Abstract

The introduction of non-native fish species into southern China has been widespread, with tilapia being a major contributor. Commonly known as tilapia, Coptodon zillii, Oreochromis niloticus, and Sarotherodon galilaeus, have become the most common non-native fish in southern Chinese waters, even becoming the dominant species in some waters. In order to elucidate the seasonal and spatial distributions and environmental drivers of three tilapia species in the inland waters of Guangxi, systematic sampling was performed at 34 sampling sites in the major water systems through the four seasons in 2023. A total of 6093 specimens were collected, of which C. zillii dominated the catch (59.74%). In addition, the occurrence frequency of C. zillii was 92.65%, O. niloticus was 80.88%, and S. galilaeus was 45.59%. Seasonally, all species exhibited pronounced seasonality, peaking in summer and declining to winter minima. Similarly, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) indicated summer dispersion to a greater extent, while winter dispersion was the least of the four seasons. Spatially, C. zillii dominated the northern study area, and there was no distribution of S. galilaeus, while the proportion of S. galilaeus and O. niloticus increased as latitude moved south. The Mantel test showed three tilapia species correlated with latitude, temperature seasonality, and the min temperature of the coldest month. In addition, the results of the Generalized Additive Model (GAM) showed that the number of three tilapia species was also affected by water environmental factors: S. galilaeus was affected by turbidity, O. niloticus was affected by pH and CODMN, and C. zillii was affected by TN and water temperature. These findings highlight the synergistic effects of environmental gradients and spatial factors in shaping tilapia distribution, providing critical insights for freshwater ecosystem management under climate change.

1. Introduction

Biological invasions have become a major component of global change and a threat to species, with devastating ecological and economic impacts worldwide [1,2]. The IUCN list of “100 of the world’s worst invasive species”, which includes 25 aquatic organisms, includes eight fish, six of which are freshwater fish [3,4]. However, we are now living through “The freshwater biodiversity crisis” [5,6], and the invasion of no-native species is one of the major threatening factors [7,8]. As the most common and important introduced group in freshwater ecosystems, aquaculture has played a key role in the rapid expansion of fish [9,10]. More than 110 non-native fish species are used in aquaculture, accounting for more than 25% of the total aquaculture production in China [11,12]. In addition, tilapia is one of the most important species for freshwater aquaculture [13].

Tilapia is the common name for about 70 fish species of the family Cichlidae, which are native to the freshwaters of tropical Africa [14]. This family includes the mouthbrooding genera Oreochromis Günther, 1889 and Sarotherodon Rüppell, 1852, and the substrate-spawning tilapia [15]. Tilapias are promoted as the most important species in global aquaculture due to their disease resistance, rapid growth, reproductive ability, and high environmental tolerance, and have been introduced into at least 100 countries [16,17,18]. Since the first tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852), was introduced into China in 1957, more than seven tilapia species have been introduced into China [19,20]. According to the 2023 Fishery Statistical Yearbook, tilapia aquaculture production in 2022 exceeded 1700,000 t, an increase of 4.59% compared to 2021 [21].

Although tilapia is farmed in many parts of China, it was heavily concentrated in southern China, which accounted for about 81% of total tilapia production in 2013 [22]. Southern China has a warm and rainy climate, with an average annual precipitation of 1800 mm and an average annual temperature of 23 °C [23]. The warm climate and abundant rainfall have created the conditions for aquaculture, but have also contributed to the highest frequency of non-native fish species in the world [24]. However, the studies in the rivers of southern China have shown that the establishment of non-native species has been promoted by open-water aquaculture [25]. There is increasing evidence that tilapia have escaped from aquaculture facilities and established wild populations in most subtropical and tropical waters [26,27]. Tilapia are becoming one of the most widespread invasive fish species in China, particularly in the Pearl River Basin in southern China [28,29]. O. niloticus have led to the destruction of the trophic structure of fish communities in the rivers of Southern China [23]. Five tilapia species, including Coptodon zillii (Gervais, 1848), Oreochromis aureus (Steindachner, 1864), Sarotherodon galilaeus (Linnaeus, 1758), Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758), and a hybrid of O. mossambicus × O. niloticus, have been identified in the rivers of southern China [30]. Gu et al. [31] found that the distribution patterns of C. zillii and O. niloticus were related to temperature in southern China, but Guangxi Province is part of southern China, and only one sampling site was set in Guangxi, while most sampling points were set in Guangdong and Hainan provinces. However, the distribution of tilapia in the inland waters of Guangxi has not been extensively studied, and the driving environmental factors are unclear.

Therefore, this study elucidates the seasonal and spatial distributions and environmental drivers of three tilapia species (C. zillii, O. niloticus, and S. galilaeus) in the inland waters of Guangxi. The abundance of the three tilapia species was surveyed in the inland waters of Guangxi at 34 sites along the major water systems of the Guangxi inland river through the four seasons in 2023. The purposes of this study were (1) to understand the seasonal and spatial distribution of three tilapia species, (2) to determine which environmental variable is driving the distribution of three tilapia species, and (3) to study the responses of the three tilapia species’ numbers to water environmental factors. We expected a better understanding of tilapia species distribution studies and new information for non-native fish studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Field Sampling

