Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have the potential for novel treatments of several musculoskeletal conditions due to their ability to differentiate into several cell lineages including chondrocytes, adipocytes and osteocytes. Researchers are exploring whether this could be utilized for novel therapies for joint afflictions. The role of gender in the ability of MSCs to differentiate and proliferate into different cells has not been clearly defined. This systematic review aims to report the current literature on studies, characterized by high quality and in-depth analysis even though quantitatively limited, that have looked at the role of gender in the differentiation and proliferation of MSCs. Sixteen studies were identified during the literature search, reporting 533 patients, of which 202 were male and 331 were female. MSC proliferation, phenotypic analysis and differentiation are reported and contrasted in terms of donor gender. Heterogeneity in methodologies across studies likely contributes to the inconclusive findings presented here, with no discernible statistical disparity observed between genders in differentiation traits. Nevertheless, the proliferation results indicate a notable gender-related impact. Future investigations should aim to ascertain the potential influence of gender on MSC proliferation capacities more conclusively, emphasizing the necessity of standardized protocols for MSC analyses to enhance accuracy and comparability across studies.

1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) demonstrate promising and novel pathways in many musculoskeletal (MSK) diseases and injury states and have been the source of active research. Degenerative diseases and trauma to joints have focused on lifestyle changes and pharmacological and surgical options to treat these particular conditions [1,2]. MSCs provide a novel pathway in cellular differentiation and healing that has allowed researchers to interrogate and assess if they work in particular MSK disease states [3,4].

MSCs have the potential to differentiate into different mesoderm-derived specialized cells, which include osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes and tenocytes, and therefore, its potential multicellular properties allow it to potentially change the course of the disease state in question [5,6]. Osteoarthritis occurs as a disease or injury with poor healing and changes in the joint’s architecture, including ligamentous and tendinous injuries [7,8]. With osteoarthritis, the predominant issue is one of cartilaginous loss with time or as a result of prior trauma to the joint. It is thought that MSCs may also function using immunomodulation, whereby they influence the reparative process within a joint [9]. With osteoarthritis, this works by activating chondrocyte differentiation with the potential to lay down new cartilage. Previous research has demonstrated that MSCs are capable of generating the primary components of articular cartilage: (1) proteoglycans, which impart compressive stiffness to the cartilage, and (2) type II collagen, which enhances the cartilage’s tensile strength and resilience [10].

During soft tissue injury of joints, particularly with ligaments and tendons, the healing process remains long [11]. This is partly a result of the poor vasculature in these areas; therefore, patients are immobilized for several months to allow the body to heal these structures. Studies show that these areas, although able to heal, do not always appear to have the same tensile strength as an uninjured tendon/ligament and therefore are at higher risk of re-rupture [12]. MSCs have the potential to both speed up this healing process but also allow stronger healing of these regions through actions that may include immunomodulation of cells during the active phase of the injury, angiogenesis within the region and the differentiation of tenocytes to allow the appropriate extracellular matrix and cell deposition to restore the tensile strength of these regions [13,14].

Many of the studies in the literature have shown MSC potential in vitro, but not all studies have looked at this in vivo. In particular, it is unclear whether gender plays a role in the ability of MSCs to differentiate appropriately within these injury or disease states or whether gender and MSC use differently influence the homeostatic and reparative mechanisms associated with reported immunomodulation that occurs with the use of MSCs [15]. Women, for example, are more likely to develop osteoarthritis following menopause where there is an accelerated state of bone metabolism as a result of the loss of estrogen in normal bone homeostasis [16,17,18,19,20]. Whether this endocrine function influences the MSC state within the joint remains to be seen and is something that remains unknown in the literature.

