Rapid, Abiotic Nitrous Oxide Production from Fe(II)-Driven Nitrate Reduction Governed by pH Under Acidic Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

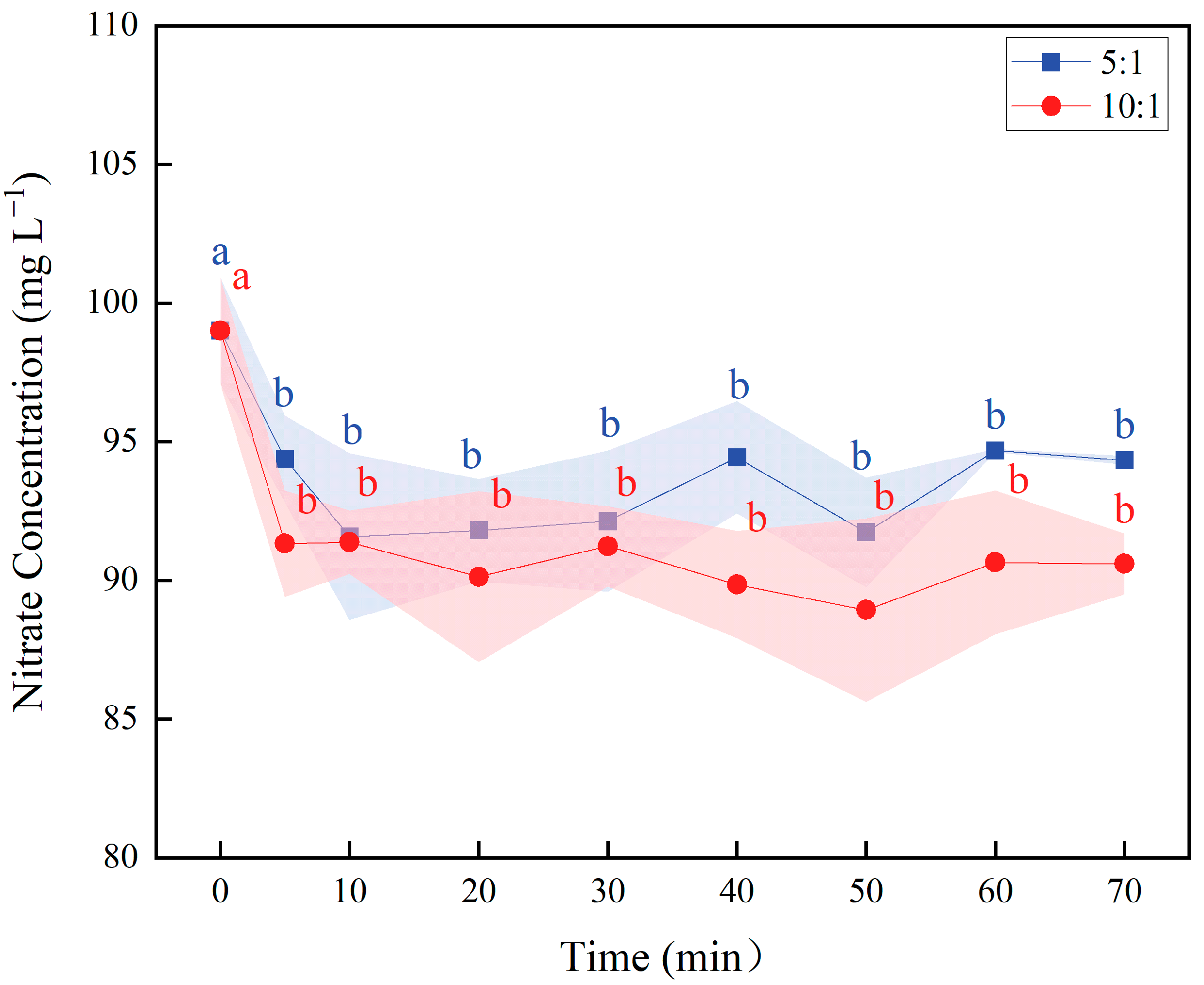

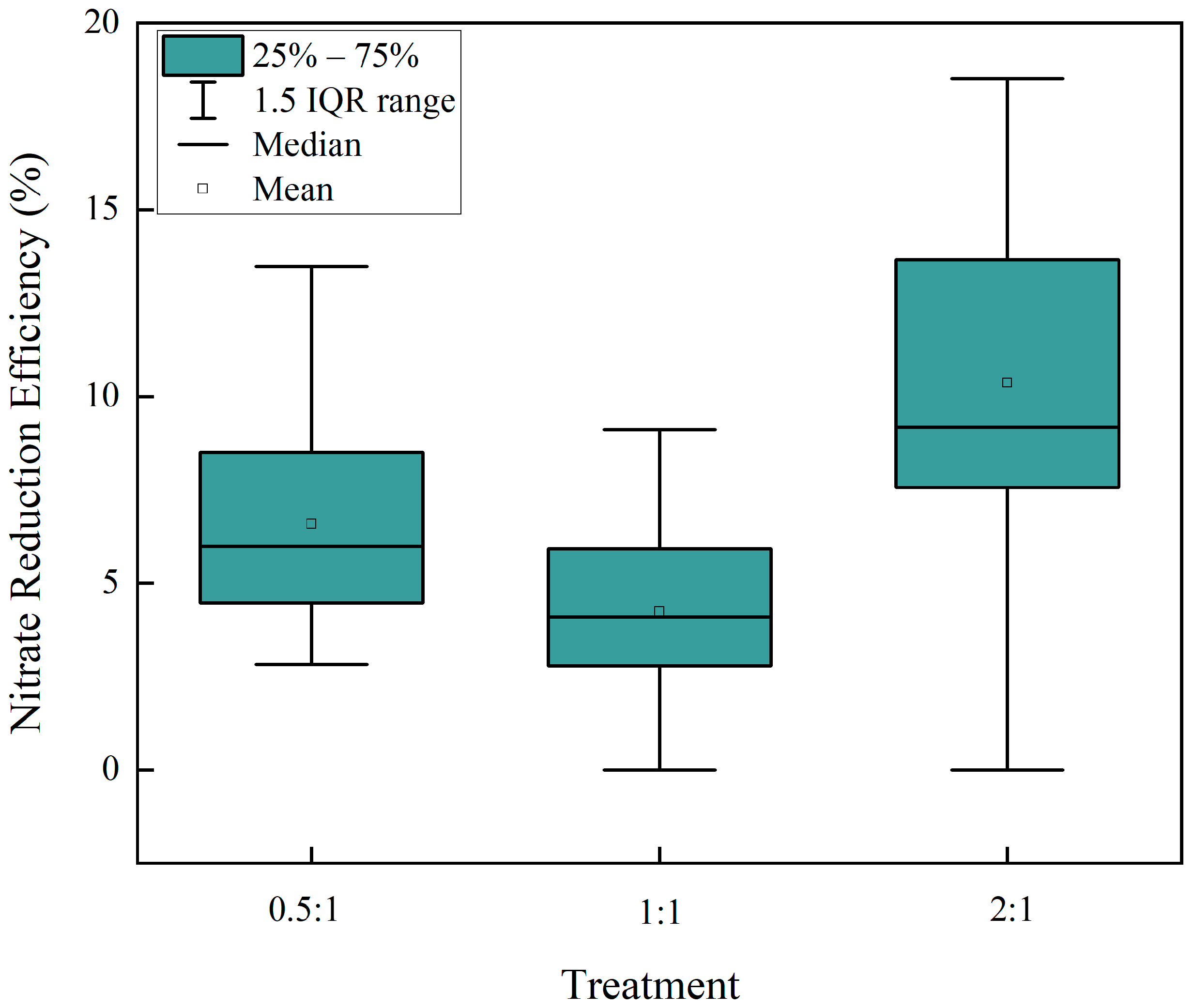

2.1. Influence of Mass Ratio on Nitrate Reduction Efficiency

2.2. Rapid Nitrate Reduction

2.3. Influence of Reaction Temperature

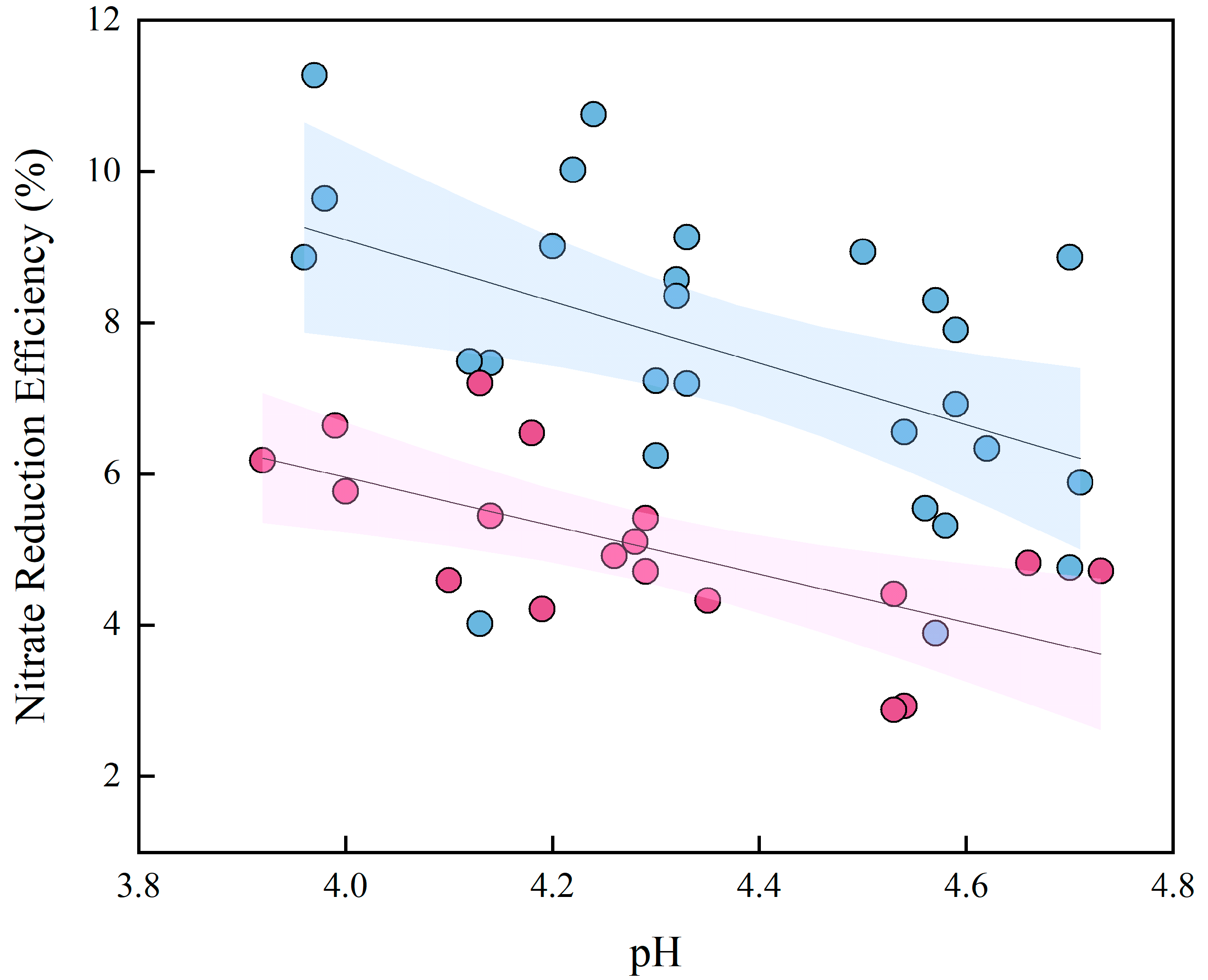

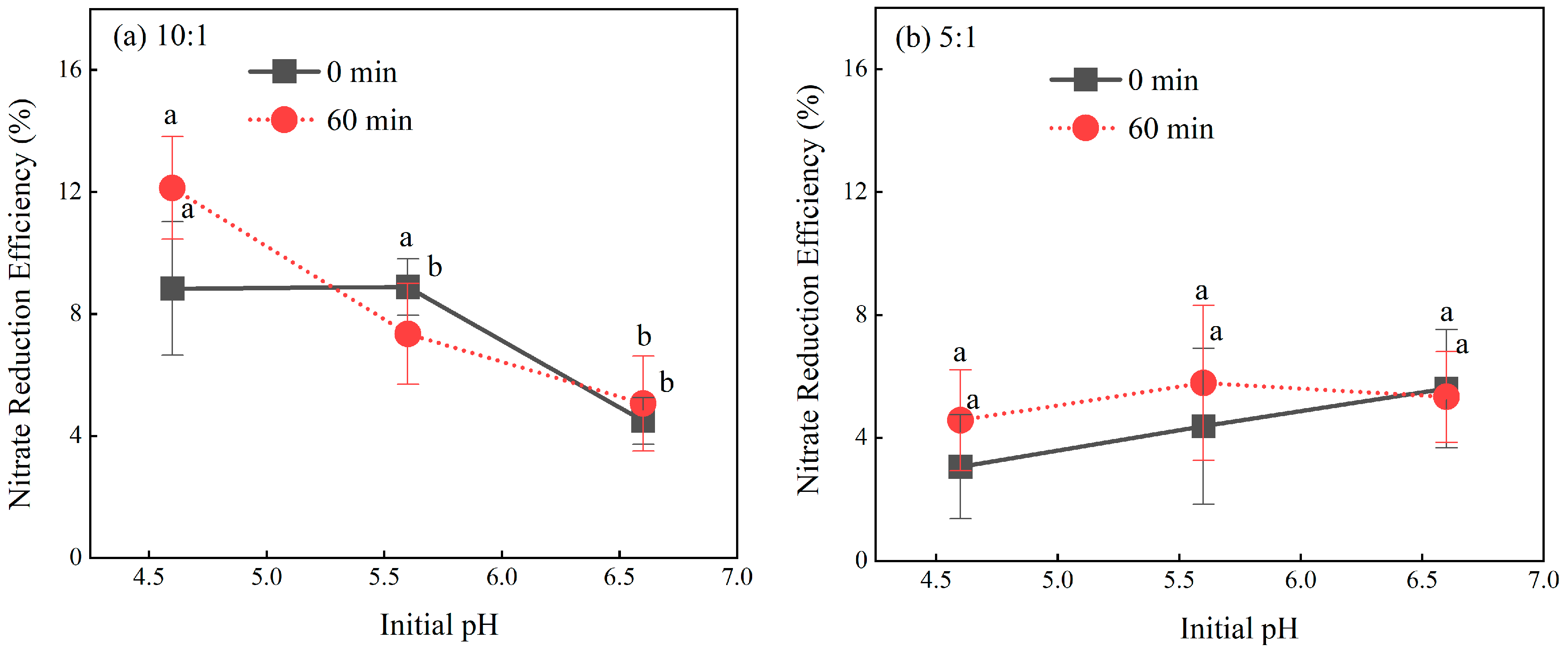

2.4. Role of Initial pH in the Nitrate Reduction

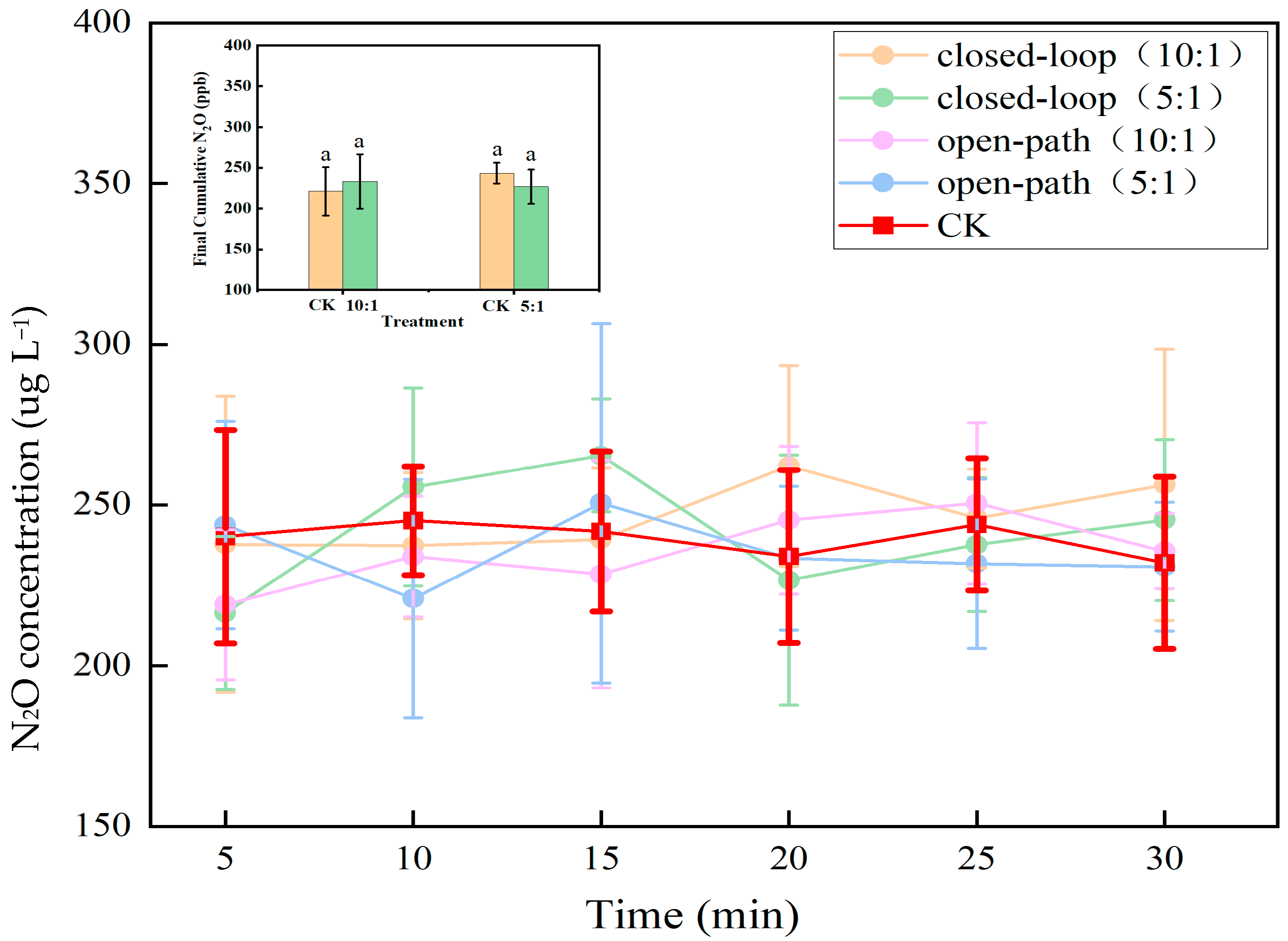

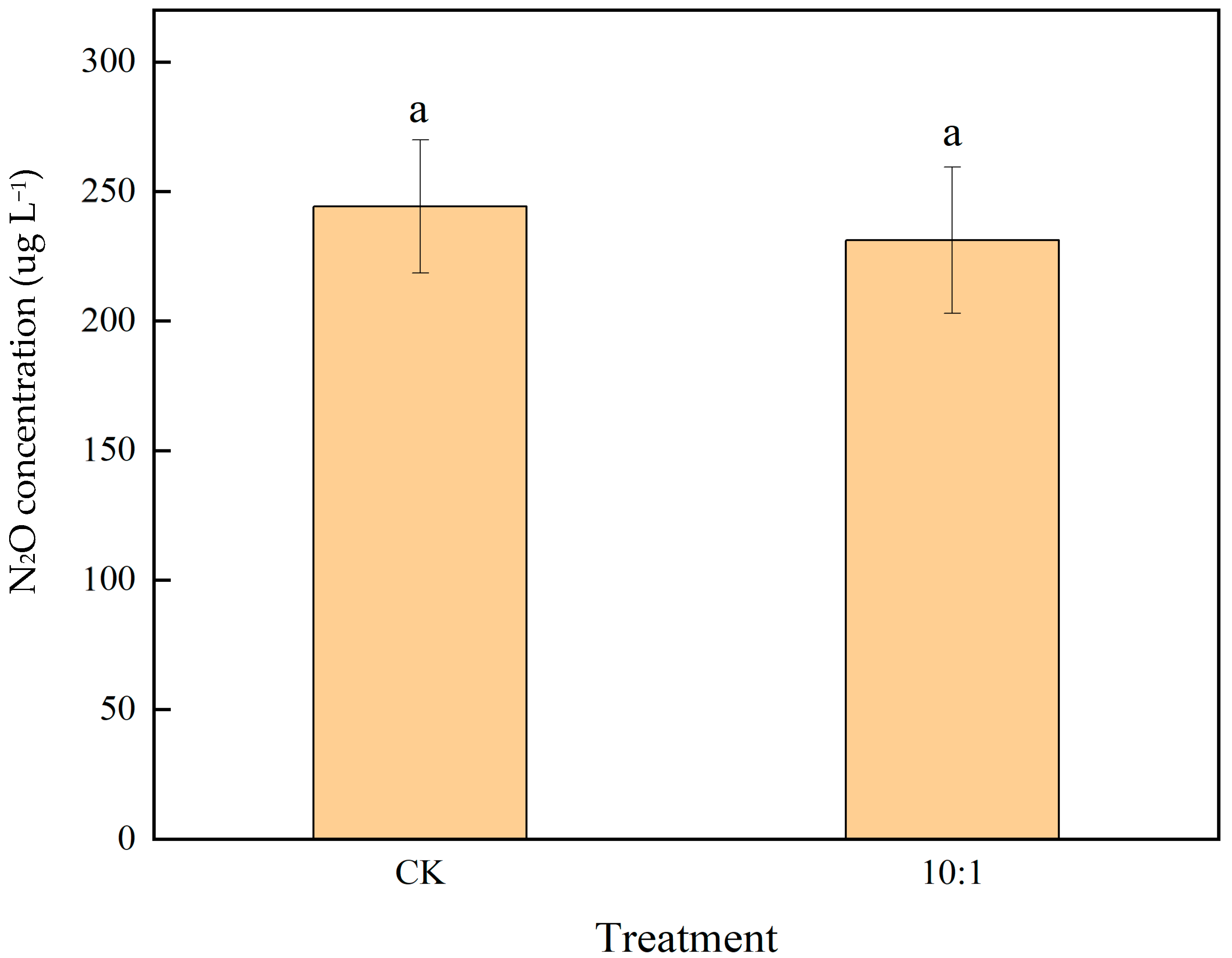

2.5. N2O Production Dynamics Under Varied Experimental Conditions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

4.1.1. Effect of Molar Ratio (n(Fe2+):n(NO3−))

4.1.2. Effect of Reaction Time

4.1.3. Effect of Reaction Temperature

