Thyroid Response to Peripheral Endocrine Factors: Neuropeptide Y Influences Thyroid Function in the Reptile Podarcis siculus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

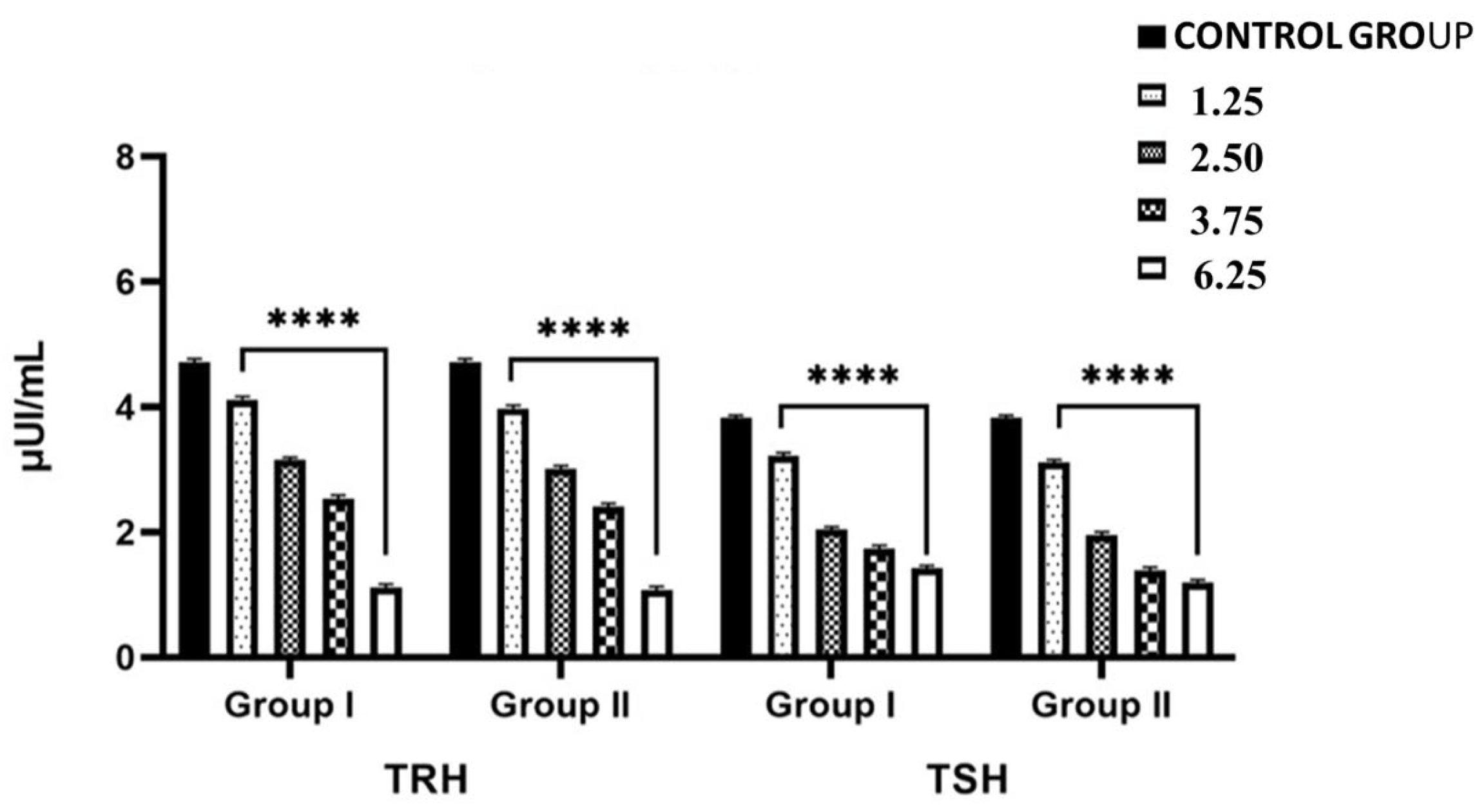

2.1. Effects of NPY Administration on Circulating Serum Levels of TRH and TSH

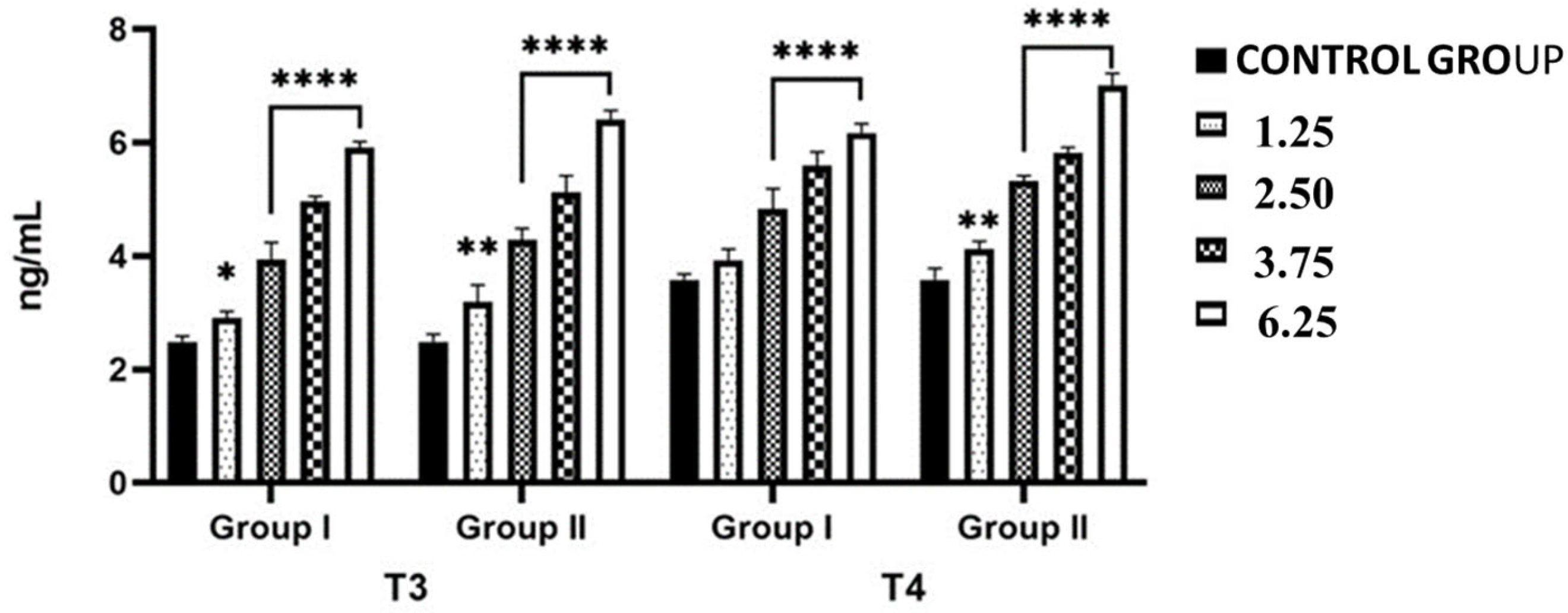

