Beta-Arrestin 1 Deficiency Enhances Host Anti-Myeloma Immunity Through T Cell Activation and Checkpoint Modulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

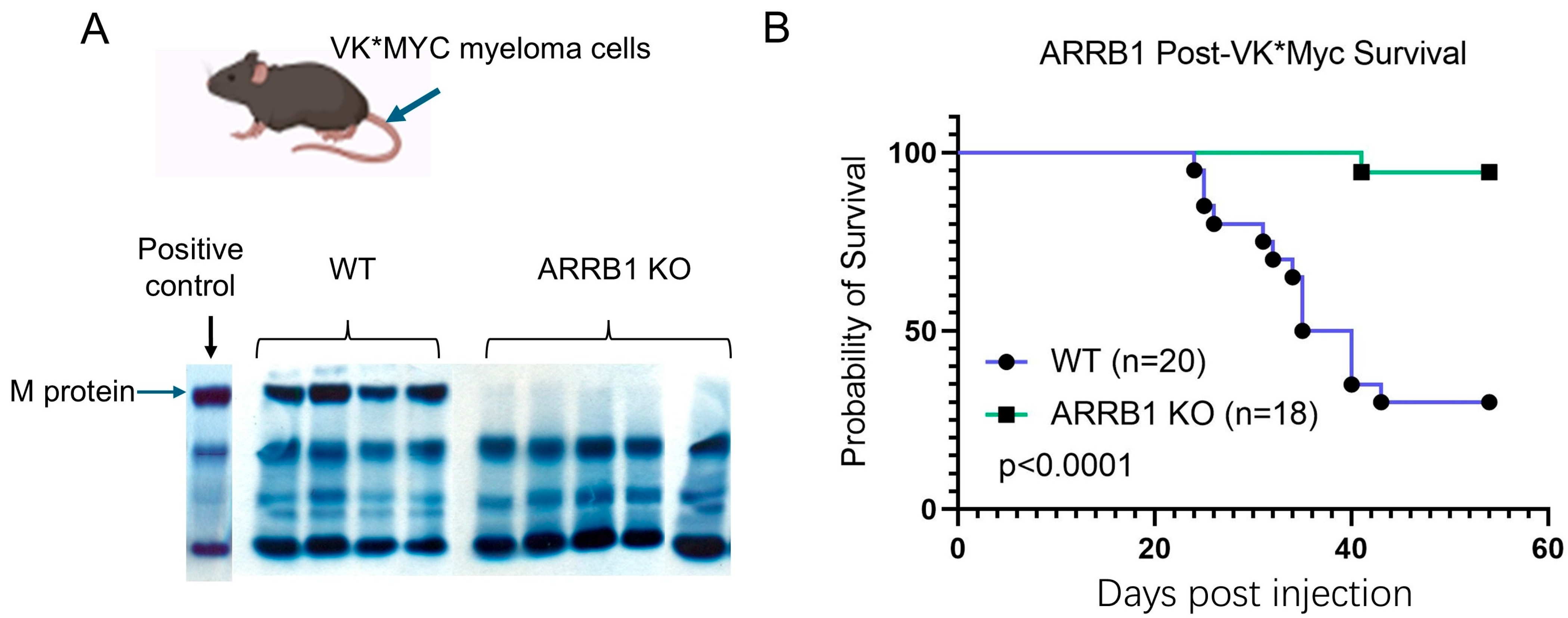

2.1. Host ARRB1 Deficiency Resists Tumor Development and Confers Survival Advantage in Murine Myeloma

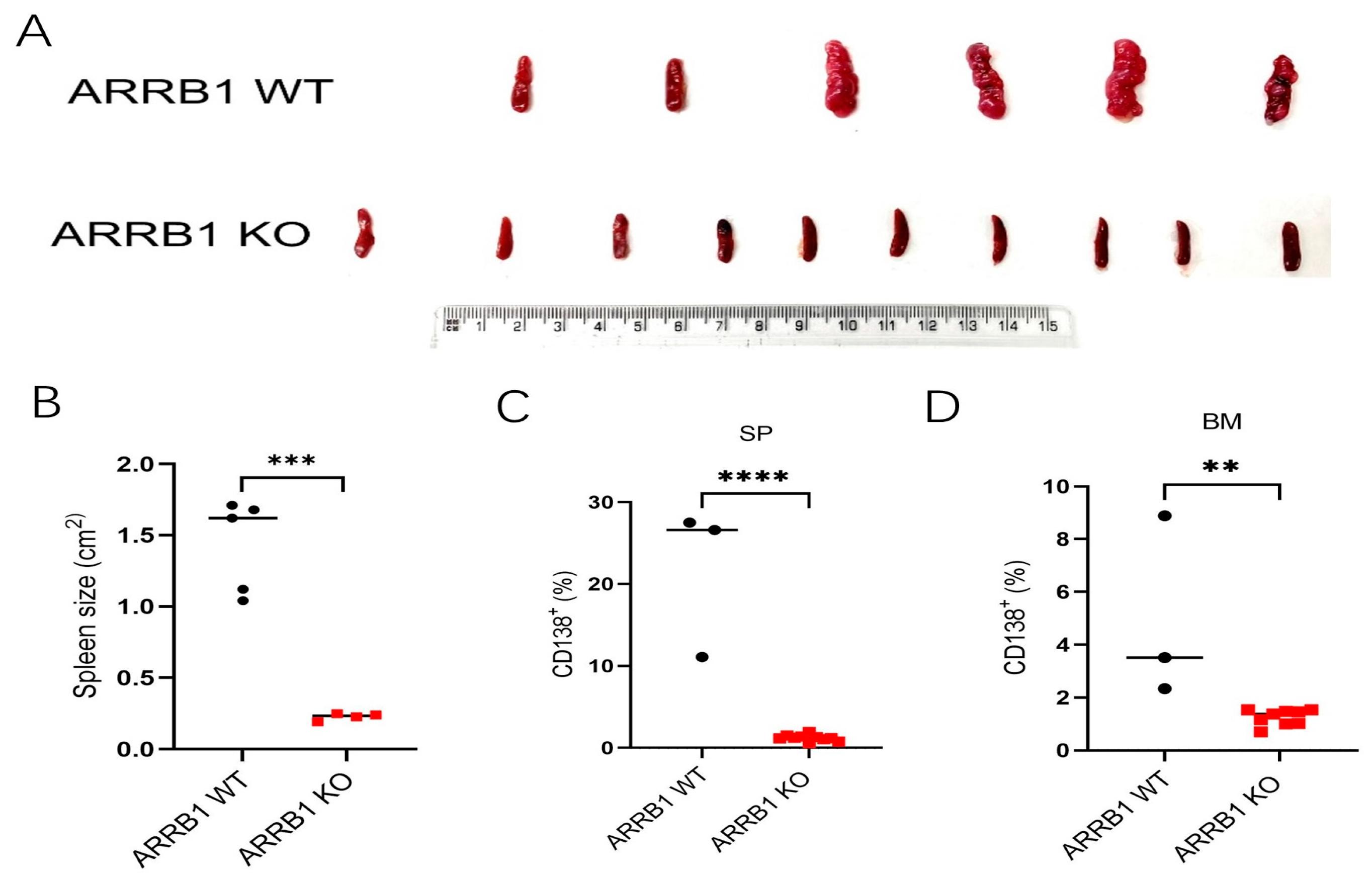

2.2. ARRB1 Deficiency Prevents Splenic Myeloma Tumor Infiltration

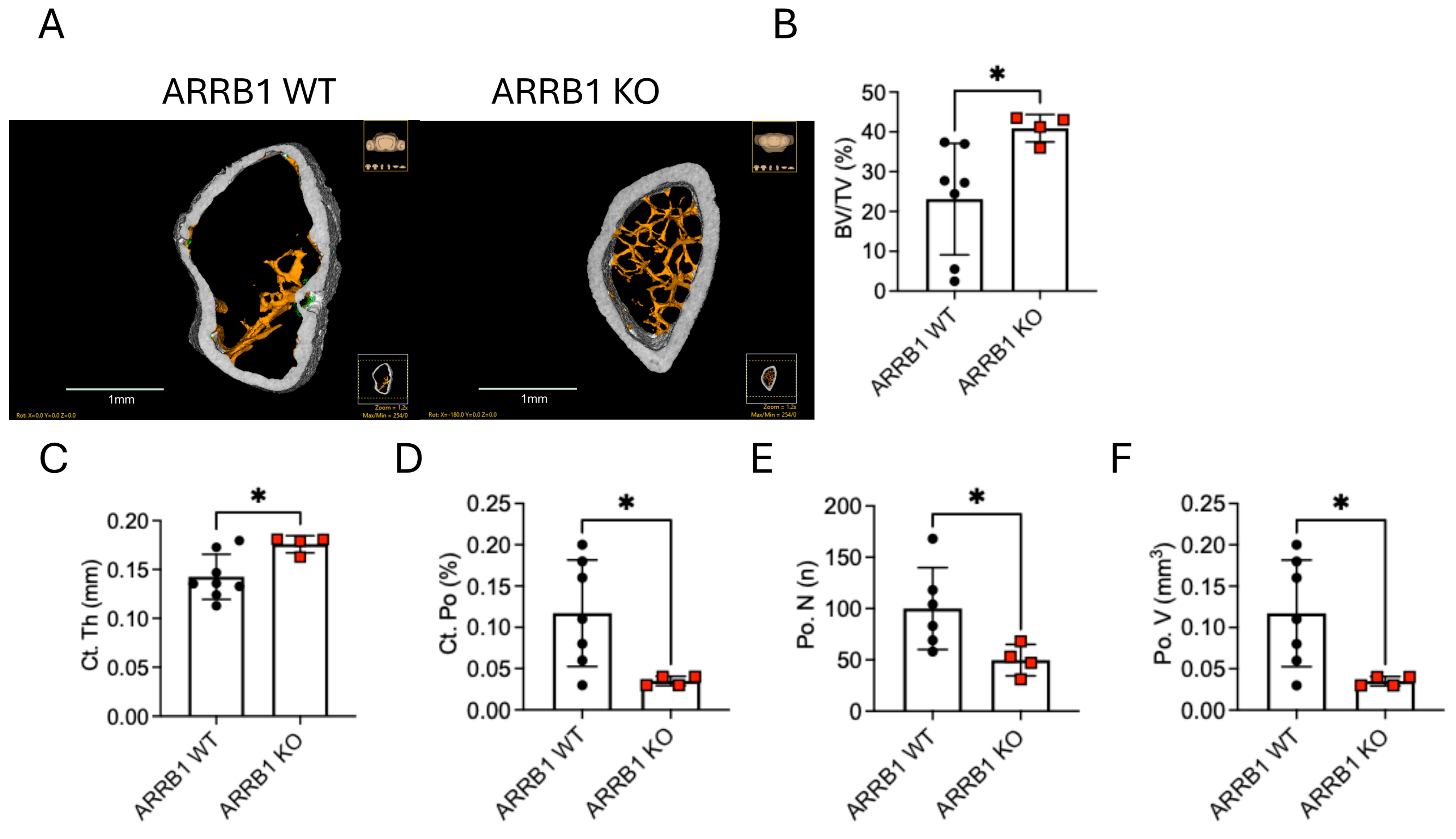

2.3. ARRB1 Deficiency Protects Against Myeloma-Induced Bone Disease

2.4. Host ARRB1 Deficiency Promotes Anti-Tumor T Cell Responses

2.5. ARRB1 Regulates PD-1 Expression on Immune Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice and Animal Care

4.2. Vk*MYC Myeloma Cells

4.3. Myeloma Model and Survival Analysis

4.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

4.5. Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro CT) Analysis

4.6. Serum Protein Electrophoresis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

| ARRB1 | Beta-arrestin 1 |

| GPCRs | G-protein-coupled receptors |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein-1 |

| MDSC | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| TCR | T cell receptor |

| SPEP | Serum protein electrophoresis |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| BV/TV | Bone volume/total volume |

