Enrichment of Apple–Plum Fruit Mousse with Vitamin D3 and Sea Buckthorn Oil Using Pectin-Based Encapsulation: A Study of Physicochemical and Sensory Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

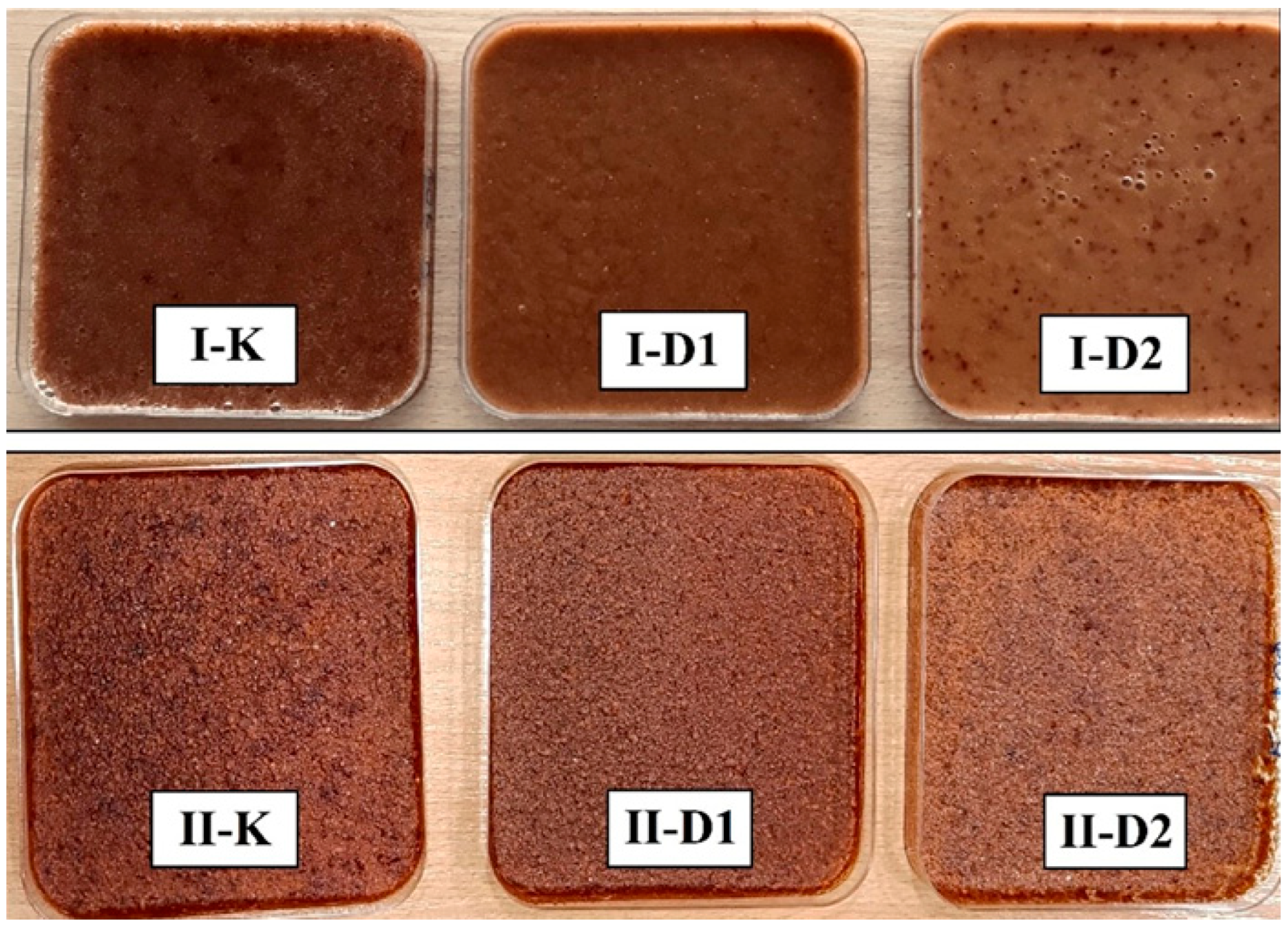

2.1. Visual Assessment of Fruit Mousses

2.2. Physicochemical Properties of Apple–Plum Mousses

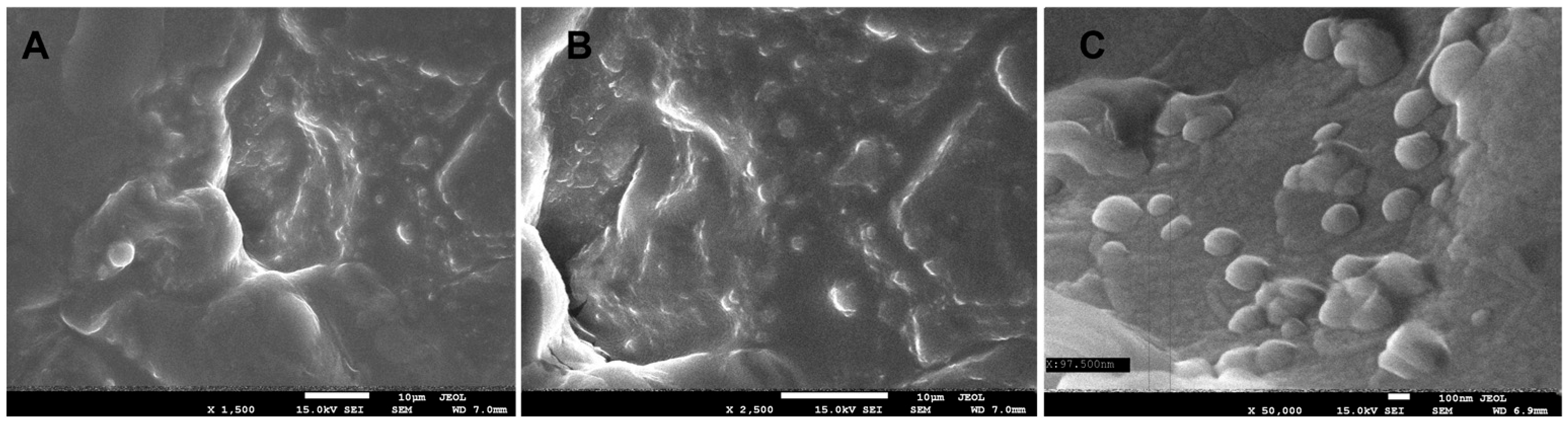

