Abstract

The latest reorganization of the Vertebrate collections preserved at the “Pietro Doderlein” Museum of Zoology of the University of Palermo (Italy) has made it possible to draw up a check-list of the Mammal taxa present in the stuffed (M), fluid-preserved (ML) and anatomical (AN) collections. The intervention was planned under the National Biodiversity Future Center (NBFC) agenda, focused on the enhancement of Italian natural history museums. The growing interest in museum collections strongly demands databases available to the academic and policy world. In this paper, we record 679 specimens belonging to 157 specific taxa arranged in 58 families and 16 orders. Most of the species (75.1%) come from the Palaearctic Region (southern Mediterranean and North Africa), with a minority of taxa coming from the Afrotropical (7.8%), Neotropical (4.6%), Indo-Malayan (3.4%) and Australasian (1%) regions. Among the 24% of the taxa listed in the IUCN categories as threatened (VU, EN, CR, RE) the specimens of the Sicilian wolf, a regional endemic subspecies that became extinct in the last century, stand out. Even if small (<1000 specimens), the collection of mammals of the Museum of Zoology is an important asset for research on biodiversity in the Mediterranean area, representing an international reference for those wishing to conduct morphological and genetic studies in this area.

1. Introduction

Natural history museums are a source of public entertainment and are useful to observe and understand the richness of life around us. At the same time, they play a key role in supporting biodiversity and nature conservation-related research. The museum collections, often associated only with taxonomy, support the studies of a much wider range of topics that have practical applications for biodiversity conservation. They have a fundamental role in preserving the historical wildlife heritage of a region, mirroring its past and current biodiversity [1,2,3], and they enable researchers to track the genetic modification of species, in light of the anthropogenic impacts regarding habitat destruction and degradation. In addition, they can provide a spatiotemporal window into a broad range of research fields, such as taxonomy, anatomy, ecology, conservation, and public health [4].

The potential of natural history museums to serve as a large reservoir of historical/ancient DNA has long been recognized [4]. In fact, despite the degradation processes of biological material over time [5], methodological advances now allow us to obtain precious genetic inferences from degraded samples, such as the ones from museums and archives [6,7,8,9]. In this context, museomics represents an emergent and promising field, which takes advantage of the potentiality of genomics, paleogenomics, and paleoproteomics applied to natural history museum specimens [10]. Therefore, every single museum sample can potentially preserve a genetic record, which can be useful to understand the evolutionary history of the species to which it belongs.

As many of the samples date to before the extreme biodiversity loss caused by anthropogenic drivers, we can generate baseline data for most of the endangered species, which can be compared to the current situation to quantify the human impact [11]. However, despite this enormous potential, the natural history collections remain largely unexplored and unused, mainly because updated and standardized taxonomic lists are still lacking. This situation hinders the formation of an open-access database that can be easily consulted online by all scientific institutions interested in wildlife biodiversity.

Italy is the most biodiverse country in Europe; as indicated in Italy’s fifth national report to the convention on biological diversity 2009–2013, Italy hosts about 30% of the animals and 50% of the plants present on the continent, in an area that represents just 1/30 of the total. This condition is mainly due to habitat richness, the geographical position of the peninsula in the centre of the Mediterranean area, and the historical legacy of the Quaternary glaciations (e.g., [12]). Moreover, Italy has a high level of endemicity; about 10% of the Italian mammal fauna is endemic [13,14].

The diversity and richness of species are mirrored in the big and small museums distributed throughout the country. Millions of specimens are stored in Italian museums and represent a highly valuable resource, available for research (e.g., [15,16]) and lifelong learning [1]. The rationalization and aggregation of this biological heritage in modern and usable repositories are prerequisites for the enhancement of the Italian natural history collections, still scattered and underutilized both in the country and in terms of dissemination and science teaching [1].

