Abstract

Aim: The aim of this review was to identify the microRNAs (miRNAs) present in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) that can be used as biomarkers for the diagnosis of periodontal diseases, and to determine which of them has a higher diagnostic yield for periodontitis. Methods: The review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines (reference number CRD42024544648). The Pubmed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases were searched for clinical studies conducted in humans investigating periodontal diseases and miRNAs in GCF. The methodological quality of the articles was measured with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. Results: A total of 3222 references were identified in the initial literature search, and 16 articles were finally included in the review. The design of the studies was heterogeneous, which prevented a meta-analysis of the data. Most of the studies compared miRNA expression levels between patients with periodontitis and healthy controls. The most widely researched miRNA in periodontal diseases was miR-200b-3p and miR-146a. Conclusions: the miRNAs most studied are miR-146a, miR-200b, miR-223, miR-23a, and miR-203, and all of them except miR-203 have an acceptable diagnostic plausibility for periodontitis.

1. Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic, multifactorial, and immunoinflammatory disease of microbial etiology, characterized by the destruction of the supporting dental tissues, which can lead to tooth loss [1].

The main etiological factor is the bacteria living in the biofilm [2]. A biofilm dysbiosis initiates the innate immune response which, in an effort to protect the organism, can in some individuals produce an exaggerated inflammatory immune response. This response can contribute to establishing a chronic low-grade inflammatory environment over long periods, thus contributing to the pathogenesis of periodontitis [2,3].

This is why inflammation and the immune response play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Any change in gene expression can alter the responses to inflammation and immunity. The process by which gene expression is modified without altering the DNA sequence is known as epigenetics [2].

Epigenetics includes processes such as DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, histones post-translational modification, and non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) [2].

MiRNAs are short non-coding RNAs (19–24 nucleotides in length) that function through translational inhibition or mRNA destabilization via specific sequence binding sites within the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of genes [4]. They regulate post-transcriptional gene expression, thereby influencing many biological processes in human cells that depend on DNA transcription and protein synthesis [2].

MiRNAs are considered an epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression and consequently modulates various cellular processes, such as cell growth, apoptosis, and cellular differentiation. Additionally, miRNAs play a fundamental role in inflammatory responses and in the development of diseases [5].

Systemic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [6], diabetes mellitus (DM) [3,7,8], obesity [9], and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [10,11], all characterized by low-grade inflammation similar to that produced in periodontitis, are associated with alterations in miRNA levels.

Currently, clinical parameters such as clinical attachment loss (CAL), probing pocket depth (PPD), the presence and extent of angular bone defects, and the presence of furcation lesions, among others, are used to evaluate periodontal diseases. These parameters are aimed at determining the treatment and prognosis of the pathology. Therefore, their utility is limited for establishing an early diagnosis. Hence, identifying biomarkers that support the early diagnosis of periodontal diseases could be useful in reducing its incidence [12,13].

The most notable therapeutic importance of using a biomarker such as miRNA lies in its potential to detect periodontitis at an early stage, when periodontal tissue lesions are not yet clinically detectable. Consequently, this allows for early treatment of the disease to halt its progression before periodontal lesions are established [14].

When miRNAs are overexpressed or underexpressed, they can lead to changes in gene expression that may contribute to the onset and/or clinical progression of periodontitis [2]. Dysregulation of miRNAs can be detected in various bio-fluids such as serum, saliva, urine, gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), or cerebrospinal fluid. This makes them ideal candidates as specific and sensitive biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of many diseases [15,16].

The reason biofluids were proposed as excellent sources for miRNA biomarker research includes the ease of isolation and identification of miRNAs using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), the less invasive nature of miRNA sample collection, and their high stability in various biofluids [17].

In the context of periodontium, the most important biofluid is GCF. It flows passively from the gingival sulcus at the interface between the tooth and adjacent gum tissue. The volume of GCF increases and its composition alters according to the inflammatory status or disease of a specific periodontal site [18,19].

In recent years, numerous studies were published on the relationship between miRNAs and periodontal diseases, yet there is considerable heterogeneity in the literature regarding the miRNAs studied. The objective of this systematic review was to identify and summarize which miRNAs present in human GCF can be used as biomarkers for the diagnosis of periodontal diseases, and to determine which of them show the highest diagnostic performance for periodontitis.