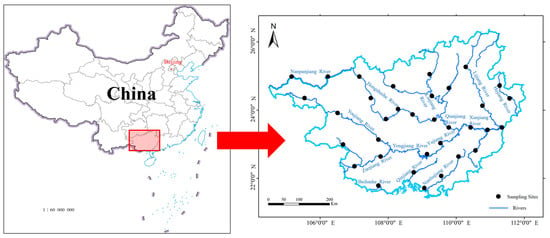

Guangxi is located in southeastern China, ranging from 104°26′ E to 112°04′ E and 20°54′ N to 26°24′ N, with a total surface area of 236,700 km2 [32]. The region has a unique karst landscape, and stone desertification areas are widely distributed, accounting for about 37.8% of the total surface area of Guangxi [33]. The average annual precipitation is above 1100 mm, and the average annual temperature is above 16 °C [34]. Although annual precipitation is abundant, its spatial and temporal distribution is uneven [35,36]. The region, an important part of the Pearl River system, has many rivers and abundant hydraulic resources. At the same time, it also covers part of the Red River system and the Yangtze River system. Surveys were carried out at 34 sites located along the main streams of major river systems in the inland waters of Guangxi: Nanpanjiang River, Hongshuihe River, Qianjiang River, Xunjiang River, Youjiang River, Zuojiang River, Yongjiang River and Yujiang River, Hejiang River, Guijiang River, Liujiang River, Nanliujiang River, and other southern rivers flowing to the sea (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographical location and sampling sites in the inland waters of Guangxi.

Field sampling was conducted in the four seasons in 2023: winter (February), spring (May and June), summer (August and September), and autumn (November and December). Based on the historical sampling situation of our laboratory and in accordance with the ‘Technical Specifications for the Investigation and Assessment of Inland Water Biodiversity’ (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China), samples were collected according to the different habitat characteristics of the river, and different fishing methods were used. So, two nets, single-layer gillnets (20–50 m × 1–2 m, mesh size 1–6 cm), and a bottom cage (0.3 m × 0.25 m, total length 8 m, mesh size 4 mm) were used flexibly according to the characteristics of the different river habitats. Single-layer gillnets were used in shallow and fast-flowing river sections. In the slow-flowing river section, a bottom cage was used as the main method, with single-layer gillnets as an auxiliary method. Single-layer gillnets and bottom cages were placed from 18:00 to 6:00 the next day. To increase the comparability of the data, the same mesh size and fishing time were used for each sampling. Following sample collection, immediate on-site identification of species was based on Exotic Aquatic Plants and Animals in China [37] and The Manual for Identifying Common Exotic Aquatic Organisms in China [38]. At the same time, the number of the three tilapia species was also counted.

2.2. Environmental Variable

We first collected 23 environmental variables, covering geographic variables (longitude, latitude, elevation, and slope) and climatic variables (19 bioclimatic variables). Longitude and latitude were recorded at the time of field sampling. Elevation and slope were extracted from EarthEnv at a 30 arc-second resolution (https://www.earthenv.org, accessed on 8 December 2024) [39]. Climatic variables include 19 bioclimatic variables for WorldClim version 2 at a 30 arc-second resolution that were extracted from WorldClim (https://www.worldclim.org, accessed on 1 December 2024). The 19 climatic variables cover both temperature (℃) and precipitation (mm), including annual mean temperature, mean diurnal range, isothermality, temperature seasonality, max temperature of warmest month, min temperature of coldest month, temperature annual range, mean temperature of wettest quarter, mean temperature of driest quarter, mean temperature of warmest quarter, mean temperature of coldest quarter, annual precipitation, precipitation of wettest month, precipitation of driest month, precipitation seasonality, precipitation of wettest quarter, precipitation of driest quarter, precipitation of warmest quarter, and precipitation of coldest quarter [40]. During sampling, nine water quality indicators were recorded daily on the website of Guangxi Ecological Environment Data Center and the real-time data publishing system of National Automatic Monitoring of Surface Water Quality (https://szzdjc.cnemc.cn:8070/GJZ/Business/Publish/Main.html, last accessed on 28 October 2025). The nine water quality indicators are as follows: water temperature (℃), pH, DO (mg/L), EC (μS/cm), turbidity (NTU), CODMN (mg/L), NH4 (mg/L), TP (mg/L), and TN (mg/L).

2.3. Data Analyses

In order to analyze the occurrence frequency, we calculated the occurrence frequency indicators: the proportion of the species occurrence with the total sampling sites/seasons. To study the variation in distribution along the four seasons, the number data of the three tilapia species were analyzed by PCoA after Gower’s distance transformation using the R package “vegan” [41,42] in R version 4.3.0. The Mantel test was used to analyze the relevance between three tilapia species and the environmental variables. Before conducting the Mantel test, we first tested the variance inflation factor (VIF) of the environmental variables using the R package “car” [43]. Environmental variables with VIF greater than 10 were removed, and those retained were subjected to Mantel test using the R package “ggcor” [44]. Generalized Additive Model (GAM) was used to study the responses of three tilapia species’ numbers to water environmental factors in the inland waters of Guangxi by R package “mgcv”. Water environmental factors with VIF greater than 3 were removed before the model was run. And the water environmental factors were screened by the stepwise method, and the optimal GAM model was selected according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), considering whether the p-value of the variable was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Species Composition

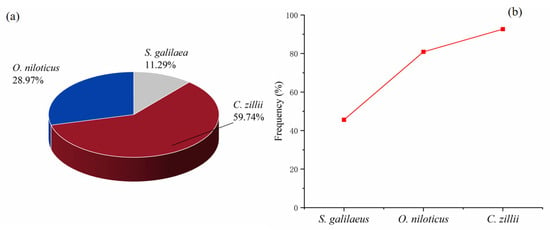

A total of 6093 specimens were collected from 34 sampling sites during all four seasons, with C. zillii dominating the catch (59.74%) (Figure 2a). In addition, the occurrence frequency of C. zillii was 92.65%, O. niloticus was 80.88%, and S. galilaeus was 45.59% (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Numerical ratios of three tilapia species (a) and occurrence frequency of three tilapia species (b).

