Abstract

Monogenean parasite infestation in fish leads to economic losses in aquaculture, representing a veterinary challenge and an environmental concern. The common administration procedures of anthelmintics to treat monogeneans in fish have low efficiency and diverse drawbacks. In this study, we produced a nanoparticle using chitosan and alginate, biodegradable and biocompatible polysaccharides, as an oral drug delivery material of albendazole anthelmintic for parasite-infected fingerlings of Nile tilapia. The molecular interaction between the biopolymers was optimized and characterized by titration calorimetry. Freeze-drying of nanoparticles resulted in a fine powder with a particle size in the order of 400 nm. The nanoparticles provided 98% encapsulation of albendazole and sustained delivery with predominantly Fickian diffusion. The palatability of the nanopar-ticle formulation facilitated the oral administration of albendazole. The treatment of 100% prevalence of monogeneans was effective with a six-day dosage providing a total of 915 mg/kg b.w. of drug, resulting in total parasite clearance after 10 days from the treatment beginning, evidenced by microscopy analysis, and no mortality occurred. Therefore, molecular interactions between biofriendly polyelectrolytes yielded albendazole-carrying nanoparticles for high-efficiency parasite treatment in fish farming.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, human and veterinary medicine benefit from a wide range of treatments and medications for most known diseases and infections [1,2,3,4,5]. In the veterinary field, major health concerns are associated with animal farming for protein production, driven by increasing human consumption of meat [6,7,8]. The high demands are leading to the intensification of animal farming and breeding, with the fishing industry representing one of the fastest-growing worldwide protein markets [9].

In this context, intensive fish production necessitates constant and efficient health control to optimize production costs and profits, while adhering to regulatory criteria to ensure safe human consumption [10,11]. In fact, there is a direct relationship between the health of farmed animals and the health of consumers, where the transmission of pathogens can pose a threat to public health [12,13].

Parasite infestations in fish represent an increasing threat to fish farming. Indeed, the global aquaculture production has suffered economic losses estimated to be 1 to 10 billion USD annually due to problems related to outbreaks of parasitic and bacterial diseases [14]. However, the economic impacts are not well documented, and comparing them across species and diseases is difficult [15]. Among helminths that parasitize freshwater fishes, monogeneans present a high risk for finfish aquaculture industries, causing expressive economic losses associated with reduced growth, morbidity, and mortality in fish farming around the world, with reported mortalities of the entire fish stock in several cases [16,17,18,19].

Albendazole is a benzimidazole hydrophobic drug known for its action as an anthelmintic for the treatment of human and animal parasite infections. It acts by preventing the worms from absorbing sugar (glucose), which depletes their energy and ultimately kills them. Albendazole has been administered to fish in therapeutic baths [20], mixed with the commercial ration or pellets [21], or via intragastric gavage [22,23]. The drug was studied as an anthelmintic for parasite infections, such as monogenean [24], acanthocephalans [25], digenean trematode [26], and in a variety of wild or farmed fish, such as rainbow trout, tilapia, and Atlantic salmon [27], tambaqui [28], carp [29], and yellow perch [30].

However, the administration of hydrophobic drugs in the aquatic environment is not straightforward, frequently leading to low drug intake and high losses at the bottom of tanks or aquariums, or retention in the water filter system. The administration of albendazole mixed in the ration or in nutritional additives may impact the palatability, resulting in low intake and water pollution. The administration by gavage is evidently unfeasible on a large scale, resulting in a high-cost treatment. Therapeutic baths generally require the use of solvents for drug dispersion, such as ethanol, methanol, and dimethyl sulfoxide, which cause toxicity, side effects, and high levels of water pollution [31,32,33]. Therefore, the majority of current administration procedures of hydrophobic anthelmintic drugs in fish present moderate to high drawbacks and reduced efficacy, leading to unreliable perspectives of practical application.

The development of human and veterinary medicine has been driven by the great expansion of nanotechnology in recent decades. In approaching molecular sciences to nanoscale manipulation and production of functional materials, nanomedicine has provided new solutions ranging from prevention and diagnosis to treatment of diseases, with highly improved efficiency [34,35,36].

Therefore, the evolution of traditional procedures for disease prevention and treatments in aquaculture can also rely on modern nanotechnology approaches [37,38,39]. In this study, we produced a polysaccharide nanoparticle to optimize the administration of albendazole in monogenean-infected cultured fingerlings of Nile tilapia. The biomacromolecules chitosan and alginate, sourced from the aquatic marine environment, were combined in a coacervated and freeze-dried formulation with high entrapment of albendazole, providing an efficient and effective oral drug delivery material for veterinary application in aquaculture.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Thermodynamics of Nanoparticle Production

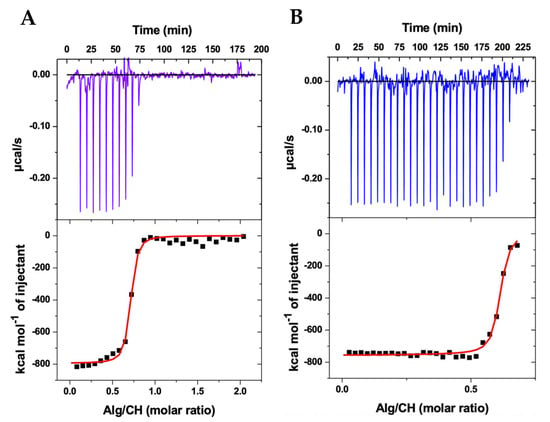

Figure 1 shows the results for ITC. The experiment simulated the preparation of the nanoparticles. The upper panels show the heat released (μcal/s) as a function of time at every injection of alginate solution into the cell containing the chitosan solution at the same temperature (25 °C). Every exothermic down-pointing peak represents the energetic variation when alginate comes in contact with chitosan. At every alginate injection, part of the chitosan concentration is “consumed” as the complexation between the oppositely charged polyelectrolytes results in colloidal assemblies, as schematically represented in Figure 2. When the concentration of chitosan in the ITC cell decreased, as it was complexed with incoming alginate, the down-pointing peaks decreased in intensity, and when all chitosan was complexed with alginate, only alginate’s diluting heat variations were recorded, and they were subtracted from the heats of complexation.

