their potential to adapt to changing environments, as evidenced by their efficiency in varying their search strategies to the distribution of novel prey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.E. and M.A.E.; methodology, D.A.E., M.C.S., D.F.W. and M.A.E.; validation, D.A.E.; formal analysis, D.A.E. and M.M.O.; investigation, D.A.E., M.C.S., D.F.W. and M.A.E.; resources, D.A.E. and M.A.E.; data curation, D.A.E. and M.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.E., M.C.S., D.F.W., M.M.O. and M.A.E.; writing—review and editing, D.A.E., M.C.S., D.F.W. and M.A.E.; visualization, D.A.E., M.M.O. and M.A.E.; supervision, D.A.E. and M.A.E.; project administration, D.A.E. and M.A.E.; funding acquisition, D.A.E. and M.A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Our work was funded by EarthWatch, the Durfee Foundation, and the Southwestern Research Station of the American Museum of Natural History.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We complied with all applicable laws and permits of the United States of America, conforming to the ethical guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioral research articulated by the Animal Behaviour Society and the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Allen, K. Bott, R. Drysdale, M Gatewood, A. Goodale, S. Johnstone, C. Jones, S. Peacock, and H. Zeune for assistance with the fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARS | Area-restricted searching |

| MPM | Moves per minute |

| PTM | Percent time moving |

References

- Bartumeus, F.; Catalan, J.; Viswanathan, G.M.; Raposo, E.P.; da Luz, M.G.E. The influence of turning angles on the success of non-oriented animal searches. J. Theor. Biol. 2008, 252, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thums, M.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Hindell, M.A. In situ measures of foraging success and prey encounter reveal marine habitat-dependent search strategies. Ecology 2011, 92, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S.M.; McBrayer, L.B.; Miles, D.B. (Eds.) Lizard Ecology: The Evolutionary Consequences of Foraging Mode; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, D.W.; Brown, J.S.; Ydenberg, R.C. (Eds.) Foraging: Behavior and Ecology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, A.M.; Hewitt, D.G.; DeYoung, R.W.; Schnupp, M.J.; Hellickson, M.W.; Lockwood, M.A. Reproductive effort and success of males in scramble-competition polygyny: Evidence for trade-offs between foraging and mate search. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 1600–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.W.; Southall, E.; Humphries, N.; Hays, G.C.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Pitchford, J.W.; James, A.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Brierley, A.S.; Hindell, M.A.; et al. Scaling laws of marine predator search behavior. Nature 2008, 451, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.Y.; Baranov, E.A.; Miyazaki, N. Experience-based optimal foraging on planktonic prey in baikal seals. Mov. Ecol. 2025, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Pacheco-Cobos, L.; Winterhalder, B. A general model of forager search: Adaptive encounter-conditional heuristics outperform levy flights in the search for patchily distributed prey. J. Theor. Biol. 2018, 455, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regular, P.M.; Hedd, A.; Montevecchi, W.A. Must marine predators always follow scaling laws? Memory guides the foraging decisions of a pursuit-diving seabird. Anim. Behav. 2013, 86, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, T. Emergence of adaptive global movement from a subjective inference about local resource distribution. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, N.E.; Sims, D.W. Optimal foraging strategies: Levy walks balance searching and patch exploitation under a very broad range of conditions. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 358, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palyulin, V.V.; Chechkin, A.V.; Metzler, R. Levy flights do not always optimize random blind search for sparse targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2931–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartumeus, F.; da Luz, M.G.E.; Viswanathan, G.M.; Catalan, J. Animal search strategies: A quantitative random-walk analysis. Ecology 2005, 86, 3078–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Mateo, J.; Benavent-Corai, J.; Lopez-Lopez, P.; Garcia-Ripolles, C.; Mellone, U.; De la Puente, J.; Bermejo, A.; Urios, V. Search foraging strategies of migratory raptors under different environmental conditions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 666238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louâpre, P.; le Lann, C.; Hance, T. When parasitoids deal with the spatial distribution of their hosts: Consequences for both partners. Insect Sci. 2019, 26, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboelpaep, E.; Pint, S.; Koedam, N.; Van der Stocken, T.; Vanschoenwinkel, B. Horizontal prey distribution determines the foraging performance of short- and long-billed waders in virtual resource landscapes. Ibis 2024, 166, 1041–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartumeus, F.; Raposo, E.P.; Viswanathan, G.M.; da Luz, M.G.E. Stochastic optimal foraging: Tuning intensive and extensive dynamics in random searches. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimienti, M.; Barton, K.A.; Scott, B.E.; Travis, J.M.J. Modelling foraging movements of diving predators: A theoretical study exploring the effect of heterogeneous landscapes on foraging efficiency. PeerJ 2014, 2, e544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollner, P.A.; Lima, S.L. Search strategies for landscape-level interpatch movements. Ecology 1999, 80, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhumberg, B.; Keller, M.A.; Tyre, A.J.; Possingham, H.P. The effect of resource aggregation at different scales: Optimal foraging behavior of Cotesia rubecula. Am. Nat. 2001, 158, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, K.A.; Hovestadt, T. Prey density, value, and spatial distribution affect the efficiency of area-concentrated search. J. Theor. Biol. 2013, 316, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, N.E.; Queiroz, N.; Dyer, J.; Pade, N.G.; Musyl, M.K.; Schaefer, K.M.; Fuller, D.W.; Brunnschweiler, J.M.; Doyle, T.K.; Houghton, J.D.R.; et al. Environmental context explains Lévy and Brownian movement patterns of marine predators. Nature 2010, 465, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, G.M.