Abstract

Non-indigenous species represent a significant threat to marine biodiversity, and accurate taxonomic identification is critical for effective management. This study revisits the long-standing record of the Australian sea anemone Oulactis muscosa in Argentina, which has been cited in numerous studies for nearly 50 years. We conducted a comprehensive taxonomic revision of specimens from Mar del Plata, Argentina, using both morphological and molecular analyses. Our findings reveal a persistent taxonomic error: the specimens belong to a different species. Detailed morphological comparisons and genetic sequencing of mitochondrial and nuclear markers re-identified the specimens as Anthopleura correae. This species is native to Brazil and is distributed from Ceará to Santa Catarina. This represents the first record of an Anthopleura species in Argentina, extending its known distribution. Genetic analyses confirmed the re-identification, showing no significant divergence between the Argentine and Brazilian specimens, while revealing notable differences from O. muscosa. We highlight the importance of rigorous taxonomic approaches integrating both morphological and molecular data to prevent misidentifications, which is particularly crucial when identifying potential invasive species. This study clarifies the taxonomic status of a regionally distributed species and contributes to the accurate inventory of sea anemones in Argentina.

1. Introduction

Non-indigenous invasive species are widely recognized as one of the primary threats to biodiversity in marine environments due to their significant impacts on local populations and their ability to drastically alter food webs, natural resources, and ecosystems [1]. Accurate taxonomic identification of these species is crucial, as misidentifications can lead to unpredictable consequences for biological communities and management efforts [2]. In this context, we present the case of the sea anemone Oulactis muscosa (Drayton in Dana, 1846) [3], a species first described and native to Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia [4], whose record in Argentina has been reassessed in light of recent evidence.

In 1977, Dr. Mauricio Zamponi, a pioneer in the taxonomic, biological, and ecological study of cnidarians in Latin America, published a foundational study on the sea anemone fauna of Argentina, with special emphasis on the species inhabiting the coasts of Mar del Plata [5]. In this study, Zamponi described the new species Aulactinia marplatensis (Zamponi, 1977) and documented five new records of sea anemones from the country, including Oulactis muscosa [5]. He based his identification of O. muscosa on comparisons with previous studies by Carlgren [6], Parry [7], and Cutress [8], at a time when taxonomic information on many species was limited and resources such as photographs of live specimens were scarce or nonexistent. Following Zamponi’s work, O. muscosa became the subject of several studies in Argentina, including research on its reproductive strategies [9], population and trophic structure [10], and variability in cnidocyst types [11,12]. Prior to the present study, no research had questioned the species’ taxonomic identity or compared it to specimens from Australia. Even Orensanz et al. [13] included O. muscosa in the first inventory of marine exotic species introduced to Argentina, alongside other sea anemone species such as Bunodactis reynaudi (Milne-Edwards, 1857) [14] and Boloceroides mcmurrichi (Kwietniewski, 1898) [15], both previously reported by Zamponi [5].

More recent studies by Fautin et al. [16] and Mitchel [17], who provided detailed images of Oulactis muscosa from its documented distribution range—extending from Spencer Gulf in southern Australia to southern Queensland, including the coasts of Tasmania— and from New Zealand, revealed significant differences between the Australian specimens and those recorded in Argentina. These differences are mainly evident in that the Argentine specimens lack the frond-like projections on the marginal part of the column, which are characteristic of Oulactis [18]. This prompted us to carry out an exhaustive taxonomic revision of the Argentine specimens previously identified as O. muscosa, based on morphological characteristics (external and internal anatomy, cnidocyst types) and genetic analyses of mitochondrial (i.e., 12S, 16S, COX3) and nuclear markers (i.e., 18S, 28S). We used recently published sequences of O. muscosa from New Zealand [19], as well as new sequences of Oulactis coliumensis (Riemann-Zürneck & Gallardo, 1990) [20] from Chile, as references for the genus Oulactis.

Our results reveal that the sea anemone specimens collected in Mar del Plata, previously identified as O. muscosa, actually belong to a species of the genus Anthopleura Duchassaing de Fonbressin & Michelotti, 1860 [21]. In fact, they belong to a species native to Brazil previously known as Anthopleura cascaia (nomen nudum), which was recently renamed as Anthopleura correae Durán-Fuentes, González-Muñoz, Vassallo-Ávalos, Delgado, Daly & Stampar, 2025 [22], with a known previous distribution extending from Ceará to Santa Catarina [22]. This finding represents the first record of an Anthopleura species in Argentina, thereby extending its distribution from Brazil to Mar del Plata. Additionally, we correct a taxonomic identification error that has persisted for nearly half a century. We provide a morphological and genetic diagnosis of the A. correae specimens found in Mar del Plata. Moreover, we emphasize the importance of conducting rigorous taxonomic analyses that integrate both morphological and molecular approaches. This combined strategy enables precise species identification, the establishment of new records, and the reliable documentation of distribution range extensions. Such analyses are particularly critical in the case of introduced exotic species, as their potential ecological impact heavily depends on accurate identification. Finally, we discuss the taxonomic status of other sea anemone species that have been reported as exotic invasive species in Argentina.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preservation

