Abstract

The Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) is a migratory game bird of ecological, cultural, and hunting importance in Europe. While globally listed as Least Concern, concerns remain over hunting pressure and limited ecological data. In Hungary, the species occurs regularly during spring and autumn migration and breeds in low numbers. To provide evidence-based management, the Hungarian Woodcock Monitoring Program was launched in 2009. This study evaluates spatial and temporal patterns of woodcock presence in Hungary using standardized roding surveys conducted between 2009 and 2024. Observations were assigned to 10 × 10 km grid cells, with 180 cells consistently sampled over the 16-year period. Detection rates were analyzed, defining “high-abundance” as five or more individuals recorded per session. Interannual dynamics were tested using correlation analyses, and spatial clustering was assessed with spatial autocorrelation. Woodcocks were detected in an average of 94.38% of surveyed cells annually (±3.88% SD), indicating a stable and widespread presence. High-abundance detections were lower ( = 50.56%) and more variable (±10.71% SD) but consistently concentrated in specific areas, highlighting the importance of regional stopover habitats. No significant long-term trend was observed, suggesting population stability. These results confirm Hungary’s key role in the spring migration corridor and underline the value of long-term monitoring for reconciling traditional hunting with conservation objectives.

1. Introduction

The Eurasian Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola, Linnaeus, 1758) is a cryptic, medium-sized wader species distributed across the Western Palearctic. It is known for its unique combination of morphological, ecological, and behavioral adaptations [1,2]. With a long, flexible bill for probing soil and large lateral-set eyes suited for nocturnal activity, the woodcock is specialized for foraging in moist woodland habitats rich in earthworms and soil invertebrates [1,3]. These characteristics, coupled with its secretive and crepuscular behavior, make the Eurasian woodcock particularly difficult to detect in the field. One of its most distinctive behaviors is the male’s display during the breeding season, performed at dawn and dusk to attract females through a combination of flight loops and characteristic calls [4,5,6]. These displays, while behaviorally significant, also provide a good opportunity for population monitoring [1,3].

The species exhibits partial migratory behavior, with migratory strategies varying by geography. Some populations in southern and western Europe remain sedentary, while birds from Scandinavia, Eastern Europe, and Western Siberia migrate over thousands of kilometers to milder wintering grounds, primarily in Western and Southern Europe [7,8]. Migration typically occurs at night and is guided by a combination of endogenous rhythms and environmental factors such as seasons, temperature, barometric pressure, and wind conditions [9,10,11]. Satellite telemetry and ringing studies have demonstrated that woodcocks exhibit flexibility in their migratory routes and stopover site use, responding to environmental conditions such as soil moisture, snow cover, and land use [12,13]. The species’ dependence on soil invertebrates makes it particularly vulnerable to drought, cold spells, and land-use change, all of which can restrict access to critical resources during migration and winter [1,14]. In recent years, global climate change has introduced further complexity to the species’ migratory patterns. Shifts in temperature and precipitation across Europe may affect the timing and direction of woodcock migrations, potentially contributing to variability in arrival dates and stopover durations [10]. Shifts in temperature and precipitation across Europe have been shown to influence both the timing and the direction of woodcock migrations, leading to increased variability in arrival dates and stopover durations [10]. Advances in satellite telemetry and GPS tagging have helped clarify these dynamics. For instance, satellite-tagged individuals from Hungary have been tracked to breeding sites such as Russia [4,5], with some altering their routes in response to climate anomalies or anthropogenic habitat fragmentation [12], while bird ringing data have also revealed similar long-distance movements and regional connectivity patterns [15]. These data emphasize the importance of central Europe as both a transit and refueling zone, particularly during spring migration.