2.2.1. Morphology of the Fortified Mousse via Encapsulation

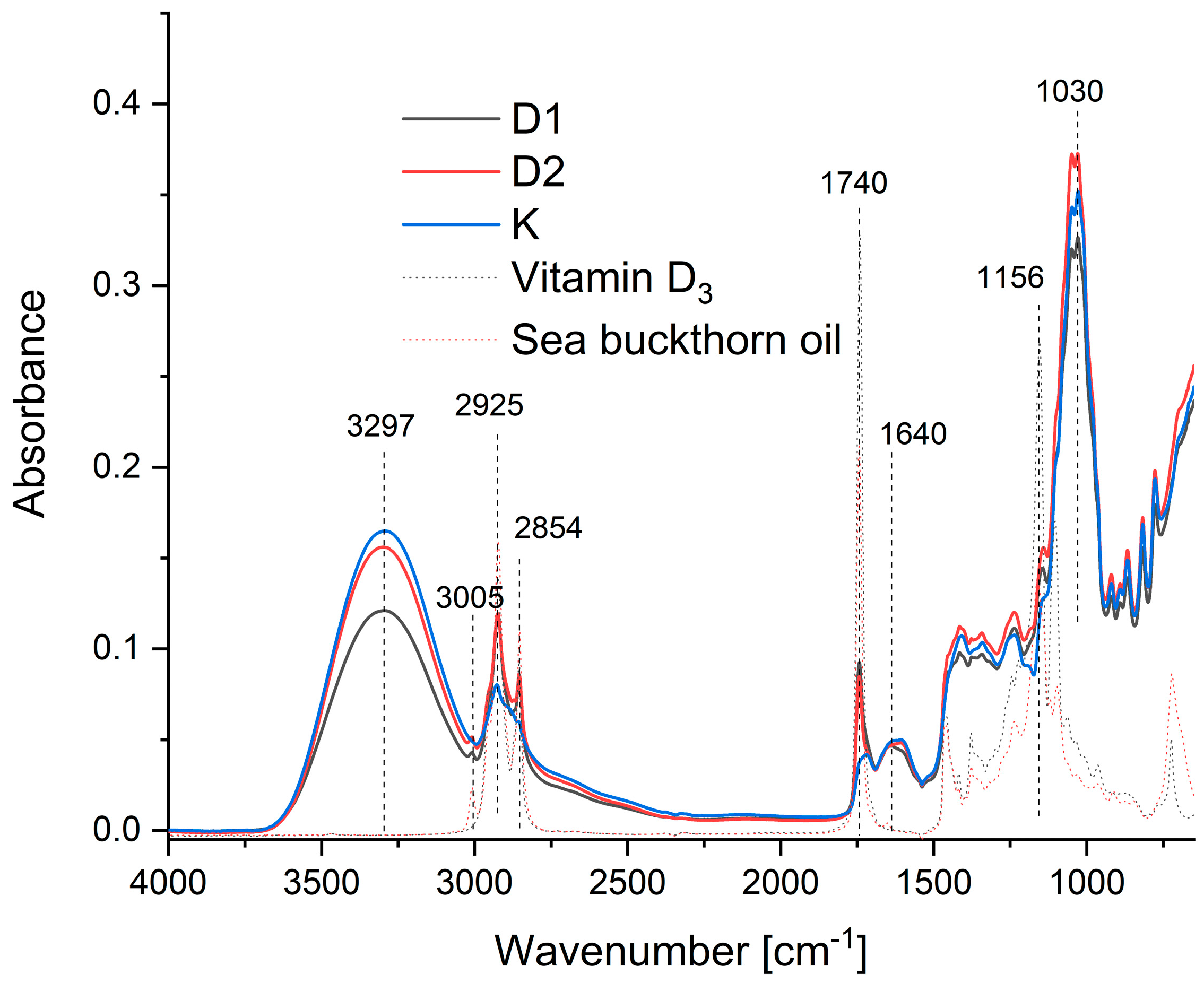

2.2.2. Structure of the Products

2.2.3. Colour of the Products

2.2.4. Texture of the Products

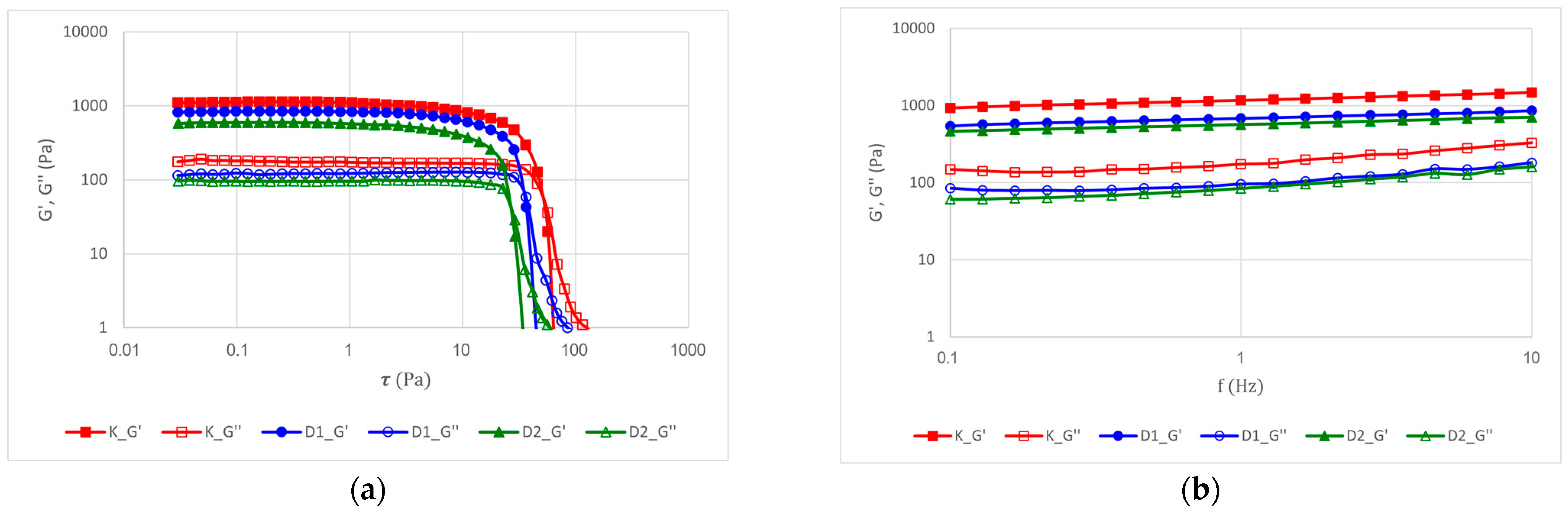

2.2.5. Rheological Properties of the Products

2.2.6. Fatty Acid Profile

| Fatty Acids [%] | Product | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| K | D1 | D2 | |

| C4:0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 0.69 ± 0.03 b | 0.58 ± 0.01 c |

| C8:0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 0.78 ± 0.04 b | 0.60 ± 0.10 c |

| C10:0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 0.62 ± 0.02 b | 0.55 ± 0.00 c |

| C10:1 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 0.18 ± 0.00 b | 0.14 ± 0.00 c |

