Abstract

The history of collecting and cataloging Thailand’s diverse herpetofauna is long-standing, with many specimens housed at the Thailand Natural History Museum (THNHM). This work aimed to assess the diversity of herpetofauna within the THNHM collection, ascertain conservation status of species, and track the geographical coverage of these specimens within the country. The THNHM collection boasts an impressive inventory, numbering 173 amphibian species and 335 reptile species. This collection reflects the substantial biodiversity within these taxonomic groups, rivaling the total number of herpetofauna species ever recorded in Thailand. However, the evaluation of their conservation status, as determined by the IUCN Red List, CITES, and Thailand’s Wild Animal Preservation and Protection Act (WARPA), has unveiled disparities in the degree of concern for certain species, possibly attributable to differential uses of the assessment criteria. Notably, the museum houses a number of type specimens, including 27 holotypes, which remain understudied. Sampling efforts have grown considerably since the year 2000, encompassing nearly all regions of the country. This extensive and systematic collection of diverse herpetofauna at the THNHM serves as a valuable resource for both research and educational purposes, enriching our understanding of these species and their significance in the broader context of biodiversity conservation.

1. Introduction

Thailand stands as one among several nations globally that harbors a remarkable diversity of herpetofauna. The documentation of this remarkable variety dates back nearly 300 years, with a substantial expansion of herpetological knowledge occurring during the mid-19th century [1]. Despite this historical accumulation of knowledge, the collection of voucher specimens remains dispersed across various international institutions, lacking effective interconnection. The establishment of the Thailand Natural History Museum (THNHM) serves as a pivotal reference hub for the nation’s biodiversity, functioning as an invaluable resource for both domestic and international research and education endeavors. Much like its counterparts worldwide, the THNHM houses an extensive assortment of herpetofauna voucher specimens originating not only from diverse regions within Thailand but occasionally from sources beyond its borders.

The amphibian diversity in Thailand, as indicated in the most recently published checklist [2], encompasses 194 species, while the 2023 documented reptile count reveals 510 species [3] compared to the 2015 report of 352 species [1]. Online platforms such as the Thai National Parks website contribute significantly to the taxonomic richness instead of collating new records, thereby augmenting the nation’s biodiversity profile. It is important to note that numerous specimens are housed not solely within the THNHM but are distributed across various institutes nationally and internationally. Regrettably, information regarding these collections is not fully shared among taxonomists and researchers, leading to an underutilization of these invaluable resources, given the evolving roles of natural of history museums in the changing world [4,5,6,7].

This paper is intended to evaluate the THNHM herpetofauna collection, the conservation significance of these specimens, and the distribution of collection locations in Thailand in relation to their representation coverage, and potential avenues for advancing scientific research, promoting educational initiatives, and raising public awareness.

2. Materials and Methods

All registration records pertaining to herpetological voucher samples at the THNHM, including data collected until March 2023, were examined. A thorough review and update of the scientific names and taxonomic classifications associated with all these records was conducted. This process involved cross-referencing the data with reliable sources [1,2,3,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Samples designated as “sp.” or “cf.” were excluded from this study.

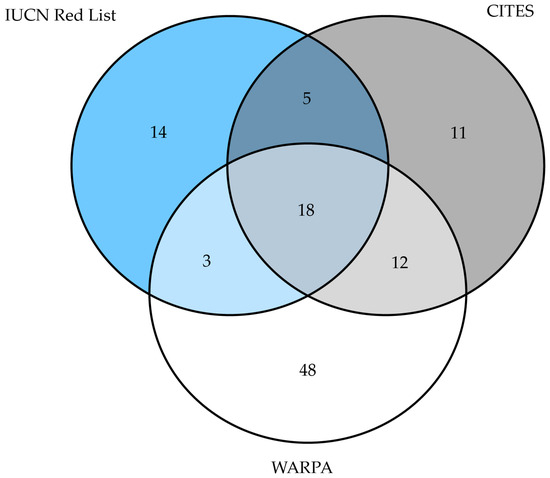

The conservation status of each species identified was evaluated. This evaluation was conducted using both their present taxonomic designations and synonyms, following the guidelines provided by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) for its appendices I, II, and III, and the (Thai National) Wild Animal Preservation and Protection Act (WARPA), B.E. 2535, as amended in B.E. 2562 (year 2019). Species judged of particular conservation were accorded special attention; those listed as either globally Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), or Vulnerable (VU) in the IUCN Red List, those listed in CITES, or species receiving protected status under the WARPA. A Venn diagram was created using R studio [16] to illustrate the agreement among IUCN, CITES, and WARPA about species of conservation concern. Recent verification of the catalogues of type specimens [17] was updated and summarized.

