Drivers of Variation in Avian Community Composition Across a Tropical Island Montane Elevational Gradient

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Mist Net Sampling and Data Management

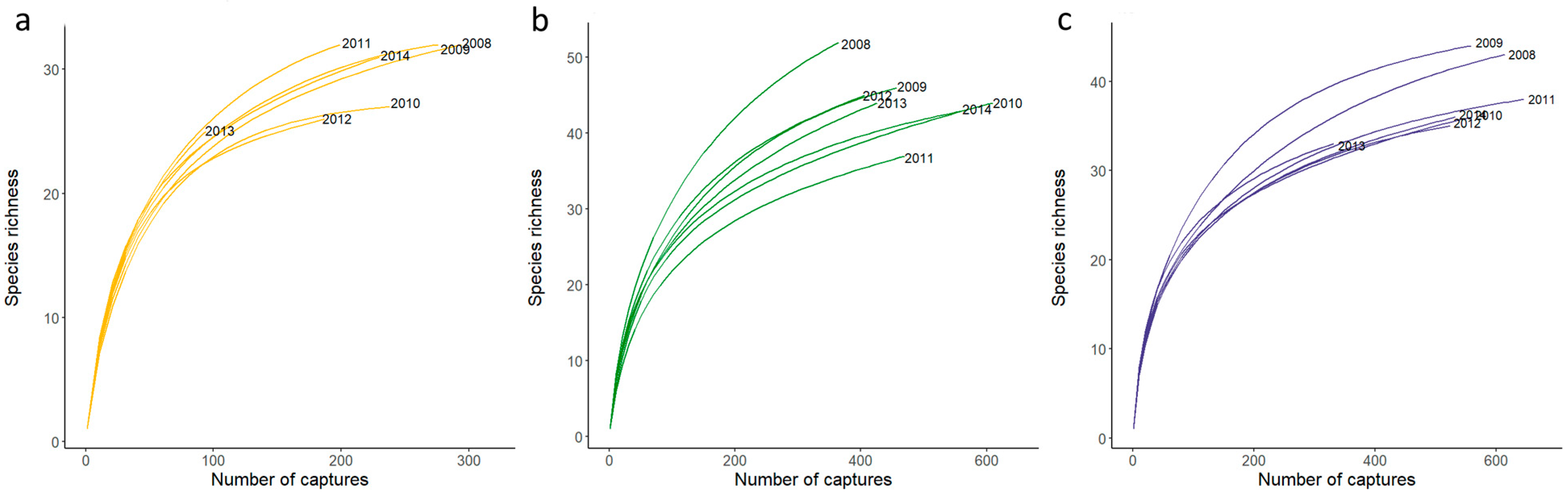

2.3. Statistical Analyses—Alpha Diversity Measures

2.4. Beta (β) Diversity and Nestedness

2.5. Bird Community Dissimilarity

3. Results

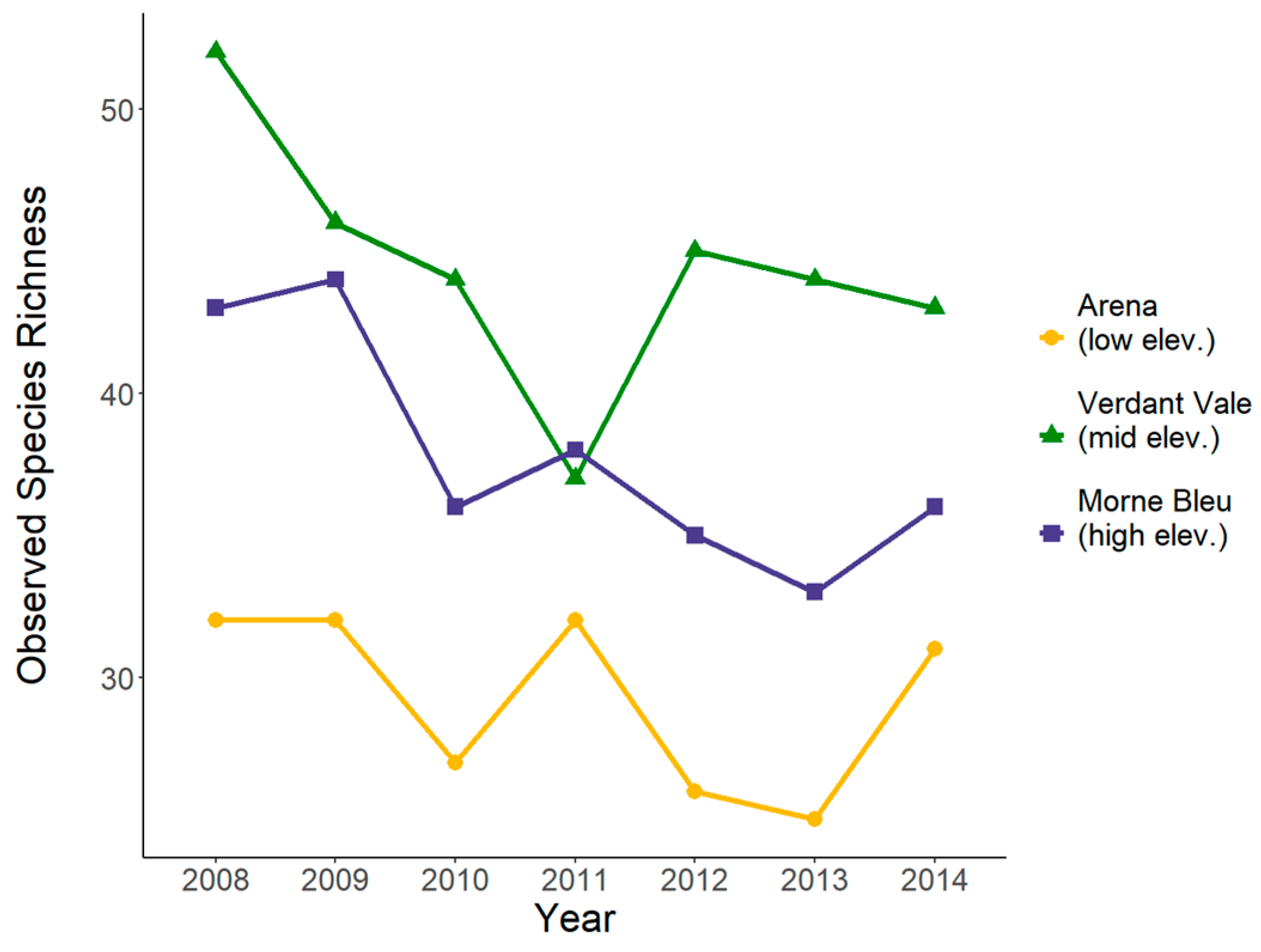

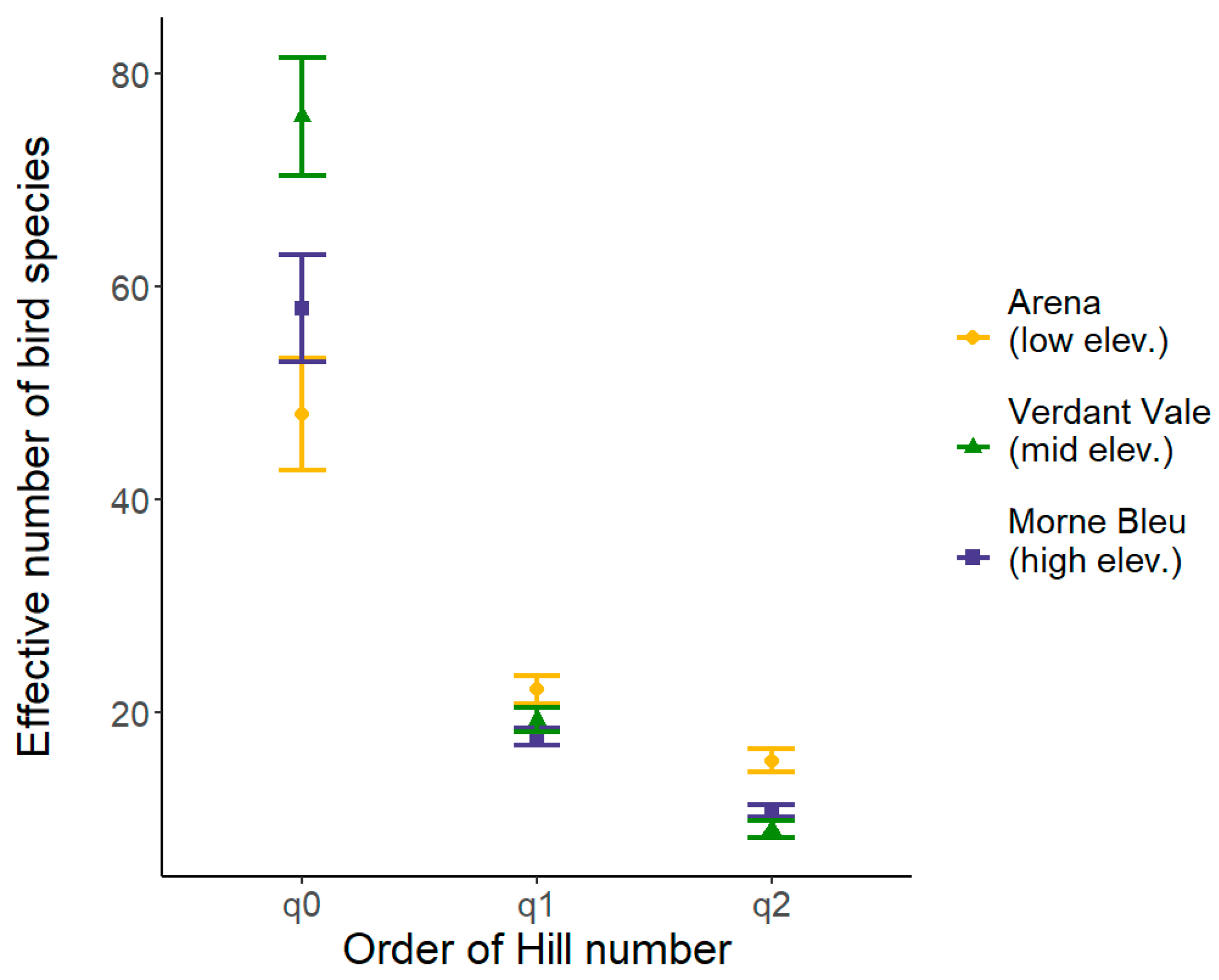

3.1. Measures of Bird Alpha Diversity Across Sites and Years

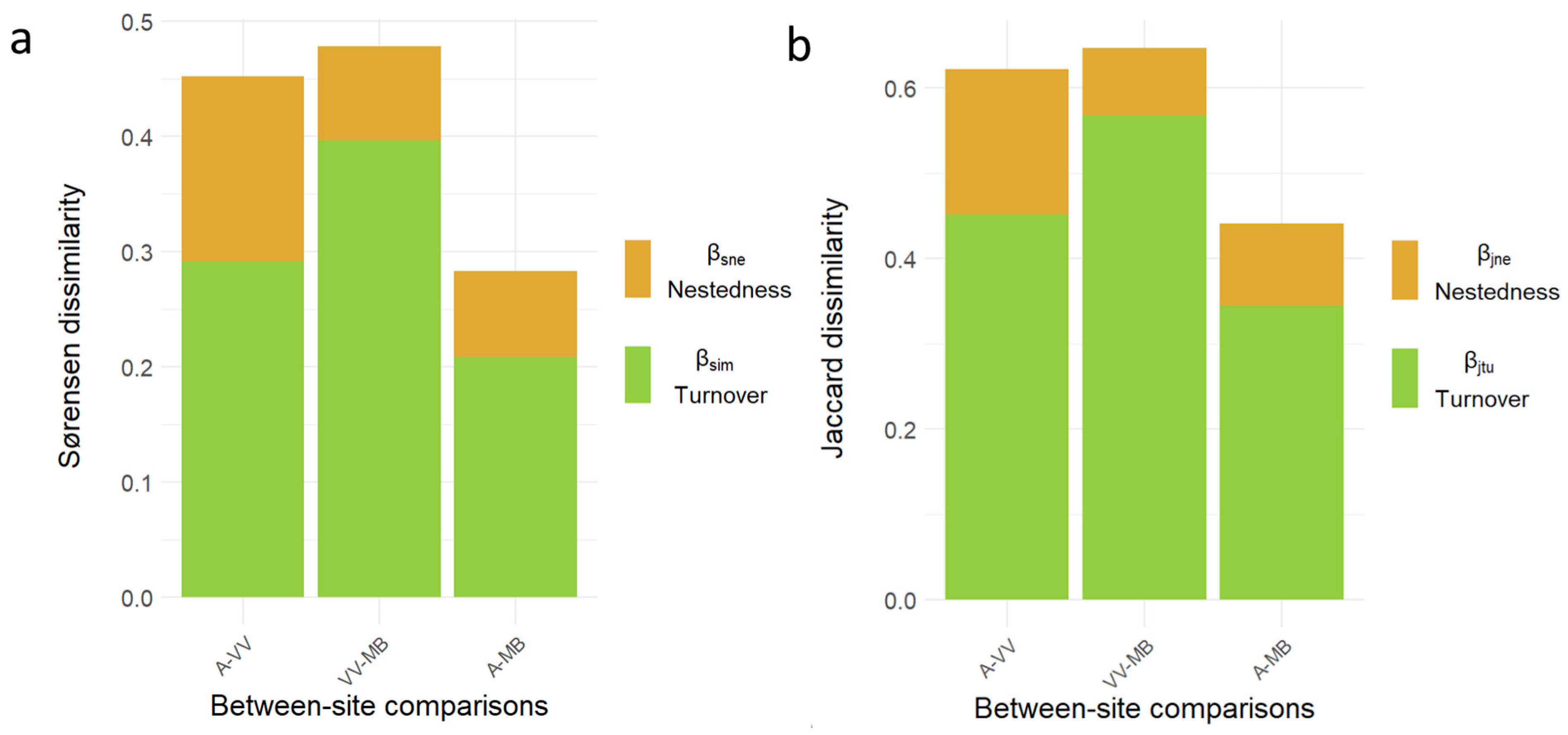

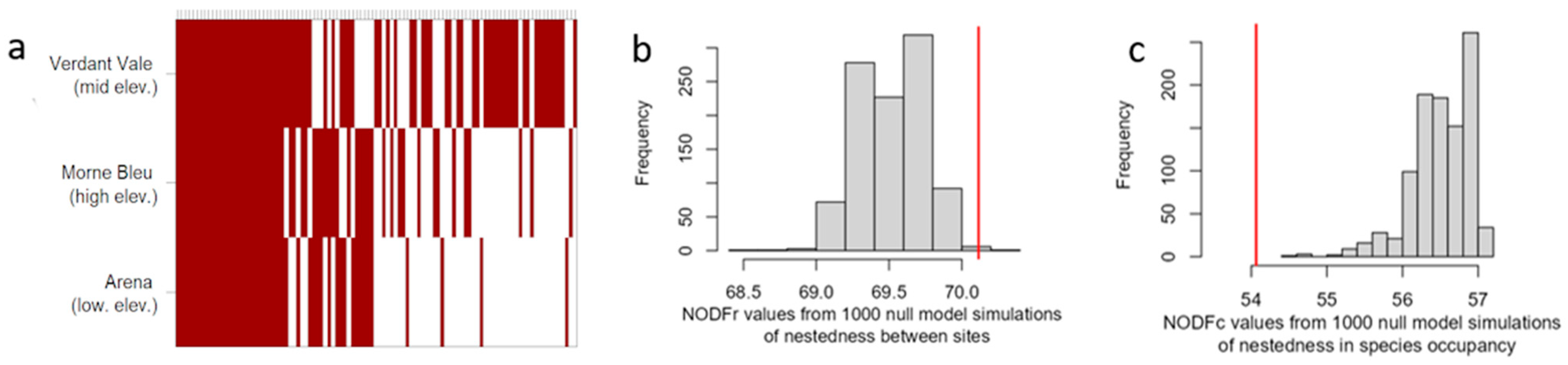

3.2. Beta Diversity and Nestedness Between Elevations

3.3. β-Diversity and Nestedness Between Successive Years

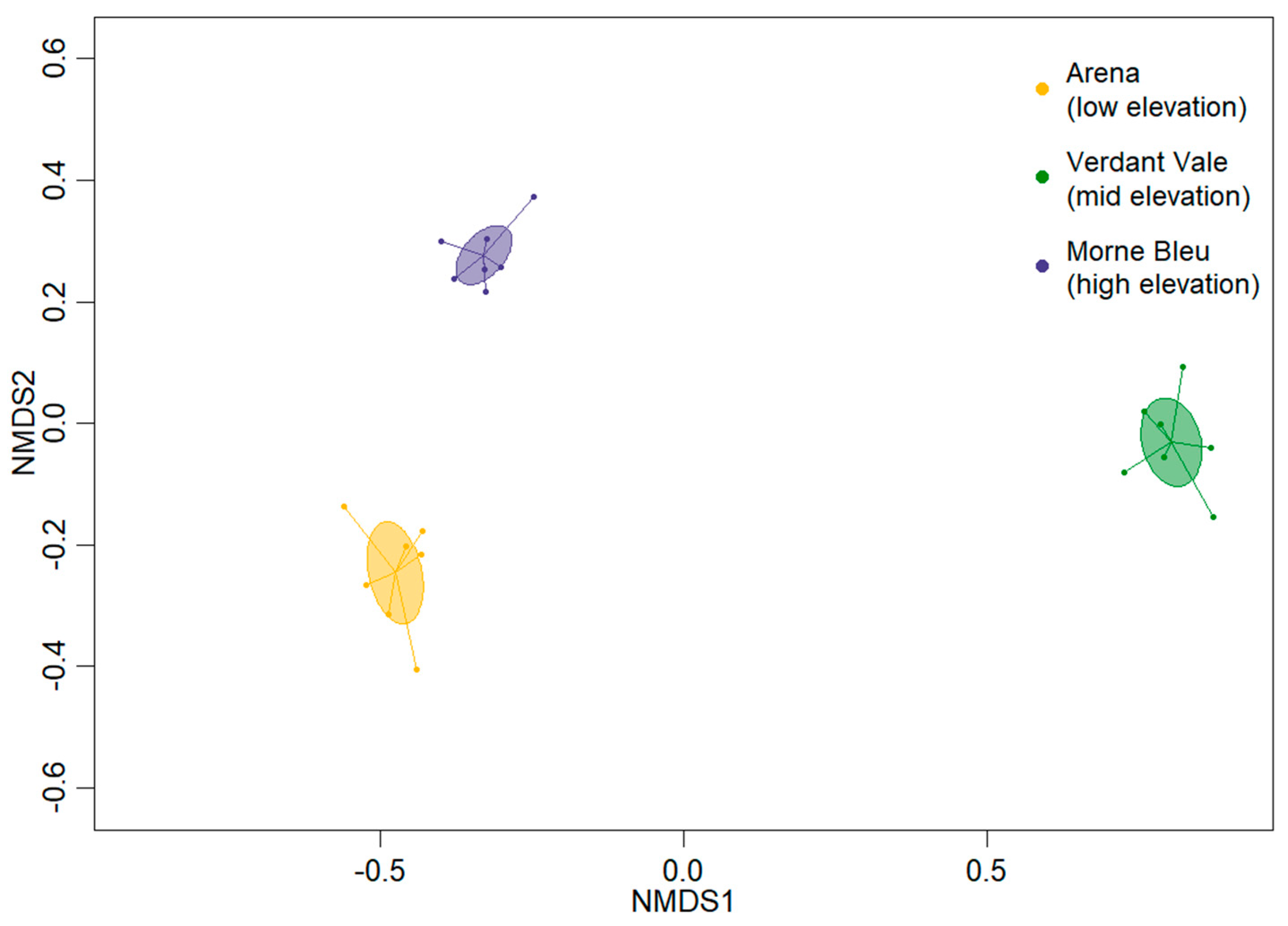

3.4. Bird Community Dissimilarity

4. Discussion

4.1. Elevational Variation in Alpha and Beta Diversity

4.2. Species Turnover Between Sites and Elevation

4.3. Nestedness in Species Composition Between Sites

4.4. Dissimilarities in Bird Communities

4.5. Temporal Changes in Avian Community Composition

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Metric | Notation | Description a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hill Number | qD | [43] | |

| Sørensen dissimilarity index | βsor | [20,37] | |