Aim

This systematic review aimed to identify and report on whether the gender of a patient affected the proliferation and differentiation capacity within mesenchymal stromal cells. The primary goal was to report from the available literature and studies to date as to whether gender influences this capacity and to amalgamate this together.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

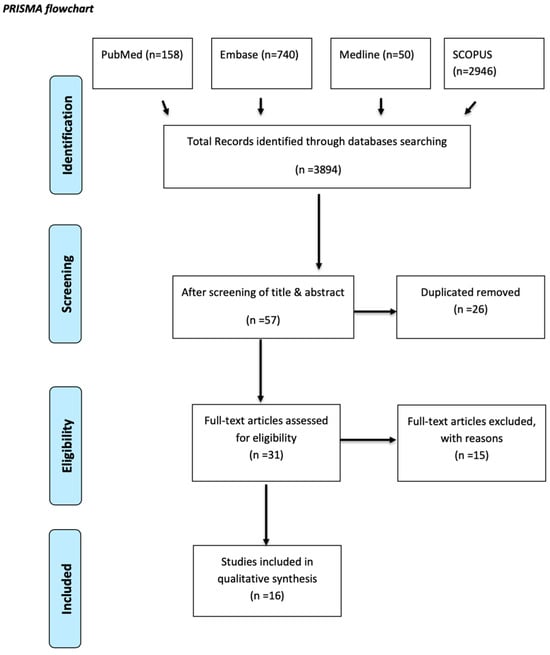

A systematic review of the literature was conducted following the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) [21,22]. The literature search spanned four major databases: PubMed, Embase, Medline, and SCOPUS. Searches were executed during the last week of October and the first week of November. The strategy employed specific search terms, as detailed below: “sex” or “gender” and “mesenchymal stem cells” or “mesenchymal stem cell” or” mesenchymal stromal cells” or “mesenchymal stromal cell” and “cell surface characterisation” or “cell surface” or “differentiation potential” or “differentiation” and “in vitro”.

One hundred and fifty-eight studies were extracted from PubMed (1946—last week of August 2024), 740 from Embase (1996—last week of August 2024), 50 from Medline (1946—first week of August 2024), and 2946 from SCOPUS (1900—last week of August 2024). In total, 3894 papers were identified. After careful screening of titles and abstracts, we narrowed down our selection to 57 papers. A total of 26 duplicate papers were identified and excluded from the analysis. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the remaining studies were screened based on their titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 31 studies were reviewed in full but excluded according to the exclusion criteria outlined below. This process, detailed in Figure 1, resulted in the identification of 16 papers for data extraction. The search was carried out by (AV, AF, and JK), with two authors (WK and AV) independently reviewing the titles and abstracts. Disagreements were resolved by including the studies for a full-text review.

The study was registered on the PROSPERO database with the registration number (247882), and the protocol can be accessed at the following web address.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- In vitro studies involving adult human subjects;

- Studies with a reference to subjects’ gender/sex;

- Studies looking at MSCs and with source of extraction of cells specified;

- Studies that investigated at least one lineage of differentiation or MSC characterization;

- English language.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Duplicate studies;

- Those not in the English language;

- All non-human in vitro or in vivo studies;

- Studies using samples from patients with multisystem diseases and malignancies;

- Any paper other than research papers was excluded;

- Studies looking at non-mesenchymal cells, e.g., embryonic, umbilical cord and periodontal MSCs.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted and organized using an Excel spreadsheet for systematic analysis. The extracted information is summarized in four tables, which include the reference details, a concise description of the study, the number and gender of patient donors, the source of the MSCs, culture conditions, proliferation data, MSC surface markers characterization, and results from chondrogenic, adipogenic, and osteogenic differentiation analyses.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The quality of each included study was evaluated using a modified version of the “OHAT Risk of Bias Rating Tool for Human and Animal Studies” developed by the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) [23]. Any discrepancies in the quality assessment results were resolved through discussion and consensus among the authors.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram [21]. n = number of records.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Included Studies

This systematic review included a total of 16 studies, as illustrated in Figure 1. The studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria ranged from the earliest, published in 2008 [24], to the most recent, published in 2023 [25]. In the majority of the included studies, MSCs were extracted from various tissues of both healthy individuals and osteoarthritic patients, and the proliferation of different MSC types was assessed.

