Abstract

We describe and diagnose a new species of Acanthephyra (Acanthephyridae: Caridea: Decapoda) and provide an amended key to all species of the genus. In order to assess the taxonomic position of the new species, we examined and coded 55 characters in available specimens of Acanthephyra and ran morphological phylogenetic analyses. We also used a COI gene marker for molecular analyses of the new species and other available specimens of Acanthephyra. Both analyses retrieved an unexpected grouping of species that contradicted a recently accepted morphological grouping. We tested a new, quantitative, set of characters and found that three of them may explain the molecular grouping of the genus. These characters are linked to: (1) proportions of the 6th pleonic somite, (2) length of the same against carapace length, and (3) length of the same against length of two preceding somites. We suggest that these characters mirror evolutionary traits in Acanthephyra and discuss their possible adaptive sense.

Keywords:

Decapoda; new species; phylogeny; molecular analyses; morphology; morphological characters 1. Introduction

A diverse pelagic family, Acanthephyridae includes seven accepted genera: Acanthephyra A. Milne-Edwards, 1881, Ephyrina Smith, 1885, Heterogenys Chace, 1986, Hymenodora G.O. Sars, 1877, Kemphyra Chace, 1986, Meningodora S.I. Smith, 1882, and Notostomus A. Milne-Edwards, 1881. Acanthephyra is the most speciose genus that is widely distributed, playing a significant role in tropical/subtropical meso- and bathypelagic communities [1,2]. Among 27 currently accepted species [3], two-thirds were described in the 19th century. The most “junior” species, Acanthephyra brevicarinata, was described nearly forty years ago [4] and, until recently, the species composition of the genus was ostensibly considered as ‘set in stone’.

However, zoological museums still host undescribed or misidentified species that may trigger a new mindset about invertebrate taxonomy. In this aspect, reexamination of museum collections may compete with the deep sea sampling that also yields such taxa (e.g., [5]). Indeed, while examining a collection of Acanthephyridae of the Royal British Columbia Museum, we found three specimens identified as Acanthephyra curtirostris. A detailed examination showed that the new species, although resembling A. curtirostris in a general appearance, is morphologically distant from this as well as from all known species of Acanthephyra. Moreover, COI molecular analyses confirmed a species level divergence of the new species and, surprisingly, its phylogenetic relation to morphologically distant species of Acanthephyra. These results inferred the accepted grouping based on qualitative morphological characters by Kemp [6] and Chace [7] and called for a new mindset on a taxonomic composition of Acanthephyra. Taking this challenge, we analyzed an additional set of quantitative characters in Acanthephyra (not used in previous analyses) and compared results with the COI phylogenetic tree.

Here, we present results of our morphological, statistical, and phylogenetic analyses and suggest new quantitative characters that provide clustering of Acanthephyra into the same species groups as those retrieved by the molecular analyses. We also diagnose and describe the new species and provide a key for identification of all Acanthephyra.

2. Methods

2.1. Morphological Analyses

Acanthephyra belongs to the family Acanthephyridae, which is sister to Oplophoridae [8]. We chose as the outgroups representatives of Oplophoridae (Systellaspis debilis (A. Milne-Edwards, 1881): Analysis 1) and Acanthephyridae (Meningodora mollis Smith, 1882: Analysis 2). We included as the ingroups all valid species of Acanthephyra and the new species (Appendix A Table A1). We did not include a single species, A. rostrata, that is known only from three specimens "in an extremely bad state of preservation" [9], which suggests that “the species may remain enigmatic indefinitely” [7]; most diagnostic characters of this species are missing. Another accepted species, A. sica, is considered here as a southern subspecies of A. pelagica and defined as A. pelagica sica. Although the species status of A. sica Bate, 1888 has been restored by Burukovsky and Romensky [10] for the southern form of A. pelagica, we follow a later classical paper by Chace [7] in which both species have been considered as synonyms. According to Burukovsky and Romensky [10], both taxa may differ only in a dorsal midline of the carapace that is more “distinctly and extensively” carinate in A. pelagica sica than in A. pelagica, which is very subjective. Since A. pelagica and A. pelagica sica are geographically isolated, we considered both as separate clades in statistical and molecular analyses but did not include A. pelagica sica in key to species.

For each of the included 29 taxa, we identified and encoded 55 morphological characters (not weighted, Appendix A Table A2). The dataset (Appendix A Table A3) was handled and analyzed using a combination of programs using maximum parsimony settings: WINCLADA/NONA and TNT [11,12]. Trees were generated in TNT with 30,000 trees in memory, under the ‘traditional search’ (branch-and-bound) algorithms. Relative stability of clades was assessed by standard bootstrapping (sample with replacement) with 10,000 pseudoreplicates and by Bremer support (algorithm TBR, saving up to 10,000 trees up to 12 steps longer). In all analyses, clades were considered robust if they had synchronous Bremer support ≥3 and bootstrap support ≥70.

2.2. Molecular Analyses

COI sequences of three specimens of the new species were available at the Centre for Genomics of Biodiversity and deposited in the BOLD database (DSCRA045-06, DSCRA046-06, DSCRA047-06). As only this marker was sequenced, we used the same across Acanthephyra in order to assess a taxonomic position of the new species. The COI marker alone cannot resolve phylogenetic relationships within Acanthephyridae but may help in a retrieval of closely related species. We took data on representatives of all species of the genus submitted to GenBank and BOLD databases: 17 species in total (Table 1).

Table 1.

Individuals used in molecular analyses with localities, voucher numbers, and GenBank accession numbers or BOLD IDs for COI sequences.

Four species (A. kingsleyi, A. prionota, A. tenuipes and A. pelagica sica) were not sequenced before but present in our collections. We extracted total genomic DNA from the fourth and fifth pleopods of these species using the Qiagen DNeasy® Blood and Tissue Kit, in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the COI gene was run with the primers COL6/COH6 [15,16]. A pre-made PCR mix (ScreenMix-HS) from Evrogene™ (1× ScreenMix-HS, 0.4 μM of each primer, 1 μL of DNA template, and completed with milliQ H2O to make up a total volume of 20 μL) was used for the amplification. The thermal profile used an initial denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C followed by 38 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 48 °C, 1 min at 72°, and a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified by ethanol precipitation and sequenced in both directions using BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems). Each sequencing reaction mixture, including 0.5 μL of BigDye Terminator v3.1, 0.8 μL of 1 μM primer, and 1–2 μL of purified PCR template, was run for 30 cycles of 96 °C (10 s), 50 °C (5 s), and 60 °C (4 min). Sequences were purified by ethanol precipitation to remove unincorporated primers and dyes. Products were re-suspended in 14 μL formamide and electrophoresed in ABI Prism-3500 sequencer (Applied Biosystems) at the joint usage center ‘Methods of molecular diagnostics’ of the IEE RAS. The nucleotide sequences were cleaned and assembled using CodonCode Aligner version 7.1.1. All sequences were checked for a stop-codon presence using TranslatorX [17]. The new COI sequences were submitted to the NCBI GenBank database.