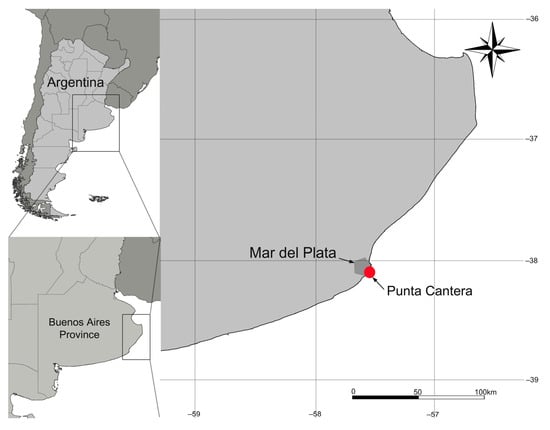

In November 2020, 30 sea anemone specimens of the putative species Oulactis muscosa were collected at Punta Cantera (38°04′ S–57°32′ W), Playa Waikiki, on the coast of Mar del Plata, Argentina (Figure 1). The specimens were collected from the intertidal zone with the help of a hammer and chisel, and were later transferred to the laboratory, where they were placed in aquariums to document their color patterns while alive. The specimens were then anesthetized in a 5% MgCl2 solution in seawater. Tissue samples were taken from the pedal disc of each collected specimen and placed in 96% ethanol for subsequent DNA extraction. Specimens were later fixed in a 10% formalin solution in seawater for two months and then transferred to a 70% alcohol solution for preservation.

Figure 1.

Map showing the sampling locality on the coast of Mar del Plata, Argentina, where the specimens of Anthopleura correae were collected.

2.2. Morphological Analyses

Specimens were examined under a stereomicroscope (mod. Leica EZ4-W (Leica Microsystems, Heerbrugg, Switzerland)). Measurements were taken of the pedal disc diameter, the length and width of the column, the diameter of the oral disc, and the length of the longest tentacles in all fixed specimens. For the analysis of internal structure, all specimens were dissected. Selected fragments from four specimens were embedded in paraffin to prepare transverse and longitudinal histological sections, 5–8 µm thick, which were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The histological preparations were examined under a light microscope (Leica DM-500). For the cnidom analysis, small tissue samples (2 mm3) were taken from the column, tentacles, marginal projections with acrorhagi, mesenteric filaments, and actinopharynx of five specimens. Samples were placed on separate slides, squashed with a coverslip using the squash method, and observed under a light microscope. For each preparation, photographs were taken, and at least 20 capsules of each cnidocyst type found in each tissue were measured haphazardly. The length and width of each capsule were measured using Leica Application Suite software v3.4. The nomenclature of Östman [23] was used for the identification of cnidocysts types, and the classification of Rodríguez et al. [24] was followed. The specimens were deposited in the Collection of Anthozoans of the Southern Atlantic (CAAS) [25], at the Cnidarian Biology Laboratory (IIMyC, National University of Mar del Plata-CONICET) under the reference code IIMyC-CNI:000074.

2.3. DNA Extraction and Amplification of Genetic Markers

Total genomic DNA was isolated from two specimens of the putative O. muscosa collected in Mar del Plata (coded as yellow-ARG and pink-ARG) and from three specimens of O. coliumensis, using a QIAamp® DNA Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Mitochondrial markers 12S rRNA (≈824 bp), 16S rRNA (≈428 bp), and cytochrome c oxidase subunit III (COX3; ≈636 bp), as well as the nuclear markers 18S rRNA (≈2016 bp) and 28S rRNA (≈3608 bp), were amplified and sequenced following the primers and PCR profiles outlined by Brugler et al. [26]. All DNA extraction, amplification, purification, and Sanger sequencing (both forward and reverse) were performed by Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea).

2.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

The forward and reverse sequences of the five genetic markers were assembled and edited using Geneious Prime version 2023.0.4 [27]. These sequences were then compared against the GenBank nucleotide database [28] using the BLAST algorithm (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 19 March 2025) [29] to confirm the successful amplification of the target markers. The new DNA sequences were combined and aligned with the dataset presented by Durán-Fuentes et al. [22], as that study includes representatives of most genera with acrorhagi, as well as various other groups within superfamily Actinioidea that exhibit verrucae on their columns. In addition, sequences from A. correae, obtained from specimens collected in Ubatuba, Brazil, and of O. coliumensis, collected in Tocopilla (22°03′54″ S–70°11′48″ W), Chile, as well as sequences of Oulactis muscosa from New Zealand, were included. These sequences were presented in the study by Larson & Daly [19] and are available in GenBank [28]. The new sequences of Anthopleura correae and Oulactis coliumensis from 12S, 16S, COX3, 18S and 28S were deposited in GenBank [28] (Supplementary Material S1).

Sequences for each marker were aligned separately using MAFFT v7.53 with the L-INS-I algorithm and the “--maxiterate 1000” option [30]. The concatenated dataset was generated using SequenceMatrix v1.8 [31]. Maximum likelihood (ML) reconstruction was performed with IQ-Tree2 v2.3.6 [32], employing a concatenation approach with a linked proportional partition model. The best-fit evolutionary model for each partition was selected using ModelFinder [33] within IQ-Tree2. Branch support was assessed using 1000 replicates of the SH-like approximate likelihood radio test (SH-aLRT) [34], 1000 replicates of ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot2) [35], as well as parametric aLRT tests [36] and approximate Bayesian tests [37]. Partitioning schemes and evolutionary models were selected based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) as implemented in ModelFinder within IQ-Tree2. The resulting trees were visualized and edited using TreeGraph v2 [38].