| Simpson dissimilarity index (turnover fraction of Sørensen dissimilarity) | βsim | [20,37] | |

| Nestedness fraction of Sørensen dissimilarity | βsne | [20,37] | |

| Jaccard dissimilarity index | βjac | [21,37] | |

| Turnover fraction of Jaccard dissimilarity | βjtu | [21,37] | |

| Nestedness fraction of Jaccard dissimilarity | βjne | [21,37] |

| Arena (4 spp. Total) | Verdant Vale (35 spp. Total) | Morne Bleu (13 spp. Total) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dusky-Capped Flycatcher ■ Myiarchus tuberculifer Lesser Elaenia ● Elaenia chiriquensis Red-Crowned Ant Tanager ■ Habia rubica Yellow-Breasted Flycatcher ■ Tolmomyias flaviventris | Amazonian White-Tailed (Green-backed) Trogon ▲ Trogon viridis Barred Antshrike ■ Thamnophilus doliatus Blue Dacnis ● Dacnis cayana Chestnut-Bellied Seed Finch ♦ Sporophila angolensis Ferruginous Pygmy Owl ■ Glaucidium brasilianum Fuscous Flycatcher Cnemotriccus fuscatus ■ Great Kiskadee ● Pitangus sulphuratus Grey-Breasted Martin ■ Progne chalybea Greyish Saltator ■ Saltator coerulescens Lesson’s Seedeater ♦ Sporophila bouvronides Lineated Woodpecker ■ Dryocopus lineatus Long-Billed Starthroat ▲ Heliomaster longirostris | Mouse-Coloured Tyrannulet ■ Phaeomyias murina Pale-Breasted Spinetail ■ Synallaxis albescens Piratic Flycatcher ▲ Legatus leucophaius Red-Eyed Vireo ■ Vireo olivaceus