4.1.4. Effect of Initial pH

4.2. N2O Analysis

4.2.1. Measurement Under Ambient Air Background

4.2.2. Measurement Under N2 Background

4.3. Spectroscopic Analysis and Modeling

4.4. Chemical Analysis

4.5. Software

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIRB | Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Bacteria |

| FTIR-ATR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Attenuated Total Reflectance Spectroscopy |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| NRFO | Nitrate-Reducing Fe2+ Oxidation |

| PLSR | Partial Least Squares Regression |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square Error |

| RPD | Ratio of Performance to Deviation |

References

- Fowler, D.; Pyle, J.A.; Raven, J.A.; Sutton, M.A. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century: Introduction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20130165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N.; Galloway, J.N. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 2008, 451, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, X.T.; Xing, G.X.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhang, L.J.; Liu, X.J.; Cui, Z.L.; Yin, B.; Christie, P.; Zhu, Z.L.; et al. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3041–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravishankara, A.R.; Daniel, J.S.; Portmann, R.W. Nitrous Oxide (N2O): The Dominant Ozone-Depleting Substance Emitted in the 21st Century. Science 2009, 326, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venterea, R.T.; Halvorson, A.D.; Kitchen, N.; Liebig, M.A.; Cavigelli, M.A.; Del Grosso, S.J.; Motavalli, P.P.; Nelson, K.A.; Spokas, K.A.; Singh, B.P.; et