Abstract

This article gives an overview of the research activity of the LAC2 team at LCC developed at Castres in the field of sustainable chemistry with an emphasis on the collaboration with a research team from the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science, Croatia. The work is situated within the context of sustainable chemistry for the development of catalytic processes. Those processes imply molecular complexes containing oxido-molybdenum, -vanadium, -tungsten or simple polyoxometalates (POMs) as catalysts for organic solvent-free epoxidation. The studies considered first the influence of the nature of complexes (and related ligands) on the reactivity (assessing mechanisms through DFT calculations) with model substrates. From those model processes, the work has been enlarged to the valorization of biomass resources. A part concerns the activity on vanadium chemistry and the final part concerns the use of POMs as catalysts, from molecular to grafted catalysts, (ep)oxidizing substrates from fossil and biomass resources.

1. Introduction

Among the several challenges that the chemical industry has to face in the future, the most visible is to diminish/erase its negative image, soiled for years by several unfortunate contaminations issues, hazards being mainly bad handling procedures and storage mistakes (ammonium nitrate explosions, chemical leaks from tankers, burning of chemicals) [1]. For a century, the market of organic molecules has mainly been based on relatively cheap and available fossil resources. The “cheap” version of those raw sources is diminishing and industries have to face some geopolitical issues, increasing their prices. Maintaining the production of such organic molecules, with a relative low price/cost, obliges academic/industrial chemists to consider the development of new sources. New fossil sources can still be discovered for several years (ca. 50–100 according to Association for the Study of Peak Oil-ASPO) but with low accessibility [2,3]. The use of fossil sources being one cause of global warming, the quest toward renewable and sustainable sources seems more than urgent. In the current time, there is high interest in the carbon footprints of all processes/products for public policies but also for energy- and matter-saving processes. This was among the reasons that academic and industrials scientists began to think about solutions for a “better chemistry”. Those ideas have been gathered in 12 principles in the beginning of 1990 called “Green Chemistry” [4]. This concept points out the urgent need for new processes that are more sustainable and less energy demanding. Presented solutions recommend using cleaner and safer processes to replace the actual chemical processes where hazards might more frequently occur [5]. All of those ideas are a straight line to solutions anticipating fossil depletion.

To save energy in a chemical process, one point is to diminish the activation energy of a chemical reaction. For this, catalytic processes, among the 12 principles pointed out by Anastas and Warner, are one relevant solution [6]. In addition to reactions in which the catalyst diminishes the activation energy barrier, making the chemical reaction faster and preferably more selective, the process should become cleaner by replacing, diminishing, or eliminating organic solvents (sometimes toxic and often from fossil sources) and finding new, renewable sources [7]. Several research groups developed new answers with one or more of those solutions. In the presented research, we have followed Green Chemistry principles, i.e., namely catalysis, catalysts recovery through grafting, organic solvent-free processes, and biomass valorization. Those objectives are realized in the LCC research group in close collaboration with international research groups, especially with the one from Croatia. All that is presented herein corresponds to the work developed by Castres for several years, within the frame of the LCC research group devoted to catalysis. Within the numerous possible simple chemical transformations, the work developed herein focused on oxidation reactions, i.e., olefin epoxidation and alcohol oxidations.

Oxidation processes are at the origin of the formation of numerous molecules present in nature. From a fundamental point of view, studying those processes helps to understand the formation of those compounds. From an applicative point of view, chemists tend to mimic faster natural oxidation processes in order to obtain in abundant quantities (and preferably with a decent price) molecules present in nature (but often in too small a quantity considering commercial application) [8] or to create new molecules for several other purposes (often pharmaceutical). The advantage of oxidation protocols is to be under air, in agreement with some principles of Green Chemistry (simple process). The impact of such reactions is huge since oxidation represents a big part of industrial chemical transformation. The pharmaceutical industry [9,10,11], polymer industry [12,13], as well as the flavor and fragrance industries [14,15] need simple building blocks, and starting reagents have to be easily accessible. For example, the most known efficient synthetic processes to perform olefin epoxidation or alcohol oxidation use non-green conditions. The use of toxic inorganic oxidants in a stoichiometric amount, strong acids and/or organic solvents represent the non-green area that has to be replaced in light of the previously cited Green Chemistry principles and safety regulations [16,17].

Some existing processes are found to be cleaner, including metal complexes and/or metal oxides as catalysts, with the use of a cleaner oxidant as H2O2 [18], TBHP [19], or O2 [20]. Among efficient metals, we focused on transition metals with low toxicity, i.e., Mo, W, and V. Most of those metal-catalyzed processes used organic solvents and, in the case of epoxidation especially, dichloroethane (DCE) has been found to the most efficient. The replacement of DCE and extension to any organic solvent is an interesting challenge that has been discussed in the context of the industrial sector [21,22,23].

“No solvent is the best solvent” is the motto of the catalyzed processes presented herein. For this, we have separated the work into several aspects, that dealing with molybdenum, tungsten, and vanadium coordination complexes containing mainly two types of tridentate ligands, including some mechanistic studies as well as valorization of biomass. The second aspect will focus on the use of commercial polyoxometalates as oxidation catalysts under organic solvent-free protocols, using organic salts and grafted salts, for simple model studies and on applied processes toward the synthesis of useful species or the use of biomass substrates.

2. Tridentate Ligands and Related Complexes

This section considers coordination complexes containing ONO or ONS coordination sphere tridentate ligands, some backbones derived from the salicylideneaminophenol (SAP), and those bearing hydrazone moieties. The results are collected according to the nature of the metal and the ligand in the case of fundamental studies and valorization is added in an extra sub-chapter.

2.1. Molybdenum and Tungsten Complexes

2.1.1. From SAP Ligands and Derivatives: Mechanistic Study

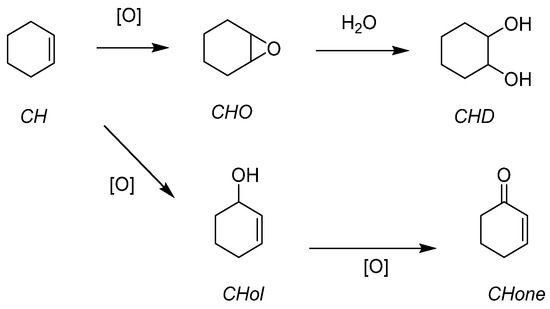

- Methodological Approach and Model Study with Cyclooctene

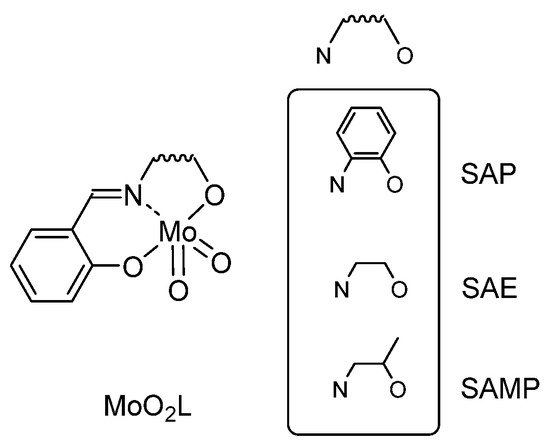

Among the metal-containing species exhibiting interesting catalytic activity, molybdenum was quite active and deeply used. Coordination complexes bearing tridentate ligands attracted our attention. Indeed, Mo is known to be at the core of several industrial processes, but conditions were not as green as they could be [24,25]. The work engaged herein started from the chemistry of [MoO2L] complexes with tridentate ligands, accessible complexes for sustainable chemistry. The studied tridentate H2L ligand (H2SAP) is obtained as the “Schiff base” formation by condensation of 1,2-aminophenol and salicylaldehyde. The related molybdenum complex is obtained starting from one precursor, [MoO2(acac)2] (acac = acetylacetonate), reacting in a stoichiometric amount with H2L ligand. [MoO2(SAP)(EtOH)] complex was previously described, and its catalytic activity toward epoxide was shown in organic media. In several articles from Sobczak and Ziółkowski [26,27], a good catalytic activity of the [MoO2(SAP)(EtOH)] was announced and placed the complex as a very promising catalyst. In the frame of a sustainable process, the reaction could be improved since the reaction was performed in the presence of a halogenated solvent (bromobenzene) and needed TBHP in decane as an oxidant, i.e., the presence of two organic solvents, one being halogenated.

