Abstract

Periodontal disease is a complex and progressive chronic inflammatory condition that leads to the loss of alveolar bone and teeth. It has been associated with various systemic diseases, including diabetes mellitus and obesity, among others. Some of these conditions are part of the metabolic syndrome cluster, a group of interconnected systemic diseases that significantly raise the risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and stroke. The metabolic syndrome cluster encompasses central obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension. In this review, our objective is to investigate the correlation between periodontal disease and the components and outcomes of the metabolic syndrome cluster. By doing so, we aim to gain insights into the fundamental mechanisms that link each systemic condition with the metabolic syndrome. This deeper understanding of the interplay between these conditions and periodontal disease can pave the way for more effective treatments that take into account the broader impact of managing periodontal disease on the comprehensive treatment of systemic diseases, and vice versa.

1. Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by dysbiosis and a shift in the subgingival plaque towards Gram-negative microbiota, leading to the destruction of the tooth-supporting structures in a host-mediated manner [1,2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), periodontitis is a significant risk factor for tooth loss. It affects approximately 40% of individuals above 30 years old in the USA and around 60% of those above 65 years old [3]. Furthermore, periodontitis has been associated with various medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus [4]. Additionally, life-threatening medical conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome have been linked to periodontitis [5,6,7].

The major parameters used to define periodontitis include bleeding on probing (BOP), gingival index (GI), plaque index (PI), periodontal pocket depth (PD), and clinical attachment loss (CAL) [1].

The metabolic syndrome, also known as “Syndrome X”, is a cluster of conditions such as central obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension [6,8] that relate to one another, and together, they are known to increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [6]. Moreover, the syndrome was found to be associated with fatty liver [9] and obstructive sleep apnea [10]. The definition of the metabolic syndrome itself varies across different guidelines and associations. The definitions most commonly used are those written by the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF). The NCEP ATP III in 2001 released guidelines for diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome [11], and they were updated in 2005 [12,13]. It defined metabolic syndrome as occurring if three out of five of the following are present: abdominal obesity, measured by waist circumference ≥102 cm (40 in) in men and ≥88 cm (35 in) in females; serum triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or drug treatment for elevated triglycerides; serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol <40 mg/dL (1 mmol/L) in males and <50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) in females or drug treatment for low HDL cholesterol; blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg or drug treatment for elevated blood pressure; and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or drug treatment for elevated blood glucose. The last update of guidelines from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) was in 2006. The current guidelines recommend the diagnosis of an individual with metabolic syndrome if three of the following are present: increased waist circumference, normalized to different ethnic-specific waist circumference cut-points; triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or treatment for elevated triglycerides; HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) in males or <50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) in females or treatment for low HDL; systolic blood pressure ≥130, diastolic blood pressure ≥85, or treatment for hypertension; and FPG ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes. In the urban population in the USA, the IDF criteria found 15–20% more individuals with metabolic syndrome compared to the NCEP ATP III criteria. Overall, in determining the absence or presence of the metabolic syndrome, the two definitions overlapped in 93% of diagnoses [14].

In recent years, metabolic syndrome has been acknowledged as a major global epidemiological concern, with a reported prevalence of 17–32% in the general population [15]. The primary connection between periodontitis and other systemic diseases associated with the metabolic syndrome cluster, like diabetes [16], cardiovascular diseases [17], and obesity [18], appears to be the inflammatory burden. This review aims to explore the associations between periodontal disease and other systemic medical conditions related to metabolic syndrome, understand how treating one affects the other, and learn about the pathological mechanisms linking them.

This review provides a comprehensive, original, and thorough perspective on the relationship between periodontitis and individual components of the metabolic syndrome as well as the metabolic syndrome as a whole.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

Data were searched online from two databases: MEDLINE and Embase. The data were searched four times on 31 December 2021; 10 August 2022; 1 March 2023; and 28 July 2023.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The search was based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) publication restricted to English, (2) studies conducted on humans, and (3) studies that were published between the years 2010–2022. Furthermore, publications with no age and sex limit were included in this review. Some relevant key publications related to the different aspects of this review were manually added even though they were published before 2010.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

This review did not include publications that met the following criteria: (1) publications that were not focused on the association between periodontal disease and systemic diseases or (2) publications that did not meet these aims of the review, and (3) publications with fewer than 30 subjects.

2.4. Extraction of Publications from the Electronic Databases

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we used a structured search strategy defined by controlled vocabulary thesaurus terms, which are listed in Appendix A. Table 1 shows the publications extracted from the two databases based on the search strategy using these terms for each systemic disease and its association with periodontal disease.

Table 1.

Publications extracted from electronic databases using the search strategy and thesaurus terms.

2.5. Method for the Selection of Papers Extracted from the Databases

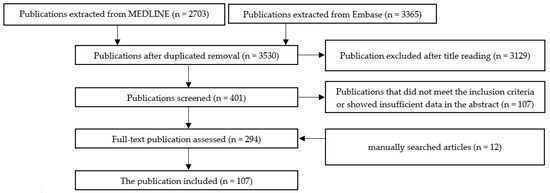

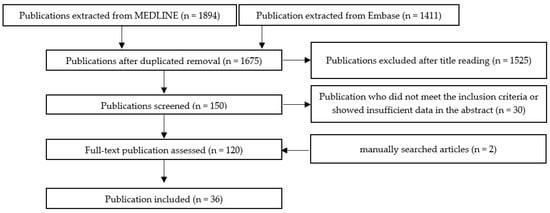

The method for selecting the papers extracted from the databases is shown in Scheme 1. In addition, individual schemes for each of the components of the metabolic syndrome cluster are shown in Appendix B (Scheme A1—metabolic syndrome, Scheme A2—obesity, Scheme A3—insulin resistance, Scheme A4—diabetes mellitus, Scheme A5—hyperlipidemia, and Scheme A6—hypertension).

Scheme 1.

The selection method for publications included in this review.

2.6. Method for the Selection of Papers Extracted from the Databases

The method for selecting the papers extracted from the databases is shown in Scheme 1 and Appendix B. After the first filtering of duplicates, a second selection was made by reading the titles. After the title, the abstract was read and quality assessment of the whole article were performed. In the end, the final articles were selected for writing this review. This review was conducted using the following research engines: Embase and PubMed. This review was limited to articles published between 2010 and 2022 with manually searched-for key publications, publications in English, and studies conducted on humans. To identify the paper, the keyword and free term included the following: “insulin resistance syndrome” OR “metabolic syndrome” OR “syndrome X” OR “insulin resistance syndrome” OR “Insulin Resistance” OR “Resistance, Insulin” OR “Insulin Sensitivity” OR “Sensitivity, Insulin” OR “resistance, insulin” OR “diabetes mellitus” OR “diabetes” OR “Hyperlipidemias” OR “Hyperlipemia” OR “Hyperlipemias” OR “Hyperlipidemia” OR “Lipidemia” OR “Lipidemias” OR “Lipemia” OR “Lipemias” OR “hyperlipaemia” OR “hyperlipemia” OR “hyperlipidaemia” OR “hyperlipidaemia type ii” OR “hyperlipidaemia type iii” OR “hyperlipidaemia type v” OR “hyperlipidaemias” OR “hyperlipidemic” OR “lipaemi” OR “lipemia” OR “lipidaemia” OR “obesity” OR “Abdominal obesity” OR “Blood Pressure, High” OR “Blood Pressures, High” OR “High Blood Pressure” OR “High Blood” OR “arterial hypertension” OR “cardiovascular hypertension” OR “HTN (hypertension)” OR “hypertensive disease” OR “systemic hypertension” AND periodontitis OR “periodontal disease”.