3.2. Seasonal and Spatial Distribution of Three Tilapia Species

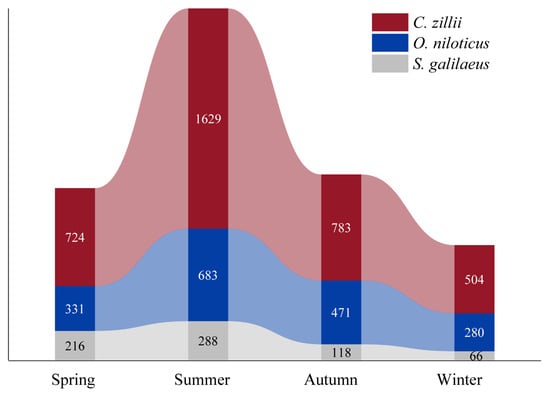

The results of the seasonal distribution show that the total number of the three tilapia species was highest in summer and lowest in winter, and the respective numbers of the three tilapia species were also highest in summer. In addition, spring and autumn remain similar between summer and winter (Figure 3). In addition, the distribution of the three tilapia species in each season showed that C. zillii has the highest abundance (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Seasonal distribution of the numbers collected for three tilapia species.

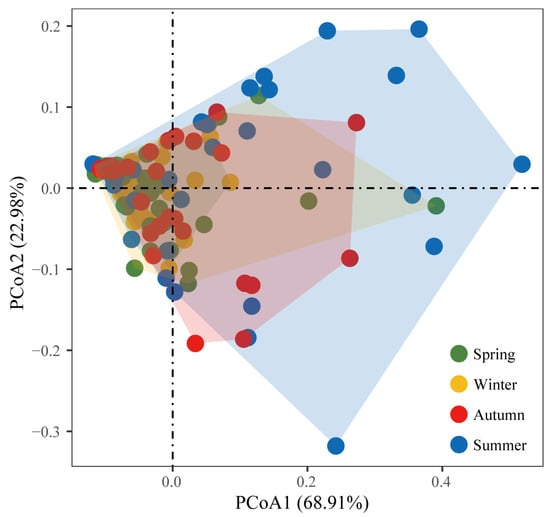

The PCoA result of the composition of the three tilapia species in the four seasons showed that PCo1 and PCo2 accounted for 68.91% and 22.98% of the overall variability, respectively (Figure 4). The composition of the three tilapia species did not show obvious separation in each season. In the PCoA results, the dispersion degree of the summer fish combinations was the greatest extent, autumn has a similar dispersion to spring, while winter dispersion is the least of the four seasons.

Figure 4.

The PCoA result of three tilapia species in the four seasons in the inland waters of Guangxi.

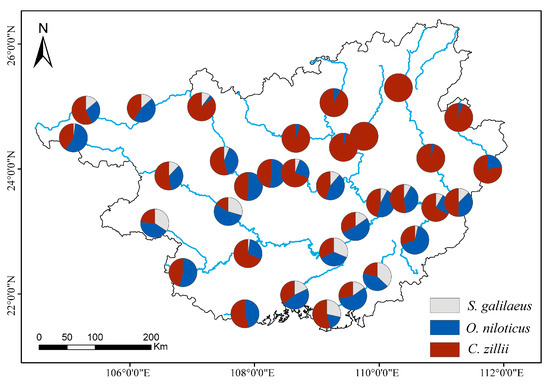

The numerical ratios of the three tilapia species are shown in Figure 5, showing distinct distribution characteristics in spatial distribution: C. zillii was dominant in the northern study area, and there was no distribution of S. galilaeus, and the proportion of O. niloticus was extremely low. S. galilaeus started to appear in the central region, and the percentage of O. niloticus also increased. The proportion of S. galilaeus and O. niloticus increased as latitude moved south.

Figure 5.

Numerical ratios of the three tilapia species at 34 sites from 4 seasons in the inland waters of Guangxi.