2. Materials and Methods

The present review followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 statement [20], whose item compliance list can be seen in Table S2. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO under ID: CRD42024544648. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42013004648 (accessed on 23 July 2024)

The Population, Exposition, Comparison, Outcome (PECO) question [21] formulated was as follows: Population (humans), Exposure (miRNAs expression in GCF), Comparison (healthy individuals), and Outcome (diagnosis of periodontal diseases). Therefore, the research question to be addressed was: What are the miRNAs present in human GCF that can be used as diagnostic biomarkers to differentiate subjects with periodontal disease from healthy individuals?

The inclusion criteria were cross-sectional, case-control, cohort, or experimental studies conducted in humans; using samples of GCF; addressing periodontitis and gingivitis; and analyzing miRNAs.

Regarding the exclusion criteria, studies lacking a control group or in vitro experimentation studies were excluded.

To retrieve all relevant studies that addressed the PECO question formulated, a rigorous search was conducted on 26 January 2024, across the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. No language or time limits were applied. The search was updated on 30 May 2024.

Additionally, a manual search was conducted on published systematic reviews on the topic, and the reference lists of articles used in this review were consulted.

To formulate the search strategy, a terminological analysis was initially performed. The process of formulating the search equations and their application in each of the databases was carried out by a single researcher (M.C.-V.).

The generic search strategy used was as follows: (“MicroRNAs” OR “MicroRNA” OR “miRNA” OR “miRNAs” OR “Micro RNA” OR “Micro RNAs” OR “mi-RNA” OR “mi-RNAs” OR “Primary MicroRNA” OR “Primary miRNA” OR “pri-miRNA” OR “pri miRNA” OR “pre-miRNA” OR “pre miRNA” OR “stRNA” OR “Small Temporal RNA”) AND (“Periodontal disease” OR “Periodontal diseases” OR “Gingivitis” OR “Periodontitis” OR “Gingival” OR “Periodontal” OR “Parodontosis” OR “Parodontoses” OR “Pyorrhea Alveolaris”).

This strategy was adapted for each of the databases consulted, as detailed in Table S1, aiming to strike a balance between precision and comprehensiveness. Therefore, the search was conducted by title and abstract, and using indexed terms in the MeSH thesaurus for PubMed and indexed terms in the Emtree thesaurus for Embase.

The article selection process, after removing duplicates, was independently conducted by two researchers (M.C.-V. and P.J.A.-P.) who evaluated the title and abstract. In cases of uncertainty, a third researcher (A.L.-R.) was consulted. Articles that could not be decisively rejected based on title and abstract were reviewed in full text.

Following this initial screening, all selected articles were read in full text to determine their inclusion or exclusion. Reasons for exclusion were noted for rejected articles.

The quality of observational studies included in the review was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for case-control studies. This scale, developed by Wells et al. in 2000 [22], evaluates eight items to determine the methodological quality of the study under analysis. These items are divided into three categories: selection, comparability, and exposure/outcome. Each observational study could score a maximum of nine points.

The quality assessment was conducted independently by two researchers (M.C.-V. and P.J.A.-P.), with a third researcher (A.L.-R.) consulted in case of uncertainty.

From each article, the following data were extracted: author and year of publication, country, study type, sample size, age, type of periodontal diseases studied, and the classification used, miRNAs studied, and outcomes (miRNA expression levels, area under the curve, and sensitivity and specificity as a diagnostic tool).

Data extraction was also independently performed by two researchers (M.C.-V. and P.J.A.-P.), with a third researcher (A.L.-R.) consulted in case of uncertainty.

The results were collected and synthesized in different Excel tables based on the objectives set to facilitate the comparison and analysis of the various extracted data.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