2.2. Effects of NPY Administration on Circulating Serum Levels of Thyroid Hormones

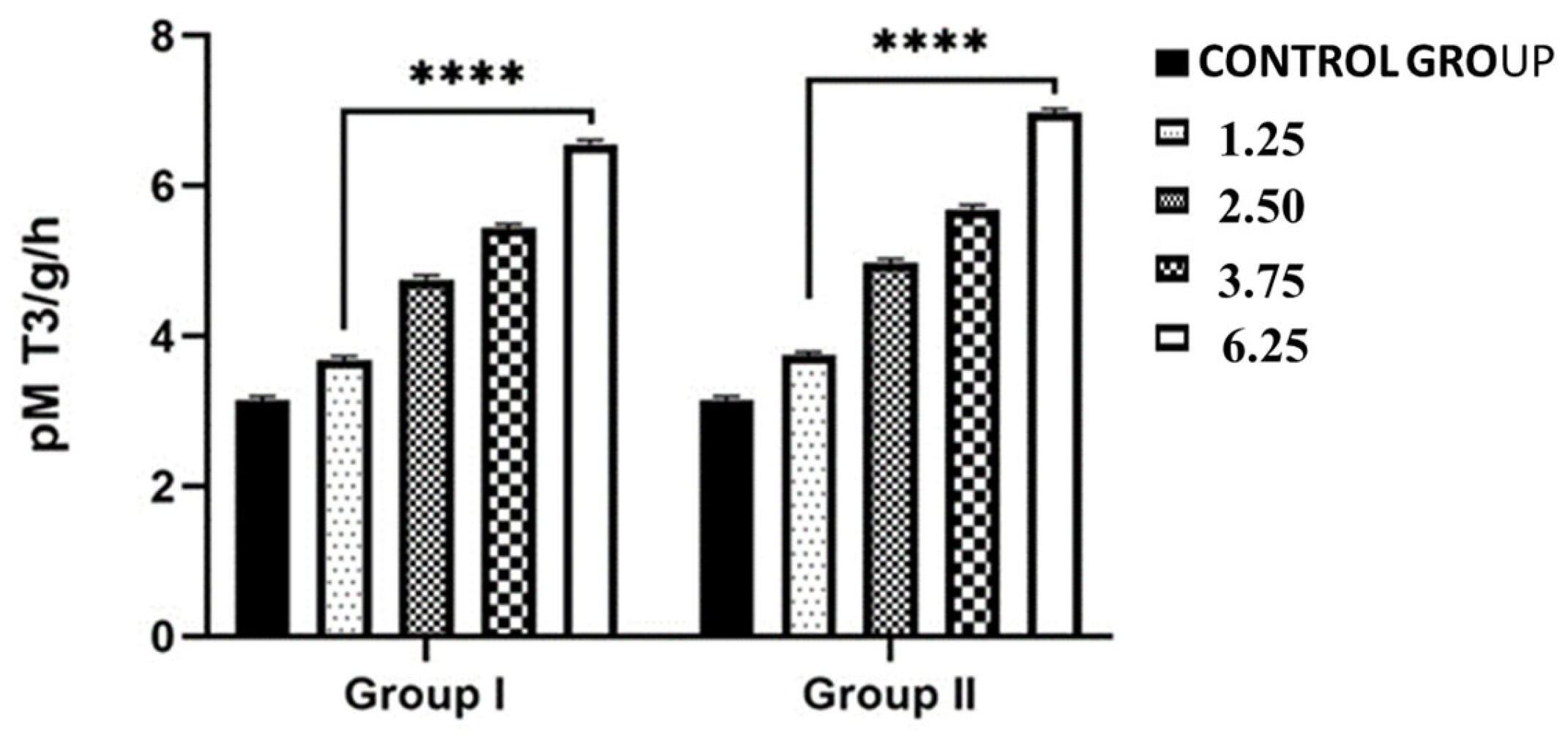