al. Challenges and opportunities for mitigating nitrous oxide emissions from fertilized cropping systems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matocha, C.J.; Dhakal, P.; Pyzola, S.M. The Role of Abiotic and Coupled Biotic/Abiotic Mineral Controlled Redox Processes in Nitrate Reduction. Adv. Agron. 2012, 115, 181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rakshit, S.; Matocha, C.J.; Coyne, M.S.; Sarkar, D. Nitrite reduction by Fe(II) associated with kaolinite. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Fernandez-Real, J.M. The role of iron in host-microbiota crosstalk and its effects on systemic glucose metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.H.; Li, W.X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, H.N.; Zhao, W. A novel iron-mediated nitrogen removal technology of ammonium oxidation coupled to nitrate/nitrite reduction: Recent advances. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegler, F.; Losekann-Behrens, T.; Hanselmann, K.; Behrens, S.; Kappler, A. Influence of seasonal and geochemical changes on the geomicrobiology of an iron carbonate mineral water spring. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7185–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.J.; Liang, Z.; Prinds, C.; Jéglot, A.; Thamdrup, B.; Kjaergaard, C.; Elsgaard, L. Nitrate reduction pathways and interactions with iron in the drainage water infiltration zone of a riparian wetland soil. Biogeochemistry 2020, 150, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, K.; Roy, H.; Jorgensen, B.B.; Kappler, A. Evidence for the Existence of Autotrophic Nitrate-Reducing Fe(II)-Oxidizing Bacteria in Marine Coastal Sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 6120–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Q.; Feng, Z.-T.; Zhou, J.-M.; Ma, X.; Sun, Y.-J.; Liu, J.-Z.; Zhao, J.Q.; Jin, R.C. Roles of Fe(II), Fe(III) and Fe0 in denitrification and anammox process: Mechanisms, advances and perspectives. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, R.; Ruser, R.; Schmidt, C.; Kappler, A. Role of Chemodenitrification for N2O Emissions from Nitrate Reduction in Rice Paddy Soils. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2019, 4, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D.R.; Holmes, D.E.; Nevin, K.P. Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) Reduction. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Elsevier Ltd.: London, UK, 2004; Volume 49, pp. 219–286. [Google Scholar]