Habitat use by the Eurasian woodcock varies seasonally, which reflects the shifting energetic and ecological requirements. During the breeding season, woodcocks favor undisturbed deciduous or mixed forests with dense undergrowth and modest human disturbance, particularly younger forest stands that offer optimal cover and prey density [6,16,17]. During non-breeding periods, especially at the times of migration and winter, woodcocks expand their habitat use to include adjacent agricultural fields, pastures, and forest edges where prey availability is high. Foraging often occurs at night in open areas, with birds returning to denser vegetation for cover during the day [1,18]. Foraging is strongly tied to soil characteristics such as temperature, habitat structure, and moisture levels, which influence the availability of earthworms [19]. These diurnal movements are especially critical during cold months when earthworm availability in forested soil declines. In Hungary, a mosaic landscape comprising forest and open-field habitats appears to provide suitable conditions for migrating individuals, particularly in March and April when migratory energy demands are high [14].

Although monitoring challenges persist due to the species’ nocturnal and elusive nature, it is globally listed as a species of Least Concern [20]. The Eurasian woodcock has experienced regional declines in certain parts of western and central Europe, notably in the United Kingdom, where the breeding population has declined significantly, with a 74% reduction reported between 1968 and 1999 [12,21]. Similar declines have been observed in resident populations in Switzerland (notably the Jorat forest in Vaud) and parts of central Europe such as Germany, Austria, and Poland [3,5,22], with habitat loss, changing forest structure, and increased human disturbance, such as agricultural development, identified as key drivers. Conversely, woodcock populations in parts of central and eastern Europe appear more stable, likely due to larger forested landscapes and lower land-use pressure [5,23].

In Hungary, the woodcock is of particular interest due to its hunting-cultural significance and legal controversy. While the species is a rare breeder in the country, it is consistently observed during spring migration, primarily between late February and mid-April, aligning with the roding period. Roding refers to the crepuscular display flight which is performed by males, often accompanied with distinct whistling and croaking sounds [15,24,25]. Hungarian hunters have historically pursued woodcocks during their roding displays, a practice that has been passed down for generations [15,26]. However, this tradition has sparked controversy due to the European Union’s Bird Directive (79/409/EEC), which prohibits the hunting of birds during their breeding periods, including the migration to the breeding areas. To address this issue, the Hungarian Woodcock Monitoring Program was established in 2009, aiming to reconcile tradition with sustainability through science-based or evidence-based management [27]. This nationwide initiative seeks to collect long-term data on woodcock presence, abundance, and population structure through standardized observation protocols and the monitoring of strictly controlled hunting bags. Participation is voluntary and coordinated through regional hunting associations, with observers submitting data on detection rates, weather, land cover, and sampling effort. For each harvested woodcock, data on location, date, time, body weight, and body length were recorded. In addition to visual and auditory surveys, hunters are required to collect wing and muscle samples from harvested birds to facilitate sex and age classification [3] and, more recently, genetic analysis [28]. This was done by distinguishing between first-year and adult individuals based on molt patterns. The tissue samples are also to support population genetic studies, which aim to assess the breeding origin and connectivity of woodcocks migrating through Hungary. The tissue samples again provide important background context for the broader aim of the monitoring Program. This integrative approach enables both population-level inference on the conservation status of populations and the evaluation of hunting impacts over time, as well as broader European monitoring efforts [19,29]. Hungary, a migratory crossroads, offers a unique opportunity to study large-scale avian movements at a landscape scale. Long-term standardized monitoring has proven effective for evaluating spatial patterns and temporal trends in several European countries, including France, the UK, and Italy [3,29,30]. When appropriately standardized and critically analyzed, citizen science contributions, especially from trained and regulated participants, can yield scientifically robust conclusions about migratory bird trends [19,30]. Hungary’s contribution to this network strengthens continental-scale understanding of woodcock ecology.

Given the Eurasian woodcock’s ecological and cultural importance in Hungary, and the country’s position within the species’ migratory flyways, there is a critical need for spatially and temporally explicit data to guide adaptive conservation strategies. Identifying the most favorable habitats and evaluating how these areas change over time can inform both national policy and transboundary wildlife management efforts. Furthermore, understanding annual variation in abundance can help determine whether current hunting practices remain within sustainable limits, especially as climate and land use change continue to reshape Europe’s ecological landscape.