All studies included investigated the gender effect on adult MSCs derived from different sources of the human body; however, non-MSCs like embryonic, umbilical cord and periodontal stem cells were excluded. Periodontal cells were not included in this systematic review due to their distinct developmental origin and functional properties compared to other MSCs. Firstly, periodontal stem cells exhibit unique developmental origins compared to other MSCs, being derived from the ectoderm rather than the mesoderm like most MSCs found below the neck. This difference in embryonic origin suggests that periodontal cells may possess distinct developmental memory and functional characteristics, potentially leading to different responses to gender-related factors. Secondly, the focus of the systematic review was likely on MSCs derived from tissues with similar developmental origins to ensure a more homogeneous analysis of gender effects. Thirdly, the specific differentiation pathways and functional properties of periodontal cells, which are primarily involved in the formation of periodontal ligaments and alveolar bone, may not align with the broader scope of the review, which likely centered on the regenerative potential and therapeutic applications of MSCs. Therefore, to maintain consistency and relevance in the analysis of gender effects on mesenchymal stromal cells, periodontal cells were likely excluded from the review.

Sixteen papers were identified following a literature search with the aforementioned search criteria outlined in the methodology (Table 1). Of these, several studies looked at either chondrogenic or osteogenic potential in different sex groups. A total of seven papers looked at chondrocyte differentiation capacity between age groups, nine investigated the impact of sex on osteogenic potential, and five papers looked at adipogenic differentiation variability between the sexes. Three papers focused purely on human muscle progenitor cells and one paper looked at perivascular differentiation. The donor sites of these cells varied in each of the studies with a predilection to knee and synovial tissue to extract MSCs and the analysis of these cell characteristics was performed ex vivo. A total number of 533 patients (range 6–131 patients) were recruited into the 15 studies with a gender distribution of 202 males to 331 females (ratio 1:1.6, M:F). One study did not report the total number of patients or sex ratio [26].

Table 1.

General characteristics of the studies.

Each of these studies used slight variations and differing methodologies to isolate and positively identify cells through a culmination of immunohistochemistry, genetic analysis and biochemical studies. These are reported in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Proliferation and MSC characterization.

Table 3.

Chondrogenic and Osteogenic Differentiation.

Table 4.

Adipogenic differentiation and other results.

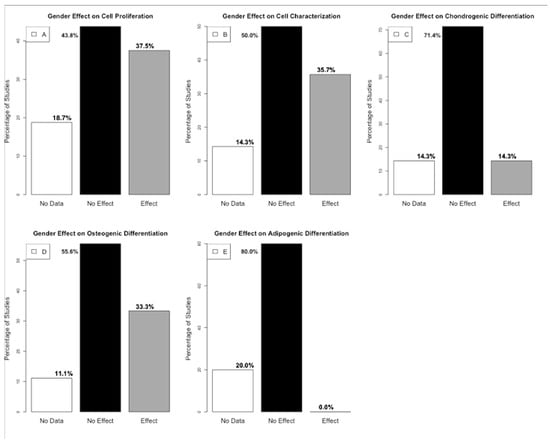

3.2. Gender Effect

A summary of the presence or absence of gender-related effects on cell proliferation, characterization, and differentiation, based on statistical outcomes was analyzed (Figure 2). The boundary distinguishing between “effect” and “no effect” was established through observations conducted over the same period, specifically evaluating differences between genders. Key parameters assessed included gene expression and cell count, among others.

Figure 2.

(A). Histogram presenting the percentage distribution of gender effect out of the 16 studies on cell proliferation. (B). Histogram presenting the percentage distribution of gender effect out of the 14 studies on cell characterization (C). Histogram presenting the percentage distribution of gender effect out of the seven studies on chondrogenic differentiation. (D). Histogram presenting the percentage distribution of gender effect out of the nine studies on osteogenic differentiation. (E). Histogram presenting the percentage distribution of gender effect out of the five studies on adipogenic differentiation (generated by R version 4.4.0).

