Abstract

The aim of this paper is to share more information about cumacean crustaceans, specifically their presence, biogeographical distribution, and preferred sediment type in the Italian Seas. Samples were collected on the soft bottom at different sites, ranging from 3 to 158 m in depth, from 2001 to 2021. The specimens collected represented a total of 29 species belonging to 5 families (Bodotriidae, Leuconidae, Nannastacidae, Diastylidae, and Pseudocumatidae). The results were compared with the most recent Italian fauna checklists and the available scientific literature on this group.

1. Introduction

Cumaceans are benthic organisms, generally 1–10 mm in size, that are strongly linked to the seabed where they can burrow tunnels. These organisms are characterized by morphological features that differentiate them from other peracarid crustaceans. For example, the thoracic segments are partially covered by a carapace that extends in a pseudorostrum through which a pair of siphons emerges, as well as a long cylindrical abdomen ending in a telson and a pair of uropods. Cumaceans live in seawater from intertidal shelves to great depths [1] but can also be found in brackish water and rivers [2]. They can be influenced by the type and nature of the sediment, as well as its organic matter content, which can generate changes in their abundance [3,4]. This taxon represents an important link in marine trophic webs because these animals are common food for many species of fish living near the bottom, such as Pleuronectiformes or Mulids [5]. They are also known as indicators of organic enrichment [6] and the eutrophication of soft bottoms [7] and are therefore often used together with other benthic organisms to monitor environmental quality, as also requested by the major European directives (WFD/2000/60/EC; MSFD/2008/56/EC).

Environmental quality assessment, according to the guidelines, involves the use of a species list that associates each species with an ecological class based on the group’s ability to indicate a disturbed or undisturbed environment.

The collection of data allows species lists to be updated with new records, therefore representing an important aspect for the conservation of marine ecosystems and for cumacean taxonomy insiders.

The Order Cumacea (Krøyer, 1846) belongs to the Crustacea subphylum. In total, 8 families, 165 genera, and 1342 species were recorded worldwide [8], of which 6 families, 21 genera, and 45 species are present in Italian Seas [9], accounting for 50% of living species in the Mediterranean Sea (99 species).

The geographical distribution of endemic or non-indigenous species of this taxon, as well as other information, is reported in the Italian checklist [9], whereby nine biogeographical areas were identified. These were defined based on three types of barriers (in a biogeographical sense): (i) physical (submarine ridges), (ii) hydrologic (jet and gyre), and (iii) physiological (surface isotherms) based on marine phytogeography. On the other hand, there are very few studies on the biogeographical distribution and ecology of the cumacean of the Italian Seas [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]; many studies have instead been carried out on the west basin of the Mediterranean Sea [17,18] or in the Levantine area of the Mediterranean Sea [19].

This paper presents the data collected during scientific surveys conducted by the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) in the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Seas from 2001 to 2021. The species collected were compared with those present in the Italian checklist to verify their presence in nine biogeographical areas. Information on bathymetries and sediment type where the organisms lived is also provided to increase taxon knowledge.

2. Materials and Methods

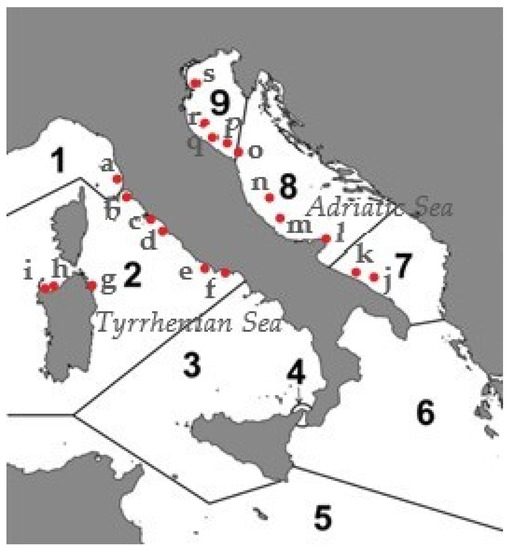

The material examined originated from different survey projects conduced from 2001 to 2021. The specimens were collected at 19 Italian sites (Figure 1) on soft bottoms, some of which were located in the Tyrrhenian Sea (Livorno, Follonica, Porto Ercole, Montalto di Castro, Castel Porziano, Nettuno, Olbia, Punta Tramontana, and Fiume Santo), while others were located in the Adriatic Sea (Bisceglie, Bari, Vieste, Pescara, San Benedetto del Tronto, Ancona, Pesaro, Rimini, Ravenna, and Chioggia).