Ruby Topaz ▲ Chrysolampis mosquitus Ruddy Ground-Dove ♦ Columbina talpacoti Rufous-Shafted Woodstar ▲ Chaetocercus jourdanii Silver-Beaked Tanager ● Ramphocelus carbo Small-Billed Elaenia ■ Elaenia parvirostris Smooth-Billed Ani ● Crotophaga ani Southern House Wren ■ Troglodytes aedon Southern Rough-Winged Swallow ■ Stelgidopteryx ruficollis | Streaked Flycatcher ● Myiodynastes maculatus Streaked Xenops ■ Xenops rutilans Trinidad Euphonia ● Euphonia trinitatis Tropical Kingbird ■ Tyrannus melancholicus Tropical Mockingbird ■ Mimus gilvus Tufted Coquette ● Lophornis ornatus Turquoise Tanager ● Tangara mexicana Variegated Flycatcher ■ Empidomus varius White-Tipped Dove ♦ Leptotila verreauxi Yellow Bellied Elaenia ● Elaenia flavogaster Yellow Oriole ▲ Icterus nigrogularis | Black-Faced Antthrush ■ Formicarius analis Brown Violet-ear ▲ Colibri delphinae Chestnut Woodpecker ■ Celeus elegans Collared Trogon ■ Trogon collaris Great Antshrike ■ Taraba major Grey-Rumped Swift ■ Chaetura cinereiventris Hepatic Tanager ■ Piranga flava Lined Quail Dove ♦ Zentrygon linearis Olive-Striped Flycatcher ▲ Mionectes olivaceus Orange-Billed Nightingale Thrush ● Catharus aurantiirostris Speckled Tanager ▲ Tangara guttata Stripe-Breasted Spinetail ■ Synallaxis cinnamomea Yellow-Legged Thrush Turdus flavipes ▲ |