3. Results

3.1. The Epidemiological Association between Metabolic Syndrome and Periodontal Disease

Publications related to the association between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of included articles exploring the association between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease.

Metabolic syndrome includes conditions such as abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, insulin resistance, and changes in lipid metabolism [19].

Hlushchenko et al. reported that the prevalence of periodontal disease was 1.2 times higher in people with metabolic syndrome compared to healthy individuals within the age range of 25–55 years old [20]. When looking at the opposite direction, Gomes-Filho et al. found that people with moderate to severe periodontal disease were twice as likely as people without periodontal disease to have metabolic syndrome [21]. Pham et al. investigated the association between metabolic syndrome and the severity of periodontal disease and found that 21% of the individuals with metabolic syndrome had severe periodontitis compared to only 6.8% of the healthy individuals. The BOP, GI, PI, PD, and CAL were significantly higher in individuals with metabolic syndrome compared to healthy ones [22]. Furthermore, the study revealed that the severity of the periodontal disease correlated to the number of components of the metabolic syndrome. Individuals with zero to two components of the metabolic syndrome showed better periodontal parameters than those with three components, and those with four to five components presented the worst periodontal parameters among the study groups [22]. Similar results were found in a recent meta-analysis and systematic review, as the association between periodontal disease and the metabolic syndrome was found to be in a dose–response gradient; with more components of the metabolic syndrome, the association with periodontal disease was stronger [23]. Moreover, a recent clinical trial showed that periodontal treatment improved periodontal parameters in metabolic syndrome patients, but no improvement was found in metabolic parameters such as HbA1c, waist circumference, CRP levels, and more [24].

3.1.1. Underlying Mechanisms Linking Periodontal Disease to Metabolic Syndrome

Inflammatory Mechanisms

One of the underlying mechanisms linking periodontal disease to metabolic syndrome might be due to oxidative stress [25]. As both diseases have an inflammatory nature, pro-inflammatory cytokines originating from the gingiva infiltrate the bloodstream and increase oxidative stress. The higher oxidative stress may facilitate insulin resistance and atherosclerotic changes, and both may lead to the development of the metabolic syndrome. The connection is bidirectional, as inflammatory cytokines resulting from the metabolic syndrome components may increase the oxidative stress in the gingiva, thus Impairing the ability of the periodontium to respond to a bacterial challenge, which may result in an increased risk for periodontal disease [25].

Microbiological Mechanisms

Another plausible mechanism linking the two diseases might be microbial-related. It is known that obesity and type 2 diabetes can alter the oral microbiome, leading to microbial dysbiosis [26]. Subjects with periodontal disease who were obese differed dramatically from subjects with periodontal disease who were not obese in their oral microbiome composition. The obese patients had lower diversity in their oral microbiome, which may have increased the risk of developing periodontal disease [6].

3.2. The Epidemiological Association between Obesity and Periodontal Disease

Publications related to the association between obesity and periodontal disease are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of included articles exploring the association between obesity and periodontal disease.

Obesity is one of the most recognized medical conditions of the 21st century. In 2022, the WHO published a European regional report about obesity. According to this report, obesity causes about 1.2 million deaths annually in the European region. Moreover, the report stated that overweight and obesity, especially in adolescents and children, worsened after the COVID-19 pandemic [27]. Obesity is one of the fundamental characteristics of metabolic syndrome. It is usually measured by waist circumference or body mass index (BMI) (kilogram/meter2). An overweight adult will be considered as one with a circumference of >90 in women or >100 in men or with a BMI of 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and an obese adult will be considered as one with a circumference of >105 in women or >110 in men or with a BMI of ≥30.0 kg/m2 [28].

The association between obesity and periodontal disease was shown to be stronger when the BMI was higher [29]. Moreover, it was claimed that weight gain and obesity might be risk factors for developing periodontitis [30,31]. A recent meta-analysis showed that individuals who become overweight have an increased risk of 1.13 times for periodontal disease compared to healthy individuals, and obese individuals have a risk of 1.33 times for periodontal disease compared to healthy individuals [32]. A prospective study from South America revealed that women who were obese had a higher rate of CAL and an increased risk of 1.64 times for periodontal disease [33]. Moreover, individuals with higher BMI, especially above 30 kg/m2, showed worse periodontal parameters (CAL, BOP, PI, and PD) and a higher risk of the development of periodontitis. This was true across several years, study designs, and different races and nationalities [34]. BMI was also correlated with other components of the metabolic syndrome. As such, Fentoğlu and his group published that BMI was correlated with hyperlipidemic parameters and negatively correlated with PI, PD, BOP, and CAL [35]. Several studies suggested an association between periodontal disease and obesity, while the most prominent association was between young- and middle-aged females with high BMI and weight circumference to periodontal disease [36,37]. Another meta-analysis showed similar results, indicating that women with high BMI and high waist circumference had a higher association with periodontal disease, especially between the ages of 18 and 34. Moreover, the meta-analysis found that European individuals had a higher chance of developing periodontal disease [38].

3.2.1. Mechanisms

Inflammation

The associated mechanism between the two might be due to the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Pro-inflammatory cytokine production of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 was elevated by adipocytes and macrophages in the fat tissues of obese people [39]. These cytokines produce C-reactive protein, which in turn causes an acute inflammatory state [39]. TNF-α gained particular attention since this cytokine is known to play a fundamental role in periodontal disease, as it activates osteoclasts that facilitate bone resorption and periodontitis [18].

Oxidative Stress

Another plausible mechanism proposed that could link the two diseases is the fact that obesity elevates the production of ROS. Elevated ROS will result in the chronic activation of inflammatory mediators in the gingiva, such as the cytokines stated above. Gingival chronic inflammation will lead to alveolar bone destruction, deeper pockets, and higher CAL [18]. Interestingly, being obese does not interfere with the outcome of nonsurgical periodontal treatment [40,41,42].

Biochemical Pathways

Some studies found that obesity might interfere with the differentiation of osteoblasts. Adipocytes and osteoblasts share the same embryogenic origin: the pluripotent bone marrow stem cells (BMSC) [43]. It was reported that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway could drive BMSC toward osteoblasts, but this pathway is inhibited in obesity. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1, an inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, has been reported to be increased in mild obesity but falls in morbid obesity, resulting in increased marrow adipose [44].

Microbiology

Another approach to the connection between the two diseases may be bacterial. Obesity is known to alter the composition of the oral microbiota. One study found higher numbers of the periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia (T. forsythia) in the subgingival biofilms of overweight and obese individuals than in those from individuals of normal weight [45]. Moreover, it was found that obese people had elevated proportions of T. forsythia, Fusobacterium spp., and P. gingivalis in their saliva, regardless of whether they had a periodontal disease or a healthy periodontium [46,47]. Another study showed that people with chronic periodontitis had higher levels of perio-pathogens such as A. actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia (P. intermedia), T. forsythia, and Fusobacterium spp. [46].

3.3. The Epidemiological Association between Insulin Resistance and Periodontal Disease

Publications related to the association between insulin resistance and periodontal disease are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of included articles exploring the association between insulin resistance and periodontal disease.

Insulin resistance is a metabolic condition that is considered a prediabetic one. The condition is defined as a reduction in insulin, targeting the responsiveness of the tissues to physiological insulin levels and insulin resistance development, which leads to higher levels of glucose in the blood [48]. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L), diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, or drug treatment for elevated blood glucose comprise one of the defining criteria of the metabolic syndrome [11]. Insulin resistance has been linked before to other components of metabolic syndrome, such as central obesity and dyslipidemia [49]. Insulin resistance has been associated with periodontal disease. Individuals with a previous diagnosis of insulin resistance showed a significantly higher level of moderate to severe periodontal disease compared to healthy individuals [50]. Conversely, in individuals with a previous diagnosis of insulin resistance, the severity of periodontal disease was higher. The study measured insulin resistance measured by the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and showed that for every 1 mm of periodontal probing depth, the HOMA-IR score was elevated by 1.04 [51].

