DHA Modulates Pparγ Gene Expression Depending on the Maturation Stage of 3T3-L1 Adipocytes at Time of Exposure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

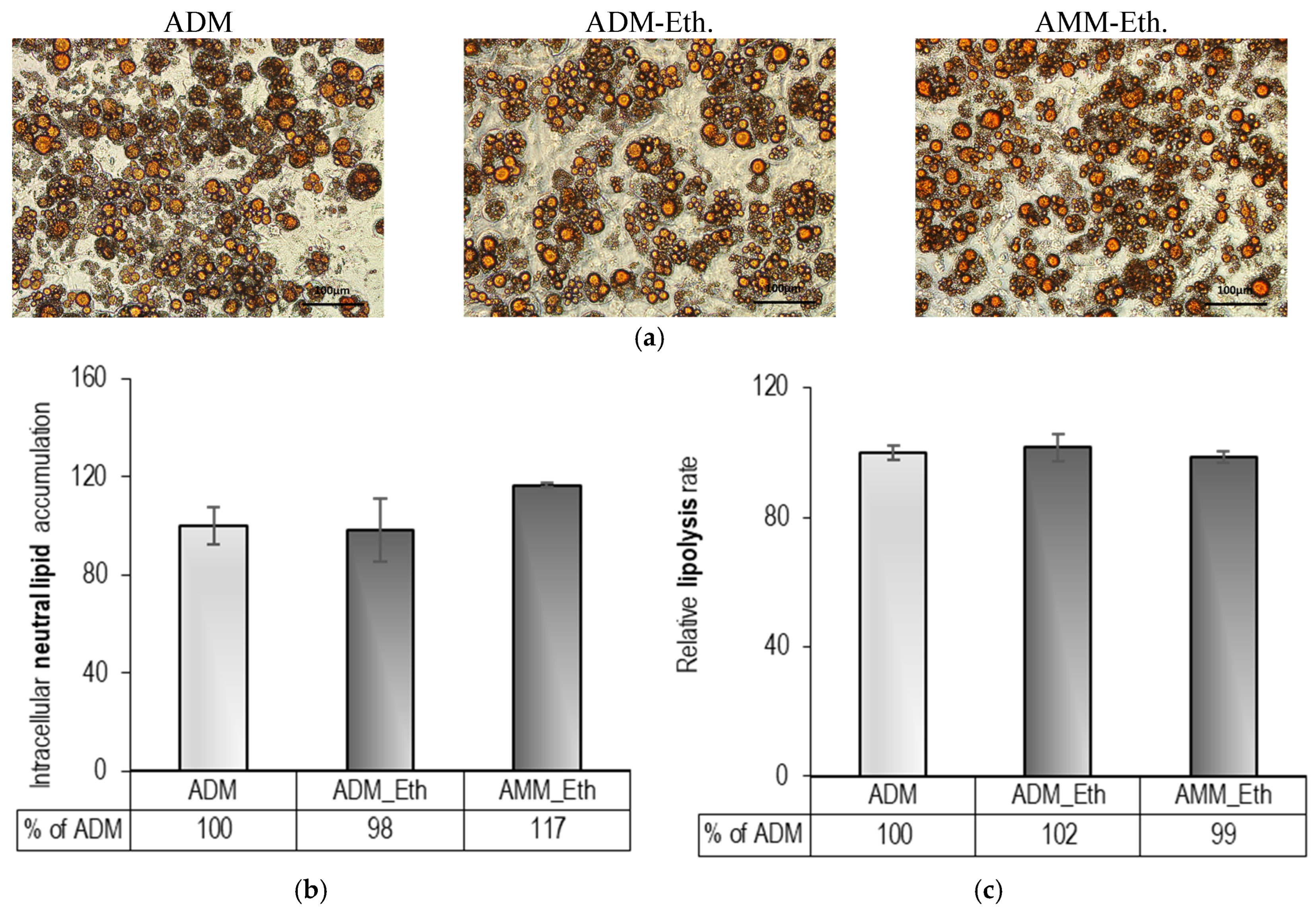

2.1. Pre-Experimental Procedure: Evaluation of 0.05% (v/v) Ethanol Effects on Adipogenesis

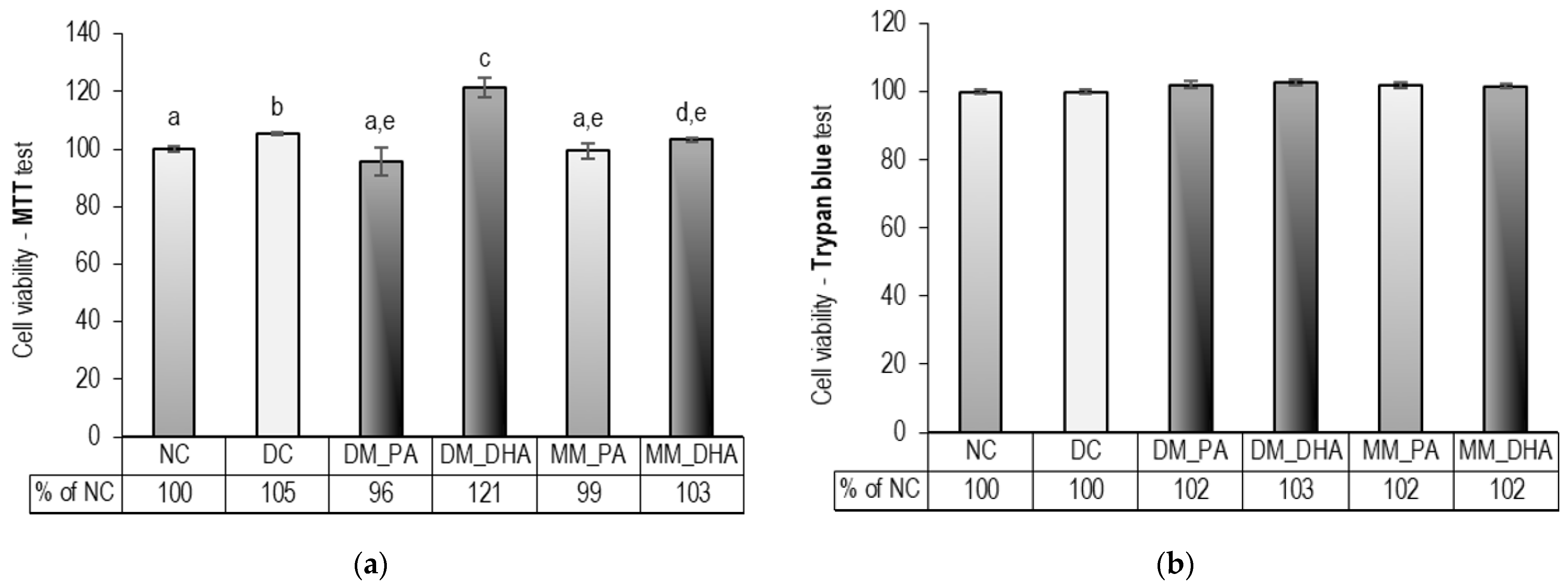

2.2. DHA Influence on the Viability of Immature and Mature 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

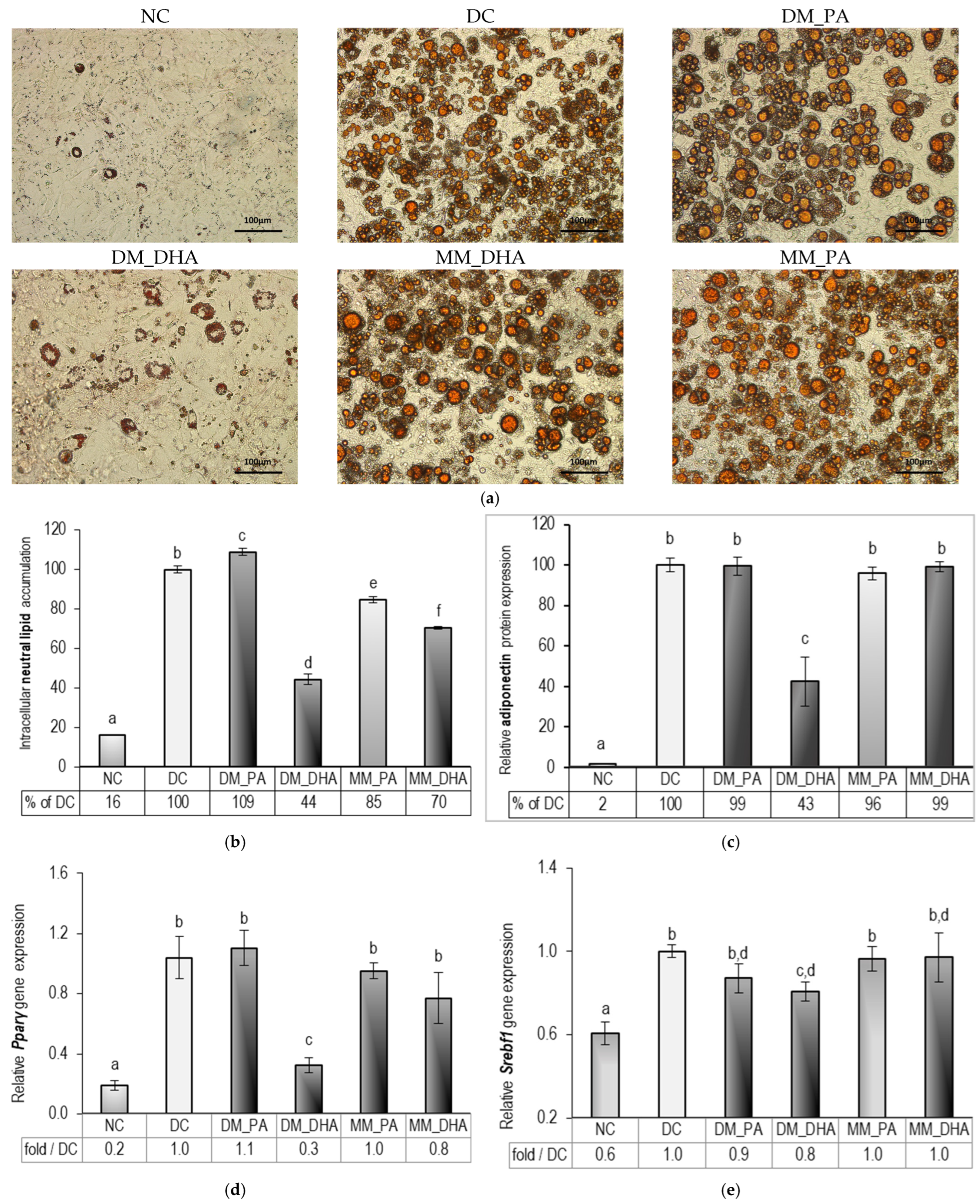

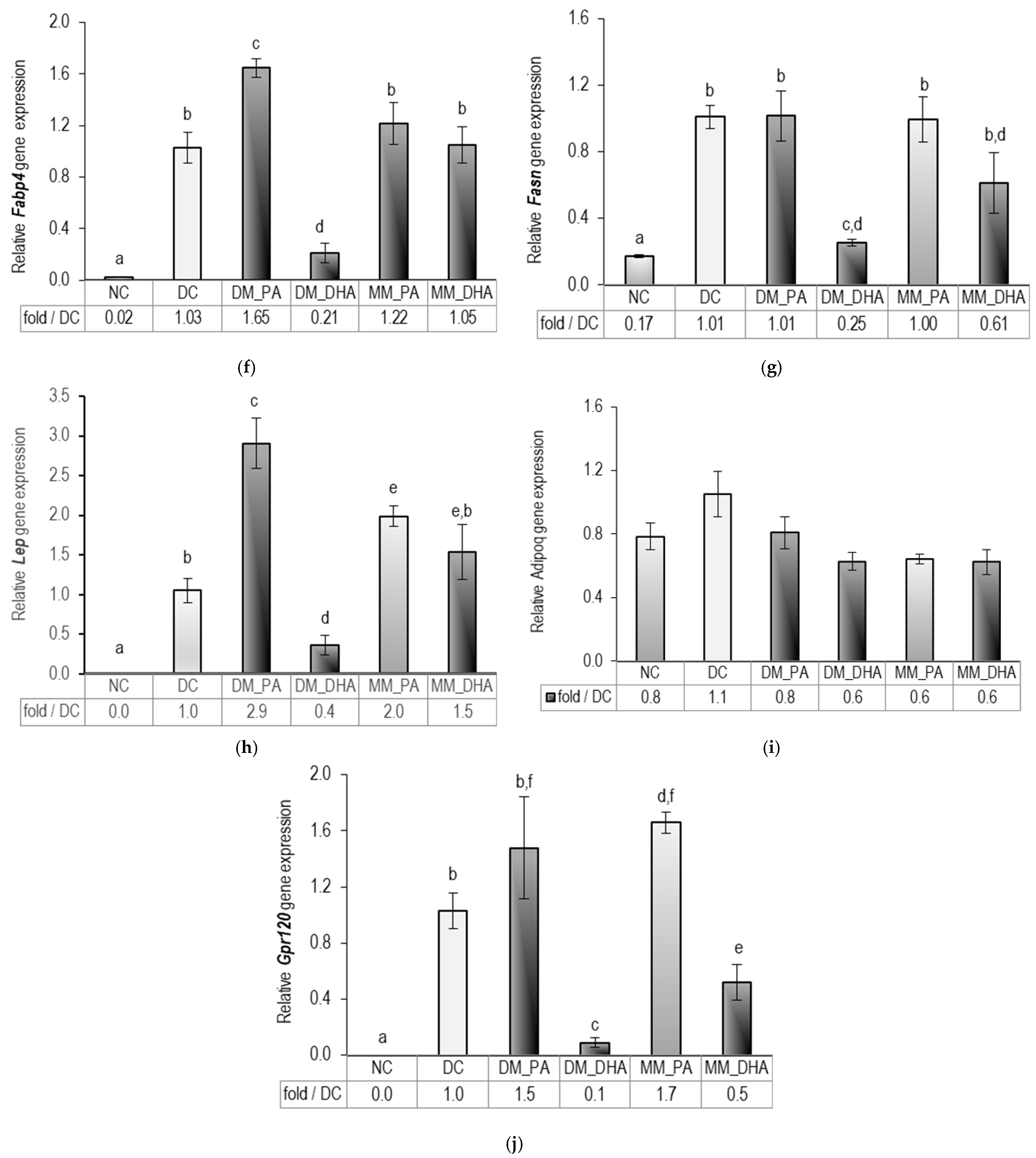

2.3. DHA Impact on Lipid Accumulation in Immature and Mature 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

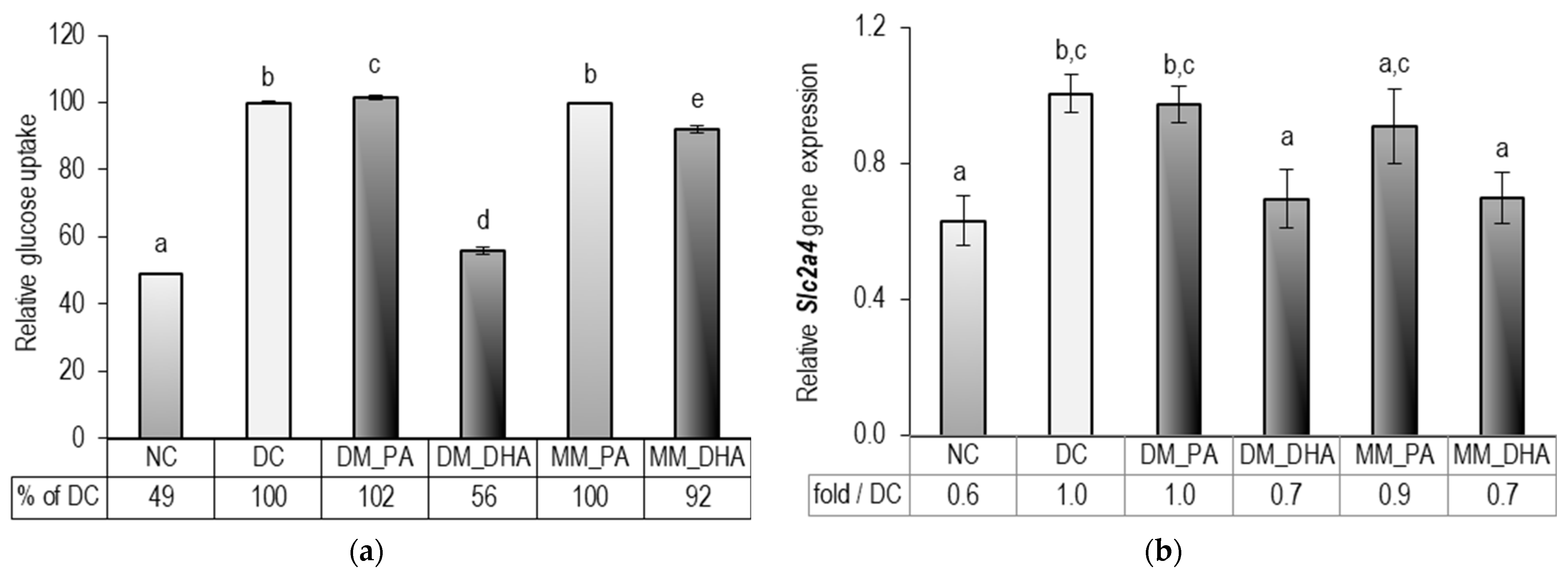