This study aims to address these challenges by utilizing comprehensive data collected between 2009 and 2024. Specifically, the objectives are to:

- Describe the spatial distribution of Eurasian woodcock presence in Hungary during the spring migration period.

- Evaluate long-term trends of woodcock presence and abundance across the 16-year study period.

- Identify regional ecological hotspots that may function as key stopover areas.

By integrating ecological, spatial, and policy-relevant perspectives, this research contributes to the broader understanding of woodcock migration ecology in Central Europe and supports evidence-based wildlife management that balances conservation goals with traditional land-use practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Monitoring Program and Data Collection

The data analyzed in this study were derived from the Hungarian Woodcock Monitoring Program [15], initiated in 2009 to support the sustainable management of the species and to address conservation concerns related to traditional spring hunting. The Program is nationally coordinated through the Hungarian Hunters National Association, in partnership with the Hungarian Ministry of Agriculture and the Department of Wildlife Biology and Conservation of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences. The monitoring integrates standardized roding surveys, sample-based detections, and hunting bag monitoring. Participation was restricted to licensed hunters operating under official permits. Between 2010 and 2024, woodcock hunting during the spring migration period was allowed only for Program participants, who were required to comply with regulated sampling protocols. The Hungarian Woodcock Monitoring Program is a continuous program which is conducted annually following standardized observation protocols across Hungary.

2.2. Roding Surveys and Sampling Design

Roding surveys were conducted weekly during spring migration, between calendar weeks 6 and 18, corresponding to mid-February through late April. Observations were conducted every Saturday evening, starting approximately 30 min before sunset and lasting for at least one hour. Observers selected fixed sites and recorded data using standardized paper forms. The observation point selection was based on accessibility, knowledge of local habitat suitability, and historical knowledge woodcock observations. Information collected included the number of woodcocks seen and heard, date and time, weather conditions, land cover, duration of observation, estimated size of the observed area, and precise geographical coordinates of each point. To ensure consistency and reduce spatial redundancy in our study, each 10 × 10 km grid cell across Hungary included only one representative observation point, specifically, the site with the highest number of detections. In total, 180 grid cells were selected based on strict criteria: each cell had to contain complete annual data from 2009 to 2024 and include survey data during the peak detection week (the week when the number of detections was the highest in a given year), typically mid-March.

2.3. Definition of Detection Categories

Survey data were categorized into two detection levels. A positive detection was defined as any instance in which at least one woodcock was visually observed during a survey. High-abundance sites were defined as those where five or more individuals were recorded during a single observation session. This threshold aligns with definitions established in European woodcock monitoring protocols, allowing for meaningful comparisons across regions and time periods. Detection rates were standardized by calculating the proportion of positive or high-abundance observation sites relative to the total number of sites (n = 180) which conducted surveys at each annual peak date. Only visual sightings were included in these calculations; detections based solely on calls were excluded to ensure consistency in detection methodology.

2.4. Statistical and Spatial Analysis

All data were digitized and processed using Microsoft Access and Excel 365. Statistical analyses were conducted using PAST (version 5.0). Descriptive statistics, including minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation, were calculated for both positive and high-abundance detections. Pearson’s correlation tests were applied to examine the relationships between detection categories and time. Spatial analyses were carried out using QGIS (version 3.34). The primary spatial layer used for analysis consisted of 10 × 10 km grid cells representing the Hungarian territory. Moran’s I was used to assess spatial autocorrelation and clustering in detection patterns. The variable tested was the number of years each grid cell exhibited positive or high-abundance detections. To evaluate spatial structure, grid-cell pairs were grouped into distance-based classes (‘Lag classes’) corresponding to specified spatial interval. For each class, the mean geographic distance between all included grid-cells pairs was calculated, and this is labeled as ‘Average dist.’ This structure was used to examine changes in spatial autocorrelation across increasing spatial scales. The analysis identified areas of significant clustering, randomness, or dispersion, and helped highlight regions of particular ecological importance for the species. All statistical significance were assessed using a standard alpha level of 0–0.05 unless otherwise specified. To account for variability in observer effort and reduce sampling bias, only standardized detection proportions were used in all spatial and statistical evaluations. This ensured that comparisons were not influenced by unequal numbers of observers or varying observation durations across years or sites.