3.3. Drivers of Distribution of Three Tilapia Species

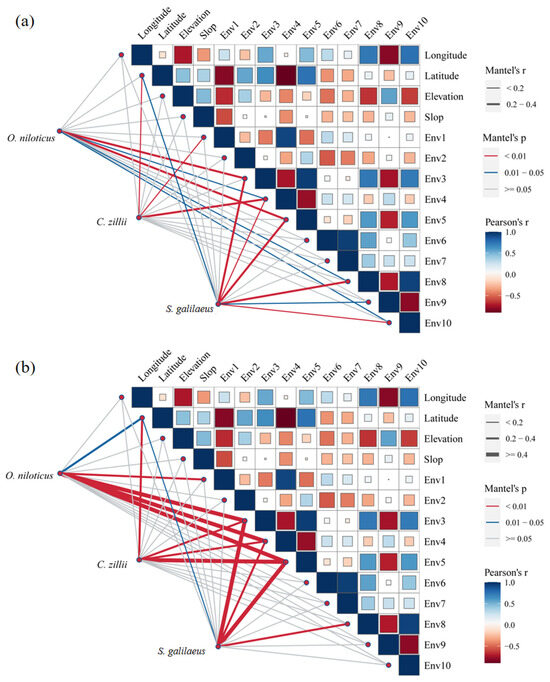

The Mantel test showed that the number of C. zillii was significantly correlated with latitude, annual mean temperature, and temperature seasonality, whereas the number of O. niloticus and S. galilaeus was significantly correlated with temperature seasonality, min temperature of coldest month, temperature annual range, precipitation of driest month, and precipitation of coldest quarter (Mantel’s p < 0.05). In addition, the number of S. galilaeus was also significantly correlated with latitude and precipitation seasonality (Mantel’s p < 0.05, Mantel’s r < 0.2) (Figure 6a). The numerical ratios of all three tilapia species were significantly correlated with latitude, temperature seasonality, min temperature of the coldest month, and annual temperature range (Mantel’s p < 0.05) (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Mantel test analysis of abundance of the three tilapia species and geographical factors and environmental factors (a) and Mantel test analysis of numerical ratios of the three tilapia species and geographical factors and environmental factors (b). ENV1, annual mean temperature; ENV2, mean diurnal range; ENV3, temperature seasonality; ENV4, min temperature of coldest month; ENV5, temperature annual range; ENV6, annual precipitation; ENV7, precipitation of wettest month; ENV8, precipitation of driest month; ENV9, precipitation seasonality; ENV10, precipitation of coldest quarter.

3.4. Responses to the Number of Three Tilapia Species

The results of the multicollinearity test of water environmental factors based on VIF showed that no serious collinearity was found in the nine environmental factors (VIF < 3) (Table 1). According to the AIC criterion, the best-fitting results of GAM for three tilapia species were obtained by the stepwise method (Table 2).

Table 1.

Multicollinearity test of water environmental factors based on VIF.

Table 2.

The best-fitting results of GAM for three tilapia species.

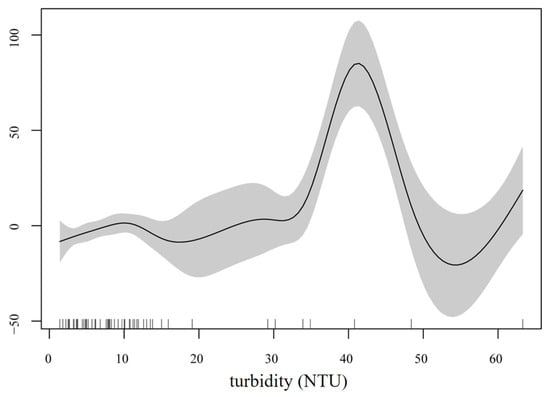

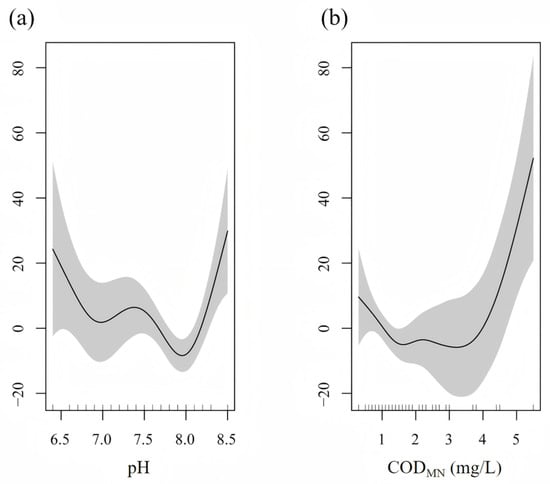

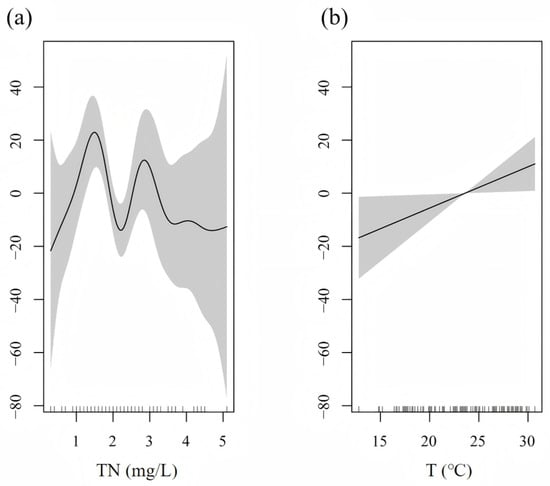

Turbidity was the explanatory variable in the optimal model of S. galilaeus, with a deviance of 57.9%, which had a significant impact on the number of S. galilaeus (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The number of S. galilaeus fluctuated with the change in turbidity, with the highest at 41 and the lowest at 53 (Figure 7). In the optimal model of O. niloticus, the explanatory variables were pH and CODMN, with a deviance of 28.7%, which had a significant impact on the number of O. niloticus (p < 0.05) (Table 2). When pH < 8, the number of O. niloticus decreased with the increase in pH, and when the pH > 8, the number increased with the increase in pH. The number decreased with the increase in CODMN when CODMN was <1.5 mg/L, did not change when CODMN was 1.5–4 mg/L, and increased rapidly with the increase in CODMN when CODMN was >4 mg/L (Figure 8). TN and water temperature were the explanatory variables in the optimal model of C. zillii, and the deviance was 19.1%, which had a significant impact on the number of C. zillii (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The number increased with the increase in water temperature. When TN was less than 1.5 mg/L, the number increased with the increase in TN, fluctuated between 1.5 mg/L and 3.5 mg/L, and gradually leveled off when TN was more than 3.5 mg/L (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Response of S. galilaeus number to turbidity based on the GAM model.

Figure 8.

Response of O. niloticus number to (a) pH, and (b) CODMN based on the GAM model.

Figure 9.