Figure 1.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) results of the thermodynamic interaction between alginate (Alg) and chitosan (CH) during the complex coacervation producing nanoparticles in acetate buffer (pH 4.5) at 25 °C in the presence (A) and absence (B) of albendazole.

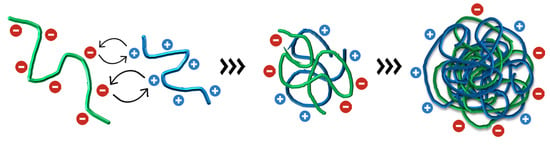

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the electrostatic interaction between negatively charged alginate and positively charged chitosan, which produces a random polyelectrolyte assembly and, after increasing the concentration of the biopolymers, results in the final coiled colloidal nanoparticle with negative and positive surface charges.

The lower panels show the respective integration of the peaks, in kcal/mol of alginate, as a function of the alginate/chitosan molar ratio, thus representing the integrated heats of the alginate–chitosan complexation during the production of the nanoparticles. The integrated heats represent the sum of all energetics involved in the interaction between alginate and chitosan. Since alginate is a polyanion (ionized carboxyl groups) and chitosan is a polycation (protonated amino groups), the electrostatic interaction between the opposite charges (Figure 2) may be considered as the main driving force for the complexation [40,41]. Additionally, hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions, the breaking of hydrogen bonds, the formation of new hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, conformational changes of both biopolymers during interaction, and water molecules release during complexation—all energetics involved in these phenomena may contribute as secondary forces during the polyelectrolytes’ complexation into colloidal nanoparticles [42,43,44]. The sum of all contributions is contained in the integrated heats.

Considering the polyanion and polycation as individual interacting entities, the single set of binding sites model was applied to the integrated heats [40], providing the red sigmoidal curves shown in Figure 1 and thus determining the stoichiometric relation N between alginate and chitosan, the equilibrium constant K, and the enthalpic variation ΔH of the complexation. The Gibbs free energy was determined as ΔG = −RT ln(55.55K), where ΔG is defined as the standard state of mole fraction and 55.55 accounts for the concentration of water [45]. The entropic gain was calculated using TΔS = ΔH − ΔG. The results for the complete thermodynamic scenario of the nanoparticle production are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic results characterizing the interaction between alginate (Alg) and chitosan (CH) in the presence and absence of albendazole (Alb) in the production of the colloidal nanoparticles at 25 °C, obtained from ITC results.

As shown in Table 1, the stoichiometric ratio N between alginate and chitosan, at the saturation of binding sites, is approximately 0.6 for both nanoparticles containing and not containing the albendazole drug. Hence, around 0.6 alginate monomer per chitosan monomer, or inversely 1/N∼1.7 chitosan monomer per alginate monomer at saturation, effectively provides the stoichiometry for the nanoparticle formation at the obtained equilibrium constant K. Indeed, the high values obtained for K represent the strength of the interaction between the polyelectrolytes, which was slightly higher in the absence of albendazole, although in the same order of magnitude, evidencing a strong tendency of the polyelectrolytes’ assembly and nanoparticles’ formation (Figure 2).

Of notice, despite the lower concentration of alginate solution applied in the ITC experiment in the absence of albendazole, the titration resulted in additional exothermic peaks, as shown in Figure 1B, evidencing that in the end a similar proportion (N) between alginate and chitosan is maintained not only when comparing the presence and absence of albendazole, but also when comparing different initial concentrations of the polyanion solution. This outcome further confirms the reproducibility of the nanoparticle production thermodynamics.

The enthalpic variation ΔH obtained in each experiment (Table 1) reflects a strong but similar exothermic process. In addition, almost equal and negative Gibbs energy variations ΔG evidence a thermodynamically favored polyelectrolyte assembly, with a state of lower free energy, thus resulting in the nanoparticle formation, which should therefore be considered as an energetically stable condition [46].

Finally, the entropic contribution TΔS shows almost equal values for CHAlg-Alb and CHAlg, reflecting the condensation of both assembling systems with negative entropy, which may be attributed to the effective electrostatic binding between the oppositely charged biopolymers. Interestingly, other energetics providing entropic increase, e.g., the breaking of hydrogen bonds and water release during the macromolecules’ assembly, were not sufficient to provide a positive entropy, further evidencing that the assembling process is highly energetically favored. These results confirm previous studies on thermodynamic interactions between chitosan and alginate [40,41].

As a matter of fact, the similar thermodynamics on the nanoparticles’ assembly in the presence and absence of albendazole overall evidence that the drug does not prevent interactions between the polyelectrolytes. Hence, the nanoparticles are equally obtained, and the feasibility of producing CHAlg nanoparticles containing albendazole is demonstrated.

2.2. Colloidal Features of the Nanoparticles

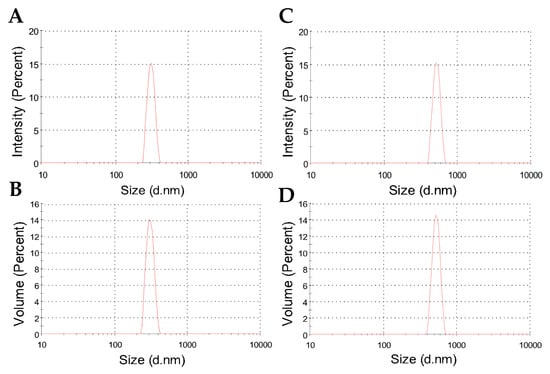

Figure 3 shows typical results for the hydrodynamic size distribution of nanoparticles dispersed in water. As evidenced by the curves, a relatively narrow particle size distribution was characterized for both nanoparticles with and without albendazole. Additionally, when comparing the size distribution in terms of intensity and volume percent, the DLS results confirm a consistent and single population of particles.

Figure 3.

Representative DLS plots showing intensity and volume percents as a function of size distribution for the hydrodynamic diameters of freeze-dried CHAlg (A,B) and CHAlg-Alb (C,D) nanoparticles dispersed in water.