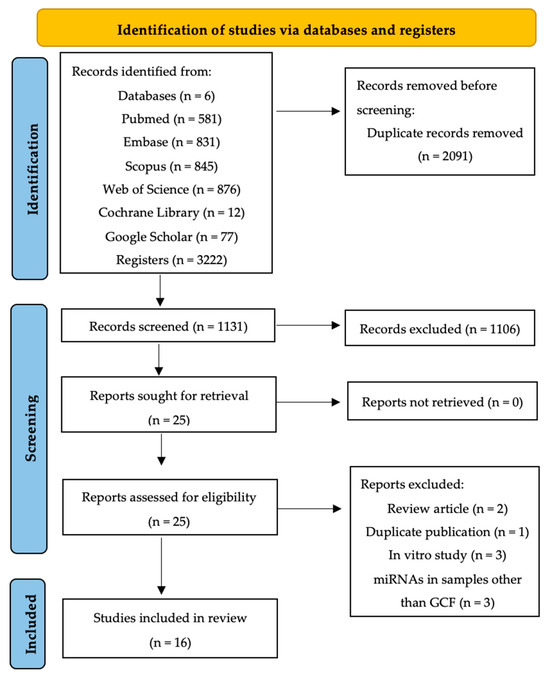

The search strategy was conducted across six different databases, yielding: 581 documents in PubMed, 831 in Embase, 845 in Scopus, 876 in Web of Science, 12 in Cochrane Library, and 77 in Google Scholar. In total, 3222 documents were retrieved, and after removing duplicates (n = 2091) across databases, 1131 remained for title and abstract screening.

Manual searching did not yield any articles not previously retrieved through electronic search.

Initial screening after title and abstract review excluded 1106 documents. Most were excluded because they were literature reviews or editorials (n = 359), in vitro or animal studies (n = 445), not related to the research question (n = 15), studying other genetic mechanisms or pathologies (n = 190), retracted studies (n = 7), or investigating miRNA expression in samples other than GCF (n = 90).

Twenty-five articles met the inclusion criteria or lacked sufficient information in the title and abstract for rejection. Upon full-text reading, nine articles were excluded (Table S4). Reasons for exclusion were review article (n = 2), duplicate publication (n = 1), in vitro experimental study (n = 3), and investigating miRNA expression in samples other than GCF (n = 3).

Therefore, sixteen articles were finally included in the qualitative review. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the article selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the search process across the different databases.

3.2. Quality Assessment

Quality assessment for observational studies is detailed in Table 1. Overall, the quality assessment showed positive outcomes, as 13 out of the 16 included studies demonstrated good quality. Among the three studies that showed fair quality [13,23,24], biases mainly stemmed from not specifying the source of cases and/or controls, inadequate control of confounding factors, and failure to specify the non-response rate.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of observational studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS).

3.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

The characteristics of the studies included in the review are summarized in Table 2. Of the sixteen selected studies, all were observational case-control studies. Sample sizes varied across studies, ranging from 18 [31] to 216 [23] patients, with mean ages ranging from 27.8 years [13] to 65.3 years [13].

Table 2.

Characteristics and main results of included studies.

Most studies compared miRNA expression levels between patients with periodontitis and healthy controls. However, some authors assessed the influence of systemic diseases such as DM [7,8], AR [11,28], or CVD [6] on relative miRNA expression levels.

The Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions 2018 [32] was used in two-thirds of the studies, while the other third used the Armitage classification [33,34].

Upon analyzing the miRNAs proposed in the various included studies, it was observed that the information was highly heterogeneous, with the most analyzed ones being:

- miR-146a [7,19,28]

- miR-200b family:

- −

- miR 200b [3,8]

- −

- miR-200b-3p [3,6,8,13,23]

- −

- miR 200b-5p [6,23]

- miR-223 family:

- −

- miR-223 [3,8,13,25,26,31,35]

- −

- miR-223-3p [13,25]

- −

- miR 223-5p [6,31]

- miR-23a [8,24,25]

- miR-203 [3,8,13]

In most of these studies, miRNA expression levels (Table S3) were found to be upregulated in patients with periodontal involvement. However, some studies reported contradictory results:

- o

- miR-21-3p: was found to be overexpressed in one study [6] and underexpressed in another [13].

- o

- miR-146a-5p: was found to be overexpressed in two studies [7,19] and underexpressed in another [28].

- o

- miR-200a-5p: was found to be overexpressed in one study [23] and underexpressed in another [13].

- o

- miR-200b-3p: showed no alteration in two studies [6,23] and underexpressed in another [13].

- o

- miR-200b-5p: was found to be overexpressed in one study [23] and showed no alteration in another [13].

- o

- miR-200c-3p: showed no alteration in one study [23] and underexpressed in another [13].

- o

- miR-200c-5p: was found to be overexpressed in one study [23] and underexpressed in another [13].

In Table 3, a summary of the miRNAs that were shown to be over- or underexpressed according to the severity of periodontitis can be observed.

Table 3.

Over- or underexpressed miRNAs according to the severity of periodontitis.