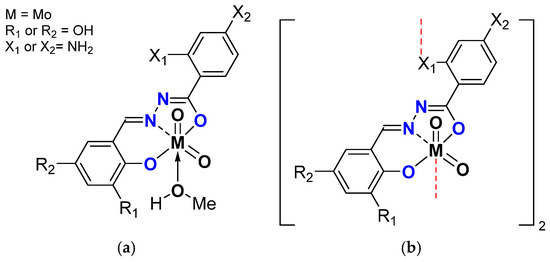

The idea developed herein has been to test the reactivity of the “MoO2(SAP)” complex and derivatives as catalysts in a more sustainable way. Thus, catalytic experiments were done in absence of any organic solvent, using TBHP in water as an oxidant and no organic solvent addition than the model substrate itself within the reaction media, i.e., cyclooctene (Figure 1). Water (from TBHP) was not a solvent in the process since it was observed that a biphasic system occurred with the presence of the catalyst within the organic phase (phase containing the substrate itself). As previously mentioned, the catalytic activity of those species was interesting and a beginning of mechanism postulation proposed an equilibrium between [MoO2L]2 and [MoO2L(ROH)] within the reaction media, being the starting base of the postulated mechanism with a potential pentaco-ordinate species [MoO2(L)] calculated by DFT and explained later.

Figure 1.

Organic solvent-free epoxidation of cyclo-octene.

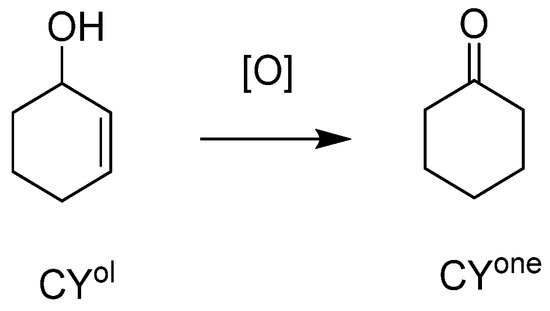

- Preliminary Studies toward the Best Backbone and Mechanistic Study

Two different ligands were synthesized using salicylaldehyde and 1,2 aminoethanol (leading to H2SAE ligand) or 1,2 aminophenol (leading to H2SAP ligand), Figure 2 [28]. Molecular structures of [MoO2(SAP)(EtOH)] and a polymorphic form of [MoO2(SAE)(SAEH2)] [29] were determined by X-ray diffraction. The “MoO2L” species have been studied in DFT according to the previously mentioned mechanism [26,27] and it was shown that both [MoO2(L)]2 (L = SAP, SAE) complexes needed less energy to be converted into the pentaco-ordinate mononuclear complex [MoO2L] than their ethanol-stabilized congeners [MoO2L(EtOH)] [28].

Figure 2.

Preliminary studied MoO2L structures.

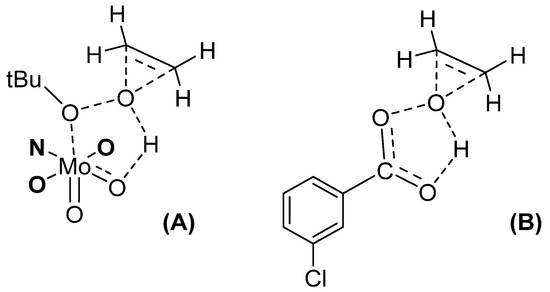

The catalytic activity of [MoO2L]2 and [MoO2L(MeOH)] complexes (L = SAE, SAMP, SAP) was studied through cyclo-octene epoxidation [30]. The nature of the ligand helped the system to be more active. Indeed, “MoO2(SAP)” based complexes were stable, but the SAE and SAMP ligands from complexes were hydrolyzed during the catalytic process. An induction period observed with the [MoO2L(MeOH)] species and not [MoO2L]2 confirmed that more energy was needed to deco-ordinate the monomer stabilized by a solvent than the dimer into the pentacoordinate active species, confirmed by the DFT calculations. A direct relationship could be established between the catalyst stability and selectivity. From the experimental work with those complexes, one DFT-calculated pathway fitted to experimental observations, showing a new type of TBHP activation, corresponding to the Bartlett postulation done in the Prizhaev reaction, i.e., when an olefin does react with a peroxyacid as m-CPBA [31]. The transition state (TS) corresponds to a loose coordination of TBHP to the Mo together with an H-bonding with an oxido moiety linked to the Mo center. From this, the oxygen atom from the TBHP linked to the hydrogen can be transferred to the olefin (as seen in Figure 3A). Although [MoO2(acac)2] is an active catalyst, the advantage of [MoO2(SAP)] derivatives lie in their strong stability.

Figure 3.

The transition state (TS) of olefin epoxidation using TBHP and MoO2(SAP) catalyst (A) vs. the m-CPBA postulated mechanism (B). For clarity of the drawing, the H2SAP ligand was limited to the ONO coordination sphere.

- Ligand Tuning and Optimization

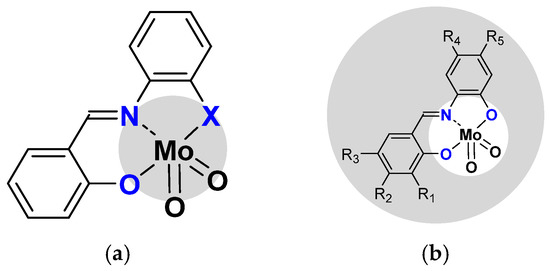

From this mechanism, optimization of the process was pursued using a slight modification of the ligand. The first change has been on the coordination sphere, comparing ONO with the ONS coordination sphere [32]. The [MoO2(SATP)] complex (ONS coordination sphere) was more active than [MoO2(SAP)] one (ONO coordination sphere) and activity was confirmed with DFT calculations (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

(a) Modification of coordination sphere X = O vs. X = S (b) Modification of the second sphere on R1 to R5 positions (specified in the text and in Table 1).

The modifications of the pending organic functions surrounding the H2SAP ligand (second co-ordination sphere) were performed to evaluate their effects (according to nature and/or position) on catalytic properties (Figure 4b). Additional DFT calculations could help to refine the proposed theoretical model. Thus, different substituents have been added and activity was compared toward cyclo-octene, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of cyclo-octene (CO) epoxidation under organic solvent-free conditions and selectivity towards cyclo-octene epoxide (COE) after 4 h. Comparison of first and second sphere influence (Structures are those from Figure 4) and corresponding transition state.

The addition of functional groups (R2 = diethylamino and/or R5 = nitro groups known for push-pull effects and modifications of NLO properties) at specific positions on the SAP backbone led to the comparison of four different molecules based on the presence or absence of both substituents [33]. The electronic effect of substituents on ligand might influence the electronic density of the molybdenum atom and subsequently the catalytic activity of the MoO2L complexes. Indeed, compared to [MoO2(SAP)] where no substitution occurred, the presence of the NO2 electron withdrawing group on the ligand increased the conversion, while the presence of electron-donating ligand NEt2 gave a reverse effect. The presence of both groups together inhibited their effects and the catalytic activity of the [MoO2L] complex was similar to [MoO2(SAP)]. Those experimental data were confirmed by DFT calculations with enthalpies values of the transition state (TS) in agreement with activity. A low TS (according to Figure 3) value was observed for highly active processes and vice-versa.

The presence of the OH group on the salicylic part of the ligand was also interesting to study. Thus, the effect of the presence of one pending OH function in ortho (R1), meta (R2), or para (R3) position to the phenolic oxygen atom linked to Mo on catalytic activity has been studied with cyclo-octene as a model substrate and compared to [MoO2(SAP)] moiety. The OH position strongly influences the activity toward cyclooctene with activity vs. [MoO2(SAP)] very high, slightly higher, and identical when OH lie in ortho, para, and meta positions, respectively [34]. The behavior was confirmed through DFT calculations with similar trends.

Other groups (OMe on ortho position (R1) as for the OH and Me on the aminoalcohol part of the ligand (R4 and R5)) have been added on SAP ligand and the corresponding [MoO2L(MeOH)] species (obtained through mechanochemistry and a solventless protocol, LAG) have been tested on different substrates [35]. With cyclo-octene, results showed that the presence of the methoxy group was the main factor toward a better activity. The methyl substituents in R4 and R5 positions did not have a noticeable effect.

