Abstract

Initially discovered as the smallest component of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) system, the IFT20 protein has been found to be implicated in several unconventional mechanisms beyond its essential role in the assembly and maintenance of the primary cilium. IFT20 is now considered a key player not only in ciliogenesis but also in vesicular trafficking of membrane receptors and signaling proteins. Moreover, its ability to associate with a wide array of interacting partners in a cell-type specific manner has expanded the function of IFT20 to the regulation of intracellular degradative and secretory pathways. In this review, we will present an overview of the multifaceted role of IFT20 in both ciliated and non-ciliated cells.

1. Introduction

Almost 30 years ago, the discovery of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) system by Rosenbaum’s lab paved the way to the characterization of the molecular pathways that regulate the assembly and maintenance of cilia and flagella [1]. Cilia and flagella are hair-like structures with locomotive properties (motile cilia and flagella) or the ability to sense the surrounding environment and regulate signaling pathways (non-motile cilia or primary cilia). In humans, the primary cilium (PC) is found in almost all cell types, whereas motile cilia are restricted to a group of specialized cells as exemplified by cells of the respiratory tract [2]. Flagella are found primarily on gametes.

At the structural level, these cellular organelles are composed of a central part consisting of an axoneme of nine microtubules (nine plus two central microtubules for motile cilia and flagella, nine plus zero lacking the central pair for the non-motile PC) that extends from a basal body (a modified mother centriole) surrounded by the ciliary membrane, a specialized extension of the plasma membrane [3,4,5]. Cilia and flagella are devoid of ribosomes, and all proteins required in these organelles must be imported from the cell body. This process relies on an active transport system, known as the intraflagellar transport (IFT) system [1,6,7,8].

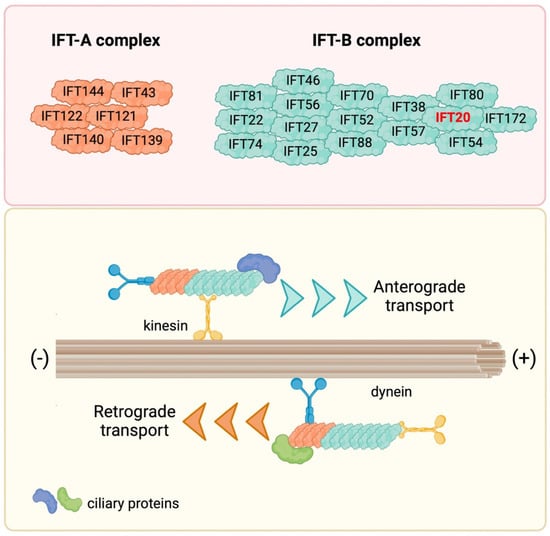

Initially discovered in 1993 in the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, further studies demonstrated that the IFT is operational in most eukaryotic cilia and flagella (reviewed in [9,10]). Along the length of longitudinal sections of Chlamydomonas flagella, the IFT system appears as granule-like particles localized between the microtubules and the flagellar membrane, forming a long series of particles referred to as IFT trains [1,11]. The IFT machinery consists of two biochemically distinct IFT complexes, IFT-A and IFT-B complex, containing different proteins. Specifically, the IFT-A complex contains six proteins (IFT43, IFT121, IFT122, IFT139, IFT140 and IFT144), and the IFT-B complex 16 proteins (IFT20, IFT22, IFT25, IFT27, IFT38, IFT46, IFT52, IFT54, IFT56, IFT57, IFT70, IFT74, IFT80, IFT81, IFT88 and IFT172) [12,13] (Figure 1). The main role of the IFT complexes is to carry cargos along the axonemal microtubules from the cell body to the tips of cilia and flagella (anterograde transport) and then back to the cell body (retrograde transport) with the help of molecular motors kinesin and dynein, respectively, for cilia assembly, disassembly and maintenance [14,15,16,17,18]. In recent years, new functions for IFT have been linked to signaling pathways that regulate key cellular functions, including, among others, Hedgehog, Wnt and Notch, and to the traffic of ciliary membrane components, including membrane receptors such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), the Sonic hedgehog (SHH) receptor Patched1 (PTCH1), and a variety of ion channels and signaling proteins [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. In addition to its roles in ciliated cells, the IFT system participates in vesicular trafficking also in non-ciliated cells [29].

Figure 1.

The IFT machinery and its components. IFT proteins are organized in two complexes, namely the IFT-A and IFT-B complex, which carry ciliary proteins along the axonemal microtubules from the cell body to the ciliary tip (anterograde transport) and then back to the cell body (retrograde transport) by interacting with the molecular motors kinesin and dynein, respectively.