- Stucki, J.W. A review of the effects of iron redox cycles on smectite properties. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2011, 343, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konhauser, K.O.; Kappler, A.; Roden, E.E. Iron in Microbial Metabolisms. Elements 2011, 7, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.A.; Achenbach, L.A.; Coates, J.D. Microorganisms pumping iron: Anaerobic microbial iron oxidation and reduction. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, K.L.; Benz, M.; Schink, B.; Widdel, F. Anaerobic, nitrate-dependent microbial oxidation of ferrous iron. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J. Abiotic nitrate loss and nitrogenous trace gas emission from Chinese acidic forest soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 22679–22687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cai, Z. Ferrous Iron and Anaerobic Denitrification in Subtropical Soils. Soil 2015, 47, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Fu, Y.Y.; Zhou, K.; Tian, T.; Li, Y.S.; Yu, H.Q. Microbial mixotrophic denitrification using iron(II) as an assisted electron donor. Water Res. X 2023, 19, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, D.; Luo, X.; Li, X.; Li, F. Microbially mediated nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidation: Quantification of chemodenitrification and biological reactions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2019, 256, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zheng, T.; Ma, H.; Hao, Y.; Liu, G.; Guo, B.; Shi, Q.; Zheng, X. Nitrate and nitrite reduction by adsorbed Fe(II) generated from ligand-promoted dissolution of biogenic iron minerals in groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaiges-Fernandez, R.; Offeddu, F.G.; Margalef-Marti, R.; Palau, J.; Urmeneta, J.; Carrey, R.; Otero, N.; Cama, J. Geochemical and isotopic study of abiotic nitrite reduction coupled to biologically produced Fe(II) oxidation in marine environments. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.; Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Bian, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Huo, A.; Guan, T.; Jing, H.; Wang, S. Iron-assisted anammox process under acidic conditions: A combination of chemical and biological mechanisms. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Minireview on Perovskite Oxide-Based Materials toward Enhanced Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction for Ammonia Synthesis: Advances and Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 20129–20143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.C.B.; Koch, C.B.; Nancke-Krogh, H.; Borggaard, O.K.; Sørensen, J. Abiotic Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium: Key Role of Green Rust. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996, 30, 2053–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.C.B.; Guldberg, S.; Erbs, M.; Koch, C.B. Kinetics of nitrate reduction by green rusts—Effects of interlayer anion and Fe(II):Fe(III) ratio. Appl. Clay Sci. 2001, 18, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottley, C.J.; Davison, W.; Edmunds, W.M. Chemical catalysis of nitrate reduction by iron(II). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 1819–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, Z.G.; Bartha, L.G. The Alkalimetric Determination of Nitrate Ion by Means of a Copper-Catalysed Reduction. Anal. Chim. Acta 1952, 6, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.L.; Drury, J.S. Nitrogen-Isotope Effects in the Reduction of Nitrate, Nitrite, and Hydroxylamine to Ammonia. I. In Sodium Hydroxide Solution with Fe (II). J. Chem. Phys. 1967, 46, 2833–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buresh, R.J.; Moraghan, J.T. Chemical Reduction of Nitrate by Ferrous Iron. J. Environ. Qual. 1976, 5, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, R.; Zhao, J.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Liu, S. Iron oxidation affects nitrous oxide emissions via donating electrons to denitrification in paddy soils. Geoderma 2016, 271, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 7480-1987; Water Quality—Determination of Nitrate—Spectrophotometric Method with Phenol Disulfonic Acid. National Environmental Protection Agency of China: Beijing, China, 1987.

- HJ 84-2016; Water Quality—Determination of Inorganic Anions (F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, PO43−, SO32−, SO42−)—Ion Chromatography. Ministry of Environmental Protection: Beijing, China, 2016.