3. Results

3.1. General Detection Patterns (2009–2024)

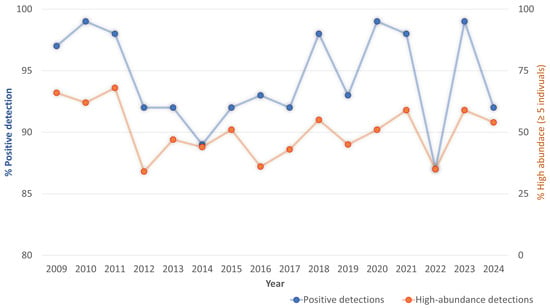

Over the 16 years from 2009 to 2024, the Eurasian woodcock was detected in the vast majority of survey locations across Hungary. Among the 180 grid cells with complete annual data, the average percentage of cells with at least one visual detection of woodcock per year was 94.38% (±3.88 SD). This indicates a consistently high national presence during the spring migration period. In contrast, high-abundance detections were less frequent and more variable (Figure 1). The annual percentage of high-abundance cells ranged from 34% to 68%, with a mean of 50.56% (±10.71 SD). The greatest proportion of high-abundance sites was recorded in 2015, while the lowest occurred in 2021. The yearly proportion of positive and high abundance detections changed considerably throughout the study period with several noticeable peaks and troughs observable across the years (Figure 1). These fluctuations highlight the long-term variability in the number of woodcock individuals as a stopover site during spring and autumn migration.

Figure 1.

Annual proportion of grid cells with positive woodcock detections (solid blue line, left Y-axis) and high-abundance detections (≥5 individuals; dashed red line, right Y-axis) during spring migration monitoring in Hungary (2009–2024).

Temporal Trends in Detection

No significant temporal trend was found in the annual proportion of grid cells with positive detections across the 16 years (Pearson’s r = −0.10, p = 0.71), suggesting a stable presence of woodcock during spring migration in Hungary. Similarly, the proportion of high-abundance detections did not show a significant trend over time (Pearson’s r = −0.20, p = 0.46), although interannual variability was more evident (Figure 1). The most consistent year-to-year values were seen in positive detections, which remained above 90% in all survey years. In contrast, the percentage of high-abundance detections exhibited greater annual fluctuation.

3.2. Spatial Pattern of Detections

According to the results of the spatial correlation analysis regarding the positive cells, there was a significant spatial clustering at short distances (Lag 1), and again at longer distances (Lag 8). In between, the pattern became weaker (Lags 5 and 7), suggesting alternating clustering and dispersion as distance increases. This pattern (positive-negative-positive) can indicate multiple scales of spatial autocorrelation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the spatial autocorrelation analysis—Positive cells. Spatial autocorrelation results for spring detections. “Lag class” refers to the spatial distance intervals between grid-cells pairs used in the analysis, and “Average dist.” represents the mean pairwise distance (km) between cells within each lag class.

According to the results of the spatial correlation analysis regarding the high abundance cells, strong, significant clustering was present at short and mid-range distances (Lags 1 and 2). After that, the Moran’s I values declined and became insignificant. At Lag 5, a significant negative Moran’s I suggests spatial dispersion. Beyond Lag 5, the spatial structure became weak or non-existent. This result also shows a multi-scale spatial structure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the spatial autocorrelation analysis—High abundance cells. Spatial autocorrelation results for spring high abundance detections. “Lag class” indicates the distance classes applied in the spatial analysis. “Average dist.” shows the average pairwise distance (km) between grid-cells pairs included in each class.

