Abstract

Endometriosis is traditionally conceptualized as a pelvic lesion–centered disease; however, mounting evidence indicates it is a chronic, systemic, and multifactorial inflammatory disorder. This review examines the molecular dialog between ectopic endometrial tissue, the immune system, and peripheral organs, highlighting mechanisms that underlie disease chronicity, symptom variability, and therapeutic resistance. Ectopic endometrium exhibits distinct transcriptomic and epigenetic signatures, disrupted hormonal signaling, and a pro-inflammatory microenvironment characterized by inflammatory mediators, prostaglandins, and matrix metalloproteinases. Immune-endometrial crosstalk fosters immune evasion through altered cytokine profiles, extracellular vesicles, immune checkpoint molecules, and immunomodulatory microRNAs, enabling lesion persistence. Beyond the pelvis, systemic low-grade inflammation, circulating cytokines, and microRNAs reflect a molecular spillover that contributes to chronic pain, fatigue, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation, and emerging gut–endometrium interactions. Furthermore, circulating biomarkers—including microRNAs, lncRNAs, extracellular vesicles, and proteomic signatures—offer potential for early diagnosis, patient stratification, and monitoring of therapeutic responses. Conventional hormonal therapies demonstrate limited efficacy, whereas novel molecular targets and delivery systems, including angiogenesis inhibitors, immune modulators, epigenetic regulators, and nanotherapeutics, show promise for precision intervention. A systems medicine framework, integrating multi-omics analyses and network-based approaches, supports reconceptualizing endometriosis as a systemic inflammatory condition with gynecologic manifestations. This perspective emphasizes the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to advance diagnostics, therapeutics, and individualized patient care, ultimately moving beyond a lesion-centered paradigm toward a molecularly informed, holistic understanding of endometriosis.

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen-dependent inflammatory disorder defined by the presence of endometrial-like glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity, provoking sustained inflammation and commonly associated with pain and infertility. Globally, it affects roughly 10–15% of women of reproductive age, with an estimated 9 million cases in the United States, and prevalence reaching up to 70% among individuals with chronic pelvic pain [1]. U.S. hospital data indicate that 11.2% of women aged 18–45 admitted for genitourinary concerns and 10.3% undergoing gynecologic surgery receive an endometriosis diagnosis [2]. Beyond clinical morbidity, endometriosis imposes significant economic burdens, with average annual per-patient costs around €10,000 in Europe and higher expenditures in the United States of America [3].

Clinically, the condition is primarily associated with pelvic pain, including dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and discomfort without menstruation, reported by nearly 90% of patients, alongside infertility affecting up to 50% of those diagnosed [2,4]. Lesions most frequently involve the ovaries, uterosacral ligaments, and peritoneum but may extend to extrapelvic sites such as the urinary tract, intestines, pleura, pericardium, and central nervous system [5]. Diagnosis is often delayed, averaging 5–12 years from symptom onset, with patients consulting multiple providers before confirmation, which remains largely dependent on laparoscopic visualization, despite increased use of transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [6]. Risk factors include early menarche, short menstrual cycles, heavy menstrual bleeding, and nulliparity, whereas protective factors encompass parity, extended breastfeeding, hormonal contraceptive use, tubal ligation, regular physical activity, and dietary omega-3 intake [1].

The pathogenesis of endometriosis is multifactorial (Figure 1). While Sampson’s retrograde menstruation theory is widely referenced, it alone does not account for the disease, as retrograde flow occurs in many women without pathology [5]. Additional mechanisms—coelomic metaplasia, Müllerian remnants, vascular or lymphatic dissemination, stem cell contribution, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and genetic and epigenetic factors—further explain the systemic and heterogeneous nature of the disorder [7].

Traditional lesion-centered approaches face limitations, particularly in surgically accessing deep lesions near the bowel or bladder, which raises the risk of inadvertent injury [8]. Two-dimensional imaging may inadequately capture vascular supply or precise relationships with adjacent organs [8,9], and ultrasound or computed tomography can be insufficient for complex lesions near gas-filled structures [8,10,11,12]. These constraints underscore the utility of advanced imaging modalities, including multiplanar MRI and 3D reconstruction, which improve lesion visualization, surgical mapping, and planning [8,9].

At the molecular level, endometriosis is marked by dysregulated cellular signaling, immune dysfunction, and hormone resistance, supporting ectopic tissue survival. Critical pathways include phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) and Wingless-related integration site (Wnt)/β-catenin, which enhance proliferation and survival, alongside nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), a central mediator of chronic inflammation [13,14]. Epigenetic changes, such as cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) methylation, and genetic predisposition further reinforce disease establishment and persistence [15]. Key molecular processes involve aberrant cell signaling, immune evasion, hormonal imbalance, epigenetic regulation, oxidative stress, inflammation, tissue invasion, and fibrosis [7,13,16].

This review aims to examine the systemic nature of endometriosis, emphasizing molecular crosstalk and its implications for chronicity, clinical manifestations, and potential therapeutic strategies.

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of endometriosis and the primary factors contributing to its development. Since the pathophysiology of endometriosis is not yet fully understood due to its complexity and multifactorial nature, several hypotheses have been proposed to explain its development, including the theories of retrograde menstruation, coelomic metaplasia, embryogenic origin, stem cell implantation, and vascular or lymphatic dissemination of endometrial cells. Factors involved in its progression include hormonal, genetic, immunological, and environmental influences—such as poor nutrition (including processed foods), tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and chronic stress—which act as aggravating elements that may intensify inflammation and promote disease advancement [17,18,19]. Created in BioRender. Reytor, C. (2026) https://BioRender.com/0z5en66 (accessed on 12 January 2026).

2. The Molecular Identity of Ectopic Endometrial Tissue

The molecular landscape of endometriotic lesions reveals a unique identity that distinguishes ectopic endometrial tissue from its eutopic counterpart. Although these lesions share histological similarities with the normal endometrium, they display specific transcriptomic, epigenetic, and hormonal alterations that underlie their survival, pro-inflammatory profile, and reduced responsiveness to conventional therapies [20]. Elucidating these molecular distinctions is essential for identifying novel therapeutic targets and improving disease management.

2.1. Transcriptomic and Epigenetic Profiles of Ectopic vs. Eutopic Endometrial Cells

Epigenetics refers to inheritable alterations in gene regulation that occur without changes in the DNA sequence, functioning as key modulators of cellular activity. These mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications such as acetylation, phosphorylation, and methylation, as well as non-coding RNAs. Together, they remodel chromatin architecture and influence gene activation or repression. In parallel, transcriptomics provides a global view of RNA transcripts in cells or tissues, uncovering divergences between healthy and diseased states and offering insights into the molecular mechanisms of endometriosis [21].

Comparative transcriptomic studies demonstrate marked differences between ectopic and eutopic endometrium. Ectopic lesions upregulate genes promoting proliferation, angiogenesis, and inflammation, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin-8 (IL-8), supporting lesion growth and invasiveness [22]. By contrast, eutopic endometrium retains gene programs linked to cyclic remodeling and receptivity. Co-expression analyses highlight this divergence: eutopic cells enrich adhesion and implantation pathways, while ectopic tissue displays enrichment in migration, epithelial maturation, and gap junction assembly. Expression profiling revealed 688 upregulated and 298 downregulated genes in eutopic endometrium compared to controls, while ectopic lesions showed 155 upregulated genes such as Piwi-like RNA-mediated gene silencing 2, fms-related tyrosine kinase 1, and sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 11 [22]. Direct comparison identified 7450 genes overexpressed in ectopic tissue, including oncogenic testis-expressed 41, DNA polymerase theta, and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1, along with suppression of tumor suppressors such as phospholipase C delta 1 (PLCD1) and odd-skipped related transcription factor 2 (OSR2), underscoring tumor-like properties of invasion and recurrence [23].

Functionally, ectopic lesions are shaped by hypoxia and altered 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) signaling, which reprogram metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, reminiscent of the Warburg effect in cancer. This shift enhances energy and biomass production, sustaining lesion persistence [24]. Consequently, emerging nonhormonal therapies target these metabolic pathways, including inhibition of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) and regulators of pyruvate metabolism such as lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) [25].