We compared genetic divergence between the two sequences of the putative O. muscosa from Mar del Plata and the sequences of A. correae and other Oulactis species for each of the five markers separately. Pairwise genetic distances were estimated using the Kimura two-parameter (K2P) model [39] in MEGA11 [40]. The analysis included 1000 bootstrap replicates and considered both transitions and transversions. A gamma distribution was used to model rate variation among sites, with a shape parameter of 1. The final dataset comprised 952 base pairs for 12S, 554 for 16S, 727 for COX3, 2577 for 18S, and 4314 for 28S, totaling 9128 base pairs.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Analyses

All examined specimens of the putative Oulactis muscosa from Mar del Plata exhibited 96 tentacles, longitudinal endocoelic rows of adhesive verrucae on the column, and acrorhagi on the margin—features also documented in specimens of O. muscosa from Australia and New Zealand [16,17]. However, the marginal region of the column in the examined specimens lacks the frond-like papillae located on both endocoelic and exocoelic lobes, which are characteristic of the genus Oulactis [18]. Instead, they present simple endocoelic marginal projections (not situated on lobes), which generally bear acrorhagi on their oral surface. These features are associated with the genus Anthopleura [41]. Among the species of Anthopleura reported from the region, the examined specimens display taxonomic characteristics consistent with those of Anthopleura correae, both in external and internal morphology, as well as in cnidae.

3.2. Taxonomic Treatment

Order ACTINIARIA Hertwig, 1882 [42]

Suborder ENTHEMONAE Rodríguez and Daly, 2014 [24]

Superfamily ACTINIOIDEA Rafinesque, 1815 [43]

Family ACTINIIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 [43]

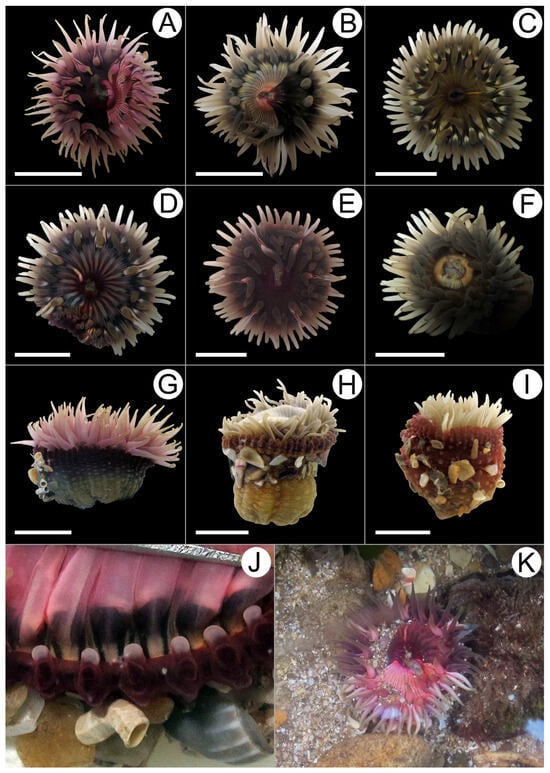

Figure 2.

External morphology of Anthopleura correae. (A–F) Distal views showing different color patterns of the oral disc. (G–I) Lateral views of specimens showing different color patterns of the column; note the mollusk shell fragments attached to the verrucae. (J) Distal view of the column showing marginal projections and acrorhagi (whitish spheroids). (K) In situ image of A. correae. Scale bar = 10 mm.

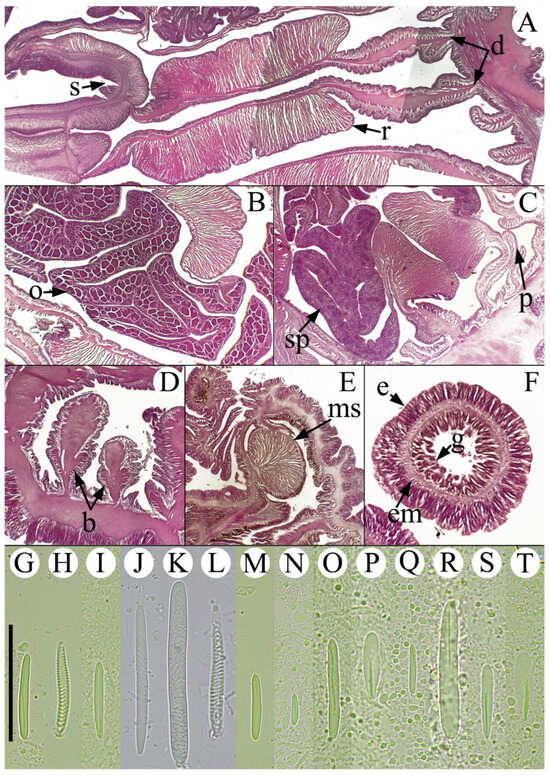

Figure 3.

Internal morphology and cnidome of Anthopleura correae. (A) Transverse section of the upper column showing a siphonoglyph and a pair of directive mesenteries. (B) Transverse section of the upper column showing oocytes in a mesentery. (C) Transverse section of the upper column showing spermaries in a mesentery. (D) Longitudinal section of the proximal end showing basilar muscles. (E) Longitudinal section of the column margin showing the marginal sphincter muscle. (F) Transverse section of a tentacle showing ectodermic musculature. Abbreviatures—b: basilar muscles, d: directive mesenteries, e: epidermis, em: ectodermic muscles, g: gastrodermis, ms: marginal sphincter, o: oocytes, p: parietobasilar muscles, r: retractor muscles, s: siphonoglyph, sp: spermaries. Cnidome: Tentacles—(G) basitrich, (H) spirocyst. Acrorhagi—(I) basitrich, (J) holotrich I, (K) holotrich II, (L) spirocyst. Column—(M) basitrich. Actinopharynx—(N) basitrich, (O) basitrich, (P) p-mastigophore A. Filaments—(Q) basitrich, (R) b-mastigophore, (S) p-mastigophore B1, (T) p-mastigophore A. Scale bars (A–F) = 200 μm; (G–T) = 20 μm.

Material examined. Thirty specimens collected at Waikiki beach, Mar del Plata.