Table 2 shows the averages of hydrodynamic diameters, which are 382 nm for CHAlg nanoparticles and increase to 475 nm for CHAlg-Alb nanoparticles, indicating that the incorporation of the hydrophobic drug influences the particle colloidal size. Similar trends have been described for nanoparticles containing ivermectin and praziquantel [47,48], where the encapsulation of the hydrophobic drugs led to changes in the fractal dimensionality of the particles as determined by SAXS. In these formulations, it was shown that the colloidal structure is organized as interconnected networks of polymer chains with higher internal distances in the presence of the drugs, resulting in particle expansion. Instead, for “empty” nanoparticles, more compact assemblies fill the internal tridimensional space, providing particles that may have reduced colloidal size. Therefore, in the presence of albendazole, the internal spaces of the polymer network are influenced, thus providing particles of increased hydrodynamic radius. Despite the average size increase in albendazole nanoparticles, the polydispersity for both was in the order of 0.3 (Table 2), confirming that the size distribution was quite similar for particles with and without the drug, as shown in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Size and surface charge profiles of the produced nanoparticles, in terms of colloidal hydrodynamic diameter with the corresponding polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential with the dispersion conductivity.

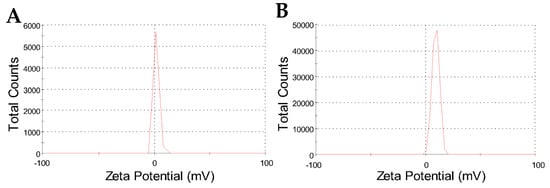

However, the zeta potential results have shown a peculiar surface charge profile, comparing CHAlg with CHAlg-Alb. Figure 4 shows the zeta potential results for both nanoparticles, where single and narrow peaks confirm a single population of particles presenting a unique charge profile for each sample. Of note, the peak for CHAlg is centered close to neutral zeta potential at 2.0 mV, whereas the peak of CHAlg-Alb is centered at 9.5 mV (Table 2), despite both nanoparticles being dispersed in aqueous media of similar conductivity.

Figure 4.

Zeta potential distribution results for CHAlg (A) and CHAlg-Alb (B) freeze-dried nanoparticles dispersed in water.

The zeta potential increase characterized for nanoparticles containing albendazole is not highly significant; however, it indicates, along with the average size increase, that the drug influences, to a certain extent, the colloidal features of the nanoparticles. The slightly positive zeta potential may have important implications for differentiated in vivo performance of the material; for instance, nanoparticles with a positive surface charge may present mucoadhesive and/or muco-penetrating characteristics, as reported for chitosan-N-arginine, alginate, and polypeptide nanoparticles in oral drug delivery systems [49].

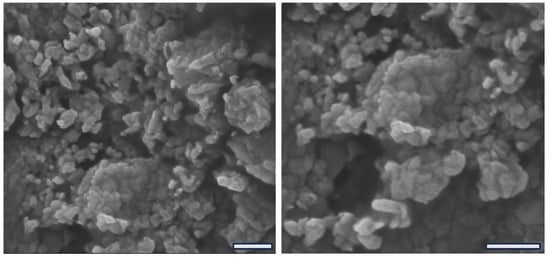

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy of Freeze-Dried Nanoparticles

The process of freeze-dried colloidal nanoparticles can often result in disruption or structural damage of the material, which may compromise its functional activity [50]. We evaluated the structure of the chitosan–alginate nanoparticles by SEM after freeze-drying. Figure 5 shows representative photomicrographs showing the submicrometric and random structure of the nanoparticles. Although clustered by the sample preparation procedure for microscopy observation, it is evident that particles present certain size variation, but all particles are in the nanoscale, i.e., with dimensions under 1 µm.

Figure 5.

SEM photomicrographs of freeze-dried chitosan–alginate nanoparticles showing two magnifications with scale bars expanding 1 µm.

Furthermore, Figure 5 shows that the nanoparticles present a randomized shape-like structure of various polygonal shapes, unveiling an additional structural feature. However, no microscopic differences were identified between the nanoparticles containing albendazole compared to plain nanoparticles, suggesting that the amount of incorporated drug has not influenced the final microscopic appearance of the particles. For more detailed structural characteristics comparing the particles with and without the drug, the DLS analysis provided improved information as described in the previous section. Moreover, similar to previously reported powder-like nanoparticles [39,49], the macroscopic material produced by freeze-dried nanoparticles affords a fine powder that is easy to handle and easy to administer in the in vivo application.

2.4. Encapsulation and Release of Albendazole

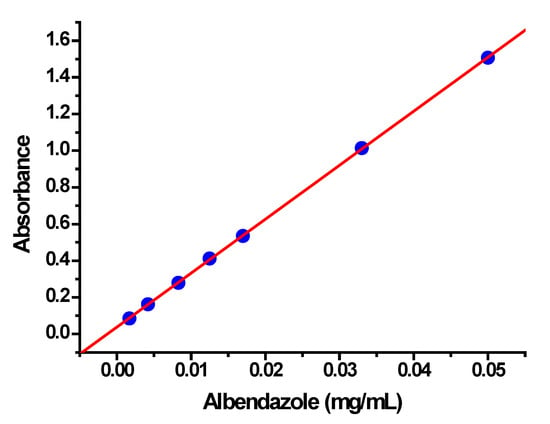

The encapsulation and release of albendazole from the freeze-dried nanoparticle formulation were evaluated by centrifugal and dialysis methods, respectively, applying the Lambert–Beer Law to calculate the concentrations. For these aims, an adequate calibration curve was constructed by measuring the absorbance of a range of albendazole concentrations in solution, following previously reported recommendations [51]. Since albendazole is a poor water-soluble drug, a 1:1 (v:v) methanol/water solution was used in every absorbance measurement. Figure 6 shows the absorbance of albendazole at different concentrations obtained by spectrophotometry.

Figure 6.

Calibration curve obtained by spectrophotometric measurements of albendazole concentrations in a methanol/water (1:1; v:v) solution.

As shown in Figure 6, the calibration curve presents good linearity with a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.99997, and the slope (B) and intercept (A) of the equation of the regression line are 29.45 and 0.0375, respectively. The Lambert–Beer Law was applied to calculate the unknown concentrations (x), x = (y − A)/B, where y is the absorbance of the centrifuged or dialysis samples in the same 1:1 methanol/water solutions.