Single-cell RNA sequencing has refined this landscape by uncovering the heterogeneity of endometriotic lesions. Ectopic stromal cells preserve endometrial features but aberrantly express genes such as CXCL8, CXCL2, and WNT5A, promoting angiogenesis, wound healing, and inflammation. These cells also interact with ovarian stroma and immune components via Wingless-related integration site (WNT) and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, fostering lesion survival [26]. More recent single-cell atlases highlight fibroblasts (FBs) as central to pathogenesis. FBs from ectopic and eutopic sources display distinct but convergent pro-fibrotic, estrogen-driven, and immune-modulatory phenotypes. Aberrant estrogen receptor (ER) β expression, reduced progesterone receptor (PGR), and increased cytochrome P450 family 19 subfamily A member 1 (CYP19A1) disrupt hormone signaling, while FB crosstalks with macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, and T lymphocytes promotes immune evasion and chronic inflammation. Pathway analysis confirmed activation of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), NF-κB, and Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling, linking FB dysfunction to lesion persistence [27].

Epigenetic alterations further consolidate these molecular programs. Hypermethylation of tumor suppressors such as PGR-B, SF-1, and RASSF1A in ectopic tissue contributes to estrogen dominance and progesterone resistance [28]. Histone modifications regulate genes like PPARγ, HOX10, and ESR1, influencing proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle control [29]. In addition, non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs, fine-tune inflammatory, survival, and immune pathways. Although HOXA10 methylation findings remain variable, histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) have shown potential in suppressing ectopic lesion growth, reinforcing the therapeutic promise of targeting epigenetic mechanisms [21,25].

2.2. Disrupted Hormonal Signaling: Local Estrogen Overproduction and Progesterone Resistance

Ectopic endometrial tissue exhibits marked hormonal dysregulation, characterized by excessive local estrogen production and progesterone resistance. Elevated aromatase expression drives abnormal intralesional estrogen accumulation, promoting proliferation and survival, while reduced PGR expression and downstream disruption impair progesterone signaling. This loss weakens anti-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic actions, facilitating lesion persistence. Endometriosis is therefore considered a hormone-dependent disorder sustained by endocrine imbalance and complex molecular mechanisms involving estrogen and progesterone [30].

Estrogens, synthesized from cholesterol, include E2, the most active isoform due to its strong affinity for ERs. ERα and ERβ regulate transcription upon ligand binding, whereas membrane-associated ERs activate rapid PI3K, MAPK, and Ca2+ cascades. Dysregulated ER signaling contributes to inflammation and uncontrolled growth. GPER1, a membrane G protein-coupled ER, is aberrantly expressed in ectopic lesions, and its inhibition reduces proliferation and invasion, underscoring its role in progression [31].

Local estrogen production is maintained by aberrant steroidogenesis. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), normally limited to adrenal and gonadal tissues, is overexpressed in stromal cells via prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)-induced cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation. Aromatase, encoded by CYP19A1, physiologically expressed in granulosa cells, adipose, bone, and brain, is markedly upregulated in endometriosis, especially in ovarian endometriomas with high E2 levels. Enzymes of the 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (HSD17β) family further regulate estrogen activity: the conversion of estrone (E1) to estradiol is increased, while the conversion of E2 to E1 is suppressed [32]. Steroid sulfatase (STS), reactivating estrone sulfate, is upregulated, whereas estrogen sulfotransferase (EST), which inactivates estrogens, is reduced, altogether sustaining estrogen excess [33].

Inflammatory mediators closely regulate these enzymes. PGE2, a potent steroidogenic inducer, activates the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway via prostaglandin E2 receptor 2/prostaglandin E2 receptor 4, stimulating steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) and CREB to upregulate STAR and CYP19A1 [34]. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), consistently elevated in stromal cells, drives sustained PGE2 production. Upstream signals such as NF-κB, IL-1β, VEGF, and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) amplify COX-2, creating a feedback loop between inflammation and estrogen synthesis. NF-κB also increases cytokine and aromatase expression, reinforcing estrogen dominance [34]. Activated platelets further intensify this loop by engaging NF-κB and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1)/mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (Smad3) signaling, which enhances cytokine release, hypoxia, and E2 production through the PGE2-cAMP axis, positioning platelets as amplifiers of estrogen excess.

Progesterone resistance is another hallmark of endometriosis. Ectopic tissue shows reduced PGR expression, particularly loss of PGR-B, disturbing the PRA:PRB ratio and diminishing responsiveness. ERβ overexpression suppresses PR, while PR-B promoter hypermethylation silences this isoform. NF-κB-driven PR-B downregulation and DNA methylation, along with toxicants, genetic variants, and microRNAs (miR-196a, miR-29c, miR-297), further disrupt PGR signaling [35]. Functionally, resistance arises from aberrant PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and Notch receptor 1 (NOTCH1) activation, and impairment of the Indian hedgehog–chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor II–Wingless-related integration site 4 signaling cascade (IHH-COUPTFII-WNT4), leading to defective decidualization [36]. Regulators such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6), and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) suppress PGR targets, while reduced co-regulators (FK506-binding protein 52, HOXA10, FOXO1, SOX17) weaken progesterone action [29]. Importantly, HSD17β2, normally induced by progesterone to inactivate E2, fails to be expressed, reinforcing estrogen accumulation and progesterone resistance [34].

These hormonal alterations reflect crosstalk between endocrine, inflammatory, and epigenetic pathways. Impaired retinoic acid signaling and PGR downregulation reduce HSD17β2 activity, while a disrupted PR-A/PR-B ratio alters specificity protein 1/specificity protein 3 (Sp1/Sp3)-mediated transcription of enzymes critical for estrogen inactivation [37]. Consequently, estrogen-driven proliferation and survival dominate, while progesterone-mediated differentiation and anti-inflammatory responses remain suppressed.

2.3. Key Molecules in the Altered Microenvironment: HIF-1α, VEGF, IL-8, Prostaglandins, and Matrix Metalloproteinases

The microenvironment of ectopic endometrial lesions in endometriosis is shaped by chronic inflammation, dysregulated immune cell activity, increased angiogenesis, hormonal imbalance, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and metabolic alterations [25]. Within this pathological setting, central mediators such as HIF-1α, VEGF, IL-8, prostaglandins, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) sustain lesion growth, proliferation, and invasion. Together, these mechanisms promote lesion persistence and contribute to hallmark symptoms, particularly pelvic pain and infertility [38].

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is a heterodimer composed of the oxygen-regulated HIF-1α and the constitutively expressed HIF-1β subunits [39]. Under low oxygen conditions, HIF-1α stabilizes, translocates to the nucleus, and interacts with HIF-1β to regulate gene transcription via hypoxia-responsive elements. In the endometrium, HIF-1α plays essential roles in tissue repair, decidualization, and maternal–fetal signaling by promoting vascularization and epithelial regeneration through VEGF, IL-8, and adrenomedullin [39]. Dysregulated HIF-1α expression is associated with heavy menstrual bleeding, defective extracellular matrix remodeling, and abnormal neutrophil recruitment [40,41]. In endometriosis, HIF-1α is consistently overexpressed [42], supporting lesion survival through microRNA(miR)-210-3p signaling, mitochondrial adaptation, and autophagy regulation [24,43,44], and facilitating epithelial–mesenchymal transition [45]. Additionally, HIF-1α increases prostacyclin synthase via DNMT1 inhibition, elevating prostacyclin (PGI2) levels and promoting cellular adhesion [46]. It also enhances VEGF, MMPs, IL-8, and COX-2 expression, linking hypoxia to angiogenesis, invasion, prostaglandin production, and inflammation [47].

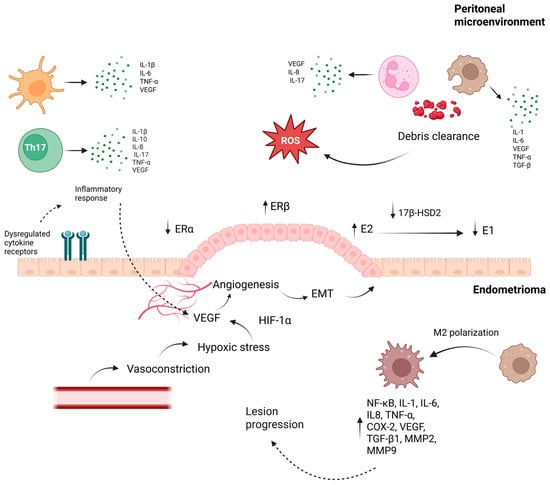

Elevated VEGF levels in serum and peritoneal fluid of EM patients correlate with lesion vascularization [48,49]. Retrograde menstruation contributes to oxidative stress and cytokine release, promoting VEGF expression, while impaired debris clearance and immune dysregulation further exacerbate lesion progression [50] (Figure 2). Among these immune-derived mediators, IL-8 has emerged as a particularly relevant effector due to its potent angiogenic activity and it is elevated in the peritoneal fluid of EM patients, where it recruits neutrophils and promotes endometrial cell proliferation [51]. Its expression correlates with lesion severity and contributes to neovascularization, nociceptor sensitization, reduced oocyte quality, infertility, and the adhesion, invasion, and proliferation of ectopic endometrial cells [52,53].