Short description. Oral disc flat, broad, smooth (Figure 2A–F,K). Tentacles arranged hexamerously in five cycles (96 total); simple, smooth, conical, inner cycles slightly longer than outer ones (Figure 2A–I). Column cylindrical or cup-shaped, often wider distally (8–49 mm wide, 10–40 mm height) (Figure 2G–I). Column with 48 longitudinal endocoelic rows of adhesive verrucae, extending from distal end to limbus (Figure 2G–I). Each row of verrucae ends distally in a small, simple, conical marginal projection; in most cases, each marginal projection bears a whitish acrorhagus on its oral face (Figure 2J), directed inward into fosse, sometimes absent. Pedal disc well developed, 10–50 mm in diameter in preserved specimens, strongly adherent. Mesenteries arranged hexamerously in four cycles (48 pairs). Same number of mesenteries in both distal and proximal regions. First three cycles of mesenteries perfect at the actinopharynx level; fourth cycle imperfect and poorly developed, lacking retractor muscles and mesenterial filaments. Two pairs of directive mesenteries, each associated with a well-developed siphonoglyph (Figure 3A). Gametogenic tissue present in nearly all mesenterial pairs of first three cycles, including directives; gonochoric (Figure 3B,C). Retractor muscles restricted and strong (Figure 3A–C); parietobasilar muscles well-developed (Figure 3C), with a free mesogleal lamella. Basilar muscles well developed (Figure 3D). Marginal sphincter muscle endodermal, strong and well-developed, circumscribed, palmate (Figure 3E). Longitudinal muscles of tentacles ectodermal (Figure 3F). Azooxanthellate.

Cnidom (Figure 3G–T). Tentacles: basitrichs (7.5–27.1 µm × 1.8–3.6 µm), spirocysts (19.7–28.7 µm × 2.9–4.5 µm). Acrorhagi: basitrichs (13.2–23.3 µm × 1.8–3.0 µm), holotrichs I (33.6–72.6 µm × 3.0–4.4 µm), holotrichs II (52.3–73.5 µm × 5.1–8.5 µm), spirocysts (31.9 µm × 4.1 µm). Column: basitrichs (8.8–23.56 µm × 1.8–3.5 µm). Actinopharynx: basitrichs I (15.9–20.6 µm × 2.4–2.7 µm), basitrichs II (21.5–30.2 µm × 3.5–4.0 µm), p-mastigophores A (14.6–21.2 µm × 4.0–5.8 µm). Mesenterial filaments: basitrichs (6.3–24.1 µm × 1.9–2.7 µm), b-mastigophores (30.6–50.5 µm × 4.3–7.3 µm), p-mastigophores B1 (17.6–22.0 µm × 4.1–6.2 µm), p-mastigophores A (17.2–24.4 µm × 2.9–4.4 µm).

Coloration patterns. Anthopleura correae exhibits a high degree of color polymorphism which is characteristic of this species throughout its native range [22]. Oral disc may be “unicolor” or “bicolor”, resembling the face of a clock. When bicolor, it may display a light pink area and a dark burgundy area (Figure 2A,K), or a light yellow area and a dark brown area (Figure 2B). When unicolor, it may be dark green (Figure 2C) or dark burgundy (Figure 2E), with or without a whitish radial line (Figure 2A–F). In some cases, the mouth and its perimeter are pale yellow (Figure 2F) or orange. In others, radial lines alternate between light and dark green, or between pale grayish burgundy and dark burgundy (Figure 2D), marking the mesenterial insertions. Tentacles are light gray or pale beige, sometimes with a pink cast (Figure 2A–I). Occasionally, small whitish spots are present at their bases, and in other cases, tiny white dots are scattered along the oral surface. Column is dark burgundy, dark brown, or dark orange distally and at the margin, becoming lighter towards the middle and proximal regions, where it appears light olive green, grayish green, pale brown, or light reddish (Figure 2G–I). Verrucae are generally the same color as the column (Figure 2H), though sometimes slightly lighter or whitish. Acrorhagi whitish (Figure 2J). Pedal disc of the same color as the proximal portion of the column, occasionally slightly lighter.

Distribution and Natural History. Anthopleura correae is distributed primarily along the Brazilian coast, from Ceará to Santa Catarina [22]. This is the first record of the species in Argentina, on the coast of Mar del Plata. This species inhabits intertidal zones and adheres to hard, rocky substrates (Figure 2K). Like other Anthopleura species, A. correae attaches small pieces of shell, rock, and sand to the verrucae on its column, which help delay desiccation when the animal is exposed during low tides.

3.3. Molecular Analyses

3.3.1. Comparison of Genetic Markers

The pairwise genetic divergence analysis shows no differences between the three mitochondrial marker sequences of A. correae from Brazil and those from A. correae from Argentina, which supports the taxonomic identification based on morphological characters. The same result was found for the nuclear marker 18S, with no differences observed between the sequences. However, the 28S marker differs by 0.11% in one of the A. correae samples from Argentina (i.e., pink-ARG) compared to the sequences of A. correae from Brazil, while no differences were found for the other sample (Table 1). On the other hand, the comparison of sequences between A. correae from Argentina and the available sequences of O. muscosa shows a genetic divergence ranging from 0.13% to 2.7% for mitochondrial markers, and from 0.11% to 0.23% for nuclear markers. In the case of the comparison between O. coliumensis and A. correae from Argentina, genetic divergence ranges from 0.38% to 2.02% for mitochondrial markers (except for COX3, which showed no differences with A. correae from Argentina) and from 5.4% to 5.5% for nuclear markers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated genetic divergence (K2P, expressed as percentages) between Anthopleura correae from Argentina and A. correae from Brazil, Oulactis muscosa, and Oulactis coliumensis, based on comparisons of sequences from three mitochondrial markers and two nuclear markers.