3.3.1. Mechanisms

Inflammation

An underlying mechanism associated with the connection between periodontal disease and insulin resistance might be an inflammatory one [51]. Insulin resistance is considered a low-level chronic inflammatory condition. It is known that in insulin resistance, there is an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [40,52]. Another inflammatory mediator that might be associated with the disease is reactive oxygen species (ROS) [53].

Microbiology

Besides an inflammatory approach, a bacterial one might link periodontal disease and insulin resistance. An in vitro study found that Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic cell lines [54].

The connection between insulin resistance and periodontal disease is thought to be a bidirectional one. Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease, so pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted in the gingiva enter the circulation and may worsen the existing insulin resistance and even cause it to develop into diabetes mellitus [48].

It is important to note that there is a substantial lack of quality studies on the connection between insulin resistance and periodontal disease. This might be because diabetes mellitus, which is the result of insulin resistance and one of the most linked systemic conditions to periodontal disease, gained most of the attention. Another explanation might be that it is hard to detect subjects in the prediabetic stage, and most of the population receives treatment after being diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.

3.4. The Epidemiological Association between Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease

Publications related to the association between diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of included articles exploring the association between diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder classified according to the etiology [55,56] as follows:

- Type 1 (T1DM).

- Type 2 (T2DM)—T2DM is the most common one, constituting 90% of the cases [55].

- Gestational diabetes (GDM).

DM is a major predisposing factor for periodontal disease. Demmer et al. reported that people with DM are about three times more likely to have periodontal disease compared to people who do not have it [57].

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and periodontitis: While T2DM is the most common, nonetheless, a correlation has been ascertained between periodontitis and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), which is less frequently encountered. T1DM is often characterized in young, healthy people. Individuals with T1DM tend to have more dental plaque and a higher incidence of chronic gingivitis, which may develop into periodontitis at younger ages [58]. Adolescents with T1DM were found to have a prevalence of periodontal disease that is about five times higher and a rapid, more pronounced periodontal breakdown [59]. Children had a higher incidence of gingivitis when they had T1DM [60,61], and children with T1DM had four times the prevalence of periodontal disease compared to healthy individuals [61,62]. Severe periodontal disease was more frequent in the poor metabolic control group than in the good metabolic control group and the controls (26.0% vs. 20.0% vs. 5.0%) [62]. The CAL was higher in adult diabetic individuals than in healthy ones by almost twofold (4.3 mm vs. 2.3 mm, respectively) [63]. Moreover, the CAL was greater in poor glycemic control individuals compared to those with good to fair glycemic control [61]. A recent review could not determine with high certainty whether periodontal therapy helps the glycemic control in T1DM patients. A total of 9 out of 10 eligible studies showed no effect of periodontal therapy on the glycemic control, while 1 did show an improvement. The authors of the review highlighted the need for high-quality, long-term studies in this field [64].

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and periodontitis: The connection between T2DM and periodontal disease has been well established before. Several studies showed that individuals with T2DM have a higher risk of developing periodontal disease (two- to threefold) compared to healthy individuals [57,65,66,67]. Moreover, previous works showed that individuals with T2DM show a more significant periodontal loss, higher CAL, and deeper periodontal pockets [55,68,69]. DM is known to affect the body in several ways.

3.4.1. Mechanisms

Oxidative Stress

First, DM leads to a constant hyperglycemic state. Hyperglycemia is known to worsen oxidative stress through several metabolic pathways, such as the polyol pathway [70], the hexosamine pathway [71], and the activation of protein kinase C (PKC) [72]. Second, pro-inflammatory cytokines, created mainly in adipose tissue, increase insulin resistance and are a significant cause of diabetes complications.

Moreover, the insulin resistance caused by DM is also known to elevate ROS levels, increase the number of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and reduce adiponectin. All of these changes increase the systemic inflammatory burden [48].

Inflammation

Another plausible mechanism linking the two diseases might be related to pro-inflammatory cytokines. Some pro-inflammatory cytokines have gained special attention, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 [71]. These cytokines are known to cause an elevated full-body inflammation state, which may result in bone loss and periodontal breakdown [48,71]. One of the key factors in treating DM is glycemic control. Previous studies showed that individuals with higher glycated hemoglobin (also known as hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c)) had an increased risk of periodontal disease [73,74,75]. The mechanism associated with the two diseases is probably a multifactorial one. The inflammation burden that both diseases cause has a bidirectional relationship that worsens each disease.

The inflammatory cytokines activate metalloproteinase (MMPs) [76]. Activated MMPs with ROS will result in collagen degradation and periodontal attachment loss [55]. Moreover, diabetes is also known to increase the RANKL/OPG ratio and promote osteoclastogenesis and activation, which in turn will lead to alveolar bone loss, deeper pockets, and periodontal disease [55]. Interestingly, in other dental procedures such as extraction, similar results were found. Three months after the extraction, salivary inflammatory markers such as OPG, the OPG/RANKL ratio, and total antioxidant capacity increased in both controls and diabetic patients, while IL-18, MMP-9, and RANKL decreased in both study groups, HGF was elevated only for the control group, and TNF-α showed a marked reduction in the diabetic group. Different statistical models showed that HbA1C was correlated with these inflammatory cytokines, especially OPG and RANKL [77].

The bidirectional relationship became clear when studies found that nonsurgical periodontal treatment benefits DM patients. Periodontal treatment reduced 3–4 mmol/mol (0.3–0.4%) of glycated hemoglobin after 3–4 months, but the supporting evidence that surgical root planning (SRP) may help with the glycemic control in T2DM is of low quality [78,79]. Conversely, a systematic review from 2022 showed that after 3–4 months, there was a reduction of 0.43% (4.7 mmol/mol); after 6 months, a reduction of 0.30% (3.3 mmol/mol); and after 12 months, a reduction of 0.50% (5.4 mmol/mol) of HbA1C in diabetic patients who were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and who went through subgingival instrumentation. Due to the new findings, the authors changed their opinion about the primary outcome of periodontal therapy and glycemic control and have now increased their level of certainty about the association [80]. It is also known that periodontal treatment might help with glycemic control in patients who are prediabetic or already diabetic [81]. Conversely, increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines caused by insulin resistance may reach the gingiva via systemic circulation, worsening preexisting periodontal disease [82]. Another study suggests that patients who are both diabetic and smokers who went through a complete periodontal treatment improved periodontal parameters as well as metabolic parameters such as HbA1C and fasting plasma glucose while improving inflammatory markers such as CRP. This study was conducted over a short time period (up to 6 months) [83].

Microbiology

Another factor that might link the diseases is a microbial one. It has been established by now that patients with DM have a reduction in the oral biological and phylogenetic diversity of the microbiome compared to normal subjects [84,85]. Moreover, similar changes were found within the subgingival microbiome. Subjects with DM had lower species diversity but higher numbers of periodontal pathogens than healthy individuals [84,86,87]. This means that while the periodontium may appear healthy, patients with DM have a higher predisposition to develop periodontal disease [86,87]. Another study, which compared healthy controls both to periodontal disease patients and to diabetic patients with periodontal disease, showed that patients with periodontal disease had higher numbers of perio-pathogens (mostly pathogenic from the red group), but patients with diabetes and periodontal disease had higher numbers of periodontal pathogens which connected with other pathogens (orange group). Although no major diversity was found within the phyla of the pathogens, the authors suggested that the connection between the periodontal pathogens is the cause for the rapid progression of periodontal disease in diabetic patients [88].