Response of C. zillii number to (a) TN, and (b) T based on the GAM model.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have identified five tilapia species in southern China [30]. In the inland waters of Guangxi, Coptodon zillii and Oreochromis niloticus are common species, and Sarotherodon galilaeus is relatively common but appears to be regional. Here, we conducted extensive sampling in the inland waters of Guangxi to collect data on three tilapia species. Among the tilapia specimens collected across 34 sites from the four seasons, C. zillii was the most abundant species, followed by O. niloticus and S. galilaeus. Similarly, a study investigating 20 sites in southern China reported comparable dominance patterns: among 3426 wild tilapia specimens, C. zillii accounted for 1789 individuals, followed by O. niloticus (1477) and S. galilaeus (113) [45]. Additionally, seasonal distribution patterns aligned with these abundance rankings. C. zillii was recorded at all 34 sampling sites, O. niloticus at 33 sites, and S. galilaeus at 25 sites (Figure 2b). These findings indicate that tilapia have colonized most inland river systems in Guangxi, with C. zillii and O. niloticus exhibiting particularly high occurrence frequencies. Notably, tilapia have become the dominant species in certain river sections [46].

The ecological advantages of C. zillii may stem from its high adaptability. This species exhibits rapid growth (growth rate: 0.38 per year; growth performance index: 2.73) and strong reproductive capacity, which likely compensate for the high exploitation rate to maintain population stability [47]. In shallow vegetated waters, C. zillii demonstrates significant competitive dominance through selective feeding (primarily aquatic plants) and spatial competition, restricting breeding grounds for other fish species. The small size and difficulty to catch compared to the O. niloticus make it not a much-appreciated fish species from both fisheries and aquaculture perspectives [48]. O. niloticus displays broader niche breadth; estimates of their diet using stable nitrogen and carbon isotopes revealed that when O. niloticus was present, the diet breadth of the C. zillii was narrower [49]. Spatial partitioning occurs between the two species: O. niloticus predominantly occupies sandy breeding substrates, while C. zillii favors rocky/vegetated habitats, thereby reducing direct interspecific competition in overlapping regions [50]. In addition, there may be some pattern of resource partitioning between them, as found by Zengeya et al. [51]. O. niloticus and O. mossambicus indicated high dietary overlap across size class, habitat, and season, but the interspecific differences in isotopic composition reveal fine-scale patterns of food resource partitioning that could be achieved through selective feeding. The limited distribution and low capture rates of S. galilaeus reflect its specialized ecological requirements. This species exhibits strong dependence on specific habitats and breeding conditions (e.g., sensitivity to water-level fluctuations). Hydrological variations directly influence its population dynamics, particularly through impacts on spawning success and juvenile survival [52]. These ecological mechanisms collectively shape the spatial distribution patterns of the three tilapia species in the inland waters of Guangxi (Figure 5).

The results showed that the number of the three tilapia species was highest in summer and lowest in winter (Figure 3). In the PCoA results, the dispersion degree of the summer fish combinations was the greatest extent, while winter dispersion is the least of the four seasons.(Figure 4). The three tilapia species being high in summer and low in winter may be caused by optimal thermal conditions and enhanced food availability. For example, O. niloticus thrives (growth and reproduction) in temperatures between 22 and 30 °C and exhibits reduced activity below 14 °C [53]. Similarly, C. zillii, a herbivore dependent on aquatic vegetation, benefits from summer phytoplankton blooms and macrophyte proliferation, which provide both food and spawning substrates [48]. In contrast, the tilapia numbers are low in winter, correlating with reduced primary productivity and metabolic suppression, particularly in temperate or subtropical systems where water temperatures drop below species-specific thresholds [54,55]. Spring and autumn are always located between summer and winter, possibly because they are transitional periods in which rising or falling temperatures gradually regulate physiological activities. This is consistent with studies showing that tilapia feeding rates, such as the GaSI index, peak during the breeding season to compensate for energy expenditure, as observed in Labeo rohita [56].

C. zillii was correlated with latitude and annual mild temperature seasonality, reflecting its ecological adaptability and reproductive strategies. Latitude gradients directly influence habitat selection by regulating mean annual temperature and seasonal temperature fluctuations. Temperature seasonality may play a role by regulating its reproductive cycle: field studies indicate that C. zillii spawning peaks in February, May, and September align with water temperature oscillations that trigger vitellogenesis and spawning behavior [48,57]. Additionally, its dependence on aquatic macrophytes heightens sensitivity to thermal variability, as seasonal fluctuations in plant biomass directly affect food resource stability [57]. For O. niloticus, distribution patterns are driven by temperature seasonality, minimum temperature of the coldest month, annual temperature range, and precipitation variables. As a highly invasive species, its broad thermal tolerance (14–33 °C) and salinity adaptability (0.015–30PSU) enable colonization of diverse habitats [53,58]. The strong correlation with the coldest month underscores its reliance on avoiding extreme cold for overwintering success, while adaptations to the annual temperature range involve metabolic rate adjustments and reproductive timing optimization [59]. Precipitation dynamics—specifically precipitation of the driest month and coldest quarter—reflect strategies to endure arid conditions: omnivory (primarily algae and detritus) sustains survival during low-water periods, while seasonal floods facilitate juvenile dispersal via expanded habitat connectivity [60]. S. galilaeus was not only affected by the temperature seasonality and the annual difference in the lowest mild temperature in the coldest month, but also significantly correlated with latitude and precipitation seasonality. Latitude exerts dual effects: elevated temperatures at lower latitudes promote growth, but excessive temperature seasonality may constrain reproductive windows, whereas mid-to-high latitude thermal fluctuations enhance population fitness through seasonally triggered spawning behaviors [61]. Precipitation seasonality influences habitat fragmentation and resource availability: concentrated rainfall during wet seasons expands habitat ranges and dispersal, while dry-season water contraction intensifies intraspecific competition and spatial redistribution [60,62,63].