Additionally, some authors observed correlation between relative expression levels of specific miRNAs and disease severity, showing positive correlation for miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c [23]; miR-103a-3p, miR-423-5p [25]; miR-223 [8,26]; miR-30b-3p, miR-125b-1-3p [27], miR-140-3p, miR-145-5p [28], and miR-3198 [11]; no correlation for miR-15a-5p and miR-223-3p [25]; and negative correlation for miR-23a-3p [25], miR-146a-5p [28], and miR-28-5p [29].

Regarding the use of miRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for periodontitis, the proposed miRNAs were miR-200b [3,8,23], miR-146a-5p [7,19,28], and miR-223 [3,8,26]. Table 4 illustrates the miRNAs described as diagnostic biomarkers with values of area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity.

Table 4.

Diagnostic performance of miRNAs used in included studies.

4. Discussion

In the etiopathogenesis of periodontitis, epigenetic mechanisms such as miRNAs appear to play a crucial role in inflammation regulation. Despite miRNAs being proposed years ago as biomarkers for periodontal diseases, there remains considerable variability among the miRNAs studied and the type of samples used. This review was conducted to identify the miRNAs described in the literature for the diagnosis of periodontal diseases, focusing on studies using GCF samples. This biofluid is considered easily accessible, minimally invasive, and closely related to the site of inflammation, namely the periodontium.

Due to the impossibility of conducting a data synthesis and meta-analysis, some items (13, 14, 20, 22, and 23b) of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [20] were not fulfilled.

4.1. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Studies

In the assessment of the quality of observational studies, selection bias was observed in two studies [23,24] due to two reasons: lack of representativeness of cases and failure to specify the origin of controls. This bias was mitigated by controlling for confounding factors and achieving comparable study groups.

The sample size of a study influences the reproducibility of results. Small sample sizes can lead to the generation of false positives or negatives due to the limited portion of the sampled population, as seen in Almiñana-Pastor et al. (2023) [19] with N = 23, Micó-Martínez et al. (2018) [31] with N = 18, and Saito et al. (2017) [13] with N = 20. Therefore, the validity of findings from these studies is compromised. Similarly, studies that showed disparities between healthy and diseased groups [28] also could not achieve the same validity, as one of the groups was underrepresented.

The disease classification alongside the selected miRNAs were two variables that exhibited significant variation across the studies, complicating interpretation and comparison of results. Most of the studies [3,6,8,11,25,26,27,28,29,36] utilized the current Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions 2018 [1], with a diversity in the stages selected, predominantly focusing on stages II, III, and IV [11,25,27,28], which could correspond to moderate/severe periodontitis in the older Armitage classification [33,34].

It is noteworthy that only Rovas et al. (2022) [28], Zhu and Zhong (2022) [27], and Yu (2023) [23] included subjects in stage I, indicating that only three studies considered individuals in the early stages of periodontitis—a critical focus for identifying disease markers. Subsequently, studies should examine extreme groups (healthy subjects and those with advanced disease). Additionally, no article considered comparing miRNA levels across different grades, which is essential, as it refers to disease progression: Grade A (low susceptibility to progression), Grade B (moderate susceptibility to progression), and Grade C (high susceptibility to progression).

Similarly, only two authors [7,24] measured miRNA levels basic periodontal treatment, confirming that miRNA levels decrease to physiological levels once inflammation is eliminated and the disease is controlled. This underscores the dynamic nature of these markers and their role in regulating cellular immune-inflammatory states.

4.2. MiRNA

In the search for miRNAs present in GCF, only Almiñana-Pastor et al. (2023) [19] conducted high-throughput sequencing, while the remaining authors focused on specific miRNA searches, potentially excluding miRNAs that could be considered biomarkers for periodontal diseases.

Among the most studied miRNAs was the miR-200b family, specifically miR-200b-3p. MiR-200b is involved in the differentiation of various immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and others, and plays a significant role in the early stages of infection and inflammation [8]. In the vast majority of studies, miR-200b-3p levels were significantly elevated in GCF [3,6,8,23], although Saito et al. (2017) [13] reported lower levels, possibly due to their small sample size. Furthermore, miR-200b was associated with comorbidities such as periodontitis and type 2 DM [3,8], and periodontitis and CVD [6]. Elevated levels of miR-200b were also observed in gingival biopsies of subjects with obese periodontitis [37] and in gingival tissues [38]. These studies open new avenues for further research into the relationship between systemic diseases and periodontal diseases.