In this paper, we provide the inventory of all the mammal species preserved in the collection of the Museum of Zoology of the University of Palermo (hereafter MZPA), now named after its founder, professor Pietro Doderlein, established in Sicily, southern Italy, in 1863. Its collections, dating back to the time of activity (1863–1920) of the founder and his collaborators [1], have recently been re-evaluated. Specialists have given impetus to new research that has enriched the knowledge of the Mediterranean fauna through the study of old documents and specimens, such as the first historical evidence of the presence of the copper shark Carcharinus brachyurus in the Mediterranean Sea [17], the taxonomic validation of Cerna sicana (Doderlein, 1882), the specific name of a grouper described by Doderlein [18]; or through the molecular analysis of museum materials, like the description of a new genetically divergent wolf population, named Canis lupus cristaldii [19,20] or the identification of the geographical origin of a lion skeleton [1]. Further, previous works have examined and presented biological materials stored in the MZPA, such as the catalogues of the anatomical collection [21], the fish collection [22], the primate collection [23,24], the cetacean collection [25], and the raptor collection [26].

To follow this process of valorisation and public sharing of MZPA resources, we, for the first time, present here the inventory of mammalian species preserved in fluid or stuffed, and their anatomical parts. This constitutes a starting point to facilitate the use of museum collections of interest for researchers and may contribute to the interconnection of the institutions involved in the activities of the National Biodiversity Future Center (NBFC https://www.nbfc.it/ accessed on 10 February 2023), geared toward the digitalization of natural history museum collections and the development of national information repositories.

2. Materials and Methods

The mammals present in the MZPA are preserved in three ways: the stuffed specimens collected in the Mammal collection (M), the fluid-preserved, mainly in ethanol, in the ML collection, and the anatomical parts of the former specimens (or of others lost during the bombings of the Second World War) collected in the anatomical collection (AN).

The basic information for each piece shows the capture data (location and date, sex, age, etc.) together with the conditions of the specimens and the names of the collectors. In most cases, the primary data for historical specimens came from old notes, old books and manuscripts, or from handwritten labels; in other cases, they were missing. All the specific information for the individual pieces in the collection can be obtained upon request at museozoologia@unipa.it.

The work of taxonomic determination and labelling of the specimens carried out in the past years by the museum staff and by specific contributions [21,23,24,25] has been reviewed and updated to create the most complete inventory of the collection.

For each species, we provide the following information: scientific name and English common name, worldwide distribution, and risk of extinction. We also provide the type of collection (M = stuffed, ML = fluid-preserved, AN = anatomical) and the number of specimens per taxon.

We use the most updated and widely agreed upon taxonomical nomenclature (order, family, and species) as reported in [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

As English common names, we adopt those provided in the IUCN red list (www.iucnredlist.org, accessed on 10 February 2023); the worldwide distribution is summarized in the biogeographical regions where the taxa occur and is mainly based on [27] and on the IUCN red list (www.iucnredlist.org, accessed on 10 February 2023). Finally, depending on the distribution of the taxon and the collection localities, we provide the extinction risk summarized by the IUCN categories, using the Italian Red List [35] and the European or global Red List (based on www.iucnredlist.org, accessed on 10 February 2023).

3. Results

The checklist of the Mammal collection at the MZPA is reported in Table 1 and includes 679 specimens, belonging to 16 orders, 58 families, and 157 specific taxa. Rodentia represents the most abundant order, with 36.7% of specimens, followed by the Carnivora (16.6%), the Soricomorpha (shrews, moles, and similar), with the 12.8%, and the Cetartiodactyla, which includes the former Cetacea and Artiodactyla, with the 10.3%. Altogether, these four orders comprise 76.4% of the specimens. Primates follow, with a remarkable 9.4%, and after come the 11 remaining orders. The latter are underrepresented, with the remaining 14% of specimens.

Table 1.