The obtained encapsulation percentage of albendazole in the freeze-dried nanoparticles was in the order of 98 ± 1%. The high encapsulation percentage must be reported to the hydrophobic nature of albendazole, which may promote its interaction with the chitosan backbone on the hydrophobic cyclic glucose rings and the hydrocarbon linkages, as well as on the remaining acetyl groups (∼5% of monomers) [52]. The result evidences a successful production of the drug delivery material with an almost complete incorporation of the drug.

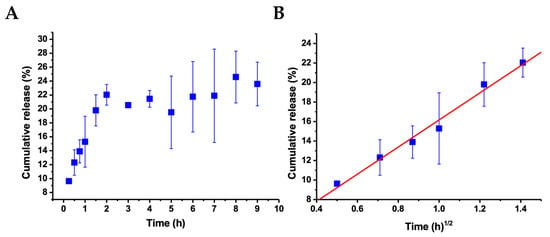

Concerning the release process of albendazole, Figure 7A shows the cumulative release profile as a function of time. As shown, a constantly increasing release was observed during the first two hours, attaining an average of 22% release, after which no considerable increment was observed. To further analyze the release process, different approaches were applied to the data to support the mechanistic and kinetic aspects of albendazole release from the nanoparticles. The best fitting (Figure 7B) was obtained in applying the Higuchi model [53,54], where the increasing linear correlation during the first two hours as a function of the root square of time provides a correlation coefficient r = 0.99287, which was the best fitting compared to the zero-order and Korsmeyer–Peppas models, where the coefficients were lower. The Higuchi model is supported by Fick’s law, considering that the drug release occurs via diffusion from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration, and the cumulative released amount is proportional to the square root of time [54]. The rate of this diffusion is driven by the concentration gradient and the diffusion coefficient of the diffusing substance, thus describing the movement of the substance through a porous material, which here is the nanoparticle, and then through the solution [55]. The slope of the resulting linear plot in Figure 7B is B = 13.90 ± 0.83, which, for the Higuchi model, represents the release rate constant KH. The cumulative release of albendazole at around 22% of the encapsulated concentration during the first two hours, followed by the maintenance of this concentration after two hours, can be considered as sustained and controlled by Fickian diffusion.

Figure 7.

(A) Cumulative release of albendazole from CHAlg nanoparticles as a function of time at 25 °C. (B) Plot of the same results for the two initial hours as a function of the square root of time, according to the Higuchi model for the release kinetics, showing the corresponding linear regression. Time zero corresponds to the introduction of the sample in the release media, and error bars represent the standard deviation from the average of three independent replicates.

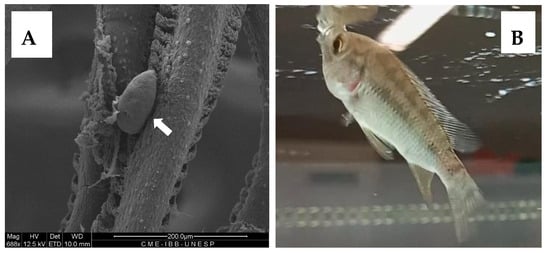

2.5. In Vivo Application and Parasite Treatment

The applicability of albendazole nanoparticles was studied in vivo through oral administration to tilapia fish fingerlings. The fish obtained from a local fish farm were thoroughly examined for parasite infection, and monogenean parasites (Figure 8A) were found on the gills of 100% of the fish, with a mean intensity MI = 14.3 ± 2.4 for an initial survey on 10 individuals. The freeze-dried powder of albendazole nanoparticles was provided to the fish by sprinkling it on the aquarium’s water surface, where all the fish immediately swam to eat the powder (Figure 8B). This observation suggests a high palatability of the material, as previously described for polypeptide [49] and chitosan derivative nanoparticles [39,40,41,48].

Figure 8.

(A) SEM Photomicrograph of a monogenean parasite (white arrow) on the gills of tilapia fish with 100% prevalence. (B) Fingerling of tilapia fish ingesting freeze-dried powder of albendazole nanoparticles.

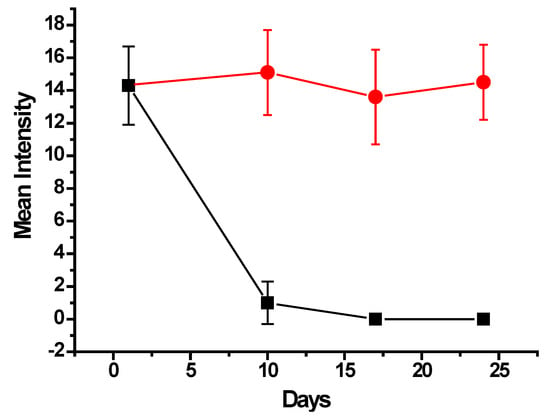

The parasite treatment was conducted using albendazole nanoparticles, and in parallel, a control experiment was performed in the same conditions, administering nanoparticles without albendazole. As shown in Figure 9, for the control group (red circles), there was almost no variation in the MI of parasite infection during the 24-day experiment. This survey, considering that every day point represented the analysis of 10 fish, amounted to a total of 40 examined fish with MI around 14 parasites per fish with 100% prevalence.

Figure 9.

Mean Intensity variation of monogenean parasite infection in tilapia fish for 24 days after the treatment with oral administration of albendazole nanoparticles (black squares) compared to the control of nanoparticles free of drug (red circles).

Nevertheless, for the treatment group, the MI significantly decreased to an average of 1.0 ± 1.3 parasites per fish, as shown in Figure 9 (black squares), along with a prevalence of 50%, at 10 days from the beginning of the treatment with albendazole nanoparticles. Then, at the 17th and 24th days, the fish were completely clean, with no parasites found in all examined fish.

The results shown in Figure 9 evidence an effective and efficient treatment of the monogenean parasite infection in fingerlings of farmed tilapia. Considering the concentration of albendazole in the quantity of nanoparticles administered to the total 40 fish, the average total drug dose, which every fish received, was 3.75 mg provided in 6 days in 12 administrations (twice a day). The average weight of all treated fish was 4.10 g, leading to a total administered dose of 915 mg/kg body weight. Alves et al. [20] have described that submitting fingerlings of Colossoma macropomum fish in baths containing 500 mg/L provided an efficacy of 48.6% in a 24 h bath. However, in their study, a mortality of 6.6% was reported, and taking into account that albendazole is a hydrophobic drug, an effective application in baths requires the use of solvents such as methanol, ethanol, or DMSO to enable its dispersion in aquarium water. The use of solvents may represent drawbacks in aquaculture, especially concerning toxicity [31,32,33].