Prostaglandins are also critical mediators of the altered microenvironment. Elevated estrogen induces PGE2, which stimulates COX-2 and aromatase, forming a positive feedback loop that sustains hyperestrogenism [30]. In EM, PGE2 reduces macrophage MMP-9 and CD36 expression, impairing phagocytosis and promoting lesion persistence [54]. It further enhances aromatase activity, Th2 polarization, and local estrogen production [55]. PGE2 signaling differs among lesion types, with fibrosis-related variations in COX-2 and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase shaping disease heterogeneity [56].

MMP expression is elevated in endometriotic tissue, with MMP-9 levels correlating with disease severity [57,58]. Meta-analyses confirm upregulation of MMP-9 in serum and lesions, indicating its potential as a diagnostic biomarker [59].

Figure 2.

Peritoneal–Endometrioma crosstalk driving inflammation, hypoxia, and lesion progression in endometriosis. The bidirectional interaction shown promotes lesion establishment and progression in endometriosis. In the peritoneal compartment, immune cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors—including IL-6, IL-8, IL-17, and VEGF—driving oxidative stress and impairing debris clearance. During menstruation, macrophages and neutrophils clearing endometrial debris generate ROS, and ectopic tissue simultaneously exposed to elevated Fe2+, hypoxia, and inflammatory cytokines undergoes oxidative damage, thereby intensifying local inflammatory signaling. Immune dysregulation simultaneously fuels angiogenesis, with macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and T lymphocytes releasing VEGF together with IL-6, IL-8, and IL-17, a pro-angiogenic effect especially prominent in neutrophils, whose secretion is further intensified by estrogen. Among HIF-1α downstream targets, VEGF is central to angiogenesis, acting through VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3 to promote endothelial proliferation, migration, and vascular permeability. Dysregulated estrogen signaling—characterized by increased ERβ expression and altered local estrogen metabolism via 17β-HSD2—enhances E2 availability, fueling angiogenesis, EMT, oxidative stress, and hypoxia-related responses. Hypoxia-induced VEGF expression, together with vasoconstriction, facilitates neovascularization and supports lesion survival. In parallel, macrophage polarization toward an M2 phenotype maintains a pro-angiogenic and pro-fibrotic milieu through NF-κB activation and the secretion of cytokines, growth factors, and MMPs. In parallel, MMP-2 and MMP-9 function as key downstream effectors regulated by estrogen, inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and PGE2, promoting extracellular matrix degradation, EMT, angiogenesis, and fibrosis; additionally, MMP-9 interacts with PGE2 and TNF-α pathways, reinforcing chronic inflammation and lesion expansion. By enabling endothelial migration and releasing ECM-bound growth factors, MMPs further potentiate VEGF-driven angiogenesis. Together, these interrelated processes establish a self-sustaining inflammatory, estrogen-dependent, and hypoxia-adapted niche that underpins endometrioma persistence and progression [60,61,62,63,64,65]. Abbreviations: Th17: T helper 17 cells; IL: interleukin; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha; ROS: reactive oxygen species; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; ERα: estrogen receptor alpha; ERβ: estrogen receptor beta; E2: estradiol; E1: estrone; 17β-HSD2: 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2; EMT: epithelial–mesenchymal transition; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor beta 1; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; ECM: extracellular matrix.arrows; (↑) indicate increased levels or overexpression; (↓) indicate reduced levels or functional downregulation Created in BioRender. Reytor, C. (2026) https://BioRender.com/ndwzjhc (accessed on 12 January 2026).

3. Immune-Endometrial Crosstalk: Mechanisms of Escape and Chronicity

3.1. Immune Dysfunction and Abnormal Tolerance Toward Ectopic Tissue

Endometriosis is marked by immune dysregulation, with disturbances in both peripheral and endometrial immunity that contribute to infertility, early pregnancy loss, and impaired tissue homeostasis [66]. Clinical evidence shows an increased prevalence of immune-mediated and autoimmune disorders among affected women, suggesting shared pathogenic pathways [67,68,69]. The participation of immune cells is central to disease development, particularly macrophages [70,71], natural killer (NK) cells [72], T lymphocytes [73], and B cells [74]. Hormonal imbalances in endometriosis are known to alter macrophage function, while dysregulated cytokine signaling and impaired immune responses sustain systemic inflammation, a major factor underlying infertility in affected women [75]. Additional immune defects include reduced NK cell cytotoxicity, insufficient dendritic cell maturation, and T cell inhibition through immune checkpoints, all of which establish an immunosuppressive niche that permits lesion survival and progression [75]. Mass cytometry has also demonstrated increased T cell activation in the peritoneal fluid of endometriosis patients compared with controls [76]. More specifically, Huang et al. [77] employed single-cell RNA sequencing of ovarian endometriosis samples and identified five distinct cellular clusters. Among them, mesenchymal endometrial cells predominated and exhibited elevated inflammatory activity and estrogen synthesis. Importantly, the study also revealed a marked reduction in CD8 + T cells within endometriotic lesions, while ectopic T cells displayed diminished cytokine secretion and cytotoxic potential. Such findings highlight CD8 + T cell dysfunction as a critical mechanism fostering abnormal immune tolerance to ectopic endometrial tissue, thereby enabling chronic inflammation and disease persistence.

3.2. Roles of NK Cells, M2 Macrophages, Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells, and Treg Cells

Building on the evidence of immune dysregulation in endometriosis, the interplay between innate and adaptive immune cells within the peritoneal cavity further establishes a permissive microenvironment that supports ectopic tissue survival, angiogenesis, and fibrotic remodeling. NK cells exhibit pronounced functional impairment, including reduced expression of granzyme B, perforin, TRAIL, and CD107a, together with increased inhibitory killer immunoglobulin-like receptors, which collectively limit their ability to eliminate refluxed endometrial fragments [65,78]. Concurrently, macrophages are recruited to peritoneal fluid and ectopic lesions, predominantly adopting an M2 (CD206+) polarization. These cells contribute to lesion progression by secreting VEGFA, MMP-2 and MMP-9, while impaired phagocytic activity and iron accumulation exacerbate oxidative stress and chronic inflammation [79,80]. Treg cells (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+), which are enriched in peritoneal fluid and lesions, release IL-10 and TGF-β, reinforcing immune tolerance, inhibiting the maturation of imDCs, and indirectly promoting M2 macrophage polarization via FGL2-mediated signaling, thereby establishing a self-sustaining feedback loop between adaptive and innate immunity that supports lesion maintenance [81,82]. Dendritic cells exhibit an altered balance, with increased imDCs (CD1a+) and decreased mature DCs (CD83+), which facilitate angiogenesis and ectopic tissue survival through the release of IL-10, IL-1β, and IL-6, while MDC1 subsets expressing mannose receptors phagocytose dead stromal cells and amplify local inflammatory signals [83,84,85]. Together, these coordinated cellular alterations consolidate a permissive immune landscape that sustains lesion growth, vascular remodeling, fibrosis, and neurogenic pain.

3.3. Immune Evasion Mechanisms: Cytokine Profiles, Integrins, Extracellular Vesicles, Immune Checkpoint Molecules

Beyond cellular composition, immune evasion in endometriosis is reinforced at the molecular level through deregulated cytokine networks, altered adhesion signaling, extracellular vesicle (EV)-mediated communication, and immune checkpoint pathway activation. Elevated concentrations of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines—particularly members of the TGFβ family—are consistently detected in serum, peritoneal fluid, and ectopic lesions, reflecting contributions from epithelial, stromal, mesenchymal, and immune cell populations [86]. Pro-inflammatory mediators and macrophage migration inhibitory factor stimulate angiogenesis, oxidative stress, and aberrant stromal proliferation, while weakening immune cell clearance mechanisms and sustaining chronic inflammation [87,88,89,90,91]. Concurrently, anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IL-33, and IL-37, promote a Th2 and Treg-dominated environment that limits cytotoxic responses and enhances tolerance to ectopic tissue [55,92,93,94]. These cytokine imbalances contribute to ICAM-1 downregulation and abnormal IL-1 family signaling, weakening T-cell interactions with endometrial cells and facilitating lesion persistence through NF-κB activation [95,96].

