Abstract

Leptochela Stimpson (1860) is a shallow-water, benthopelagic genus within the predominantly pelagic superfamily Pasiphaeoidea. We inventoried a global fauna of 17 currently valid species of Leptochela and identified a newly discovered eighteenth species. Our analysis combined both morphological and molecular data, using 13 characters (including two multistate characters) and 5 gene markers, respectively. The results revealed incongruence between the molecular and morphological datasets. However, our phylogenetic conclusions were based on a consensus approach, integrating morphological, molecular, and total evidence trees, which revealed three robust clades. We discuss the evolutionary development of quantitative and qualitative morphological traits in Leptochela and explore the potential causes of the incongruence between morphological and molecular signals, particularly in the context of pelagic eucarids transitioning from pelagic to benthopelagic habitats. Additionally, we describe the new species from Madagascar and provide a key to all known species of Leptochela.

1. Introduction

The genus Leptochela Stimpson 1860 belongs to the superfamily Pasiphaeoidea, which includes both pelagic and benthopelagic shrimps (associated with the seafloor, as described by Vereshchaka [1]). Unlike most members of the superfamily, all species of Leptochela are relatively small, with adult carapace lengths generally less than 1 cm. These shrimps typically inhabit coastal waters, where they exhibit diurnal migrations, rising to the sea’s surface at night. They can be abundant in certain regions [2]. Currently, Leptochela comprises 17 recognized shallow-water species distributed throughout many parts of the world’s oceans, excluding the polar and temperate regions (Figure 1, Leptochela Stimpson, 1860 [3]).

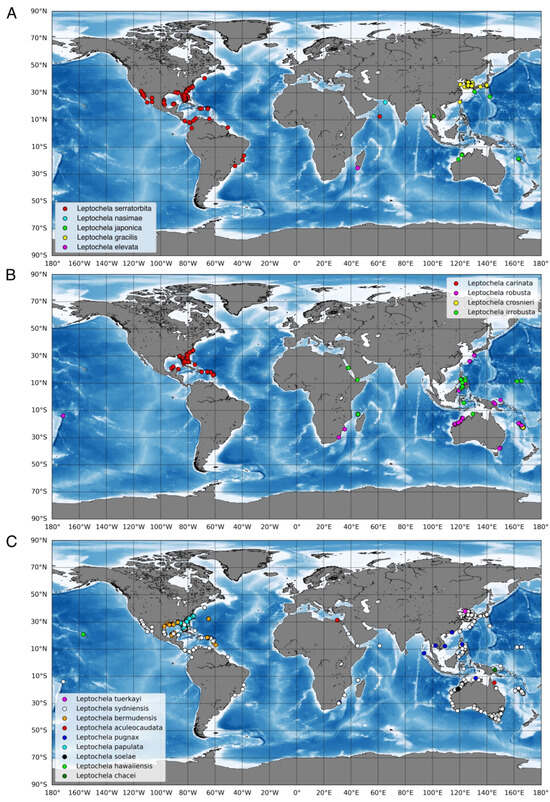

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of species of Leptochela according to https://www.gbif.org/ru/species/2222285 (accessed 2 November 2024) and the locality of the new species. (A) geographical distribution of species of the Clade 1 and the “Clade 3”; (B) geographical distribution of species of the Clade 2; (C) geographical distribution of the rest species of Leptochela. Explanation of the clades content see in the Section 4.

The first two species of the genus, L. gracilis and L. robusta, were described from the Pacific Ocean in 1860 by Stimpson [3]. Over the subsequent century, seven additional species were documented from various regions, mostly in the Indo-West Pacific [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. In 1976, Chace [2] presented the most comprehensive morphological study of the 12 species known at that time, including three newly described species (L. hawaiiensis, L. irrobusta, and L. papulata), and proposed the subgenera Leptochela and Probolura. However, the latter subgenus is not currently recognized by the World Register of Marine Species [12]. Since Chace’s revision, five additional species have been described, expanding the known range of the genus [13,14,15,16].

Leptochela species differed significantly from other genera in the family Pasiphaeidae to the extent that they were at times classified into their own family, Leptocheliidae [6]. However, this distinction was debated due to the similar morphology of their mouthparts and pereopods with typical pasiphaeids. A broad phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial 16S and nuclear 18S rDNA by Bracken et al. [17] showed that the Pasiphaeidae family is polyphyletic, which supported the separation of Leptochela from Pasiphaeidae. However, subsequent molecular analyses using six gene markers confirmed that Leptochela clusters with other pasiphaeid genera, although the genetic divergence between the clades is significant, comparable to that between different caridean families [18]. The molecular evidence revealed three distinct clades within Leptochela: (1) L. serratorbita Spence Bate 1888), (2) L. robusta Stimpson 1860 + L. crosnieri Hayashi 1995, and (3) L. japonica Hayashi and Miyake 1969 + L. gracilis Stimpson 1860 + L. soelae Hanamura 1987.

Both major revisions of the genus were incomplete in their approaches: Chace [2] did not employ molecular or cladistic methods, while Liao et al. [18] relied solely on molecular data without considering morphological evidence. In this study, we integrate both morphological and molecular data to provide a phylogenetic revision of Leptochela. This revision is timely, as five new species have already been described by Chace [2], and the description of a sixth new species is presented here.

In contrast to other pelagic eucarid taxa, which have shown high congruence between molecular and morphological phylogenies [19,20,21,22,23,24], the Pasiphaeoidea exhibit discrepancies between these two approaches. For instance, species groups proposed by Hayashi [24,25,26,27,28] do not align with molecular clades identified by Liao et al. [18]. We anticipate similar issues with Leptochela and apply three distinct approaches, morphological, molecular, and total-evidence-based analysis, to reconcile these differences. Furthermore, we analyze the evolutionary development of quantitative and qualitative morphological traits, focusing on the genus’s unique coastal lifestyle. One particularly noteworthy structure is the chela, which is variable across species and underexplored in Leptochela. We expect to uncover significant evolutionary traits in this feature and other morphological characteristics.