List of the species preserved in the Mammal collection at the Museum of Zoology “P. Doderlein”, University of Palermo, Italy. The specimens are stored in the stuffed and mounted (M), fluid-preserved (ML), and anatomical (AN) collections (AN* when skeletons or skeletal remains are present). REG = biogeographic region of specimen origin (PAL = Palaearctic, AFR = Afrotropical, IND = Indo-Malayan, NEA = Nearctic, NEOT = Neotropical, AUS = Australasian, DOM = domestic taxa), N = number of specimens per taxon, IUCN = Italian, European, or Global Red List category, depending from the specimen origin (LC = least concern, NT = near threatened, VU = vulnerable, EN = endangered, CR = critically endangered, RE = regionally extinct, DD = data deficient, NA = not applicable). The Red List status for each taxon is evidenced with a colour (the footnote describes the association between colour and IUCN category).

The specimens of 18 taxa in Table 1 are not identified to species level. Most are incomplete body parts or old stuffed specimens in poor condition. More than 30 other specimens are in even worse condition and are not listed in Table 1.

The collection is focused on Italian and southern Mediterranean fauna; it is not by chance that 75% of the specimens come from the Palaearctic. However, the collection holds a good number of mammals from distant regions (Figure 1), such as the Afrotropical (7.8%), Neotropical (5.7%), Indo-Malayan (3.4%), and even Australasian (1.0%). About 40 specimens are domestic taxa, and 11 belong to Homo sapiens.

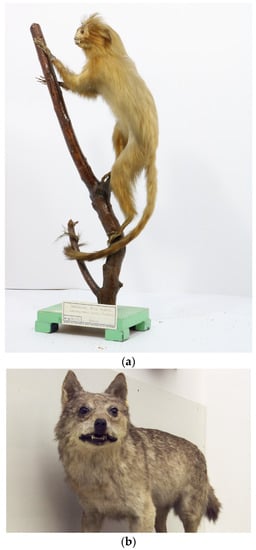

Figure 1.

Some characteristic specimens of the Mammal collection at the Museum of Zoology “P. Doderlein”, University of Palermo, Italy. The stuffed and mounted Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia (a) and Sicilian wolf Canis lupus cristaldii (b) from the original nucleus of the Doderlein era.

About 24% of the 139 taxa classified in the IUCN red lists have an unfavourable conservation status (VU, EN, CR, RE). Among these are the two apes (Pongo pygmaeus, Gorilla gorilla) and the Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica), classified as critically endangered (CR), and the regionally extinct (RE) Sicilian wolf (Canis lupus cristaldii) (Figure 1). The five specimens (2 M, 3 AN) of the latter taxon are among the most notable local taxa in the Mammal collection.

4. Discussion

Museum material can represent an important resource for biodiversity conservation, because zoological collections are the main non-living archive of animal genomes on Earth; the investigation of such collections can help to understand the dynamics of the decline of entire animal groups and the importance of the biodiversity crisis for human and non-human prosperity [36]. In addition to their research potential, museum collections also have a strong impact on the education and dissemination of environmental protection topics to the general public.

The Mediterranean basin is an exceptional hotspot of biodiversity and regional endemisms, with a complex and multifaceted geological history that shaped the biogeographical evolution of the mammalian fauna, particularly in the islands [37]. Sicily, the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, represents an interesting context for the study of modern Mediterranean mammalian species. In fact, the island is attested to have been connected to the Italian peninsula for the last time through a land bridge that disappeared between 17,000 and 25,000 years ago [38]. This favoured the penetration of man and a new stock of mammals, causing the replacement of the previous fauna. The complex history of extinctions and new waves of colonization over the last 10,000 years, together with the action of man on the habitats, has shaped the peculiar community of mammals on the island [39].

For this reason, Sicily and, consequently, the Sicilian Museum collections can be recognized as a significant source of genetic data for the conservation of biodiversity and for reconstructing the history of the populations of mammalian species on the island and throughout the Mediterranean. To date, the continuous phylogeographic investigations of Sicilian mammals have revealed the marked genetic footprint of this fauna, thus leading to the description of endemic species, like the Sicilian pine vole, Microtus nebrodensis (Minà-Palumbo, 1868) [40]; or distinct haplogroups (e.g., Apodemus sylvaticus [41]; Muscardinus avellanarius [42]; Martes martes [43]), which offer an intriguing history of fauna colonization during the Quaternary up to more recent historical times.