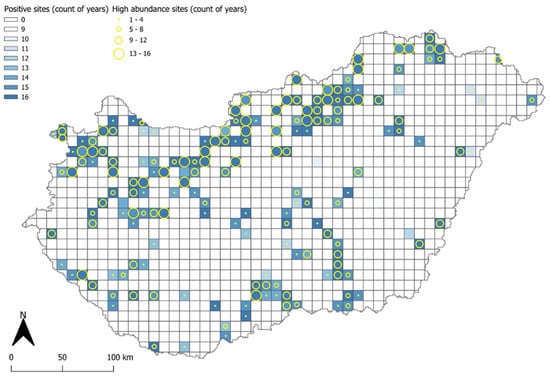

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial distribution of Eurasian woodcock detections across the 180 grid cells in Hungary, the annual proportion of grid cells with positive detections, and high-abundance detections from 2009 to 2024. Cells are color-coded based on the number of years in which high-abundance detections (≥5 individuals) occurred between 2009 and 2024. Several regions, particularly in western and northeastern Hungary, consistently exhibited high abundance, including areas near the Őrség National Park, the Bükk Mountains, and the Zemplén Hills (Figure 2). These spatial concentrations suggest the presence of favorable habitat conditions for migrating woodcock and emphasize the ecological significance of these regions as persistent stopover sites.

Figure 2.

Spatial frequency of positive detection sites (2009–2024) and spatial distribution of the high-abundance detection sites.

The map confirms the overall stability of positive detections over the study period, with rates consistently above 90%. In contrast, the percentage of high-abundance detections fluctuated more substantially from year to year. While no clear increasing or decreasing trend was observed, peaks in high-abundance years (e.g., 2012, 2015, and 2019) may reflect variations in migratory intensity or favorable seasonal conditions that influence detection rates and stopover use. Positive detections were geographically widespread, with nearly all regions of Hungary showing consistent woodcock presence. However, grid cells in western and northeastern Hungary, particularly those in the forested areas such as Őrség and the Zemplén Mountains, showed higher frequencies of high-abundance detections over multiple years. To further explore spatial consistency, the number of years with high-abundance detections was calculated for each grid cell. Several locations recorded high-abundance detections in 12 or more years out of 16, indicating persistent local aggregation. These high-consistency sites were concentrated in areas characterized by mixed woodland habitats, gentle topography, and relatively low human disturbance.

4. Discussion

This long-term study revealed a stable presence of Eurasian woodcock in Hungary during the spring migration period. Across 16 years, the consistently high proportion of grid cells with detections indicates that Hungary functions as a reliable migratory corridor within the Central European flyway [15]. These findings are consistent with previous studies emphasizing the vital role of Central Europe in large-scale woodcock movements [7]. Similar findings from ringing and GPS-tracking studies suggest that Hungary serves as both a stopover and passage zone [12]. Although detections were geographically widespread, high-abundance observations were not evenly distributed. Grid cells in forested regions such as the Zemplén Hills, Őrség, and the Bükk Mountains consistently recorded higher numbers of individuals. These areas are characterized by dense woodland, moist soils, and low human disturbance, features that are known to support the woodcock’s foraging and sheltering needs [1,6]. The recurrence of these high-abundance areas across multiple years suggests that they may function as essential migratory stopovers. Studies from France and Italy have similarly identified forest habitat quality as a key driver of spring woodcock aggregation [19,29]. The spatial clustering observed in western Europe and northeastern Hungary may be impacted by ecological factors like habitat structure, soil moisture availability or even landscape connectivity [15]. Regardless of these factors being plausible, as drivers of woodcock stopover selection, further targeted analyses are required to identify the specific mechanisms shaping these patterns.