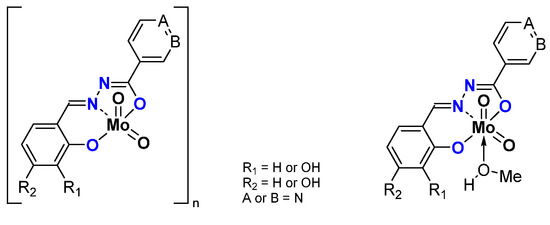

2.1.2. ONS, ONO Mo-Enlarging the Scope of Complexes through Collaboration

From the knowledge of [MoO2L] species to act as catalysts under organic solvent-free conditions, a collaboration has been established with Croatia in 2010. All catalytic results have been separated according to the nature of the ligands around the molybdenum. Carbazones, hydrazones, and thiosemicarbazones ligands have been developed and presented according to the nature of the hydrazide used. For all the species with such geometries, we emphasized the TON (Turn Over Number) and TOF (Turn Over Frequency) parameters of the catalytic processes. TON is defined as the number of substrates transformed per unit of catalyst at the end of the studied time, i.e., the number of cycles per catalyst. TOF corresponds to the number of substrates transformed per unit of catalyst in time intervals all along a reaction. This shows how the reaction can start fast or not, according to the catalyst.

- Pyridoxal Fragment within the Ligand

ONS coordination sphere–thiosemicarbazones

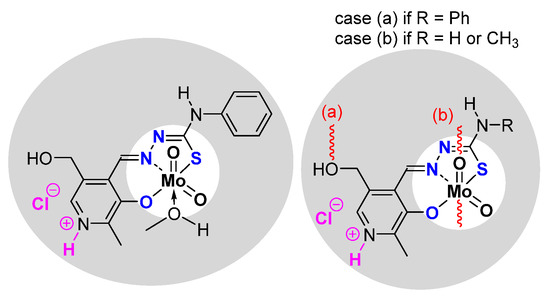

The synthesis of the thiosemicarbazonato dioxomolybdenum complexes based on pyridoxal ligand has been developed in Zagreb [36]. Pyridoxal possesses a free CH2OH pending function on a pyridine ring. On the other side of the ligand, thiosemicarbazide precursors possess different possible R terminal groups (R = H, Me, Ph). (Figure 5) Depending on the pyridoxal protonation; the formed molybdenum species can be neutral “[MoO2L]” or charged “[MoO2LH]Cl”. According to the presence (resp. absence) of donor molecules (for instance methanol), species can be stabilized as the monomer (resp. polymer) with polymerization mode influenced by the nature of R.

Figure 5.

Monomeric and polymeric species studied containing the pyridoxal fragment in the thosemicarbazonato ligand. Species are neutral but can be also charged (pink part).

Those species have been tested as catalysts and results (Table 2) indicated that the nature of R, catalytic ratio, charge (neutral/anionic) of the complex, and monomeric/polymeric form are all factors influencing the catalytic results.

Table 2.

Results of cyclo-octene (CO) epoxidation and selectivity towards cyclo-octene oxide (COE) under organic solvent free conditions catalyzed with MoO2L complexes from Figure 5.

The most efficient catalyst under organic solvent-free conditions is [MoO2L(MeOH)], i.e., the neutral complex (with R = Ph) stabilized by a molecule of methanol, while corresponding polymer [MoO2L]n (stabilized through the CH2OH pending function of a second MoO2L complex) is the less active. The studies showed that the addition of MeOH in high quantity inhibited the activity of the catalyst at the same level as the corresponding polymer itself. This study exhibited the role of methanol and its strong donation effect. All the equilibria within the process are in favor of the previously postulated mechanism in which the active species is the pentaco-ordinate complex [MoO2L] [37].

The charged complexes could be monomers or polymers as observed for the neutralcharges. The activity was lower than the neutral charges but the lower activity of the charged species corresponding to the most active neutral compound was more pronounced with monomers than for polymers [38].

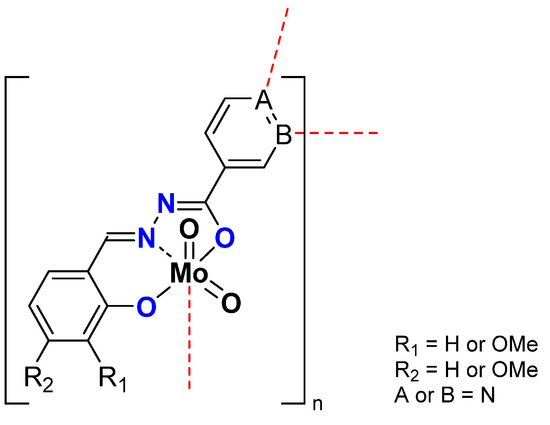

ONO coordination sphere–hydrazones

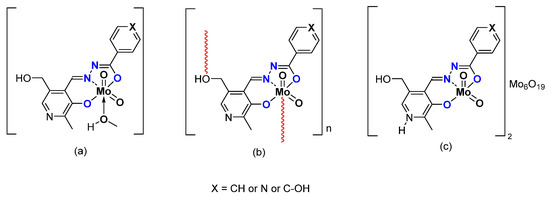

Other pyridoxal containing Mo complexes have been studied, using ligands bearing a hydrazonato function and a ONO coordination sphere (Figure 6). The difference lies in the X, being phenyl (X = CH), pyridine (X = N) or a phenol group (X = C-OH). As for the ONS, monomeric [MoO2L(MeOH)] or polymeric [MoO2L]n species were obtained. Interestingly, mixed hybrid compounds could be obtained, formally composed by two cationic coordination complex moieties [MoO2(LH)]+ and one Lindqvist polyanion [Mo6O19]2− [39]. Those species (Figure 6) were tested as catalysts under the same experimental conditions (Table 3). Conversion of cyclooctene depends on the nature of the species, i.e., monomer, polymer, or hybrid. Considering monomers vs. polymers, the monomeric complex [MoO2L(MeOH)]-with the highest conversion after 6 h (X = C-H)- has the lowest in a polymeric state. As for the ONS species, the monomeric species bear higher TOF, i.e., faster activation. The species containing POMs are more active with a higher conversion (they contain two potential active substances) but the higher selectivity is due to the [MoO2L] species.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of neutral monomeric (a) polymeric (b) and charged mixed hybrid (c) species studied containing the pyridoxal fragment in the hydrazonato ligand.

Table 3.

Results of cyclooctene (CO) epoxidation and selectivity towards cyclo-octene oxide (COE) with MoO2L complexes from Figure 6.

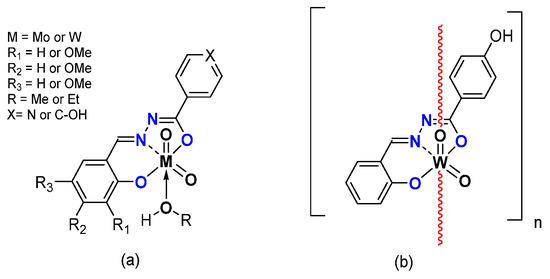

- From Mo to W Complexes with Salicylaldehyde Part: Some Experimental Features

Replacing the pyridoxal moiety by differently substituted salicylaldehydes led to monomeric [MO2L(EtOH)] (M = Mo, W) and polymeric [WO2L]n species [40] (Figure 7). The catalytic activity of molybdenum complexes was quite high (Table 4), with conversion up to 90% and selectivity quite low compared to the complexes containing pyridoxal moieties. Tungsten-related complexes exhibited very low activity under the same experimental conditions. The oxidant TBHP in water did not seem to be the right oxidant to achieve good conversion and good selectivity.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of neutral monomeric (a) and polymeric (b) Mo and Wspecies studied containing the salicylaldehydato fragment in the hydrazonato ligand.

Table 4.

Results of CO epoxidation and selectivity toward COE under organic solvent free conditions with MoO2L complexes from Figure 7.

The quest toward better experimental conditions was done with new ligands keeping the salicyladehyde moiety but adding isonicotinoyl hydrazines (X = C-OH), leading to [WO2L(MeOH)] and [WO2L(EtOH)] complexes [41].