3.5. The Epidemiological Association between Hyperlipidemia and Periodontal Disease

Publications related to the association between hyperlipidemia and periodontal disease are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of included articles exploring the association between hyperlipidemia and periodontal disease.

Hyperlipidemia is defined as changes in the lipid accumulation in the blood, which mainly refers to elevated levels of triglycerides (TG), high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol [25]. Arreguin-Cano et al. found that subjects with periodontal disease had higher TG levels in their blood, lower HDL, and worse metabolic parameters [89]. Conversely, patients with hyperlipidemia showed worse periodontal parameters including BOP, CAL, and PD [90]. Another study showed that a previous diagnosis of hyperlipidemia negatively impacted individuals’ periodontal parameters in term of BOP, CAL, PD, and periodontal index (PI). Also, the study showed that plasma HDL levels were negatively correlated with CAL, but total cholesterol, LDL, and plasma triglycerides were significantly associated with BOP, CAL, PD, and PI [35].

3.5.1. Mechanisms

Microbiology

The mechanism linking hyperlipidemia and periodontal disease might be bacterial. Low HDL cholesterol was found to be associated with higher levels of serum antibodies against P. gingivalis, which is known to be a marked pathogen associated with periodontitis [91]. Moreover, higher LDL cholesterol levels were associated with higher serum antibodies against Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A.actinomycetemcomitans), and P. gingivalis [92].

Inflammation

Another plausible explanation for the link between the diseases is an inflammatory one. In an in vivo study, mice with metabolic syndrome induced by a high-fat diet showed markedly elevated osteoclastogenesis and alveolar bone loss [93]. Furthermore, there was a marked elevation in the expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein1, Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), and macrophage colony-stimulating factor), which led to further osteoclastogenesis and alveolar bone loss [93]. The mechanism hypothesized was that systemic inflammation caused an increased biosynthesis of cholesterol, which is secondary to bacteremia, and systemic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) caused by periodontal disease. Moreover, periodontal therapy combined with antihyperlipidemic therapy showed promising results in lowering serum pro-inflammatory cytokines [94].

3.6. The Epidemiological Association between Hypertension and Periodontal Disease

Publications related to the association between hypertension and periodontal disease are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of included articles exploring the association between hypertension and periodontal disease.

Hypertension is the most common cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is defined by a systolic blood pressure higher than 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure higher than 90 mmHg [95]. The WHO reported in 2014 that hypertension is responsible for 51% of deaths from stroke and 45% of overall CVD mortality in all ages and ethnic groups [96]. Hypertension has a long-term effect on the heart. As of 2015, the Global Burden of Disease Committee marked it as one of the causes of hypertensive heart failure and, ultimately, heart failure [97]. Hypertension is considered fundamental in establishing metabolic syndrome. One study showed that the prevalence of hypertension was correlated to periodontal disease severity [98]. Another cohort study showed that hypertension was positively associated with periodontal disease. Moreover, it showed that individuals in a hypertensive state were more susceptible to developing periodontal disease compared to prehypertension individuals and individuals with normal blood pressure [99]. A recent meta-analysis found that individuals with periodontal disease have a higher prevalence of hypertension [100]. Another cross-sectional study showed that the odds for arterial hypertension were higher in individuals with periodontal disease. Moreover, it showed that the odds became higher as the severity of the periodontal disease worsened [101].

3.6.1. Mechanisms

Inflammation

The association between periodontal disease and hypertension is believed to be related to the inflammatory nature of the two diseases [5]. Oral pathogens may invade the bloodstream through the periodontal pockets and release toxins, resulting in endothelial inflammation. Endothelial inflammation is known to be the first stage in many CVDs and atherosclerosis, specifically, which may later develop into hypertension [102]. Bacteria infiltrating through the periodontal pockets and their endotoxins can draw inflammatory cells to the arterial endothelium and vascular smooth muscle, causing the initiation of the coagulation process [102].

Microbiology

Perio-pathogens are known to cause chronic endothelial inflammation, leading to vasospasm and potential thromboses [102]. This process may be enhanced by the inflammatory cytokines coming from the periodontium with constant low-grade inflammation [102]. The cytokines cause the endothelium to produce vasoconstrictors, promoting the aggregation and adhesion of leukocytes, possibly leading to thromboses [102]. A recent study showed that hypertensive patients had higher levels of perio-pathogens (especially P. intermedia, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum) compared to normotensive patients [103].

Only a few studies have focused on periodontal treatment and its effects on blood pressure and hypertension [104,105,106]. However, studies did show that following periodontal treatment, there was a reduction of 12.5 mmHg in systolic blood pressure and 10 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure [104]. Moreover, six months after periodontal treatment, a reduction in CRP and IL-6 levels was observed, as well as a reduction in the left ventricular mass of 12.9 g [104]. Another systematic review from the Cochrane database found that patients diagnosed with periodontal disease and CVDs (not including hypertension) experienced no beneficial effect on blood pressure after periodontal treatment [106]. Moreover, the systematic review did not find added value of intensive periodontal treatment compared to supragingival scaling only [106]. Lastly, the periodontal treatment showed promising results in patients diagnosed with periodontitis and hypertension. Periodontal treatment caused a reduction in the short term of 11.20 mmHg in systolic blood pressure and 8.40 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients with periodontal disease [106]. It should be noted that the beneficial effect of periodontal therapy had only a short-term effect, while in the long term, no effect on blood pressure was found [106]. These studies suggest an association between periodontal disease and hypertension, suggesting the consideration of periodontal treatment as part of hypertensive therapy in patients with periodontal disease [107].

4. Discussion

Periodontal disease affects most of the adult population worldwide [3,98]. It is considered a multifactorial disease and is associated with other systemic diseases. Most of the strong association between periodontitis and other systemic diseases is connected to the cluster known as metabolic syndrome. This cluster includes obesity, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension [6]. It is important to mention that the etiology of both diseases is considered multifactorial, and several association mechanisms have been proposed between the two. The mechanism linking metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease is thought to be related to the fact that both diseases are caused by inflammatory reactions, inflammatory cytokines, and elevated systemic oxidative stress [25]. As depicted in this review, in insulin resistance, there is an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [40,52] and ROS [53]. Furthermore, in T2DM there is an increase in TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 [71], which are known to elevate HbA1C, which increases the risk for periodontal disease [73,74,75]. Moreover, the inflammatory state is known to activate MMP, which, together with ROS, will result in periodontal breakdown [76]. Also, T2DM is known to alter the RANKL/OPG ratio, which may lead to the loss of alveolar bone [55]. An in vivo study showed that a high-fat diet will result in osteoclastogenesis, elevated levels of RANKL, and alveolar bone loss [93]. Moreover, in the study, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL6, MCSF, and MCP-1 will further lead to alveolar bone loss [93]. In obese individuals, elevated levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 were found [39]. These cytokines will produce C-reactive protein, which in turn will cause an acute inflammatory state [39]. Moreover, in obese individuals, higher ROS will lead to a higher inflammatory state and periodontal breakdown [18].