3.3. Proliferation Analysis

Proliferation analysis between the different studies used a combination of immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, genetic analysis and biochemical assays as well as micro-CT to report the difference in population numbers between the sexes. In summary, all 16 studies followed a proliferation protocol; however, only 13 presented data on the effect of gender on cell proliferation. Six studies found a gender effect on cell proliferation. One study showed a statistically significant increase in MSC proliferation from male donors compared to females [25]. Five studies showed a statistical difference with an increase in proliferation from female donors in comparison to male donors. Seven studies showed no statistical differences in proliferation rates between the genders [1,7,33,34,36,37,38]. Three studies failed to report the differences in proliferation rates [24,26,35]. This heterogeneity may be explained due to the variation in study methodology and characterization of cells and no clear uniformity in study protocols yielded variable results.

3.4. MSCs Characterization

Out of 16 studies, 14 conducted cell characterization. However, two studies did not mention how they characterized the cells [24,25]. One of these studies mentioned that the cells were commercially purchased, indicating that characterization was likely performed by the industry [25]. Two studies mentioned that they characterized the cells, but did not present any results in correlation to gender [26,38]. Seven studies did not find a correlation between gender and cell characterization [1,27,33,34,35,36,37]. High variability in MSC characterization as a result of variations in methodology was noted between the different studies. The most common implementation was flow cytometry with immunologically labeled antibodies. All studies adhered to ISCT guidelines for MSC characterization, utilizing CD90, CD73, and CD105 as positive markers, while CD45, CD31, CD34, and HLA-DR were used to exclude hematopoietic and endothelial cells. Some studies also examined CD36 as an opposite marker. Additionally, human MSCs were confirmed to express CD44 and CD166 by some of the studies [26,27,28,29,35,36].

Additionally, some studies used flowcytometry as part of the differentiation experiment to identify chondrogenic, adipogenic or chondrogenic cells (positive labeling) and markers of other cellular types (i.e., lipogenic, vascular and other unwanted cells) which were identified and removed from the analysis of data (negative labeling).

3.5. Chondrogenic Differentiation

Of the 16 studies identified in this literature review, seven studies specifically looked at the ability of MSCs to differentiate to the chondrogenic lineage and compared this between both males and females (Table 3) [1,27,29,34,35,36]. Although the study protocols remained heterogenous throughout with varying methods that were used to identify chondrogenic cell lineage, five of these studies did not demonstrate any statistical difference between the two sexes. One study utilized a commercial chondrogenesis differentiation kit and confirmed trilineage differentiation using Safranin O staining; however, the analysis of sex differences in chondrogenic differentiation was not presented [34]. On the other hand, Scibetta et al. (2019) found that male human muscle-derived stem cells (hMDSCs) displayed superior chondrogenesis compared to female MDSCs. While the analysis of chondrogenic markers such as Sox-9 and BMPR2 showed no detectable differences in gene expression between male and female cells, Alcian Blue staining revealed that male cells formed more robust cartilage matrices compared to female cells. Quantitative analysis confirmed a significantly higher matrix content in male hMDSC pellets for specific sample pairs. Additionally, immunohistochemistry demonstrated more intense Col2A1 staining in male hMDSC populations than in their female counterparts [35]. One study did not find differences based on sex for chondrogenic differentiation but noted that any observed variations were likely attributable to age [26]. Of the seven studies, both Scibetta et al. (2019) and Hermann et al. (2019) were the most robust of the studies as they used three different methodologies to characterize their chondrocyte-differentiated MSCs.