No significant trend was observed in either presence or abundance over time, indicating relative population stability within Hungary. However, this contrasts with notable declines in breeding populations in western Europe, including the United Kingdom and Switzerland, where changes in land use and reduced breeding success have been linked to long-term population reductions [3,21]. Instead, the trends in this study align with those observed in woodcock populations in eastern and central Europe, where the populations appear to be more stable, likely due to the persistence of suitable woodland habitats and reduced anthropogenic pressure [5,23]. However, the birds recorded in Hungary during spring migration predominantly originate from northeastern breeding [13] populations mostly from Russia and the Baltic states. Therefore, any interpretation of Hungarian spring migration detections should be made in relation to fluctuations within these source population and not the broader European breeding trends.

However, greater interannual variability in high-abundance detections suggests that certain environmental factors may influence these counts. Climate-related conditions, including soil moisture and temperature, are known to influence woodcock foraging efficiency and migration patterns [1,11]. For instance, in particularly wet or mild springs, earthworm availability increases, potentially attracting more individuals to specific stopover sites. Fluctuations could also reflect breeding success from the previous year, a factor influencing spring population pressure [3]. Interannual variation in high-abundance detections likely reflects changes in the productivity and population size of eastern and northeastern European breeding populations instead of local environmental factors. Those include populations in Russian, and the Baltic region. Years with stronger breeding output in these northern areas would likely result in higher numbers of migrants stopping over Hungary, whereas poor breeding seasons would result in lower detections regardless of stable local conditions [15]. Alternatively, variation in observer effort or weather during surveys could influence detectability, as has been noted in other citizen science-based monitoring schemes [31].

The results of Moran’s I spatial autocorrelation analysis confirm that high-abundance detections are significantly clustered, not randomly distributed. This supports the hypothesis that certain regions possess characteristics that consistently attract migrating woodcock [32]. These spatial patterns are similar to findings observed in France and Italy, where woodcocks display site fidelity to preferred stopover habitats across years [19]. Identifying specific features, such as forest structure, food availability, or terrain, is crucial in guiding habitat conservation and management efforts.

These findings support the importance and value of Hungary’s Woodcock Monitoring Program, because the Program has proven to be effective not only for ecological value but also for wildlife management. By relying on structured, standardized data collection through licensed observers, the Program has built a long-term dataset capable of informing evidence-based decisions. This approach mirrors similar Programs in France and the UK, where roding surveys and biological sampling have informed national population assessments [3,30]. Although this study was centered around the spring migration, a comparable analysis of the autumn migration would be valuable for understanding seasonal differences in habitat use and migration dynamics. Currently, nationwide and long-term autumn monitoring data is limited or not available at similar spatial and temporal resolution. Future efforts for developing standardized monitoring protocols during the autumn season may help reveal whether the pattens observed in spring season, such as spatial clustering and overall detection stability, also occur later in the year.

Despite its strengths, the study had several limitations. Observer variability, weather conditions, and site access can affect detection probability. Although filtering for consistent effort helped reduce bias, regional differences in volunteer density may still influence spatial patterns [31]. Moreover, while visual detections are reliable, they are inherently limited by light conditions and forest density. The use of acoustic monitoring or automated recorders, which has proven to be effective in other cryptic bird species, could improve data quality in future studies. Similarly, expanding the use of satellite telemetry or geolocators could provide direct movement data to validate spatial assumptions [12].