2. Methods

2.1. Morphological Data and Analysis

We analyzed all 17 currently accepted (https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=107050, accessed on 1 June 2024.) species of the genus, including one undescribed new species. Samples from twelve of them were morphologically checked (Table 1), and the remaining five were analyzed using their descriptions. For morphological phylogenetic analyses, we chose two outgroups from Pasiphaeoidea, both representing the sister group clade to Leptochela ([18], Figure 1): Pasiphaea sivado (Risso, 1816), the type species of Pasiphaea Savigny (1816), and Psathyrocaris fragilis Wood-Mason in Wood-Mason and Alcock (1893), the type species of Psathyrocaris Wood-Mason in Wood-Mason and Alcock (1893). The character coding (Supplementary Information, Table S1) and dataset (Supplementary Information, Table S2) were handled and analyzed using Winclada/Nona and TNT [29,30,31]. Trees were generated in TNT with 30 000 trees in memory under the ‘implicit enumeration” algorithms. The relative stability of clades was assessed by standard bootstrapping (sample with replacement) with 10,000 pseudoreplicates and by Bremer support (algorithm TBR, saving up to 10,000 trees up to 15 steps longer). In all analyses, clades were considered robust if they had Bremer support ≥3 and bootstrap support ≥70.

Table 1.

List of materials.

2.2. Molecular Data and Analysis

We used five gene markers in order to assess the phylogenetic position of the new Leptochela species: three mitochondrial (cytochrome c oxidase subunit I COI, 12S rDNA, and 16S rDNA) and two nuclear (histone 3 H3 and enolase). These gene markers, with the exception of COI, have previously been used to infer phylogenetic relationships among the other six Leptochela species [18].

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the muscle tissue of pleopods III–V using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Target regions of the selected gene markers were amplified using the following published primers: COI (COI-Hym-F2/COH6, [21,32]), 16S (16L2/16H3 [33,34,35]), and enolase (EA2/ES2 [36]).For amplification of 12S, we designed new primers (12S-psF1/R1) based on sequences published in GenBank (Supplementary Information, Table S3). A pre-made PCR mix (ScreenMix-HS) from Evrogen (Moscow, Russia) (1 × ScreenMix-HS, 0.4 μM of each primer, 1 μL of DNA template, and sufficient milliQ H2O to make up a total volume of 20 μL) was used for the amplification. The thermal profile used an initial denaturation for 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 35–40 cycles of 20 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 47–56 °C depending on different primer pairs (Supplementary Information, Table S3), and 1 min at 72 °C, with a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified by ethanol precipitation and sequenced in both directions using BigDye Terminator v.3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) on the ABI Prism-3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) by standard sequencing protocol at the joint center ‘Methods of molecular diagnostics’ of the Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The nucleotide sequences were verified and assembled using CodonCode Aligner v.7.1.1. All new sequences were then compared with genes reported in GenBank using BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information, NCBI) to check for potential contamination and submitted to the NCBI GenBank database (accession numbers: PQ576544, PQ587577, PQ587578, PQ594820, PQ594821).

For phylogenetic analyses, all Leptochela species represented in GenBank that had sequences for at least three of the five target genes were added to the dataset, along with representatives of all other genera in the family Pasiphaeidae, using Acantephyra armata A. Milne-Edwards 1881 as an outgroup (Supplementary Information, Table S4).

For each gene fragment, the sequences were aligned using MUSCLE [37] implemented in MEGA X [38], and the accuracy of alignment was adjusted visually. Alignments of protein-coding genes were also confirmed by translating them into amino acid sequences using TranslatorX [39] to ensure the absence of stop codons. The concatenated dataset was first partitioned by genes, with three protein-coding genes further divided into three codon positions (a total of 11 partitions). The partitioning scheme and best-fitting substitution models for each partition were determined using PartitionFinder2 [40], according to the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc). The final dataset was divided into 10 partitions with corresponding best-fit models of nucleotide substitutions (Supplementary Information, Table S5). The datasets were analyzed under maximum likelihood (ML) [41], as implemented in the raxmlGUI v2.0 program [42,43], and Bayesian inference (BI), as implemented in MrBayes 3.2 [44]. In the BI analysis, two independent runs, each consisting of 4 chains, were executed for 6,000,000 generations, with model parameters estimated during the analysis. Chains were sampled every 1000 generations, and the first 25% of trees were discarded as “burn-in”. A 1% average standard deviation of split frequencies was reached after 400,000 generations, and a 75% majority rule consensus tree was constructed from the remaining trees to evaluate clade confidence from posterior probabilities estimation. In the ML analysis, we used the GTR+G model for each individual dataset and each partition in the concatenated dataset, with all free parameters estimated by raxmlGUI v2.0 with 10 independent runs. Confidence values of branches in the resulting trees were evaluated by a thorough bootstrap procedure with 1000 replicates. We considered the clades to be statistically supported if they had the support of posterior probabilities ≥0.9 in the BI analysis and a bootstrap value of ≥70% in the ML analysis.

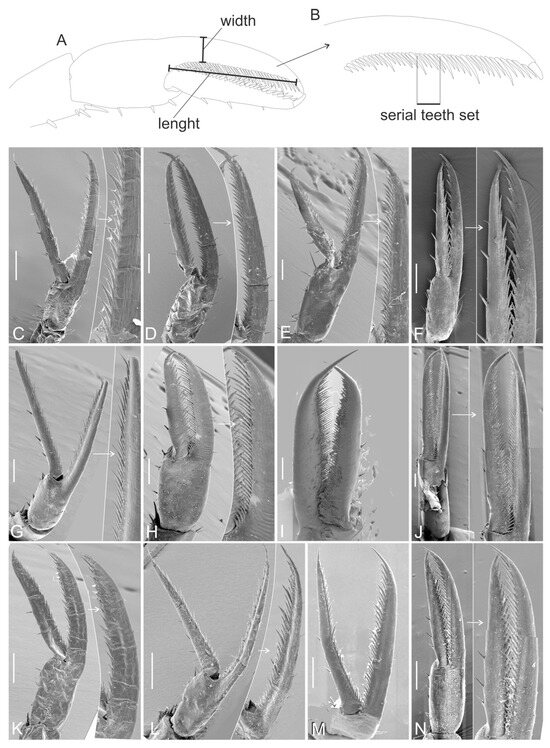

2.3. Statistical Analysis

In addition to ordinary morphological phylogenetic analysis, we tested the hypothesis that quantitative charactersistics carry phylogenetic signals. We observed the following: (1) the specimens were robust enough to be preserved in good condition (as Leptochela specimens are often damaged in collections), (2) they allowed confident measurements regardless of the viewing angle used, (3) they could be documented with high-quality SEM images or illustrations, and (4) they demonstrated notable variability regarding chelae. From these criteria, we selected four parameters from our SEM results (12 species) and from figures in the original descriptions (6 species) (Table 1, Figure 2):

- -

- Finger length-to-width ratio;

- -

- The angle of the teeth on the cutting edge respective to the cutting edge margin;

- -

- The minimum number of smaller serial teeth set between larger teeth on the cutting edge;

- -

- The maximum number of smaller serial teeth set between larger teeth on the cutting edge.