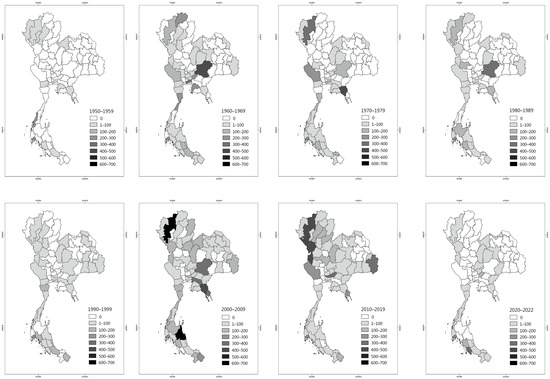

An examination of collection years and locations was conducted to assess the frequency and geographical spread of sampling efforts. In the spatial analysis of museum collection distribution in Thailand, only specimens that included information about their collection location were incorporated into the map. Samples collected prior to 1950 were excluded due to their scarcity for each individual year and the unreliability of collection dates. In cases where the georeferenced coordinates of certain specimens were unclear, the coordinates of the respective province were employed, and the specimens were mapped based on the province of collection. The maps illustrate the distribution of samples from 1950 to the present, as well as separate maps for each 10-year interval. Thailand map layers, delineating provincial boundaries, were generated, and the total number of georeferenced samples in each province was summed using QGIS version 3.4 [18].

3. Results

A total of 27,546 voucher specimens of amphibians and reptiles were cataloged at the THNHM, encompassing 17,721 amphibian specimens and 9825 reptile specimens. The amphibian collection included three orders, consisting of 10 families, 64 genera, and 173 species. The reptile collection represented three orders, 28 families, 115 genera, and 335 species. Within the collection, there were three specimens of non-native amphibians (Bombina bombina, Bufo bufo, and Bufotes viridis) and two specimens of non-native reptiles (Trachemys scripta and Chelodina sp.). Some specimens of non-native species were obtained from a local pet market while some were not specified to locations.

Species of conservation concern are shown in Table 1. Among the amphibians, five were categorized as globally Endangered (EN) while eight species held the status of Vulnerable (VU). Within the reptile collection, seven species fell into the Critically Endangered (CR) category, consisting of six testudines and a single crocodile. Additionally, 10 species were classified as Endangered (EN), and 10 species were designated as Vulnerable (VU).

Table 1.

List of species of conservation concern from the amphibians and reptiles preserved in THNHM; EN = endangered status, VU = vulnerable status, a check mark (✓) = protected species by law.

There were 9 reptilian species listed within CITES https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php (accessed on 15 October 2023) Appendix I, accompanied by 34 species—comprising 5 amphibians and 29 reptiles—in CITES https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php (accessed on 15 October 2023) https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php (accessed on 15 October 2023) Appendix II. Moreover, the Wild Animal Preservation and Protection Act (WARPA) catalogued 81 herpetofauna species as protected animals, of which 10 were amphibians and 71 were reptiles. However, it is important to note that certain herpetofauna species listed on WARPA were, more than once, synonyms of a single species, having undergone taxonomic revisions and consequent changes of names. Species with IUCN threatened status did not always receive legal protection through WARPA. Only 18 species, all of which were reptiles, bore the classification of threatened IUCN categories while simultaneously being protected under WARPA and listed in CITES (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The conservation status of herpetofauna specimens housed at THNHM, as assessed using the IUCN Red List, CITES, and WARPA.