Figure 1.

The study area shows the locations of the sampling sites. a = Livorno, b = Follonica, c = Porto Ercole, d = Montalto di Castro, e = Castel Porziano, f = Nettuno, g = Olbia, h = Punta Tramontana, i = Fiume Santo, j = Bisceglie, k = Bari, l = Vieste, m = Pescara, n = San Benedetto del Tronto, o = Ancona, p = Pesaro, q = Rimini, r = Ravenna, and s = Chioggia. Numbers 1–9 indicate the biogeographic areas into which the Italian seas are divided, according to the Italian checklist [9].

The samples were collected via Van Veen grab sampling on the soft bottom using an oceanographic vessel. On the board, the sediment was removed with a 1 mm mesh sieve and seawater, and the collected animals were fixed in 4% formaldehyde buffered with calcium carbonate. Subsequently, the sorting activity was carried out at ISPRA laboratories. The collected specimens were preserved in 96% alcohol and identified on a species level using a stereomicroscope and the available bibliography.

The names and classification of the identified species were checked through https://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 7 May 2023) [20], the principal world register of marine species.

The presence of each species in the Italian Seas was verified through the use of the last edition of the Italian checklist [9], whereby the Italian Seas were divided into 9 biogeographical areas: (1) the Ligurian Sea (in the broad sense), the north of Piombino and Capo Corso, belonging to the north-western area of the Mediterranean; (2) the coastline of Sardinia (and Corsica) and the north Tyrrhenian sea from Piombino, including the entire Gulf of Gaeta, belonging to the northern section of the central-western area of the Mediterranean; (3) the whole coastline of Campania, the Tyrrhenian coastline of Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily, as well as most of the southern Sicilian coastline, belonging to the southern section of the central-western area of the Mediterranean; (4) the Strait of Messina (a separate “microsector”, rich in Pliocene Atlantic relicts); (5) the south-eastern tip of Sicily, as well as the Pelagie Islands (and the Maltese archipelago), belonging to the south-eastern section of the Mediterranean; (6) the eastern coast of Sicily (except for the Strait of Messina), the Ionian coastline of Calabria and Basilicata, and the southern part of the Salentina peninsula extending up to Otranto, belonging to the central-eastern area of the Mediterranean; (7) the coastline of Murgia (south of the Gulf of Manfredonia) and Salento, the north of Otranto, belonging to the southern Adriatic section; (8) the coastline from the Gulf of Manfredonia extending up to the Conero promontory, belonging to the mid-Adriatic sector; and (9) the coastline from Conero to Istria, forming the northern Adriatic sector [21].

Sediment features were characterized for each sampling point through a macroscopic description of the sampling process before starting the sorting activities. We defined four sediment categories: sand, mud, detrital, and bottoms with seagrass bed. The sand was the sediment collected that had a percentage of sand greater than 60%; the mud sediment was defined as the percentage of mud that was higher than 60%; the detrital was defined as composed of pebbles with empty shells, fragments of bryozoans, and the remains of calcareous algae, and the last category was represented by seagrass beds.

In addition, the depth at which samples were collected was recorded for each individual survey point.

3. Results

A total of 2098 specimens were collected from 29 species within 5 families: Bodotriidae (T. Scott, 1901); Leuconidae (Sars, 1878); Nannastacidae (Bate, 1866); Diastylidae (Bate, 1856); and Pseudocumatidae (Sars, 1878). Nine species belonging to the Bodotriidae family, seven species belonging to Diastylidae, six species belonging to Leuconidae, six species belonging to Nannastacidae, and one species belonging to Pseudocumatidae were found.

Of all the species collected, seven species were new to the Italian marine waters (Table 1): Cumopsis goodsir (Van Beneden, 1861), found in biogeographical areas 2 and 9; Diastylis doryphora (Fage, 1940), found in biogeographical area 7; Diastylis richardi (Fage, 1929), found in biogeographical area 9; Diastylis tumida (Liljeborg, 1855), found in biogeographical areas 2 and 9; Ekleptostylis walkeri (Calman, 1907), found in biogeographical area 8; Leucon (Leucon) affinis (Fage, 1951), found in biogeographical area 9; and Nannastacus longirostris (G.O. Sars, 1879), found in biogeographical area 2.

Table 1.

Biogeographical distribution of species collected in the 9 areas. The species and their respective biogeographical areas, not present in the Italian checklist, are highlighted in dark gray; the cross highlighted in light gray shows species collected in new biogeographical areas of the Italian checklist.