Aberrant integrin expression further contributes to immune escape and lesion establishment by enhancing adhesion of endometrial cells to peritoneal extracellular matrix components and activating invasive signaling pathways [16,97,98]. Chemokines such as CCL5 reinforce this process by recruiting immune cells and sustaining local inflammation [31]. Meanwhile, EVs derived from immune and endometrial cells serve as potent intercellular messengers that remodel the immune microenvironment. Their molecular cargo, including proteins, miRNAs, and lncRNAs, regulates angiogenesis, immune suppression, and stromal proliferation [86,99]. These vesicles also promote macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype through miR-301a-3p and miR-223, suppress T-cell activity via ARG1 induction, and increase extracellular adenosine through CD39/CD73 expression, collectively reinforcing immune tolerance [100,101,102]. Additional EV-mediated signals enhance stromal cell motility and invasion, perpetuating lesion expansion within a “pro-endometriotic niche” [100,102,103,104,105].

Finally, immune checkpoint molecules act as critical modulators of immune suppression in endometriosis. Elevated soluble forms of sPD-L1, sPD-1, sHLA-G, and sCTLA-4 in both serum and peritoneal fluid correlate with lesion severity and infertility [106]. Upregulated PD-1/PD-L1 expression in immune and endometrial cells suppresses T-cell proliferation and cytokine release, reduces NK-cell cytotoxicity, and enhances Treg expansion, leading to immune exhaustion [107,108,109]. Estrogen further induces PD-L1 expression in endometrial epithelial cells, reinforcing local immune tolerance [110]. Overall, cytokine imbalance, altered integrin signaling, EV-mediated suppression, and checkpoint activation collectively sustain an immunosuppressive niche that parallels tumor-like immune evasion [111,112].

3.4. Immunomodulatory microRNAs Driving Lesion Persistence

Aberrant regulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) has been identified as a pivotal factor underlying the immune, inflammatory, and hormonal disturbances that sustain lesion persistence and infertility in endometriosis [113,114]. These small non-coding RNAs act as key post-transcriptional regulators of cytokine production, angiogenesis, apoptosis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), and progesterone receptor activity, collectively fostering a microenvironment conducive to ectopic tissue survival [115]. Reduced miR-138 activates NF-κB–dependent transcription, enhancing inflammatory and angiogenic mediator expression, while inflammatory stimuli reciprocally induce miR-302a, which suppresses differentiation-related transcription factors and increases cyclooxygenase-2 expression [116]. This bidirectional feedback between miRNAs and cytokines perpetuates chronic inflammation. Downregulation of let-7 family members, particularly let-7b-5p, derepresses ERα, ERβ, aromatase, KRAS, and IL-6, reinforcing estrogen-driven and inflammatory signaling, whereas elevated miR-125b-5p combined with reduced let-7b-5p amplifies macrophage-associated inflammatory outputs [31]. Loss of miR-33b further promotes angiogenesis and proliferation through VEGF and MMP-9 upregulation and reduced apoptotic signaling [47]. Increased miR-146b in peritoneal fluid selectively attenuates M1 macrophage polarization, favoring immune tolerance [117]. Additional miRNAs regulate stromal plasticity and invasiveness. Decreased miR-182 and miR-10b facilitate EMT and IL-6–associated signaling [118], while inflammatory miRNA signatures in peritoneal fluid—including miR-106b-3p, miR-451a, and miR-486-5p—reflect sustained molecular activation within the peritoneal microenvironment [119]. Progesterone resistance is reinforced by miR-29c, miR-135a/b, miR-196a, and miR-194-3p through impaired PR signaling and FKBP4 downregulation [120], while miR-21-5p directly suppresses PR expression, an effect reversible upon its inhibition [121]. Upregulation of miR-29c and miR-143-3p further promotes proliferation, invasion, and EMT through c-Jun and TGF-β/VASH1 pathways [122]. Altogether, dysregulated miRNAs—particularly miR-138, miR-146b, miR-125b-5p, miR-29c, and miR-143-3p—coordinate a network of inflammatory cytokines, angiogenic mediators, and PR pathway suppressors, shaping a chronic, estrogen-dominant, and immune-tolerant environment that perpetuates lesion survival, infertility, and disease progression in endometriosis [117,118,121,122,123,124,125].

4. Systemic Footprint: Peripheral Manifestations and Molecular Spillover

4.1. Evidence of Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation in Endometriosis Patients

Endometriosis is increasingly recognized as a chronic, low-grade systemic inflammatory disease with physiological repercussions extending far beyond the reproductive tract, such as metabolic, neurological, and immune dysfunction.

Patients frequently display adipocyte and hepatic metabolic disturbances, including reduced body mass index, along with neurobiological changes that heighten pain perception and predispose to fatigue, anxiety, and depression [126]. The systemic inflammatory milieu contributes to localized inflammatory microenvironments in multiple organs and a higher prevalence of immune-mediated diseases [127]. Clinically, endometriosis manifests not only with pelvic pain and infertility but also systemic symptoms such as bowel and bladder dysfunction and persistent fatigue, which affect most patients [128]. Central nervous system involvement is evident, with affected women being almost twice as likely to experience depression compared to controls [129]. Epidemiological studies also indicate elevated cardiovascular risk, with hazard ratios of 1.24 for overall cardiovascular disease and 1.4 for ischemic heart disease [130].

Circulating miRNAs may mediate systemic communication and pathophysiology in endometriosis, as alterations in their abundance are increasingly investigated as diagnostic and mechanistic biomarkers [131,132]. Experimental studies further confirm systemic neurobiological effects: in murine models, endometriosis alters gene expression in brain regions such as the insula, hippocampus, and amygdala, inducing electrophysiological and behavioral changes associated with hyperalgesia, anxiety, and depression [133]. These findings parallel clinical symptoms in women and suggest that neuroinflammation and altered neuronal circuitry contribute to pain sensitization and mood disturbances.

At the molecular level, oxidative stress is pivotal in sustaining chronic inflammation. As seen in Figure 2, the ROS produced creates a redox imbalance that facilitates lesion implantation and correlates with disease severity [134]. Antioxidants such as melatonin and resveratrol demonstrate anti-inflammatory and antioxidative benefits, improving dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain according to meta-analyses. At the systemic level, prostaglandins—particularly PGE2—translate these local inflammatory circuits into sustained pain sensitization and oxidative stress beyond the lesion microenvironment [135]. Proteomic analyses of lesion-like tissue reveal heightened inflammatory and angiogenic signaling, notably through protease-activated receptor pathways. Conversely, reduced expression of the serine protease inhibitor alpha1-antitrypsin augments Toll-like receptor responsiveness, perpetuating chronic inflammation at lesion sites [65,136].

Collectively, this evidence establishes endometriosis as a multisystemic inflammatory condition driven by complex interactions among immune, oxidative, metabolic, and neuroendocrine pathways that reinforce chronic inflammation and systemic dysfunction [135].

4.2. Alterations in Peripheral Blood: Soluble Cytokines, microRNAs, Inflammatory Mediators

Consistent with the immune-evasive cytokine networks previously described, endometriosis is associated with reproducible alterations in peripheral blood inflammatory profiles and the peritoneal fluid of affected individuals when compared with healthy controls [137,138]. Elevated IL-1β levels were reported in patients with endometriosis compared with controls [139,140], and a case–control study by Mu et al. [141] confirmed that higher plasma IL-1β levels are associated with an increased likelihood of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis. Similarly, IL-6 concentrations were found to be significantly higher in women with endometriosis compared to controls [140,142], highlighting its significant role in bridging innate and adaptive immunity through the stimulation of hepatic acute-phase protein synthesis. Higher TNF-α concentrations further support the association between persistent cytokine release and disease maintenance [137,143,144].

These cytokines stimulate hepatic production of acute-phase reactants, including C-reactive protein (CRP). Elevated CRP levels have been reported in women with endometriosis, supporting its potential value as a marker of systemic inflammation [145]. Other inflammatory mediators, including fibrinogen, homocysteine, IL-17, and IL-33, have also been implicated in amplifying this proinflammatory environment [146]. These findings indicate that cytokines and acute-phase reactants derived from endometriotic lesions spread into the systemic circulation, sustaining chronic immune activation [147].