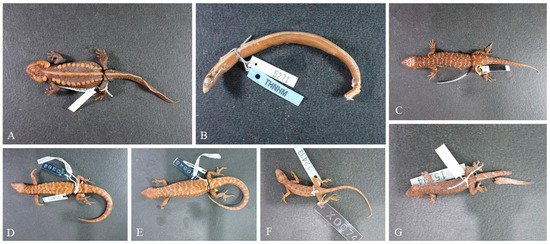

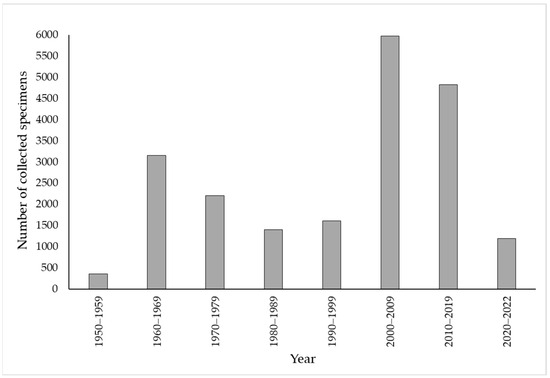

The collection included a subset of voucher specimens of 41 species serving as type specimens (Table 2). Among these, there were 27 holotypes, including 7 amphibian and 20 reptiles, all of which were collected within the last 20 years (Figure 2). Additionally, there were paratypes for 28 species, and some of them had a substantial number of samples. There were 6464 specimens which lacked specified collection dates. A significant increase in specimen collection occurred following the year 2000 (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Voucher specimens designated as type specimens stored at THNHM.

Figure 2.

Examples of holotypes of herpetofaunas stored at THNHM, (A) Tylototriton panhai (THNHM-2800, 71.6 mm SVL); (B) Jarujinia bipedalis (THNHM-15410, 88.2 mm SVL); (C) Tropidophorus hangman (THNHM-5776, 78.2 mm SVL); (D) Tropidophorus latiscutatus (THNHM-5830, 91.3 mm SVL); (E) Tropidophorus matsuii (THNHM-5825, 94.1 mm SVL); (F) Cnemaspis laoensis (THNHM-12433, 40.9 mm SVL); (G) Hemiphyllodactylus chiangmaiensis (THNHM-15194, 41.2 mm SVL).

Figure 3.

Herpetofauna sampling effort from 1950 to 2022.

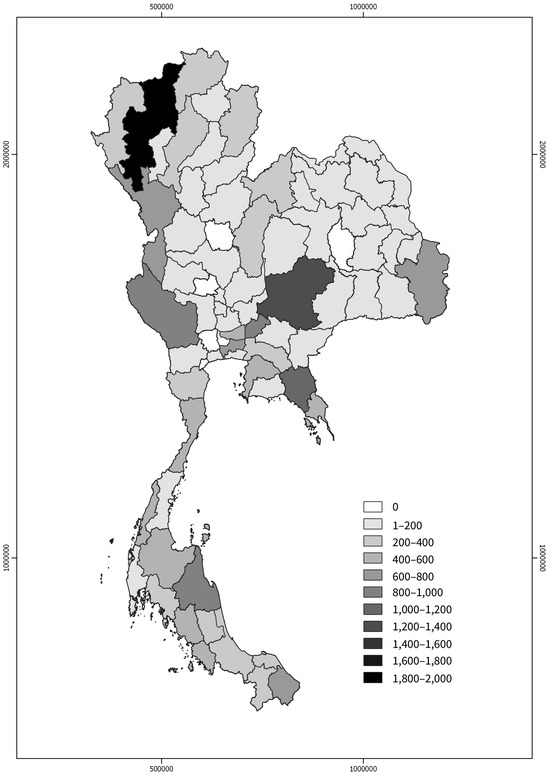

Distribution maps depicting the THNHM collection locations revealed that the collections encompassed nearly every province in Thailand (Figure 4). The greatest number of specimens were collected in Chiang Mai Province (darkest shade) in northern Thailand, the province which has the greatest elevational range. Several other provinces, such as Nakhon Ratchasima in the northeast and Kanchanaburi in the west of Thailand, also displayed concentrated collection efforts. When examining the 10-year interval maps, it was apparent that specimens were not uniformly collected across both years and locations (Figure 5). During the period from 1950–1959, specimens were gathered in only a few provinces in northern Thailand such as Chiang Mai, Mae Hong Son, Lampang and Lamphun, and the southern province of Ranong. Subsequently, the distribution of collection sites expanded to include additional provinces such as Chanthaburi in the east, Ubon Ratchathani in the northeast, Tak in the west, and Nakhon Si Thammarat in the south, but comprehensive coverage was still lacking. However, during 2000–2019, collection efforts surged and encompassed nearly all provinces in Thailand.

Figure 4.

Distribution map of the number of specimens in THNHM collected from 1950 to 2022 by province.

Figure 5.

Distribution map of specimen collection in different provinces and by decade, from 1950 to the present, using different shades, based on THNHM specimens.