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Havlin, S.; da Luz, M.G.E.; Raposo, E.P.; Stanley, H.E. Optimizing the success of random searches. Nature 1999, 401, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, Y.; Higashi, M.; Yamamura, N. Prey distribution as a factor determining the choice of optimal foraging strategy. Am. Nat. 1981, 117, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell, D.G. Experiments and a model examining learning in the area-restricted search behavior of ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Behav. Ecol. 1997, 8, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, W.C.; Ritchie, M.E. Influence of prey distribution on the functional response of lizards. Oikos 2002, 96, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.J.; Browman, H.I.; Evans, B.I. Search strategies of foraging animals. Am. Sci. 1990, 78, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, R.A. Experimental analysis of lizard pause-travel movement: Pauses increase probability of prey capture. Amphibia-Reptilia 1993, 14, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, G. Movement patterns in lizards: Measurement, modality, and behavioral correlates. In Lizard Ecology; Reilly, S.M., McBrayer, L.B., Miles, D.B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baatrup, E.; Rasmussen, A.O.; Toft, S. Spontaneous movement behaviour in spiders (Araneae) with different hunting strategies. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 2018, 125, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennice, C.O.; Brooks, W.R.; Hanlon, R.T. Behavioral dynamics provide insight into resource exploitation and habitat coexistence of two octopus species in a shallow Florida lagoon. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2021, 542, 151592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.K.; Carton, A.G.; Montgomery, J.C. Saltatory search in a lateral line predator. J. Fish. Biol. 2007, 70, 1148–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M. On optimal predator search. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1981, 19, 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getty, T.; Pulliam, H.R. Random prey detection with pause-travel search. Am. Nat. 1991, 138, 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.P.; Stephens, D.W.; Dunbar, S.R. Saltatory search: A theoretical analysis. Behav. Ecol. 1997, 8, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.M.; Bala, S.I. Plankton predation rates in turbulence: A study of the limitations imposed on a predator with a non-spherical field of sensory perception. J. Theor. Biol. 2006, 242, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.I.; O’Brien, W.J. A reevaluation of the search cycle of planktivorous artic grayling, Thymallus arcticus. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1988, 45, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.J.; Evans, B.I.; Browman, H.I. Flexible search tactics and efficient foraging in saltatory searching animals. Oecologia 1989, 8, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.M.; Bala, S.I. An examination of saltatory predation strategies employed by fish larvae foraging in a variety of different turbulent regimes. Mar. Ecol-Prog. Ser. 2008, 359, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, T.; Costa, D.P.; Robinson, P.W.; Peterson, S.H.; Yamamichi, M.; Naito, Y.; Takahashi, A. Searching for prey in a three-dimensional environment: Hierarchical movements enhance foraging success in northern elephant seals. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 31, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, T.; Katayama, N. Hierarchical movement decisions in predators: Effects of foraging experience at more than one spatial and temporal scale. Ecology 2009, 90, 3536–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildhaber, M.L.; Green, R.F.; Crowder, L.B. Bluegills continuously update patch giving-up times based on foraging experience. Anim. Behav. 1994, 47, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, R.H.G.; Nolet, B.A.; Van Leeuwen, C.H.A. Prior knowledge about spatial pattern affects patch assessment rather than movement between patches in tactile-feeding mallard. J. Anim. Ecol. 2007, 76, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.; Burrows, M.T.; Hughes, R.N. Adaptive search in juvenile plaice foraging for aggregated and dispersed prey. J. Fish. Biol. 2002, 61, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, A.; Hills, T.T.; Scharf, I. A guide to area-restricted search: A foundational foraging behaviour. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 2076–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakauer, D.C.; Rodríguez-Gironés, M.A. Searching and learning in a random environment. J. Theor. Biol. 1995, 177, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifler, D.A.; Baipidi, K.; Eifler, M.A.; Dittmer, D.; Nguluka, L. Influence of prey encounter and prey identity on area-restricted searching in the lizard Pedioplanis namaquensis. J. Ethol. 2012, 30, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, T.; Brockie, P.J.; Maricq, A.V. Dopamine and glutamate control area-restricted search behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Cobos, L.; Winterhalder, B.; Cuatianquiz-Lima, C.; Rosetti, M.F.; Hudson, R.; Ross, C.T. Nahua mushroom gatherers use area-restricted search strategies that conform to marginal value theorem predictions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10339–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolting, B.C.; Hinkelman, T.M.; Brassil, C.E.; Tenhumberg, B. Composite random search strategies based on non-directional sensory cues. Ecol. Complex. 