Among the IFT proteins, the smallest is IFT20, the only IFT protein with a dual localization (basal body and Golgi) in ciliated cells that confers this protein pleiotropic functions. Here, we review the cumulative knowledge of IFT20, starting from its structure and function to discuss the most recent findings on its role in the assembly of the non-motile primary cilium and vesicular trafficking. Moreover, other emerging roles of IFT20 in both ciliated and non-ciliated cells will be discussed.

2. Molecular Dissection of IFT20: Structure and Localization

In humans, the IFT20 gene is composed of five exons and is localized on chromosome 17q11.2. Four isoforms have been described for IFT20, produced by alternative splicing, and five additional potential isoforms have been computationally mapped. Among the described isoforms, isoforms 2, 3 and 4 differ from the canonical one (isoform 1) for the insertion of 26 or 16 amino acids for isoform 2 and 3, respectively, or deletion of a stretch of 18 amino acids for isoform 4. The canonical isoform of human IFT20 is highly conserved among mammals and the other classes of vertebrates (fish and amphibians), with an 85–99% amino acid sequence homology as well as a functional homology as a regulator of ciliary processes. Among invertebrates, IFT20 is only found in D. melanogaster and C. elegans, with a 33% and 36% homology with human IFT20, respectively. Notwithstanding the lower homology, IFT20 is required for ciliogenesis also in nematodes [30].

Until now, the only domain identified in the human IFT20 structure is the coiled-coil (CC) domain at position 74–114 at its C-terminus, which mediates protein–protein interactions with other CC domain-containing components of the IFT complex [31,32] and potentially with other CC domain-containing proteins. Recently, a motif in the sequence of IFT20, corresponding to amino acids Y111-E118-F124-I129 (YEFI motif) has been identified as responsible for binding to the WD40 domain of the autophagy-related protein ATG16 [33].

IFT20 is expressed in wide variety of tissues with the highest expression in testis, liver, pancreas and adrenal gland [34]. At the subcellular level, IFT20 localizes at the primary cilium and at the basal body of ciliated cells [9]. The basal body localization of IFT20 is cholesterol-dependent, as shown by the failure of IFT20 to be recruited to the centrioles when intracellular cholesterol distribution was perturbed by depletion of the peroxisomal protein TMEM135 [35]. During the cell cycle, IFT20 associates with centrosomes [36]. Moreover, IFT20 is the only IFT protein that was also found associated with both the Golgi apparatus and early and recycling endosomes [36,37] in non-dividing cells, revealing new functions for IFT20 other than intraflagellar transport.

3. Ciliary Trafficking of IFT20: From the Golgi Apparatus to the PC Tip

3.1. Cilium Assembly and Maintenance

The PC is a cellular structure with unique protein and lipid distribution whose composition is finely regulated in time and space [38,39,40]. There is no evidence that ciliary proteins may be directly synthesized in the PC. Instead, proteins localized in the PC are transported to the ciliary base from the Golgi and the cytosol by vesicular trafficking. Trafficking is then taken over by the IFT system.

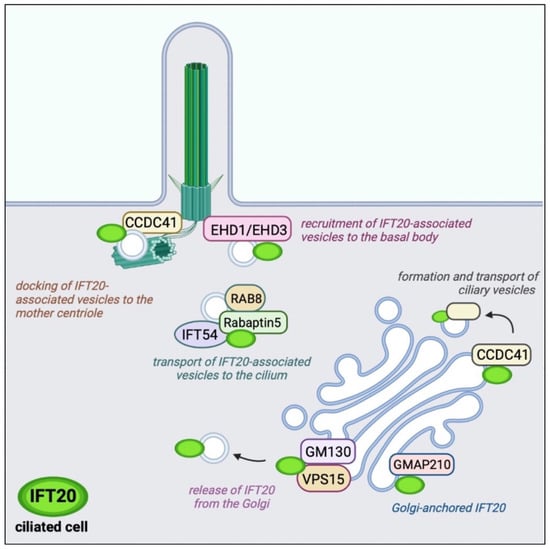

IFT20 is anchored to both the cis and medial cisternae of the Golgi complex by the Golgi resident protein GMAP210, a member of the golgins [41] (Figure 2). A pool of the CC domain-containing 41 (CCDC41) associates with IFT20 at the Golgi and participates in the formation and transport of ciliary vesicles from the Golgi complex to the basal body [42]. These vesicles are enriched in ciliary membrane proteins to be transported to the PC [43]. The release of IFT20 from the Golgi is mediated by another Golgi-resident protein, GM130, which forms a complex with VPS15 and allows the release of IFT20-associated vesicles with the contribution of the microtubule-based motor KIFC1 to ensure the IFT20-dependent transport of membrane proteins toward the PC [44,45,46].

Figure 2.

Localization and function of IFT20 interacting proteins in ciliated cells. IFT20 associates with a variety of protein interactors not only at the basal body (EHD1/EHD3) and mother centriole (CCDC41) but also at the Golgi apparatus (GMAP210, CCDC41, GM130/VPS15) and ciliary vesicles (Rab8/Rabaptin5/IFT54) in ciliated cells.