Alterations in microRNA expression further contribute to this inflammatory profile. Benaglia et al. [148] identified increased expression of miR-27b, miR-520f, miR-17, and miR-34a in women with endometriosis, suggesting their role in regulating inflammatory gene networks and immune cell activity. Additional mediators detectable in circulation—including prostaglandins, VEGF, TNF-α, and NGF—reflect molecular spillover from ectopic lesions and contribute to systemic angiogenic and neuroinflammatory signaling [149].

4.3. Neuroimmune Links with Chronic Pain, Fatigue, and HPA Axis Dysfunction

Chronic pain represents one of the most disabling manifestations of endometriosis and is driven by profound neuroimmune alterations. In a syngeneic mouse model, Tauseef et al. [150] demonstrated extensive activation of microglia and astrocytes—evidenced by increased IBA1 and GFAP expression in cortical, hippocampal, thalamic, and hypothalamic regions—accompanied by elevated TNF and IL6 levels and behavioral indicators of hyperalgesia and reduced burrowing activity. Hippocampal microglial activation has been implicated in chronic pelvic pain, depression-like behavior, and sex-related differences in mood vulnerability [151,152,153,154], while thalamic microglia respond to systemic stressors and peripheral injury, suggesting that glial dysregulation contributes to central sensitization and emotional disturbances [155]. Clinically, pain—including dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic discomfort—remains the hallmark symptom, often extending beyond the pelvis [132]. Inflammatory mediators sustain nociceptive hypersensitivity and simultaneously modulate central circuits linked to anxiety and depression [156,157]. Elevated IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and CRP levels among women with mood symptoms further support the inflammatory hypothesis of depression [158], wherein cytokines alter neurotransmitter dynamics, neuroendocrine activity, and synaptic plasticity [159].

Fatigue, another disabling feature, may share biological roots with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Both conditions exhibit persistent immune activation, neuroinflammation, and impaired stress-axis regulation [160,161,162]. The chronic inflammatory milieu in endometriosis establishes systemic biological stress, contributing to central sensitization and neuronal hyperexcitability, which in turn drive widespread hyperalgesia, cognitive dysfunction, and exhaustion [163,164]. Sleep disruption—reported by nearly 70% of affected women—further intensifies inflammation and psychological distress [165], reinforcing this fatigue–inflammation link. Meta-analytic evidence confirms a bidirectional association between endometriosis and ME/CFS, suggesting overlapping neuroimmune pathways [166].

Finally, HPA axis dysregulation serves as a central integrator of these processes. Chronic pain and inflammation alter cortisol secretion patterns and stress responsivity, characteristic of depression and anxiety [167,168]. Peripheral cytokines can cross the blood–brain barrier or signal via vagal afferents, perturbing monoaminergic systems and inducing glucocorticoid resistance and oxidative stress [156,169]. Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels—associated with impaired neuronal plasticity and emotional regulation—further link inflammation to HPA axis dysfunction and mood pathology, supporting both the inflammatory and neurotrophic hypotheses of depression [170,171].

4.4. Emerging Insights into Gut–Endometrium Axis and Microbiome Involvement

The human gut microbiota, often described as a “hidden organ,” constitutes a highly complex community predominantly formed by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, alongside Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. This microbial ecosystem is essential for nutrient processing, synthesis of bioactive compounds, and the development and regulation of the immune system [172,173]. Early life establishment of commensal microbes is critical for maintaining immune tolerance and homeostasis, yet contemporary lifestyle factors—including industrialization, dietary changes, and decreased microbial exposure—have caused a reduction in microbial diversity and a proliferation of pathogenic species. This dysbiosis compromises immune surveillance and promotes persistent low-grade inflammation [174,175], which is increasingly recognized as a contributor to endometriosis pathophysiology through immune disruption, hormonal imbalance, and systemic inflammatory processes [172,176].

In endometriosis, gut microbiome disturbances are characterized by lower microbial diversity, a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, increased abundance of pro-inflammatory bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Clostridium, and a decrease in protective genera like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which maintain gut barrier integrity and regulate immune responses [67,177,178,179,180]. Dysbiosis can increase intestinal permeability, allowing translocation of bacterial endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into circulation. These molecules activate Toll-like receptor pathways, triggering pro-inflammatory signaling and elevating cytokines including IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, TGF-β, and IL-18, thereby promoting ectopic lesion formation and sustaining chronic inflammation [173,181]. Gut microbial β-glucuronidase activity, produced by Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Escherichia, and Lactobacillus, deconjugates estrogens, enhancing their reabsorption and contributing to a hyperestrogenic state that fosters lesion growth [182,183,184,185,186]. Animal studies support these mechanisms: mice with depleted microbiota exhibit reduced lesion growth, whereas overexpression of β-glucuronidase or dysbiosis increases lesion number, size, and macrophage infiltration [187,188]. Stress-induced changes in the gut microbiome further exacerbate inflammatory pathways through the gut–brain axis, amplifying lesion proliferation [189].

Recent studies have highlighted the gut–endometrium axis, whereby microbial metabolites, immune mediators, and estrogen regulation from the gut influence the endometrial microenvironment [190]. Dysbiotic patterns in the endometrial microbiome, including depletion of Lactobacillus and overgrowth of Atopobium, Fusobacterium, and Gardnerella, promote inflammation and estrogen-driven proliferation, with implications for estrogen-dependent conditions like endometrial carcinoma [191,192,193,194,195,196]. Functional analyses also indicate alterations in lipid metabolism pathways, such as fatty acid synthase, regulated by estrogen and progesterone, which drive endometrial cell proliferation and may serve as therapeutic targets [197]. Overall, these findings emphasize the multifactorial influence of the gut microbiome on immune modulation, systemic inflammation, hormonal balance, and endometrial tissue regulation, positioning the gut–endometrium axis as a promising focus for microbiome-targeted diagnostics and therapies in endometriosis [198].

5. Molecular Biomarkers: Tracking the Dialog

5.1. Circulating microRNAs, lncRNAs, and Extracellular Vesicles in Serum and Plasma

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which exceed 200 nucleotides and modulate gene expression through chromatin remodeling, RNA stability regulation, and intracellular signaling, have been increasingly detected in circulating blood components of endometriosis patients and are emerging as promising non-invasive biomarkers. Several lncRNAs—including H19, HOTAIR, MALAT1, MEG3-210, and NEAT1—have been reported to show altered expression in serum or plasma, reflecting their involvement in endometriosis pathophysiology [199,200]. Among them, elevated circulating HOTAIR has been associated with increased HDAC1 expression and activation of STAT3-dependent inflammatory pathways through the HOTAIR–miR761–HDAC1 regulatory axis, promoting cytokine-driven inflammation [201]. Network analyses further identified H19 and NEAT1 as central regulatory hubs due to their multiple predicted miRNA binding sites, supporting previous evidence linking these lncRNAs to proliferation and migration of endometrial stromal cells via insulin-like growth factor signaling, with H19 significantly reduced in the eutopic endometrium of affected patients [202,203]. Plasma transcriptome profiling revealed 210 significantly dysregulated lncRNAs in endometriosis, with LINC01569, RP3-399L15.2, FAM138B, and CH507-513H4.6 decreased and RP11-326N17.2, KLHL7-AS1, and MIR548XHG increased compared to healthy controls [204]. Parallel analyses of circulating miRNAs have demonstrated alterations linked to cell migration and proliferation, including reduced serum levels of miR-193 and miR-374 [205]. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) isolated from endometriotic lesions and the peripheral blood of patients carry distinct miRNA signatures, such as let-7a, miR-23a, miR-143, miR-320a, miR-30d-5p, miR-16-5p, miR-27a-3p, and miR-375, which are consistent with their established roles in endometriosis pathogenesis [206,207,208]. Consistently, Ravaggi et al. [209] detected significant upregulation of circulating miR-1249, miR-145-5p, miR-486-5p, miR-485-3p, and miR-26a-5p, alongside downregulation of miR-23a-3p. These findings suggest that dysregulated circulating lncRNAs, miRNAs, and EV-derived miRNAs participate in systemic molecular processes associated with endometriosis, providing a basis for continued exploration of their clinical relevance.