Figure 2.

Chelae of Leptochela species. (A) Scheme of chela width and length measuring; (B) teeth series scheme; (C) L. aculeocaudata; (D) L. bermudensis; (E) L. carinata; (F) L. chacei; (G) L. crosnieri; (H) L. elevata; (I) L. gracilis; (J) L. japonica; (K) L. papulata; (L) L. pugnax; (M) L. robusta; (N) L. serratorbita. White arrows marked enlarged part of the photographes. Scale bar 0.2 mm.

Since the first and the second pereopods were similar and the former was broken more often than the latter, we measured the second pereopod. We did not include L. soelae and L. tuerkayi in the analysis because we did not have these species at hand, and the figures of chela in the original descriptions were unsatisfactory.

We ran a principal component analysis (PCA, [45,46]) using the measured parameters that were normalized in order to avoid a bias linked to different measurement units. The PCA was expected to assess the driving power of the quantitative characteristics mentioned above on the morphological diversification of Leptochela.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the New Species

- Subphylum Crustacea Brünnich, 1772

- Order Decapoda Latreille, 1802

- Superfamily Pasiphaeoidea Dana, 1852

- Genus Leptochela Stimpson, 1860

- Leptochela Stimpson, 1860: 42 [4]; Chace, 1976: 2 [2]; Wang et al., 2017: 1269 [16]

Diagnosis—Carapace and rostrum unarmed dorsally; rostrum small, not overreaching end of antennular peduncle; branchiostegal tooth and branchiostegal sinus absent. Sixth abdominal somite with 1–2 posteriorly directed teeth near posterior end of ventrolateral margin. Telson with two or three pairs of dorsolateral spines, one anterior pair located medially, posterior margin with 4–5 pairs of spiniform setae. Mandibular palp broad, flattened, one-segmented. All pereopods with exopods; fourth pereopods shorter than third, longer than fifth ones. Exopods of pleopods not greatly elongate. Both branches of uropod with series of movable lateral spines.

- Leptochela elevata sp. n.

- ZooBank: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:BE022462-C53B-4B88-B53E-E813420D3180

Material: Holotype, female, CL = 4 mm, SUD MADAGASCAR, secteur de Lavanono, 19–20 m, 25°25′22.3824″ S; 44° 54′30.2436″ E; 26.05.2010, ATIMO VATAE, St. BP06; National Museum of Natural History (MNHN-IU-2010-4966).

Diagnosis—Rostrum with dorsal margin slightly concave. Orbital margin smooth, without medially directed tooth on ventral part; suborbital angle unarmed. Fifth abdominal somite with dorsal carina with 3 elevations, third one very prominent and forming blunt lappet directed posteriorly; sixth abdominal somite without dorsal lappet. Telson with a pair of dorsolateral spines in addition to an anterior mesial pair; posterior margin with 5 pairs of spines.

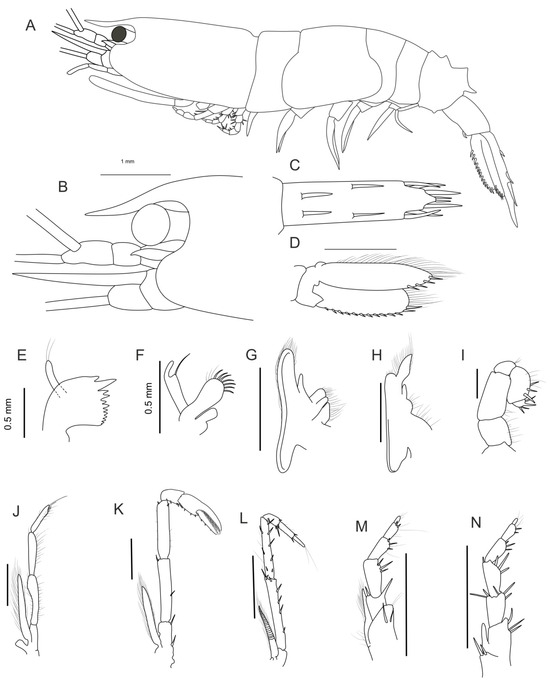

Description: The rostrum (Figure 3A,B) overreaches the second segment of the antennular peduncle. The dorsal surface of the carapace is without a median carina. The orbital margin (Figure 3A,B) is whole, and the suborbital angle is rounded.

The pleon (Figure 3A) is regularly rounded dorsally on the first to fourth somites. The posteriormost tooth of the fifth somite forms elevations directed posteriorly. The sixth somite is nearly 1.8 times as long as it is high, broadening distally in the dorsal view, armed with a short spine on the ventrolateral margin.

Figure 3.

Morphology of the new species Leptochela elevata sp. n. Holotype, female, (MNHN-IU-2010-4966). (A) Body, lateral view; (B) anterior part of carapace, lateral view; (C) telson, dorsal view; (D) left uropods; (E) mandibula; (F) maxilla I; (G) maxilla II; (H) maxilliped I; (I) maxilliped II; (J) maxilliped III; (K) pereopod II; (L) pereopod III; (M) pereopod IV; (N) pereopod V; (D–N) outer view. Scale bar 1 mm.

The telson (Figure 3C), excluding posterior spines, is nearly 1.7 times as long as the sixth somite and 3.7 times as long as it is wide; the posterior margin is without a pair of minute spines between bases of the mesial pair of prominent terminal spines.

The eye cornea is wider than the eyestalk (Figure 3B). The antennular peduncle (Figure 3A,B) has a second segment distinctly shorter than the distal segment in lateral view. The antennal scale (Figure 3B) is 0.5 times as long as the carapace, with both lateral and mesial margins nearly straight. The distal segment of the antennal peduncle reaches about 0.3 of the scale.

Mouthparts are as illustrated in Figure 3E–J.