3.3.2. Phylogenetics Analyses

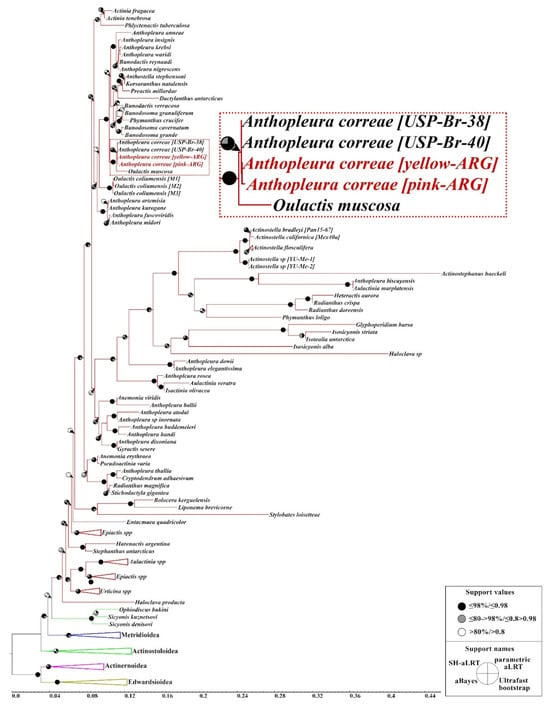

Phylogenetic reconstruction based on maximum likelihood analysis of molecular data confirmed that A. correae from Argentina and Brazil are a monophyletic clade, providing strong evidence that they are conspecific. However, O. muscosa appears as the sister group to this clade, with strong support, while O. coliumensis forms a separate, more distantly related group, although it is also included within the Actiniidae, along with species of the genera Anthopleura, Bunodosoma, and Actinia, among others (Figure 4; Supplementary Material S2). The broader phylogenetic relationships among other Actiniaria taxa were found to be consistent with the results published by Durán-Fuentes et al. [22].

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic reconstruction based on maximum likelihood analysis of Anthopleura correae within the order Actiniaria using a concatenated dataset of conventional markers (12S, 16S, 18S, 28S, COX3).

4. Discussion

According to the most current definitions of Anthopleura and Oulactis, both genera include species that possess adhesive verrucae on the column and marginal projections with acrorhagi [6,18,41,44]. These genera mainly differ in that the marginal projections in Anthopleura are simple and endocoelic, whereas in Oulactis they are papillary, frond-like, and located on both endocoelic and exocoelic lobes, forming a frondose collar referred to by some authors as a “marginal ruff” [18]. This characteristic was likely overlooked or misinterpreted by Zamponi [5] when he identified the species as O. muscosa. Zamponi [5] primarily relied on the works of Parry [7] and Cutress [8] for the identification of this species. Parry [7] noted that species of Oulactis have a smooth column in the lower portion, but the distal portion bears longitudinal rows of verrucae which, just below the margin, are small and densely arranged on small lobes of the column, forming frond-like structures. Cutress [8] made no mention of the morphology of the column structures, and neither of these two studies included schematic drawings or photographs of the species. It is likely that differences in interpretation or the uneven depth in the description of these structures and other characters may have led to errors in the taxonomic identification of the species based on morphological traits.

In the present study, we were able to correct these taxonomic errors by identifying the species as Anthopleura correae based on morphological characters, and we further confirmed this identification with molecular data. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the phylogenetic tree based on molecular data recovers Oulactis muscosa as the species most closely related to A. correae, rather than grouping it with another species of Anthopleura. In fact, O. muscosa is also not recovered as closely related to O. coliumensis. These associations are difficult to explain with the data currently available. However, upon examining the sequences of O. muscosa, we observed several ambiguous sites across the sequences of each of the markers used in the comparisons (i.e., 18 sites in 952 bp for 12S, 3 sites in 554 bp for 16S, 9 sites in 727 bp for COX3, and 12 sites in 2577 bp for 18S). Another plausible explanation is that the O. muscosa specimen from New Zealand, from which the sequences used in our phylogeny were obtained, may have been misidentified. In any case, additional studies, including sequences from a broader set of O. muscosa specimens, are required to more accurately determine the phylogenetic position of this species and clarify its relationship with other species of Oulactis and Anthopleura.

Our results also indicate that the sea anemone we studied is not an exotic invasive sea anemone species from Australia, but rather a native species with a regional distribution spanning the coasts of Brazil and Argentina. Nonetheless, it is not uncommon to find invertebrate species from Australia or New Zealand along the coast of Mar del Plata. For example, a study by Farias et al. [45] used morphological and genetic analyses to confirm the presence of the sea slug Pleurobranchaea maculata (Quoy & Gaimard, 1832) [46], a species native to New Zealand, in Mar del Plata and other parts of the Argentine coast. With respect to exotic sea anemone species reported in Argentina, Orensanz et al. [13] initially reported three species: O. muscosa, Boloceroides mcmurrichi, and Aulactinia reynaudi, all of which had also been documented by Zamponi [5]. Subsequently, Excoffon et al. [47] reported for the first time in Argentina the presence of Haliplanella lineata (Verrill, 1869) [48] (= Diadumene lineata), found on the coasts of Las Grutas, in the Gulf of San Matias, Río Negro Province. Diadumene lineata is the most widely distributed sea anemone species globally, with records from both the Northern and Southern hemispheres [49]. This species was later also reported in Bahía Blanca [50,51] and more recently in Mar Chiquita [52], both in Buenos Aires Province. Among these four species, Acuña et al. [53] demonstrated, based on morphological and molecular data, that the specimens identified by Zamponi [5] as A. reynaudi actually belonged to the species Aulactinia marplatensis (Zamponi, 1977) [5], a species native to Argentina. Regarding the report of B. mcmurrichi from the Santa Elena coast near Mar del Plata, we have been unable to verify its validity, as we could not locate the reference material from Zamponi [5], nor have we found additional specimens or been able to conduct new collections in the area where it was originally recorded. Furthermore, there are inconsistencies between Zamponi’s [5] report and other descriptions of the species (e.g., Fautin et al. [16]). Therefore, we consider its presence and record in Argentina to be doubtful. Since the present study demonstrates that O. muscosa is not present in Argentina, of the four previously considered non-native species we can only confirm the presence of D. lineata, which is consistent with the updated list of invasive exotic anemones compiled by Schwindt et al. [54].