2.4. DHA Impact on Glucose Uptake in Immature and Mature 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

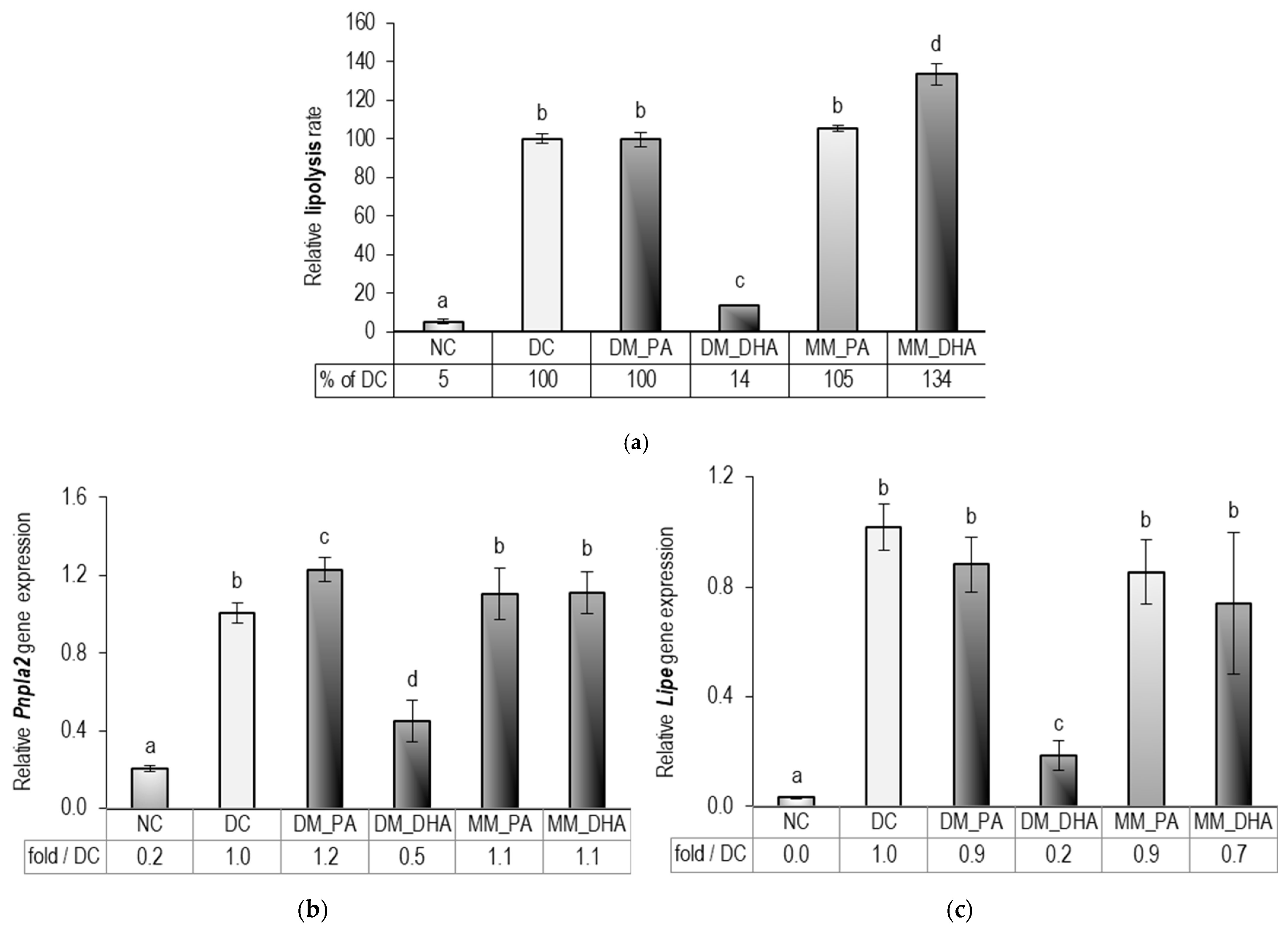

2.5. DHA Impact on the Lipolysis in Immature and Mature 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

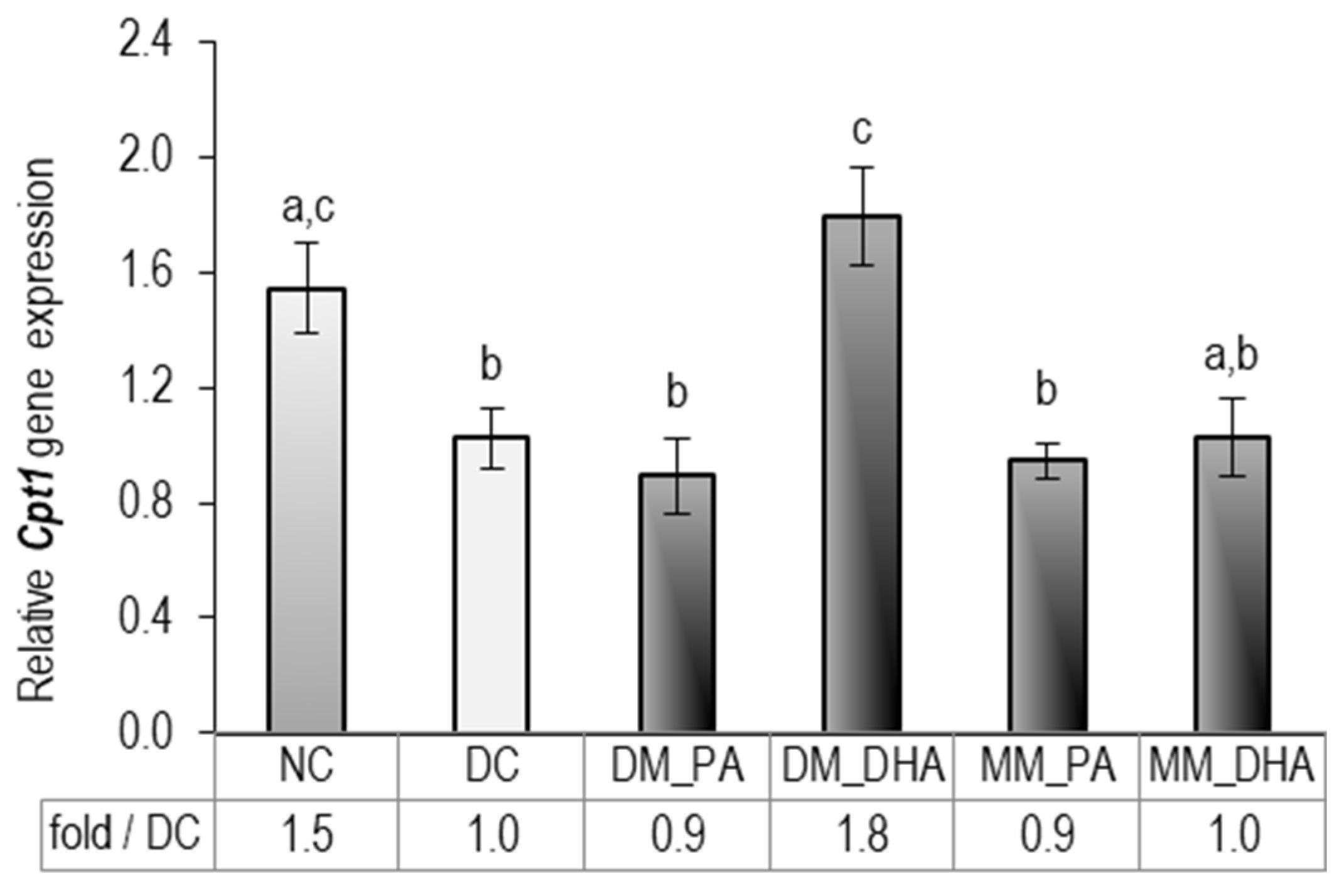

2.6. DHA Impact on Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (Cpt1) Gene Expression in Immature and Mature 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Chemical Reagents

4.2. Composition of the Culture Media

4.3. Fatty Acid Dissolving Procedure

4.4. Pre-Experimental Procedure: Effect of 0.05% (v/v) Ethanol on Adipogenesis and Lipolysis in Differentiating and Mature Adipocytes

4.5. Experimental Design

4.6. Cell Viability Assays

4.7. Oil Red O Staining and Evaluation of Intracellular Lipid Accumulation

4.8. Glucose Uptake

4.9. Lipolysis Rate

4.10. Gene Expression Analysis

4.11. ELISA Adiponectin Assessment

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3T3-L1 | Mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line used as an adipogenesis model |

| 18S | 18S ribosomal RNA |

| 36b4 | Ribosomal protein, large, P0 |

| Acaca | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha |

| Adipoq | Adiponectin |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| Actb | Beta-actin |

| ACOX1 | Acyl-CoA oxidase 1 |

| ADM | Adipocyte differentiating medium (untreated control) |

| ADM-Eth | Differentiating cells treated with 0.05% (v/v) ethanol (days 1–9) |

| AMM | Adipocyte maintenance medium |

| AMM-Eth | Mature adipocytes treated with 0.05% (v/v) ethanol (days 10–18) |

| ATGL | Adipose triglyceride lipase (encoded by Pnpla2) |

| BM | Basal medium |

| C/EBPα | CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins alpha |

| C/EBPβ | CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins beta |

| C/EBPδ | CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins delta |

| Cpt1 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| CRTC2 | CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 2 |