The first pereopod is missing. The second pereopod (Figure 3K) has an exopod reaching nearly the middle of the ischium, with the carpus bearing two spinules on opposable sides of the distal end, the merus bearing two movable spines in the distal and median parts, an ischium armed with two movable spines, and a chela with 26 to 39 spines on opposable margins (Figure 2A). The third pereopod (Figure 3L) has an exopod reaching nearly the middle of the ischium; the ischium is armed with a row of four spines near the extensor margin and three at the distal end; the merus has three spines on the extensor margin and five spines on flexor margin; the carpus shorter than the propodus, and both are unarmed. The fourth pereopod (Figure 3M) has an exopod reaching the end of the ischium; the ischium is armed with several stout spines and one strong tooth in a distal part; similar stout spines can be seen on the flexor margin of the merus, carpus, and propodus; the dactyl is shorter than the propodus. The fifth pereopod (Figure 3N) has an exopod reaching the end of the basis; the ischium is armed distally with several stout spines; similar stout spines can be seen on the flexor margin of the merus carpus and propodus; the dactyl is very small, considerably shorter than propodus.

The exopod of the uropod is armed with 13 movable spines along the outer margin, and the endopod of the uropod bears four movable spines on the distal part of the outer margin (Figure 3D).

Remarks: Leptochela elevata sp. n. differs from all species of Leptochela in having a blunt posteriorly directed lappet only on the fifth segment. At first sight (not supported by molecular data), the new species is morphologically similar to L. carinata, L. soelae, L. japonica, and L. papulata in having dorsal elevations on the fifth pleonic somite. These elevations are large in L. elevata sp. n., L. carinata, and L. soelae, distinguishing these three species from L. japonica and L. papulata. Leptochela elevata sp. n. further differs from L. carinata and L. soelae by lacking a dorsal lappet on the sixth pleonic somite.

Etymology: The species name refers to the prominent dorsal elevations on the fifth pleonic somite.

Geographical and vertical distribution: The species is only currently known to be from South Madagascar, at a depth of ~20 m.

3.2. Molecular and Total-Evidence Phylogenetic Analyses

The concatenated five-gene dataset consisted of 2162 bp and included six species of Leptochela.

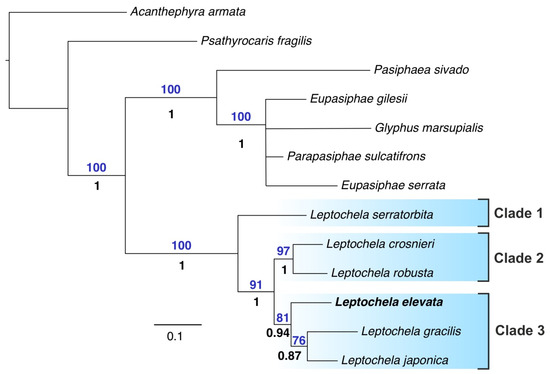

Phylogenetic trees retrieved by BI and ML analyses were similar to each other and resolved (Figure 4). Leptochela was observed to be a well-supported monophyletic genus encompassing three major clades:

- (1)

- L. serratorbita;

- (2)

- L. crosnieri + L. robusta;

- (3)

- L. elevata + L. gracilis + L. japonica.

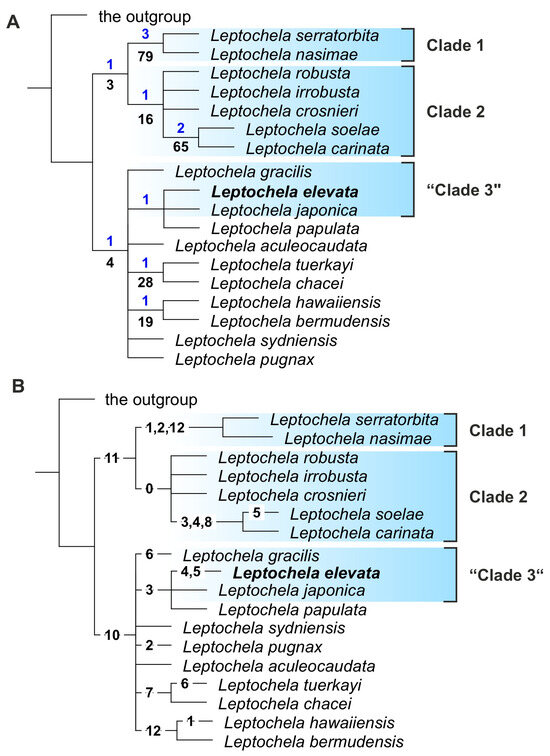

Figure 4.

Five-gene phylogenetic tree (BI and ML analyses) including six species of Leptochela. Only supported clades are shown. Statistical support is indicated as ML bootstrap support (analysis with 1000 replicates (above branches) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (below branches). The new species is in bold.

3.3. Morphological Phylogenetic Analysis

Analyses with Pasiphaea sivado and Psathyrocaris fragilis as outgroups retrieved most parsimonious (MP) trees, each with a score of 23, respectively (in both cases, Ci = 69 and Ri = 80). The trees were very different from those retrieved via molecular analyses and showed two major clades that were not robust (Figure 5A):

- (1)

- L. carinata + L. crosnieri + L. irrobusta + L. nasimae + L. robusta + L. serratorbita + L. soelae;

- (2)

- L. aculeocaudata + L. bermudensis + L. chacei + L. elevata + L. gracilis + L. hawaiiensis + L. japonica + L. papulata + L. pugnax + L. sydniensis + L. tuerkayi.

The only robust clade that gained both Bremer and bootstrap support was L. nasimae + L. serratorbita.

Supporting synapomorphies are listed in Figure 5B.

Figure 5.

Morphological phylogenetic trees of genus Leptochela. (A) A tree with statistical supports: Bremer and bootstrap support above and below branches, respectively; (B) a tree with synapomorphies (see coding in Supplementary Information, Table S1). The new species is in bold.

3.4. Total Evidence Phylogenetic Analysis

The total evidence tree (Figure 6) showed two major robust clades:

- -

- L. nasimae + L. serratorbita;

- -

- L. carinata + L. crosnier i + L. irrobusta + L. robusta + L. soelae, including the crown clade L. carinata + L. soelae.

Overall, the total evidence tree mirrored the great incongruence of molecular and morphological trees caused by contradicting molecular and morphological phylogenetic signals. Since the molecular trees were well-resolved, we based further analyses mostly on these results.