5.2. Peritoneal Fluid Proteomics and Systemic Inflammatory Profiles

Proteomic investigations of both peritoneal fluid and peripheral blood demonstrate distinct immune-inflammatory disturbances in women with endometriosis, indicating that the condition is associated with both localized and systemic activation of pathological pathways. Elevated levels of key inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), have been consistently observed in affected individuals when compared with controls, supporting the presence of a heightened inflammatory state that is not restricted to the peritoneal cavity [76,210,211,212]. In a comprehensive plasma proteomic analysis, Sasamoto et al. [210] reported increased expression of proteins associated with immune activation, oxidative stress, iron regulation, and angiogenesis, including protein kinase C zeta type, ferritin, hepcidin, peroxiredoxin-6, ephrin-B3, angiopoietin-related protein 3, RNA-binding protein 39, gremlin-1, hepatocyte growth factor, and cathepsin G. Among these, ferritin and hepcidin were prominently upregulated, implicating altered systemic iron homeostasis, while angiogenesis-related factors such as angiopoietin-related protein 3, gremlin-1, and hepatocyte growth factor underscored the role of vascular remodeling in disease progression. Parallel analysis of peritoneal fluid, which provides direct insight into the local environment of endometriotic lesions, has further illuminated disease-associated proteomic alterations. Janša et al. [213] identified 16 proteins with differential abundance in endometriosis compared to infertility controls, including the proinflammatory calcium-binding proteins S100A8/9, scavenger receptor cysteine-rich type 1 protein M130, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1). These findings reflect an integrative network of inflammatory and proteomic alterations that shape the pathophysiological environment in endometriosis.

5.3. Integration of Omics-Based Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis and Patient Stratification

The integration of multi-omics technologies is emerging as a transformative approach for the early diagnosis and clinical stratification of endometriosis, addressing current limitations related to delayed detection and heterogeneous clinical presentation. Genomic studies have identified susceptibility loci such as WNT4, PGR and GREB1, enabling the development of polygenic risk scores that may predict disease predisposition [214], while epigenomic analyses have revealed aberrant DNA methylation and dysregulated non-coding RNAs that contribute to altered hormonal responses, inflammation, and aberrant cell proliferation [28,115,215]. Transcriptomic profiling, including circulating microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs in plasma, endometrial tissue and peritoneal fluid, has demonstrated substantial diagnostic potential due to their stability and disease-specific expression patterns [216]. Proteomic analyses further complement these findings by identifying dysregulated proteins in serum and peritoneal fluid related to immune activation, angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodeling, including alterations in cytokines, tumor necrosis factor signaling pathways, S100 proteins, and TIMP family members [217]. Likewise, metabolomic studies have characterized distinct metabolic fingerprints associated with oxidative stress, estrogen metabolism and immune dysregulation, suggesting their utility in distinguishing endometriosis from other gynecologic pathologies [218]. The integration of these omics layers through systems biology and network-based analytical approaches allows for the identification of biomarker panels rather than isolated markers, enhancing diagnostic sensitivity and specificity [219,220]. Machine learning and artificial intelligence are increasingly employed to combine genomic, proteomic, metabolomic and microbiomic datasets, enabling the classification of patients into biologically meaningful subgroups, such as inflammatory-dominant, fibrotic or hormone-resistant phenotypes [221]. This stratification has critical implications for predicting disease progression, assessing infertility risk and guiding personalized therapeutic strategies. Importantly, the incorporation of microbiome data, particularly alterations in the gut and reproductive tract microbial communities, further refines patient profiling and may offer novel non-invasive diagnostic tools [222,223]. While the clinical translation of multi-omics biomarkers is still challenged by variability in sample collection protocols and the need for validation in large cohorts [224], ongoing advances in integrative platforms and liquid biopsy technologies are paving the way for dynamic biomarker models capable of monitoring disease activity and recurrence in real time [225,226]. Collectively, multi-omics integration represents a fundamental shift toward precision medicine in endometriosis, offering the potential to revolutionize disease detection, classification and individualized treatment selection.

6. Therapeutic Opportunities in a Systemic Disease

6.1. Limitations of Conventional Hormonal Therapies

Hormonal therapy continues to play a central role in the management of endometriosis, though its long-term effectiveness and patient adherence are constrained by several limitations. Progestins, such as dienogest, norethindrone acetate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, cyproterone acetate, Implanon, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems, act by suppressing gonadotropin secretion, inducing decidualization and endometrial atrophy, and modulating local immune-inflammatory responses, including decreases in IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and TNF-α-driven cell proliferation [227,228]. Nevertheless, approximately one-third of patients experience progesterone resistance, commonly linked to reduced expression of progesterone receptors (PGR) in endometriotic tissue, which substantially reduces the therapeutic effect of progestins [229]. Dienogest has demonstrated clinical benefits in alleviating pain and reducing lesion size, even in deep infiltrating endometriosis and adenomyosis, though its use can be complicated by initial bleeding irregularities and temporary decreases in bone mineral density, especially in adolescents treated for over one year [230,231]. Other progestins often require higher, sometimes unapproved, doses to achieve comparable effects, while depot formulations like MPA or norethisterone enanthate, although efficacious, are associated with a higher risk of adverse events such as thrombosis, bone loss, and systemic hypoestrogenic symptoms [232].

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) are effective in controlling dysmenorrhea by inhibiting ovulation and stabilizing the endometrium, yet their impact on non-menstrual pelvic pain or dyspareunia is limited, and early use has been associated with increased risk of deep infiltrating endometriosis [233]. Extended-cycle regimens, vaginal rings, and other combined estrogen–progestin preparations are generally well-tolerated, but limitations remain due to contraindications linked to the estrogen component and incomplete symptom control [228]. The LNG-IUS provides targeted therapy with minimal systemic side effects and sustained lesion suppression, particularly after surgery for rectovaginal endometriosis or adenomyosis; however, it is not FDA-approved for endometriosis-related pain and discontinuation may occur due to irregular bleeding, depression, or weight gain [234].

GnRH agonists and antagonists efficiently reduce estrogen levels and lesion stimulation, but their utility is limited by pronounced hypoestrogenic effects—hot flashes, sleep disturbances, vaginal dryness, mood changes, bone loss—and high recurrence rates, with up to 50% of patients experiencing symptom relapse within six months of therapy cessation [235]. Emerging therapies, including linzagolix and relugolix combination therapy, have demonstrated rapid and sustained improvement in dysmenorrhea, non-menstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia, while add-back therapy helps mitigate hypoestrogenic side effects; however, long-term safety, adherence, and cost considerations require further study [236,237,238]. Across all hormonal options, common adverse effects—bloating, weight gain, acne, breast tenderness, libido changes, irregular bleeding, fatigue, and, less frequently, mood disturbances—pose challenges for adherence, emphasizing the importance of individualized treatment planning [239].

Finally, endometriosis recurrence, ranging from 10% to 80% depending on surgical completeness and disease severity, highlights the need to integrate pharmacological and surgical interventions, as monotherapy rarely eradicates microscopic disease [233]. While hormonal treatments offer substantial symptom relief and improved quality of life, their variable efficacy, progesterone resistance, hypoestrogenic side effects, bleeding irregularities, and risk of recurrence necessitate careful monitoring, patient counseling, and tailored management strategies to optimize outcomes.

6.2. Promising Molecular Targets: Angiogenesis Inhibitors, Immune Modulators, Epigenetic Regulators

Current research aims to identify drugs that selectively modulate the hormonal and immunological microenvironment of endometriotic lesions to suppress proliferation, promote apoptosis, and normalize aberrant invasion and angiogenesis (Table 1) [240]. Among angiogenesis-targeted therapies, VEGF is a central mediator, with elevated levels observed in peritoneal fluid and tissue, making it a primary target [241,242]. The MMP complex—including fibroblast growth factor, MMP2, and MMP9—also contributes to invasion and metastatic-like dissemination of endometrial cells and is considered a therapeutic target [243]. Dopamine and dopamine receptor-2 agonists reduce neoangiogenesis by promoting VEGF receptor endocytosis, supporting their potential as antiangiogenic agents [244,245]. Similarly, RAS pathway inhibitors such as ACEIs and ARBs attenuate VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, suppress inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α, and reduce fibrosis and adhesion formation, potentially improving reproductive outcomes [246,247].