In the present study, no mortality and no abnormal behavior were recorded during the whole 24-day period of experiments, neither for the treatment group nor for the control, suggesting that the chitosan–alginate nanoparticles may be considered safe. Moreover, it was evidenced that the nanoparticles possess palatability, which makes oral administration easy and thus enables the actual administration of the carried anthelmintic drug, hence providing the efficacious treatment. As a matter of fact, the nanoparticles containing albendazole represent a promising strategy for parasite treatment in farmed fish.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Chitosan with a medium average molecular weight (130 kDa) and a high deacetylation degree (95%) was from Primex (Iceland). Alginate (200 kDa) and albendazole (methyl-5-(propylthio)-2-benzimidazol carbamate; analytical standard, 98%) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other reagents were of analytical grade, and water was from a MilliQ Millipore system with a total organic carbon value of <15 ppb and a resistivity of 18 MΩcm.

3.2. Nanoparticles Preparation

Nanoparticles were prepared by the complex coacervation method [40]. Initially, chitosan and alginate were separately dissolved in an acetate buffer (40 mM, pH 4.5) by magnetic stirring for 16 and 2 h, respectively. The alginate solution was titrated into the chitosan solution, either containing or not containing 50 mg of albendazole. The preparations were kept under stirring overnight and then immediately frozen at −80 °C for 3 h. The frozen particles were submitted to lyophilization in a Liotop-Liobras equipment (Liobras, Sao Carlos, Brazil) under vacuum for 72 h. The freeze-dried nanoparticles were kept in a fridge at 4 °C until use.

3.3. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

To optimize the stoichiometry of nanoparticle preparation and evaluate the thermodynamics of their formation, ITC experiments were performed using a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal Inc., Northampton, MA, USA). Before the experiments, chitosan and alginate solutions were submitted to reduced pressure to avoid the interference of bubbles. The working cell of the equipment with 1.442 mL in volume was filled with chitosan solution. One aliquot of 2 μL, followed by 27 aliquots of 10 μL of alginate solution, was injected stepwise with a 400 s interval into the working cell, which was kept under constant stirring at 307 rpm and at 25 °C. The data acquisition and analysis were carried out with Origin 7 software provided by MicroCal. The data fitting was performed applying the single set of identical binding sites model, as previously described [40].

3.4. Dynamic Light Scattering and Zeta Potential

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to determine the size distribution and polydispersity of the freeze-dried nanoparticles dispersed in an aqueous medium. The hydrodynamic radius of nanoparticle dispersion was measured in a Malvern Zetasizer 300 ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK), operating with a 4 mW HeNe laser at a wavelength of 632.8 nm and detection at an angle of 173°. The measurements were performed in a temperature-controlled chamber at 25 °C. The typical autocorrelation functions were acquired using exponential spacing of the correlation time, and data analysis was performed with software provided by Malvern. The polydispersity was obtained with second-order cumulant analysis of the correlation functions, applying the amplitude of the correlation function and the relaxation frequency.

The zeta potential of the nanoparticles was measured using the same equipment, acquiring at least 100 runs per sample at 25 °C. The principle of the measurement is based on the laser Doppler velocimetry, where the electrophoretic mobility is converted to zeta potential by applying the Helmholtz–Smoluchowski relation. In both experiments, the folded capillary cells were employed.

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the freeze-dried nanoparticles was evaluated by SEM in an Apreo ChemiSEM System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Chicago, IL, USA). Samples were prepared by slightly sprinkling the fine powder over a double-sided adhesive carbon tape, which was stuck on aluminum stubs. The stubs were placed in a fine coating ion sputter (Leica EM SCD 500, Wetzlar, Germany) and metalized by sputtering with gold. The samples were exposed to an accelerated voltage of 10.0 kV beam strength and thoroughly scanned for particle surface morphology and size distribution.

Infected tissues fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide overnight and dehydrated in a graded ethanol series. The samples were dried in a critical point chamber BALZERS CPD 030 (Balzars, MA, USA) using carbon dioxide and were included in an aluminum stub using a double-sided carbon tape and metalized by sputtering with metallic gold. Samples were visualized with a Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Chicago, IL, USA) operating at 12.5 kV at the Electron Microscopy Center of the Institute of Biosciences of Botucatu, UNESP.

3.6. Encapsulation and Release of Albendazole

The percentage of encapsulation of albendazole was determined using the centrifugation–spectrophotometry method [53]. A series of albendazole concentrations, from 0.002 to 0.050 mg/mL, was prepared by dissolving the drug in methanol and diluting to the different concentrations in a 1:1 (v:v) methanol/water solution. The absorbance of each concentration was measured using spectrophotometry in a K37-UVVIS UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Kasvi, Hong Kong, China) at 220 nm, with the solution used as the standard. These measurements were employed to construct the calibration curve of absorbance as a function of concentration for albendazole and determine the linear fit. A known quantity of freeze-dried nanoparticles containing albendazole was dispersed in 10 mL of water by 1 min vortex mixing and then immediately centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 30 min (CD 20000 centrifuge, Anco, Hong Kong, China). An aliquot of 1 mL of the supernatant was collected, mixed with the same amount of pure methanol, and the absorbance was measured. The encapsulation percentage was calculated by applying the Lambert–Beer law using the calibration fit [56]. The experiment was executed in triplicate for independent nanoparticle preparations.

The release of albendazole over time was determined using the dialysis method [53]. Briefly, the total amount of freeze-dried nanoparticles containing 50 mg of albendazole was dispersed in 50 mL of water in a dialysis membrane (Servapor, 3500 MWCO) previously washed in water. The dialysis was performed at room temperature (23–24 °C) in a beaker with 90 mL of water under constant magnetic stirring (440 rpm). At every time period, an aliquot of 1.5 mL was collected and diluted with the same volume of methanol, and the absorbance was measured. The volume in the beaker was kept constant by adding the same amount of water. The concentrations were calculated using the calibration fit, and the corresponding drug release profile was represented by the cumulative temporal percent amount of drug released calculated from the total amount of albendazole in the particles. The assays were performed in triplicate, and the average and standard deviation were calculated.