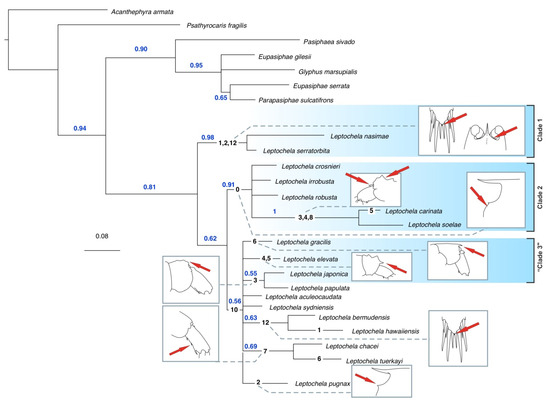

Figure 6.

Total evidence tree of genus Leptochela with synapomorphies (black numbers on the branches, see coding in Supplementary Information, Table S2) and their partial visualization. Red arrows mark location of sinapomorphies, blue numbers mark statistical supports.

3.5. Morphology of the Chela and Molecular Clades

Two of the analyzed characters, i.e., maximal and minimal numbers of smaller serial teeth in chelae, were greatly collinear, and we combined them and used a single parameter estimated as a simple arithmetic average of both parameters: the maximal and minimal number of smaller serial teeth set between larger teeth on the cutting edge.

PCA explained 94% of the variance (Figure 7) and showed that the first principal component explained 67% of the variance and was mainly linked to the teeth angle on the cutting edge and, to a lesser extent, to the palm length-to-width ratio. The second principal component explained 27% of the variance and was more linked to the average number of smaller serial teeth.

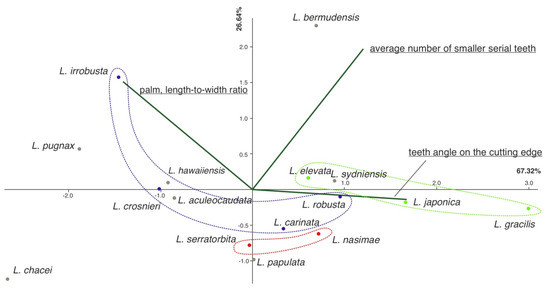

Figure 7.

Principal component analysis (PCA) results. Clades are marked with colors: Clade 1, red color; Clade 2, blue color; Clade 3, green color; other species, gray dots.

Overall, PCA analyses showed that molecular clades, as retrieved via molecular analyses, varied in the number of smaller serial teeth, whereas species within the clades mostly differed in the teeth angle and the palm length-to-width ratio. Classical statistical tests for difference were not appropriate due to the restricted number of measured specimens.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Incongruence of Morphological and Molecular Phylogenetic Signals: Compromising the Phylogeny, Evolutionary Trends, and Possible Origin of the Incongruence

Our findings align with previous studies [47,48], highlighting conflicting phylogenetic signals between morphological and molecular data. This incongruence reflects a gap in our understanding of the evolutionary processes driving these datasets [49]. Molecular evolution is relatively well-understood, informed by the biochemical properties of molecules and empirical sequence data. In contrast, the mechanisms of morphological evolution are less defined, and phylogenetic methods based on morphology often rely on simpler assumptions [50,51].

A key challenge is that morphological characteristics, unlike molecular sites, are not equivalent; the states across characters are not easily comparable and may not share consistent properties [52]. Traditionally, morphology has been analyzed using maximum parsimony, an optimization method that adheres to Ockham’s Razor, minimizing the number of character–state transitions needed to explain evolutionary relationships [50]. As a result, morphological-based phylogenetic methods tend to be simpler and make broad assumptions about data properties [50,51].

When morphological and molecular data are combined, the resulting phylogenies often differ from those derived from either dataset alone. Morphological–molecular incongruence is widespread, and different data partitions can yield distinct trees regardless of the inference method used [49]. Despite these challenges, combining both data types is essential for reconstructing the most accurate evolutionary history [49].

In our study, we identified a consensus among molecular (Figure 4), morphological (Figure 5), and total evidence (Figure 6) approaches, revealing the following robust clades:

- -

- Clade 1: L. nasimae + L. serratorbita (supported by the morphological and total evidence trees).

- -

- Clade 2: L. carinata + L. crosnieri + L. irrobusta + L. robusta (supported by the total evidence tree, with L. robusta and L. crosnieri also forming a robust clade in the molecular tree).

- -

- Clade 3: L. gracilis + L. elevate + L. japonica (strongly supported in the molecular tree, with no contradiction from the total evidence tree).

The position of L. soelae was questionable; therefore, we did not include this species in any of the clades. It was nested in Clade 2 in our analyses but grouped with the species of Clade 3 in [18]. The phylogenetic positions of other Leptochela species remain unresolved, as they did not form robust clades in the morphological and total evidence trees, whereas molecular data were unavailable.

The traits supporting these clades are primarily morphological. Clade 1 is characterized by a serrate orbital margin, an acute suborbital angle, and additional lateral spines on the telson. Clade 2 is defined by the presence of an acute tooth on the orbital margin, while Clade 3 features a single pair of dorsolateral spines and dorsal elevations on the fifth pleonic somite (seen in L. elevate and L. japonica).

Figure 6 shows the distribution of visualized synapomorphies across the total evidence tree. Many of these traits seem to be adaptations for anchoring to the substrate. For instance, the serrate orbital margin, acute suborbital angle, and additional lateral spines on the telson (Clade 1), as well as the acute tooth on the orbital margin (Clade 2), likely serve this function. Similarly, the dorsolateral spines and dorsal elevations on the fifth pleonic somite in Clade 3 (L. elevate and L. japonica) may have a similar role. Other synapomorphies, such as various lappets, dorsal elevations, ventral teeth on posterior pleonic somites, and additional robust spines on the telson, are irregularly distributed across species but may also play a role in anchoring.

In addition to these structural traits, the chela exhibits evolutionary trends that can be traced using quantitative parameters. We observed an increase in the number of serial small teeth in the chela across the clades (Clade 1 → Clade 2 → Clade 3), along with further diversification in the angle of the teeth on the cutting edge and the palm length-to-width ratio. This likely reflects an adaptation to a more specialized feeding strategy, with the smaller teeth allowing for finer manipulation of prey. However, a fuller understanding of these adaptations will only be possible with further study of the feeding behavior of Leptochela, which remains largely unknown.