| C14:0 | 1.61 ± 0.01 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b |

| C16:0 | 27.65 ± 0.03 a | 8.45 ± 0.03 b | 8.22 ± 0.02 c |

| C16:1 | 1.75 ± 0.03 a | 0.75 ± 0.00 b | 0.76 ± 0.01 b |

| C18:0 | 13.42 ± 0.00 a | 5.52 ± 0.02 b | 5.15 ± 0.00 c |

| C18:1 n-9 c | 33.21 ± 0.02 a | 25.23 ± 0.03 b | 24.98 ± 0.01 c |

| C18:1 n7 | 2.66 ± 0.00 a | 1.08 ± 0.01 b | 1.09 ± 0.01 b |

| C18:2 n-6 c | 16.90 ± 0.01 a | 55.13 ± 0.01 b | 56.39 ± 0.06 c |

| C18:3 n-6 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 0.39 ± 0.01 b | 0.38 ± 0.00 b |

| C18:3 n-3 | 2.81 ± 0.02 a | 1.18 ± 0.00 b | 1.17 ± 0.02 b |

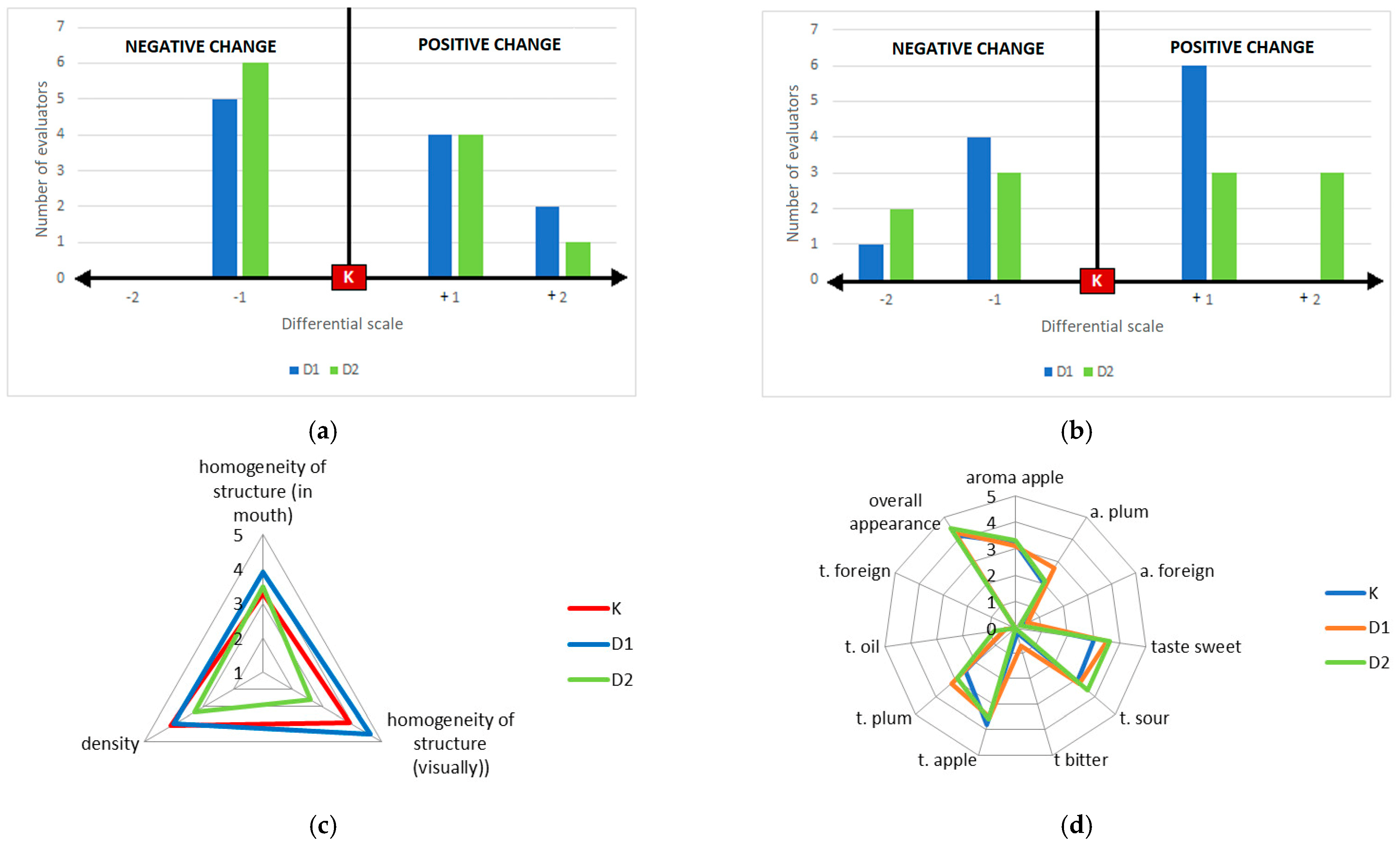

2.3. Sensory Analysis of Fruit Mousses

2.3.1. Sensory Quality of the Products

2.3.2. Sensory Quality Assessment by Ranking

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Fruit Mousses

3.2.1. Traditional Fruit Mousse

3.2.2. Fortified Mousse via Encapsulation

3.2.3. Fortified Mousse via Direct Addition

3.3. Physicochemical Analysis

3.3.1. Sample Preparation

3.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.3.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

3.3.4. Colour Measurement

3.3.5. Texture Analysis

3.3.6. Rheological Measurements

3.3.7. Fatty Acid Analysis

3.4. Sensory Analysis

3.4.1. Sensory Profiling

- (a)

- External Appearance: surface appearance, colour.