Those species were tested under several experimental conditions. The reaction was faster using acetonitrile with TBHP in water as an oxidant but selectivity was worse than without acetonitrile. Reaction performed with TBHP in decane exhibited equivalent conversion than with TBHP in water but with higher selectivity, exhibiting the role of water. The effect of the coordinating alcohol was noticed, with a better conversion with EtOH, certainly due to a looser interaction with the W and a faster activation into a pentaco-ordinated species.

In the case of nicotinoyl hydrazides and molybdenum complexes (Figure 8), it was shown that the oligomerization rate has an influence on the reactivity. Indeed, while all compounds existed in polymeric form (with high nuclearity) specific experimental conditions could lead to the isolation of tetranuclear scaffolds that appeared to be highly active, more than the corresponding polymer. (Table 5) It exhibited that the mechanism suggesting the formation of pentacoordinate species was relevant and easier with oligomers than for polymers [42]. In this case, it was also shown that TBHP in decane was more efficient [43].

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of neutral polymeric Mo species studied containing the nicotinoyl hydrazonato ligand.

Table 5.

Results of CO epoxidation and selectivity towards COE under organic solvent free conditions with MoO2L complexes from Figure 8.

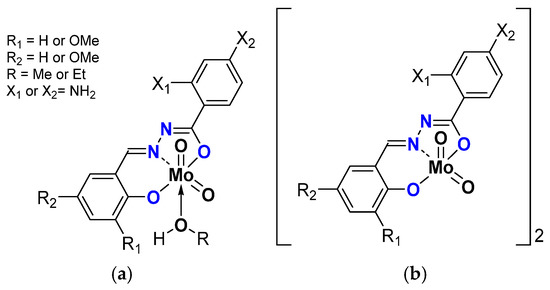

Oligomerization was emphasized with compounds having 4-aminobenzhydrazone ligands (Figure 9) [44]. Those species existed as monomer [MoO2L(ROH)] and dimer [MoO2L]2 due to the ligand bearing NH2 substituent coordinating the Mo of a neighboring molecule. The dimers reacted faster than the monomers, another proof of the postulated mechanism (Table 6). The comparison with the complexes bearing 2-aminobenzydrazones showed that the position of the NH2 is important within the stabilization of the transition state since those species were even more active. This has also been assessed through DFT calculations [45].

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of neutral monomeric (a) and polymeric (b) Mo species studied containing the salicylaldehydato fragment in the hydrazonato ligand.

Table 6.

Results of CO epoxidation under organic solvent free conditions with MoO2L complexes of Figure 9.

As expected, reactivity in TBHP in decane was faster. Different induction periods were observed between monomers and polymers and the substitution on the benzaldehydic part of the ligand seemed to have an influence.

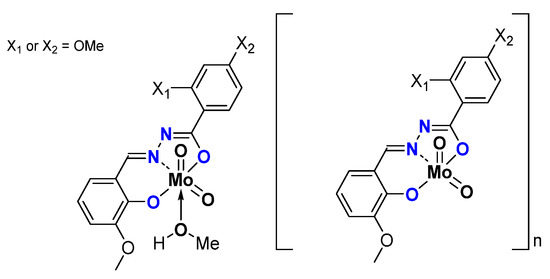

Replacing -NH2 by -OH led to a series of monomeric and oligomeric MoO2L complexes (Figure 10) tested as catalysts using TBHP as an oxidant in water (W) or in decane (D) and no other added solvent [46]. Results are compiled in Table 7. Very good results are obtained with such structures, exhibiting the role of OH on both aromatic rings.

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of neutral oligomeric and polymeric species studied containing the hydrazonato ligand.

Table 7.

Results of CO epoxidation and selectivity toward COE under organic solvent free conditions with MoO2L complexes of Figure 10.

Very recently, another variation was done, replacing the MeO on the benzaldehydic part with OH on the ortho and para position and having the 2- or 4- NH2 benzydrazide (Figure 11) [47].

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of neutral monomeric (a) and polymeric (b) Mo species studied containing the salicylaldehydato fragment in the hydrazonato ligand.

With those compounds, catalysts tests with cyclo-octene have been performed using three types of oxidants (Table 8), TBHP in water (W), TBHP in decane (D), and H2O2 in water (Table 8). As seen previously seen, TBHP in decane as oxidant gives the best results but TBHP in water gives relatively good results and is greener. With H2O2, the protocol was tested herein for the first time and the reaction was shown to be quite slow. A mechanistic study with H2O2 as oxidant showed that the less energetic mechanism is similar to the mechanism with TBHP.

Table 8.

Results of CO epoxidation under organic solvent free conditions with MoO2L complexes from Figure 11.

2.2. Extension to High-Valued Species

2.2.1. Other Olefins

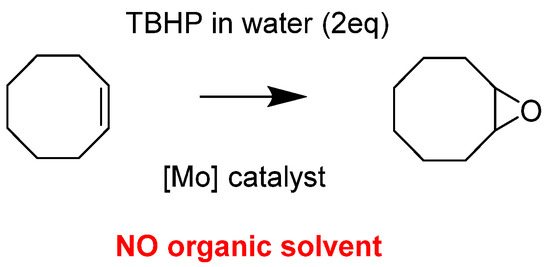

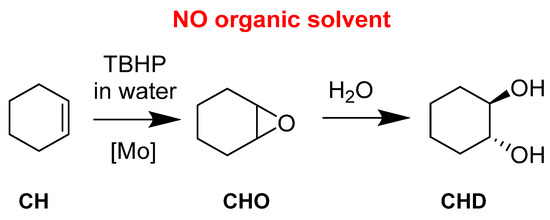

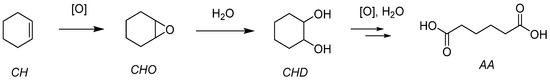

Cyclohexene (CH) has been studied because the corresponding epoxide (CHO) can be readily opened in the presence of water and leads to the trans-cyclohexanediol (CHD). (Figure 12) Further steps can lead to the complete opening of the 6-membered ring toward a very valuable species, adipic acid. The activity of the catalyst was also assessed. With a very active catalyst, the ring opening could be quickly observed. It explained why a less active catalyst did not give the diol in big quantities. This was interesting and has been used for the other presented works with applicative purposes.

Figure 12.

Organic solvent-free cyclohexene epoxidation and subsequent ring-opening with water.

2.2.2. Application to Biomass Substrates

The success of the process with simple liquid cyclic alkenes was also the basis of extra development toward the valorization of biomass with the epoxidation of a sesquiterpenes [48] and lignans [49], showing that the [MoO2(SAP)] coupled with TBHP with/without organic solvent-free conditions could replace the m-CPBA method. The species extracted from natural sources are interesting sources of chemicals [50].

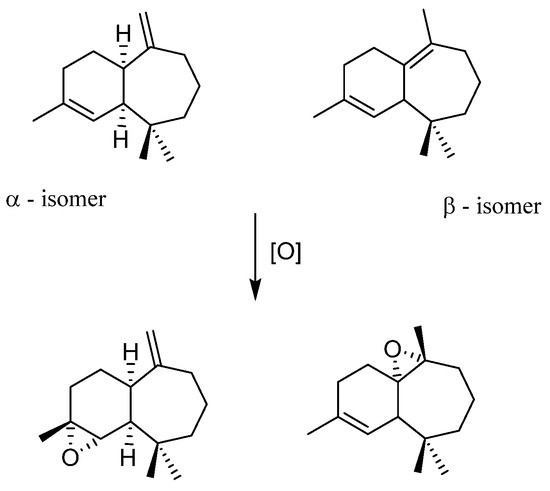

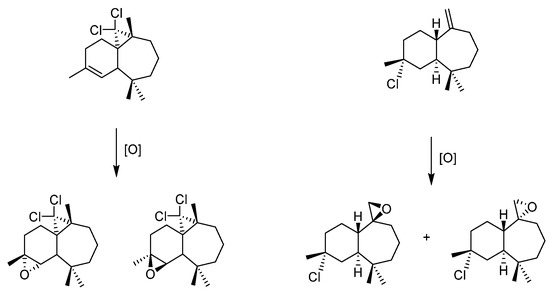

- Himachalenes

Himachalenes are sesquiterpenes obtained from the essential oil of an endemic Moroccan Tree, Cedrus atlantica [51]. Those species are relatively abundant and cheap interesting substrates. Those epoxidations exist with classical organic methods, i.e., m-CPBA oxidant in CH2Cl2, a solvent to avoid in industrial or academic processes. m-CPBA is known to be efficient but post-treatment is tedious, time-consuming, and contains one step with a basic phase that could be avoided by the use of a more atom-economic oxidant. Thus, in collaboration with a Moroccan research group expert within himachalene chemistry, the epoxidation reaction of three different substrate types was performed. [48]The starting mixture of himachalenes contains the different positions of double bonds present on the seven-membered ring, leading to a mixture of three isomers (Figure 13). It was possible to see that the regioselectivity of epoxidation with MoO2(SAP)/TBHP is identical to that using m-CPBA, privileging epoxidation on the internal bonds of the 7-member ring (β isomer) vs. α.