Both type 2 DM and CVD are chronic conditions that, similar to periodontitis, contribute to generating low-grade inflammation over long periods of time. Since miR-200b is involved in the initial stages of inflammation, the presence of not just one but two inflammatory pathologies will result in even higher miRNA levels in the presence of comorbidities. In the study by Liu et al. (2022) [8], the expression levels of miR-200b in the periodontitis group and the T2DM group were 3.06 ± 0.21 and 2.74 ± 0.22, respectively, while in the comorbid group, the levels were 3.51 ± 0.30, showing statistically significant differences compared to the other groups.

MiR-146a plays a role in various inflammatory processes and is involved in the activation of signaling pathways and cytokine secretion. It is also affected by pro-inflammatory stimuli, such as lipopolysaccharides from Porphyromonas Gingivalis (LPS), which, in response to bacterial stimuli, negatively regulates membrane receptor (TLR) signaling, favoring bacterial pathogenic action. MiR-146a was found to be upregulated in the studies by Almiñana-Pastor et al. (2023) [19] and Radović et al. (2018) [7]. In fact, in the latter study, miR-146a levels normalized after non-surgical periodontal treatment, indicating its expression is related to the inflammatory process of periodontitis.

However, different results were obtained in the study by Rovas et al. (2022) [27], where miR-146a levels were underexpressed in subjects with periodontitis compared to healthy subjects. The hypothesis suggested for these results is that negative regulation or impaired function of miR-146a may be associated with diseases characterized by sustained exaggerated inflammation, such as aggressive forms of periodontitis. Multiple studies analyzed miR-146a in gingival biopsies [39,40], saliva [41,42], or in vitro [43] and observed its overexpression in periodontitis. Therefore, further studies with larger samples in GCF are needed to conclusively determine whether miR-146a is under or overexpressed in periodontal diseases.

The overexpression of certain miRNAs, such as miR-23a, plays a destructive role in disease progression as it could inhibit osteogenesis [44]. Costantini et al. (2023) [25] observed statistically significant increases in levels of this miRNA in patients with mild-stage periodontitis compared to healthy subjects and moderate to severe stages. In the study by Zhang et al. (2019) [24], miR-23a significantly increased not only in GCF, but also in human periodontal ligament stem cell (PDLSC) cultures, inhibiting osteogenesis, and levels decreased significantly following periodontal therapy. This suggests that miR-23a may be elevated in all stages of the disease, playing a greater role in bone loss during the early phases of periodontitis. Therefore, studying its alteration in the subclinical stages of the disease would be interesting, as it may act as an initiator of bone metabolism disturbance.

One of the changes occurring in inflamed tissues is increased angiogenesis. In the case of periodontal diseases, miR-203 plays a crucial role in this change by targeting vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), thereby inhibiting angiogenesis [45]. Thus, underexpression of miR-203 could be associated with the presence of periodontitis. The three studies that included miR-203 among the studied miRNAs found it to be underexpressed [3,8,13]. In fact, Liu et al. (2022) [8] and Elazazy et al. (2021) [3] observed a negative correlation of miR-203 with TNF-α, explaining the decreased healing and suggesting its impact on irreversible damage caused by the disease. Similar results were seen in other studies conducted on gingival tissue [16,46]. Therefore, miR-203 could potentially play a protective role in periodontitis, not only for diagnosis, but also as a therapeutic target.

Another extensively studied miRNA was miR-223, which functions as a key regulator of innate immunity by influencing the differentiation of various immune cells [47] and is crucial in regulating osteoclast differentiation, thus impacting the pathological process of bone remodeling [48].

Two included studies [3,8] reported that miR-223 expression levels in GCF were higher in patients with periodontitis compared to healthy controls, with one of them showing statistically significant differences [8]. Both articles included subjects with periodontitis, with and without DM, and in both studies, miR-223 levels were much higher in subjects with periodontitis and DM compared to those with periodontitis alone. This finding holds promise for precision medicine, as GCF can reveal miRNAs associated with systemic pathologies. Similar results of overexpression were found in gingival tissue biopsies [37], in the serum of a mouse model with periodontitis [47], and in gingival crevicular blood [35].

There also appeared to be a positive correlation between miR-223 levels and disease severity, as determined by increased TNF-α and clinical parameters in the chronic periodontitis group compared to healthy controls [3]. However, in the study by Costantini et al. (2023) [25], miR-223-3p did not show correlation with the severity of periodontitis.