3.7. In Vivo Experiments

The in vivo experiments were conducted using fingerlings of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fish obtained from an aquaculture farm located in the municipality of Pardinho, State of São Paulo, Brazil (23°04′51″ S, 48°22′26″ W). The fish were naturally infected with monogenean parasites in the farming. An aquarium system with a constant circulating and filtered water (dissolved oxygen: 5.68 ± 0.78 mg/mL; ammonium: 0.02 ± 0.01 mg/mL; hardness: 80 ± 6 mg/mL; pH: 6.5 ± 0.2), thermo-standardized at 26 ± 1 °C, was employed in the treatment experiments. Eight aquariums, each 60 L in volume, were acclimatized to receive the fish, and each aquarium contained a population of 10 fish. The fish were housed in the aquariums for 7 days before the experiments and nourished with the fish’s freshwater ration (TetraMin Tetra flakes) twice a day at 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. Four aquariums were designated for the experiment with the freeze-dried nanoparticles containing albendazole and the other four aquariums for the control with nanoparticles without the drug.

The nanoparticles were weighed, and 50 mg of the powder was administered in each aquarium 20 min before the daily feedings for 6 days, resulting in a total of 2.4 g of nanoparticles with albendazole and the same quantity of nanoparticles without albendazole. The water circulation system was turned off during administration and for an additional period of 30 min to avoid the clearance of nanoparticles in the filters. After the 6 days of treatment, fish were normally fed as before. On the 10th day from the beginning of the treatment, 10 fish were randomly collected from the 4 aquariums of administered albendazole nanoparticles, immediately euthanized by neural pithing [57] and examined for parasite infection using an optical microscope under bright-field imaging and a 10× objective. The same process was performed for the control group. This procedure was repeated after one and two weeks to monitor the treatment progress.

The parasitic indices of prevalence (P) and mean intensity (MI) were calculated according to the criteria by Bush et al. [58] with P (%) = NP/NE × 100, where NP is the number of fish infected by parasites and NE is the total number of fish examined, and MI = Nsp1/NPsp1, where Nsp1 is the number of a given class of parasite and NPsp1 is the number of fish infected by a given class of parasite.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrated that the coacervation between chitosan and alginate enabled the reproducible formation of nanoparticles in the presence and absence of albendazole, with similar thermodynamic parameters, confirming that the incorporation of the drug does not alter the polyelectrolyte complexation process. The nanoparticles retained their structural integrity after freeze-drying and a high encapsulation efficiency of albendazole was provided. In addition, the initial release profile exhibited a controlled behavior that fitted the Higuchi model, indicating the predominance of a diffusional mechanism during the early stages of release.

In the in vivo assays, the nanoparticles were spontaneously ingested by the fish, and no mortality was recorded in any experimental group. Oral administration of the albendazole-loaded formulation for six days markedly reduced the initial parasite intensity and provided the complete elimination of monogeneans in subsequent samplings, whereas fish in the control group maintained stable infestation levels throughout the experiment. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that chitosan–alginate nanoparticles enable efficient encapsulation and effective oral delivery of albendazole, representing a viable alternative for the treatment of monogenean infestations in farmed tilapia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.M. and O.M.; data curation, P.D.M. and O.M.; formal analysis, A.V.C.R., N.L.R.S., R.R.M.M., P.D.M. and O.M.; funding acquisition, P.D.M.; investigation, A.V.C.R., N.L.R.S., C.B.T., R.R.M.M. and P.D.M.; methodology, A.V.C.R., N.L.R.S., C.B.T., R.R.M.M. and P.D.M.; supervision, P.D.M.; writing—original draft, A.V.C.R., N.L.R.S., P.D.M. and O.M.; writing—review and editing, P.D.M. and O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (grant number: 2022/12376-4).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocols carried out during in vivo studies were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of the São Paulo State University (CEUA nº 2173310724, approval date 1 May 2025), and all experiments were performed in accordance with the U.K. Animals Scientific Procedures Act 1986 and associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, and the National Institute of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We declare that our research data are available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