Additionally, we must include Metridium senile (Linnaeus, 1761) [55] in this list. This species is considered one of the most widely distributed invasive anemones worldwide [49,56], and its presence in Argentina has been known for approximately 50 years [57], although it has only recently begun to be recognized as an exotic invasive species [58,59]. Finally, at least four other sea anemone species reported in Argentina are not native to the country: Phlyctenanthus australis Carlgren, 1950 [60], reported by Zamponi [5] in Mar del Plata but native to Australia; Galatheanthemum profundale Carlgren, 1956 [61], and Limnactinia nuda Carlgren, 1927 [62], reported by Dunn [63] and Excoffon & Acuña [64], respectively, for the Argentine sub-Antarctic region but native to New Zealand; and Urticinopsis crassa Carlgren, 1938 [65], reported from the Argentine Sea by Excoffon & Acuña [64] and Zamponi et al. [66] but native to South Africa. For these latter four species, it would be important to confirm their taxonomic identification and actual presence in Argentina before including them in the invasive exotic species lists.

The previously known distribution range of Anthopleura correae, from Ceará in northeastern Brazil to Santa Catarina, is herein extended southward to the rocky intertidal shores of Mar del Plata, Argentina. This range expansion may be facilitated by the Brazil Current, which transports warm tropical waters southward along the continental shelf and can extend its influence beyond 38° S, encompassing the latitude of Mar del Plata [67]. Moreover, this species has been suggested to possess an oviparous, planktonic, and planktotrophic larval development [9], which would enhance larval survival time and potential for long-distance dispersal. Future efforts should also prioritize assessing the presence, distribution, and potential ecological impact of exotic species of sea anemones, particularly in vulnerable coastal ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17100736/s1, Supplementary Material S1: List of species and corresponding genetic sequence codes used in the phylogenetic analyses; Supplementary Material S2: Complete phylogenetic reconstruction based on maximum likelihood analysis of Anthopleura correae within the order Actiniaria using a concatenated dataset of conventional markers (12S, 16S, 18S, 28S, COX3).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-M., J.D.-F., A.G., C.S., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; methodology, R.G.-M., J.D.-F., A.G., C.S., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; software, R.G.-M. and J.D.-F.; validation, R.G.-M., J.D.-F., A.G., C.S., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; formal analysis, R.G.-M. and J.D.-F.; investigation, R.G.-M., J.D.-F., A.G., C.S., H.D., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; resources, R.G.-M., C.S., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; data curation, R.G.-M. and J.D.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.G.-M., J.D.-F., A.G., C.S., H.D., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; visualization, R.G.-M. and F.H.A.; supervision, R.G.-M., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; project administration, R.G.-M., S.N.S. and F.H.A.; funding acquisition, R.G.-M., S.N.S. and F.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (PICT 2020-Serie A-01451) to RGM, from PADI Foundation (Project No. 68424) to RGM, from the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET—PIP 0049) and from the National University of Mar del Plata (UNMdP—EXA 1150/24) to FHA, and from the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq -Research Productivity Scholarship) [grant number 304267/2022-8], CNPq—International Collaborations—[grant number 441932/2023-1], and from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) [grant number 2022/16193-1] to SNS.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Graciela Isabel Álvarez (IIMyC-CONICET) for her support with histological sections. The present study was supported by the institutional projects of MINCyT, Proyectos Pampa Azul (2021): Ecosistemas costeros de la Provincia de Buenos Aires: Funcionamiento y efectos antrópicos sobre la estructura, funciones y servicios ecosistémicos en un contexto de cambio climático (IF-2021-68146884).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Carlos Spano was employed by the company Ecotecnos S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Molnar, J.L.; Gamboa, R.L.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M.D. Assessing the global threat of invasive species to marine biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 6, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolus, A. Error cascades in the biological sciences: The unwanted consequences of using bad taxonomy in ecology. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2008, 37, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.D. On Zoophytes. Am. J. Sci. Arts Second. Ser. 1846, 2, 64–69, 2, 187–202; 3, 1–24; 3, 160–163; 3, 337–347. [Google Scholar]