The largest number of new species collected belonged to the Diastylidae family, while only one species was collected for each of the Bodotriidae, Leuconidaeand, and Nannastacidae families, and no new species was collected among the Pseudocumatidae family.

Most of the new biogeographic records occurred were found in area 2 where 17 species were found, followed by area 9 where 15 new species were found. The most numerous species collected in all surveys were Iphinoe tenella (Sars, 1878) (959 specimens), followed by Leucon (Leucon) mediterraneus (Sars, 1878) (342 specimens), Iphinoe serrata (Norman, 1867) (209 specimens), and Diastylis neapolitana (Sars, 1879) (176 specimens). The least numerous species were Procampylaspis bonnieri (Calman, 1906); Leucon (Macrauloleucon) siphonatus (Calman, 1905); Leucon (Epileucon) longirostris (Sars, 1871); Iphinoe inermis (Sars, 1878); E. walkeri, D. doryphora, and Cumella (Cumella) pygmaea italica (Bacescu, 1950), all found with a single specimen. Table 2 shows the depths where species were found at the 19 sampling sites.

Table 2.

Depths at which the species were collected (in meters) at the 19 sampling sites. a = Livorno, b = Follonica, c = Porto Ercole, d = Montalto di Castro, e = Castel Porziano, f = Nettuno, g = Olbia, h = Punta Tramontana, i = Fiume Santo, j = Bisceglie, k = Bari, l = Vieste, m = Pescara, n = San Benedetto del Tronto, o = Ancona, p = Pesaro, q = Rimini, r = Ravenna, and s = Chioggia.

Ecology

The features of sediment when the species were collected are shown in Table 3, limiting the description of the sediment to four categories (sand, detrital, mud, and bottoms with seagrass beds), as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Table 3.

Sediment patterns where the species were found. Patterns: sand (a), detrital (b), mud (c), and bottoms with seagrass beds (d).

4. Discussion

Of the 29 species, information was provided on biogeographical distribution (according to the Italian checklist), preferred sediment type, and depth distribution.

The data provided can not only be used by insiders who required information on the ecological cumacean preferences, but also to update the Italian Seas checklist and the world database.

The reporting of seven new species not previously included in the Italian checklist underscores the significance of this type of study and highlights the need to increase them.

Regarding the new seven species [9], C. goodsir (three individuals) was collected at 3 m and 15 m depths on the sandy bottom in biogeographical areas 2 and 9. As reported in the literature [22,23], this species is more abundant in the sandy bottom, especially in sediments with a lower organic content. Moreover, in stations where C. goodsir is scarce or absent, the presence of the vicarious species Cumopsis longipes (Dohrn, 1869) is observed. In the Mediterranean Sea, this shift is caused by different hydrodynamic conditions [18,24,25,26]. In our samples, however, we found a low number of individuals, probably due to the high levels of anthropic organic matter in the investigated area; in fact, we recorded the replacement of C. goodsir with C. longipes when the laying of submarine pipeline caused a change in hydrodynamic conditions.

A single specimen of D. doryphore was collected in biogeographical area 7 and at a depth of 147 m. This species was recorded at a depth of 63 m along the French Mediterranean coasts, as previously reported [2], so our data indicate that D. doryphore is also a deep-water species. In the Diastylidae family, six specimens of D. richardi were collected in the northern Adriatic Sea (biogeographical area 9) and were reported for the first time in the Mediterranean Sea on a sandy bottom at a depth of 28 m, and the literature reported that this species lives in the deep sea (4380 m) in the Gulf of Biscay [26]. Two specimens of D. tumida were collected in both the Adriatic Sea (biogeographical area 2) and the Tyrrhenian Sea (biogeographical area 9) at a depth of around 28 m on a sandy bottom, as recorded by [27], while [28] recorded this species at a depth of 750 m in the Gulf of Cadiz. A single specimen of E. walkeri was collected in the Adriatic Sea (biogeographical area 8) at a depth of 56 m on a muddy bottom. The presence of this species was recorded by [26] in the Gulf of Biscay at 100 m, from 63 to 100 m in Banylus and Monaco, and from 100 to 150 m in the Arcachon Bay (Gulf of Biscay). However, no information on sediment features is available in the literature reviewed [28]. We collected two individuals belonging to L. (Leucon) affinis in the northern Adriatic Sea (biogeographical area 9) at a depth of 29 m on the muddy bottom. This species was collected in the same area, but at a depth of 75 m on predominantly muddy sediment [10]; nevertheless, the Italian checklist does not yet report this record. Finally, 20 specimens of N. longirostris were found in Follonica (Tyrrhenian Sea, biogeographical area 2) at a depth of 25 m on muddy sediment, while [28,29] reported this species in a bathymetric range from 5 to 309 m in different areas of the Mediterranean Sea.