A.V.C.R. and C.B.T. thank the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for their Master’s Degree fellowship (2024/05235-0; 2025/02188-4) and N.L.R.S. for a PhD fellowship (2024/00115-7). O.M. thanks CNPq for a research productivity grant. P.D.M. and O.M. thank FAPESP for the research financial support (2022/12376-4; 2023/11142-2; 2024/01040-0). The authors thank Daniela Carvalho dos Santos, Tiago Tardivo, and Luiza H. Stauffer from the Electron Microscopy Center of the Institute of Biosciences of Botucatu, UNESP, for supporting the SEM analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Talarek, E.; Aniszewska, M.; Dobrzeniecka, A.; Kmiotek, J.; Pokorska-Śpiewak, M. Autoimmune Hepatitis After Successful Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Direct-Acting Antivirals: A Pediatric Case Report. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, S.Y.; Mall, M.A. The future of cystic fibrosis treatment: From disease mechanisms to novel therapeutic approaches. Lancet 2023, 402, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbosu, E.E.; Ledger, S.; Kelleher, A.D.; Wen, J.; Ahlenstiel, C.L. Targeted Nanocarrier Delivery of RNA Therapeutics to Control HIV Infection. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.I.; Ahammad, F.; Mohammed, H. Cutting-edge technologies for detecting and controlling fish diseases: Current status, outlook, and challenges. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2024, 55, e13051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, D.V.V.; Jatobá, A.; da Silva, A.V.; de Souza, A.P.; Farias, C.F.S.; Lopes, E.M.; Owatari, M.S.; Ventura, A.S.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Fontes, S.T.; et al. Therapeutic Efficacy of Monoterpenes in Nile Tilapia Infected with Edwardsiella tarda: A Phytogenic Alternative to Oxytetracycline. J. Fish Dis. 2025, 49, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossouw, J.; Trataris-Rebisz, A.N.; Tempia, S.; Rostal, M.K.; Karesh, W.B.; Msimang, V. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Human Brucellosis in a Farming and Animal Health Community in South Africa, 2015–2016. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, C.; Hamilton, L.; Rushton, J. Re-thinking public health: Towards a new scientific logic of routine animal health care in European industrial farming. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazac, R.; Sahlin, K.R.; Hyypiä, I.; Keränen, F.; Niva, N.; Berglund, N.; Herzon, I. Does “better” mean “less”? Sustainable meat consumption in the context of natural pasture-raised beef. Agric. Hum. Values 2025, 42, 1637–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.; Dey, M.M.; Surathkal, P. Price transmission and market integration of Bangladesh fish markets. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibel, H.; Weirup, L.; Schulz, C. Fish Welfare—Between Regulations, Scientific Facts and Human Perception. Food Ethics 2020, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röcklinsberg, H. Fish Consumption: Choices in the Intersection of Public Concern, Fish Welfare, Food Security, Human Health and Climate Change. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2015, 28, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarati, M.; Zorriehzahra, M.J.; Hassantabar, F.; Mehrabi, Z.; Dhawan, M.; Sharun, K.; Bin Emran, T.; Dhama, K.; Chaicumpa, W.; Shamsi, S. Zoonotic diseases of fish and their prevention and control. Vet. Quarterly 2022, 42, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoslavskij, A.; Terentjeva, M.; Eizenberga, I.; Valcina, O.; Bartkevics, V.; Berzins, A. Major foodborne pathogens in fish and fish products: A review. Ann. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, A.J.; Pratoomyot, J.; Bron, J.; Paladini, G.; Brooker, E.; Brooker, A. Economic impacts of aquatic parasites on global finfish production. Glob. Aquacul. Advocate 2015, 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Maezono, M.; Nielsen, R.; Buchmann, K.; Nielsen, M. The Current State of Knowledge of the Economic Impact of Diseases in Global Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares-Dias, M.; Martins, M.L. An overall estimation of losses caused by diseases in the Brazilian fish farms. J. Parasit. Dis. 2017, 41, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoai, T.D. Reproductive strategies of parasitic flatworms (Platyhelminthes, Monogenea): The impact on parasite management in aquaculture. Aquacult. Int. 2020, 28, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, P.D.; Mertins, O.; Mathews, J.P.D.; Ismiño, O.R. Massive parasitism by Gussevia tucunarense (Platyhelminthes: Monogenea: Dactylogyridae) in fingerlings of bujurqui-tucunare cultured in the Peruvian Amazon. Acta Parasitol. 2013, 58, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, A.F.; Mathews, P.D.; Luna, L.E.; Mathews, J.D. Outbreak of Notozothecium bethae (Monogenea: Dactylogyridae) in Myleus schomburgkii (Actinopterygii: Characiformes) cultured in the Peruvian Amazon. J. Parasit. Dis. 2016, 40, 1631–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.M.G.; Nogueira, J.N.; Barriga, I.B.; Santos, J.R.; Santos, G.G.; Tavares-Dias, M. Albendazole, levamisole and ivermectin are effective against monogeneans of Colossoma macropomum (Pisces: Serrasalmidae). J. Fish Dis. 2019, 42, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; Kim, D.S.; Kim, K.H. Evaluation of treatment efficacy of doxycycline and albendazole against scuticociliatosis in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquaculture 2013, 416, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Wang, W.-R.; Chen, Y.-X.; Jin, Y.-G.; Sun, L.-J.; Li, S.-H.; Yang, F.; Li, X.-P.; et al. Depletion of Albendazole and Its Metabolites and Their Impact on the Gut Microbial Community Following Multiple Oral Dosing in Yellow River Carp (Cyprinus carpio haematopterus). Fishes 2025, 10, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, B.; Rummel, N.; Gieseker, C.; Cheely, C.S.; Reimschuessel, R. Residue depletion of albendazole and its metabolites in the muscle tissue of large mouth and hybrid striped bass after oral administration. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 8173–8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negreiros, L.P.; Souza, E.X.; Lima, T.A.; Tavares-Dias, M. Albendazole is effective for controlling monogenean parasites of the gills of Piaractus brachypomus (Serrasalmidae) and Megaleporinus macrocephalus (Anostomidae). Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 31, e010322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, C.F.S.; Brandão, F.R.; Sebastião, F.A.; Souza, C.M.; Monteiro, P.C.; Majolo, C.; Chagas, E.C. Albendazole and praziquantel for the control of Neoechinorhynchus buttnerae in tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum). Aquacult. Int. 2021, 29, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnnajirakul, S.; Phalitakul, S.; Sanisuriwong, J. Therapeutic effect of albendazole and praziquantel for digenean trematode (metacercarial stage) treatment in goldfish (Carassius auratus). J. Mahanakorn Vet. Med. 2009, 4, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, B.; Rummel, N.; Gieseker, C.; Serfling, S.; Reimschuessel, R. Metabolism and residue depletion of albendazole and its metabolites in rainbow trout, tilapia and Atlantic salmon after oral administration. J. Vet. Pharm. Therap. 2003, 26, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, R.P.; Braga, P.A.C.; Jonsson, C.M.; Brandao, F.R.; Chagas, E.C.; Reyes, F.G.R. Therapeutic efficacy and bioaccumulation of albendazole in the treatment of tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) parasitized by acanthocephalan (Neoechinorhynchus buttnerae). Aquacult. Res. 2022, 53, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yang, H.-Y.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Y.-G.; Li, Z.-E.; Duan, M.-H.; Zhang, Y.-N. Pharmacokinetics and Tissue Distribution of Albendazole and Its Three Metabolites in Yellow River Carp (Cyprinus carpio haematopterus) after Single Oral Administration. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Evans, E.R.; Hasbrouck, N.; Reimschuessel, R.; Shaikh, B. Residue depletion of albendazole and its metabolites in aquacultured yellow perch (Perca flavescens). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Therap. 2012, 35, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxendine, S.L.; Cowden, J.; Hinton, D.E.; Padilla, S. Vulnerable windows for developmental ethanol toxicity in the Japanese medaka fish (Oryzias latipes). Aquatic Toxicol. 2006, 80, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviraj, A.; Bhunia, F.; Saha, N.C. Toxicity of Methanol to Fish, Crustacean, Oligochaete Worm, and Aquatic Ecosystem. Int. J. Toxicol. 2004, 23, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Vieira, L.F.; Bojic, C.; Santana Alvarenga, I.F.; de Carvalho, T.S.; Masfaraud, J.F.; Cotelle, S. Ecotoxic effects of the vehicle solvent dimethyl sulfoxide on Raphidocelis subcapitata, Daphnia magna and Brachionus calyciflorus. Chem. Ecol. 2022, 38, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Campbell, F.; Kros, A. DePEGylation strategies to increase cancer nanomedicine efficacy. Nanoscale Horiz. 2019, 4, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanna, F.; Gambardella, A.; Contartese, D.; Visani, A.; Fini, M. Nano-Based Biomaterials as Drug Delivery Systems Against Osteoporosis: A Systematic Review of Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Nanomaterials 2021, 112, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Dominguez, D.J.; López-Enríquez, S.; Alba, G.; Garnacho, C.; Jiménez-Cortegana, C.; Flores-Campos, R.; de la Cruz-Merino, L.; Hajji, N.; Sánchez-Margalet, V.; Hontecillas-Prieto, L. Cancer Nano-Immunotherapy: The Novel and Promising Weapon to Fight Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr-Eldahan, S.; Nabil-Adam, A.; Shreadah, M.A.; Maher, A.M.; Ali, T.E.S. A review article on nanotechnology in aquaculture sustainability as a novel tool in fish disease control. Aquacult. Int. 2021, 29, 1459–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, B.; Mahanty, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Choudhury, A.R.; Daware, A.; Bhattacharjee, S. Nanotechnology: A next-generation tool for sustainable aquaculture. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, R.R.M.; Mertins, O.; Tavares-Dias, M.; Flores-Gonzales, A.P.; Patta, A.C.M.F.; Ramirez, C.A.B.; Rigoni, V.L.S.; Mathews, P.D. High compliance and effective treatment of fish endoparasitic infections with oral drug delivery nanobioparticles: Safety of intestinal tissue and blood parameters. J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, P.D.; Patta, A.C.M.F.; Gonçalves, J.V.; Gama, G.D.S.; Garcia, I.T.S.; Mertins, O. Targeted Drug Delivery and Treatment of Endoparasites with Biocompatible Particles of pH-Responsive Structure. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, P.D.; Patta, A.C.M.F.; Madrid, R.R.M.; Ramirez, C.A.B.; Pimenta, B.V.; Mertins, O. Efficient Treatment of Fish Intestinal Parasites Applying a Membrane-Penetrating Oral Drug Delivery Nanoparticle. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 2911–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, M.; Unsworth, L.D. Application of Isothermal Titration Calorimetry for Characterizing Thermodynamic Parameters of Biomolecular Interactions: Peptide Self-Assembly and Protein Adsorption Case Studies. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 3463–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omanovic-Miklicanin, E.; Manfield, I.; Wilkins, T. Application of isothermal titration calorimetry in evaluation of protein–nanoparticle interactions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 127, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, W.R.; Schulz, M.D. Isothermal titration calorimetry: Practical approaches and current applications in soft matter. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 8760–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, T.; Lewis, R.N.A.H.; Hodges, R.S.; McElhaney, R.N. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry Studies of the Binding of a Rationally Designed Analogue of the Antimicrobial Peptide Gramicidin S to Phospholipid Bilayer Membranes. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 11279–11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrina, J.L.; Gennari, F.C.; Condo, A.M.; Guillermet, A.F. Predictive Gibbs-energy approach to crystalline/amorphous relative stability of nanoparticles: Size-effect calculations and experimental test. J. Alloys Comp. 2016, 689, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, R.R.M.; Mathews, P.D.; Patta, A.C.M.F.; Gonzales-Flores, A.P.; Ramirez, C.A.B.; Rigoni, V.L.S.; Tavares-Dias, M.; Mertins, O. Safety of oral administration of high doses of ivermectin by means of biocompatible polyelectrolytes formulation. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patta, A.C.M.F.; Mathews, P.D.; Madrid, R.R.M.; Rigoni, V.L.S.; Silva, E.R.; Mertins, O. Polyionic complexes of chitosan-N-arginine with alginate as pH responsive and mucoadhesive particles for oral drug delivery applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, C.A.B.; Mathews, P.D.; Madrid, R.R.M.; Garcia, I.T.S.; Rigoni, V.L.S.; Mertins, O. Antibacterial polypeptide-bioparticle for oral administration: Powder formulation, palatability and in vivo toxicity approach. Biomat. Adv. 2023, 153, 213525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, S.G.; Najahi-Missaoui, W. Lyophilization of Nanoparticles, Does It Really Work? Overview of the Current Status and Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, A.C.; Olabemiwo, O.M.; Salawu, M.O.; Obiyenwa, G.K. Developing a spectrophotometric method for the estimation of albendazole in solid and suspension forms. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2010, 5, 379–382. [Google Scholar]