- (b)

- Consistency: homogeneity of consistency (visually), homogeneity of consistency (in the mouth), density.

- (c)

- Smell (Odour): apple, plum, foreign.

- (d)

- Taste: sweet, sour, bitter, apple, plum, oily, and foreign taste.

3.4.2. Ranking Test

3.4.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| QDA | Quantitative Descriptive Analysis |

| FAME | Fatty Acid Methyl Esters |

| GC-FID | Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionisation Detector |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| CIE Lab* | Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage Lightness and Color Coordinates |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| PN-EN | Polish Standard—European Norm |

Appendix A. Definitions of Descriptors Selected

| □ | □ | K | □ | □ | |||

| −2 | −1 | +1 | +2 | ||||

| unfavourable features | favourable features | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| inhomogeneity | very homogeneity | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| undetactable | strongly detactable | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| undetactable | strongly detactable | ||||||

References

- Galanakis, C.M. The Future of Food. Foods 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Pahmeyer, M.J.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Oboturova, N.P.; Taha, A. Consumer Behavior and Industry Implications. In The Age of Clean Label Foods; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 209–247. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Consumer Acceptance toward Functional Foods: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purkiewicz, A.; Wiśniewski, P.; Tańska, M.; Goksen, G.; Pietrzak-Fiećko, R. Effect of the Storage Conditions on the Microbiological Quality and Selected Bioactive Compound Content in Fruit Mousses for Infants and Young Children. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, N.; Robert, P.; Arancibia, C. Desserts Enriched with a Nanoemulsion Loaded with Vitamin D3 and Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Older People. Foods 2024, 13, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labaky, P.; Dahdouh, L.; Ricci, J.; Wisniewski, C.; Pallet, D.; Louka, N.; Grosmaire, L. Impact of Ripening on the Physical Properties of Mango Purees and Application of Simultaneous Rheometry and in Situ FTIR Spectroscopy for Rapid Identification of Biochemical and Rheological Changes. J. Food Eng. 2021, 300, 110507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buergy, A.; Rolland-Sabaté, A.; Leca, A.; Renard, C.M.G.C. Apple Puree’s Texture Is Independent from Fruit Firmness. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 145, 111324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, K.; Khachatryan, G.; Khachatryan, K.; Krystyjan, M. An Innovative Method for the Production of Yoghurt Fortified with Walnut Oil Nanocapsules and Characteristics of Functional Properties in Relation to Conventional Yoghurts. Foods 2023, 12, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopalan, V.K.; Gopakumar, L.R.; Kumaran, A.K.; Chatterjee, N.S.; Soman, V.; Peeralil, S.; Mathew, S.; McClements, D.J.; Nagarajarao, R.C. Encapsulation and Protection of Omega-3-Rich Fish Oils Using Food-Grade Delivery Systems. Foods 2021, 10, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, U.; Morozova, K.; Ferrentino, G.; Scampicchio, M. Apples and Apple By-Products: Antioxidant Properties and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezbedova, L.; McGhie, T.; Christensen, M.; Heyes, J.; Nasef, N.A.; Mehta, S. Onco-Preventive and Chemo-Protective Effects of Apple Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, G.; Ma, W.; Guo, M.; Ling, X.; Yu, D.; Zhou, W.; Li, L. Microencapsulation Protects the Biological Activity of Sea Buckthorn Seed Oil. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1043879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauser, S.; Murtaza, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Imran, M.; Kabir, K.; Najam, A.; An, U.Q.; Akram, S.; Fatima, H.; Batool, S.A.; et al. Apple Pomace, a Bioresource of Functional and Nutritional Components with Potential of Utilization in Different Food Formulations: A Review. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasina Sai, O.K.; Aravind, U.K.; Aravindakumar, C.T. Pectin-Based Encapsulation Systems for Bioactive Components. In Biomaterial in Microencapsulation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Feng, Y.; Chen, W.; Adie, K.; Liu, D.; Yin, Y. Citrus Pectin Modified by Microfluidization and Ultrasonication: Improved Emulsifying and Encapsulation Properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 70, 105322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woszczak, L.; Khachatryan, G.; Khachatryan, K.; Witczak, M.; Lenart-Boroń, A.; Stankiewicz, K.; Dworak, K.; Adamczyk, G.; Pawłowska, A.; Kapusta, I.; et al. Synthesis and Investigation of Physicochemical and Microbial Properties of Composites Containing Encapsulated Propolis and Sea Buckthorn Oil in Pectin Matrix. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zezulová, E.; Ondrášek, I.; Kiss, T.; Nečas, T. Qualitative and Nutritional Characteristics of Plum Cultivars Grown on Different Rootstocks. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Ye, S.; Wang, H.; Xing, S.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Pu, C.