Given that for a diagnostic tool to be considered acceptable, it should have an AUC > 0.8 [49], among all the miRNAs proposed as diagnostic biomarkers, those that could truly be employed for the diagnosis of periodontitis were: miR-146a [7], miR-23a [24], miR-28-5p [29], miR-155 [7], miR-125b-1-3p [27], miR-200c-3p [23], miR-200b [8], miR-30b-3p [27], miR-200a-5p [23], miR-1226 [30], miR-200a-3p, miR-200b-5p [23], miR-223 [8], miR-223-5p [26], miR-200c-5p [23], and miR-200b-3p [23]. Therefore, the rest of the miRNAs proposed by authors as possible biomarkers for periodontitis, although they might have an AUC close to 0.8, would not achieve sufficient performance to be used as a diagnostic tool. Increasing the sample size could potentially change this result, hence, more well-designed studies are needed to analyze the diagnostic value of these miRNAs.

4.3. Limitations of the Review

The main limitation was the inability to perform a quantitative analysis of the data due to methodological differences among studies, particularly the discrepancies in the miRNAs studied across different studies, the absence of numerical data in publications, and the inability to obtain them through contact with authors. Additionally, different units of miRNA expression were used without the possibility of converting them into a common unit.

Another limitation was the lack of search in grey literature, which possibly resulted in selection bias by excluding relevant research from the review.

4.4. Future Recommendations

This systematic review identified the need for a more homogeneous approach within published studies on the identification of miRNAs in GCF in subjects with periodontitis:

- Following the miRNA high-throughput sequencing by Almiñana-Pastor et al. (2023) [19], and once the miRNAs involved in periodontitis are identified, efforts should focus on those that demonstrated differences between subjects with periodontal disease and those with healthy gingiva, to avoid costly comprehensive sequencing studies and to limit the selected sample.

- Employing the classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions from 2018.

- Studying how miRNA expression levels vary among different grades of periodontitis as another item to establish disease progression.

- Standardizing the units of miRNA expression to enable quantitative data analysis, rather than limiting ourselves to the binary terms overexpressed and underexpressed.

- Conducting follow-up studies to re-measure miRNA levels after basic periodontal treatment.