The results of GAM showed that the number of S. galilaeus was mainly affected by turbidity (deviance explained 57.9%, p < 0.001), with the highest at 41 NTU and the lowest at 53 NTU, which was consistent with the mechanism of turbidity affecting the contrast between visual predators and prey. Utne-Palm [64] pointed out that moderate turbidity, such as 40 to 50 NTU, can reduce the predation efficiency of large carnivorous fish, while providing shelter for omnivorous fish, thereby improving their survival. Laboratory experiments conducted by Robertis et al. [65] showed that turbidity of 5–10 NTU could significantly reduce the success rate of attack of carnivorous fish, while planktivorous fish were less affected. The fluctuating response of S. galilaeus in this study may reflect a trade-off between optimal foraging conditions (medium turbidity) and predation risk (high turbidity). In addition, aquaculture studies have shown a positive correlation between turbidity and tilapia growth [66], but high turbidity in the natural environment may be accompanied by physical damage to the gills by suspended matter, resulting in the lowest abundance at 53 NTU. The number of O. niloticus was affected by both pH and CODMN (deviance of 28.7%, p < 0.05). When pH < 8, the number of O. niloticus decreased with the increase in pH, and when pH > 8, the number increased with the increase in pH. The number decreased with the increase in CODMN when CODMN was <1.5 mg/L, did not change when CODMN was 1.5–4 mg/L, and increased rapidly with the increase in CODMN when CODMN was >4 mg/L. The response of CODMN may reflect its adaptability to organic pollutants. CODMN often reflects the content of oxidative organic matter in water. Low concentrations may inhibit fish metabolism, while high concentrations may be accompanied by eutrophication or microbial degradation products, while O. niloticus maintains its population through omnivorous feeding strategies (such as algae and debris) [67]. The number of C. zillii was affected by TN and water temperature (deviance explained 19.1%, p < 0.05), which increased with the increase in water temperature. The number increased with the increase in TN when TN was <1.5 mg/L, fluctuated when TN was 1.5–3.5 mg/L, and gradually became flat when TN was >3.5 mg/L. The number increased with increasing water temperature, reflecting the characteristics of C. zillii as an eurytherm species. The response to TN may be related to the nitrogen form and resource competition: low concentrations of TN promote primary productivity [68], while medium and high concentrations may lead to nitrate accumulation or algal community transformation, leading to interspecific resource competition [69].

5. Conclusions

In the total number of the three tilapia species, the number of C. zillii exceeded 50%, while C. zillii and O. niloticus were widely distributed in the inland waters of Guangxi with a high frequency of occurrence. The total and respective numbers of the three tilapia species were highest in summer. C. zillii was dominant in the northern study area, and there was no distribution of S. galilaeus, while the proportion of S. galilaeus and O. niloticus increased as the latitude moved south. The distribution of the three tilapia species was not only influenced by their ecological fitness and reproductive characteristics but also driven by latitude and seasonal temperature. In addition, the number of the three tilapia species was also affected by water environmental factors. S. galilaeus was affected by turbidity, O. niloticus was affected by pH and CODMN, and C. zillii was affected by TN and water temperature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; methodology, L.Q., J.H., Y.S., H.L. and Y.L.; software, L.Q. and Y.S.; formal analysis, J.H., H.L. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and X.B.; writing—review and editing, H.L., L.H., X.B. and Z.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W., X.B. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060830); Key Research and Development Program of Guangxi (AB22035050); Survey of Fishery Resources in Guangxi (GXZC2022-G3-001062-ZHZB); Open Fund Jointly Supported by the MARA Key Laboratory of Comprehensive Development and Utilization of Aquatic Genetic Resources (China (Guangxi)-ASEAN) (Ministry-Province Co-construction) and Guangxi Key laboratory of Aquatic Genetic Breeding and Healthy Aquaculture (GXKEYLA-2023-01-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the The Animal Research and Ethics Committees of Guilin University of Technology (protocol code GLUT-EAEC2023001 and 26 July 2024).