Figure 13.

α and β isomers of himachalenes and related epoxides.

After suppressing one internal double bond through different pathways on the α(β) isomer, only one internal (external) double bond is present to study the diastereoselectivity of the approach and it was here seen that epoxidation could be achieved with stereoselectivity slightly different than the m-CPBA method (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Epoxidation of “protected” himachalenes, leading to addition on the less reactive double bonds when himachalenes are unprotected.

- Lignans

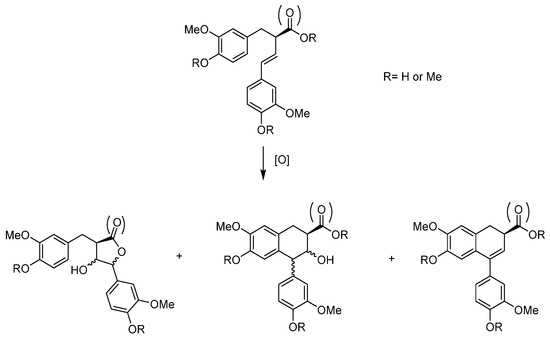

The MoO2(SAP)/TBHP catalytic system was tested on lignans [49]. The specific lignans studied-extracted from the knotwood of Norway Spruce (Picea Abies)- constitute interesting renewable biphenolic material studied in collaboration with a research group from Abo Akademi in Finland [52,53]. Those compounds, derived from imperanene and imperaneic acid, possess a very interesting double bond between two aromatics. Their oxidation products—through the formation of non-isolable epoxide followed by acid-assisted epoxide ring opening and rearrangements—can lead to different heterocyclic species, such as tetrahydrofuranes, lactones or tetralin structures (Figure 15). The [MoO2(SAP)]/TBHP method needs the use of an organic solvent since the substrate was solid. At the difference with the sesquiterpenes, the complexity of the lignans led to oligomeric side products that diminished the yields.

Figure 15.

Schematic representation of the oxidation products of 9-norlignans, tetrahydrofuronato-, aryltetralin, and butyrolactones norlignans.

- Limonene

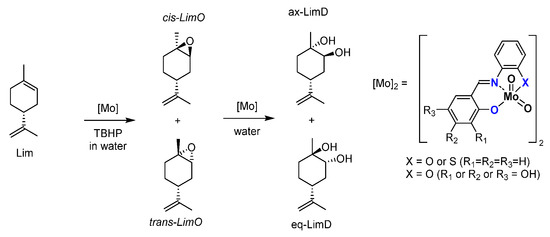

Another interesting part concerns a very simple substrate, limonene. [54] A byproduct of the orange juice industry, this terpene is cheap and relatively abundant. Used in the food and perfume industries, it can be at the base of building blocks for pharmaceutical compounds. The epoxidation of the limonene (Figure 16) is preferential on the inner double bond and can create two stereoisomers, cis- and trans- limonene epoxides (LimOs). Those epoxides are useful in different applications, from a molecular point of view, as precursors of several biobased polymers. Both LimOs are relatively stable but the presence of water can open both in two different diols, named here equatorial (eq) and axial (ax) limonene diols (LimDs). The reactivity favors the stable ax-LimD. With the use of MoO2L complexes, it has been shown that organic solvent-free conditions led to the formation of both LimOs without difference in selectivity. The interesting point lies in the ring opening of both limOs that showed in major form the ax-LimD (exclusively this species starting from cis-LimO) but also the formation of the unfavored eq-LimD without real caution within the experimental conditions, which is different from all other described protocols for this specific LimD. Indeed, to compare, the existing methods to produce the “unusual” equ-LimD requires first the isolation of the trans-LimO from a cis/trans LimO mixture and the use of mercuric reagent [55] or enzymatic protocols [56] under buffered conditions. An interesting comparison between [MoO2(SAP)] and [MoO2(SATP)] exhibited that the ONS coordination sphere around the molybdenum favored the eq-LimD generation.

Figure 16.

Schematic epoxidation of limonene (Lim) into epoxides (LimO) and water opening with water in limonene diols (LimD).

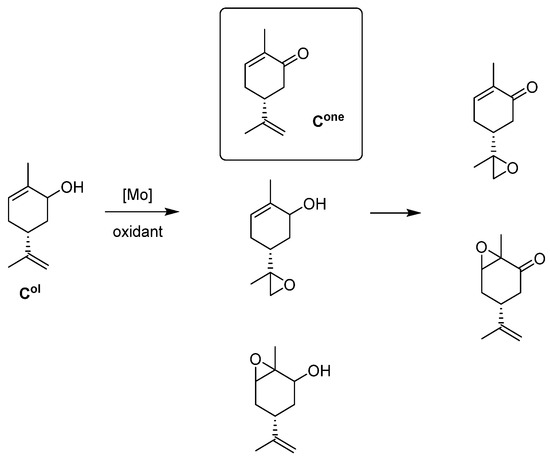

- Carveol Oxidation

With Mo complexes (Figure 17) similar to those used in Figure 8, oxidation of several alcohols was done (Figure 18). One alcohol of biomass origin, carveol, is the most interesting. The oxidants tested have been H2O2 and TBHP (water or decane) [57]. Results compiled in Table 9 showed different phenomena. H2O2 was the best oxidant to transform into carvone (40% selectivity) vs. 4–20% with TBHP. TBHP in decane reacted faster but certainly to the corresponding epoxide. With TBHP, the presence of water seems detrimental for alcohol oxidation. The main factor influencing the activity is the OH on the ligand in position R1 that seems to more quickly activate the catalyst. Some further kinetic studies showed that cis-carveol is preferentially transformed with H2O2 and trans-carveol with TBHP.

Figure 17.

Schematic representation of neutral monomeric (right) and polymeric (left) Mo species studied containing the salicylaldehydato fragment in the hydrazonato ligand.

Figure 18.

Schematic oxidation of carveol (Col) into carvone (Cone) and epoxides.

Table 9.

Results of carveol oxidation and selectivity toward carvone with MoO2L complexes from Figure 17.

3. Vanadium Species

As for molybdenum, vanadium is an element used in oxidation processes. In addition to being present in nature in some enzymatic processes, vanadium can activate smoother and cleaner oxidants, such as TBHP or H2O2 and the most convenient oxidant, O2. Several vanadium-containing compounds have been shown to be active in catalysis, for example the species used by Mimoun [58], Rehder [59], Maurya [60], or Hartung [61]. The mechanisms are numerous according to the nature of the ligands.

3.1. SAP

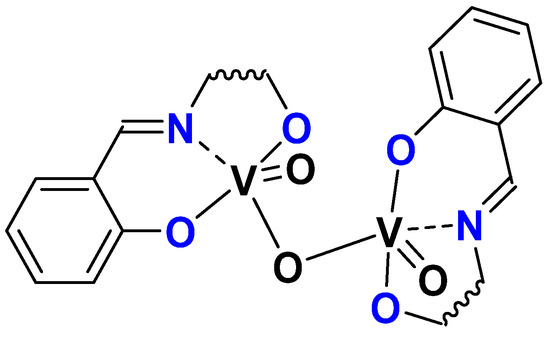

It was interesting to take advantage of the H2L ligands (H2SAE, H2SAMP, and H2SAP) presented in the molybdenum section and to study the activity of equivalent vanadium species. Through reaction with [VO(acac)2] as a vanadium precursor and subsequent oxidation, the dinuclear complexes [(L)VO]2O complexes have been isolated (Figure 19) and the structure of the compound (L = SAE, SAMP) was determined through X-ray crystallography. The catalytic activity of 1 mol% complex vs. substrate was tested with [VO(SAP)]2O as a catalyst, with both TBHP or H2O2 as oxidant, and for the first time under organic solvent-free conditions. The epoxidation of cyclo-octene gave a 94% conversion (and 83% selectivity towards the epoxide) after 5.5 h with TBHP and no reaction with H2O2 [62].