Resulting alignment for phylogenetic analyses included 26 sequences, trimmed to 650 bp. We chose Ephyrina benedicti (GenBank: MW043002), Notostomus elegans (MW043011), and Meningodora mollis (KP076192) as outgroups. The PartitionFinder2 [18] was used to find the best nucleotide substitution models for three partitions by codon. The resulting partitioning schemes and substitution models were used in Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference analyses. Maximum Likelihood analysis was run in RAxML [19] with 1000 thorough bootstrap replicates. MrBayes 3.2 [20] was used for Bayesian inference (posterior probability, chain length 10,000,000, G = 4, 3 heated and 1 cold chains, subsampling frequency 1000, 2 independent runs, first 25% of samples were discarded, 1% average standard deviation of split frequencies was reached after approximately 0.7 million generations). We considered the clades statistically supported if they had a synchronous support of posterior probabilities ≥ 0.95 on the BI tree and bootstrap value ≥ 70% on the ML tree.

In order to estimate the COI evolutionary divergence between species, we implemented the Kimura 2-parameter model [21] in MEGA X [22].

2.3. Statistical Analyses

We examined representatives of 17 species in order to enrich the dataset; wherever possible we included additional specimens of the same species. We measured the postorbital carapace length; the length of the 4th, 5th, and 6th pleonic somites along the dorsal line; and the height of the 6th pleonic somite at the posterior end. On the basis of these measurements, we calculated eight qualitative characters (Table 2):

Table 2.

Proportions and relative length of posterior pleonic segments in species groups of Acanthephyra and their detection rate in our dataset.

- -

- Proportions of the 6th pleonic somite (P6): the ratio length to height;

- -

- Relative length of the 4th pleonic somite (L4): the ratio length of this somite to carapace length;

- -

- Relative length of the 5th pleonic somite (L5): the ratio length of this somite to carapace length;

- -

- Relative length of the 6th pleonic somite (L6): the ratio length of this somite to carapace length;

- -

- The ratio length of the 4th somite to length of the 5th somite (R4/5);

- -

- The ratio length of the 4th somite to length of the 6th somite (R4/6);

- -

- The ratio length of the 5th somite to length of the 6th somite (R5/6);

- -

- The ratio length of the 4th plus 5th somite to length of the 6th somite (R4 + 5/6).

All specimens were divided into five groups in accordance with the results of molecular analyses. Then, we ran generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with species group as a target and the eight parameters above as fixed factors. We also used multinomial logistic regression (MLR) models and included the intercept.

The GLMMs showed a detection rate (attribution of species to the proper group retrieved via morphological and molecular analysis) of qualitative characters within our dataset. We further assessed the generalization ability of MLR models, i.e., ability to correctly classify new taxa not used here for the model construction. The original datasets were semi-randomly split into train and test subsets consisting of 80% and 20% of the original data. Splitting was done with respect to the group sizes, i.e., each group of the original dataset contributed 80% of its data into the train subset. In most cases, exactly 20% of the number of specimen in a group resulted in a non-integer number that was rounded to the nearest integer exceeding that value (e.g., for groups consisting of two specimens one was used for the test subset, and for groups of nine specimens two were used for test subsets). The remaining observations were included into the train subset. The MLR coefficients were computed for the z-score normalized train data and the detection rates were estimated for the test data (previously unseen by the model) normalized likewise but with the use of the mean and the standard deviation of the train subset.

Finally, we assessed the relative detection power of each character and computed standardized mean difference (difference of means of two subset distributions divided by the standard deviation of the whole set) of detection rate distributions for character subsets that contain a particular character and character subsets that do not contain the same character. This quantity provides a suggestion of which particular character should be included in a dataset for every number of characters in use. Distributions of obtained detection rates provided a more statistically supported identification of characters and character sets, providing the best attribution of species to species groups.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Analyses

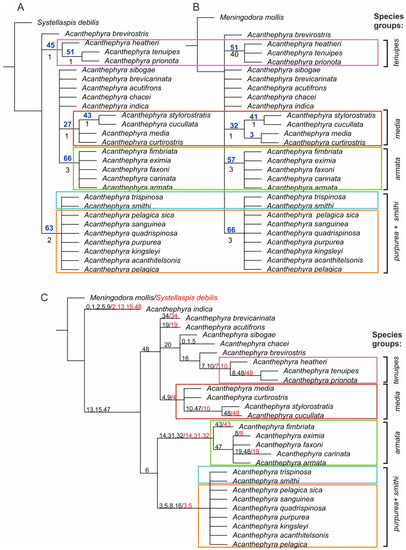

Analysis 1 with Systellaspis debilis as the outgroup retrieved 65 of the most parsimonious (MP) trees (Figure 1A), with a score of 66 (Ci = 83, Ri = 90). None of the clades received statistical support (synchronous Bremer and bootstrap); a single clade “A. armata” gained Bremer support 3. We retrieved four species complexes: “A. armata” (A. armata, A. carinata, A. eximia, A. faxoni, A. fimbriata), “A. media” (A. cucculata, A. curtirostris, A. stylorostratis, A. media), “A. purpurea + A. smithi” (A. acanthytelsonis, A. kingsley, A. pelagica, A. pelagica sica, A. purpurea, A. quadrispinosa, A. sanguinea, A. smithi, A. trispinosa), and “A. tenuipes” (A. prionota, A. tenuipes, A. heatheri sp. nov. (in text and figures)). All other species of Acanthephyra were not grouped.

Figure 1.

Morphological trees: (A)—Systellaspis debilis as outgroup; (B)—Meningodora mollis as outgroup; all Bremer support (black, below branches) and bootstrap values (blue, above branches) are shown; (C)—synapomorphies for Analysis 1 (red) and Analysis 2 (black) above branches, see coding in Appendix A Table A2.

Analysis 2 with Meningodora mollis as the outgroup retrieved 7 of the most parsimonious (MP) trees (Figure 1B), with a score of 51 (Ci = 107, Ri = 103). None of clades received statistical support (synchronous Bremer and bootstrap); the clades “A. armata” and “A. purpurea + smithi” gained Bremer support 3. We retrieved same four species complexes as in Analysis 1, all other species were not grouped.

3.2. Molecular Analyses

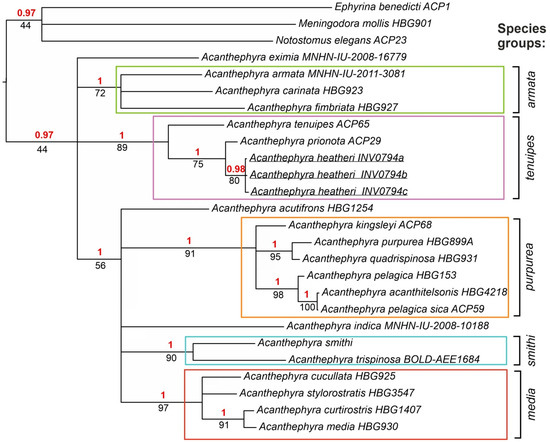

ML and BI molecular trees (Figure 2) were similar to morphological trees but differed in three significant aspects:

Figure 2.

Molecular BI and ML tree, only supported clades are shown. The horizontal scale bar marks the number of expected substitutions per site. Statistical support indicated as Bayesian posterior probabilities (red, above branches) and ML bootstrap with 1000 replicates (black, below branches).