Other suggestions for the associated mechanism between the two include a bacterial one. An in vitro study found that Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic cell lines [54]. Moreover, a reduction in biological and phylogenetic diversity of the oral microbiome with higher perio-pathogens was found in T2DM patients [84,85,86,87]. In individuals with low HDL cholesterol, there were higher levels of serum antibodies against P. gingivalis compared to healthy individuals [91]. Moreover, higher LDL cholesterol levels were associated with higher serum antibodies against Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A.actinomycetemcomitans) and P. gingivalis [92]. Similarly, one study found higher numbers of Tannerella forsythia (T. forsythia) in the subgingival biofilms of overweight and obese individuals than in those from individuals of normal weight [45]. Higher levels of perio-pathogens were found in obese people [46,47]. Also, perio-pathogens are known to cause chronic endothelial inflammation, leading to vasospasm and potential thromboses [102]. This process may be enhanced by the inflammatory cytokines coming from the periodontium, leading the endothelium to produce vasoconstrictors, promoting the aggregation and adhesion of leukocytes, and possibly leading to thromboses [102]. Taken together, the suggested mechanism accounting for the association between periodontal disease and each of the components of the metabolic syndrome cluster was similar: an increased inflammatory burden through inflammatory cytokines (mostly IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) which results in systemic elevated oxidative stress and the invasion of Gram-negative bacteria, which further increase the inflammatory burden and the activation of bone-resorbing agents. The bacterial and inflammatory burden from the periodontal tissue worsens the initial phase of the components of the metabolic syndrome cluster, exacerbating each component and the cluster itself [6,20,21,24,25,26,27,28,46,51,60,61,62,63].

This review aims to give a broader view of the association between periodontal disease and the components of metabolic syndrome. Here, we reviewed the association between periodontal disease and each of the metabolic syndrome cluster components and the metabolic syndrome itself. We suggest seeing the association in a broader view, as each component affects the others and increases the risk for periodontal disease. Based on this review, we also suggest that part of the treatment for the metabolic syndrome or any of its components should include a periodontal examination, as the relationship is bidirectional. Moreover, the periodontal treatment in patients with a previous diagnosis of any of the components of the metabolic syndrome should consider looking for other systemic diseases, especially other components of the metabolic syndrome, and therefore consider the treatment possibilities while considering the possible association with the metabolic syndrome.

5. Conclusions

Metabolic syndrome is positively associated with periodontal disease.

The associated mechanisms between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome components were increased pro-inflammatory mediators (including different cytokines, ROS, and elevated CRP) and constant penetration of periodontal pathogenic bacteria into the bloodstream.

Periodontal status should be checked as part of the metabolic syndrome treatment, as it significantly impacts the initiation and progression of the metabolic syndrome and its components.

Future research directions should address the gap in the literature and focus on conducting multicenter longitudinal studies in different ethnic populations to study the association of periodontal disease and its treatment with each of the metabolic syndrome components and the metabolic syndrome as a whole.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because this is a review article.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Data Search Strategy

MEDLINE (PubMed)

#1: “periodontitis” OR “periodontal disease”.

#2: “insulin resistance syndrome” OR “metabolic syndrome” OR “syndrome X” OR “insulin resistance syndrome”.

#3: “Insulin Resistance” OR “Resistance, Insulin” OR “Insulin Sensitivity” OR “Sensitivity, Insulin”.

#4: “diabetes mellitus” OR “diabetes”.

#5: “Hyperlipidemias” OR “Hyperlipemia” OR “Hyperlipemias” OR “Hyperlipidemia” OR “Lipidemia” OR “Lipidemias” OR “Lipemia” OR “Lipemias”.

#6: “obesity” OR “Abdominal obesity”.

#7: “Blood Pressure, High” OR “Blood Pressures, High” OR “High Blood Pressure” OR “High Blood Pressures” OR “hypertension”.

#1 AND #2; #1 AND #3; #1 AND #4; #1 AND #5; #1 AND #6; #1 AND #7.

EMBASE

#1: “periodontitis” OR “periodontal disease”.

#2: “insulin resistance syndrome” OR “metabolic syndrome” OR “syndrome X”.

#3: “Insulin Resistance” OR “resistance, insulin”.

#4: “diabetes mellitus” OR “diabetes”.

#5: “hyperlipaemia” OR “hyperlipemia” OR “hyperlipidaemia” OR “hyperlipidaemia type ii” OR “hyperlipidaemia type iii” OR “hyperlipidaemia type v” OR “hyperlipidaemias” OR “hyperlipidemic” OR “lipaemia” OR “lipemia” OR “lipidaemia”.

#6: “obesity” OR “Abdominal obesity”.

#7: “arterial hypertension” OR “blood pressure, high” OR “cardiovascular hypertension” OR “high blood pressure” OR “HTN (hypertension)” OR “hypertensive disease” OR “systemic hypertension”.

#1 AND #2; #1 AND #3; #1 AND #4; #1 AND #5; #1 AND #6; #1 AND #7.

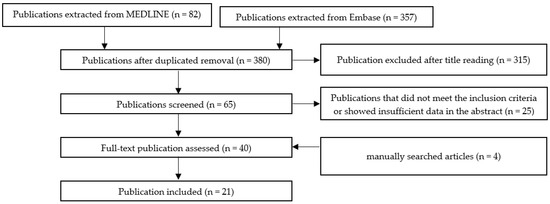

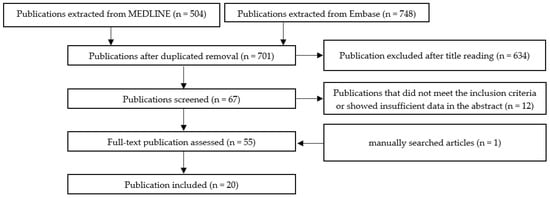

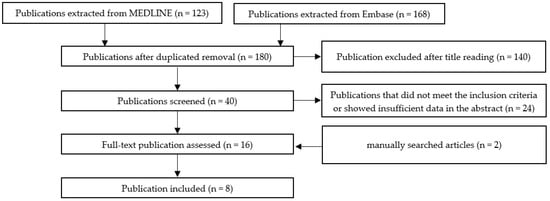

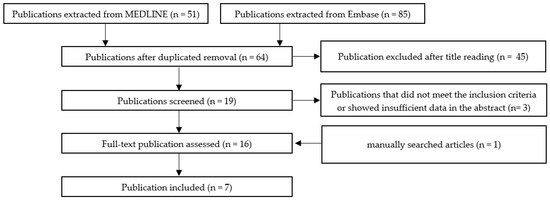

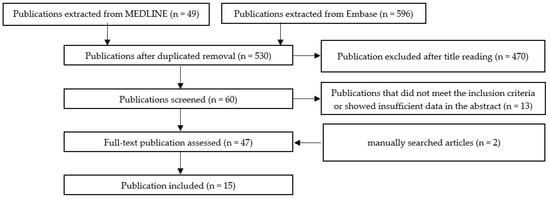

Appendix B. The Selection Method for Publications

Scheme A1, Scheme A2, Scheme A3, Scheme A4, Scheme A5 and Scheme A6 show the selection methods for publications for each systemic condition analyzed with periodontitis: metabolic syndrome (Scheme A1), obesity (Scheme A2) insulin resistance (Scheme A3), diabetes mellitus (Scheme A4), hyperlipidemia (Scheme A5), and hypertension (Scheme A6). After the first filtering of duplicates, a second selection was conducted by reading the titles. After the title, the abstract was read, and quality assessment of the whole article was performed. In the end, the final articles were selected for writing this review.

Scheme A1.

The selection method for publication assessing the association between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome.

Scheme A2.

The selection method for publication assessing the association between periodontal disease and obesity.

Scheme A3.

The selection method for publications assessing the association between periodontal disease and insulin resistance.

Scheme A4.

The selection method for publications assessing the association between periodontal disease and Diabetes mellitus.

Scheme A5.

The selection method for publication assessing the association between periodontal disease and hyperlipidemia.

Scheme A6.

The selection method for publication assessing the association between periodontal disease and hypertension.