4. Discussion

The herpetological collection housed at the THNHM offers invaluable resources for both biodiversity conservation and education. Many of the voucher specimens within this collection serve as type specimens [17] or belong to species of conservation concern. The collection present at the THNHM appears to cover the considerable biodiversity of these taxa well, given the documented herpetofaunal biodiversity of Thailand [1,2,3]. Amphibian diversity within the collection accounted for 89% of amphibians documented in the country [2], while the reptile collection represented 65% of the known reptilian diversity in the country [3]. Some of the collection are type specimens serving as taxonomic references. Non-native species represent only a small fraction of the entire collection. This substantial assemblage affords an opportunity for research and education on species that are challenging to locate within their natural habitats or are of actual or potential conservation concern.

The taxonomic uncertainty of amphibian and reptile classifications has led to confusion within certain families. To resolve this, we have relied on the latest scientific publications to update the nomenclature [12,13,14,15]. Although website resources [8,9,10] have proven to be convenient and fast, they have unfortunately introduced some discrepancies. In such instances, we turned to a comprehensive review of phylogenetic and taxonomic revisions within the literature to guide us in determining the accurate scientific names [11,12,13,14,15,19]. However, some specimens are still listed under synonyms and will require further examination to confirm their identity, such as those of Cnemaspis siamensis whose taxonomy has been recently revised [19]. The significance of maintaining up-to-date scientific names for species cannot be overstated, especially for conservation efforts. These revisions often delineate specific populations, and new names may or may not apply to particular regional populations. Failing to recognize these distinct species and populations could put rare and endangered species at risk [20]. Alterations in species names and definitions can have a direct impact on their conservation status [21]. It is worth noting that several scientific names listed in the WARPA have not been updated, potentially creating legal loopholes in wildlife trade regulation. Consequently, Thai legislation should acknowledge the importance of addressing this issue.

The evaluation of conservation status, as assessed using the IUCN Red List, CITES species list, and WARPA, has revealed inconsistencies in the level of concern for certain species. Some species protected under WARPA are not categorized as threatened by either the IUCN or CITES. In fact, many species covered by WARPA are labeled as of “Least Concern” or “Data Deficient” by the IUCN Red List. This incongruity may arise from the differing scales of evaluation employed by these organizations. While the IUCN evaluates species status on a global scale, WARPA focuses exclusively on populations within Thailand. Species categorized as having no conservation concerns may actually comprise small populations that have been inadequately studied, potentially harboring unique characteristics yet to be unveiled. Notable examples include Cyrtodactylus variegatus, Varanus dumerilii, and V. rudicollis. Conversely, some species classified as of conservation concern by the IUCN do not receive protection under WARPA, presumably due to oversight by country authorities. This includes species such as Ansonia siamensis and possibly others which are endemic and rarely encountered. Due to the limited information available for their assessment, further studies are imperative to better understand and address the conservation needs of these species. Since the THNHM houses specimens of many such taxa, including multiple samples from various locations, it serves as an essential resource for acquiring the information needed to stimulate broader and more comprehensive studies. This opportunity extends not only to species of conservation concern but also to the type specimens of several species, some of which are also collected alongside non-type specimens of the same species.

The collection of specimens, when conducted under proper authorization and by well-trained scientific experts, is unlikely to cause harm to natural populations both temporally and spatially [22,23]. Prior to the 1960s, the collection of herpetofauna samples in the country was disorganized and poorly documented. However, since then, international collaborations have facilitated a more systematic biodiversity assessment of herpetofauna and improved documentation [1]. Sampling efforts have encompassed a wide range of habitat types, including mountains, lowland forests, lowland areas, and islands across the country. With increasing survey activities, more instances of new records [24] or the discoveries of new species [25,26,27,28,29] have emerged, unveiling the hidden diversity within this biodiversity-rich region. Additional efforts are likely to yield further revelations and new information.

Given Thailand’s intricate topography and abundant biodiversity, including numerous endemic species, it becomes imperative to conduct specimen collection in a thorough and systematic manner. The distribution maps, reflecting the broad distribution of collection efforts, shed light on the scope of temporally and spatially biased sampling. From 1950 to 1999, sampling activities were largely confined to specific regions. Only during 2000–2019 was sampling and collecting expanded more widely across the country. This skewed distribution in sampling can be attributed to various constraints encountered by the museum. As Thailand is a developing country with a still-growing economy, travel to certain provinces was formerly both inconvenient and, in some cases, potentially even dangerous. Improved infrastructure and public transportation has facilitated better access in recent decades. Accessibility to an area is a vital issue that could cause sampling bias [30]. Secondly, the funding allocated for field collection, primarily sourced from the government, was not always sufficient for comprehensive and systematic sampling. This funding problem has been acknowledged in several countries [23,31,32,33]. Consequently, researchers were formerly restricted to collecting samples from areas that presented economically viable options near their hometowns or in the vicinity of major universities.