IFT20-associated vesicles interact and fuse with vesicles decorated by the small GTPase Rab8 and its effector Rabaptin5, and are directed to the base of the PC with the help of IFT54 (elipsa in zebrafish) that functions as a bridge between IFT20 and Rabaptin5 [32]. The presence of Rab8 in these vesicles ensures the transport of vesicles to the PC and their fusion with the plasma membrane at the ciliary base [38,47]. Rab8 acts as a membrane trafficking regulator in the Rab11-Rab8 cascade in which Rabin8, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rab8, binds to Rab11 and is delivered to the centrosome. At the centrosome, Rabin8 associates with the multimolecular complex Bardet–Biedl syndrome complex (BBSome) on vesicles to activate Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane assembly [39,40]. The proteins EHD1 and EHD3 interface with this cascade to allow the recruitment of transition-zone proteins and IFT20 during centriole maturation and its transformation into the basal body [48]. EHD1/EHD3 depletion by RNA interference results in a defective accumulation of IFT20-positive vesicles at the mother centriole with defective ciliogenesis. A centrosomal pool of CCDC41 interacts with IFT20 and promotes its recruitment to the centrosome to mediate docking of ciliary vesicles to the mother centriole [42].

3.2. Trafficking of Receptors and Signaling Molecules

The mosaic of IFT20 interactors contributes not only to guide vesicle transport from the Golgi apparatus and to the basal body but also provides specificity to the trafficking of IFT20 cargos. Moreover, the discovery that other IFT subunits, as for example IFT88, are associated with vesicles different from those marked by IFT20 implies that different IFT proteins play complementary roles in delivering the unique types of cargos associated with the respective vesicles [35,49]. An elegant study by Monis VJ et al. helps to elucidate how ciliary receptors take different routes. IFT20, in concert with GMAP210 and the exocyst complex, directs the vesicular transport of transmembrane proteins such as fibrocystin and polycystin-2, while delivery of the G protein-coupled receptor Smoothened is largely independent of these components [50]. Moreover, IFT20 is responsible for the basal body localization of pallidin, one subunit of the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex-1 (BLOC-1) responsible for the ciliary delivery of polycystin-2, but not Smoothened or fibrocystin, through the recycling trafficking pathway [50]. IFT20 may also indirectly regulate the localization of the receptor PDGFRα through association with the E3 ubiquitin ligases c-Cbl and Cbl-b and is required for Cbl-mediated ubiquitination and internalization of PDGFRα for feedback inhibition of receptor signaling [51].

Recently, a new interactor of IFT20 in ciliated cells has been identified as the autophagy-related protein ATG16, which as part of this complex carries out an autophagy-unrelated function. Specifically, the interaction of ATG16 with IFT20 is required for the transport of the phosphatase INPP5E to the PC to ensure the correct local phosphoinositide distribution, on which the function of the PC crucially depends [33].

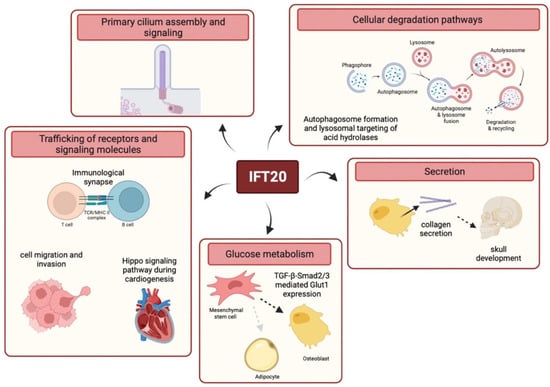

5. Conclusions

While originally identified as a molecule required for ciliogenesis and believed to be specifically expressed by ciliated cells, it is now evident that IFT20 plays a broader physiological role as a central regulator of intracellular trafficking. The emerging scenario is that by regulating intracellular vesicular transport, IFT20 controls crucial processes including PC assembly and ciliary signaling as well as cell activation and migration, autophagy, lysosome biogenesis and function, secretion and glucose metabolism (Figure 3). These findings underscore the importance of IFT20 in cell biology and open new scenarios. Loss of IFT20 has been associated with cystic kidney disease [94] and with achondroplasia [95]. However, based on its cellular functions [34], IFT20 defects may also be associated with different system-related diseases including those affecting the cardiovascular, immune, nervous, reproductive, and respiratory systems. Furthermore, IFT20 may be implicated in the modulation of signaling and cell differentiation of different cell types in addition to those previously described, which include T lymphocytes [37,53,62,65], proepicardium and myocardium cells [72], chondrocytes [96] and osteoblasts [83,89]. Interestingly, it has been recently reported that IFT20 is a critical regulator of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) lineage commitment at an early stage [93]. MSCs are multipotent stromal cells that can differentiate into a variety of cell types, including chondrocytes, osteoblasts, adipocytes, and myoblasts, and assist postnatal organ growth, repair and regeneration [97,98]. Li and colleagues found that loss of IFT20 in MSCs inhibits osteoblast differentiation but promotes adipocyte differentiation. Remarkably, they identify a new role for IFT20 in maintaining energy balance that prevents MSC lineage allocation into adipocytes by regulating glucose metabolism mediated by TGF-β-Smad2/3-Glut1 signaling. Importantly, this recent study identifies IFT20 as a promising drug target for the treatment of bone diseases such as osteoporosis and opens exciting new perspectives on the implication of IFT20 in other metabolic diseases.