| Absent from Arena Only (7 spp.) | Absent from Verdant Vale Only (10 spp.) | Absent from Morne Bleu Only (6 spp.) |

|---|---|---|

| Spectacled Thrush ● Turdus nudigenis Black-Throated Mango ▲ Anthracothorax migricollis Blue-Grey Tanager ● Thraupis episcopus Copper-Rumped Hummingbird ▲ Amazilia tobaci Palm Tanager ▲ Thraupis palmarum Red-Legged Honeycreeper ▲ Cyanerpes cyaneus Southern Beardless Tyrannulet ■ Camptostoma obsoletum | Golden-Olive Woodpecker ■ Colaptes rubiginosus Grey-Fronted Dove ♦ Leptotila rufaxilla Grey-Throated Leaftosser ■ Sclerurus albigularis Plain Antvireo ■ Dysithamnus mentalis Red-Rumped Woodpecker ■ Veniliornis kirkii White-Bellied Antbird ■ Myrmeciza longipes White-Flanked Antwren ■ Myrmotherula axillaris White-Shouldered Tanager ■ Tachyphonus luctuosus White-Throated Spadebill ■ Platyrinchus mystaceus Yellow-Olive Flycatcher ■ Tolmomyias sulphurescens | American Pygmy Kingfisher ▌ Chloroceryle aenea Blue-Black Grassquit ● Volatinia jacarina Forest Elaenia ■ Myiopagis gaimardii Rufous-Browed Peppershrike ■ Cyclarhis gujanensis Shiny Cowbird ■ Molothrus bonariensis Tropical Parula ■ Parula pitiayumi |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βsim | βsne | βsor | βsim | βsne | βsor | βsim | βsne | βsor | βsim | βsne | βsor | βsim | βsne | βsor | βsim | βsne | βsor | βsim | βsne | βsor | |