These new records, on the one hand, confirmed the information in the literature, and, on the other hand, provided new data on the depth and sediment features in which the species prefer to live. For example, the I. serrata, I. tenella, L. affinis, L. siphonatus, P. bonneri, and Pseudocuma (Pseudocuma) longicorne longicorne (Bate, 1858) species were found to live in shallower waters and not only in deep water, as reported in the reviewed literature [30]. Currently, there are wide gaps in the literature regarding the species’ preferred characteristics sediment. In fact, out of 29 species collected, we only found information for 12 of them. Furthermore, Bodotria pulchella (Sars, 1878) and P. longicorne longicorne are described as species living on the sandy bottom [15,16], but we also found them on muddy and detrital bottoms. I. serrata, according to the literature [12,13,14,15,16], is found on the muddy bottom; nevertheless, we collected it on the sandy bottom. For the remaining species, including C. goodsir, D. neapolitana, Eudorella nana (Sars, 1879), Eocuma ferox (Fischer, 1872), D. doryphora, E. walkeri, L. affinis, L. siphonatus, C. pygmaea italica, N. longirostris, D. richardi, D. tumida, Eudorella truncatula (Bate, 1856), Campylaspis glabra (Sars, 1878), Campylaspis sulcata (Sars, 1870), and P. bonnieri, no literature information on sediment characteristics was available.

New information on cumacean biogeographical distribution was also provided in this study, we observed many new records in four biogeographical areas, while none in others. These differences occurred because the project sites spread mainly in the North Adriatic Sea and the Central Tyrrhenian Sea, and also because the period in which the investigations were carried out was long.

However, it will be interesting to collect more information on species that live in the less investigated areas, especially in order to discover more about rare species on which information is scarce.

The lack of data regarding cumaceans, for the Italian Seas, as well as the difficulties associated with obtaining new information, can be attributed to different causes, including their naturally low abundances compared to other peracarids, such as amphipods, which are harder to sample. Moreover, their small size also makes the morphological identification of this group difficult. This issue can be addressed by combining the classical morphological identification with molecular analysis (e.g., barcoding), allowing one species to be discriminated from another with greater certainty, and allowing possible cryptic species to be discovered. The scarcity of cumacean taxonomists and experts is another predicament; the taxonomist’s profession requires many years of study and practice, and unfortunately the existing reference bibliography used as a credential tool for identification purposes is limited and often outdated.

We hope more studies on minor taxa, such as cumaceans, will be published in order to address this knowledge gap.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.; investigation, V.M., M.T., L.L., B.T. and P.T.; data curation, V.M.; validation, V.M., M.T., L.L., B.T. and P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M., M.T., L.L., B.T. and P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants in sampling and laboratory activities, as well as Danilo Vani, Salvatore Porrello, Tiziano Bacci, Laura Grossi and Fabio Bertasi for their scientific support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jones, N.S. The systematics and distribution of Cumacea from depths exceeding 200 meters. Galathea Rep. 1969, 10, 99–180. [Google Scholar]

- Jaume, D.; Boxshall, G. Global diversity of Cumaceans and Tanaidaceans (Crustacea: Cumacea & Tanaidacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2008, 595, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wieser, W. Factors influencing the choice of substratum in Cumella vulgaris Hart (Crustacea, Cumacea). Limnol. Ocean. 1956, 1, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Fernadez-Arcaya, U.; Tirado, P.; Dutrieux, E.; Corbera, J. Relationships between shallow-water cumacean assemblages and sediment characteristics facing the Iranian coast of the Persian Gulf. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2010, 90, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, J. Orden Cumacea. Rev. IDE@-SEA 2015, 76, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- De la Ossa Carretero, J.A.; Del-Pilar-Ruso, Y.; Giménez-Casalduero, F.; Sánchez-Lizasoet, J.L. Assessing reliable indicators to sewage pollution in coastal soft-bottom communities. Environ. Monit. Assess 2011, 184, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, J.; Cardell, M.J. Cumaceans as indicators of eutrophication on soft bottoms. Sci. Mar. 1995, 59 (Suppl. S1), 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Watling, L.; Gerken, S. World Cumacea Database. 2023. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org/cumacea (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Relini, G. Checklist della flora e della fauna dei mari italiani (Parte II). Biol. Mar. Med. 2010, 17 (Suppl. S1), 484–486. [Google Scholar]