3.6. Osteοgenic Differentiation and Adipogenic Differentiation

Osteogenic differentiation was investigated in 9 of the 16 studies which reported findings (Table 4). Of the nine, five studies did not show a statistically significant difference between both male and female donors. Additionally, one study indicated a correlation between osteogenic differentiation and TNAP [1] while another study found a correlation between the site of MSCs and osteogenic differentiation [33]. One study did not analyze the difference between gender and osteogenic differentiation despite identifying these cells [34]. Three studies, however, do demonstrate a statistical significance in male donor osteogenic cells exhibiting an increased rate of proliferation and density of mineralization. Aksu et al. (2008) [24] presented gender differences in osteogenic differentiation. It started within a week, marked by vertical growth, lacunae formation, increased matrix volume, and mineralization. Notably, males exhibited faster and more efficient differentiation, particularly in the superficial depot, compared to females. Male AMSCs from both depots showed superior osteogenic potential, with those from the male superficial layer demonstrating the highest efficiency. Scibetta et al. (2019) demonstrated male human muscle-derived stem cells (hMDSCs) exhibited a greater capacity for osteogenesis compared to female MDSCs [35]. Kolliopoulos et al. (2023) revealed significant sex-based differences in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). MSCs from females exhibited a notably higher osteogenic response, including increased alkaline phosphatase activity, osteoprotegerin release, and mineral formation in vitro. Specifically, the study reported that female MSCs exhibited higher alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity increased mineral deposition and elevated the secretion of SPARC, an osteogenic factor, compared to male MSCs [25]. In these studies, the authors show the superior density of matrix mineralization compared to female donors but do not appear to explain the reasons behind this.

Adipogenic differentiation was reported in five studies. Four did not demonstrate a difference between the sexes (Table 4). One study [34] did not analyze any differences between sexes despite identifying and characterizing adipogenic cells from MSCs.

3.7. Other Cell Differentiation Analyses

Two papers looked at the cells from muscle precursor cells: [31,32]. Of these, Riddle et al. (2018) were unable to show a statistical significance between the two groups [32]. Stolting et al. (2017) were able to show decreased sarcomeric protein expression in male donors and increased precursor-like characteristics compared to female donors [31]. One study looked at perivascular mesenchymal stem cells and demonstrated no significant differences in proliferation between the sexes [30]. In another study, researchers investigated the differentiation of angiogenic factors and the expression of genes involved in immunomodulation. Notably, they observed that angiogenic gene expression showed higher fold changes in male cells during passages 4 to 5. Conversely, in passages 3 to 5, female cells demonstrated increased expression. Additionally, male cells exhibited greater fold changes in the expression of immunomodulatory factors and genes [25].

3.8. Quality of Studies

A modified version of the OHAT tool was utilized to evaluate each study, applying certain criteria from the 11 questions outlined in the table below. In summary, 12 studies were determined to have a low risk overall. However, all 16 studies were identified as having a high risk in the areas of “Confidence in outcome assessment (including assessor blinding)” and likely a high risk in “Blinding of research personnel” (see Table 5). Additionally, five studies raised concerns regarding “Accounting for important confounding/modifying variables [39]”, while four studies presented issues related to “Incomplete outcome data”. Despite these specific concerns, none of the studies were categorized as high risk. All 16 studies included in this review were ultimately deemed to be of low risk and high quality.

Table 5.

Risk of bias analysis/assessment.

4. Discussion

The role of gender in the differentiation potential of MSCs remains an area that requires further research, as it is not clear whether gender influences. Furthermore, it is not clear whether this influences the capacity of MSCs to differentiate into chondrogenic, adipogenic or osteogenic cells. Understanding this may be able to inform the researcher into the biochemical drivers behind cell differentiation that may be underpinning and driving superior lineage differentiation in the hope of optimizing conditions to transplant these cells in vivo to patients with varying osteoarthritic conditions afflicting cartilage and bone.

Of the 16 studies identified, 7 studies looked at the role of sex in the ability of cells to differentiate into chondrocytes, and 4 studies showed that sex did not demonstrate any statistical significance in their cell differentiation. This appears to imply that in both cell populations from different sexed donors, there is no influence on the ability of an MSC to drive towards a chondrogenic lineage.