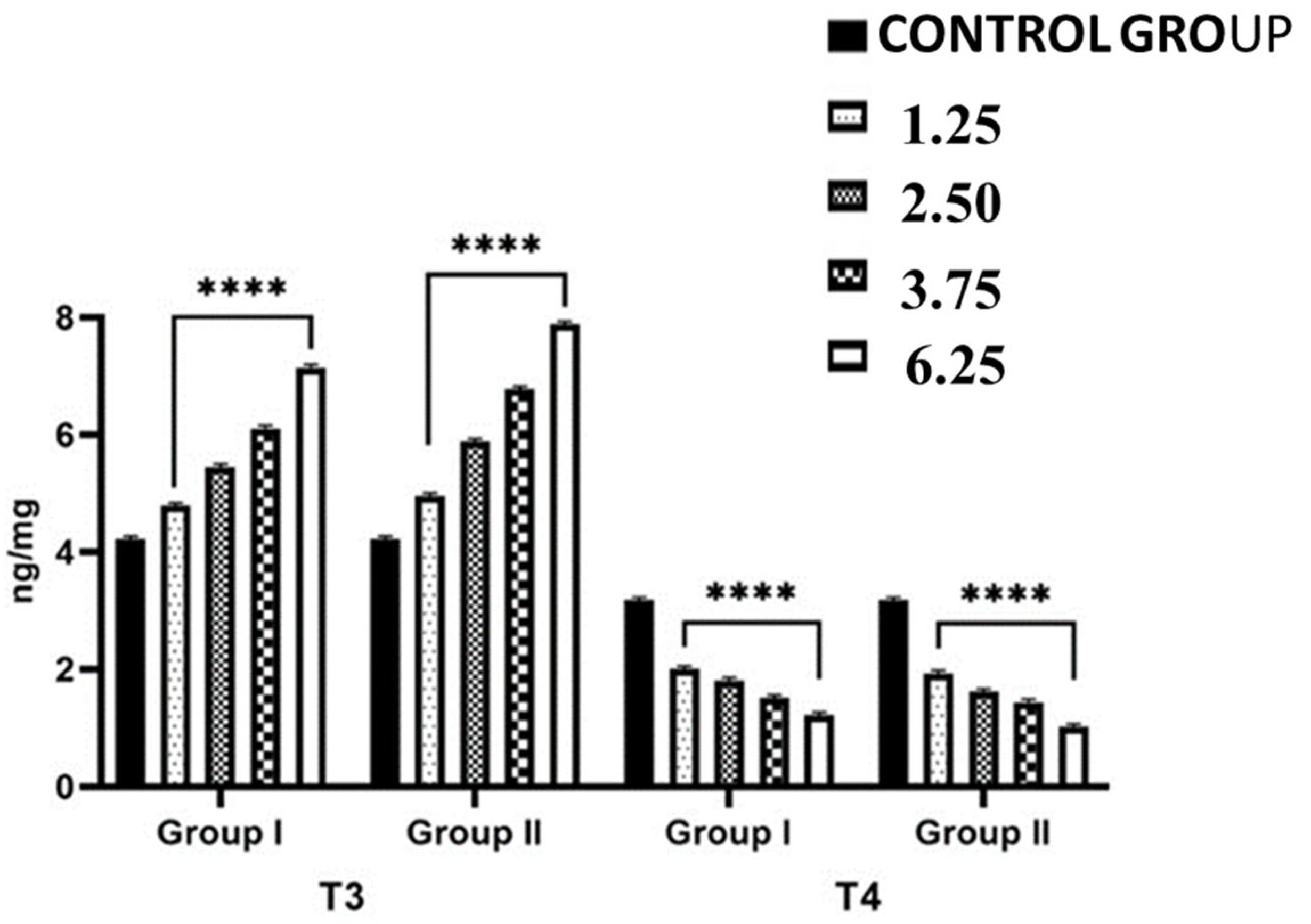

2.3. Effects of NPY Administration on the Hepatic Expression Levels of 5-T4 ORD (Type II) Monodeiodinase Activity and T4 and T3 Contents