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first long-term, nationwide assessment of spring migration patterns and habitat use of the Eurasian woodcock in Hungary, based on standardized field observations collected between 2009 and 2024. The consistently high rate of positive detections confirms that Hungary is a vital transit region along the species’ European flyway. Although the national-level presence of woodcock remained stable over time, the spatial distribution of high-abundance detections revealed persistent clustering in specific regions, suggesting the existence of critical stopover habitats [15]. These spatial patterns have direct conservation relevance, as they identify areas where migratory woodcocks concentrate and may therefore be more vulnerable to disturbance or habitat degradation. Protecting these regions through targeted management strategies, such as maintaining habitat quality in mixed-forest landscapes and limiting development or human disturbance during peak migration, could enhance the resilience of migratory populations [3]. The findings also support the continued value of Hungary’s Woodcock Monitoring Program as a tool for reconciling traditional hunting practices with modern conservation needs. By providing empirical evidence on population stability and habitat use, the Program contributes to both national wildlife policy and broader European conservation frameworks. Continued investment in monitoring, as well as the integration of new technologies and more detailed habitat data, will be critical for sustaining the species in the face of ongoing environmental change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K.M. and G.S.; methodology, I.K.M. and S.C.; software, I.K.M.; validation, M.N. and G.S.; formal analysis, I.K.M.; investigation, I.K.M. and M.N.; resources, S.C. and G.S.; data curation, I.K.M. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.M.; writing—review and editing, M.N., S.C. and G.S.; visualization, I.K.M.; supervision, S.C. and G.S.; project administration, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was based solely on field observations of Eurasian woodcock during roding counts. No animals were captured, handled, or experimentally manipulated. Data were collected by licensed hunters and volunteers under existing national wildlife regulations in Hungary.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The dataset forms part of the Hungarian Woodcock Monitoring Program (2009–2024) and is subject to data-sharing agreements with the Hungarian Hunters’ National Association.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the Hungarian Hunters’ National Association (Országos Magyar Vadászati Védegylet) and the Hungarian Ministry of Agriculture for their invaluable support of the Hungarian Woodcock Monitoring Program. Additionally, we acknowledge the support provided through the Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship Program, financed by the Government of Hungary and administered by the Tempus Public Foundation, which has supported Itumeleng Malatji Kwena and facilitated her PhD research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duriez, O.; Ferrand, Y.; Binet, F.; Corda, E.; Gossmann, F.; Fritz, H. Habitat Selection of the Eurasian Woodcock in Winter in Relation to Earthworms Availability. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 122, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramp, S.; Simmons, K.E.L. (Eds.) Handbook of the Birds of Europe the Middle East and North Africa: The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume 2: Hawks to Bustards; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1980; Volume 2, p. 913. ISBN 978-0-19-857506-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand, Y.; Gossmann, F. Elements for a Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) Management Plan. Game Wildl. Sci. 2001, 18, 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hoodless, A.N.; Lang, D.; Aebischer, N.J.; Fuller, R.J.; Ewald, J.A. Densities and Population Estimates of Breeding Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola in Britain in 2003. Bird Study 2009, 56, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heward, C.; Hoodless, A.; Conway, G.; Fuller, R.; Maccoll, A.; Aebischer, N. Habitat Correlates of Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola Abundance in a Declining Resident Population. J. Ornithol. 2018, 159, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoodless, A.; Hirons, G. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behaviour of Breeding Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola: A Comparison between Contrasting Landscapes. Ibis 2007, 149, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.L.; Ferrand, Y.; Arroyo, B. Origin and Migration of Woodcock Scolopax rusticola Wintering in Spain. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2011, 57, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauthian, I.; Gossmann, F.; Ferrand, Y.; Julliard, R. Quantifying the Origin of Woodcock Wintering in France. J. Wildl. Manag. 2007, 71, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.J. Timing of Bird Migration in Relation to Weather: Updated Review. In Bird Migration; Gwinner, E., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; pp. 78–101. [Google Scholar]