- HJ/T 346-2007; Water Quality—Determination of Nitrate-Nitrogen—Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry (Trial). State Environmental Protection Administration: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Colman, B.P.; Fierer, N.; Schimel, J.P. Abiotic nitrate incorporation in soil: Is it real? Biogeochemistry 2007, 84, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, C.J.; Fischer, A.E.; Campbell, W.H.; Campbell, E.R. Corn leaf nitrate reductase—A nontoxic alternative to cadmium for photometric nitrate determinations in water samples by air-segmented continuous-flow analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.Z.; Li, C.Y.; Wan, P.Y.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.M. New Method for Eliminating the Iron Ions Interference in the Determination of Nitrate by UV Spectrophotometry. Chin. J. Spectrosc. Lab. 2011, 28, 3143–3147. [Google Scholar]

- Shaviv, A.; Kenny, A.; Shmulevitch, I.; Singher, L.; Raichlin, Y.; Katzir, A. Direct monitoring of soil and water nitrate by FTIR based FEWS or membrane systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2807–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linker, R.; Weiner, M.; Shmulevich, I.; Shaviv, A. Nitrate determination in soil pastes using attenuated total reflectance mid-infrared spectroscopy: Improved accuracy via soil identification. Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 94, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y. Characterization of Nitrification in Farmland Soil Using Techniques of Infrared Spectroscopy. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Ma, F.; Zhou, J.; Du, C. Attenuated Total Reflectance Crystal of Silicon for Rapid Nitrate Sensing Combining Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 47613–47620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. In Volume IV: General Rules <1421> Sterilization Method; China Medical Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, D.; Fleming, E.J.; McBeth, J.M. Iron-Oxidizing Bacteria: An Environmental and Genomic Perspective. In Annual Review of Microbiology; Annual Reviews: San Mateo, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 64, pp. 561–583. [Google Scholar]

- Fukada, T.; Hiscock, K.M.; Dennis, P.F.; Grischek, T. A dual isotope approach to identify denitrification in groundwater at a river-bank infiltration site. Water Res. 2003, 37, 3070–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravena, R.; Robertson, W.D. Use of Multiple Isotope Tracers to Evaluate Denitrification in Ground Water: Study of Nitrate from a Large-Flux Septic System Plume. Groundwater 2005, 36, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.S.; Casciotti, K.L. Nitrogen and oxygen isotopic fractionation during microbial nitrite reduction. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2016, 61, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabb, K.C.; Buchwald, C.; Hansel, C.M.; Wankel, S.D. A dual nitrite isotopic investigation of chemodenitrification by mineral-associated Fe(II) and its production of nitrous oxide. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 196, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, C.; Casciotti, K.L. Isotopic ratios of nitrite as tracers of the sources and age of oceanic nitrite. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.P.; Shi, L.S.; Wang, Y.K.; Chen, Z.W.; Xu, J.M. Investigation of ferrous iron-involved anaerobic denitrification in three subtropical soils of southern China. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongxin, C.; Haiyan, D.; Tao, W.; Ruiqing, S.; Saibin, H.; Qiannan, H.; Li, X.H.; Wang, Z.H.; Huang, T.M. Evaluation of the Availability Status and Influencing Factors of Soil Available Iron, Manganese, Copper, and Zinc in Major Wheat Regions of China. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2024, 61, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Yina, Q. Prediction of Available Iron, Manganese, Copper, and Zinc Contents and Their Influencing Factors in Farmland Soils of Jiangjin District; Southwest University: El Paso, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing + Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Du, C.; Zheng, S.; Du, Y. In Situ Monitoring of Nitrate Content in Leafy Vegetables Using Attenuated Total Reflectance—Fourier-Transform Mid-infrared Spectroscopy Coupled with Machine Learning Algorithm. Food Anal. Methods 2021, 14, 2237–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, R.A.V.; McGlynn, R.N.; McBratney, A.B. Determing the composition of mineral-organic mixes using UV-vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Geoderma 2006, 137, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBT9724-2007; Chemical Reagent—General Rule for the Determination of pH. SAC: Beijing, China, 2007.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Ma, F.; Zhou, J.; Du, C. Rapid, Abiotic Nitrous Oxide Production from Fe(II)-Driven Nitrate Reduction Governed by pH Under Acidic Conditions. Molecules 2025, 30, 4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234580

Xu L, Ma F, Zhou J, Du C. Rapid, Abiotic Nitrous Oxide Production from Fe(II)-Driven Nitrate Reduction Governed by pH Under Acidic Conditions. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234580

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Liping, Fei Ma, Jianmin Zhou, and Changwen Du. 2025. "Rapid, Abiotic Nitrous Oxide Production from Fe(II)-Driven Nitrate Reduction Governed by pH Under Acidic Conditions" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234580

APA StyleXu, L., Ma, F., Zhou, J., & Du, C. (2025). Rapid, Abiotic Nitrous Oxide Production from Fe(II)-Driven Nitrate Reduction Governed by pH Under Acidic Conditions. Molecules, 30(23), 4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234580