- The clades “A. purpurea” and “A. smithi” were separate, which resulted in a retrieval of five species complexes (“A. purpurea” and “A. smithi” were merged on the morphological trees, four species complexes retrieved);

- Acanthephyra eximia was not nested in the clade “A. armata” (nested on the morphological trees);

- All five species complexes (“A. armata”, “A. purpurea”, “A. smithi”, “A. media”, and “A. tenuipes”) gained statistical support.

The new species was nested in the “A. tenuipes” clade that was robust.

COI distances between the Acanthephyra species ranged from 0.2% to 25.7% (Table 3). Within the supported clades this distances ranged between 0.2–17.6%. The species A. prionota was the most phylogenetically similar to the new species, with a difference of 3.7%.

Table 3.

Estimates of evolutionary divergence between species of the genus Acanthephyra (% of base substitutions between species). Analyses were run using the Kimura 2-parameter model (Kimura, 1980) in MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018); a total of 650 positions in the analyzed dataset.

3.3. Statistical Analyses

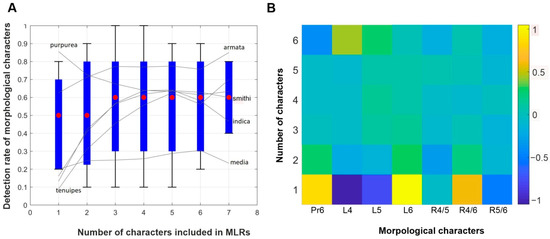

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) revealed three quantitative characters providing the best detection rate within our dataset (Table 2): proportions of the 6th pleonic somite (85%) relative length of the 6th pleonic somite (68%), and the ratio length of the 4th plus 5th somite to length of the 6th somite (100%).

The generalization ability of MLR models for new taxa not included in the dataset increased along with an addition of quantitative parameters (Figure 3A). Three characters provided a mean detection rate of 60% (red dots) that did not grow when we added new characters. Among species groups, the “A. armata” group was the best detected (75–85% with 3–7 characters included), whereas the “A. media” group showed the lowest detection rate (20–30% with 1–7 characters included). The rest was characterized by an intermediate detection rate (55–65% with 4–6 characters included).

Figure 3.

Results of multinomial logistic regression (MLR) models (A)—generalization ability of MLRs models (ability to classify new specimens); red dots—medians, blue boxes—95% confidence intervals with all observed detection ranges indicated as solid whiskers; grey lines—average detection rates of individual species groups. (B)—relative detection power heatmap of individual morphological characters (axis OX, see coding of characters in Table 2) vs. number of characters included in random sets (in addition to individual characters, axis OY). The yellow square (lower row, L6) indicates maximal detection power, the violet square (lower row, L4) indicates minimal detection power. The relative detection power is defined as a standardized mean difference (difference of means of two subset distributions divided by the standard deviation of the whole set) of detection rate distributions for character subsets that contain a particular character and character subsets that do not contain the same character.

The highest relative detection power for new taxa not included in the dataset was shown by the relative length of the 6th pleonic somite when used alone (Figure 3B); the absolute detection rate in this case was 57%. The highest absolute detection rate (67%) was observed when we used a combination of three characters: relative length of the 4th, 5th, and 6th pleonic somites.

4. Discussion

4.1. Taxonomic Implication

Results of molecular analyses suggested five robust species groups. Since a single COI gene marker does allow comprehensive phylogenetic reconstruction, we leave diagnosing of the groups for future studies based upon a greater number of gene markers. Molecular trees, however, indicate a close relation between species, which is also mirrored in morphological trees. Revealed species groups are supported by distinct synapomorphies (Figure 1C). The new species is nested within the “A. tenuipes” group that, along with four other groups, composes the main diversity of Acanthephyra. Below we describe the new species and, keeping a conservative approach, do not designate the species groups but organize the key to species in accordance with them.

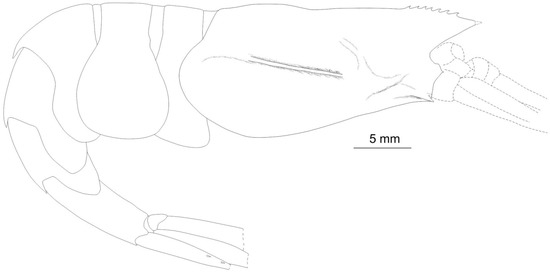

Figure 4.

Acanthephyra heatheri sp. nov., ARBCM 007-00020-010, holotype, female. Lateral view. Missed parts (dotted lines) reconstructed using the paratypes.

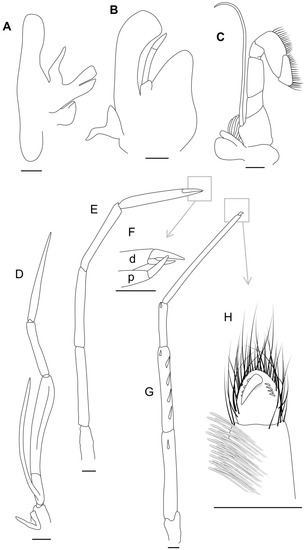

Figure 5.

Acanthephyra heatheri sp. nov., ARBCM 007-00020-010, holotype, female. (A)—second left maxilla; (B)—first left maxilliped; (C)—second left maxilliped; (D)—third right maxilliped; (E,F)—second right pereopod and its tip; (G,H)—fifth right pereopod and its tip; d—dactylus, p—propodus. Scales: 1 mm.

Material examined: Holotype, female, 26 mm carapace length, 80 mm total length (telson broken); paratypes, two females 23 mm and 29 mm carapace length. Canada, British Columbia, West of Cape Scott, 50°35′14″ N; 130°05′27″ W–50°35′51″ N; 130°04′36″ W, 08.10.2006, bottom trawl, 2125–2150 m. All three specimens derive from the Royal British Columbia Museum collection and have a common number 25-6-10-4(b) 007-00020-010.

Diagnosis: Integument thin but not membranous; rostrum nearly ¼ as long as carapace, not reaching level of distal end of antennular peduncle and antennal scale, with seven dorsal teeth, ventral margin oblique, unarmed; carapace with dorsal margin carinate over anterior half, sinuous, not interrupted by cervical groove, branchiostegal carina short and sharp, ½ as long as rostrum, suprabranchial carina nearly straight. Pleon dorsally carinate on four posterior somites only; four posterior somites with posteromesial teeth, tooth on 3rd somite reaching ¼ of 4th somite, 6th somite twice as long as posterior height; telson flattened in dorsal midline.

Description: Carapace 1.6 times as long as wide, smooth, prominent suprabranchial carina 0.4 time as long as carapace. Pleonic somites measured along dorsal side are 0.18, 0.24, 0.38, 0.32, 0.32, and 0.49 of postorbital carapace length, respectively. Sixth pleonic somite 2.11 times as long as posterior height.