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Guangxi Key Laboratory of Environmental Pollution Control Theory and Technology, Guangxi Collaborative Innovation Center for Water Pollution Control and Water Safety in Karst Areas, and Guangxi Academy of Fishery Sciences for their vital help during samplings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gallardo, B.; Clavero, M.; Sànchez, M.I.; Vilà, M. Global ecological impacts of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, A.S.; Breon, K. The greatest threats to species. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e12670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.; Browne, M.; Boudjelas, S.; De Poorter, M. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species. A Selection from the Global Invasive Species Database; The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) a Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the World Conservation Union (IUCN): Auckland, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Luque, G.; Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Bonnaud, E.; Genovesi, P.; Simberloff, D.; Courchamp, F. The 100th of the world’s worst invasive alien species. Biol. Invasions 2014, 16, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, I.; Abell, R.; Darwall, W.; Thieme, M.L.; Tickner, D.; Timboe, I. The freshwater biodiversity crisis. Science 2018, 6421, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, J.S.; Destouni, G.; Duke-Sylvester, S.M.; Magurran, A.E.; Oberdorff, T.; Reis, R.E.; Winemiller, K.O.; Ripple, W.J. Scientists’ warning to humanity on the freshwater biodiversity crisis. Ambio 2020, 50, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A.H.; Gessner, M.O.; Kawabata, Z.I.; Knowler, D.J.; Lévéque, C.; Naiman, R.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.H.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M.L.J.; et al. Freshwater biodiversity: Importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 2006, 81, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Kidd, K.A.; MacCormack, T.J.; Olden, J.D.; Ormerod, S.J.; et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 2019, 3, 849–87394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glozan, R.E. Introduction of non-native freshwater fish: Is it all bad? Fish Fish. 2008, 9, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ellender, B.R.; Weyl, O.L.F. A review of current knowledge, risk and ecological imports associated with non-native freshwater fish introductions in South Africa. Aquat. Invasions 2014, 9, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Vitule, J.R.S.; Li, S.; Shuai, F.; Huang, L.; Huang, X.; Huang, X.; Fang, J.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Introduction of non-native fish for aquaculture in China: A systematic review. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 15, 676–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhan, A. Introduction and use of non-native species for aquaculture in China: Status, risks and management solutions. Rev. Aquac. 2015, 7, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020-Sustainability in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trewavas, E. Tilapiine Fishes of the Genera Sarotheredon, Oreochromis and Danakilia; British Museum (Natural History): London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bhassu, S.; Yusoff, K.; Panandam, J.M.; Embong, W.K.; Oyyan, S.; Tan, S.G. The genetic structure of Oreochromis spp (Tilapia) populations in Malaysia as revealed by microsatellite DNA analysis. Biochem. Genet. 2004, 42, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attayde, J.L.; Brasil, J.; Menescal, R.A. Impacts of introducing Nile tilapia on the fisheries of a tropical reservoir in North-Eastern Brazil. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2011, 18, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.W.; Valentine, M.M.; Valentine, J.F. Competitive interactions between invasive Nile tilapia and native fish: The potential for altered trophic exchange and modification of food webs. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammer, G.L.; Slack, W.T.; Peterson, M.S.; Dugo, M.A. Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) establishment in temperate Mississippi, USA: Multi-year survival confirmed by otolith ages. Aquat. Invasions 2012, 7, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.; Subasinghe, R.P.; Bartley, D.M.; Lowther, A. Tilapias as Alien Aquatics in Asia and the Pacific: A Review; FAO Fisheries Technical Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Lu, M.; Huang, Z. New Practical Techniques to Healthful Aquaculture of Tilapia; Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fishery Department of Ministry of Agriculture of China. China Fishery Statistical Yearbook; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Xie, J.; Yu, D.; Gng, W. Present status of tilapias culture in China mainland. Open J. Fish. Res. 2014, 1, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, F.; Li, J. Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus Linnaeus, 1758) Invasion Caused Trophic Structure Disruptions of Fish Communities in the South China River-Pearl River. Biology 2022, 11, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Naylor, R.; Henriksson, P.; Leadbitter, D.; Metian, M.; Troell, M.; Zhang, W. China’s aquaculture and the world’s wild fisheries. Science 2015, 347, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Mu, X.; Wei, H.; Yu, F.; Fang, M.; Wang, X.; Song, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Does aquaculture aggravate exotic fish invasions in the rivers of southern China? Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengeya, T.A.; Robertson, M.P.; Booth, A.J.; Chimimba, C.T. Ecological niche modeling of the invasive potential of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus in African river systems: Concerns and implications for the conservation of indigenous congenerics. Biol. Invasions 2013, 15, 1507–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deines, A.M.; Wittmann, M.E.; Deines, J.M.; Lodge, D.M. Tradeoffs among ecosystem services associated with global tilapia introductions. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2016, 24, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thodesen, J.; Rye, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Bentsen, H.B.; Gjedrem, T. Genetic improvement of tilapias in China: Genetic parameters and selection responses in growth, pond survival and cold-water tolerance of blue tilapia (Oreochromis aureus) after four generations of multi-trait selection. Aquaculture 2013, 322, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, Y.; He, Y.; Duan, X. Consumer perception of tilapia in China and related factors. N. Am. J. Aquac. 2022, 84, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Mu, X.; Xu, M.; Luo, D.; Wei, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, J.; Hu, Y. Identification of wild tilapia species in the main rivers of south China using mitochondrial control region sequence and morphology. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2016, 65, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Yu, F.; Xu, M.; Wei, H.; Mu, X.; Luo, D.; Xin, Y.; Pan, Y.; Hu, Y. Temperature effects on the distribution of two invasive tilapia species (Tilapiazillii and Oreochromisniloticus) in the rivers of South China. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2018, 33, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhuo, X.; Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Wei, X.; Ji, J. Ecological risk assessment of Cd and other heavy metals in soil-rice system in the karst areas with high geochemical background of Guangxi, China. Sci. China Earth. Sci. 2021, 64, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Lan, Y.; Zhou, G.; You, H.