| cAMP/PKA | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate/protein kinase A signaling pathway |

| cDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

| DC | Differentiated control |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| DM_PA | Differentiating cells treated with 60 µM palmitic acid (days 1–9) |

| DM_DHA | Differentiating cells treated with 60 µM docosahexaenoic acid (days 1–9) |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ΔΔCt | delta delta Ct |

| EG | Extracellular glucose concentration |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| Fabp4 | Fatty acid-binding protein 4 |

| Fasn | Fatty acid synthase |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| Gpr120 | G protein-coupled receptor 120 (gene) |

| GPR120 | G-protein-coupled receptor 120 (protein) |

| GPCRs | G-protein-coupled receptors |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| Hmbs | Hydroxymethylbilane synthase |

| Hprt | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase |

| HSL | Hormone-sensitive lipase (encoded by Lipe) |

| IBMX | 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine |

| IG | Initial glucose concentration |

| Lep | Leptin receptor, transcript variant 1 |

| Lipe | Lipase, hormone-sensitive |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| MM_PA | Mature adipocytes treated with 60 µM palmitic acid (days 10–18) |

| MM_DHA | Mature adipocytes treated with 60 µM docosahexaenoic acid (days 10–18) |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NC | Non-differentiated control |

| NEFA | Non-esterified fatty acids |

| NOX4 | NADPH oxidase 4 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PA | Palmitic acid |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| Pnpla2 | Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 2 |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (protein) |

| Pparγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (gene) |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| Slc2a4 | Solute carrier family 2 member 4 (encoding glucose transporter 4, GLUT4) |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| Srebf1 | Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 |

| SREBP-1c | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c |

References

- Alabdulkarim, B.; Bakeet, Z.A.N.; Arzoo, S. Role of Some Functional Lipids in Preventing Diseases and Promoting Health. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2012, 24, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, K.; Tiuca, I.-D. Importance of Fatty Acids in Physiopathology of Human Body. In Fatty Acids; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3301-8. [Google Scholar]