Most likely, the Sicilian wolf summarizes the value of historical collections of the MZPA in the light of museomics, an emerging field in Italy [1]. This predator, present in Sicily with a rich fossil record since the upper Pleistocene, represented the only Mediterranean island population of this species before it was extirpated by humans at the beginning of the 19th century. The Sicilian wolf became extinct, leaving few documents and less than a dozen museum exhibits [44]. Half of these, which also include the paratype (a mounted adult male labelled M18) of Canis lupus cristaldii [19], have been preserved thanks to the presence of the MZPA collections. The results of the morphological and molecular analysis of historical DNA assigned it to the new subspecies C. l. cristaldii [19,20] and show a complex history of long-term isolation and admixture with ancient dogs [2]. Furthermore, the wolf is a charismatic species [45] in public perception and could be useful for targeting conservation campaigns and biodiversity erosion.

Regarding the whole collection of specimens housed in the MZPA, two main groups can be identified, with the first nucleus formed by mounted, stuffed specimens and anatomical parts dating back to the Doderlein era. Most of the Italian specimens from Modena (northern Italy), the former university chair of P. Doderlein, and from the Neotropical, Australasian and other distant biogeographical regions are found in this nucleus.

The second nucleus, mostly fluid-preserved and stored in jars, comes from collections from 1980–2020, collected during field expeditions to investigate the systematics and phylogeography of Mediterranean soricomorphs, mostly Crocidura shrews (cf. [46,47,48]) and Talpa moles, Muridae rodents [41], and Gliridae dormice (Glis glis: cf. [49,50,51] and Muscardinus avellanarius: [42,52]).

In this context, there is also an urgent need for the research community to adopt best practices and standardized protocols acquired by the historical/ancient DNA field, in order to justify the partial destruction of samples and to maximize results. Thus, while museomics can be a powerful tool, it should be undertaken with caution and accuracy by scholars with specialized skills to understand the extent of the technical challenges related to the conservation of the genetic material and evaluate the feasibility and the opportunity of the study [5].

Furthermore, for all the above reasons, it is clear that the checklist is the necessary baseline to implement future studies on mammalian diversity not only in Italy and in the Mediterranean area, but also globally. For example, the series of extra-Palearctic specimens, such as the Cebid monkeys collected in Doderlein’s time, could be usefully employed in systematic reviews such as the latest papers, cf. [53].

In conclusion, this paper represents a contribution to the enhancement of the biological heritage contained in the MZPA, thus initiating the necessary process of interconnection between the institutions involved in the activities of the National Biodiversity Future Center. The collection could grow with the addition of new specimens in the future, as NBFC has planned monitoring activities and Citizen Science initiatives; further private collections are expected to be donated instead of being discarded by the successors of the amateurs who collected specimens in the past.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.S., S.L.B. and E.C.; methodology: M.S., S.L.B. and E.C.; formal analysis: M.S.; data curation, A.B. and R.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., S.L.B. and E.C.; writing—review and editing M.S., S.L.B., R.I. and E.C.; supervision: M.S.; funding acquisition: S.L.B. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support of the Sistema Museale di Ateneo (SiMuA) of the University of Palermo and the NBFC to University of Palermo, funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, PNRR, Missione 4 Componente 2, “Dalla ricerca all’impresa”, Investimento 1.4, Project CN00000033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Enrico Bellia for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cilli, E.; Fontani, F.; Ciucani, M.M.; Pizzuto, M.; di Benedetto, P.; de Fanti, S.; Mignani, T.; Bini, C.; Iacovera, R.; Pelotti, S.; et al. Museomics Provides Insights into Conservation and Education: The Instance of an African Lion Specimen from the Museum of Zoology Pietro Doderlein. Diversity 2023, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucani, M.M.; Ramos-Madrigal, J.; Hernández-Alonso, G.; Carmagnini, A.; Aninta, S.G.; Scharff-Olsen, C.H.; Lanigan, L.T.; Fracasso, I.; Clausen, C.G.; Aspi, J.; et al. Genomes of the Extinct Sicilian Wolf Reveal a Complex History of Isolation and Admixture with Ancient Dogs. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiralongo, F.; Badalamenti, R.; Arizza, V.; Prieto, L.; lo Brutto, S. The Portuguese Man-of-War Has Always Entered the Mediterranean Sea—Strandings, Sightings, and Museum Collections. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raxworthy, C.J.; Smith, B.T. Mining Museums for Historical DNA: Advances and Challenges in Museomics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilli, E. Archaeogenetics. In Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 2nd ed.; Rehren, T., Nikita, E., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, in press.