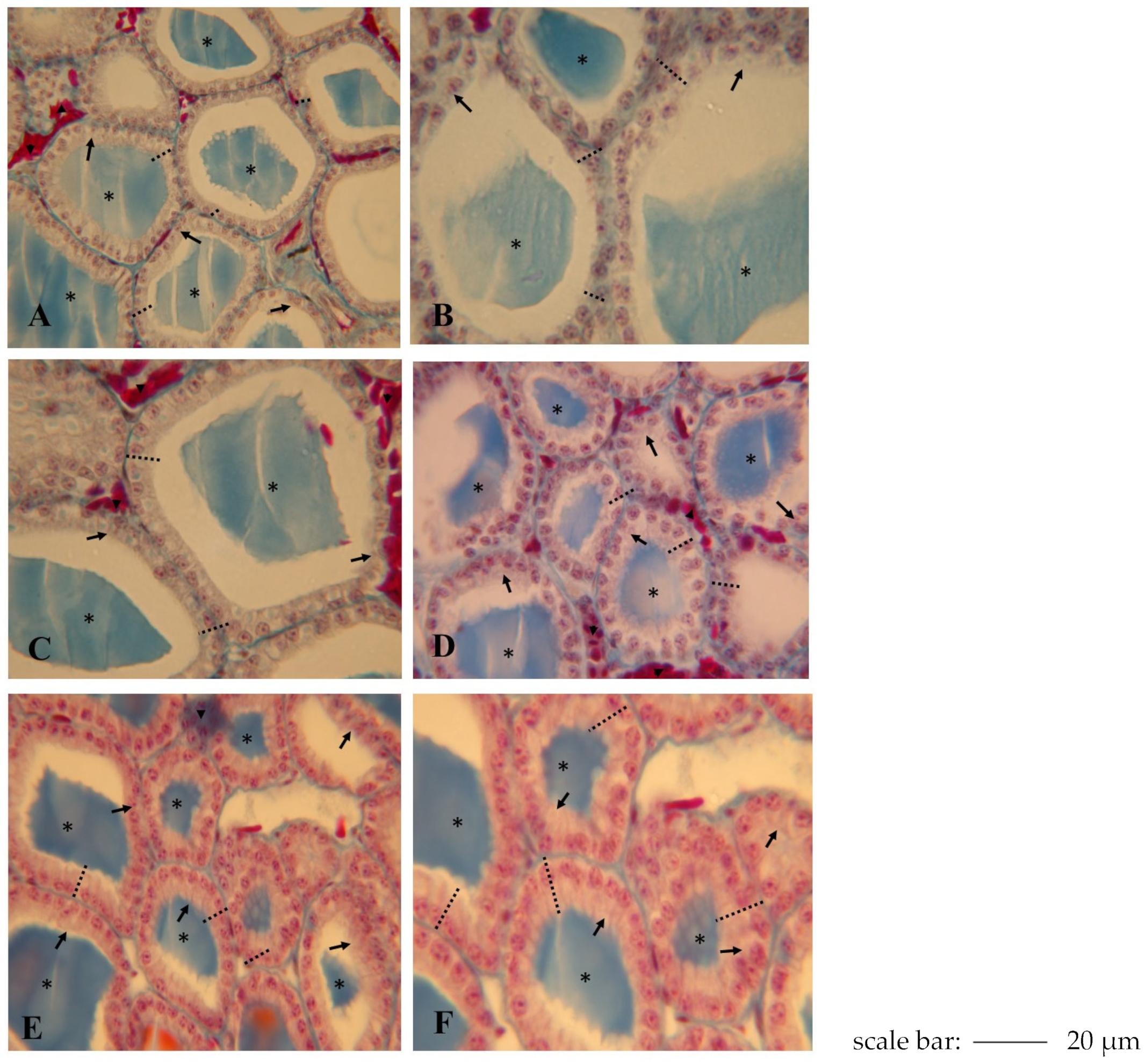

2.4. Effects of NPY Administration on Morphology of Thyroid Gland

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Experimental Procedures

4.2. Biochemical Analysis

4.2.1. Plasma TRH (Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone), TSH (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone) and Thyroid Hormones Assays