Second maxilla with distal part of exopod 3.2 times as long as wide, endopod 2.9 times as long as wide, distal and proximal endites subrectangular and subtriangular, respectively; first maxilliped with distal part of exopod 2.4 times as long as wide, endopod 3-segmented, distal segment 0.6 times as long as penultimate segment; second maxilliped with terminal segment subtriangular, attached transversely, 2.1 times as long as wide; third maxilliped with three terminal segments with length ratio (from proximal to distal) 4:2:3.

Pereopods 1, 3, and 4 are missing. Second pereopod with ischium, merus and carpus unarmed, chela with one distal spine on propodus and two unequal distal spines on dactyl; fifth pereopod with ischium, merus, and carpus bearing a single distal spine each, merus with a row of four additional spines, dactyl with a terminal hook-like spine and two rows of spinules.

Remarks: The new species ostensibly resembles A. curtirostris, which has resulted in a misidentification of the specimens that we found in the Royal British Columbia Museum collection. However, both species are distant on the molecular tree and differ in quantitative characters. In addition, Acanthephyra heatheri differs from A. curtirostris in (1) the absence of ventral teeth on the rostrum (1–2 in A. curtirostris), (2) a very short branchiostegal carina (nearly half of carapace length in A. curtirostris), (3) a well-marked suprabranchial carina (inconspicuous in A. curtirostris), and (4) the absence of a dorsal carina on the second pleonic segment (definite and sharp in A. curtirostris).

Molecular trees suggest a common clade “A. tenuipes” including A. prionota, A. tenuipes, and A. heatheri. Being different in many morphological characters, these three species have two unique characters: (1) a branchiostegal spine set posterior of the anterior margin of the carapace (on the anterior margin of the carapace in the rest of Acanthephyra) and (2) the length ratio fourth to six somite: 0.67–0.69 (<0.66 or >0.70 in other examined Acanthephyra).

The new species differs from A. prionota and A. tenuipes in having (1) a sharp (although short) branchiostegal carina and (2) the presence of a posterior row of spines on the merus of the fifth pereopod. In addition, the new species is greatly bigger (carapace length of the adults of A. heatheri > 20 mm vs < 15 mm in A. prionota and A. tenuipes).

Geographic distribution: Canada, British Columbia, West of Cape Scott.

Vertical distribution: Lower bathypelagic, 2125–2150 m.

Etymology: Named after Dr. Heather D. Bracken-Grissom who significantly contributed to the molecular phylogeny of marine invertebrates and, in particular, Acanthephyridae.

Key to species of Acanthephyra

We do not include A. rostrata (Bate, 1888) known only from three specimens “in an extremely bad state of preservation” [9], which suggests that “the species may remain enigmatic indefinitely” [7]. Most diagnostic characters of this species are missing.

| 1. Rostrum with numerous dorsal teeth, all set anterior to hind margin of orbit | 2 |

| - Dorsal teeth if present, are partly set posterior to hind margin of orbit | 9 |

| 2. Sixth pleonic somite < 1.8 times as long as posterior height; telson with 3 pairs of dorsolateral spines | (“A. trispnosa” group) 3 |

| - Sixth pleonic somite > 1.9 times as long as posterior height; telson with 4–19 pairs of dorsolateral spines | (“A. purpurea” group) 4 |

| 3. Pleon with posteromedian tooth of 3rd somite much larger than that of 4th | A. trispinosa Kemp, 1939 |

| - Pleon with posteromedian tooth of 3rd somite similar that of 4th | A. smithi |

| 4. Carapace with short, sharp carina supporting branchiostegal spine | 5 |

| - Carapace with branchiostegal spine supported, if at all, by rounded ridge | 8 |

| 5. Telson armed with 4 pairs of dorsolateral spines | 6 |

| - Telson armed with 7–19 pairs of dorsolateral spines | 7 |

| 6. Pleon with posteromedian tooth on 4th somite | A. quadrispinosa |

| - Pleon without posteromedian tooth on 4th somite | A. purpurea |

| 7. Telson with 7–11 pairs of dorsolateral spines | A. pelagica |

| - Telson with 13–19 pairs of dorsolateral spines | A. acanthitelsonis |

| 8. Pleon with posteromedian tooth on 4th and 5th somites; telson with 4 pairs of dorsolateral spines | A. sanguinea |

| - Pleon without posteromedian tooth on 4th and 5th somites; telson with 5–6 pairs of dorsolateral spines | A. kingsleyi |

| 9. Telson dorsally convex in anterior part | (“A. armata” group) 10 |

| - Telson dorsally flattened or sulcate | 14 |

| 10. Carapace dorsally sinuous in lateral aspect; 1st pleonic somite without carina | 11 |

| - Carapace regularly convex in lateral aspect; 1st pleonic somite carinate | 12 |

| 11. Branchiostegal carina present | A. faxoni |

| - Branchiostegal carina absent | A. eximia |

| 12. Carapace carinate throughout length of dorsal midline | A. carinata |

| - Carapace without prominent carina on at least posterior 1/3 of dorsal midline | 13 |

| 13. Branchiostegal carina short, ~1/10 of carapace length | A. armata |

| - Branchiostegal carina long, ~1/3 of carapace length | A. fimbriata |

| 14. Anterior margin of rostrum nearly vertical (angle between ventral margin and horizontal axis> 50°) | (“A. media” group) 15 |

| - Anterior margin of rostrum oblique (angle between ventral margin and horizontal axis ≤ 45°) | 18 |

| 15. Carapace with distinct postorbital carina in the posterior half | 16 |

| - No distinct postorbital carina on carapace | 17 |

| 16. Acuminate tip of rostrum horizontal; telson with 4 pairs of dorsolateral spines | A. cucullata |

| - Acuminate tip of rostrum directed anteroventrally; telson with 3 pairs of dorsolateral spines | A. stylorostratis |

| 17. Rostrum < ½ as long as carapace, armed with dorsal 6–10 teeth | A. curtirostris |

| - Rostrum > ¾ as long as carapace, armed with 11–13 dorsal teeth | A. media |

| 18. Carapace with postorbital carina from near orbit nearly to posterior margin | A. indica |

| - Postorbital carina from near orbit nearly to posterior margin of carapace absent | 19 |

| 19. Carapace with conspicuous suprabranchial carina developed in the posterior half; branchiostegal spine set posterior of anterior margin of carapace | (“A. tenuipes” group) 20 |

| - No conspicuous suprabranchial carina developed in the posterior half of carapace; branchiostegal spine set on anterior margin of carapace | 22 |

| 20. Sharp (short) branchiostegal carina on carapace present | A. heatherisp.n. |

| - No sharp branchiostegal carina on carapace | 21 |

| 21. No carina on dorsal midline of 2nd pleonic somite; posterodorsal tooth on 3rd somite low and offset to left | A. tenuipes |

| - Dorsal midline of 2nd pleonic somite carinate, posterodorsal tooth on 3rd somite high and not offset to either side | A. prionota |

| 22. Rostral teeth (5–9) subuliform, distanced from each other | A. chacei |

| - Rostral teeth typical, saw-like | 23 |

| 23. Posteromedian tooth on 3rd pleonic somite fleshy and overreaching 4th somite | A. brevirostris |

| - Posteromedian tooth on 3rd pleonic somite not fleshy, not overreaching 4th somite | 24 |

| 24. No carina on dorsal midline of 2nd pleonic somite | A. sibogae |

| - Dorsal midline of 2nd pleonic somite carinate | 25 |

| 25. No carina on dorsal midline of 1st pleonic somite; telson with 9–13 dorsolateral spines | A. brevicarinata |

| - Dorsal midline of 1st pleonic somite carinate; telson with 5–6 dorsolateral spines | A. acutifrons |