THNHM continues to play its traditional role as a center for biodiversity collections. Collaborations among institutes, particularly universities, have paved the way for the expansion of biodiversity research and development. Looking ahead, it is important to note that the herpetofauna collection at the THNHM is not yet fully harnessed for museomics, a new developing research field that demands the comprehensive utilization of museum specimens [34,35]. Additionally, there is significant potential for the digitization of biodiversity collections [36,37] and their application in various research fields, such as public health, and further advanced research in ecology and evolution [4,38,39].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P. and J.K.; methodology, P.P. and J.K.; software, P.P., K.P., A.K. and J.K.; validation, P.P., V.V. and J.K.; formal analysis, P.P., K.P. and J.K.; investigation, P.P., K.P. and J.K.; resources, V.V.; data curation, P.P., K.P., V.V. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, P.P., V.V. and J.K.; visualization, P.P., A.K. and J.K.; supervision, J.K.; project administration, P.P. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the THNHM staff for generously sharing their field experiences and providing access to voucher collections. Special thanks go to Philip D. Round for his valuable comments and insights, and to the reviewers for their helpful suggestions, which have greatly improved our manuscript. Additionally, we wish to dedicate our work to those who have made significant contributions to sampling collections at the THNHM.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chan-ard, T.; Parr, J.W.K.; Nabhitabhata, J. A Field Guide to the Reptiles of Thailand; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; 314p. [Google Scholar]

- Poyarkov, N.A.; Nguyen, T.V.; Popov, E.S.; Geissler, P.; Pawangkhanant, P.; Neang, T.; Suwannapoom, C.; Orlov, N.L. Recent progress in taxonomic studies, biogeographic analysis, and revised checklist of amphibians in Indochina. Russ. J. Herpetol. 2021, 28, 1–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyarkov, N.A.; Nguyen, T.V.; Popov, E.S.; Geissler, P.; Pawangkhanant, P.; Neang, T.; Suwannapoom, C.; Ananjeva, N.B.; Orlov, N.L. Recent progress in taxonomic studies, biogeographic analysis, and revised checklist of reptiles in Indochina. Russ. J. Herpetol. 2023, 30, 255–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A.V.; Tsutsui, N.D. The value of museum collections for research and society. BioScience 2004, 54, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winker, K. Natural history museums in a postbiodiversity era. BioScience 2004, 54, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meineke, E.K.; Davies, T.J.; Daru, B.H.; Davis, C.C. Biological collections for understanding biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 374, 20170386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shultz, A.J.; Adams, B.J.; Bell, K.C.; Ludt, W.B.; Pauly, G.B.; Vendetti, J.E. Natural history collections are critical resources for contemporary and future studies of urban evolution. Evol. Appl. 2020, 14, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.R. Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.1. 2021. Available online: https://amphibiansoftheworld.amnh.org/index.php (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- AmphibiaWeb. Available online: https://amphibiaweb.org (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Uetz, P.; Freed, P.; Aguilar, R.; Reyes, F.; Hošek, J. The Reptile Database. Available online: http://www.reptile-database.org (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Frost, D.R.; Grant, T.; Faivovich, J.; Bain, R.H.; Haas, A.; Haddad, C.F.B.; de Sa, R.O.; Channing, A.; Wilkinson, M.; Donnellan, S.C.; et al. The amphibian tree of life. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2006, 297, 1–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, L.A.; Prendini, E.; Kraus, F.; Raxworthy, C.J. Systematics and biogeography of the Hylarana frog (Anura: Ranidae) radiation across tropical Australasia, Southeast Asia, and Africa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 90, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A.; Ohler, A.; Pyron, A. New concepts and methods for phylogenetic taxonomy and nomenclature in zoology, exemplified by a new ranked cladonomy of recent amphibians (Lissamphibia). Megataxa 2021, 5, 1–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, G.; Vargas, J.; Than, N.L.; Schell, T.; Janke, A.; Pauls, S.U.; Thammachoti, P. A taxonomic revision of the genus Phrynoglossus in Indochina with the description of a new species and comments on the classification within Occidozyginae (Amphibia, Anura, Dicroglossidae). Vertebr. Zool. 2021, 71, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallach, V.; Williams, K.L.; Boundy, J. Snakes of the World: A Catalogue of Living and Extinct Species; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; 1237p. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Boutros, P.C. VennDiagram: A package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, M.; Makchai, S.; Pongcharoen, C. Updated catalogue of the amphibian and reptile type specimens of the Natural History Museum, National Science Museum, Thailand. Thai Specim. 2022, 2, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. QGISAssociation. 2019. Available online: http://www.qgis.org (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Ampai, N.; Wood, P.L., Jr.; Stuart, B.L.; Aowphol, A. Integrative taxonomy of the rock-dwelling gecko Cnemaspis siamensis complex (Squamata, Gekkonidae) reveals a new species from Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, southern Thailand. ZooKeys 2020, 932, 129–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemmett, A.M.; Groombridge, J.J.; Hare, J.; Yadamsuren, A.; Burger, P.A.; Ewen, J.G. What’s in a name? Common name misuse potentially confounds the conservation of the wild camel Camelus ferus. Oryx 2023, 57, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Ballou, J.D.; Dudash, M.R.; Eldridge, M.D.B.; Fenster, C.B.; Lacy, R.C.; Mendelson, J.R., III; Porton, I.J.; Ralls, K.; Ryder, O.A. Implications of different species concepts for conserving biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 153, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.; Aleixo, A.; Allen, G.; Almeda, F.; Baldwin, C.; Barclay, M.; Bates, J.; Bauer, A.; Benzoni, F.; Berns, C.; et al. Specimen collection: An essential tool. Science 2014, 344, 814–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreone, F.; Ansaloni, I.; Bellia, E.; Benocci, A.; Betto, C.; Bianchi, G.; Boano, G.; de Loewestern, A.B.; Brancato, R.; Bressi, N.; et al. Threatened and extinct amphibian and reptiles in Italian natural history collections are useful conservation tools. Acta Herpetol. 2022, 17, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promnun, P.; Khudamrongsawat, J.; Grismer, J.L.; Tandavanitj, N.; Kongrit, C.; Tajakan, P. Revised distribution and a first record of Leiolepis peguensis Peters, 1971 (Squamata: Leiolepidae) from Thailand. Herpetol. Notes 2021, 14, 893–897. [Google Scholar]