The geographic distribution shows allopatric speciation within the retrieved clades. Clade 1 (Figure 1A): L. serratorbita occurs along the tropical shores of both Americas (a single record from the Indian Ocean is highly likely erroneous), whereas L. nasimae inhabits the Arabian Sea (Indian Ocean). Clade 2 (Figure 1B): L. carinata occurs in the tropical West Atlantic, and the rest of the species have been recorded in different areas of the Indo-West Pacific. Clade 3 (Figure 1A): L. elevata is known to be from the West Indian Ocean, L. gracilis occurs in the Northwest Pacific, and L. japonica is found in lower latitudes of the Indo-West Pacific.

Incongruence between morphological and molecular phylogenies is unusual for pelagic eucarids. Previous studies on other groups, such as Oplophoroidea [19,20,21,22,24] and Euphausiacea [23], have shown significant congruence between the two types of trees. We suggest that this congruence is due to the relatively homogeneous nature of pelagic habitats, which offer fewer ecological niches [53] and, thus, impose less divergent selective pressures on molecular and morphological traits.

In contrast, the benthopelagic lifestyle exposes species to a wider array of ecological niches, driven by the variability of substrates, topography, and hydrographic conditions near the seafloor [1]. These diverse environments likely promote more rapid morphological evolution relative to molecular changes, resulting in the phylogenetic incongruence observed in Leptochela and other benthopelagic species. This same pattern has been recorded for benthopelagic Pasiphaea species, which inhabit continental slopes and seamounts: species groups proposed by Hayashi [25,26,28] were not entirely consistent with the molecular trees generated by Liao et al. [18]. Similarly, benthic groups like brachiopods [54] exhibit even greater discrepancies between morphological and molecular phylogenetic signals.

Based on these observations, we hypothesize that niche-rich environments accelerate morphological evolution relative to molecular changes. We encourage further investigation of this hypothesis across other taxonomic groups to better understand the relationship between ecological diversity and phylogenetic incongruence.

4.2. Taxonomical Implications

Given that the phylogenetic positions of many Leptochela species remain unresolved, we are cautious about proposing new infrageneric taxa, such as subgenera or species groups, at this time. Instead, we suggest that the three clades identified in our study may form the core for potential species groups that could be refined in future analyses, incorporating the remaining Leptochela species.

Our analysis does not support the subgenus Probolura, as proposed by Chace [2]. The morphological features associated with Probolura, specifically the presence of a dorsal lappet on the sixth abdominal somite and the arrangement of dorsolateral spines on the telson, do not align with the distribution of these characters among the clades we identified.

In conclusion, we describe a new species, provide a comprehensive inventory of all currently recognized Leptochela species and their key qualitative morphological traits (Table 2), and present a key to species for future identification efforts.

Table 2.

Similarities and differences between species of Leptochela may be used as the key to species. ‘-’—absent; ‘+’—present.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d16120760/s1. Table S1: The character coding; Table S2: Dataset of character states; Table S3: Primer information and protocols used for PCR amplification; Table S4: Details of the analyzed species and sequences used in the study; Table S5: Partitioning scheme and best models selected by PartitionFinder2. Ref. [55] have been cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

A.A.L. analyzed specimens morphologically. D.N.K. ran genetic analyses. A.L.V., A.A.L. and D.N.K. wrote the paper and participated in the revisions of it. J.O. and L.C. contributed to material supply and SEM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out in the framework of the state assignment [FMWE-2024-0023–sample collection and taxonomic processing] and supported by the Russian Science Foundation [Project No. 22-14-00187–morphological and molecular analyses].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Key to Species of Leptochela (see also Table 2.)

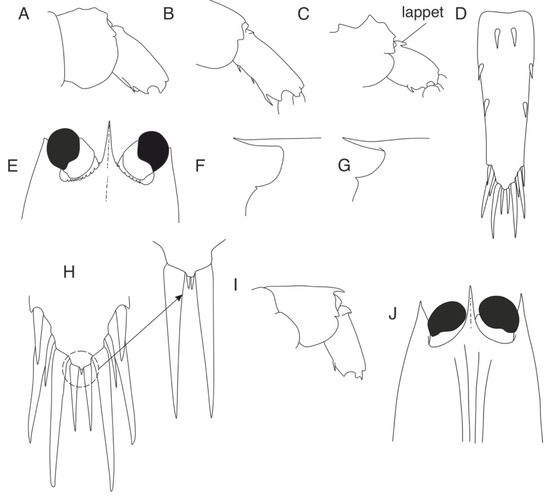

- 1. Sixth pleonic somite with one spine on ventrolateral margin (Figure 8A)………..……………………………………………………………………………………… 2

- -

- Sixth pleonic somite with two or three spines on ventrolateral margin (Figure 8B)… ………………………………………………………………...……….15

- 2. Sixth pleonic somite without dorsal lappet (Figure 8A)………………………………………………………………………………………………....3

- -

- Sixth pleonic somite bearing movable lappet near anterior end of dorsal surface (Figure 8C)…………………………………………………………… 17

- 3. Telson armed with one pair of dorsomesial and two pairs of dorsolateral spines in addition to five pairs of prominent spines in posterior series (Figure 8D) ……………………………………….……………………….…………………………………....4

- -

- Telson armed with one pair of dorsomesial and one pair of dorsolateral spines in addition to posterior series………………..……………………....….7

- 4. Suborbital angle dentate; orbital margin serrate dorsolaterally (Figure 8E) ………………………………………………………………........……………...… L. serratorbita

- -

- Suborbital angle rounded, orbital margin with one medially directed tooth on ventral portion (Figure 8F) or unarmed……………………………………. 5

- 5. Orbital margin with one medially directed tooth (Figure 8F) ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..6

- -

- Orbital margin smooth………………………………………….……. L. crosnieri

- 6. Appendix masculina (not including spines) on second male pleopod rarely overreaching appendix interna; ovigerous females with postorbital carapace length less than 5 mm ……………………………………………………………………..……..L. irrobusta

- -

- Appendix masculina (not including spines) far overreaching appendix interna; ovigerous females with postorbital carapace length more than 6 mm …………....……………………………………………………………… L. robusta

- 7. Suborbital angle acute (Figure 8F) ………………………….……….…...... L. pugnax

- -

- Suborbital angle rounded……………………………………………..….……. 8

- 8. Fifth pleonic somite dorsally uneven (Figure 8A,C)………………………………..9

- -

- Fifth pleonic somite dorsally convex or nearly straight ……………………………..11

- 9. Fifth pleonic somite with three mount-like mediodorsal protrusions and well-defined backward lappet on posterior margin (Figure 8A) …………...L. elevata sp.n.