- Fautin, D.G. Catalog to families, genera, and species of orders Actiniaria and Corallimorpharia (Cnidaria: Anthozoa). Zootaxa 2016, 4145, 1–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamponi, M.O. La anemonofauna de Mar del Plata y localidades vecinas. I. Las anémonas Boloceroidaria y Endomyaria (Coelentherata: Actiniaria). Neotropica 1977, 23, 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Carlgren, O. A Survey of the Ptychodactiaria, Corallimorpharia and Actiniaria; Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar: Stockholm, Sweden, 1949; Volume 1, pp. 1–121. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, G. The Actiniaria of New Zealand. A check-list of recorded and new species a review of the literature and a key to the commoner forms Part I. Rec. Canterb. Mus. 1951, 6, 83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cutress, C.E. Corallimorpharia, Actiniaria and Zoanthidea. Mem. Natl. Mus. Vic. Melb. 1971, 32, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffon, A.C.; Zamponi, M.O. Reproducción de Oulactis muscosa Dana, 1849 (Cnidaria; Actiniaria) en el intermareal de Mar del Plata, Argentina. Biociencias 1996, 4, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña, F.H.; Zamponi, M.O. Estructura poblacional y ecología trófica de Oulactis muscosa Dana, 1849 (Actiniaria, Actiniidae) del litoral bonaerense (Argentina). Physis 1999, 57, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña, F.H.; Excoffon, A.C.; Ricci, L. Composition, biometry and statistical relationships between the cnidom and body size in the sea anemone Oulactis muscosa (Cnidaria: Actiniaria). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 2007, 87, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, F.H.; Ricci, L.; Excoffon, A.C. Statistical relationships of cnidocysts sizes in the sea anemone Oulactis mucosa (Actiniaria: Actiniidae). Belg. J. Zool. 2011, 141, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orensanz, J.M.; Schwindt, E.; Pastorino, G.; Bortolus, A.; Casas, G.; Darrigran, G.; Elías, R.; López-Gappa, J.J.; Obenat, S.; Penchaszadeh, P.; et al. No longer the pristine confines of the world ocean: A survey of exotic marine species in the southwestern Atlantic. Biol. Invasions 2002, 4, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne-Edwards, H. Histoire Naturelle des Coralliaires, ou Polypes Proprement Dits. 1; Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret: Paris, France, 1857; 326p. [Google Scholar]

- Kwietniewski, C.R. Actiniaria von Ambon und Thursday Island. Zoologische Forschungsreisen in Australien und dem Malayischen Archipel von Richard Semon; Gustav Fisher: Jena, Germany, 1898; pp. 385–430. [Google Scholar]

- Fautin, D.G.; Crowther, A.L.; Wallace, C.C. Sea anemones (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria) of Moreton Bay. Mem. Qld. Mus. Nat. 2008, 54, 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. Actiniaria (Cnidaria Anthozoa) of Port Phillip Bay, Victoria: Including a Taxonomic Case Study of Oulactis muscosa and Oulactis mcmurrichi. Ph.D. Thesis, Southern Cross University, Lismore, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Häussermann, V. Redescription of Oulactis concinnata (Drayton in Dana, 1846) (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniidae), an actiniid sea anemone from Chile and Perú with special fighting tentacles; with a preliminary revision of the genera with a “frond-like” marginal ruff. Zool. Verh. 2003, 345, 173–207. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, P.G.; Daly, M. Phylogenetic analysis reveals an evolutionary transition from internal to external brooding in Epiactis Verrill (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria) and rejects the validity of the genus Cnidopus Carlgren. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2016, 94, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann-Zürneck, K.; Gallardo, V.A. A new species of sea anemone (Saccactis coliumensis n. sp.) living under hypoxic conditions on the central Chilean shelf. Helgol. Meeresunters 1990, 44, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchassaing, P.; Michelotti, J. Mémoire sur les coralliaires des Antilles. In Mémoires de l’Academie des Sciences de Turin Séries 2; Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino: Turin, Italy, 1860; Volume 19, pp. 279–365. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/10226124 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Durán-Fuentes, J.A.; González-Muñoz, R.; Vassallo-Ávalos, A.; Delgado, A.; Daly, M.; Stampar, S. Revisiting Anthopleura cascaia (nomen nudum): Description of Anthopleura correae sp. nov. and the taxonomic challenges of a variable lineage (Anthozoa, Actiniaria). Mar. Biodivers. in press.

- Östman, C. A guideline to nematocyst nomenclature and classification, and some notes on the systematic value of nematocysts. Sci. Mar. 2000, 64, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Barbeitos, M.S.; Brugler, M.R.; Crowley, L.M.; Grajales, A.; Gusmão, L.; Häussermann, V.; Reft, A.; Daly, M. Hidden among sea anemones: The first comprehensive phylogenetic reconstruction of the order Actiniaria (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Hexacorallia) reveals a novel group of hexacorals. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garese, A.; González-Muñoz, R.; Nesca, S.; Vasquez-Sasali, C.; Deserti, M.I.; Erralde, S.; Suárez, P.A.; Acuña, F.H. Colección de Antozoos del Atlántico Sur. Version 1.1. Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras, CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata/Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales. Metadata Dataset. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/dataset/679af940-5395-4323-8d23-2b1e6aa7ef8e (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Brugler, M.R.; González-Muñoz, R.; Tessler, M.; Rodríguez, E. An EPIC journey to locate single-copy nuclear markers in sea anemones. Zool. Scr. 2018, 47, 756–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Cavanaugh, M.; Clark, K.; Pruitt, K.D.; Sherry, S.T.; Yankie, L.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I. GenBank 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Asimenos, G.; Toh, H. Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 537, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, G.; Lohman, D.J.; Meier, R. SequenceMatrix: Concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 2011, 27, 17–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, M.; Gascuel, O. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: A fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst. Biol. 2006, 55, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, M.; Gil, M.; Dufayard, J.F.; Dessimoz, C.; Gascuel, O. Survey of branch support methods demonstrates accuracy, power, and robustness of fast likelihood-based approximation schemes. Syst. Biol. 2011, 60, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöver, B.C.; Müller, K.F. TreeGraph 2: Combining and visualizing evidence from different phylogenetic analyses. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA 11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Den Hartog, J.C. Anthopleura (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria) from the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2004, 74, 401–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig, R. Report on the Actiniaria dredged by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–1876. In Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of the H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873-76 (Zoology); Her Majesty’s Stationery Office: London, UK, 1882; Volume 6, pp. 1–136. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/6512483 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Rafinesque, C.S. Analyse de la Nature ou Tableau de l’Univers et des Corps Organisés; Rafinesque, C.S., Ed.; Gallia: Palerme, Italy, 1815; 224p. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, M.; Crowley, L.M.; Larson, P.; Rodríguez, E.; Heestand Saucier, E.; Fautin, D.G. Anthopleura and the phylogeny of Actinioidea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria). Org. Divers. Evol. 2017, 17, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, N.E.; Wood, S.A.; Obenat, S.; Schwindt, E. Genetic barcoding confirms the presence of the neurotoxic sea slug Pleurobranchaea maculata in southwestern Atlantic coast. N. Z. J. Zool. 2016, 43, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoy, J.R.C.; Gaimard, P. Voyage de Decouvertes de l’Astrolabe Exécutée par Order du roi Pendant les Années 1826-1827-1828-1829, Sous le Commandement de MJ Dumont d’Urville: Zoologie; Editeur-Imprimeur: Paris, France, 1832. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffon, A.C.; Acuña, F.H.; Zamponi, M.O. Presence of Haliplanella lineata (Verrill, 1869) (Actiniaria, Haliplanellidae) in the Argentine Sea and the finding of anisorhize haploneme cnidocyst. Physis 2004, 60, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Verrill, A.E. Synopsis of the Polyps and corals of the North Pacific Exploring Expedition. Commun. Essex Inst. 1869, 6, 51–104. [Google Scholar]