4.2.2. Hepatic Thyroid Hormones and 5′ ORD (Type II) Monodeiodinase Activity

4.3. Histological Analysis

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burbach, J.P.H. What Are Neuropeptides? In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press Inc.: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, J.C.; Guirado, S.; Puelles, L. Expression of calcium-binding proteins in the diencephalon of the lizard Psammodromus algirus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000, 427, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockaert, J.; Pin, J.P. Molecular tinkering of G protein-coupled receptors: An evolutionary success. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lage, R.; Vázquez, M.J.; Varela, L.; Saha, A.K.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Nogueiras, R.; Diéguez, C.; López, M. Ghrelin effects on neuropeptides in the rat hypothalamus depend on fatty acid metabolism actions on BSX but not on gender. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 2670–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley, D.B.; Schofield, P.; Jackson, J.; Herzog, H.; Christ, D. Crystal structures of human neuropeptide Y (NPY) and peptide YY (PYY). Neuropeptides 2022, 92, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puelles, L. A Segmental Morphological Paradigm for Understanding Vertebrate Forebrains (Part 2 of 2). Brain Behav. Evol. 1995, 46, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendahl, H. Embryologische und morphologische studien über das zwischenhirn beim huhn. Acta Zool. 1924, 5, 241–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüß, C.; Behr, V.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Illuminating the neuropeptide Y4 receptor and its ligand pancreatic polypeptide from a structural, functional, and therapeutic perspective. Neuropeptides 2024, 105, 102416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Capaldo, A.; Valiante, S.; Gay, F.; Sellitti, A.; Laforgia, V.; De Falco, M. Thyroid Hormones as Potential Early Biomarkers of Exposure to Nonylphenol in Adult Male Lizard (Podarcis sicula). Open Zool. J. 2010, 3, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Li, G.; Chow, B.K.C.; Cardoso, J.C.R. Neuropeptides and receptors in the cephalochordate: A crucial model for understanding the origin and evolution of vertebrate neuropeptide systems. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2024, 592, 112324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatemoto, K.; Carlquist, M.; Mutt, V. Neuropeptide Y—A novel brain peptide with structural similarities to peptide YY and pancreatic polypeptide. Nature 1982, 296, 659–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, E.S.; Abdelli, N.; Dridi, J.S.; Dridi, S. Avian Neuropeptide Y: Beyond Feed Intake Regulation. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudás, B.; Mihály, A.; Merchenthaler, I. Topography and associations of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone and neuropeptide Y-immunoreactive neuronal systems in the human diencephalon. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000, 427, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turi, G.F.; Liposits, Z.; Moenter, S.M.; Fekete, C.; Hrabovszky, E. Origin of Neuropeptide Y-Containing Afferents to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 4967–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borbély, É.; Scheich, B.; Helyes, Z. Neuropeptides in learning and memory. Neuropeptides 2013, 47, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körner, M.; Reubi, J.C. NPY receptors in human cancer: A review of current knowledge. Peptides 2007, 28, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, D.; Stichel, J.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Molecular recognition of the NPY hormone family by their receptors. Nutrition 2008, 24, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmann, F.; Holzer, P. Neuropeptide Y: A stressful review. Neuropeptides 2016, 55, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Ogino, Y.; Mashiko, S.; Ando, M. Modulation of neuropeptide Y receptors for the treatment of obesity. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2009, 19, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vona-Davis, L.C.; Mcfadden, D.W. NPY Family of Hormones: Clinical Relevance and Potential Use in Gastrointestinal Disease; Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2007; Volume 7, pp. 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulyaningsih, E.; Zhang, L.; Herzog, H.; Sainsbury, A. NPY receptors as potential targets for anti-obesity drug development. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bijker, M.S.; Herzog, H. The neuropeptide Y system: Pathophysiological and therapeuticimplications in obesity and cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 131, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, C.K.; Volkoff, H. Response of the thyroid axis and appetite-regulating peptides to fasting and overfeeding in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021, 528, 111229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefvand, S.; Hamidi, F.; Zendehdel, M.; Parham, A. Survey the Effect of Insulin on Modulating Feed Intake Via NPY Receptors in 5-Day-Old Chickens. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2020, 26, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, N.E.; Toorie, A.M.; Steger, J.S.; Sochat, M.M.; Hyner, S.; Perello, M.; Stuart, R.; Nillni, E.A. Mechanisms by which the orexigen NPY regulates anorexigenic α-MSH and TRH. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2013, 304, E640–E650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, T.; Aschkenasi, C.J.; Choi, B.J.; Lopez, M.E.; Lee, C.E.; Liu, H.; Hollenberg, A.N.; Friedman, J.M.; Elmquist, J.K. Neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor mRNA in rodent brain: Distribution and colocalization with melanocortin-4 receptor. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 482, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, M.; Volkoff, H. Thyrotropin Releasing Hormone (TRH) in goldfish (Carassius auratus): Role in the regulation of feeding and locomotor behaviors and interactions with the orexin system and cocaine-and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART). Horm. Behav. 2011, 59, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, C.K.; Volkoff, H. The Role of the Thyroid Axis in Fish. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 596585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabelik, D.; Hofmann, H.A. Comparative neuroendocrinology: A call for more study of reptiles! Horm. Behav. 2018, 106, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uetz, P.H.; Patel, M.; Gbadamosi, Z.; Nguyen, A.; Shoope, S. A Reference Database of Reptile Images. Taxonomy 2024, 4, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Laforgia, V.; Cavagnuolo, A.; Varano, L.; Virgilio, F. Annual variations of thyroid activity in the lizard Podarcis sicula (squamata, lacertidae). Ital. J. Zool. 2000, 67, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Virgilio, F.; De Falco, M.; Laforgia, V.; Varano, L.; Paolucci, M. Localization and role of leptin in the thyroid gland of the lizard Podarcis sicula (Reptilia, Lacertidae). J. Exp. Zool. A Comp. Exp. Biol. 2005, 303, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Virgilio, F.; Laforgia, V.; De Falco, M.; Valiante, S.; Prisco, M.; Andreuccetti, P.; Varano, L. Substance P: Immunohistochemical localization and possible function in thyroid gland of the lizard Podarcis sicula (Reptilia, Lacertidae). Ital. J. Zool. 2003, 70, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Capaldo, A.; Valiante, S.; Laforgia, V.; De Falco, M. Localization and role of galanin in the thyroid gland of Podarcis sicula lizard (Reptilia, Lacertide). J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 2009, 311, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgilio, F.; Sciarrillo, R.; Laforgia, V.; Varano, L. Response of the Thyroid Gland of the Lizard Podarcis sicula to Endothelin-1. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Comp. Exp. Biol. 2003, 296, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Laforgia, V.; Virgilio, F.; Longobardi, R.; Cavagnuolo, A.; Varano, L. Immunohistochemical localization of NPY, VIP and 5-HT in the thyroid gland of the lizard, Podarcis sicula. Eur. J. Histochem. 2001, 45, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-E-Sousa, R.H.; Rorato, R.; Hollenberg, A.N.; Vella, K.R. Regulation of Thyroid Hormone Levels by Hypothalamic Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons. Thyroid 2023, 33, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Aschkenasi, C.; Elias, C.F.; Chandrankunnel, A.; Nillni, E.A.; Bjørbæk, C.; Elmquist, J.K.; Flier, J.S.; Hollenberg, A.N. Transcriptional regulation of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone gene by leptin and melanocortin signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, B.; Soanez-Organis, J.G.; Vzquez-Medina, J.P.; Viscarra, J.A.; MacKenzie, D.S.; Crocker, D.E.; Ortiz, R.M. Prolonged food deprivation increases mRNA expression of deiodinase 1 and 2, and thyroid hormone receptor β-1 in a fasting-adapted mammal. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, N.; Seoane-Collazo, P.; Contreras, C.; Varela, L.; Villarroya, J.; Rial-Pensado, E.; Buqué, X.; Aurrekoetxea, I.; Delgado, T.C.; Vázquez-Martínez, R.; et al. Hypothalamic AMPK-ER Stress-JNK1 Axis Mediates the Central Actions of Thyroid Hormones on Energy Balance. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 212–229.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.; Sciarrillo, R.; Rosati, L.; Sellitti, A.; Barra, T.; De Luca, A.; Laforgia, V.; De Falco, M. Effects of alkylphenols mixture on the adrenal gland of the lizard Podarcis sicula. Chemosphere 2021, 258, 127239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Falzarano, A.; Gallicchio, V.; Carrella, F.; Chianese, T.; Mileo, A.; De Falco, M. Resorcinol as “endocrine disrupting chemical”: Are thyroid-related adverse effects adequately documented in reptiles? In vivo experimentation in lizard Podarcis siculus. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Falzarano, A.; Gallicchio, V.; Lallo, A.; Carrella, F.; Mileo, A.; Capaldo, A.; De Falco, M. The interaction between cardiovascular system and thyroid: Atrial natriuretic peptide in the thyroid function of the lizard Podarcis siculus: In vivo experiments and immunolocalisation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 296, 110259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Falzarano, A.; Gallicchio, V.; Mileo, A.; De Falco, M. Toxic Effects on Thyroid Gland of Male Adult Lizards (Podarcis siculus) in Contact with PolyChlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)-Contaminated Soil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Di Lorenzo, M.; Valiante, S.; Rosati, L.; De Falco, M. OctylPhenol (OP) Alone and in Combination with NonylPhenol (NP) Alters the Structure and the Function of Thyroid Gland of the Lizard Podarcis siculus. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 80, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Follicular cells (thyrocytes),