- -

- Fifth pleonic somite without well-defined backward lappet on posterior margin …………………………………………………………………….…..…10

- 10. Telson without pair of minute spines between bases of median pair of large posterior spines (Indo-West Pacific)........................................................................... L. japonica

- -

- Telson with a pair of minute spines between bases of median pair of large posterior spines (Western Atlantic) (Figure 8H)…………………. L. papulata

- 11. Fifth pleonic somite with prominent sharp dorsal posteromedian tooth (Figure 8I)……………………………………………………………………………………….. L. gracilis

- -

- Fifth pleonic somite unarmed (Figure 8B) …………………………….……12

- 12. Telson with pair (sometimes fused) of minute spines between bases of median pair of large posterior spines (Figure 8H)………………………………………...……….. 13

- -

- Telson without pair of minute spines between bases of median pair of large posterior spines……………………………………………………………….. 14

- 13. Dorsal margin of orbit smooth ……………………………………..... L. bermudensis

- -

- Dorsal margin of orbit finely serrate under high magnification ………….………………………………………………………….....L. hawaiiensis

- 14. Carapace with three longitudinal dorsal ridges in males and females; basal antennal segments concealed by carapace (Figure 8J) ………………………....L. aculeocaudata

- -

- Carapace with dorsolateral longitudinal ridges only in breeding females; basal antennal segments not concealed by carapace ………………………………….…………………………….............. L. sydniensis

- 15. Orbital margin with medially directed tooth on ventral portion (Figure 8F).................................................................................................................................... L. tuerkayi

- -

- Orbital margin unarmed ………………………….……………..……………16

- 16. Suborbital angle of carapace rounded; fifth pleonic somite not carinate; sixth pleonic somite without posterodorsal spine …………………………………..…..…L. chacei

- -

- Suborbital angle of carapace acute (Figure 8G); Fifth pleonic somite bluntly carinate; sixth pleonic somite with posterodorsal spine ……………………….………...… L. nasimae

- 17. Abdomen, fifth segment armed with dorsal spine on posterior margin … L. soelae

Abdomen, fifth segment without dorsal spine on posterior margin …….…L. carinata

Figure 8.

Morphological charactersistics of Leptochela species. (A) L. japonica, fifth and sixth pleonal somites, lateral view; (B) L. chacei, sixth pleonal somite, lateral view; (C) L. carinata, fifth and sixth pleonal somites, lateral view; (D) L. serratorbita, telson, dorsal view; (E) L. serratorbita, anterior part of carapace, dorsal view; (F) L. robusta, rostrum and eye orbit, lateral view; (G) L. pugnax, rostrum and eye orbit, lateral view; (H) L. papulata, tip of telson; (I) L. gracilis, fifth and sixth pleonal somites, lateral view; (J) L. aculeocaudata, anterior part of carapace, dorsal view.

References

- Vereshchaka, A.L. Macroplankton in the near-bottom layer of continental slopes and seamounts. Deep-Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1995, 42, 1639–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chace, F.A., Jr. Shrimps of the Pasiphaeid Genus Leptochela with Descriptions of Three New Species (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea); Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- GBIF Backbone Taxonomy; GBIF Secretariat: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Stimpson, W. Prodromus descriptionis animalium evertebratorum, quae in Expeditione ad Oceanum Pacificum Septentrionalem, a Republic Federata missa, Cadwaladore Ringgold et Johanne Rodgers Ducibus, observavit et descripsit. Pars VIII, Crustacea Macrura. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1860, 12, 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bate, C.S. Report on the Crustacea Macrura collected by the Challenger during the years 1873–1876. Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873–1876. Zoology 1888, 24 Pt 52. i–xc, 1–942, pls. 1–150. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, O. Studies on Crustacea of the Red Sea with Notes Regarding Other Seas. Part 1 Podophthalmata and Edriophthalmata (Cumacea); Tipografiia, K., Kulzhenko, S.V., Eds.; 1875. i–xiv, 1–144, pls. 1–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann, A.E. Decapoden und Schizopoden. In Ergebnisse der Plankton-Expedition der Humboldt-Stiftung. Hensen, V., Ed.; Kiel und Leipzig, Lipsius und Tischer; 1893; 2.G.b, 1–120, pls. 1–10.