| Arena—Verdant Vale | 0.406 | 0.141 | 0.548 | 0.500 | 0.090 | 0.590 | 0.333 | 0.160 | 0.493 | 0.563 | 0.032 | 0.594 | 0.462 | 0.144 | 0.606 | 0.360 | 0.176 | 0.536 | 0.500 | 0.073 | 0.573 |

| Verdant Vale—Morne Bleu | 0.419 | 0.055 | 0.474 | 0.568 | 0.010 | 0.578 | 0.389 | 0.061 | 0.450 | 0.486 | 0.007 | 0.493 | 0.486 | 0.064 | 0.550 | 0.485 | 0.074 | 0.558 | 0.444 | 0.049 | 0.494 |

| Arena—Morne Bleu | 0.250 | 0.110 | 0.360 | 0.156 | 0.133 | 0.133 | 0.148 | 0.122 | 0.270 | 0.344 | 0.056 | 0.400 | 0.231 | 0.113 | 0.344 | 0.160 | 0.116 | 0.276 | 0.375 | 0.036 | 0.412 |

| βSIM | βSNE | βSOR | βSIM | βSNE | βSOR | βSIM | βSNE | βSOR | βSIM | βSNE | βSOR | βSIM | βSNE | βSOR | βSIM | βSNE | βSOR | βSIM | βSNE | βSOR | |

| Overall beta diversity (multiple-site dissimilarity) | 0.433 | 0.103 | 0.536 | 0.495 | 0.066 | 0.561 | 0.370 | 0.119 | 0.489 | 0.522 | 0.030 | 0.552 | 0.473 | 0.108 | 0.581 | 0.420 | 0.125 | 0.545 | 0.506 | 0.055 | 0.561 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βjtu | βjne | βjac | βjtu | βjne | βjtu | βjne | βjac | βjtu | βjne | βjtu | βjne | βjac | βjtu | βjne | βjtu | βjtu | βjne | βjac | βjne | βjac | |

| Arena—Verdant Vale | 0.578 | 0.130 | 0.708 | 0.667 | 0.752 | 0.578 | 0.130 | 0.708 | 0.667 | 0.752 | 0.578 | 0.130 | 0.708 | 0.667 | 0.752 | 0.529 | 0.169 | 0.698 | 0.667 | 0.062 | 0.729 |

| Verdant Vale—Morne Bleu | 0.590 | 0.053 | 0.643 | 0.725 | 0.008 | 0.590 | 0.053 | 0.643 | 0.725 | 0.008 | 0.590 | 0.053 | 0.643 | 0.725 | 0.008 | 0.653 | 0.064 | 0.717 | 0.615 | 0.046 | 0.661 |

| Arena—Morne Bleu | 0.400 | 0.129 | 0.529 | 0.270 | 0.179 | 0.400 | 0.129 | 0.529 | 0.270 | 0.179 | 0.400 | 0.129 | 0.529 | 0.270 | 0.179 | 0.276 | 0.157 | 0.432 | 0.545 | 0.038 | 0.583 |

| βJTU | βJNE | βJAC | βJTU | βJNE | βJTU | βJNE | βJAC | βJTU | βJNE | βJTU | βJNE | βJAC | βJTU | βJNE | βJTU | βJNE | βJAC | βJTU | βJNE | βJAC | |

| Overall beta diversity (multiple-site dissimilarity) | 0.605 | 0.094 | 0.698 | 0.662 | 0.057 | 0.605 | 0.094 | 0.698 | 0.662 | 0.057 | 0.605 | 0.094 | 0.698 | 0.662 | 0.057 | 0.592 | 0.114 | 0.706 | 0.672 | 0.047 | 0.719 |

| βSOR | βJAC | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall beta diversity between sites | 0.487 | 0.655 |

| Range of beta diversity between sites, within each year | 0.489–0.581 | 0.657–0.735 |

| Overall beta diversity between years | 0.411 | 0.583 |

| Range of beta diversity between years, within each site | 0.085–0.364 | 0.156–0.538 |

| Sørensen Dissimilarity | Jaccard Dissimilarity | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover βsim | Nestedness βsne | Total Beta Diversity βsor | Turnover βjtu | Nestedness βjne | Total Beta Diversity βjac | |||||||

| Coeff. | p | Coeff. | p | Coeff. | p | Coeff. | p | Coeff. | p | Coeff. | p | |

| Arena | 0.014 | 0.285 | 0.008 | 0.439 | 0.022 | 0.0501 | 0.021 | 0.280 | 0.011 | 0.494 | 0.031 | 0.0501 |

| Verdant Vale | −0.004 | 0.747 | −0.006 | 0.466 | −0.010 | 0.416 | −0.005 | 0.765 | −0.009 | 0.469 | −0.014 | 0.389 |

| Morne Bleu | −0.006 | 0.667 | −0.001 | 0.874 | −0.007 | 0.476 | −0.008 | 0.706 | −0.002 | 0.858 | −0.010 | 0.489 |

| Sites combined | −0.003 | 0.689 | −0.001 | 0.897 | −0.005 | 0.145 | −0.005 | 0.725 | −0.002 | 0.889 | −0.007 | 0.147 |