Epigenetic regulators are also key targets, as chronic inflammation induces DNA hypermethylation affecting HOXA10, a transcription factor linked to endometrial receptivity and progesterone receptor expression [248]. The DNA methylation inhibitor 5′-aza-deoxycytidine (AZA) reverses HOXA10 hypermethylation in vitro, providing mechanistic support for future therapies [249], although currently approved agents remain toxic for fertility-seeking patients [248]. Progesterone receptor gene methylation further contributes to aberrant silencing, highlighting the potential of demethylating agents and histone deacetylase inhibitors [250].

Elevated ROS due to impaired detoxification pathways sustains proliferative signaling [251], while proliferative cascades such as RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR can be inhibited by cannabinoid agonists in deep nodular lesions, underscoring the convergence of multiple growth-promoting pathways [247]. EMT contributes to invasive phenotypes in ovarian, peritoneal, and deep-infiltrating endometriosis, with partial EMT confirmed by Konrad et al. [252] and estrogen-associated EMT markers supported by Liu et al. [253], suggesting pharmacological inhibition of EMT regulators as a potential strategy.

Autophagy-apoptosis pathways represent additional targets; silencing cirRNA promotes apoptosis of ectopic endometrial cells, and SCM-198, a synthetic pseudoalkaloid, reverses a hypo-autophagic state induced by increased ERα and decreased PR-B expression, restoring autophagy and promoting apoptosis [254].

Targeting inflammatory and immune pathways remains critical due to the overproduction of prostaglandins, cytokines, and other mediators. Nonselective NSAIDs inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 and provide symptomatic relief, while TNF-α inhibitors have been explored for disease modulation [255]. Aberrant immune regulation, including NK cell inhibition and macrophage hyperactivation, represents actionable targets [256,257,258], and PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors may restore immune tolerance and enhance anti-endometriotic responses [259,260,261]. TGF-β, which suppresses NK cell cytotoxicity and other immune functions, is another potential target [262,263]. Furthermore, strategies restoring immune surveillance and modulating ribosome biosynthesis (affecting macrophage proliferation via mTOR/PI3K and RNA polymerase I inhibition) have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects in preclinical models [247,264].

Finally, RAS-targeting compounds also constitute an avenue for continued investigation and development of novel therapeutic approaches for endometriosis. These agents act on key mechanisms of disease progression—angiogenesis, inflammation, and fibrosis—thereby limiting lesion growth, reducing pain, and minimizing adhesion formation, which underscores their promise as non-hormonal therapeutic options for endometriosis management [246].

Table 1.

Agents Investigated as Inhibitors of Molecular Pathways in Endometriosis. This table lists agents, their molecular targets, and the pathways through which they modulate inflammation, cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis in endometriotic lesions. Abbreviations: IL: Interleukin; MCP-1: Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1; NF-κB/NF-kB: Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; mRNA: Messenger Ribonucleic Acid; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; VEGFR2: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2; E-cadherin: Epithelial cadherin; N-cadherin: Neural cadherin.

Table 1.

Agents Investigated as Inhibitors of Molecular Pathways in Endometriosis. This table lists agents, their molecular targets, and the pathways through which they modulate inflammation, cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis in endometriotic lesions. Abbreviations: IL: Interleukin; MCP-1: Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1; NF-κB/NF-kB: Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; mRNA: Messenger Ribonucleic Acid; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; VEGFR2: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2; E-cadherin: Epithelial cadherin; N-cadherin: Neural cadherin.

| Inhibitor | Target Proteins | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Resveratrol [265] | IL-6, IL-1B, MCP-1 | Reduces the expression of inflammatory markers in the eutopic endometrium and, to a greater extent, in the ectopic endometrium. |

| Curcumin [266] | NF-kB, cytokine production | By inhibiting NF-κB signaling and lowering cytokine levels, preclinical studies indicate its potential to reduce lesion size and associated pain. |

| Genistein [267] | NF-kB, TNF- α, IL-6, IL-8 | Suppresses the expression of inflammatory mediators and reduces cell proliferation. |

| Leflunomide [248] | NF-kB | Inhibits proliferative activity in endometrial cells. |

| Nobiletin [268] | NF-kB, IL-6, IL-1B | Mitigates lesion growth and pain through inhibition of cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and excessive inflammation. |

| Ginsenoside [269] | NF-kB, protein kinase B | Limits endometrial stromal cell viability via inhibition of NF-κB signaling. |

| Dienogest [270] | NF-kB, TNF- α, IL-8 | Reduces IL-8 expression by inhibiting TNF-α–mediated activation of NF-κB. |

| Thalidomide [271] | NF-kB, TNF- α, IL-8 | Reduces IL-8 expression at both the microRNA and protein levels by inhibiting TNF-α–induced NF-κB activation. |

| Tocilizumab [272] | IL-6 | Monoclonal anti-IL-6 antibody demonstrated to induce regression of lesions. |

| Quinagolide [273] | VEGF/VEGFR2 pathway | Demonstrated to markedly reduce lesion size, possibly through modulation of angiogenesis. |

| Fucoidan [274] | Snail and Slug, Notch | Inhibits the growth of endometriotic lesions and triggers apoptosis through anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. |

| Pyrvinum pamoate [275] | IL-6, IL-8 | Downregulates IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expression. |

| Isoliquiritigenin [276] | Snail, Slug, E-cadherin, N-cadherin | Attenuates the inflammatory response while inducing apoptosis. |

| 3,6-dihydroxyflavone [277] | Notch signaling pathway | Inhibits cell migration through downregulation of Notch and associated downstream molecules. |

| Melatonin [278] | Snail, Slug, Notch homolog, E-cadherin, N-cadherin | Reduces endometriotic lesion growth and invasiveness by inhibiting estradiol and Notch signaling. |

6.3. Advances in Targeted Delivery Systems and Nanotherapeutics

Current therapeutic advances in endometriosis are increasingly directed toward targeting dysregulated molecular and immune pathways rather than relying solely on hormonal suppression. Regulatory miRNAs such as let-7b, miR-125, and miR-155 modulate lymphocyte activity and inflammatory signaling, with let-7b shown to reduce lesion size in macaque models [243]. Similarly, bentamapimod, a c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor, promotes lesion regression without affecting menstrual cyclicity. Other promising strategies include targeting MAPK/ERK, NF-κB, HIF-1α, and MMP-2/-9, which are central to cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis [279]. Immunomodulatory approaches, including TNF-α inhibitors, immune checkpoint blockade, siRNAs, and miRNA mimics, are advancing through preclinical development and may enable precision medicine guided by molecular biomarkers [175,248,280].

As part of this emerging therapeutic landscape, nanotechnology offers one of the most innovative and clinically promising strategies, enabling selective delivery of therapeutic agents directly to endometriotic lesions [281,282]. Nanoparticles accumulate at disease sites via the enhanced permeability and retention effect and can be engineered to actively target receptors such as VEGFR2 (KDR) and EphB4, which are overexpressed in endometrial tissue [280]. Polymeric nanocarriers like Poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ε-caprolactone) facilitate controlled drug release, while magnetic nanoparticles like KDR-Manganese-containing nanoparticles combine imaging capabilities with magnetothermal therapy to destroy lesions. Gold nanoshells such as hollow gold nanoshells (HAuNS) and its derivates utilize near-infrared light to generate localized heat and induce apoptosis of endometriotic cells [283]. Small interfering RNA-loaded nanoparticles paired with cell-penetrating peptides enable gene-targeted interventions that suppress key pathogenic pathways [284,285]. Theranostic platforms, such as SiNc-PEG-PCL nanoparticles, allow simultaneous lesion detection and photothermal ablation, while Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid -based systems co-loaded with doxycycline and Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibit angiogenesis and oxidative stress in animal models [240]. Incorporating agents like danazol or Elagolix into nanoparticle formulations further enhances drug bioavailability and reduces systemic toxicity [280]. Although additional clinical validation is required, nanotherapeutics represent a significant step toward highly targeted, effective, and personalized treatment strategies for endometriosis [283].