IFT20 has also been implicated in cancer. In mouse breast cancer cells, IFT20 inhibits epithelial mesenchymal transition and cell migration [56], while in human osteosarcoma and colorectal cancer cells, it promotes invadopodia formation and tumor invasiveness [66,67]. Interestingly, a positive correlation of IFT20 expression with reduced risk of metastasis and prolonged survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma associated with specific clinicopathological features has recently been reported [99]. Thus, even though the role of IFT20 in cancer needs to be explored in more depth, these findings suggest that IFT20 could play important roles also during tumorigenesis.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication. F.F., A.O. and C.T.B. wrote the manuscript. A.O. and F.F. prepared the figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The support of EU (grant ERC-2021-SyG 951329) and AIRC (grant IG-20148) is gratefully acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The figures were created using BioRender.com, accessed on 30 March 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kozminski, K.G.; Johnson, K.A.; Forscher, P.; Rosenbaum, J.L. A Motility in the Eukaryotic Flagellum Unrelated to Flagellar Beating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 5519–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, A.E.; Walters, M.S.; Shaykhiev, R.; Crystal, R.G. Cilia Dysfunction in Lung Disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2015, 77, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satir, P.; Pedersen, L.B.; Christensen, S.T. The Primary Cilium at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornens, M. The Centrosome in Cells and Organisms. Science 2012, 335, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, E.A.; Raff, J.W. Centrioles, Centrosomes, and Cilia in Health and Disease. Cell 2009, 139, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A.; Rosenbaum, J.L. Polarity of Flagellar Assembly in Chlamydomonas. J. Cell Biol. 1992, 119, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, W.F.; Rosenbaum, J.L. Intraflagellar Transport Balances Continuous Turnover of Outer Doublet Microtubules: Implications for Flagellar Length Control. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 155, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazour, G.J.; Agrin, N.; Leszyk, J.; Witman, G.B. Proteomic Analysis of a Eukaryotic Cilium. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 170, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, J.L.; Witman, G.B. Intraflagellar Transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholey, J.M. Intraflagellar Transport. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003, 19, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigino, G.; Geimer, S.; Lanzavecchia, S.; Paccagnini, E.; Cantele, F.; Diener, D.R.; Rosenbaum, J.L.; Lupetti, P. Electron-Tomographic Analysis of Intraflagellar Transport Particle Trains in Situ. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piperno, G.; Mead, K. Transport of a Novel Complex in the Cytoplasmic Matrix of Chlamydomonas Flagella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 4457–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, D.G.; Diener, D.R.; Himelblau, A.L.; Beech, P.L.; Fuster, J.C.; Rosenbaum, J.L. Chlamydomonas Kinesin-II-Dependent Intraflagellar Transport (IFT): IFT Particles Contain Proteins Required for Ciliary Assembly in Caenorhabditis Elegans Sensory Neurons. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 141, 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Qin, H.; Follit, J.A.; Pazour, G.J.; Rosenbaum, J.L.; Witman, G.B. Functional Analysis of an Individual IFT Protein: IFT46 Is Required for Transport of Outer Dynein Arms into Flagella. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 176, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craft, J.M.; Harris, J.A.; Hyman, S.; Kner, P.; Lechtreck, K.F. Tubulin Transport by IFT Is Upregulated during Ciliary Growth by a Cilium-Autonomous Mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wren, K.N.; Craft, J.M.; Tritschler, D.; Schauer, A.; Patel, D.K.; Smith, E.F.; Porter, M.E.; Kner, P.; Lechtreck, K.F. A Differential Cargo-Loading Model of Ciliary Length Regulation by IFT. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2463–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigino, G. Intraflagellar Transport. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R530–R536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, G.; Mead, K.; Henderson, S. Inner Dynein Arms but Not Outer Dynein Arms Require the Activity of Kinesin Homologue Protein KHP1(FLA10) to Reach the Distal Part of Flagella in Chlamydomonas. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 133, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Snell, W.J. Kinesin II and Regulated Intraflagellar Transport of Chlamydomonas Aurora Protein Kinase. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 2179–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, S.C.; Anderson, K.V. The Primary Cilium: A Signalling Centre during Vertebrate Development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keady, B.T.; Samtani, R.; Tobita, K.; Tsuchya, M.; San Agustin, J.T.; Follit, J.A.; Jonassen, J.A.; Subramanian, R.; Lo, C.W.; Pazour, G.J. IFT25 Links the Signal-Dependent Movement of Hedgehog Components to Intraflagellar Transport. Dev. Cell 2012, 22, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, K.F.; Ashe, A.; He, M.; Satir, P.; Moran, J.; Beier, D.; Wicking, C.; Anderson, K.V. The IFT-A Complex Regulates Shh Signaling through Cilia Structure and Membrane Protein Trafficking. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 197, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguether, T.; SanAgustin, J.T.; Keady, B.T.; Jonassen, J.A.; Liang, Y.; Francis, R.; Tobita, K.; Johnson, C.A.; Abdelhamed, Z.A.; Lo, C.W.; et al. IFT27 Links the BBSome to IFT for Maintenance of the Ciliary Signaling Compartment. Dev. Cell 2014, 31, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheway, G.; Nazlamova, L.; Hancock, J.T. Signaling through the Primary Cilium. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazour, G.J.; Witman, G.B. The Vertebrate Primary Cilium Is a Sensory Organelle. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003, 15, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechtreck, K.F.; Johnson, E.C.; Sakai, T.; Cochran, D.; Ballif, B.A.; Rush, J.; Pazour, G.J.; Ikebe, M.; Witman, G.B. The Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii BBSome Is an IFT Cargo Required for Export of Specific Signaling Proteins from Flagella. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, K.; Katoh, Y. Architecture of the IFT Ciliary Trafficking Machinery and Interplay between Its Components. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 55, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.T.; Morthorst, S.K.; Mogensen, J.B.; Pedersen, L.B. Primary Cilia and Coordination of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) and Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β) Signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finetti, F.; Baldari, C.T. Compartmentalization of Signaling by Vesicular Trafficking: A Shared Building Design for the Immune Synapse and the Primary Cilium. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 251, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Castro, A.R.G.; Quintas-Gonçalves, J.; Silva-Ribeiro, T.; Rodrigues, D.R.M.; De-Castro, M.J.G.; Abreu, C.M.; Dantas, T.J. The IFT20 Homolog in Caenorhabditis Elegans Is Required for Ciliogenesis and Cilia-Mediated Behavior. MicroPubl. Biol. 2021, 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.A.; Freeman, K.; Luby-Phelps, K.; Pazour, G.J.; Besharse, J.C. IFT20 Links Kinesin II with a Mammalian Intraflagellar Transport Complex That Is Conserved in Motile Flagella and Sensory Cilia. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 34211–34218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omori, Y.; Zhao, C.; Saras, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kim, W.; Furukawa, T.; Sengupta, P.; Veraksa, A.; Malicki, J. Elipsa Is an Early Determinant of Ciliogenesis That Links the IFT Particle to Membrane-Associated Small GTPase Rab8. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukhalfa, A.; Roccio, F.; Dupont, N.; Codogno, P.; Morel, E. The Autophagy Protein ATG16L1 Cooperates with IFT20 and INPP5E to Regulate the Turnover of Phosphoinositides at the Primary Cilium. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.H.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Z.G. Intraflagellar Transport 20: New Target for the Treatment of Ciliopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, Y.; Lee, J.N.; Kwak, S.A.; Dutta, R.K.; Park, C.; Choe, S.; Park, R. TMEM135 Regulates Primary Ciliogenesis through Modulation of Intracellular Cholesterol Distribution. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e48901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follit, J.A.; Tuft, R.A.; Fogarty, K.E.; Pazour, G.J. The Intraflagellar Transport Protein IFT20 Is Associated with the Golgi Complex and Is Required for Cilia Assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 3781–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finetti, F.; Patrussi, L.; Masi, G.; Onnis, A.; Galgano, D.; Lucherini, O.M.; Pazour, G.J.; Baldari, C.T. Specific Recycling Receptors Are Targeted to the Immune Synapse by the Intraflagellar Transport System. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 1924–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachury, M.V.; Loktev, A.V.; Zhang, Q.; Westlake, C.J.; Peränen, J.; Merdes, A.; Slusarski, D.C.; Scheller, R.H.; Bazan, J.F.; Sheffield, V.C.; et al. A Core Complex of BBS Proteins Cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to Promote Ciliary Membrane Biogenesis. Cell 2007, 129, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knödler, A.; Feng, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Das, A.; Peränen, J.; Guo, W. Coordination of Rab8 and Rab11 in Primary Ciliogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6346–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlake, C.J.; Baye, L.M.; Nachury, M.V.; Wright, K.J.; Ervin, K.E.; Phu, L.; Chalouni, C.; Beck, J.S.; Kirkpatrick, D.S.; Slusarski, D.C.; et al. Primary Cilia Membrane Assembly Is Initiated by Rab11 and Transport Protein Particle II (TRAPPII) Complex-Dependent Trafficking of Rabin8 to the Centrosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2759–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follit, J.A.; San Agustin, J.T.; Xu, F.; Jonassen, J.A.; Samtani, R.; Lo, C.W.; Pazour, G.J. The Golgin GMAP210/TRIP11 Anchors IFT20 to the Golgi Complex. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, K.; Kim, C.G.; Lee, M.S.; Moon, H.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.J.; Kweon, H.S.; Park, W.Y.; Kim, C.H.; Gleeson, J.G.; et al. CCDC41 Is Required for Ciliary Vesicle Docking to the Mother Centriole. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5987–5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Huang, K. Transport of Ciliary Membrane Proteins. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roboti, P.; Sato, K.; Lowe, M. The Golgin GMAP-210 Is Required for Efficient Membrane Trafficking in the Early Secretory Pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoetzel, C.; Bär, S.; de Craene, J.O.; Scheidecker, S.; Etard, C.; Chicher, J.; Reck, J.R.; Perrault, I.; Geoffroy, V.; Chennen, K.; et al. A Mutation in VPS15 (PIK3R4) Causes a Ciliopathy and Affects IFT20 Release from the Cis-Golgi. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Joo, K.; Jung, E.J.; Hong, H.; Seo, J.; Kim, J. Export of Membrane Proteins from the Golgi Complex to the Primary Cilium Requires the Kinesin Motor, KIFC1. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, O.L.; Tam, B.M.; Hurd, L.L.; Peränen, J.; Deretic, D.; Papermaster, D.S. Mutant Rab8 Impairs Docking and Fusion of Rhodopsin-Bearing Post-Golgi Membranes and Causes Cell Death of Transgenic Xenopus Rods. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 2341–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Insinna, C.; Ott, C.; Stauffer, J.; Pintado, P.A.; Rahajeng, J.; Baxa, U.; Walia, V.; Cuenca, A.; Hwang, Y.S.; et al. Early Steps in Primary Cilium Assembly Require EHD1/EHD3-Dependent Ciliary Vesicle Formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Shao, L.; Yao, Y.; Tong, X.; Liu, H.; Yue, S.; Xie, L.; Cheng, S.Y. DGKδ Triggers Endoplasmic Reticulum Release of IFT88-Containing Vesicles Destined for the Assembly of Primary Cilia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monis, W.J.; Faundez, V.; Pazour, G.J. BLOC-1 Is Required for Selective Membrane Protein Trafficking from Endosomes to Primary Cilia. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 2131–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F.M.; Schou, K.B.; Vilhelm, M.J.; Holm, M.S.; Breslin, L.; Farinelli, P.; Larsen, L.A.; Andersen, J.S.; Pedersen, L.B.; Christensen, S.T. IFT20 Modulates Ciliary PDGFRα Signaling by Regulating the Stability of Cbl E3 Ubiquitin Ligases. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satir, P.; Mitchell, D.R.; Jékely, G. Chapter 3 How Did the Cilium Evolve. In Current Topics in Developmental Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 85, pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Finetti, F.; Paccani, S.R.; Riparbelli, M.G.; Giacomello, E.; Perinetti, G.; Pazour, G.J.; Rosenbaum, J.L.; Baldari, C.T. Intraflagellar Transport Is Required for Polarized Recycling of the TCR/CD3 Complex to the Immune Synapse. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedmak, T.; Wolfrum, U. Intraflagellar Transport Molecules in Ciliary and Nonciliary Cells of the Retina. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Begum, S.; Ezratty, E.J. An IFT20 Mechanotrafficking Axis Is Required for Integrin Recycling, Focal Adhesion Dynamics, and Polarized Cell Migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 1917–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, F.; Long, H.; Lin, Y.; Liao, J.; Xia, H.; Huang, K. IFT20 Mediates the Transport of Cell Migration Regulators From the Trans-Golgi Network to the Plasma Membrane in Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 632198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Rhodes, M.; Wiest, D.L.; Vignali, D.A. On the Dynamics of TCR:CD3 Complex Cell Surface Expression and Downmodulation. Immunity 2000, 13, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kremer, K.N.; Dominguez, D.; Tadi, M.; Hedin, K.E. G 13 and Rho Mediate Endosomal Trafficking of CXCR4 into Rab11+ Vesicles upon Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 Stimulation. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayle, K.M.; Le, A.M.; Kamei, D.T. The Intracellular Trafficking Pathway of Transferrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, B.D.; Donaldson, J.G. Pathways and Mechanisms of Endocytic Recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onnis, A.; Baldari, C.T. Orchestration of Immunological Synapse Assembly by Vesicular Trafficking. Orchestration of Immunological Synapse Assembly by Vesicular Trafficking. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivar, O.I.; Masi, G.; Carpier, J.; Magalhaes, J.G.; Galgano, D.; Pazour, G.J.; Amigorena, S.; Hivroz, C.; Baldari, C.T. IFT20 Controls LAT Recruitment to the Immune Synapse and T-Cell Activation in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchetti, A.E.; Bataille, L.; Carpier, J.M.; Dogniaux, S.; San Roman-Jouve, M.; Maurin, M.; Stuck, M.W.; Rios, R.M.; Baldari, C.T.; Pazour, G.J.; et al. Tethering of Vesicles to the Golgi by GMAP210 Controls LAT Delivery to the Immune Synapse. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgano, D.; Onnis, A.; Pappalardo, E.; Galvagni, F.; Acuto, O.; Baldari, C.T. The T Cell IFT20 Interactome Reveals New Players in Immune Synapse Assembly. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Garrett-Sinha, L.A.; Sarkar, D.; Yang, S. Deletion of IFT20 in Early Stage T Lymphocyte Differentiation Inhibits the Development of Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Bone Res. 2014, 2, 14038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Nishita, M.; Sonoda, J.; Ikeda, T.; Kakeji, Y.; Minami, Y. Intraflagellar Transport 20 Promotes Collective Cancer Cell Invasion by Regulating Polarized Organization of Golgi-Associated Microtubules. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishita, M.; Park, S.Y.; Nishio, T.; Kamizaki, K.; Wang, Z.; Tamada, K.; Takumi, T.; Hashimoto, R.; Otani, H.; Pazour, G.J.; et al. Ror2 Signaling Regulates Golgi Structure and Transport through IFT20 for Tumor Invasiveness. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Castro, A.; Marchesin, V.; Monteiro, P.; Lodillinsky, C.; Rossé, C.; Chavrier, P. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of MT1-MMP-Dependent Cancer Cell Invasion. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 32, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehlke, C.; Janusch, H.; Hamann, C.; Powelske, C.; Mergen, M.; Herbst, H.; Kotsis, F.; Nitschke, R.; Kuehn, E.W. A Cilia Independent Role of Ift88/Polaris during Cell Migration. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rønn Veland, I.; Lindbaek, L.; Christensen, S.T. Linking the Primary Cilium to Cell Migration in Tissue Repair and Brain Development. BioScience 2014, 64, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassioli, C.; Baldari, C.T. A Ciliary View of the Immunological Synapse. Cells 2019, 8, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, M.; Ortiz Lopez, L.; Jerabkova, K.; Lucchesi, T.; Vitre, B.; Han, D.; Guillemot, L.; Dingare, C.; Sumara, I.; Mercader, N.; et al. Intraflagellar Transport Complex B Proteins Regulate the Hippo Effector Yap1 during Cardiogenesis. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Heallen, T.; Martin, J.F. The Hippo Pathway in the Heart: Pivotal Roles in Development, Disease, and Regeneration. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, C.A.; Kristensen, S.G.; Møllgard, K.; Pazour, G.J.; Yoder, B.K.; Larsen, L.A.; Christensen, S.T. The Primary Cilium Coordinates Early Cardiogenesis and Hedgehog Signaling in Cardiomyocyte Differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 3070–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finetti, F.; Capitani, N.; Baldari, C.T. Emerging Roles of the Intraflagellar Transport System in the Orchestration of Cellular Degradation Pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampliega, O.; Orhon, I.; Patel, B.; Sridhar, S.; Díaz-Carretero, A.; Beau, I.; Codogno, P.; Satir, B.H.; Satir, P.; Cuervo, A.M. Functional Interaction between Autophagy and Ciliogenesis. Nature 2013, 502, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Petroni, G.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Ballabio, A.; Boya, P.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Cadwell, K.; Cecconi, F.; Choi, A.M.K.; et al. Autophagy in Major Human Diseases. EMBO J. 2021, 40, 108863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Chen, Y.; Tooze, S.A. Autophagy Pathway: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Autophagy 2018, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhon, I.; Dupont, N.; Zaidan, M.; Boitez, V.; Burtin, M.; Schmitt, A.; Capiod, T.; Viau, A.; Beau, I.; Wolfgang Kuehn, E.; et al. Primary-Cilium-Dependent Autophagy Controls Epithelial Cell Volume in Response to Fluid Flow. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finetti, F.; Cassioli, C.; Cianfanelli, V.; Zevolini, F.; Onnis, A.; Gesualdo, M.; Brunetti, J.; Cecconi, F.; Baldari, C.T. The Intraflagellar Transport Protein IFT20 Recruits ATG16L1 to Early Endosomes to Promote Autophagosome Formation in T Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 634003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finetti, F.; Cassioli, C.; Cianfanelli, V.; Onnis, A.; Paccagnini, E.; Kabanova, A.; Baldari, C.T. The Intraflagellar Transport Protein IFT20 Controls Lysosome Biogenesis by Regulating the Post-Golgi Transport of Acid Hydrolases. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Teves, M.E.; Liu, H.; Strauss, J.F.; Pazour, G.J.; Foster, J.A.; Hess, R.A.; et al. Intraflagellar Transport Protein IFT20 Is Essential for Male Fertility and Spermiogenesis in Mice. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 3705–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, K.; Kitami, M.; Kitami, K.; Kaku, M.; Komatsu, Y. Canonical and Noncanonical Intraflagellar Transport Regulates Craniofacial Skeletal Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2589–E2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyadjiev, S.A.; Fromme, J.C.; Ben, J.; Chong, S.S.; Nauta, C.; Hur, D.J.; Zhang, G.; Hamamoto, S.; Schekman, R.; Ravazzola, M.; et al. Cranio-Lenticulo-Sutural Dysplasia Is Caused by a SEC23A Mutation Leading to Abnormal Endoplasmic-Reticulum-to-Golgi Trafficking. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyadjiev, S.; Kim, S.D.; Hata, A.; Haldeman-Englert, C.; Zackai, E.; Naydenov, C.; Hamamoto, S.; Schekman, R.; Kim, J. Cranio-Lenticulo-Sutural Dysplasia Associated with Defects in Collagen Secretion. Clin. Genet. 2011, 80, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, P.; Bolton, A.D.; Funari, V.; Hong, M.; Boyden, E.D.; Lu, L.; Manning, D.K.; Dwyer, N.D.; Moran, J.L.; Prysak, M.; et al. Lethal Skeletal Dysplasia in Mice and Humans Lacking the Golgin GMAP-210. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernet-Gallay, K.; Antony, C.; Johannes, L.; Bornens, M.; Goud, B.; Rios, R.M. The Overexpression of GMAP-210 Blocks Anterograde and Retrograde Transport between the ER and the Golgi Apparatus. Traffic 2002, 3, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitami, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ebina, M.; Kaku, M.; Chen, D.; Komatsu, Y. IFT20 Is Required for the Maintenance of Cartilaginous Matrix in Condylar Cartilage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 509, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Terajima, M.; Kitami, M.; Wang, J.; He, L.; Saeki, M.; Yamauchi, M.; Komatsu, Y. IFT20 Is Critical for Collagen Biosynthesis in Craniofacial Bone Formation HHS Public Access. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 533, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Li, X.; Yuan, X.; Yang, S.; Han, L.; Yang, S. Primary Cilia Control Cell Alignment and Patterning in Bone Development via Ceramide-PKCζ-β-Catenin Signaling. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.W.; Cho, J.H.; Conway, H.E.; DiGruccio, M.R.; Ng, X.W.; Roseman, H.F.; Abreu, D.; Urano, F.; Piston, D.W. Primary Cilia Control Glucose Homeostasis via Islet Paracrine Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8912–8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, F.; Scerbo, M.J.; Seelig, A.; Wagner, R.; O’Brien, N.; Gerst, F.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.U.; Zeigerer, A.; Ullrich, S.; et al. Glucose Homeostasis Is Regulated by Pancreatic β-Cell Cilia via Endosomal EphA-Processing. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Qin, L.; Yang, S. IFT20 Governs Mesenchymal Stem Cell Fate through Positively Regulating TGF-β-Smad2/3-Glut1 Signaling Mediated Glucose Metabolism. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, J.A.; Agustin, J.S.; Follit, J.A.; Pazour, G.J. Deletion of IFT20 in the Mouse Kidney Causes Misorientation of the Mitotic Spindle and Cystic Kidney Disease. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 183, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Kaci, N.; Estibals, V.; Goudin, N.; Garfa-Traore, M.; Benoist-Lasselin, C.; Dambroise, E.; Legeai-Mallet, L. Constitutively-Active FGFR3 Disrupts Primary Cilium Length and IFT20 Trafficking in Various Chondrocyte Models of Achondroplasia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Kitami, M.; Uchima Koecklin, K.H.; He, L.; Wang, J.; Lagor, W.R.; Perrien, D.S.; Komatsu, Y. Temporospatial Regulation of Intraflagellar Transport Is Required for the Endochondral Ossification in Mice. Dev. Biol. 2022, 482, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kfoury, Y.; Scadden, D.T. Mesenchymal Cell Contributions to the Stem Cell Niche. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Liu, G.; Halim, A.; Ju, Y.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration and Tissue Repair. Cells 2019, 8, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Liao, W.; Yu, Q.; Lin, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fu, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Associations of IFT20 and GM130 Protein Expressions with Clinicopathological Features and Survival of Patients with Lung Adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).