References

- Gaston, K.J. Global Patterns in Biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.G.; Orme, C.D.L.; Storch, D.; Olson, V.A.; Thomas, G.H.; Ross, S.G.; Ding, T.-S.; Rasmussen, P.C.; Bennett, P.M.; Owens, I.P.F.; et al. Topography, Energy and the Global Distribution of Bird Species Richness. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbek, C.; Gotelli, N.J.; Colwell, R.K.; Entsminger, G.L.; Rangel, T.F.L.V.B.; Graves, G.R. Predicting Continental-Scale Patterns of Bird Species Richness with Spatially Explicit Models. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J.E.; Londoño, G.A.; Robinson, S.K.; Chappell, M.A. Exploring the Role of Physiology and Biotic Interactions in Determining Elevational Ranges of Tropical Animals. Ecography 2013, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetz, W.; Rahbek, C. Geometric Constraints Explain Much of the Species Richness Pattern in African Birds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 5661–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmar, A.; Currie, D.J. A Global Model of Island Biogeography. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2006, 15, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Núñez, C.; Martínez-Prentice, R.; García-Navas, V. Land-Use Diversity Predicts Regional Bird Taxonomic and Functional Richness Worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, C.M. Global Analysis of Bird Elevational Diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009, 18, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J.E.; Ciecka, A.L.; Meyer, N.Y.; Rabenold, K.N. Beta Diversity along Environmental Gradients: Implications of Habitat Specialization in Tropical Montane Landscapes. J. Anim. Ecol. 2009, 78, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.G.; Strimas-Mackey, M.; Miller, E.T. Interspecific Competition Limits Bird Species’ Ranges in Tropical Mountains. Science 2022, 377, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jetz, W.; Wilcove, D.S.; Dobson, A.P. Projected Impacts of Climate and Land-Use Change on the Global Diversity of Birds. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terborgh, J. Bird Species Diversity on an Andean Elevational Gradient. Ecology 1977, 58, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño-Centellas, F.A.; Loiselle, B.A.; Tingley, M.W. Ecological Drivers of Avian Community Assembly along a Tropical Elevation Gradient. Ecography 2021, 44, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.G.; Loiselle, B.A. Diversity of Birds along an Elevational Gradient in the Cordillera Central, Costa Rica. Auk 2000, 117, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.G.; Loiselle, B.A. Bird Assemblages in Second-Growth and Old-Growth Forests, Costa Rica: Perspectives from Mist Nets and Point Counts. Auk 2001, 118, 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.M.; Rasolonandrasana, B.P.N. Elevational Zonation of Birds, Insectivores, Rodents and Primates on the Slopes of the Andringitra Massif, Madagascar. J. Nat. Hist. 2001, 35, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehler, B. Ecological Structuring of Forest Bird Communities in New Guinea. In Biogeography and Ecology of New Guinea: Part One–Seven; Gressitt, J.L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 837–861. ISBN 978-94-009-8632-9. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-632-05633-0. [Google Scholar]

- Koleff, P.; Gaston, K.J.; Lennon, J.J. Measuring Beta Diversity for Presence–Absence Data. J. Anim. Ecol. 2003, 72, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the Turnover and Nestedness Components of Beta Diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. The Relationship between Species Replacement, Dissimilarity Derived from Nestedness, and Nestedness. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks-Leite, C.; Ewers, R.M.; Metzger, J.-P. Edge Effects as the Principal Cause of Area Effects on Birds in Fragmented Secondary Forest. Oikos 2010, 119, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Crist, T.O.; Chase, J.M.; Vellend, M.; Inouye, B.D.; Freestone, A.L.; Sanders, N.J.; Cornell, H.V.; Comita, L.S.; Davies, K.F.; et al. Navigating the Multiple Meanings of β Diversity: A Roadmap for the Practicing Ecologist. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwell, L.J.; Isaac, N.J.B.; Kunin, W.E. Measuring β-Diversity with Species Abundance Data. J. Anim. Ecol. 2015, 84, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podani, J.; Ricotta, C.; Schmera, D. A General Framework for Analyzing Beta Diversity, Nestedness and Related Community-Level Phenomena Based on Abundance Data. Ecol. Complex. 2013, 15, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkle, J.C.; Owen, L.A.; Weber, J.C. Trinidad and Tobago. In Landscapes and Landforms of the Lesser Antilles; Allen, C.D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 267–291. ISBN 978-3-319-55787-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, M.; Bhukal, R.; Deacon, A.; Farrell, A.; Kanhai, L.D.K.; Mohammed, R.; Murphy, J.C.; Parasram, S.; Rosant, L.V.; Sewlal, J.-A.; et al. Arima Valley Bioblitz 2013 Final Report; The University of the West Indies: Saint Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Agard, J.; Alkins-Koo, M.; Cropper, A.; Garcia, K.; Homer, F.; Maharaj, S. Report of an Assessment of the Northern Range, Trinidad and Tobago: People and the Northern Range; State of the Environment Report 2004; Environmental Management Authority of Trinidad and Tobago: Port of Spain, Trinidad, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Redfern, C.P.F.; Clark, J.A. Ringers’ Manual, 4th ed.; British Trust for Ornithology: Thetford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; The R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit Software; Posit Team: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Shan, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Yao, Y. Comparison of the Predictive Ability of Spectral Indices for Commonly Used Species Diversity Indices and Hill Numbers in Wetlands. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor-Fors, I.; Payton, M.E. Contrasting Diversity Values: Statistical Inferences Based on Overlapping Confidence Intervals. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Alvarez, E.A.; Almazán-Núñez, R.C.; Corcuera, P.; González-García, F.; Brito-Millán, M.; Alvarado-Castro, V.M. Land Use Cover Changes the Bird Distribution and Functional Groups at the Local and Landscape Level in a Mexican Shaded-Coffee Agroforestry System. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 330, 107882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.H.; Chao, A. iNEXT: An R Package for Rarefaction and Extrapolation of Species Diversity (Hill Numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D. Nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models, Version 3.1-168; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 1999.