Figure 19.

Schematic representation of [VO(L)]2O complexes (L = SAP, SAE, SAMP).

3.2. ONO, ONS, and Mechanism

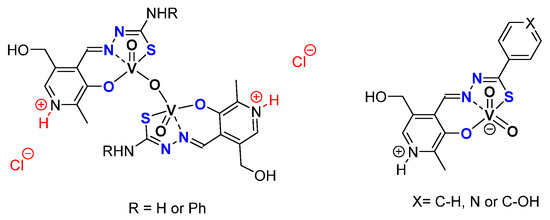

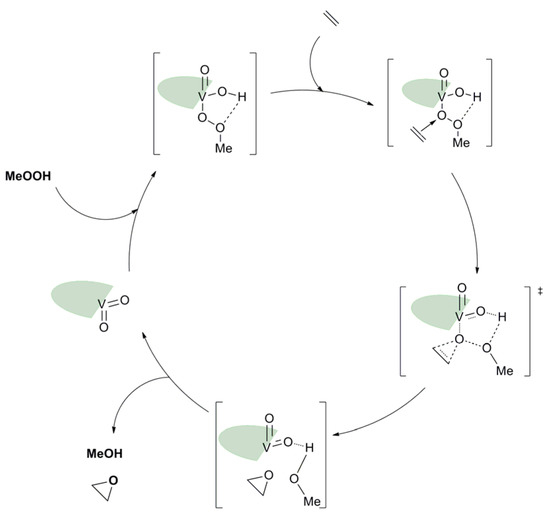

Based on the pyridoxal moiety used for the Mo complexes mentioned above, different families of vanadium complexes were synthesized with an ONS coordination sphere and containing one vanadium atom with general formulas [VO2(LH)] and an ONO coordination sphere around the vanadium creating neutral [V2O3L2] or charged [V2O3(HL)]Cl2 molecules containing two vanadium atoms (Figure 20) [63]. Those species have been tested as catalysts for the epoxidation of cyclo-octene under organic solvent-free conditions (Table 10). With TBHP in water as oxidant. Results were moderate but it was interesting to try to elucidate the mechanism through DFT. Thus, from the complexes of general formulas [VO2(LH)] (X = C-OH), calculations showed that the most energetically favorable pathway went through the formation of hydroxido-alkylperoxido [VO(OH)(OOMe)(HL)] (Figure 21) [63].

Figure 20.

Schematic representation of vanadium complexes containing pyridoxal fragments being monomeric when containing hydrazide moieties and dimeric with thiosemicarbazones.

Table 10.

Results of CO epoxidation under organic solvent-free conditions with vanadium complexes from Figure 20.

Figure 21.

Schematic catalytic cycle proposed after DFT calculations with the [VO2(LH)] (X = C-OH) complex. The ligand was schemed with the green symbol.

4. Keggin-Type Polyoxometalates as (ep)Oxidation Catalyst

Keggin Polyoxometalates (POMs) is the second class of catalysts studied using the sustainable methods presented herein. Known for a very long time for fundamental research but also for their applications in biology and in catalysis, in both homogeneous and heterogeneous conditions, POMs have the advantage of being an extremely stable species, very simple to be synthesized (mostly in solution methods but recently using solvent-free methods using mechanochemical activation). Those species can very easily activate smooth oxidants (H2O2, TBHP, O2, UHP) for several oxidation reactions. Among the active species relative to POMs; the classical Venturello–Ishii catalyst, a peroxo-oxomolybdenum complex, has been deeply studied and Keggin species were more explored for the sulfoxidation reaction.

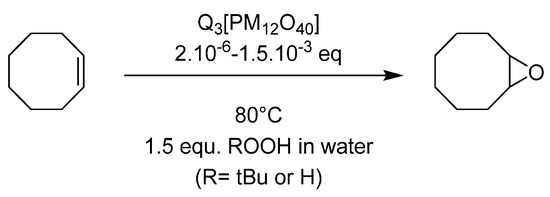

4.1. Pyridinium Salts

Very simple [PMo12O40]3− and [PW12O40]3− Keggin type heteropolyanions have been tested for catalysts as organic salts using tetrabutylammonium (TBA), butyl- (BP) or cetyl-pyridinium (CP) as cation, in order to use the catalyst in the organic medium, i.e., the substrate itself [64]. The reactions were done without organic solvent and oxidants (H2O2 or TBHP) in aqueous solution (Figure 22). The results (Table 11) exhibited activity depending on all parameters, i.e., PMo12 vs. PW12, nature of cation and nature of oxidant. With 0.1% POM vs. cyclo-octene, at 80 °C, TBHP gave a better selectivity toward epoxide without formation of the cyclo-octanediol. This latter compound was observed when H2O2 was used as oxidant, this certainly explained the low selectivity. The catalysts could be recycled and separated easily from the reaction mixture very easily at room temperature in the case of TBA and BP salts, the CP giving an emulsion that was hard to separate (although efficient). The reaction certainly takes place in the organic phase, and it was found that homogenous and heterogeneous reactions coexist (the solubility of the POMs being strongly cation dependent), explaining the difference within the selectivity. The alkyl pyridinium being the most soluble, a different test with a low catalyst charge was performed, exhibiting activity until 2 or 5 ppm POM vs. substrate ratio but a lower selectivity. Thus, it was supposed that a heterogeneous process gave better selectivity within the reaction media. In addition, it was also shown that [PMo12O40]3− species were more efficient with TBHP and [PW12O40]3− with H2O2.

Figure 22.

Epoxidation of cyclooctene catalyzed by organic salts of polyoxometalates Q3[PM12O40] (M = Mo or W, Q = Bu4N (TBA), Pyr-C4H9 (BP), Pyr-(CH2)15CH3 (CP).

Table 11.

CO epoxidation under organic solvent free conditions with organic salts of POMs from Figure 22. TBHP/cyclooctene = 1.5, 24 h, 80 °C.

4.2. Supported Catalysts

Within the aim of a sustainable and recyclable process, it was interesting to further study the catalytic activity of the simple Keggin polyanions once ionically grafted on solid support. Two types of supports have rightly been studied: functionalized organic polymer and silica nanoparticles.

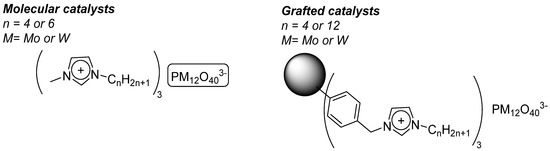

4.2.1. Grafted POMs on Merrifield Resins [65]

The protocol consisted in the functionalization of a commercial Merrifield resin by quaternization of alkyl imidazoles by the chloromethyl pending functions present on the polymer. From those functionalizations, [PM12O40]3− (M= Mo, W) were ionically grafted on those polymers. In order to compare the activity when grafted or as a free molecule, molecular analogs with same type of imidazolium countercations have been also synthesized. (Figure 23) The species were stable and could be characterized through several methods. It was possible to load more Mo Keggin than W Keggin on the Merrifield resins with a range of 55.6–66.7 μmol/g polymer for PMo12O40 and 12.2–18.9 μmol/g polymer for PW12O40.

Figure 23.

molecular and grafted catalysts on functionalized Merrifield resin.

The organic and the grafted salts of POMs have been tested for the epoxidation of cyclohexene, an interesting precursor for the synthesis of adipic acid (AA) (Figure 24). With four equivalents of oxidant starting from cyclohexene (Table 12), AA yields from 46–61% were obtained with molecular catalysts and 33–51% with grafted catalysts. The interesting fact lies in the low POM content in general (0.025% POM vs. substrate with molecular catalysts and within 0.001–0.007% range for the grafted catalysts). The study considered each step of the postulated mechanism.

Figure 24.

Epoxidation of cyclohexene leading to adipic acid.

Table 12.

Results of AA formation according to substrate using molecular of grafted POM-based catalysts from Figure 23.