- Puncher, G.N.; Cariani, A.; Cilli, E.; Massari, F.; Leone, A.; Morales-Muñiz, A.; Onar, V.; Toker, N.Y.; Bernal Casasola, D.; Moens, T.; et al. Comparison and Optimization of Genetic Tools Used for the Identification of Ancient Fish Remains Recovered from Archaeological Excavations and Museum Collections in the Mediterranean Region. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2019, 29, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roycroft, E.; Moritz, C.; Rowe, K.C.; Moussalli, A.; Eldridge, M.D.B.; Portela Miguez, R.; Piggott, M.P.; Potter, S. Sequence Capture from Historical Museum Specimens: Maximizing Value for Population and Phylogenomic Studies. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.J.; di Natale, A.; Bernal-Casasola, D.; Aniceti, V.; Onar, V.; Oueslati, T.; Theodropoulou, T.; Morales-Muñiz, A.; Cilli, E.; Tinti, F. Exploitation History of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean-Insights from Ancient Bones. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2022, 79, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agne, S.; Naylor, G.J.P.; Preick, M.; Yang, L.; Thiel, R.; Weigmann, S.; Paijmans, J.L.A.; Barlow, A.; Hofreiter, M.; Straube, N. Taxonomic Identification of Two Poorly Known Lantern Shark Species Based on Mitochondrial DNA from Wet-Collection Paratypes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalueza-Fox, C. Museomics. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R1214–R1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.L.; Díez-del-Molino, D.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Bertola, L.D.; Borges, F.; Cubric-Curik, V.; de Navascués, M.; Frandsen, P.; Heuertz, M.; Hvilsom, C.; et al. Ancient and Historical DNA in Conservation Policy. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 37, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taberlet, P.; Fumagalli, L.; Wust-Saucy, A.G.; Cosson, J.F. Comparative Phylogeography and Postglacial Colonization Routes in Europe. Mol. Ecol. 1998, 7, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loy, A.; Aloise, G.; Ancillotto, L.; Angelici, F.M.; Bertolino, S.; Capizzi, D.; Castiglia, R.; Colangelo, P.; Contoli, L.; Cozzi, B.; et al. Mammals of Italy: An Annotated Checklist. Hystrix Ital. J. Mammal. 2019, 30, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, C.; Boitani, L.; la Posta, S.; Manes, F.; Marchetti, M. Stato Della Biodiversità in Italia: Contributo Alla Strategia Nazionale per La Biodiversità; Palombi Editori: Roma, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Movalli, P.; Duke, G.; Ramello, G.; Dekker, R.; Vrezec, A.; Shore, R.F.; García-Fernández, A.; Wernham, C.; Krone, O.; Alygizakis, N.; et al. Progress on Bringing Together Raptor Collections in Europe for Contaminant Research and Monitoring in Relation to Chemicals Regulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 20132–20136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movalli, P.; Koschorreck, J.; Treu, G.; Slobodnik, J.; Alygizakis, N.; Androulakakis, A.; Badry, A.; Baltag, E.; Barbagli, F.; Bauer, K.; et al. The Role of Natural Science Collections in the Biomonitoring of Environmental Contaminants in Apex Predators in Support of the EU’s Zero Pollution Ambition. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomadakis, P.N.; Vacchi, M.; di Muccio, S.; Sará, M. First Historical Record of Carcharhinus brachyurus (Chondrichthyes, Carcharhiniformes) in the Mediterranean Sea. Ital. J. Zool. 2009, 76, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, E.; Cerasa, G.; Cigna, V.; lo Brutto, S.; Massa, B. Epinephelus sicanus (Doderlein, 1882) (Perciformes: Serranidae: Epinephelinae), a Valid Species of Grouper from the Mediterranean Sea. Zootaxa 2020, 4758, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelici, F.; Rossi, L. A New Subspecies of Grey Wolf (Carnivora, Canidae), Recently Extinct, from Sicily, Italy. Boll. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Verona 2018, 42, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Angelici, F.M.; Ciucani, M.M.; Angelini, S.; Annesi, F.; Caniglia, R.; Castiglia, R.; Fabbri, E.; Galaverni, M.; Palumbo, D.; Ravegnini, G.; et al. The Sicilian Wolf: Genetic Identity of a Recently Extinct Insular Population. Zoolog. Sci. 2019, 36, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarà, M. La collezione di apparati anatomici del museo di Zoologia dell’Università di Palermo. Nat. Sicil. 1985, IX, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sarà, R.; Sarà, M. La collezione ittiologica Doderlein nel Museo di Zoologia di Palermo. Museol. Sci. 1990, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, G.; Sineo, L. The Primatological Collection of the Doderlein Museum in Palermo, Italy. In Le Collezioni Primatologiche Italiane; Bruner, E., Gippoliti, S., Eds.; Istituto Italiano di Antropologia: Roma, Italy, 2006; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo, G. La Museologia Naturalistica: Il Museo Doderlein e La Sua Collezione Primatologica; Università di Palermo: Palermo, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Insacco, G.; Buscaino, G.; Buffa, G.; Cavallaro, M.; Crisafi, E.; Grasso, R.; Lombardo, F.; lo Paro, G.; Parrinello, N.; Sarà, M.; et al. Il Patrimonio Delle Raccolte Cetologiche Museali Della Sicilia. Museol. Sci. Mem. 2014, 12, 391–405. [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco, M.R.; Mandalà, G.; Consentino, M.C.; Ientile, R.; Lo Valvo, F.; Movalli, P.; Sabella, G.; Spadola, F.; Spinnato, A.; Toscano, F.; et al. The First Inventory of Birds of Prey in Sicilian Museum Collections (Italy). Museol. Sci. 2020, 14, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (Eds.) Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 1. Carnivores; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) Handbook of the Mammals of The World. Vol. 4. Sea Mammals; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) Handbook of the Mammals of The World. Vol. 8. Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Rylands, A.B.; Wilson, D.E. (Eds.) Handbook of the Mammals of The World. Vol. 3. Primates; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Lacher, T.E., Jr.; Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 6. Lagomorphs and Rodents; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Lacher, T.E., Jr.; Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 7. Rodents II; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rondinini, C.; Battistoni, A.; Teofili, C. Lista Rossa IUCN Dei Vertebrati Italiani 2022; Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del territorio e del mare: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Formenti, G.; Theissinger, K.; Fernandes, C.; Bista, I.; Bombarely, A.; Bleidorn, C.; Ciofi, C.; Crottini, A.; Godoy, J.A.; Höglund, J.; et al. The Era of Reference Genomes in Conservation Genomics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 37, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombo, M.R. Insular Mammalian Fauna Dynamics and Paleogeography: A Lesson from the Western Mediterranean Islands. Integr. Zool. 2018, 13, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonioli, F.; Lo Presti, V.; Morticelli, M.G.; Bonfiglio, L.; Mannino, M.A.; Palombo, M.R.; Sannino, G.; Ferranti, L.; Furlani, S.; Lambeck, K.; et al. Timing of the Emergence of the Europe-Sicily Bridge (40–17 Cal Ka BP) and Its Implications for the Spread of Modern Humans. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2016, 411, 111–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruso, D.; Sarà, M.; Surdi, G.; Masini, F. Le faune a mammiferi della Sicilia tra il Tardoglaciale e l’Olocene. Biogeographia 2011, 30, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, A.M.R.; Annesi, F.; Aloise, G.; Amori, G.; Giustini, L.; Castiglia, R. Integrative Taxonomy of the Italian Pine Voles, Microtus savii Group (Cricetidae, Arvicolinae). Zool. Scr. 2016, 45, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaux, J.R.; Magnanou, E.; Paradis, E.; Nieberding, C.; Libois, R. Mitochondrial Phylogeography of the Woodmouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) in the Western Palearctic Region. Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouton, A.; Mortelliti, A.; Grill, A.; Sara, M.; Kryštufek, B.; Juškaitis, R.; Latinne, A.; Amori, G.; Randi, E.; Büchner, S.; et al. Evolutionary History and Species Delimitations: A Case Study of the Hazel Dormouse, Muscardinus avellanarius. Conserv. Genet. 2017, 18, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchioni, L.; Marrone, F.; Costa, S.; Muscarella, C.; Carra, E.; Arizza, V.; Arculeo, M.; Faraone, F.P. The European Pine Marten Martes martes (Linnaeus, 1758) Is Autochthonous in Sicily and Constitutes a Well-Characterised Major Phylogroup within the Species (Carnivora, Mustelidae). Animals 2022, 12, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarà, M. Catalogo dei Mammiferi di Sicilia di Francesco Minà Palumbo, 3rd ed.; Società Messinese di Storia Patria: Messina, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, C.; Luque, G.M.; Courchamp, F. The twenty most charismatic species. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Brutto, S.; Arculeo, M.; Sarà, M. Mitochondrial Simple Sequence Repeats and 12S-RRNA Gene Reveal Two Distinct Lineages of Crocidura russula (Mammalia, Soricidae). Heredity 2004, 92, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarà, M. Crocidura sicula (Miller, 1901). In Mammalia II. Erinaceomorpha, Soricomorpha, Lagomorpha, Rodentia; Amori, G., Contoli, L., Nappi, A., Eds.; Edizioni Calderini e Il Sole 24 Ore: Milano, Italy, 2008; Volume XLIV, pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sarà, M. Crocidura pachyura (Kϋster, 1835). In Mammalia II. Erinaceomorpha, Soricomorpha, Lagomorpha, Rodentia; Amori, G., Contoli, L., Nappi, A., Eds.; Edizioni Calderini e Il Sole 24 Ore: Milano, Italy, 2008; Volume XLIV, pp. 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hürner, H.; Krystufek, B.; Sarà, M.; Ribas, A.; Ruch, T.; Sommer, R.; Ivashkina, V.; Michaux, J.R. Mitochondrial Phylogeography of the Edible Dormouse (Glis glis) in the Western Palearctic Region. J. Mammal. 2010, 91, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Brutto, S.; Sarà, M.; Arculeo, M. Italian Peninsula Preserves an Evolutionary Lineage of the Fat Dormouse Glis glis L. (Rodentia: Gliridae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 102, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaux, J.R.; Hürner, H.; Krystufek, B.; Sarà, M.; Ribas, A.; Ruch, T.; Vekhnik, V.; Renaud, S. Genetic Structure of a European Forest Species, the Edible Dormouse (Glis glis): A Consequence of Past Anthropogenic Forest Fragmentation? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 126, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouton, A.; Grill, A.; Sara, M.; Kryštufek, B.; Randi, E.; Amori, G.; Juškaitis, R.; Aloise, G.; Mortelliti, A.; Panchetti, F.; et al. Evidence of a Complex Phylogeographic Structure in the Common Dormouse, Muscardinus avellanarius (Rodentia: Gliridae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2012, 105, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, J.W.L.; Silva, J.D.E., Jr.; Rylands, A.B. How Different Are Robust and Gracile Capuchin Monkeys? An Argument for the Use of Sapajus and Cebus. Am. J. Primatol. 2012, 74, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).