4.2. A New Approach to Taxonomy of Acanthephyra

Morphological phylogenetic analyses based on traditional qualitative morphological characters do not result in a retrieval of resolved trees; the revealed clades are weakly supported and not in a perfect accordance with the molecular clades of Acanthephyra (compare Figure 1 and Figure 2). On the other hand, molecular data result in supported clades that are not in accordance with the accepted taxonomy of Acanthephyra. For example, Kemp [6] and later Chace [7] proposed an “A. purpurea” species group. This group encompassed morphologically similar species and was diagnosed on the basis of sound qualitative characters: (1) the long rostrum, reaching almost to or beyond the end of the antennal scale, with teeth along the whole length of the upper margin and with three or more teeth below; (2) the carapace without a dorsal carina in the posterior half and without lateral carinae except a short branchiostegal carina; (3) the pleon dorsally carinate on 2nd to 6th somites; (4) the telson dorsally sulcate at the proximal end, with three or more pairs of the dorsolateral spines; and (5) the cornea wider than the eyestalk. Molecular analyses, however, proved that this group of similar species is not monophyletic and encompasses the “A. purpurea” (A. acanthytelsonis, A. quadrispinosa, A. kingsley, A. pelagica, A. purpurea, and A. sanguinea) and the “A. smithi” (A. smithi and A. trispinosa) groups. Traditionally accepted qualitative characters fail to separate “A. purpurea” and “A. smithi”, whereas the tested quantitative parameters easily separate both groups. In fact:

- Proportions of the 6th pleonic somite is 1.51–1.72 in “A. smithi” and 1.93–2.65 in “A. purpurea”;

- The ratio length of the 4th somite to length of the 6th somite is 0.88–0.92 in “A. smithi” and 0.61–0.85 in “A. purpurea”;

- The ratio length of the 4th plus 5th somite to length of the 6th somite is 1.59–1.71 in “A. smithi” and 1.22–1.58 in “A. purpurea”.

Yet conversely, ostensibly distant species of the “A. tenuipes” group (A. prionota, A. tenuipes, and A. heatheri sp.n.) share the length ratio fourth to sixth somite (see remarks to the new species above) that separates them from the rest of Acanthephyra.

On a broader scale, quantitative characters satisfactorily explain the grouping of Acanthephyra retrieved via molecular analyses. GLMMs provide a high detection rate when we classify our dataset using even a single parameter: 85% when we use the proportions of the 6th pleonic somite and even 100% when we use the ratio length of the 4th plus 5th somite to the length of the 6th somite. Moreover, MLR models suggest the possibility to classify new, currently unknown species not included in our dataset. Detection rates 57% (when we use only relative length of the 6th pleonic somite) or 67% (when we use a combination of relative lengths of the 4th, 5th, and 6th somites) may ostensibly look insufficient. However, taking into account five tested groups (chance of accidentally correct grouping is 20%), we conclude that the detection rate based on the proposed quantitative characters is quite remarkable.

Quantitative characters distinguishing species groups, i.e., monophyletic clades retrieved via molecular analyses may be considered as synapomorphies. Statistical analyses showed that these synapomorphies are linked either to the proportions of the 6th pleonic somite or the length ratio between this somite and two preceding somites. The adaptive sense of these synapomorphies may be linked to an active defense, i.e., escape function. Indeed, the elongated 6th pleonic segment may provide more efficient backward flips as reported for Oplophoridae [23] and Benthesicymidae [24,25,26]. As the posterior pleonic somites serve as an engine, proportions between the somites may significantly drive efficiency and trajectory of the backward flips whereas proportions of the sixth segment (and the telson with a tail fan) may provide different types of rudder control in Acanthephyra (as in other Acanthephyridae: [14]).

Overall, the proportions of the posterior pleonic somites, similar within species groups and differing across the groups, may mirror different escape strategies of Acanthephyra. Once evolved, these proportions remain only slightly variable within the clades. Results of our analyses unveil a hidden side of decapod evolution in the pelagic realm and draw attention to complementarity of qualitative and quantitative characters in the evolution.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this paper is a description of a new species and an assessment of its place in the taxonomy of the genus (using morpho- and a single gene marker analysis). Even at this stage we found that phylogenetic relations within Acanthephyra do not thoroughly comply with the accepted taxonomy. For example, A. pelagica sica (a subspecies of A. pelagica) was more similar on the molecular tree to A. acanthitelsonis than to A. pelagica. Furthermore, COI of A. pelagica sica and A. acanthitelsonis were almost identical (a single-nucleotide difference), which cannot be explained by a misidentification of specimens: A. acanthitelsonis (Genbank data) was collected in the Gulf of Mexico that is greatly distant from the Southern Atlantic (the geographic range of A. pelagica sica). The problems of this sort merit disentangling via future comprehensive phylogenetic analyses based on all representatives of the genus and more numerous gene markers.

Author Contributions

A.L. analyzed specimens morphologically; D.K. ran genetic analyses; A.V., A.L. and D.K. wrote the paper and participated in its revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by RSF Project No. 22-14-00187.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article or Appendix A.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Henry Choong and Heidi Gartner (Royal BC Museum, Victoria) for providing us with specimens of Acanthephyra from the museum collection. We are also grateful to Jørgen Olesen and Laure Corbari for a chance to examine best crustacean collections of the world and a permanent help during our studies. We thank A.V. Shatravin for his help in running MLR models.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Individuals used in morphological analyses. MNHN—National Museum of Natural History (Paris, France); NMNH—National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., United States; ZMUK—National History Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark; IO RAN—Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences.

Table A1.

Individuals used in morphological analyses. MNHN—National Museum of Natural History (Paris, France); NMNH—National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., United States; ZMUK—National History Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark; IO RAN—Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences.