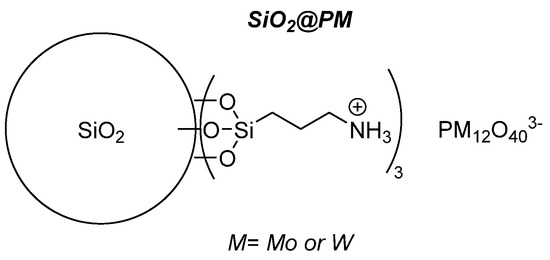

4.2.2. Grafted POMs on Functionalized Silica

The ionic grafting of POMs being a convenient recovery method, we continued in this area by using an inorganic support, i.e., ca. 76 nm diameter sized non-mesoporous silica nanoparticles functionalized at their surface by aminopropyltriethoxysilane [66]. The strategy implied a limited number of synthetic steps, ionically grafting the POM at the surface of the functionalized bead through protonation of the pending NH2 functions. (Figure 25) Using this synthetic strategy and several characterization methods, the objects contain 0.12–0.14 mmol POM/g of sample, i.e., 2–10 times more than for the Merrifield resin. Those objects were used for the epoxidation of cyclooctene (CO) (Table 13), cyclohexene (CH) (Table 14), and limonene (Lim) (Table 15) and for the oxidation of cyclohexanol (CYol) (Table 16). For CO, the conversion was a bit slower for the grafted catalysts and the selectivity was better for the H3PMo12O40 catalytic objects. The same trend between the metals was observed with CH, the grafted W-catalyst being more active than the heteropolyacids precursors and the reaction giving other products than CHD (maybe AA). With Mo, the CHD was more visible showing that the reaction was slower. With Lim, the reaction was very fast and mainly led to the formation of LimDs, as well as a few quantities of carveol (Col) and carvone (Cone).

Figure 25.

Schematic representation of POMs grafted on functionalized silica.

Table 13.

CO epoxidation into COE with heteropolyacids and corresponding anionic species from Figure 25.

CyOH gave interesting information, exhibiting better activity for the heteropolyacids, certainly due to the inner acidity (compared to the grafted ones).

Those objects were even reused and showed recyclability after the third run.