- Strafella, P.; Salvalaggio, V.; Cuicchi, C.; Punzo, E.; Santelli, A.; Colombelli, A.; Fabi, G.; Spagnolo, A. New Geographical Record of Three Cumacean Species Eudorella nana, Leucon affinis, Leucon siphonatus and One Rare Amphipod Presence Confirmation, Stenothoe bosphorana, in Adriatic Sea, Italy. Thalass. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 37, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazziotti, C.; Lezzi, M. The cumacean genus Iphinoe (Crustacea: Peracarida) from Italian waters and I. daphne n. sp. from the northwestern Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean. Zootaxa 2020, 4766, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Ceppodomo, I.; Galli, C.; Sgorbini, S.; Dell’Amico, F.; Morri, C. Benthos dei mari toscani. I: Livorno-Isola d’Elba (crociera ENEA 1985). In Arcipelago Toscano. Studio Oceanografico, Sedimentologico, Geochimico e Biologico; ENEA: Roma, Italy, 1993; pp. 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C.; Ceppodomo, I.; Cocito, S.; Aliani, S.; Dell’Amico, F.; Cattaneo-Vietti, R.; Morri, C. Benthos dei mari toscani. III: La Spezia-Livorno (crociera ENEA 1987). In Arcipelago Toscano. Studio Oceanografico, Sedimentologico, Geochimico e Biologico; ENEA: Roma, Italy, 1993; pp. 317–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C.; Ceppodomo, I.; Niccolai, I.; Aliani, S.; De Ranieri, S.; Abbiati, M.; Dell’Amico, F.; Morri, C. Benthos dei mari toscani. II: Isola d’Elba-Montecristo (crociera ENEA 1986). In Arcipelago Toscano. Studio Oceanografico, Sedimentologico, Geochimico e Biologico; ENEA: Roma, Italy, 1993; pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Chimenz Gusso, C.; Gravina, M.F.; Maggiore, F. Temporal variations in soft bottom benthic communities in central Tyrrhenian sea (Italy). Arch. Ocean. Limnol. 2001, 22, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, J. Recherches qualitatives sur les Biocenoses marines des substrats meubles dragables de la region Marseillaise. Rec. Trav. St. Mar. End. 1965, 52, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Le Loeuff, P.; Intes, A. Les cumaces du plateau continental de Côte D’Ivoire. Cah. ORSTOM Série Océanographie 1972, 10, 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera, J.; San Vicente, C.; Sorbe, J.C. Small-scale distribution, life cycle and secondary production of Cumopsis goodsir in Creixell Beach western Mediterranean. Mar. Biol. Ass. UK 2000, 80, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, J.; Galil, B.S. Cumacean assemblages on the Levantine shelf (Mediterranean Sea)–spatiotemporal trends between 2005 and 2012. Mar. Biol. Res. 2016, 12, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. 2023. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Bianchi, C.N. Proposta di suddivisione dei mari italiani in settori biogeografici. Not. SIBM 2004, 46, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ledoyer, M. Ecologie de la faune vagile des biotopesme Méditerranéens accessibles en scaphandre autonome. Synthese de l’e tude ecologique. Recl. Trav. Stn. Mar. D’Endoume 1968, 44, 125–295. [Google Scholar]

- Masse, H. Quantitative investigations of sand-bottom macrofauna along the Mediterranean north-west coast. Mar. Biol. 1972, 15, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie-Brown, J.A.; Trail, J.W.H.; Clarke, W.E. The Annals of Scottish Natural History; David Douglas: Edinburgh, UK, 1900; Volume 9, pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N.S. British Cumaceans. In Synopses of the British Fauna No. 7; Linnean Society of London Academic Press: London, UK, 1976; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Fage, L. Cumacés. Faune Fr. 1951, 54, 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- Meinert, F.R. Crusatecea malacostraca. In Videnskabelige Udbytte af Kanonbaaden "Hauchs" Togter i de Danske Have Indenfors Skagen i Aarene 1883–86; Høst & Søns Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera, J. Check-list of Cumacea from Iberian waters. Misc. Zool. 1995, 18, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Radhadevi, A.; Kurian, C.V. Report on the international Indian Ocean expedition collections of Cumacea in the Smithsonian Institution Washington. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. India 1980, 22, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Marinello, L.I. Cumacei del Mediterraneo. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rome La Sapienza, Roma, Italy, 1989; p. 557. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).