References

- Pawlyn, C.; Morgan, G.J. Evolutionary biology of high-risk multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Smyth, M.J.; Martinet, L. Cancer immunoediting and immune dysregulation in multiple myeloma. Blood 2020, 136, 2731–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; Rajkumar, V.; Kyle, R.A.; van Duin, M.; Sonneveld, P.; Mateos, M.V.; Gay, F.; Anderson, K.C. Multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Zhao, Y.; Loitsch, G.; Feinberg, D.; Mathews, P.; Barak, I.; Dupuis, M.; Li, Z.; Rein, L.; Wang, E.; et al. The impact of bone marrow fibrosis and JAK2 expression on clinical outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated with immunomodulatory agents and/or proteasome inhibitors. Cancer Med. 2022, 9, 5869–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Moschetta, M.; Manier, S.; Glavey, S.; Görgün, G.T.; Roccaro, A.M.; Anderson, K.C.; Ghobrial, I.M. Targeting the bone marrow microenvironment in multiple myeloma. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 263, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, P.; Berardi, S.; Frassanito, M.A.; Ria, R.; De Re, V.; Cicco, S.; Battaglia, S.; Ditonno, P.; Dammacco, F.; Vacca, A.; et al. Dendritic cells accumulate in the bone marrow of myeloma patients where they protect tumor plasma cells from CD8+ T-cell killing. Blood 2015, 126, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görgün, G.T.; Whitehill, G.; Anderson, J.L.; Hideshima, T.; Maguire, C.; Laubach, J.; Raje, N.; Munshi, N.C.; Richardson, P.G.; Anderson, K.C. Tumor-promoting immune-suppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the multiple myeloma microenvironment in humans. Blood 2013, 121, 2975–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannotta, C.; Autino, F.; Massaia, M. The immune suppressive tumor microenvironment in multiple myeloma: The contribution of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1102471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chang, X. What happens to regulatory T cells in multiple myeloma. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.T.; Cho, S.F.; Anderson, K.C. Osteoclast Immunosuppressive Effects in Multiple Myeloma: Role of Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, X.; Bossers, K.; Swaab, D.F.; Zhao, J.; Pei, G. β-arrestin1 regulates γ-secretase complex assembly and modulates amyloid-β pathology. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Appleton, K.M.; Strungs, E.G.; Kwon, J.Y.; Morinelli, T.A.; Peterson, Y.K.; Laporte, S.A.; Luttrell, L.M. The conformational signature of β-arrestin2 predicts its trafficking and signalling functions. Nature 2016, 531, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Y.K.; Luttrell, L.M. The Diverse Roles of Arrestin Scaffolds in G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017, 69, 256–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Lei, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Xu, C.; Wu, B. ARRB1 downregulates acetaminophen-induced hepatoxicity through binding to p-eIF2alpha to inhibit ER stress signaling. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2024, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWire, S.M.; Ahn, S.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Shenoy, S.K. β-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2007, 69, 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arenas, E.; Calleja, E.; Martínez-Martín, N.; Gharbi, S.I.; Navajas, R.; García-Medel, N.; Penela, P.; Alcamí, A.; Mayor, F., Jr.; Albar, J.P.; et al. β-Arrestin-1 mediates the TCR-triggered re-routing of distal receptors to the immunological synapse by a PKC-mediated mechanism. Embo J. 2014, 33, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Cook, J.A.; Gilkeson, G.S.; Luttrell, L.M.; Wang, L.; Borg, K.T.; Halushka, P.V.; Fan, H. Increased expression of beta-arrestin 1 and 2 in murine models of rheumatoid arthritis: Isoform specific regulation of inflammation. Mol. Immunol. 2011, 49, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Malik, A.; Lee, E.; Britton, R.A.; Parameswaran, N. Gene dosage-dependent negative regulatory role of β-arrestin-2 in polymicrobial infection-induced inflammation. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3035–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, P.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Jabbar, S.; Burcher, K.; Rein, L.; Kang, Y. β-Arrestin 2 as a Prognostic Indicator and Immunomodulatory Factor in Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2025, 14, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Sha, Y.; Roof, L.; Foreman, O.; Lazarchick, J.; Venkta, J.K.; Kozlowski, C.; Gasparetto, C.; Chao, N.; Ebens, A.; et al. Pan-PIM kinase inhibitors enhance Lenalidomide’s anti-myeloma activity via cereblon-IKZF1/3 cascade. Cancer Lett. 2019, 440–441, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chesi, M.; Robbiani, D.F.; Sebag, M.; Chng, W.J.; Affer, M.; Tiedemann, R.; Valdez, R.; Palmer, S.E.; Haas, S.S.; Stewart, A.K.; et al. AID-dependent activation of a MYC transgene induces multiple myeloma in a conditional mouse model of post-germinal center malignancies. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.E.; Gherardin, N.A.; Harrison, S.J.; Quach, H.; Godfrey, D.I.; Prince, M.; Koldej, R.; Ritchie, D.S. Spontaneous onset and transplant models of the Vk*MYC mouse show immunological sequelae comparable to human multiple myeloma. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, N.; Bataille, R.; Mancini, C.; Lazzaretti, M.; Barillé, S. Myeloma cells induce imbalance in the osteoprotegerin/osteoprotegerin ligand system in the human bone marrow environment. Blood 2001, 98, 3527–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, I.R.; Condamine, T.; Lin, C.; Herlihy, S.E.; Garfall, A.; Vogl, D.T.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Nefedova, Y. Bone marrow PMN-MDSCs and neutrophils are functionally similar in protection of multiple myeloma from chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2016, 371, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadpour, H.; MacDonald, C.R.; McCarthy, P.L.; Abrams, S.I.; Repasky, E.A. β2-adrenergic receptor signaling regulates metabolic pathways critical to myeloid-derived suppressor cell function within the, T.M.E. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblatt, J.; Avigan, D. Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in multiple myeloma: A dream or a reality? Blood 2017, 129, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W.; Lam, W.Y.; Chen, F.; Yung, M.M.H.; Chan, Y.S.; Chan, W.S.; He, F.; Liu, S.S.; Chan, K.K.L.; Li, B.; et al. Genome-wide DNA methylome analysis identifies methylation signatures associated with survival and drug resistance of ovarian cancers. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Lei, Y.; Zhou, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, B. β-Arrestin1 is involved in hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis via extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 2229–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, F.; Jia, D.; Bi, S.; Gong, J.; Wu, J.J.; Mao, Y.; Chen, J.; Chai, G.S. Pathological features and molecular signatures of early olfactory dysfunction in 3xTg-AD model mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, S.R.; Karimi, M.; Mahdavi, B.; Yousefi Tehrani, M.; Bemani, A.; Kabirian, S.; Mohammadi, J.; Jabbari, S.; Hushmand, M.; Mokhtar, A.; et al. Crosstalk between non-coding RNAs and programmed cell death in colorectal cancer: Implications for targeted therapy. Epigenet. Chromatin 2025, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, W.; Niu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, C. Lysyl oxidase promotes renal fibrosis via accelerating collagen cross-link driving by β-arrestin/ERK/STAT3 pathway. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, C.; Bellaci, J.; Spiegel, S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in vascular endothelial and lymphatic barrier function. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Pathogenesis of bone disease in multiple myeloma: From bench to bedside. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierroz, D.D.; Bonnet, N.; Baldock, P.A.; Ominsky, M.S.; Stolina, M.; Kostenuik, P.J.; Ferrari, S.L. Are osteoclasts needed for the bone anabolic response to parathyroid hormone? A study of intermittent parathyroid hormone with denosumab or alendronate in knock-in mice expressing humanized RANKL. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 28164–28173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahsai, A.W.; Pakharukova, N.; Kwon, H.Y.; Shah, K.S.; Liang-Lin, J.G.; del Real, C.T.; Shim, P.J.; Lee, M.A.; Ngo, V.A.; Shreiber, B.N.; et al. Small-molecule modulation of β-arrestins. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, K.; Honda, K.; Kondoh, Y.; Osada, H.; Watanabe, N. Identification of a small-molecule ligand of β-arrestin1 as an inhibitor of stromal fibroblast cell migration accelerated by cancer cells. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, D.A.; Mathier, M.A.; Mortensen, R.M.; Christe, M.; Vatner, S.F.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G. β-Arrestin1 knockout mice appear normal but demonstrate altered cardiac responses to β-adrenergic stimulation. Circ. Res. 1997, 81, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Yesupatham, S.K.; Allison, D.; Tanwar, H.; Gnanasekaran, J.; Kear, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zachariadou, C.; Abbasi, Y.; et al. Murine IRF8 Mutation Offers New Insight into Osteoclast and Root Resorption. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Jabbar, S.; Ganesh, N.; Chu, E.; Math, V.T.; Rein, L.; Kang, Y. Beta-Arrestin 1 Deficiency Enhances Host Anti-Myeloma Immunity Through T Cell Activation and Checkpoint Modulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311478

Wu J, Wang X, Jabbar S, Ganesh N, Chu E, Math VT, Rein L, Kang Y. Beta-Arrestin 1 Deficiency Enhances Host Anti-Myeloma Immunity Through T Cell Activation and Checkpoint Modulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311478

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jian, Xiaobei Wang, Shaima Jabbar, Niyant Ganesh, Emily Chu, Vivek Thumbigere Math, Lindsay Rein, and Yubin Kang. 2025. "Beta-Arrestin 1 Deficiency Enhances Host Anti-Myeloma Immunity Through T Cell Activation and Checkpoint Modulation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311478

APA StyleWu, J., Wang, X., Jabbar, S., Ganesh, N., Chu, E., Math, V. T., Rein, L., & Kang, Y. (2025). Beta-Arrestin 1 Deficiency Enhances Host Anti-Myeloma Immunity Through T Cell Activation and Checkpoint Modulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311478