- Alerstam, T.; Hedenstrom, A. The Development of Bird Migration Theory. J. Avian Biol. 1998, 29, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alerstam, T. Optimal Bird Migration Revisited. J. Ornithol. 2011, 152, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, S.; Robinson, R.; Fiedler, W.; Arizaga, J.; Jiguet, F.; Nikolov, S.; van der Jeugd, H.P.; Franks, S. The Eurasian African Bird Migration Atlas—Documenting Migration and Movements Using Ringing and Tracking Data. Available online: https://pure.knaw.nl/portal/en/publications/the-eurasian-african-bird-migration-atlas-documenting-migration-a/ (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Schally, G.; Csányi, S.; Palatitz, P. Spring Migration Phenology of Eurasian Woodcocks Tagged with GPS-Argos Transmitters in Central Europe. Ornis Fenn. 2022, 99, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schally, G.T. Analysis of Observation and Hunting Bag Data of Eurasian Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola Linnaeus, 1758) in Hungary Between 2009–2018. Ph.D. Thesis, Szent István University, Gödöllő, Hungary, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schally, G.; Csányi, S. Eurasian Woodcock Monitoring in Hungary between 2009–2021. Rev. Agric. Rural Dev. 2022, 11, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.J. Birds and Habitat: Relationships in Changing Landscapes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-139-85130-5. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.; Shorten, M. Breeding of the Woodcock in Britain. Bird Study 1974, 21, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirons, G.J.M.; Johnson, D. Woodcock Foraging Behavior. Biol. Conserv. 1987, 42, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand, Y.; Gossmann, F.; Bastat, C.; Guénézan, M. Monitoring of the Wintering and Breeding Woodcock Populations in France. Rev. Catalana D’ornitologia 2008, 24, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Scolopax rusticola: BirdLife International: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2025: E.T22693052A155471018. 2016. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/en (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Eaton, M.; Aebischer, N.; Brown, A.; Hearn, R.; Lock, L.; Musgrove, A.; Noble, D.; Stroud, D.; Gregory, R. Birds of Conservation Concern 4: The Population Status of Birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man. Br. Birds 2015, 108, 708–746. [Google Scholar]

- Sládeček, M.; Pešková, L.; Chajma, P.; Brynychová, K.; Koloušková, K.; Trejbalová, K.; Kolešková, V.; Petrusová Vozabulová, E.; Šálek, M.E. Eurasian Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) in Intensively Managed Central European Forests Use Large Home Ranges with Diverse Habitats. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 550, 121489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, Å.; Green, M.; Paulson, G.; Smith, H.G.; Devictor, V. Rapid Changes in Bird Community Composition at Multiple Temporal and Spatial Scales in Response to Recent Climate Change. Ecography 2013, 36, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrand, Y.; Gossmann, F.; Bastat, C. Breeding Woodcock Scolopax rusticola Monitoring in France. Ornis Hung. 2003, 12, 293–296. [Google Scholar]

- Hirons, G. The Significance of Roding by Woodcock Scolopax Rusticola: An Alternative Explanation Based on Observations of Marked Birds. Ibis 1980, 122, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szemethy, L. Results Hungarian Woodcock Monitoring. Rev. Agric. Rural Dev. 2014, 3, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schally, G.; Bleier, N.; Szemethy, L. Monitoring the Migration of Eurasian Woodcock in Hungary. Hung. Agric. Res. 2012, 1, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schally, G.; Frank, K.; Heltai, B.; Fehér, P.; Farkas, Á.; Szemethy, L.; Stéger, V. High Genetic Diversity and Weak Population Structuring in the Eurasian Woodcock in Hungary during Spring. Ornis Fenn. 2018, 95, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuti, M.; Rodrigues, T.M.; Bongi, P.; Murphy, K.J.; Pennacchini, P.; Mazzarone, V.; Sargentini, C. Monitoring Eurasian Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) with Pointing Dogs in Italy to Inform Evidence-Based Management of a Migratory Game Species. Diversity 2023, 15, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, S.R. Integrated Population Monitoring of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland. Ibis 1990, 132, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoccoz, N.G.; Nichols, J.D.; Boulinier, T. Monitoring of Biological Diversity in Space and Time. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schally, G. Assessment of the Breeding and Wintering Sites of Eurasian Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) Occurring in Hungary Based on Ringing Recovery Data. Ornis Hung. 2019, 27, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.