| Species | Coordinates | Other Information | Museum, Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthephyra acanthitelsonis | 1°30′ N, 10°10′ W | Atlantide-Expedition West Africa 1945–1946. St. 139, 02.05.1946, S200, 4:00. | ZMUK |

| Acanthephyra acanthytelsonis | 10°47′ N, 41°01′ W | Atlantic ocean, RV “Akademik Sergey Vavilov”, 21.10.2016, St. 2647, 800–1500 m, 20:00 | IO RAN |

| Acanthephyra acutifrons | 14°43′ N; 45°02′ W | “Professor Logatchev” 39 cruise St 215 RT, RTAK | IO RAN 39L 215 RT № 1 |

| Acanthephyra acutifrons | 8°53′ S, 159°23′ E | Oceanie, Salomon, New Georgia sound, SALOMONBOA 3, N.O. “Alis”, CP2783, prof. 1501–1545 m. 13.09.2007 | MNHN-IU-2016-9247 |

| Acanthephyra armata | 06°56′ N, 52°35′ W | N.O. “Hermano Gines” GUYANE 2014 Stn CP4405 555–597 m, MNHN-convention APA-973-1, 09.08.2014 | MNHN-IU-2013-2686 |

| Acanthephyra armata | 06°36′ N, 52°35′ W | N.O. “Hermano Gines” GUYANE 2014 Stn CP4405 555–597 m, MNHN-convention APA-973-1, 09.08.2014 | MNHN-IU-2016-9263 |

| Acanthephyra armata | 06°36′ N, 52°35′ W | N.O. “Hermano Gines” GUYANE 2014 Stn CP4405 555–597 m, MNHN-convention APA-973-1, 09.08.2014 | MNHN-IU-2016-9261 |

| Acanthephyra brevicarinata | No data | TALuD St.84 A | MNHN-IU-2018-1563 |

| Acanthephyra carinata | 05°27′ S, 145°56′ E | Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinee: Astrolabe Bay, N.O. “Alis”, BIOPAPUA. Stn CP3717, 850–945 m. 06.10.2010 | MNHN-IU-2016-9274 |

| Acanthephyra chacei | No data | Africana R/V, Cruise 060, St. A7018. 11.03.1988. South Atlantic Ocean | USNM 1113152 |

| Acanthephyra cucculata | 16° 04′ N; 46°41′ W | 39 cruise RV “Logatchev”, 14-15.03.2018, 1500–0 m | IO RAN 39L233RT № 65 |

| Acanthephyra curtirostris | 35°37′96″ E, 21°36′54″ S | Afrique, Mozambique, Canal du Mosambique, Indien, Mainbasa, “Vizconde de Eza”, CP3147. Chalut a perche, prof. 990–996 m, 12.04.2009 | MNHN-IU-2016-9280 (MNHN-Na-17146) |

| Acanthephyra curtirostris | 14°43′ N; 45°02′ W | 39 cruise RV “Logatchev” | IO RAN39L215RT, № 1 |

| Acanthephyra faxoni | 17°05′ S, 072°16′ W | SNP-1, Pacific ocean, Peru, off Southern coast. 1000 m, Jan 1972 | USNM 170562 |

| Acanthephyra faxoni | 8°11′ N, 79°03′ E | N.O. “Marion Dufresne “ SAFARI II, St.04 CP06, 1035 m | MNHN-IU-2018-1564 |

| Acanthephyra faxoni | 25°35′ S, 44°15′ E | SUD MADAGASCAR: Sud Pointe Barrow, Chalutier “Nosy Bell” stn CP 3595 821–910 m, Expedition ATIMO VATAE. 12.05.2010 | MNHN-IU-2016-9209 |

| Acanthephyra faxoni | No data | No data | MNHN-IU-2016-11791 |

| Acanthephyra fimbriata | 12°09′ N, 122°14′ E | MUSORSTOM 3, Phillipines. St. CP 136, 1404 m | MNHN-IU-2018-1565 |

| Acanthephyra heatheri | 50°35.14′ N; 130°05′ W | Canada, British Columbia, West of Cape Scott. 08.10.2006, 2125–2150 m. | RBCM 25-6-10-4(b) 007-00020-010 |

| Acanthephyra heatheri | 50°35.14′ N; 130°05′ W | Canada, British Columbia, West of Cape Scott. 08.10.2006, 2125–2150 m. | RBCM 25-6-10-4(b) 007-00020-010 |

| Acanthephyra heatheri | 50°35.14′ N; 130°05′ W | Canada, British Columbia, West of Cape Scott. 08.10.2006, 2125–2150 m. | RBCM 25-6-10-4(b) 007-00020-010 |

| Acanthephyra indica | 8°11′ N, 79°03′ E | N.O. “Marion Dufresne” SAFARI II, St.04 CP06, 1035 m | MNHN-IU-2018-1566 |

| Acanthephyra indica | 12°57′ S, 48°03′ E | Campagne MIRIKY Madagascar, “Miriky”, entre Nosy-be et Banc du Leven, Stn CP3219, 01.07.09, 906–918 m. | MNHN-IU-2009-1905 |

| Acanthephyra indica | 21°36′54″ S, 35°57′96″ E | Afrique, Mozambique, Canal du Mozambique, Indien. Mainbaza, N.O. “Vizconde de Eza”, Campagne Mainbaza. Stn. CP3147, 990–996 m. 12.04.2009. | MNHN-IU-2008-10188 |

| Acanthephyra kingsley | 10°49′ N, 41°00.5′ W | Atlantic ocean, RV”Akademik Sergey Vavilov”, 21.10.2016, St.2645, 200–800 m, 12:10 | |

| Acanthephyra media | 13°05′ N, 122°25′ E | MUSORSTOM 2, Phillipines. St. CP 42, 1580–1610 m | MNHN-IU-2018-1567 |

| Acanthephyra pelagica | 36°45′ N, 0°16′ E | DANA 1920–1922. St. 1128(1). S 200. 01.10.1921, 21.50. | ZMUK |

| Acanthephyra pelagica | 41°42′ N, 49°53′ W | Atlantic ocean, RV “AMK”, cruise 46, 22-23.09.2001, St. 4278, 0–3000 m. | IO RAN |

| Acanthephyra prionota | 13°22′ S, 47°38′ E | Madagascar Grand Shmidt 0–2000 m, 4.12.1974 | MNHN-IU-2018-1568 |

| Acanthephyra purpurea | 16° 04′ N; 46° 41′ W | “Professor Logatchev” 39 cruise St 233 | IO RAN 39L233 RT № 90 |

| Acanthephyra purpurea | 14° 40′ N; 45° 01′ W | “Professor Logatchev” 39 cruise St 178 RT, RTAK | IO RAN 39L 178RT № 93 |

| Acanthephyra quadrispinosa | 29°39′ S, 44°16′ E | Expedition ATIMO VATAE. SUD MADAGASCAR, Sud Pointe Barrow. Chalutier “Nosy Be 11”, Stn. CP 3596, 986–911 m. 12.05.2010. | MNHN-IU-2010-4285 |

| Acanthephyra quadrispinosa | 29°39′ S, 44°16′ E | Expedition ATIMO VATAE. SUD MADAGASCAR, Sud Pointe Barrow. Chalutier “Nosy Be 11”, Stn. CP 3596, 986–911 m. 12.05.2010. | MNHN-IU-2010-4285 |

| Acanthephyra sanguinea | 1°41′ N, 80°06′ E | N.O. “Marion Dufresne “ SAFARI II, St.8 CP11, 4360 m | MNHN-IU-2018-1569 |

| Acanthephyra sanguinea | 32°45′ S, 44°06′ E | Indian Ocean: Walters shoal, Plaine Sud. N.O. “Marion Dufresne”, Campagne MD208(Walters Shoal). Stn CP4914, 1598–1714 m. 11.05.2017 | MNHN-IU-2017-11196 |

| Acanthephyra sanguinea | 33°55′ S, 44°03′ E | Indian Ocean: Walters shoal, Plaine Nord-Est. N.O. “Marion Dufresne”, Campagne MD208(Walters Shoal). Stn CP4910, 986–988 m. 10.05.2017 | MNHN-IU-2016-9431 |