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X. Landscape Pattern and Ecological Risk Assessment in Guangxi Based on Land Use Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Li, H.; Yang, L.; Zhong, G.; Zhang, L. Socio-Economic Factors of Bacillary Dysentery Based on Spatial Correlation Analysis in Guangxi Province, China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Wang, J.; Gao, L.; Hong, Y.; Huang, J.; Lu, Q. Observed trends of different rainfall intensities and the associated spatiotemporal variations during 1958–2016 in Guangxi, China. Int. J. Climatol 2021, 41, E2880–E2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, R.; Shao, J. Assessment of Regional Spatiotemporal Variations in Drought from the Perspective of Soil Moisture in Guangxi, China. Water 2022, 14, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Hao, X.; Gu, D. Exotic Aquatic Plants and Animals in China; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Dong, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. The Manual for Identifying Common Exotic Aquatic Organisms in China; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Amatulli, G.; Domisch, S.; Tuanmu, M.-N.; Parmentier, B.; Ranipeta, A.; Malczyk, J.; Jetz, W. A suite of global, cross-scale topographic variables for environmental and biodiversity modeling. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C. Some distance properties of latent root and vector methods used in multivariate analysis. Biometrika 1966, 53, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.; Wei, T. ggcor: Extended Tools for Correlation Analysis and Visualization, R package version 0.9.7; 2020. Available online: https://github.com/tanyongjun0815/ggcor (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Zhang, S.; Zhi, T.; Xu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Bilong, C.F.B.; Pariselle, A.; Yang, T.B. Monogenean fauna of alien tilapias (Cichlidae) in south China. Parasite 2019, 26, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, F.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Lek, S. Spatial patterns of fish assemblages in the Pearl River, China: Environmental correlates. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 2017, 189, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, S. Length Based-stock assessment and Spawning Potential Ratio (LB-SPR) of exploited tilapia species (Coptodon zilli, Gervais, 1848) in Lake Volta, Ghana. J. Limnol. Freshw. Fish. Res. 2023, 9, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Geletu, T.T.; Tang, S.J.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, J.L. Ecological niche and life-history traits of redbelly tilapia (Coptodon zillii, Gervais 1848) in its native and introduced ranges. Aquat. Living Resour. 2024, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.M.; Wandera, S.B.; Thacker, R.J.; Dixon, D.G.; Hecky, R.E. Trophic niche segregation in the Nilotic ichthyofauna of Lake Albert (Uganda, Africa). Environ. Biol. Fishes 2005, 74, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gownaris, N.J.; Pikitch, E.K.; Ojwang, W.O.; Michener, R.; Kaufman, L. Predicting Species’ Vulnerability in a Massively Perturbed System: The Fishes of Lake Turkana, Kenya. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengeya, T.A.; Booth, A.J.; Bastos, A.D.S.; Chimimba, C.T. Trophic interrelationships between the exotic Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus and indigenous tilapiine cichlids in a subtropical African river system (Limpopo River, South Africa). Environ. Biol. Fishes 2011, 92, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, R. Growth and population studies on Tilapia galilaeus in Lake Kinneret. Freshw. Biol. 1979, 9, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Abubakar, M. Intensive Animal Farming—A Cost-Effective Tactic; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dallas, H. Water temperature and riverine ecosystems: An overview of knowledge and approaches for assessing biotic responses, with special reference to South Africa. Water SA 2018, 34, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X. Seasonal characteristics of thermal stratification in Lake Tianchi of Tianshan Mountains. J. Lake Sci. 2015, 27, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandita, S.; Ujjania, N.C. Seasonal variation in food and feeding habit of Indian major carp (Labeo rohita Ham.1822) in Vallabhsagar reservoir, Gujarat. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2017, 9, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N.A. Substratum preferences of juvenile Red belly Tilapia (Coptodon zilli, Gervais, 1848). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 779, 012128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.O.; Ismail, A.; Zulkifli, S.Z.; Ghani, I.F.A.; Halim, M.R.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Mukhtar, A.; Aziz, A.A.; Wahid, N.A.A.; Amal, M.N.A. Invasion Risk and Potential Impact of Alien Freshwater Fishes on Native Counterparts in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Animals 2021, 11, 3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, S.L.; Schoettle, A.W.; Coop, J.D. The future of subalpine forests in the Southern Rocky Mountains: Trajectories for Pinus aristata genetic lineages. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvano, J.; Oliveira, C.L.C.; Fialho, C.B.; Gurgel, H.C.B. Reproductive period and fecundity of Serrapinnus piaba (Characidae: Cheirodontinae) from the rio Ceará Mirim, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. Neotrop. Ichthyol. 2003, 1, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Barbacil, C.; Radinger, J.; García-Berthou, E. Interacting effects of latitudinal and elevational gradients on the distribution of Iberian inland fish. Limnetica 2023, 43, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.R.; Aranha, J.M.R.; Vitule, J.R. Reproduction period of Mimagoniates microlepis, from an Atlantic Forest Stream in Southern Brazil. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2008, 51, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xie, W.; Li, T.; Wu, G.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Song, H.; Yang, Y.; Pan, X. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Variation in Water Coverage in the Sub-Lakes of Poyang Lake Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utne-Palm, A.C. Visual feeding of fish in a turbid environment: Physical and behavioural aspects. Mar. Behav. Physiol. 2002, 35, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Robertis, A.; Ryer, C.H.; Veloza, A.; Brodeur, R.D. Differential effects of turbidity on prey consumption of piscivorous and planktivorous fish. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2003, 60, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumwesigye, Z.; Tumwesigye, W.; Opio, F.; Kemigabo, C.; Mujuni, B. The effect of water quality on aquaculture productivity in Ibanda District, Uganda. Aquac. J. 2022, 2, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, P.; Liu, Z. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research. Ecol. Sci. 2008, 27, 494–498, (In Chinese, English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz-Sousa, J.; Keith, S.A.; David, G.S.; Brandao, H.; Nobile, A.B.; Paes, J.V.K.; Souto, A.C.; Lima, F.P.; Silva, R.J.; Henry, R.; et al. Species richness and functional structure of fish assemblages in three freshwater habitats: Effects of environmental factors and management. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 95, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullian-Klanian, M.; Aramburu-Adame, C. Performance of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus fingerlings in a hyper-intensive recirculating aquaculture system with low water exchange. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2013, 41, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).