- Hikida, T.; Orlov, N.L.; Nabhitabhata, J.; Ota, H. Three New Depressed-bodied Water Skinks of the Genus Tropidophorus (Lacertilia: Scincidae) from Thailand and Vietnam. Curr. Herpetol. 2002, 21, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuaynkern, Y.; Nabhitabhata, J.; Inthara, C.; Kamsook, M.; Somsri, K. A new species of the water skink Tropidophorus (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) from Northeast Thailand. Thail. Nat. Hist. Mus. J. 2005, 1, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Chan-ard, T.; Makchai, S.; Cota, M. Jarujinia: A New Genus of Lygosomine Lizard from Central Thailand, with a Description of One New Species. Thail. Nat. Hist. Mus. J. 2011, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa, K.; Khonsue, W.; Pomchote, P.; Matsui, M. Two new species of Tylototriton from Thailand (Amphibia: Urodela: Salamandridae). Zootaxa 2013, 3737, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grismer, L.L.; Wood, P.L., Jr.; Cota, M. A new species of Hemiphyllodactylus Bleeker, 1860 (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from northwestern Thailand. Zootaxa 2014, 3760, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daru, B.H.; Rodriguez, J. Mass production of unvouchered records fails to represent global biodiversity patterns. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, W.R.P. Cuts at the British Museum (NH). Nature 1988, 333, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, R. Natural history collections in crisis as funding is slashed. Nature 2003, 423, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.D.; Bradley, L.C.; Garner, H.J.; Baker, R.J. Assessing the value of natural history collections and addressing issues regarding long-term growth and care. BioScience 2014, 64, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, D.C.; Shapiro, B.; Giribet, G.; Moritz, C.; Edwards, S.V. Museum Genomics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2021, 55, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raxworthy, C.J.; Smith, B.T. Mining museums for historical DNA: Advances and challenges in museomics. Trends. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversole, C.B.; Powell, R.L.; Lizarro, D.E.; Moreno, F.; Vaca, G.C.; Aparicio, J.; Crocker, A.V. Introduction of a novel natural history collection: A model for global scientific collaboration and enhancement of biodiversity infrastructure with a focus on developing countries. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 1921–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G.; Ellis, S. The history and impact of digitization and digital data mobilization on biodiversity research. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20170391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindel, D.E.; Cook, J.A. The next generation of natural history collections. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.J.; Cook, J.A.; Zamudio, K.R.; Edwards, S.V. Museum specimens of terrestrial vertebrates are sensitive indicators of environmental change in the Anthropocene. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20170387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).