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Soluble Sugar, Organic Acid and Phenolic Composition and Flavor Evaluation of Plum Fruits. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotirić Akšić, M.; Tešić, Ž.; Kalaba, M.; Ćirić, I.; Pezo, L.; Lončar, B.; Gašić, U.; Dojčinović, B.; Tosti, T.; Meland, M. Breakthrough Analysis of Chemical Composition and Applied Chemometrics of European Plum Cultivars Grown in Norway. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Moghaddam, T.; Firoozzare, A. Investigating the Effect of Sensory Properties of Black Plum Peel Marmalade on Consumers Acceptance by Discriminant Analysis. Food Chem. X 2021, 11, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, A.; Ivanova, V.; Trusheva, B.; Kamenova-Nacheva, M.; Tabakov, S.; Simova, S. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of the Fruits of European Plum Cultivar “Čačanska Lepotica” Influenced by Different Rootstocks. Foods 2022, 11, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnafisah, R.Y.; Alragea, A.S.; Alzamil, M.K.; Alqahtani, A.S. The Impact and Efficacy of Vitamin D Fortification. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.F.; Souza, S. Formulation Strategies for Improving the Stability and Bioavailability of Vitamin D-Fortified Beverages: A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelli, V.; D’Incecco, P.; Pellegrino, L. Vitamin D Incorporation in Foods: Formulation Strategies, Stability and Bioaccessibility as Affected by the Food Matrix. Foods 2021, 10, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnywojtek, A.; Florek, E.; Pietrończyk, K.; Sawicka-Gutaj, N.; Ruchała, M.; Ronen, O.; Nixon, I.J.; Shaha, A.R.; Rodrigo, J.P.; Tufano, R.P.; et al. The Role of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hoss, S.; Salla, M.; Khaled, S.; Krayem, M.; Hassan, H.F.; El Khatib, S. Update on Vitamin D Deficiency and Its Impact on Human Health Major Challenges & Technical Approaches of Food Fortification. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, C.; Corinaldesi, C.; Lenzi, A.; Migliaccio, S.; Crescioli, C. Vitamin D as a Shield against Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolando, M.; Barabino, S. Dry Eye Disease: What Is The Role of Vitamin D? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.-M.; Vieira, J.M.; Gonçalves, R.F.S.; Martins, J.T.; Vincente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Development of Novel Functional Thickened Drinks Enriched with Vitamin D3 for the Older Adult Population—Behaviour under Dynamic in Vitro Digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Górska, A.; Brzezińska, R.; Piasecka, I. Assessment of the Nutritional Potential and Resistance to Oxidation of Sea Buckthorn and Rosehip Oils. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.K.; Shukla, S.; Shukla, V.; Singh, S. Sea Buckthorn: A Potential Dietary Supplement with Multifaceted Therapeutic Activities. Intell. Pharm. 2023, 2, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihal, M.; Roychoudhury, S.; Sirotkin, A.V.; Kolesarova, A. Sea Buckthorn, Its Bioactive Constituents, and Mechanism of Action: Potential Application in Female Reproduction. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1244300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y. Bioactive Compounds in Sea Buckthorn and Their Efficacy in Preventing and Treating Metabolic Syndrome. Foods 2023, 12, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čulina, P.; Balbino, S.; Čepo, D.V.; Golub, N.; Garofulić, I.E.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; You, L.; Pedisić, S. Stability of Fatty Acids, Tocopherols, and Carotenoids of Sea Buckthorn Oil Encapsulated by Spray Drying Using Different Carrier Materials. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yan, X.; Zheng, H.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Zhen, Z.; Du, C. The Application of Encapsulation Technology in the Food Industry: Classifications, Recent Advances, and Perspectives. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabot, G.L.; Schaefer Rodrigues, F.F.; Polano Ody, L.L.; Vinίcius Tres, M.; Herrera, E.E.; Palacin, H.H.; Córdova-Ramos, J.S.J.S.; Best, I.; Olivera-Montenegro, L.; Vinícius Tres, M.; et al. Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds for Food and Agricultural Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.; Meghwal, M.; Das, K. Microencapsulation: An Overview on Concepts, Methods, Properties and Applications in Foods. Food Front. 2021, 2, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, M.; Hanula, M.M.; Khachatryan, K.; Khachatryan, G. Nano-/Microcapsules, Liposomes, and Micelles in Polysaccharide Carriers: Applications in Food Technology. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djerri, R.; Merniz, S.; D’Elia, M.; Aissani, N.; Khemili, A.; Abou Mustapha, M.; Rastrelli, L.; Himed, L. Ultrasound-Enhanced Ionotropic Gelation of Pectin for Lemon Essential Oil Encapsulation: Morphological Characterization and Application in Fresh-Cut Apple Preservation. Foods 2025, 14, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberkane, L.; Roudaut, G.; Saurel, R. Encapsulation and Oxidative Stability of PUFA-Rich Oil Microencapsulated by Spray Drying Using Pea Protein and Pectin. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 7, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł, A.; Środa-Pomianek, K.; Górniak, A.; Wikiera, A.; Cyprych, K.; Malik, M. Structural Determination of Pectins by Spectroscopy Methods. Coatings 2022, 12, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkar Gore, D.; Ahmad, F.; Tikoo, K.; Kumar Bansal, A.; Kumar, D.; Pal Singh, I. Comparative Quantitative Analysis of Fruit Oil from {Hippophae Rhamnoides} (Seabuckthorn) by QNMR, FTIR and GC-MS. Chin. Herb. Med. 2023, 15, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topală, C.M.; Ducu, C. Spectroscopic Study of Sea Buckthorn Extracts. Curr. Trends Nat. Sci. 2014, 3, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Kong, L.; Huang, T.; Wei, X.; Tan, L.; Luo, H.; Zhang, H. Encapsulation in Amylose Inclusion Complex Enhances the Stability and Release of Vitamin, D. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Deng, L.; Dai, T.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, M.; Liang, R. Emulsifying and Emulsion Stabilization Mechanism of Pectin from Nicandra Physaloides (Linn.) Gaertn Seeds: Comparison with Apple and Citrus Pectin. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 130, 107674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkempinck, S.H.E.; Kyomugasho, C.; Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Denis, S.; Bourgeois, M.; Van Loey, A.M.; Hendrickx, M.E.; Grauwet, T. Emulsion Stabilizing Properties of Citrus Pectin and Its Interactions with Conventional Emulsifiers in Oil-in-Water Emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 85, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngouémazong, E.D.; Christiaens, S.; Shpigelman, A.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. The Emulsifying and Emulsion-Stabilizing Properties of Pectin: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskovac, M.; Cupara, S.; Kipic, M.; Barjaktarevic, A.; Milovanovic, O.; Kojicic, K.; Markovic, M. Sea Buckthorn Oil—A Valuable Source for Cosmeceuticals. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Theoretical Prediction of Emulsion Color. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 97, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Thakur, N.; Kajla, P.; Thakur, S.; Punia, S. Application of Encapsulation Technology in Edible Films: Carrier of Bioactive Compounds. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 734921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyspiańska, D.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Kolniak-Ostek, J. Effect of Microencapsulation on Concentration of Isoflavones during Simulated in Vitro Digestion of Isotonic Drink. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, Z.; Chen, J. Lubrication and Sensory Properties of Emulsion Systems and Effects of Droplet Size Distribution. Foods 2021, 10, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystyjan, M.; Gumul, D.; Ziobro, R.; Sikora, M. The Effect of Inulin as a Fat Replacement on Dough and Biscuit Properties. J. Food Qual. 2015, 38, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, M.E.; Appelqvist, I.A.M.; Norton, I.T. Oral Behaviour of Food Hydrocolloids and Emulsions. Part 1. Lubrication and Deposition Considerations. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yiu, C.C.Y.; Kim, W.; Vongsvivut, J.; Zhou, W.; Selomulya, C. Emulsion Gels of Oil Encapsulated in Double Polysaccharide Networks as Animal Fat Analogues. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 171, 111807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverrier, C.; Almeida, G.; Cuvelier, G.; Menut, P. Modelling Shear Viscosity of Soft Plant Cell Suspensions. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 118, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Sun, Y.; Tan, C. Recent Advances in Emerging Pectin-Derived Nanocarriers for Controlled Delivery of Bioactive Compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 140, 108682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potdar, S.B.; Landge, V.K.; Barkade, S.S.; Potoroko, I.; Sonawane, S.H. Flavor Encapsulation and Release Studies in Food. Encapsulation Act. Mol. Their Deliv. Syst. 2020, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiwei, D.; Linhui, Z.; Minghui, L.; Fei, L.; Jianhua, L.; Yuting, D. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Encapsulation System: Physical and Oxidative Stability, and Medical Applications. Food Front. 2022, 3, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8587:2006; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Ranking. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Krystyjan, M.; Khachatryan, G.; Grabacka, M.; Krzan, M.; Witczak, M.; Grzyb, J.; Woszczak, Ł.; Woszczak, L. Physicochemical, Bacteriostatic, and Biological Properties of Starch/Chitosan Polymer Composites Modified by Graphene Oxide, Designed as New Bionanomaterials. Polymers 2021, 13, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.J. Colour Measurement and Analysis in Fresh and Processed Foods: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 6, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, V.; Gurak, P.D.; Ferreira Marczak, L.D.; Tessaro, I.C. Tracking Bioactive Compounds with Colour Changes in Foods —A Review. Dye. Pigment. 2013, 98, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3972:2011; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Method of Investigating Sensitivity of Taste. ISO: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; Voloume 2016.