| Acanthephyra pelagica sica | Atlantic Ocean, R.V. “Akademik M. Keldysh”, 46 cruise. | IO RAN 19-D2 | |

| Acanthephyra pelagica sica | 37°37.8′ S, 77°51.8′ E | Chalutier Austral, Campagne de recherche 1996, Seamounts Iles Saint Paul et Amsterdam. Chalut pelagique №10. 03.07.1996. 17:15. 730–905 m. | MNHN-IU-2008-16810 |

| Acanthephyra pelagica sica | 33°55′ S, 44°03′ E | Indian Ocean: Walters shoal, N.O. “Marion Dufense”, Campagne MD208, Stn CP4914; 11.05.17; 1598–1714 m | MNHN-IU-2016-11793 |

| Acanthephyra smithi | 01°07′ S, 069°37′ E | Indian ocean. TE VEGA St. 189, 275–375 m. 01.11.1964 | USNM 125548 |

| Acanthephyra smithi | 12°28′ S, 48°06′ E | Indian ocean, RV “Vityaz”, cruise 17. 13.11.1988 | IO RAN |

| Acanthephyra stylorostratis | 06°59′ N, 78°50′ W | N.O. “Marion Dufresne “ SAFARI II, St.3 CP05, 2540 m | MNHN-IU-2018-1570 |

| Acanthephyra stylorostratis | 16°04′ N; 46°41′ W | “Professor Logatchev” 39 cruise St 233 RT, RTAK | IO RAN 39L 233RT № 92 |

| Acanthephyra stylorostratis | 16°04’ N; 46°40′ W | “Professor Logatchev” 39 cruise St 230 RT | IO RAN 39L 230RT № 31 |

| Acanthephyra stylorostratis | 14°38’ N; 44°56′ W | 39 cruise RV “Logatchev”, St 182 | IO RAN 39L182RT, № 46 |

| Acanthephyra sybogae | 05°04′30″ S, 130°12′00″ E | Alpha Helix R/V, AH 84. 28.04.1975. South Pacific Ocean, Banda sea, Indonesia. Widw. Traul RMT-8. Depth 0–1500 m. | USNM 195713 |

| Acanthephyra tenuipes | 13°22′ S, 47°38′ E | E-Madagascar Grand Schmidt 0–2000 m. 04.12.1974 | MNHN-IU-2018-1571 |

| Acanthephyra tenuipes | 29°50′9″ S, 48°35′5″ E | N.O. “Marion Dufresne “ SAFARI I St. 18, CP 10, 04.09.1979. 7:36–8:20, 3668–3800 m | MNHN-IU-2018-1572 |

| Acanthephyra trispinosa | 7°54′ S, 140°42′ W | Archipel des Marquises: ile Eiao. N/O “Alice” Campagne MUSORSTOM 9. Stn CP 1271, 600 m. 04.09.1997 | MNHN-IU-2018-1573 |

| Acanthephyra trispinosa | 10°18’00″ S, 161°54’0″ E | Oceanie, Salomon, Pacifique, Tree Sisters SALOMONBOA 3, Alis, CP 2820, prof. 75–819 m, 19.09.2007 | MNHN-IU-2016-9244 |

| Meningodora mollis | 34°06′ N, 17°06′ W | North Atlantic, Campagne Abyplaine, N.O. “Cryos”,Stn. CP11, 4270 m30.05.1981 | MNHN-IU-2011-5640 |

| Systellaspis debilis | 21°57′ N; 22°58′ W | Dana, 1920–1922, E 300. 27.10.192, St. 1157 | ZMUK |

Table A2.

List of characters and their coding.

Table A2.

List of characters and their coding.

| Character No | Character State | State No |

|---|---|---|

| 0. Rostrum, dorsal teeth subuliform and extending independently: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 1. Rostrum, 3 or less dorsal subuliform teeth extending independently | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 2. Rostrum, dorsal teeth subtriangular and extending from a common crest: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 3. Rostrum, numerous dorsal teeth are all set anterior to orbit: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 4. Rostrum as a triangle with subvertical anterior margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 5. Rostrum, postorbital saw-like dorsal teeth: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 6. Rostrum, numerous (4 or more) ventral teeth: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 7. Developed branchiostegal spine set posterior of anterior margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 8. Sharp branchiostegal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 9. Carapace, a long branchiostegal carina 0.5–1.0 of carapace length: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 10. Carapace, postorbital carina developed in the posterior half only: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 11. Carapace, a net of sharp reinforcing lateral carinae along whole length: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 12. Carapace, sharp reinforcing lateral carinae along ventral margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 13. Carapace, oblique transverse carina ventral of postorbital carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 14. Carapace, suprabranchial ridge: | inconspicuous | 0 |

| well-developed | 1 | |

| 15. Carapace, postorbital carina from orbit to posterior margin of carapace: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 16. Carapace, long (1/2 or more of carapace length) dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 17. First abdominal somite, anterior margin: | smooth | 0 |

| armed with a barb or tooth | 1 | |

| 18. First abdominal somite, a barb on anterior margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 19. First abdominal somite, dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 20. Second abdominal somite, strong dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 21. Third abdominal somite, sharp dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 22. Third abdominal somite, blunt dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 23. Fourth abdominal somite, dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 24. Fourth abdominal somite, a single spinule on lateral margin | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 25. Fourth abdominal, serration on lateral margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 26. Fifth abdominal somite, dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 27. Fifth abdominal somite, spinules on lateral margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 28. Fifth abdominal, serration on lateral margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 29. Sixth abdominal somite, dorsal carina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 30. Telson, spinose endpiece (type Oplophorus-Systellaspis): | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 31. Telson, dorsal ridge: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 32. Telson, dorsal sulcus along at least 1/3 of length: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 33. Telson, apex armed with 2 pairs of movable spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 34. Telson, numerous (15 or more) lateral spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 35. Mandibles, incisor process subtriangular, molar process without deep channel: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 36. Mandible, molar process consisting of rather deep channel flanked by thin walls opposing similar structure on other member: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 37. Mandible, subtriangular incisor process dentate along entire margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 38. Mandible, subtriangular incisor process dentate along proximal margin, plus a single distal tooth on distal margin: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 39. Mandible, incisor process dentate along proximal margin, distal margin unarmed: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 40. Second maxilla, proximal endite bearing well-developed submarginal papilla and lamina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 41. Second maxilla, proximal endite bearing reduced submarginal papilla and lamina: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 42. Second maxilliped, terminal segment attached to penultimate segment: | transversely | 0 |

| diagonally | 1 | |

| 43. Third pereopod, merus, anterior row of spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 44. Fourth pereopod, epipod: | vestigial or absent | 0 |

| well-developed | 1 | |

| 45. Fourth pereopod, ischium, anterior row of spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 46. Fifth pereopod, ischium, anterior row of spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 47. Fifth pereopod, ischium, posterior row of spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 48. Fifth pereopod, merus, anterior row of spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 49. Fifth pereopod, merus, posterior row of spines: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 50. Fifth pereopod, dactyl: | short | 0 |

| elongate | 1 | |

| 51. Fifth pereopod, rudimentary dactyl: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 52. Fifth pereopod, dactyl, several apical claws: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 53. Fifth pereopod, 8–10 rows of movable spines on inner surface of dactyl: | absent | 0 |

| present | 1 | |

| 54. Eggs: | large and few (<50) | 0 |

| small and numerous (>80) | 1 |

Table A3.