Appendix C. Figures Illustrate the Underlying Mechanisms Involved in the Association between Metabolic Syndrome and Periodontal Disease

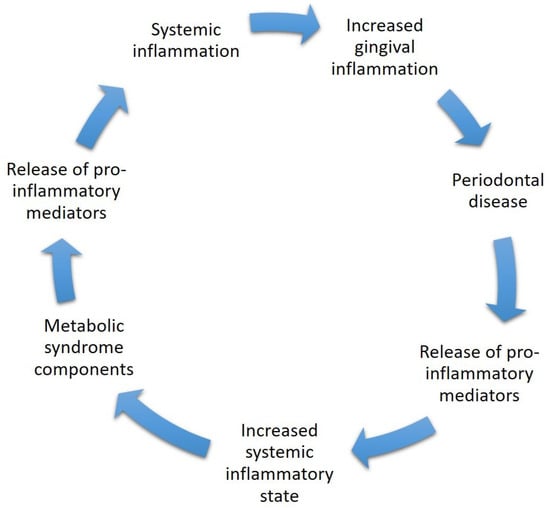

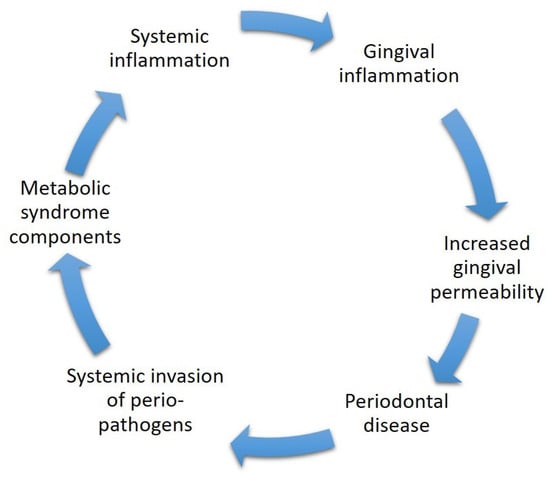

Figure A1.

The mechanism of inflammation, including systemic inflammation, which in turn may lead to gingival inflammation and later on to periodontal disease. The gingival inflammatory state releases pro-inflammatory mediators (mainly cytokines and ROS) to the general bloodstream, which later on may cause a systemic inflammatory state which may initiate or worsen already established components of the metabolic syndrome. The components are known to increase the inflammatory state of the body by releasing pro-inflammatory mediators which in turn may cause gingival inflammation.

Figure A2.

The mechanism of microbiology includes systemic inflammation caused by metabolic syndrome components which in turn may lead to gingival inflammation. The gingival inflammation causes the gingiva to become more permeable, which may later end in periodontal disease. In periodontal disease, there is an increase in perio-pathogens which may invade systemically through the bloodstream, which may initiate or worsen already established components of the metabolic syndrome. The components are known to increase the inflammatory state of the body by releasing pro-inflammatory mediators which in turn may cause gingival inflammation.