- Baselga, A.; Orme, D.; Villeger, S.; De Bortoli, J.; Leprieur, F.; Logez, M.; Martinez-Santalla, S.; Martin-Devasa, R.; Gomez-Rodriguez, C.; Crujeiras, R.M. Betapart: Partitioning Beta Diversity into Turnover and Nestedness Components, R Package Version 1.6; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Hao, M.; Corral-Rivas, J.J.; González-Elizondo, M.S.; Ganeshaiah, K.N.; Nava-Miranda, M.G.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; von Gadow, K. Assessing Biological Dissimilarities between Five Forest Communities. For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Neto, M.; Guimarães, P.; Guimarães, P.R., Jr.; Loyola, R.D.; Ulrich, W. A Consistent Metric for Nestedness Analysis in Ecological Systems: Reconciling Concept and Measurement. Oikos 2008, 117, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklós, I.; Podani, J. Randomization of Presence–Absence Matrices: Comments and New Algorithms. Ecology 2004, 85, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Wilman, H.; Belmaker, J.; Simpson, J.; de la Rosa, C.; Rivadeneira, M.M.; Jetz, W. EltonTraits 1.0: Species-Level Foraging Attributes of the World’s Birds and Mammals. Ecology 2014, 95, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Gotelli, N.J.; Hsieh, T.C.; Sander, E.L.; Ma, K.H.; Colwell, R.K.; Ellison, A.M. Rarefaction and Extrapolation with Hill Numbers: A Framework for Sampling and Estimation in Species Diversity Studies. Ecol. Monogr. 2014, 84, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbek, C. The Relationship among Area, Elevation, and Regional Species Richness in Neotropical Birds. Am. Nat. 1997, 149, 875–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burivalova, Z.; Şekercioğlu, Ç.H.; Koh, L.P. Thresholds of Logging Intensity to Maintain Tropical Forest Biodiversity. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, E.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Vega-Rivera, J.H.; Schondube, J.E.; de Freitas, S.M.; Fahrig, L. Impact of Landscape Composition and Configuration on Forest Specialist and Generalist Bird Species in the Fragmented Lacandona Rainforest, Mexico. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 184, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, H.; Deacon, A.E.; Hulme, M.F.; Sansom, A.; Jaggernauth, D.; Magurran, A.E. Contrasting Trends in Biodiversity of Birds and Trees during Succession Following Cacao Agroforest Abandonment. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, C.A.; Bullock, J.M.; Martin, P.A. Dynamics of Avian Species and Functional Diversity in Secondary Tropical Forests. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 211, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, J.A.; Sheard, C.; Pigot, A.L.; Devenish, A.J.M.; Yang, J.; Sayol, F.; Neate-Clegg, M.H.C.; Alioravainen, N.; Weeks, T.L.; Barber, R.A.; et al. AVONET: Morphological, Ecological and Geographical Data for All Birds. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J.E.; Merkord, C.L.; Rios, W.F.; Cabrera, K.G.; Revilla, N.S.; Silman, M.R. The Relationship of Tropical Bird Communities to Tree Species Composition and Vegetation Structure along an Andean Elevational Gradient. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soininen, J.; Heino, J.; Wang, J. A Meta-Analysis of Nestedness and Turnover Components of Beta Diversity across Organisms and Ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Liang, J.; Yang, L.; Wei, C.; Hu, H.; Si, X. Deterministic Processes Drive Turnover-Dominated Beta Diversity of Breeding Birds along the Central Himalayan Elevation Gradient. Avian Res. 2024, 15, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, X.; Zhong, M.; Tang, K.; Du, Y.; Xu, H.; Yi, J.; Liu, W.; Hu, J. Elevational Patterns and Assembly Processes of Multifaceted Bird Diversity in a Subtropical Mountain System. J. Biogeogr. 2024, 51, 1276–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño-Centellas, F.; Loiselle, B.A.; McCain, C. Multiple Dimensions of Bird Beta Diversity Support That Mountains Are Higher in the Tropics. J. Biogeogr. 2021, 48, 2455–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillán, V.; Quitián, M.; Tinoco, B.A.; Zárate, E.; Schleuning, M.; Böhning-Gaese, K.; Neuschulz, E.L. Direct and Indirect Effects of Elevation, Climate and Vegetation Structure on Bird Communities on a Tropical Mountain. Acta Oecologica 2020, 102, 103500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, S.K.; Kessler, M.; Bach, K. The Elevational Gradient in Andean Bird Species Richness at the Local Scale: A Foothill Peak and a High-elevation Plateau. Ecography 2005, 28, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BirdLife International. The IUCN Red List. Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org/about-our-science/the-iucn-red-list (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Thiollay, J.-M. Disturbance, Selective Logging and Bird Diversity: A Neotropical Forest Study. Biodivers. Conserv. 1997, 6, 1155–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.A.; Baldauf, S.L.; Mayhew, P.J.; Hill, J.K. The Response of Avian Feeding Guilds to Tropical Forest Disturbance. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregman, T.P.; Sekercioglu, C.H.; Tobias, J.A. Global Patterns and Predictors of Bird Species Responses to Forest Fragmentation: Implications for Ecosystem Function and Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 169, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.L.; Cordeiro, N.J.; Stratford, J.A. Ecology and Conservation of Avian Insectivores of the Rainforest Understory: A Pantropical Perspective. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 188, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ffrench, R. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad and Tobago; Helm Field Guides; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7136-6759-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ausprey, I.J.; Newell, F.L.; Robinson, S.K. Sensitivity of Tropical Montane Birds to Anthropogenic Disturbance and Management Strategies for Their Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, A.S.; Frey, S.J.K.; Robinson, W.D.; Betts, M.G. Forest Fragmentation and Loss Reduce Richness, Availability, and Specialization in Tropical Hummingbird Communities. Biotropica 2018, 50, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.H.; Barreto, E.; Murillo, O.; Robinson, S.K. Turnover-Driven Loss of Forest-Dependent Species Changes Avian Species Richness, Functional Diversity, and Community Composition in Andean Forest Fragments. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 32, e01922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiselle, B.A.; Blake, J.G. Temporal Variation in Birds and Fruits along an Elevational Gradient in Costa Rica. Ecology 1991, 72, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barçante, L.; Vale, M.M.; Alves, M.A.S. Altitudinal Migration by Birds: A Review of the Literature and a Comprehensive List of Species. J. Field Ornithol. 2017, 88, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingley, M.W.; Beissinger, S.R. Cryptic Loss of Montane Avian Richness and High Community Turnover over 100 Years. Ecology 2013, 94, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmel, K.; Riegert, J.; Paul, L.; Novotný, V. Vertical Stratification of an Avian Community in New Guinean Tropical Rainforest. Popul. Ecol. 2016, 58, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martensen, A.C.; Ribeiro, M.C.; Banks-Leite, C.; Prado, P.I.; Metzger, J.P. Associations of Forest Cover, Fragment Area, and Connectivity with Neotropical Understory Bird Species Richness and Abundance. Conserv. Biol. 2012, 26, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.D.; Brawn, J.D.; Robinson, S.K. Forest Bird Community Structure in Central Panama: Influence of Spatial Scale and Biogeography. Ecol. Monogr. 2000, 70, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, S.C.; Waltert, M.; Mühlenberg, M. Comparison of Bird Communities in Primary vs. Young Secondary Tropical Montane Cloud Forest in Guatemala. In Forest Diversity and Management; Hawksworth, D.L., Bull, A.T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 485–515. ISBN 978-1-4020-5208-8. [Google Scholar]