- De Man, J.G. Diagnoses of new species of macrurous decapod Crustacea from the Siboga Expedition. Zool. Meded. 1916, 2, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Gurney, R. A new species of the decapod genus Leptochela from Bermuda. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1939, 3, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakin, W.J.; Colefax, A.N. The plankton of the Australian coastal waters off New South Wales. Part I. With special reference to the seasonal distribution, the phytoplankton, and the planktonic Crustacea, and in particular, the Copepoda and crustacean larvae, together with an account of the more frequent members of the groups Mysidacea, Euphausiacea, Amphipoda, Mollusca, Tunicata, Chætognatha, and some references to the fish eggs and fish larvae. Publ. Univ. Syd. Dep. Zool. Monogr. 1940; 1, 1–209, pls. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.-I.; Miyake, S. A new species of the genus Leptochela from northern Kyushu, Japan (Decapoda, Caridea, Pasiphaeidae). Amakusa Mar. Biol. Lab. 1969, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 9 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hanamura, Y. Caridean shrimps obtained by R.V. “Soela” from north-west Australia, with description of a new species of Leptochela (Crustacea: Decapoda: Pasiphaeidae). Beagle Rec. North. Territ. Mus. Arts Sci. 1987, 4, 15–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.-I. Brief revision of the genus Leptochela with description of two new species (Crustacea, Decapoda, Pasiphaeidae). In Les Fonds Meubles des Lagons de Nouvelle-Calédonie (Sédimentologie, Benthos); Etudes & Thèses, Richer de Forges, B., Eds.; ORSTOM: Paris, France, 1995; Volume 2, pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kazmi, Q.B.; Kazmi, M.A. Biodiversity and Biogeography of Caridean Shrimps of Pakistan; Marine Reference Collection and Resource Center, University of Karachi: Karachi City, Pakistan, 2010; 516p. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gan, Z.; Li, X. A new species of the genus Leptochela (Decapoda, Caridea, Pasiphaeidae) from the Yellow Sea. Crustaceana 2017, 90, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, H.; Toon, A.; Felder, D.; Martin, J.; Finley, M.; Rasmussen, J.; Crandall, K. The decapod tree of life: Compiling the data and moving toward a consensus of decapod evolution. Arthropod Syst. Phylogeny 2009, 67, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; De Grave, S.; Ho, T.W.; Ip, B.H.Y.; Tsang, L.M.; Chan, T.Y.; Chu, K.H. Molecular phylogeny of Pasiphaeidae (Crustacea, Decapoda, Caridea) reveals systematic incongruence of the current classification. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017, 115, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunina, A.A.; Kulagin, D.N.; Vereshchaka, A.L. Oplophoridae (Decapoda: Crustacea): Phylogeny, taxonomy and evolution studied by a combination of morphological and molecular methods. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 186, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunina, A.A.; Kulagin, D.N.; Vereshchaka, A.L. Phylogenetic revision of the shrimp genera Ephyrina, Meningodora and Notostomus (Acanthephyridae: Caridea). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 193, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunina, A.A.; Kulagin, D.N.; Vereshchaka, A.L. The taxonomic status of Hymenodora (Crustacea: Oplophoroidea): Morphological and molecular analyses suggest a new family and an undescribed diversity deep in the sea. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2024, 200, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchaka, A.L.; Corbari, L.; Kulagin, D.N.; Lunina, A.A.; Olesen, J. A phylogeny-based revision of the shrimp genera Altelatipes, Benthonectes and Benthesicymus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Benthesicymidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 189, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchaka, A.L.; Kulagin, D.N.; Lunina, A.A. A phylogenetic study of krill (Crustacea: Euphausiacea) reveals new taxa and co-evolution of morphological characters. Cladistics 2019, 35, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchaka, A.L.; Kulagin, D.N.; Lunina, A.A. Across the benthic and pelagic realms: A species-level phylogeny of Benthesicymidae (Crustacea: Decapoda). Invertebr. Syst. 2021, 35, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.-I. Crustacea Decapoda: Revision of Pasiphaea sivado (Risso, 1816) and related species, with descriptions of one new genus and five new species (Pasiphaeidae). In Résultats des Campagnes MUSORSTOM; Crosnier, A., Ed.; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle: Paris, France, 1999; pp. 267–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.-I. Revision of the Pasiphaea cristata Bate, 1888 species group of Pasiphaea Savigny, 1816, with descriptions of four new species, and referral of P. australis Hanamura, 1989 to Alainopasiphaea Hayashi, 1999 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Pasiphaeidae). In Tropical Deep-sea Benthos; Marshall, B.A., Richer de Forges, B., Eds.; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle: Paris, France, 2004; pp. 319–373. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.-I. A new species of the Pasiphaea sivado species group from Taiwan (Decapoda, Caridea, Pasiphaeidae). Zoosystema 2006, 28, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.-I. Revision of the Pasiphaea alcocki species group (Crustacea, Decapoda, Pasiphaeidae). In Tropical Deep-sea Benthos; de Forges, B., Richer, J.L., Eds.; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 193–241. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, K. The parsimony ratchet, a new method for rapid parsimony analysis. Cladistics 1999, 15, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloboff, P.; Farris, S.; Nixon, K. TNT: Tree Analysis Using New Technology. 2000. Available online: http://www.lillo.org.ar/phylogeny/tnt (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Maddison, W.; Maddison, D. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis Version 3.81; 2023 2001. Available online: https://mesquiteproject.org (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Schubart, C.D.; Huber, M.G.J. Genetic comparisons of German populations of the stone crayfish, Austropotamobius torrentium (Crustacea: Astacidae). Bull. Français Pêche Piscic. 2006, 380–381, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubart, C.D.; Cuesta, J.A.; Felder, D.L. Glyptograpsidae, a new brachyuran family from Central America: Larval and adult morphology, and a molecular phylogeny of the Grapsoidea. J. Crustac. Biol. 2002, 22, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuschel, S.; Schubart, C.D. Phylogeny and geographic differentiation of Atlanto–Mediterranean species of the genus Xantho (Crustacea: Brachyura: Xanthidae) based on genetic and morphometric analyses. Mar. Biol. 2006, 148, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgan, D.J.; McLauchlan, A.; Wilson, G.D.F.; Livingston, S.P.; Edgecombe, G.D.; Macaranas, J.; Cassis, G.; Gray, M.R. Histone H3 and U2 snRNA DNA sequences and arthropod molecular evolution. Aust. J. Zool. 1998, 46, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, L.M.; Chan, T.-Y.; Ahyong, S.T.; Chu, K.H. Hermit to king, or hermit to all: Multiple transitions to crab-like forms from hermit crab ancestors. Syst. Biol. 2011, 60, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. MBE 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abascal, F.; Zardoya, R.; Telford, M.J. TranslatorX: Multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W7–W13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. Partitionfinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981, 17, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, D.; Klein, J.; Antonelli, A.; Silvestro, D. raxmlGUI 2.0: A graphical interface and toolkit for phylogenetic analyses using RAxML. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.E. The Development of a Spatial Synoptic Climatological Index for Environmental Analysis; University of Delaware: Newark, DE, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D.A.T. (Ed.) Numerical Palaeobiology; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.H.; Yu, X.; DeSalle, R. Assessing the relative contribution of molecular and morphological characters in simultaneous analysis trees. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1998, 9, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisani, D.; Benton, M.J.; Wilkinson, M. Congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies. Acta Biotheor. 2007, 55, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, J.N.; Garwood, R.J.; Sansom, R.S. Phylogenetic congruence, conflict and consilience between molecular and morphological data. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2023, 23, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, P.O. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst. Biol. 2001, 50, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Molecular Evolution: A Statistical Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S.; Palci, A. Morphological phylogenetics in the genomic age. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, R922–R929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey-Collas, M.; McQuatters-Gollop, A.; Bresnan, E.; Kraberg, A.C.; Manderson, J.P.; Nash, R.D.; Trenkel, V.M. Pelagic habitat: Exploring the concept of good environmental status. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 2333–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapst, D.W.; Schreiber, H.A.; Carlson, S.J. Combined analysis of extant Rhynchonellida (Brachiopoda) using morphological and molecular data. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, L.M.; Ma, K.Y.; Ahyong, S.T.; Chan, T.Y.; Chu, K.H. Phylogeny of Decapoda using two nuclear protein-coding genes: Origin and evolution of the Reptantia. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2008, 48, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).