5. Conclusions

It has been shown here all the different directions taken in Castres, France toward sustainable processes. Ligand engineering (with some mechanistic DFT explanations) for the coordination complexes and catalysts grafting were the strategies employed to use a very low quantity of catalysts for different (ep)oxidation processes. All has been progressively oriented recently toward the valorization of biomass substrates, in order to situate this research in the context of circular economy. The advances in this research are still in progress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.; methodology, D.A. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.; writing—review and editing, D.A. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Clark, J.H. Green chemistry: Challenges and opportunities. Green Chem. 1999, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, U. Peak oil: The four stages of a new idea. Energy 2009, 34, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C.; Lehr, U.; Wiebe, K.S. Economic effects of peak oil. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C. Green Chemistry Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN1 0198502346. ISBN2 9780198502340. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Official Journal of the European Union 30.12.2006, L396. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/fr/legislation/directives/regulation-ec-no-1907-2006-of-the-european-parliament-and-of-the-council (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Sheldon, R.A.; Arends, I.; Hanefeld, U. Green Chemistry and Catalysis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2007; ISBN 978-3-527-30715-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, R.A. Green chemistry and resource efficiency: Towards a green economy. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3180–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, J.D.; Almeida, A.A.; Brito, M.R.; Marques, T.H.; Lima, T.C.; Sousa, D.P.; Nakano, E.; Mendonça, R.Z.; Freitas, R.M. Role of Catalase and Superoxide Dismutase Activities on Oxidative Stress in the Brain of a Phenylketonuria Animal Model and the Effect of Lipoic Acid. Planta Med. 2013, 79, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S.K.; Dhir, A. Effect of various classes of antidepressants in behavioral paradigms of despair. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 31, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezu, T. Anticonflict effects of plant-derived essential oils. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1999, 64, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A.A.C.; Pereira Costa, J.; de Carvalho, R.B.F.; Pergentino de Sousa, D.; Mendes de Freitas, R. Evaluation of acute toxicity of a natural compound (+)-limonene epoxide and its anxiolytic-like action. Brain Res. 2012, 1448, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, T.; Sudo, A. Development and application of novel ring-opening polymerizations to functional networked polymers. Polym. Sci. 2009, 47, 4847–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, Z.S. Polyurethanes from Vegetable Oils. Polym. Rev. 2008, 48, 109–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdock, G.A. Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients, 6th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.; Tuck, K.L. A new diastereoselective entry to the (1S,4R)- and (1S,4S)-isomers of 4-isopropyl-1-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-ol, aggregation pheromones of the ambrosia beetle Platypus quercivorus. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2009, 20, 2149–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.N.; Steppel, R.N.; Dorsey, J.E. m-CHLOROPERBENZOIC ACID. Org. Synth. 1970, 50, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, E.; Andrioletti, B.; Zrig, S.; Quelquejeu-Etheve, M. Enantioselective epoxidation of olefins with chiral metalloporphyrin catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, S.K.; Dinda, S.; Bhattacharyya, R. Unmatched efficiency and selectivity in the epoxidation of olefins with oxo-diperoxomolybdenum(VI) complexes as catalysts and hydrogen peroxide as terminal oxidant. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 6205–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbeleck, R.; Ambroziak, K.; Saha, B.; Sherrington, D.C. Stability and recycling of polymer-supported Mo(VI) alkene epoxidation catalysts. React. Funct. Polym. 2007, 67, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K.A. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Epoxidations. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J. European Restrictions on 1,2-Dichloroethane: C−H Activation Research and Development Should Be Liberated and not Limited. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 14286–14290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Bai, R.; Ferlin, F.; Vaccaro, L.; Li, M.; Gu, Y. Replacement strategies for non-green dipolar aprotic solvents. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 6240–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, T. Solvents and sustainable chemistry. Proc. R. Soc. A 2015, 471, 20150502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kollar, J.; Wyckoff, N.J. Process For Preparing Glycidol. U.S. Patent 3625981A, 7 December 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, M.N.; Zajaczek, G.J. Methods of Producing Epoxides. GB1.136.923, 18 December 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczak, J.M.; Glowiak, T.; Ziolkowski, J.J. The structure of binuclear molybdenum(VI) oxocomplexes with dianionic tridentate Schiff bases. Trans. Met. Chem. 1990, 15, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, J.M.; Ziółkowski, J.J. Molybdenum complex-catalysed epoxidation of unsaturated fatty acids by organic hydroperoxides. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 248, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin, D.; Bibal, C.; Neveux, B.; Daran, J.-C.; Poli, R. Structural Characterization and Theoretical Calculations of cis-Dioxo(N-salicylidene-2-aminophenolato)(ethanol)molybdenum(VI) Complexes MoO2(SAP)(EtOH) (SAP = N-salicylidene-2 aminophenolato). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2009, 635, 2120–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin, D.; Daran, J.-C.; Poli, R. Polymorph of {2-[(2-hydroxyethyl)iminiomethyl]phenolato-κO}dioxido{2-[(2-oxidoethyl) iminomethyl]phenolato-κ3O,N,O’}molybdenum(VI). Acta Cryst. 2008, 64, m101–m104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlot, J.; Uyttebroeck, N.; Agustin, D.; Poli, R. Solvent-Free Epoxidation of Olefins Catalyzed by “[MoO2(SAP)]”: A New Mode of tert-Butylhydroperoxide Activation. ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, P.D. Recent work on the mechanisms of peroxide reactions. Rec. Chem. Prog. 1950, 11, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Vanderbeeken, T.; Agustin, D.; Poli, R. Tridentate ONS vs. ONO salicylideneamino(thio)phenolato [MoO2L] complexes for catalytic solvent-free epoxidation with aqueous TBHP. Catal. Commun. 2015, 63, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guerrero, T.; Merecias, S.R.; García-Ortega, H.; Santillan, R.; Daran, J.-C.; Farfán, N.; Agustin, D.; Poli, R. Substituent effects on solvent-free epoxidation catalyzed by dioxomolybdenum(VI) complexes supported by ONO Schiff base ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2015, 431, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Daran, J.-C.; Poli, R.; Agustin, D. OH-substituted tridentate ONO Schiff base ligands and related molybdenum(VI) complexes for solvent-free (ep)oxidation catalysis with TBHP as oxidant. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2016, 416, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindric, M.; Pavlovic, G.; Katava, R.; Agustin, D. Towards a global greener process: From solventless synthesis of molybdenum(VI) ONO Schiff base complexes to catalyzed olefin epoxidation under organic-solvent-free conditions. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrdoljak, V.; Pisk, J.; Prugovecki, B.; Matkovic-Calogovic, D. Novel dioxomolybdenum(VI) and oxomolybdenum(V) complexes with pyridoxal thiosemicarbazone ligands: Synthesis and structural characterization. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2009, 362, 4059–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Agustin, D.; Vrdoljak, V.; Poli, R. Epoxidation Processes by Pyridoxal Dioxomolybdenum(VI) (Pre)Catalysts Without Organic Solvent. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2910–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Prugovecki, B.; Matkovic-Calogovic, D.; Poli, R.; Agustin, D.; Vrdoljak, V. Charged dioxomolybdenum(VI) complexes with pyridoxal thiosemicarbazone ligands as molybdenum(V) precursors in oxygen atom transfer process and epoxidation (pre)catalysts. Polyhedron 2012, 33, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Prugovečki, B.; Matković-Čalogović, D.; Jednačak, T.; Novak, P.; Agustin, D.; Vrdoljak, V. Pyridoxal hydrazonato molybdenum(VI) complexes: Assembly, structure and epoxidation (pre)catalyst testing under solvent-free conditions. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 39000–39010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrdoljak, V.; Pisk, J.; Agustin, D.; Novak, P.; Parlov Vuković, J.; Matković-Čalogovic, D. Dioxomolybdenum(VI) and dioxotungsten(VI) complexes chelated with the ONO tridentate hydrazone ligand: Synthesis, structure and catalytic epoxidation activity. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 6176–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrdoljak, V.; Pisk, J.; Prugovečki, B.; Agustin, D.; Novak, P.; Matković-Čalogović, D. Dioxotungsten(VI) complexes with isoniazid-related hydrazones as (pre)catalysts for olefin epoxidation: Solvent and ligand substituent effects. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 36384–36393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrdoljak, V.; Mandarić, M.; Hrenar, T.; Đilović, I.; Pisk, J.; Pavlović, G.; Cindrić, M.; Agustin, D. Geometrically Constrained Molybdenum(VI) Metallosupramolecular Architectures: Conventional Synthesis versus Vapor and Thermally Induced Solid-State Structural Transformations. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 3000–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Agustin, D.; Vrdoljak, V. Tetranuclear molybdenum(vi) hydrazonato epoxidation (pre)catalysts: Is water always the best choice? Catal. Commun. 2020, 142, 1060272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvijanović, D.; Pisk, J.; Pavlović, G.; Šišak-Jung, D.; Matković-Čalogović, D.; Cindrić, M.; Agustin, D.; Vrdoljak, V. Discrete mononuclear and dinuclear compounds containing a MoO22+ core and 4-aminobenzhydrazone ligands: Synthesis, structure and organic-solvent-free epoxidation activity. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Rubčić, M.; Kuzman, D.; Cindrić, M.; Agustin, D.; Vrdoljak, V. Molybdenum(VI) complexes of hemilabile aroylhydrazone ligands as efficient catalysts for greener cyclooctene epoxidation: An experimental and theoretical approach. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 5531–5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkonja, S.; Topić, E.; Mandarić, M.; Agustin, D.; Pisk, J. Efficient Molybdenum Hydrazonato Epoxidation Catalysts Operating under Green Chemistry Conditions: Water vs. Decane Competition. Catalysts 2021, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafti, A.; Razum, M.; Topić, E.; Agustin, D.; Pisk, J.; Vrdoljak, V. Implication of oxidant activation on olefin epoxidation catalysed by Molybdenum catalysts with aroylhydrazonato ligands: Experimental and theoretical studies. Mol. Catal. 2021, 512, 111764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubidi, M.; Agustin, D.; Benharref, A.; Poli, R. Solvent-free epoxidation of himachalenes and their derivatives by TBHP using [MoO2(SAP)]2 as a catalyst. C. R. Chim. 2014, 17, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrik, A.; Runeberg, P.A.; Agustin, D.C.; Eklund, P.C. Formation of Tetrahydrofurano-, Aryltetralin, and Butyrolactone Norlignans through the Epoxidation of 9-Norlignans. Molecules 2020, 25, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandrin, M.F.; Klocke, J.A.; Wurtele, E.S.; Bollinger, W.H. Natural plant chemicals: Sources of industrial and medicinal materials. Science 1985, 228, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrani, B.; Aberchane, M.; Farah, A.; Chaouch, A.; Talbi, M. Composition chimique et activité antimicrobienne des huiles essentielles extraites par hydrodistillation fractionnée du bois de Cedrus atlantica Manetti. Acta Bot. Gall. 2006, 153, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willför, S.M.; Ahotupa, M.O.; Hemming, J.E.; Reunanen, M.H.T.; Eklund, P.C.; Sjöholm, R.E.; Eckerman, C.S.E.; Suvi, P.; Pohjamo, A.; Holmbom, B.R. Antioxidant Activity of Knotwood Extractives and Phenolic Compounds of Selected Tree Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7600–7606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, P.C.; Långvik, O.K.; Wärnå, J.P.; Salmi, T.O.; Willför, S.M.; Sjöholm, R.E. Chemical studies on antioxidant mechanisms and free radical scavenging properties of lignans. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 3336–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Agustin, D.; Poli, R. Influence of ligand substitution on molybdenum catalysts with tridentate Schiff base ligands for the organic solvent-free oxidation of limonene using aqueous TBHP as oxidant. Mol. Catal. 2017, 443, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.; Andrews, P.C.; Fraser, B.H.; Forsyth, C.M.; Junk, P.C.; Massi, M.; Tuck, K.L. Facile methods for the separation of the cis- and trans-diastereomers of limonene 1,2-oxide and convenient routes to diequatorial and diaxial 1,2-diols. Synthesis 2007, 1523–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijers, C. Enantioselective hydrolysis of aryl, alicyclic and aliphatic epoxides by Rhodotorula glutinis. Tetrahedron Asym. 1997, 8, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalinec, J.; Pajski, M.; Guillo, P.; Mandarić, M.; Bebić, N.; Pisk, J.; Vrdoljak, V. Alcohol Oxidation Assisted by Molybdenum Hydrazonato Catalysts Employing Hydroperoxide Oxidants. Catalysts 2021, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimoun, H.; Mignard, M.; Brechot, P.; Saussine, L. Selective epoxidation of olefins by oxo[N-(2-oxidophenyl)salicylidenaminato]-vanadium(V) alkylperoxides. On the mechanism of the Halcon epoxidation process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, D. The coordination chemistry of vanadium as related to its biological functions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 182, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, M.R. Development of the coordination chemistry of vanadium through bis(acetylacetonato) oxovanadium(IV): Synthesis, reactivity and structural aspects. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 237, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, J. Stereoselective syntheses of functionalized cyclic ethers via (Schiff-base)vanadium(V)-catalyzed oxidations. Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 77, 1559–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordelle, C.; Agustin, D.; Daran, J.-C.; Poli, R. Oxo-bridged bis oxo-vanadium(V) complexes with tridentate Schiff base ligands (VOL)2O (L = SAE, SAMP, SAP): Synthesis, structure and epoxidation catalysis under solvent-free conditions. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 364, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Daran, J.-C.; Poli, R.; Agustin, D. Pyridoxal based ONS and ONO Vanadium(V) complexes: Structural analysis and catalytic application in organic solvent free epoxidation. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 403, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, B.; Mesquita Fernandes, D.; Daran, J.-C.; Agustin, D.; Poli, R. Investigation of induction times, activity, selectivity, interface and mass transport in solvent-free epoxidation by H2O2 and TBHP: A study with organic salts of the [PMo12O40]3− anion. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 3466–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Agustin, D.; Poli, R. Organic Salts and Merrifield Resin Supported [PM12O40]3− (M = Mo or W) as Catalysts for Adipic Acid Synthesis. Molecules 2019, 24, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gayet, F.; Guillo, P.; Agustin, D. Organic Solvent-Free Olefins and Alcohols (ep)oxidation Using Recoverable Catalysts Based on [PM12O40]3− (M = Mo or W) Ionically Grafted on Amino Functionalized Silica Nanobeads. Materials 2019, 12, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).