References

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S162–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, B.W.; Weston, S.J. Association between Chronic Periodontal Disease and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 1708–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, P.I.; Wei, L.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Thornton-Evans, G.; Zhang, X.; Lu, H.; McGuire, L.C.; Genco, R.J. Periodontitis prevalence in adults ≥ 65 years of age, in the USA. Periodontology 2000 2016, 72, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winning, L.; Patterson, C.C.; Neville, C.E.; Kee, F.; Linden, G.J. Periodontitis and incident type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Van Dyke, T.E. Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAPWorkshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, S24–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirih, F.Q.; Monajemzadeh, S.; Singh, N.; Sinacola, R.S.; Shin, J.M.; Chen, T.; Fenno, J.C.; Kamarajan, P.; Rickard, A.H.; Travan, S.; et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: The role of lipids, inflammatory cytokines, altered host response, and the microbiome. Periodontology 2000 2021, 87, 50–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobin, R.; Tian, D.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J. Periodontal Diseases and the Risk of Metabolic Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 1035–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Cho, Y.D. Periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome: A qualitative critical review of their association. Arch. Oral Biol. 2014, 59, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, M.; Naka, S.; Nakano, K.; Wada, K.; Endo, H.; Mawatari, H.; Imajo, K.; Nomura, R.; Hokamura, K.; Ono, M.; et al. Involvement of a periodontal pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis on the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-I.; Choi, C.-H.; Chung, K.-H. No Association between Metabolic Syndrome and Periodontitis in Korean Postmenopausal Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001, 285, 2486–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuth, S.; Alberti, K.G.; Bennett, P.; Buse, J.; Defronzo, R.; Kahn, R.; Kitzmiller, J.; Knowler, W.C.; Lebovitz, H.; Lernmark, A.; et al. Follow-up Report on the Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 3160–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005, 112, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; Appleton, S.; Wilson, D.H.; Taylor, A.W.; Dal Grande, E.; Chittleborough, C.; Gill, T.; Ruffin, R. Population Comparison of Two Clinical Approaches to the Metabolic Syndrome: Implications of the New International Diabetes Federation Consensus Definition. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 2777–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nibali, L.; Tatarakis, N.; Needleman, I.; Tu, Y.-K.; D’Aiuto, F.; Rizzo, M.; Donos, N. Association between Metabolic Syndrome and Periodontitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.M.; Miranda, T.S.; Lima, J.A.; Dias Gonçalves, T.E.; Santos, V.R.; Bastos, M.F.; Ribeiro, F.V. Expression of Immune-Inflammatory Markers in Sites of Chronic Periodontitis in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, O.; Arora, P.; Mayer, M.; Chatterjee, S. Inflammation in Periodontal Disease: Possible Link to Vascular Disease. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 609614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, R.; Ka, K.; Huang, T.; Khalili, S.; Nguyen, B.H.; Nicolau, B.; Tran, S.D. Tumor Necrosis Factor-αand Interleukin-6: Potential Interorgan Inflammatory Mediators Contributing to Destructive Periodontal Disease in Obesity or Metabolic Syndrome. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 728987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoznino, G.; Zini, A.; Kedem, R.; Protter, N.E.; Zur, D.; Abramovitz, I. Hypertension and Its Associations with Dental Status: Data from the Dental, Oral, Medical Epidemiological (DOME) Nationwide Records-Based Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlushchenko, A.; Batig, V.M.; Borysenko, V.; Tokar, O.M.; Batih, V.; Vynogradova, O.M.; Boychuk-Tovsta, O.G. Prevalence and Intensity of Periodontal Disease in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome. J. Med. Life 2020, 13, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Filho, I.S.; Balinha, I.d.S.C.E.; da Cruz, S.S.; Trindade, S.C.; Cerqueira, E.d.M.M.; Passos-Soares, J.d.S.; Coelho, J.M.F.; Ladeia, A.M.T.; Vianna, M.I.P.; Hintz, A.M.; et al. Moderate and severe periodontitis are positively associated with metabolic syndrome. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 25, 3719–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T. The association between periodontal disease severity and metabolic syndrome in Vietnamese patients. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 16, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.R.; Martins, C.C.; Faria, S.F.S.; Carvalho, A.P.; Pereira, A.G.; Costa, F.O.; Cota, L.O.M. Association between components of metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5557–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanesi, F.C.; Greggianin, B.F.; dos Santos, G.O.; Toniazzo, M.P.; Weidlich, P.; Gerchman, F.; Oppermann, R.V. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycated haemoglobin and metabolic syndrome parameters: A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 50, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamster, I.B.; Pagan, M. Periodontal disease and the metabolic syndrome. Int. Dent. J. 2020, 67, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.; Hoffmann, T.; Fischer, S.; Bornstein, S.; Gräßler, J.; Noack, B. Obesity alters composition and diversity of the oral microbiota in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus independently of glycemic control. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/353747 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Ross, R.; Neeland, I.J.; Yamashita, S.; Shai, I.; Seidell, J.; Magni, P.; Santos, R.D.; Arsenault, B.; Cuevas, A.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: A Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataro, A.L.; Costa, F.O.; Cortelli, S.C.; Cortelli, J.R.; Abreu, M.H.N.G.; Costa, J.E. Association between severity of body mass index and periodontal condition in women. Clin. Oral Investig. 2011, 16, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekuni, D.; Mizutani, S.; Kojima, A.; Tomofuji, T.; Irie, K.; Azuma, T.; Yoneda, T.; Furuta, M.; Eshima, N.; Iwasaki, Y.; et al. Relationship between increases in BMI and changes in periodontal status: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, A.; Kaye, E.K.; Apovian, C.; Fung, T.T.; Nunn, M.; Garcia, R.I. Overweight and obesity predict time to periodontal disease progression in men. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 39, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.G.; Leite, F.R.; Do, L.G.; Peres, K.G.; Correa, M.B.; Demarco, F.F.; Peres, M.A. Is weight gain associated with the incidence of periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaio, E.J.; Haas, A.N.; Rösing, C.K.; Oppermann, R.V.; Albandar, J.M.; Susin, C. Effect of obesity on periodontal attachment loss progression: A 5-year population-based prospective study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Shimazaki, Y. Metabolic disorders related to obesity and periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000 2007, 43, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentoğlu, Ö.G.; Taşdelen, P.; Uskun, E.; Aykaç, Y.; Bozkurt, F.Y. Periodontal Status in Subjects with Hyperlipidemia. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Shawish, G.; Betsy, J.; Anil, S. Is Obesity a Risk Factor for Periodontal Disease in Adults? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, D.O.; Gomes-Filho, I.S.; da Cruz, S.S.; Trindade, S.C.; Santos, K.O.B.; Sarmento, V.A.; Bet Freitas, T.O.; dos Santos, H.L.R.; Hintz, A.M.; Santos, P.N.P.; et al. Obesity in young women is positively associated with periodontitis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 6139–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.M.; Lee, S.; Hwang, W.; Son, E.; Kim, T.W.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.H. Obesity and periodontitis: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 999455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Herrera, M.; Silvestre-Rangil, J.; Silvestre, F.J. Association between obesity and periodontal disease. A systematic review of epidemiological studies and controlled clinical trials. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2017, 22, e708–e715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, U.; Gürgan, C.A.; Ağbaht, K. Changes in Inflammatory and Metabolic Parameters After Periodontal Treatment in Patients with and without Obesity. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duzagac, E.; Cifcibasi, E.; Erdem, M.G.; Karabey, V.; Kasali, K.; Badur, S.; Cintan, S. Is obesity associated with healing after non-surgical periodontal therapy? A local vs. systemic evaluation. J. Periodontal Res. 2015, 51, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, U.; Dede, F.O.; Dogan, S.B.; Gulsoy, Z.; Sertoglu, E. Chemerin and interleukin-6 levels in obese individuals following periodontal treatment. Oral Dis. 2016, 22, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, J.; Begun, D.; Westendorf, J.; McGee-Lawrence, M. Defining osteoblast and adipocyte lineages in the bone marrow. Bone 2018, 118, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagathu, C.; Christodoulides, C.; Tan, C.Y.; Virtue, S.; Laudes, M.; Campbell, M.; Ishikawa, K.; Ortega, F.; Tinahones, F.J.; Fernández-Real, J.-M.; et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 regulates adipose tissue expansion and is dysregulated in severe obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rawi, N.; Al-Marzooq, F. The Relation between Periodontopathogenic Bacterial Levels and Resistin in the Saliva of Obese Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 2643079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, S.S.; Feres, M.; Gonçalves, T.E.D.; Zimmermann, G.S.; Da Silva, H.D.P.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Duarte, P.M. Does obesity influence the subgingival microbiota composition in periodontal health and disease? J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, D.R.; Silva, P.A.; Colombo, A.P.V.; Silva-Boghossian, C.M. Subgingival microbiota in overweight and obese young adults with no destructive periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 2021, 92, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, A.N. Periodontitis and Insulin Resistance: Casual or Causal Relationship? Diabetes Metab. J. 2012, 36, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.K.; Hevener, A.L.; Barnard, R.J. Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance: Underlying Causes and Modification by Exercise Training. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguigui, C.; Bongard, V.; Ruidavets, J.-B.; Chamontin, B.; Sixou, M.; Ferrières, J.; Amar, J. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and periodontitis: A cross-sectional study in a middle-aged French population. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmer, R.T.; Squillaro, A.; Papapanou, P.N.; Rosenbaum, M.; Friedewald, W.T.; Jacobs, D.R.; Desvarieux, M. Periodontal Infection, Systemic Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance: Results from the Continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2235–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Raya, A.; Abou-Raya, S.; AbuElKheir, H. Periodontal Disease, Systemic Inflammation and Adipocytokines: Effect of Periodontal Therapy on Glycaemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) Patients. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2010, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, E.; Monaco, A.; Procaccini, L.; Mummolo, S.; Gatto, R.; Tetè, S.; Baldini, A.; Tecco, S.; Marzo, G. Periodontal disease: The influence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, U.G.; Ilievski, V.; Unterman, T.G.; Watanabe, K. Porphyromonas gingivalis Lipopolysaccharide Upregulates Insulin Secretion from Pancreatic β Cell Line MIN6. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrato, C.A.; Tárzia, O.; Jovanovič, L.; Chinellato, L.E.M. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2013, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri-Obradors, E.