- Glon, H.; Daly, M.; Carlton, J.T.; Flenniken, M.M.; Currimjee, Z. Mediators of invasions in the sea: Life history strategies and dispersal vectors facilitating global sea anemone introductions. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 3195–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, L.M.; Valinas, M.S.; Pratolongo, P.D.; Elias, R.; Perillo, G.M. First record of the sea anemone Diadumene lineata (Verrill, 1871) associated to Spartina alterniflora roots and stems, in marshes at the Bahia Blanca estuary, Argentina. Biol. Invasions 2009, 11, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, A.P.; Osinaga, M.-I.; Menechella, A.G.; Carcedo, M.-C.; Amodeo, M.R.; Fiori, S.M. Exploring substrate associations of the non-native anemone Diadumene lineata on an open ocean coast in the SW Atlantic. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 2369–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Muñoz, R.; Lauretta, D.; Bazterrica, M.C.; Tapia, F.A.P.; Garese, A.; Bigatti, G.; Penchaszadeh, P.E.; Lomovasky, B.; Acuña, F.H. Mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequencing confirms the presence of the invasive sea anemone Diadumene lineata (Verrill, 1869)(Cnidaria: Actiniaria) in Argentina. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, F.H.; Excoffon, A.C.; McKinstry, S.R.; Martínez, D.E. Characterization of Aulactinia (Actiniaria: Actiniidae) species from Mar del Plata (Argentina) using morphological and molecular data. Hydrobiologia 2007, 592, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwindt, E.; Carlton, J.T.; Orensanz, J.M.; Scarabino, F.; Bortolus, A. Past and future of the marine bioinvasions along the Southwestern Atlantic. Aquat. Invasions 2020, 15, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae: Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Ed. 12. 1., Regnum Animale. 1 & 2; Holmiae, Laurentii Salvii: Stockholm, Sweden, 1767; pp. 1–532, 533–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Häussermann, V.; Molinet, C.; Díaz Gómez, M.; Försterra, G.; Henríquez, J.; Espinoza-Cea, K.; Matamala-Ascencio, T.; Hüne, M.; Cárdenas, C.A.; Glon, H.; et al. Recent massive invasions of the circumboreal sea anemone Metridium senile in North and South Patagonia. Biol. Invasions 2022, 24, 3665–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann-Zürneck, K. Actiniaria des Südwestatlantik. Helgol. Mar. Res. 1975, 27, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.P.; Garese, A.; Sar, A.M.; Acuña, F.H. Fouling community dominated by Metridium senile (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Actiniaria) in Bahía San Julián (Southern Patagonia, Argentina). Sci. Mar. 2015, 79, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, L.H.; Battini, N.; González-Muñoz, R.; Glon, H. Invader in disguise for decades: The plumose sea anemone Metridium senile in the Southwestern Atlantic Ocean. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 2159–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlgren, O. Corallimorpharia, Actiniaria and Zoantharia from New South Wales and South Queensland. Ark. Zool. 1950, 1, 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Carlgren, O. Actiniaria from depths exceeding 6000 meters. Galathea Rep. 1956, 2, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carlgren, O. Actiniaria and Zoantharia. In Further Zoological Results of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition; P.A. Norstedt & Söner: Stockholm, Sweden, 1927; Volume 2, pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, D.F. Some Antarctic and sub-Antarctic sea anemones (Coelenterata: Ptychodactiaria and Actiniaria). Antarct. Res. Ser. 1983, 39, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffon, A.C.; Acuña, F.H. Nuevas citas para los Hexacorallia (Cnidaria: Anthozoa) de la región Subantártica. Neotropica 1995, 41, 105–106, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Carlgren, O. South African Actiniaria and Zoantharia. K. Sven. Vetenskapsakademiens Handl. 1938, 17, 1–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi, M.O.; Genzano, G.N.; Acuña, F.H.; Excoffon, A.C. Studies of benthic cnidarian populations along a transect off Mar del Plata. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 1998, 24, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Matano, R.P.; Schlax, M.G.; Chelton, D.B. Seasonal variability in the Southwestern Atlantic. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 18, 18027–18035. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).