- Picklo, M.J., Sr.; Idso, J.; Seeger, D.R.; Aukema, H.M.; Murphy, E.J. Comparative Effects of High Oleic Acid vs High Mixed Saturated Fatty Acid Obesogenic Diets upon PUFA Metabolism in Mice. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2017, 119, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerab, D.; Blangero, F.; da Costa, P.C.T.; de Brito Alves, J.L.; Kefi, R.; Jamoussi, H.; Morio, B.; Eljaafari, A. Beneficial Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Obesity and Related Metabolic and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannataro, R.; Abrego-Guandique, D.M.; Straface, N.; Cione, E. Omega-3 and Sports: Focus on Inflammation. Life 2024, 14, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, N.M.; Oliveira, M.V.B.; Quesada, K.; Haber, J.F.d.S.; José Tofano, R.; Rubira, C.J.; Zutin, T.L.M.; Direito, R.; Pereira, E.d.S.B.M.; de Oliveira, C.M.; et al. Assessing Omega-3 Therapy and Its Cardiovascular Benefits: What About Icosapent Ethyl? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. Contributions of Dietary Patterns and Factors to Regulation of Rheumatoid Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.W.; Quek, S.-Y.; Lu, S.-P.; Chen, J.-H. Potential Benefits of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (N3PUFAs) on Cardiovascular Health Associated with COVID-19: An Update for 2023. Metabolites 2023, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antraco, V.J.; Hirata, B.K.S.; de Jesus Simão, J.; Cruz, M.M.; da Silva, V.S.; da Cunha de Sá, R.D.C.; Abdala, F.M.; Armelin-Correa, L.; Alonso-Vale, M.I.C. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Prevent Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) and Stimulate Adipogenesis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgendorf, K.I.; Johnson, C.T.; Mezger, A.; Rice, S.L.; Norris, A.M.; Demeter, J.; Greenleaf, W.J.; Reiter, J.F.; Kopinke, D.; Jackson, P.K. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Activate Ciliary FFAR4 to Control Adipogenesis. Cell 2019, 179, 1289–1305.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mahri, S.; Malik, S.S.; Al Ibrahim, M.; Haji, E.; Dairi, G.; Mohammad, S. Free Fatty Acid Receptors (FFARs) in Adipose: Physiological Role and Therapeutic Outlook. Cells 2022, 11, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szukiewicz, D. Potential Therapeutic Exploitation of G Protein-Coupled Receptor 120 (GPR120/FFAR4) Signaling in Obesity-Related Metabolic Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-J.; Yang, J.-T.; Chen, C.-Y.; Ajuwon, K.M.; Chen, S.-E.; Su, N.-W.; Chen, Y.-S.; Mersmann, H.J.; Ding, S.-T. Docosahexaenoic Acid Increases Accumulation of Adipocyte Triacylglycerol through Up-Regulation of Lipogenic Gene Expression in Pigs. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albracht-Schulte, K.; Kalupahana, N.S.; Ramalingam, L.; Wang, S.; Rahman, S.M.; Robert-McComb, J.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome: A Mechanistic Update. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 58, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nartey, M.N.N.; Shimizu, H.; Sugiyama, H.; Higa, M.; Syeda, P.K.; Nishimura, K.; Jisaka, M.; Yokota, K. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Induces the Inhibition of Adipogenesis by Reducing the Effect of PPARγ Activator and Mediating PKA Activation and Increased COX-2 Expression in 3T3-L1 Cells at the Differentiation Stage. Life 2023, 13, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zając-Grabiec, A.; Bartusek, K.; Sroczyńska, K.; Librowski, T.; Gdula-Argasińska, J. Effect of Eicosapentaenoic Acid Supplementation on Murine Preadipocytes 3T3-L1 Cells Activated with Lipopolysaccharide and/or Tumor Necrosis Factor-α. Life 2021, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-K.; Della-Fera, M.; Lin, J.; Baile, C.A. Docosahexaenoic Acid Inhibits Adipocyte Differentiation and Induces Apoptosis in 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2965–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Shin, H.Y. Deciphering the Potential Role of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in Obesity-Associated Metabolic Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Simão, J.; de Sousa Bispo, A.F.; Plata, V.T.G.; Armelin-Correa, L.M.; Alonso-Vale, M.I.C. Fish Oil Supplementation Mitigates High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity: Exploring Epigenetic Modulation and Genes Associated with Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Mice. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yu, L.; Zahr, T.; Li, X.; Kim, T.-W.; Qiang, L. PPARγ Acetylation in Adipocytes Exacerbates BAT Whitening and Worsens Age-Associated Metabolic Dysfunction. Cells 2023, 12, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saban Güler, M.; Yıldıran, H.; Seymen, C.M. Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Adipose Tissue: Histological, Metabolic, and Gene Expression Analyses in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ling, W. Fish Oil Supplementation Inhibits Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Improves Insulin Resistance: Involvement of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Cebrián, S.; Bustos, M.; Marti, A.; Fernández-Galilea, M.; Martinez, J.A.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Inhibits Tumour Necrosis Factor-α-Induced Lipolysis in Murine Cultured Adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, M.J.; Hasty, A.H.; Saraswathi, V. The Role of Adipose Tissue in Mediating the Beneficial Effects of Dietary Fish Oil. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakers, A.; De Siqueira, M.K.; Seale, P.; Villanueva, C.J. Adipose-Tissue Plasticity in Health and Disease. Cell 2022, 185, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.K.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Doh, J.; Park, J.-H.; Jung, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.-H. Lipid Remodeling of Adipose Tissue in Metabolic Health and Disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1955–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delpino, F.M.; Figueiredo, L.M.; da Silva, B.G.C. Effects of Omega-3 Supplementation on Body Weight and Body Fat Mass: A Systematic Review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 44, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vackova, E.; Bosnakovski, D.; Bjørndal, B.; Yonkova, P.; Grigorova, N.; Ivanova, Z.; Penchev, G.; Simeonova, G.; Miteva, L.; Milanova, A.; et al. N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Provoke a Specific Transcriptional Profile in Rabbit Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in Vitro. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorčević, M.; Hodson, L. The Effect of Marine Derived N-3 Fatty Acids on Adipose Tissue Metabolism and Function. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Bian, C.; Ji, H.; Ji, S.; Sun, J. DHA Induces Adipocyte Lipolysis through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the cAMP/PKA Signaling Pathway in Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Anim. Nutr. 2023, 13, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniyappa, R. Vascular Insulin Resistance and Free Fatty Acids: The Micro-Macro Circulation Nexus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, e1671–e1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Hoff, A.; Her, T.K.; Ariyaratne, G.; Gutiérrez, R.-L.; Tahawi, M.H.D.N.; Rajagopalan, K.S.; Brown, M.R.; Omori, K.; Lewis-Brinkman, S.; et al. Lipotoxicity Induces β-Cell Small Extracellular Vesicle–Mediated β-Cell Dysfunction in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2025, 166, bqaf067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plötz, T.; Lenzen, S. Mechanisms of Lipotoxicity-Induced Dysfunction and Death of Human Pancreatic Beta Cells under Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Conditions. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahmer, N.; Walther, T.C.; Farese, R.V. The Pathogenesis of Hepatic Steatosis in MASLD: A Lipid Droplet Perspective. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e198334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.Y.; Calder, P.C. The Differential Effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Docosahexaenoic Acid on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: An Updated Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1423228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, J.P.; Palatnic, L.; Lakshmanan, S.; Drago, T.; Bhogal, J.; Roy, S.K.; Bhatt, D.L.; Budoff, M.J.; Nelson, J.R. Effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid vs Eicosapentaenoic/Docosahexaenoic Acids on Cardiovascular Mortality. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeloudes, C.; Christodoulides, S.; Christodoulou, P.; Kyriakou, T.-C.; Patrikios, I.; Stephanou, A. Variability in the Clinical Effects of the Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids DHA and EPA in Cardiovascular Disease—Possible Causes and Future Considerations. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Su, C.-W.; Liu, Y.; Cao, T.; Hao, L.; Wang, M.; Kang, J.X. Increased Lipogenesis Is Critical for Self-Renewal and Growth of Breast Cancer Stem Cells: Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Stem Cells 2021, 39, 1660–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Molenaar, A.J.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Y. Mode and Mechanism of Action of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Unsaturated Fatty Acids in Chronic Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Yuan, X.; Zeng, C.; Sun, J.; Kaneko, G.; Ji, H. Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Inhibits Abdominal Fat Accumulation by Promoting Adipocyte Apoptosis through PPARγ-LC3-BNIP3 Pathway-Mediated Mitophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2024, 1869, 159425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Rodrigues, J.; Philippsen, H.K.; Dolabela, M.F.; Nagamachi, C.Y.; Pieczarka, J.C. The Potential of DHA as Cancer Therapy Strategies: A Narrative Review of In Vitro Cytotoxicity Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, C.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Amakye, W.K.; Mao, L. DHA Increases Adiponectin Expression More Effectively than EPA at Relative Low Concentrations by Regulating PPARγ and Its Phosphorylation at Ser273 in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorova, N.; Ivanova, Z.; Vachkova, E.; Petrova, V.; Penev, T. DHA-Provoked Reduction in Adipogenesis and Glucose Uptake Could Be Mediated by Gps2 Upregulation in Immature 3T3-L1 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, V.; Peroni, O.; Letexier, D.; Ray, H.; Beylot, M. Metabolism of Lipids in Human White Adipocyte. Diabetes Metab. 2004, 30, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanadha, S.; Londos, C. Determination of Lipolysis in Isolated Primary Adipocytes. In Adipose Tissue Protocols; Yang, K., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 299–306. ISBN 978-1-59745-245-8. [Google Scholar]