2015, 22, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C.J. Increased olfactory search costs change foraging behavior in alien mustelid: A precursor to prey switching? Oecologia 2016, 182, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, B.; Noble, D.W.A.; Whiting, M.J. Learning in non-avian reptiles 40 years on: Advances and promising new directions. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, R.B.; Pianka, E.R. Ecological consequences of foraging mode. Ecology 1981, 62, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.E., Jr. Duration of movement as a lizard foraging movement variable. Herpetologica 2005, 61, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.E. Foraging modes as suites of coadapted movement traits. J. Zool. 2007, 272, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donihue, C.M. Aegean wall lizards switch foraging modes, diet, and morphology in a human-built environment. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 7433–7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.P.J.; DeNardo, D.F.; Angilletta, M.J. The correlated evolution of foraging mode and reproductive effort in lizards. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2022, 289, 20220180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsumi, K.; Kusaka, C.; Pedersen, R.; Staley, C.; Dunlap, L.; Gilbert Smith, S.; Eifler, M.A.; Eifler, D.A. Habitat dependent search behavior in the Colorado checkered whiptail lizard (Aspidoscelis neotesselata). West. N. Am. Nat. 2020, 80, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehsener, J.W.; Noss, C.F. Disentangling morphological and environmental drivers of foraging activity in an invasive diurnal gecko, Phelsuma laticauda. J. Herpetol. 2022, 56, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, R.S.; Loarie, S.R.; Colchero, F.; Best, B.D.; Boustany, A.; Conde, D.A.; Halpin, P.N.; Joppa, L.N.; McClellan, C.M.; Clark, J.S. Understanding movement data and movement processes: Current and emerging directions. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kays, R.; Crofoot, M.C.; Jetz, W.; Wikelski, M. Terrestrial animal tracking as an eye on life and planet. Science 2015, 348, a2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelhoff, H.; Signer, J.; Balkenhol, N. Path segmentation for beginners: An overview of current methods for detecting changes in animal movement patterns. Movement Ecol. 2016, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchald, P.; Erikstad, K.E.; Skarsfjord, H. Scale-dependent predator-prey interactions: The hierarchical spatial distribution of seabirds and prey. Ecology 2000, 81, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine-Bellis, E.; Utsumi, K.; Diamond, K.; Klein, J.; Gilbert-Smith, S.; Garrison, G.; Eifler, M.; Eifler, D. Movement patterns and habitat use for the sympatric species Gambelia wislizenii and Aspidoscelis tigris. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eifler, D.A. Experimental manipulation of spacing patterns in the widely foraging lizard Cnemidophorus uniparens. Herpetologica 1996, 52, 477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Eifler, D.A.; Eifler, M.A. Foraging behavior and spacing patterns of the lizard Cnemidophorus uniparens. J. Herpetol. 1998, 32, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifler, D.A.; Passak, K. Body size effects on pursuit success and interspecific diet differences in Cnemidophorus lizards. Amphibia-Reptilia 2000, 21, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifler, D.A.; Smith, E. Patch use by foraging whiptail lizards (Aspidoscelis uniparens). Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2007, 19, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.E.; Wiens, J.A. Interactions between landscape structure and animal behavior: The roles of heterogeneously distributed resources and food deprivation on movement patterns. Landscape Ecol. 1999, 14, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodda, G.H.; Bock, B.C.; Burghardt, G.M.; Rand, A.S. Techniques for identifying individual lizards at a distance reveal influences of handling. Copeia 1988, 1988, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolker, B.M. Ecological Models and Data in R; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, M.L. Random search by herbivorous insects: A simulation model. Ecology 1985, 66, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartumeus, F.; Catalan, J. Optimal search behavior and classic foraging theory. J. Phys. A-Math. Theor. 2009, 42, 434002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, T.; Gunji, Y.-P. Optimal random search using limited spatial memory. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, O.; Harel, R.; Centeno-Cuadros, A.; Hatzofe, O.; Getz, W.M.; Nathan, R. Moving beyond curve fitting: Using complementary data to assess alternative explanations for long movements of three vulture species. Am. Nat. 2015, 185, E44–E54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.M. Balancing the competing demands of harvesting and safety from predation: Levy walk searches outperform composite Brownian walk searches but only when foraging under the risk of predation. Physica A 2010, 389, 4740–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, C.C.; Carvalho, L.A.B.; Budleigh, C.; Ruxton, G.D. Virtual prey with Levy motion are preferentially attacked by predatory fish. Behav. Ecol. 2023, 34, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eifler, D.A.; Eifler, M.A.; Harris, B. Foraging under the risk of predation in desert grassland whiptail lizards, Aspidoscelis uniparens. J. Ethol. 2008, 26, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, H.B.; Pfaller, J.B.; Sheehy, C.M. Feeding preferences and responses to prey in insular neonatal Florida cottonmouth snakes. J. Zool. 2015, 297, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumroeder, J.; Eccard, J.A.; Blaum, N. Behavioral flexibility in foraging mode of the spotted sand lizard (Pedioplanis l. lineoocellata) seems to buffer negative impacts of savanna degradation. J. Arid Environ. 2012, 77, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.