- ISO 5492:2008; Sensory Analysis—Vocabulary. ISO: Warsaw, Poland, 2008.

- ISO 8586:2023; Sensory Analysis—Selection and Training of Sensory Assessors. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 11132:2021; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Guidelines for the Measurement of the Performance of a Quantitative Descriptive Sensory Panel. ISO: Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- ISO 13299:2016; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance for Establishing a Sensory Profile. ISO: Warsaw, Poland, 2016.

- ISO 6658:2017; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 8589:2007; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Design of Test Rooms. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 11036:2020; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Texture Profile. ISO: Warsaw, Poland, 2020.

| Sample | L* (D65) | a* (D65) | b* (D65) | C* | h* (rad) | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | 35.01 ± 0.04 a | 12.32 ± 0.06 c | 12.12 ± 0.04 c | 17.29 ± 0.05 c | 0.78 ± 0.00 c | |

| D1 | 38.23 ± 0.01 b | 13.89 ± 0.03 b | 17.06 ± 0.03 b | 22.00 ± 0.04 b | 0.89 ± 0.00 a | 6.07 ± 0.03 |

| D2 | 41.29 ± 0.03 c | 18.68 ± 0.01 a | 18.85 ± 0.03 a | 26.54 ± 0.03 a | 0.79 ± 0.00 b | 11.16 ± 0.03 |

| Sample | Texture Parameters | |

|---|---|---|

| Hardness [N] | Adhesiveness [N·s] | |

| K | 0.25 ± 0.01 a | 0.19 ± 0.03 a |

| D1 | 0.21 ± 0.00 c | 0.06 ± 0.00 b |

| D2 | 0.22 ± 0.00 b | 0.08 ± 0.00 b |

| Product | Sum of Ranks |

|---|---|

| K | 24 a |

| D1 | 21 a |

| D2 | 21 a |

| Sample Designation | Mousse Variant Description |

|---|---|

| Control (K) | Traditional apple–plum mousse |

| Fortified 1 (D1) | Apple–plum mousse enriched with vitamin D3 and sea buckthorn oil via encapsulation |

| Fortified 2 (D2) | Apple–plum mousse enriched with vitamin D3 and sea buckthorn oil via direct addition |

| Attribute | Feature |

|---|---|

| External Appearance | Presence/Absence of: syneresis (water leakage), ingredient separation, visible oil droplets; surface shine/gloss. Colour |

| Consistency | Homogeneity of consistency (visually), homogeneity of consistency (in the mouth), density |

| Smell (Odour) | apple, plum, foreign |

| Taste | Sweet, sour, bitter, apple, plum, oily, and foreign taste. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krystyjan, M.; Majka, P.; Sobolewska-Zielińska, J.; Turek, K.; Michalski, O.; Khachatryan, K.; Khachatryan, G. Enrichment of Apple–Plum Fruit Mousse with Vitamin D3 and Sea Buckthorn Oil Using Pectin-Based Encapsulation: A Study of Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311480

Krystyjan M, Majka P, Sobolewska-Zielińska J, Turek K, Michalski O, Khachatryan K, Khachatryan G. Enrichment of Apple–Plum Fruit Mousse with Vitamin D3 and Sea Buckthorn Oil Using Pectin-Based Encapsulation: A Study of Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311480

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrystyjan, Magdalena, Patrycja Majka, Joanna Sobolewska-Zielińska, Katarzyna Turek, Oskar Michalski, Karen Khachatryan, and Gohar Khachatryan. 2025. "Enrichment of Apple–Plum Fruit Mousse with Vitamin D3 and Sea Buckthorn Oil Using Pectin-Based Encapsulation: A Study of Physicochemical and Sensory Properties" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311480

APA StyleKrystyjan, M., Majka, P., Sobolewska-Zielińska, J., Turek, K., Michalski, O., Khachatryan, K., & Khachatryan, G. (2025). Enrichment of Apple–Plum Fruit Mousse with Vitamin D3 and Sea Buckthorn Oil Using Pectin-Based Encapsulation: A Study of Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311480