- Houten, S.M.; Violante, S.; Ventura, F.V.; Wanders, R.J.A. The Biochemistry and Physiology of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation and Its Genetic Disorders. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, A.; Abedinzade, M. Comparison of In Vitro and In Situ Methods for Studying Lipolysis. ISRN Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 205385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowker-Key, P.D.; Jadi, P.K.; Gill, N.B.; Hubbard, K.N.; Elshaarrawi, A.; Alfatlawy, N.D.; Bettaieb, A. A Closer Look into White Adipose Tissue Biology and the Molecular Regulation of Stem Cell Commitment and Differentiation. Genes 2024, 15, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.D.; Hsu, C.-H.; Wang, X.; Sakai, S.; Freeman, M.W.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Spiegelman, B.M. C/EBPα Induces Adipogenesis through PPARγ: A Unified Pathway. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemelä, S.; Miettinen, S.; Sarkanen, J.-R.; Ashammakhi, N. Adipose Tissue and Adipocyte Differentiation: Molecular and Cellular Aspects and Tissue Engineering Applications. Top. Tissue Eng. 2008, 4, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Mao, S.; Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C. PPARs-Orchestrated Metabolic Homeostasis in the Adipose Tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzaabi, M.; Khalili, M.; Sultana, M.; Al-Sayegh, M. Transcriptional Dynamics and Key Regulators of Adipogenesis in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells: Insights from Robust Rank Aggregation Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Siqueira, M.K.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Ahn, I.S.; Tamboline, M.; Hildreth, A.D.; Larios, J.; Schcolnik-Cabrera, A.; Nouhi, Z.; et al. PPARγ-Dependent Remodeling of Translational Machinery in Adipose Progenitors Is Impaired in Obesity. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriboonaied, P.; Phuangbubpha, P.; Saetan, P.; Charoensuksai, P.; Charoenpanich, A. Dual Modulation of Adipogenesis and Apoptosis by PPARG Agonist Rosiglitazone and Antagonist Betulinic Acid in 3T3-L1 Cells. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschoal, V.A.; Walenta, E.; Talukdar, S.; Pessentheiner, A.R.; Osborn, O.; Hah, N.; Chi, T.J.; Tye, G.L.; Armando, A.M.; Evans, R.M.; et al. Positive Reinforcing Mechanisms between GPR120 and PPARγ Modulate Insulin Sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 1173–1188.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodhi, I.J.; Yin, L.; Jensen-Urstad, A.P.L.; Funai, K.; Coleman, T.; Baird, J.H.; El Ramahi, M.K.; Razani, B.; Song, H.; Fu-Hsu, F.; et al. Inhibiting Adipose Tissue Lipogenesis Reprograms Thermogenesis and PPARγ Activation to Decrease Diet-Induced Obesity. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes-Vieira, P.M.; Saghatelian, A.; Kahn, B.B. GLUT4 Expression in Adipocytes Regulates De Novo Lipogenesis and Levels of a Novel Class of Lipids with Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1808–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgonovi, S.M.; Iametti, S.; Di Nunzio, M. Docosahexaenoic Acid as Master Regulator of Cellular Antioxidant Defenses: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-E.; Ge, K. Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation of PPARγ Expression during Adipogenesis. Cell Biosci. 2014, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambele, M.A.; Dhanraj, P.; Giles, R.; Pepper, M.S. Adipogenesis: A Complex Interplay of Multiple Molecular Determinants and Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guixà-González, R.; Javanainen, M.; Gómez-Soler, M.; Cordobilla, B.; Domingo, J.C.; Sanz, F.; Pastor, M.; Ciruela, F.; Martinez-Seara, H.; Selent, J. Membrane Omega-3 Fatty Acids Modulate the Oligomerisation Kinetics of Adenosine A2A and Dopamine D2 Receptors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Y.; Xiao, B.; Cui, D.; Lin, Y.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Cao, M.-J.; Liu, J. Antioxidant Activity of Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) and Its Regulatory Roles in Mitochondria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Wu, M.; Wu, T.; Ji, Y.; Jin, L.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, A.; Ding, G.; et al. Reduction of NADPH Oxidase 4 in Adipocytes Contributes to the Anti-Obesity Effect of Dihydroartemisinin. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouche, S.; Mkaddem, S.B.; Wang, W.; Katic, M.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Carnesecchi, S.; Steger, K.; Foti, M.; Meier, C.A.; Muzzin, P.; et al. Reduced Expression of the NADPH Oxidase NOX4 Is a Hallmark of Adipocyte Differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2007, 1773, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evseeva, M.N.; Balashova, M.S.; Kulebyakin, K.Y.; Rubtsov, Y.P. Adipocyte Biology from the Perspective of In Vivo Research: Review of Key Transcription Factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormand, A.; Berggreen, C.; Amar, L.; Henriksson, E.; Lund, I.; Albinsson, S.; Göransson, O. LKB1 Signalling Attenuates Early Events of Adipogenesis and Responds to Adipogenic Cues. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 53, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Wan, L.; Chen, P.; Lu, W. Docosahexaenoic Acid Activates the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway to Alleviate Impairment of Spleen Cellular Immunity in Intrauterine Growth Restricted Rat Pups. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 4987–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchetti, G.; Clementi, M.E.; Sampaolese, B.; Serantoni, C.; Abeltino, A.; De Spirito, M.; Sasson, S.; Maulucci, G. Metabolic Imaging and Molecular Biology Reveal the Interplay between Lipid Metabolism and DHA-Induced Modulation of Redox Homeostasis in RPE Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Dong, Q.; Bridges, D.; Raghow, R.; Park, E.A.; Elam, M.B. Docosahexaenoic Acid Inhibits Proteolytic Processing of Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein-1c (SREBP-1c) via Activation of AMP-Activated Kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1851, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, U. Adipose Tissue Expansion in Obesity, Health, and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1188844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kounatidis, D.; Vallianou, N.G.; Rebelos, E.; Kouveletsou, M.; Kontrafouri, P.; Eleftheriadou, I.; Diakoumopoulou, E.; Karampela, I.; Tentolouris, N.; Dalamaga, M. The Many Facets of PPAR-γ Agonism in Obesity and Associated Comorbidities: Benefits, Risks, Challenges, and Future Directions. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, Y.J.; Wang, Y.; Dagur, P.; Scott, N.; Cero, C.; Long, K.T.; Nguyen, N.; Cypess, A.M.; Rane, S.G. TGF-β Antagonism Synergizes with PPARγ Agonism to Reduce Fibrosis and Enhance Beige Adipogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2024, 90, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajirahimkhan, A.; Brown, K.A.; Clare, S.E.; Khan, S.A. SREBP1-Dependent Metabolism as a Potential Target for Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. Cancers 2025, 17, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lin, X.; Wang, G. Targeting SREBP-1-Mediated Lipogenesis as Potential Strategies for Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 952371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qiu, S. Activation of GPR120 Promotes the Metastasis of Breast Cancer through the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Anticancer Drugs 2019, 30, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T.; Takakuwa, R.; Marchand, S.; Dentz, E.; Bornert, J.-M.; Messaddeq, N.; Wendling, O.; Mark, M.; Desvergne, B.; Wahli, W.; et al. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Is Required in Mature White and Brown Adipocytes for Their Survival in the Mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4543–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, E.; Sinclair, A.J.; Cameron-Smith, D. Comparative Actions of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on in-Vitro Lipid Droplet Formation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2013, 89, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, J.B.; van Harmelen, V.; Alberti-Huber, C.E.; Hauner, H. Albumin Inhibits Adipogenesis and Stimulates Cytokine Release from Human Adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 291, C27–C33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.T.; Fu, J.; Wang, Y.-K.; Desai, R.A.; Chen, C.S. Assaying Stem Cell Mechanobiology on Microfabricated Elastomeric Substrates with Geometrically Modulated Rigidity. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Jang, D.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.S. Anti-Obesity Effect of Morus Bombycis Root Extract: Anti-Lipase Activity and Lipolytic Effect. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Liang, J.F.; Ko, K.S.; Kim, S.W.; Yang, V.C. Low Molecular Weight Protamine as an Efficient and Nontoxic Gene Carrier: In Vitro Study. J. Gene Med. 2003, 5, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesi, F.; Ferioli, F.; Caboni, M.F.; Boschetti, E.; Nunzio, M.D.; Verardo, V.; Valli, V.; Astolfi, A.; Pession, A.; Bordoni, A. Phytosterol Supplementation Reduces Metabolic Activity and Slows Cell Growth in Cultured Rat Cardiomyocytes. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, P.A.R.; Camargo, D.E.G.; Ondo-Méndez, A.; Gómez-Alegría, C.J. A Colorimetric Bioassay for Quantitation of Both Basal and Insulin-Induced Glucose Consumption in 3T3-L1 Adipose Cells. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnhold, S.; Elashry, M.I.; Klymiuk, M.C.; Geburek, F. Investigation of Stemness and Multipotency of Equine Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (ASCs) from Different Fat Sources in Comparison with Lipoma. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Liu, W.-H.; Li, N.; Liang, H.; Hung, W.; Jiang, Q.; Cheng, R.; Shen, X.; He, F. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei K56 Inhibits Lipid Accumulation in Adipocytes by Promoting Lipolysis. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 3511–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhou, G.-C.; Liu, S.-J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.-L.; Xu, G.-Y.; Li, T.-F.; Meng, G.-Q.; Xue, J.-Y. Selection and Validation of Reference Genes for qRT-PCR Analysis of Gene Expression in Tropaeolum Majus (Nasturtium). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, I.K.; Lee, J.S.; Yoon, J.-W.; Kang, S.-S. Skimmed Milk Fermented by Lactic Acid Bacteria Inhibits Adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 Pre-Adipocytes by Downregulating PPARγ via TNF-α Induction in Vitro. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 8605–8614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ge, X.; Bai, G.; Chen, C. Selection of Reference Genes for Expression Normalization by RT-qPCR in Dracocephalum moldavica L. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 6284–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate Normalization of Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR Data by Geometric Averaging of Multiple Internal Control Genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellemans, J.; Mortier, G.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F.; Vandesompele, J. qBase Relative Quantification Framework and Software for Management and Automated Analysis of Real-Time Quantitative PCR Data. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stages/Groups | DC | DM-eth | MM-eth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1–2 (48 h) | INDUCTION in ADM | INDUCTION in ADM + 0.05% (v/v) ethanol | INDUCTION in ADM |