5. Conclusions

MiRNAs were proposed as promising biomarkers for periodontal diseases in GCF, capable of reflecting the inflammatory regulation status of periodontal tissues at a given moment. Among the miRNAs that showed significant differences between individuals with periodontitis and periodontally healthy subjects are miR-146a, miR-200b (specifically miR-200b-3p), miR-223, miR-23a, and miR-203. These miRNAs, except for miR-203, exhibited acceptable diagnostic performance for use as diagnostic biomarkers. However, due to the substantial heterogeneity in the miRNAs studied, there is a need for studies with more homogeneous criteria that allow for quantitative synthesis to better assess their diagnostic utility.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms25158274/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.-V. and P.J.A.-P.; methodology, M.C.-V.; validation, P.J.A.-P.; investigation, M.C.-V., P.J.A.-P. and A.L.-R.; data curation, M.C.-V., P.J.A.-P., A.L.-R. and J.L.G.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.-V.; writing—review and editing, P.J.A.-P., A.L.-R. and J.L.G.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tonetti, M.S.; Greenwell, H.; Kornman, K.S. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S159–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laberge, S.; Akoum, D.; Wlodarczyk, P.; Massé, J.-D.; Fournier, D.; Semlali, A. The Potential Role of Epigenetic Modifications on Different Facets in the Periodontal Pathogenesis. Genes 2023, 14, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elazazy, O.; Amr, K.; Abd El Fattah, A.; Abouzaid, M. Evaluation of serum and gingival crevicular fluid microRNA-223, microRNA-203 and microRNA-200b expression in chronic periodontitis patients with and without diabetes type 2. Arch. Oral Biol. 2021, 121, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Zhou, X.; Trombetta-eSilva, J.; Francis, M.; Gaharwar, A.K.; Atsawasuwan, P.; Diekwisch, T.G.H. MicroRNAs and Periodontal Homeostasis. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, L.; Garaicoa-Pazmino, C.; Asa’ad, F.; Castilho, R.M. Understanding the role of endotoxin tolerance in chronic inflammatory conditions and periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Santonocito, S.; Distefano, A.; Polizzi, A.; Vaccaro, M.; Raciti, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Li Volti, G. Impact of periodontitis on gingival crevicular fluid miRNAs profiles associated with cardiovascular disease risk. J. Periodontal Res. 2023, 58, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radović, N.; Nikolić Jakoba, N.; Petrović, N.; Milosavljević, A.; Brković, B.; Roganović, J. MicroRNA-146a and microRNA-155 as novel crevicular fluid biomarkers for periodontitis in non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xiao, Z.; Ding, W.; Wen, C.; Ge, C.; Xu, K.; Cao, S. Relationship between microRNA expression and inflammatory factors in patients with both type 2 diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 6627–6637. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, A.R.; Brambila, M.F.; Martínez, G.; Chapa, G.; Nares, S. Dysregulation of human miRNAs and increased prevalence of HHV miRNAs in obese periodontitis subjects. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragaite-Staponkiene, B.; Rovas, A.; Puriene, A.; Snipaitiene, K.; Punceviciene, E.; Rimkevicius, A.; Butrimiene, I.; Jarmalaite, S. Gingival Tissue MiRNA Expression Profiling and an Analysis of Periodontitis-Specific Circulating MiRNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovas, A.; Puriene, A.; Snipaitiene, K.; Punceviciene, E.; Buragaite-Staponkiene, B.; Matuleviciute, R.; Butrimiene, I.; Jarmalaite, S. Analysis of periodontitis-associated miRNAs in gingival tissue, gingival crevicular fluid, saliva and blood plasma. Arch. Oral Biol. 2021, 126, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas-González, M.V.; Suaste-Olmos, F.; García-Calderón, A.G.; Tovar-Carrillo, K.; Espinosa-Cristóbal, L.F.; Nava-Martínez, S.D.; Cuevas-González, J.C.; Zambrano-Galván, G.; Saucedo-Acuña, R.A.; Donohue-Cornejo, A. Expression of MicroRNAs in Periodontal Disease: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 2069410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.; Horie, M.; Ejiri, K.; Aoki, A.; Katagiri, S.; Maekawa, S.; Suzuki, S.; Kong, S.; Yamauchi, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; et al. MicroRNA profiling in gingival crevicular fluid of periodontitis—A pilot study. FEBS Open Bio 2017, 7, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafiero, C.; Spagnuolo, G.; Marenzi, G.; Martuscelli, R.; Colamaio, M.; Leuci, S. Predictive periodontitis: The most promising salivary biomarkers for early diagnosis of periodontitis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micó-Martínez, P.; Almiñana-Pastor, P.J.; Alpiste-Illueca, F.; López-Roldán, A. MicroRNAs and periodontal disease: A qualitative systematic review of human studies. J. Periodontal Implant. Sci. 2021, 51, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Zhou, X.; Naqvi, A.; Francis, M.; Foyle, D.; Nares, S.; Diekwisch, T.G.H. MicroRNAs and immunity in periodontal health and disease. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santonocito, S.; Polizzi, A.; Palazzo, G.; Isola, G. The Emerging Role of microRNA in Periodontitis: Pathophysiology, Clinical Potential and Future Molecular Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, E.; Mensah, A.; Rodgers, A.M.; McMullan, L.R.; Courtenay, A.J. The Role of Epigenetic and Biological Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Periodontal Disease: A Systematic Review Approach. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almiñana-Pastor, P.J.; Alpiste-Illueca, F.M.; Micó-Martinez, P.; García-Giménez, J.L.; García-López, E.; López-Roldán, A. MicroRNAs in Gingival Crevicular Fluid: An Observational Case-Control Study of Differential Expression in Periodontitis. Noncoding RNA 2023, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schünemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S. Diagnostic potential of miR-200 family members in gingival crevicular fluid for chronic periodontitis: Correlation with clinical parameters and therapeutic implications. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. MicroRNA-23a inhibits osteogenesis of periodontal mesenchymal stem cells by targeting bone morphogenetic protein signaling. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 102, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, E.; Sinjari, B.; Di Giovanni, P.; Aielli, L.; Caputi, S.; Muraro, R.; Murmura, G.; Reale, M. TNFα, IL-6, miR-103a-3p, miR-423-5p, miR-23a-3p, miR-15a-5p and miR-223-3p in the crevicular fluid of periodontopathic patients correlate with each other and at different stages of the disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandi, D.P.; Sudhakar, U.S.; Parthasarathy, H.; Rajamani, S.R.; Krishnaswamy, B. Extracellular microRNA-223-5p Levels in Plasma, Saliva, and Gingival Crevicular Fluid in Periodontal Disease as a Potential Diagnostic Marker—A Case-Control Analysis. J. Orofac. Sci. 2023, 15, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhong, Z. The expression and clinical significance of miR-30b-3p and miR-125b-1-3p in patients with periodontitis. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 325–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovas, A.; Puriene, A.; Snipaitiene, K.; Punceviciene, E.; Buragaite-Staponkiene, B.; Matuleviciute, R.; Butrimiene, I.; Jarmalaite, S. Gingival crevicular fluid microRNA associations with periodontitis. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 64, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Jia, L. MicroRNA-28-5p as a potential diagnostic biomarker for chronic periodontitis and its role in cell proliferation and inflammatory response. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Qi, Y.; Chen, H.; Shen, G. The expression and clinical significance of miR-1226 in patients with periodontitis. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micó-Martínez, P.; García-Giménez, J.; Seco-Cervera, M.; López-Roldán, A.; Almiñana-Pastor, P.; Alpiste-Illueca, F.; Pallardó, F. miR-1226 detection in GCF as potential biomarker of chronic periodontitis: A pilot study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2018, 23, e308–e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.C. Development of a Classification System for Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. Ann. Periodontol. 1999, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.C. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol. 2000 2004, 34, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawangpanyangkura, T.; Laohapand, P.; Boriboonhirunsarn, D.; Boriboonhirunsarn, C.; Bunpeng, N.; Tansriratanawong, K. Upregulation of microRNA-223 expression in gingival crevicular blood of women with gestational diabetes mellitus and periodontitis. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.; Romero, T.A.; Genkinger, J.M. Primary and Secondary Prevention of Pancreatic Cancer. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2019, 6, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y.; Matsui, S.; Kato, A.; Zhou, L.; Nakayama, Y.; Taka, H. MicroRNA expression in inflamed and noninflamed gingival tissues from Japanese patients. J. Oral Sci. 2014, 56, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalea, A.Z.; Hoteit, R.; Suvan, J.; Lovering, R.C.; Palmen, J.; Cooper, J.A.; Khodiyar, V.K.; Harrington, Z.; Humphries, S.E.; D’Aiuto, F. Upregulation of gingival tissue miR-200b in obese periodontitis subjects. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 59S–69S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzeldemir-Akcakanat, E.; Sunnetci-Akkoyunlu, D.; Balta-Uysal, V.; Özer, T.; Işik, E.B.; Cine, N. Differentially expressed miRNAs associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattari, M.; Taheri, R.A.; ArefNezhad, R.; Motedayyen, H. The expression levels of MicroRNA-146a, RANKL and OPG after non-surgical periodontal treatment. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öngöz Dede, F.; Gökmenoğlu, C.; Türkmen, E.; Bozkurt Doğan, Ş.; Ayhan, B.S.; Yildirim, K. Six miRNA expressions in the saliva of smokers and non-smokers with periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 2023, 58, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Li, N.; Wang, L. The Expression of miR-23a and miR-146a in the Saliva of Patients with Periodontitis and Its Clinical Significance. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9793809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, A.; Zhao, S.; Wan, L.; Liu, T.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Liao, Z.; Fang, H. MicroRNA expression profile of human periodontal ligament cells under the influence of Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Lang, G.P.; Chen, Z.L.; Wang, J.L.; Han, Y.Y. The Dual Role of Non-coding RNAs in the Development of Periodontitis. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2023, 36, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.M.; Jones, P.A. MicroRNAs: Critical mediators of differentiation, development and disease. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2009, 139, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoecklin-Wasmer, C.; Guarnieri, P.; Celenti, R.; Demmer, R.T.; Kebschull, M.; Papapanou, P.N. MicroRNAs and their target genes in gingival tissues. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomofuji, T.; Yoneda, T.; Machida, T.; Ekuni, D.; Azuma, T.; Kataoka, K.; Maruyama, T.; Morita, M. MicroRNAs as serum biomarkers for periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H. microRNAs in inflammatory alveolar bone defect: A review. J. Periodontal Res. 2021, 56, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, F.S. Receiver operating characteristic curve: Overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2022, 75, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).