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Jane-Salas, E.; Vinas, M.; Lopez-Lopez, J. Oral manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus. A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2017, 22, e586–e594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziukaite, L.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, F.A. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in people clinically diagnosed with periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Gastaldi, G.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Mombelli, A.; Giannopoulou, C. Periodontal health in a cohort of subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2019, 5, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapone, B.; Ferrara, E.; Corsalini, M.; Converti, I.; Grassi, F.R.; Santacroce, L.; Topi, S.; Gnoni, A.; Scacco, S.; Scarano, A.; et al. The Effect of Gaseous Ozone Therapy in Conjunction with Periodontal Treatment on Glycated Hemoglobin Level in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Unmasked Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotna, M.; Podzimek, S.; Broukal, Z.; Lencova, E.; Duskova, J. Periodontal Diseases and Dental Caries in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 379626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, D.T.; Ding, Z.; Yang, Y. The impact of diabetes on periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 2019, 82, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popławska-Kita, A.; Siewko, K.; Szpak, P.; Król, B.; Telejko, B.; Klimiuk, P.A.; Stokowska, W.; Górska, M.; Szelachowska, M. Association between type 1 diabetes and periodontal health. Adv. Med. Sci. 2014, 59, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenawat, A.; Punn, K.; Srivastava, V.; Meenawat, A.S.; Dolas, R.; Govila, V. Periodontal disease and type I diabetes mellitus: Associations with glycemic control and complications. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2013, 17, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.; Gopalkrishna, P. Type 1 diabetes and periodontal disease: A literature review. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 56, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, R.S.; Marlow, N.M.; Fernandes, J.K.; Hermayer, K. Oral Health and Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 345, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liccardo, D.; Cannavo, A.; Spagnuolo, G.; Ferrara, N.; Cittadini, A.; Rengo, C.; Rengo, G. Periodontal Disease: A Risk Factor for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Bissett, S.M. Periodontitis and diabetes. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Alba, A.L.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Konstantinidis, A.; Makrilakis, K.; Taylor, R. Periodontitis and diabetes: A two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Mizutani, K.; Minami, I.; Kido, D.; Mikami, R.; Konuma, K.; Saito, N.; Kominato, H.; Takemura, S.; Nakagawa, K.; et al. Association of periodontal pocket area with type 2 diabetes and obesity: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e002139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacco, F.; Brownlee, M. Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Complications. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Xiao, E.; Graves, D.T. Diabetes mellitus related bone metabolism and periodontal disease. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2015, 7, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.-J. Pathogenesis of Chronic Hyperglycemia: From Reductive Stress to Oxidative Stress. J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 137919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lin, K.-D.; Lee, M.-Y.; Lee, Y.-L.; Yu, C.-K.; Kabasawa, Y.; Huang, H.-L. Clinical Outcomes and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life after Periodontal Treatment with Community Health Worker Strategy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, C.; Ramalingam, S.; Mohan, V.; Pradeepa, R.; Ramakrishnan, M.J. Periodontal therapy as an adjunctive modality for HbA1c reduction in type-2 diabetic patients. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamash, M.; Klinge, B.; Engström, P.-E. Periodontal treatment and HbA1c levels in subjects with diabetes mellitus. J. Oral Rehabil. 2015, 43, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arreguin-Cano, J.A.; Ayerdi-Nájera, B.; Tacuba-Saavedra, A.; Navarro-Tito, N.; Dávalos-Martínez, A.; Emigdio-Vargas, A.; Barrera-Rodríguez, E.; Blanco-García, N.; Gutiérrez-Venegas, G.; Ventura-Molina, E.; et al. MMP-2 salivary activity in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, G.-A.; Martu, M.-A.; Martu, M.-C.; Popescu, D.; Surlin, P.; Tatarciuc, D.; Popa, C.; Foia, L.-G. Correlations between Salivary Immuno-Biochemical Markers and HbA1c in Type 2 Diabetes Subjects before and after Dental Extraction. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, T.C.; Weldon, J.C.; Worthington, H.V.; Needleman, I.; Wild, S.H.; Moles, D.R.; Stevenson, B.; Furness, S.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2018, CD004714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madianos, P.N.; Koromantzos, P.A. An update of the evidence on the potential impact of periodontal therapy on diabetes outcomes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 45, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, T.C.; Clarkson, J.E.; Worthington, H.V.; MacDonald, L.; Weldon, J.C.; Needleman, I.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Wild, S.H.; Qureshi, A.; Walker, A.; et al. Treatment of periodontitis for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD004714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandni, R.; Mammen, J.; Joseraj, M.G.; Joseph, R. Effect of Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy on Insulin Resistance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Chronic Periodontitis. Diabetes 2015, 64, A692. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, S.N.; Reichert, C.; Jäger, A.; Deschner, J. Effect of overweight/obesity on response to periodontal treatment: Systematic review and a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.A.V.; Nguyen, P.A.; Tran, T.T.P.; Nguyen, V.T.T. Nonsurgical periodontal treatment improved the type 2 diabetes mellitus status in smokers: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 194, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ding, W.; Sun, X.; He, K.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, X. Changes of saliva microbiota in the onset and after the treatment of diabetes in patients with periodontitis. Aging 2020, 12, 13090–13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeb, A.T.; Al-Rubeaan, K.A.; Aldosary, K.; Raja, G.U.; Mani, B.; Abouelhoda, M.; Tayeb, H.T. Relative reduction of biological and phylogenetic diversity of the oral microbiota of diabetes and pre-diabetes patients. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 128, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Lux, R.; Klokkevold, P.; Chang, M.; Barnard, E.; Haake, S.; Li, H. The subgingival microbiome associated with periodontitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. ISME J. 2019, 14, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, S.M.; Joshi, V.; Fellows, M.; Dabdoub, S.M.; Nagaraja, H.N.; O’Donnell, B.; Deshpande, N.R.; Kumar, P.S. A tale of two risks: Smoking, diabetes and the subgingival microbiome. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2075–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Song, J.-M.; Kang, J.; Lee, H.; Park, H.R.; Kim, Y.H. Differential microbiota network in gingival tissues between periodontitis and periodontitis with diabetes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1061125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-K.; D’Aiuto, F.; Lin, H.-J.; Chen, Y.-W.; Chien, K.-L. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and diagnoses of periodontal diseases among participants in a large Taiwanese cohort. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, V.A.; Desai, M.H.; Shivakumar, T. Periodontal Status in Subjects with Hyperlipidemia and Determination of Association between Hyperlipidemia and Periodontal Health: A Clinicobiochemical Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2013, 14, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Minagawa, K.; Sato, M.; Kaneko, N.; Imai, S.; Yoshihara, A.; Miyazaki, H. Serum antibody to Porphyromonas gingivalisin metabolic syndrome among an older Japanese population. Gerodontology 2014, 33, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, A.; Lafaurie, G.I.; Millán, L.V.; Ardila, C.M.; Duque, A.; Novoa, C.; López, D.; Contreras, A. Association between periodontal disease and plasma levels of cholesterol and triglycerides. Colomb. Medica 2013, 44, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Kirkwood, K.; Lopes-Virella, M.; Huang, Y. Metabolic Syndrome Exacerbates Inflammation and Bone Loss in Periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 94, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentoğlu, Ö.Z.; Kırzıoğlu, F.Y.; Özdem, M.U.; Koçak, H.A.; Sütçü, R.E.; Sert, T.U. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in hyperlipidemic patients with periodontitis after periodontal treatment. Oral Dis. 2011, 18, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; De Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 1953–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancia, G.; Fagard, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Redon, J.; Zanchetti, A.; Böhm, M.; Christiaens, T.; Cifkova, R.; De Backer, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Blood Press. 2013, 22, 193–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.; Abajobir, A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abera, S.F.; Abyu, G.; Ahmed, M.; Aksut, B.; Alam, T.; Alam, K.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, I.; Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Rua, J.; Delgado, A.S.; Mendes, J.J. Association between hypertension and chronic periodontitis in a Portuguese population. Ann. Med. 2019, 51, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Ekuni, D.; Miyai, H.; Kataoka, K.; Yamane, M.; Mizutani, S.; Irie, K.; Azuma, T.; Tomofuji, T.; Iwasaki, Y.; et al. Relationship between Prehypertension/Hypertension and Periodontal Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2015, 29, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, E.M.; Suvan, J.; Buti, J.; Czesnikiewicz-Guzik, M.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Orlandi, M.; Guzik, T.J.; Hingorani, A.D.; Nart, J.; D’aiuto, F. Periodontitis is associated with hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 116, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könnecke, H.; Schnabel, R.B.; Walther, C.; Lamprecht, R.; Heydecke, G.; Seedorf, U.; Jagodzinski, A.; Borof, K.; Zeller, T.; Beikler, T.; et al. Cross-sectional study on the association of periodontitis with arterial hypertension in the Hamburg City Health Study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paizan, M.L.M.; Vilela-Martin, J.F. Is There an Association between Periodontitis and Hypertension? Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2014, 10, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silveira, T.M.; e Silva, C.F.; Vaucher, R.d.A.; Angst, P.D.M.; Casarin, M.; Pola, N.M. Higher frequency of specific periodontopathogens in hypertensive patients. A pilot study. Braz. Dent. J. 2022, 33, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, F.; Cordovil, I.; Figueredo, C.M.S.; Fischer, R.G. Non-surgical periodontal treatment reduces cardiovascular risk in refractory hypertensive patients: A pilot study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; del Castillo, A.M.; Jepsen, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; D’aiuto, F.; Bouchard, P.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Gotsman, I.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ye, H.; Liu, W.; Lv, Z.; Jia, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y. Effect of periodontal treatments on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD009409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, D.S.; Garg, S.; Ramteke, G.B.; Ratre, M.S. Effect of Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment on Clinical and Biochemical Risk Markers of Cardiovascular Disease: A Randomized Trial. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).