| Day 3–9 | Preadipocyte maturation in AMM | Maturation of preadipocytes in AMM + 0.05% (v/v) ethanol | Maturation of preadipocytes in AMM |

| Day 10–18 | Mature adipocyte growth in AMM | Growth of mature adipocytes in AMM | Growth of mature adipocytes in AMM + 0.05% (v/v) ethanol |

| Stages/Groups | NC | DC | DM_PA/DM_DHA | MM_PA/MM_DHA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 (24 h) | Growth arrest at 100% confluence | |||

| Day 1–2 (48 h) | Preadipocyte culture in BM | INDUCTION in ADM | INDUCTION in ADM + 60 µM DHA | INDUCTION in ADM |

| Day 3–9 | Preadipocyte maturation in AMM | Preadipocyte maturation in AMM + 60 µM PA or DHA | Preadipocyte maturation in AMM | |

| Day 10–18 | Mature adipocytes cultured in AMM | Mature adipocytes cultured in AMM | Mature adipocytes cultured in AMM + 60 µM PA or DHA | |

| Abbreviation | Full Name | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pparγ NM_001127330.2 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | AGGGCGATCTTGACAGGAAA | CGAAACTGGCACCCTTGAAA | 164 |

| Srebf1 NM_011480.4 | Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 | TTGACACGTTTCTTCCTGAGC | CAGTTCAACGCTCGCTCTAG | 239 |

| Gpr120 NM_181748.2 | G protein-coupled receptor 120 | CCAACCGCATAGGAGAAATC | CAAGCTCAGCGTAAGCCTCT | 140 |

| Pnpla2 NM_001163689.1 | Patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 2 | CCTTCACCATCCGCTTGTTG | CCCAGTGAGAGGTTGTTTCG | 250 |

| Lipe NM_010719.5 | Lipase, hormone-sensitive | ACGAGCCCTACCTCAAGAAC | GCTCTCCAGTTGAACCAAGC | 165 |

| Lep NM_146146.3 | Leptin receptor, transcript variant 1 | GAGCCCCAAACAATGCCTC | TGTCCCAGTTTACACCTAGCT | 231 |

| Adipoq NM_028320.4 | Adiponectin receptor 1 | TCCCGTATGATGTGCTTCCT | AGCACAAAACCAAGCAGATGT | 157 |

| CPT1 NM_153679.2 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 | GTGTACTTCCAACTACGTCAGC | GCGATACAGGAGCAGGGTAT | 169 |

| FABP4 NM_024406.4 | Fatty acid-binding protein 4 | AACTGGGCGTGGAATTCGAT | CCACCAGCTTGTCACCATCT | 150 |

| Fasn NM_007988.3 | Fatty acid synthase | CTGAAGCCGAACACCTCTGT | GGGAATGTTACACCTTGCTCCT | 218 |

| Slc2a4 NM_009204.2 | Solute carrier family 2 member 4 | CGTTGGTCTCGGTGCTCTTA | AGCTCTGCCACAATGAACCA | 220 |

| Hmbs NM_001110251.1 | Hydroxymethylbilane synthase | CCTGAAGGATGTGCCTACCA | CCACTCGAATCACCCTCATCT | 175 |

| 36b4 NM_007475.5 | Ribosomal protein, large, P0 | TTATAACCCTGAAGTGCTCGAC | CGCTTGTACCCATTGATGATG | 147 |

| Hprt NM_013556.2 | Hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase | ACAGGCCAGACTTTGTTGGA | ACTTGCGCTCATCTTAGGCT | 150 |

| 18S NR_046271.1 | 18S ribosomal RNA | ATGCGGCGGCGTTATTCC | GCTATCAATCTGTCAATCCTGTCC | 204 |

| Actb NM_007393.5 | β-actin | CCTCTATGCCAACACAGTGC | GTACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCC | 211 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grigorova, N.; Ivanova, Z.; Tacheva, T.; Vachkova, E.; Georgiev, I.P. DHA Modulates Pparγ Gene Expression Depending on the Maturation Stage of 3T3-L1 Adipocytes at Time of Exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311514

Grigorova N, Ivanova Z, Tacheva T, Vachkova E, Georgiev IP. DHA Modulates Pparγ Gene Expression Depending on the Maturation Stage of 3T3-L1 Adipocytes at Time of Exposure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311514

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrigorova, Natalia, Zhenya Ivanova, Tanya Tacheva, Ekaterina Vachkova, and Ivan Penchev Georgiev. 2025. "DHA Modulates Pparγ Gene Expression Depending on the Maturation Stage of 3T3-L1 Adipocytes at Time of Exposure" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311514

APA StyleGrigorova, N., Ivanova, Z., Tacheva, T., Vachkova, E., & Georgiev, I. P. (2025). DHA Modulates Pparγ Gene Expression Depending on the Maturation Stage of 3T3-L1 Adipocytes at Time of Exposure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311514