On the other hand, two studies out of six were able to demonstrate that male donors preferentially drove both proliferation rates and osteogenic cell lineage from those MSCs deriving from male donors. Studies [24,35] appear to show that the abundance of mineralized matrix was statistically significant in those MSCs from male donors as opposed to female ones. Aksu et al. (2008) demonstrated that the speed of osteogenic differentiation is faster in males, whereas Scibatta et al. (2019) showed a more rapid rate in the initial first two weeks of cell induction but a plateauing rate at the four- and six-week mark where this becomes equivocal and comparable to females. West et al. (2016) concluded that these may show that male donors can commit early to in vitro myogenesis but not in vivo, where female cells appear to show more propensity for differentiation.

Three of the studies looked, additionally, at the role of age donor on the MSCs. The study found that donor age minimally impacts MSC differentiation. Adipogenesis was consistent across age groups, while chondrogenesis significantly increased in donors aged 30s and 50s by day 16. Older donors may offer enhanced potential for cartilage repair therapies [26]. The study found that age does not significantly impact the chondrogenic potential of bone marrow-derived MSCs in elderly patients (60+). MSCs from older donors, including those with osteoarthritis or fractures, effectively differentiated into chondrocytes, showing consistent therapeutic potential for cartilage repair across ages and sexes [27]. Age affects muscle progenitor cells (MPCs) differently by sex. Older male donors show impaired MPC expansion, increased cell death, and altered metabolism, while older female donors maintain their cells’ function and metabolic balance. These findings highlight a greater age-related decline in MPCs from males than females [32].

It is well established that bone density and mineralization are stronger in men in comparison to women and is related to hormonal influences on osteogenesis with the role of testosterone which increases the rate and density of bone deposition. Equally, it is believed that this hormonal influence explains the differing predisposition of post-menopausal women to low bone mass and susceptibility to fragility fracture with the reduced bone density and loss of estrogen-derived homeostasis of bone metabolism. These two studies, however, appear to show a further mechanism may be at play which has been not previously appreciated in allowing increased osteogenic differentiation in male cells. Given that these studies are performed in vitro, it would be difficult to explain this as a result of hormonal transcription factors influencing bone morphology, but they may represent pathways relevant to associated genes which are present in male cells in comparison to female cells. This remains unclear and more exploration would be required through the use of genomic studies and transcriptomics to interrogate these interplaying factors. Further analysis of these genetic pathways through genomic and transcriptomic studies may help shed light as to which genes influence these male cells compared to female cells.

The difficulty however in this systematic literature review remains the variation in the different protocols used to culture, identify and characterize adipogenic, chondrogenic and osteogenic cells. As a result, many of the results appear to show no significant difference between both sexes. Still, given the variability of the results, it is difficult to know if this is a result of the methodology utilized to culture these cells as well as tissue source, patient age and broader health status. Other confounding variables include the heterogeneity of the MSC source from various tissues as well as variations in donor age and a lack of reporting of the general health status of donor patients. Uniformity in the protocols used may provide researchers with a better understanding as to whether gender influences these cells. This remains one of the difficulties in trying to ascertain a meaningful answer on whether gender influences MSC cell differentiation.

5. Conclusions

This review underscores the absence of a consensus regarding the influence of gender on the chondrogenic and adipogenic potential of MSCs while suggesting a potential role in osteogenic potential. Additionally, it highlights that gender may affect cell characterization and proliferation. However, due to the diverse methodologies employed in existing studies, conclusive statements about gender’s impact on cell differentiation and proliferation remain challenging. Standardization of methodologies could facilitate future investigations into gender-specific effects on MSC differentiation and proliferation. Furthermore, the site of MSCs and age have emerged as influential factors, prompting the recommendation for a comprehensive study with uniform protocols to examine the interplay of gender, age, and site on MSC properties. Such research could inform the selection of optimal tissues for regeneration and musculoskeletal therapies.