DATA MATRIX. Missing data indicated by question marks.

Table A3.

DATA MATRIX. Missing data indicated by question marks.

| Characters 0–50 | |||||||||||

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Systellaspis debilis | 00100 | 11000 | 00000 | 00110 | 00001 | 10110 | 10100 | 01100 | 01011 | 11111 | 10010 |

| Meningodora mollis | 001001001001110110000011001001001101001110100000000 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra curtirostris | 001011001100000010001101001001001101010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra media | 001011001100000010001101001001001101010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra cucullata | 001011001110000010001101001001001101010010110000010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra stylorostratis | 001011001110000010001101001001001101010010110000110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra armata | 001001101000001010001101001001010101010010110000010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra carinata | 001001101000001010011101001001010101010010110000110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra faxoni | 001001101000001010001101001001010101010010110000010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra eximia | 001001100000001010001101001001010101010010110000010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra fimbriata | 001001101000001010001101001001010101010010100001010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra pelagica | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010100001010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra acanthitelsonis | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010100001010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra kingsleyi | 0011001000000000000011010010010011010100101?000??10 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra purpurea | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010100000010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra quadrispinosa | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010100001010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra sanguinea | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyrapelagicasica | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra smithi | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010100000010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra trispinosa | 001100100000000000001101001001001101010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra acutifrons | 001001001000000010011101001001001101010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra indica | 110000001100010110001101001001001101010010110000010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra prionota | 0010010100100000000001010010010011010100101?0001010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra tenuipes | 0010010100100000000001010010010011010100101?0001010 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra heatheri | 0010010110100000000001010010010011010100101?0001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra brevicarinata | 001001001000000010001101001001001111010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra brevirostris | 0010010010000000000001010010010011010100101?000???0 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra chacei | 111000001000000010000101001001001101010010110001110 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra sibogae | 0010010010000000100001010010010011010100101?000???0 | ||||||||||

| Characters 51–54 | |||||||||||

| 51 | |||||||||||

| | | |||||||||||

| Meningodora mollis | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra curtirostris | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra media | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra cucullata | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra stylorostratis | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra armata | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra carinata | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra faxoni | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra eximia | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra fimbriata | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra pelagica | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra acanthitelsonis | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra kingsleyi | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra purpurea | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra quadrispinosa | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra sanguinea | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyrapelagicasica | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra smithi | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra trispinosa | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra acutifrons | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra indica | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra prionota | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra tenuipes | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra heatheri | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra brevicarinata | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra brevirostris | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra chacei | 1101 | ||||||||||

| Acanthephyra sibogae | 1101 | ||||||||||

References

- Vereshchaka, A.; Abyzova, G.; Lunina, A.; Musaeva, E.; Sutton, T. A novel approach reveals high zooplankton standing stock deep in the sea. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 6261–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchaka, A.L.; Lunina, A.A.; Sutton, T. Assessing deep-pelagic shrimp biomass to 3000 m in the Atlantic Ocean and ramifications of upscaled global biomass. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 11 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hanamura, Y. Description of a new species Acanthephyra brevicarinata (Crustacea, Decapoda, Caridea) from the Eastern tropical Pacific, with notes on biological characteristics. Bull. Plankton Soc. Jpn. 1984, 31, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vereshchaka, A.; Kulagin, D.; Lunina, A.A. A New Shrimp Genus (Crustacea: Decapoda) from the Deep Atlantic and an unusual cleaning mechanism of pelagic Decapods. Diversity 2021, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.W. On Acanthephyra purpurea and its allies (Crustacea Decapoda: Hoplophoridæ). Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1939, 4, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chace, F.A. The Caridean Shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda) of the Albatross Philippine Expedition, 1907–1910, Part 4: Families Oplophoridae and Nematocarcinidae; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1986; 81p. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.M.; Pérez-Moreno, J.L.; Chan, T.Y.; Frank, T.M.; Bracken-Grissom, H.D. Phylogenetic and transcriptomic analyses reveal the evolution of bioluminescence and light detection in marine deep-sea shrimps of the family Oplophoridae (Crustacea: Decapoda). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 83, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.W. On the occurrence of the genus Acanthephyra in deep water off the West Coast of Ireland. Fish. Irel. Sci. Investig. 1906, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Burukovsky, R.N.; Romensky, L.L. New Findings of Several Species of Shrimps and Description of Pasiphaea natalensis sp.n. Zool. Zhurnal 1982, 61, 1797–1801, (In Russian with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, K. The parsimony ratchet, a new method for rapid parsimony analysis. Cladistics 1999, 15, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloboff, P.; Farris, S.; Nixon, K. TNT: Tree Analysis Using New Technology. 2000. Available online: http://www.lillo.org.ar/phylogeny/tnt/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Aznar-Cormano, L.; Brisset, J.; Chan, T.-Y.; Corbari, L.; Puillandre, N.; Utge, J.; Zbinden, M.; Zuccon, D.; Samadi, S. An improved taxonomic sampling is a necessary but not sufficient condition for resolving inter-families relationships in Caridean decapods. Genetica 2015, 143, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunina, A.A.; Kulagin, D.N.; Vereshchaka, A.L. Phylogenetic revision of the shrimp genera Ephyrina, Meningodora and Notostomus(Acanthephyridae: Caridea). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2021, 193, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubart, C.D.; Huber, M.G.J. Genetic comparisons of German populations of the stone crayfish, Austropotamobius torrentium (Crustacea: Astacidae). Bull. Français Pêche Piscic. 2006, 380–381, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubart, C.D. Mitochondrial DNA and decapod phylogenies: The importance of pseudogenes and primer optimization. Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics 2009, 4, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal, F.; Zardoya, R.; Telford, M.J. TranslatorX: Multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W7–W13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. PartitionFinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunina, A.A.; Kulagin, D.N.; Vereshchaka, A.L. Oplophoridae (Decapoda: Crustacea): Phylogeny, taxonomy and evolution studied by a combination of morphological and molecular methods. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 186, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunina, A.A.; Kulagin, D.N.; Vereshchaka, A.L. A hard-earned draw: Phylogeny-based revision of the deep-sea shrimp Bentheogennema (Decapoda: Benthesicymidae) transfers two species to other genera and reveals two new species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 178, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchaka, A.L.; Corbari, L.; Kulagin, D.N.; Lunina, A.A.; Olesen, J. A phylogeny-based revision of the shrimp genera Altelatipes, Benthonectes and Benthesicymus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Benthesicymidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 189, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchaka, A.L.; Kulagin, D.N.; Lunina, A.A. Across the benthic and pelagic realms: A species-level phylogeny of Benthesicymidae (Crustacea: Decapoda). Invertebr. Syst. 2021, 35, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).