Follicular cells (thyrocytes),  Endothelial cells (blood capillaries), - - - Epithelial height.

Endothelial cells (blood capillaries), - - - Epithelial height.

Follicular cells (thyrocytes),

Follicular cells (thyrocytes),  Endothelial cells (blood capillaries), - - - Epithelial height.

Endothelial cells (blood capillaries), - - - Epithelial height.

| Doses NPY (nmol g Body Weight) | Epithelial Height (μm) | Follicular Diameter (μm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 h After Injection | 24 h After Injection | 2 h After Injection | 24 h After Injection | |

| Control Group | 11.1 ± 0.51 | 265 ± 25 | ||

| 1.25 | 11.3 ± 0.51 * | 11.5 ± 0.25 * | 266 ± 25 * | 269 ± 10 * |

| 2.50 | 12.3 ± 0.25 ** | 12.8 ± 0.10 ** | 225 ± 30 ** | 219 ± 20 ** |

| 3.75 | 16.5 ± 0.25 *** | 16.8 ± 0.05 *** | 185 ± 20 *** | 175 ± 15 *** |

| 6.25 | 24.3 ± 0.25 **** | 24.9 ± 0.05 **** | 159 ± 15 **** | 148 ± 15 **** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sciarrillo, R.; Lallo, A.; Carrella, F.; Gallicchio, V.; Mileo, A.; Valvano, B.S.; De Falco, M. Thyroid Response to Peripheral Endocrine Factors: Neuropeptide Y Influences Thyroid Function in the Reptile Podarcis siculus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311513

Sciarrillo R, Lallo A, Carrella F, Gallicchio V, Mileo A, Valvano BS, De Falco M. Thyroid Response to Peripheral Endocrine Factors: Neuropeptide Y Influences Thyroid Function in the Reptile Podarcis siculus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311513

Chicago/Turabian StyleSciarrillo, Rosaria, Assunta Lallo, Francesca Carrella, Vito Gallicchio, Aldo Mileo, Benedetta Sgangarella Valvano, and Maria De Falco. 2025. "Thyroid Response to Peripheral Endocrine Factors: Neuropeptide Y Influences Thyroid Function in the Reptile Podarcis siculus" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311513

APA StyleSciarrillo, R., Lallo, A., Carrella, F., Gallicchio, V., Mileo, A., Valvano, B. S., & De Falco, M. (2025). Thyroid Response to Peripheral Endocrine Factors: Neuropeptide Y Influences Thyroid Function in the Reptile Podarcis siculus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311513