6.4. Potential of Immunotherapy and Early Systemic Intervention

Emerging strategies for immunotherapy and early systemic intervention in endometriosis have highlighted mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), particularly endometrial MSCs (eMSCs), due to their self-renewal, multipotency, and potent immunomodulatory properties [286,287]. MSCs can be isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue, placenta, and endometrium, with eMSCs being especially relevant given their physiological role in endometrial regeneration and tissue homeostasis [288,289]. In the context of endometriosis, however, MSCs derived from ectopic lesions exhibit altered phenotypes, including upregulation of inflammatory (IL-6, TNF-α) and angiogenic (VEGF) genes, enhanced proliferation and migration, and dysregulated immune interactions, potentially facilitating ectopic implantation and contributing to ovarian carcinogenesis [286,289,290]. Mechanistically, MSCs exert immunomodulatory effects through exosome-mediated delivery of cytokines and miRNAs, which suppress effector T cells and pro-inflammatory macrophages while promoting regulatory cells such as B regs, thereby restoring immune homeostasis [291,292]. Moreover, MSCs inhibit angiogenesis via the miRNA-21-5p/TIMP3/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and downregulation of VEGF, while simultaneously promoting endometrial repair and improving fertility outcomes [4,288,290,292,293]. Preclinical models demonstrate reductions in lesion size, inflammatory cytokines, and angiogenic markers following MSC therapy [286,289]. Although initial clinical reports suggest improvements in fertility and symptom relief, further optimization of MSC source, administration protocols, long-term safety, and development of exosome-based or genetically modified approaches are required to maximize therapeutic efficacy.

7. The Case for a Systems Medicine Approach

7.1. Proposal to Reconceptualize Endometriosis as a Systemic Inflammatory Disorder with Gynecologic Expression

Growing evidence supports a shift toward viewing endometriosis as a systemic inflammatory condition, in which gynecologic lesions represent one aspect of a broader, immune-mediated pathology [147,294]. Rather than being confined to pelvic sites, the condition induces body-wide inflammatory activity, demonstrated by elevated serum concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [119], alongside profound alterations in both local and systemic immune responses [295]. Circulating microRNAs further contribute to this systemic inflammatory cascade; specifically, dysregulation of miRNA 125b-5p and Let-7b-5p promotes enhanced cytokine production by macrophages at distant sites, indicating communication between lesions and peripheral immune compartments via molecular signaling networks [119]. The systemic nature of the disease is also reflected in metabolic disturbances, including altered adipocyte and hepatic function associated with low body mass index, widespread neuroimmune alterations driving central sensitization and mood disorders such as fatigue, anxiety, and depression [296], chronic inflammatory-like conditions in non-reproductive tissues [297], and a predisposition to immune-mediated diseases [127]. Furthermore, systemic inflammation in endometriosis is linked with increased cardiovascular risk, malignancy, and a hypercoagulable state [147,298]. Extra-pelvic manifestations, including thoracic endometriosis, undermine the idea that retrograde menstruation alone accounts for disease development and instead point to mechanisms such as cellular dissemination and immune system activation [299]. These complex, system-wide effects, together with high comorbidity rates and persistent lack of a definitive cure, emphasize that endometriosis is fundamentally a systemic condition requiring integrated therapeutic strategies involving multiple specialties rather than exclusively localized surgical management. Reframing the disease in this way provides a foundation for identifying novel molecular targets and developing treatments that modulate systemic inflammatory and immune pathways rather than addressing only local manifestations [294].

Clinically, reframing endometriosis as a systemic inflammatory disorder has direct implications for diagnostic pathways. This perspective supports the incorporation of circulating molecular markers—including cytokines, microRNAs, extracellular vesicles, and proteomic signatures—into non-invasive diagnostic strategies to complement or potentially reduce reliance on surgical confirmation [294]. In addition to pelvic pain and infertility, clinical suspicion should encompass systemic manifestations such as fatigue, mood alterations, metabolic disturbances, and cardiovascular risk indicators, thereby broadening diagnostic vigilance beyond gynecologic symptoms alone. Multidisciplinary assessment involving gynecology, immunology, neurology, cardiology, and mental health specialists may therefore be warranted in selected patients, particularly those exhibiting significant systemic involvement [147]. Such an approach aligns with emerging evidence that early recognition of systemic disease features may enable earlier diagnosis, improved monitoring, and more comprehensive patient care.

7.2. Systems Biology Tools: Network-Based Analyses, Transcriptomics, Proteomics, and Integrative Multi-Omics

Systems biology approaches have become pivotal in advancing the understanding of endometriosis, a heterogeneous and multifactorial disorder characterized by complex interactions between hormonal signaling, immune dysregulation, inflammatory mediators, stromal remodeling, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis [300]. Unlike traditional reductionist analyses that focus on single genes or pathways, system-level methodologies enable the identification of interconnected molecular networks and disease-specific patterns that underlie lesion establishment, chronic inflammation, and symptom heterogeneity [301]. Network-based analyses, including gene co-expression networks and protein–protein interaction models, have revealed central hub genes and signaling pathways that act as regulatory drivers of the disease, such as the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, NF-κB, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways [302]. These analyses have also demonstrated molecular convergence between endometriosis and other chronic inflammatory or autoimmune conditions, highlighting shared pathogenic mechanisms and suggesting potential opportunities for therapeutic repurposing [303,304].

Transcriptomic profiling using microarrays and RNA sequencing has revealed distinct gene expression signatures in both eutopic and ectopic endometrium, including dysregulation of genes associated with extracellular matrix remodeling, immune activation, angiogenesis, hypoxia response, and neural infiltration [305]. Importantly, transcriptomic studies have identified molecular endotypes that differentiate lesion subtypes and disease stages, providing insight into inter-individual variability in symptom severity and treatment response [306]. Proteomic analyses have further expanded this understanding by identifying alterations in the protein landscape of endometrial tissue, peritoneal fluid, and circulating blood, particularly involving cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and matrix metalloproteinases [213]. These protein-level changes contribute to lesion survival, immune evasion, and nociceptive signaling, while also providing promising biomarker candidates for non-invasive diagnostics.

The integration of multi-omics approaches—combining genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiome data—has allowed the construction of comprehensive molecular profiles that capture the dynamic interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental factors [307,308]. Multi-omics integration using network-based algorithms and machine learning techniques enables the stratification of patients into molecular subgroups, facilitates the prediction of therapeutic responsiveness, and identifies novel targets for precision medicine [309]. Together, systems biology tools are transforming endometriosis research by elucidating disease mechanisms at a network level, uncovering novel biomarkers, and paving the way toward personalized therapeutic strategies.

Beyond mechanistic insight, systems biology approaches provide an opportunity to develop clinically meaningful patient stratification frameworks. Integrative multi-omics analyses increasingly support the existence of distinct biological endotypes, such as inflammation-dominant, immune-dysregulated, hormone-resistant, angiogenesis-driven, neuroimmune-pain-dominant, and fibrosis-predominant phenotypes [111,145,219]. These subgroups may differ in symptom profiles, disease progression, comorbidity risk, and therapeutic responsiveness, highlighting the need for tailored management rather than uniform treatment strategies. Stratification based on molecular signatures, combined with clinical features and imaging findings, holds potential to guide prognosis estimation, refine therapeutic decision-making, and support the design of precision-based clinical trials that better capture disease heterogeneity [219].

7.3. Pathway Toward Precision Medicine: Tailoring Treatments Based on Molecular Endotypes

Over the last twenty years, the therapeutic landscape of endometriosis has evolved from generalized hormonal suppression and surgical excision to advanced approaches that prioritize individualized treatment based on the molecular and cellular characteristics of the disease [310]. This transformation is grounded in the recognition that endometriosis is not a uniform condition, but rather a collection of biologically distinct endotypes characterized by unique genetic, immunological, and epigenetic profiles that dictate how patients respond to therapy [311,312,313]. In this emerging framework of precision medicine, three innovative strategies have gained prominence: targeted molecular agents, nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems, and stem cell–based regenerative therapies. Targeted therapies aim to selectively inhibit aberrant signaling pathways implicated in lesion survival and inflammation, thereby offering higher specificity and reduced systemic side effects compared to traditional hormonal interventions [282]. Nanoparticles further enhance therapeutic precision by enabling localized drug delivery to endometriotic lesions and improving pharmacokinetic properties, while also serving as carriers for bioactive molecules secreted by stem cells [314,315]. Stem cell therapies introduce the possibility of not only suppressing pathological processes but also restoring normal tissue architecture and modulating immune dysregulation [316]. Importantly, these therapeutic modalities are not isolated in their application; rather, they may be combined in synergistic regimens—for instance, nanoparticles can be engineered to carry targeted drugs or stem cell–derived factors, thereby amplifying treatment efficacy and potentially decreasing the need for surgical intervention [317]. Such integrative, biology-driven strategies represent a model for truly personalized care, where treatment is precisely aligned with a patient’s unique molecular endotype [282].