- Si, X.; Cadotte, M.W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, D.; Li, J.; Jin, T.; Ren, P.; Wang, Y.; Ding, P.; et al. The Importance of Accounting for Imperfect Detection When Estimating Functional and Phylogenetic Community Structure. Ecology 2018, 99, 2103–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C.H.; Fine, P.V.A. Phylogenetic Beta Diversity: Linking Ecological and Evolutionary Processes across Space in Time. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petchey, O.L.; Gaston, K.J. Functional Diversity (FD), Species Richness and Community Composition. Ecol. Lett. 2002, 5, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanz, D.M.; Böhning-Gaese, K.; Ferger, S.W.; Fritz, S.A.; Neuschulz, E.L.; Quitián, M.; Santillán, V.; Töpfer, T.; Schleuning, M. Functional and Phylogenetic Diversity of Bird Assemblages Are Filtered by Different Biotic Factors on Tropical Mountains. J. Biogeogr. 2019, 46, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregman, T.P.; Lees, A.C.; MacGregor, H.E.A.; Darski, B.; de Moura, N.G.; Aleixo, A.; Barlow, J.; Tobias, J.A. Using Avian Functional Traits to Assess the Impact of Land-Cover Change on Ecosystem Processes Linked to Resilience in Tropical Forests. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20161289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigo, F.; Paniccia, C.; Anderle, M.; Chianucci, F.; Obojes, N.; Tappeiner, U.; Hilpold, A.; Mina, M. Relating Forest Structural Characteristics to Bat and Bird Diversity in the Italian Alps. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 554, 121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Site | Number of Captures | Number of Individuals | Number of Species | |||

| By Site | Yearly Total | By Site | Yearly Total | By Site | Yearly Total | ||

| 2008 | Arena | 294 | 1273 | 263 | 1157 | 32 | 76 |

| Verdant Vale | 365 | 324 | 52 | ||||

| Morne Bleu | 614 | 570 | 43 | ||||

| 2009 | Arena | 276 | 1292 | 245 | 1180 | 32 | 75 |

| Verdant Vale | 457 | 407 | 46 | ||||

| Morne Bleu | 559 | 528 | 44 | ||||

| 2010 | Arena | 238 | 1407 | 202 | 1249 | 27 | 61 |

| Verdant Vale | 610 | 535 | 44 | ||||

| Morne Bleu | 559 | 512 | 36 | ||||

| 2011 | Arena | 199 | 1315 | 188 | 1221 | 32 | 64 |

| Verdant Vale | 470 | 433 | 37 | ||||

| Morne Bleu | 646 | 600 | 38 | ||||

| 2012 | Arena | 187 | 1117 | 165 | 1006 | 26 | 67 |

| Verdant Vale | 406 | 369 | 45 | ||||

| Morne Bleu | 524 | 472 | 35 | ||||

| 2013 | Arena * | 94 | 852 | 89 | 783 | 25 | 62 |

| Verdant Vale | 426 | 384 | 44 | ||||

| Morne Bleu * | 332 | 310 | 33 | ||||

| 2014 | Arena | 230 | 1328 | 197 | 1186 | 32 | 68 |

| Verdant Vale | 565 | 493 | 43 | ||||

| Morne Bleu | 533 | 496 | 36 | ||||

| Number of captures | Number of individuals | Number of species | |||||

| All Years combined | Arena | 1518 | 1126 | 48 | |||

| Verdant Vale | 3299 | 2709 | 76 | ||||

| Morne Bleu | 3767 | 3219 | 58 | ||||

| Site | NODF Index | Nobs | Nexp (SD) | Z-Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arena | NODF | 69.56 | 69.74 (0.433) | −0.433 | 0.566 |

| NODFr | 71.35 | 71.30 (0.508) | 0.108 | 0.916 | |

| NODFc | 69.52 | 69.71 (0.437) | −0.439 | 0.566 | |

| Verdant Vale | NODF | 66.84 | 66.51 (0.268) | 1.248 | 0.105 |

| NODFr | 77.48 | 77.42 (0.214) | 0.286 | 0.734 | |

| NODFc | 66.76 | 66.43 (0.269) | 1.247 | 0.105 | |

| Morne Bleu | NODF | 68.50 | 68.47 (0.299) | 0.081 | 0.932 |

| NODFr | 82.66 | 82.70 (0.190) | −0.205 | 0.848 | |

| NODFc | 68.32 | 68.30 (0.296) | 0.083 | 0.924 |

| Arena-Verdant Vale | Arena—Morne Bleu | Verdant Vale—Morne Bleu | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Cumulative Contribution | Species | Cumulative Contribution | Species | Cumulative Contribution |

| Bananaquit (VV) Coereba flaveola | 0.215 | Bananaquit (MB) Coereba flaveola | 0.210 | Golden-headed manakin (MB) Pipra erythrocephala | 0.126 |

| Palm tanager (VV) Thraupis palmarum | 0.287 | Golden-headed manakin (MB) Pipra erythrocephala | 0.341 | Bananaquit (VV) Coereba flaveola | 0.219 |

| Plain brown woodcreeper (A) Dendrocincla fuliginosa | 0.348 | Rufous-breasted hermit (MB) Glaucis hirsutus | 0.409 | Palm tanager (VV) Thraupis palmarum | 0.281 |

| Blue-black Grassquit (VV) Volatinia jacarina | 0.400 | Purple honeycreeper (MB) Cyanerpes caeruleus | 0.473 | Green hermit (MB) Phaethornis guy | 0.342 |

| Violaceous euphonia (VV) Euphonia violacea | 0.447 | Green hermit (MB) Phaethornis guy | 0.536 | Purple honeycreeper (MB) Cyanerpes caeruleus | 0.390 |

| Rufous-breasted hermit (VV) Glaucis hirsutus | 0.489 | White-chested emerald (MB) Amazilia brevirostris | 0.585 | Blue-black Grassquit (VV) Volatinia jacarina | 0.437 |

| Spectacled thrush (VV) Turdus nudigenis | 0.531 | Blue-chinned sapphire (MB) Chlorestes notata | 0.628 | White-necked thrush (MB) Turdus albicollis | 0.481 |

| White-bearded manakin (A) Manacus manacus | 0.566 | Plain brown woodcreeper (A) Dendrocincla fuliginosa | 0.671 | Spectacled thrush (VV) Turdus nudigenis | 0.518 |

| Ruddy ground dove (VV) Columbina talpacoti | 0.600 | Bay-headed tanager (MB) Tangara gyrola | 0.704 | Plain brown woodcreeper (MB) Dendrocincla fuliginosa | 0.552 |

| Golden-headed manakin (A) Pipra erythrocephala | 0.631 | Ruddy ground dove (VV) Columbina talpacoti | 0.583 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Woods, H.; Barclay, A.; Lloyd, H. Drivers of Variation in Avian Community Composition Across a Tropical Island Montane Elevational Gradient. Diversity 2026, 18, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010013

Woods H, Barclay A, Lloyd H. Drivers of Variation in Avian Community Composition Across a Tropical Island Montane Elevational Gradient. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoods, Hannah, Alan Barclay, and Huw Lloyd. 2026. "Drivers of Variation in Avian Community Composition Across a Tropical Island Montane Elevational Gradient" Diversity 18, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010013

APA StyleWoods, H., Barclay, A., & Lloyd, H. (2026). Drivers of Variation in Avian Community Composition Across a Tropical Island Montane Elevational Gradient. Diversity, 18(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010013