- Philippova, O.E.; Volkov, E.V.; Sitnikova, N.L.; Khokhlov, A.R.; Desbrieres, J.; Rinaudo, M. Two Types of Hydrophobic Aggregates in Aqueous Solutions of Chitosan and Its Hydrophobic Derivative. Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, R.R.M.; Mathews, P.D.; Pramanik, S.; Mangiarotti, A.; Fernandes, R.; Itri, R.; Dimova, R.; Mertins, O. Hybrid crystalline bioparticles with nanochannels encapsulating acemannan from Aloe vera: Structure and interaction with lipid membranes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 673, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Lobo, J.M.S. Modeling and comparison of dissolution profiles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 13, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeagyei, A.K.; Grenfell, J.R.A.; Airey, G.D. Application of Fickian and non-Fickian diffusion models to study moisture diffusion in asphalt mastics. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, R. Misuse of Beer-Lambert Law and other calibration curves. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadros, R.C.; Rivadeneyra, N.L.S.; Flores-Gonzales, A.; Mertins, O.; Malta, J.C.O.; Serrano-Martínez, M.E.; Mathews, P.D. Intestinal histological alterations in farmed red-bellied pacu Piaractus brachypomus (Characiformes: Serrasalmidae) heavily infected by roundworms. Aquacult. Int. 2021, 29, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M.; Shostak, A.W. Parasitology Meets Ecology on Its Own Terms: Margolis et al. Revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.