Author Contributions

A.V. and W.K. were responsible for the conceptualization of the study, methodology, manuscript preparation, and review. A.V. performed the initial formal analysis. Data curation was performed by A.F., J.K. and A.V. Project supervision and funding acquisition were performed by W.K., M.B. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Evelyn Medical Research Grant (Project Ref: 20-15) as well as of the Versus Arthritis (Formerly Arthritis Research UK) through Versus Arthritis Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Therapies Centre (Grant 21156).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This scientific paper was supported by the Onassis Foundation—Scholarship ID: F ZS 069-1/2022-2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, Y.H.; Yoon, D.S.; Kim, H.O.; Lee, J.W. Characterization of different subpopulations from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells by alkaline phosphatase expression. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 2958–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowles-Welch, A.C.; Jimenez, A.C.; Stevens, H.Y.; Rubio, D.A.F.; Kippner, L.E.; Yeago, C.; Roy, K. Mesenchymal stromal cells for bone trauma, defects, and disease: Considerations for manufacturing, clinical translation, and effective treatments. Bone Rep. 2023, 18, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelke, A.R.; Roscoe, J.A.; Morrow, G.R.; Colman, L.K.; Banerjee, T.K.; Kirshner, J.J. Genetic alterations NIH Public Access. Bone 2008, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, A.F.; Rackwitz, L.; Gilbert, F.; Nöth, U.; Tuan, R.S. Concise Review: The Clinical Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Musculoskeletal Regeneration: Current Status and Perspectives. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimble, J.M.; Guilak, F.; Nuttall, M.E.; Sathishkumar, S.; Vidal, M.; Bunnell, B.A. In vitro differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2008, 35, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, A.; Kapetanos, K.; Christodoulou, N.; Asimakopoulos, D.; Birch, M.A.; McCaskie, A.W.; Khan, W. The Effects of Chronological Age on the Chondrogenic Potential of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Shen, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, T.; Han, L.; Hamilton, J.L.; Im, H.-J. Osteoarthritis: Toward a comprehensive understanding of pathological mechanism. Bone Res. 2017, 5, 16044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Wu, W.; Qu, X. Mesenchymal stem cells in osteoarthritis therapy: A review. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.G.; Kim, M.K.; Jeon, Y.S.; Nam, Y.C.; Park, J.S.; Ryu, D.J. State of the Art: The Immunomodulatory Role of MSCs for Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempson, G.E.; Muir, H.; Swanson, S.A.V.; Freeman, M.A.R. Correlations between stiffness and the chemical constituents of cartilage on the human femoral head. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 1970, 215, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, R.A.; Dolan, E.E. Ligament Injury and Healing: An Overview. J. Prolotherapy 2011, 3, 836–846. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Rothrauff, B.B.; Tuan, R.S. Tendon and ligament regeneration and repair: Clinical relevance and developmental paradigm. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 2013, 99, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, V.; Tennyson, M.; Zhang, J.; Khan, W. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in tendon and ligament repair—A systematic review of in vivo studies. Cells 2021, 10, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.F.; Zhang, X.Q.; Yao, Z.Y.; Mao, H.J. Advances in mesenchymal stem cells therapy for tendinopathies. Chin. J. Traumatol.-Engl. Ed. 2024, 27, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammour, I.; Somashekar, S.; Huang, J.; Batlahally, S.; Breton, M.; Valasaki, K.; Khan, A.; Wu, S.; Young, K.C. The effect of gender on mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) efficacy in neonatal hyperoxia-induced lung injury. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman-Blas, J.A.; Castañeda, S.; Largo, R.; Herrero-Beaumont, G. Osteoarthritis associated with estrogen deficiency. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.V.; Soelaiman, I.N.; Chin, K.Y. A concise review of testosterone and bone health. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozen, T.; Ozisik, L.; Calik Basaran, N. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.X.; Yu, Q. Primary osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2015, 1, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pang, H.; Chen, S.; Klyne, D.M.; Harrich, D.; Ding, W.; Yang, S.; Han, F.Y. Low back pain and osteoarthritis pain: A perspective of estrogen. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 checklist. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Document, T.; OHAT Risk of Bias Rating Tool for Human and Animal Studies. Organization of This Document Indirectness, Timing, and Other Factors Related to Risk of Bias 2015. pp. 1–37. Available online: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/sites/default/files/ntp/ohat/pubs/riskofbiastool_508.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Aksu, A.E.; Rubin, J.P.; Dudas, J.R.; Marra, K.G. Role of gender and anatomical region on induction of osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2008, 60, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolliopoulos, V.; Tiffany, A.; Polanek, M.; Harley, B.A.; Harley, B. Donor Variability in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Osteogenic Response As a Function of Passage Conditions and Donor Sex. bioRxiv 2023. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38014316/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Lee, H.; Min, S.; Park, J. Effects of demographic factors on adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation in bone marrow-derived stem cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 3548–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, F.; Alegre-Aguarón, E.; Desportes, P.; Royo-Cañas, M.; Castiella, T.; Larrad, L.; Martínez-Lorenzo, M.J. Chondrogenic differentiation in femoral bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells (MSC) from elderly patients suffering osteoarthritis or femoral fracture. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 52, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossett, E.; Khan, W.S.; Pastides, P.; Adesida, A.B. The effects of ageing on proliferation potential, differentiation potential and cell surface characterisation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2012, 7, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, G.; Kluba, T.; Hermanutz-Klein, U.; Bieback, K.; Northoff, H.; Schafer, R. Phenotype, donor age and gender affect function of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.C.; Hardy, W.R.; Murray, I.R.; James, A.W.; Corselli, M.; Pang, S.; Black, C.; Lobo, S.E.; Sukhija, K.; Liang, P.; et al. Prospective purification of perivascular presumptive mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue: Process optimization and cell population metrics across a large cohort of diverse demographics. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stölting, M.N.L.; Hefermehl, L.J.; Tremp, M.; Azzabi, F.; Sulser, T.; Eberli, D. The role of donor age and gender in the success of human muscle precursor cell transplantation. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 11, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, E.S.; Bender, E.L.; Thalacker-Mercer, A.E. Expansion capacity of human muscle progenitor cells differs by age, sex, and metabolic fuel preference. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2018, 315, C643–C652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reumann, M.K.; Linnemann, C.; Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Arnold, S.; Held, M.; Seeliger, C.; Nussler, A.K.; Ehnert, S. Donor site location is critical for proliferation, stem cell capacity, and osteogenic differentiation of adipose mesenchymal stem/stromal cells: Implications for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto-Durán, E.; Mejía-Cruz, C.C.; Leal-García, E.; Pérez-Núñez, R.; Rodríguez-Pardo, V.M. Impact of donor characteristics on the quality of bone marrow as a source of mesenchymal stromal cells. Am. J. Stem Cells 2018, 7, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scibetta, A.C.; Morris, E.R.; Liebowitz, A.B.; Gao, X.; Lu, A.; Philippon, M.J.; Huard, J. Characterization of the chondrogenic and osteogenic potential of male and female human muscle-derived stem cells: Implication for stem cell therapy. J. Orthop. Res. 2019, 37, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, M.; Hildebrand, M.; Menzel, U.; Fahy, N.; Alini, M.; Lang, S.; Benneker, L.; Verrier, S.; Stoddart, M.J.; Bara, J.J. Phenotypic characterization of bone marrow mononuclear cells and derived stromal cell populations from human iliac crest, vertebral body and femoral head. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckinnirey, F.; Herbert, B.; Vesey, G.; McCracken, S. Immune modulation via adipose derived Mesenchymal Stem cells is driven by donor sex in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.; Na CBin Song, I.S.; Ryu, J.J.; Park, J.B. Evaluation of the age-and sex-related changes of the osteogenic differentiation potentials of healthy bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Medicina 2021, 57, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Ng, J.; Kim, S.B.; Sonn, C.H.; Lee, K.M.; Han, S.B. Effect of Donor Age on the Proportion of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Anterior Cruciate Ligaments. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).